Abstract

One in four adults reports a clinically significant fear of dental injections, leading many to avoid dental care. While systematic desensitization is the most common therapeutic method for treating specific phobias such as fear of dental injections, lack of access to trained therapists, as well as dentists’ lack of training and time in providing such a therapy, means that most fearful individuals are not able to receive the therapy needed to be able to receive necessary dental treatment. Computer Assisted Relaxation Learning (CARL) is a self-paced computerized treatment based on systematic desensitization for dental injection fear. This multicenter, block-randomized, dentist-blind, parallel-group study conducted in 8 sites in the United States compared CARL with an informational pamphlet in reducing fear of dental injections. Participants completing CARL reported significantly greater reduction in self-reported general and injection-specific dental anxiety measures compared with control individuals (p < .001). Twice as many CARL participants (35.3%) as controls (17.6%) opted to receive a dental injection after the intervention, although this was not statistically significant. CARL, therefore, led to significant changes in self-reported fear in study participants, but no significant differences in the proportion of participants having a dental injection (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00609648).

Keywords: dental anxiety, phobic disorders, dental anesthesia, computer-assisted therapy, psychological desensitization, pamphlets

Introduction

One in four adults reports a clinically significant fear of dental injections, and one in 20 reports avoiding dental treatment because of a fear of dental injections (Milgrom et al., 1997). Individuals with dental injection fear report greater pain during injections compared with non-fearful individuals (van Wijk and Hoogstraten, 2009). Therefore, fear of dental injections is a significant barrier to dental care for a sizable proportion of the population.

Craske (1999) describes applying systematic desensitization in the treatment of injection phobia. Individuals learn and use coping strategies when presented with “a graduated hierarchy of situations involving…injection(s)”, such as “finger-prick blood tests…vaccinations or blood donations…and multiple dental appointments” (p. 253). Individuals fearful of dental injections and completing a systematic desensitization protocol show an increased likelihood of receiving a dental injection (Agdal et al., 2010), with as many as 89% receiving dental injections a year after treatment (Vika et al., 2009). A key component of systematic desensitization is exposure to the feared object or situation in a gradual manner, so as not to overwhelm the individual with too much anxiety to continue (Beck and Emery, 1985; p. 265). As early as the 1970s, clinical researchers began experimenting with automated exposure protocols, reducing the need for face-to-face therapeutic interventions with a trained therapist (e.g., Lang et al., 1970).

Computer Assisted Relaxation Learning (CARL) is a self-paced, computerized program based on systematic desensitization aimed at reducing fear of dental injections, and has been described in detail elsewhere (Coldwell et al., 1998, 2007). Through brief (2- to 4-minute) video segments, CARL introduces cognitive and physical coping strategies, then an exposure hierarchy wherein a model is shown successfully managing anxiety while presented with increasingly invasive aspects of a dental injection (Coldwell et al., 1998). CARL has been received positively by fearful dental patients (Boyle et al., 2010).

This was a multicenter, block-randomized, dentist-blind, parallel-group study conducted in 8 sites in the United States. Prior work has shown that CARL effectively reduced dental injection fear after program completion and at 1-year follow up (Coldwell et al., 2007), but CARL has not been previously compared with usual care. This trial tested the efficacy of CARL compared with an informational pamphlet for reducing dental injection fear. Individuals fearful of dental injections were expected to show greater reductions in dental injection fear and greater acceptance of an optional dental injection when randomized to CARL than to a pamphlet control.

Materials & Methods

Participants and Recruitment

Individuals reporting fear and avoidance of dental injections were recruited through newspaper advertisements in the communities of 8 participating dental practices from February 2008 through June 2010. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol. Appendix A includes additional information about participants and their recruitment.

Measures

Modified Interval Scale of Anxiety Response

The Modified Interval Scale of Anxiety Response (Modified ISAR; Heaton et al., 2007a) is a modification of Corah and colleagues’ (1986) Interval Scale of Anxiety Response (ISAR). This single-item, 100-mm vertical labeled magnitude scale assesses respondents’ state anxiety from “calm, relaxed” to “absolutely terrified”.

Modified Dental Anxiety Scale

The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS; Humphris et al., 1995) is a 5-item scale assessing anticipatory dental anxiety, fear of dental cleanings, drilling, and injections. Respondents are asked to rate their anxiety across scenarios on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all anxious” to “extremely anxious”, and possible scores range from 5 to 25, with greater scores indicating higher levels of dental anxiety. The MDAS has been shown to have high internal consistency, good test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity and concurrent validity in samples of individuals with various levels of dental anxiety (Newton and Edwards, 2005; Humphris et al., 2009).

Dental Fear Survey

The Dental Fear Survey (DFS; Kleinknecht et al., 1973) is a 20-item measure used to identify emotional and physiological reactions associated with several aspects of dentistry, as well as avoidance of dental care due to anxiety. Possible scores range from 20 to 100, with greater scores indicating higher levels of dental anxiety. The DFS has been shown to have good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity (Newton and Buck, 2000), and correlates highly with dental providers’ ratings of patients’ anxiety during dental treatment (p < .05; Heaton et al., 2007b).

Needle Survey

The Needle Survey (NS; Milgrom et al., 1997) has 18 items for the specific assessment of fear of dental injections. Possible scores range from 18 to 90, with greater scores indicating higher levels of dental-injection–related anxiety. The NS has good internal consistency (alpha = 0.90; Milgrom et al., 1997) and distinguishes well between dentally fearful and non-fearful individuals (t = 7.5, p < .001; Milgrom et al., 1997).

Appendix C includes additional information about the measures used.

Procedure

Screening and Randomization

Upon arriving at the assigned dental office, participants received study information from a member of the dental practice staff trained in administration of the study. Once providing informed consent, participants completed the MDAS, DFS, and NS on a study computer in a separate, quiet area set apart in each office. Appendix B contains additional information regarding the screening procedures.

Participants were randomized separately within each dental practice. The computer for each practice contained a unique look-up table containing subject ID numbers for 32 participants, blocked into four groups of eight individuals, with four ‘CARL condition’ and four control participants in each block. Participants were given a $10 gift card to a large grocery store chain for completing the initial screening session.

CARL Intervention

When participants randomized to the CARL condition returned to the dental office, the dental staff member assigned to the study re-entered each participant’s unique study code number into the computer and initiated the program. Participants sat in the same area where they completed the screening and viewed screens and an introductory video explaining what to expect from the program and how to navigate through the program, including how to view scenes again as needed. The CARL program has been described in detail elsewhere (Coldwell et al., 1998), and Appendix C includes additional details about CARL procedures.

Pamphlet Control Condition

Participants in the pamphlet condition returned to the dental office and were given a tri-fold pamphlet containing information about patient comfort, topical and local anesthetic, and post-operative pain management. The pamphlet was based on information from a major dental Web site company and was meant to reflect what dentists typically tell patients about dental injections. Participants sat in the same area where they completed the screening and were given time to review the pamphlet in detail and the opportunity to ask a dental staff member questions about dental injections.

Upon completion of either protocol, participants again completed the computerized MDAS, DFS, and NS, were given a second $10 gift card and were offered the opportunity to receive an optional dental injection, described below.

Optional Injection

Participants were offered the opportunity to return to the dental office on another day to receive an actual dental injection, without receiving an incentive or dental treatment. Dentists were blind to participants’ condition assignment when completing the injection, and participants were told that they could stop the procedure at any time by raising their left hands. Details about the injection procedure are included in Appendix D.

Analysis Plan

Based on prior work with the CARL program (Coldwell et al., 2007, 2011), it was estimated that a sample size of 96 (48 per group) would allow for the detection of an 11-mm difference between groups in self-reported fear reduction on the primary outcome measure (Modified ISAR) with 80% power. Analyses included descriptive analyses, independent-sample t tests, and chi-square analyses; significance levels were set at 0.05 for all analyses. Regression analyses also compared post-intervention scores on the secondary outcome measures adjusted for gender, age, race, education, baseline fear scores, and dental office. Additional details are included in Appendix F.

Results

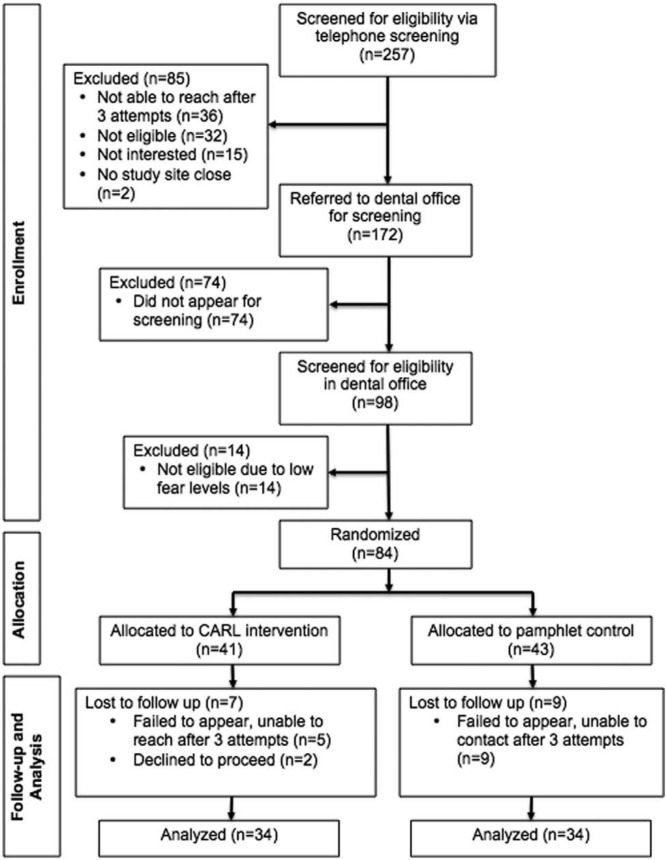

Eighty-four individuals (65.5% female) were screened and randomized at one of eight participating dental offices. Two of the 257 individuals screened by telephone (0.7%) were recruited from participating dental practices, while the remaining individuals were recruited through newspaper and online advertising. See Fig. 1 for the CONSORT flow diagram of enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for screening and recruitment.

In total, 68 participants completed the study (34 CARL, 34 pamphlet). Sixteen individuals (19%) failed to complete their assigned condition. The Table shows baseline characteristics of the participants who did and did not complete their assigned condition. Individuals who withdrew from the study were, for the most part, similar in terms of demographics and baseline fear scores to those who completed the study; however, those who withdrew had slightly higher DFS scores on average.

For participants whose complete (pre- and post-intervention) data are available (n = 68), the CARL and pamphlet groups had similar distributions of demographics and baseline fear scores (Table). Participants spent an average of 1.4 sessions (s.d. = 0.56, range = 1-3) with CARL; all control participants spent one session reviewing the pamphlet. There were no significant differences in pre- or post-intervention scores for participants who completed the CARL intervention in private vs. in university-based dental practices (Coldwell et al., 2011).

Table.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Who Completed and Withdrew from Study, by Condition

| Completed |

Withdrew |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARL | Pamphlet | CARL | Pamphlet | |

| n = 34 | n = 34 | n = 7 | n = 9 | |

| Gender, Number (%) | ||||

| Female | 21 (61.8) | 24 (70.6) | 4 (57.1) | 6 (66.7) |

| Male | 13 (38.2) | 10 (29.4) | 3 (42.9) | 3 (33.3) |

| Mean age (SD) [range], yrs | 39.9 (12.6)

[21-59] |

44.1 (14.3)

[18-68] |

37.6 (11.3)

[23-53] |

44.2 (8.4)

[28-56] |

| Race, Number (%) | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 25 (73.5) | 27 (79.4) | 5 (71.4) | 5 (55.6) |

| Black/African American | 4 (11.8) | 4 (11.8) | 0 | 3 (33.3) |

| Native American | 2 (5.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Asian | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 1 (14.3) | 1 (11.1) |

| Other | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnicity, Number (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 1 (2.9) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 33 (97.1) | 32 (94.1) | 6 (85.7) | 8 (88.9) |

| No response | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) |

| Education | ||||

| High School | 5 (14.7) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (33.3) |

| College | 23 (67.7) | 22 (64.7) | 5 (71.4) | 5 (55.6) |

| Graduate School | 6 (17.6) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (11.1) |

| MDAS mean (SD) [range] | 19.6 (4.0)

[9-25] |

20.5 (3.0)

[14-25] |

20.9 (3.5)

[14-25] |

20.7 (3.4)

[15-25] |

| DFS mean (SD) [range] | 72.7 (17.8)

[29-99] |

76.9 (12.8)

[46-96] |

82.3 (15.4)

[52-98] |

80.8 (14.5)

[50-99] |

| NS mean (SD) [range] | 56.2 (14.0)

[32-87] |

54.6 (12.3)

[34-90] |

55.4 (14.0)

[40-80] |

59.7 (9.5)

[46-71] |

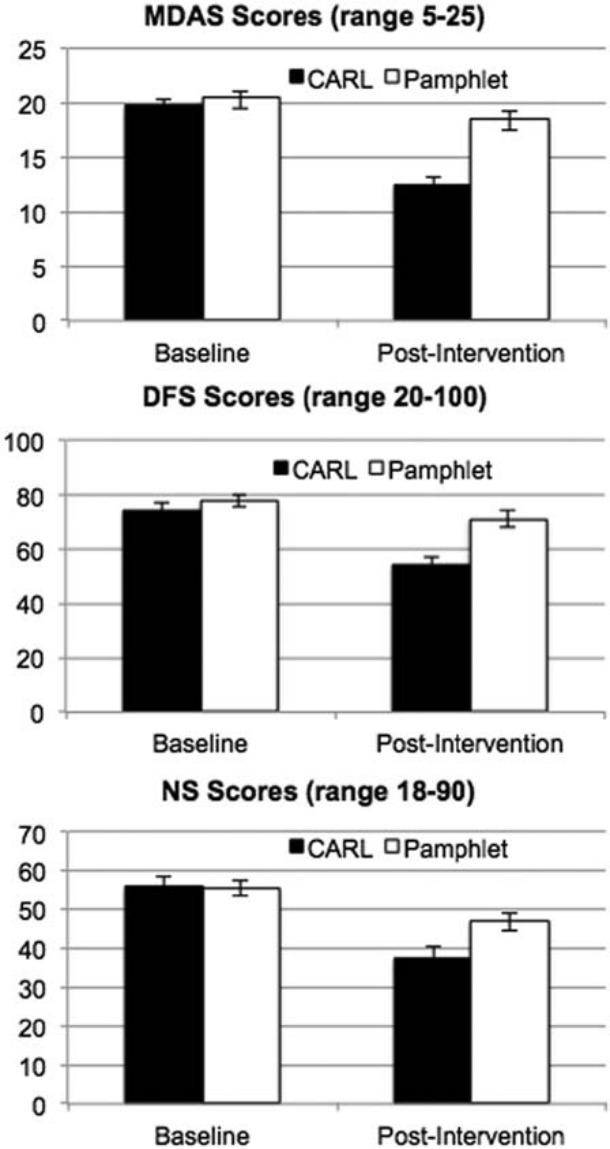

Fig. 2 shows pre- and post-intervention MDAS scores for both conditions. Mean fear scores were reduced in both conditions post-intervention, but the magnitude of the decrease was substantially greater in the CARL condition. Differences in mean post-intervention MDAS scores between CARL and control conditions were highly statistically significant (12.5 vs. 18.5, effect size 1.42, p < .001). Regression analysis gave an adjusted mean difference between groups of 5.5 (95% confidence interval 3.6, 7.4; p < .001). Similar results were found for DFS and NS scores. For DFS, mean post-intervention scores were 54.5 and 71.1 in CARL and control conditions, respectively (effect size 0.97, p < .001), and the regression-adjusted difference was 14.3 (95% confidence interval 8.5, 20.1; p < .001). For NS, mean post-intervention scores were 37.7 vs. 46.9 (effect size 0.63, p < .001) and the regression-adjusted difference was 11.7 (95% confidence interval 5.7, 17.7; p < .001). Additional results on the amount of time spent by participants are included in Appendix G.

Figure 2.

Changes in Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS; Humphris et al., 1995), Dental Fear Survey (DFS; Kleinknecht et al., 1973), and Needle Survey (NS; Milgrom et al., 1997) scores by condition. T-bars represent standard error of the mean.

Twice as many CARL participants returned for an optional injection compared with the control group. Twelve of 34 (35.3%) CARL participants received injections, while six of 34 (17.6%) pamphlet participants received injections. Because of the small overall proportion of participants receiving injections, this test had low power and did not reach statistical significance (χ2 = 2.7, p = .10). There was also no difference in Modified ISAR scores between groups for the 18 completing the injection (42.3 vs. 37.0, t = 0.36, p = .66).

Discussion

This study of the CARL program represents the first randomized control trial of a computerized treatment for dental injection fear. Participants completing the CARL program showed significantly greater fear reduction across the self-reported outcome measures compared with participants reviewing an informational pamphlet about dental injections. CARL, therefore, was successful for reducing dental fear in study participants. Nevertheless, few individuals returned for an optional dental injection. The low number of individuals choosing to return for an optional dental injection meant that there was low power to assess the primary outcome of self-reported anxiety during injection. More individuals in the CARL condition than in the pamphlet condition completed the injection (12 vs. 6), indicating that the program may have had an influence on willingness to complete an injection; however, there was insufficient power to assess this.

Computer-based cognitive-behavioral treatments have become more accepted as part of the arsenal of therapeutic options. For example, the FearFighterTM Panic and Phobia Treatment modality (FearFighter.com) is an online program endorsed by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom as clinically effective. The use of computer-based therapy reduces the reliance on in-person clinician time. In many countries, demand for trained clinicians exceeds the supply, and computer-based therapy has the promise to allow “therapists to help many more patients than before and to focus on issues which a computer cannot handle” (Marks et al., 2007; p. 9).

Participant recruitment was difficult. Only 57% of those referred to a dental office appeared for a screening. It was impossible to contact individuals who did not appear to determine their reasons for not following through with the referral. It is likely, however, that the fear leading them to the study also caused them to avoid the screening. Similarly, individuals randomized at the screening who did not complete the study had higher baseline fear scores than participants completing the study. Kaakko and colleagues (2001) reported on difficulties recruiting fearful individuals into dental fear studies. Individuals completing the study in both conditions had average MDAS scores of over 19 (Table), which has been used in prior studies as a cut-off indicating high dental anxiety (Humphris and King, 2011). These high dental fear scores indicate that participants were, in fact, highly dentally fearful at baseline, regardless of whether they did or did not complete the study.

Only 26% of participants completing the study returned for the optional dental injection. In a study such as this, a significant outcome of interest is whether participants seek dental treatment at different rates after working with either the CARL program or reviewing the pamphlet. A prior study of CARL (Coldwell et al., 2007) showed that 69% of individuals who completed the CARL program had successfully sought dental treatment within the one-year follow-up period, suggesting that CARL has the potential to reduce avoidance of dental care due to fear. Future CARL clinical trials should include a follow-up assessment of dental-treatment-seeking behaviors. Additional comments about the participants’ willingness to participate in the study are included in Appendix H.

In conclusion, CARL, a computerized therapeutic protocol, was successful in reducing self-reported dental fear related to dental injections compared with an informational standard of care. Since CARL does not require involvement by trained therapists or special training for dentists, it may increase access to this therapeutic approach to a wider proportion of the population, improving access to dental care and better oral health overall.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the following individuals, who were instrumental in the implementation of this study: Dr. Peter Milgrom, Chris Prall, Greg Mueller, Mary K. Hagstrom, and the staff of Northwest PRECEDENT. They also thank the study participants and the dentists and staffs of the participating dental offices: Dr. Bruce Burton, Dr. Gary Templeman; Dental Fears Research Clinic; Lower Columbia Oral Health; Mint Dental Studio; Northwest Dental Fears Research; Valley View Health Center; and the West Linn Smile Team.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grants U54DE014254, DE016750, DE016752, and 5K23DE019202; by the Washington Dental Service Endowed Professorship; and the Institute of Translational Health Sciences, which is funded through the Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR025014 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Agdal ML, Raadal M, Skaret E, Kvale G. (2010). Oral health and its influence on cognitive behavioral therapy in patients fulfilling the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV criteria for intra-oral injection phobia. Acta Odontol Scand 68:98-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Emory G. (1985). Anxiety disorders and phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle CA, Newton T, Milgrom P. (2010). Development of a UK version of CARL: a computer program for conducting exposure therapy for the treatment of dental injection fear. SAAD Dig 26:8-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell SE, Getz T, Milgrom P, Prall CW, Spadafora A, Ramsay DS. (1998). CARL: a LabVIEW 3 computer program for conducting exposure therapy for the treatment of dental injection fear. Behav Res Ther 36:429-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell SE, Wilhelm FH, Milgrom P, Prall CW, Getz T, Spadafora A, et al. (2007). Combining alprazolam with systematic desensitization therapy for dental injection phobia. J Anxiety Disord 21:871-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell SE, Heaton LJ, Ruff PA. (2011). Computerized dental fear treatment in university versus private practice settings [abstract]. J Dent Res 90(Spec Iss A):Abstract #2380. URL accessed on 12/19/2012 at: http://iadr.confex.com/iadr/2011sandiego/preliminaryprogram/abstract_147633.htm [Google Scholar]

- Corah NL, Zielezny MA, O‘Shea RM, Tines TJ, Mendola P. (1986). Development of an interval scale of anxiety response. Anesth Prog 33:220-224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG. (1999) Anxiety disorders: psychological approaches to theory and treatment. New York, NY: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton LJ, Garcia LJ, Gledhill LW, Beesley KA, Coldwell SE. (2007a). Development and validation of the Spanish Interval Scale of Anxiety Response (ISAR). Anesth Prog 54:100-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton LJ, Carlson CR, Smith TA, Baer RA, de Leeuw R. (2007b). Predicting anxiety during dental treatment using patients’ self-reports: less is more. J Am Dent Assoc 138:188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphris G, King K. (2011).The prevalence of dental anxiety across previous distressing experiences. J Anxiety Disord 25: 232-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. (1995). The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health 12:143-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphris GM, Dyer TA, Robinson PG. (2009). The modified dental anxiety scale: UK general public population norms in 2008 with further psychometrics and effects of age. BMC Oral Health 9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaakko T, Murtomaa H, Milgrom P, Getz T, Ramsay DS, Coldwell SE. (2001). Recruiting phobic research subjects: effectiveness and cost. Anesth Prog 48:3-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinknecht RA, Klepac RK, Alexander LD. (1973). Origins and characteristics of fear of dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 86:842-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Melamed BG, Hart J. (1970). A psychophysiological analysis of fear modification using an automated desensitization procedure. J Abnorm Psychol 76:220-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L. (2007). Hands-on help: computer-aided psychotherapy [Maudsley Monograph 49]. London, UK: Psychology Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom P, Coldwell SE, Getz T, Weinstein P, Ramsay DS. (1997). Four dimensions of fear of dental injections. J Am Dent Assoc 128:756-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton JT, Buck DJ. (2000). Anxiety and pain measures in dentistry: a guide to their quality and application. J Am Dent Assoc 131:1449-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton JT, Edwards JC. (2005). Psychometric properties of the modified dental anxiety scale: an independent replication. Community Dent Health 22:40-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanWijk AJ, Hoogstraten J. (2009). Anxiety and pain during dental injections. J Dent 37:700-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vika M, Skaret E, Raadal M, Ost LG, Kvale G. (2009). One- vs. five-session treatment of intra-oral injection phobia: a randomized clinical study. Eur J Oral Sci 117:279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.