Abstract

Background

Hundreds of non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (nsSNVs) have been identified in the two most common LQTS-susceptibility genes (KCNQ1 and KCNH2). Unfortunately, a ~3% background rate of rare KCNQ1 and KCNH2 nsSNVs amongst healthy individuals complicates the ability to distinguish rare pathogenic mutations from similarly rare yet presumably innocuous variants.

Methods and Results

In this study, 4 tools [1) conservation across species, 2) Grantham values, 3) SIFT, and 4) PolyPhen] were used to predict “pathogenic” or “benign” status for nsSNVs identified across 388 clinically “definite” LQTS cases and 1344 ostensibly healthy controls. From these data, estimated predictive values (EPVs) were determined for each tool independently, in concert with previously published protein topology-derived EPVs, and synergistically when ≥ 3 tools were in agreement. Overall, all 4 tools displayed a statistically significant ability to distinguish between case-derived and control-derived nsSNVs in KCNQ1, whereas each tool, except Grantham values, displayed a similar ability to differentiate KCNH2 nsSNVs. Collectively, when at least 3 of the 4 tools agreed on the “pathogenic” status of C-terminal nsSNVs located outside the KCNH2/Kv11.1 cyclic nucleotide binding domain, the topology-specific EPV improved from 56% to 91%.

Conclusions

While in silico prediction tools should not be used to predict independently the pathogenicity of a novel, rare nSNV, our results support the potential clinical utility of the synergistic use of these tools to enhance the classification of nsSNVs, particularly for Kv11.1’s difficult to interpret C-terminal region.

Keywords: genetic variation, genetics, ion channels, long-QT syndrome, pediatrics

Background

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a heritable disease of myocardial repolarization characterized by a prolonged heart rate-corrected QT interval (QTc) on electrocardiogram (ECG) and increased risk of torsades de pointes-triggered syncope and sudden death.1 At present, congenital LQTS can be caused by mutations in at least 13 distinct LQTS-susceptibility genes that principally perturb potassium (K+) channel function. However, ~65% of all LQTS cases are caused by loss-of-function mutations in the KCNQ1-encoded Kv7.1/KvLQT1 and KCNH2-encoded Kv11.1/hERG K+ channels responsible for type 1 (LQT1) and type 2 (LQT2), respectively.2–6 Numerous genotype-phenotype correlation studies have established genotype-specific ECG patterns, arrhythmogenic triggers, responses to pharmacotherapy, and diagnostic provocation studies.7 As such, genetic testing has assumed a critical role in both the diagnosis and clinical management of LQTS patients elevating the LQTS genetic test from a pseudo-clinical research laboratory-based entity beginning in 1995 to a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-approved commercial test in 2004.

With the increasingly widespread availability of genetic testing and the possibility of the personal genome on the horizon, inevitably more patients will undergo some form of genetic testing, dramatically increasing the potential that rare variants of unknown/uncertain significance (VUS) will be unearthed in established disease-susceptibility genes. As a result, the interpretation of genetic testing results, especially in the setting of insufficient or inconclusive clinical evidence of disease, can present a daunting challenge.8, 9 When attempting to ascribe meaning to LQTS genetic test results, physicians on one hand must consider the high prevalence of mutation-positive individuals with concealed clinical phenotypes owing to incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity10, 11 and on the other hand, the estimated 1 in 25 otherwise healthy individuals expected to harbor a rare, and most likely innocuous, variant within one of the 3 major LQTS-susceptibility genes.12, 13

One of the primary challenges that complicates the interpretation of LQTS genetic test results is the classification of rare non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (nsSNVs), also known as missense mutations, which represent ~75% of positive test results.14 While nonsense, insertion, deletion, and splice-site mutations, so called “radical” mutations because they scramble, add to, or subtract from the resulting protein product, carry an extremely high (> 95%) estimated predictive value (EPV, the probability that a variant found in a case is pathogenic) regardless of their location, the ability to calculate EPVs for nsSNVs is dependent largely on the specific structure-function domain to which the nsSNV localizes.15 In addition to localizing to specific structure-function domains, previous studies suggest that pathogenic missense mutations in the Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 K+ channels preferentially localize to highly conserved residues and involve more severe biochemical amino acid substitutions independent of protein topology.16, 17

Accordingly, commonly used in silico tools developed to assess the phylogenetic and or physicochemical properties of those amino acids altered by nsSNVs such as conservation analysis, Grantham values, SIFT (“sorting intolerant from tolerant”), PolyPhen2 (“polymorphism phenotyping”) have the potential to enhance the classification of nsSNVs, particularly for variants localizing to problematic regions. However, the relative ability of these in silico tools to classify KCNQ1 and KCNH2 nsSNVs and improve the signal-to-noise ratio currently associated with LQTS genetic testing remains unknown.

In an effort to objectively assess the ability of the aforementioned set of in silico tools to enhance the diagnostic interpretation of nsSNVs in KCNQ1 and KCNH2, a large multicenter case-control study comparing the phylogenetic and physicochemical properties of rare nsSNVs identified in high-probability clinical cases with those similarly rare nsSNVs identified in healthy volunteers was conducted. Here, we demonstrate that the synergistic use of multiple in silico tools can enhance the ability to distinguish pathogenic from benign nsSNVs in certain problematic topological regions, but should not be used in isolation as independent determinants of KCNQ1 and KCNH2 nsSNV pathogenicity.

Methods

Study Design

From 1997 to 2007, > 1300 patients were referred to Mayo Clinic’s Windland Smith Rice Sudden Death Genomics Laboratory (Rochester, MN), the Cardiogenetics Clinic at the Academic Medical Center (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), or PGxHealth’s commercial laboratory (New Haven, CT; now a part of Transgenomic, Inc.) for comprehensive LQTS genetic testing after receipt of written informed consent. In an effort to increase the a priori or pre-genetic test probability that a case-derived nsSNV would be a pathogenic LQT1- or LQT2-causative mutation, this study was limited to “clinically definite” LQTS cases amounting to 388 of the total referral population.

For the purposes of this study, “clinically definite” cases were defined as those with a diagnostic score (a.k.a. Schwartz score18) ≥ 3.5 or a QTc ≥ 480 milliseconds on ECG. Those cases with acquired cardiac diseases, electrolyte abnormalities, and or on QT prolonging medications were excluded from this study. Furthermore, given that radical mutations (splice-site, nonsense, frame-shift, or in-frame insertions/deletions) already confer an EPV >99% regardless of gene or location within channel topology and that the limited number of cases and controls harboring nsSNVs in the SCN5A gene and 10 minor LQTS genes, only those cases harboring nsSNVs in the KCNQ1 and KCNH2 genes were analyzed in this study. All cases were unrelated and the demographics including ethnicity, age, and sex as well as the ethnic- and gene-specific mutation rates were reported previously.15

The phylogenetic and physicochemical properties of case-derived nsSNVs as assessed by commonly used in silico prediction tools were compared with those genetic variants found among an ostensibly healthy controls in order to assess the ability of each tool to differentiate pathogenic from benign nsSNVs located throughout the entire KCNQ1 and KCNH2 coding regions, and within specific regions in the Kv7.1 or Kv11.1 protein topology. In the context of this study, the term “healthy control population” is meant to imply a group of anonymous volunteers who were apparently healthy at the time of collection. However, neither an ECG displaying a normal QT interval or a thorough cardiovascular examination was a prerequisite for subjects in this control population. The previously published control population consisted of over 1300 unrelated, ostensibly healthy volunteers previously analyzed for K+ channel genetic variants.12, 15 The ethnic distribution of individuals within this control population was reported previously.15

LQTS Genetic Testing

Genomic DNA from all cases and controls were analyzed for genetic variants in the translated exons and splice-site junctions of the KCNQ1 and KCNH2 gene using polymerase chain reaction and either denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography, followed by direct DNA sequencing, or direct high-throughput DNA sequencing as described previously.15

nsSNV Interpretation and Mutation Sequence Analysis

For the purposes of this study, only those nsSNVs (by definition codon- and amino acid-altering genetic variants) identified in a “clinically definite” LQTS case that were also absent in the control population were considered to be potentially pathogenic mutations. Importantly, the term “mutation” in this study is not intended to imply pathogenicity or even functional abnormality; but rather it indicates that a particular nsSNV is rare (i.e. seen in single/multiple cases but not controls or in a single control), amino acid altering, and if encountered during the course of clinical LQTS genetic testing would be considered a potentially pathogenic variant.

Identified mutations were overlaid on the linear protein topologies of Kv7.1 and Kv11.1, respectively. The linear protein topology was annotated to define functionally important domains and structural regions within each channel according to the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot databank (http://ca.expasy.org/uniprot)19 and studies of the genomic and protein organization for KCNQ1/Kv7.1 and KCNH2/Kv11.1.20, 21

Phylogenetic- and or Physicochemical-Based Phenotype Prediction Analyses

In order to assess the phylogenetic properties of nsSNVs, sequence conservation analysis was conducted using primary sequences from the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/).22 In order to calculate the degree of conservation across species, the primary sequences from 44 species including primates, other placental mammals, monotremes, and non-mammalian vertebrates were aligned. The number of substitutions at each position (degree of nonidentity) was calculated by assessing the number of primary sequences at each position that harbored a residue that did not match the corresponding human residue. Genetic variants were then classified as occurring at a position with either no substitutions or ≥ 1 substitution(s).

SIFT, version 4.0.5, an additional conservation-based metric was used to analyze the Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 protein sequences and provide phenotype predictions for each nsSNV identified in cases and controls using the default settings. The assumptions and exact methodology employed by the current version of the SIFT algorithm have been described previously.23 For the purposes of this study, nsSNVs were classified as either “Tolerated” or “Damaging” based on the SIFT prediction.

In order to assess the physicochemical properties of nsSNVs, Grantham chemical scores were calculated using the Grantham amino acid difference matrix as previously described.24 Grantham values range from 15 (most conservative) to 215 (most radical), with values ≥ 150 considered radical, 100 to 149 considered moderately radical, 50 to 99 considered moderately conservative, and < 50 considered conservative. For the purposes of this study, nsSNVs were classified as radical (Grantham value ≥ 100) or conservative (Grantham value < 100).

PolyPhen2, version 2.1.0, was used to analyze the effect of nsSNVs on the secondary and tertiary protein structure of the Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 K+ channels using information derived from the Protein Databank (PDB) and Database of Secondary Structure Assignments (DSSP) using default settings. The assumptions and exact methodology of the PolyPhen algorithm have been described previously.25 PolyPhen classified each variant as “probably damaging”, “possibly damaging”, or “benign”. For this study, those nsSNVs labeled as “probably damaging” or “possibly damaging” were combined as “damaging”.

Statistical Analysis

For the purpose of calculating the frequency of nsSNVs predicted to be pathogenic by each in silico tool, rare control nsSNVs (identified in a single control) and common control nsSNVs/polymorphisms (identified in multiple cases and controls) were combined to obtain a raw count of unique nsSNVs observed in controls. A one-tailed Fisher exact test with a threshold of significance set at p < 0.05 was then employed to compare raw counts of unique case nsSNVs (indentified in single/multiple cases but not controls) and unique control nsSNVs (identified in a single control or multiple cases and controls) predicted to be pathogenic by each algorithm on the basis of their phylogenetic and or physicochemical properties.

In order to estimate the likelihood of disease causation, a modified estimated predictive value (EPV, defined as the probability of pathogenicity for a mutation identified in a case) was used as described previously15 and in the supplemental methods. Importantly, variants seen in multiple controls were considered polymorphisms and excluded from EPV analysis, whereas those seen once constituted the “rare, control nsSNVs”. As such, common polymorphisms such as KCNH2-K897T did not influence the calculation of EPVs.

Results

A total of 108 unique rare nsSNVs (52 in KCNQ1 and 56 in KCNH2, a list of case nsSNVs is provided in the supplement) were identified in 158 unrelated “clinically definite” LQTS cases, whereas 41 unique rare nsSNVs (14 in KCNQ1 and 27 in KCNH2) were identified in 41 individual controls. In order to fully assess the ability of the four in silico tools (species conservation, grantham values, SIFT, and PolyPhen) to differentiate between pathogenic and benign nsSNVS on the basis of their phylogenetic and physicochemical properties the 13 unique common nsSNVs/polymorphisms (6 in KCNQ1 and 7 in KCNH2) identified in multiple cases and controls were included in the raw control count bringing the total number of distinct control nsSNVs (rare and common) used for the individual “predictive” analysis to 54 (20 in KCNQ1 and 34 in KCNH2, a list of control nsSNVs is provided in the supplement).

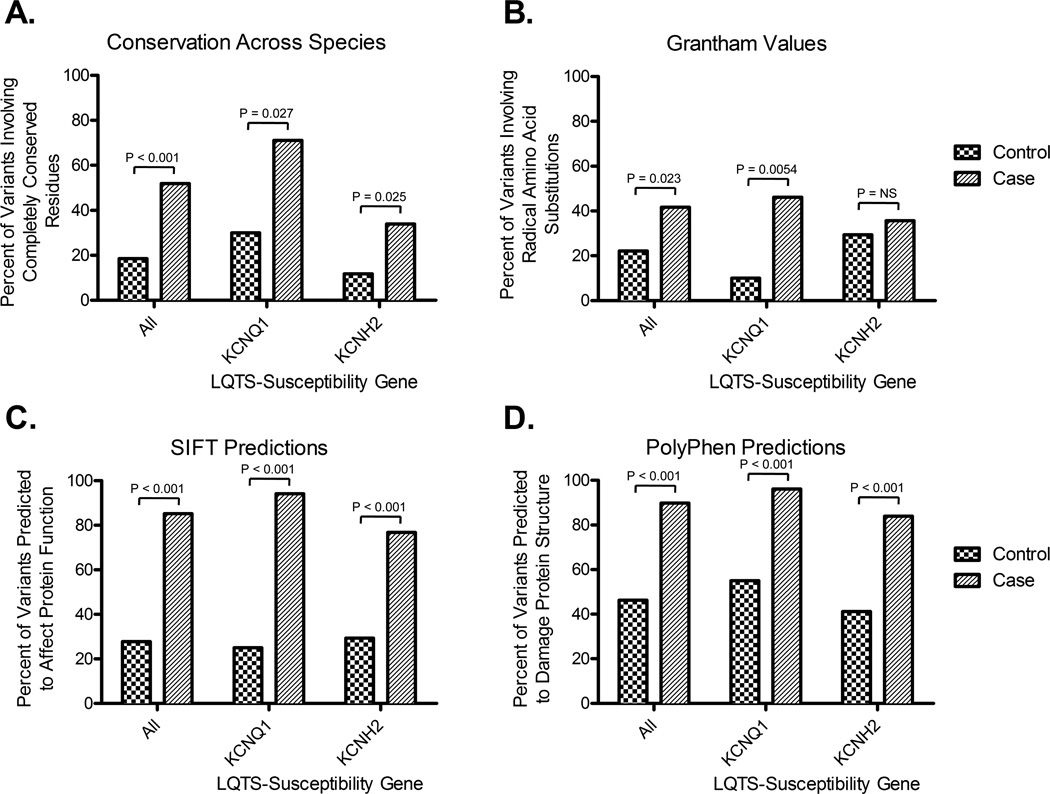

Differentiation of Case- vs. Control-Derived nsSNVs by Species Conservation

Overall, 56 out of 108 (52%) nsSNVs identified in cases localized to residues with zero substitutions whereas only 10 out of 54 (19%, p < 0.001) control-derived nsSNVs localized to residues with zero substitutions (Figure 1A). Gene-specific subset analysis demonstrated that 37 out of 52 (71%) case-derived KCNQ1 nsSNVs localized to residues with zero substitutions compared to 6 out of 20 (30%, p = 0.0027) control-derived nsSNVs involving KCNQ1. Similarly for KCNH2, 19/56 (34%) cases vs. 4/34 (12%, p = 0.025) for controls involved KCNH2 nsSNVs with zero substitutions. The overall EPV for nsSNVs that alter completely conserved residues was 97% (95% CI, 94 to 98), whereas the KCNQ1-specific and KCNH2-specific EPVs were 97% (95% CI, 94 to 99) and 95% (95% CI, 86 to 98), respectively (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic- and physicochemical-based classification of nsSNVs identified in cases and controls. A) Percentage of nsSNVs identified in cases or controls localizing to residues with 0 substitutions across 44 species. B) Percentage of all nsSNVs identified in cases or controls predicted to be a “radical” amino acid substitution based on Grantham chemical score. C) Percentage of nsSNVs identified in cases or controls predicted to affect protein structure by the SIFT algorithm. D) Percentage of nsSNVs in cases and controls predicted to damage protein structure by the PolyPhen algorithm. For the purposes of this study, Grantham values ≥ 100 were considered the threshold for “radical”, SIFT predictions of “damaging” were considered to affect protein structure, and PolyPhen predictions of “probably damaging” and “possibly damaging” were considered to potentially damage protein structure. All frequencies represent single variant counts (i.e. each nsSNV was counted only once) and p-values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Table 1.

EPVs for each in silico prediction tool by LQTS-susceptibility gene

| Gene and prediction algorithm | Case % pathogenic |

Control % pathogenic |

Pathogenic EPV* (95% CI) |

Benign EPV* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (KCNQ1 and KCNH2) | (N= 158) | (N = 41) | ||

| Conservation across species | 58% | 24% | 97 (94–98) | 87 (80–91) |

| Grantham value | 44% | 20% | 97 (93–98) | 89 (84–93) |

| SIFT | 99% | 80% | 94 (91–96) | 0 (0–75) |

| PolyPhen | 93% | 46% | 96 (94–98) | 42 (0–72) |

| KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) | (N = 86) | (N = 14) | ||

| Conservation across species | 78% | 43% | 97 (94–99) | 88 (72–95) |

| Grantham value | 54% | 7% | 99 (95–100) | 91 (83–95) |

| SIFT | 100% | 79% | 96 (93–98) | 0 (0–98) |

| PolyPhen | 98% | 64% | 97 (94–98) | 28 (0–86) |

| KCNH2 (Kv11.1) | (N = 72) | (N = 27) | ||

| Conservation across species | 33% | 15% | 95 (86–98) | 86 (78–92) |

| Grantham value | 33% | 26% | 90 (77–96) | 84 (73–91) |

| SIFT | 97% | 81% | 91 (86–94) | 29 (0–86) |

| PolyPhen | 88% | 37% | 96 (91–98) | 46 (0–76) |

EPV = (case rate – control rate)/case rate.

Differentiation of Case- vs. Control-Derived nsSNVs by Grantham Chemical Values

As depicted in Figure 1B, 44/108 (42%) case-derived nsSNVs were predicted to cause radical biochemical amino acid substitutions compared to 12/54 (22%, p = 0.023) nsSNVs found in controls. Limiting the analysis to KCNQ1, 24/52 (46%) case-derived nsSNVs resulted in radical substitutions whereas only 2 out of 20 (10%, p = 0.0054) KCNQ1 nsSNVs in controls were “radical” with respect to their Grantham chemical value (i.e. > 100) (Figure 1B). However, for KCNH2, there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of nsSNVs that caused radical amino acid substitutions between cases and controls (Figure 1B). The overall EPV for nsSNVs predicted to cause radical amino acid substitutions was 97% (95% CI, 93 to 98), whereas the KCNQ1-specific and KCNH2-specific EPVs were 99% (95% CI, 95 to 100) and 90% (95% CI, 77 to 96), respectively (Table 1).

Differentiation of Case- vs. Control-Derived nsSNVs by SIFT

Overall, 92/108 (85%) case-derived nsSNVs were predicted by SIFT to be “damaging” compared to only 15 out of 54 (28%, p < 0.001) control-derived nsSNVs (Figure 1C). When the analyses were limited to either KCNQ1 or KCNH2, statistically significant differences in the frequency of nsSNVs predicted to be “damaging” by SIFT were also observed between cases versus controls (Figure 1C). The overall EPV for nsSNVs predicted by SIFT to be “damaging” was 94% (95% CI, 91 to 96), whereas the KCNQ1-specific and KCNH2-specific EPVs were 96% (95% CI, 93 to 98) and 91% (95% CI, 86 to 94), respectively (Table 1).

Differentiation of Case- vs. Control-Derived nsSNVs by PolyPhen

As depicted in Figure 1D, 97/108 (90%) case-derived nsSNVs were predicted by PolyPhen to be “possibly pathogenic” or “probably pathogenic” compared to 25/54 (46%, p < 0.001) control nsSNVs. Similar to SIFT, when a gene-specific analyses was conducted statistically significant differences in the frequency of KCNQ1 and KCNH2 nsSNVs predicted to be “possibly damaging” or “probably damaging” by PolyPhen were observed between cases versus controls (Figure 1D). The overall EPV for nsSNVs predicted by PolyPhen to be “possibly damaging” or “probably damaging” was 96% (95% CI, 94 to 98), whereas KCNQ1-specific and KCNH2-specific EPVs were 97%; (95% CI, 94 to 98) and 96% (95% CI, 91 to 98), respectively (Table 1).

Enhancement of Gene-Specific EPV Analysis by these In Silico Bioinformatic Tools

In a multivariate analysis, for already high EPV regions (e.g. transmembrane/pore domains), coupling an individual tool with protein topology did not enhance or only modestly enhanced the region-specific EPV (Table 2), indicating that protein topology rather than the phylogenetic/physicochemical properties is the primary determinant in these regions. Stated in reverse, topology is a strong surrogate for phylogenic and physiochemical constraints.

Table 2.

Comparison of EPVs when protein topology is coupled with prediction tools

| EPVs* for topology plus in silico prediction algorithm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCSC Conservation | Grantham | SIFT | PolyPhen | ||||||

| Protein and location | Topology | Pathogenic | Benign | Pathogenic | Benign | Pathogenic | Benign | Pathogenic | Benign |

| KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) | |||||||||

| N terminus | 71 (0–98) | 71 (0–100) | 71 (0–98) | 71 (0–100) | 99 (0–99) | 71 (0–98) | 71 (0–100) | 71 (0–100) | 99 (0–98) |

| Transmembrane/linker/pore | 96 (91–98) | 97 (91–99) | 92 (72–98) | 99 (90–100) | 93 (84–97) | 97 (93–99) | 0 (0–99) | 97 (93–99) | 0 (0–99) |

| C terminus (total) | 95 (89–98) | 98 (92–99) | 83 (43–95) | 100 (40–100) | 86 (65–95) | 96 (90–98) | 0 (0–100) | 97 (91–99) | 45 (0–94) |

| SAD | 100 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) | 100 (90–99) | 100 (0–100) | 71 (0–100) | 100 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) |

| Outside SAD | 94 (86–98) | 98 (92–100) | 62 (0–87) | 100 (38–100) | 75 (27–92) | 95 (88–98) | 0 (0–100) | 96 (89–99) | 0 (0–99) |

| KCNH2 (Kv11.1) | |||||||||

| N terminus (total) | 63 (16–83) | 0 (0–99) | 68 (26–86) | 82 (27–96) | 42 (90–99) | 68 (26–86) | 0 (0–99) | 80 (31–34) | 36 (0–80) |

| PAS domain | 99 (0–100) | 72 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 72 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 72 (0–100) |

| PAC domain | 99 (0–100) | 72 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 72 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) | 97 (0–100) |

| Outside PAS/PAC | 26 (0–74) | 0 (0–99) | 38 (0–78) | 57 (0–93) | 5 (0–74) | 38 (0–78) | 0 (0–99) | 43 (0–90) | 15 (0–77) |

| Transmembrane/linker/pore | 100 (70–100) | 100 (11–100) | 100 (55–100) | 100 (5–100) | 100 (56–100) | 100 (70–100) | 97 (0–100) | 100 (68–100) | 99 (0–99) |

| cNBD | 100 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 100 (0–99) | 72 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) |

| C-terminus (outside cNBD) | 56 (0–81) | 89 (42–98) | 15 (0–72) | 0 (0–87) | 65 (11–86) | 61 (4–84) | 15 (0–91) | 79 (39–93) | 0 (0–72) |

EPV = (case rate – control rate)/case rate.

For the problematic C-terminal regions outside the Kv7.1 subunit assembly domain (SAD) and the Kv11.1 cyclic nucleotide-binding domain (cNBD), the additional use of most in silico tools enhanced the region-specific EPVs (Table 2). This effect was most pronounced for KCNH2 outside the cNBD of the Kv11.1 C-terminus, where the species conservation, SIFT, and PolyPhen algorithms increased the region-specific EPV from 56% (95% CI, 0 to 81) for topology-only to 89% (95% CI, 42 to 98), 61% (95% CI, 4 to 84), and 79% (95% CI, 39 to 93), respectively (Table 2). Unfortunately, the EPVs for any single algorithm plus topology failed to reach the 90–95% range needed to make this particular region-specific EPV clinically useful.

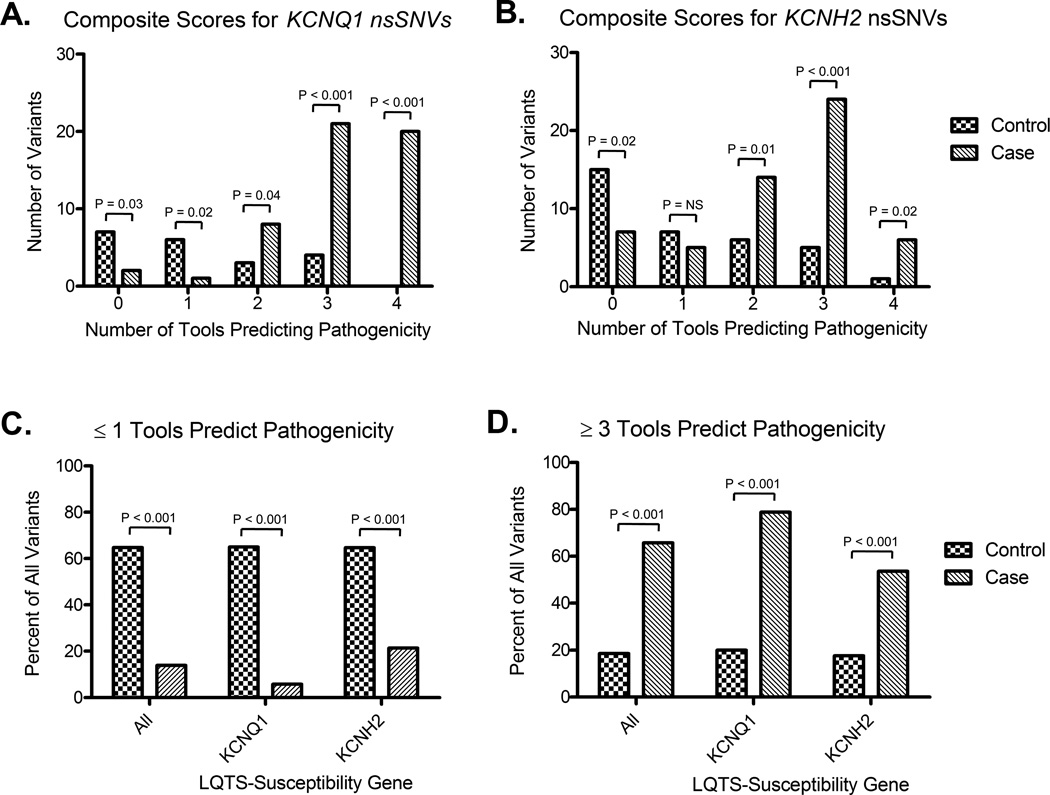

As a result, we looked to leverage the more conservative predictions (i.e. more false negatives) rendered by the species conservation and Grantham chemical matrix algorithms and the more liberal predictions (i.e. more false positives) rendered by the SIFT and PolyPhen algorithms (summarized in Table 1), by combining the predictive power of each algorithm to create a composite score that reflects the number of algorithms that agreed on the potential pathogenicity of a given variant. The raw number of case and control nsSNVs where 0, 1, 2, 3, or all 4 algorithms agreed on the predicted pathogenicity are summarized in Figure 2A and Figure 2B, respectively.

Figure 2.

Synergistic classification of case- and control-derived nsSNVs when multiple in silico algorithms are agreement. A) Number of case- and control-derived KCNQ1 nsSNVs where 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 in silico tools predict pathogenicity. B) Number of case- and control-derived KCNH2 nsSNVs where 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 in silico tools predict pathogenicity. C) Percentage of nsSNVs identified in cases or controls predicted by ≤ 1 in silico tool as being pathogenic based on phylogenetic and physicochemical properties. D) Percentage of nsSNVs identified in cases or controls predicted by ≥ 3 in silico tool as being pathogenic based on phylogenetic and physicochemical properties. All frequencies represent single variant counts (i.e. each nsSNV was counted only once) and p-values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Given that several individual composite scores (e.g. 3 and 4 in agreement for both KCNQ1 and KCNH2) showed a significant ability to differentiate between rare nsSNVS identified in cases and controls, we next looked to assess if the use of combined composite scores of ≤ 1 and ≥ 3 could be used to further enhance the differentiation of case and control nsSNVs. Overall, only 15/108 (14%) of case-derived nsSNVs were predicted to be pathogenic by ≤ 1 tool compared to 35/54 (65%, p < 0.001) of all control-derived nsSNVs (Figure 2A). Similarly, 71/108 (66%) of case-derived nsSNVs were predicted to be pathogenic by ≥ 3 tools compared to only 10/54 (18.5%, p < 0.001) control-derived nsSNVs (Figure 2B). Results for KCNQ1- and KCNH2-specific predictions were similar and are summarized in Figure 2.

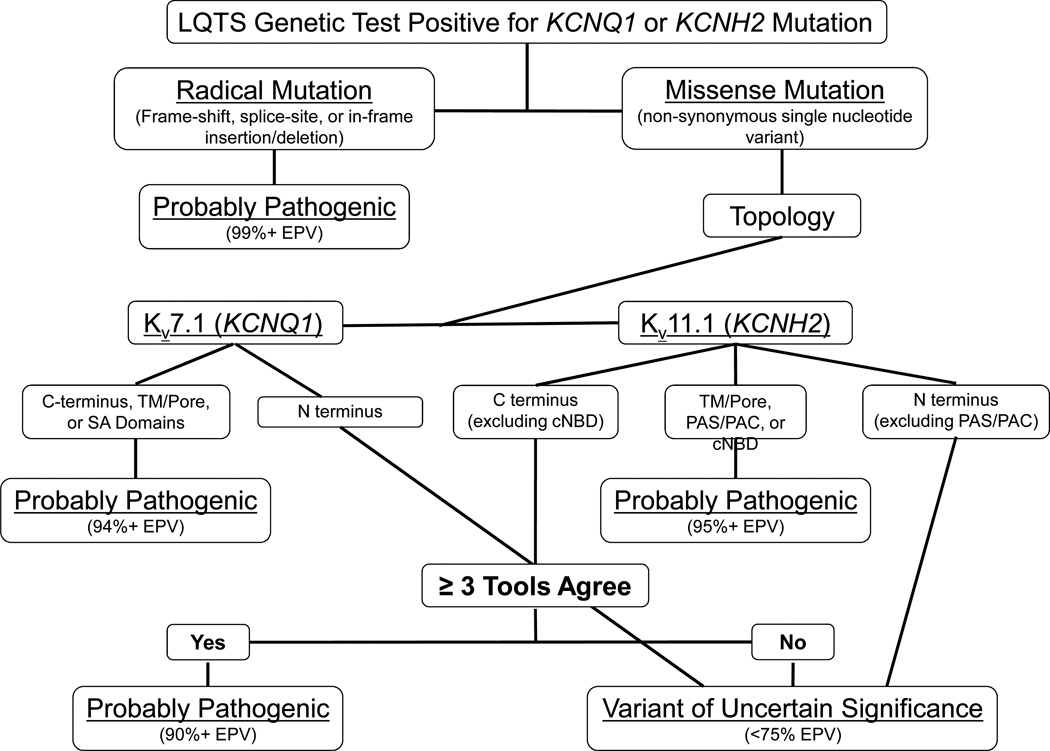

Given the expected reduction in both false positives/false negatives and the demonstrated ability to differentiate between case- and control-derived nSNVs associated with the synergistic use of all four in silico tools, we next sought to determined if region-specific EPVs could be improved when ≥ 3 tools predicted pathogenicity. Using this synergistic approach, the region-specific EPV for Kv11.1 C-terminus outside the cNBD surpassed 90% (CI, 53 to 98) when ≥ 3 tools were in agreement (Table 3). While protein topology-alone appears to be the primary determinant underlying a given nsSNVs probability of pathogenicity for most regions, this approach demonstrates the potential clinical utility of the synergistic use of in silico tools to reduce unwanted false positive/negative predictions and enhance the signal-to-noise ratio associated with the interpretation of nsSNVs localizing to problematic regions as outlined in Figure 3.

Table 3.

EPVs when 3 out of 4 prediction tools are in agreement

| Protein and location | Case % ≥ 3 Agree |

Control % ≥ 3 Agree |

≥ 3 tools agree EPV* (95% CI) |

< 3 tools agree EPV* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCNQ1 (Kv7.1) | (N = 86) | (N = 14) | ||

| N terminus | 0% | 0% | 71 (0–100) | 71 (0–98) |

| Transmembrane/linker/pore | 81% | 43% | 98 (93–99) | 87 (59–96) |

| C terminus (total) | 89% | 33% | 98 (93–100) | 71 (0–93) |

| SAD | 57% | 0% | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) |

| Outside SAD | 97% | 33% | 98 (92–100) | 0 (0–87) |

| KCNH2 (Kv11.1) | (N = 72) | (N = 27) | ||

| N terminus (total) | 40% | 23% | 79 (5–95) | 53 (0–83) |

| PAS/PAC domain | 60% | 0% | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) |

| Outside PAS/PAC | 20% | 23% | 15 (0–91) | 29 (0–78) |

| Transmembrane/linker/pore | 57% | 0% | 100 (48–100) | 100 (29–100) |

| C terminus (total) | 63% | 14% | 94 (74–99) | 43 (0–79) |

| cNBD | 67% | 0% | 99 (0–100) | 99 (0–100) |

| Outside cNBD | 60% | 14% | 91 (53–98) | 0 (0–68) |

EPV = (case rate – control rate)/case rate.

Figure 3.

Agreement of ≥ 3 in silico algorithms enhances the EPV-guided interpretation of KCNQ1 and KCNH2 genetic testing results. Depicted is a decision tree algorithm designed to guide the interpretation of LQTS genetic testing results for KCNQ1 and KCNH2. Radical mutations such as frame-shift, splice-site and in-frame insertions/deletions are probably pathogenic. Intrepretation of rare nsSNVs is largely based on the topological structure-function domain to which they localize in the Kv7.1 or Kv11.1 channel. Those rare, absent in control, missense mutations/nsSNVs that localize to the Kv7.1 or Kv11.1 transmembrane/pore domains, Kv7.1 subunit assembly domain (SAD), or Kv11.1 Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS), Per-Arnt-Sim-associated C-terminal (PAC), or cyclic nucleotide binding domain (cNBD) are probably pathogenic. Those C-terminal missense mutations/nsSNVs that localize outside the cNBD of Kv11.1 but are predicted by ≥ 3 in silico algorithms to affect protein structure/function are probably pathogenic when found in cases. Lastly, N-terminal missense mutations/nsSNVs in both channels and those C-terminal missense mutations/nsSNVs that localize outside either the SAD of Kv7.1 or the cNBD of Kv11.1 and are NOT predicted by at least 3 in silico algorithms to be pathogenic remain stuck in the ambiguous classification as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS).

Discussion

Non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (nsSNVs), commonly referred to as missense mutations, account for ~75% of the mutations encountered during LQTS genetic testing.14 Unfortunately, due to the existence of a background noise rate of ~3–4% among Caucasians and ~6–8% among non-Caucasians, comprised primarily of nsSNVs, the mere identification of an nsSNV within a major LQTS-susceptibility gene does not equal necessarily a LQTS-causative mutation.15 As a result, the interpretation of LQTS genetic test results must be viewed as probabilistic, rather than binary, except for certain well-established pathogenic mutations. When viewed appropriately in the context of the overall clinical picture, data from in vitro functional studies, when available, and established high-EPV criteria such as mutation type and location can greatly increase the clinician’s ability to accurately diagnose and effectively manage patients with suspected LQTS.

However, a number of cases fall within “gray” areas that are often difficult to interpret. While ideally heterologous expression studies would be utilized for every nsSNV, such studies remain fraught with issues that have precluded their use in the clinical setting including: 1) the speed at which they can be conducted, 2) the use of variable cellular expression systems, and 3) an inability to perfectly equate in vitro findings with in vivo human physiology. While patient-specific induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells represent an intriguing alternative to heterologous expression at present the high cost and time required to generate an iPS cell line is prohibitive.

Thus, recent attempts to enhance the interpretability of LQTS genetic testing results have focused on developing gene-, mutation type-, and region-specific criteria to assess the probability of pathogenicity derived from the systematic evaluation of all genetic variants present in LQTS-susceptibility genes across large case and control cohorts. While these efforts provided important insights into the type and location of high probability disease mutations, great caution still must exercised when interpreting novel nsSNVs in moderate- to low-EPV regions. Thus, there remains a pressing need to develop accurate, rapid, and cost-effective methodologies to identify high- and low- probability subsets of variants in moderate- to low-EPV regions.

If sufficiently predictive, the use of in silico algorithms represents an attractive methodology to enhance the classification of problematic nsSNVs given the speed and low overhead required to conduct such informatics-based analyses. Interestingly, multiple species alignments to assess species conservation, SIFT, and PolyPhen have been shown elsewhere to carry overall predictive values between 73%–81% for five genes associated with a variety of monogenic disorders, a predictive value similar to other tests currently employed in clinical practice (~80%).26 Furthermore, a multitude of studies have indicated that the classification of nsSNVs in genes associated with monogenic disorders can be enhanced greatly when a composite score of several prediction algorithms is employed.26–29

The fact that composite scores appear to be better at nsSNV evaluation exposes the shortcomings associated with the use of individual algorithms. For example, while PolyPhen and SIFT have been shown to have comparable true-positive rates (ranging from 69–73%), the false-positive rate for both algorithms has been shown to be unacceptably high (ranging from 20%–68%).30–33 Another glaring concern is the tendency of prediction algorithms to frequently disagree, as exemplified by the annotation of Venter’s genome where SIFT and PolyPhen disagreed on more nsSNV predictions than they agreed on.34

Our results for the in silico classification of KCNQ1 and KCNH2 nsSNVs largely echo the positive and negative elements identified in previous studies. For the most part, all four in silico algorithms scored rare nsSNVs originating in high probability clinical cases higher than those equally rare but control-derived nsSNVs. If taken at face value, the resulting EPVs (which over both genes ranged from 94–97%) for nsSNVs predicted to be potentially pathogenic in cases appear to be promising. However, caution must be exercised when interpreting the EPVs calculated for each algorithm independently.

While the overall EPV (93%, CI 90%–95%) for the K+ channels provides a fairly accurate estimate of the percentage of variants that are truly pathogenic, the UCSC sequence conservation and the Grantham matrix predicted that only 52% and 41% of case-derived nsSNVs are potentially pathogenic whereas in contrast, SIFT and PolyPhen predicted that as many as 28% and 46% of control-derived nsSNVs were potentially pathogenic. Thus, reliance solely on sequence conservation and the Grantham matrix may result in a higher false-negative rate, whereas reliance on tools such as SIFT and PolyPhen may carry a higher false-positive rate that undoubtedly influences the respective EPV values derived from these algorithms. As such, the use of these tools to classify nsSNVs across the entire KCNQ1 or KCNH2 gene is of limited value as they largely mimic the results derived already from simple topology-driven classification.

However, when the predictions of all four in silico algorithms are combined and used in concert with protein topology, the results appear promising for some channel domains where the topology-derived EPVs are suboptimal. Overall, 66% of case-derived nsSNVs compared to only 18.5% of control-derived nsSNVs had at least 3 of the 4 in silico tools predicting pathogenicity. While the use of the ≥ 3 composite score modestly enhanced or failed to enhance the EPVs of regions with an already high topology-derived EPV (> 95%), the use of the ≥ 3 composite score enhanced the EPVs in moderate- to low-EPV regions such as the Kv11.1 C-terminus outside the cNBD (from 56% to 91%).

Collectively, these data suggest that Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 protein topology serves as the best predictor of pathology, but for certain problematic areas, namely the Kv11.1 C-terminus, the use of a composite score that relies on several in silico algorithms may enable an “upgrade” from VUS to possible/probable disease-causing mutation for rare KCNH2 nsSNVs localizing to Kv11.1’s C-terminus where ≥ 3 commonly used in silico algorithms predict pathogenicity (Figure 3). Rare nsSNVs in the N-terminus of both Kv7.1 and Kv11.1 channels, except those localizing to Kv11.1’s PAS and PAC domains, remain stuck in the ambiguous classification of VUS and fully depend on co-segregation data or functional data to upgrade the variants probability of pathogenicity at this time.

Limitations

Several limitations are inherent to the nature of the case-control design used in this study. Not all rare nsSNVs identified in controls are likely to be totally devoid of functional significance. Since 12-lead ECGs and comprehensive cardiac examinations were not a prerequisite for those enrolled in the control population, it stands to reason that there may be disease-causative variants that were falsely considered to be background genetic noise. However, statistically, there is over 95% confidence that no more than 2 of the 1300+ controls could have had either LQT1 or LQT2. Further, if some of these control-derived nsSNVs are in fact pathogenic, the EPVs presented would be underestimated consequently, making this a conservative assumption. While 10 rare control nsSNVs were predicted to be potentially pathogenic by ≥ 3 algorithms, only one rare control variant in KCNH2 (C723R) was predicted to be pathogenic by all four tools. Thus, in terms of phylogenetic and physicochemical properties, KCNH2-C723R represents a rare control nsSNV with the greatest likelihood of being an LQTS-causative mutation.

Conversely, the rate of background genetic variation in the major LQTS genes dictates that roughly 1 in 30 mutations identified during genetic testing of a case will represent a false positive result. Thus, as many as 5 out of the 154 cases in this study could harbor a undiscovered primary disease-causative mutation besides the rare nsSNVs identified in KCNQ1 or KCNH2. Although a total of 9 rare case nsSNVs were predicted to be potentially benign by all four algorithms, at least half of these nsSNVs are still likely to be LQTS-causative mutations. In fact, 3 out of the 7 KCNH2 case nsSNVs (G584S, N588D, and G601S) predicted to be potentially benign by all 4 algorithms localize to a ~20 amino acid stretch in the hERG/Kv11.1 S5/Pore domain and have been previously shown to impart a loss-of-function electrophysiological phenotypes.35–37

This example clearly indicates that protein topology should supersede the readout of any in silico toolset when attempting to assign pathogenicity to a KCNQ1 or KCNH2 “variant of uncertain/unknown significance” (VUS). However, after the three aforementioned mutations in the S5/Pore of Kv11.1 and a VUS in the SAD of Kv7.1 (L619M), that localize to high EPV regions where no control nsSNVs were observed, are removed, the synergistic use of all four in silico tools suggests the remaining 5 rare variants (P73T-KCNQ1 and A78P-, I96V-, P297S-, and P1093L-KCNH2) have the greatest likelihood in terms of phylogenetic/physicochemical properties of representing a false positive result and thus require further scrutiny.

Second, despite the large amount of controls analyzed in the context of this study, the number of control nsSNVs on which to test the various in silico algorithms was low. As a result, some EPVs are likely to be influenced by the small number of both case and control nsSNVs locating to particular regions (e.g. the KCNQ1/Kv7.1 N-terminus). This limitation is also reflected in the wide confidence intervals around the EPVs. Third, because non-Caucasians are genetically more diverse, their overrepresentation in controls relative to cases again suggests the calculated EPVs are conservatively low.

Conclusions

Given the probabilistic rather than binary nature of genetic testing, accurate interpretation is by necessity a balancing act that requires the careful consideration of a number of factors. For LQTS genetic testing, the clinical utility of individual in silico phenotype prediction algorithms alone as measures of KCNQ1 and KCNH2 nsSNVs pathogenicity is limited. Although there are impressive statistical differences between case-derived and control-derived nsSNVs with each of these metrics, their clinical utility in isolation remains limited. In fact, if used in isolation, these tools could mislead the ordering physician.

To be sure, the next novel, rare nsSNV should not have its status upgraded from a VUS to a LQTS-causative mutation simply because the variant involved a 100% conserved residue, produced a Grantham value > 100, or has a SIFT/PolyPhen-prediction of “damaging”. Importantly, however, the development of future prediction tools that rely on the use of multiple independent phylogenetic and or physicochemical algorithms may hold promise as the synergistic use of multiple existing tools enhances the classification of nsSNVs (missense mutations) within KCNH2/Kv11.1’s C-terminus, outside the cNBD, where the topology-based probability of pathogenicity is suboptimal.

Supplementary Material

Loss-of-function mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNH2 are responsible for type 1 and type 2 long QT syndrome (LQTS), respectively. While LQT1 and LQT2 account for an estimated 65% of all LQTS cases, the existence of a background noise rate, consisting of primarily non-synonymous single nucleotide variants (nsSNVs), that ranges from ~3% to ~8% depending on ethnicity complicates the interpretation of LQTS genetic testing results. As such, the LQTS genetic testing is best viewed as probabilistic rather than binary in nature and results most accurately interpreted in the context of the overall clinical picture and established criteria, such as protein topology, used to assess the probability of pathogenicity. In an effort to enhance the classification of nsSNVs that localize to the difficult to interpret regions of the KCNQ1/Kv7.1 and KCNH2/Kv11.1 channels, we assessed the ability of 4 commonly used in silico tools to differentiate between nsSNVs identified in LQTS cases and ostensibly healthy controls. Using estimated predictive values (EPVs) derived from these data, we demonstrate that the clinical utility of each of these in silico phenotype prediction tools in isolation is limited, owing to either unacceptably high false-positive or false-negative rates. Importantly, we also demonstrate that the synergistic use of multiple phylogenetic and or physicochemical algorithms is capable of enhancing the classification of nsSNVs that localize to regions, namely the KCNH2/Kv11.1 C-terminal region outside the cyclic nucleotide binding domain (cNBD), where the topology-based probability of pathogenicity is suboptimal.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the Windland Smith Rice Sudden Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program (to M.J.A.). J.R.G is supported by a NIH/NHLBI NRSA Ruth L. Kirschstein individual pre-doctoral MD/PhD fellowship (F30-HL106993).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: MJA is a consultant for Transgenomic. Intellectual property derived from MJA’s research program resulted in license agreements in 2004 between Mayo Clinic Health Solutions (formerly Mayo Medical Ventures) and PGxHealth (formerly Genaissance Pharmaceuticals and now Transgenomic).

References

- 1.Moss AJ. Long qt syndrome. JAMA. 2003;289:2041–2044. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy KW, Lehmann MH, Priori S, Robinson JL, et al. Spectrum of mutations in long-qt syndrome genes. Kvlqt1, herg, scn5a, kcne1, and kcne2. Circulation. 2000;102:1178–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Compendium of cardiac channel mutations in 541 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long qt syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz PJ, Priori SG, Spazzolini C, Moss AJ, Vincent GM, Napolitano C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in the long-qt syndrome: Gene-specific triggers for life-threatening arrhythmias. Circulation. 2001;103:89–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Napolitano C, Bloise R, Priori SG. Gene-specific therapy for inherited arrhythmogenic diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giudicessi JR, Ackerman MJ. Potassium-channel mutations and cardiac arrhythmias-diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:319–332. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zareba W, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, Vincent GM, Robinson JL, Priori SG, et al. Influence of genotype on the clinical course of the long-qt syndrome. International long-qt syndrome registry research group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:960–965. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans JP, Skrzynia C, Burke W. The complexities of predictive genetic testing. BMJ. 2001;322:1052–1056. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7293.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter DJ, Khoury MJ, Drazen JM. Letting the genome out of the bottle--will we get our wish? N Engl J Med. 2008;358:105–107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0708162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Schwartz PJ. Low penetrance in the long-qt syndrome: Clinical impact. Circulation. 1999;99:529–533. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amin AS, Giudicessi JR, Tijsen AJ, Spanjaart AM, Reckman YJ, Klemens CA, et al. Variants in the 3' untranslated region of the kcnq1-encoded kv7.1 potassium channel modify disease severity in patients with type 1 long qt syndrome in an allele-specific manner. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:714–723. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ackerman MJ, Tester DJ, Jones GS, Will ML, Burrow CR, Curran ME. Ethnic differences in cardiac potassium channel variants: Implications for genetic susceptibility to sudden cardiac death and genetic testing for congenital long qt syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1479–1487. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackerman MJ, Splawski I, Makielski JC, Tester DJ, Will ML, Timothy KW, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of cardiac sodium channel variants among black, white, asian, and hispanic individuals: Implications for arrhythmogenic susceptibility and brugada/long qt syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, Carr JL, Harris-Kerr C, Pollevick GD, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of mutations from the first 2,500 consecutive unrelated patients referred for the familion long qt syndrome genetic test. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapa S, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, Harris-Kerr C, Pungliya MS, Alders M, et al. Genetic testing for long-qt syndrome: Distinguishing pathogenic mutations from benign variants. Circulation. 2009;120:1752–1760. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.863076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson HA, Accili EA. Evolutionary analyses of kcnq1 and herg voltage-gated potassium channel sequences reveal location-specific susceptibility and augmented chemical severities of arrhythmogenic mutations. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jons C, Moss AJ, Lopes CM, McNitt S, Zareba W, Goldenberg I, et al. Mutations in conserved amino acids in the kcnq1 channel and risk of cardiac events in type-1 long-qt syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:859–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz PJ, Crotti L. Qtc behavior during exercise and genetic testing for the long-qt syndrome. Circulation. 2011;124:2181–2184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.062182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Junker VL, Apweiler R, Bairoch A. Representation of functional information in the swiss-prot data bank. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:1066–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.12.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, Lehmann MH, Keating MT. Genomic structure of three long qt syndrome genes: Kvlqt1, herg, and kcne1. Genomics. 1998;51:86–97. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neyroud N, Richard P, Vignier N, Donger C, Denjoy I, Demay L, et al. Genomic organization of the kcnq1 k+ channel gene and identification of c-terminal mutations in the long-qt syndrome. Circ Res. 1999;84:290–297. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, et al. The human genome browser at ucsc. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the sift algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 1974;185:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous snps: Server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–3900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan PA, Duraisamy S, Miller PJ, Newell JA, McBride C, Bond JP, et al. Interpreting missense variants: Comparing computational methods in human disease genes cdkn2a, mlh1, msh2, mecp2, and tyrosinase (tyr) Hum Mutat. 2007;28:683–693. doi: 10.1002/humu.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mort M, Evani US, Krishnan VG, Kamati KK, Baenziger PH, Bagchi A, et al. In silico functional profiling of human disease-associated and polymorphic amino acid substitutions. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:335–346. doi: 10.1002/humu.21192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Perez A, Lopez-Bigas N. Improving the assessment of the outcome of nonsynonymous snvs with a consensus deleteriousness score, condel. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stead LF, Wood IC, Westhead DR. Kvsnp: Accurately predicting the effect of genetic variants in voltage-gated potassium channels. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2181–2186. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunyaev S, Ramensky V, Bork P. Towards a structural basis of human non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms. Trends Genet. 2000;16:198–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)01988-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He X, Zhang J. Toward a molecular understanding of pleiotropy. Genetics. 2006;173:1885–1891. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.060269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flanagan SE, Patch AM, Ellard S. Using sift and polyphen to predict loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:533–537. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hicks S, Wheeler DA, Plon SE, Kimmel M. Prediction of missense mutation functionality depends on both the algorithm and sequence alignment employed. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:661–668. doi: 10.1002/humu.21490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gr.092619.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cordeiro JM, Brugada R, Wu YS, Hong K, Dumaine R. Modulation of i(kr) inactivation by mutation n588k in kcnh2: A link to arrhythmogenesis in short qt syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:498–509. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delisle BP, Slind JK, Kilby JA, Anderson CL, Anson BD, Balijepalli RC, et al. Intragenic suppression of trafficking-defective kcnh2 channels associated with long qt syndrome. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:233–240. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao JT, Hill AP, Varghese A, Cooper AA, Swan H, Laitinen-Forsblom PJ, et al. Not all herg pore domain mutations have a severe phenotype: G584s has an inactivation gating defect with mild phenotype compared to g572s, which has a dominant negative trafficking defect and a severe phenotype. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:923–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.