Abstract

Objective

To investigate participation patterns in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) among low-income children from kindergarten to fifth grade and to examine the ways in which participation influences gender differences in BMI trajectories through the eighth grade.

Design

Longitudinal, secondary data analysis

Setting

Sample of low-income US children who entered kindergarten in 1998.

Participants

Low-income girls (n = 574) and boys (n = 566) who participated in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Cohort.

Main Exposure

Participation in the NSLP

Main Outcome Measures

Temporary and persistent patterns of NSLP participation. Age- and sex-specific body mass index (BMI) raw scores were calculated at five data points.

Results

Among low-income children who attended schools that participated in the NLSP, children who persistently and temporarily participated in the NSLP displayed similar, economically-disadvantaged factors. Non-linear mixed models indicated a larger rate of change in BMI growth among low-income participating girls compared to low-income non-participating girls; however, average levels of BMI did not significantly differ between low-income participating and non-participating girls. No significant differences were observed among low-income boys.

Conclusions

Results suggest participation in the NSLP is associated with rapid weight gain for low-income girls but not for low-income boys.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 36% of U.S. children ages 6 to 11 years were classified as overweight, while almost approximately 20% were considered obese in 2007–2008.1 The prevalence of obesity among U. S. children and adolescents ages 10 to 17 years of age increased by 10% between 2003 and 2007. During the same time period, the prevalence of obesity among girls increased approximately 18%.2 Pediatric obesity has been associated with Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, several types of cancer, and hypertension, especially when tracked into adulthood.3 Obesity among female youth has been associated with early puberty,4–6 and early puberty among females has been linked to unfavorable body image,7,8 eating problems,9 depression,10 earlier onset of sexual intercourse,11 and breast cancer as adult women.12–15

Policymakers and researchers are focusing on school settings and the food they provide as a possible mechanism to reduce childhood obesity. The National School Lunch Program (NSLP) was established in 1946 as an intervention and prevention program intended to mitigate malnutrition and promote healthy development during school by providing a nutritional safety net for low-income children. The NSLP increases the availability of food and protein and is associated with lower intakes of added sugars and an increased intake of vitamins and minerals.16,17 Although the NSLP was not originally designed as an obesity prevention program, it has undergone criticism for contributing to an increase in dietary fat and calories among children who participate in the program.17–19

Whether the NSLP is contributing to the obesity epidemic is largely inconclusive, and it is unknown whether NSLP participation influences girls and boys relative weight status differently. Using cross-sectional data on students from grade 1 through 12, Gleason and Dodd20 found that participation in the NSLP was not related to students’ body mass index (BMI). However, findings based on longitudinal data differ. Using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey – Kindergarten (ECLS-K), Schanzenbach19 found that by the end of first grade, children eligible for free or reduced-price lunches weighed more and were more likely obese compared to children right above and below the income-eligible cut-off, despite entering kindergarten with the same BMI and obesity rates. Millimet, Tchernis, and Husain,21 also employed the ECLS-K and found a positive association between participation in the NSLP at kindergarten and child weight at third grade. Yet, the above longitudinal studies do not make a distinction as to whether gender moderates the positive association between NSLP participation and child BMI.

Further, there are no known published studies on the patterns of NSLP participation among low-income children and its association with gender differences in BMI trajectories. Limited research on the patterns of food assistance program participation has been conducted on participation in the Food Stamp Program (FSP) among adult samples. Baum’s22 findings suggest a positive association between persistent participation and overweight/obesity in adult females and males, while Gibson23 found this association only in adult females. In a study of adolescents ages 12–14, Gibson24 reported that long-term participation to have a positive influence on young girls’ weight gain, but a negative influence on young boys’ weight status. By examining participation patterns in the NSLP, the present study observes whether persistent participation in the NSLP has a cumulative positive effect on child and early adolescent weight status, just like the FSP has had on adolescent girls24 and adult women.22 The positive association could further inform research on the precursors to obesity.

Building upon recent NSLP studies19,21 and studies that have focused on longitudinal participation patterns,22–24 the present study focuses on low-income children to examine (1) participation patterns (i.e. persistent, transient, and no participation) in the NSLP from kindergarten to fifth grade, (2) how NSLP participation relates to BMI trajectories through eighth grade, and (3) whether NSLP participation influences gender differences in BMI trajectories. It is hypothesized that among low-income children, those who persistently participate in the NSLP will display more socioeconomic disadvantaged characteristics than children who temporarily or never participate. In addition, it is hypothesized that the pattern in which individuals participate in the NSLP may influence BMI, with the NSLP having a positive, cumulative effect on relative weight status among individuals who persistently participate. Based on work by Gibson24, it is hypothesized that participation in the NSLP will positively influence girls’ BMI trajectories and negatively influence boys’ trajectories.

METHODS

Data Set

Data are drawn from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS-K), a nationally-representative, longitudinal study of children’s school experiences and development collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). A total of 21,260 children were first assessed in kindergarten from 1,280 public and private schools. The ECLS-K follows children in the fall and spring of kindergarten (1998–1999), the fall and spring of 1st grade (1999–2000), the spring of 3rd grade (2002), 5th grade (2004), and 8th grade (2007). For the purposes of consistency, we focus on data collected in the spring term of each grade listed. Further information on sampling, recruitment, and attrition can be found at http://nces.ed.gov/ecls/kindergarten.asp. The Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution approved the study described in this article.

Analysis Sample

The analysis sample consists of 1,140 low-income students. The analysis sample was selected based on those children who were interviewed through eighth grade (n=9,725). The sample was further restricted to students who attended schools who participated in the NSLP (3916 excluded) and who were income-eligible to participate in the program at kindergarten [<= 185% of Federal Poverty Line (FPL)] (3407 excluded). Children that never responded to school lunch program participation questions were not included in the analysis sample (4 excluded). Last, children who had missing information on the covariates were dropped from the final analysis sample (800 excluded).

Mean differences were conducted between the children included in the analysis sample and the children excluded due to missing data on the covariates (e.g., see eTable 1). The children included in the final analyses were less likely to have persistently participated in the NSLP and more likely to have temporarily participated or have never participated compared to children in the excluded sample. Children included in the analysis were less likely to be non-Hispanic Black and other race and more likely to be non-Hispanic White compared to children in the excluded sample. The analysis sample also included children who were less likely to attend Head Start and watched fewer hours of television per day compared to children excluded from the analysis sample. Children in the included sample lived with mothers who were more likely to be married, more likely to have a high school education, and less likely to be employed full time compared to children excluded from the analysis sample. Included children in the analysis lived in households that earned $20,000 or more, and in households where families ate more breakfast meals together. Included children also displayed significantly lower measures of BMI at 8th grade compared to children excluded from the sample.

Outcome Variable

Child Weight Status

Children’s BMI indices were calculated from direct measurement of height and weight collected at each time point. Height was measured in duplicate using a standing height board, and weight was also measured in duplicate using a digital bathroom scale (Shorr Products; Olney, MD). The average of the two measures was used to calculate age- and sex-specific BMI based on national reference criteria outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.25

Independent Variable

Participation in the National School Lunch Program

At each data collection point, parents were asked to indicate whether their child receives free or reduced price lunches at school. Using this information, we created four dichotomous variables indicating the child participated in the school lunch program during kindergarten, 1st grade, 3rd grade, and 5th grade. We decided to focus on NLSP participation during the elementary school years because the available school lunch options are qualitatively different in elementary school compared to middle and high school.

Three mutually exclusive variables that capture the consistency of participation in the NSLP were also created: no participation, persistent participation, transient participation. Children who never participated in the NSLP at any of the four time points comprised the no participation group. Children who participated in the NSLP at all four time points comprised the persistent participation group. Children who participated at some grade levels but not in others comprised the transient participation group.

Control Variables

Factors capturing child, maternal, and household characteristics that are related to program participation and relative weight status were included in our models as control variables (e.g, see eTable 2). A sedentary lifestyle and higher levels of television viewing have been associated with overweight and obesity26,27; while full-day Head Start attendance is associated with a reduction in the proportion of children who are classified as obese.28 Thus, measures of physical activity, television viewing habits, and Head Start attendance were included in the analyses. Physical activity was measured as the average days per week the child received 20 minutes of exercise; while television viewing was captured as the average hours a child watched television per day. Family meals, captured in two separate variables as the number of times a family eats (1) breakfast and (2) dinner are included, as research on children and adolescents has found a protective effect of eating breakfast regularly29–31 and family dinner32,33 on overweight. Given that income can be volatile over time and this may influence eligibility in the NSLP, we included three variables indicating income eligibility in the NSLP (<= 185% of FPL) at first, third, and fifth grade. State-level contextual variables are included as they are related to program participation and may be related to relative weight status.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive analysis and poisson regression models were conducted in STATA 10.1.34 To answer the first research question of what characteristics predict children experiencing persistent and transient participation, incidence risk ratios were estimated using poisson regression models. The Huber-White sandwich variance estimator was included in the regression models to account for the fact that the outcome is binary. The regression models resulted in two comparisons being made: (1) a comparison of children who persistently participated in the NSLP to those who did not persistently participate (i.e. persistent participants vs. transient participants and non-participants); and (2) a comparison of children who persistently participated in the NSLP to children who temporarily participated in the NSLP (i.e. persistent participants vs. transient participants). The control variables outlined in eTable 2 were included in all of these models. While we include a rich set of covariates in our models, we acknowledge that participants in the NSLP are different than those who do not participate and the results from this model may be capturing some unobservable differences between these two groups and not mitigation by the program.

Non-linear mixed models (SAS 9.2; Proc MIXED) were used to examine the association between NSLP participation on childhood BMI trajectories for the full sample and separately by gender. Main effects of time (i.e. slope), NSLP participation, and NSLP participation by time interaction were tested in this model. A significant NSLP participation main effect suggests that the level of BMI differs at that particular time point for children participating in the NSLP compared to children who do not participate in the NSLP; while a significant interaction effect provides evidence for a differential rate of change in relative weight over time for children participating in the NSLP compared to children who do not participate in the NSLP. For all mixed models, non-linearity was further tested by including age-squared, age-cubed, and gender by age interactions terms. However, these terms were non-significant, worsened the overall model fit, and thus were excluded from the final models. All models included quadratic and cubic terms for the slope in order to create the best fitting model for the data; because the terms do not add theoretic meaning to the results, they are not included in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mixed models examining NSLP participation on childhood BMI trajectoriesa

| Kindergartenb | First Gradeb | Third Gradeb | Fifth Gradeb | Eighth Gradeb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Full Sample (n=1140) d | |||||

| Intercept | 14.30 (1.54)c | 14.83 (1.54)c | 16.53 (1.55)c | 18.56 (1.56)c | 20.93 (1.60)c |

| Linear Slope | 0.39 (0.07)c | 0.66 (0.05)c | 0.98 (0.05)c | 1.00 (0.05)c | 0.47 (0.10)c |

| Participation in NSLP | 0.12 (0.23) | 0.20 (0.25) | 0.36 (0.31) | 0.52 (0.39) | 0.76 (0.52) |

| Linear Slope x Participation in NSLP | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.05) |

| Girls (n=574) e | |||||

| Intercept | 13.10 (2.26)c | 13.64 (2.27)c | 15.20 (2.28)c | 17.08 (2.31)c | 19.68 (2.36) c |

| Linear Slope | 0.44 (0.11)c | 0.63 (0.08)c | 0.89 (0.07)c | 0.96 (0.07)c | 0.71 (0.17) c |

| Participation in NSLP | −0.18 (0.35) | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.33 (0.48) | 0.66 (0.59) | 1.16 (0.79) |

| Linear Slope x Participation in NSLP | 0.17 (0.07)c | 0.17 (0.07)c | 0.17 (0.07)c | 0.17 (0.07)c | 0.17 (0.07)c |

| Boys (n=566) f | |||||

| Intercept | 16.31 (2.11)c | 16.83 (2.11)c | 18.67 (2.12)c | 20.86 (2.14)c | 23.01 (2.17)c |

| Linear Slope | 0.34 (0.09)c | 0.69 (0.07)c | 1.08 (0.06)c | 1.05 (0.06)c | 0.23 (0.10)c |

| Participation in NSLP | 0.42 (0.30) | 0.40 (0.32) | 0.36 (0.39) | 0.32 (0.48) | 0.27 (0.63) |

| Linear Slope x Participation in NSLP | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.06) | −0.02 (0.06) |

Abbreviation: NSLP, National School Lunch Program.

Control variables listed in Table 2 are included in addition to quadratic and cubic slopes.

Indicates location of the intercept.

Statistically different from 0, p < 0.05.

The -2 Log Likelihood for these models is 24022.4 and the AIC is 24044.4.

The -2 Log Likelihood for these models is 12363.5 and the AIC is 12385.5.

The -2 Log Likelihood for these models is 11442.0 and the AIC is 11464.0.

RESULTS

Patterns of Participation

Eighty-two percent of the low-income children (35% persistent; 47% transient) participated in the NSLP at some point during kindergarten to fifth grade (Table 1), with transient children participating on average 3 of the possible 4 times (results not shown). There are few statistically significant differences in BMI percentiles at each grade level between children who participated in the NSLP from those did not. Descriptive statistics by participation patterns demonstrate that low-income children who persistently and temporarily participate in the NSLP were more socioeconomically disadvantaged than those who were low income but never participated. In addition, bivariate statistics demonstrated that children who persistently participated in the NSLP were at a greater disadvantaged socio-economically compared to children who participated in an inconsistent basis; however, both groups shared similar disadvantaged characteristics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics for the Full Sample and by Consistency of NSLP Participation

| Lunch Participation

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Full Sample (N = 1140) | Persistent (n = 397) | Transient (n = 532) | Never (n = 211) |

|

|

|

|||

| Lunch Participation | ||||

| Persistent Participation, No. (%) | 397 (35) | 397 (100) | --- | --- |

| Transient Participation, No. (%) | 532 (47) | --- | 532 (100) | --- |

| Never Participation, No. (%) | 211 (19) | --- | --- | 211 (100) |

| Body Mass Index (percentile) | ||||

| Kindergarten, No. (%) | 63.26 (28.00) | 62.95 (27.72) | 63.67 (28.71) | 62.79 (26.81) |

| First Grade, No. (%) | 62.09 (29.75) | 61.09 (30.61) | 62.90 (29.76) | 61.91 (28.14) |

| Third Grade, No. (%) | 66.56 (28.76) | 66.10 (28.36) | 67.60 (29.59)a | 64.84 (27.41) |

| Fifth Grade, No. (%) | 69.42 (28.73) | 68.79 (28.78) | 71.27 (28.60) | 66.06 (28.71) |

| Eighth Grade, No. (%) | 69.81 (27.29) | 68.20 (28.23) | 71.43 (26.72) | 69.10 (26.76) |

| Child Characteristics, No. (%) | ||||

| Child age, mean (SD), y | 6.24 (0.36) | 6.23 (0.37) | 6.23 (0.35) | 6.26 (0.35) |

| Child is male, No. (%) | 570 (50) | 191 (48)a | 255 (48)a | 118 (56) |

| Non-Hispanic White, No. (%) | 616 (54) | 131 (33)c | 303 (57)c,z | 175 (83) |

| Non-Hispanic Black, No. (%) | 137 (12) | 79 (20)c | 53 (10)c,z | 4 (02) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 274 (24) | 143 (36)c | 122 (23)c,z | 15 (07) |

| Other race, No. (%) | 114 (10) | 44 (11) | 53 (10) | 15 (07) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), ounces | 117.69 (22.51) | 115.09 (24.24)b | 118.39 (21.68)x | 120.82 (20.67) |

| Premature birth, No. (%) | 182 (16) | 71 (18) | 85 (16) | 32 (15) |

| Head Start, No. (%) | 296 (26) | 163 (41)c | 122 (23)c,z | 15 (07) |

| Average hours of TV viewing, mean (SD), day | 1.01 (0.60) | 1.09 (0.68)b | 0.99 (0.57)x | 0.94 (0.48) |

| Average 20 min exercise, mean (SD), days/wk | 4.00 (2.36) | 4.03 (2.54) | 3.99 (2.87) | 3.89 (2.18) |

| Mother Characteristics | ||||

| Teenage mom at birth, No. (%) | 103 (09) | 40 (10) | 59 (11) | 13 (06) |

| Married, No. (%) | 844 (74) | 266 (67)c | 399 (75)c,y | 184 (87) |

| Less High School, No. (%) | 251 (22) | 135 (34)c | 106 (20)c,z | 11 (05) |

| Full Time Employment, No. (%) | 410 (36) | 155 (39) | 186 (35) | 78 (37) |

| Household Characteristics | ||||

| Income <= $20,000, No. (%) | 422 (37) | 206 (52)c | 181 (34)c,z | 38 (18) |

| Income $20,001 – $40,000, No. (%) | 661 (58) | 179 (45)c | 330 (62)b,z | 156 (74) |

| Income >= $40,001, No. (%) | 46 (04) | 12 (03)a | 21 (04) | 17 (08) |

| Income <= 185% FPL at 1st grade, No. (%) | 855 (75) | 365 (92)c | 404 (76)c,z | 84 (40) |

| Income <= 185% FPL at 3rd grade, No. (%) | 787 (69) | 345 (87)c | 356 (67)c,z | 80 (38) |

| Income <= 185% FPL at 5th grade, No. (%) | 730 (64) | 333 (84)c | 335 (63)c,z | 59 (28) |

| Number of children in household, mean (SD) | 2.94 (1.34) | 3.10 (1.43)c | 2.97 (1.36)c | 2.55 (0.97) |

| Family eats breakfast together, mean (SD), days/wk | 4.16 (2.49) | 3.61 (2.43)c | 4.34 (2.45)a,z | 4.75 (2.52) |

| Family eats dinner together, mean (SD), days/wk | 5.88 (1.71) | 5.99 (1.68)b | 5.93 (1.67)b | 5.56 (1.82) |

| State-level Characteristics | ||||

| Percentage of NSLP participants, mean (SD) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.02)c | 0.10 (0.02)z | 0.10 (0.02) |

| Unemployment rate, mean (SD) | 5.39 (0.83) | 5.49 (0.83)a | 5.33 (0.84)y | 5.35 (0.77) |

Abbreviations: TV, television; min, minute; FPL, Federal Poverty Line; NSLP, National School Lunch Program.

Significantly different from never participated, p < 0.05.

Significantly different from never participated, p < 0.01.

Significantly different from never participated, p < 0.001.

Significantly different from persistently participated, p < 0.05.

Significantly different from persistently participated, p < 0.01.

Significantly different from persistently participated, p < 0.001.

Poisson regression models further confirm the association between disadvantaged characteristics and NSLP persistent and transient participants (Table 2). Column 1 compares children who persistently participate to those who do not persistently participate (i.e. transient participants and non-participants). Low-income non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children compared to low-income non-Hispanic White children were 39% and 79% respectively more likely to persistently participate in the NSLP compared to not persistently participating. Children who participated in Head Start are 19% more likely to persistently participate in the NSLP compared to children who did not participate in Head Start. Children who on average watch greater hours of television per day are 9% more likely to persistently participate in the NSLP than not. Children whose mothers did not complete high school compared to mothers who did complete high school were 29% more likely to persistently participate in the program compared to not persistently participating. Children whose mothers are employed full time compared to children whose mothers are not employed full time are 16% more likely to persistently participate in the NSLP. Children who lived in households with incomes less than 185% of the FPL at 1st, 3rd, and 5th grade were approximately 1.5 to 2 times more likely to persistently participate in the program compared to not persistently participating. Children whose families eat breakfast together more frequently were 3% less likely to persistently participate. Children who lived in states with a greater percentage of NSLP participants were 12% more likely to persistently participate than not. In column 2, children who persistently participated in the NSLP are compared to children who transition in and out of the program. The results in column 2 are similar to those in column 1; however the size of the coefficients is smaller and/or less significant for some characteristics. This is expected as the sample in column two is smaller and more homogeneous. Thus, similar disadvantaged characteristics were associated with persistently and temporarily participating in the NSLP.

Table 2.

Risk of Persistently Participating in the NSLP

| Persistent vs. Non-persistent Participationa (N = 1140) | Persistent vs. Transient Participation (n = 942) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristics | IRR, (95% CI) | P Value | IRR, (95% CI) | P Value |

| Child Characteristics | ||||

| Child age, y | 1.01 (0.84–1.22) | .90 | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) | .95 |

| Child is male | 1.04 (0.90–1.19) | .61 | 1.07 (0.93–1.22) | .35 |

| Non-Hispanic White (reference) | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.39 (1.10–1.75) | .01 | 1.25 (1.01–1.56) | .04 |

| Hispanic | 1.79 (1.47–2.18) | .00 | 1.57 (1.29–1.89) | .00 |

| Other race | 1.26 (0.96–1.66) | .10 | 1.23 (0.94–1.60) | .13 |

| Birth weight, ounces | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | .33 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .35 |

| Premature birth | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | .83 | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | .82 |

| Head Start | 1.19 (1.03–1.18) | .02 | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | .05 |

| Average hours of TV viewing, day | 1.09 (0.99–1.20) | .08 | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | .08 |

| Average 20 min exercise, days/wk | 1.02 (0.98–1.04) | .32 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | .58 |

| Mother Characteristics | ||||

| Teenage mom at birth | 1.02 (0.80–1.31) | .88 | 0.97 (0.76–1.23) | .79 |

| Married | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | .39 | 0.97 (0.83–1.13) | .69 |

| Less High School | 1.29 (1.11–1.50) | .00 | 1.24 (1.07–1.44) | .00 |

| Full Time Employment | 1.16 (1.00–1.35) | .06 | 1.16 (1.00–1.34) | .05 |

| Household Characteristics | ||||

| Income <= $20,000 | 0.67 (0.41–1.10) | .11 | 0.71(0.45–1.13) | .15 |

| Income $20,001 – $40,000 | 0.57 (0.35–0.92) | .02 | 0.61 (0.39–0.97) | .04 |

| Income >= $40,001(reference) | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| Income <= 185% FPL at 1st grade | 2.07 (1.48–2.91) | .00 | 1.61 (1.17–2.21) | .00 |

| Income <= 185% FPL at 3rd grade | 1.55 (1.17–2.05) | .00 | 1.45 (1.17–1.88) | .01 |

| Income <= 185% FPL at 5th grade | 1.51 (1.17–1.95) | .00 | 1.34 (1.06–1.70) | .01 |

| Number of children in household | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | .15 | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | .47 |

| Family eats breakfast together, days/wk | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | .04 | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | .08 |

| Family eats dinner together, days/wk | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | .19 | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | .45 |

| State-level Characteristics | ||||

| Percentage of NSLP participants | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) | .00 | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | .00 |

| Unemployment rate | 1.09 (0.98–1.22) | .13 | 1.10 (0.99–1.23) | .07 |

Abbreviation: NSLP, National School Lunch Program; IRR, Incidence Risk Ratios; TV, television; min, minute; FPL, Federal Poverty Line.

Comparison group “non-persistent” includes “transient participants” and “non-participants.”

Participation and BMI Trajectories

Non-linear mixed models with the three program participation groups (never, persistent, and transient) were first conducted for the full sample. “Persistent” and “transient” participation groups were collapsed into one group representing “participants” for the all the analyses that follow given that (1) the mixed model including the three types of program participation categories suggested that the rate of change in BMI growth and the average BMI levels for those who persistently participated compared to those who transitioned in and out of the program did not statistically differ (results not shown), and (2) the poisson regression models in Table 2 indicated similar socioeconomic and demographic characteristics are associated with persistent and temporary participation. Results for the full sample indicated that low-income children who participated in the NLSP do not have statistically significant higher average BMI levels at each grade level compared to low-income children who never participate (Table 3 and eTable 3). Further, low-income children who participated in the program did not have statistically significant larger rates of change in BMI growth compared to low-income children who did not participate in the NSLP.

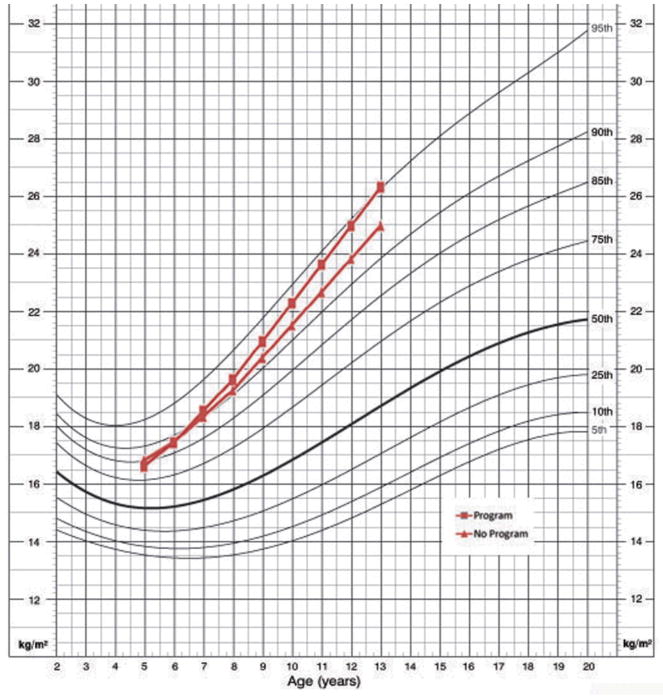

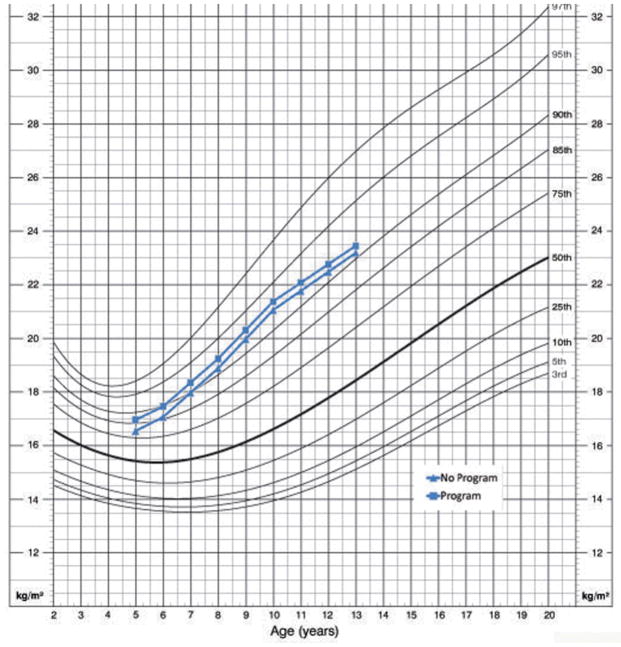

Non-linear mixed models conducted separately by gender revealed differences for girls and boys. Results indicated that low-income girls who participated in the NSLP had larger rates of change in BMI growth compared to low-income non-participating girls (Table 3 and Figure 1). However, average BMI levels at each school grade did not statistically differ between participating and non-participating low-income girls. Mixed models also suggested that low-income NSLP participating boys do not statistically differ in either their rate of change in BMI growth or in their average BMI levels compared to low-income NSLP non-participating boys (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Girls’ BMI trajectories from 5 to 13 years of age by program participation

Note: Trajectories include covariates. Trajectories are plotted on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth Chart, for girls.46

Figure 2.

Boys’ BMI trajectories from 5 to 13 years of age by program participation

Note: Trajectories include covariates. Trajectories are plotted on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Growth Chart, for boys.46

COMMENT

Focusing on low-income children, this study explored the patterns of participation in the NSLP, how participation influences childhood BMI trajectories, and investigated whether NSLP participation influences BMI trajectories differently for girls and boys. Given that the end goal of the NSLP is to improve the well-being of low income children, a longitudinal examination focused solely on the target population of the NSLP facilitates a greater understanding of who among the target population the program is serving over time and how participation is influencing health. Contrary to the hypothesis, results suggest that similar socio-economic disadvantaged characteristics are associated with persistently and temporarily participating in the NSLP. Thus, the longitudinal examination provides policymakers and social service providers with the knowledge base that families with comparable background characteristics are selecting into the program although their patterns of participation differ. There is still a limited understanding of why income-eligible families do not participate in the NSLP, and qualitative interviews on income-eligible non-participating families may clarify this.

Unlike Schanzenbach19 and Millimet et al.21, this study found no statistical significant association between participation and average relative weight level. This is likely due to the fact that the current study focused on a low-income sample, the target population of the NSLP; while the other studies focused on all school-age children regardless of their income status. The study does add new information on the extent to which relations between NSLP participation and BMI trajectories are moderated by gender. The results indicate that low-income NSLP participating girls display a faster rate of change in BMI over time compared to low-income girls who do not participate in the program. The results also indicate that NSLP participating boys’ BMI do not statistically differ from non-participating boys, which differs from the predicted hypothesis and previous food assistance research.24

Although the majority of low-income children on average enter kindergarten at a healthy weight, as they develop, the combination of biological and contextual factors may be contributing to the gender differences in the rate at which weight is gained. The current study suggests that low-income children who participate in the NSLP display living in greater socioeconomic disadvantaged environments compared to children who are income eligible but do not participate. Poor living conditions have also been associated with greater fast food restaurants in the area35,36 and fewer opportunities for physical activity37,38, which are correlates of obesity. Further, living in stressful environments has been associated with precocious puberty,39,40 with the onset of pubertal characteristics observed as early as age 8 for girls.41 While precocious puberty has not been observed in overweight boys, early breast development and menstruation have been observed in obese girls.4–6 This is because as girls transition to puberty they tend to lay down more adipose tissue, or body fat; while boys lay down more lean muscle. Thus, the poor living conditions experienced by the girls who participate in the NSLP may interact with biological changes, resulting in their rate of BMI growth to differ from girls who do not participate in the program.

Overall, low-income children participating in the NSLP display similar disadvantaged socio-economic characteristics, despite different patterns of participation. Participation in the NSLP appears to be associated with the rate at which low-income girls gain weight compared to low-income girls who do not participate in program. While the current study includes a measure of physical activity and television viewing, the results should be interpreted carefully as the measures are based on recall methods which are subjected to social desirability bias.42–44 Although physical activity recall methods are feasible and an inexpensive approach compared to objective measures (e.g., accelerometers), previous research has indicated females tend to over-report their physical activity.42,43,45 The study also lacks information on dietary intake and consumption patterns during the school lunch period and outside the school environment, precluding us from examining the mechanisms by which these differences exist. Thus, it is unclear whether low-income children who are participating in the NSLP are actually consuming their lunch and/or consuming a la carte items. Future studies focusing on food assistance program participation and children’s BMI should include detailed information on the built environment, along with dietary intake, consumption patterns, and physical activity of income-eligible girls and boys using both dietary recall techniques and objective measures, such as physiological monitoring. Efforts to gain a better understanding of what children are consuming and how often children are consuming particular foods in relation to environmental stressors may provide important new best practices on creating healthier lunch options for all children.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was supported by US Department of Agriculture Research Innovation and Development Grants in Economics Program in partnership with the Department of Nutrition at the University of California-Davis to the first two authors. In addition, the project described was supported by Award Number K12HD055882 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh GK, Kogan MD, van Dyck PC. Changes in state-specific childhood obesity and overweight prevalence in the United States from 2003 to 2007. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):e1–e10. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deckelbaum RJ, Williams CL. Childhood obesity: The health issue. Obesity Res. 2001;9:239S–243S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biro F, Galvez M, Greenspan L, et al. Pubertal Assessment Method and Baseline Characteristics in a Mixed Longitudinal Study of Girls. Prediatrics. 2010;126(3):e583–e590. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplowitz P, Slora E, Wasserman R, Pedlow S, Herman-Giddens M. Earlier onset of puberty in girls: relation to increased body mass index and race. Prediatrics. 2001;108(2):347–353. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y. Is obesity associated with early sexual maturation? A comparison of the association in American boys versus girls. Prediatrics. 2002;110(5):903–910. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Striegel-Moore RH, McMahon RP, Biro FM, Schreiber G, Crawford PB, Voorhees C. Exploring the relationship between timing of menarche and eating disorder symptoms in Black and White adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30(4):421–433. doi: 10.1002/eat.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(2):155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swarr AE, Richards MH. Longitudinal effects of adolescent girls’ pubertal development, perceptions of pubertal timing, and parental relations on eating problems. Dev Psychol. 1996;32(4):636–646. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(3):404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French DC, Dishion TJ. Predictors of early initiation of sexual intercourse among high-risk adolescents. J Early Adolesc. 2003;23(3):295–315. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garland M, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Menstrual cycle characteristics and history of ovulatory infertility in relation to breast cancer risk in a large cohort of US women. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(7):636–643. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okasha M, McCarron P, Gunnell D, Davey Smith G. Exposures in childhood, adolescence and early adulthood and breast cancer risk: a systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;78(2):223–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1022988918755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petridou E, Syrigou E, Toupadaki N, Zavitsanos X, Willett W, Trichopoulos D. Determinants of age at menarche as early life predictors of breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1996;68(2):193–198. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961009)68:2<193::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockhill B, Moorman P, Newman B. Age at menarche, time to regular cycling, and breast cancer (North Carolina, United States) Cancer Causes and Control. 1998;9(4):447–453. doi: 10.1023/a:1008832004211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gleason PM, Suitor CW. Eating at school: How the National School Lunch Program affects children’s diets. Am J Agric Econ. 2003;85(4):1047–1061. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon AR, Devaney BL, Burghardt JA. Dietary-effects of the National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(1):S221–S231. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.1.221S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burghardt JA, Gordon AR, Fraker TM. Meals offered in the National Schoool Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(1):S187–S198. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/61.1.187S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schanzenbach DW. Do school lunches contribute to childhood obesity? J Hum Resour. 2009;44(3):684–709. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gleason PM, Dodd AH. School Breakfast Program but Not School Lunch Program Participation Is Associated with Lower Body Mass Index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2):S118–S128. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millimet D, Tchernis R, Husain M. School Nutrition Programs and the Incidence of Childhood Obesity. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2008. NBER working paper no. 14297. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baum C. The Effects of Food Stamps on Obesity. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2007. Report no. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibson D. Food stamp program participation is positively related to obesity in low income women. J Nutr. 2003;133(7):225–231. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.7.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson D. Long-term food stamp program participation is differentially related to overweight in young girls and boys. J Nutr. 2004;134(2):372–379. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM. Criteria for definition of overweight in transition: background and recommendations for the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(5):1074–1081. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gable S, Chang Y, Krull JL. Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandewater EA, Shim MS, Caplovitz AG. Linking obesity and activity level with children’s television and video game use. J Adolesc. 2004;27(1):71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frisvold DE, Lumeng JC. Expanding exposure: Can increasing the daily duration of Head Start reduce childhood obesity? Atlanta, GA: Emory University March; 2010. Working Paper 09-06. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Affenito SG, Thompson DR, Barton BA, et al. Breakfast consumption by African-American and white adolescent girls correlates positively with calcium and fiber intake and negatively with body mass index. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(6):938–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barton BA, Eldridge AL, Thompson D, et al. The relationship of breakfast and cereal consumption to nutrient intake and body mass index: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(9):1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubois L, Girard M, Kent MP, Farmer A, Tatone-Tokuda F. Breakfast skipping is associated with differences in meal patterns, macronutrient intakes and overweight among pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(1):19–28. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008001894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen B. Frequency of family dinner and adolescent body weight status: Evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth, 1997. Obesity. 2006;14:2266–2276. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman S, Berkey CS, et al. Family dinner and adolescent overweight. Obesity Res. 2005;13(5):900–906. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statistical Software: Release 7.0 [computer program] College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Block J, Scribner R, DeSalvo K. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income:: A geographic analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ, Bao Y. The availability of fast-food and full-service restaurants in the United States: Associations with neighborhood characteristics. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4):S240–S245. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong T, Farley T. Urban residents’ priorities for neighborhood features. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):353–356. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X, Lee C. Walkability and safety around elementary schools: Economic and ethnic disparities. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(4):282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Dev. 1991;62(4):647–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moffitt T, Caspi A, Belsky J, Silva P. Childhood experience and the onset of menarche: A test of a sociobiological model. Child Dev. 1992;63(1):47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herman-Giddens M, Slora E, Wasserman R, et al. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: A study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Prediatrics. 1997;99(4):505. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams SA, Matthews CE, Ebbeling CB, et al. The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(4):389–398. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klesges LM, Baranowski T, Beech B, et al. Social desirability bias in self-reported dietary, physical activity and weight concerns measures in 8-to 10-year-old African-American girls: Results from the Girls Health Enrichment Multisite Studies (GEMS) Prev Med. 2004;38:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettee K, Ham S, Macera C, Ainsworth B. The reliability of a survey question on television viewing and associations with health risk factors in US adults. Obesity. 2008;17(3):487–493. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taber DR, Stevens J, Murray DM, et al. The Effect of a Physical Activity Intervention on Bias in Self-Reported Activity. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(5):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS-United States Clinical Growth Charts. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]