Abstract

Indian society is collectivistic and promotes social cohesion and interdependence. The traditional Indian joint family, which follows the same principles of collectivism, has proved itself to be an excellent resource for the care of the mentally ill. However, the society is changing with one of the most significant alterations being the disintegration of the joint family and the rise of nuclear and extended family system. Although even in today's changed scenario, the family forms a resource for mental health that the country cannot neglect, yet utilization of family in management of mental disorders is minimal. Family focused psychotherapeutic interventions might be the right tool for greater involvement of families in management of their mentally ill and it may pave the path for a deeper community focused treatment in mental disorders. This paper elaborates the features of Indian family systems in the light of the Asian collectivistic culture that are pertinent in psychotherapy. Authors evaluate the scope and effectiveness of family focused psychotherapy for mental disorders in India, and debate the issues and concerns faced in the practice of family therapy in India.

Keywords: Indian family systems, collectivistic society, psychotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The term family is derived from the Latin word ‘familia’ denoting a household establishment and refers to a “group of individuals living together during important phases of their lifetime and bound to each other by biological and/or social and psychological relationship”.[1] The group also includes persons engaged in an ongoing socially sanctioned apparently sexual relationship, sufficiently precise and enduring to provide for the procreation and upbringing of children.[1] Unlike the western society, which puts impetus on “individualism”, the Indian society is “collectivistic” in that it promotes interdependence and co-operation, with the family forming the focal point of this social structure. The Indian and Asian families are therefore, far more involved in caring of its members, and also suffer greater illness burden than their western counterparts. Indian families are more intimate with the patient, and are capable of taking greater therapeutic participation than in the west.

In a situation where the mental health resource is a scarcity, families form a valuable support system, which could be helpful in management of various stressful situations. Yet, the resource is not adequately and appropriately utilized. Clinicians in India and the sub-continent do routinely take time to educate family members of a patient about the illness and the importance of medication, but apart from this information exchange, the utilization of family in treatment is minimal. Structured family oriented psychotherapy is not practiced in India at most places in India, except a few centers in South India. Research publications on family therapy from India are also few. Thereare some evidence from published “family intervention studies”, but whether all non-pharmacological interventions with family members can be considered as “family therapy” is a matter of theoretical debate.

Sholevar[2] defines family therapy as any use of a family-focused intervention to bring out behavioral and/or attitudinal changes in one or more family members” Although the “family” may be involved in many schools of psychotherapy, “family therapy” represents the most direct branch of psychotherapy that deals with the family system as a whole.

This paper discusses the features of Indian family systems in the light of the Asian collectivistic culture that are pertinent in psychotherapy and family therapy as used in India, and its further scope.

UNDERSTANDING THE INDIAN FAMILY FROM A PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC STANDPOINT

Role of culture and collectivism in shaping the family

Families do not exist in isolation and family dynamics are often best interpreted in the context of their societal and cultural background. Culture has been shown to determine the family structure by shaping the family type, size, and form[3,4] and the family functioning by delineating boundaries, rules for interaction, communication patterns, acceptable practices, discipline and hierarchy in the family.[4–6] The roles of family members are determined largely by cultural factors (as well as stages of the family life cycle),[4,7] and finally, culture also explains families’ ways of defining problems and solving them.[7]

Culture, however, is not an external passive influence on the families but families themselves serve as the primary agent for transferring these cultural values to their members.[8] Parents help children to learn, internalize, and develop understanding of culture through both covert and overt means.[9] Family members modify behaviors in themselves and others by principles of social learning. In this process, the general norms and beliefs may be modified to suit the needs of the family creating a set of “family values” – A subset of societal norms unique to the family.

It is imperative then, that therapists understand the impact of culture on family functioning as well as in conflict resolution and problem-solving skills of the family members.[10] One such important dimension of Asian and particularly Indian culture that affects family functioning is collectivism.[11–13] “Collectivism” refers to the philosophic, economic, or social outlook that emphasizes the interdependence amongst human beings. It is the basic cultural element for cohesion within social groups, which stresses on the priority of group goals over individual goals in contrast to “individualism”, which emphasizes on what makes the individual distinct, and promotes engagement in competitive tasks. “Horizontal collectivism” refers to the system of collective decision-making by relatively equal individuals, for example, by the intra-generational family member; while “vertical collectivism” refers to hierarchical structures of power in a collectivistic family, for example, inter-generational relations in a three generation family.

Classically, the cultures of Western Europe and North America with their complex, stratified societies, where independence and differences are emphasized, are said to be individualistic, whereas in Asia, Africa, parts of Europe and Latin America where agreeing on social norms is important and jobs are interdependent, collectivism is thought to be preponderant.[14,15] Studies comparing Caucasians or Americans with people from Asian cultures, such as Vietnamese or Filipino[13,16] do show that individualistic societies value self-reliance, independence, autonomy and personal achievement,[16] and a definition of self apart from the group.[13] On the other hand, collectivistic societies value family cohesion, cooperation, solidarity, and conformity.[16]

Such cultural differences mean that people in different cultures have fundamentally different constructs of the self and others. For more collectivistic societies like ours, the self is defined relative to others, is concerned with belongingness, dependency, empathy, and reciprocity, and is focused on small, selective in-groups at the expense of out-groups. Relationships with others are emphasized, while personal autonomy, space and privacy are considered secondary.[17] Application of western psychotherapy, primarily focused on dynamic models, ego structure and individuals, therefore, becomes difficult in the Indian collectivistic context. The point has been well discussed by Indian psychiatrists in the past. As early as in 1982, Varma expressed limitations to the applicability of the Western type of psychotherapy in India,[18] and cited dependence/interdependence (a marker of collectivism) in Indian patients with other family members as foremost of the seven difficulties in carrying out dynamic and individual oriented psychotherapy. Surya and Jayaram have also pointed out that the Indian patients are more dependent than their western counterparts.[19] Neki, while discussing the concepts of confidentiality and privacy in the Indian context opined that these terms do not even exist in Indian socio-cultural setting, as the privacy can isolate people in interdependent society.[20] Neki recommended a middle ground with family therapy or at least couple of sessions with the family members along with dyadic therapy in order to help the progress of the psychotherapy.[21] Family, therefore, forms an important focus for change in collectivistic societies, and understanding the Indian family becomes an essential prerequisite for involving them in therapy.

The traditional Indian family

Any generalizations about the Indian family suffer from oversimplification, given the pluralistic nature of the Indian culture. However, in most sociological studies, Asian and Indian families are considered classically as large, patriarchal, collectivistic, joint families, harboring three or more generations vertically and kith and kin horizontally. Such traditional families form the oldest social institution that has survived through ages and functions as a dominant influence in the life of its individual members. Indian joint families are considered to be strong, stable, close, resilient and enduring with focus on family integrity, family loyalty, and family unity at expense of individuality, freedom of choice, privacy and personal space.[22]

Structurally, the Indian joint family includes three to four living generations, including grandparents, parents, uncles, aunts, nieces and nephews, all living together in the same household, utilizing a common kitchen and often spending from a common purse, contributed by all. Change in such family structure is slow, and loss of family units after the demise of elderly parents is counterbalanced by new members entering the family as children, and new members (wives) entering by matrimonial alliances, and their offsprings. The daughters of the family would leave following marriage. Functionally, majority of joint families adhere to a patriarchal ideology, follow the patrilineal rule of descent, and are patrilocal; although matrilocal and matriarchal families are quite prevalent in some southern parts of the country. The lines of hierarchy and authority are clearly drawn, with each hierarchical strata functioning within the principal of “collective responsibility”. Rules of conduct are aimed at creating and maintaining family harmony and for greater readiness to cooperate with family members on decisions affecting almost all aspects of life, including career choice, mate selection, and marriage. While women are expected to accept a position subservient to males, and to subordinate their personal preferences to the needs of other, males are expected to accept responsibility for meeting the needs of others. The earning males are expected to support the old; take care of widows, never-married adults and the disabled; assist members during periods of unemployment and illness; and provide security to women and children.[1,23] Psychologically, family members feel an intense emotional interdependence, empathy, closeness, and loyalty to each other.

The changing Indian family

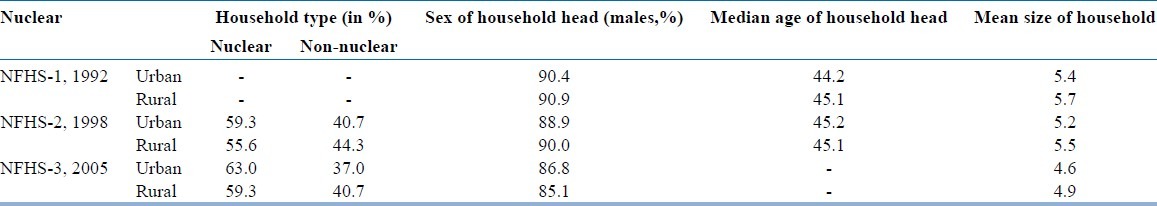

The socio-cultural milieu of India is undergoing change at a tremendous pace, leaving fundamental alterations in family structure in its wake. The last decade has not only witnessed rapid and chaotic changes in social, economic, political, religious and occupational spheres; but also saw familial changes in power distribution, marital norms and role of women. A review of the national census data and the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data suggests that, gradually, nuclear families are becoming the predominant form of Indian family institution, at least in urban areas. The 1991 census, for the first time reported household growth to be higher than the population growth, suggesting household fragmentation; a trend that gathered further momentum in the 2001 and the 2010 census. A comparison of the three NFHS data [Table 1] also shows that over the years there has been a progressive increase in nuclear families, more in urban areas, with an associated progressive decrease in the number of household members.[24–26] Other important trends include a decrease in age of the house-head, reflecting change in power structure and an increase in households headed by females, suggesting a change in traditional gender roles.

Table 1.

Summary data from the National Family Health Survey

However, though traditional joint families have been significantly replaced by urban “new order” nuclear families, it would be wrong to look at present Indian families in such simple bimodal groups. The family systems presently have become highly differentiated and heterogeneous social entities in terms of structure, pattern, role relationships, obligations and values. Joint families that stay under same roof, but with separate kitchen, separate purse and with considerable autonomy and reduced responsibility for extended family members are common and represent “transitional families”.[27] Others may stay in separate households but cluster around in the same community. Such transitional families though structurally nuclear, may still continue to function as joint families. Sethi, back in 1989 pointed out the strong networks of kinship ties in Indian “extended families”, and observed that even when relatives cannot actually live in close proximity, they typically maintain strong bonds and attempt to provide each other with economic help and emotional support.[1]

Effects of societal and familial change on mental health

Social and cultural changes have altered entire lifestyles, interpersonal relationship patterns, power structures and familial relationship arrangements in current times. These changes, which include a shift from joint/extended to nuclear family, along with problems of urbanization, changes of role, status and power with increased employment of women, migratory movements among the younger generation, and loss of the experience advantage of elderly members in the family, have increased the stress and pressure on such families, leading to an increased vulnerability to emotional problems and disorders. The families are frequently subject to these pressures.

Countries within the developing world are impatient and intend to achieve within a generation, what countries in the developed world took centuries. Hence societal changes here are not step by step or gradual, but rapid, the process inevitably involving “temporal compression”. Additionally, the sequences of these societal changes are haphazard or “Cacophonic”,[28] producing a condition that is highly unsettling and stressful. For example, in a household where a woman is the chief breadwinner but has minimal standing in decision making, the situation leads to role resentment and disorganized power structure in the family. Indeed, studies do show that nuclear family structure is more prone to mental disorders than joint families.[29] Fewer patients with mental illness from rural families have been reported to be hospitalized when compared to urban families because of the existing joint family structure, which apparently provides additional support.[30] Children from large families have been found to report significantly lower behavioral problems like eating and sleeping disorders, aggressiveness, dissocial behavior and delinquency than those from nuclear families.[31] Even the large scale international collaborative studies conducted by WHO – the International Pilot Study on Schizophrenia, the Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders and the International Study of Schizophrenia – reported that persons with schizophrenia did better in India and other developing countries, when compared to their Western counterparts largely due to the increased family support and integration they received in the developing world.[32]

Although a bulk of Indian studies indicates that the traditional family is a better source for psychological support and is more resilient to stress, one should not, however, universalize. The “unchanging, nurturant and benevolent” family core is often a sentimentalization of an altruistic society.[33] In reality, arrangements in large traditional families are frequently unjust in its distribution of income and allocation of resources to different members. Exploitation of family resources by a coterie of members close to the “Karta” (the head of family) and subjugation of women are the common malaise of traditional Indian family. Indian ethos of maintaining “family harmony” and absolute “obedience to elderly” are often used to suppress the younger members. The resentment, however, passive and silent it may be, simmers, and in the absence of harmonious resolution often manifests as psychiatric disorders. Somatoform and dissociative disorders, which show a definite increased prevalence in our society compared to the west, may be viewed as manifestations of such unexpressed stress.

Therefore, rather than lamenting on the change in societal structure and loss of the joint family, the therapist should be aware of the unique dynamics of each family he treats, and should endeavor to find and utilize the strengths therein, while providing ways to cope with stress within the limits of the available resources.

UNDERSTANDING PSYCHOTHERAPY FROM THE FAMILY PERSPECTIVE

Family oriented psychotherapy: History and scope in India

Social interventions with families to help them cope with problems have always been a part of all cultures in form of a variety of rituals, for example, the rituals surrounding death of family members. The roots of the formal development of family therapy, however, dates back to the early 1940s, when pioneers like John Bowlby in the United States; John Elderkin Bell, Nathan Ackerman, Theodore Lidz, Lyman Wynne, Murray Bowen and Carl Whitaker in United Kingdom; and D.L.P. Liebermann in Hungary began seeing and observing family members in therapy sessions.[34] The initial strong influence from psychoanalysis soon gave way to concepts from social psychiatry, learning theory and behavior therapy, and the early concepts of theoretical framework for family therapy were formed.[2] In the mid-1950s, Gregory Bateson and colleagues at Palo Alto in the United States, introduced ideas from cybernetics and general systems theory in psychotherapy.[35] The systems approach did not focus on the linear causation model of individual psychology, and instead emphasized on feedback and homeostatic mechanisms that operate in family systems. The famous “circular causation and process” model was forwarded and here-and-now interactions between family members started being viewed as a major factor in maintaining or exacerbating problems, whatever be the original cause.[36] Simultaneously, Murray Bowen at the National Institute of Mental Health, worked on his hypothesis on family systems, based on his observations on the father-mother-child triad. Bowen's observations on triadic relationship, fusion and distancing, nuclear family emotional process, multi-generational transmission processes and family constellation forms the basis of the family systems theory, which later came to be known as the Bowen's theory.

By the mid-1960s, a large number of distinct schools of family therapy had emerged, some of which included brief therapy, strategic therapy, structural family therapy, and the Milan systems model. Concurrently and somewhat interdependently with the systems theory, intergenerational therapies emerged, which theorized the intergenerational transmission of health and dysfunction and usually dealt with at least three generations of a family. After the late-1970s, the field of family therapy saw many practical modifications of the earlier rigid theoretical frameworks, especially in the light of accumulated clinical experience in treatment of serious mental disorders. In the past few decades, there has been a general move towards integration and eclecticism, with practitioners using techniques from several areas, depending upon their own inclinations and/or the needs of the clients.

In India, work in family therapy started in the late 1950s, coinciding with the period of increased interest in psychotherapy in India. Vidya Sagar, who worked with families at the Amritsar Mental Hospital in the 1950s, is credited as the father of family therapy in India. His own writings on the topic are sparse, but he was able to involve families of patients in understanding and taking care of their patients with psychiatric illness, and to support each other through group participation.[37] Vidya Sagar found that involving the family significantly reduced the hospital stay, increased acceptance of the patient by the family, and enhanced family coping skills.[38] In a similar attempt about the same time, the Mental Health Center at Vellore[39] started admitting all psychiatric patients along with their families to unit family rooms. Mental Health Center, Vellore tried to focus on family education and family counseling on how to deal with the index patient and showed promising results of the family interventions. 1960s was also the time of beginning of the general hospital psychiatric units (GHPUs) with inpatient facilities, where patients were admitted mandatorily with a family member with focus on family education and counseling. The similar practice has been followed at all the GHPUs, which have been established in India over the last 5 decades. These units, though may not be conducing family therapy, are working with family involvement in treatment of the persons with mental illness.

Another major boost to family therapy in India occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro-Sciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore started working actively on family members of patients with psychiatric disorders, which ultimately resulted in the formation of a formal Family Psychiatry Center in 1977. Early work from the center showed that families could be taught to cope with their burden through education, counseling and group support in an effective manner.[40] Subsequent work by researchers[41–43] showed the usefulness of involving families in the management of a variety of psychiatric disorders including marital discord, hysteria and psychosis. In the late 1980s, the center developed Indian tools for working in the field of family therapy, notable amongst which are the Family Interaction Pattern Scale, the Family Topology Scale[44,45] and the Marital Quality Scale.[46] In the late 1980s and 1990s the center started training post graduates in psychiatry in concepts and schools of family therapy and started orienting itself to structured rather than generic family therapy. At the turn of this century, it became the only center in India to offer formal training and diploma course in family therapy.[47] Though the center in past had practiced various dynamic and behavioral models, currently it follows primarily a systemic model of family therapy.[48]

In the non-government sector, though there are family therapy practitioners, particularly in the cities of Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore, they are mostly scattered and often suffer from the lack of training and resource facilities. The Schizophrenia Research Foundation at Chennai, which works with long-term care and rehabilitation of the chronically mentally ill patients, conducts a family intervention program, focused on education and coping of family members with the illness of the index patient. The Indian Association for Family Therapy, founded since 1991, has also been working in the field to provide a platform for private therapists.

Effectiveness of family oriented psychotherapy in India

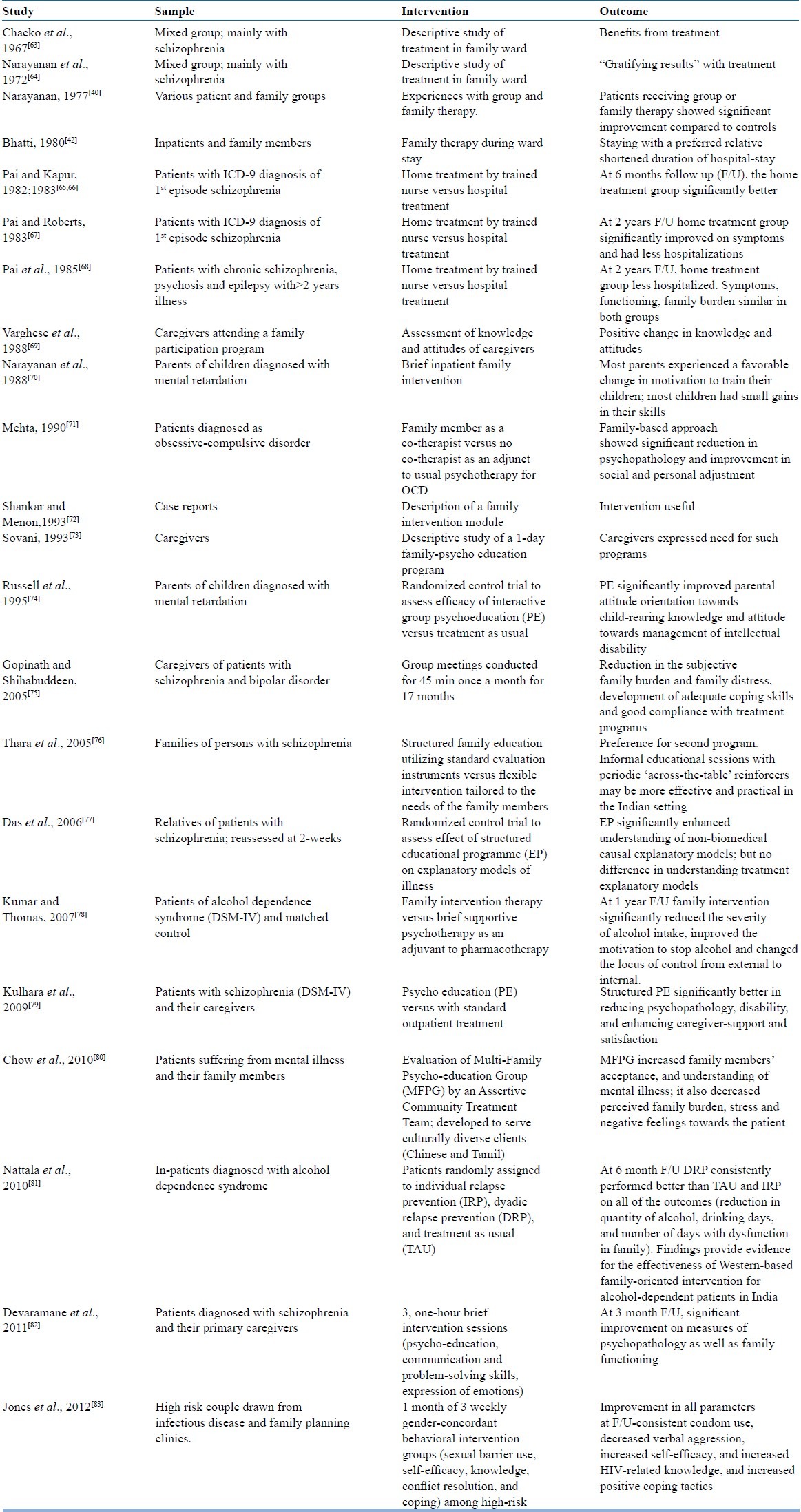

Although a significant number of therapists practice family therapy in India in government and private settings, the published literature on the subject is surprisingly sparse. Most publications are issue based experiential accounts of the practitioners, rather than evidence based merits of particular therapy modalities. Even then, most intervention studies report significant benefits whenever family have been involved in management of psychiatric disorders. Table 2 summarizes the findings of major family intervention studies from India.

Table 2.

Summary of the findings of family intervention studies from India

A large body of published work in family therapy in India comes from the Family Therapy Center, at NIMHANS.[49] In one of the earliest studies from the center, it was found that staying with a preferred family member reduced duration of hospital stay in psychiatric inpatients.[42] In another definitive study on the effectiveness of family therapy in Indian setting, Prabhu et al. in 1988 followed-up 60 families over 2 years, who had received brief integrative inpatient family therapy. Two third of the group did very well or moderately well.[50] Later studies have reported improvement with family therapy in patients with a wide range of psychiatric problems, including schizophrenia,[51] alcohol dependence,[52] eating disorders,[53] epileptic psychosis,[54] adolescent conduct disorder,[55] marital problems,[56–59] family violence[60,61] and in families coping with people living with HIV AIDS.[62]

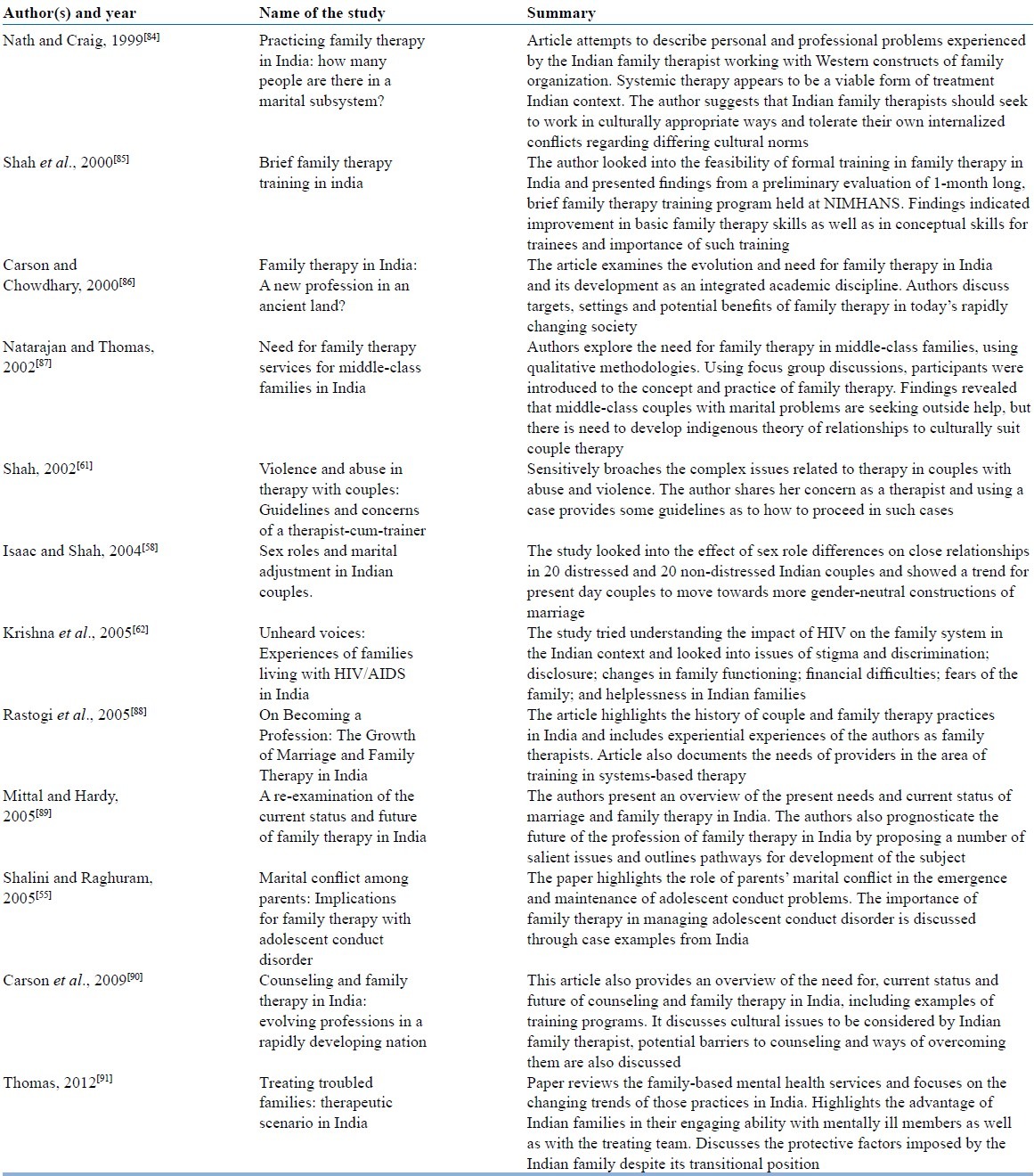

In addition to the interventional studies, experiential accounts and reflective writings by therapists working with families in India help us to understand issues, practical difficulties and unique advantages of the Indian setting. Table 3 summarizes the major points of various published studies on family therapy by Indian practitioners in last 15 years, that throw light on the process issues rather than the outcome.

Table 3.

Summary of experiential and reflective journal articles on family therapy in India

Family oriented psychotherapy: Process and issues in practice

Ideally, any psychotherapy would include intake process, therapy proper and a termination phase. In family therapy, aim of the intake phase is to understand the families’ perception of the problem, their motivation to undergo therapy, and the therapist's assessment of the suitability and type of family therapy to be applied. Assessment of the family forms an important part of the intake phase and different therapists employ different techniques for the purpose like the three generation genogram; life cycle chart, structural map or the circular hypothesis. The three generation genogram diagrammatically lists out the patient's generation and two more related generations and helps to understand trans-generational patterns of interaction. The life cycle chart explores the functions of the family and roles of different family members. A structural map shows the different subsystems in the family, the power structure and the relations between the family members. This can show if relations are normal, overinvolved, conflictual or distant. The circular hypothesis generally used in systemic therapy helps to understand the meaning of the symptoms for the patient and the role of the family members in maintaining them.

As most of these assessment tools were originally developed in the west, they need to be suitably modified for use in the eastern culture. In the last few decades attempts have been to develop culturally sensitive tools to assess Indian family in treatment. The Family Topology Scale[52] is a 28 item scale that measures family types, and groups them into the five subtypes of normal, cohesive, egoistic, altruistic and anoxic. Another tool, the Family Interaction Pattern scale,[44] looks into the developmental phases of the family. The scale has six subscales looking into leadership, communication, role, reinforcement, cohesiveness and social support. For assessing marital problems in Indian couples two tools are available: Marital Adjustment Questionnaire[92] and Marital Quality Scale.[46] Marital Adjustment Questionnaire[92] attempts to assess marital adjustment in Indian couples, and measures seven aspects of family functioning, including personality, emotional factors, sexual satisfaction, marital role and responsibility, relationship to in laws, attitudes to children and family planning, and interpersonal relationships. Marital Quality Scale[46] is a more comprehensive instrument for assessing marital problems and looks into 12 dimensions of understanding, rejection, satisfaction, affection, despair, decision making, discontent, dissolution potential, dominance, disclosure, trust and role functioning. Such emic assessment tools are invaluable in understanding the unique problems of the family in our culture.

The therapy proper is the phase, where major work on the family is carried out. The school of therapy used depends on various factors. For example, the degree of psychological sophistication in the family will determine if psychodynamic techniques can be used. The nature of the disorder will also determine the therapy, like the use of behavioral techniques in chronic psychotic illness. Therapist's comfort and training, and the time the family can spare for therapy are other determining factors. Dynamic approaches generally take months to years, where as focused strategic techniques can bring benefits over a few sessions.

Endo-cultural issues may crop up at the initial phases, which threaten to jeopardize the therapy outcome. The therapist needs to be aware of them and be sensitive and considerate. Although Indian families are more encouraging and supporting of their mentally ill member, the rigid hierarchical structure of Indian families often hinders free communication of thoughts and feelings. Therefore, the therapist may encounter difficulties in improving family communication pattern. The “karta” (head) of the family may resist attempts of family members to usurp his authority and so may not allow other family members to express feelings. The therapist may come to an impasse, if he attempts to challenge the authority of the father or sides with the wife rather than with the husband in couple's therapy. Additionally, given the diverse cultural and social background, the therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individual family, keeping factors such as socio-economic status, educational level and family structure (nuclear, transitional, joint, traditional) into account. Directive approaches may be more suitable for traditional families, as the therapist is often looked upon as charismatic, authoritarian and in control of the session.[93]

New and unexpected problems arising out of the rapid changing social scenario also need to be addressed. Family and couple's conflict arising out of factors such as conflicts in families over dowry, or related to inter-caste marriage; sexual problems arising out of physical separation of couples due to job timing or placement; disagreement about child rearing practices (both within couples and intergenerational); conflicts related to husband's role in sharing in domestic chores for working couples; problems with unsupervised children, and loss or displacement of role or function of the elderly are only a few of the problems unique to modern Indian families.[90] In family therapy focusing on adolescent and children, substance abuse, juvenile delinquency, school dropout or low school attendance are common amongst the lower socioeconomic classes. Parent-child conflict from increased autonomy and individuation of the child are common in nuclear families. In recent times, increased demands on children or adolescents for academic achievements from parents, the culture clash with children going for night-outs, parties, raves and adolescent sexual experimentation have been reported by Indian therapists as common issues while dealing with adolescents.[86] Although most of these problems are the same that troubled the west in the 1960s and the 1970s, our cultural differences make the therapist look and treat these problems as new.

It might be beneficial for the therapist to understand that in India and other similar collectivistic societies, the concepts of self, attitudes, values and boundaries are defined differently from those of the western world. In collectivistic societies the self is largely defined through the collective identity with family identity forming a significant component of the self-identity.[94] Therefore, individuals from such societies, when they stand up for their individual rights are termed rebellious, disobedient, or disrespectful. In therapy, if the person resists the solutions proposed by family members, the person may often be accused of not respecting important members of the family and/or community.[15] Attitudinal differences in collectivistic societies hamper treatment seeking too. People from collectivist societies often tend to keep their personal problems to themselves, especially if their own opinions and experiences are inconsistent with the conventional wisdom and mores of the family. Typically, only in severe cases, the people seek support from outsiders, and even then at the cost of significant resistance from other family members, who may perceive help seeking from the therapist as a measure of failure of the family to solve the problem of their member.[95] Additionally, involvement of outside strangers in resolving personal problems may be perceived by members of the collective society as intruding in the family's private affairs, undermining the family's harmony, and/or as a potential threat to their reputation. Collectivist values make each member of the family responsible for the behavior and the life conditions of every other family member, even to the extent of denial of individual needs and aspirations. In therapy, this often leads to over involvement, lack of privacy and space for the client. Indeed, negative expressed emotions that might hamper therapy and positive expressed emotions that help, have both been found to be more significant predictors of outcome in our country compared to the west.[96]

Finally, the therapist should be aware of the psychotherapeutic concepts derived from Indian philosophy and religion, as they have been found to be effective and culturally more acceptable in certain cases. The concept of “Shivite” stemming from the Hindu mythology of God Shiva and representing a phallic symbol can be used in dynamic psychotherapy.[97] The legend of Savitri has been used as a framework for psychotherapy by Surya and Jayaram.[98] Wig has used the term Hanuman complex[99] for the mythological story of Lord Hanuman needing external help being reminded about his forgotten powers. The concept can be used to help patients understand the process of psychotherapy and identifying one's hidden strengths. Varma used principles from the communication of Buddha in psychotherapy, which he viewed as an ‘interpersonal method of mitigating suffering’. He has also emphasized on the use of concepts of Karma and Dharma in psychotherapy.[18] Neki used the concept of “Sahaja” and the role of “nirvana” in psychotherapy. He also propounded on the directive interaction between the therapist and the patient using the “Guru-Chela” paradigm.[100] Although such concepts may not be universally applicable, particularly in the changed urban modern scenario, they can be effectively used particularly in traditional systems to make therapy more acceptable and effective.

The termination phase summarizes the original problem, reviews the beneficial changes and patterns of interaction that have emerged through therapy, and stresses on the need for sustaining the improvements achieved. The follow-up sessions may be continued over the next 6 months to a year to ensure that the client therapist bond is not severed too quickly.

CONCLUSION

Indian families are capable of fulfilling the physical, spiritual and emotional needs of its members; initiate and maintain growth, and be a source of support, security and encouragement to the patient. These fundamental characteristics of the Indian family remain valid even now despite the changes in the social scenario. In a country, where the deficit in mental health professionals amounts to greater than 90% in most parts of the country, the family is an invaluable resource in mental health treatment. From a psycho-therapeutic viewpoint, in collectivistic societies like ours, the family may be a source of the trouble as well as a support during trouble. It is therefore, plausible that the family might also provide solutions of the trouble and indeed, interventions focusing on the whole family rather that the individual often results in more gratifying and lasting outcome. Sadly, the progress made in the last few decades has been minimal and restricted to few centers only and family therapy has not found popularity amongst the mental health community. Lack of integration of psychotherapy in postgraduate curriculum, lack of training centers for clinical psychologists, and lack of a good model of family therapy that can be followed in the diverse Indian setting are the three cardinal reasons for the apathy. This does not absolve the mental health professionals from the responsibility of providing solutions for the problems of the family, which seems to have multiplied during the same time. The Indian family, which often feels bewildered in these times of changed values, changed roles, changed morality and changed expectations is in need of support and is ready for family therapy. If developed enthusiastically, family therapy might be the right tool to not only help the families in need but also to develop a huge resource in community-centered treatment of mental-health problems.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Sethi BB. Family as a potent therapeutic force. Indian J Psychiatry. 1989;31:22–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sholevar PG. Introduction: Family theory and therapy. In: Sholevar PG, Schwoeri L D, editors. Textbook of Family and Couples Therapy: Clinical Applications. Rockville, MD: Aspen; 2003. pp. 3–25. Part 1; Chap 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGill D. Cultural concepts for family therapy. In: Hansen J, Falicov C, editors. Cultural Perspectives in Family Therapy: The Family Therapy Collections. Rockville MD: Aspen; 1983. pp. 108–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce J, editors. Ethnicity and Family Therapy. 2nd ed. The Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falicov C, Brudner-White L. Shifting the family triangle: The issue of cultural and contextual relativity. In: Hansen J, Falicov C, editors. Cultural Perspectives in Family Therapy: The Family Therapy Collections. Rockville MD: Aspen; 1983. pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGill DW. The cultural story in multicultural family therapy. Fam Soc. 1992;73:339–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartzman J. Family ethnography: A tool for clinicians. In: Hansen J, Falicov C, editors. Cultural Perspectives in Family Therapy: The Family Therapy Collections. Rockville MD: Aspen; 1983. pp. 122–35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson AC. Resiliency mechanisms in culturally diverse families. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families. 1995;3:316–324. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preli R, Bernard JM. Making multiculturalism relevant for majority culture graduate students. J Mar Fam Ther. 1993;19:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas AJ. Understanding culture and worldview in family systems: Use of the multicultural genogram. Fam J: Couns Ther Couples Fam. 1998;6:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avasthi A. Indianizing psychiatry: Is there a case enough? Indian J Psychiatry. 2011;53:111–20. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avasthi A. Preserve and strengthen family to promote mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:113–26. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai J. Intergenerational conflict within Asian American families: The role of acculturation, ethnic identity, individualism, and collectivism. Diss Abstr Int. 2007;67:7369. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson K, Fivush R. The emergence of autobiographical memory: A social cultural developmental theory. Psychol Rev. 2004;111:486–511. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triandis HC. Collectivism and individualism as cultural syndromes. Cross Cult Res. 1993;27:155–80. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skillman G. Intergenerational conflict within the family context: A comparative analysis of collectivism and individualism within Vietnamese, filipino, and caucasian families. Diss Abstr Int. 2000;60:4910. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markus H, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224–53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varma VK. Present state of psychotherapy in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:209–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surya N, Jayaram S. Some basic considerations in the practice of psychotherapy in the Indian setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 1964;6:153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neki JS. Confidentiality, secrecy, and privacy in psychotherapy: Sociodynamic considerations. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:171–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manickam LS. Psychotherapy in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S366–70. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullatti L. Families in India: Beliefs and realities. J Comp Fam Stud. 1995;26:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chekki D. Family values and family change. Indian J Soc Work. 1996;69:338–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhat PN, Arnold F, Gupta K, Kishor S, Parasuraman S, Arokiasamy, Singh SK, Lhungdim H. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. I. Mumbai India: National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India 2005–06; 2007. Household Population and Housing Characteristics; pp. 21–52. Chap 2. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India 1998-99. India Mumbai: 2000. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-1), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India 1992-93. India Mumbai: 1995. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinha D. Some recent changes in Indian family and their impications for socialization. Indian J Soc Work. 1984;45:271–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myrdal G. Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations. Allen Lane: The Penguin Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sethi B, Chaturvedi P. A review and role of family studies and mental health. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 1985;1:216–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandrashekhar C, Rao N, Murthy R. The chronic mentally ill and their families. In: Bharat S, editor. Research on Families with Problems in India: Issues and Implications. Mumbai: Tata Institute of Social Sciences; 1991. pp. 113–20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murlidharan R. Size of family and its relationship with behavior difficulties in children. J Psychol Res. 1969;13:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulhara P, Chakrabarti S. Culture and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2001;24:449–64. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennett L. The Role of Women in Income Production and Intrahousehold Allocation of Resources as a Determinant of Child Health and Nutrition. Geneva: WHO/UNICEF; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broderick C, Schrader S. The history of professional marriage and family therapy. In: Gurman A, Kniskern D, editors. Handbook of Family Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guttman H. Systems theory, cybernetics, and epistemology. In: Gurman A, Kniskern D, editors. Handbook of Family Therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becvar D, Becvar R. Family Therapy: A Systemic Integration. 7th ed. Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vidyasagar . Innovations in Psychiatric Treatment at Amritsar Mental Hospital. New Delhi: WHO. SEA/Ment; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatti R, Varghese M. Family Therapy in India. Indian Soc Psychiatry. 1995;11:30–4. doi: 10.1177/002076409504100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verghese A. Involvement of families in mental health care. J Christ Med Assoc India. 1971;46:247. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narayanan HS. Experiences with group and family therapy in India. Int J Group Psychother. 1977;27:517–9. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1977.11491333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatti R, Channabasavanna S. Social system approach to understand family disharmony. Indian J Soc Work. 1979;40:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhatti RS, Janakiramaiah N, Channabasavanna SM. Family psychiatric ward treatment in India. Fam Process. 1980;19:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1980.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geetha PR, Channabasavanna SM, Bhatti RS. The study of efficacy of family ward treatment in hysteria in comparison with the open ward and the outpatient treatment. Indian J Psychiatry. 1980;22:317–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatti RS, Subba Krishna DK, Ageira BL. Validation of family interaction patterns scale. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:211–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhatti R, Channabasavanna SM, Prabhu L, Subha Krishna D, Shivaji R. A manual on family typology scale. Bangalore: Eastern Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah A. Assessment of Marital Life. 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varghese M, Bhatti R, Raghuram A, Chandra P, Uday Kumar G, Shah A. Training in Family Therapy at NIMHANS. In: Kapur M, Shama Sundar C, Bhatti R, editors. Psychotherapy Training in India. Bangalore: NIMHANS; 2001. pp. 112–5. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verghese M, Uday Kumar G. An integrative systemic model of family therapy at NIMHANS. In: Bhatti R, Verghese M, Raghuram A, editors. Changing Marital and Family Systems, Challenges to Conventional Model in Mental Health. Bangalore: NIMHANS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences. NIMHANS: Family Psychiatry Centre: Publications [Internet] 2012. [Last cited 2012 Dec 14]. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/fpc/publication.htm .

- 50.Prabhu LR, Desai NG, Raghuram A, Channabasavanna SM. Outcome of family therapy: Two year follow-up. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1988;34:112–7. doi: 10.1177/002076408803400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chandra P, Varghese M, Anantharaman Z, Channabasavanna S. Family therapy in poor outcome schizophrenia and the need to look beyond psychoeducation. Fam Ther. 1994;21:47. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Channabasavanna S, Bhatti R. Family therapy of alcohol addicts. In: Ramachandran V, Palaniappan V, Shaw L, editors. Continuing Medical Education Programme. Madras: Indian Psychiatric Society; 1982. pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chandra PS, Shah A, Shenoy J, Kumar U, Varghese M, Bhatti RS, et al. Family pathology and anorexia in the Indian context. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1995;41:292–8. doi: 10.1177/002076409504100407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swamy HS, Mallikarjunaiah M, Bhatti RS, Kaliaperumal VG. A study of epileptic psychoses-150 cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:231–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anant S, Raguram A. Marital conflict among parents: Implications for family therapy with adolescent conduct disorder. Contemp Fam Ther. 2005;27:473–82. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhatti R, Sobhana H. A model for enhancing marital and family relationships. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;16:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Channabasavanna S, Bhatti R. Utility of “Role Expectation Model” in treatment of marital problems. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 1985;2:105–20. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Isaac R, Shah A. Sex roles and marital adjustment in Indian couples. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50:129–41. doi: 10.1177/0020764004040960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah A, Gaur S, Gaonkar M, Raguram A. Relationship attributions and marital quality in women with depression. Eastern J Psychiatry. 2003;7:62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhatti R, Beig A. Family violence: A systemic model. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 1985;1:174–85. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shah A. Violence and abuse in therapy with couples: Guidelines and concerns of a therapist-cum-trainer. Eastern J Psychiatry. 2002;6:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krishna VA, Bhatti RS, Chandra PS, Juvva S. Unheard voices: Experiences of families living with HIV/AIDS in India*. Contemp Fam Ther. 2005;27:483–506. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chacko R. Family participation in the treatment and rehabilitation of the mentally ill. Indian J Psychiatry. 1967;9:328–33. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Narayanan H, Embar P. Review of treatment in a family ward. Indian J Psychiatry. 1972;14:123–6. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pai S, Kapur RL. Impact of treatment intervention on the relationship between dimensions of clinical psychopathology, social dysfunction and burden on the family of psychiatric patients. Psychol Med. 1982;12:651–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700055756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pai S, Kapur RL. Evaluation of home care treatment for schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:80–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb06726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pai S, Roberts EJ. Follow-up study of schizophrenic patients initially treated with home care. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:447–50. doi: 10.1192/bjp.143.5.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pai S, Channabasavanna SM, Nagarajaiah, Raghuram R. Home care for chronic mental illness in Bangalore: An experiment in the prevention of repeated hospitalization. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:175–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verghese A. Family participation in mental health care: The vellore experiment. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:117–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Narayanan HS, Girimaji SR, Gandhi DH, Raju KM, Rao PM, Nardev G. Brief in-patient family intervention in mental retardation. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:275–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mehta M. A comparative study of family-based and patient-based behavioral management in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:133–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shankar R, Menon M. Development of a framework of interventions with families in the management of schizophrenia. Psychosoc Rehabil. 1993;16:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sovani A. Understanding schizophrenia: A family psychoeducational approach. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:97–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russell PS, al John JK, Lakshmanan JL. Family intervention for intellectually disabled children. Randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:254–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shihabuddeen TM, Gopinath PS. Group meetings of caretakers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:153–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.55939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thara R, Padmavati R, Lakshmi A, Karpagavalli P. Family education in schizophrenia: A comparison of two approaches. Indian J Psychiatry. 2005;47:218–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.43056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Das S, Saravanan B, Karunakaran KP, Manoranjitham S, Ezhilarasu P, Jacob KS. Effect of a structured educational intervention on explanatory models of relatives of patients with schizophrenia: Randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:286–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suresh Kumar PN, Thomas B. Family intervention therapy in alcohol dependence syndrome: One-year follow-up study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:200–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kulhara P, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A, Sharma A, Sharma S. Psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of Indian patients with schizophrenia: A randomized-controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:472–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chow W, Law S, Andermann L, Yang J, Leszcz M, Wong J, et al. Multi-family psycho-education group for assertive community treatment clients and families of culturally diverse background: A pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:364–71. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9305-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nattala P, Leung KS, Nagarajaiah, Murthy P. Family member involvement in relapse prevention improves alcohol dependence outcomes: A prospective study at an addiction treatment facility in India. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:581–7. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Devaramane V, Pai NB, Vella SL. The effect of a brief family intervention on primary carer's functioning and their schizophrenic relatives levels of psychopathology in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2011;4:183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones D, Bagga R, Nehra R, Deepika, Sethi S, Walia K, et al. Reducing Sexual Risk Behavior Among High-Risk Couples in Northern India. [Last Accessed on 2012 Dec 1];Int J Behav Med. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9235-4. Pub Online on May 12, 2012, Available at: http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs12529-012-9235-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nath R, Craig J. Practising family therapy in India: How many people are there in a marital subsystem? J Fam Ther. 1999;21:390–406. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shah A, Varghese M, Udaya Kumar GS, Bhatti RS, Raguram A, Sobhana H, et al. Brief family therapy training in India. J Fam Psychotherapy. 2000;11:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carson DK, Chowdhury A. family therapy in India: A new profession in an ancient land? Contemp Fam Ther. 2000;22:387–406. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Natrajan R, Thomas V. Need for family therapy services for middle-class families in India. Contemp Fam Ther. 2002;24:483–503. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rastogi M, Natrajan R, Thomas V. On becoming a profession: The growth of marriage and family therapy in India*. Contemp Fam Ther. 2005;27:453–71. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mittal M, Hardy KV. A re-examination of the current status and future of family therapy in India. Contemp Fam Ther. 2005;27:285–300. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carson DK, Jain S, Ramirez S. Counseling and family therapy in India: Evolving professions in a rapidly developing nation. Int J Adv Counselling. 2009;31:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thomas B. Treating troubled families: Therapeutic scenario in India. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24:91–8. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.656302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kumar P, Rohtagi K. Development of the marriage adjustment questionnaire. Indian J Psychol. 1976;51:346–58. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prabhu R. Global Perspectives in Family Therapy: Development, Practice, Trends. In: Ng Kit S., editor. Beginning of family therapy in India. New York: Brunner-routledge; 2003. pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bochner S. Cross-Cultural Differences in the self concept a test of Hofstede's individualism/collectivism distinction. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1994;25:273–83. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Haj-Yahia MM, Sadan E. Issues in intervention with battered women in collectivist societies. J Marital Fam Ther. 2008;34:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2008.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Leff J, Wig NN, Bedi H, Menon DK, Kuipers L, Korten A, et al. Relatives’ expressed emotion and the course of schizophrenia in Chandigarh. A two-year follow-up of a first-contact sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:351–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.156.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nand S. A comparative study of scientific and religious psychotherapy with a special study of the role of the commonest shivite symbolic model in total psychoanalysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1961;3:261–173. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Surya NC, Jayaram SS. Some basic considerations in the practice of psychotherapy in the Indian setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 1996;38:10–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wig NN. Hanuman complex and its resolution: An illustration of psychotherapy from Indian mythology. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:25–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neki JS. Psychotherapy in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:1–10. [Google Scholar]