Abstract

Background

Parent-based interventions (PBIs) are an effective strategy to reduce problematic drinking among first-year college students. The current study examined the extent to which student-based characteristics, derived from the Theory of Planned Behavior, moderated three PBI conditions: (1) prior to college matriculation; (2) prior to college matriculation with a booster during the fall semester; and (3) after college matriculation. The moderator variables included injunctive and descriptive peer norms about alcohol use, and attitudes toward alcohol use.

Methods

Using data from a randomized control trial (RCT) delivered to 1900 incoming college students, we examined differential treatment effects within four types of baseline student drinkers: (1) non-drinkers; (2) weekend light drinkers; (3) weekend heavy episodic drinkers; and (4) heavy drinkers. The outcome variable was based on transitions in drinking that occurred between the summer prior to college enrollment and the end of the first fall semester and distinguished between students who transitioned to one of the two risky drinking classes.

Results

The results indicated that injunctive norms (but not descriptive norms or attitudes) moderated the differential effects of the PBI with strongest effects for students whose parents received the booster. Differential effects also depended on baseline drinking class and were most pronounced among weekend light drinkers who were deemed “high-risk” in terms of injunctive peer norms.

Conclusions

Parental influence can remain strong for young adults who are transitioning to college environments, even among students with relatively high peer influence to drink alcohol. Thus, the PBI represents an effective tool to prevent escalation of alcohol use during the first year of college, when risk is highest and patterns of alcohol use are established.

Keywords: College Student Alcohol Use, Theory of Planned Behavior, Differential Treatment Effects, Normative Beliefs, Alcohol Attitudes

Several studies indicate that the transition from high school to college is a particularly vulnerable period that is associated with increased alcohol use and risk for experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences (Maggs and Schulenberg, 2004; White et al., 2006). To prevent such increases, numerous preventive programs have been implemented on college campuses and a substantial literature exists that evaluates the efficacy of these efforts (Larimer and Cronce, 2007). However, less emphasis has been placed on identifying students who may benefit the most from interventions and relatively few studies have examined the extent to which individual characteristics may moderate the effects of such interventions. The current study addresses this need by building on findings presented by Turrisi et al. (2013) to examine potential moderators of a randomized control trial (RCT), which examined how timing and dosage of a parent-based intervention (PBI) related to changes in risky drinking among first-year college students.

Parent-Based Interventions For Risky College Drinking

The PBI approach is based on evidence that parents remain an important source of influence, even as adolescents transition into college settings (Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, 2007; Wood et al., 2004). Designed to enhance parent communication style, the PBI consists of providing an informational handbook to parents of incoming freshmen in order to encourage parent-teen communication about alcohol and reduce parental permissiveness of teen drinking. Turrisi et al. (2013) determined that the timing of the PBI was a critical factor in preventing escalations to risky drinking patterns: strongest effects for reducing the likelihood of transitioning to a heavy drinker were found when the intervention was delivered prior to college matriculation compared to delivery during the fall semester of the first year.

A few studies have examined moderator effects of the PBI. For example, Mallett et al. (2011) found the PBI delivered prior to college matriculation was more effective at reducing drinking among students with parents having higher-risk (e.g., authoritarian or permissive) parenting styles. Other studies indicate that student characteristics, such as gender (Ichiyama et al., 2009) and age of onset (Mallett et al., 2010) moderated the effect of a PBI that was delivered in the summer prior to college entrance. To date, evaluations of differential treatment effects have not included student-based social cognitive variables, which may be modifiable and thereby serve as targets, themselves, of a brief intervention.

Modifiable Characteristics That Influence College Student Alcohol Use

A wide range of factors contributes to high-risk drinking by first-year college students (Borsari et al. 2007). Concerning these risk factors, one theoretical model that has received particular attention in the college drinking literature is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991). The TPB is a social cognition model that presupposes behavior is planned and intentional, arising from decision-making processes that involve consideration of behavioral options and anticipated outcomes (Gerrard et al., 2008). According to the TPB, two primary determinants of behavior intentions are normative beliefs and attitudes, both of which are consistently strong predictors of college students’ alcohol use (Collins and Carey, 2007; Johnston and White, 2003).

Normative beliefs refer to perceptions of significant others and are often described in terms of two types of norms. Descriptive norms refer to perceptions of others’ quantity and frequency of drinking, whereas subjective norms involve perceptions of others’ approval of drinking (Borsari and Carey, 2001). Several studies indicate both descriptive norms and injunctive norms are especially strong predictors of first-year college students’ drinking behaviors (Hartzler and Fromme, 2003; Turrisi et al. 2000). There is also evidence that positive attitudes, such as favorable feelings toward engaging in high-risk drinking, are related to higher levels of alcohol use among college students (Collins and Carey, 2007).

The Current Study

The goal of this study was to examine whether cognitive-based student characteristics moderated the efficacy of three PBI conditions with varied dosage and timing of delivery as described by Turrisi et al. (2013). Three intervention conditions were compared to an intervention-as-usual (IAU) group: PBI delivered prior to college matriculation (PCM), PBI delivered prior to college matriculation, with a booster during the fall semester (PCM+B), and PBI delivered after college matriculation, during the fall semester (ACM). The main outcome variable was derived from the multidimensional classification approach described in Turrisi et al. (2013), which identified four distinct drinker types (classes): non-drinkers (ND), weekend light drinkers (WLD), weekend heavy episodic drinkers (WHED), and heavy drinkers (HD). Specifically, a dichotomous variable was created, based on drinking classification at follow-up (beginning of the second semester of college). Risky Drinkers were defined as students belonging to the WHED or HD classes.

Our analyses were guided by three hypotheses. First, we predicted that student-based characteristics (normative and peer norms, alcohol attitudes) would moderate the effect of the PBI, regardless of baseline drinking. However, previous research has demonstrated that the effects of the PBI are strongest among students who belonged to the ND and HD classes at baseline (Cleveland et al., 2011; Turrisi et al., 2013). These two classes represent the two ends of a continuum of alcohol use, and thereby are likely characterized by limited variability in alcohol-related attitudes and beliefs, relative to the WLD and WHED classes. Thus, our second hypothesis concerned differences within the baseline drinking classes. We hypothesized that interaction effects would be found only among the baseline WLD and WHED classes. For our third hypothesis, we expected “high-risk” students, defined by favorable norms and/or attitudes toward alcohol use to benefit the least from the earlier version of the PBI found to be most effective by Turrisi et al. (2013). That is, we expected to find that among high-norm and high-attitude students, the three PBI conditions would not differ in terms preventing transitions to risky drinking. In contrast, we expected that among the students with average or lower levels of norms and attitudes (i.e., “low-risk”), the strongest effects would be observed for those assigned to the PCM and PCM+B conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Eligible participants were incoming first-year students from a large, public northeastern university, recruited in the summer prior to college matriculation over three cohorts. Of the 2907 participants initially contacted, 1900 consented to participate in the study and completed the web-based baseline assessment, yielding a 65% overall response rate, which is consistent with other studies using web-based approaches (e.g., Larimer et al., 2007). Participant demographics were as follows: 52% female, 87% Caucasian, 5% Asian, 3% African American, and 5% multi-racial or other. Roughly 5% of participants identified as Hispanic, and the mean age at baseline was 17.94 years (SD = 0.32). This sample is identical to that used by Turrisi et al. (2013).

Selection and Recruitment Procedures

Students

Participants were randomly selected from the university registrar’s database of incoming freshmen. Prior to recruitment, participants were automatically randomized using a computerized algorithm to one of the four conditions. Next, invitation letters explaining the study, procedures, and compensation were mailed to all 2907 potential participants. Participants then received an emailed invitation, as well as email and postcard reminders. All recruitment materials included a URL and Personal Identification Number (PIN) for accessing the survey. Participants were informed that they would receive $25 for the baseline survey and $30 for the follow-up survey, conducted at approximately 5 months after baseline. Student assessments occurred at two time points: 1) in the summer two months prior to college matriculation (baseline), and 2) in the winter at the beginning of the second semester of college (follow-up). Participants received $25 for the baseline survey and $30 for the follow-up survey.

Parent Intervention

All parents who attended first-year orientation with their students received a general university handbook that contained information about alcohol, including statistics about college student drinking, the student code of conduct, and university policy for alcohol violations. In this section, there were two paragraphs encouraging parents to talk to their students about alcohol. Parents randomized to one of the intervention conditions were mailed an additional 35-page handbook, described in detail in Turrisi et al. (2001). Topics included an overview of college student drinking, strategies and techniques for communicating effectively with teens, tips on discussing ways to help teens develop assertiveness and resist peer pressure, and in-depth information on how alcohol affects the body. Parents in the PCM and PCM+B conditions received the handbook in the summer prior to college matriculation, after the students had completed the baseline assessment. Parents in the ACM condition received the handbook in the fall of the first year. Parents in the PCM+B condition received three boosters throughout the fall of the first year, which reinforced the content of the handbook. Topics included positive communication strategies, helping students resist peer pressure, and avoiding riding with a drunk driver. The boosters were timed to coincide with specific occasions, such as six weeks into the semester when students typically first visit home and parent’s weekend.

Measures

Normative beliefs about alcohol use (baseline)

Both descriptive and injunctive norms were measured to evaluate normative beliefs about alcohol. Descriptive peer norms were assessed with the Drinking Norms Rating Form (DNRF; Baer et al., 1991). The DNRF asks participants to write how many drinks they think are typically consumed on each day of the week by their close friends. The responses for these seven items were summed for a total number of drinks per week. Injunctive peer norms measured participants’ perceptions of their friends’ approval or disapproval of four specific drinking activities (Baer, 1994): “How would your friends respond if they knew: (a) you drank alcohol every weekend, (b) you drank alcohol daily, (c) you drove a car after drinking, and (d) you drank enough alcohol to pass out?” Response options were measured on a 7-point scale from strong disapproval to strong approval and the four items were averaged to create an overall measure of injunctive norms (α = .74).

Attitudes toward alcohol use (baseline)

Five items assessed attitudes toward drinking. Four items referred to specific drinking activities: (a) drinking alcohol every weekend, (b) drinking alcohol daily, (c) driving a car after drinking, and (d) drinking enough alcohol to pass out. Participants indicated their approval of each behavior, using a 7-point scale (from strong disapproval to strong approval). A single item measured overall attitude toward alcohol, asking participants to indicate which statement best represented them. The response options included: 0 = Drinking is never a good thing to do, 1 = Drinking is all right but a person should not get drunk, 2 = Occasionally getting drunk is okay as long as it doesn’t interfere with academics or other responsibilities, 3 = Occasionally getting drunk is okay even if it does interfere with academics or other responsibilities, 4 = Frequently getting drunk is okay if it is what the individual wants to do. The five items were standardized and then summed to create a single attitude toward alcohol use index (α = .72).

Drinking classes (baseline and follow-up)

Drinking classes were identified in the same manner as Turrisi et al. (2013), using latent transition analysis (LTA). LTA is a statistical procedure in which discrete, mutually exclusive latent classes of individuals are identified from a population based on responses to categorical manifest variables (Collins and Lanza, 2010). Seven dichotomous drinking variables were used as indicators of the LTA model: (1) alcohol use in the past 30 days; (2) drunkenness in the past 30 days; (3) weekday – Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday – drinking (4) Thursday drinking; and (5) weekend – Friday and Saturday – drinking. (6) HED in the past two weeks; and (7) peak blood alcohol concentration (BAC) greater than 0.08 on last drinking occasion. The following alcoholic drink definition was provided: “One drink equals 12 oz. beer (8 oz. of Canadian, malt liquor, or ice beers or 10 oz. of microbrew), 10 oz. wine cooler, 4 oz. wine, 1 cocktail with 1 oz. of 100 proof or 1 ¼ oz. of 80 proof liquor.”

A full description of the LTA model is found in Turrisi et al. (2013). Briefly, four drinking classes were identified at both measurement occasions: (1) ND, unlikely to report any drinking behaviors; (2) WLD, likely to use alcohol in the previous month and to report drinking only on Fridays and Saturdays; (3) WHED, likely to report being drunk in the past month, engage in HED, and have a BAC greater than 0.08 on their recent peak drinking occasion; and (4) HD, likely to endorse all drinking indicators, including weekday drinking and drinking on Thursdays. Posterior probabilities were used to assign students to their most likely latent class at both measurement occasions, from which a dichotomous variable was created to capture risky drinking at the follow-up. Students who transitioned to (or remained in) the WHED or HD drinking classes received a score of 1, whereas those who transitioned to (or remained in) either the ND or WLD drinking classes received a score of 0.

Plan of Analyses

To examine the extent to which student characteristics moderated the effect of the intervention, a series of logistic regression models were first estimated using the entire sample (Hypothesis 1), and then separately within each baseline drinking group (Hypothesis 2). The first step for each model included the main effects of the four-category intervention group variable (reference = IAU group) and the continuous moderator variable. In the second step, the product term representing the interaction of the moderator and the intervention group variable was added. Separate ordinal logistic regression models were specified for each of the three hypothesized student moderators. A regression coefficient associated with the product term that was significant at the 0.05 level was considered to be sufficient evidence of an interaction. To test Hypothesis 3 (“high-risk” students benefit the least), significant interaction terms were probed by examining model-based predicted probabilities of risky drinking at two levels of the moderator variable. High-risk students were those with responses greater than one SD above the mean for each particular moderator variable, and low-risk students were those within one SD of the mean or lower of the moderator variable.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Preliminary analyses compared the means of the moderator variables across the four intervention groups. ANOVA tests revealed no significant differences at baseline between the four intervention groups (all F-values ≤ 1.01, p-values ≥ 0.30). Examination of drinking patterns at baseline and follow-up revealed a high degree of consistency (see Table 1). A majority of baseline ND and WLD remained in a lower-risk drinking pattern at follow up (80% and 53%, respectively), and a majority of WHED and HD remained in higher-risk drinking patterns at follow-up (86% and 95%, respectively).

Table 1.

Distribution of baseline drinker pattern class membership by follow-up risk level.

| Drinking Class at Follow-Up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Risk | High-Risk | ||||

|

| |||||

| Baseline Drinking Class | ND | WLD | WHED | HD | N |

| Non-Drinker | 635 (63%) | 175 (17%) | 141 (14%) | 53 (5%) | 1004 |

| Weekend Light Drinker | 15 (6%) | 111 (47%) | 94 (39%) | 18 (8%) | 238 |

| Weekend Heavy Episodic Drinker | 32 (5%) | 41 (7%) | 188 (32%) | 332 (56%) | 593 |

| Heavy Drinker | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 61 (92%) | 66 |

| N = 1012 | N = 889 | ||||

Note: Values indicate the number (proportion) of students in drinking class at Fall Follow-Up, given membership in Baseline drinking class. Entries along the diagonal in bold and italic font indicate membership in the same drinking class at both times (i.e., stability). ND = Non-Drinker; WLD = Weekend Light Drinker; WHED = Weekend Heavy Episodic Drinker; HD = Heavy Drinker.

Testing Moderation Effects across the Full Sample

Results of the logistic regression models are presented in Table 2, first for the entire sample and then separately by baseline drinking class. For each group, the table displays the maximum likelihood estimates for the four-category intervention group variable, the specific student characteristic moderator, and the interaction terms as predictors of the model. Models predicting transitions for the HD group failed to converge, most likely due to the fact that only 3 out of 66 students in this baseline drinking group transitioned to low risk drinking (i.e., ND or WLD) at the fall follow-up, and are not displayed.

Table 2.

Results of ordered logistic regression models, separately by baseline drinking pattern group.

| Baseline Drinking Pattern Group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | ND | WLD | WHED | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Parameter | Injuct | Desc | Att Alc | Injuct | Desc | Att Alc | Injuct | Desc | Att Alc | Injuct | Desc | Att Alc |

| Intercept | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.43*** | 1.38*** | 1.17*** | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 1.75*** | 1.86*** | 1.57*** |

| PCM | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.21 | −0.13 | −0.18 | −0.16 | −0.19 | −0.32 | −0.17 |

| PCM+B | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.20 | 0.10 | −0.13 | −0.03 | 0.17 | −0.01 | 0.13 |

| ACM | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.14 | −0.47 | −0.50 | −0.34 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.62 |

| Moderator | 0.22*** | 0.12*** | 0.39*** | 0.10* | 0.04 | 0.26*** | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.28** | 0.01 | 0.26* |

| MOD × PCM | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.23+ | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| MOD × PCM+B | −0.08* | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.30* | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.23+ | 0.03 | −0.08 |

| MOD × ACM | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.18 | −0.11 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.10 |

Note: Values in table refer to maximum likelihood estimates with 1 df; Injunct = Injunctive peer norms; Desc = Descriptive peer norms; Att Alc = Attitudes toward alcohol use; MOD = Moderator variable; ND = Non-Drinker; WLD = Weekend Light Drinker; WHED = Weekend Heavy Episodic Drinker.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

The first set of columns in Table 2 present results of models using the entire sample. In these analyses, all three student characteristics were significantly and positively related to increased odds of risky drinking at the fall follow-up. However, these main effects were qualified by one significant interaction effect: injunctive peer norms significantly moderated the effect of the intervention for students assigned to the PCM+B condition (β = − 0.08; p < 0.05). None of the interaction effects involving descriptive peer norms or attitudes toward alcohol use were significant among the entire sample.

Testing Moderation Effects within Baseline Drinking Classes

Logistic regression models conducted separately within each drinking class (ND, WLD, and WHED) are also presented in Table 2. Significant interaction effects were found for students who were in the baseline WLD drinking class. Within this class, a significant interaction was found between injunctive peer norms and the PCM+B condition (β = − 0.30; p < 0.05). The interaction between injunctive peer norms and the PCM condition approached significance in this class (β = − 0.26; p = 0.05). Similarly, for students in the baseline WHED group, the interaction between injunctive norms and the PCM+B condition approached significance (β = − 0.23; p = 0.06). Again, none of the interaction effects involving descriptive peer norms or attitudes toward alcohol use were significant.

Moderation of Intervention Effects Across Low- And High-Risk Students

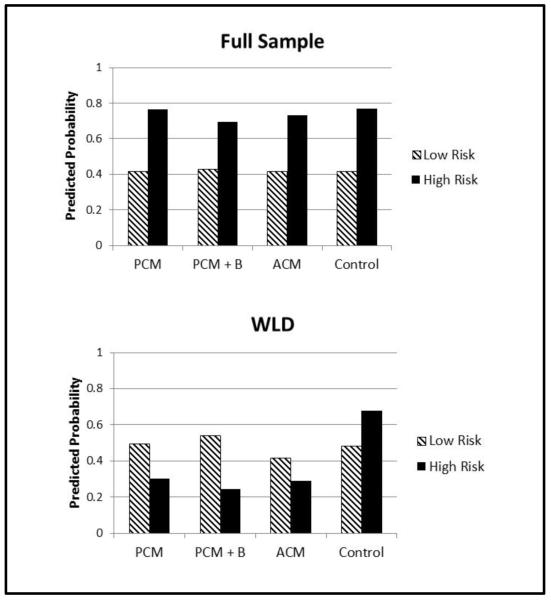

Figure 1 displays the predicted probabilities of being a risky drinker at follow-up, separately for low- and high-risk students across the four intervention conditions. The results for the full sample (top panel) indicate that regardless of intervention condition, high-risk students (defined in terms of normative peer beliefs) were more likely to be a risky drinker at the follow up relative to students with less favorable norms. One-way ANOVA tests revealed that significant differences among the interventions groups were found only among the high-risk students (F = 22.00, df = 3; p < 0.001). Post-hoc Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons tests further indicated that among the high-risk students, those belonging to the PCM+B condition were least likely to be a risky drinker at follow-up (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of risky drinking for students with low and high levels of injunctive peer norms across the four intervention conditions among the full sample (top panel) and Weekend Light Drinkers (bottom panel).

The bottom panel of Figure 1 displays the predicted probabilities of risky drinking for the baseline WLD drinking class. Contrary to the results among the full sample, high-risk students who belonged to the baseline WLD drinking class and who received one of the three intervention conditions were least likely to be a risky drinker at the follow up. For these high-risk students, the omnibus ANOVA test was significant (F = 173.36, df = 3; p < 0.001) and post-hoc comparisons revealed that those belonging to any of the three intervention conditions were less likely to a risky drinker, compared to the IAU condition (all ps < 0.05). No other significant differences among the three PBI conditions were found. ANOVA also indicated significant differences among the intervention groups among the low-risk WLDs (F = 27.89, df = 3; p < 0.001). Within this group, post-hoc comparisons of means revealed that students assigned to the ACM condition were least likely to be a risky drinker at follow-up (p < 0.05) and students in the PCM or PCM+B conditions fared no better than students in the IAU condition.

DISCUSSION

The current study used the TPB (Ajzen, 1991) to examine three potential moderators of a PBI designed to reduce risky drinking among first-year college students. We found that injunctive peer norms for alcohol use significantly moderated the effects of the PBI on transitions in drinking during the first semester of college enrollment. Thus, our first hypothesis, which stated that the decision-making variables would moderate the effect of the PBI, across the full sample, was partially supported. This moderation was found in analyses conducted using the full sample as well as within the baseline WLD drinking class, with marginal results for the baseline WHED drinking class. These results lend partial support for our second hypothesis, which stated that differential treatment effects would be found only among less “extreme” baseline drinking classes (i.e., WLD and WHED groups). Our third hypothesis stated that students who hold favorable (i.e., high-risk) beliefs and attitudes about alcohol use would be equally unresponsive to the PBI, regardless of the timing of delivery or the presence of booster materials. This hypothesis was not supported.

The results of the current study confirm that parental influence on adolescents’ drinking behavior remains strong into early adulthood (Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez, 2007; Wood et al. 2004), even among teens who perceive strong peer influence to drink alcohol. Contrary to our expectations, however, these “high-risk” students benefitted the most from the PBI, particularly when the intervention was delivered prior to college enrollment and was accompanied by a booster during their first semester. These results expand upon the findings reported by Turrisi et al. (2013), who found that boosters did not provide any additional benefit to the PCM condition. The present study suggests that rather than having direct effects on risky drinking, boosters may offset the influence of peer injunctive norms, particularly for these high-risk youth. Our results demonstrate that parents who maintain effective communication with their teen and, through this communication, reinforce expectations regarding alcohol use can provide protection during this vulnerable transition, when most young people increase their drinking behaviors (Cleveland et al., 2011; Sher and Rutledge, 2007).

Examining differential moderation effects of the PBI within each baseline drinking class also revealed surprising results. Previous results indicated that the PBI was most effective in causing heavy drinkers to transition out of this pattern of drinking (Turrisi et al., 2013). However, we found that first-year students who drank moderately and only on weekends, yet who also perceived strong influence from their friends to drink alcohol, benefitted the most from the PBI, regardless of timing or dosage. In fact, such students were even less likely than any of the low-risk students (who perceive relatively less influence from their friends to drink alcohol) to transition to a risky drinking status at follow-up. Due to the unexpected nature of these findings, which have no precedence in previous evaluations of the PBI, we offer the following speculation in their interpretation.

Among other interventions that have shown success in reducing risky drinking among college students, feedback-based interventions are perhaps the most widely implemented (Larimer and Cronce, 2007). These interventions provide feedback to the student regarding normative alcohol use among their peers as well as the students’ own alcohol use and beliefs and rely on presenting discrepant information as a means of exploring and resolving ambivalence, which increases motivation for change (Walters and Neighbors, 2005). This discrepancy is closely related to the psychological experience of cognitive dissonance, which arises when individuals simultaneously hold inconsistent cognitions (McNally et al., 2005). The results of the present study indicate the strongest effect of the PBI was among a group of students who despite holding risky beliefs about their peers’ approval of alcohol use, reported only moderate levels of drinking themselves (WLD). Parental communication of norms and expectations regarding their child’s alcohol use may have increased this dissonance, thereby leading to enhanced effects of the PBI.

This process may also help elucidate the unexpected finding that the effectiveness of the PBI did not vary across different levels of descriptive peer norms or attitudes toward alcohol use. Borsari and Carey (2003) report that self-other-discrepancies (SODs) are greater for injunctive norms, relative to descriptive norms, perhaps due to the greater inference involved in judging others’ approval compared to overt behaviors. Other studies have evaluated mechanisms through which feedback-based interventions operate and found that changes in drinking were not linked to changes in alcohol-related expectancies (Borsari and Carey, 2000). The current findings contribute to this literature by suggesting that PBIs may also be most effective when opportunities for creating resistance to social norms are present. In these situations, the PBI might encourage the student to resist normative influences and instead act on their own principles (Blanton et al., 2008).

It may also be that these factors, relative to injunctive peer norms, are more dynamic during this transition, as individuals form new friendships in college and are exposed to new and more favorable, drinking environments. It is likely that selection and socialization influences operate simultaneously in a bi-directional or reciprocal process such that some students self-select into heavy-drinking peer groups, which in turn lead the students to develop more favorable attitudes toward drinking. However, previous research that has examined these relationships has focused primarily relations between heavy drinking and descriptive norms (e.g., Abar and Maggs, 2010; Corbin et al., 2011; Read et al., 2005; Stappenbek et al., 2010) or failed to distinguish between descriptive and injunctive norms (Park et al., 2009; Parra et al., 2007). The present results point to the need for further investigations that examine reciprocal influences among alcohol use and all three factors (injunctive norms, descriptive norms, and attitudes toward alcohol use).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several steps were taken to reduce study limitations. These included the use of an RCT design and a large sample with equal proportion of both genders. An additional strength was the use of theoretically-derived moderator variables, which were assessed prior to the intervention, and a multidimensional approach to alcohol use. However, minor limitations remain, including the fact that the sample included students from only one university and may not generalize to other, more heterogeneous college populations. We also focused on transitions in drinking that occurred during the fall semester of the first year of college. Future studies that investigate how decision-making variables impact later transitions in drinking behaviors (e.g., upon moving off campus or turning 21) are necessary to gain full understanding of these moderating processes.

Because our research was motivated by a desire to identify student characteristics that are identifiable upon delivery of the intervention (and thus amenable to change at that time), we chose to focus on baseline student characteristics as moderators. Future research that includes later assessments of potential moderators may help clarify this study’s unexpected findings. Such investigations must account for evidence that the effects of the PBI on student drinking outcomes are mediated through all three of the decision-making variables specified as moderators in the current study (Turrisi et al., 2009; 2010). Thus, future studies that examine mediated moderation or moderated mediation effects (Morgan-Lopez and MacKinnon, 2006; Muller et al. 2005) may be required to disentangle the mechanisms through which selection and socialization processes may result in differential treatment effects among low- and high-risk students. Finally, our study did not include other possible moderators of these relations, such as gender or ethnicity. Additional research is clearly needed on these, and other possible moderators, before firm recommendations can be made about the targeted use of PBIs for preventing college students’ high-risk drinking.

Summary and Conclusions

Previous research with the same sample has found that the PCM condition was most beneficial for incoming students with established patterns of heavy drinking and less effective for students who reported drinking only on weekends (Turrisi et al., 2013). The current results add further nuance to these main effects and suggest that the PBI is an effective tool to prevent escalation of drinking among weekend drinkers who also perceive high levels of normative approval from their friends to drink alcohol. We found that such students displayed the least stability in their drinking patterns during the transition to college, a time when many young people increase alcohol consumption (Hersh and Hussong, 2006; Sher and Rutledge, 2007; White et al., 2006). Thus, prevention of escalation among this at-risk group is noteworthy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) R01 AA R01AA015737 (to Turrisi). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Cleveland, The Prevention Research Center, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Brittney Hultgren,

Lindsey Varvil-Weld,

Kimberly A. Mallett, The Prevention Research Center, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Rob Turrisi,

Caitlin C. Abar, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912.

REFERENCES

- Abar CC, Maggs JL. Social influence and selection processes as predictors of normative perceptions and alcohol use across the transition to college. J Coll Stud Dev. 2010;51:496–508. doi: 10.1353/csd.2010.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer M. Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. J Stud Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. (1991) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psych of Addict Behav. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H, Köblitz A, McCaul KD. Misperceptions about norm misperceptions: Descriptive, injunctive, and affective ‘Social Norming’ efforts to change health behaviors. Soc Person Psych Compass. 2008;2/3:1379–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2062–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MJ, Lanza ST, Ray AE, Turrisi R, Mallett KA. Transitions in first-year college student drinking behaviors: Does pre-college drinking moderate the effects of parent- and peer-based intervention components? Psychol Addict Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0026130. Online First Publication, November 7, 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0026130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Carey KB. The theory of planned behavior as a model of heavy episodic drinking among college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:498–507. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Wiley; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Iwamoto D, Fromme K. Broad social motives, alcohol use, and related problems: Mechanisms of risk from high school through college. Addict Behav. 2011;36:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Guillford Press. New York: 1999. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Fromme K. Heavy episodic drinking and college entrance. J Drug Educ. 2003;33:259–274. doi: 10.2190/2L2X-F8E1-32T9-UDMU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh MA, Hussong AM. High school drinker typologies predict alcohol involvement and psychosocial adjustment during acclimation to college. J Youth Adolescence. 2006;35:738–751. [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyama MA, Fairlie AM, Wood M, Turrisi R, Francis D, Ray AE, Stanger L. A randomized trial of a parent-based intervention on drinking behavior among incoming college freshmen. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;Suppl 16:67–76. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston KL, White KM. Binge-drinking: A test of the role of group norms in the theory of planned behavior. Psychology and Health. 2003;18:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–50. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999-2006. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, et al. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Trajectories of alcohol use during the transition to adulthood. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Ray AE, Turrisi R, Belden C, Bachrach RL, Larimer ME. Age of drinking onset as a moderator of the efficacy of parent-based, brief motivational, and combined intervention approaches to reduce drinking and consequences among college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1153–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Somers JM, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention with high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2 year follow-up assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addict Behav. 1979;4:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Kahler CW. Motivational interventions for heavy drinking college students: examining the role of discrepancy-related psychological processes. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:79–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Lopez AA, MacKinnon DP. Demonstration and evaluation of a method for assessing mediated moderation. Behav Res Methods. 2006;38:77–87. doi: 10.3758/bf03192752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U. S. colleges. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 2002. (NIH Publication No. 02-5010) [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Morgan-Lopez AA. College drinking behaviors: mediational links between parenting styles, parental bonds, depression, and alcohol problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:297–306. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Wood PK, Krull JL. Dual mechanisms underlying accentuation of risky drinking via fraternity/sorority affiliation: the role of personality, peer norms, and alcohol availability. J of Abnorm Psych. 2009;118:241–245. doi: 10.1037/a0015126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra GR, Krull JL, Sher KJ, Jackson KM. Frequency of heavy drinking and perceived peer alcohol involvement: Comparison of influence and selection mechanisms from a developmental perspective. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2211–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Capone C. A prospective investigation of relations between social influences and alcohol involvement during the transition to college. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2005;66:23–34. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addict Behav. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stappenbeck CA, Quinn PD, Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Perceived norms for drinking in the transition from high school to college and beyond. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:895–903. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Abar C, Mallett KA. An examination of the meditational effects of cognitive and attitudinal factors of a parent intervention to reduce college drinking. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2010;40:2500–2526. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunham H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, Kilmer JR, Ray AE, Mastroleo NR, Geisner IM, Grossbard J, Tollison S, Lostutter TW, Montoya H. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mallett KA, Cleveland MJ, Varvil-Weld L, Abar C, Scaglione NM, Hultgren B. Evaluation of timing and dosage of a parent-based intervention to minimize college students’ alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:30–40. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Padilla KK, Wiersma KA. College student drinking: An examination of theoretical models of drinking tendencies in freshmen and upperclassmen. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:598–602. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addict Behav. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:810–822. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Mitchell RE, Brand NH. Do parents still matter? Parent and peer influences on alcohol involvement among recent high school graduates. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]