Abstract

ZNF313 encoding a zinc-binding protein is located at chromosome 20q13.13, which exhibits a frequent genomic amplification in multiple human cancers. However, the biological function of ZNF313 remains largely undefined. Here we report that ZNF313 is an ubiquitin E3 ligase that has a critical role in the regulation of cell cycle progression, differentiation and senescence. In this study, ZNF313 is initially identified as a XIAP-associated factor 1 (XAF1)-interacting protein, which upregulates the stability and proapoptotic effect of XAF1. Intriguingly, we found that ZNF313 activates cell cycle progression and suppresses cellular senescence through the RING domain-mediated degradation of p21WAF1. ZNF313 ubiquitinates p21WAF1 and also destabilizes p27KIP1 and p57KIP2, three members of the CDK-interacting protein (CIP)/kinase inhibitor protein (KIP) family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, whereas it does not affect the stability of the inhibitor of CDK (INK4) family members, such as p16INK4A and p15INK4B. ZNF313 expression is tightly controlled during the cell cycle and its elevation at the late G1 phase is crucial for the G1-to-S phase transition. ZNF313 is induced by mitogenic growth factors and its blockade profoundly delays cell cycle progression and accelerates p21WAF1-mediated senescence. Both replicative and stress-induced senescence are accompanied with ZNF313 reduction. ZNF313 is downregulated during cellular differentiation process in vitro and in vivo, while it is commonly upregulated in many types of cancer cells. ZNF313 shows both the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization in epithelial cells of normal tissues, but exhibits an intense cytoplasmic distribution in carcinoma cells of tumor tissues. Collectively, ZNF313 is a novel E3 ligase for p21WAF1, whose alteration might be implicated in the pathogenesis of several human diseases, including cancers.

Keywords: XAF1, CDK inhibitor, ubiquitin ligase, apoptosis, differentiation

Zinc-finger gene family is one of the largest gene families, which has a crucial role in the regulation of gene transcription. ZNF313, also known as RNF114 or ZNF228, is a recently identified zinc-binding protein that contains both C2H2 and RING-finger structure, the most common types of the zinc-binding motif.1, 2 ZNF313 is widely expressed in tissues, most abundantly in testis, heart, liver and kidney, and at reduced levels in skeletal muscle, lung, colon, brain and placenta.1, 3 Recent studies showed that ZNF313 is an ubiquitin ligase, which binds polyubiquitin through the C-terminal ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) and exerts E3 ligase activity via the N-terminal RING domain.4, 5

The ZNF313 gene is located at human chromosome 20q13.13, which displays a frequent genomic amplification in many types of malignancies, including cervical, gastric and colon cancer.3, 6, 7 Moreover, the ZNF313 gene was identified to be amplified and its expression level is elevated in patients with psoriasis, an immune-mediated skin disease.4, 6, 7, 8 In addition, ZNF313 expression is reduced in testes of azoospermic patients compared with fertile adult testes, suggesting that it may have a role in normal spermatogenesis and male fertility.3 These findings thus suggest that ZNF313 is involved in many aspects of cellular processes and its alteration is implicated in the pathogenesis of various human diseases, including chronic inflammation, infertility and tumorigenesis. Nevertheless, the biological function of ZNF313 and the molecular mechanism underlying its action remained largely undefined.

The transition between cell cycle phases of eukaryotic cells is an ordered set of events that was governed by cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which are activated by cyclin binding and inhibited by CDK inhibitors. CDK protein levels show no significant change during the cell cycle and their activities are regulated mainly through expression and degradation of cyclins and CKIs.9 The CDK inhibitor can be divided into two families. The four members of the inhibitor of CDKs (INK4) family – p16INK4A, p15INK4B, p18INK4C and p19INK4D – specifically bind CDK4 and CDK6 and prevent their association with D-type cyclins. The three members of the CDK-interacting protein (CIP) or kinase inhibitor protein (KIP) family – p21CIP1/WAF1, p27KIP1 and p57KIP2 – form heterotrimeric complexes with the G1/S CDKs and control a broader spectrum of cyclin–CDK complexes.10, 11 The release of cells from a quiescent state (G0) leads to entry into the first gap phase (G1), followed by DNA replication in the synthetic phase (S), the second gap phase (G2) and mitosis phase (M). When G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle is disturbed, cells can be arrested temporarily (quiescence) or permanently (senescence).12

XIAP-associated factor 1 (XAF1) is a tumor suppressor gene, which is ubiquitously expressed in all normal tissues, but absent or present at very low levels in many human cancers because of aberrant promoter hypermethylation.13, 14, 15, 16 XAF1 was originally identified as a nuclear protein that could bind and interfere with anticaspase function of XIAP by sequestering XIAP protein to the nucleus.13 XAF1 was also identified as an interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene that contributes to sensitization of cells to TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis.17, 18, 19 We previously reported that XAF1 enhances p53 protein stability and its proapoptotic activity is attenuated in p53-deficient cells, suggesting its involvement in apoptotic signaling of p53.16 Despite accumulating evidence supporting tumor suppressive role of XAF1, the molecular basis for its function has been poorly understood.

Results

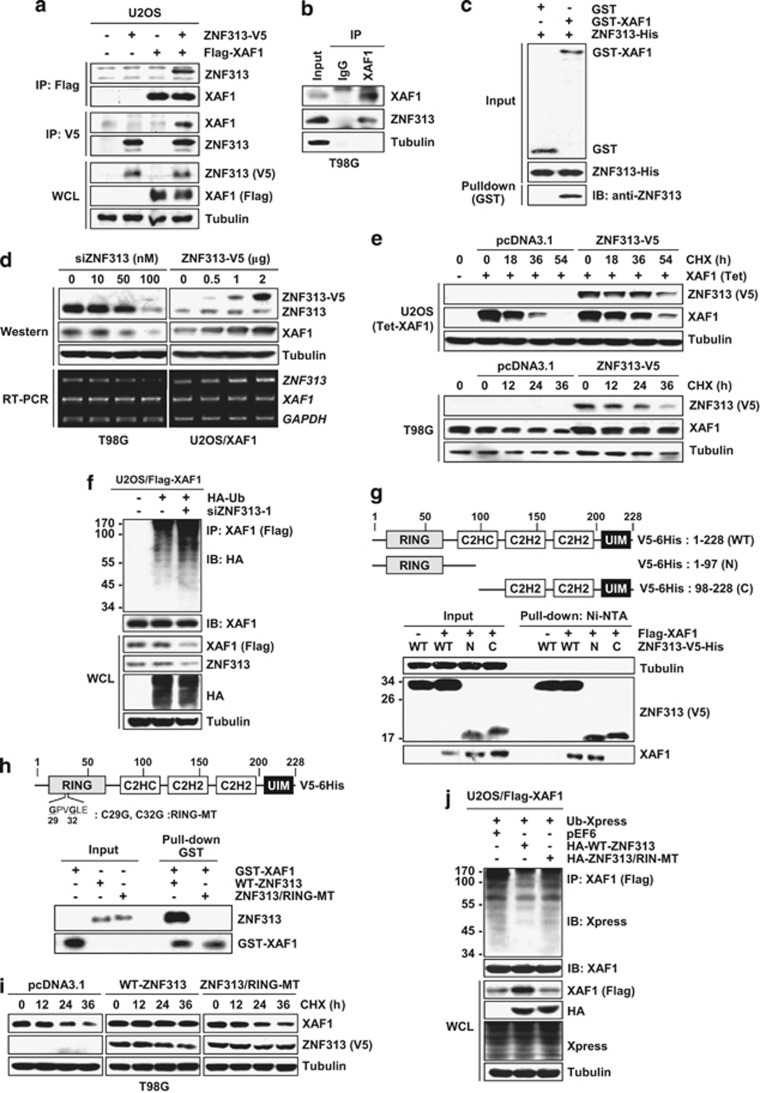

Identification of ZNF313 as a XAF1-stabilizing protein

As an attempt to identify XAF1-interacting proteins, we initially performed a yeast-two hybrid analysis. Among 121 positive colonies detected, 36 (29.8%) represented ZNF313 (Supplementary Figures S1a–d). The XAF1–ZNF313 interaction was confirmed by immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assays (Figures 1a–c). XAF1 protein level was down- and upregulated by depletion and elevation of ZNF313, respectively, and XAF1-reducing effect of three different siZNF313s showed an association with ZNF313 knockdown efficiency (Figure 1d and Supplementary Figure S1e). A cycloheximide chase experiment revealed that the half-life of XAF1 protein is increased and decreased by expression and depletion of ZNF313, respectively (Figure 1e and Supplementary Figures S1f and g). Moreover, XAF1 ubiquitination was increased by ZNF313 depletion, indicating that ZNF313 enhances XAF1 stability by protecting its ubiquitination (Figure 1f). It was also found that the N-terminal RING domain of ZNF313 is essential for its binding to XAF1 (Figure 1g). The critical role for the RING domain in the interaction with XAF1 was validated using a RING mutant (RING-MT), which has C-to-G sequence replacement at codons 29 and 32 (Figure 1h). As predicted, both degradation and ubiquitination of XAF1 were not protected by the RING-MT (Figures 1i and j). These results indicate that ZNF313 protects XAF1 from ubiquitination and degradation through the RING domain-mediated interaction.

Figure 1.

ZNF313 interacts and stabilizes XAF1 protein. (a) An immunoprecipitation (IP) assay for validation of XAF1–ZNF313 interaction. (b) A XAF1–ZNF313 interaction in T98G breast cancer cells. (c) A pull-down assay for the direct interaction between XAF1 and ZNF313. (d) ZNF313 upregulation of XAF1. T98G and U2OS/XAF1 cells were transfected with siZNF313 and wild-type (WT)-ZNF313-V5, respectively, and its effect on XAF1 level was determined after 48 h. Western blot was performed using anti-ZNF313 or anti-XAF1 antibody. (e) ZNF313 upregulation of XAF1 stability. Effect of ZNF313 on XAF1 stability was analyzed using cycloheximide (CHX) chase experiment. (f) Increased ubiquitination of XAF1 by ZNF313 depletion. U2OS/Flag-XAF1 cells were transfected with siZNF313 and XAF1 ubiquitination was measured by an immunoprecipitation assay. (g) Characterization of XAF1-interacting region of ZNF313. WT and deletion mutants of ZNF313 were pulled down using Ni-NTA. (h) A GST pull-down assay for the XAF1-interacting activity of ZNF313/RING-MT. (i) Loss of XAF1-stabilizing activity of ZNF313 by RING mutation. T98G transfected with WT or RING-MT ZNF313 were treated with CHX and XAF1 level was measured by immunoblot assay. (j) Loss of ZNF313 effect on XAF1 ubiquitination by RING mutation. C, control; GST, glutathionine S-transferase; HA, hemagglutinin; IB, immunoblotting; N, normal; RING, Really Interesting New Gene; Ub, ubiquitin; UIM, ubiquitin-interacting motif; WCL, whole-cell lysate; WT, wild-type

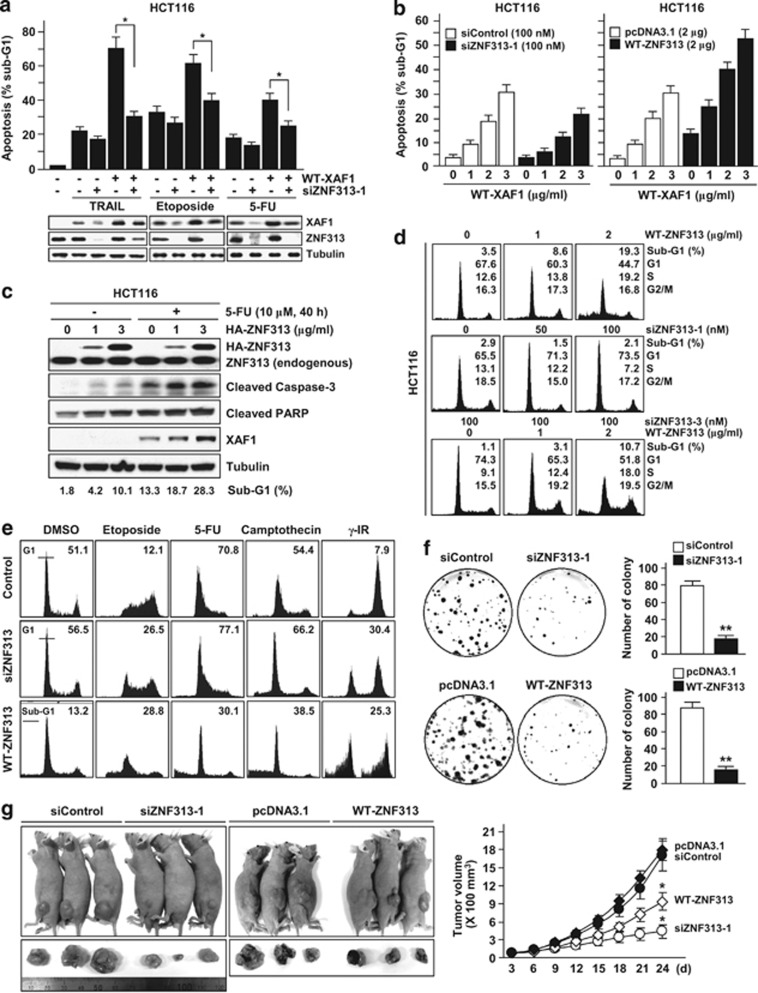

ZNF313 is a novel cell cycle activator with proapoptotic potential

We evaluated the effect of ZNF313 on XAF1's proapoptotic function. ZNF313 depletion led to a significant reduction of XAF1's ability to enhance cellular response to apoptotic stresses, such as TRAIL, etoposide and 5-FU (Figure 2a). In the absence of stresses, XAF1-induced apoptosis was also down- and upregulated by depletion and elevation of ZNF313, respectively (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure S2a). Moreover, overexpression of ZNF313 itself triggered apoptosis, which was evident by increased cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP (Figures 2b and c). ZNF313 induction of apoptosis was also seen in XAF1-depleted T98G cells (Supplementary Figure S2b). These results show that ZNF313 elevation could induce apoptosis in both XAF1-dependent and -independent ways.

Figure 2.

ZNF313 stimulates apoptosis and cell cycle progression. (a) ZNF313 depletion attenuates proapoptotic effect of XAF1. HCT116 cells transfected with WT-XAF1 and/or siZNF313 were exposed to TRAIL (10 ng/ml), etoposide (10 μM) and 5-FU (10 μM) for 48 h and apoptotic sub-G1 fraction was measured by flow cytometry. Data represent means of triplicate assays (bars, S.D.) (*P<0.05). (b) ZNF313 effect on XAF1-induced apoptosis. (c) ZNF313 effect on basal and 5-FU-induced apoptosis. (d) ZNF313 stimulation of a G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle and rescue of siZNF313-induced G1 arrest by co-transfection of WT-ZNF313. (e) ZNF313 effect on cellular response to genotoxic stresses. HCT116 cells transfected with siZNF313 or WT-ZNF313 were exposed to various genotoxic stresses. The G1 arrest and apoptotic response of the cells were determined by flow cytometry. (f) Effect of ZNF313 on colony-forming ability of HCT116 cells (**P<0.01). (g) Effect of ZNF313 on xenograft tumor growth of HCT116 (*P<0.05). DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; HA, hemagglutinin; IR, irradiation; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; WT, wild-type

Next, we defined the possible role for ZNF313 in cell cycle regulation. Ectopic expression of ZNF313 facilitated a G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle followed by apoptosis induction, while its depletion caused a G1 arrest (Figure 2d). The G1 arrest-inducing effect of three siZNF313s also correlated with ZNF313 knockdown efficiency (Supplementary Figure S2c). Moreover, the G1 arrest induced by siZNF313-3, which targets the 3′-untranslated region of the transcript, was rescued by co-transfection of WT-ZNF313 (Figure 2d and Supplementary Figure S2d). In addition, ZNF313-depleted cells showed enhanced G1 arrest response to various therapeutic agents, including etoposide, camptothecin and γ-IR, whereas ZNF313-overexpressing cells displayed attenuated G1 arrest response, which is linked to increased apoptosis (Figure 2e). These findings indicate that ZNF313 has a mitogenic function and that its deregulation can disturb cell cycle control mechanism and thus influence cellular response to stresses. Indeed, we observed that either depletion or overexpression of ZNF313 greatly decreases colony-forming ability and xenograft tumor growth of HCT116 (Figures 2f and g).

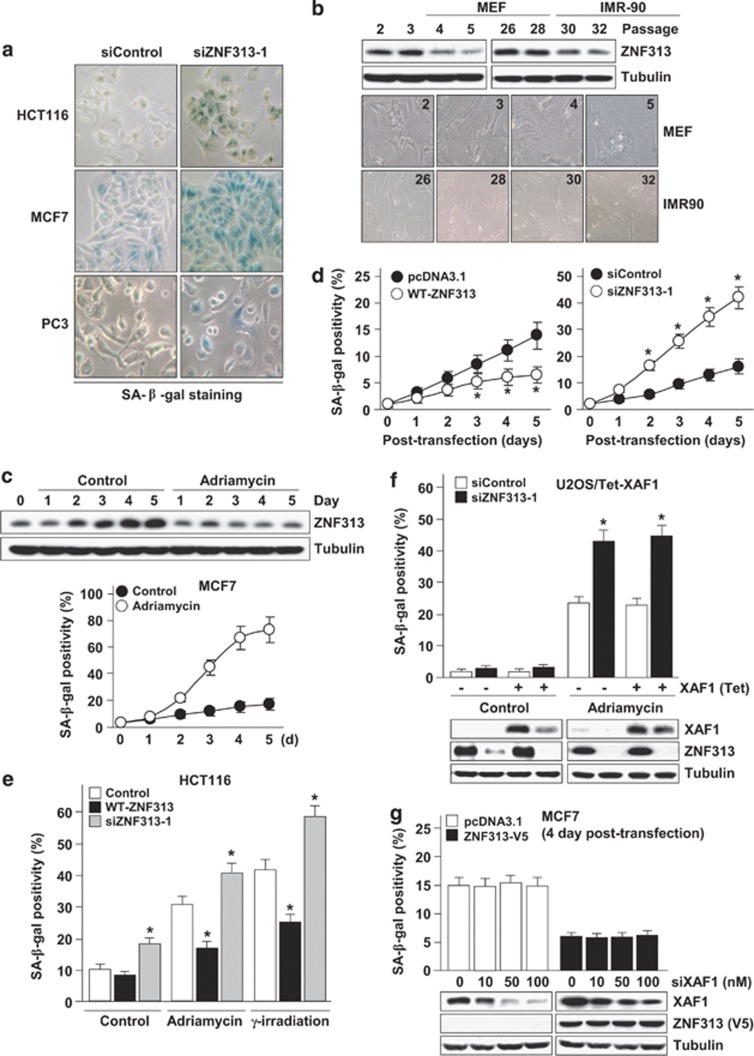

ZNF313 is a negative regulator of cellular senescence

To understand the molecular basis for the cell cycle regulation by ZNF313, we further defined its effect on cellular growth. Intriguingly, we found that ZNF313 depletion triggers cellular senescence in various human cancer cells (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S3a). Moreover, ZNF313 expression was substantially lower in senescent versus young cells and its level correlated inversely with the replicative senescence of mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) and human fetal lung fibroblast (IMR90) (Figure 3b). It was also observed that adriamycin-induced senescence of MCF7 cells is accompanied with ZNF313 reduction and that basal senescence is suppressed and stimulated by elevation and depletion of ZNF313, respectively (Figures 3c and d). Similarly, adriamycin- or γ-IR-induced senescence of HCT116 cells was down- and upregulated by WT-ZNF313 and siZNF313, respectively (Figure 3e). ZNF313 inhibited basal or adriamycin-induced senescence in the presence or absence of XAF1 expression (Figures 3f and g). Both p53+/+ and p53−/− sublines of HCT116 exhibited clear induction of senescence after ZNF313 depletion (Supplementary Figure S3b and c). These results indicate that ZNF313 is a negative regulator of cellular senescence and its reduction promotes senescence in a XAF1- and p53-independent manner.

Figure 3.

ZNF313 is a negative regulator of cellular senescence. (a) Induction of cellular senescence by ZNF313 depletion. Cellular senescence was measured by Senescence-associated (SA)-β-gal assay. (b) Downregulation of ZNF313 expression during replicative senescence in MEF and IMR-90 cells. (c) Downregulation of ZNF313 expression in adriamycin-induced cellular senescence of MCF7. (d) ZNF313 effect on cellular senescence. MCF7 cells were transfected with WT-ZNF313 (2 μg/ml) or siZNF313 (50 nM) and cellular senescence was examined using SA-β-gal assay. Data represent means of triplicate assays (bars, S.D.) (*P<0.05). (e) Elevation or depletion of ZNF313 expression significantly affects DNA damage-induced cellular senescence. (f) A XAF1-independency of ZNF313 regulation of cellular senescence. U2OS/Tet-XAF1 cells transfected with siZNF313 or siControl were exposed to tetracycline for XAF1 induction and adriamycin-induced cellular senescence was analyzed using SA-β-gal assay. (g) No effect of XAF1 on ZNF313 suppression of senescence. MCF7 cells were co-transfected with empty vectors or ZNF313-V5 and increasing doses of siXAF1. Cellular senescence was examined using SA-β-gal assay at 4 days after transfection

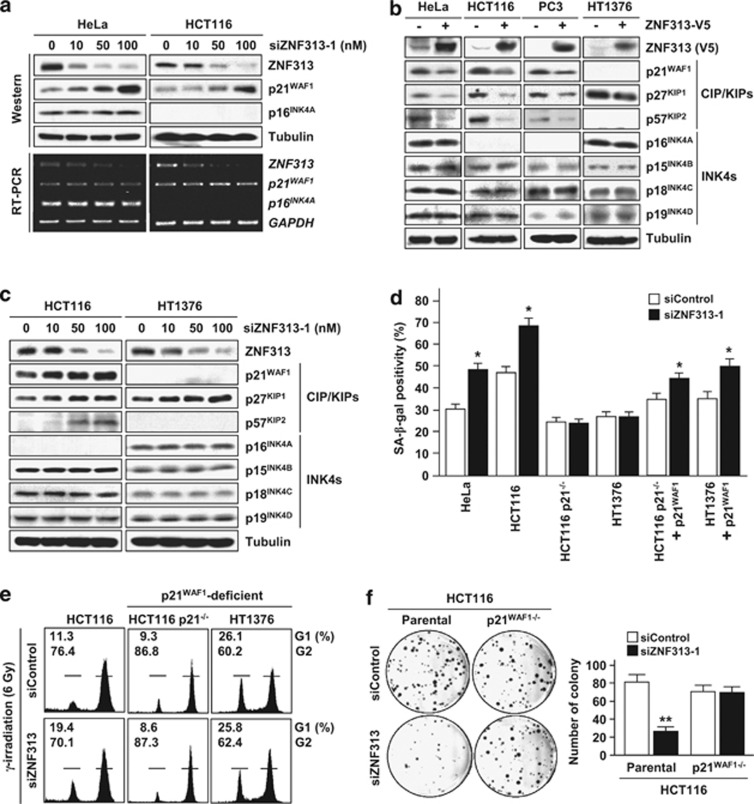

ZNF313 is a specific antagonist of the CIP/KIP family members of CDK inhibitors

We tested the possibility that ZNF313 regulates p21WAF1 and p16INK4A, which have key roles in cellular senescence.20, 21, 22, 23 ZNF313 depletion resulted in a dramatic increase in p21WAF1 but did not affect the p16INK4A level (Figure 4a). Elevation of p21WAF1 protein by siZNF313-3 was abolished by WT-ZNF313 co-transfection (Supplementary Figure S4a). Intriguingly, ZNF313 downregulated the CIP/KIP family members (p21WAF1, p27KIP1 and p57KIP2) of CDK inhibitors but did not affect the INK4 family members (p16INK4A, p15INK4B, p18INK4C and p19INK4D) (Figures 4b and c). Unlikely functional p21WAF1-carrying cells, senescence of HCT116 p21−/− and HT1376 cells harboring the premature termination mutation of the p21WAF1 gene was not promoted by ZNF313 depletion.24, 25 However, its senescence-enhancing activity was restored when p21WAF1 is re-expressed in these cells (Figure 4d and Supplementary Figure S4b). ZNF313-depleted HCT116 cells showed an increased G1 arrest following IR exposure, but this effect was not seen in p21WAF1-deficient cells (Figure 4e). Consistently, colony-forming ability of HCT116 p21−/− cells was not reduced by ZNF313 depletion (Figure 4f and Supplementary Figure S4c). It was also found that ZNF313 downregulates p21WAF1 in both p53+/+ and p53−/− cells (Supplementary Figures S4d and e). In addition, senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) was not increased by ZNF313 depletion, which is in line with previous reports that SAHF formation depends on p16INK4A induction (Supplementary Figure S4f).26, 27 These results indicate that ZNF313 is a specific inhibitor of the CIP/KIP family members of CDK inhibitors and exerts a profound effect on cell proliferation and senescence by inhibiting p21WAF1.

Figure 4.

ZNF313 destabilizes CIP/KIP proteins and blocks p21WAF1-mediated cellular senescence. (a) ZNF313 depletion leads to elevation of p21WAF1 but not of p16INK4A protein level. (b) ZNF313 downregulates CIP/KIP but not INK4 family members. (c) A dose-associated elevation of p21WAF1, p27KIP1 and p57KIP2 protein level by siZNF313 transfection. (d) No effect of ZNF313 on cellular senescence of p21WAF1-deficient cells and the recovery of its effect in p21WAF1-restored cells. Senescence-associated (SA)-β-gal assay was performed 5 days after adriamycin treatment (0.5 μg/ml, 2 h). Data represent means of triplicate assays (bars, S.D.) (*P<0.05). (e) No effect of ZNF313 depletion on irradiation-induced G1 cell cycle arrest in p21WAF1-deficient cells. (f) A p21WAF1-dependent effect of ZNF313 on colony formation of tumor cells. HCT116 and its p21−/− subline were transfected with siZNF313 and its effect on colony-forming ability was compared (**P<0.01)

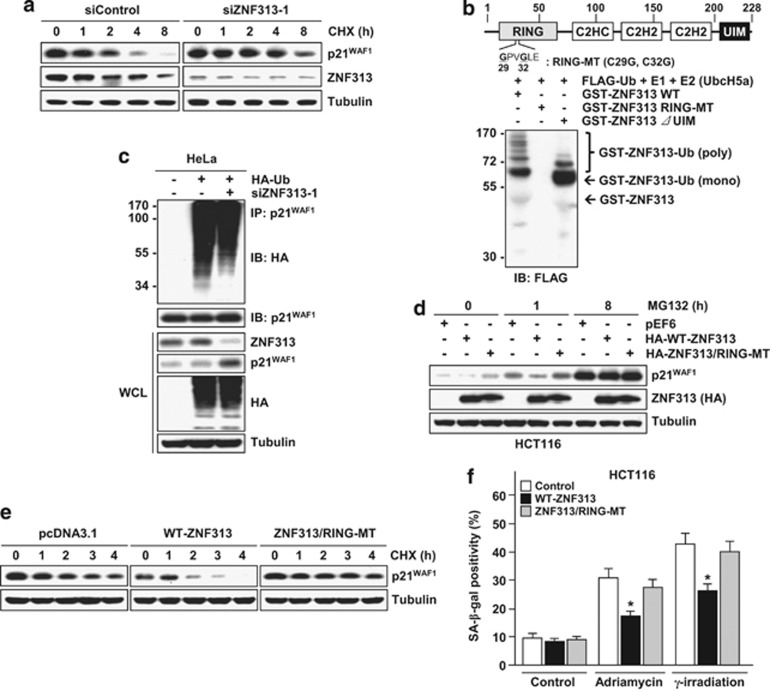

ZNF313 promotes ubiquitination and degradation of p21WAF1

Next, we analyzed p21WAF1-moduating effect of ZNF313. ZNF313 depletion resulted in a marked increase in p21WAF1 protein stability (Figure 5a). To ascertain whether this effect stems from its presumed ubiquitin ligase activity, we tested that ZNF313 has an E3 ligase function by evaluating its self-ubiquitination activity utilizing various E2 enzymes. ZNF313 was polyubiquitinated in the presence of UbcH5a, UbcH5b and UbcH5c, but only monoubiquitinated in the presence of UbcH6 (Figure 5b and Supplementary Figure S5a). The RING domain was required for its E3 ligase function, while the UIM domain has a role in polyubiquitination (Supplementary Figure S5b). Consistently, ZNF313 depletion attenuated p21WAF1 ubiquitination, while RING-MT fails to destabilize p21WAF1, indicating that the RING domain is crucial for ZNF313-induced p21WAF1 degradation (Figures 5c–e). As predicted, RING-MT also failed to suppress cellular senescence induced by adriamycin or γ-IR in HCT116 cells (Figure 5f). These findings thus indicate that ZNF313 is a novel ubiquitin E3 ligase for p21WAF1.

Figure 5.

ZNF313 is a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase for p21WAF1. (a) Elevation of p21WAF1 protein stability in ZNF313-depleted HCT116 cells. (b) Validation of the E3 ligase activity of ZNF313. A self-ubiquitination activity of ZNF313 was tested using wild-type, RING-MT and ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) deletion mutants. (c) Decreased ubiquitination of p21WAF1 by ZNF313 depletion. (d) Loss of p21WAF1-destabilizing activity of ZNF313 by RING mutation. (e) Comparison of p21WAF1-destabilizing activity of WT- and RING-mutated ZNF313. (f) Loss of senescence-inhibiting activity of ZNF313 by RING mutation. CHX, cycloheximide; HA, hemagglutinin; IB, immunoblotting; RING, Really Interesting New Gene; SA, senescence-associated; Ub, ubiquitin; UIM, ubiquitin-interacting motif; WT, wild type

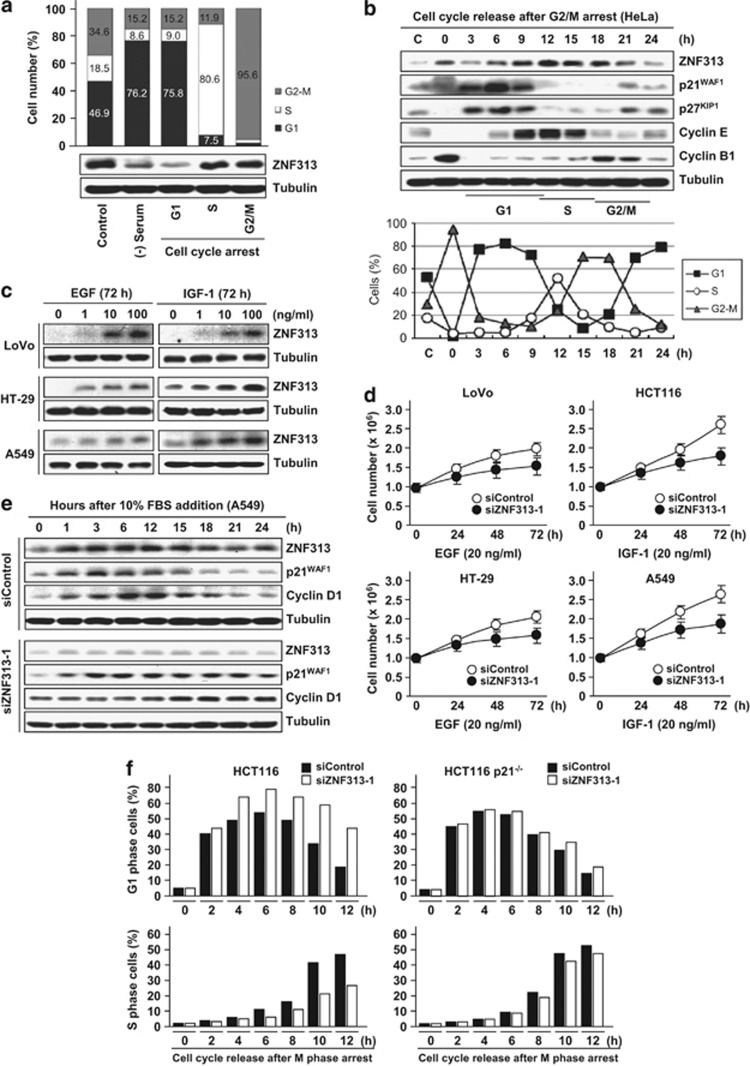

ZNF313 stimulates a G1-to-S phase transition of the cell cycle

To address the role for ZNF313 in cell cycle regulation, we initially determined its expression pattern during cell cycle progression using cell cycle arrest by serum withdrawal (G1), double thymidine block (S) and nocodazole (G2/M). We found that ZNF313 expression is low at the G1 phase but very high at the S and G2/M phase, suggesting that its elevation may drive a G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle (Figure 6a and Supplementary Figures S6a and b). To clarify this, HeLa cells were synchronized at the M phase by thymidine-nocodazole-mitotic shake off method and ZNF313 level was measured at 3-h interval following serum re-addition (Supplementary Figure S6c). ZNF313 expression was reduced during an M-to-G1 transition and maintained at low level at early and mid-G1 phase (Figure 6b). ZNF313 started to be increased at late G1 phase and showed the highest level during the S phase followed by slow reduction at the G2/M phase. ZNF313 expression showed an inverse correlation with those of p21WAF1 and p27KIP1 through the entire cell cycle. The inverse correlation was also observed in HCT116 cells released from G1 synchronization (Supplementary Figure S6d). The G1-to-S transition was facilitated by ectopic expression of ZNF313 but substantially blocked by its depletion in various tumor cells (Supplementary Figure S6e).

Figure 6.

ZNF313 is an inducer of a G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle. (a) Cell cycle-associated regulation of ZNF313 expression. HeLa cells were synchronized at the G1, S and G2/M phase of the cell cycle by serum starvation, thymidine block and nocodazole treatment, respectively. (b) Expression kinetics of ZNF313 during the cell cycle and its association with p21WAF1 expression. HeLa cells were synchronized at the M phase by thymidine-nocodazole-mitotic shake-off method and then released by the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). (c) Induction of ZNF313 expression by growth factors. (d) Attenuation of growth factor-induced cellular growth by ZNF313 depletion. (e) Sustained elevation of p21WAF1 and delayed induction of cyclin D1 in ZNF313-depleted A549 cells after 10% FBS addition. (f) Comparison of ZNF313 effect on a G1-to-S cell cycle transition. ZNF313-depleted HCT116 and its p21−/− subline cells were arrested at the M phase and then released by serum addition. Cell cycle progression was analyzed by flow cytometry. C, control; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IGF, insulin growth factor

We tested whether ZNF313 has a role in growth factor-induced cell proliferation. ZNF313 expression was induced by EGF, IGF-1 and FGF, and its induction level was associated with cellular responsiveness to growth factors (Figure 6c and d and Supplementary Figure S6f). In serum-starved A549 cells, ZNF313 was rapidly increased following serum addition and its elevation was maintained up to 15 h, whereas p21WAF1 was initially upregulated in response to serum addition and subsequently decreased (Figure 6e). In contrast, in ZNF313-depleted cells, p21WAF1 elevation was sustained up to 24 h and cyclin D1 induction was markedly delayed, indicating that the ZNF313 activation and consequent p21WAF1 reduction is crucial for cell cycle progression by growth factors. Consistently, in M phase-arrested HCT116 cells, a G1-to-S transition by serum addition was profoundly delayed by ZNF313 depletion, but this effect was greatly weakened in p21−/− subline (Figure 6f). These results show that ZNF313 expression is tightly controlled during the cell cycle and its elevation and subsequent p21WAF1 degradation at late G1 phase is critical for a G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle.

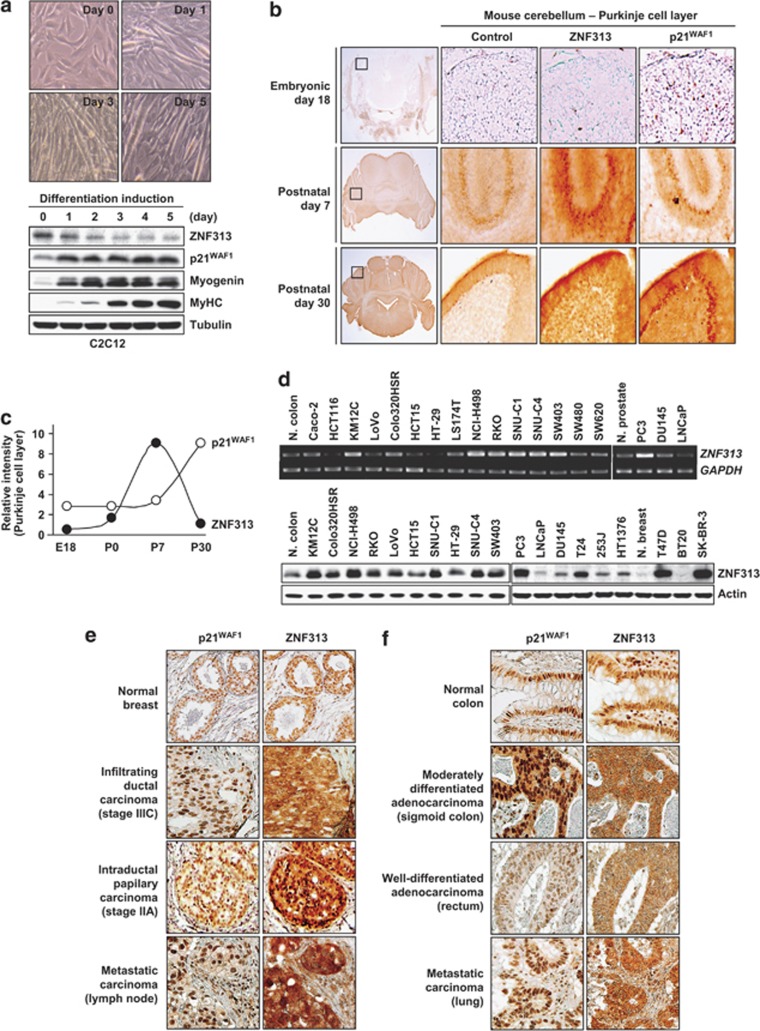

ZNF313 is reduced in differentiation process and elevated in cancer cells

Next, we tested whether ZNF313 is involved in the regulation of cellular differentiation. In myotube formation process of C2C12 myoblasts, ZNF313 was decreased continuously, while p21WAF1 was increased up to 5 days after horse serum addition (Figure 7a). An immunohistochemical analysis of developing mouse cerebellum also showed that ZNF313 is barely detectable in embryonic cerebellar nucleus but greatly up- and downregulated in Purkinje cell layer at postnatal day 7 (P7) and day 30 (P30), respectively (Figures 7b and c). In contrast, p21WAF1 was detectable in embryonic cells but down- and upregulated at P7 and P30, respectively. An inverse correlation between ZNF313 and p21WAF1 was also detected in cerebellar lobe and lateral vestibular nucleus (Supplementary Figure S7a). These findings show that ZNF313 reduction and concomitant p21WAF1 elevation are associated with cerebellar differentiation.

Figure 7.

ZNF313 is decreased in differentiated cells and increased in tumor cells. (a) ZNF313 downregulation in muscle differentiation process. C2C12 mouse myoblasts were exposed to 2% horse serum to induce myotube formation. (b) Expression of ZNF313 and p21WAF1 in differentiating mouse brain. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using IgG (control) or monoclonal antibody against ZNF313 or p21WAF1. (c) Expression kinetics of ZNF313 and p21WAF1 in Purkinje cell layer in developing mouse brain. (d) Elevation of ZNF313 expression in human cancer cells compared with corresponding normal (N) tissues. (e, f) ZNF313 and p21WAF1 expression in breast and colorectal cancer tissues. ZNF313 exhibits more intense cytoplasmic expression in primary and metastatic carcinomas compared with normal epithelial tissues

We next examined the expression and mutational status of ZNF313 in various human cancer cells derived from colon, breast, prostate and bladder tumors. Compared with normal tissues, 29 of 70 (41.4%) cancer cells showed substantially elevated ZNF313 at both mRNA and protein level (Figure 7d and Supplementary Figure S7b). However, nucleotide sequence substitutions of the gene were not found in cancer cells. We next characterized ZNF313 expression in a series of primary and metastatic tumors (Figures 7e and f). In normal breast and colonic epithelial cells, ZNF313 was detected both in the nucleus and cytoplasm, while p21WAF1 was localized predominantly in the nucleus. Interestingly, substantial fraction of cancer specimens (35 of 50 (70%) breast and 41 of 50 (82%) colon cancers) we tested displayed strong cytoplasmic positivity of ZNF313, which was accompanied with reduced nuclear expression, suggesting that the subcellular distribution of ZNF313 might be deregulated in malignant tumor cells (Table 1). Although numbers of specimens examined were small, the strong cytoplasmic positivity of ZNF313 was more common in advanced versus early cancers and metastatic versus primary tumors (Figure 7e and f). These observations thus suggest that ZNF313 may have a role as a negative regulator of cellular differentiation and its altered expression contribute to the malignant transformation and/or progression of epithelial tumors.

Table 1. Expression status of ZNF313 in normal and cancer tissuesa.

| Specimens | Number |

ZNF313 expression |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N>C | N<C | ||

| Breast | |||

| Normal | 10 | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) |

| Carcinoma | 50 | 15 (30.0) | 35 (70.0) |

| Stage | |||

| T2 | 33 | 13 (39.3) | 20 (60.6) |

| T3 | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) |

| Metastasis | 9 | 1 (11.1) | 8 (88.9) |

| Colon | |||

| Normal | 10 | 10 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| Carcinoma | 50 | 9 (18.0) | 41 (82.0) |

| Stage | |||

| T2 | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| T3 | 34 | 6 (17.6) | 28 (82.3) |

| T4 | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100) |

| Metastasis | 10 | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) |

Abbreviations: C, cytoplasm; N, nucleus

Numbers within parentheses are percentage.

Discussion

In this study, we identified ZNF313 as a XAF1-interacting protein, whose elevation promotes apoptosis through a XAF1-dependent or -independent mechanism. Our study also shows that ZNF313 facilitates cell cycle progression and its elevation is associated with tumor progression, suggesting its oncogenic property. The growth-promoting and apoptosis-inducing effects of ZNF313 and its tumor-associated elevation raise the possibility that apoptosis evoked by ZNF313 might be linked to its mitogenic property, as known by the so-called ‘oncogene-induced apoptosis'. It is thus conceivable that aberrant cell proliferation or the disturbance of cell cycle regulation by abnormal activation of ZNF313 could provoke stress signaling, which is accompanied with enhanced XAF1 stability by increased complex formation with ZNF313. In this context, frequent epigenetic inactivation of XAF1 observed in various types of human cancers may provide both survival and selective growth advantages for ZNF313-overexpressing tumor cells.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

XAF1 is activated by IFN and its activation increases cellular sensitivity to IFN- and TRAIL-induced apoptosis.17, 18, 19 ZNF313 has been shown to be induced by type I IFN and regulates a positive feedback loop leading to the production of IFN.17, 18, 19 ZNF313 was also reported as a positive regulator of the RIG-1/MDA5 innate antiviral response, suggesting its implication in epithelial inflammation and the pathogenesis of immune-mediated conditions.7 Our finding thus strongly suggests that ZNF313 and XAF1 may cooperate for the regulation of IFN signaling. The p53 tumor suppressor is induced in response to viral infections as a transcriptional target of type I IFN signaling and contributes to innate immunity by enhancing IFN-dependent antiviral activity.28, 29 IFNα/β signaling also contributes to boosting p53 responses to stress signals and p53 activated in virally infected cells evokes an apoptotic response. It is worth noting that XAF1 can enhance p53 stability and its apoptotic activity.16, 30 Interestingly, our data show that ZNF313 has an apoptosis-inducing function and its elevation greatly enhances cellular response to apoptotic stresses. Therefore, our data raise the possibility that the ZNF313–XAF1 complex might have a role in antiviral defense by contributing to the p53-dependent enhancement of IFN signaling.

Recent studies demonstrated that the N-terminal RING domain of ZNF313 has an E3 ligase activity and its C-terminal UIM can bind polyubiquitin.4, 5 However, intracellular targets for ZNF313 have not been identified yet. We observed that ZNF313 destabilizes p21WAF1, p27KIP1 and p57KIP2 but not the INK4 family members of the CDK inhibitors, and this effect is abolished by a mutation of the RING domain, confirming that the RING domain is critical for its E3 ligase function. ZNF313 expression is tightly regulated during the cell cycle and its elevation is linked to p21WAF1 degradation and a G1-to-S transition of the cell cycle. Moreover, ZNF313 is activated by multiple growth factors and its depletion profoundly attenuates their mitogenic effect. Many mitogenic factors and signaling molecules evoke their effects by modulating p21WAF1 protein stability. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and bone morphogenetic protein 2 inhibits colon cell growth through enhancing p21WAF1 stability, while JUN amino-terminal kinase 1 promotes growth arrest by inhibiting p21WAF1 ubiquitination.31, 32, 33 In this light, our finding leads to the conjecture that oncogenic growth factors may downregulate the protein stability of p21WAF1, p27KIP1 or p57KIP2 via ZNF313 induction and their tumor-promoting effect could be further intensified in ZNF313-elevated cells. In addition, ZNF313 was found to inhibit cellular senescence in a p21WAF1-dependent manner, while its blockade accelerates cellular senescence in p21WAF1-intact cells but not in p21WAF1-deficient cells. Collectively, these indicate that ZNF313 is a novel E3 ligase for p21WAF1, which antagonizes p21WAF1-mediated cell cycle inhibition and cellular senescence.

P21WAF1 has a crucial role as an effector of multiple growth suppressor pathways and mediates both p53-dependent and -independent cell cycle arrest, while it also promotes cellular proliferation and exerts antiapoptotic effect, depending on the cellular context and circumstances.34, 35 Newly formed p21WAF1 is stabilized by FKBPL/WISP39, an adaptor that recruits HSP90 to p21WAF1, while its ubiquitination and degradation are promoted by three E3 ligase complexes SCF-SKP2, CRL4-CDT2 and APC/C-CDC20.36, 37, 38 This study provides evidence supporting that ZNF313 is a novel E3 ligase of p21WAF1, which promotes its ubiquitination and degradation in response to multiple proliferative signals. ZNF313 depletion does not influence both the time and level of p21WAF1 protein formation, while it profoundly delayed p21WAF1 degradation, indicating that ZNF313 controls stability of p21WAF1 but not of its synthesis. Several proteins involved in the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of p21WAF1, such as SKP2, CDT2 and CUL4A, are elevated in a variety of human tumors.39, 40, 41 However, a causal link between their p21WAF1 suppression function and oncogenic activity has not been firmly defined. Our study reveals that ZNF313 is upregulated commonly in multiple human tumor cells and tissues. Moreover, ZNF313 is progressively downregulated in cellular differentiation process in vitro and in vivo and its expression pattern correlates inversely with that of p21WAF1. In addition, ZNF313 inhibition of cellular senescence is disrupted by RING domain mutation. These findings thus suggest that abnormal elevation of ZNF313 may contribute to tumor development or progression by suppressing cellular differentiation and senescence at least partially through p21WAF1 destabilization.

Human chromosome 20q13 exhibits frequent genomic amplification in various human cancers.3, 6, 7 A recent study also revealed that 20q12–q13.3 is the most frequently amplified region in gastric cancer.42 Several genes located at this locus, such as AIB1 and BCAS1, have been shown to be involved in growth and aggressiveness of human cancers.43, 44 However, biological functions of putative tumor-promoting genes in this region have not been well characterized. Our study suggests that ZNF313 might be a candidate proto-oncogene located at 20q13. We detected that approximately 41% (29 of 70) of human cancer cells derived from colon, breast, prostate, bladder and gastric tumors display strong expression of ZNF313 at both mRNA and protein level. Although specimen numbers we tested are not enough to draw a conclusion, our study also show that ZNF313 is more highly expressed in tumor versus normal tissues and its strong positivity is more frequent in advanced versus early cancers and metastatic versus primary tumors, supporting that altered expression of ZNF313 may contribute to malignant tumor progression.

In summary, we have shown that ZNF313 is a novel cell cycle activator, which promotes ubiquitination and degradation of p21WAF1. ZNF313 is activated by multiple growth factors and commonly upregulated in human cancers. ZNF313 inhibits cellular senescence and its downregulation is associated with cellular differentiation. Our findings provide an insight into the mechanisms underlying the biological role of ZNF313, and suggest that ZNF313 alteration may contribute to the pathogenesis of multiple human diseases and represent a new therapeutic target against human cancers.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and construction of stable cell lines

Human and mouse cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) or Korea Cell Line Bank (Seoul, South Korea). P53−/− and p21−/− sublines of HCT116 were provided by B Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA). Primary mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs) were prepared from a 13.5-day postcoitum ICR embryo. C2C12 cells were treated with 2% horse serum to induce myotube formation. U2OS/Tet-XAF1 cells were generated by co-transfection of XAF1 (pcDNA4/TO) and tetracycline repressor vector (pcDNA6/TR) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and selection under blasticidin S (5 μg/ml) and zeocin (100 μg/ml). Cell cycle synchronization was achieved by serum starvation (G1), thymidine block (S), nocodazole treatment (G2–M) or mitotic shake-off (M), and validated using flow cytometry.

Yeast two-hybrid assay

Human liver cDNA library in Y187 yeast strain was purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA). A full-length XAF1 was cloned into the pGBKT7 (Clontech) and transformed into AH109 yeast strain. A screening was performed by mating the two strains and plating those on a quadruple dropout medium. To confirm the interaction, the β-galactosidase activity was measured according to the standard protocol.

Immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assay

Cells were lysed in a buffer containing MG132 (10 μM) and protease inhibitor cocktail. One milligram of total protein was incubated with antibodies for 3 h and then mixed with 50 μl of Protein A/G-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 2 h. For in vitro binding, GST- or 6His-fused recombinant proteins overexpressed by IPTG in BL21 strain were purified using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) or Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). GST or Ni-NTA pull-down assay was conducted by incubating target proteins for 2 h.

Immunoblotting, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry assay

Immunoblot analyses were performed using antibodies specific for XAF1 (C-16), ZNF313 (SM-3), p21WAF1, p27KIP1, p57KIP2 (C-20), p16INK4A (C-20) and cyclin D1 (A-12) purchased from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology. For immunofluorescence assay, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin-PBS. Slides were incubated with anti-ZNF313 or anti-p21WAF1 antibody and fluorescent imaging was obtained with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). An immunohistochemical assay for human cancer tissues was carried out using tissue arrays (SuperBioChips Laboratory, Seoul, South Korea). Briefly, slides were incubated with ZNF313 or p21WAF1 antibody overnight at 4 °C using biotin-free polymeric horseradish peroxidase-linker antibody conjugate system. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and visualized using an Olympus CK40 microscopy (Tokyo, Japan). Mouse brain tissues at embryonic day 18 (E18) and P0, P7 and P30 were prepared as described previously.45

Semiquantitative RT-PCR assay

Our strategy for the semiquantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis was described previously.16 Briefly, 1 μg of DNase1-treated RNA was converted to cDNA by RT using random hexamer primers and MoMuLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). PCR was performed using 2 μl of 1 : 4 diluted cDNA (12.5 ng/50 μl PCR reaction) for 30–34 cycles at 95 °C (1 min), 58–62 °C (0.5 min) and 72 °C (1 min). Primer sequences are available upon request. Quantitation was achieved by densitometric scanning of the ethidium bromide-stained gels and analysis was performed using the Molecular Analyst software program (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Expression plasmids, siRNA and transfection

Expression vectors for ZNF313 and XAF1 were constructed using a PCR-based approach as described previously.15, 16 Short-interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes against ZNF313 (siZNF313-1: 5′-GCUGCCGUAAGAAUUUCUU-3′ siZNF313-2: 5′-GCCACCAUUAAGGAUGCA-3′ and siZNF313-3: 5′-GGUCGAGUUCGUAUUGGUU-3′) and XAF1 (5′-AUGUUGUCCAGACUCAGAG-3′) and control siRNA duplex that served as a negative control were synthesized by Dharmacon Research (Lafayette, CO, USA). Transfection of siRNA was performed using siRNA-Oligofectamine mixture or electroporation (Neon transfection system; Invitrogen).

Cell cycle, apoptosis and colony formation assay

Cells were seeded at the density of 5 × 104 cells and transfected with expression vector or siRNA. Cell numbers were counted using a hemocytometer at 24-h intervals. For cell cycle analysis, cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing 100 μg/ml RNase and 50 mg/ml propidium iodide. The assay was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and the cell cycle profile was analyzed using MultiCycle software (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA, USA). For colony formation assay, 1 × 104 cells transfected with expression vectors were seeded in a 6-well plate and selected under 200 μg/ml of zeocin up to 2–3 weeks.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity assay

Cells were fixed in PBS with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and incubated in citric acid/disodium phosphate buffer (40 mM, pH 6.0) containing 1 mg/ml of X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-𝒟-galactopyranoside) and potassium ferricyanide (50 mM) at 37 °C for 16 h. To analyze SAHF formation, cells were stained with DAPI and analyzed by confocal microscopy.

Ubiquitination assay

Recombinant GST-ZNF313 proteins were purified from Escherichia coli as described above. For in vitro self-ubiquitination assay, 1 μg of bead-bound control GST or GST-fused proteins were incubated with 500 ng of Flag-ubiquitin, 500 ng of UBE1 and 500 ng of E2 enzymes in buffer containing 2 mM ATP for 1.5 h. Purified Flag-ubiquitin, UBE1 and E2s were purchased from Boston Biochem (Cambridge, MA, USA). For ubiquitination assay, U2OS/Flag-XAF1 and HeLa cells were transfected with HA-Ub or Xpress-Ub plasmids and siZNF313 or ZNF313 expression plasmids by Neon Electroporator (Invitrogen). After 24-h transfection, the cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 h and the cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag- or anti-p21WAF1-conjugated agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 10 h. Immunoprecipitation was carried out using three different buffer systems (mild-buffer, RIPA-based buffer and harsh-conditioned systems) and precipitated proteins were analyzed by western blot assay.

Animal studies

Four-week-old immunodeficient male nude mice (nu/nu) (Orient Bio Inc., Sungnam, Korea) were maintained in pressurized ventilated cages. For xenograft assay, cells (1 × 107) were injected subcutaneously into six mice and tumor growth was monitored periodically and volume (V) was calculated using the modified ellipsoidal formula V=1/2 × length × (width).2 All animal studies were carried out with the approval of Korea University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and Korea Animal Protection Law.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using a one-way analysis of variance and statistical values were presented as a mean±the standard error of the mean. Throughout, P<0.05 was regarded as significant.

Acknowledgments

For expert technical assistance and helpful discussions we are grateful to Jae-Sung Yi, Chang-Seok Lee and Young-Gyu Ko (Korea University, Seoul, South Korea). This work was supported in part by grants to SGC (2009-0078864 and 2009-0087099) and MGL (353-2009-2-C00071) from National Research Foundation of Korea.

Glossary

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- CIP

CDK-interacting protein

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- INK4

inhibitor of CDK

- KIP

kinase inhibitor protein

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA

short-interfering RNA

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- UIM

ubiquitin-interacting motif

- XAF1

XIAP-associated factor 1

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Author contributions

JH designed the study, performed the experiments and analyzed the data; YK, KWL, NGH, SIJ and JHL carried out molecular works; MJK and BKR analyzed human cancers; TKH performed statistical analyses; SY and JHB investigated brain development and designed a part of the study. SGC and MGL obtained funding, designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Edited by J-C Marine

Supplementary Material

References

- Li N, Sun H, Wu Q, Tao D, Zhang S, Ma Y. Cloning and expression analysis of a novel mouse zinc finger protein gene Znf313 abundantly expressed in testis. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;40:270–276. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2007.40.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini AL, Gao Y, Bijlmakers MJ. T-cell regulator RNF125/TRAC-1 belongs to a novel family of ubiquitin ligases with zinc fingers and a ubiquitin-binding domain. Biochem J. 2008;410:101–111. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YX, Zhang SZ, Hou YP, Huang XL, Wu QQ, Sun Y. Identification of a novel human zinc finger protein gene ZNF313. Sheng wu hua xue yu sheng wu wu li xue bao (Shanghai) 2003;35:230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlmakers MJ, Kanneganti SK, Barker JN, Trembath RC, Capon F. Functional analysis of the RNF114 psoriasis susceptibility gene implicates innate immune responses to double-stranded RNA in disease pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3129–3137. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner BJ, Scannell M, Prehn JHM. Identification of polyubiquitin binding proteins involved in NF-kappaB signaling using protein arrays. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:1010–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan G, Murty VV. Integrative genomic approaches in cervical cancer: implications for molecular pathogenesis. Future Oncol. 2010;6:1643–1652. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capon F, Bijlmakers M-J, Wolf N, Quaranta M, Huffmeier U, Allen M, et al. Identification of ZNF313/RNF114 as a novel psoriasis susceptibility gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1938–1945. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart PE, Nair RP, Ellinghaus E, Ding J, Tejasvi T, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies three psoriasis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1000–1004. doi: 10.1038/ng.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Hunter T. Degradation of activated protein kinases by ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:435–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.013008.092711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J, Pagano M. Deregulated degradation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and malignant transformation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Barbacid M. To cycle or not to cycle: a critical decision in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:222–231. doi: 10.1038/35106065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston P, Fong WG, Kelly NL, Toji S, Miyazaki T, Conte D, et al. Identification of XAF1 as an antagonist of XIAP anti-caspase activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:128–133. doi: 10.1038/35055027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun DS, Cho K, Ryu BK, Lee MG, Kang MJ, Kim HR, et al. Hypermethylation of XIAP-associated factor 1, a putative tumor suppressor gene from the 17p13.2 locus, in human gastric adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7068–7075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Huh JS, Chung SK, Lee JH, Byun DS, Ryu BK, et al. Promoter CpG hypermethylation and downregulation of XAF1 expression in human urogenital malignancies: implication for attenuated p53 response to apoptotic stresses. Oncogene. 2006;25:5807–5822. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SK, Lee MG, Ryu BK, Lee JH, Han J, Byun DS, et al. Frequent alteration of XAF1 in human colorectal cancers: implication for tumor cell resistance to apoptotic stresses. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2459–2477. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu SP, Sun YW, Cui JT, Zou B, Lin MCM, Gu Q, et al. Tumor suppressor XIAP-Associated factor 1 (XAF1) cooperates with tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand to suppress colon cancer growth and trigger tumor regression. Cancer. 2010;116:1252–1263. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micali OC, Cheung HH, Plenchette S, Hurley SL, Liston P, LaCasse EC, et al. Silencing of the XAF1 gene by promoter hypermethylation in cancer cells and reactivation to TRAIL-sensitization by IFN-β. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaman DW, Chawla-Sarkar M, Vyas K, Reheman M, Tamai K, Toji S, et al. Identification of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis-associated factor-1 as an interferon-stimulated gene that augments TRAIL Apo2L-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28504–28511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GH, Drullinger LF, Soulard A, Dulic V. Differential roles for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p16 in the mechanisms of senescence and differentiation in human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2109–2117. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CJ, Sedivy JM. Involvement of the INK4a/Arf gene locus in senescence. Aging Cell. 2003;2:145–150. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Igarashi M, Leung J, Sugrue MM, Lee SW, Aaronson SA. p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 induces permanent growth arrest with markers of replicative senescence in human tumor cells lacking functional p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:2789–2797. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell BB, Starborg M, Brookes S, Peters G. Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases induce features of replicative senescence in early passage human diploid fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 1998;8:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Tomita Y, Bilim V, Takeda M, Takahashi K, Kumanishi T. Abrogation of apoptosis induced by DNA-damaging agents in human bladder-cancer cell lines with p21/WAF1/CIP1 and/or p53 gene alterations. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:501–505. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961115)68:4<501::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman T, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. P21 is necessary for the p53-mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5187–5190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosar M, Bartkova J, Hubackova S, Hodny Z, Lukas J, Bartek J. Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci are dispensable for cellular senescence, occur in a cell type- and insult-dependent manner and follow expression of p16(ink4a) Cell Cycle. 2011;10:457–468. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.3.14707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Krizhanovsky V, Nunez S, Chicas A, Hearn SA, Myers MP, et al. A novel role for high-mobility group a proteins in cellular senescence and heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2006;126:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A, Hayakawa S, Yanai H, Stoiber D, Negishi H, Kikuchi H, et al. Integration of interferon-alpha/beta signalling to p53 responses in tumour suppression and antiviral defence. Nature. 2003;424:516–523. doi: 10.1038/nature01850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Fontela C, Macip S, Martinez-Sobrido L, Brown L, Ashour J, Garcia-Sastre A, et al. Transcriptional role of p53 in interferon-mediated antiviral immunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1929–1938. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou B, Chim CS, Pang R, Zeng H, Dai Y, Zhang RX, et al. XIAP-associated factor 1 (XAF1), a novel target of p53, enhances p53-mediated apoptosis via post-translational modification. Mol Carcinogen. 2012;51:422–432. doi: 10.1002/mc.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JG, Ammanamanchi S, Ko TC, Brattain MG. Transforming growth factor beta 1 increases the stability of p21/WAF1/CIP1 protein and inhibits CDK2 kinase activity in human colon carcinoma FET cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3340–3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck SE, Jung BH, Del Rosario E, Gomez J, Carethers JM. BMP-induced growth suppression in colon cancer cells is mediated by p21 (WAF1) stabilization and modulated by RAS/ERK. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1465–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan YM, Chen H, Qiao B, Liu ZW, Luo L, Wu YF, et al. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase decreases ubiquitination and promotes stabilization of p21 (WAF1/CIP1) in K562 cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas T, Dutta A. P21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–414. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roninson IB. Oncogenic functions of tumour suppressor p21 (Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1): association with cell senescence and tumour-promoting activities of stromal fibroblasts. Cancer Lett. 2002;179:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00847-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jascur T, Brickner H, Salles-Passador I, Barbier V, El Khissiin A, Smith B, et al. Regulation of p21 (WAF1/Cip1) stability by Wisp39, a Hsp90 binding TPR protein. Mol Cell. 2005;17:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Starostina NG, Kipreos ET. The CRL4 (Cdt2) ubiquitin ligase targets the degradation of p21(Cip1) to control replication licensing. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2507–2519. doi: 10.1101/gad.1703708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amador V, Ge S, Santamaría PG, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. APC/C (Cdc20) controls the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p21 in prometaphase. Mol Cell. 2007;27:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki T, Nishidate T, Park JH, Lin ML, Shimo A, Hirata K, et al. Involvement of elevated expression of multiple cell-cycle regulator, DTL/RAMP (denticleless/RA-regulated nuclear matrix associated protein), in the growth of breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2008;27:5672–5683. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui K, Arii S, Zhao C, Imoto I, Ueda M, Nagai H, et al. TFDP1, CUL4A, and CDC16 identified as targets for amplification at 13q34 in hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2002;35:1476–1484. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan BA, Dachrut S, Coral H, Yuen ST, Chu KM, Law S, et al. Integration of DNA copy number alterations and transcriptional expression analysis in human gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakura C, Hagiwara A, Yasuoka R, Fujita Y, Nakanishi M, Masuda K, et al. Amplification and over-expression of the AIB1 nuclear receptor co-activator gene in primary gastric cancers. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dekken H, Vissers K, Tilanus HW, Kuo WL, Tanke HJ, Rosenberg C, et al. Genomic array and expression analysis of frequent high-level amplifications in adenocarcinomas of the gastro-esophageal junction. Cancer Genet Cytogen. 2006;166:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Choi MH, Chang MS, Baik JH. Wnt5a-dopamine D2 receptor interactions regulate dopamine neuron development via extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15641–15651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.