INTRODUCTION

Microbial identification, together with studies investigating the microorganism’s physiology, genetics, metabolism and ecological functions, comprise the intellectual pillars of microbiology (12). Currently, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes (20) is the gold-standard approach for identifying unknown microorganisms in clinical and environmental samples. Though PCR lends itself to the relatively fast culture-independent identification of microorganisms, the extensive and complex sample preparation required, as well as expensive reagents, has motivated the search for PCR-independent methods (7). One such method is matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), which, although not culture-independent, provides a rapid and relatively low-cost (5) method for identifying bacteria, yeast, and fungi, often to the species and, on occasion, sub-species level, with little or no sample preparation (1, 17). These characteristics enable its clinical use for screening and identifying known pathogenic microorganisms for disease control and treatment (17). Given its increasing use in clinical diagnostics (3, 4) and potential for application in the food industry (13), the technique’s conspicuous absence in the undergraduate curriculum presents a curriculum gap that can be filled via exercises utilizing this commercialized technique.

Pedagogical research has highlighted the beneficial effects of incorporating activities—for example, simple demonstrations, experiments, and field trips—into classes to: (i) create interest, and thus, motivate students to learn the subject matter, and (ii) help students make important connections between textbook learning and real-world phenomena (2, 9–12, 22). This article describes a laboratory exercise (suitable for complementing a variety of life sciences, analytical chemistry, and bioinformatics courses) that involve students in collecting water samples from a drain or small stream on campus, cultivating, and subsequently identifying the microorganisms in the water using a combined MALDI-TOF MS and bioinformatics approach. By blending modern mass spectrometry instrumentation and bioinformatics concepts for phylogenetic analysis with cell culture techniques, this exercise provides students with the opportunity to learn leading-edge concepts and gain hands-on experience of instrumentation that they will likely encounter in their future bioscience careers or in graduate and medical school. More important, in contrast to laboratory experiments designed to verify known observations or theories, the campus “field trip” to collect real water samples can help to open the students’ minds to the unknown as well as kindle their curiosity and spirit of inquiry—skill sets critical for leading an intellectually fulfilling life in a knowledge-based economy. Finally, with slight modifications to sample collection and inoculation procedures, this activity is broadly applicable to performing a census of microbes in diverse contexts such as on the surfaces of vegetables or a person’s skin.

PROCEDURE

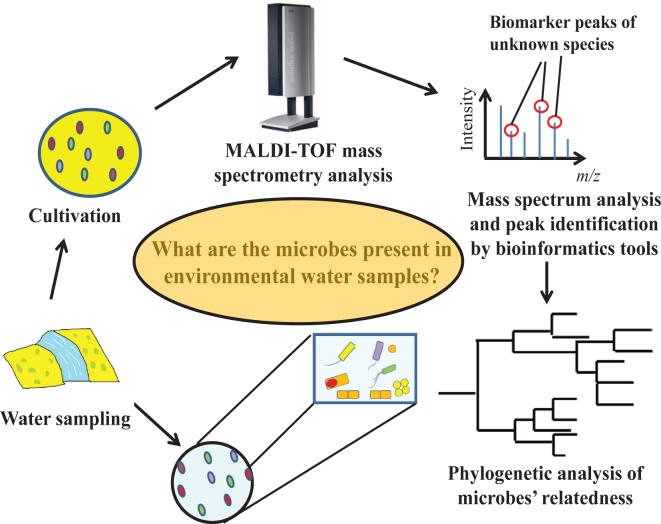

The laboratory exercise comprises four main segments: (i) sample collection, (ii) cultivation, (iii) MALDI-TOF MS, and (iv) bioinformatics analysis (Fig. 1). Firstly, 100 ml pre-sterilized polypropylene bottles (Nalgene, USA) were used to collect environmental water samples that, in turn, served as inoculum for pre-prepared R2A agar plates (Difco, USA; composition in g/L: yeast extract, 0.5; proteose peptone No. 3, 0.5; casamino acids, 0.5; D-glucose, 0.5; soluble starch, 0.5; sodium pyruvate, 0.3; dipotassium phosphate, 0.3; magnesium sulfate, 0.05; agar, 15.0)—the gold-standard for cultivating microorganisms from oligotrophic environments (14). The water’s pH, temperature, and conductivity (a measure of salinity) should also be measured with a portable pH/conductivity meter if possible. Using the spread plate technique under aseptic conditions, 0.1 or 1 ml of the water sample is spread onto R2A agar (3 technical replicates) with a sterile plastic disposable spreader. As the water sample may contain vegetative cells and spores from a variety of microorganisms, the inoculation step should be performed in a Class II biological safety cabinet. The inoculated plates are subsequently incubated in an inverted position at a temperature mimicking that of the sample collection site. Depending on the incubation temperature, nutrient conditions of the water sample, and the microbial species present, a couple of days are generally needed for cultivation (especially for slow-growing microorganisms), but students should check the agar plates daily to observe the microorganisms’ relative growth rates—information important to hypothesizing metabolic and functional relationships between them.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the various components—and key learning objectives—of the laboratory exercise. Combining cell culture, mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics analysis of biomarker peaks from cultivated microorganisms, students engage in an inquiry-based exercise using the scientific method to tackle a research question with unknown answers.

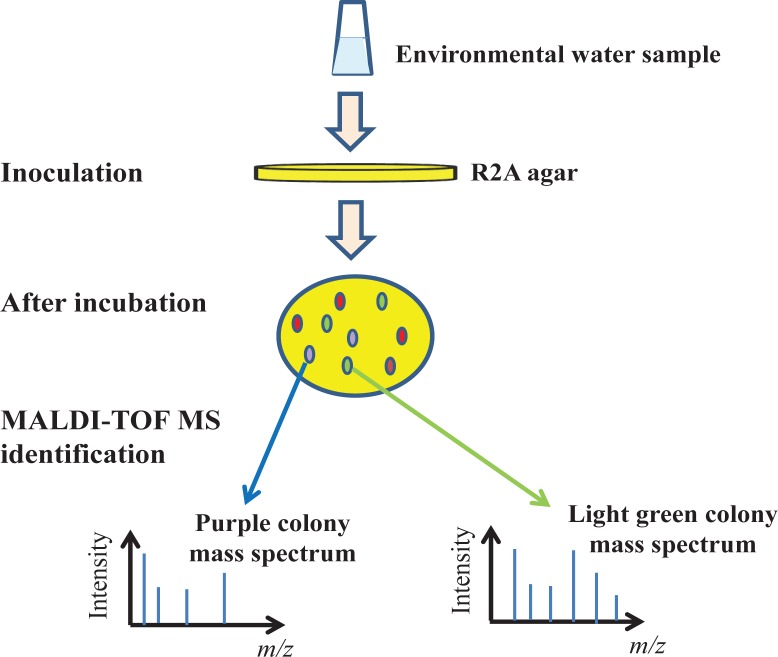

After a few days of incubation, colonies of at least 0.4 cm in diameter can be identified by MALDI-TOF MS (Fig. 2) (see Appendix 1), which has a detection limit of ∼103 cells/ml (6). Briefly, a 10 μl plastic inoculation loop is used to directly smear a colony from the agar onto a 384-well stainless steel target plate. A small volume (1–2 μl) of MALDI matrix (either α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) or 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) dissolved in an acetonitrile (50%) and trifluoroacetic acid (2.5%) buffer) is subsequently overlaid onto the sample, and the mixture allowed to air-dry for 15 minutes at room temperature before analysis by a MALDI-TOF MS operated under linear positive ion mode with a nitrogen UV laser (337 nm). Both CHCA and DHB matrixes offer good ionization of biomolecules in the mass range from 2,000 to 20,000 Daltons (Da). Prior to analysis, the instrument should be calibrated with an external standard, for example, cyto-chrome c (∼12,000 Da). For mass spectrum acquisition, 50 laser pulses are directed at each spot of the sample mixture; however, due to the presence of “sweet spots” in the mixture that typically produce better mass spectra, interrogation of a number of spots is needed to identify an ideal sample location for generating high quality mass spectra (16). Although the analysis process can be automated, research reveals that manual spectra acquisition would, in general, generate better spectra (15) and allow students to experience all aspects of instrument operation—from sample preparation to optimization of analysis conditions, and finally, spectra acquisition.

FIGURE 2.

Concept underlying MALDI-TOF MS-based identification of microorganisms, in particular, differences in m/z ratios and relative intensities of the mass peaks afford the ability to distinguish between species. Note the need for a culture step prior to mass spectrometry analysis, a key difference from the culture-independent approach of PCR amplification followed by 16S rRNA sequencing.

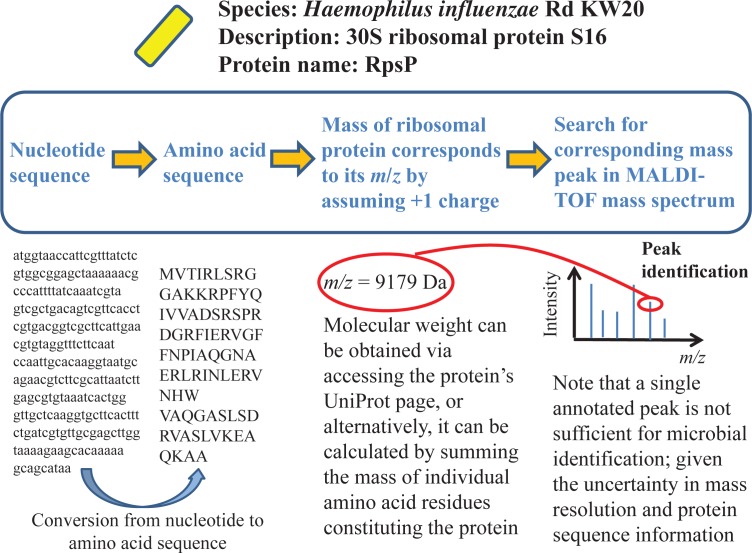

After collection of mass spectrum data, students identify the microorganisms using the proteome database search approach (8, 21). Briefly, the ribosomal protein sequences—translated from those of the corresponding genes—of various microbes whose sequenced genomes are deposited in the Microbial Genome Database for Comparative Analysis (MBGD) (http://mbgd.genome.ad.jp/) (19) are queried, and their masses—and thus, m/z ratios—obtained from the protein’s UniProt page or calculated based on that of the constituent amino acids (assuming no fragmentation and an overall molecular charge of +1). Next, the m/z ratios are used to search for their corresponding mass peaks in the extracted peak lists of various mass spectra for identification purposes (Fig. 3). Additionally, construction of a phylogenetic tree encompassing all identified microorganisms could be undertaken via the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software tool (http://www.megasoftware.net/) (18) to provide a visual map of the sample’s microbial diversity and the microorganisms’ relatedness. Furthermore, hypotheses postulating the microorganisms’ ecological functions and interactions can be formulated based on their growth characteristics (for example, closely associated colonies on agar) and their habitat’s environmental conditions.

FIGURE 3.

Steps important to the identification of mass peaks—using the proteome database search approach—from MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of individual colony. Briefly, MBGD stores both the nucleotide and amino acid sequence of each ribosomal gene—where accessing the gene’s UniProt page yields the ribosomal protein’s molecular weight (and also m/z ratio; assuming +1 molecular ion charge), which, in turn, can be used to search the extracted peaks list of each mass spectrum.

CONCLUSION

A curriculum is a living entity: specifically, it evolves and responds to changes in technology, pedagogy, and societal needs. Centrality of microbial identification in microbiology, emergence of MALDI-TOF MS as a rapid tool for identifying microorganisms, as well as the advent of bioinformatics algorithms capable of querying huge datasets, call for pedagogical innovations to impart, in each student, the ability to isolate and cultivate microorganisms from samples and competently use modern mass spectrometry instruments and bioinformatics tools to ask, search, and answer questions concerning species’ identities. This communication describes an inquiry-based laboratory exercise that integrates the learning of theoretical and operational aspects of MALDI-TOF MS and bioinformatics tools through practical hands-on experimentation addressing a research question with unknown answers: what are the microorganisms present in an environmental water sample? From water sample collection, inoculation and cultivation, daily observations of growth behavior, MALDI-TOF MS analysis, and finally, interpretation of mass spectra and identification of microorganisms aided by bioinformatics tools, students can learn experimental and computational techniques in addition to practicing the scientific method in answering a research question. The most important learning outcome, however, is imbuing, in the students, a sense of wonder in the natural world and igniting their inquiring minds.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Appendix 1: Theoretical overview and practical tips for exercise implementation

Acknowledgments

The ASM advocates that students must successfully demonstrate the ability to explain and practice safe laboratory techniques. For more information, read the laboratory safety section of the ASM Curriculum Recommendations: Introductory Course in Microbiology and the Guidelines for Biosafety in Teaching Laboratories, available at www.asm.org. The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anhalt JP, Fenselau C. Identification of bacteria using mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1975;47:219–225. doi: 10.1021/ac60352a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bascom-Slack CA, Arnold AE, Strobel SA. Student-directed discovery of the plant microbiome and its products. Science. 2012;338:485–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1215227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessède E, et al. Matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization biotyper: experience in the routine of a university hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:533–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bizzini A, Durussel C, Bille J, Greub G, Prod’hom G. Performance of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of bacterial strains routinely isolated in a clinical microbiology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1549–1554. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01794-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherkaoui A, et al. Comparison of two matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry methods with conventional phenotypic identification for routine identification of bacteria to the species level. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1169–1175. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01881-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croxatto A, Prod’hom G, Greub G. Applications of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in clinical diagnostic microbiology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:380–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeAngelis KM, et al. PCR amplification-independent methods for detection of microbial communities by the high-density microarray PhyloChip. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:6313–6322. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05262-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demirev PA, Ho Y-P, Ryzhov V, Fenselau C. Microorganism identification by mass spectrometry and protein database searches. Anal Chem. 1999;71:2732–2738. doi: 10.1021/ac990165u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forest K, Rayne S. Thinking outside the classroom: integrating field trips into a first-year undergraduate chemistry curriculum. J Chem Educ. 2009;86:1290–1294. doi: 10.1021/ed086p1290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gammon K. Room to grow—and learn. HHMI Bulletin. 2011;24:38–39. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korfiatis KJ, Tunnicliffe SD. The living world in the curriculum: ecology, an essential part of biology learning. J Biol Educ. 2012;46:125–127. doi: 10.1080/00219266.2012.715425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merkel S. The development of curricular guidelines for introductory microbiology that focus on understanding. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2012;13:32–38. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v13i1.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolaou N, Xu Y, Goodacre R. Detection and quantification of bacterial spoilage in milk and pork meat using MALDI-TOF-MS and multivariate analysis. Anal Chem. 2012;84:5951–5958. doi: 10.1021/ac300582d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reasoner DJ, Geldreich EE. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:1–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.1.1-7.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumaker S, Borror CM, Sandrin TR. Automating data acquisition affects mass spectrum quality and reproducibility during bacterial profiling using an intact cell sample preparation method with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2012;26:243–253. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Šedo O, Voráč A, Zdráhal Z. Optimization of mass spectral features in MALDI-TOF MS profiling of Acinetobacterspecies. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;34:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seng P, et al. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:543–551. doi: 10.1086/600885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchiyama I. MBGD: microbial genome database for comparative analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:58–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woese CR, Fox GE. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:5088–5090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wynne C, Fenselau C, Demirev PA, Edwards N. Top-down identification of protein biomarkers in bacteria with unsequenced genomes. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9633–9642. doi: 10.1021/ac9016677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X. Teaching molecular phylogenetics through investigating a real-world phylogenetic problem. J Biol Educ. 2011;46:103–109. doi: 10.1080/00219266.2011.634018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Theoretical overview and practical tips for exercise implementation