Abstract

Following the ongoing increase in nonmarital fertility, policy makers have looked for ways to limit the disadvantages faced by children of unmarried mothers. Recent initiatives included marriage promotion and welfare-to-work programs. Yet policy might also consider the promotion of three generational households. We know little about whether multigenerational households benefit children of unwed mothers, although they are mandated for unmarried teen mothers applying for welfare benefits. Multigenerational households are also becoming increasingly common. Thus, using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (N = 217), this study examines whether grandparent-headed coresidential households benefit preschool-aged children’s school readiness, employing propensity score techniques to account for selection into these households. Findings reveal living with a grandparent is not associated with child outcomes for families that select into such arrangements but is positively associated with reading scores and behavior problems for families with a low propensity to coreside. The implications of these findings for policy are discussed.

Keywords: multigenerational households, nonmarital fertility, school readiness

The rise in nonmarital childbearing over the past several decades represents a dramatic change in the structure of American families. Today, 40% of all children are born to unmarried mothers (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2010). Such trends in nonmarital fertility have fueled major policy initiatives targeting single mothers. One such major policy initiative was the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which sought to encourage self-sufficiency and reduce reliance on government resources among welfare-receiving mothers by promoting marriage and welfare to work (Eshbaugh, 2008). In response to this historical legislation, social scientists have worked to understand the broad impact of these programs by exploring the significance of marriage and employment for the developmental outcomes of children in disadvantaged families (Acs, 2007; Lichter, Graefe, & Brown, 2003).

Yet welfare policies have the potential to influence family well-being through less direct avenues. One way is by encouraging the formation of multigenerational households. Such policies require adolescent mothers to live with an adult relative (national data indicate that more than three fourths live with a parent) and can lead mothers of all ages with young children, who are required to work but need child care assistance, to live with a grandparent (Acs & Koball, 2003; Gordon, 1999). These factors, combined with recent Census data showing nearly one in five children living with a never married mother is also living in a grandparent’s household, motivate this study. Specifically, we examine whether living in a grandparent headed household with a grandmother is beneficial to the development of children (aged 3–5 years) born to single mothers. We focus on this coresidential arrangement, rather than mother-headed coresidential households, to eliminate cases where coresidence occurs for the benefit of the grandparent (e.g., grandparent is ill, needs financial support). This is also a much rarer event. Census data indicate that less than 6% of never married mothers are coresiding with a grandparent in her own household (living with a grandfather only householder is also rare, representing 6% of all multigenerational households among never married mothers).

We focus on young children for two reasons. First, grandparent coresidence is most common early in life. For example, 28% of children younger than 5 years with unmarried mothers live in grandparent-headed households, versus 14% of children aged 6 to 14 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). Second, economic and developmental research and theory have suggested that investments in children’s early skill formation (school readiness) bring greater long-term returns than investments made at later developmental stages (Cunha & Heckman, 2006, 2007; Pianta, Cox, & Snow, 2007). Although coresidence during other stages of development can benefit children (e.g., grandparents can provide an important source of supervision for adolescents), this study aims to speak to policy debates on how to best limit the disadvantages often faced by children born to single mothers (DeLeire & Kalil, 2002; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Thus, we examine whether coresiding with a grandparent between birth and preschool promotes various dimensions of preschool children’s school readiness.

To fulfill this policy-oriented goal, this study pays special attention to the factors that potentially select families into coresidential households, such as maternal age, race, and welfare receipt. This approach helps disentangle whether the benefit or lack of benefit of grandparent coresidence for children’s school readiness is linked to factors associated with a family’s likelihood of forming a coresidential household. We pursue these objectives using propensity score techniques and a valuable source of intergenerational, nationally representative data: the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and matched Child Development Supplement (CDS).

Coresident Grandparents and Children’s Development

Presently, we know little about whether young children born to unwed mothers benefit from living in a multigenerational household. Yet the potential benefits may be great during this period—when child care demands are large, mothers are less experienced parents, and children are highly sensitive to environmental influences (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003). It is also during this period (compared with later stages) when parenting and family have the largest impact on children’s development (Alexander & Entwisle, 1988; Cavanagh & Huston, 2007). Thus, coresidence with a grandparent during this time may play an important role in promoting school readiness, helping launch children on positive trajectories (Pianta, Cox, & Snow, 2007).

Research on school-aged and adolescent children coresiding with a grandparent provides support for this expectation. This research finds that coresiding with a grandparent is associated with improvements in academic (e.g., literacy, test scores, high school completion), cognitive, and behavioral (e.g., depression, school conduct, smoking behavior, social adaptation) outcomes (DeLeire & Kalil, 2002; Dunifon & Kowaleski-Jones, 2007; Entwisle & Alexander, 1996; Gordon, 1999; Kellam, Ensminger, & Turner, 1977; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994; Pittman, 2007). The explanation for these findings is that grandparents contribute to household financial resources, provide assistance with household chores, supervise children, and model appropriate parenting behaviors, which can reduce mothers’ stress, improve the home environment, and provide children with important material resources (Baydar & Brooks-Gunn, 1998; Chase-Lansdale, Brooks-Gunn, & Paikoff, 1991; Smith, 2000; Stevens, 1984). Such mechanisms are also important for children during early childhood (Amato, 2005) and as such point to the pathways through which coresidence might benefit the development of children’s preschool school readiness skills.

Importantly, the findings from the literature on multigenerational households are not unequivocal, with several studies (e.g., Chase-Lansdale, Brooks-Gunn, & Zamsky, 1994; Foster & Kalil, 2007; Unger & Cooley, 1992) reporting negative associations between grandparent coresidence and child outcomes. These studies cite the role of increased family conflict over child rearing practices and privacy matters in coresidential households (Brooks-Gunn & Chase-Lansdale, 1991), outmoded parenting styles among grandparents (Bentley, Gavin, Black, & Tedi, 1999), and less maternal warmth (Black & Nitz., 1996) as mechanisms. One explanation for disparities in findings is that studies employ multivariate models that include different sets of controls. Another is that some studies explore the role of moderators (particularly race/ethnicity), discerning subgroup differences that are not observed in other studies (Foster & Kalil, 2007; Unger & Cooley, 1992). A third is they draw on different samples. For example, work by Black and Nitz (1996) and Chase-Lansdale et al. (1994) analyzed data from small samples of low-income, adolescent mothers.

A final potential reason that prior studies linking coresidence and child outcomes have produced inconsistent findings, and one that this study aims to delve deeper into, is the lack of attention to selection. Indeed, young children (compared with school-aged and adolescent children) who coreside with grandparents tend to be in families with a greater number of preexisting disadvantages (Chase-Lansdale et al., 1991), as is true of children born to unwed mothers. Not accounting for these disadvantages could lead to an underestimate of the benefits of multigenerational households or an overestimate of its negative consequences. Thus, this study takes steps to account for, and describe, the selection of young children born to unmarried mothers into coresidential households headed by grandparents.

Selection Into Multigenerational Households

Consideration of such selection factors is guided by economic frameworks. One emphasizes “independence effects” (Becker, 1991; Cherlin, 1992). Generally, this concept has been used as an explanation for why women with greater economic independence are less likely to marry, but this perspective can also be applied to coresidence. Mothers with fewer available resources may be more likely to form a coresidential household than a mother who could establish her own independent household and meet the financial demands of child care. Cost–benefit frameworks, which underscore the evaluation process that individuals undertake when considering living arrangements, echo this hypothesis. In this view, the costs associated with coresidence—lack of privacy, shared space—must be outweighed (or at least partially offset) by the benefits to both mothers and grandmothers of coresidence, such as proximity (i.e., to the grandchild), support, and economies of scale (Sigle-Rushton & McLanahan, 2002).

Indeed, previous research indicates that unmarried mothers who coreside are more disadvantaged and have access to few resources. Mothers in multigenerational families (compared with mothers in single-only households) are more commonly young, less educated, poor, and Black or Hispanic rather than non-Hispanic White (Hogan, Hao, & Parish, 1990; London, 2000; Sigle-Rushton & McLanahan, 2002; Tienda & Angel, 1982). Mothers cohabiting at the time of the child’s birth or who marry soon afterward (who often have more resources than unpartnered mothers) are also less likely than single mothers to form a multigenerational household (Sigle-Rushton & McLanahan, 2002). Additionally, the grandparent’s resources an play an important role. When the grandparent has more children or lives in extremely impoverished neighborhood, and thus has fewer resources to share, coresidence is less likely (Gordon et al., 1997). Finally, there is some indication that psychosocial resources matter, where women with greater levels of personal skills are more likely to establish independent households than women who lack such skills (Chase-Lansdale et al., 1994).

Yet the connection between mothers’ access to resources and decision to coreside may not be so straightforward. Employment opportunities might enable women to live independently but could also encourage coresidence so that women can receive child care assistance from parents. Resources such as child support, food stamps, and AFDC may facilitate independent living, but living arrangements may also shape women’s access to these resources (Acs & Koball, 2003; Gordon, 1999). Mothers who are currently cohabiting with a partner may feel less pressure to remain in their current situation if the relationship is low quality and they have an opportunity to live with their parents. Finally, grandmothers with more resources to provide the mother and child may perceive greater costs than benefits from a coresidential arrangement.

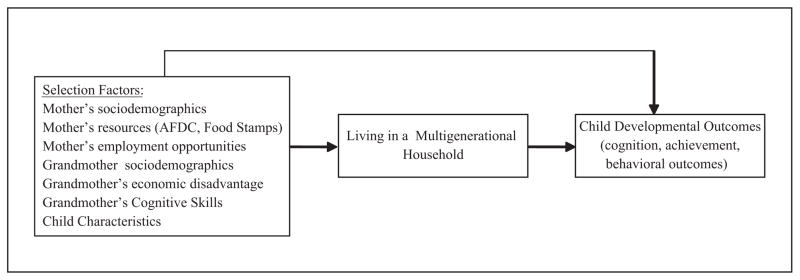

This complexity suggests the importance of identifying the factors selecting families into multigenerational households and disentangling these factors from estimates of the effects of coresidence on children’s school readiness. Thus, we examine a range of potential selection factors, including mothers’ sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race, education, and marital status), mothers’ resources and employment opportunities, grandmothers’ sociodemographic characteristics, economic disadvantage and cognitive and psychological skills, and child characteristics (gender, birth weight). These factors, and their links to coresidence and child outcomes, are depicted in the conceptual model (Figure 1), where selection factors are associated with the likelihood one coresides and child outcomes. Family-level process influenced by coresidence that impact child outcomes are not depicted because they are not tested.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model depicting links between selection factors and child developmental outcomes

Note: Selection factors may represent positive (e.g., employed mothers select into coresidential households) or negative selection (e.g., poor mothers select into coresidential households.). As such these factors can be both positively and negatively associated with child outcomes. Family-level mechanisms linking selection factors to child outcomes and multigenerational households to child outcomes are not shown

Timing and Race

As a final consideration, several studies suggest that the benefits of coresidence for children may vary by timing and race. For example, a study by Unger and Cooley (1992) of children aged 6 to 8 years found that although grandparent coresidence at the child’s birth is associated with fewer behavior problems, longer term coresidence has negative consequences for vocabulary test scores. The importance of timing has also been documented in a wide swath of other studies examining developmental processes (e.g., first year maternal employment on child cognition, family structure change during preschool on child behavior; Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2010; Cavanagh & Huston, 2007). Therefore, we consider differences between children who coresided around the time of birth, when an injection of resources could have powerful long-term consequences for children’s well-being (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997); after the first year; and continuously (since birth up to the assessment period), which might be associated with elevated conflict in the home and diminishing returns after the critical first year (Unger & Cooley, 1992).

A second complication is that studies have reported differences in the association between coresidence and child outcomes by race, although as with the studies reported above, findings are inconsistent. For example, Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones (2007) find that coresidence is associated with increased reading scores for White children, but not for Black children, and Foster and Kalil (2007) find that coresidence is associated with greater externalizing behavior problems for young Black children than for other children. Alternatively, others have found that Black children in multigenerational households exhibit fewer externalizing problems than White children (e.g., Thompson Entwisle, Alexander, & Sundius, 1992) and greater levels of prosocial behavior compared with mother-only families (Kellam et al., 1977). The reasons for these patterns and variable findings across studies are unclear, although one issue may be race-related differences in selection into coresidential households, reflecting unobserved factors that vary across samples. Although we cannot account for unobserved heterogeneity, such findings require that we test for racial differences in the association between the categories of coresidence and children’s school readiness.

Method

Data and Sample

This study draws on core data from the PSID and first wave of the CDS-I. The PSID is a longitudinal study composed of a representative sample of individuals and their coresident family members. When data collection for the PSID began in 1968, the study aimed to understand household economic growth. It has since followed participants at regular intervals, incorporating spouses, children, and others into the core sample as they entered households of original participants, making it an unparalleled source of intra- and inter-generational data. The 1997 addition of the CDS-I provides new information on PSID parents and assessments of their 0- to 12-year-old children, allowing us to consider a multitude of factors predating or concurrent with the child’s birth that may be associated with mothers’ selection into multigenerational households and children’s outcomes.

Of the 2,705 families selected for the CDS-I, 2,394 families (88%) and 3,563 children participated. The analytic sample for this study began with the 612 participating preschool aged children (ages 3 to 5 years). Excluding 42 children from the immigrant sample (who lacked family history data), 19 children whose 1997 primary caregivers were not their biological mothers, and 334 children whose mothers were married at the time of birth, the final analytic sample includes 217 children. This subsample, weighted using child-level weights, constitutes a representative sample of Black and White pre-school-aged children born to single mothers in the 1990s.

Measures

Household structure

Mothers reported yearly on their relationship to the household head (e.g., head of household, daughter of household head, etc.). Based on these reports, a yearly marker of coresidence with a grandparent since the child’s birth was created (1 = coresided, 0 = did not coreside). This yearly marker was used to group children into four mutually exclusive categories capturing different patterns of coresidence: coresided at birth (mother coresided with a grandparent within the interview year of the child’s birth and moved out before the 1997 assessment), coresided later (the mother coresided with a grandparent after the child’s first year), coresided continuously (the mother coresided continuously with the grandparent from the child’s birth to 1997), and never coresided. This marker was also used to calculate the number of reports of coresidence, a loose indicator of the duration of coresidence. The range on this measure for children aged 5 years in 1997 is 0 to 6 (based on data collected between 1992 and 1997); the range for children aged 3 years is 0 to 4. As noted, coresidential households are those where the grandparent is the household head. Although there are instances where mothers (or mothers’ husbands/partners) are heads, such households among this sample are uncommon. In 1997, 1% of mothers in this sample lived with a grandparent and were household heads.

Cohabitation

The yearly reporting of mothers’ relationship to the household head was also used to determine whether and when mothers were living with a romantic partner, particularly whether she cohabited at birth and/or cohabited in 1997. Unfortunately, when mothers and their partners were coresiding with an adult relative or grandparent who was household head, we were not always able to detect the presence of a cohabiting partner. This limitation, in combination with the yearly (not monthly) accountings of household members may partly explain our lower than average estimates for cohabitation (14%, whereas other estimates find that 40% of nonmarital births are to cohabiting women; Bumpass & Lu, 2000).

Marital history

Information is provided on the month and year of each marriage and divorce. These data were used in combination with data on the child’s birth month and year to create three marital history variables: married at the 1997 interview, married (after the birth) but divorced by the 1997 interview, and previously married (and divorced) before the focal child’s birth. This monthly data also determined mothers’ marital status at the time of the child’s birth.

Selection factors

To account for factors potentially associated with grandparent coresidence and children’s development, we include an array of measures. These include measures of maternal sociodemographic characteristics (race, education, age at birth), sources of maternal financial resources at the time of the child’s birth (maternal employment, child support, food stamp receipt, and AFDC receipt), mothers’ employment opportunities at the time of the child’s birth (county unemployment rate, region, and urbanicity), markers of maternal disadvantage growing-up (if the mother experienced poverty, grandmother received welfare, or mother experienced a residential move during high school), grandmothers’ sociodemographic characteristics (education, history of employment, if she was employed at the time of the child’s birth, age at first birth, number of live births, marital status at the time of the child’s birth), grandmothers’ psychological (future orientation, self-efficacy) and cognitive skills (IQ), and the grandmother’s family structure history (single at the mothers’ birth, experienced a family structure change). We also consider child characteristics (parity, low birth weight, and gender).

Other potential sources of selection, such as grandparent or mothers’ physical health, mothers’ relationship quality with the child’s father, local housing costs, proximity to grandparents, and state/local welfare regulations (Cohen & Casper, 2002; Sigle-Rushton & McLanahan, 2002) were unavailable (although low birth weight may proxy mothers’ health to some extent and urbanicity proximity to kin). Also, because income is measured as the total of all family members’ income, we cannot differentiate mothers’ wages from grandparents’ and therefore do not include a measure for maternal income at the time of the child’s birth. Side analyses with measures of income included, however, do not significantly alter the results. The appendix contains a full description of the measurement and coding of these variables.

Child outcomes

Six indicators of child development, each administered to children ages 3 and older in 1997 are examined. The Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery-Revised (WJ-R) Letter-Word subtest and WJ-R Applied Problems subtest are indicators of children’s academic achievement. The WJ-R subtests are designed to show children’s abilities in comparison to national averages for children the same age. The Letter Word subtest involves identifying letters and words and symbolic learning activities and measures reading skills. The Applied Problems subtest includes simple math problems and calculations and measures skill in mathematics. The Memory for Digit Span test from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition (Digit Scores) assesses children’s cognitive abilities, including short-term memory, concentration, and attention processes. Higher Digit Span scores indicate greater cognitive skill.

The Behavior Problem Index (BPI) Internalizing Score and BPI Externalizing Score measure children’s behavioral adjustment. The BPI is based on responses by the primary caregiver as to whether a set of 30 problem behaviors was often, sometimes, or never true of the target child. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to construct two subscales, internalizing problems (e.g., fearful or anxious; 13 items, α = .87) and externalizing problems (e.g., sudden mood changes and meanness toward others; 15 items, α = .90), which were created by taking the sum of the individual-level items that loaded on each factor. Higher BPI scores imply a greater degree of behavioral problems.

Finally, children’s socioemotional competence is measured by the Positive Behavior Scale, consisting of mothers’ ratings of how well 10 different statements (e.g., cheerful, thinks before acting) applies to her child (1 = not at all like your child, 5 = totally like your child). Responses were summed and averaged to create a composite (Cronbach’s α = .79, range 1–5).

Control variables

In the final multivariate models, we control for child’s age, measured in half-year increments. We also consider four factors that could be endogenous to coresidence, but if not controlled for, threaten to bias the estimated effect of coresidence on school readiness. These include income, maternal employment, additional schooling, and marital/relationship history (Furstenberg, Brooks-Gunn, & Morgan, 1987; Unger & Cooley, 1992). To assess the robustness of the initial associations, we add income (1997 income-to-needs; average income-to-needs since birth), maternal employment (whether the mother was employed in 1997), additional schooling (whether the mother reported additional schooling since the child’s birth), and the cohabiting/marriage variables described above to the final models.

Analysis Plan

The initial step in the analysis is to provide a descriptive picture of coresidence (e.g., when most families coresided and for how long) and whether mean-level differences in children’s school readiness varied by mothers’ history of coresidence. Examining the school readiness variables in a descriptive context provides a sense of whether coresiding with a grandparent may be beneficial to children’s development. Next, the mother, grandmother, and child selection variables are entered into a logistic regression model predicting the odds of having ever coresided with a grandparent between birth and the assessment period. This step determines whether such factors are associated with an increase or decrease in the odds of coresiding, or not at all. It is also a requisite modeling step for obtaining the propensity scores, which index the likelihood that a mother with a nonmarital birth will coreside with a grandparent based on observable covariates (Frank et al., 2008; Morgan & Harding, 2006).

In this analysis, the propensity scores are used as model weights in ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models that estimate children’s school readiness. This technique offers several advantages (see Crosnoe, 2009, and Frank et al., 2008, for similar approaches). First, more conventional matching techniques do not easily allow interactions between treatment variables and covariates (e.g., to test for race as moderators) and often result in a loss of large numbers of unmatchable cases. Propensity scores as model weights allow for the full sample to be retained, which is particularly important given our small sample size.

Second, weighting allows us to focus on the effect of coresidence for families with the greatest propensity to coreside. We do this by transforming the weights according to the following formula: w(t, x) = t + [(1 − t)/1 − e(x)], where e(x) is the propensity score and t is the treatment status. This transformation, capturing the treatment effect for the treated, weights children whose mothers ever coresided by a value of “1” and children whose mothers never coresided by their propensity scores, setting up a comparison where the untreated who look most like the treated (given higher propensities) are weighted more heavily (Hirano & Imbens, 2001).

Third, we can also estimate the counterfactual (e.g., treatment effect on the control), that is, the effect of coresiding for children’s school readiness if those who did not coreside had actually done so. To do so, we use the following formula: w(t, x) = t/e(x) + 1 − t. In this weighting scheme, children whose mothers never coresided are weighted by a value of “1” and mothers who ever coresided are weighted by their propensity score, allowing for a comparison where the treated who look most like the untreated (given their lower propensity) are weighted more heavily. Estimation of this latter effect allows us to make inferences regarding whether coresidence would equally—or perhaps even more greatly—benefit the development of children whose families have low propensities (and either barriers, or few incentives) to do so.

To ensure the validity of our propensity index, we estimate a series of balancing equations to ensure that the distribution of covariates between the treatment groups was similar. All variables in our logistic model balanced (grandmother’s marital status would not balance across groups and was omitted from the model). We also check for and trim extreme weights so no one exerts undue influence (Frank et al., 2008). The final step involves predicting children’s school readiness. We begin by estimating an unweighted model regressing the child outcomes on the categories of coresidence, controlling for child age. Next we add the model weights for the average treatment effect (the untransformed propensity score), the treatment on the treated, and the treatment on the control. Finally, we conduct a series of robustness checks by adding measures for employment, additional education, income, and marital/relationship status.

All models are estimated in Stata with the ICE program, a sequential regression multivariate imputation producing five fully imputed data sets (Royston, 2004). The micombine function, which provides corrected standard errors, is used to combine the five sets of model coefficients into one set of results. The variables used in the imputation include the focal independent variables, outcomes, covariates, and predictors of the propensity scores.

Results

Table 1 provides a descriptive picture of the 53% of mothers in our sample who had coresided and 47% who had not. The majority of mothers who coresided did so around the time of the child’s birth (26% of the full sample), reporting coresidence at 2.44 annual interviews. Additionally, 13% core-sided at a later point but for roughly the same amount of time (2.57 reports), and 14% coresided continuously. Mothers who coresided were younger, more commonly Black, and had less education. Those continuously coresiding, followed by those coresiding at birth, had the fewest resources (e.g., younger, more children, less education), although these mothers pursued additional education at relatively high rates (17%, 19%). For these two groups, coresidence might help mothers to continue their education and gain access to important resources. Mothers who moved in with their parent at some time after the child’s birth had more resources (e.g., higher levels of education, fewer children to care for) and rarely pursued additional schooling. These mothers also had the highest rates of marriage (37%) and cohabitation (30%) at the 1997 interview. For them, coresidence was likely a temporary way of shoring up resources before establishing independent households with a partner (Gibson-Davis, Edin, & McLanahan, 2005).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Selected Family Sociodemographic and Family/Household Structure Variables and Child Outcomes (n = 217).

| Coreside at Birth, Mean (SD) | Coresided Later, Mean (SD) | Continuous, Mean (SD) | Never Coresided, Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Mother age at birth | 20.22 (3.41) | 20.61 (3.97) | 19.38 (3.78) | 25.94 (5.87) |

| Mother race (White) | 0.63 (0.48) | 0.55 (0.50) | 0.61 (0.49) | 0.44 (0.50) |

| Income-to-needs 1997 | 1.86 (1.60) | 2.06 (1.54) | 1.61 (1.02) | 1.85 (1.96) |

| Child first birth | 0.70 (0.46) | 0.93 (0.26) | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.75 (0.43) |

| Mother employed 1997 | 0.76 (0.42) | 0.85 (0.35) | 0.88 (0.33) | 0.85 (0.35) |

| Additional education | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.17 (0.38) | 0.05 (0.22) |

| No high school degree | 0.25 (0.43) | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.51 (0.50) | 0.14 (0.34) |

| High school degree | 0.53 (0.40) | 0.32 (0.47) | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.57 (0.50) |

| Some college or more | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.30 (0.45) |

| Family/household structure | ||||

| Previously married | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.21 (0.41) |

| Divorced | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.05 (0.23) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.14 (0.35) |

| Cohabiting 1997 | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.30 (0.45) | — | 0.08 (0.25) |

| Married 1997 | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.37 (0.48) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.11 (0.32) |

| Cohabiting at birth | — | 0.10 (0.30) | — | 0.26 (0.43) |

| Reports of coresidence | 2.44 (1.56) | 2.57 (2.30) | 5.03 (1.35) | — |

| Child outcomes | ||||

| WJ-R Letter Word | 94.08 (12.21) | 96.50 (14.71) | 93.69 (13.03) | 94.69 (12.68) |

| WJ-R Applied Problems | 92.80 (18.62) | 94.94 (20.51) | 92.23 (14.02) | 100.16 (25.76) |

| Positive Behavior Scale | 4.01 (0.43) | 4.08 (0.53) | 4.26 (0.52) | 4.09 (0.40) |

| Externalizing Problems | 7.18 (3.07) | 7.16 (4.04) | 6.08 (4.11) | 7.26 (3.49) |

| Internalizing Problems | 2.13 (1.92) | 2.09 (1.99) | 1.74 (2.71) | 1.51 (1.76) |

| Weighted percentage | 25.80 | 12.68 | 14.16 | 47.37 |

| Weighted n | 56 | 31 | 27 | 103 |

Note: WJ-R = Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery–Revised; WISC = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition. Models estimated using child-level weight. WISC-Digit Scores not shown because this test did not adjust for child age. Multivariate models adjust for age-related differences in children’s Digit Scores.

As for children’s school readiness outcomes, the estimates in Table 1 suggest few academic advantages. For all categories of coresidence, children who experienced a coresidential household had lower Applied Problems scores than those who did not. There were no differences by coresidence for Letter Word. As for children’s behavior, however, children who coresided continuously (compared with all other categories) exhibited more positive behaviors and fewer externalizing problems. These children also had fewer internalizing behaviors than children in other coresidential households, although they had more than children who had never coresided.

The bivariate models suggest that coresiding with a grandparent may be associated both positively and negatively with child outcomes, but they also highlight the importance of considering the background factors that select mothers’ into multigenerational households, which could be linked to children’s achievement and behavior. The next step in the analysis to use multivariate logistic regression to identify and index, using propensity scores, the factors associated with women’s odds of coresiding with a grandparent following a nonmarital birth.

Selection Factors

The odds ratios from this logistic model appear in Table 2. Beginning with mothers’ sociodemographic characteristics, being non-White (odds ratio [OR] = 3.99) and employed (OR = 3.56) were associated with large increases in the odds of coresiding with a grandparent. Alternately, cohabiting at the time of the birth (OR = 0.01), having been previously married (OR = 0.45), or having a first birth (OR = 0.56) were also associated with decreased odds of having coresided. Mothers without high school degrees (OR = 5.36) and mothers with some college (OR = 5.42) were more likely to coreside than were mothers with a high school degree. Each unit increase in age at birth was associated with a 32% decrease in the odds of coresiding with grandparent.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios From Logistic Regression Models Predicting Whether Mother Ever Coresided With Grandparent (n = 217).

| Odds Ratio | SE | p > |t| | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Mother race (non-White) | 3.99 | 1.37 | .00 |

| No high school degree (high school) | 5.36 | 1.92 | .00 |

| Some college education | 5.42 | 2.28 | .00 |

| Mother age at birth | 0.68 | 0.03 | .00 |

| Employed at child’s birth | 3.56 | 1.17 | .00 |

| First birth | 0.56 | 0.18 | .07 |

| Previously married | 0.45 | 0.28 | .20 |

| Cohabiting at child’s birth | 0.01 | 0.00 | .00 |

| Maternal resources at birth | |||

| Child support | 1.24 | 0.44 | .54 |

| Food stamps | 9.91 | 4.08 | .00 |

| AFDC | 0.79 | 0.26 | .48 |

| Maternal employment opportunities | |||

| County unemployment rate | 0.97 | 0.06 | .62 |

| Region (south) | 0.75 | 0.28 | .44 |

| Urbanicity (more than 250,000 people) | 0.53 | 0.19 | .08 |

| Grandmother sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| No high school degree (high school degree) | 1.06 | 0.32 | .85 |

| More than high school education | 0.63 | 0.23 | .22 |

| Ever employed | 2.20 | 0.77 | .03 |

| Employed at grandchild’s birth | 0.25 | 0.26 | .40 |

| Age at first birth | 1.22 | 0.04 | .00 |

| Number of births | 0.87 | 0.06 | .06 |

| Economic disadvantage | |||

| Grandmother ever poor | 1.10 | 0.48 | .83 |

| Grandmother ever receive welfare | 4.26 | 1.78 | .00 |

| Residential move | 0.06 | 0.02 | .00 |

| Grandmother psychological/cognitive skills | |||

| IQ test score | 1.06 | 0.06 | .33 |

| Future-orientation/self-efficacy | 0.86 | 0.11 | .25 |

| Family structure of origin | |||

| Grandmother not married at birth | 2.80 | 0.94 | .00 |

| Family structure transition | 1.80 | 0.57 | .07 |

| Child characteristics | |||

| Child low birth weight | 23.48 | 12.85 | .00 |

| Child gender (male) | 1.44 | 0.43 | .25 |

| R2 | .59 | ||

Note: Model estimated using child-level weight.

As for maternal resources at birth, mothers who received food stamps were 9.91 times more likely to coreside than mothers who did not. AFDC and child support receipt were not significantly associated with the odds of ever coresiding. Measures of maternal employment opportunities were not statistically associated with coresidence, although these measures are fairly crude. Urbanicity was marginally associated with a lower odds of coresidence (OR = 0.53).

The grandmother sociodemographic measures indicate that the odds of coresiding were greater for women whose mothers were ever employed (OR = 2.20) and older at the age of first birth (OR = 1.22). Their odds were lower if their mothers had more children (OR = 0.87). Indicators of socioeconomic disadvantage in the family of origin reveal that mothers who grew up in welfare receiving households (OR = 4.26) during high school or whose mothers were single at the time of first birth (OR = 2.80) or had experienced at least one family structure transition (OR = 1.80) had a greater odds of coresiding. Mothers who experienced a residential move (OR = 0.06) during high school had a lower odds of coresiding with their mother. Having a low birth weight baby is associated with a large increase in the odds of coresidence (OR = 23.48). Grandmother psychological skills (future-orientation, self-efficacy), cognitive skills (IQ), education, and employment at the time of the child’s birth were not associated with the odds of coresidence.

These findings suggest that multigenerational households generally select on mothers who have the greatest needs (e.g., children are low birth weight and may need special attention, do not have ties to a former marital partner, have multiple children to care for, are working and likely need child care assistance, mother is young and has fewer labor market opportunities). Moreover, although grandmothers in coresidential households may have fewer children to divide their resources between and greater financial capital (as a result of their employment experience), they also experienced early disadvantage (e.g., received welfare, single at first birth). The next step in the analysis aims to tease out the linkage between coresidence, children’s school readiness, and the selection factors that could confound them.

Child Outcomes

In the OLS models, we use three weighting schemes. Model 1 is the unweighted findings. Model 2 uses the average treatment weight. Model 3 uses the treated on treatment weight, revealing the impact of coresidence focusing on those with the highest propensity to coreside. Model 4, using the same weight, adds factors potentially endogenous to coresidence that could affect children’s school readiness, but also lead to biased estimates of such associations if not included. Models 5 and 6 follow the same procedures using treatment on control weight, allowing us to focus on the impact of coresidence for those with the lowest propensity to coreside.

The results from models predicting Letter Word scores appear in Table 3. According to the unweighted model (Model 1) and Model 2, which applies the average treatment effect weight, coresidence of any type is not significantly associated with children’s early literacy skills. Turning to Model 3, coresidence is also not significantly associated with children’s early literacy skills among mothers with the highest propensity to coreside. This null association does not change with the inclusion of measures of marital status or human/financial resources. Model 5, however, reveals that among those with the lowest propensity to coreside, coresiding around the time of the birth (compared with not coresiding) was significantly associated with higher Letter Word scores among children (b = 10.46, SE = 2.14), which was 81% of a standard deviation. This association was robust to the inclusion of marital status and human/financial measures.

Table 3.

Results for WJ-R Letter Word Scores Predicted by Coresidential Household Categories Using Propensity Score Weights (n = 217).

| Model 1, B (SE) | Model 2, B (SE) | Model 3, B (SE) | Model 4, B (SE) | Model 5, B (SE) | Model 6, B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coresidence status | ||||||

| Coresided at birth | 2.40 (2.71) | 2.29 (3.03) | 0.52 (9.31) | −0.45 (6.32) | 10.46*** (2.14) | 9.53*** (2.60) |

| Coresided at later stage | 1.42 (2.82) | 1.33 (3.57) | 3.16 (3.84) | 1.67 (3.94) | 4.57 (6.70) | 0.88 (5.29) |

| Coresided continuously | 3.04 (2.89) | 3.48 (2.79) | 4.74 (3.55) | 1.96 (3.52) | 2.57 (2.59) | 2.31 (3.24) |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Married | — | — | — | 0.17 (3.84) | — | −4.95 (3.06) |

| Cohabiting | — | — | — | −8.04 (9.57) | — | 0.94 (14.62) |

| Divorced | — | — | — | −2.64 (4.26) | — | −1.43 (6.78) |

| Resources | ||||||

| Maternal employment | — | — | — | −2.36 (4.26) | — | −0.51 (5.72) |

| Additional schooling | — | — | — | 6.90+ (3.90) | — | −4.18 (3.06) |

| Income-to-needs | — | — | — | 1.97+ (1.05) | — | 1.79 (1.21) |

| Intercept | 91.76 | 91.47 | 90.04 | 90.55 | 91.76 | 90.22 |

Note: WJ-R = Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery–Revised. Model 1 is unweighted. Model 2 is weighted to estimate the average treatment effect. Models 3 and 4 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the treated. Models 5 and 6 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the control. Letter-Word scores adjusted for child age.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 4 presents the results for Applied Problems. Again, coresidence of any type was not significantly associated with children’s early math skills among the unweighted sample (Model 1), the sample weighted to reflect the average treatment effect (Model 2), or the sample weighted to reflect the effect of the treatment on the treated (Model 3). Adding marital status or human/financial capital measures to the model does not alter this association (Model 4). Model 5, weighted to reflect the effect of the treatment on the control, reveals a marginally significant association between coresiding at birth (compared with never coresiding) and children’s Applied Problems scores, but this association becomes null after measures of marital status are added (Model 6). As for children’s Digit Scores (Table 5), the results follow the same pattern, but in the model estimating the effect of the treatment on the control (Model 5), there is a significant association between coresiding at birth and children’s cognitive skills that becomes marginally significant (b = 0.72, SE = 0.74) once marital status measures are added to the model (Model 6). Measures of financial/human capital do not further alter this association.

Table 4.

Results for WJ-R Applied Scores Predicted by Coresidential Household Categories Using Propensity Score Weights (n = 217).

| Model 1, B (SE) | Model 2, B (SE) | Model 3, B (SE) | Model 4, B (SE) | Model 5, B (SE) | Model 6, B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coresidence status | ||||||

| Coresided at birth | −3.06 (3.68) | −3.43 (4.12) | −1.49 (6.29) | −3.51 (5.63) | 5.42+ (3.25) | 3.42 (3.54) |

| Coresided at later stage | 0.36 (4.79) | −0.06 (6.05) | 0.16 (6.06) | 0.86 (4.70) | 4.45 (6.19) | 2.17 (8.82) |

| Coresided continuously | −2.68 (4.41) | −3.41 (2.78) | −2.81 (4.79) | −6.42 (3.92) | −3.27 (4.21) | −5.01 (4.73) |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Married | — | — | — | 2.98 (6.15) | — | −6.37 (6.43) |

| Cohabiting | — | — | — | −27.67*** (6.54) | — | −9.06 (14.86) |

| Divorced | — | — | — | 0.41 (4.10) | — | −9.18 (14.85) |

| Resources | ||||||

| Maternal employment | — | — | — | −0.69 (4.13) | — | −2.96 (9.81) |

| Additional schooling | — | — | — | 2.05 (3.33) | — | −3.90 (3.60) |

| Income-to-needs | — | — | — | 1.50 (1.21) | — | 1.71 (1.53) |

| Intercept | 92.45 | 92.95 | 92.58 | 90.55 | 92.45 | 94.67 |

Note: WJ-R = Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery–Revised. Model 1 is unweighted. Model 2 is weighted to estimate the average treatment effect. Models 3 and 4 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the treated. Models 5 and 6 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the control. Applied Problems scores adjusted for child age.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Results for WISC Digit Scores Predicted by Coresidential Household Categories Using Propensity Score Weights (n = 217).

| Model 1, B (SE) | Model 2, B (SE) | Model 3, B (SE) | Model 4, B (SE) | Model 5, B (SE) | Model 6, B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coresidence status | ||||||

| Coresided at birth | 0.30 (0.39) | 0.27 (0.47) | 0.41 (0.65) | 0.05 (0.70) | 0.81 (0.54) | 0.72+ (0.43) |

| Coresided at later stage | 0.73 (0.52) | 0.60 (0.56) | 0.52 (0.68) | 0.52 (0.61) | 0.93 (0.98) | 0.74 (1.25) |

| Coresided continuously | 0.35 (0.50) | 0.30 (0.59) | 0.38 (0.66) | −0.20 (0.60) | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.41 (0.50) |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Married | — | — | — | −0.47 (1.37) | — | −0.16 (0.70) |

| Cohabiting | — | — | — | −1.55 (1.26) | — | −0.12 (1.66) |

| Divorced | — | — | — | −0.98 (0.89) | — | 0.31 (1.43) |

| Resources | ||||||

| Maternal employment | — | — | — | −0.31 (0.79) | — | −0.01 (0.48) |

| Additional schooling | — | — | — | 1.28+ (0.77) | — | −0.27 (0.47) |

| Income-to-needs | — | — | — | 0.22 (0.21) | — | 0.07 (0.12) |

| Intercept | −2.47 | −2.71 | −4.77 | −3.11 | −2.75 | −2.32 |

Note: WISC = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition. Model 1 is unweighted. Model 2 is weighted to estimate the average treatment effect. Models 3 and 4 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the treated. Models 5 and 6 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the control. Model controls for child age. Therefore, negative model constant reflects effect of not coresiding for children at age 0, for whom the WISC-Digit test (for obviously reasons) was not administered. Coefficients for child age in Models 1 and 2 were 1.61 and 1.66, respectively.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 6 presents results for models predicting children’s Positive Behavior. Again, there is no significant association between categories of coresidence and children’s positive behavior for Models 1 to 4. For Model 5 (weighted to capture the treatment on the control), coresiding around the birth is negatively associated with children’s positive behaviors (b = −0.32, SE = 0.09). This association remains with the inclusion of the controls (Model 6) and represents 72% of a standard deviation. In models not shown, there was no significant association between coresiding with a grandparent and children’s internalizing or externalizing scores for any model.

Table 6.

Results for Positive Behavior Scale Predicted by Coresidential Household Categories Using Propensity Score Weights (n = 217).

| Model 1, B (SE) | Model 2, B (SE) | Model 3, B (SE) | Model 4, B (SE) | Model 5, B (SE) | Model 6, B (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coresidence status | ||||||

| Coresided at birth | −0.10 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.14) | −0.07 (0.29) | −0.13 (0.18) | −0.32*** (0.09) | −0.32*** (0.08) |

| Coresided at later stage | −0.07 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.18) | −0.07 (0.38) | −0.05 (0.24) | 0.02 (0.29) | −0.02 (0.25) |

| Coresided continuously | −0.07 (0.11) | 0.04 (0.16) | −0.03 (0.29) | −0.11 (0.23) | −0.07 (0.11) | −0.07 (0.10) |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Married | — | — | — | 0.22 (0.26) | — | 0.24 (0.14) |

| Cohabiting | — | — | — | −0.68*** (0.19) | — | −0.01 (0.27) |

| Divorced | — | — | — | 0.18 (0.40) | — | 0.01 (0.31) |

| Resources | ||||||

| Maternal employment | — | — | — | 0.01 (0.25) | — | −0.06 (0.18) |

| Additional schooling | — | — | — | 0.22 (0.22) | — | 0.08 (0.12) |

| Income-to-needs | — | — | — | 0.06 (0.10) | — | −0.02 (0.04) |

| Intercept | 3.82 | 3.65 | 3.55 | 3.57 | 3.25 | 3.46 |

Note: Model 1 is unweighted. Model 2 is weighted to estimate the average treatment effect. Models 3 and 4 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the treated. Models 5 and 6 are weighted to estimate the effect of the treatment on the control. Model controls for child age.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Race Differences

Although our models account for the role of race in selecting mothers into coresidential households and children’s school readiness outcomes, there remains the possibility that mothers’ race plays an additional role in moderating the association between coresidence and children’s outcomes. To explore this possibility, we reestimated our OLS models adding interactions between race and the three categories of coresidence using the different weighting procedures.

We did not find significant differences by race in the association between coresidence and children’s Letter Word, Applied Problems, and Digit Scores or positive behaviors. We did find significant differences in children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors for those who continuously core-sided. In models weighted toward those with the greatest likelihood of coresiding (not shown), Black children continuously coresiding (vs. White children coresiding continuously) had significantly more internalizing and externalizing problems. In models weighted toward those with the lowest likelihood of coresiding, Black children who continuously coresided also had significantly higher levels of internalizing problems. Notably, the difference between Black and White children with lower propensities to coreside was smaller than the difference between Black and White children with higher propensities to coreside (33% of a standard deviation vs. 19%). Thus, in terms of coresiding with a grandparent continuously, there seemed to be negative consequences for Black children’s behavioral outcomes, especially among children most likely to live in with a grandparent.

Discussion

As nonmarital childbearing continues to increase, it is important to consider policy amenable ways of promoting the development of children born to single mothers. To this end, the attention of policy makers and researchers has largely been focused on welfare-to-work and marriage promotion initiatives. Yet promotion of coresidential households could benefit the children living in them, and welfare policy already mandates coresidence for adolescent mothers (Chase-Lansdale et al., 1991). Given the sparse empirical evidence to support or challenge such policies, this study aims to investigate such questions. Using a nationally representative sample of children born to single mothers, we examine whether coresiding with a grandparent is associated with preschool aged children’s school readiness. We also consider how selection factors into estimates of the link between multigenerational households and children’s school readiness and possible reasons that such households may actually have few positive benefits for families.

In general, our findings provide little evidence that coresidence among the families who are most likely to coreside benefits the school readiness of children. In particular, results from Models 1 to 4 for all child outcomes produced null findings. Insight into this pattern of null results comes from our investigation of selection mechanisms. The results from these selection models reveal that those with a higher likelihood of coresiding generally have the fewest resources and the greatest level of need. This was true for the grandparent generation as well. Thus, while the children in these high propensity households, who based on their background characteristics are also likely to be the targets of policy initiatives, could potentially benefit the most from such an arrangement, our findings suggest that these children do not, in fact, receive a developmental boost. Such findings underscore the significant resource deficiencies faced by these families that may not be alleviated simply by entering into a multigenerational household.

At the same time, our findings point to both positive and negative consequences of coresidence among those who are least likely to coreside (Models 5–6). Specifically, coresidence around the time of birth was significantly associated with higher literacy scores and, to a lesser extent, greater cognitive skills, but fewer prosocial behaviors. These findings echo recent research highlighting the critical significance of the first year of life for later outcomes (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2010). As with the findings in Models 1 to 4, these findings suggest that linkages between coresidence and child outcomes are tied to the background factors that select mothers into these families. In this case, multigenerational families with a low propensity to coreside have greater access to resources (yet modest compared with two parent biological families), providing children with an academic boost, although they may feel ambivalent about living with a parent (perhaps because the mother is older), resulting in conflict that reduces children’s positive behaviors. Reiterating the comment above, policies that target multigenerational households may not produce the intended benefits without considering the importance of these factors.

Finally, our analysis delved into the question of whether the effects of coresidence varied by race. We found that Black children living continuously in coresidential households had more behavioral problems than White children. These effects were greatest among Black children with the highest propensity to coreside. Such findings suggest that promoting long-term coresidence, particularly for Black children—who at a population level are more likely to coreside than White children—is not a promising strategy for supporting the well-being of children born to single mothers. In light of the previously noted findings, this finding emphasizes how policies that promote coresidence must be part of a holistic strategy that provides a dose of resources to these families (e.g., tax credits) and then helps mothers, perhaps through a combination of training, education, and subsidized child care, transition into independent households. The value of this strategy is underscored by the significant proportion of the coresiding mothers in our sample (particularly those selecting into coresidential households) who pursued additional education (Furstenberg et al., 1987; Gordon et al., 2004; Magnuson, 2007).

Although we argue that the negative, positive, and null associations between coresidence and children’s school readiness documented here represent important advances to this small body of literature, we must acknowledge several shortcomings of our study. First of all, our sample size is modest, which provides us with limited power to detect significant associations and may be a contributing factor to our null findings. This study should be followed up using a larger data set that also adequately represent Latinas, which our study does not—a growing population in the United States that needs to be considered in the context of research on multigenerational households and nonmarital fertility (Oropesa & Landale, 2004; Tienda & Angel, 1982).

Additionally, although our analysis was designed to make causal inferences, we cannot make the wholesale case for causality, which would require a random assignment experiment. Borrowing from the experimental research framework, however, our approach exploits the nonrandom nature of treatment and control groups, making inferences that reflect the real-world decisions of families. At the same time, we cannot account for unmeasured or unobserved variables, which remain a threat to the validity of our propensity score weights.

Several other issues must also be acknowledged. First, our descriptive findings reveal significant heterogeneity in the family structures that follow mothers’ time in multigenerational households (Bennet, Bloom, & Miller, 1995). Future research examining the connection among different family forms should not overlook the role played by coresidential households. Future research also should explore the mechanisms linking family structure and child well-being and the extent to which these mechanisms exist in multigenerational households. Also, our measures of child behavior were based on mother reports. Future research should look to data sources that contain observations of child behavior. Finally, future studies should consider heterogeneity (e.g., one vs. two grandparents; grandfather only) among grandparent-headed households.

In summary, findings from this study suggest that policies that promote multigenerational households as a means of improving the well-being of children born to single mothers will likely have little success if measures are not taken to improve the resources available to these families. If such an approach is adopted, our findings also provide evidence that such households can affect children’s academic development, although benefits are likely to be modest and could show negative consequences for children’s behavior, especially with long-term coresidence. Although these conclusions are preliminary and need to be tested more rigorously before they can inform policy, this study highlights ways that future research on multigenerational households could extend the analyses presented here, bringing researchers and policy makers one step closer toward to goal of promoting the well-being of children born to unmarried mothers.

Acknowledgments

Opinions expressed in this article reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the granting agencies.

The authors would like to thank Rachel Gordon for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received the support of grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 HD42849, Center Grant, and T32 HD007081, Training Grant) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Appendix

Descriptions of Other Variables for Propensity Score

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Mother characteristics | |

| Employed at child’s birth | Mother reported that she was working for pay the year the focal child was born (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Parity | Child was first birth (coded as 1) or higher order (coded as 0) |

| Maternal resource at birth | |

| Child support | Whether mother reported receiving any child support the same year of the focal child’s birth (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Food stamps | Whether mother reported receiving food stamps during the same year of the focal child’s birth (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| AFDC | Whether mother reported receiving AFDC during the same year of the focal child’s birth (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Maternal employment opportunities | |

| County unemployment rate | Continuous measure of the county unemployment rate for the year of the focal child’s birth |

| Region | Mother was living in the south (= 1) or some other region in the United States (= 0) during the year of the focal child’s birth. This binary division is because of small cell sizes for other regions |

| Urbanicity | Whether mother was living in urban area with a population greater than 250,000 (1 = yes, 0 = no) the year of the focal child’s birth |

| Grandmother characteristics | |

| Education | Dummy coded into three categories (less than high school education, high school degree, and some college) based on mother reports during year of focal child’s birth |

| Employment history | Whether grandmother reported that she was working for pay during the mother’s high school years (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Employment at focal child’s birth | Whether grandmother reported that she was working for pay the year the focal child was born (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Age at first birth | Continuous measure of grandmother’s age at first birth |

| Number of births | Continuous measure of number of live births born to grandmother |

| Economic disadvantage | |

| Grandmother history of poverty | Whether grandmother ever had an income-to-needs ratio below the federal poverty threshold for that year during the time that the mother was in high school (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Grandmother welfare history | Whether grandmother ever reported receiving welfare while the mother was in high school (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Residential move | Whether grandmother reported having moved at least once while mother was in high school (1 = yes, 0 = no) |

| Grandmother sociocognitive skills | |

| IQ test score | Continuous measure based on sentence completion test administered in 1972 to core data participants to test IQ (range = 0–13) |

| Future-orientation/self-efficacy | Heads (in 1972) and “wives” (in 1976) answered questions about their effaciousness and future orientation (e.g., they felt life would work out, preferred savings to spending, plan ahead). Based on the distribution of responses, scores were dichotomized (0, 1) and summed (0–6). Higher scores reflect greater future orientation/self-efficacy |

| Family structure of origin | |

| Family structure at mother’s birth | Whether grandmother was unmarried at the time of the mothers’ birth (0 = married, 1 = unmarried) |

| Family structure transition | Whether the mother experienced at least one family structure transition (as reported by the grandmother) since birth through age 17 years (0 = no transitions, 1 = one or more transitions) |

| Child characteristics | |

| Child low birth weight | 1 = low birth weight baby (below 5.5 pounds), 0 = not low birth weight |

| Child gender | 0 = male, 1 = female |

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Acs G. Can we promote child well-being by promoting marriage? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1326–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Acs G, Koball H. New Federalism: Issues and Options for States. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2003. TANF and the status of teen mothers under age 18. Series A, No. A-62. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K, Entwisle D. Achievement in the first two years of school: Patterns and Processes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. Marriage and Child Wellbeing: The Future of Children. 2005;15:75–96. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Brooks-Gunn J. Profiles of grandmothers who help care for their grandchildren in the United States. Family Relations. 1998;47:385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A treatise on the family. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett NG, Bloom DE, Miller CK. The Influence of nonmarital childbearing on the formation of first marriages. Demography. 1995;32:47–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley M, Gavin L, Black MC, Tedi L. Infant feeding practices of low-income, African-American, adolescent mothers: an ecological, multigenerational perspective. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:1085–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Nitz K. Grandmother co-residence, parenting, and child development among low-income, urban teen mothers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;18:218–226. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00168-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein M, Bradley R. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Chase-Lansdale PL. Children having children: Effects on the family system. Pediatric Annals. 1991;20:467–481. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19910901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Han WJ, Waldfogel J. First-year maternal employment and child development in the first 7 years (Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development) Vol. 75. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, Lu HH. Trends in cohabitation and implications for children’s family contexts in the United States. Population Studies. 2000;54:29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh S, Huston A. The timing of family instability and children’s social development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1258–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J, Paikoff RL. Research and programs for adolescent mothers: Missing links and future promises. Family Relations. 1991;40:396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Brooks-Gunn J, Zamsky ES. Young African American multi-generational families in poverty: Quality of mothering and grandmothering. Child Development. 1994;65:373–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. Family, divorce, and remarriage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Casper L. In whose home? Multigenerational families in the United States, 1998–2000. Sociological Perspectives. 2002;45:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Low-income students and the socioeconomic composition of public schools. American Sociological Review. 2009;74:709–730. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuhna F, Heckman J. Formulating, identifying, and estimating the technology of cognitive and noncognitive skill formation. Journal of Human Resources. 2006;43:738–779. doi: 10.3982/ECTA6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha F, Heckman J. The technology of skill formation. Economics of Human Development. 2007;97:31–47. [Google Scholar]

- DeLeire TC, Kalil A. Good things come in threes: Single-parent multigenerational family structure and adolescent adjustment. Demography. 2002;39:393–413. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Brooks-Gunn J. Consequences of growing up poor. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon R, Kowaleski-Jones L. The influence of grandparents in single mother families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:465–481. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle D, Alexander KL. Family type and children’s growth in reading and math over the primary grades. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh E. Potential positive and negative consequences of coresidence for teen mothers and their children in adult-supervised households. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2008;17:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM, Kalil A. Living arrangements and children’s development in low-income White, Black, and Latino families. Child Development. 2007;78:1657–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank K, Sykes G, Anagnostopoulos D, Cannata M, Chard L, Krouse A, McCrory R. Does NBPTS certification affect the number of colleagues a teacher helps with instructional matters? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2008;30:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Brooks-Gunn J, Morgan S. Adolescent mothers in later life. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM, Edin K, McLanahan S. High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1301–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R. Multigenerational coresidence and welfare policy. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:525–549. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2008. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Imbens GW. Estimation of causal effects using propensity score weighting: An application to data on right heart catheterization. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001;2:259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Hao L, Parish WL. Race, kin networks, and assistance to mother-headed families. Social Forces. 1990;68:797–812. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Ensminger ME, Turner RJ. Family structure and the mental health of children. Concurrent and longitudinal community-wide studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1977;34:1012–1022. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770210026002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Graefe DR, Brown B. Is marriage a panacea? Union formation among economically disadvantaged unwed mothers. Social Problems. 2003;50:60–86. [Google Scholar]

- London RA. The interaction between single mothers’ living arrangements and welfare participation. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2000;19:93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson K. Maternal education and children’s academic achievement during middle childhood. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1497–1512. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SL, Harding DJ. Matching estimators of causal effects: Prospects and pitfalls in theory and practice. Sociological Methods and Research. 2006;35:3–60. [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa R, Landale N. The future of marriage and Hispanics. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:901–920. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Cox MJ, Snow KL. School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accountability. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman LD. Grandmothers’ involvement among young adolescents growing up in poverty. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:89–116. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4:227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sigle-Rushton W, McLanahan S. The living arrangements of new unmarried mothers. Demography. 2002;39:415–433. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2000. Who’s minding the kids? Child care arrangements: Fall 1995; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JH. Black grandmothers’ and Black adolescent mothers’ knowledge about parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1017–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Entwisle D, Alexander K, Sundius MJ. The influence of family composition on conformity to the student role. American Educational Research Journal. 1992;29:405–424. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda M, Angel R. Headship and household composition among Blacks, Hispanics, and other Whites. Social Forces. 1982;61:508–531. [Google Scholar]

- Unger D, Cooley M. Partner and grandmother contact in Black and White teen parent families. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13:546–552. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90367-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Families and living arrangements. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hh-fam.html.