Summary

Member states across the Eastern Mediterranean region face unprecedented health challenges, buffeted by demographic change, a dual disease burden, rising health costs, and the effects of ongoing conflict and population movements – exacerbated in the near-term by instability arising from recent political upheaval in the Middle East. However, health actors in the region are not well positioned to respond to these challenges because of a dearth of good quality health research. This review presents an assessment of the current state of health research systems across the Eastern Mediterranean based on publicly available literature and data sources. The review finds that – while there have been important improvements in productivity in the Region since the early 1990s – overall research performance is poor with critical deficits in system stewardship, research training and human resource development, and basic data surveillance. Translation of research into policy and practice is hampered by weak institutional and financial incentives, and concerns over the political sensitivity of findings. These problems are attributable primarily to chronic under-investment – both financial and political – in Research and Development systems. This review identifies key areas for a regional strategy and how to address challenges, including increased funding, research capacity-building, reform of governance arrangements and sustained political investment in research support. A central finding is that the poverty of publicly available data on research systems makes meaningful cross-comparisons of performance within the EMR difficult. We therefore conclude by calling for work to improve understanding of health research systems across the region as a matter of urgency.

Introduction

Health systems across the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) stand at cross-roads. In this strategically significant, natural-resource abundant region, demographic change, a dual disease burden and political and social upheaval all pose unprecedented challenges to health and healthcare delivery.1 Our understanding of the nature, extent and determinants of these challenges – as well as the most appropriate interventions to tackle them – is poor, largely due to longstanding under-investment in health research.2–5

The aims of this paper are two-fold. Firstly, we provide an overview of the current state of health research across the Eastern Mediterranean in a climate of renewed interest on an international level in links between research and health improvement.6 Secondly, we outline a health research strategy for the EMR that will direct investment – financial, institutional and political – into this neglected area of health system development, building on recent theoretical work on health system governance. For the purposes of this paper, the ‘Eastern Mediterranean Region’ is taken to include all countries established within the WHO's Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, namely: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

Conceptual framework

Recent theoretical work on health research emphasizes a systems approach, beginning with the publication of the Commission on Health Research for Development's first report in 1990,7 and latterly in the 2004 WHO World Report on Knowledge for Better Health.8 In this view, a health research ‘system’ is understood to incorporate people, institutions and processes that underpin a range of health research activities; the relationship between health research systems and health systems should, ideally, be one of mutual interdependence. This approach has been advocated as a means of explicitly linking health research activity on a national level to health system objectives, with the aim of improving population health.

From an evaluation perspective, the systems approach responds to recognized limitations of methods that have historically been used for monitoring and evaluating health research activities. These have often modelled the research process as linear, focusing on input (e.g. financial and human resources) and output measures (e.g. publications), at the expense of outcomes such as improved health and more effective health system activity.9,10 Efforts to operationalize assessments of health research activity from a systems perspective can be divided into three categories:

Functional: a focus on core activities that a health research system should perform

Process: examines aspects of the research cycle from needs assessment to downstream impact and

Institutional: which focuses on institutions within the system that commission, carry out and utilize research.11

Research system mapping and evaluation efforts have, to date, focused on activity at the national or sub-national level – there is, to the best of our knowledge, no precedent for assessments of health research activity at regional or international levels. This paper provides an overview of the current state of health research across the EMR. Since a detailed, country-by-country analysis is beyond the scope of this review, we have adapted the functional approach used elsewhere for national health research systems to incorporate regional initiatives as part of a broader system for supporting research. We believe that this provides the fullest overview of all the actors, resources and processes involved in health research at national level, while describing a model that is capable of accommodating activity and initiatives at the regional level and possibly more broadly, internationally.

In doing so, we draw on the clearest articulation of the functional perspective on health research assessment currently available, after Pang and Terry,6 who outline four cardinal features of effective health research systems:

Financing – through sustainable and transparent processes for mobilizing and allocating funds for research

Production and utilization of research – generation of scientifically valid research findings that respond to local health challenges, and allow for translation into new tools (e.g. drugs, vaccines) and policies

Resources – in particular, human and institutional capacity to support research work

Stewardship – provision of strong leadership to direct, coordinate, manage and review research.

In the discussion that follows, we map the current state of health research across the region using these criteria, highlighting areas of strength and deficiency.

Methods

This review article is based on findings from a rapid assessment of peer-reviewed literature in PubMed, and searches of grey literature sources held online by the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office's (EMRO) Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR) Database and Google Scholar. We also conducted specific searches (using the same keywords – available on request from the authors) for reports and other literature sources produced by the WHO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and World Bank, as well as Thomson Reuters for data on research productivity from the EMR, before conducting snowball searches for relevant material drawing on citations from sources identified in the first round of results. Due to a dearth of published material on this subject matter, we included a full spectrum of peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed documents, ranging from empirical research studies to editorials, dissertations and meeting reports. Global sources were consulted for research performance data because of issues of cross-comparability when drawing information from, for example, Health Ministry websites in EMR member states. Studies included were required to have been published after 1995, and to address research activity and performance at either the national or regional level.

Results

Financing

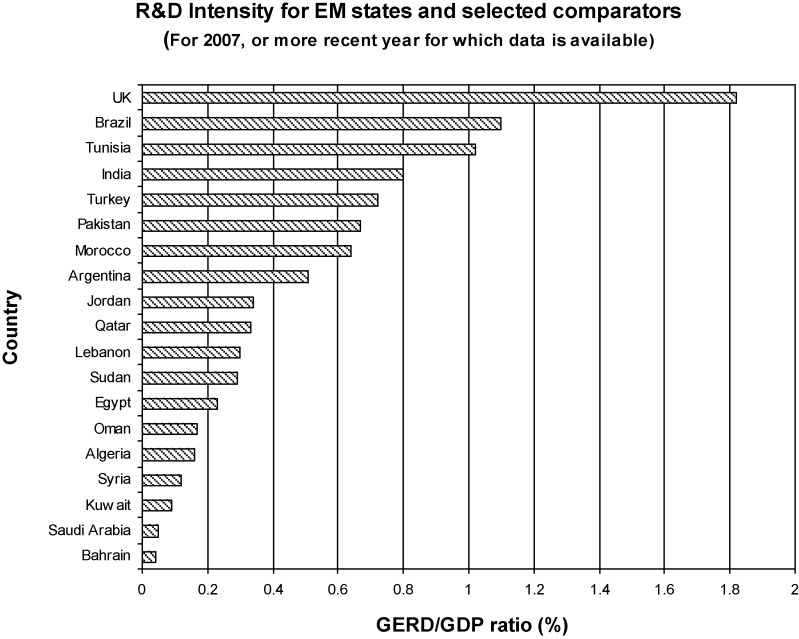

In the Eastern Mediterranean region health and healthcare research is not seen as a priority in funding terms by governments, the private or third sectors. Investment in research systems is low in comparative terms, as it is for health in general. In fact, available evidence indicates that Research & Development (R&D) funding in the region is among the lowest in the world, notwithstanding considerable gross domestic product (GDP) differences between member states. R&D expenditures average around 0.3% of GDP, 97% of which is publicly provided. This is well below world leaders such as the UK (1.8%) and Japan (2.8%).3,4 Notably, R&D intensity (expressed as the ratio of gross domestic expenditure on R&D [GERD] to GDP) is – with the exception of Qatar – lowest among the Gulf States, where much of the regional wealth is concentrated, although raw levels of investment are higher than in their regional neighbours. R&D intensity comparisons between Eastern Mediterranean states as a whole and comparators such as Brazil and India are generally unfavourable (see Figure 1). There is evidence of a change of approach in some EMR member states recently, however: public investment in R&D has been increased significantly in Iran (4%, compared with 0.59% of GDP in 2006), Qatar (projected 2.8% by 2012) and Tunisia (1.25%, compared with 0.03% in 1996).12,13 The absence of recently gathered data on health-specific research expenditure across EMR member states poses problems in terms of meaningful cross-comparison, however.

Figure 1.

R&D intensity in 2007 (or more recent year for which data were available) for Eastern Mediterranean states and selected comparators (GERD, gross domestic expenditure on R&D). Source: UNESCO Science Report, 2010

Importantly, the review found no reliable data on total funding for health research projects at a regional level, but it is apparent that the WHO Regional Office is the only body offering financial support for funding on a regional level. It does so through three funds offering small grants of up to $20,000 for health research projects of different types, the majority of beneficiaries thus far coming from Iran, Pakistan, Egypt and Lebanon.14

Producing and using health research

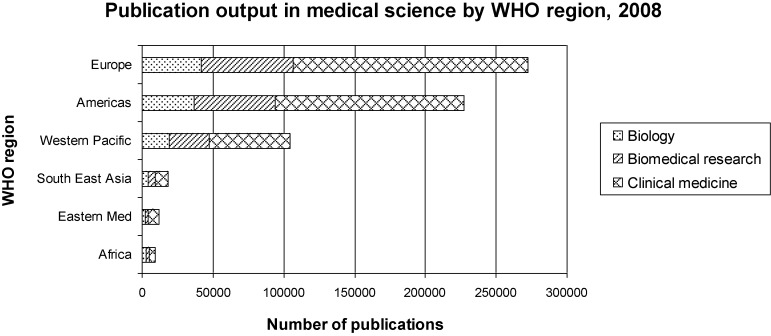

The effects of systemic underinvestment on research productivity are becoming increasingly apparent. Although volume of published journal papers has well recognized limitations as a proxy indicator for research productivity, raw output from the Eastern Mediterranean is strikingly low when set against international comparators, notwithstanding improvements across the region over the past 10 years.15,16 This picture is just as true for the health and biomedical sciences as for scientific research output overall. As Figure 2 indicates, research output in health and allied fields across the region is comparable only with sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia – but is still some way behind the latter. There are also considerable variations in productivity within the Eastern Mediterranean. While Egypt and Pakistan contribute around 60% of all articles logged in Index Medicus for the EMR, Iraq and Tunisia produce just 2.5% and 5.1%, respectively, despite high levels of adult literacy and comparatively strong education systems.17

Figure 2.

Research output in raw publication terms for medical and allied research by WHO region, 2008. Source: UNESCO Science Report, 2010

Assessments of research impact are more encouraging – where data are available. Since 1990, the citation impact of papers published in Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Jordan relative to the world average has increased by around 25%. Jordan and Egypt have been particularly strong performers since 2000. But overall citation impact for these countries still hovers at around 50% of the world average.15 And in a ground-breaking international assessment of return on research investment published in 2004, Iran was the only country from the EMR to feature in a study covering the countries of origin for 98% of the world's most highly cited publications.18

Effective knowledge transfer (KT) of research into policy is, however, a major challenge across the region. Recent findings from the EMR suggest there are problems of both demand for, and supply of, relevant research.19,20 While researchers and policy-makers recognize the importance of using evidence in policy, translation is hampered by limited opportunities for interaction during the policy-making process, the absence of institutional and financial incentives to support translation, and concerns over the political sensitivity of research findings. The Iranian model of university-health service integration seems to have brought some dividends in this respect, but evidence suggests that the model needs further refining to help break down enduring barriers to research translation.21 In recognition of the deficit in KT, the WHO EMRO established a regional Evidence Informed Policy Network (EVIPNet) in January 2009 to host workshops bringing researchers and policy-makers together (see http://goo.gl/jNnIX, accessed on 16 August 2012). Further work is however required, especially on policy-readiness of health research – as exemplified by systematic review output and clinical trial registration. Systematic review output by EMR member state researchers has improved since the mid-1990s, but it continues to lag behind middle- and low-income country comparators.22 Clinical trial registration by member states, meanwhile, has increased strikingly from a very low base in 2004, but this is overwhelmingly due to research activity in one country – Iran.23

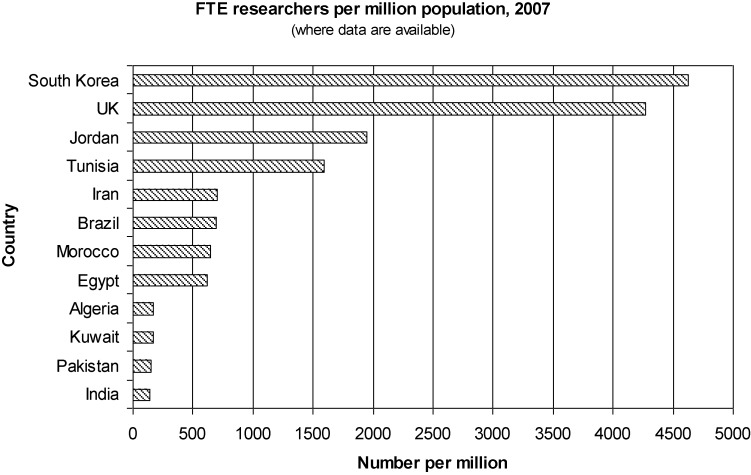

Creating and sustaining resources for health research

The limitations of KT systems in the EMR are a product of low levels of financial investment and a predominantly national focus for funding but also of reduced research capacity in four key areas. Firstly, human capacity to support good quality health research work in the EMR is underdeveloped. Although the region performs well against selected international comparators in terms of the number of R&D personnel trained (see Figure 3), poor remuneration and a shortage of appropriate training opportunities to develop research-relevant skills across the EMR have long been recognized. Assessments of skills for health research in the region have consistently identified weaknesses around knowledge of research methods, poor understanding of data analysis techniques, communication skills and computer literacy.24 Perhaps as a consequence of these factors, brain-drain has long been a feature of the R&D landscape in the Eastern Mediterranean, especially among Arab member states. Again, data specific to the health research sector are in short supply, but indicative figures are available: Egypt, Iran, Lebanon and Algeria fall within the bottom 40 countries worldwide in a World Economic Forum ranking of vulnerability to ‘brain drain’, although the Gulf States (especially Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Oman) score well for work-force retention.25 Arab member states are thought to lose 50% of their newly qualified physicians and 15% of their scientists annually.1

Figure 3.

Number of full-time equivalent (FTE) researchers per million of population in selected EMR member states (where data were available) in 2007. Source: UNESCO Science Report, 2010

Secondly, although the region is home to some innovative institutional models for supporting health research, organizational support is generally weak. Low levels of investment are reflected in chronically overburdened higher education systems which are unable to compete internationally. One – albeit controversial – indication comes from the Times Higher Education World Ranking of universities, 2011–2012, in which only two universities from EMR member states features in the top 400 worldwide (http://goo.gl/bbBH, accessed on 16 August 2012). Exceptions to this pattern include Iran's integration of university research with health service delivery (instituted in 1984), but recent evidence suggests that this model may have been vulnerable to channeling of funding away from research and into core health service delivery.21,26 Some initiatives are now attempting to draw researchers back to the region with offers of generous funding and support on a par with major international research establishments (for example, the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, and Qatar Foundation's Education City). However, these are concentrated in the Gulf States where the existing research base is weaker, and in any case health projects form only a fraction of the wider remit of these initiatives.

Thirdly, mechanisms for fostering collaborative research that might address some of the health challenges common to most EMR member states have been slow to develop. The review found little evidence of specific policies intended to foster collaboration on an intra-regional or international level beyond one or two regional networks (in reproductive health, for example: http://goo.gl/PlHKD, accessed on 16 August 2012), despite the importance attached to this for research capacity-building in low- and middle-income countries by the 2004 World Report.8 As a result, intra-regional cooperation on health research appears very limited indeed: taking journal paper co-authorship as a proxy, the review found that, where international collaborators for research are sought, they are overwhelmingly concentrated in Europe and North America (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sources of international collaboration for papers published in Egypt, Iran, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Source: Adams et al. (2011)

Finally, effective, public health-oriented research to tackle key challenges facing the region is undermined by the enduring absence of basic population-based surveillance of key health risks (including cardiovascular disease, cancer, mental health and health inequalities), and health system performance data collection. Reliable and above all transparent data collection remains limited or non-existent, even in the wealthier Eastern Mediterranean countries.27 A report published by the WHO EMRO concluded that this was due to ‘insufficient commitment to the systems, lack of practical guidelines, overwhelming reporting requirements, weak involvement of the private sector, lack of transparency, shortage of human resources and poor analysis of data’.24 The effects of this are often directly observable in scientific output; recent systematic reviews of epidemiological work on chronic disease prevalence in the Gulf region, for instance, have noted considerable variations in the quality of available observational studies, including inadequately describe population characteristics, variable risk factor definitions and failure to report confidence intervals for prevalence estimates.28

Stewardship

Evidence examined for this review demonstrates clearly that research governance is a key area for development. A 2008 WHO EMRO study revealed that, of 10 countries examined only four had national governance structures for health research systems, two had dedicated national health research policies and three had identified national research priorities.3 National-level ethical oversight committees are present in a majority of EMR countries, but administrative and financial support for their work is often lacking. A recent survey found that only 21% of respondents from national ethical committees across the region had received any formal ethics training,29 reflecting broader limitations in ethical training and understanding among the EMR health research community at large.30 National academies of science which – as advocates for science and impartial advisory bodies – have played a leading role in the development of scientific research establishments in the USA, UK and France for many years, are striking by their absence.13

In the absence of strategic capacity, prioritization and coordination of health research initiatives is difficult and responsiveness to local population health needs is reduced. It also makes effective oversight and performance management of health research systems impossible because key benchmarks of performance are not available on a system-wide scale; of the 10 countries examined in the above study,3 just one had an established monitoring and evaluation processes in support of its national health research system.

Discussion

The review findings show that sustained under-investment in health research on a national level across the EMR has given rise to critical skills shortages, weak capacity and comparatively low research productivity. Viewed alongside the limitations of basic public health surveillance systems, these problems impose major constraints on the capacity of governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to address unprecedented health challenges that member states face. Building sustainable, national research systems to support KT for improved health is one of the defining challenges facing governments across the region. The imperative for an effective regional strategy for health research to help support national health research system development is stronger than ever – a problem to which we turn below.

Limitations and caveats to the study

Some important limitations to the current study should be emphasized, however. First, data collection was based exclusively on a review of literature and publicly available data sources and may not have captured the full range of local activities underway across the region. Our sense from the material reviewed was that many ad hoc arrangements exist, and further work is needed to capture lessons learned from them. Secondly, often only aggregate data on research system performance across all scientific disciplines was available. Caution is inevitably required in drawing lessons from this that may be applied to health research specifically. Third, in the absence of better data on health research in the EMR, we have included some indicators that can be regarded as crude proxies for research performance (e.g. raw journal paper output). Implicit in this review, therefore, is an urgent call for improved data collection on health research performance in the round.

Towards a comprehensive strategy for health research in the EMR

Although each member state will wish primarily to pursue national policies to support health research (as, indeed, some already are) there exists an important opportunity for supranational organizations and groupings to steer improvements in health research in the Eastern Mediterranean, through a regional strategy.

A central goal of the strategy should be to encourage more effective research stewardship in the EMR. The review found evidence that few member states had adopted national plans or strategies for health research and ethical oversight – while present – was often rudimentary. We also found some important examples of innovative approaches to health research governance – notably Iran's integration of university research with health service delivery – that merit closer evaluation as possible models for replication elsewhere. Regional organizations like WHO EMRO can play an active role in improving stewardship through education, training in research management and monitoring.

Second, there must be greatly improved mobilization of funding for health research across the EMR. The review found that Iran, Qatar and Tunisia are leading the way in boosting public funding for research. However, overall investment remains low and the absence of effective regional mobilization on common health problems is a concern given that financial resources in many member states are limited. The strategy should outline the case for pooled funding on a regional level to support research in key areas of need – drawing on contributions from international donors, governments, the private and third sectors. In the case of state funding for research, the strategy should highlight the need for re-balancing domestic political priorities to permit increased spending on research systems, given strong evidence linking R&D to increased economic productivity.8

Third, the strategy should emphasize the critical importance of creating and sustaining resources for research. In the near term, this will depend on increased investment in the chronically under-funded higher education sector. Collaborative work has a key role to play in boosting return on investment and more needs to be done to incentivize this both through existing regional funding schemes (e.g. via WHO EMRO) and new ones supported by international donors that emphasize South–South, rather than exclusively North–South, collaboration. The Reproductive Health Network already in place may provide a useful model for further cross-country networking by health researchers, but networks are difficult to operationalize without financial and administrative support.

Effective production and utilization of health research represents perhaps the most difficult challenge over the long term, since it is fundamentally dependent on improvements in the other three areas, and will likely require greater transparency in the policy-making process than has hitherto been the case in many member states. The EVIPNet initiative is a significant development, and we encourage sustained support for it as platform for exchange and identification of good practice.

Finally, the strategy should foster cross-regional data collection as a matter of urgency. Two key findings from our assessment of health research in the region conclude that: (1) there are many areas in which we simply do not know how research systems are performing, and (2) there is a particular difficulty in teasing out data on health research from aggregate information on R&D across all disciplines. If health research performance is to better meet the needs of populations in the EMR, improved tracking and analysis of research systems and productivity must be prioritized, starting with a full, cross-regional mapping exercise along the lines of the Health System Observatory (http://goo.gl/GGTJ9, accessed on 16 August 2012)) launched by WHO EMRO some years ago.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

SR was a member of the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Advisory Committee on Health research until 2011

Funding

This is an independent paper, produced without specific funding support

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

SR

Contributorship

SAI, AMcD, FGA and SR initiated the project and designed the study. SAI and AMcD conducted the original research, drafted and revised the paper. ED, FGA, AM, APC and SR all revised the paper

Acknowledgements

The Department of Primary Care and Public Health at Imperial College London is grateful for support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care (CLAHRC) Scheme, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre scheme, and the Imperial Centre for Patient Safety and Service Quality

References

- 1.Maziak W. The crisis of health in a crisis ridden region. Int J Public Health 2009;54:349–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akala FA, El-Saharty S. Public health challenges in the Middle East and North Africa. Lancet 2006;367:961–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy A, Khoja TA, Abou-Zeid AH, Ghannem H, IJsselmuiden C. National health research system mapping in 10 Eastern Mediterranean countries. East Mediterr Health J 2008;14:502–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nour S. Science and Technology (S&T) Development Indicators in the Arab Region: A Comparative Study of Arab Gulf and Mediterranean Countries. Paper submitted for the ERF 10th Annual Conference, 16–18 December 2003, Morocco See http://www.erf.org.eg/CMS/uploads/pdf/1184757383_Satti.pdf (last checked 1 February 2012)

- 5.Rashad H, Khadr Z, Giacama R, Khawaja M. Knowledge gaps: the agenda for research and action, Chapter 8. In: Jabbour S, et al., eds. Public Health in the Arab World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang T, Terry RF. WHO/PLoS collection ‘no health without research’: a call for papers. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001008 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001008 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Commission on Health Research for Development Health Research: Essential Link to Equity in Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO World Report on Knowledge for Better Health. Geneva: WHO, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pang T, Sadana R, Hanney S, Bhutta ZA, Hyder AA, Simon J. Knowledge for better health – a conceptual framework and foundation for health research systems. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:815–20 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanney SR, Gonzalez-Block MA, Buxton MJ, Kogan M. The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Res Policy Systems 2003;1:2 doi:10.1186/1478-4505-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy A, Ijsselmuiden C. Building and strengthening national health research systems: a manager's guide to developing and managing effective health research systems. Council Health Res Dev . Geneva: Council for Health Research Development, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations Development Program The Arab Knowledge Report 2009: Towards Productive Intercommunication for Knowledge. New York: United Nations Development Program, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNESCO UNESCO Science Report 2010. Paris: UNESCO, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shideed O, Al-Gasseer N. Appraisal of the research grant schemes of the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean: the way forward. East Mediterr Health J 2012;18:515–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adams J, King C, Pendlebury D, Hook D, Wilsdon J. Global Research Report Middle East: Exploring the Changing Landscape of Arabian, Persian and Turkish Research. Leeds: Evidence/Thomson Reuters, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams J, King C, Hook D. Global Research Report Africa Leeds: Evidence/Thomson Reuters, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Shorbaji N. Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean region. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2008:5–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King D. The scientific impact of nations. Nature 2004;430:311–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Jardali F, Lavis JN, Ataya N, Jamal D. Use of health systems and policy research evidence in the health policymaking in eastern Mediterranean countries: views and practices of researchers. Implementation Sci 2012;7:2.10.1186/1748-5908-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Jardali F, Lavis JN, Ataya N, Jamal D, Ammar W, Raouf S. Use of health systems evidence by policymakers in eastern Mediterranean countries: views, practices, and contextual influences. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:200.10.1186/1472-6963-12-200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majdzadeh R, Nedjat S, Denis JL, Yazdizadeh B, Gholami J. ‘Linking research to action’ in Iran: two decades after integration of the Health Ministry and the medical universities. Public Health 124:404–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law T, Lavis J, Hamandi A, Cheung A, El-Jardali F. Climate for evidence-informed health systems: a profile of systematic review production in 41 low- and middle-income countries, 1996–2008. J Health Serv Res Policy 2012;17:4–10,10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Gasseer N, Shideed O. Clinical trial registration in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: a luxury or a necessity? East Mediterr Health J 2012;18:108–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO EMRO Report on the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Consultation in Preparation for the Ministerial Summit on Health Research. Cairo: WHO EMRO, 2004. (WHO-EM/RPC/015/E) [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Economic Forum The Global Competitiveness Report, 2011–12. Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majdzadeh R, Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Gholami J, Ahghari S. Strengthening evidence-based decision-making: is it possible without improving health system stewardship? Health Policy Planning 2011;27:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saleh SS, Alameddine MS, El-Jardali F. The case for developing publicly-accessible datasets for health services research in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:197.10.1186/1472-6963-9-197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alhyas L, McKay A, Balasanthiran A, Majeed A. Prevalences of overweight, obesity, hyperglycaemia, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in the Gulf: systematic review. J R Soc Med Short Rep 2011;2:7.10.1258/shorts.2011.011019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abou-Zeid A, Afzal M, Silverman HJ. Capacity mapping of national ethics committees in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. BMC Med Ethics 2009;10:8.10.1186/1472-6939-10-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdur Rab M, Afzal M, Abou-Zeid A, Silverman H. Ethical practices for health research in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization: a retrospective data analysis. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e2094.10.1371/journal.pone.0002094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]