Abstract

Purpose

Recent studies demonstrate that adolescent growth without corresponding strength adaptations may lead to the development of risk factors for patellofemoral pain and anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Our purpose was to investigate the longitudinal trajectories of lower extremity strength across maturational stages for a cohort of female student-athletes.

Methods

A nested cohort design was used to identify 39 subjects who had complete knee flexion, knee extension, and hip abduction strength data for 3 test sessions spaced approximately 1 year apart and during which they transitioned from pre-pubertal to a pubertal status.

Results

Knee extension strength increased while hip abduction and hamstrings-to-quadriceps ratio strength decreased from pre-pubertal to pubertal stages (p < .05). No effects of time with respect to knee flexion strength or non-dominant/dominant limb differences were found (P > .05).

Conclusion

These data provide support that pre-adolescence is an optimal time to institute strength training programs aimed toward injury prevention.

Keywords: adolescent, female, puberty/physiology, strength

Introduction and Purpose

Recent evidence indicates that 2 common lower extremity musculoskeletal conditions increase in incidence among young athletes during adolescence: injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and patellofemoral pain (PFP) syndrome.1-3 Although ACL injuries and the emergence of PFP increase for both males and females around the time of puberty and throughout adolescence, females sustain ACL injuries at least 4 to 6 times more frequently4-6 and are affected by PFP 2 to 10 times more often than their male counterparts.7,8 Both ACL injuries and PFP are associated with pain and significant reductions in activity levels during acute recovery phases.9 Both conditions have also been linked to amplified risk for reinjury/recurrence and degenerative joint pathology.3,10-13 Moreover, the lifelong effect these conditions may have on a person's future risk profile is underscored by the potential to trigger a downward spiral of health concerns that begins with pain and decreased activity levels, and over time can lead to poor cardiovascular fitness, obesity and diabetes.14,15 Therefore, a thorough understanding of the underlying pathomechanics that lead to increased incidence of PFP and ACL injuries during adolescence could considerably enhance clinicians' ability to identify and address the risk factors that predispose young athletes to these conditions and the associated long-term sequelae.

A number of studies demonstrate that musculoskeletal growth during puberty in the absence of corresponding neuromuscular adaptation in athletes may facilitate the development of known risk factors for ACL injuries and PFP such as hamstrings-to-quadriceps strength imbalances, hip weakness, and decreased neuromuscular control of the knee,.1,3,16-19 Differences between males' and females' neuromuscular performance in many of these same variables have been reported to begin to emerge around the time of pubertal maturation.17,18,20,21 These sex-specific developmental changes and resultant divergence in neuromuscular profiles may be associated with the disparity in incidence of ACL injury and PFP between the sexes during adolescence and perhaps indicative of an optimal window of opportunity for prevention and treatment of these injuries and disorders.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the longitudinal trajectories of lower extremity strength (defined here as muscle power at a constant velocity normalized to body mass) across maturational stages for a cohort of female adolescent student-athletes. It was hypothesized that as subjects progressed from pre-pubertal to pubertal and late/post-pubertal levels, deficits in hip abduction and hamstring-to-quadriceps strength would emerge. The results of the study are discussed relative to known risk factors and potential prevention strategies for ACL injuries and PFP in female adolescents.

Methods

Subjects

A nested longitudinal cohort design was used to identify subjects from a prospectively collected, longitudinal pool of anthropometric, biomechanical and maturational data for a large geographical cohort of female adolescent soccer and basketball players (n = 709). Entire teams were brought in at the beginning and end of each season for testing sessions, and longitudinal data were collected for all subjects. However, successive year-to-year data was available only for subjects that did not graduate and made the team roster in consecutive years. To be included into the present study, subjects had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) have complete data for 3 test sessions spaced approximately 1 year from the previous visit, 2) be classified as “pre-pubertal” for at least 1 visit on a modified Pubertal Maturation Observational Scale (PMOS), 3) have at least 1 visit in which the PMOS rating had transitioned to “pubertal,” and 4) have no history of knee, hip, back or ankle surgery.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and informed written consent was obtained from both the child and a parent or guardian prior to data collection. A total of 39 subjects were identified as having 3 consecutive testing sessions that occurred approximately 12 months (12.0 ± 0.1 months) apart that corresponded with the start of the athlete's athletic season each year and met all additional inclusion criteria. All subjects that met the study's criteria were soccer players as there was no pre-pubertal data for any of the basketball players. Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic information for subjects at each pubertal stage.

Table 1. Subject descriptions at each stage/testing session.

| Pubertal Stage | Number of subjects (n) | Age in years (range; mean ± SD) | Height in cm (range; mean ± SD) | Percent of Adult Stature (range; mean ± SD) | Body Mass Index in kg (range; mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pubertal | 39 | 11.13-13.03; 12.18 ± 0.08 | 138-165; 150.19 ± 0.82 | 0.83-0.91; 0.86 ± 0.00 | 13.04-23.33; 17.49 ± 0.33 |

| Pubertal Year 1 | 39 | 12.08-14.05; 13.17 ± 0.08 | 144-173; 156.89 ± 0.82 | 0.88-0.95; 0.90 ± 0.00 | 14.21-22.84; 18.46 ± 0.31 |

| Pubertal Year 2 | 39 | 13.09-15.03; 14.17 ± 0.10 | 149-178; 161.68 ± 0.93 | 0.92-0.97; 0.94 ± .00 | 11.49-22.29; 19.35 ± 0.33 |

Procedures

At each testing session, subjects' body mass and height were measured using a calibrated physician scale and a stadiometer while subjects stood with bare feet. Subjects were asked to identify which leg they would prefer to use to kick a ball as far as possible. The leg each subject identified as the preferred kicking leg was recorded as the dominant lower limb. Also, during each testing session, the modified PMOS was used to classify subjects into one of 3 maturational categories: pre-pubertal (approximately Tanner stage 1), early pubertal (approximately Tanner stages 2 and 3), and late/post-pubertal (approximately Tanner stages 4 and 5). The modified PMOS includes both parental questionnaires and an observational questionnaire completed by an investigator.22,23 The questionnaires are comprised of questions related to the development of secondary sex characteristics associated with puberty such as acne, recent growth spurt, sweating after physical activities, evidence of muscular development, darkened underarm hair, onset of menarche, and breast development. The original PMOS was modified based on recommendations from specialists in adolescent health to include a more specific breakdown the item of “has begun menarche” to a more precise weighting of “the adolescent began menarche < 1 year ago, 1-2 years ago or greater than 1 year ago” as well as to include additional questions regarding height of biological parents in order to calculate percent of adult stature. The PMOS has demonstrated good reliability and has been used successfully in previous studies to differentiate between different pubertal stages.16,23,24

An isokinetic dynamometer was utilized to measure peak isokinetic torque production of the knee flexors, knee extensors, and hip abductors. For the knee flexors and knee extensor tests, subjects were seated on the dynamometer with the trunk perpendicular to the floor, the hip flexed to 90°, and the knee flexed to 90°. A 5-repetition knee extension-flexion warm-up at 300°/sec for each leg was performed prior to the test. The recorded test session consisted of 10 repetitions of knee extension-flexion with each limb at 300°/sec. This speed and number of repetitions were selected based on previous studies using a similar protocol that investigated knee injury risk factors.25-28 For the hip abduction test, subjects were positioned in a standing position facing the dynamometer head, and secured with a strap around the waist just above the iliac crest. The dynamometer head was positioned so that the axis of rotation of the dynamometer aligned with the center of rotation of the hip. Subjects performed 5 maximum effort repetitions at a speed of 120°/sec. This speed was determined based on pilot testing that determined that 120°/sec could be comfortably executed in the standing position and still approximate actual hip abduction/adduction velocities that occur during high-risk cutting tasks. Intra-rater reliability using a single investigator for these methods has been demonstrated to be good to excellent with intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.86 on the left (CI 0.58, 0.97) and 0.92 on the right (CI 0.727, 0.984).29 These methods have been used previously to investigate hip strength in female adolescent athletes.30,31 Peak torques for all test repetitions were recorded for knee flexion, knee extension and hip abduction. Subsequently, all peak torque values were normalized to each subject's body mass (Nm/kg).

Statistical analysis

To align subjects according to maturational status rather than by chronological age or visit number, a spreadsheet was created for each variable and arranged according to pubertal status. The first testing session where a subject was classified with a pubertal status essentially became time point 0 (labeled as “pubertal”). All variables were graphed longitudinally for 1 year prior to puberty through 1 year after first being classified as pubertal (labeled as “late/post-pubertal”). Statistical analysis was also performed for the pre-pubertal, pubertal and late/post-pubertal categories.

Two-way repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVA) with 3 time levels and 2 levels for leg (dominant compared to non-dominant limb) were conducted for knee extensor (quadriceps) strength, knee flexor (hamstrings) strength, hamstrings-to-quadriceps strength ratio (ham:quad ratio), and hip abductor strength. The alpha level was set a priori at α < .05 with a Bonferroni adjustment made for multiple comparisons.

Results

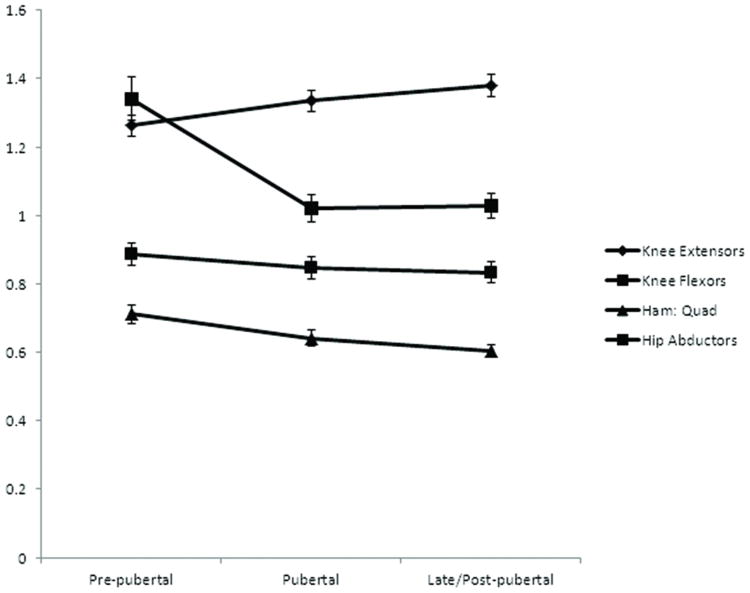

Figure 1 provides a graph of the strength trajectories (mean of the dominant and non-dominant limbs) for each strength variable across pubertal stages. Statistically significant effects for time were observed for knee extensor strength, hamstrings to quadriceps strength ratio and hip abductor strength (p < .05). No effects for time were found for knee flexion strength or for dominant to non-dominant limb differences for any of the strength measures (P > .05). Table 2 provides subjects' 95% confidence intervals for the means of each strength variable at each of the pubertal stages.

Figure 1. Trajectories of peak torque relative to body mass across pubertal stages (Nm/kg)*.

*Graphs were created using the mean of the dominant and non-dominant limbs' peak torque to body mass ratios. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) for each strength measure.

Table 2. 95% Confidence intervals for each strength variable at each pubertal stage (Nm/kg).

| Variable | 95% Confidence Interval for Pubertal Stage Means | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lower Bound Pre-pubertal to Pubertal Year 1 | Upper Bound Pre-pubertal to Pubertal Year 1 | Lower Bound Pubertal Year 1 to Pubertal Year 2 | Upper Bound Pubertal Year 1 to Pubertal Year 2 | Lower Bound Pre-pubertal to Pubertal Year 2 | Upper Bound Pre-pubertal to Pubertal Year 2 | |

| Knee Extensor | 1.201 | 1.324 | 1.274 | 1.397 | 1.316 | 1.448 |

| Knee Flexor | 0.819 | 0.953 | 0.782 | 0.911 | 0.772 | 0.895 |

| Ham:Quad Ratio | 0.657 | 0.773 | 0.595 | 0.692 | 0.569 | 0.643 |

| Hip Abductor | 1.128 | 1.527 | 0.978 | 1.336 | 0.910 | 1.165 |

Pairwise comparison tests indicated a statistically significant increase (mean change; 95% confidence interval) in knee extensor strength from pre-pubertal to pubertal status (0.073; 0.00 to 0.146 Nm/kg) and from pre-pubertal to late/post-pubertal (0.119; 0.066 to 0.172 Nm/kg), but no statistically significant change from pubertal to late/post-pubertal (0.046; -0.118 to 0.026 Nm/kg). Pairwise comparison tests for hamstrings-to-quadriceps ratio demonstrated a statistically significant decrease for pre-pubertal to pubertal (0.071; 0.000 to 0.143 Nm/kg) and from pre-pubertal to late/post-pubertal (0.109; 0.034 to 0.184 Nm/kg) but no statistically significant change from pubertal to late/post-pubertal (0.038; -0.028 to 0.103 Nm/kg. Likewise, pairwise comparison tests indicated a statistically significant drop in hip strength from pre-pubertal to pubertal (0.171; 0.069 to 0.272 Nm/kg) and from pre-pubertal to late/post-pubertal (0.290; 0.119 to 0.461 Nm/kg) but no significant change in hip strength was observed from pubertal to post-pubertal (0.119; -0.21 to 0.260 Nm/kg).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the longitudinal trajectories of lower extremity strength normalized to body mass across maturational stages for a cohort of female adolescent student-athletes. It was hypothesized that as subjects progressed from pre-pubertal to pubertal and late/post-pubertal levels, deficits in strength relative to body mass would emerge. The results from the current study provide evidence that while knee extension strength relative to body mass steadily increases throughout maturation, knee flexor strength remains about the same. This leads to an increased imbalance in hamstring-to-quadriceps strength. The results from the current study also indicate that female adolescents may experience a significant regression in hip abduction strength relative to body mass in the year they transition from pre-pubertal to pubertal status. Collectively, these results indicate that imbalances in lower extremity activation and strength relative to body mass emerge during puberty for female athletes.

PFP is a painful condition that peaks in incidence during the middle school years3 and eventually affects nearly 1 out of 4 school-aged youth.32 Likewise, ACL injuries in females have higher rates following the onset of the pubertal growth spurt.2 Although ACL injuries and the emergence of PFP increase for both males and females around the time of puberty, females sustain ACL injuries and experience PFP at least 4 to 6 times more frequently4-6 and are affected by PFP 2 to 10 times more often than their male counterparts.7,8 Altered or reduced control of the limbs during physical activities may result in excessive knee abduction joint loads in females. This neuromuscular dysfunction appears to increase risk of acute ACL injury and chronic PFP in females.3,25,33,34 Deficits and imbalances in lower extremity strength have also been linked to both ACL injury and PFP.3,25,28,32 The timing of the emergence of these deficits appears to coincide with the emergence of strength imbalances for female adolescents during puberty. Thus, the results of this study may provide a potential explanation for the timing of increased incidences of PFP and ACL injury observed in female adolescents.

The rapid increases in height and body weight adolescents experience during puberty have led to many hypotheses that link pubertal maturation to concomitant decreases in motor control and subsequently increased risk for sports and recreation-related injuries. However, past studies related to these hypotheses have yielded inconsistent results. For example, Davies and Rose23 found no evidence for impaired coordination during puberty, while Loko et al.,35 found that female adolescents exhibited plateaus and regressions in a number of motor abilities. Findings from a recent systematic review indicate that many of the inconsistencies in our understanding of the relationship between maturation and motor control abilities may relate to a number of methodological limitations and incongruities.36 For example, a number of previous studies have used motor skill performances (e.g., throwing distance and accuracy, vertical jump, running speed, etc.) as measures of motor control.23,35,37 However, the use of motor skill performances as indicators of motor control abilities can be problematic because skill performance levels can be strongly influenced by confounding variables such as experience and type of measurement. Other common limitations in studies on maturation and motor control include: operational definitions of maturation groups based on chronological age groupings, the combination of males and females within a single subject pool, and a lack of longitudinal follow-ups on subjects across the pubertal process. These types of operational definitions and subject pooling strategies can mask progression and regression trends because of the wide variability in maturational status of adolescent children of the same chronological age and potential sex-specific disparities.18,19,38-41

To address limitations in previous studies, the current study incorporated several important design features: 1) motor control variables related to neuromuscular strength rather than motor skill variables were used, 2) multiple potential confounding sex-specific disparities were accounted for through the inclusion of only females, 3) pubertal stages were used instead of chronological age groups to minimize error due to the wide variability in age at onset of puberty, and 4) longitudinal follow-ups that covered a single group of subjects across multiple pubertal stages were used for analyses instead of cross-sectional data. The longitudinal nature of the design and use of pubertal stages were particularly useful for identifying specific points in the maturation process where strength deficits might be expected to emerge. For example, hip abductor strength appears to undergo a fairly rapid change relative to body mass during the year when females transition from pre-pubertal to pubertal status. Imbalances between hamstrings and quadriceps strength, on the other hand, appear to emerge more gradually over the 3-year period leading from pre-pubertal to late/post-pubertal status.

The results from this study and other studies indicate that a potential window of opportunity may exist for the optimal initiation of integrative neuromuscular training based on measures of somatic maturity. Specifically, the most beneficial and thus desirable time to initiate integrative training programs may be during pre-adolescence prior to the period of obvious pubertal maturation when youth are growing most rapidly. Children with earlier somatic maturation (growth) may particularly benefit from earlier participation in integrative neuromuscular strength training.14,42 In a recent longitudinal study, Ford and colleagues noted that pubertal females had an increased change in abnormal landing mechanics over time.19 In addition, important contributing risk factors for knee injury were significantly greater across consecutive years in young post-pubertal female athletes compared to males. Integrative neuromuscular training programs have been successful at reducing these abnormal biomechanics43-46 and appear to decrease PFP and ACL injury rates in female athletes.47,48

One limitation of this study is that all of the subjects in this study were females. There is evidence to suggest that males and females may differ in the strength and neuromuscular control abilities that are present during puberty.20,49-52 In addition, the longitudinal nature of this study may have been limited by the nature of the design in that the subjects with data that were available for 3 consecutive years were all athletes that made the school team for multiple years. Therefore, future studies should include males as well as non-athletes in order to determine the generalizability of these results beyond female adolescent athletes.

Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that hip strength deficits and imbalances between hamstrings and quadriceps strength appear to emerge during pubertal maturation. As these strength variables have been linked to increased risk for ACL injury and PFP, these data provide further support that pre-adolescence may be an optimal time to institute programs aiming to reduce deficits (e.g., increased knee abduction motion and load) that accelerate during maturation and lead to increased musculoskeletal injury risk in female adolescents.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Mark Paterno, Dr. Carmen Quatman, Dr. Laura Schmitt, Chad Cherny, Jensen Brent, Kim Foss, and Staci Thomas for their assistance with data collection and other aspects of the study.

Grant Support: The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AR04973505-01, R01 AR055563-02, and R03-AR057551.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: There are no potential conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr Catherine C. Quatman-Yates, Sports Medicine Biodynamics Center and Human Performance Laboratory, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Division of Occupational and Physical Therapy, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dr Gregory D. Myer, Sports Medicine Biodynamics Center and Human Performance Laboratory, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Division of Molecular Cardiovascular Biology, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dr Kevin R. Ford, Sports Medicine Biodynamics Center and Human Performance Laboratory, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Division of Molecular Cardiovascular Biology, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dr Timothy E. Hewett, Sports Medicine Biodynamics Center and Human Performance Laboratory, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Division of Molecular Cardiovascular Biology, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; Departments of Pediatrics and Orthopaedic Surgery, College of Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio; Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Allied Health Sciences, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio; Departments of Physiology and Cell Biology, School of Biomedical Science, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio; Sports Medicine Center, Orthopaedic Surgery and Biomedical Engineering and Sports Health Institute, Cincinnati Children's Research Foundation, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

References

- 1.Myer GD, Ford KR, Divine JG, Wall EJ, Kahanov L, Hewett TE. Longitudinal assessment of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury risk factors during maturation in a female athlete: a case report. J Athl Train. 2009 Jan-Feb;44(1):101–109. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tursz A, Crost M. Sports-related injuries in children. A study of their characteristics, frequency, and severity, with comparison to other types of accidental injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1986 Jul-Aug;14(4):294–299. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myer GD, Ford KR, Barber Foss KD, et al. The incidence and potential pathomechanics of patellofemoral pain in female athletes. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2010 Aug;25(7):700–707. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arendt E, Dick R. Knee injury patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer. NCAA data and review of literature. Am J Sports Med. 1995 Nov-Dec;23(6):694–701. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeHaven KE, Lintner DM. Athletic injuries: comparison by age, sport, and gender. Am J Sports Med. 1986 May-Jun;14(3):218–224. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ireland ML. Anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: epidemiology. J Athl Train. 1999 Apr;34(2):150–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulkerson JP, Arendt EA. Anterior knee pain in females. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000 Mar;(372):69–73. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulkerson JP. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with patellofemoral pain. Am J Sports Med. 2002 May-Jun;30(3):447–456. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300032501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blond L, Hansen L. Patellofemoral pain syndrome in athletes: a 5.7-year retrospective follow-up study of 250 athletes. Acta Orthop Belg. 1998 Dec;64(4):393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical Measures During Landing and Postural Stability Predict Second Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Aug 11; doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scanlan SF, Chaudhari AM, Dyrby CO, Andriacchi TP. Differences in tibial rotation during walking in ACL reconstructed and healthy contralateral knees. J Biomech. 2010 Jun 18;43(9):1817–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Utting MR, Davies G, Newman JH. Is anterior knee pain a predisposing factor to patellofemoral osteoarthritis? Knee. 2005 Oct;12(5):362–365. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andriacchi TP, Koo S, Scanlan SF. Gait mechanics influence healthy cartilage morphology and osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Feb;91(1):95–101. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, Hewett TE. When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011 May-Jun;10(3):155–166. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31821b1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Myer GD. Exercise Deficit Disorder in Youth: A Hidden Truth. Acta Paediatr. 2011 Sep 6; doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Decrease in neuromuscular control about the knee with maturation in female athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004 Aug;86-A(8):1601–1608. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200408000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quatman CE, Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Maturation leads to gender differences in landing force and vertical jump performance: a longitudinal study. Am J Sports Med. 2006 May;34(5):806–813. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Longitudinal effects of maturation on lower extremity joint stiffness in adolescent athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Sep;38(9):1829–1837. doi: 10.1177/0363546510367425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford KR, Shapiro R, Myer GD, Van Den Bogert AJ, Hewett TE. Longitudinal sex differences during landing in knee abduction in young athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Oct;42(10):1923–1931. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc99b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford KR, Myer GD, Toms HE, Hewett TE. Gender differences in the kinematics of unanticipated cutting in young athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005 Jan;37(1):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD, Wanstrath K, Scheper M. Gender differences in hip adduction motion and torque during a single-leg agility maneuver. J Orthop Res. 2006 Mar;24(3):416–421. doi: 10.1002/jor.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petersen AC, Tobin-Richards M, Boxer A. Puberty: Its Measurement and its Meaning. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1983;3:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies PL, Rose JD. Motor skills of typically developing adolescents: awkwardness or improvement? Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2000;20(1):19–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quatman CE, Ford KR, Myer GD, Paterno MV, Hewett TE. The effects of gender and pubertal status on generalized joint laxity in young athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2008 Jun;11(3):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myer GD, Ford KR, Barber Foss KD, Liu C, Nick TG, Hewett TE. The relationship of hamstrings and quadriceps strength to anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2009 Jan;19(1):3–8. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318190bddb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLean SG, Huang X, Su A, Van den Bogert AJ. Transactions of the Orthopaedic Research Society. Washington DC; 2005. Neuromuscular Control Contributions to Non-contact ACL Injury. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLean SG, Huang X, van den Bogert AJ. Investigating isolated neuromuscular control contributions to non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injury risk via computer simulation methods. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2008 Aug;23(7):926–936. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Zazulak BT. Hamstrings to quadriceps peak torque ratios diverge between sexes with increasing isokinetic angular velocity. J Sci Med Sport. 2008 Sep;11(5):452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brent JL, Myer GD, Ford KR, Hewett TE. A Longitudinal Examination of Hip Abduction Strength in Adolescent Males and Females. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;39(5) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myer GD, Brent JL, Ford KR, Hewett TE. A pilot study to determine the effect of trunk and hip focused neuromuscular training on hip and knee isokinetic strength. Br J Sports Med. 2008 Jul;42(7):614–619. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2007.046086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brent J, Myer GD, Ford KR, Paterno M, Hewett T. The Effect of Sex and Age on Isokinetic Hip Abduction Torques. J Sport Rehabil. 2012 Jun 18; doi: 10.1123/jsr.22.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB, van Poortvliet JA, Phillips H. Mechanical factors in the incidence of knee pain in adolescents and young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984 Nov;66(5):685–693. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B5.6501361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005 Apr;33(4):492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 1, mechanisms and risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2006 Feb;34(2):299–311. doi: 10.1177/0363546505284183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loko J, Aule R, Sikkut T, Ereline J, Viru A. Motor performance status in 10 to 17-year-old Estonian girls. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000 Apr;10(2):109–113. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2000.010002109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quatman-Yates CC, Quatman CE, Meszaros AJ, Paterno M, Hewett T. A Systematic Review of Sensorimotor Function During Adolescence: A Developmental Stage of Increased Motor Awkwardness? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079616. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beunen G, Malina R, Van't Hof M, et al. Adolescent Growth and Motor Performance: A Longitudinal Study of Belgian Boys. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundermier L, Woollacott M, Roncesvalles N, Jensen J. The development of balance control in children: comparisons of EMG and kinetic variables and chronological and developmental groupings. Exp Brain Res. 2001 Feb;136(3):340–350. doi: 10.1007/s002210000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Largo RH, Caflisch JA, Hug F, et al. Neuromotor development from 5 to 18 years. Part 1: timed performance. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001 Jul;43(7):436–443. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201000810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Largo RH, Fischer JE, Rousson V. Neuromotor development from kindergarten age to adolescence: developmental course and variability. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003 Apr 5;133(13-14):193–199. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.09883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirshenbaum N, Riach CL, Starkes JL. Non-linear development of postural control and strategy use in young children: a longitudinal study. Exp Brain Res. 2001 Oct;140(4):420–431. doi: 10.1007/s002210100835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Chu DA, et al. Integrative training for children and adolescents: techniques and practices for reducing sports-related injuries and enhancing athletic performance. Phys Sportsmed. 2011 Feb;39(1):74–84. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.02.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myer GD, Ford KR, Palumbo JP, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Feb;19(1):51–60. doi: 10.1519/13643.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myer GD, Ford KR, McLean SG, Hewett TE. The Effects of Plyometric Versus Dynamic Stabilization and Balance Training on Lower Extremity Biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(3):490–498. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, Hewett TE. Differential neuromuscular training effects on ACL injury risk factors in “high-risk” versus “low-risk” athletes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8(39):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hewett TE, Stroupe AL, Nance TA, Noyes FR. Plyometric training in female athletes. Decreased impact forces and increased hamstring torques. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(6):765–773. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sugimoto D, Myer GD, Bush HM, Klugman MF, Mckeon JM, Hewett TE. Effect of Compliance with Neuromuscular Training on ACL Injury Risk Reduction in Female Athletes: A Meta-Analysis. J Athl Train. 2011 doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.10. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.LaBella CR, Huxford MR, Smith TL, Cartland J. Preseason neuromuscular exercise program reduces sports-related knee pain in female adolescent athletes. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2009 Apr;48(3):327–330. doi: 10.1177/0009922808323903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Longitudinal Effects of Maturation on Lower Extremity Joint Stiffness in Adolescent Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Jun 3; doi: 10.1177/0363546510367425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ford KR, Myer GD, Hewett TE. Valgus knee motion during landing in high school female and male basketball players. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Oct;35(10):1745–1750. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000089346.85744.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ford KR, Myer GD, Smith RL, Vianello RM, Seiwert SL, Hewett TE. A comparison of dynamic coronal plane excursion between matched male and female athletes when performing single leg landings. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006 Jan;21(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ford KR, Shapiro R, Myer GD, van den Bogert AJ, Hewett TE. Longitudinal Sex Differences during Landing in Knee Abduction in Young Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Mar 16; doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181dc99b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]