Short abstract

Strain is an essential metric in tissue mechanics. Strains and strain distributions during functional loads can help identify damaged and pathologic regions as well as quantify functional compromise. Noninvasive strain measurement in vivo is difficult to perform. The goal of this in vitro study is to determine the efficacy of digital image correlation (DIC) methods to measure strain in B-mode ultrasound images. The Achilles tendons of eight male Wistar rats were removed and mechanically cycled between 0 and 1% strain. Three cine video images were captured for each specimen: (1) optical video for manual tracking of optical markers; (2) optical video for DIC tracking of optical surface markers; and (3) ultrasound video for DIC tracking of image texture within the tissue. All three imaging modalities were similarly able to measure tendon strain during cyclic testing. Manual/ImageJ-based strain values linearly correlated with DIC (optical marker)-based strain values for all eight tendons with a slope of 0.970. DIC (optical marker)-based strain values linearly correlated with DIC (ultrasound texture)-based strain values for all eight tendons with a slope of 1.003. Strain measurement using DIC was as accurate as manual image tracking methods, and DIC tracking was equally accurate when tracking ultrasound texture as when tracking optical markers. This study supports the use of DIC to calculate strains directly from the texture present in standard B-mode ultrasound images and supports the use of DIC for in vivo strain measurement using ultrasound images without additional markers, either artificially placed (for optical tracking) or anatomically in view (i.e., bony landmarks and/or muscle-tendon junctions).

Introduction

The response of musculoskeletal tissues such as ligaments and tendons to loading characterizes the tissue and elucidates its mechanical environment. Such data are essential to advance musculoskeletal tissue engineering, to gain insight into injury mechanisms, and to design and evaluate treatment options that optimize healing. Strain behavior is one way to evaluate tissue such as rotator cuff tendons [1]; not only can altered strain behavior identify abnormal (i.e., partially torn) regions [2], but it can also indicate regions susceptible to tear propagation [3,4].

The importance of strain behavior in pathologies such as tears of rotator cuff tendons has led to a number of ex vivo investigations; many of these utilize optical strain tracking methods using surface markers [1,4–6]. Others have used invasive methods such as intra-operative transducer implantation [7].

Image-based strain measurements hold promise for measuring strains in vivo, and thus transitioning more easily to clinical applications. A digital image pixel tracking algorithm digital image correlation (DIC), originally developed for displacement field evaluation of optically captured images, has become a popular method for evaluating strain [8–11]. DIC has been used in the past to study strain in biological soft tissues such as sheep bone callus [12], human tympanic membrane [13] and stapedial tendon [14], bovine cornea [15], mouse carotid arteries [16], and a human soft tissue phantom [17]. As an optical registration algorithm, DIC enables noncontact measurement of strain on material surfaces. Strain can be tracked using features inherent in the tissue [18]; however, this can be technically challenging in soft tissues because of the uniform white appearance of the collagen fibers in normal light [19], and tracking thus often requires the use of optical markers [20]. Polarized light imaging has been used to generate texture on tendons to allow DIC strain measurement [21].

Ultrasound is commonly used to image tissues in the body, including musculoskeletal tissues. Researchers have used landmarks such as bony markers to measure the deformation of such tissues to estimate strain response to load [22–25]; however, tracking of the texture of the ultrasound image itself would allow more freedom in locations as well as the ability to compare relative strain distributions in a tissue. Such feature tracking is reported for in vivo cardiac ultrasound [26,27], but not tendon tissue.

The goal of this study is to demonstrate the efficacy of using DIC to calculate strains directly from the texture present in clinical B-mode ultrasound images by comparing strains measured using this technique with strains measured using optical surface markers (using DIC and manual tracking methods).

Methods

Animal Preparation.

This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee. Eight skeletally mature male Wistar rats (weight 275 − 299 g) were used in this study. Rats were anesthetized with isoflourane immediately prior to euthanasia by overdose injection of sodium-pentobarbital (150 mg/kg). Rats were stored at −80°C until time of testing. Achilles tendons were dissected and surrounding tissue excised with care to keep the calcaneal insertion site intact. Tendons were kept hydrated using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at all times during dissection.

Mechanical Testing.

Tendons were tested in a custom-designed load frame that held and loaded tendons along the longitudinal axis of the tissue. The calcaneus was trimmed and press-fit into a custom bone grip. The soft tissue end was fixed with adhesive (super glue gel; Ace Hardware Corporation, Oak Brook, Illinois) to strips of Tyvek (McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, Illinois), which were held between two plates of the soft-tissue grip. Tendons were immersed in a PBS bath during testing to prevent dehydration and facilitate ultrasound wave propagation from transducer to tissue. Graphite-impregnated silicone markers were placed on the surface of the tendon to serve as optical markers for strain measurement, with one marker on the calcaneal insertion site and another at the soft tissue grip for overall displacement measurement.

Mechanical testing was performed at room temperature. A preload of 0.1 N was applied to obtain a uniform zero point [28], and tendon length was measured using digital calipers. Tendons were then preconditioned (20 cycles at 0.5 Hz) to 0.5%. Following a 10-min rest period (to allow for viscoelastic recovery), cyclic testing between 0 and 1% strain was performed. During testing, force and displacement information from the test frame was recorded while a camera (Sony 3CCD color video camera; Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) simultaneously recorded the marker movements. This process was repeated twice (with a 10-min rest between tests to allow for viscoelastic recovery) before repeating the procedure, while substituting an ultrasound transducer (12L-RS linear probe, connected to GE Logiq e portable ultrasound system; General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) for the camera during the two subsequent tests. Cyclic testing was, therefore, performed four times to accommodate strain calculation using both optical video and dynamic ultrasound.

ImageJ Tracking.

ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) was used to measure the distance between markers in the first recorded frame (l 0) and in each subsequent frame during loading (l) from the optical images by converting the images to black and white, determining the centroid coordinates of the markers, and calculating the length of the vector connecting the centroids. The optical strain for the tendon substance was computed as:

| 1 |

Digital Image Correlation Tracking of Optical Images.

A custom MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts) algorithm utilizing the DIC method measured the initial location of the silicone markers and tracked the location of the markers in subsequent frames by minimizing the feature difference of selected data sets describing the pixel intensity of a “disk” of pixels (radius = 5 pixels, centered around the initial selected pixel) in different frames using the relationship:

| 2 |

Supposing that arrays A and B are corresponding subsets in two digital images, and coordinates and are related by the deformation that occurs between two images, then , are the individual intensity of point and in each subset. Assuming small subsets from the intensity pattern stored in array B are related to small subsets of the same size in array A by a homogeneous linear mapping, the correlation is the square root of the sum of the squared intensity difference between corresponding pixels. DIC relates the corresponding pixels and by optimizing (minimizing) the correlation value. The distance between points in each frame (l) was automatically calculated using the pixel coordinates to measure, and strain was calculated using Eq. (1).

Digital Image Correlation Tracking of Ultrasound Images.

An algorithm utilizing the DIC method measured and tracked the distance between two pixels selected at each end of the tendon of the initial frame. The pixels were selected to correspond to the location of the silicone markers in the optical videos. DIC displacement and strain measurements were calculated by the method previously described.

Results

All imaging modalities were able to measure tendon strain during cyclic testing. Strain calculated by methods using tracked surface markers (both with ImageJ and DIC) from a representative specimen is plotted in Fig. 1. The correlation between ImageJ-based and DIC (optical marker)-based strain values for all eight tendons with a 95% confidence interval is shown in Fig. 2; the mean intercept and slope of the linear correlation were 0.000 and 0.970, respectively. Strain values calculated using the same markers were not significantly different between DIC and manual tracking methods (p = 0.9113).

Fig. 1.

Optical tracking results using ImageJ (open squares) and DIC (open circles). There is a strong correlation between values computed using manual (ImageJ) and DIC tracking of optical videos (R 2 value of 0.955). Such a strong correlation demonstrates the ability of DIC to track and calculate strain measurements on optical videos of tissues as accurately as manual methods. These findings were similar in the eight tendons that were tracked; correlation shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Linear correlation between strain values calculated manually (using ImageJ) and using DIC tracking methods, plotted with a 95% confidence interval. A strong correlation is shown, with mean intercept and slope of the eight tendons of 0.000 and 0.970, respectively.

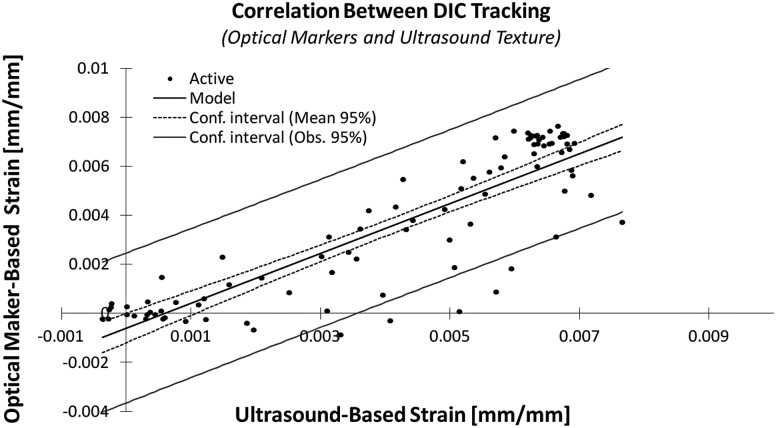

Strain calculated by methods using DIC, utilizing surface markers and ultrasound texture, from a representative specimen is plotted in Fig. 3. The correlation between DIC (optical marker)-based and DIC (ultrasound texture)-based strain values for all eight tendons with a 95% confidence interval is shown in Fig. 4; the mean intercept and slope of the linear correlation were 0.000 and 1.003, respectively. A summary of the results of both correlations with 95% confidence intervals can be found in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

DIC tracking results using optical video with markers and ultrasound videos demonstrating correlation (R 2 value of 0.803). These findings were similar in all tested tendons. Such strong correlation demonstrates the ability of DIC to track and calculate strain measurements on ultrasound videos (using only tissue texture) as accurately as when using optical marker methods. Linear correlation is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Linear correlation between strain values calculated by DIC tracking of tendons using optical and ultrasound videos, plotted. The mean intercept and slope of the six tendons analyzed were 0.000 and 1.003, respectively.

Table 1.

Mean statistical parameters obtained in confidence intervals (95%) from strain result comparisons of manual (ImageJ) vs. DIC using optical markers, as well as DIC using optical markers vs. DIC using ultrasound images

| Confidence intervals (95%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Means/averages | Optical: ImageJ vs. DIC | DIC: Optical vs. ultrasound |

| Offset error/intercept | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Slope | 0.970 | 1.003 |

| Range of slope | 0.051 | 0.270 |

| R 2 | 0.932 | 0.700 |

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate in a uniformly loaded tendon that strain values calculated using DIC methods are not significantly different than those calculated using standard manual tracking methods when tracking the same surface markers (p = 0.9113), and that DIC tracking is as accurate when tracking ultrasound texture from longitudinal sections as when tracking optical surface markers (R 2 = 0.803), thus demonstrating the efficacy of using DIC to calculate strains directly from the texture present in clinical B-mode ultrasound images of tendons or ligaments.

Outside of cardiac applications, many in vivo ultrasound strain estimates have relied on measuring distances between bony markers or other landmarks [22–25]. Other in vitro studies have used DIC methods in conjunction with fluorescent-labeled cells [29] or texture from static magnetoresistance magnetic resonance (MR) images (un-deformed and deformed) to measure tissue strain [30]. Fluorescent cell tracking is not available in the clinical setting, and MR as an imaging modality has several inherent limitations when compared to ultrasound including increased expense, decreased portability, and lengthy image-acquisition time.

This study only examined controlled, uniform deformation in an in vitro setting. Full validation of the use of DIC in clinical applications will require tracking strain in the more difficult in vivo environment, including images captured through other tissues during nonuniform deformation.

Tracking strain from ultrasound image texture allows for direct in vivo measurement of strain using ultrasound images without requiring additional markers, either artificially placed (for optical tracking) or anatomically in view (i.e. bony landmarks and/or muscle-tendon junctions), for calculations. Thus, on-tissue strain, and potentially strain in different regions, can be measured. These strain measurements are particularly valuable in the assessment of different tendon pathologies such as rotator cuff tears and tendinopathies in various locations, leading to better understanding and management of such injuries.

Acknowledgment

Support by the National Science Foundation (award 0553016) and National Institutes of Health (award R21 EB 008548) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Ron McCabe for his technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Sarah Duenwald-Kuehl, Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53705.

Hirohito Kobayashi, Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53705.

Mon-Ju Wu, Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, Materials Science Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53705.

Ray Vanderby, Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Materials Science Program, Room 5059, 1111 Highland Ave., University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53705, e-mail: vanderby@ortho.wisc.edu.

References

- [1]. Mazzocca, A. D. , Rincon, L. M. , O’Connor, R. W. , Obopilwe, E. , Andersen, M. , Geaney, L. , and Arciero, R. A. , 2008, “Intra-Articular Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears,”Am. J. Sports Med., 36(1), pp. 110–116. 10.1177/0363546507307502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Reilly, P. , Amis, A. A. , Wallace, A. L. , and Emery, R. J. H. , 2003, “Supraspinatus Tears: Propagation and Strain Alteration,” J. Shoulder Elbow Surg., 12(2), pp. 134–138. 10.1067/mse.2003.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Matava, M. J. , Purcell, D. B. , and Rudzki, J. R. , 2005, “Partial-Thickness Rotator Cuff Tears,” Am. J. Sports Med., 33(9), pp. 1405–1417. 10.1177/0363546505280213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Andarawis-Puri, N. , Ricchetti, E. T. , and Soslowsky, L. J. , 2009, “Rotator Cuff Tendon Strain Correlates With Tear Propagation,” J. Biomech., 42(2), pp. 158–163. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Huang, C.-Y. , Wang, V. M. , Pawluk, R. J. , Bucchieri, J. S. , Levine, W. N. , Bigliani, L. U. , Mow, V. C. , and Flatow, E. L. , 2005, “Inhomogeneous Mechanical Behavior of the Human Supraspinatus Tendon Under Uniaxial Loading,” J. Orthop. Res., 23(4), pp. 924–930. 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Itoi, E. , Berglund, L. J. , Grabowski, J. J. , Schultz, F. M. , Growney, E. S. , Morrey, B. F. , and An, K.-N. , 1995, “Tensile Properties of the Supraspinatus Tendon,” J. Orthop. Res., 13(4), pp. 578–584. 10.1002/(ISSN)1554-527X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Reilly, P. , Bull, A. M. J. , Amis, A. S. , Wallace, A. L. , Richards, A. , Hill, A. M. , and Emery, R. J. H. , 2004, “Passive Tension and Gap Formation of Rotator Cuff Repairs,” J. Shoulder Elbow Surg., 13(6), pp. 664–667. 10.1016/j.jse.2004.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Sutton, M. , Wolters, W. , Peters, W. , Ranson, W. , and McNeill, S. , 1983, “Determination of Displacements Using an Improved Digital Correlation Method,” Image Vision Comput., 1(3), pp. 133–139. 10.1016/0262-8856(83)90064-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Sutton, M. , Mingqi, C. , Peters, W. , Chao, Y. , and McNeill, S. , 1986, “Application of an Optimized Digital Correlation Method to Planar Deformation Analysis,” Image Vision Comput., 4(3), pp. 143–150. 10.1016/0262-8856(86)90057-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Siegel, S. , and Castellan, N. J., Jr. , 1988, Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Bruck, H. A. , McNeill, S. R. , Sutton, M. A. , and Peters, W. H. , 1989, “Digital Image Correlation Using Newton-Raphson Method of Partial Differential Correction,” Exp. Mech., 29, pp. 261–267. 10.1007/BF02321405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Thompson, M. S. , Schell, H. , Lienau, J. , and Duda, G. N. , 2007, “Digital Image Correlation: A Technique for Determining Local Mechanical Conditions Within Early Bone Callus,” Med. Eng. Phys., 29(7), pp. 820–823. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2006.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Cheng, T. , Dai, C. , and Gan, R. Z. , 2006, “Viscoelastic Properties of Human Tympanic Membrane,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 35, pp. 305–314. 10.1007/s10439-006-9227-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Cheng, T. , and Gan, R. Z. , 2007, “Mechanical Properties of Stapedial Tendon in Human Middle Ear,” J. Biomech. Eng., 129(6), pp. 913–918. 10.1115/1.2800837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Boyce, B. L. , Grazier, J. M. , Jones, R. E. , and Nguyen, T. D. , 2008, “Full-Field Deformation of Bovine Cornea Under Constrained Inflation Conditions,” Biomaterials, 29(28), pp. 3896–3904. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Sutton, M. A. , Ke, X. , Lessner, S. M. , Goldbach, M. , Yost, M. , Zhao, F. , and Schreier, H. W. , 2008, “Strain Field Measurements on Mouse Carotid Arteries Using Microscopic Three-Dimensional Digital Image Correlation,” J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A, 84(1), pp. 178–190. 10.1002/(ISSN)1552-4965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Moerman, K. M. , Holt, C. A. , Evans, S. L. , and Simms, C. K. , 2009, “Digital Image Correlation and Finite Element Modelling as a Method to Determine Mechanical Properties of Human Soft Tissue In Vivo,” J. Biomech., 42(8), pp. 1150–1153. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Bay, B. K. , 1995, “Texture Correlation: A Method for the Measurement of Detailed Strain Distributions Within Trabecular Bone,” J. Orthop. Res., 13(2), pp. 258–267. 10.1002/(ISSN)1554-527X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Doehring, T. C. , Kahelin, M. , and Vesely, I. , 2009, “Direct Measurement of Nonuniform Large Deformations in Soft Tissues During Uniaxial Extension,” J. Biomech. Eng., 131(6), p. 061001. 10.1115/1.3116155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Guan, E. , Smilow, S. , Rafailovich, M. , and Sokolov, J. , 2004, “Determining the Mechanical Properties of Rat Skin With Digital Image Speckle Correlation,” Dermatology, 208(2), pp. 112–119. 10.1159/000076483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Komolafe, O. A. , and Doehring, T. C. , 2010, “Fascicle-Scale Loading and Failure Behavior of the Achilles Tendon,” J. Biomech. Eng., 132(2), p. 021004. 10.1115/1.4000696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Farron, J. , Varghese, T. , and Thelen, D. G. , 2009, “Measurement of Tendon Strain During Muscle Twitch Contractions Using Ultrasound Elastography,” IEEE Trans. Ultrason., Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, 56(1), pp. 27–35. 10.1109/TUFFC.2009.1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Maganaris, C. , 2005, “Validity of Procedures Involved in Ultrasound-Based Measurement of Human Plantarflexor Tendon Elongation on Contraction,” J. Biomech., 38(1), pp. 9–13. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Maganaris, C. , 2002, “Tensile Properties of In Vivo Human Tendinous Tissue,” J. Biomech., 35(8), pp. 1019–1027. 10.1016/S0021-9290(02)00047-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Onambélé, G. N. L. , Burgess, K. , and Pearson, S. J. , 2007, “Gender-Specific In Vivo Measurement of the Structural and Mechanical Properties of the Human Patellar Tendon,” J. Orthop. Res. 25(12), pp. 1635–1642. 10.1002/(ISSN)1554-527X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Stefani, L. , Toncelli, L. , Gianassi, M. , Manetti, P. , Di Tante, V. , Vono, M. R. C. , Moretti, A. , Cappelli, B. , Pedrizzetti, G. , and Galanti, G. , 2007, “Two-Dimensional Tracking and TDI Are Consistent Methods for Evaluating Myocardial Longitudinal Peak Strain in Left and Right Ventricle Basal Segments in Athletes,” Cardiovasc. Ultrasound, 5 (1) Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1476-7120-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Notomi, Y. , Lysyansky, P. , Setser, R. M. , Shiota, T. , Popović, Z. B. , Martin-Miklovic, M., G. , Weaver, J. A. , Oryszak, S. J. , Greenberg, N. L. , White, R. D. , and Thomas, J. D. , 2005, “Measurement of Ventricular Torsion by Two-Dimensional Ultrasound Speckle Tracking Imaging,” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 45(12), pp. 2034–2041. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Provenzano, P. , Lakes, R. , Keenan, T. , and Vanderby, R., Jr. , 2001, “Nonlinear Ligament Viscoelasticity,” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 29(10), pp. 908–914. 10.1114/1.1408926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Wang, C. C.-B. , Deng, J.-M. , Ateshian, G. A. , and Hung, C. T. , 2002, “An Automated Approach for Direct Measurement of Two-Dimensional Strain Distributions Within Articular Cartilage Under Unconfined Compression,” J. Biomech. Eng., 124(5), pp. 557–567. 10.1115/1.1503795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Gilchrist, C. L. , Xia, J. Q. , Setton, L. A. , and Hsu, E. W. , 2004, “High-Resolution Determination of Soft Tissue Deformations Using MRI and First-Order Texture Correlation,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, 23(5), pp. 546–553. 10.1109/TMI.2004.825616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]