Abstract

The Bhagavad Gita is based on a discourse between Lord Krishna and Arjuna at the inception of the Kurukshetra war and elucidates many psychotherapeutic principles. In this article, we discuss some of the parallels between the Gita and contemporary psychotherapies. We initially discuss similarities between psychodynamic theories of drives and psychic structures, and the concept of three gunas. Arjuna under duress exhibits elements of distorted thinking. Lord Krishna helps remedy this through a process akin to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). We ascertain the analogies between the principles of Gita and CBT, grief emancipation, role transition, self-esteem, and motivation enhancement, as well as interpersonal and supportive psychotherapies. We advocate the pragmatic application of age old wisdom of the Gita to enhance the efficacy of psychotherapeutic interventions for patients from Indian subcontinent and to add value to the art of western psychotherapies.

Keywords: Bhagavad Gita, grief emancipation therapy, mindfulness, psychotherapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, supportive psychotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The value of spirituality in healing is a time-honored concept. There has been a recent surge in interest in the eastern philosophies for mental health care. For instance, successful amalgamation of Zen's principles with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in the form of dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT),[1] as well as the psychotherapeutic application of mindfulness is on the rise. In most cultures for centuries, different formats of directive or non-directive talk therapies for treatment of mental-health problems have been utilized. A variety of brief and culturally relevant models of psychotherapy have been in use since time immemorial. Although psychotherapy as a medical discipline gained greater acceptance following Freudian studies on psychodynamic underpinnings. One of the most renowned discourses in Hindu philosophy and psychotherapy comes from the Bhagavad Gita.

The timeless teachings of the Bhagavad Gita are deeply embedded in the Hindu psyche and continue to serve as a spiritual guide to the vast majority of Hindus around the globe. This scripture consists of 18 chapters and 701 verses (shlokas) authored by Vyasa and dates back to 2500 to 5000 years BC. The Gita represents chapters 25-42 of the Mahabharata, which has 100,000 shlokas.

The storyline in the Mahabharatha is based on the conflict between two groups of cousins, the diabolical Kauravas and the virtuous Pandavas. The Pandavas and their supporters, with the aid of Lord Krishna (whom the Hindus believe to be an incarnation of Lord Vishnu), vanquish the Kauravas confederation during the 18-day war fought on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. The Gita is a prelude to the Kurukshetra war; the context involves the accomplished and astute archer Arjuna on a chariot navigated by Lord Krishna (the guide and the charioteer), getting ready to face the large army of enemies consisting of his relatives, teachers and mentors. Though a mighty warrior, Arjuna is unwilling as he fears annihilation of his kin's and mentors. As a result of guilt, doubt and attachment to his loved ones, Arjuna contemplates withdrawing from the battlefield. The Gita is a discourse by Lord Krishna, guiding his disciple Arjuna to the right course of action to help him fulfill his destiny in the war, a triumph of righteousness over evil. This interaction between Lord Krishna and Arjuna encompass many psychotherapeutic principles.

The Hindus believe the Gita to be an essence of the Upanishads (texts that form the core of Hindu philosophy). Arjuna's dilemma is an allegory of our lives where our internal conflicts related to positive and negative dynamisms are fought on the battlefield of our minds. Teachings of the Gita communicated by Lord Krishna lead us to the right course of action. In many ways, resolution of conflict through the Gita is quite similar to the task of a mental health professional, who while addressing anxiety and conflicts of the patients, also helps them with symptom resolution and paves the path to long-term recovery. Several distinguished Indian psychiatrists have recommended the use of principles of the Bhagavad Gita for psychotherapy and healing.[2,3]

In this manuscript, we briefly discuss some of the parallels between the Gita and contemporary psychotherapies.

PSYCHODYNAMIC PSYCHOTHERAPY

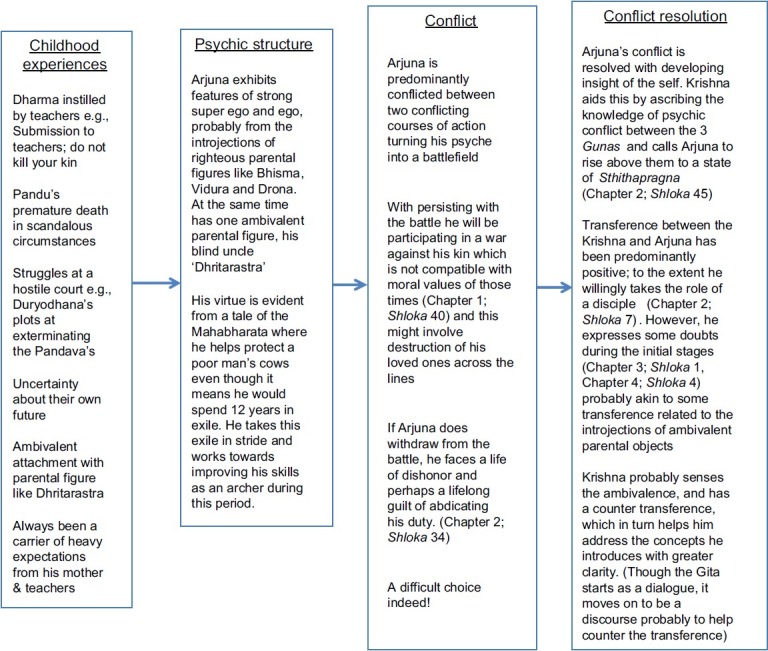

The central theme of psychodynamic theories is the presence of conflict related to unacceptable aspects of the self.[4] In several of these theories, the distress is about a conflict between internal dissonance and external requirement, and by striking a compromise between the two, one promotes adaptation.[4] According to Freud's structural theory, the conflict between the id, ego and superego is settled through the healthy ego defense mechanisms. The core theme of the Gita also involves a successful resolution of conflicts faced by Arjuna between parts of the three gunas i.e., tamsic, Rajas, Satwic forces, respectively having broader similarities between the id, ego and superego. Figure 1 illustrates several similarities from the teachings of the Gita with traditional psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Figure 1.

Psychodynamic theory and the Gita[22] (The verses describe the characteristics of the three gunas. “Satwa binds to happiness, Rajas to action, Tamas, over clouding wisdom, binds to lack of vigilance” Chapter 14; Shloka 9]. “Of these Satwa because it is pure, and it gives light and is the health of life, binds to earthly happiness and to lower knowledge.” [Chapter 14; Shloka 6]. “Darkness, inertia, negligence, elusion-these appear when Tamas prevails.” [Chapter 14; Shloka 13])

The Gita theorizes that senses (indriyas) produce attractions, which in turn lead to desire, and a lust for possession. In a pursuit to nurture and attain that desire, passion and anger may manifest themselves. Attributes like kaam (lust), krodh (unadaptive anger), lobh (greed), moh (insatiable attachment) and ahankar (unfounded self glorification) are tamsic in nature, with noticeable similarity to the id functions. The Gita describes hate and lust to be in an individual's lesser nature, comparable to the Freudian hierarchy of the id. The Gita argues that mind is superior to the power of the senses, analogous to theories describing the interaction between the ego and the super ego. It reasons that a “restless violence of senses” carries away the stable mind. It claims that passions generate confusion of the mind that leads to loss of reason and makes one forget his/her duty, which may finally culminate in self-destruction. The Gita describes several layers of consciousness and subconscious. There are several aspects of the unconscious described in psychodynamic literature including, the concept of collective unconsciousness by Jung. Interestingly, the idea of the whole world's unconscious (collective unconscious) blended into one, is analogous to the concept of “Atman” described in the Gita.

Of the three gunas mentioned above, Tamas also presents with self-centeredness and lack of regard for consequences, again with obvious similarities to the Id. The other two components of the three gunas, Rajas and Satwic are in many ways analogous respectively to the ego and superego. While Satwic qualities manifest as good thought, altruistic action and relationships, Rajas adopts goal directed action with an expectation of reward similar to ego function. Similar to Freudian psychodynamic psychotherapy, the three gunas are the sources of conflict and are involved in an everlasting tussle for supremacy that results in symptoms of anxiety. The Gita aims for an even higher mode for success in life than just harnessing the Satwic qualities. It recommends rising above these gunas and attaining the superior state of unperturbedness by having a mind that is steady, at peace and in a state of bliss.

Gaining insight is the goal of analytical therapy. The Gita and the Upanishads underscore this goal as well by stating that the achievement of “true knowledge of self does not lead to salvation, it is the salvation.”[5]

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

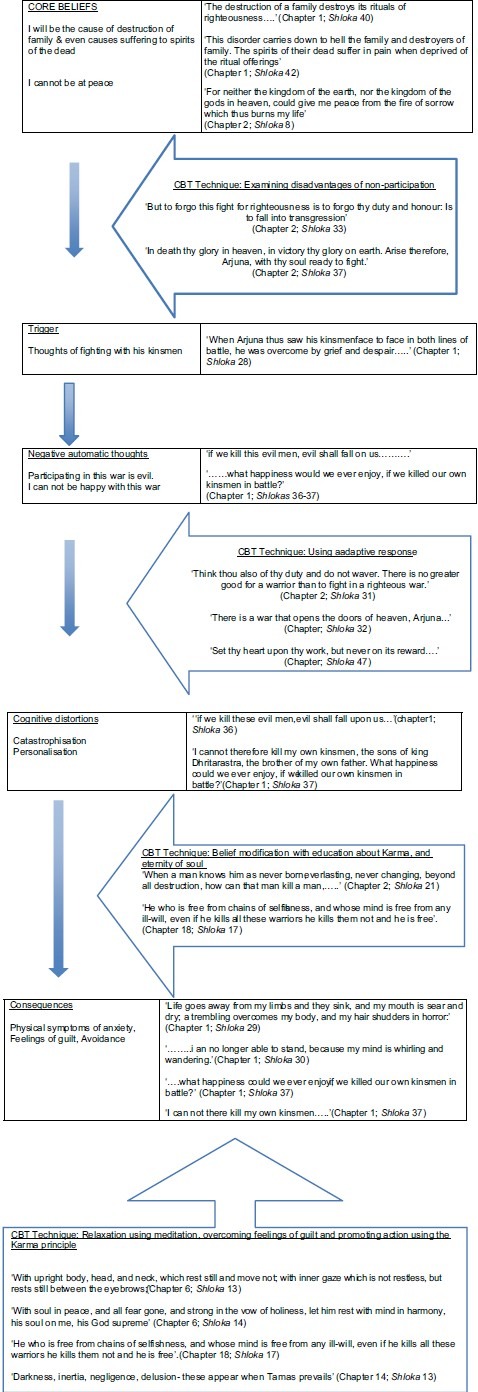

The Gita depicts what may probably be one of the earliest documented sessions in CBT. While fearing the negative consequences of the war, Arjuna visualizes the death of his relatives with associated guilt. The resulting anxiety manifests as distress with dry mouth, tremors, dizziness and confusion. He is so distressed that he considers relinquishing participation in the war and drops his weapons. Lord Krishna initially tries to motivate Arjuna describing the glories of a warrior and dishonor associated with non-participation, perhaps a motivational strategy used by the charioteer in those times. Having noted that this measure was inadequate, Lord Krishna delivers the Gita discourse. This helps to identify and remedy Arjuna's thought process and prepares him for action; a process akin to change brought by CBT.

In addition to catastrophizing the future, Arjuna experiences guilt and exhibits several other cognitive distortions [Figure 2]. To help combat Arjuna's dilemma, Lord Krishna explains that the distress he is in is transitory and emphasizes the importance of having an undistorted view of the world (akin to a view free of cognitive distortions). This is analogous to psychoeducation for an anxious subject where the therapist explains the transitory nature of anxiety, followed by an explanation of the role of cognitive distortions contributing to the symptoms. In his model on learned helplessness, Seligman theorized that patients perception and blaming themselves for events beyond their control, appeared to be a recurring theme of depression.[6] Lord Krishna addresses personalization, as Arjuna unfairly holds himself responsible for the destruction, by stating that all actions occur due to a natural course and an individual who perceives self to be cause for such actions, is deluded. Lord Krishna further addresses Arjuna's conflicts by introducing the concept of the soul (Atman) being eternal, and that Arjuna will not annihilate the enemies by destroying their worldly bodies, thereby relieving him of the responsibility of his enemy's earthly demise.

Figure 2.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and the Gita[22]

Later, Lord Krishna addresses the avoidance by Arjuna with the knowledge of Karma, perhaps the most important concept of the Gita. The concept of Karma yoga is unique whereby the action is in service of the Lord without attachment, or expectation of fruits, rewards or consequences. It encourages action, but discourages any attachment of the individual with the result. Detachment from the consequence helps alleviate possible distress or guilt associated with the action. This knowledge addresses the schema that one should not retaliate against family, however, evil they might be, removing a considerable weight off Arjuna's shoulders. The focus on action by an individual is emphasized on several chapters in the Gita and could be useful in addressing avoidance as a defense. The Gita states that a person attains perfection by action not by mere renunciation and that a man who withdraws from action is a false follower of the path. Lord Krishna discourages the dwelling on imaginary results (future telling, a cognitive distortion as in CBT). The cognitive-behavioral therapists often use the principles of reciprocal inhibition and prescribe the use of relaxation. The Gita recommends the use of relaxation via controlled breathing (pranayama) and meditation, as aids towards alleviating anxiety and achieving harmony. With several similarities between the process of CBT and the Gita discourse, we believe the examples from this scripture can be used to promote insight into one's own distorted thinking and motivate behavioral change.

MINDFULNESS

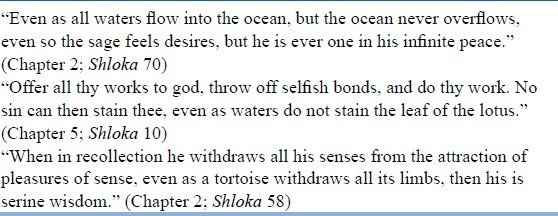

“Mindfulness” means “awareness” or “bare attention” and refers to a way of paying attention that is sensitive, accepting and independent of thoughts.[1] It is a way of being observant without being attached or affected. Though this is widely quoted as a Zen principle, the Gita has several references to this practice. The Gita prescribes mindfulness as a way of being detached from the onslaught of the senses, in order to attain the state of Sthithapragna (a state of unperturbedness). Some of the metaphors in the Gita describing this state [Table 1] are: “One should be tranquil like the ocean which is unaffected by rivers flowing into it,” “one should draw self away from the senses as a tortoise withdraws its limbs” and “being similar to water drop on a lotus leaf which does not have an attachment to the leaf.” Such metaphors from the Gita can be useful in guiding patients towards mindfulness. Lord Krishna suggests reaching the “mindful state” via meditation and maintaining self in calm and un-agitated state.

Table 1.

Notions on mindfulness[22]

Mindfulness is perhaps the most widely accepted eastern concept in psychotherapy. It is used in conjunction with CBT, DBT and Acceptance and Commitment therapy. With the proliferation of eclectic therapies, we can foresee more models using these techniques.

GRIEF EMANCIPATION, INTERPERSONAL AND OTHER THERAPIES

Loss of a loved one is one of the most stressful life event.[7] Listening to a discourse on the Bhagavad Gita is a routine practice at a Hindu funeral, congruent with the popular belief that it helps with the grief process. One pertinent aspect of the Gita in this context is its theory of reincarnation. It provides relations of the deceased solace that the actual soul, the key part of the deceased is eternal, and it is just the body, a carrier of the soul that is destroyed. The Gita also talks of inevitability of death and the reincarnation process, thereby reducing the intensity of the grief.

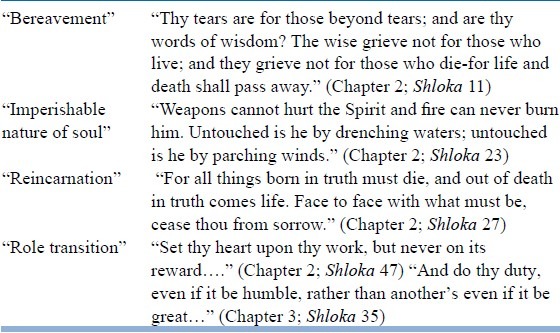

Re-establishing interests and relationships are one of the key aspects of addressing grief in interpersonal therapy (IPT) [Table 2].[8] The Gita can be used to motivate the patient move along the grief process. Visiting Gita's concept that “the supreme being carries off all things” can aid alleviate the guilt towards the deceased by diffusing the responsibility towards god. Some of these concepts have a heavy tone of spirituality and religion; hence the patient's beliefs should be explored and respected prior to using excerpts from the Gita as an adjunct to grief therapy.

Table 2.

Shlokas useful in addressing grief and role transition[22]

One of the core strategies used in IPT involves role transition.[8] This concept often involves the individual romanticizing about their previous role and thereby, hesitating to adopt a new role. This change also causes distress. The Gita prescribes action without expecting the reward, and at the same time, advises not to judge one's duty, either as humble or great, a philosophy that aids successful transition. The concept of duty but not taking the responsibility of the consequences modifies expectations towards the new role. Another phase of the IPT, which may also aid role transition, is restoration of self-esteem. In the Gita, Krishna addresses Arjuna “paramthapa” (chastiser of enemies), “purushasresta” (noblest of men) and several similar positive adjectives by highlighting his strengths and thereby promoting self-esteem.

Among the addiction treatments to date, the success of the Alcoholic Anonymous (AA) program has not been duplicated.[9] AA being a spirituality-based program is congruent with the Gita.[10] Gita encourages introspection, degree of weakness over one's senses and the power the senses have over an individual. This also instills hope of controlling the senses.

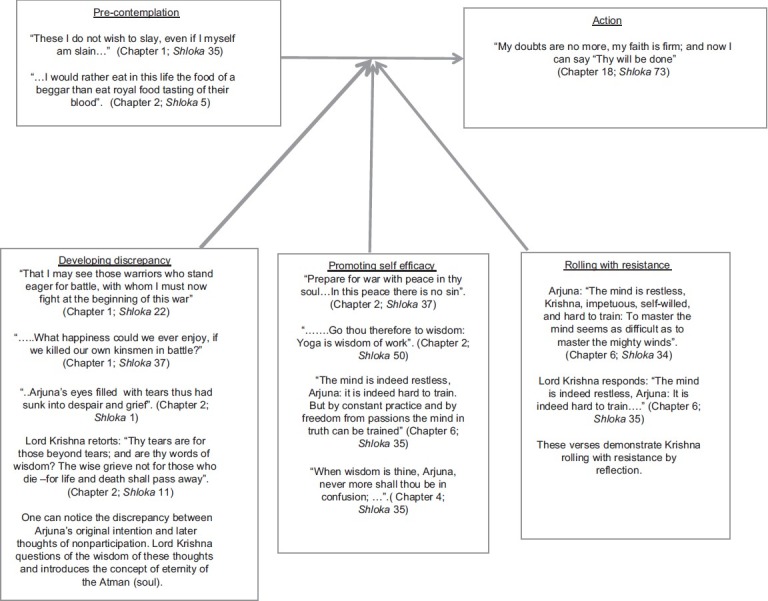

Often the major problem with addictions is a lack of motivation towards change, Motivational Enhancement therapy developed by Miller and Rollnick is widely regarded as the best in overcoming this problem.[11] Developing discrepancy and promoting self-efficacy are some of the key elements of this therapy. During the Gita discourse, Lord Krishna cleverly points out the discrepancy between Arjuna's action and words, instills hope that the mind can be mastered [Figure 3]. He also promotes self-efficacy by setting his disciple on the course of action from the state of pre-contemplation.

Figure 3.

Motivational enhancement therapy[22] (Motivational enhancement therapy can be used to move any person through the stages of change. It is commonly used in Addictions. These Shlokas [Chapter 2; Shlokas 42-44, 64, 67, 71. Chapter 3; Shlokas 7, 38, 39, 41. Chapter 16; Shloka 21] in the Gita, might be useful in addiction therapies)

Furthermore, the patients with psychiatric disorders have a higher prevalence of physical health morbidities relative to the general population.[12] Krishna prescribes regulated sleep and good dietary habits. The body is described as the Lord's Kshetra (abode) or temple, hence making it pertinent for an individual to take care of it and thereby providing the Lord the best place to reside in. With unhealthy lifestyles contributing significantly to physical comorbidity Gita's wisdom may be useful in remedying this.

Supportive psychotherapy is eclectic and practical in approach, and is perhaps the most common used psychotherapeutic modality by psychiatrists and mental health practitioners around the globe.[13] Similar to Lord Krishna's intentions for Arjuna, the therapist uses a conversational style and creates a holding environment for improving self-esteem. Here, Arjuna's perceptions are reframed and universalized by addressing his predicament, a “tactical” supportive psychotherapy technique. For example, killing of relatives, a worry for Arjuna is reframed as doing one's duty. In this way, The Gita does not point fingers at Arjuna but focuses on the human way of life thereby universalizing his anguish. Other striking similarities are providing pragmatic guidance by emphasizing teaching, giving advice, developing adaptive behavior and anticipatory guidance.

CONCLUSION

The success of the spirituality based therapies in AA and mindfulness has not resulted in spirituality being embedded in part of routine psychiatric practice. One of the barriers to the application of spirituality in improving the health of patients and promoting healing has been the belief system of psychiatrists themselves. Compared to the general population, there is a high prevalence of atheism and agnostism among this population.[14] There is some line of thought among psychiatrists that sharing religious beliefs amounts to boundary violation.[15] However, the dictum of medical ethics is not impinging on patient's own religious-spiritual beliefs but at the same time religious-spiritual views of a physician should not preclude the prescription of a useful spiritual intervention, which are consistent with the patient's belief. In their recent guidelines, The Royal College of Psychiatrists recommends working with spiritual leaders as warranted in treating patients.[16] The Zen principles have received acceptance among the psychiatrists and patients worldwide irrespective of spiritual and religious backgrounds. Similarly, one needs to note that the Gita also has wide secular content, which could be harnessed to benefit patients. Spiritually, through many paths, including placebo, may help patients.[17] We therefore, recommend psychiatrist and mental health practitioners to use spirituality as a part of their therapeutic armamentarium.

Whilst the cultural background can determine psychopathology and it is also a determinant for the acceptance of a particular treatment,[18] to the extent western psychotherapies are considered inapplicable in some eastern cultures.[19] The key aspects influencing the process of psychotherapy is trust and communication.[20] Pragmatic use of the Gita can potentially improve both. In contrast to western psychotherapy practice the dyadic relationship between guru and chela,[21] similar to the one between Krishna and Arjuna has more appeal to Indian patients and should be exploited for better therapeutic outcome.

With a rise in the number of psychotherapies in the recent years, majority being eclectic, we hope for therapy models embedded in the wisdom of the Gita may add additional content to western psychotherapies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Mace C. Mindfulness in psychotherapy: An introduction. Adv Psych Treatment. 2007;13:147–54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govindaswamy MV. Surrender-not to self-surrender. Trans. 1959;2:i–x. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao AV, Parvathidevi S. The Bhagavad Gita treats body and mind. Indian J Hist Med. 1974;19:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman A, Brown D, Peddar J. In: The concept of conflict. Introduction to Psychotherapy: An Outline of Psychodynamic Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Bateman A, Brown D, Peddar J, editors. Hove: Routledge; 2010. pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mascaro J. Translator's introduction to 1962 edition. The Bhagavad Gita. Bungay: Penguin; 1962. p. xii. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiroto DS, Seligman ME. “Generality of learned helplessness in man”. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1975;31:311–27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–8. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissman MW, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Chapter: An outline of IPT. Clinician's Quick Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York: Oxford press; 2007. pp. ix–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferri M, Amato L, Davoli M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programmes for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD005032. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005032.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alcoholics Anonymous: The Big Book. 4th ed. NewYork: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 2001. [Last Accessed:23rd Oct. 2012]. Alcoholics anonymous. Available from: http://www.aa.org/bigbookonline/en_tableofcnt.cfm . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change. NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sartorius N. Physical illness in people with mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2007;6:3–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal RN. Techniques of Individual Supportive Psychotherapy. In: Gabbard GO, editor. Textbook of Psychotherapeutic Treatments. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2008. p. 417. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curlin FA, Odell SV, Lawrence RE, Chin MH, Lantos JD, Meador KG, et al. The relationship between psychiatry and religion among U.S. physicians. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:1193–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.9.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkar SP. Praying with patients: Belief, faith and boundary conditions. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:516–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.199.6.516a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook CH. Recommendations for psychiatrists on spirituality and religion. The Royal College of Psychiatrists. Position Statement: PS03/2011. [Last Accessed on 2012 Dec 2]. Available from: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/PS03_2011.pdf .

- 17.Proctor W, Benson J. Christian Mind Body Healing Strategies. Vero Beach: Inkslingers press; 2011. Benson Story: My mother and mind body therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhugra D, Osbourne TR. Spirituality and psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46:5–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surya NC, Jayaram SS. Some Basic Considerations in the practice of Psychotherapy in the Indian setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 1964;1:153–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bateman A, Brown D. Introduction to Psychotherapy: An Outline of Psychodynamic Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Hove: Routledge; 2010. Elements of psychotherapy; pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neki JS. Guru-chela relationship: The possibility of a therapeutic paradigm. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1973;43:755–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1973.tb00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mascaro J. Chapters 1-18. The Bhagavd Gita. Bungay: Penguin; 1962. pp. 3–86. (Reprinted 2003) [Google Scholar]