Abstract

ErbB2, a receptor tyrosine kinase highly expressed in many tumors, is known to inhibit apoptotic signals. Overexpression of ErbB2 causes anoikis resistance that contributes to luminal filling in three-dimensional mammary epithelial acinar structures in vitro. Given that integrins and growth factor receptors are highly interdependent for function, we examined the role of integrin subunits in ErbB2-mediated survival signaling. Here, we show that MCF-10A cells overexpressing ErbB2 upregulate integrin α5 via the MAP-kinase pathway in three-dimensional acini and found elevated integrin α5 levels associated with ErbB2 status in human breast cancer. Integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance and for optimal ErbB2 signaling to the Mek-Erk-Bim axis as depletion of integrin α5 reverses anoikis resistance and Bim inhibition. Integrin α5 is required for full activation of ErbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation on Y877 and ErbB2 phosphorylation is associated with increased activity of Src in the absence of adhesion. Indeed, we show that blocking elevated Src activity during cell detachment reverses ErbB2-mediated survival and Bim repression. Thus, integrin α5 serves as a key mediator of Src and ErbB2-survival signaling in low adhesion states, which are necessary to block the pro-anoikis mediator Bim, and we suggest that this pathway represents a potential novel therapeutic target in ErbB2-positive tumors.

Key words: Integrin α5, ErbB2, Her2, Src, Bim, Anoikis, 3D culture, Epithelial, Cancer

Introduction

Cell to extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion has a central role for the structural organization of tissues of multicellular organisms. Adhesion-mediated regulation of cell survival contributes to maintenance of tissue homeostasis by allowing cells to remain in their correct tissue environment. Absence of survival signals from ECM can trigger apoptosis in a process referred to as anoikis (Frisch and Screaton, 2001). Tumor cells become anchorage-independent for growth and survival and most epithelial-derived cancer cells display substantial resistance to anoikis (Schwartz, 1997). This characteristic has important implications for metastasis because cells that survive after detachment from their primary site can travel through circulatory systems to secondary sites (Simpson et al., 2008). Studies using three-dimensional (3D) organotypic culture systems, which have been increasingly used to understand pathways regulating glandular morphogenesis and epithelial cancer development (Debnath and Brugge, 2005), have implicated anoikis resistance as an early event in cancer progression. Many early breast cancer lesions, such as ductal carcinoma in situ, are characterized by filling of the luminal space (Harris, 2004). Mechanisms that underly lumen formation have been examined by using MCF-10A cells, an immortalized human mammary epithelial cell line. These cells, when cultured on reconstituted basement membrane, undergo a series of morphogenic changes resulting in the formation of acinus-like structures that contain a single layer of polarized cells surrounding a hollow lumen (Muthuswamy et al., 2001). Clearance of centrally located cells in this model involves apoptosis, because these cells are not in direct contact with matrix, which suggests that anoikis is involved (Debnath et al., 2002). Indeed, we have shown that cell detachment at the single-cell level and apoptosis during lumen formation in 3D morphogenesis both require induction of the Bcl-2-family proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bim; and oncogenes that induce anoikis resistance and are capable of blocking or delaying lumen formation in 3D culture block Bim induction (Reginato et al., 2003; Reginato et al., 2005; Reginato and Muthuswamy, 2006). Recent studies have found that Bim is also required in the mouse mammary gland for apoptosis during lumen formation (Mailleux et al., 2007), which correlates with the in vitro 3D acinar morphogenesis culture system.

Inhibition of Bim expression in MCF-10A cells is coordinated by both integrin and EGF receptor (EGFR) regulation of Erk signaling, the latter of which depends on cell adhesion. Loss of integrin-receptor adhesion leads to downregulation of EGFR expression and signaling to the Mek-Erk pathway, which in turn leads to the induction of Bim (Reginato et al., 2003). Cells that overexpress EGFR are able to escape regulation from loss of integrin engagement. Additionally, EGFR overexpression allows cell survival from anoikis and inhibit Bim expression, suggesting that elevated levels of growth factor receptor can uncouple from integrin regulation. However, recent evidence suggests that integrin receptors are required for oncogenic phenotypes in vivo (Guo et al., 2006; White et al., 2004). Thus, it is not clear whether growth factor receptors expressed at high levels still require integrins in the absence of adhesion for correct survival signaling and anoikis resistance.

ErbB2 (also known as HER2, Neu) is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is overexpressed in 20% to 30% of invasive breast tumors and up to 85% of comedo-type ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), a premalignant stage of breast cancer (Hynes and Stern, 1994; Lohrisch and Piccart, 2001). A number of ErbB2 inhibitors, although initially effective in breast cancer patients, lose activity during prolonged treatment (Nahta et al., 2006) indicating the need for identification of additional therapeutic targets. We have previously shown that cells overexpressing ErbB2 can induce anoikis resistance in mammary epithelial cells (Reginato et al., 2003). In addition, activation of ErbB2 in 3D acini leads to an increase in proliferation and luminal filling (Muthuswamy et al., 2001). ErbB2 inhibition of luminal apoptosis during morphogenesis is associated with increased Erk activation and decreased Bim expression (Reginato et al., 2005). It remains unclear whether epithelial cells that overexpress ErbB2 still require integrins for anoikis resistance. Recently, it was shown that mice that express a dominant-negative form of integrin β4 can inhibit ErbB2-mediated mammary oncogenesis, suggesting that cancer cells that overexpress RTKs are dependent on integrin-β subunits for their growth and survival (Guo et al., 2006). However, the requirement of specific integrin subunits for ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance has not yet been addressed.

Here, we show that ErbB2-expressing breast cancers positively correlate with increased levels of integrin α5 and that ErbB2 requires integrin α5 for anoikis resistance. Integrin α5 is highly upregulated in ErbB2-overexpressing cells via the regulation of the Mek-Erk kinase pathway. Additionally, integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance both in 3D acini and in the soft-agar assay for colony formation. Reducing expression of integrin α5 in ErbB2-overexpressing cells leads to loss of Src hyperactivity in the absence of adhesion, decreased ErbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation on Y877 and decreased signaling to the Mek-Erk pathway allowing reversal of Bim inhibition. Elevation of integrin α5 in epithelial cells with low adhesion helps to activate and couple Src activity to RTKs, such as ErbB2, and allows survival from anoikis. Thus, our data indicate that tyrosine kinase receptors still require integrins for correct survival signaling under conditions of suboptimal matrix interaction.

Results

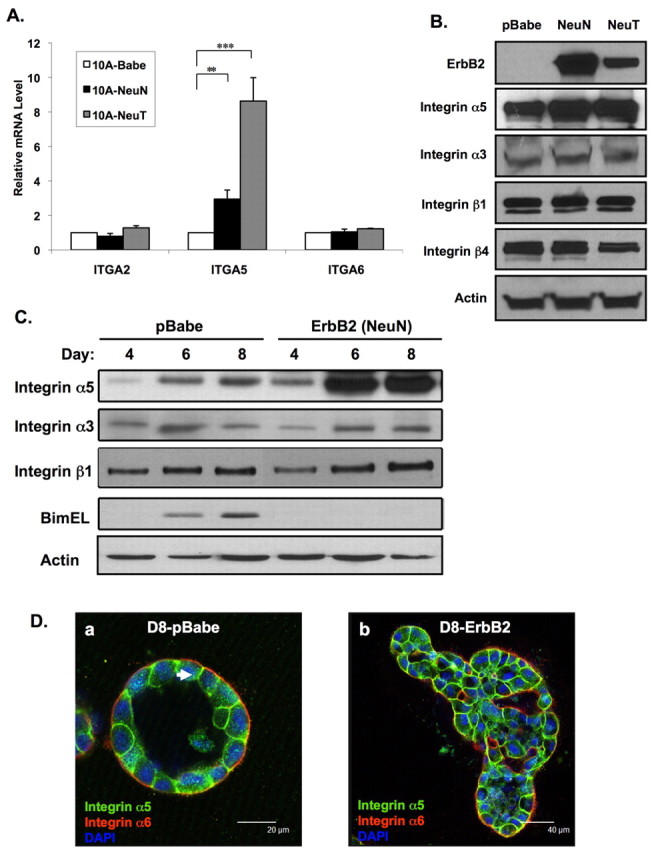

Integrin α5 expression is upregulated by ErbB2-expressing cells and is elevated in ErbB2-positive breast cancers

To determine whether ErbB2 regulates specific integrin subunits in human mammary epithelial cells we examined the RNA expression of a number of integrin subunits in MCF-10A cells that stably overexpress wild-type ErbB2 (pBabe-NeuN) compared with vector alone (pBabe). By using an RNase protection assay (RPA) integrin-probe set, we found a number of integrin subunits that are constitutively expressed in normal MCF-10A cells and in cells overexpressing ErbB2. MCF-10A cells that overexpress ErbB2 did not significantly alter RNA expression of most integrin subunits compared with control MCF-10A cells. By contrast, we found a substantial and specific upregulation of the integrin-α5 subunit in cells that overexpress ErbB2 (data not shown). We validated RPA results by using quantitative real-time (QRT) PCR and found that integrin-α5 mRNA was elevated threefold in ErbB2-overexpressing cells compared with parental MCF-10A cells (Fig. 1A). We did not detect changes in other integrin-α-subunit mRNA expression including integrins α2 and α6 by QRT-PCR. In addition, we also examined expression of these integrin subunits in MCF-10A cells that overexpress constitutively active ErbB2 (NeuT) and found an eightfold elevation of integrin-α5 mRNA but no change in the levels of integrins α2 or α6 when compared with control MCF-10A cells. Consistent with RNA expression, integrin α5 protein levels were increased twofold in ErbB2 (NeuN or NeuT) overexpressing cells compared with control cells (Fig. 1B) and analysis by flow cytometry showed a two- to threefold increased membrane localization of integrin α5 in ErbB2-overexpressing cells (supplementary material Fig. S1). We found no increase in protein expression of integrin α3, integrin β4 or integrin β1 in ErbB2-overexpressing cells compared with control cells (Fig. 1B) and also no change in surface expression of integrin α6 or integrin β1 (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Integrin α5 expression is upregulated in ErbB2-overexpressing cells. (A) RNA was prepared from attached MCF-10A cells infected with retrovirus of empty vector (pBabe), wild-type ErbB2 (NeuN) or constitutively active ErbB2 (NeuT). qRT-PCR was used to compare mRNA levels for integrins α2, α5 and α6. Values were normalized to cyclophilin expression and represented as mean ± s.e.m of fold change for at least three individual experiments (**P<0.05, ***P<0.01 by Students t-test). (B) Lysates from MCF-10A cells expressing pBabe empty vector, NeuN or NeuT were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. pBabe or NeuN cells were placed in morphogenesis assays and (C) cell lysates collected at indicated times and protein analyzed by immunoblotting or (D) cells were fixed and immunostained at day 8 with antibodies for anti-integrin α5 (green) and integrin α6 (red), and nuclei counterstained with DAPI (blue).

To determine whether ErbB2 overexpression in MCF-10A cells that undergo 3D morphogenesis also increased the expression of integrin α5, we analyzed levels of several integrin subunits during morphogenesis. Cells stably overexpressing wild-type ErbB2 (NeuN) had levels three- to fourfold higher of integrin α5 at day 6 and day 8 when compared with control cells (Fig. 1C). Expression of other integrin subunits was not increased – including integrin α3 or integrin β1 – during morphogenesis. We have previously shown that normal cells that undergo morphogenesis in 3D culture induce expression of Bim at about day 8, and that Bim is required for clearing of the central lumen (Reginato et al., 2005). Bim inhibition is associated with luminal filling and decreased apoptosis in cells that overexpress oncogenes, including ErbB2, during morphogenesis (Reginato et al., 2005) (Fig. 1C). We also examined the localization of integrin α5 in normal and ErbB2-expressing acini structures by immunostaining. As previously shown (Muthuswamy et al., 2001), integrin α6 is localized primarily at the basal surface, with weak staining at the lateral surface of normal MCF-10A acini (Fig. 1D). However, unlike integrin α6, integrin α5 is localized predominantly on the lateral surface of normal acini (Fig. 1D, arrowed). In ErbB2-expressing acini, organization and polarity of acini structures are disrupted (see Muthuswamy et al., 2001; Aranda et al., 2006) and localization of integrin α5 is no longer predominantly at the lateral surface.

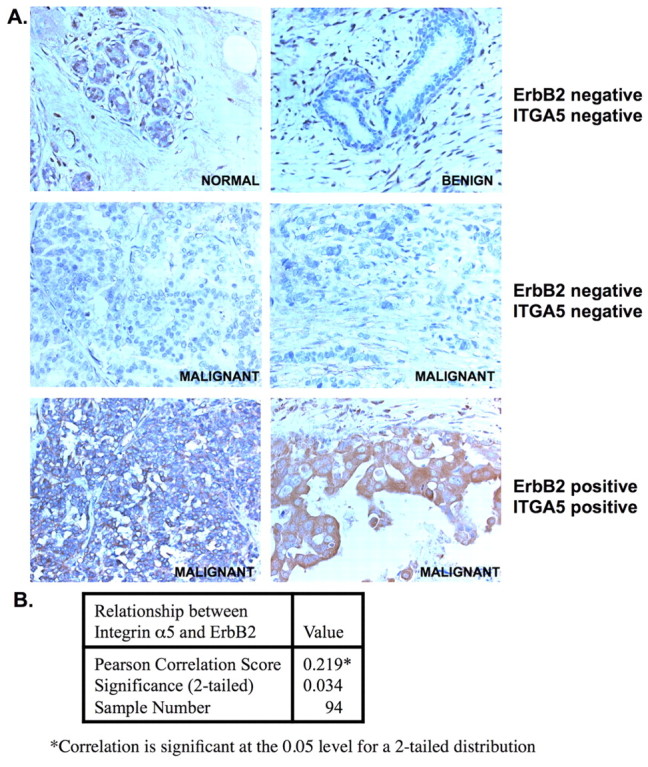

To determine whether expression of integrin α5 correlates with ErbB2-positive breast-cancer tissue, we performed immunohistochemical staining on ErbB2-positive breast-cancer tissue by using breast-cancer-tissue arrays. We found very little staining of integrin α5 in normal breast epithelial cells, benign breast tissue as well as ErbB2-negative malignant tissue (Fig. 2A). However, we found 68% of ErbB2 positive cancer contained elevated integrin α5 staining (Fig. 2A, supplementary material Table S1). Statistical analysis showed that there is a significant and positive association between expression of integrin α5 and that of ErbB2 (Pearson's correlation = 0.219, two-tailed, P<0.05) (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that ErbB2 upregulates RNA and protein levels of integrin α5 in vitro and that increased expression of integrin α5 is associated with ErbB2-positive breast cancers.

Fig. 2.

Integrin α5 is elevated in ErbB2 positive breast cancers. (A) Normal and tumor tissue from human breast tissue microarrays were immunohistochemically stained with an anti-integrin α5 antibody (brown) and counterstained with hematoxylin (blue) and the expression of integrin α5 was analyzed. Representative images from six tissue sections are shown (magnification 20×). (B) Immunohistochemistry was used to determine integrin α5 expression, which was classified as described in the Materials and Methods section. From 94 cases, 64 out of 70 ErbB2-positive cases were also found to stain positive for integrin α5. A two-tailed Pearson's correlation test was used to analyze the relationship between integrin α5 expression and ErbB2 status. Results were considered to be significant at P<0.05.

Integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated inhibition of luminal apoptosis and anoikis resistance

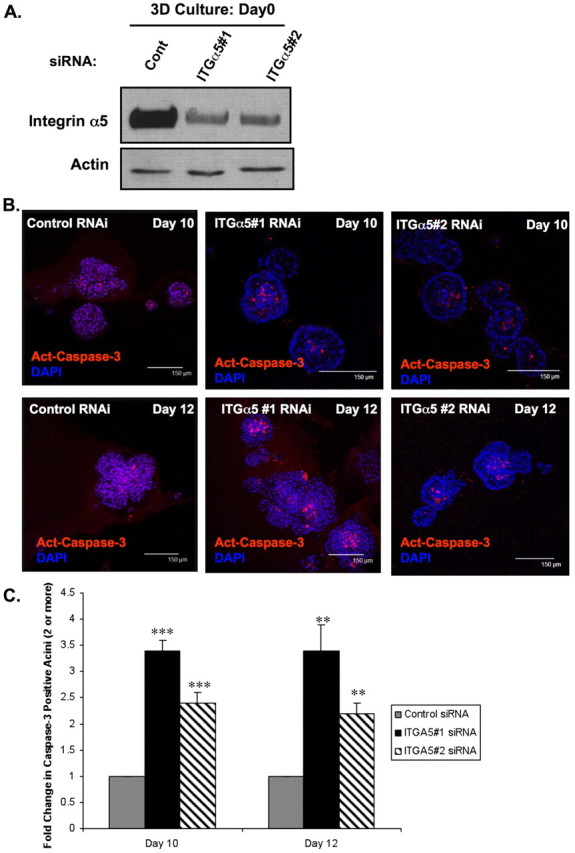

Upregulation of integrin α5 by ErbB2 suggests that integrin α5 contributes to ErbB2-oncogenic phenotypes including anchorage-independence. We have previously shown a crucial interdependence between integrins and RTKs in the regulation of normal epithelial cell survival during detachment from matrix signals (Reginato et al., 2003). Thus, we hypothesized that oncogenes, such as ErbB2, that inhibit anoikis may co-opt specific ECM-related molecules that contribute to survival in absence of adhesion. To determine whether integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-anoikis resistance, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to reduce the expression of integrin α5. ErbB2 cells transfected with two separate small interfering (si) RNA oligonucleotides that are homologous to the nucleotide sequence of integrin α5, but not to control siRNA, showed substantially reduced expression of integrin α5 at day 0 in morphogenesis assay (Fig. 3A). Expression of other integrin subunits, such as integrin α3 or integrin β1, was not affected by the transfection of integrin α5 siRNA (data not shown). Luminal apoptosis was measured by determining the percent of acini with centrally localized cleaved caspase-3 staining. Reducing integrin α5 expression significantly (P<0.05) increased luminal apoptosis in ErbB2-expressing acini as measured by percentage of caspase-3 positive acini (Fig. 3B) compared with cells transfected with control siRNA. At days 10 and 12 of morphogenesis, acini derived from cells transfected with integrin α5 siRNA contained two- or threefold higher centrally localized, activated caspase-3-positive staining than those transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 3C). In addition to control siRNA, we also found no effect of reducing expression of integrin α3 on luminal apoptosis (data not shown). Thus, integrin α5 expression is specifically required for ErbB2-mediated inhibition of luminal apoptosis.

Fig. 3.

Integrin α5 expression is required for ErbB2-mediated inhibition of luminal apoptosis during morphogenesis. (A) At 48 hours after initial transfection with siRNA oligonucleotides against integrin α5 or luciferase control, MCF-10A-NeuN cells were placed in 3D morphogenesis assay for the indicated times followed by cell lysis and immunoblotting using indicated antibodies. (B) Transfected NeuN cells were cultured in 3D morphogenesis assay for 10 or 12 days, and then fixed and stained with the activated (cleaved) caspase-3 antibody (red, apoptosis marker). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (C) Acini positive for activated (cleaved) caspase-3 were counted and the fold change in caspase-3 positivity per experiment was plotted. Acini containing two or more activated caspase-3 cells were scored as positive (n=3, >100 acini/experiment; mean ± s.e.m. of the fold change. **P<0.05, ***P<0.01 by Students t-test).

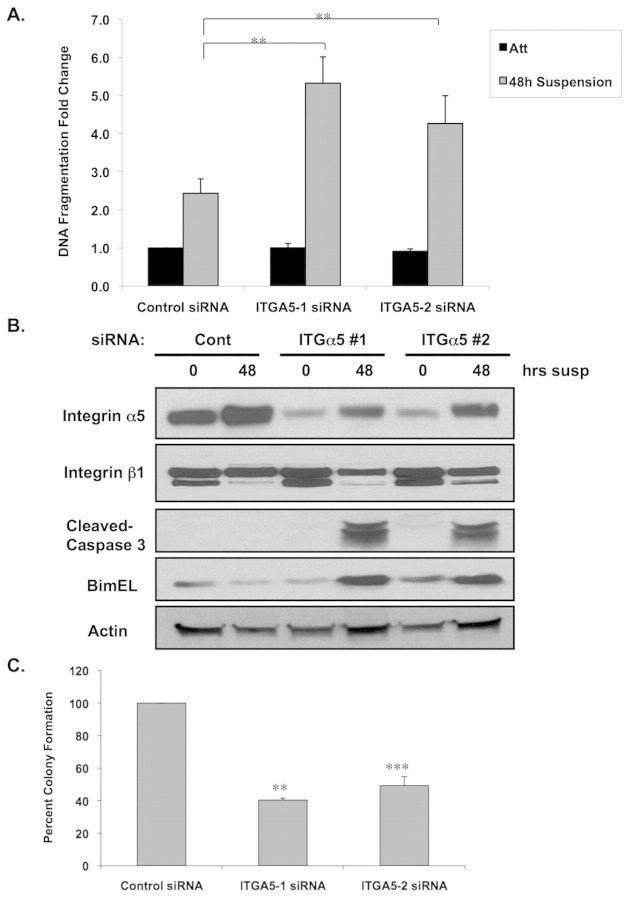

Since luminal apoptosis during morphogenesis is associated with anoikis, we sought to determine the role of integrin α5 in ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance. Following 48 hours of cell detachment, anoikis sensitivity was increased twofold in ErbB2-overexpressing cells that had been transfected with integrin α5 siRNA compared with cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these data, increased apoptosis in ErbB2 cells targeted with integrin α5 RNAi was associated with increased levels of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 4B). We have previously shown that ErbB2 partly blocks anoikis by inhibiting expression of the proapoptotic protein Bim during cell detachment (Reginato et al., 2003). Accordingly, we examined Bim expression in cells targeted with integrin α5 siRNA. ErbB2-overexpressing cells transfected with integrin α5 siRNA showed a substantial increase of Bim expression in cells in suspension, whereas transfection with control siRNA (Fig. 4B) or integrin α3 siRNA did not (data not shown). Although RNAi of integrin α5 led to significant increase in luminal apoptosis in 3D culture and increased anoikis sensitivity in suspended cells, we did not detect any evidence of apoptosis in attached ErbB2 cells in 2D culture (Fig. 4A) or in outer cells in direct contact with ECM in 3D culture (Fig. 3B). Decreasing integrin α5 levels did not alter sensitivity of ErbB2-overexpressing cells to other apoptotic stimuli including UV or hydrogen peroxide treatment (data not shown) in 2D cell culture, which suggests that the relationship between ErbB2, integrin α5 and apoptosis is specific to cells at low adhesion. Moreover, reducing integrin α5 in ErbB2-overexpressing cells did not alter overall cell growth at 3D conditions (supplementary material Fig. S2A) or in 2D attached cells (supplementary material Fig. S2B). Although the reduction of integrin α5 levels increased luminal apoptosis in ErbB2-overexpressing acini, we found that it only led to a partial hollowing of the lumen of these acini (data not shown). Since RNAi of integrin α5 had minimal effects on the growth of ErbB2 cells in 3D culture it is possible that these acini remain – despite increasing apoptosis – partially filled since they remain highly proliferative.

Fig. 4.

Integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance, Bim inhibition and anchorage independence. (A) At 48 hours after initial transfection with siRNA oligonucleotides against integrin α5 or luciferase control, MCF-10A-NeuN were harvested as attached cells, or placed in suspension for 48 hours and then analyzed for apoptosis using DNA-fragmentation ELISA. Values represent the mean ± s.e.m. of the fold change of A405 for at least three independent experiments (**P<0.05 by Students t-test when comparing results for the 48-hour suspension cells). (B) In parallel experiments, transfected cells were lysed from monolayer culture or from 448-hour suspension culture and proteins analyzed by immunoblotting. (C) MCF-10A cells stably overexpressing activated ErbB2 (NeuT) were transfected with luciferase control or integrin α5 siRNA oligonucleotides. At 48 hours after initial transfection cells were placed in soft agar plates for 21 days and then stained with INT Violet. Colony numbers were determined and the percentages normalized to that of control siRNA. The values shown represent averages of normalized values (n=3, mean ± s.e.m.; **P<0.001, ***P<0.05 by Students t test).

We also examined the role of integrin α5 in parental MCF-10A cells. We found that cell detachment of MCF-10A cells also resulted in the elevation of integrin α5 protein levels and that reduction of integrin α5 levels by using RNAi in suspension led to increased levels of Bim, cleaved caspase-3 (supplementary material Fig. S3A) and sensitized cells to anoikis, when compared with cells treated with control RNAi (supplementary material Fig. S3B). These findings suggest that integrin α5 has a general role in epithelial anoikis sensitivity. Reducing integrin α5 levels in parental MCF-10A cells did not alter cell growth or cell organization in 3D culture (supplementary material Fig. S3C). Thus, integrin α5 is crucial for anoikis sensitivity of both normal MCF-10A cells and those that overexpress ErbB2, and is required for ErbB2-mediated inhibition of the proapoptotic protein Bim in the absence of matrix attachment; however, it does not appear to affect cell growth.

We also examined the effect of reduced integrin α5 expression on ErbB2-mediated anchorage-independent colony formation. For these experiments we used cells that overexpress the active form of ErbB2 (NeuT) because they form robust colonies in soft agar. We found that NeuT-overexpressing cells when transfected with integrin α5 siRNA formed less than half as many colonies in soft agar compared with cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 4C). RNAi of integrin α3 had no effect on colony formation of NeuT cells in soft agar (data not shown). Thus, integrin α5 is specifically required for ErbB2-mediated anchorage independence. To verify specificity of siRNA oligonucleotides, ErbB2-overexpressing cells were infected with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against integrin α5, which – when compared with scrambled shRNA – was also able to reverse anoikis resistance, Bim inhibition and colony formation in soft agar (supplementary material Fig. S4). This effect of integrin α5 on ErbB2 oncogenesis seems to be specific, as reducing integrin α5 levels in MCF-10A cells that overexpress H-RasG12V, a constitutively active form of the oncogene H-Ras, had little effect on caspase-3 cleavage or Bim levels in cells in suspension (supplementary material Fig. S7A) and had no effect on anchorage-independent cell growth (supplementary material Fig. S7B). Thus, integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance in 3D acini, during anchorage independence and inhibition of Bim expression.

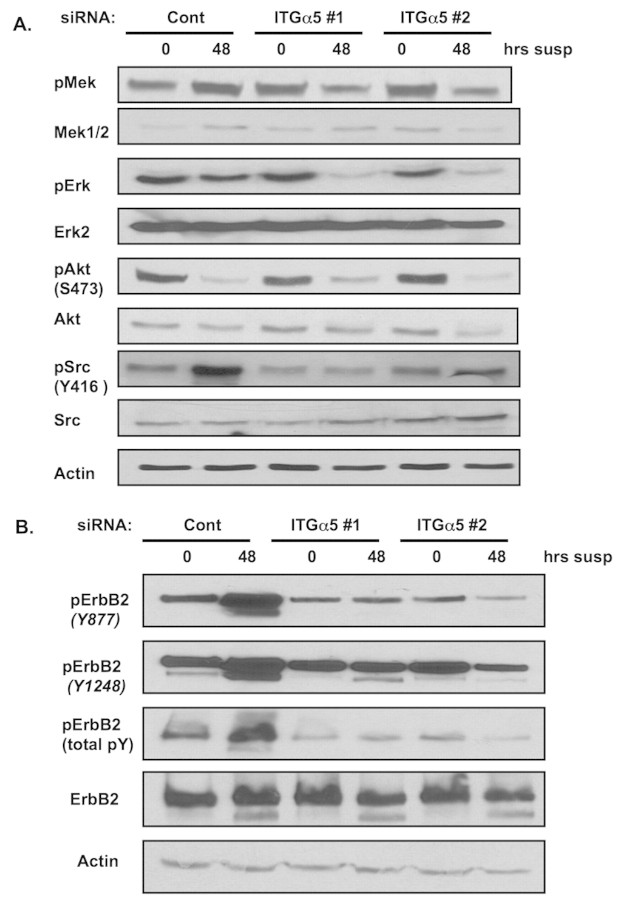

Role of integrin α5 in ErbB2-mediated signaling

Oncogenes, such as ErbB2, maintain active signaling pathways in the absence of matrix attachment that can regulate cell survival pathways. Indeed, we have shown that oncogene overexpression can maintain the Erk pathway active during cell detachment, allowing inhibition of both Bim expression and anoikis (Reginato et al., 2003) when compared with parental MCF-10A cells (supplementary material Fig. S3A). Thus, we examined the role of integrin α5 in the regulation of ErbB2-mediated signaling pathways. Decreased expression of integrin α5 had minor effects on signaling in attached ErbB2 cells (Fig. 5A). However, decreased integrin α5 expression in ErbB2-expressing cells decreased Mek and Erk activity when cells were placed in suspension (Fig. 5A) in a manner consistent with loss of Bim suppression (Fig. 4B, supplementary material Fig. S3A). To determine the source of altered signaling we examined whether integrin α5 regulated the activation of ErbB2 phosphorylation. Decreasing integrin α5 levels had little effect on ErbB2 phosphorylation in attached cells (Fig. 5B). Remarkably, in suspended cells we find total phosphotyrosine levels of ErbB2 highly elevated, as well a phosphorylation of Y877 and Y1248, which is in contrast to attached cells. Decreased integrin α5 levels reduced total phosphotyrosine levels of ErbB2 as well as phosphorylation of Y877 and Y1248 without altering the total levels of ErbB2 protein (Fig. 5B). Recent studies have shown that Src is a key regulator of ErbB2 tyrosine phosphorylation (Ishizawar et al., 2007) specifically at Y877 (Xu et al., 2007) and that Src activity is required for ErbB2-mediated soft-agar colony formation. We, therefore, sought to examine changes in Src activity in cells depleted of integrin α5. Cells transfected with control siRNA had low level of Src activity in attached cells. However, in cells placed in suspension, Src activity increased dramatically. By contrast, cells transfected with two different siRNAs targeting integrin α5 had slightly reduced levels of Src activity in attached cells and blocked induction of Src activity in cells placed in suspension (Fig. 5A). We did not detect changes in other integrin-mediated pathways, such as FAK (data not shown) or Akt, in suspended ErbB2-overexpressing cells. ErbB2-overexpressing cells that were infected with shRNA targeting integrin α5 also caused inhibition of total ErbB2 tyrosine activity and reduced Src phosphorylation when compared with cells infected with control shRNA (supplementary material Fig. S4A). In addition, we detected a similar signaling profile in cells overexpressing the active form of ErbB2 (supplementary material Fig. S5) and in the ErbB2-expressing breast cancer cell line SKBR3 following cell detachment and knockdown of integrin α5 (supplementary material Fig. S6A) and inhibited anchorage independence (supplementary material Fig. S6B,C). Therefore, we conclude that integrin α5 expression is required for maintaining full ErbB2-tyrosine phosphorylation and ErbB2-mediated Mek-Erk activity during cell detachment, and is associated with elevated Src activity in suspension.

Fig. 5.

Integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated signaling. (A-B) At 48 hours after initial transfection with luciferase control or integrin α5 siRNA oligos, MCF-10A-NeuN cells were placed in suspension for indicated times before lysis. Proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies.

As in ErbB2-overexpressing cells, normal MCF-10A cells also elevate Src activity when placed in suspension (supplementary material Fig. S3A), and reducing integrin α5 levels blocked activation of Src in the absence of adhesion, reduced Erk activity and increased Bim levels (supplementary material Fig. S3A). Since Src can also phosphorylate EGFR (Giannoni et al., 2008), and EGFR is an important regulator of Bim and anoikis of normal MCF-10A cells (Reginato et al., 2003), we examined levels of total and phosphorylated EGFR in parental MCF-10A cells that expressed reduced amounts of integrin α5. As previously reported, we noticed a rapid loss of total EGFR levels in MCF-10A cells placed in suspension and were unable to detect a difference between control RNAi and integrin α5 RNAi. However, we examined EGFR phosphorylation in ErbB2-overexpressing cells and found that RNAi of integrin α5 was able to reduce phosphorylation of EGFR in MCF-10A cells in suspension. This suggests that a decrease in integrin α5 levels can decrease the phosphorylation of EGFR in parental cells and may help explain increased anoikis sensitivity in MCF-10A cells with reduced levels of integrin α5.

Role of Src in ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance

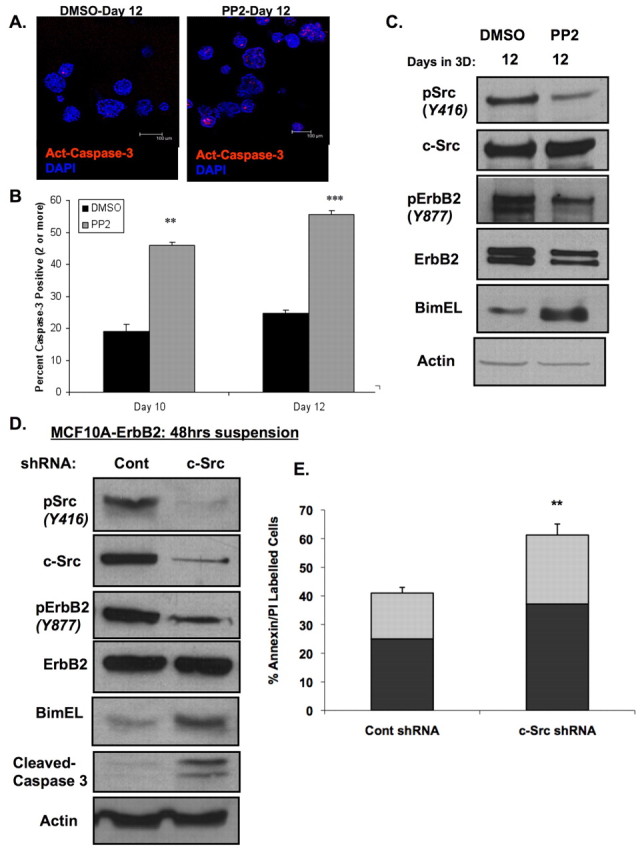

We hypothesized that expression of integrin α5 contributes to activation and/or maintenance of active Src during cell detachment, which could be required for optimal ErbB2 phosphorylation, leading to downstream signaling that allows anoikis resistance through inhibition of Bim. To test this, we examined the role of Src in ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance. Treatment of ErbB2 cells in suspension with the Src-family-kinase inhibitors PP1 or PP2 reversed anoikis resistance by ErbB2 (supplementary material Fig. S8A). Moreover, treatment of ErbB2 cells during anoikis with PP1 or PP2 showed a decrease of ErbB2 Y877 phosphorylation, an increase of Bim expression and elevated levels of cleaved caspase-3 (supplementary material Fig. S8B). Treatment of attached ErbB2-overexpressing cells with PP1 or PP2 had no effect on apoptosis or Bim expression (data not shown). We also tested the effect of Src inhibitors on ErbB2-overexpressing 3D acini. Starting at day 8, acini were treated for 48 hours with PP2, and analyzed for cleaved caspase-3 at days 10 and 12. We observed a twofold increase in cleaved caspase-3 staining within the centers of acini treated with PP2 (Fig. 6A,B). As was the case in cells transfected with integrin α5 siRNA, cells that underwent apoptosis due to treatment with Src inhibitor were predominantly in the center of each acini (Fig. 6A). We also sought to determine whether reversal of ErbB2-mediated protection from luminal apoptosis in 3D acini following application of PP2 correlated with Src activity, Y877 phosphorylation of ErbB2 and Bim expression. Indeed, 3D acini treated with PP2 were associated with decreased phosphorylation of Src on Y416, ErbB2 on Y877 and increased levels of Bim expression (Fig. 6C). Src inhibition under these conditions had neither an effect on 3D acini organization of parental MCF-10A cell, as indicated by the localization of integrins α6 and α5, nor on apoptosis of outer cells that were in direct contact with the ECM (supplementary material Fig. S9). To ensure specificity of the Src inhibitors, we used RNAi to target Src and found that reducing the expression of Src also blocked activation of ErbB2, reversed inhibition of Bim in suspended cells (Fig. 6D) and increased sensitivity to anoikis (Fig. 6E) – similar to the effects of Src inhibitors. Thus, a decrease in Src activity in ErbB2-overexpressing cells displaying reduced ECM adhesions leads to a decrease in ErbB2 activation and the reversal of anoikis resistance through the upregulation of Bim expression, and negatively affects ErbB2-mediated survival signaling in a manner similar to a reduction in the expression of integrin α5.

Fig. 6.

Integrin regulation of ErbB2-mediated survival is associated with Src activation in suspension and morphogenesis. (A-C) NeuN-expressing cells were cultured in 3D morphogenesis assay and treated on day 8 with DMSO vehicle control or PP2 (10 μM). (A) At days 10 and 12, acini were fixed and stained with antibody against activated caspase-3 (red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Representative confocal images for day 12 are shown, and (B) acini positive for activated caspase-3 were counted at days 10 and 12 following treatment and the percent of total acini are plotted (n=3, mean ± s.d., >100 acini/experiment; **P<0.001, ***P<0.0001 by Students t-test). (C) Cell lysates were prepared on day 12 and proteins analyzed by immunoblotting. (D,E) MCF-10A-NeuN cells were infected with lentivirus carrying shRNA constructs against Src or scrambled sequence control. (D) Cells were lysed after 48-hour suspension culture, and proteins analyzed by immunoblotting or (E) were stained with annexin V and propidium iodide, followed by FACS analysis (n=3). Black bars represent annexin V stain (early apoptosis), gray bars represent propidium iodide stain (late apoptosis). Histograms are plotted as mean ± s.e.m, *P<0.05 by Students t-test.

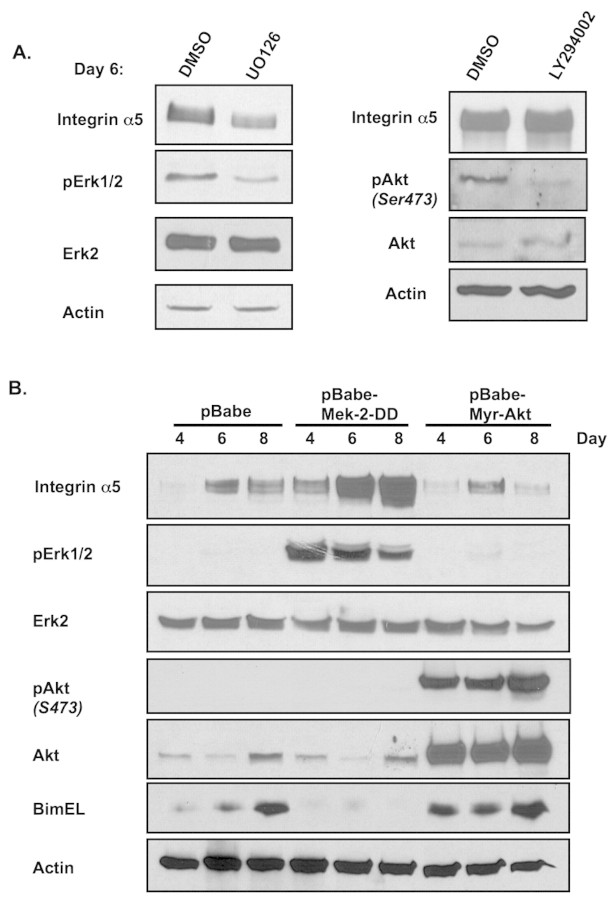

ErbB2 regulation of integrin α5 via the Mek-Erk pathway

To characterize ErbB2-mediated regulation of integrin α5 expression, we examined the effect that inhibiting several kinases downstream of ErbB2 would have on the expression of integrin α5 in MCF-10A cells in 3D culture. Incubation of ErbB2-expressing acini with a MEK inhibitor (UO126) for 48 hours blocked expression of integrin α5 (Fig. 7A), which suggests that signaling downstream of Mek regulates expression of integrin α5. Treatment of acini with the PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) had no effect on integrin α5 levels (Fig. 7A). To determine whether activation of the Erk pathway is sufficient to upregulate integrin α5 in 3D acini, stable pools of MCF-10A cells expressing a constitutively active variant of Mek (MEK2-DD) were generated and cultured in 3D. MCF10-A cells expressing MEK2-DD contained high levels of activated Erk compared with control acini and expression of integrin α5 during 3D morphogenesis was substantially upregulated (Fig. 7B). Overexpression of an active form of Akt (myristoylated Akt1) had no effect on the expression of integrin α5 (Fig. 7B). As previously shown, activation of the Mek-Erk pathway, but not the Akt pathway, blocks Bim expression in 3D acini (Fig. 7B) (Reginato et al., 2005). These results reveal that the Mek-Erk pathway in ErbB2-expressing 3D structures regulates expression of integrin α5.

Fig. 7.

ErbB2 regulates integrin α5 expression via the Mek-Erk pathway during morphogenesis. (A) MCF-10A-NeuN cells were cultured in 3D morphogenesis assay and treated on day 4 with DMSO vehicle control, U0126 (10 μM) or LY294002 (50 μM). At day 6, acini were lysed and proteins analyzed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. (B) MCF-10A cells stably overexpressing Mek2-DD, Myr-Akt or pBabe control vector were cultured in 3D morphogenesis assays and lysed at day 4, day 6 or day 8. Proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Taken together, these results indicate that increased levels of integrin α5 and increased Src activity in detached mammary epithelial cells functions as a survival mechanism to transiently protect cells against anokis. However, in cells that overexpress RTKs, such as ErbB2, elevation of integrin α5 and Src activity can maintain RTK activity, and allow Erk activation, inhibition of Bim expression and chronically block anoikis. Additionally, these data suggest that RTKs, such as ErbB2, are dependent on specific integrin subunits for anoikis resistance.

Discussion

Our findings show that overexpressed RTKs require specific integrin subunits for anoikis resistance at single-cell level, but also in the more tissue-relevant context of 3D culture. Previous work, using normal epithelial cells, has shown that integrin-mediated adhesion is required for correct growth-factor survival signaling (Reginato et al., 2003). Overexpression of RTKs, as found in many epithelial carcinomas, is thought to uncouple and bypass the requirement for integrin signaling in the absence of adhesion. Our results here reveal that RTKs can regulate specific integrin subunits to maintain their own activation and, thus, remain highly dependent on integrin function under conditions of no or reduced matrix adhesion. We show that epithelial cells that overexpress ErbB2 upregulate integrin α5 RNA and protein, and that integrin α5 is required for ErbB2-mediated anoikis resistance, which is associated with luminal filling during morphogenesis of spheroid epithelial structures in vitro. Moreover, integrin α5 is required in maintaining elevated Src activity, which contributes to ErbB2 phosphorylation and downstream Mek-Erk-mediated inhibition of Bim during loss of adhesion. Activation of Src by cells in suspension is required for ErbB2 phosphorylation, and ErbB2-mediated Bim inhibition and anoikis resistance. In addition, we show that normal epithelial cells also elevate expression of integrin α5 when detached from matrix, thereby allowing activation of Src in suspension to delay anoikis – possibly by maintaining RTK signaling, such as EGF receptor signaling. However, EGFR expression is not maintained in normal cells without adhesion (Reginato et al., 2003). Under conditions when RTKs, such as ErbB2, are overexpressed, our data suggest that Src activation during matrix deprivation functions to maintain RTKs active and protect cells from anoikis. Indeed, recent data in prostate cancer cells have shown that Src activation during cell detachment phosphorylates EGFR on Y845 (a site homologue to Y877 in ErbB2) during cell detachment and blocks anoikis through the Erk-Bim axis (Giannoni et al., 2009). The integrin-α5–Src survival pathway may be specific for RTKs because a reduction in integrin α5 had no effect on anchorage-independent growth of Ras-overexpressing cells. Thus, elevating integrin α5 under low adhesion might be a general mechanism of survival from anoikis that is co-opted by RTKs in cancer cells to maintain their own activity, promote cell survival and block luminal clearing in cases where tissue architecture and cell-matrix interactions are compromised – possibly in early stages of cancer.

Anoikis also serves as a barrier to metastasis (Reddig and Juliano, 2005) and, since integrin α5 is known to support epithelial migration and metastasis (Imanishi et al., 2007; Jia et al., 2004; Murthy et al., 1996), our results suggest that integrin α5 also contributes to survival during metastatic dissemination in the absence of matrix adhesion. Our data show that expression of integrin α5 positively correlates with breast cancers in which ErbB2 is overexpressed. While this manuscript was under review, an article by Valastyan et al. showed that levels of integrin α5 are also elevated in metastatic breast cancers as compared with primary tumors, and that expression of integrin α5 is associated with a cohort of genes that is associated with poor clinical outcome of breast cancer (Valastyan et al., 2009). Indeed, consistent with our results, Valastyan et al. also showed that integrin α5 has a crucial role in anoikis resistance of breast cancer cells in vitro. Thus, integrin α5 might serve as a key player in breast cancer progression including metastasis.

Integrins and RTKs are well know to collaborate and regulate a number of physiological processes including pathways that control cell growth, cell movement and survival (for reviews, see Lee and Juliano, 2004; Miranti and Brugge, 2002). Loss of adhesion can negatively regulate RTKs because detachment of normal cells can result in desensitization to EGF, e.g. by inhibiting the expression of EGFR (Reginato et al., 2003) and, possibly, by targeting receptors for degradation as is the case for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor (Baron and Schwartz, 2000). Interestingly, integrin β4 has recently been shown to cooperate with ErbB2 in a breast cancer mouse model (Guo et al., 2006). This study has shown that, by using a mouse model of ErbB2-induced mammary carcinoma containing an integrin-β4-signaling-deficient mutant, tumor growth and invasion was blocked in vivo. In addition, expression of this mutant reversed ErbB2-mediated acini disorganization, disruption of cell-cell junctions and polarity in 3D culture. In our study, the reduction of levels of integrin α5 had little to no effect on acinar cell growth, organization of cell-cell contacts or polarity of outer cells that were in direct contact with the ECM. Only inner cells in 3D acini that were not in direct contact with the ECM became sensitized to the loss of integrin α5. This is consistent with our finding that reducing integrin α5 in ErbB2-cells cultured in 2D did not alter cell growth or induce apoptosis in cells attached to plastic, but only had an effect during cell detachment. Our study suggests that ErbB2 activity and survival function becomes highly dependent on integrin α5 in the absence of strong ECM adhesions, and that ErbB2 depends on other integrins, such as integrin α6 and integrin β4, to amplify signals when in direct contact with the ECM.

Evidence of adhesion-independent, growth factor-dependent activities of integrins is also emerging and may be especially relevant in cancer cells overexpressing RTKs (Comoglio et al., 2003). Tumor cells overexpressing RTKs may be able to uncouple from normal regulation by cell adhesion, and also utilize integrins as adaptors to amplify signals. For example, in various tumor cell lines integrin β4 can act as a functional signaling molecule – without engagement of its extracellular ligand-binding domain – by complexing with the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor Met (Trusolino et al., 2001). Integrin β4 conspires with Met receptor for anchorage-independent growth by activating Met signaling towards the Ras-Erk cascade (Bertotti et al., 2006). It is still also possible that matrix adhesions contribute to the integrin α5 regulation of ErbB2 during cell detachment, as it has been shown for the autocrine loop of laminin-5–integrin-α6–integrin-β4–Rac described in the HMT-3544 human breast cancer progression series (Zahir et al., 2003). Although the experiments described in this manuscript were performed by using cells in suspension, they did not directly distinguish between a ligation-dependent or - independent role of integrin α5β1 because fibronectin is present in serum, and can be secreted and organized on the cell surface even in suspended cells. Nevertheless, we were unable to detect any staining of fibronectin, the major ligand for integrin α5, in centrally located cells in acini that overexpress ErbB2 (data not shown). We did not observe changes in FAK activity in ErbB2-overexpressing cells compared with normal cells and did not detect any FAK activity in cells in suspension, suggesting that FAK-dependent adhesion signaling was not involved. Whether integrin α5 has adhesion-independent adaptor functions for ErbB2 activation, as has been shown for integrin β4 regulation of the Met tyrosine kinase (Trusolino et al., 2001), remains to be determined.

Activation of Src is known to have a significant role in integrin and RTK cross talk, allowing synergy between these pathways, especially in transformed cells (Bromann et al., 2004). Our work shows that integrin α5 allows the maintenance of Src phosphorylation in the absence of cell adhesion that, in turn, allows ErbB2 activation and survival from anoikis. A number of studies have shown that detachment from the substratum induces an increase in the phosphorylation and activity of Src in tumor cell lines (Wei et al., 2004) and in nonmalignant rat intestinal epithelial cells (Loza-Coll et al., 2005). Intriguingly, in rat intestinal cells Src activity is transiently increased during cell detachment and contributes to transient protection from anoikis for about two hours. Moreover, Src activation in suspension correlates with anoikis resistance, as six anoikis-resistant lung-cancer cell lines were found to induce and maintain Src activation upon cell detachment (Wei et al., 2004). Our study suggests that overexpression of RTKs, such as ErbB2, induces the expression of specific integrins to help maintain Src activity in suspension. It is possible that elevated levels of integrin α5 help recruit Src to the plasma membrane in the absence of adhesion where it can proceed to activate ErbB2 on Y877 and maintain ErbB2 activity, therefore, inhibiting Bim expression and suppressing anoikis. Recent data from studies that used prostate cancer cells suggest a similar model of Src regulation of EGFR activation during cell detachment that maintains Erk active in suspension, and blocks Bim expression and anoikis (Giannoni et al., 2009). We hypothesize that a similar pathway may explain why a reduction of levels of integrin α5 in normal MCF-10A cells sensitizes these cells to anoikis because we also observed decreased Src and Erk activity and increased Bim levels. Although it is not clear how Src becomes active during cell detachment, studies have shown that some tyrosine kinase receptors, such as EGFR and PDGFR, can bind to Src through its SH2 domain and activate it (Bromann et al., 2004). In addition, recent studies have shown that maintenance of Src activation in prostate cancer cells in suspension requires the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Giannoni et al., 2009). It is not clear whether ROS have a role in Src regulation during anoikis in MCF-10A cells. However, recent studies showed that loss of adhesion in MCF-10A cells leads to increased ROS production, which was inhibited in MCF-10A cells overexpressing ErbB2 (Schafer et al., 2009). Since we did not detect major differences in Src activity in suspended cells overexpressing ErbB2 compared with parental MCF-10A cells (supplementary material Fig. S3A), this suggests that ErbB2 does not regulate Src activity in absence of adhesion directly or indirectly (via ROS alone). It will be of interest to determine whether integrin α5 has a role in ROS regulation of normal and ErbB2-overexpressing cells during cell detachment.

Accumulating evidence suggests that overexpression or increased activity of Src has a key role in ErbB2-mediated anchorage independence and cell survival (Bromann et al., 2004; Ishizawar and Parsons, 2004). However, the link to apoptotic pathways has not been well characterized. Previous studies have implicated Src regulation of Stat-3 control of Bcl-xL in cells that express EGFR and ErbB2 (Karni et al., 1999; Song et al., 2003) but in our studies we did not detect changes in Bcl-xL expression in ErbB2-overexpressing cells when compared with control MCF-10A cells, or in ErbB2 cells transfected with integrin α5 siRNA (data not shown). Our finding that Src is required for ErbB2-mediated inhibition of Bim during anoikis might explain in part how Src regulates ErbB2-mediated anchorage-independent survival. Interestingly, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, which are dependent on EGF receptor for survival, contain elevated levels of phosphorylated Src-family kinase. Treatment of these cells with Src inhibitor reduced phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB2, and induced apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2007). The regulation of Bcl-2 family members was not examined in this study but it is possible that the induction of Bim has a key role because a number of groups have implicated the regulation of Bim as essential for apoptosis induced by a range of EGFR and ErbB2 inhibitors in NSCLC (Costa et al., 2007; Cragg et al., 2007; de La Motte Rouge et al., 2007; Deng et al., 2007) and breast cancer cell lines (Piechocki et al., 2007). Thus, our study suggest that the regulation of ErbB2-Erk axis by integrin α5 and Src is not only crucial for regulating Bim, anoikis resistance and tumor oncogenesis, but may also be a cascade vital for the development of novel cancer-therapy strategies.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and materials

MCF-10A cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained as described previously (Reginato et al., 2003). Briefly, cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% donor horse serum, 20 ng/ml EGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 1 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma), 100 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Poly-HEMA and methylcellulose were purchased from Sigma. LY294002 and U0126 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). PP1 and PP2 were purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Growth factor-reduced Matrigel was obtained from BD-Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Primary antibodies against phosphorylated ErbB2 (Y877), α-cleaved caspase 3, phosphorylated Mek1/2 (S217/S221), phosphorylated Akt (S473), Akt, phosphorylated EGFR (Y845), EGFR, phosphorylated Src (Y416), Src were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Antibodies against Actin, Integrin α5, Mek1, IgG-HRP and Erk2 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against integrin α5 (for immunofluorescence), integrin β1 and phosphotyrosine-PY20 were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against integrin α3 and integrin α6 were obtained from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Antibodies against ErbB2 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), phosphorylated Erk1/2 (T185/Y187) (Biosource, Camarillo, CA) and Bim (Stressgen, Ann Arbor, Michigan) were also obtained.

Retrovirus vectors and stable cell lines

Retroviral vectors pBabe-NeuN, (human wildtype ErbB2), pBabe-MEK2-DD, pLNCX-Myr-Akt1 and pBabe-H-RasV12 for stable gene expression have been described previously (Gunawardane et al., 2005; Reginato et al., 2003). Constitutively active ErbB2 mutant (pBabe-NeuT) was kindly provided by Danielle Carroll (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Vesicular stomatitis virus G-protein-pseudotyped retroviruses were produced and MCF-10A cells were infected and selected as previously described (Reginato et al., 2003).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Equal amounts of total RNA (250 ng) were added to Brilliant II quantitative real-time (QRT)-PCR master mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with primer/probe sets from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). PCR reactions were performed in a volume of 25 μl by using a MX 3000 machine, and analysis was performed using the MxPro software according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). Gene and catalog numbers for the primer/probe sets are as follows: ITGA2 (Hs00158148_m1), ITGA5 (Hs00233732_m1) and ITGA6 (Hs01041011_m1). Expression of the housekeeping gene cyclophillin A (Hs99999904_m1) was used as an internal loading control. Reacions were conducted in duplicate in at least three independent experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays containing formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded breast-tumor tissue samples and normal breast tissue samples were obtained from US Biomax, Inc (Rockville, MD). Breast cancer tissue microarrays BR961 and BRC961, containing 70 cases of ErbB2-positive tissue and 24 cases of ErbB2-negative tissue, were de-paraffinized and rehydrated. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed at 95°C for 30 minutes using the DakoCytomation Target Retrieval Solution (Dako North America, Inc, Carpinteria, CA). This was followed by a peroxide block in 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase activity and, subsequently, a 1-hour block in 10% goat serum in 1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Tissue samples were incubated with anti-integrin α5 antibody (Santa Cruz) at 4 μg/ml in antibody diluent (DakoCytomation) overnight in a humidified chamber at room temperature. Primary antibody was detected using goat anti-rabbit IgG-peroxidase antibody (Sigma) at 35 μg/ml in antibody diluent, and signals were amplified and visualized by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB kit, DakoCytomation). Sections were counterstained using Harris hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted using Permount solution (Fisher). For statistical analysis, all cases that stained negative (–) for integrin α5 staining were classified as negative and all cases with +, ++ or +++ were classified as positive. Similar assessment was done for ErbB2-negative and -positive tissue. For statistical analysis, Pearson's correlation was used to analyze the relationship between integrin α5 expression and ErbB2 expression. Results were considered significant at P<0.05.

Western blot analysis

Lysates from 2×106-5×106 MCF-10A cells, either attached or in suspension for the indicated times, were prepared in RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% DOC, 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8, 0.1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 5 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4) supplemented with 1 μg/ml pepstatin, leupeptin, aprotinin and 200 μg/ml phenyl methylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C, analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Lysates were collected from cells in 3D as previously described (Reginato, 2005). Briefly, acini were washed with PBS, incubated with RIPA buffer for 15 minutes at 4°C and proteins then analyzed by western blotting using SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

RNA interference

Transfection of small interfering RNA (siRNA) was carried out as previously described (Reginato et al., 2003; Reginato et al., 2005). Briefly, MCF-10A cells were plated onto six-well plates at 2×105 cells/well. After 24 hours, cells were transfected with double-stranded RNA-DNA hybrids at a final concentration of 1 μg annealed oligonucleotide using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Cells were retransfected as described at 48 hours. At 76 hours after initial transfection, cells were used in specific assay at the indicated times. Initial small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides (SMARTpool) were obtained from Dharmacon Research (Lafayette, CO) for integrins α5 and α3. Control sense (luciferase) 5′-(GGCUCCCGCUGAAUUGGAAUU)d(TT)-3′; ITGA5#1 sense 5′-(GCAAGAAUCUCAACAACUCUU)d(TT)-3′; ITGA5#2 sense 5′-(GAGAGGAGCCUGUGGAGUAUU)d(TT)-3′; and ITGA3 sense 5′-(GUGUACAUCUAUCACAGUAUU)d(TT)-3′.

Lentivirus vectors and stable cell lines

Stable cell lines for shRNA knockdowns were generated by infection with the lentiviral vector pLKO.1-puro carrying a shRNA sequence for scrambled (Addgene) (Sarbassov et al., 2005), Src (Sigma-Aldrich) and integrin α5 (Open Biosystems). VSVG-pseudotyped lentivirus was generated by the co-transfection of 293-T packaging cells with 10 μg of DNA and packaging vectors as described (Rubinson et al., 2003). Scrambled shRNA sequence used is 5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCGCTCTAGCGAGGGCGACTTAACCTT-3′. Src shRNA sequence used is 5′-CCGGGACAGACCTGTCCTTCAAGAACTCGAGTTCTTGAAGGACAGGTCTGTCTTTTTG-3′. Integrin α5 shRNA sequence used is 5′-AGGCCATGATGAGTTTGGCCGATTCTCGAGAATCGGCCAAACTCATCATGG-3′. MCF-10A cells overexpressing ErbB2 were infected as previously described (Reginato et al., 2003).

Colony formation using soft-agar assay

Cells were grown in soft agar and fed as described (Gunawardane et al., 2005). Cells were incubated for 21 days and then stained with 500 μl of 0.05% p-Iodonitrotetrazolium (INT)-violet overnight. Colonies (>50 μm in diameter) were counted using a Leica DM IRB inverted research microscope (Bannockburn, IL). All assays were conducted in duplicate in at least three independent experiments.

Detachment-induced apoptosis assay

MCF-10A cells were placed in suspension in growth medium as previously described (Reginato et al., 2003). Briefly, tissue culture plates were coated with poly-HEMA (6 mg/ml), incubated at 37°C until dry and washed with PBS before use. Cells were placed in growth medium containing 0.5% methylcellulose (to avoid cell clumping) in suspension at a density of 5×105 cells/ml and plated on poly-HEMA-coated plates for the indicated time. Cells were then washed with 1× PBS and counted. 2,5×104 cells were used to determine apoptosis with the cell death detection ELISA-kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) according to manufacturer's instructions. For some experiments, after washing cells with PBS, they were resuspended in 1×-binding buffer from the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD-Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. FITC annexin V and propidium iodide (Annexin V-FITC kit) were added and the cells incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15 minutes followed by analysis using Guava Technologies EasyCyte Plus. Data were analyzed by using Guava Cytosoft 5.3 software. All time points were performed in duplicate and each experiment was carried out at least three times.

3D morphogenesis assay

Assays were performed as previously described (Reginato et al., 2005). Briefly, cells were resuspended in assay medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2% donor horse serum, 10 μg/ml insulin, 1 ng/ml cholera toxin, 100 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin and 5 ng/ml EGF). Eight-well chamber slides (BD Falcon) were coated with 45 μl Matrigel per well and 5×103 cells were plated per well in assay medium containing final concentration of 2% matrigel. Assay medium containing 2% Matrigel was replaced every 4 days and chemical inhibitors were supplemented to medium as indicated.

Immunofluorescence and image acquisition

Structures were prepared as previously described (Reginato et al., 2005). Briefly, acini were fixed in 4% formalin for 20 minutes. Fixed structures were washed with PBS-glycine (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 100 mM glycine). Structures were then blocked in IF buffer (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3.5 mM NaH2PO4, 7.7 mM NaN3, 0.1% BSA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.05% Tween 20) plus 10% goat serum for 1 hour, followed by secondary blocking buffer for 40 minutes. Primary antibodies were diluted in secondary blocking buffer, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C. After washing, acini were incubated with secondary antibodies coupled with Alexa-Fluor dyes (Molecular Probes). Structures were incubated with 0.5 ng/ml of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma) before being mounted with Prolong (Molecular Probes). Quantification of caspase-3 staining of structures was performed at 40× magnification. A minimum of 100 acinar structures were counted per experiment,and each experiment was performed three independent times. Confocal analysis was performed using the Leica DM6000 B Confocal Microscope. Images were generated using the Leica Confocal Imaging Software System and converted to Tiff format.

Acknowledgements

We thank Danielle Carroll for helpful discussions, and Shami Jagtap and Ian Henderson for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Department of Defense (DOD) Breast Cancer Research Program Predoctoral Fellowship (to K.K.H.).

Footnotes

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.050906/-/DC1

References

- Aranda V., Haire T., Nolan M. E., Calarco J. P., Rosenberg A. Z., Fawcett J. P., Pawson T., Muthuswamy S. K. (2006). Par6-aPKC uncouples ErbB2 induced disruption of polarized epithelial organization from proliferation control. Nat. Cell. Biol. 8, 1235-1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron V., Schwartz M. (2000). Cell adhesion regulates ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39318-39323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertotti A., Comoglio P. M., Trusolino L. (2006). Beta4 integrin activates a Shp2-Src signaling pathway that sustains HGF-induced anchorage-independent growth. J. Cell Biol. 175, 993-1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromann P. A., Korkaya H., Courtneidge S. A. (2004). The interplay between Src family kinases and receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene 23, 7957-7968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comoglio P. M., Boccaccio C., Trusolino L. (2003). Interactions between growth factor receptors and adhesion molecules: breaking the rules. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 565-571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D. B., Halmos B., Kumar A., Schumer S. T., Huberman M. S., Boggon T. J., Tenen D. G., Kobayashi S. (2007). BIM mediates EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced apoptosis in lung cancers with oncogenic EGFR mutations. PLoS Med. 4, 1669-1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg M. S., Kuroda J., Puthalakath H., Huang D. C., Strasser A. (2007). Gefitinib-induced killing of NSCLC cell lines expressing mutant EGFR requires BIM and can be enhanced by BH3 mimetics. PLoS Med. 4, 1681-1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Motte Rouge T., Galluzzi L., Olaussen K. A., Zermati Y., Tasdemir E., Robert T., Ripoche H., Lazar V., Dessen P., Harper F., et al. (2007). A novel epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor promotes apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells resistant to erlotinib. Cancer Res. 67, 6253-6262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath J., Brugge J. S. (2005). Modelling glandular epithelial cancers in three-dimensional cultures. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 675-688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnath J., Mills K. R., Collins N. L., Reginato M. J., Muthuswamy S. K., Brugge J. S. (2002). The role of apoptosis in creating and maintaining luminal space within normal and oncogene-expressing mammary acini. Cell 111, 29-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J., Shimamura T., Perera S., Carlson N. E., Cai D., Shapiro G. I., Wong K. K., Letai A. (2007). Proapoptotic BH3-only BCL-2 family protein BIM connects death signaling from epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition to the mitochondrion. Cancer Res. 67, 11867-11875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch S. M., Screaton R. A. (2001). Anoikis mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 555-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni E., Buricchi F., Grimaldi G., Parri M., Cialdai F., Taddei M. L., Raugei G., Ramponi G., Chiarugi P. (2008). Redox regulation of anoikis: reactive oxygen species as essential mediators of cell survival. Cell Death Differ. 15, 867-878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni E., Fiaschi T., Ramponi G., Chiarugi P. (2009). Redox regulation of anoikis resistance of metastatic prostate cancer cells: key role for Src and EGFR-mediated pro-survival signals. Oncogene 28, 2074-2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardane R. N., Sgroi D. C., Wrobel C. N., Koh E., Daley G. Q., Brugge J. S. (2005). Novel role for PDEF in epithelial cell migration and invasion. Cancer Res. 65, 11572-11580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Pylayeva Y., Pepe A., Yoshioka T., Muller W. J., Inghirami G., Giancotti F. G. (2006). Beta 4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell 126, 489-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. R. (2004). Diseases of the Breast. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; [Google Scholar]

- Hynes N. E., Stern D. F. (1994). The biology of erbB-2/neu/HER-2 and its role in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1198, 165-184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanishi Y., Hu B., Jarzynka M. J., Guo P., Elishaev E., Bar-Joseph I., Cheng S. Y. (2007). Angiopoietin-2 stimulates breast cancer metastasis through the alpha(5)beta(1) integrin-mediated pathway. Cancer Res. 67, 4254-4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawar R., Parsons S. J. (2004). c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell 6, 209-214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawar R. C., Miyake T., Parsons S. J. (2007). c-Src modulates ErbB2 and ErbB3 heterocomplex formation and function. Oncogene 26, 3503-3510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y., Zeng Z. Z., Markwart S. M., Rockwood K. F., Ignatoski K. M., Ethier S. P., Livant D. L. (2004). Integrin fibronectin receptors in matrix metalloproteinase-1-dependent invasion by breast cancer and mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 64, 8674-8681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karni R., Jove R., Levitzki A. (1999). Inhibition of pp60c-Src reduces Bcl-XL expression and reverses the transformed phenotype of cells overexpressing EGF and HER-2 receptors. Oncogene 18, 4654-4662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. W., Juliano R. (2004). Mitogenic signal transduction by integrin- and growth factor receptor-mediated pathways. Mol. Cells 17, 188-202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrisch C., Piccart M. (2001). An overview of HER2. Semin. Oncol. 28, 3-11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loza-Coll M. A., Perera S., Shi W., Filmus J. (2005). A transient increase in the activity of Src-family kinases induced by cell detachment delays anoikis of intestinal epithelial cells. Oncogene 24, 1727-1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailleux A. A., Overholtzer M., Schmelzle T., Bouillet P., Strasser A., Brugge J. S. (2007). BIM regulates apoptosis during mammary ductal morphogenesis, and its absence reveals alternative cell death mechanisms. Dev. Cell 12, 221-234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranti C. K., Brugge J. S. (2002). Sensing the environment: a historical perspective on integrin signal transduction. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, E83-E90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy M. S., Reid S. E., Jr, Yang X. F., Scanlon E. P. (1996). The potential role of integrin receptor subunits in the formation of local recurrence and distant metastasis by mouse breast cancer cells. J. Surg. Oncol. 63, 77-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuswamy S. K., Li D., Lelievre S., Bissell M. J., Brugge J. S. (2001). ErbB2, but not ErbB1, reinitiates proliferation and induces luminal repopulation in epithelial acini. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 785-792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R., Yu D., Hung M. C., Hortobagyi G. N., Esteva F. J. (2006). Mechanisms of disease: understanding resistance to HER2-targeted therapy in human breast cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 3, 269-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechocki M. P., Yoo G. H., Dibbley S. K., Lonardo F. (2007). Breast cancer expressing the activated HER2/neu is sensitive to gefitinib in vitro and in vivo and acquires resistance through a novel point mutation in the HER2/neu. Cancer Res. 67, 6825-6843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddig P. J., Juliano R. L. (2005). Clinging to life: cell to matrix adhesion and cell survival. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 24, 425-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reginato M. J., Muthuswamy S. K. (2006). Illuminating the center: mechanisms regulating lumen formation and maintenance in mammary morphogenesis. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 11, 205-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reginato M. J., Mills K. R., Paulus J. K., Lynch D. K., Sgroi D. C., Debnath J., Muthuswamy S. K., Brugge J. S. (2003). Integrins and EGFR coordinately regulate the pro-apoptotic protein Bim to prevent anoikis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 733-740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reginato M. J., Mills K. R., Becker E. B., Lynch D. K., Bonni A., Muthuswamy S. K., Brugge J. S. (2005). Bim regulation of lumen formation in cultured mammary epithelial acini is targeted by oncogenes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4591-4601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinson D. A., Dillon C. P., Kwiatkowski A. V., Sievers C., Yank L., Kopinja J., Rooney D. L., Zhang M., Ihrig M. M., McManus M. T., et al. (2003). A lentivirus-based system to functionally silence genes in primary mammalian cells, stem cells and transgenic mice by RNA interference. Nat. Genet. 3, 401-406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov D. D., Guertin D. A., Ali S. M., Sabatini D. M. (2005). Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 307, 1098-1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer Z. T., Grassian A. R., Song L., Jiang Z., Gerhart-Hines Z., Irie H. Y., Gao S., Puigserver P., Brugge J. S. (2009). Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment. Nature 461, 109-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M. A. (1997). Integrins, oncogenes, and anchorage independence. J. Cell Biol. 139, 575-578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C. D., Anyiwe K., Schimmer A. D. (2008). Anoikis resistance and tumor metastasis. Cancer Lett. 272, 177-185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L., Turkson J., Karras J. G., Jove R., Haura E. B. (2003). Activation of Stat3 by receptor tyrosine kinases and cytokines regulates survival in human non-small cell carcinoma cells. Oncogene 22, 4150-4165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trusolino L., Bertotti A., Comoglio P. M. (2001). A signaling adapter function for alpha6beta4 integrin in the control of HGF-dependent invasive growth. Cell 107, 643-654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastyan S., Reinhardt F., Benaich N., Calogrias D., Szasz A. M., Wang Z. C., Brock J. E., Richardson A. L., Weinberg R. A. (2009). A pleiotropically acting microRNA, miR-31, inhibits breast cancer metastasis. Cell 137, 1032-1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Wei L., Yang Y., Zhang X., Yu Q. (2004). Altered regulation of Src upon cell detachment protects human lung adenocarcinoma cells from anoikis. Oncogene 23, 9052-9061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White D. E., Kurpios N. A., Zuo D., Hassell J. A., Blaess S., Mueller U., Muller W. J. (2004). Targeted disruption of beta1-integrin in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer reveals an essential role in mammary tumor induction. Cancer Cell 6, 159-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Yuan X., Beebe K., Xiang Z., Neckers L. (2007). Loss of Hsp90 association up-regulates Src-dependent ErbB2 activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 220-228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahir N., Lakins J. N., Russell A., Ming W., Chatterjee C., Rozenberg G. I., Marinkovich M. P., Weaver V. M. (2003). Autocrine laminin-5 ligates alpha6beta4 integrin and activates RAC and NFkappaB to mediate anchorage-independent survival of mammary tumors. J. Cell Biol. 163, 1397-1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Kalyankrishna S., Wislez M., Thilaganathan N., Saigal B., Wei W., Ma L., Wistuba I. I., Johnson F. M., Kurie J. M. (2007). SRC-family kinases are activated in non-small cell lung cancer and promote the survival of epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent cell lines. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 366-376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]