Abstract

The use of botanical dietary supplements is increasingly popular, due to their natural origin and the perceived assumption that they are safer than prescription drugs. While most botanical dietary supplements can be considered safe, a few contain compounds, which can be converted to reactive biological reactive intermediates (BRIs) causing toxicity. For example, sassafras oil contains safrole, which can be converted to a reactive carbocation forming genotoxic DNA adducts. Alternatively, some botanical dietary supplements contain stable BRIs such as simple Michael acceptors that react with chemosensor proteins such as Keap1 resulting in induction of protective detoxification enzymes. Examples include curcumin from turmeric, xanthohumol from hops, and Z-ligustilide from dang gui. Quinones (sassafras, kava, black cohosh), quinone methides (sassafras), and epoxides (pennyroyal oil) represent BRIs of intermediate reactivity, which could generate both genotoxic and/or chemopreventive effects. The biological targets of BRIs formed from botanical dietary supplements and their resulting toxic and/or chemopreventive effects are closely linked to the reactivity of BRIs as well as dose and time of exposure.

Keywords: Biological reactive intermediates, botanical dietary supplements, chemoprevention, electrophiles, epoxides, carbocations, nitrenium ions, quinones

Introduction

The use of botanical dietary supplements has increased exponentially in recent years. Approximately 60% of Americans use some form of supplements regularly and 1 in 6 report using botanical dietary supplements [1]. They are often perceived to be safer than prescription drugs due to their “natural” origin, long-standing ethnomedical use, and over-the-counter availability. However, unlike pharmaceuticals that must undergo extensive clinical trials prior to FDA approval, dietary supplements have little regulation of either efficacy or safety in the USA [2, 3]. Over-the-counter availability often leads to over dosing and to severe interactions when taken together with other medications. In addition, several of these botanicals are currently prepared using different procedures than traditional extraction methods often leading to higher concentrations of certain potentially toxic compound classes. In particular, a significant number of these herbal products have been associated with hepatotoxic effects, resulting from consumption of high doses of the supplements and/or when used in combination with other medications [4-6]. The ultimate toxin is often a biological reactive intermediate (BRI) either an electrophile or free radical formed by oxidative metabolism. Alternatively, some botanical dietary supplements contain weak BRIs, which could be responsible for their chemopreventive properties. Several examples of botanicals, which form BRIs will be discussed in this review.

Types of BRIs

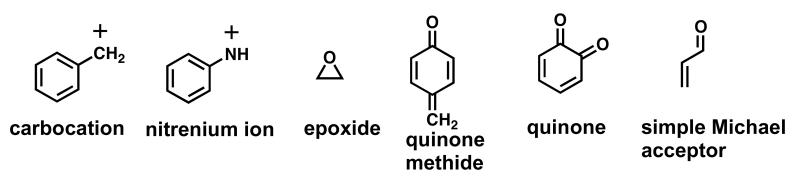

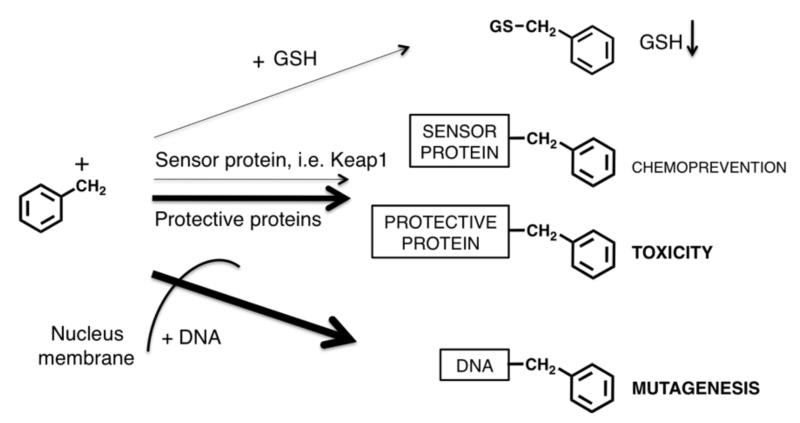

The most common types of BRIs are shown in Figure 1. The reactivity/selectivity principle can be used to make general predictions on the biological targets of BRIs and their resulting biological effects [7]. BRIs range in reactivity from highly reactive positively charged electrophiles such as carbocations and nitrenium ions, which have fleeting lifetimes to more stable neutral electrophiles such as epoxides, quinoids, and simple Michael acceptors. Highly reactive electrophiles are not selective and react indiscriminately with the most convenient biological nucleophiles, which are usually those present at the site of formation of the BRI (e.g., synthesizing enzyme) and/or those present in highest concentration (e.g., water). The carbocations and nitrenium ions fall into this category. On the other hand, more stable electrophiles are more selective and generally prefer reaction at sulfur nucleophilic groups on proteins and with GSH.

Figure 1. Types of BRIs.

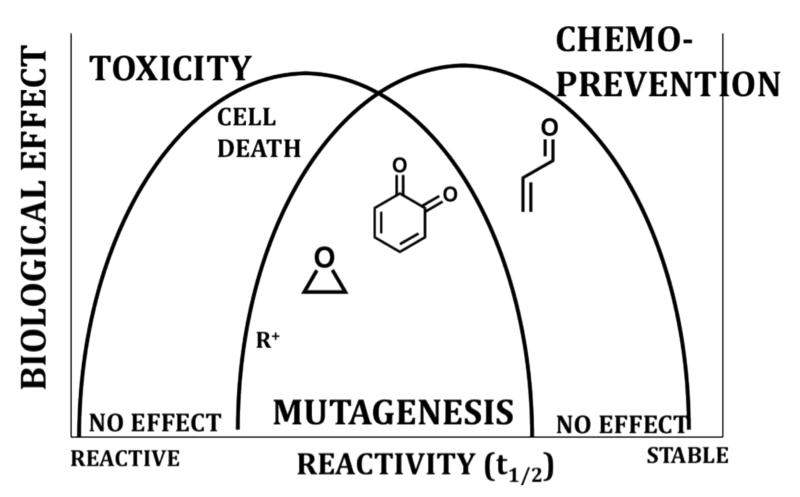

The reactivity/selectivity of BRIs has a major influence on their toxicity and/or chemopreventive properties (Table 1, Figure 2). While BRI’s can cause toxicities, BRI’s with modest reaction rates, at low concentrations are able to activate natural detoxification responses leading to chemoprevention/cytoprotection [8]. Since reactivity, dose, time and the resulting chemopreventive or toxic effects are closely related (Table 1, Figure 2), predictions about the biological effects of BRIs can be difficult. What follows are specific examples of BRIs formed from botanical dietary supplements, which may be responsible for their toxic and/or chemopreventive properties.

Table 1.

Summary of botanical BRIs, toxicity concerns, and resulting FDA actions.

| Botanical dietary supplement |

Main compound that forms BRIsa |

Type of BRIb |

Predicted Toxicity/ chemoprevention |

FDA | Availability in the USA |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sassafras

oil |

Safrole | R+, Q, QM |

Carcinogenic, hepototoxic |

Safrole prohibited |

Safrole free sassafras extracts are available |

[13, 101] |

| Aristolochia | Aristolochic acid |

N+ | Carcinogenic, nephrotoxic |

Prohibited | Not available |

[43] |

|

Pennyroyal

oil |

Pulegone | Epoxide | Hepatotoxic | Warning, restricted |

Available | [45, 102] |

|

Black

cohosh |

Caffeic acids |

Q | Hepatotoxic/ chemoprevention |

Some side effects reported |

Available | [64, 103] |

| Kava | Methysticin | Q, MA | Hepatotoxic/ chemoprevention |

Safety alert | Available | [104] |

| Hops | Xantho- humol |

MA | Chemoprevention | Essential oil recognized as safe by FDA |

Available | [81, 83, 105] |

| Dang gui | Ligustilide | MA | Chemoprevention | No reports | Available | [99] |

Examples of compounds that form BRIs.

R+: Carbocation, Q: Quinone, QM: Quinone methide, N+: Nitrenium ion, MA: Michael acceptor.

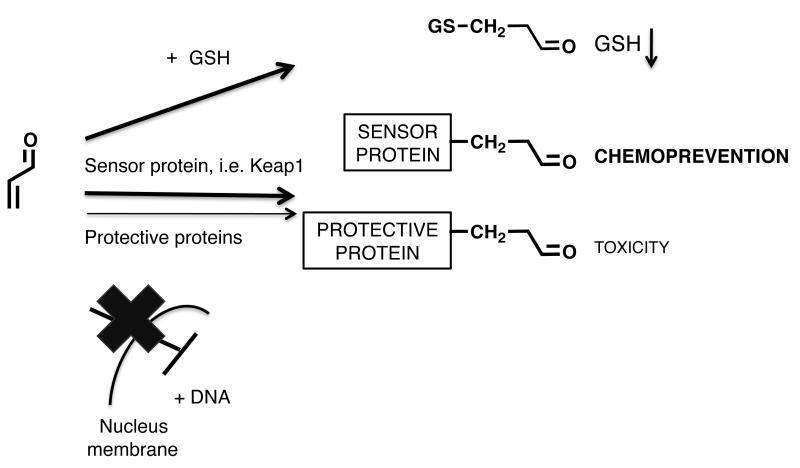

Figure 2. Reactivity/selectivity principle and BRIs.

The reactivity/selectivity of BRIs has a major influence on their toxicity and/or chemopreventive properties [7]. BRIs range in reactivity from highly reactive electrophiles such as carbocations (R+) and nitrenium ions, which have fleeting lifetimes to more stable neutral electrophiles such as epoxides, quinoids, and simple Michael acceptors. Reactive electrophiles are not selective and react indiscriminately with nucleophiles potentially causing toxicity. Moderately reactive electrophiles, such as epoxides or quinoids, may react with DNA leading to DNA adducts causing mutagenesis and carcinogenesis. Finally, weak electrophiles, such as simple Michael acceptors at low concentrations are able to activate natural detoxification responses leading to chemoprevention/cytoprotection [8].

Sassafras oil

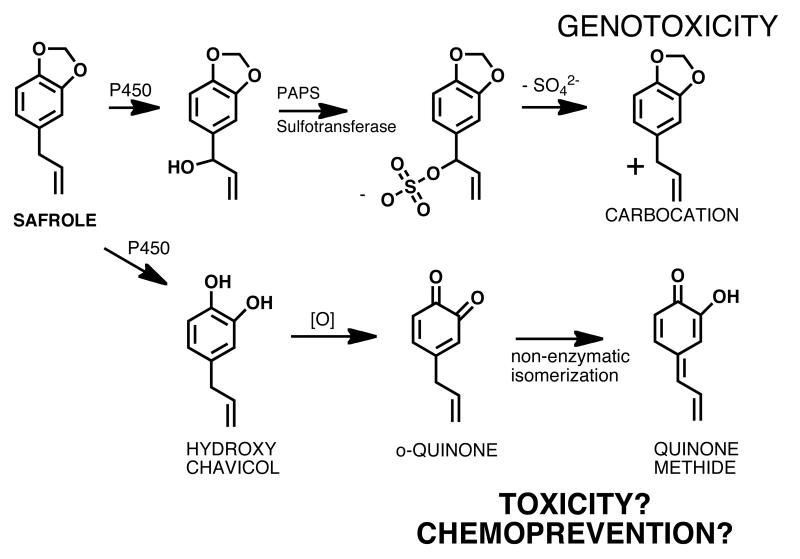

The main constituent of sassafras oil is safrole, which is also present in a number of herbs and spices, such as nutmeg, mace, cinnamon, anise, black pepper, and sweet basil [4]. Sassafras oil is extracted from the root bark of the tree Sassafras albidum [9, 10]. It has had a traditional and widespread use as a natural diuretic, as well as a remedy against urinary tract disorders until safrole was discovered to be hepatotoxic and weakly carcinogenic [4, 11]. In 1960 the FDA banned the use of sassafras oil as a food and flavoring additive because of the high content of safrole and its proven carcinogenic effects [12]. Oil of sassafras that is safrole free can still be used as flavoring agent in food [13]. Two bioactivation pathways of safrole to potentially hepatotoxic intermediates have been reported (Figure 3) [14-16]. The first one involves P450 catalyzed hydroxylation of the benzyl carbon producing 1′-hydroxysafrole and conjugation with sulfate generating a reactive sulfate ester. This ester undergoes a SN1 displacement reaction creating a highly reactive carbocation, which alkylates DNA (Figure 3) [14, 17]. The second pathway involves P450 catalyzed hydroxylation of the methylenedioxy ring and formation of the catechol, hydroxychavicol, which is a natural product found in betel leaf (Figure 3) [14, 18, 19]. Hydroxychavicol can easily be oxidized to the o-quinone which isomerizes nonenzymatically to the more electrophilic p-quinone methide [14]. Both pathways could explain the genotoxic effects of safrole and DNA adducts consistent with the carbocation pathway (Figure 3) have been identified in vitro and in vivo [20-25]. Recently, studies with betel quid chewers demonstrated that betel quid containing safrole induced DNA adducts are highly associated with the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) in Taiwan [26]. These experiments confirm the genotoxic effects of safrole and thus justify the restrictions made by the FDA and other health authorities. Interestingly, when topically applied betel leaf extract and hydroxychavicol were evaluated for their preventive activity on 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) induced skin tumors in two mice strains, the extract as well as hydroxychavicol reduced DMBA induced tumor formation [27]. These studies demonstrate that toxic and/or chemopreventive activities of quinones, such as the quinones formed from hydroxychavicol, might be closely related.

Figure 3. BRIs formed from safrole in sassafras oil.

Aristolochia fangchi

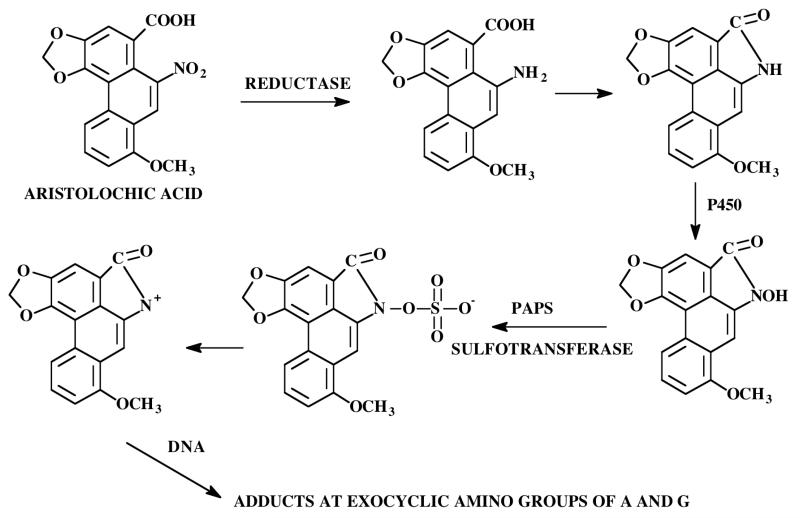

Aristolochic acid (Figure 4), a nitrophenanthrene carboxylic acid, is a natural product found in the plant Aristolochia fangchi. The roots of this plant were found in a number of products sold as “traditional herbal medicines”, as dietary supplements, or weight-loss remedies [28]. In Belgium in the early 1990s, the use of slimming products including Chinese herbs lead to an endemic nephropathy with permanent kidney damage, including end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation [29, 30]. The same symptoms occurred in patients, who were exposed to botanical preparations containing aristolochic acid, in other European and Asian countries as well as in the United States [31]. In addition, aristolochic acid can induce cancer primarily in the urinary tract as observed in some of the patients taking the slimming products [32, 33]. Further analysis of the dietary supplements revealed that at least in some of these products the roots of Stephania tetrandra were inadvertently substituted with the roots of Aristolochia fangchi, because of the close similarity of the Chinese names [34]. It has been reported that the first step of metabolic bioactivation of aristolochic acid involves reduction of the NO2 group catalyzed by P450 reductase (Figure 4) [31, 35-37]. The amino- and carboxyl groups cyclize producing an aristolactam, which is N-hydroxylated. The N-hydroxylactam intermediate could be further metabolized by Phase II enzymes, such as sulfotransferases, leading to the formation of reactive sulfate esters, which undergo SN1 displacement to produce the ultimate carcinogenic and electrophilic nitrenium ion [38]. These highly reactive BRIs forms stable covalent DNA adducts at the exocyclic amino groups of adenine and guanine [29, 39, 40]. These mutagenic lesions lead to AT – TA transversions in vitro, which were identified in high frequency in codon 61 of the c-Ha-ras oncogene in tumors of rodents [41]. Based on all these findings the International Agency of Research on Cancer classified Aristolochia species as human carcinogens [42] and the FDA issued warnings about the use of products that may contain aristolochic acid [43].

Figure 4. BRIs formed from aristolochic acid.

Pennyroyal oil

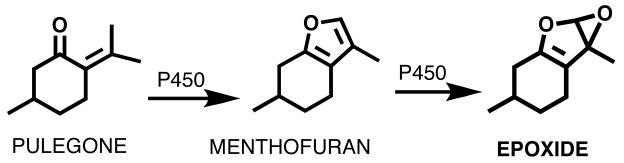

Pennyroyal oil derived from Mentha pulegium or Hedeoma pulegoides has been used as an abortifacient and as an insect repellent since Roman times [44]. Despite reports of hepatatoxicity, pennyroyal products have been purported to purify blood, alleviate menstrual symptoms, feverish colds, and to act as a digestive [45, 46]. While no apparent evidence exists for these claimed beneficial activities, there is strong data supporting the hepatotoxic effects of pennyroyal oil [47-50]. Small quantities can cause acute liver and lung damage and 10-15 mL of the oil have resulted in death [51]. As a result, most pennyroyal preparations, including the oil, contain warnings of possible toxicity. The oil primarily contains pulegone plus smaller amounts of several other monoterpenes (menthone, iso-menthone, and neomenthone) that are encountered in mint species [52]. In vivo metabolism of pulegone is extremely complex, generating dozens of metabolites in urine and bile of treated animals [47]. The major bioactivation step involves the oxidation of pulegone by cytochrome P450s to its proximate hepatotoxic metabolite menthofuran (Figure 5) [53-56]. Subsequently, menthofuran is oxidized to an epoxide which is likely the ultimate toxic BRI (Figure 5) [48]. It has been shown that the epoxide was capable of covalently bind to GSH and proteins causing hepatic injury [48, 52, 57, 58]. Evidence from animal experiments suggests that N-acetylcysteine provides at least partial protection from the hepatotoxic effects of pennyroyal oil [52].

Figure 5. BRIs formed from pulegone in pennyroyal oil.

Black Cohosh

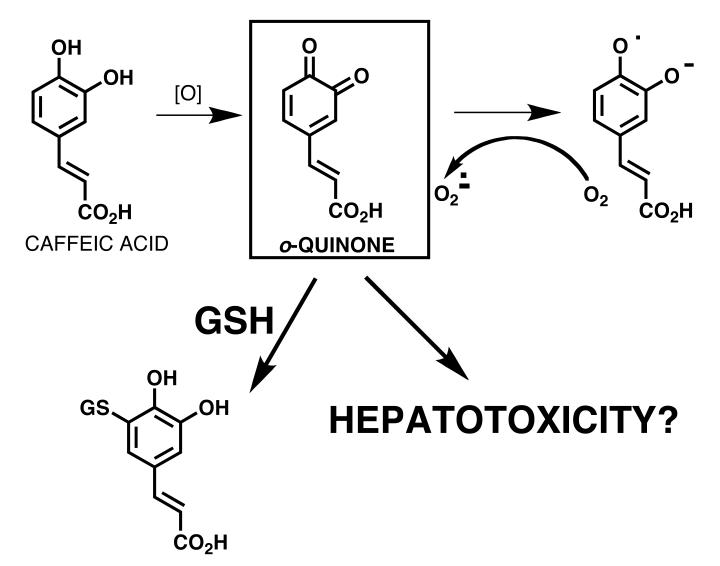

Black cohosh root extract have a long tradition in native American Indian culture [59]. Extracts have been used against snake bites, women complaints, malaria, fever, rheumatism, cough, inflammation. Black cohosh dietary supplements are currently the most frequently used dietary supplements for the alleviation of menopausal symptoms, in particular hot flashes [60, 61]. However, recently hepatotoxic reactions have been described [62]. Thirty case reports on use of black cohosh products concerning liver damage were reported and analyzed [63]. Only possible causality, but no probable or certain causality have been described for liver toxicities observed in patients taking black cohosh dietary supplements.

Black cohosh extracts have been screened for their potential to form electrophilic BRIs which could be trapped as their GSH conjugates and analyzed using an ultrafiltration mass spectrometric assay [64]. On the basis of their propensity to form GSH adducts following metabolic activation by hepatic microsomes and NADPH in vitro, a total of eight electrophilic metabolites of black cohosh were detected, including quinoid metabolites of fukinolic acid, fukiic acid, caffeic acid (Figure 6), and cimiracemate B. Mercapturates (N-acetylcysteine conjugates) corresponding to the GSH conjugates identified during screening were synthesized and characterized using LC-MS/MS with product-ion scanning. During a phase I clinical trial of black cohosh in perimenopausal women, urine was collected from seven subjects, each of whom took a single oral dose of either 32, 64, or 128 mg of the black cohosh extract. These urine samples were analyzed for the presence of mercapturate conjugates using positive-ion electrospray LC-MS and LC-MS/MS. However, mercapturate conjugates of these black cohosh constituents were not detected in urine samples from women even at the highest dose. Therefore, for moderate doses of a dietary supplement containing black cohosh, this study found no cause for safety concerns over the formation of quinoid metabolites from black cohosh in women.

Figure 6. BRIs formed from black cohosh.

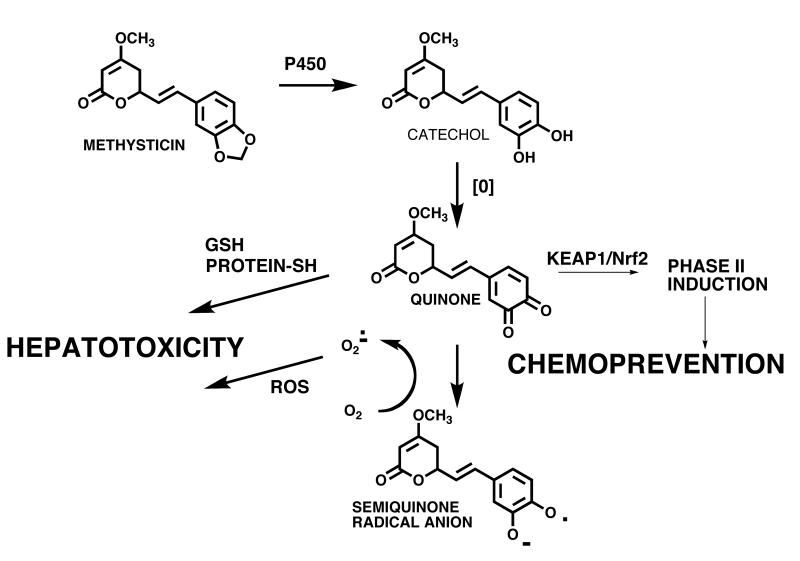

Kava

Kava (Piper methysticum) has been used by the South Pacific Islanders for centuries for spiritual services and as an intoxicating beverage [65]. Kava is marketed in North America as a sedative, muscle relaxant, anesthetic, and anticonvulsant [66, 67]. Kava lactones, such as kawain and methysticin (Figure 7), are considered to be the active constituents of kava extracts responsible for their sedative and anxiolytic effects [66]. However, largely due to reports of hepatotoxic effects, several European countries and Canada have banned or severely restricted the sale of kava containing products [51, 68]. In the USA, the FDA has issued warnings although no restrictions have been placed on the sale of Kava dietary supplements [68].

Figure 7. BRIs formed from Kava.

The mechanism of kava hepatotoxicity is not completely understood; however, it likely involves bioactivation of the methylenedioxy kava lactones to electrophilic o-quinones, which can react with glutathione (GSH) and/or covalently modify proteins [68]. Incubation of a methanol extract of kava roots with hepatic microsomes in the presence of GSH showed the formation of two GSH conjugates consistent with trapping of the o-quinones from methysticin and 7,8-dihydromethysticin (Figure 7) [68]. This and other reports show that kava extracts rich in kava lactones can cause GSH depletion and therefore put undue stress on the liver [69]. Interestingly, it has been reported that the traditional extraction method, which involves maceration of the roots in a water and coconut milk solution, extracts less kava lactones from the rhizomes than observed in commercial products, which are usually 96% ethanol or acetone extracts [65, 69]. This suggests that a reduction of kava lactones in kava products and an optimization of extract preparation could reduce the hepatotoxic potential of kava. Alternatively, kava quinones could be responsible for potential chemopreventive properties of Kava [70] through induction of detoxification enzymes and/or through anti-inflammatory pathways (see below).

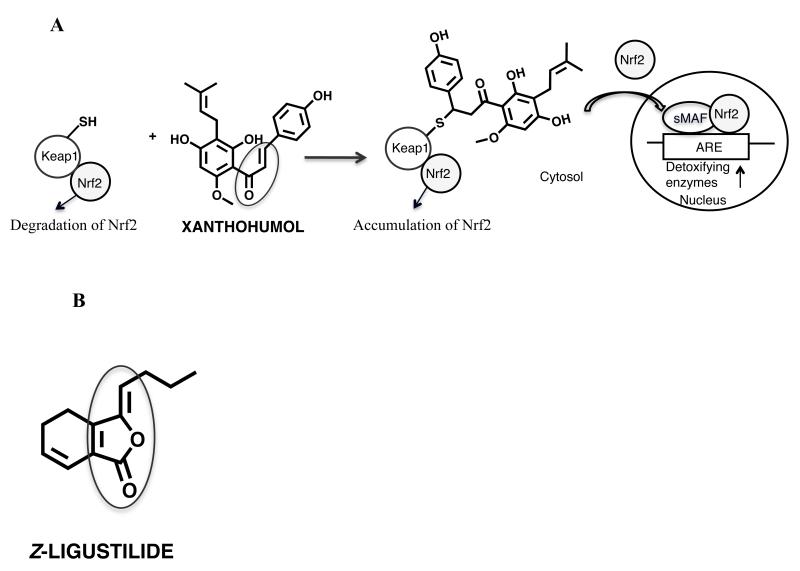

Hops

The strobiles of hops (Humulus lupulus L.), Cannabaceae, (hops) are popular as a flavoring agent in beer and have been traditionally used as remedies for mood and sleep disturbances in Europe [71]. Recently, hops extracts have been studied as botanical alternatives to hormone replacement therapy for the relief of menopausal symptoms mainly due to the potent phytoestrogen, 8-prenylnaringenin [72-78]. In addition, the cytoprotective properties of hops and its most abundant prenylated chalcone, xanthohumol, have also been analyzed (Figure 8A) [79-82]. XH is a pleiotropic agent with multiple biological activities, for example induction of NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [83]. The expression of NQO1 and other detoxifying enzymes are known to be upregulated through the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway in response to weak BRIs and/or oxidative stress. In unstressed cells, Keap1 forms a complex with Nrf2 and facilitates the degradation of Nrf2 in the cytoplasm (Figure 8A). It has been shown that the Michael acceptor xanthohumol in hops alkylates human Keap1 protein and increases ARE reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner [83, 84]. The three most readily modified cysteines of human Keap1 by xanthohumol were identified as C151, C319, and C613 [85]. Taken together, the modification of cysteines by Michael addition reaction acceptors such as xanthohumol in Keap1 seem to play a critical role in the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling system leading to upregulation of ARE regulated detoxification enzymes (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. A: BRI formed from Hops and schematic of ARE upregulation of detoxifying enzymes by Michael addition acceptors, such as xanthohumol.

In unstressed cells, Keap1 forms a complex with Nrf2 and facilitates the degradation of Nrf2 in the cytoplasm [106]. Michael acceptors, such as xanthohumol, can alkylate Keap1 causing Nrf2 nuclear accumulation [83, 84]. In the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to the ARE with association of small MAF proteins and increases transcription of ARE regulated detoxifying enzymes [107].

B: BRI formed from Dang gui

Dang gui

The dried roots of dang gui (Angelica sinensis) (Oliv.) diels, Apiaceae have been used for centuries as “women’s tonic” especially for alleviating menstrual disorders or menopausal symptoms in Asia [86-92]. Cytoprotective properties of dang gui have been described including antioxidative, cancer preventive, and overall reduction in oxidative stress [88, 93]. For example, it has been reported that lipophilic extracts, as well as n-butylidenephthalide isolated from the chloroform extract exert antiproliferative effects on tumor cells in vitro and in vivo [94-97]. In addition, recent data revealed that Z-ligustilide, the major lipophilic constituent in A. sinensis, reduces oxidative stress in brain tissue possibly through increasing antioxidative enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase, and reducing apoptotic markers [91, 98].

Recent mechanism of action studies revealed that A. sinensis extracts contain the simple Michael acceptor Z-ligustilide that can induce the detoxification enzyme NQO1 [99] (Figure 8B). Incubation of Z-ligustilide with GSH and subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis revealed that Z-ligustilide covalently modified GSH. In addition, using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and LC-MS/MS, it was demonstrated that the lipophilic extracts and ligustilide alkylated important cysteine residues in human Keap1 protein, such as C151, thus activating Nrf2 and transcription of ARE regulated genes. Z-ligustilide’s activity can be explained by the α,β,γ,δ -unsaturated lactone moiety with the cross-conjugated alkene system (Figure 8B) reacting in a Michael fashion with nucleophiles, such as sulfhydryl groups in Keap1 protein.

Conclusions

Although most botanical dietary supplements have health benefits and can be considered safe, a few contain compounds, which can be converted to BRIs causing toxicity in some circumstances or chemoprevention in others. Examples shown here illustrate the formation of BRIs of differing reactivity including carbocations (safrole), nitrenium ions (aristolochic acid), epoxides (pennyroyal oil), quinoids (safrole, black cohosh, kava), and simple Michael acceptors (hops, dang gui) (Table 1). The botanical dietary supplements, which have been associated with mutagenic/carcinogenic effects, all contain compounds, which are metabolized to BRIs that can alkylate DNA (safrole, aristolochic acid) (Figure 9). On the other hand, the weak electrophiles represented by the simple Michael acceptors in hops (xanthohumol), dang gui (Z-ligustilide), turmeric (curcumin) [100] are likely responsible for the chemopreventive effects of these botanicals through induction of detoxification enzymes such as NQO1 through the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway (Figure 10). Quinoids (quinones, quinone methides) such as those formed from compounds in sassafras (Figure 3), black cohosh (Figure 6), and/or kava (Figure 7), could represent BRIs with both mutagenic effects through DNA alkylation and/or chemopreventive properties through modification of chemosensor proteins. The overall risk/benefit of botanical dietary supplements could be due to BRI formation and interaction with resulting biological targets, which likely depends on the reactivity/selectivity of the BRI, as well as the dose and time of exposure. Adverse effects and/or chemopreventive effects attributed to consumption of dietary supplements could be the result of oxidative metabolism of some constituents to BRIs. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of botanical dietary supplements especially for standardization of active or potentially toxic compounds and good manufacturing processes with recommendations for dosing regimens, are warranted.

Figure 9. Targets of mutagenic BRIs.

Figure 10. Targets of chemopreventive BRIs.

Acknowledgments

This report was funded by NIH grant CA135237 from NCI provided to B. Dietz and P50 AT00155 jointly provided to the UIC/NIH Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research by the Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Institute for General Medical Sciences, the Office for Research on Women’s Health, and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCI, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the Office of Dietary Supplements, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Gershwin ME, Borchers AT, Keen CL, Hendler S, Hagie F, Greenwood MR. Public safety and dietary supplementation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1190(1):104–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bent S, Ko R. Commonly used herbal medicines in the United States: a review. Am. J. Med. 2004;116(7):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.10.036. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sadovsky R, Collins N, Tighe AP, Brunton SA, Safeer R. Patient use of dietary supplements: a clinician’s perspective. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2008;24(4):1209–1216. doi: 10.1185/030079908x280743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rietjens IM, Martena MJ, Boersma MG, Spiegelenberg W, Alink GM. Molecular mechanisms of toxicity of important food-borne phytotoxins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005;49(2):131–158. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Furbee RB, Barlotta KS, Allen MK, Holstege CP. Hepatotoxicity associated with herbal products. Clin. Lab Med. 2006;26(1):227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kennedy DA, Seely D. Clinically based evidence of drug-herb interactions: a systematic review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2010;9(1):79–124. doi: 10.1517/14740330903405593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mayr H, Ofial AR. The reactivity-selectivity principle: an imperishable myth in organic chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006;45(12):1844–1854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dinkova-Kostova AT, Massiah MA, Bozak RE, Hicks RJ, Talalay P. From the Cover: Potency of Michael reaction acceptors as inducers of enzymes that protect against carcinogenesis depends on their reactivity with sulfhydryl groups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98(6):3404–3409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Johnson BM, Bolton JL, van Breemen RB. Screening botanical extracts for quinoid metabolites. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14(11):1546–1551. doi: 10.1021/tx010106n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kamdem DP, Gage DA. Chemical composition of essential oil from the root bark of Sassafras albidum. Planta Med. 1995;61(6):574–575. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fennell TR, Miller JA, Miller EC. Characterization of the biliary and urinary glutathione and N-acetylcysteine metabolites of the hepatic carcinogen 1′-hydroxysafrole and its 1′-oxo metabolite in rats and mice. Cancer Res. 1984;44(8):3231–3240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heikes DL. SFE with GC and MS determination of safrole and related allylbenzenes in sassafras teas. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 1994;32(7):253–258. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/32.7.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Food and Drug Administration . In: Everything Added to Food in the United States (EAFUS): Oil of sassafras, safrole free -§ 172.580 Safrole-free extract of sassafras. U.D.o.h.h.a.h. services, editor. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bolton JL, Acay NM, Vukomanovic V. Evidence that 4-allyl-o-quinones spontaneously rearrange to their more electrophilic quinone methides: potential bioactivation mechanism for the hepatocarcinogen safrole. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994;7(3):443, 450. doi: 10.1021/tx00039a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Miller EC, Swanson AB, Phillips DH, Fletcher TL, Liem A, Miller JA. Structure-activity studies of the carcinogenicities in the mouse and rat of some naturally occurring and synthetic alkenylbenzene derivatives related to safrole and estragole. Cancer Res. 1983;43(3):1124–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rietjens IM, Boersma MG, van der Woude H, Jeurissen SM, Schutte ME, Alink GM. Flavonoids and alkenylbenzenes: mechanisms of mutagenic action and carcinogenic risk. Mutat. Res. 2005;574(1-2):124–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Miller EC, Miller JA, Boberg EW, Delclos KB, Lai CC, Fennell TR, Wiseman RW, Liem A. Sulfuric acid esters as ultimate electrophilic and carcinogenic metabolites of some alkenylbenzenes and aromatic amines in mouse liver. Carcinog. Compr. Surv. 1985;10:93–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jeng JH, Wang YJ, Chang WH, Wu HL, Li CH, Uang BJ, Kang JJ, Lee JJ, Hahn LJ, Lin BR, Chang MC. Reactive oxygen species are crucial for hydroxychavicol toxicity toward KB epithelial cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61(1):83–96. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3272-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nakagawa Y, Suzuki T, Nakajima K, Ishii H, Ogata A. Biotransformation and cytotoxic effects of hydroxychavicol, an intermediate of safrole metabolism, in isolated rat hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009;180(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Luo G, Guenthner TM. Covalent binding to DNA in vitro of 2′,3′-oxides derived from allylbenzene analogs.[erratum appears in Drug Metab Dispos 1997 Jan;25(1):131] Drug Metab. Dispos. 1996;24(9):1020–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gupta KP, van Golen KL, Putman KL, Randerath K. Formation and persistence of safrole-DNA adducts over a 10,000-fold dose range in mouse liver. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14(8):1517–1521. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.8.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Randerath K, Putman KL, Randerath E. Flavor constituents in cola drinks induce hepatic DNA adducts in adult and fetal mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;192(1):61–68. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Daimon H, Sawada S, Asakura S, Sagami F. In vivo genotoxicity and DNA adduct levels in the liver of rats treated with safrole. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(1):141–146. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Daimon H, Sawada S, Asakura S, Sagami F. Analysis of cytogenetic effects and DNA adduct formation induced by safrole in Chinese hamster lung cells. Teratog., Carcinog. Mutagen. 1997;17(1):7–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6866(1997)17:1<7::aid-tcm3>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Johnson WW. Many drugs and phytochemicals can be activated to biological reactive intermediates. Curr. Drug Metab. 2008;9(4):344–351. doi: 10.2174/138920008784220673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chung YT, Hsieh LL, Chen IH, Liao CT, Liou SH, Chi CW, Ueng YF, Liu TY. Sulfotransferase 1A1 haplotypes associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma susceptibility in male Taiwanese. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(2):286–294. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Azuine MA, Amonkar AJ, Bhide SV. Chemopreventive efficacy of betel leaf extract and its constituents on 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced carcinogenesis and their effect on drug detoxification system in mouse skin. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 1991;29(4):346–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chan TY. Potential risks associated with the use of herbal anti-obesity products. Drug Saf. 2009;32(6):453–456. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Arlt VM, Stiborova M, Schmeiser HH. Aristolochic acid as a probable human cancer hazard in herbal remedies: a review. Mutagenesis. 2002;17(4):265–277. doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.4.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kessler DA. Cancer and herbs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342(23):1742–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422309. [see comment][comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stiborova M, Frei E, Hodek P, Wiessler M, Schmeiser HH. Human hepatic and renal microsomes, cytochromes P450 1A1/2, NADPH:cytochrome P450 reductase and prostaglandin H synthase mediate the formation of aristolochic acid-DNA adducts found in patients with urothelial cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;113(2):189–197. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kessler DA. Cancer and herbs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342(23):1742–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Greensfelder L. Alternative medicine. Herbal product linked to cancer. Science. 2000;288(5473):1946. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5473.1946a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].FDA . Letter to Health Professionals Regarding Safety Concerns Related to the Use of Botanical Products Containing Aristolochic Acid. Apr 4th, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Stiborova M, Hajek M, Frei E, Schmeiser HH. Carcinogenic and nephrotoxic alkaloids aristolochic acids upon activation by NADPH: cytochrome P450 reductase form adducts found in DNA of patients with Chinese herbs nephropathy. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2001;20(4):375–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Stiborova M, Frei E, Wiessler M, Schmeiser HH. Human enzymes involved in the metabolic activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acids: evidence for reductive activation by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1A2. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14(8):1128–1137. doi: 10.1021/tx010059z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stiborova M, Frei E, Sopko B, Wiessler M, Schmeiser HH. Carcinogenic aristolochic acids upon activation by DT-diaphorase form adducts found in DNA of patients with Chinese herbs nephropathy. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(4):617–625. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.4.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Arlt VM, Glatt H, Muckel E, Pabel U, Sorg BL, Seidel A, Frank H, Schmeiser HH, Phillips DH. Activation of 3-nitrobenzanthrone and its metabolites by human acetyltransferases, sulfotransferases and cytochrome P450 expressed in Chinese hamster V79 cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;105(5):583–592. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pfau W, Schmeiser HH, Wiessler M. Aristolochic acid binds covalently to the exocyclic amino group of purine nucleotides in DNA. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11(2):313–319. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stiborova M, Frei E, Breuer A, Wiessler M, Schmeiser HH. Evidence for reductive activation of carcinogenic aristolochic acids by prostaglandin H synthase -- (32)P-postlabeling analysis of DNA adduct formation. Mutat. Res. 2001;493(1-2):149–160. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(01)00171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schmeiser HH, Janssen JW, Lyons J, Scherf HR, Pfau W, Buchmann A, Bartram CR, Wiessler M. Aristolochic acid activates ras genes in rat tumors at deoxyadenosine residues. Cancer Res. 1990;50(17):5464–5469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].IARC . Some traditional herbal medicines, some mycotoxins, naphthalene and styrene. Vol. 2002. IARC; Lyon: 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Food and Drug Administration Dietary Supplements: Aristolochic Acid - FDA Concerned About Botanical Products, Including Dietary Supplements. Containing Aristolochic Acid. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gunby P. Plant known for centuries still causes problems today. JAMA. 1979;241(21):2246–2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Anderson IB, Mullen WH, Meeker JE, Khojasteh Bakht SC, Oishi S, Nelson SD, Blanc PD. Pennyroyal toxicity: measurement of toxic metabolite levels in two cases and review of the literature. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124(8):726–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-8-199604150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Furbee RB, Barlotta KS, Allen MK, Holstege CP. Hepatotoxicity associated with herbal products. Clin. Lab. Med. 2006;26(1):227–241. x. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen LJ, Lebetkin EH, Burka LT. Metabolism of (R)-(+)-menthofuran in Fischer-344 rats: identification of sulfonic acid metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003;31(10):1208–1213. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.10.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen LJ, Lebetkin EH, Burka LT. Metabolism of (R)-(+)-pulegone in F344 rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001;29(12):1567–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bakerink JA, Gospe SM, Jr., Dimand RJ, Eldridge MW. Multiple organ failure after ingestion of pennyroyal oil from herbal tea in two infants. Pediatrics. 1996;98(5):944–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Anderson IB, Mullen WH, Meeker JE, Khojasteh Bakht SC, Oishi S, Nelson SD, Blanc PD. Pennyroyal toxicity: measurement of toxic metabolite levels in two cases and review of the literature. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124(8):726–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-8-199604150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Furbee RB, Barlotta KS, Allen MK, Holstege CP. Hepatotoxicity associated with herbal products. Clin. Lab. Med. 2006;26(1):227–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Anderson IB, Mullen WH, Meeker JE, Khojasteh Bakht SC, Oishi S, Nelson SD, Blanc PD. Pennyroyal toxicity: measurement of toxic metabolite levels in two cases and review of the literature. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996;124(8):726–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-8-199604150-00004. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Khojasteh-Bakht SC, Nelson SD, Atkins WM. Glutathione S-transferase catalyzes the isomerization of (R)-2-hydroxymenthofuran to mintlactones. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;370(1):59–65. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Thomassen D, Slattery JT, Nelson SD. Menthofuran-dependent and independent aspects of pulegone hepatotoxicity: roles of glutathione. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;253(2):567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Gordon WP, Huitric AC, Seth CL, McClanahan RH, Nelson SD. The metabolism of the abortifacient terpene, (R)-(+)-pulegone, to a proximate toxin, menthofuran. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1987;15(5):589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sztajnkrycer MD, Otten EJ, Bond GR, Lindsell CJ, Goetz RJ. Mitigation of pennyroyal oil hepatotoxicity in the mouse. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2003;10(10):1024–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Madyastha KM, Moorthy B. Pulegone mediated hepatotoxicity: evidence for covalent binding of R(+)-[14C]pulegone to microsomal proteins in vitro. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1989;72(3):325–333. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(89)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].McClanahan RH, Thomassen D, Slattery JT, Nelson SD. Metabolic activation of (R)-(+)-pulegone to a reactive enonal that covalently binds to mouse liver proteins. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1989;2(5):349–355. doi: 10.1021/tx00011a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) In: Coates PM, editor. Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. Dekker, M.; New York: 2005. pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Palacio C, Masri G, Mooradian AD. Black cohosh for the management of menopausal symptoms: a systematic review of clinical trials. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(1):23–36. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200926010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Farnsworth NR, Mahady GB. Research highlights from the UIC/NIH Center for Botanical Dietary Supplements Research for Women’s Health: Black cohosh from the field to the clinic. Pharm. Biol. 2009;47(8):755–760. doi: 10.1080/13880200902988637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Teschke R. Black cohosh and suspected hepatotoxicity: inconsistencies, confounding variables, and prospective use of a diagnostic causality algorithm. A critical review. Menopause. 2010;17(2):426–440. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181c5159c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Mahady GB, Low Dog T, Barrett ML, Chavez ML, Gardiner P, Ko R, Marles RJ, Pellicore LS, Giancaspro GI, Sarma DN. United States Pharmacopeia review of the black cohosh case reports of hepatotoxicity. Menopause. 2008;15(4 Pt 1):628–638. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31816054bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Johnson BM, van Breemen RB. In vitro formation of quinoid metabolites of the dietary supplement Cimicifuga racemosa (black cohosh) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16(7):838–846. doi: 10.1021/tx020108n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Cote CS, Kor C, Cohen J, Auclair K. Composition and biological activity of traditional and commercial kava extracts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;322(1):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Singh YN, Singh NN. Therapeutic potential of kava in the treatment of anxiety disorders. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(11):731–743. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216110-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Blumenthal M, Busse W, Goldberg A, Gruenwald J, Hall T, Riggins C, Rister R, Kava Kava. In: The Complete German Commission E Monographs. Blumenthal M, editor. American Botanical Council; Austin, Texas: 1998. pp. 156–157. [Google Scholar]

- [68].Johnson BM, Qiu SX, Zhang S, Zhang F, Burdette JE, Yu L, Bolton JL, van Breemen RB. Identification of novel electrophilic metabolites of piper methysticum Forst (Kava) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2003;16(6):733–740. doi: 10.1021/tx020113r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Whitton PA, Lau A, Salisbury A, Whitehouse J, Evans CS. Kava lactones and the kava-kava controversy. Phytochemistry. 2003;64(3):673–679. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Johnson TE, Kassie F, O’Sullivan MG, Negia M, Hanson TE, Upadhyaya P, Ruvolo PP, Hecht SS, Xing C. Chemopreventive effect of kava on 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone plus benzo[a]pyrene-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila Pa) 2008;1(6):430–438. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zanoli P, Zavatti M. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological profile of Humulus lupulus L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;116(3):383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Overk CR, Yao P, Chadwick LR, Nikolic D, Sun Y, Cuendet MA, Deng Y, Hedayat AS, Pauli GF, Farnsworth NR, van Breemen RB, Bolton JL. Comparison of the in vitro estrogenic activities of compounds from hops (Humulus lupulus) and red clover (Trifolium pratense) J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(16):6246–6253. doi: 10.1021/jf050448p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bowe J, Li XF, Kinsey-Jones J, Heyerick A, Brain S, Milligan S, O’Byrne K. The hop phytoestrogen, 8-prenylnaringenin, reverses the ovariectomy-induced rise in skin temperature in an animal model of menopausal hot flushes. J. Endocrinol. 2006;191(2):399–405. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Bolca S, Possemiers S, Maervoet V, Huybrechts I, Heyerick A, Vervarcke S, Depypere H, De Keukeleire D, Bracke M, De Henauw S, Verstraete W, Van de Wiele T. Microbial and dietary factors associated with the 8-prenylnaringenin producer phenotype: a dietary intervention trial with fifty healthy post-menopausal Caucasian women. Br. J. Nutr. 2007;98(5):950–959. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507749243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Effenberger KE, Johnsen SA, Monroe DG, Spelsberg TC, Westendorf JJ. Regulation of osteoblastic phenotype and gene expression by hop-derived phytoestrogens. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;96(5):387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Dimpfel W, Suter A. Sleep improving effects of a single dose administration of a valerian/hops fluid extract - a double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled sleep-EEG study in a parallel design using electrohypnograms. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2008;13(5):200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Heyerick A, Vervarcke S, Depypere H, Bracke M, De Keukeleire D. A first prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the use of a standardized hop extract to alleviate menopausal discomforts. Maturitas. 2006;54(2):164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Erkkola R, Vervarcke S, Vansteelandt S, Rompotti P, De Keukeleire D, Heyerick A, randomized A. double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot study on the use of a standardized hop extract to alleviate menopausal discomforts. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(6):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Chadwick LR, Nikolic D, Burdette JE, Overk CR, Bolton JL, van Breemen RB, Froehlich R, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Pauli GF. Estrogens and congeners from spent hops (Humulus lupulus L.) J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:2024–2032. doi: 10.1021/np049783i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Plazar J, Filipic M, Groothuis GM. Antigenotoxic effect of Xanthohumol in rat liver slices. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2008;22(2):318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Plazar J, Zegura B, Lah TT, Filipic M. Protective effects of xanthohumol against the genotoxicity of benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (IQ) and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BOOH) in HepG2 human hepatoma cells. Mutat. Res. 2007;632(1-2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Lamy V, Roussi S, Chaabi M, Gosse F, Schall N, Lobstein A, Raul F. Chemopreventive effects of lupulone, a hop {beta}-acid, on human colon cancer-derived metastatic SW620 cells and in a rat model of colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28(7):1575–1581. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Dietz BM, Kang YH, Liu G, Eggler AL, Yao P, Chadwick LR, Pauli GF, Farnsworth NR, Mesecar AD, van Breemen RB, Bolton JL. Xanthohumol isolated from Humulus lupulus Inhibits menadione-induced DNA damage through induction of quinone reductase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18(8):1296–1305. doi: 10.1021/tx050058x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Liu G, Eggler AL, Dietz BM, Mesecar AD, Bolton JL, Pezzuto JM, van Breeman RB. A screening method for the discovery of potential cancer chemoprevention agents based on mass spectrometric detection of alkylated Keap1. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6407–6414. doi: 10.1021/ac050892r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Luo Y, Eggler AL, Liu D, Liu G, Mesecar AD, van Breemen RB. Sites of Alkylation of Human Keap1 by Natural Chemoprevention Agents. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Deng S, Chen SN, Yao P, Nikolic D, van Breemen RB, Bolton JL, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Pauli GF. Serotonergic activity-guided phytochemical investigation of the roots of Angelica sinensis. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69(4):536–541. doi: 10.1021/np050301s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Chemical Industry. People’s Republic of China; Beijing: 2000. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China-Radix Angelica sinensis. [Google Scholar]

- [88].Upton R, Gui Dang. Angelica sinensis. In: Coates P.M.e.a., editor. Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2005. pp. 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- [89].Hou YZ, Zhao GR, Yang J, Yuan YJ, Zhu GG, Hiltunen R. Protective effect of Ligusticum chuanxiong and Angelica sinensis on endothelial cell damage induced by hydrogen peroxide. Life Sci. 2004;75(14):1775–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hou YZ, Zhao GR, Yuan YJ, Zhu GG, Hiltunen R. Inhibition of rat vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by extract of Ligusticum chuanxiong and Angelica sinensis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100(1-2):140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Kuang X, Yao Y, Du JR, Liu YX, Wang CY, Qian ZM. Neuroprotective role of Z-ligustilide against forebrain ischemic injury in ICR mice. Brain Res. 2006;1102(1):145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Piersen CE. Phytoestrogens in botanical dietary supplements: implications for cancer. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2003;2(2):120–138. doi: 10.1177/1534735403002002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Haranaka K, Satomi N, Sakurai A, Haranaka R, Okada N, Kosoto H, Kobayashi M. Antitumor activities and tumor necrosis factor producibility of traditional Chinese medicines and crude drugs. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1985;5(4):271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Tsai NM, Lin SZ, Lee CC, Chen SP, Su HC, Chang WL, Harn HJ. The antitumor effects of Angelica sinensis on malignant brain tumors in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(9):3475–3484. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Tsai NM, Chen YL, Lee CC, Lin PC, Cheng YL, Chang WL, Lin SZ, Harn HJ. The natural compound n-butylidenephthalide derived from Angelica sinensis inhibits malignant brain tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2006;99(4):1251–1262. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Lee WH, Jin JS, Tsai WC, Chen YT, Chang WL, Yao CW, Sheu LF, Chen A. Biological inhibitory effects of the Chinese herb danggui on brain astrocytoma. Pathobiology. 2006;73(3):141–148. doi: 10.1159/000095560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Cheng YL, Chang WL, Lee SC, Liu YG, Chen CJ, Lin SZ, Tsai NM, Yu DS, Yen CY, Harn HJ. Acetone extract of Angelica sinensis inhibits proliferation of human cancer cells via inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Life Sci. 2004;75(13):1579–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Yu Y, Du JR, Wang CY, Qian ZM. Protection against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury by Z-ligustilide in PC12 cells. Exp. Brain Res. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Dietz BM, Liu D, Hagos GK, Yao P, Schinkovitz A, Pro SM, Deng S, Farnsworth NR, Pauli GF, van Breemen RB, Bolton JL. Angelica sinensis and its alkylphthalides induce the detoxification enzyme NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 by alkylating Keap1. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21(10):1939–1948. doi: 10.1021/tx8001274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Direct and indirect antioxidant properties of inducers of cytoprotective proteins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 1):S128–138. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Food and Drug Administration . Safrole. 1989. PART 189—SUBSTANCES PROHIBITED FROM USE IN HUMAN FOOD, § 189.180. [Google Scholar]

- [102].Food and Drug Administration . Everything Added to Food in the United States (EAFUS): penny royal: In conjunction w/flavors - 172.510. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [103].Food and Drug Administration FDA Poisonous Plant Database - Toxicity of medicinal herbal preparations. 2008 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/Plantox/Detail.CFM?ID=24000.

- [104].Food and Drug Administration MedWatch The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program - Kava (Piper methysticum) 2002 http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm154577.htm.

- [105].Food and Drug Administration . § 182.20 Essential oils, oleoresins (solvent free) and natural extractives (including distillates) Food and Drug Administration, HHS; 2002. Subpart A - general provisions, 21 CFR Ch. I (4-1-02 Edition) § 182.20. [Google Scholar]

- [106].Eggler AL, Gay KA, Mesecar AD. Molecular mechanisms of natural products in chemoprevention: induction of cytoprotective enzymes by Nrf2. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 1):S84–94. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Kwon KH, Barve A, Yu S, Huang MT, Kong AN. Cancer chemoprevention by phytochemicals: potential molecular targets, biomarkers and animal models. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007;28(9):1409–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]