Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) remains a major clinical problem with many patients having continuing systemic inflammatory disease resulting in progressive erosive damage and high levels of disability. A range of pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 are involved in RA pathogenesis; these cytokines can be specifically inhibited by biological agents. Tocilizumab (TCZ) is a recombinant humanized anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, administered monthly by intravenous infusion that prevents IL-6 signal transduction. There is strong evidence that it is both clinically efficacious and cost-effective. There have been several key clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of TCZ in RA patients. We review five Phase II trials and seven Phase III trials enrolling a total of 626 and 5268 RA patients respectively. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria were used as the primary or secondary outcome measure in all trials. Overall these trials demonstrated that TCZ was effective in the treatment of RA in a number of patient groups, including those with an inadequate response to methotrexate (MTX) or TNF inhibition. TCZ use, both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX, improved the signs and symptoms of RA within several weeks of commencing treatment. Additionally, TCZ was shown to reduce radiological disease progression and improve physical function, both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX. A 5-year extension study demonstrated that TCZ sustained good long-term efficacy and safety profiles. TCZ was generally well tolerated. Although its use increased the risk of an adverse event, these were usually mild to moderate in severity and treatment did not increase the risk of a serious adverse event in comparison to controls. Due to moderate increases in serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoproteins and serum transaminases seen in those patients treated with TCZ, as well as severe neutropenia in some, regular blood monitoring of full blood count, liver function and lipids is recommended. Given its clinical efficacy in the treatment of RA, TCZ may be beneficial in the treatment of other autoimmune diseases where IL-6 plays a role in the inflammatory cascade.

Keywords: tocilizumab, rheumatoid arthritis, review, IL-6

Background

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory autoimmune disease causing a symmetrical polyarthritis of the large and small joints. Affecting 0.5%–1.0% of the population in the developed world, it typically presents between the ages of 30–50 years, is 2.5 times more common in women than men, and is clinically characterized by joint pain, stiffness and swelling due to synovial inflammation and effusion.1–3 Patients may develop multiple systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, anemia, anorexia, and osteoporosis, and show an elevation of acute-phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).3–6 The disease can lead to a fluctuating progressive course that may result in joint destruction, deformity, disability and premature death.7

Although not fully understood, the etiology of RA is believed to be multifactorial, resulting from interactions between genetic and environmental factors. One theory postulates that a triggering event, possibly autoimmune or infectious in origin, initiates joint inflammation which then precipitates a host of complex immune responses, eventually leading to the joint destruction and systemic complications seen in RA.1,2 Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 have all been shown to play an important role in disease pathogenesis in RA.3,5,8

Managing RA

Treatments used in RA include disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and more recently, biological agents. Traditionally, first-line treatment incorporates conventional DMARDs that relieve inflammatory processes and can slow disease progression.9,10 These include corticosteroids, methotrexate (MTX), leflunomide, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine.11 For patients with an inadequate response to conventional DMARDs, biological agents may be indicated. Biological therapies include the TNF-α inhibitors infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, certolizumab and etanercept; the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra; the selective modulator of T-cell activation abatacept; and the chimeric auto CD20 B-cell depleting agent rituximab.11,12

Following over a decade of use, anti-TNF-α therapy is now well established as an effective treatment option for RA, especially in patients who experience an inadequate response to DMARDs, including MTX.13,14 Despite this, a significant proportion of patients have a partial but incomplete response (20%–40%) to anti-TNF-α therapy.15 Tocilizumab (TCZ), also known as Actemra® or RoActemra®, was introduced as a new approach for the treatment of RA, targeting the IL-6 pathway.16 It has been approved for use in RA in Europe, the United States, Japan and Canada, amongst others.17

IL-6

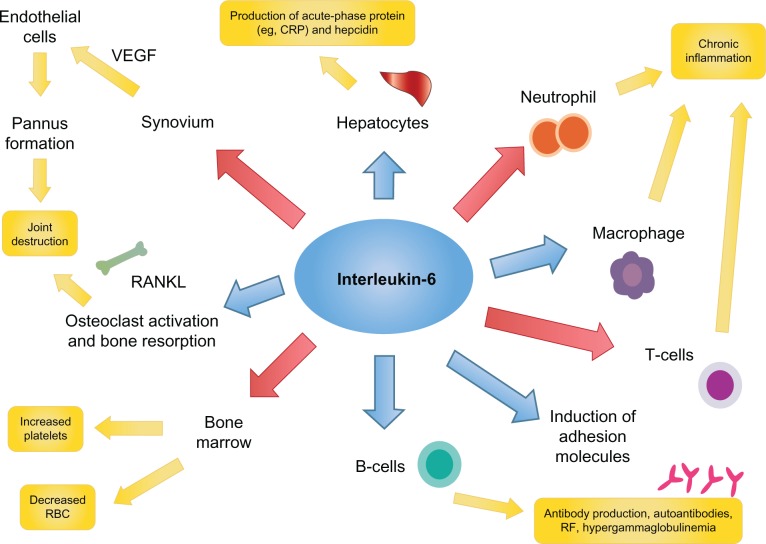

IL-6 is a 26 kDa glycopeptide whose gene is found on chromosome 7.18 It was first cloned in 1986 by Hirano et al.19 Like TNF-α, IL-6 is a pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine with a variety of biologic effects; regulating the immune response, inflammation, bone metabolism, hematopoiesis, and stimulating chemokine production and adhesion molecules in lymphocytes, including acute-phase proteins in hepatocytes (Figure 1).20–26 IL-6 is produced by lymphocytes, monocytes, fibroblasts, synoviocytes and endothelial cells.20–22,26

Figure 1.

Interleukin-6 activates a number of key inflammatory pathways.

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; RBC, red blood cells; RF, rheumatoid factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

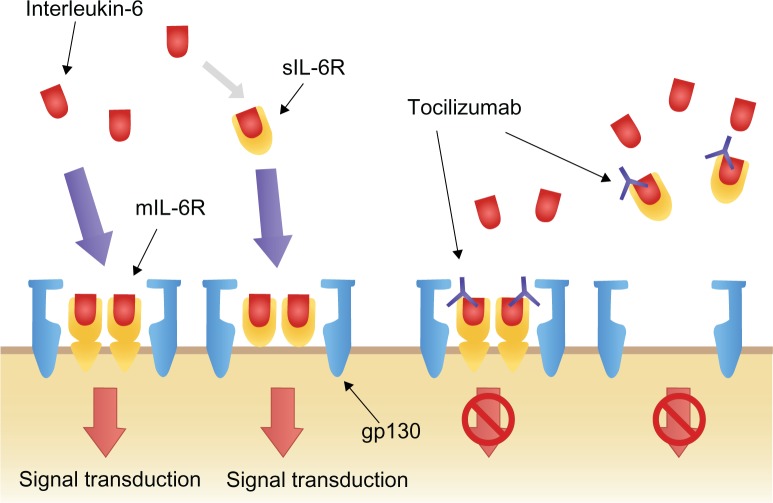

IL-6 signal transduction

IL-6 exerts its biological activity through two differing IL-6 driven signaling pathways, involving either a membrane bound IL-6 receptor (mIL-6R), or soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R). IL-6 signaling primarily occurs through the mIL-6R via two signal-transducing glycoprotein 130 (gp130) subunits.18,22,27–29 When IL-6 binds to mIL-6R, the homodimerization of gp130 is induced and a high-affinity functional receptor complex of IL-6, IL-6R, and gp130 is formed. In contrast, sIL-6R, lacking the intracytoplasmic portion of mIL-6R, is produced either by the enzymatic cleavage of mIL-6R or by alternative splicing. sIL-6R can bind with IL-6 and then the complex of IL-6 and sIL-6R can form a complex with gp130 (Figure 2).18,22,27–29

Figure 2.

Interleukin-6 signal transduction and blockage by tocilizumab.Reprinted from Biologics, volume 2, Okuda Y, Review of tocilizumab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, pages 75–82, Copyright © 2008, with permission from Dove.26

Abbreviations: gp130, glycoprotein 130; mIL-6R, membrane-bound interleukin-6 receptor; sIL-6R, soluble interleukin-6 receptor.

IL-6 in RA

IL-6 contributes to the pathogenesis of RA by promoting the activation of T-cells and the differentiation of B-cells into immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells.25–27 It is produced in large quantities by synovial cells and macrophages in patients with RA.25,30 Higher levels of IL-6 and sIL-6R have been found in the serum of RA patients, and levels of IL-6 and sIL-6R have been shown to correlate with both RA disease activity and radiological joint damage.31,32

Enhanced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 allows IL-6 to promote the infiltration of inflammatory cells into synovial tissue, and to act synergistically with TNF-α and IL-1 to promote angiogenesis as a result of increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).33 This increase in VEGF also stimulates pannus formation.18,34 Overproduction of IL-6 induces acute-phase proteins (including CRP and serum amyloid A) and contributes to the systemic manifestations of RA though hepcidin production (anemia), its potent action on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (fatigue), and through its impact on bone metabolism (osteoporosis).18,34 IL-6 may also contribute to the induction and maintenance of the autoimmune process through B-cell modulation and Th17 cell differentiation.18 Taken together, the number of potential mechanisms by which IL-6 may mediate the systemic and articular features of RA, make it an ideal target for the treatment of RA.12

TCZ

TCZ is a recombinant humanized anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, administered monthly by intravenous infusion (IV) that prevents IL-6 signal transduction ( Figure 2).16,21 By binding selectively and competitively to both mIL-6R and sIL-6R, TCZ prevents the dimerization of gp130 on the cell membrane and therefore blocks the pro-inflammatory effects of IL-6.16,21 Furthermore, TCZ has the capacity to dissociate IL-6/IL-6R complexes that have already formed.16,21

TCZ is approved in Europe and the United States for the treatment of moderate to severe RA in adult patients who have responded inadequately or have been intolerant to previous therapy with one or more DMARDs or TNF inhibitors.5,35

The objective of this article is to review the key studies of the use of TCZ in RA, addressing efficacy, tolerability and adverse events (AEs).

Key studies of TCZ

Introduction

There have been several key clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of TCZ in RA patients. Numerous primary end-points have been used and include the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria (ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 are defined by a 20%, 50%, or 70% clinical improvement from baseline after treatment respectively).36 Other endpoints include the European League Against Rheumatism and the Disease Activity Score of 28 joints (DAS28) improvement criteria;37 the patients’ and physicians’ global assessment of disease activity; the patient’s assessment of pain; the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disease Index (HAQ-DI) score;38 and the acute-phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein [CRP]).

Phase I/II clinical studies

Monotherapy

A UK Phase I/II study was performed by Choy et al in 2002.23 This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial was conducted in 45 patients with active RA as defined by the ACR revised criteria. The study aimed to determine the safety and efficacy of TCZ in single doses. Patients were sequentially allocated to receive one of four single dose cohorts of TCZ (0.1 mg/kg, 1.0 mg/kg, 5.0 mg/kg, or 10.0 mg/kg) or placebo. The primary efficacy endpoint was meeting the ACR20 response criteria 2 weeks after treatment. The ACR20 is considered to be a powerful discriminator between active and placebo treatments.

Choy et al found a significant treatment difference between the TCZ 5.0 mg/kg group and the placebo group, with 55.6% of the TCZ group achieving an ACR20 response compared to 0% in the placebo group. The ESR and CRP values fell significantly in the TCZ 5.0 mg/kg and 10.0 mg/kg groups, normalizing after 2 weeks of treatment. The only AEs noted, were considered to be mild to moderate in severity and were found in approximately equal amounts in both the treatment and placebo groups. No severe AEs were attributed to TCZ. They concluded that inhibition of IL-6 significantly improved the signs and symptoms of RA and normalized acute-phase reactants.23

A Japanese Phase I/II study by Nishimoto et al in 2003 aimed to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of multiple infusions of TCZ in patients with RA. Using an open-label trial, 15 patients with active RA, as defined by the ACR criteria, were administered three doses of TCZ IV at doses of 2 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg, or 8 mg/kg, every 2 weeks for 6 weeks. They evaluated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and clinical efficacy of TCZ. Patients with no safety concerns in regard to TCZ were continued on treatment and reassessed at 6 months.

This study showed that the half-life (T1/2) of TCZ increased with repeated and increased doses. Those given 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg TCZ showed a tendency to accumulate TCZ in the blood. In those in whom TCZ levels were detectable in the blood at trough levels, objective inflammatory indicators such as CRP, ESR, and serum amyloid A were completely normalized at 6 weeks, with no statistically significant difference in efficacy amongst the three dose groups. Their findings indicated that IL-6 was a major cytokine responsible for the acute-phase protein production seen in vivo in patients with RA.

Although this was an open-label study, ACR20 and ACR50 response criteria measurements were also assessed. They found that at 6 weeks post-treatment, 60% and 13% of patients achieved ACR20 and ACR50 respectively, and in those that continued on treatment, at 6 months 86.7% and 33.5% achieved ACR20 and ACR50 respectively. TCZ was well-tolerated at all doses with no difference in the frequency of AEs between these groups, and no severe AEs were attributed to TCZ. No new observations of antinuclear antibodies or anti-DNA antibodies, and no anti-TCZ antibodies were detected.

Phase II studies

Monotherapy – previous DMARD failure

A Japanese late Phase II multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of TCZ monotherapy in patients with RA.39 One hundred sixty-four RA patients with an inadequate response to one or more DMARDs or immunosuppressants, were randomized into one of three treatment arms; 3 months of IV infusions every 4 weeks of either TCZ 4 mg/kg, TCZ 8 mg/kg, or placebo infusions. The clinical responses were measured at 3 months using the ACR response criteria and the DAS28 improvement criteria. The mean number of DMARDs tried prior to entry to the trial was between four and five, and the mean duration was 8 years, implying established disease.39

Patients treated with TCZ showed a reduction in disease activity in a dose-dependent manner. At 3 months, an ACR20 response was achieved in 57% and 78% of the 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg TCZ groups respectively, compared with only 11% in the placebo group. The 8 mg/kg TCZ dose led to a significantly greater ACR20 response compared to the 4 mg/kg TCZ and placebo groups (P = 0.002 and P < 0.001, respectively). An ACR50 response was seen in 40% of patients treated with 8 mg/kg TCZ compared to only 1.9% in the placebo group (P < 0.001). The ACR70 response was also found to be superior in the 8 mg/kg group compared to the placebo group (16.4% versus 0.0% respectively, P = 0.002). Evaluation using the DAS28 criteria showed a good or moderate response in 90.9% of the 8 mg/kg TCZ group. Complete normalization of the CRP level was observed in 26% and 76% of the TCZ 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg groups respectively, compared to only 1.9% of the placebo group. Nishimoto et al concluded that treatment with TCZ was generally well-tolerated and significantly reduced the disease activity of RA.39

Monotherapy – no prior treatment failure

The STREAM extension study (long-term safety and efficacy of TCZ, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, in monotherapy, in patients with RA)40 was an open-label, long-term extension trial following on from the initial 3-month randomized controlled Phase II trial.39 This trial aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 5-year TCZ monotherapy in patients with refractory RA. Of the 163 patients in the initial late Phase II trial, 143 patients received infusions of 8 mg/kg TCZ monotherapy every 4 weeks. Concomitant therapy with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and/or oral prednisolone (maximum 10 mg daily) was permitted. Again the clinical responses were measured using the ACR criteria and DAS28 improvement criteria at 5 years.40

At 5 years, 84.0%, 69.1%, and 43.6% of the patients achieved ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 improvement respectively, and 55.3% achieved DAS28 remission (defined as DAS28 < 2.6). Of the patients receiving corticosteroids at baseline, 88.6% were able to decrease their corticosteroid dose and 31.8% to discontinue them altogether. Nishimoto et al concluded that TCZ demonstrated sustained long-term efficacy.40

Combination therapy – previous DMARD failure

The European CHARISMA study (Chugai humanized anti-human recombinant IL-6 monoclonal antibody study) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial investigating the safety and efficacy of multiple infusions of TCZ, both alone and in combination with MTX.14 This 16-week trial included 359 patients with active RA and an inadequate response to 4 weeks of treatment with MTX. Patients received treatment every 4 weeks and were randomized to one of seven treatment arms: TCZ at doses of 2 mg/kg, 4 mg/kg, or 8 mg/kg either as monotherapy with placebo or in combination with MTX, or MTX plus placebo.14

An ACR20 response at week 16 was achieved in 61% and 63% of patients receiving 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg TCZ plus placebo (TCZ monotherapy) respectively, compared with only 41% of patients receiving MTX plus placebo (MTX monotherapy) (P < 0.05). In those patients treated with TCZ plus MTX (TCZ combination therapy), an ACR20 response was achieved by 63% and 74% in the TCZ 4 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg groups respectively. TCZ combination therapy demonstrated superior efficacy compared with MTX monotherapy, with a statistically significant ACR50 and ACR70 response at either 4 mg/kg or 8 mg/kg of TCZ plus MTX (P < 0.05).14

In all patients, except those receiving TCZ 2 mg/kg, a dose-related reduction in the DAS28 was observed from week 4 onwards. The majority of patients who received 8 mg/kg of TCZ showed a normalization of the inflammatory markers, CRP and ESR. The CHARISMA study group concluded that TCZ was highly efficacious in decreasing disease activity in RA.14

Phase III trials

Seven Phase III clinical trials were performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety profile of TCZ in patients with RA; these are summarized in Tables 1–4.10,41–46

Table 1.

Key trials of tocilizumab

| Trial | Year | Patients | Study duration (weeks) | Design | Population | Disease duration (years) | Prior treatment | Treatment arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMURAI45 | 2007 | 306 | 52 | X-ray reader-blind, open-label, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Mod severe RA | 2 | Failed ≥ 1 DMARD | 1. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly |

| No biologic failure | 2. Conventional DMARD | |||||||

| SATORI42 | 2008 | 125 | 24 | Randomized, double-blind, multicenter, controlled trial | Mod severe RA | 9 | Inadequate response to low dose MTX | 1. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + placebo MTX |

| No biologic failure | 2. MTX + placebo TCZ monthly | |||||||

| OPTION43 | 2008 | 623 | 24 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial | Mod severe RA | 8 | Failed ≥ 1 DMARD/MTX | 1. TCZ 4 mg/kg monthly + MTX |

| 2. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + MTX | ||||||||

| No biologic failure | 3. Placebo + MTX | |||||||

| RADIATE44 | 2008 | 499 | 24 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Mod severe RA | 13 | No prior MTX failure | 1. TCZ 4 mg/kg monthly + MTX |

| Biologic failure | 2. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + MTX | |||||||

| 3. Placebo monthly + MTX | ||||||||

| TOWARD10 | 2008 | 1220 | 24 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study | Mod severe RA | 10 | No prior biologic. Can have conventional DMARD or immunosuppressive | 1. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly |

| 2. Placebo (DMARD) | ||||||||

| AMBITION41 | 2010 | 673 | 24 | Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel study | Mod severe RA | 6 | No previous MTX or biologic failure | 1. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly |

| 2. Escalating MTX | ||||||||

| LITHE46 | 2011 | 1196 | 104 | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial | RA < 5 years | 9 | Inadequate response to MTX No previous biologic failure | 1. TCZ 4 mg/kg monthly + MTX |

| 2. TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + MTX | ||||||||

| 3. Placebo monthly + MTX |

Abbreviations: DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Table 4.

Adverse events in Phase III trials

| SAMURAI45

|

SATORI42

|

OPTION43

|

RADIATE43

|

TOWARD10

|

AMBITION39

|

LITHE46,*

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | TCZ 4 mg/kg | TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | TCZ 4 mg/kg | TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | TCZ 4 mg/kg | TCZ 8 mg/kg | Placebo | |

| Any AEs | 89% | 82% | 92% | 72% | 71% | 69% | 63% | 87% | 84% | 81% | 73% | 61% | 80% | 78% | 324 | 325 | 280 |

| Serious AEs | 18% | 13% | 7% | 5% | 6% | 6% | 6% | 2% | 5% | 3% | 8% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 13 | 12 | 10 |

| AEs leading to death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3% | 0.5% | 1.0% | 0.4% | – | – | – |

| AEs leading to withdrawal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | 6% | 6% | 5% | 4% | 2% | 4% | 5% | – | – | – |

| Serious infections | 5% | 4% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 5% | 3% | 3% | 2% | – | – | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| TB infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – |

Notes:SAMURAI, SATORI and OPTION were studies with tocilizumab monotherapy. RADIATE, TOWARD, AMBITION and LITHE were tocilizumab plus methotrexate.

LITHE reported per 100 patient years.

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; TB, tuberculosis; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Monotherapy – no prior treatment failure

The AMBITION study (Actemra versus MTX double-blind investigative trial in monotherapy) aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of TCZ monotherapy versus MTX in patients with moderate to severe active RA.41 This 24-week, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group trial randomized 673 patients who had not previously failed MTX or biologics treatment to receive either TCZ 8 mg/kg monotherapy every 4 weeks, oral MTX monotherapy, or placebo for 8 weeks followed by TCZ 8 mg/kg every 4 weeks. Those receiving MTX monotherapy started at a dose of 7.5 mg/week and were titrated to 20 mg/week within 8 weeks. The primary efficacy endpoint was meeting the ACR20 response criteria 24 weeks after treatment.41

Approximately 66% of the patients entering this trial were MTX treatment naïve. At 24 weeks, the intention to treat analysis demonstrated that patients treated with TCZ monotherapy had a statistically superior ACR20 compared to those treated with MTX (69.9% versus 52.5%, respectively, P < 0.001). The proportion of ACR50 (44.1%) and ACR70 (28.0%) responders at week 24 was also statistically superior in those treated with TCZ compared with the MTX group. DAS28 remission was achieved in 33.6% of the TCZ treated group compared to 12.1% in those treated with MTX. By week 24 the TCZ group were five times more likely to achieve DAS28 remission than the MTX group (odds ratio [OR] 5.8; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.3, 10.4). With respect to laboratory parameters, by week 12 the mean CRP level was within the normal range in the TCZ group, whereas levels remained elevated in the MTX group.41

The AMBITION study group concluded that TCZ monotherapy was superior to MTX monotherapy in RA patients for whom treatment with MTX or biologics had not previously failed.41

Monotherapy – DMARD failure

The SATORI study (study of active-controlled TCZ monotherapy for RA patients with inadequate response to MTX) investigated the clinical efficacy of TCZ monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe active RA with an inadequate response to 8 weeks of low dose MTX.42 This 24-week multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial allocated 125 RA patients to receive either TCZ 8 mg/kg plus MTX placebo (TCZ monotherapy) or TCZ placebo plus MTX 8 mg/week (MTX monotherapy/control) every 4 weeks. The clinical responses were measured using the ACR criteria and the DAS28 response criteria. Serum VEGF levels were also monitored.42

At week 24, the ACR20 response was significantly higher in the TCZ group compared to the MTX treated group (80.3% versus 25.0%, P < 0.001). The ACR50 and ACR70 responses were also significantly higher in the TCZ group at all time points from 4 weeks onwards compared to the MTX group (49.2% versus 10.9% and 29.5% versus 6.3%, respectively, P < 0.001). Similarly, the reduction in DAS28 was greater for the TCZ group (P < 0.001). TCZ also caused a significantly greater reduction in VEGF levels compared with MTX (P < 0.001).42

The SATORI study group concluded that TCZ monotherapy was well- tolerated and provided an excellent clinical benefit in active RA patients with an inadequate response to low dose MTX.42

Combination therapy – DMARD failure

The TOWARD study (the TCZ in combination with traditional DMARD therapy study) was a large multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigating the efficacy and safety of TCZ combined with conventional DMARDs in patients with moderate to severe active RA.10 This study aimed to represent a diverse clinic population by allowing patients to enroll on the study if they were taking any stable single or multiple agent conventional DMARD, rather than just MTX. Permitted conventional DMARDs included MTX, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, parenteral gold, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, and leflunomide. Patients who had an incomplete response to anti-TNF therapy or were previously treated with a cell-depleting agent were excluded.10

A total of 1220 patients were randomized in a 2:1 manner to receive either TCZ 8 mg/kg infusions or placebo infusions every 4 weeks. All patients continued their conventional DMARD therapy at a stable dose. The primary efficacy endpoint was meeting the ACR20 response criteria after 24 weeks.10

At week 24 the proportion of patients achieving an ACR20 response was significantly greater in the TCZ plus DMARD group than in the control group (60.8% and 24.5%, respectively, P < 0.0001). Secondary endpoints of ACR50 and ACR70 responses were also significantly improved in the TCZ group compared to the control group (37.6% versus 9.0% and 20.5% versus 2.9%, respectively, P < 0.0001). DAS28 remission at week 24 was higher in the TCZ group versus the control group (30% versus 3%, respectively, P < 0.0001).10

The levels of inflammatory markers ESR and CRP decreased significantly in the TCZ group versus the control group by week 24 (P < 0.0001 for each), with normalization of CRP seen within 2 weeks in the TCZ group, with maintenance of low levels throughout the study.10

The TOWARD study group concluded that TCZ combined with any of the DMARDs evaluated was safe and effective in reducing articular and systemic symptoms in patients with an inadequate response to these DMARDs alone.10

The OPTION study (TCZ pivotal trial in MTX inadequate responders), a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial, assessed the therapeutic effects of TCZ in patients with moderate to severe active RA who were taking a stable background dose of MTX.43 Six hundred twenty-three patients were randomly assigned into one of three treatment arms: infusions of TCZ 4 mg/kg, TCZ 8 mg/kg, or TCZ-placebo every 4 weeks, all with concurrent MTX at stable pre-study doses (10–25 mg/week). The primary efficacy endpoint was meeting the ACR20 response criteria 24 weeks after treatment.43

At week 24, the proportion of patients achieving ACR20 was significantly higher in the TCZ 4 mg/kg and TCZ 8 mg/kg groups compared to the placebo group (48%, 59%, and 26%, respectively, P < 0.0001). The ACR50 and ACR70 responses were also significantly higher in both the TCZ 4 mg/kg and TCZ 8 mg/kg group compared to the placebo group (ACR50 31%, 44%, and 11%, respectively, P < 0.001; ACR70 12%, 22%, and 2%, respectively, P < 0.001). DAS28 disease remission was reached by 13%, 27%, and 0.8% of the patients in the TCZ 4 mg/kg, TCZ 8 mg/kg, and placebo groups respectively (P < 0.05).43

As seen in other TCZ trials, the mean CRP concentrations normalized by week 2 of treatment with TCZ 8 mg/kg and remained within the normal range until the end of the study (P < 0.0001 versus baseline). ESR also normalized in the 8 mg/kg group in a similar way to CRP (P < 0.0001 versus baseline).43

The OPTION study group concluded that TCZ was an effective therapeutic approach in patients with moderate to severe active RA.43

Combination therapy – anti-TNF failure

The RADIATE study (research on Actemra [TCZ] determining efficacy after anti-TNF failures) examined the efficacy and safety of TCZ in patients with RA refractory to anti-TNF therapy.44 The study design was similar to the OPTION study but the RA patients in RADIATE had previously had an inadequate response to one or more anti-TNF agents. Four hundred ninety-nine patients were randomly assigned to one of three treatment arms: infusions of TCZ 4 mg/kg, TCZ 8 mg/kg, or placebo infusions every 4 weeks, all with stable doses of MTX (10–25 mg/week). The primary efficacy endpoint was meeting the ACR20 response criteria 24 weeks after treatment. Secondary efficacy and safety endpoints were also assessed.44

At week 24, the proportion of patients achieving an ACR20 was significantly higher in the TCZ 4 mg/kg and TCZ 8 mg/kg groups compared to the placebo group (30.4%, 50.0%, and 10.1%, respectively, P < 0.001). The ACR50 and ACR70 responses were also significantly more common in the TCZ 8 mg/kg group (28.8% and 12.4%, respectively) as compared to the placebo group (3.8% and 1.3%, respectively) (P < 0.001 and P = 0.001 respectively, versus control). Patients responded regardless of the most recently failed anti-TNF or the number of failed treatments. DAS28 remission rates at week 24 were dose related, being achieved by 7.6%, 30.1%, and 1.6% of the TCZ 4 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, and control groups, respectively (P = 0.053 for TCZ 4 mg/kg, P < 0.001 for TCZ 8 mg/kg versus control).44

CRP and ESR levels dropped markedly by week 2 in both the TCZ 4 mg/kg and TCZ 8 mg/kg groups. By week 24 CRP levels had normalized in the TCZ 8 mg/kg group.44

The RADIATE study group concluded that TCZ plus MTX was effective in achieving rapid and sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms of RA in patients with an inadequate response to anti-TNF therapy.44

Radiographic progression with TCZ

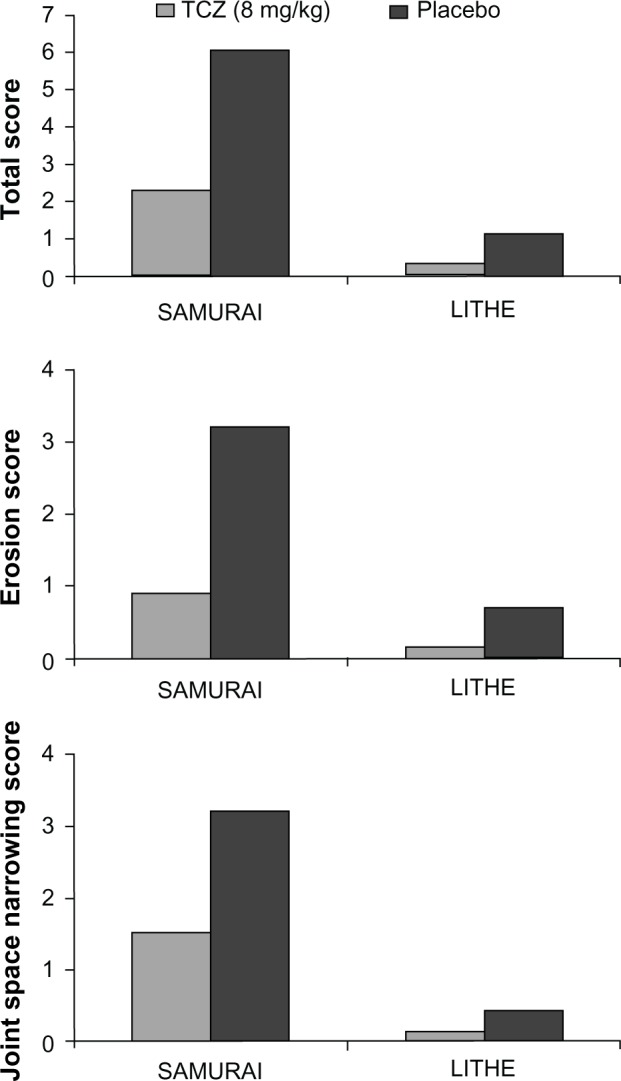

Two Phase III studies looked at the effect of TCZ in preventing structural joint damage in RA patients as the primary endpoint; these were the SAMURAI45 and LITHE46 studies. Both studies had secondary endpoints of clinical efficacy.

Monotherapy – DMARD failure

The SAMURAI study (study of active controlled monotherapy used for RA, an IL-6 inhibitor), an X-ray reader-blind, open-label, randomized controlled trial evaluated the ability of TCZ monotherapy to inhibit progression of structural joint damage in patients with active RA and an inadequate response to at least one DMARD.45

Three hundred six patients with active RA of less than 5 years duration were allocated to receive either infusions of TCZ 8 mg/kg monotherapy or conventional DMARDs (except for leflunomide and anti-TNF therapies), every 4 weeks. The primary endpoint was change in the mean modified Total Shape Score (TSS) at week 52.45

At week 52 the secondary endpoints of ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 responses were achieved in 78%, 64%, and 44%, respectively, in the TCZ group compared to 34%, 13%, and 6%, respectively, in the conventional DMARDs group (P < 0.001, for each comparison), although clinical efficacy was assessed without blinding. DAS28 remission was achieved in 59% receiving TCZ compared to 3% receiving DMARDs (P < 0.001) at week 52.45

The SAMURAI study group concluded that TCZ monotherapy was generally well-tolerated and provided radiographic benefit in patients with RA.45

Combination therapy – DMARD failure

The LITHE study (TCZ safety and the prevention of structural joint damage) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial aiming to assess the efficacy and safety of TCZ in combination with MTX in preventing structural joint damage and improving physical function and disease activity in patients with RA.46 One thousand one hundred ninety-six patients with active moderate to severe RA, who had an incomplete response to MTX and had not previously failed anti-TNF therapy, were randomized into one of three treatment arms: infusions of either TCZ 4 mg/kg, TCZ 8 mg/kg, or a TCZ placebo every 4 weeks, all in combination with MTX 10–25 mg/week. The length of the controlled phase of the study was 2 years, although only results from the first year were published. The main outcomes measured in the trial were the changes from baseline in the Genant-modified Sharp score and the area under the curve in the HAQ-DI after 52 weeks. Secondary endpoints of disease activity using the ACR response criteria were also assessed.46

At week 52 the ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 responses in the TCZ 8 mg/kg plus MTX group (56%, 36%, and 20%, respectively) were significantly higher compared to the control group (P < 0.0001 for each response rate). Additionally, a significantly higher proportion of patients treated with TCZ 8 mg/kg plus MTX achieved a DAS28 remission by 52 weeks compared with the control (47.2% versus 7.9%, respectively, P < 0.0001). The LITHE study group concluded that TCZ plus MTX resulted in greater inhibition of joint damage and greater improvement in physical function than MTX alone.46

Effects of TCZ on X-ray damage

Both the SAMURAI and LITHE studies confirmed that patients treated with TCZ, either as monotherapy or in combination with MTX, had significantly less radiographic progression compared to controls (Figure 3).45,46

Figure 3.

Radiological efficacy.

At the end of week 52 of the SAMURAI study, those patients who were treated with TCZ had significantly less radiographic change in TSS than those patients receiving conventional DMARDs, with 56% and 39% having no radiographic progression (change from baseline TSS ≤ 0.5) in the TCZ and DMARD-treated groups respectively (P < 0.01). TCZ was also superior to DMARDs in preventing both erosions and joint space narrowing (P < 0.001 and P < 0.018, respectively).45

In the LITHE study, at the end of 52 weeks, radiographic progression from baseline was reduced by 70% and 74% in the TCZ 4 mg/kg plus MTX and 8 mg/kg plus MTX groups, respectively, compared to the placebo group (MTX alone) (P < 0.0001 for both comparisons), with mean changes in the Genant-modified Sharp score of 0.34, 0.29, and 1.39 for TCZ 4 mg/kg plus MTX, TCZ 8 mg/kg plus MTX, and placebo respectively (P < 0.0001). At 2 years, patients in the TCZ 8 mg/kg plus MTX group had significantly less radiographic progression compared with the placebo group: 85% versus 67% respectively (P < 0.001).46

Effects of TCZ on function

In addition to clinical efficacy, many studies also explored the effect of TCZ on function using various measurements such as the HAQ-DI, functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT), and the Short Form (36) Health Survey, both mental and physical (SF36-mental and SF36-physical) (summarized in Table 3).10,41–46

Table 3.

Changes in fatigue, pain and disability in key trials

| Trial | Outcome | Placebo/control | Tocilizumab 4 mg/kg | Tocilizumab 8 mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMURAI45 | Modified HAQ | −0.13 (40%) | – | −0.50 (68%, P < 0.001) |

| SATORI42 | Modified HAQ | −0.18 (34%) | – | −0.4 (67%, P < 0.01) |

| OPTION43 | Modified HAQDI | −0.34 | −0.52 (P < 0.005) | −0.55 (P = 0.0082) |

| FACIT – fatigue | 4.0 | 7.3 (P = 0.0063) | 8.6 (P < 0.0001) | |

| SF36 mental | 9.7 | 5.7 (P = 0.0394) | 7.3 (P = 0.0012) | |

| SF36 physical | 5.0 | 9.7 (P < 0.0001) | 9.5 (P < 0.0001) | |

| RADIATE44 | HAQ | −0.05 | −0.31 (P = 0.003) | −0.39 (P < 0.001) |

| TOWARD10 | HAQ-DI | −0.2 | – | −0.5 (P < 0.0001) |

| FACIT | 3.6 | 8.0 (P < 0.0001) | ||

| SF36 mental | 2.3 | 8.9 | ||

| SF36 physical | 4.1 | 5.3 | ||

| AMBITION41 | HAQ-DI | −0.5 | – | −0.7 |

| LITHE46 | HAQ-DI | 52.7% | 59.6% (P < 0.0001) | 62.7% (P < 0.0001) |

Note: P-values are all compared to controls.

Abbreviations: FACIT, functional assessment of chronic illness therapy; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; SF36, Short Form (36) Health Survey; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire.

All seven of the Phase III clinical studies found that TCZ (at either dose where applicable) significantly improved the modified HAQ-DI scores from baseline, compared to controls.10,41–46 The OPTION43 and TOWARD10 studies went on to examine the FACIT and SF36-mental and SF36-physical scores and again found that those patients receiving TCZ had a statistically significant improvement from baseline in comparison to controls.10,43

Tolerability and AEs

TCZ was well-tolerated across all seven Phase III trials, both as monotherapy or in combination with MTX or a DMARD.10,41–46 In general, the overall incidence of AEs was similar in both the TCZ and placebo groups (Table 4).

The majority of AEs were considered to be mild to moderate in severity.10,41–46 The most common AEs in the TCZ treated groups were infection, often nasopharyngitis, followed by gastrointestinal disturbance, stomatitis, rash, and headache.10,41–46 Common infusion reactions (defined as a reaction that occurred within 24 hours of infusion) included hypertension, rash, nausea, and headache.10,41–46 The incidence of serious infusion reactions and anaphylaxis was rare.10,41–46

In all but one of the trials the incidence of serious AEs (SAEs) was similar in the TCZ and placebo groups.10,41–46 In the RADIATE trial44 more SAEs were seen in the MTX monotherapy (placebo) group than in the TCZ treatment groups.44 Serious infections seen in the TCZ treated groups included septic arthritis, staphylococcal cellulitis, and acute pyelonephritis.10,41–46 No cases of tuberculosis were reported, however one case of asymptomatic Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare was reported in a TCZ treated patient in the TOWARD trial.10

Numerous laboratory abnormalities were reported. These tended to center around deranged liver function tests, lipid abnormalities, and neutropenia.10,41–46 Laboratory abnormalities were often more common in the TCZ groups compared to the controls, with many of the excess TCZ events related to an elevation in total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoproteins, and low-density lipoproteins, although the majority found no increase in adverse cardiovascular events.10,41–46 Several trials noted neutropenia in the TCZ treated groups, mostly grade 1–2. Both the AMBITION and RADIATE trials reported grade 3 and 4 neutropenia, respectively.41,44 Those in the latter group were withdrawn from the trial.

Systematic reviews

A number of systematic reviews on the use of TCZ in RA have recently been published, with many including meta-analyses of clinical trial data.17,47 These reviews have concentrated on outcomes including clinical efficacy (ACR20, ACR50, ACR70, and DAS28 remission), effect on radiographic progression, function, quality of life, and safety in over 2000 patients receiving TCZ at varying doses, in comparison to either placebo or an active comparator (often MTX).17

Monotherapy

TCZ monotherapy was found to be more effective at improving the ACR50 and ACR70 scores (OR 21.2 ACR50, OR 18.3 ACR70) than placebo or DMARDs alone (OR 2.76 ACR50, OR 2.3 ACR70).17,47 TCZ 8 mg/kg monotherapy was also found to reduce radiographic disease progression compared to MTX alone.17,47

Combination therapy

All studies have consistently found that combination therapy with TCZ plus a DMARD is more effective than placebo (at either the 4 mg/kg or 8 mg/kg dose) at improving the ACR50 and ACR70 (OR 3.79 ACR50, OR 5.94 ACR70 versus DMARD).17 TCZ at a dose of 8 mg/kg was shown to be more likely to lead to DAS28 remission (OR 10.6 versus DMARD) and a greater improvement in HAQ-DI scores, with no significant increase in SAEs.17 Additionally, combination therapy with TCZ plus MTX was found to reduce radiographic disease progression.17

A systematic review by Campbell et al specifically focused on the risk of AEs with TCZ, and found that there was an increased risk of all AEs in patients treated with combination therapy (TCZ 8 mg/kg plus MTX) (OR 1.53) versus MTX alone.47 This included an increased risk of infection (OR 1.3). However, no significant difference in SAEs was seen even in the higher TCZ dose group. Due to differences in reporting of lipid abnormalities and neutropenia across different trials these AEs could not be evaluated.41 In general, the incidence of SAEs were low (1.5 events/100 patient years), but were increased further when TCZ was given in combination with a nonbiologic DMARD (3.6 events/100 patient years).5

Economic aspects

Within the United Kingdom, access to biological therapies conventionally occurs on the basis of approval by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). NICE currently recommends TCZ plus MTX in patients with disease refractory to both TNF inhibitors and rituximab, or directly after anti-TNF where rituximab is contraindicated. In addition, a recent update suggests that TCZ may be used as monotherapy in DMARD non-responders as an alternative to TNF inhibitors where MTX cannot be co-prescribed.35

All biological therapies are high cost in comparison to DMARDs, and calculating the cost-effectiveness of such agents is complex. A number of cost-effectiveness models involving biologics have been published, but without details of the cost-effectiveness of TCZ.48,49 However, a recent economic model of the use of TCZ as a first-line biological agent in a sequence of biologics found that TCZ was more cost-effective than standard therapy (etanercept followed by adalimumab, rituximab, and abatacept) due to lower cost and increased benefit.50

Conclusion

Although anti-TNF agents provide an excellent clinical response for most patients, up to 40% of patients fail to respond.15 TCZ is the first biologic targeting IL-6 that is licensed for the treatment of RA.16

The clinical trials of TCZ reviewed showed strong evidence that its use, both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX, improve the signs and symptoms of RA within several weeks of commencing treatment.10,14,23,39–46

Additionally TCZ reduced radiological disease progression42,46 and improved physical function both as monotherapy and in combination with MTX.10,14,23,39–46 A 5-year extension study by Nishimoto et al demonstrated that TCZ sustained good long-term efficacy and safety profiles.40

More recently, a study by Dougados et al showed that TCZ monotherapy was as effective as combination therapy (TCZ and MTX) in the treatment of RA.51 TCZ monotherapy may be a valuable treatment strategy in suitable RA patients who are intolerant of MTX.

TCZ was generally well tolerated. Although its use increased the risk of an AE, these were usually mild to moderate in severity and treatment did not increase the risk of SAEs in comparison to controls. Due to moderate increases in serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoproteins, and serum transaminases seen in those treated with TCZ, as well as severe neutropenia in some, regular blood monitoring of full blood count, liver function and lipids is recommended.10,41–46 Whilst these short-term efficacy and safety profiles are encouraging, further long-term safety data are required to better characterize the risk–benefit profile of TCZ.

With advances in pharmacogenomics and the field of stratified medicine expanding, biologics targeting differing pro-inflammatory cytokines may offer new hope for patients who have failed treatment targeting other inflammatory cytokines. Given its clinical efficacy in the treatment of RA, TCZ may be beneficial in the treatment of other autoimmune diseases where IL-6 plays a role in the inflammatory cascade.

Table 2.

Clinical efficacy in Phase III trials

| Trial | Treatment group | Patient numbers | ACR20

|

ACR50

|

ACR70

|

DAS28 remission (< 2.6)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Responses | Significance | Responses | Significance | Responses | Significance | Responses | Significance | |||

| SAMURAI45 | TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly | 158 | 78% | P < 0.001 | 64% | P < 0.001 | 44% | P < 0.001 | 59% | P < 0.001 |

| Conventional DMARD | 148 | 34% | 13% | 6% | 3% | |||||

| SATORI42 | TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + placebo MTX | 61 | 80% | P < 0.001 | 49% | P < 0.001 | 30% | P < 0.001 | 44% | P < 0.001 |

| MTX + placebo TCZ monthly | 64 | 25% | 11% | 6% | 2% | |||||

| OPTION43 | TCZ 4 mg/kg monthly + MTX | 213 | 48% | P < 0.0001 | 31% | P < 0.0001 | 12% | P < 0.0001 | 13% | P = 0.0002 |

| TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + MTX | 205 | 59% | P < 0.0001 | 44% | P < 0.0001 | 22% | P < 0.0001 | 27% | P < 0.0001 | |

| Placebo + MTX | 204 | 26% | 11% | 2% | 1% | |||||

| RADIATE44 | TCZ 4 mg/kg monthly + MTX | 161 | 30% | P < 0.001 | 17% | P < 0.001 | 5% | P = 0.1 | 8% | P = 0.053 |

| TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + MTX | 170 | 50% | P < 0.001 | 29% | P < 0.001 | 12% | P < 0.01 | 30% | P = 0.053 | |

| Placebo monthly + MTX | 158 | 10% | 4% | 1% | 2% | |||||

| TOWARD10 | TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly | 803 | 61% | P < 0.001 | 38% | P < 0.0001 | 21% | P < 0.0001 | 30% | P < 0.0001 |

| Placebo (DMARD) | 415 | 25% | 9% | 3% | 3% | |||||

| AMBITION41 | TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly | 288 | 70% | P < 0.001 | 44% | P = 0.002 | 28% | P < 0.001 | 34% | Not stated |

| Escalating MTX | 284 | 53% | 34% | 15% | 12% | |||||

| LITHE46 | TCZ 4 mg/kg monthly + MTX | 399 | 51% | P < 0.0001 | 25% | Not stated | 1 1% | P < 0.0001 | 30% | P < 0.05 |

| TCZ 8 mg/kg monthly + MTX | 298 | 56% | P < 0.0001 | 32% | P < 0.0001 | 13% | P < 0.0001 | 47% | P < 0.0001 | |

| Placebo monthly + MTX | 393 | 27% | 10% | 2% | 8% | |||||

Notes: P-values are all compared to controls. ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 are defined by a 20%, 50%, or 70% clinical improvement from baseline after treatment, respectively.

Abbreviations: ACR, American College of Rheumatology; DAS28, Disease Activity Score of 28 joints; DMARD, disease modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Israa Al-Shakarchi and Nicola Gullick have received no external grants or personal funding from any industrial sponsor. David L Scott receives grant funding support from Arthritis Research UK and The National Institute for Health Research. In the past 3 years Professor Scott has received no personal funding from any industrial sponsor. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Majithia V, Geraci SA. Rheumatoid arthritis: diagnosis and management. Am J Med. 2007;120(11):936–939. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Shakarchi I. Fragility Fractures in Rheumatoid Arthritis – A systematic review of the literature; Proceedings of the British Society of Rheumatology Conference; April 21–23, 2010; Birmingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, Weisman MH, Emery P. New therapies of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2007;370(9602):1861–1874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimoto N, Yoshiazaki K, Maeda K, et al. Toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and dose-finding study of repetitive treatment with the humanized anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody MRA in rheumatoid arthritis. Phase I/II clinical study. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(7):1426–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarro-Millán I, Singh J, Curtis JR. Systematic review of Tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis: A new biologic agent targeting the Interleukin-6 receptor. Clin Ther. 2012;34(4):788–802. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.02.014. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashizume M, Mihara M. The roles of Interleukin-6 in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/765624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oldfield V, Dhillon S, Plosker GL. Tocilizumab: a review of its use in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2009;69(5):609–632. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423(6937):356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaffo A, Saag KG, Curtis JR. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(24):2451–2465. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Genovese MC, McKay JD, Nasonov EL, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab reduces disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. The Tocilizumab in combination with traditional disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapy study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):2968–2980. doi: 10.1002/art.23940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen NJ, Stein CM. New drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2167–2179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hushaw LL, Sawaqued R, Sweis G, et al. Critical appraisal of tocilizumab in the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:143–152. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s5582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Anti-TNF α therapy of rheumatoid arthritis; what have we learnt? Ann Rev Immunol. 2001;19:163–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maini RN, Taylor PC, Szechinsji J, et al. CHARISMA Study Group Double-blind randomized Controlled clinical trial of the interleukin-6 receptor antagonist, Tocilizumab, in European patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had an incomplete response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(9):2817–2829. doi: 10.1002/art.22033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, et al. All Departments of Rheumatology in Denmark Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide DANIBO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/art.27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishimoto N, Kishimoto T. Humanized antihuman IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008;181:151–160. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73259-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh JA, Beg S, Lopez-Olivo MA. tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis: a cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(1):10–20. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayer J, Choy E. Therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis: the interleukin-6 receptor. Rheumatology. 2010;49(1):15–24. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirano T, Yasukawa K, Harada H, et al. Complementary DNA for a novel human interleukin (BSF-2) that induces B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin. Nature. 1986;324(6092):73–76. doi: 10.1038/324073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6: from basic science to medicine-40 years in immunology. Ann Rev Immunol. 2005;23:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mima T, Nishimoto N. Clinical value of blocking Il-6 receptor. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21(3):224–230. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283295fec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kishimoto T. Interleukin-6 and its receptor in autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 1992;5(Suppl A):123–132. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(92)90027-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choy EH, Isenberg DA, Garrod T, et al. Therapeutic benefit of blocking Interleukin-6 activity with an anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(12):3143–3150. doi: 10.1002/art.10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonseca JE, Santos MJ, Canhão H, Choy E. Interleukin-6 as a key player in systemic inflammation and joint destruction. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8(7):538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano T, Matsuda T, Turner M, et al. Excessive production of interleukin 6/B cell stimulatory factor-2 in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18(11):1797–1801. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okuda Y. Review of tocilizumab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Biologics. 2008;2(1):75–82. doi: 10.2147/btt.s1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose-John S, Scheller J, Elson G, Jones SA. Interleukin-6 biology is coordinated by membrane-bound and soluble receptors: role in inflammation and cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(2):227–236. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirano T. Interleukin 6 and its receptor: ten years later. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16(3–4):249–284. doi: 10.3109/08830189809042997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward LD, Howlett GJ, Discolo G, et al. High affinity interleukin-6 receptor is a hexameric complex consisting of two molecules each of interleukin-6 receptor and gp-130. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(37):23286–23289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lally F, Smith E, Filer A, et al. A novel mechanism of neutrophil recruitment in a coculture model of the rheumatoid synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3460–3409. doi: 10.1002/art.21394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dasgupta B, Corkill M, Kirkham B, Gibson T, Panayi G. Serial estimation of interleukin-6 as a measure of systemic disease in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(1):22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotake S, Sato K, Kim KJ, et al. Interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-6 receptors in the synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis patients are responsible for osteoclast-like cell formation. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(1):88–95. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakahara H, Song J, Sugimoto M, et al. Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody therapy reduces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(6):1521–1529. doi: 10.1002/art.11143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimoto N. Interleukin-6 as a therapeutic target in candidate inflammatory diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(4):483–487. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tocilizumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (rapid review of technology appraisal guidance 198) NICE technology appraisal guidance 247 [webpage on the Internet] London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2012Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA198Accessed Sep 12, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(6):727–735. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Gestel AM, Haagsma CJ, van Riel PL. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis improvement criteria that include simplified joint counts. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(10):1845–1850. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199810)41:10<1845::AID-ART17>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Heijde DM, van’t Hof MA, van Riel PL, et al. Judging disease activity in clinical practice in rheumatoid arthritis: first step in the development of a disease activity score. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49(11):916–920. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.11.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimoto N, Yoshizaki K, Miyasaka N, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with humanized anti–interleukin-6 receptor antibody – a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(6):1761–1769. doi: 10.1002/art.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, Kawai S, Takeuchi T, Azuma J. Long-term safety and efficacy of tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody, in monotherapy, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (the STREAM study): evidence of safety and efficacy in a 5-year extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1580–1584. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones G, Sebba A, Gu J, et al. Comparison of tocilizumab monotherapy versus monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: the AMBITION study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):88–96. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishimoto N, Miyasaka N, Yamamoto K, et al. Study of active controlled tocilizumab monotherapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate (SATORI): significant reduction in disease activity and serum vascular endothelial growth factor by IL-6 receptor inhibition therapy. Mod Rheumatol. 2009;19(1):12–19. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0125-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smolen JS, Beaulieu A, Rubbert-Roth A, et al. OPTION Investigators Effect of interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (OPTION study): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):987–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor biological: results from a 24-week multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1516–1523. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishimoto N, Hashimoto J, Miyasaka N, et al. Study of active controlled monotherapy used for rheumatoid arthritis, an IL-6 inhibitor (SAMURAI): evidence of clinical and radiographic benefit from an x-ray reader-blinded randomized controlled trial of tocilizumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(9):1162–1167. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.068064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kremer JM, Blanco R, Brzosko M, et al. Tocilizumab inhibits structural joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate responses to Methotrexate – results from the double-blind treatment phase of a randomized placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab safety and prevention of structural joint damage at one year. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):609–621. doi: 10.1002/art.30158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell L, Chen C, Bhagat SS, Parker RA, Östör AJ. Risk of adverse events including serious infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tocilizumab: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(3):552–562. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puolakka K, Blåfield H, Kauppi M, et al. Cost-effectiveness modeling of sequential biologic strategies for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in Finland. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:38–43. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoels M, Wong J, Scott DL, et al. Economic aspects of treatment options in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):995–1003. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diamantopoulos A, Benucci M, Capri S, et al. Economic evaluation of tocilizumab combination in the treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. J Med Econ. 2012;15(3):576–585. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.665110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dougados M, Kissel K, Sheeran T, et al. Adding tocilizumab or switching to tocilizumab monotherapy in methotrexate inadequate responders: 24-week symptomatic and structural results of a 2-year randomized controlled strategy trial in rheumatoid arthritis (ACT-RAY) Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(1):43–50. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]