Abstract

Background

The relationships between physicians and hospitals are viewed as central to the proposition of delivering high-quality health care at a sustainable cost. Over the last two decades, major changes in the scope, breadth, and complexities of these relationships have emerged. Despite understanding the need for physician-hospital alignment, identification and understanding the incentives and drivers of alignment prove challenging.

Questions/purposes

Our review identifies the primary drivers of physician alignment with hospitals from both the physician and hospital perspectives. Further, we assess the drivers more specific to motivating orthopaedic surgeons to align with hospitals.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive literature review from 1992 to March 2012 to evaluate published studies and opinions on the issues surrounding physician-hospital alignment. Literature searches were performed in both MEDLINE® and Health Business™ Elite.

Results

Available literature identifies economic and regulatory shifts in health care and cultural factors as primary drivers of physician-hospital alignment. Specific to orthopaedics, factors driving alignment include the profitability of orthopaedic service lines, the expense of implants, and issues surrounding ambulatory surgery centers and other ancillary services.

Conclusions

Evolving healthcare delivery and payment reforms promote increased collaboration between physicians and hospitals. While economic incentives and increasing regulatory demands provide the strongest drivers, cultural changes including physician leadership and changing expectations of work-life balance must be considered when pursuing successful alignment models. Physicians and hospitals view each other as critical to achieving lower-cost, higher-quality health care.

Introduction

Relationships between physicians and hospitals have evolved over the decades, reflecting changes in healthcare economics and policy. Historically, hospitals and physicians have had a symbiotic relationship. Both had aligned incentives to foster a relationship that supported hospital admissions. However, with a shift of care to the ambulatory setting, competition emerged between physicians and hospitals. With more outpatient care, physicians (notably surgeons) were less dependent on inpatient services offered by the hospital. Further, physician practices incorporating ancillary services competed with hospital-based services. For the hospitals, loss of reimbursement for these services, particularly for operative and ancillary services, encouraged competition in the outpatient market [20, 28, 39]. One author described the era as “…head-on competitive warfare that developed over a variety of outpatient and inpatient services” [28].

Declining physician reimbursement for professional services combined with the burden of increasing overhead has made many physicians reconsider their competitive role with hospitals. Hospitals, many of whom face similar economic challenges, recognize working with physicians can allow them to achieve their goals of improving quality, reducing costs, and complying with federally mandated quality reporting and improvement programs.

Over the past decade and looking forward, changes in healthcare delivery models and reimbursement favor collaboration between physicians and hospitals. Integrated healthcare delivery systems require all stakeholders across the continuum of patient care to consider the global costs of delivering that care. Currently, accountable care organizations (ACOs) are being established, in which hospitals and physicians together provide medical care to a population of patients, accepting responsibility for the health outcomes and cost of providing care. Bundled payments provide a lump sum reimbursement for a discrete service (eg, total joint arthroplasty). To remain fiscally solvent, hospitals and physicians must collaborate to provide efficient, high-quality care. Additionally, emphasis on quality as a criterion for reimbursement demands that physicians and hospitals work together to meet quality-reporting requirements and minimize complications and readmissions.

While hospitals seek to align with physicians in many specialties, orthopaedic surgeons offer a particular attraction for the hospital or health system, with future growth seen in this service line [4]. Notably, the high cost and reimbursements for orthopaedic services and the potential for savings in orthopaedic device purchasing are attractive areas where hospital margins can be improved [2]. Multiple models of alignment exist, including medical directorship, gainsharing, service line comanagement, joint ventures, and bundled payments. Most are complex arrangements with important legal implications [34, 44].

The literature on physician-hospital alignment produces sources that identify employment under the umbrella of alignment [1, 18, 22, 29, 32, 36, 41, 49]. For this paper, we consider employment as a distinct alternative to alignment. Alignment might include the exchange of compensation for services rendered by a physician, but this compensation does not constitute a majority of the physician’s income. Further, employment of a physician does not guarantee alignment in the broader sense. A recent study investigated quality and cost issues associated with hospital employment of physicians. The authors noted: “While greater physician alignment with hospitals may improve quality through better clinical integration and care coordination, hospital employment of physicians does not guarantee clinical integration” [41]. Despite this, in an environment of increasing hospital and health system employment of physicians, the alignment literature includes factors motivating employment that add important breadth to the discussion and are included.

In this review, we (1) identify the key factors driving physicians to align with hospitals, including financial factors, healthcare reform with transition to value-based care, and cultural factors; (2) review the factors promoting alignment from the hospital perspective; and (3) assess the drivers more specific to motivating orthopaedic surgeons to align with hospitals.

Search Strategy and Criteria

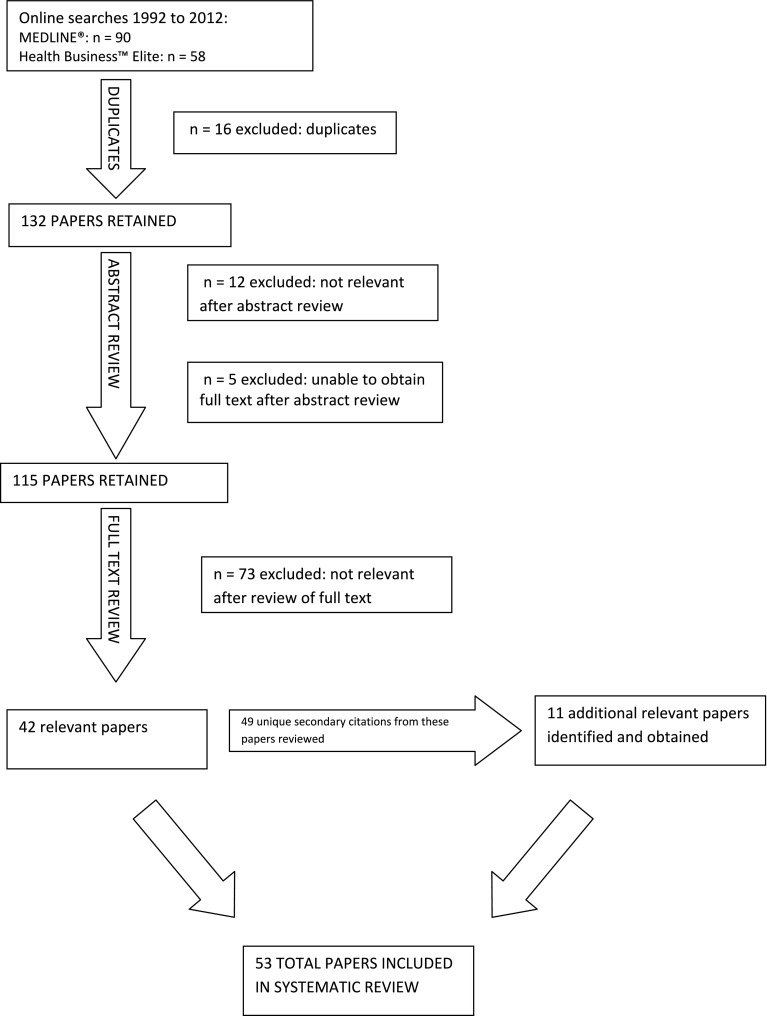

We performed a literature review in MEDLINE® since this allowed efficient and reasonably exhaustive retrieval of records indexed with the National Library of Medicine’s controlled vocabulary, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH®). Search criteria were identified with the assistance of a professional medical librarian (PB) to use MeSH® terms for broader capture. Multiple search strategies (Appendix 1) were employed to include terms potentially reflected in the nonmedical literature. The MEDLINE®-related citation function was used, which produced an additional five articles. Selections were limited to English language, dates from January 1992 to March 2012, with full texts available either electronically or from a library source. The original MEDLINE® searches produced 90 articles (Fig. 1). Review of abstracts eliminated four articles; five articles could not be obtained. One author (AEP) reviewed the full text of all remaining 81 articles, eliminating 48 as unrelated to the central topic and leaving 33 references. Citations from the relevant articles were reviewed, with potentially 49 additional unique, relevant articles; 11 articles or books could not be obtained. Review of the abstract and/or complete text of these secondary references generated 11 papers relevant to the topic that were included. Additionally, we performed a search in Health Business™ Elite, a database focused on healthcare administration and nonclinical issues, using a basic search strategy of “alignment AND [physician OR hospital]” from 1992 to 2012. This search produced 42 unique articles. Review of abstracts eliminated eight, and one author (AEP) reviewed the remaining full papers and identified nine additional relevant references. From all searches, 53 unique articles relevant to the topic were included.

Fig. 1.

A flowchart illustrates the literature review strategy to identify the papers included in the systematic review.

Primary Drivers of Physician Alignment

Financial Factors

The major drivers of alignment highlighted in the literature are economic: the combination of declining income and increasing overhead. Physicians face financial pressures from declining reimbursement [3, 7, 14, 15, 18, 21, 23, 29, 31, 34, 37, 38, 44, 52]. In the environment of declining income, practice expenses and overhead costs are rising. Most notably, increasing regulatory requirements, including compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, physician quality reporting, and adoption of electronic health records, place an economic burden on physician practices by increasing administrative costs. Further, accessing capital for these practice upgrades or for expansion of a service line was identified as another reason physicians sought alignment with a hospital or health system [3, 8, 9, 15, 19, 21, 29, 31, 35, 37, 38, 41, 44, 49, 50]. Several authors have specifically noted concerns about managed care influencing collaboration between physicians and hospitals [3, 5, 7, 10, 36].

The literature on physician-hospital alignment before 2000 is notably sparse [24, 31, 55]. These earlier papers address the importance of collaboration, in a general sense. Of note, economic drivers of decreased reimbursement are not mentioned specifically in these publications. This supports a conclusion that financial considerations of alignment have emerged coincident with the era of increasing costs of providing care and declining reimbursement. Zuckerman et al. [55] wrote the most comprehensive early paper we identified and included reference to a 1995 report (could not be obtained) identifying eight factors that promoted physicians to seek alignment with hospitals in the early 1990s. While mention is made of physician interest in achieving a buffer against health reform/managed care and interest in hospital systems/support services, the authors concluded the factors “suggest physicians intend to cooperate with and contribute to the organization in some capacities, while retaining a degree of control in others” [55].

Marcus et al. [37], among other authors [27, 53], specifically addressed the particular challenges facing academic institutions that promote interest in physician-hospital alignment. Addressing the academic experience, the authors noted regulatory changes in the past 25 years, notably the Stark laws, have also encouraged alignment. Historically, hospitals could supplement income for academic physicians through ancillary services. Medicare and Medicaid restrictions on self-referrals eliminated this opportunity, starting with the Stark I law in 1989. However, the Stark II law implemented in 1993 and 1994 affected services commonly provided in orthopaedic offices. Loss of income from radiology and durable medical equipment, for example [6, 48], challenged physicians and practices to remain profitable while still dedicating professional time and practice resources to the academic mission of the hospital [27, 37].

Facing the added burden of providing care to the indigent/uninsured and the added costs associated with funding the core missions of research and teaching in an academic setting, at least one orthopaedic program realized without competitive compensation they would be unable to attract and retain high-quality surgeons in the future [37]. In response, this institution developed a balanced employment model, which facilitated a migration to an integrated delivery system.

Healthcare Reform and Value-based Care

The shift toward value-based care with shared responsibility for outcomes and cost further promotes alignment between physicians and hospitals. Some articles cite the ACO model specifically; others review more generally transition to more integrated/coordinated care [14, 34, 37, 38, 41, 50, 52]. Similarly, alignment of stakeholders best provides the integration necessary for clinical coordination of high-quality, high-value care [1, 3, 9, 14, 36]. By promoting integration and cost-conscious care, alignment models support the foundation of value-based medicine. Far ahead of the curve in 2000, an article in the Joint Commission’s Journal of Quality Improvement noted “the need to develop collaborative physician-organization relationships within which performance measurement across the continuum of care occurs” [24]. Bundled payment models have also been noted to drive alignment of physicians with hospitals [37, 38]. Despite the theory of alignment improving quality, no literature was identified confirming improvements in quality for these shared-risk models.

Cultural Factors

Cultural considerations are less well defined than financial considerations but also influence physician decisions to align with a hospital. The financial drivers of alignment noted above have stressed changes in physician practices, challenging physicians to maintain control over their practice environment. Burns and Muller [3], as well as other authors [38, 55], note physician control of practices has been eroding and effective alignment models such as joint ventures or service line comanagement offer an opportunity for physicians to participate in decision making and hospital management.

Employment does not specifically imply alignment, but several studies cited physician groups facing difficulties recruiting younger physicians who often preferred employment in large organizations or hospitals [15, 18, 41]. Work-life balance appears be a higher priority than for previous physician generations and may influence increased interest in employment [3, 9, 21, 29, 32, 34, 35, 39, 49]. Furthermore, increasing educational debt may make young physicians less able to start or buy into a practice [39]. Terry [49] quotes a senior vice president of the American Hospital Association on the topic: “Young physicians are going to work for hospitals partly for lifestyle reasons. They don’t want to start practices or buy into partnerships, and they prize the stability of hospital income because of their high medical school debt.”

In traditional private practice models, the hospital administration literature examining professional service agreements and income guarantees as models for alignment notes, even for established physicians, there is a perception that “[t]he climate has changed. Physicians today are more willing to trade off independence for lifestyle, and an entrepreneurial mode for financial security. Many are seeking a work environment offering protection from rampant malpractice costs and continued decreases in reimbursement” [34]. In earlier literature, these factors were also noted. Zuckerman et al. [55] cited a 1994 study that included among reasons physicians seek alignment: “[to] achieve a degree of security. While typically cast in terms of economic security and income stability, lifestyle issues and benefits also are of importance.” Other authors recognize, beyond the economics of practice management, some physicians choose alignment models that allow them more time for practicing medicine by minimizing the demands of running a business [8].

Hospital/Healthcare System Perspective on Factors Driving Alignment

Understanding factors driving hospitals to seek alignment contributes to understanding the bigger picture. Similar concerns over declining reimbursement and uncertainty surrounding new delivery models motivate alignment for hospitals and healthcare systems [3, 11, 23, 25, 33, 34, 36, 37, 49], Lovrien and Peterson [33] noted, “Effective partnerships between hospitals and physicians are required to optimize the delivery system and ensure effective coordination of care while maintaining appropriate financial returns for the hospital.” Further, the need to provide emergency room coverage has driven hospitals to engage orthopaedic surgeons and other physicians [1, 3, 43].

Just as concerns about healthcare reform drive physician interest in alignment, hospitals are increasingly seeking to improve their ability to participate in new value-based payment models such as bundled payments or ACOs [3, 4, 14, 15, 17, 22, 34, 49, 52]. The chief executive officer of St John’s Hospital in Springfield, IL, USA, noted how hospitals see alignment through service lines as a way to achieve the transition to value-based medicine, quoting in an article: “From a market standpoint, there is a clear movement from volume to value, and the service line orientation is a great opportunity to create value” [4]. Joanne Goodroe [47], a senior vice president for VHA®, a national healthcare network focusing on supply chain management, is quoted on quality and alignment: “What you see now is more specificity in how quality is being measured. And you also see more recognition that physicians are the drivers of quality and the cost side and for the future, that’s going to require hospital-physician alignment.”

Catherine Jacobs [26], the former chair of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, noted in 2009: “Ultimately, the success of payment reform depends on true alignment of economic incentives…[Q]uality improvement and incentive alignment are a strategic imperative for our organizations.”

Increasing emphasis on outcome-based reimbursement motivates the need to involve physicians actively in quality improvement activities [3, 32]. More recent articles address the alignment of purpose, as well financial issues [22, 33, 42], some even specifically contrasting current trends with the poor results from the 1990s [14, 21, 38, 40, 42]. Nick Sears [45], a cardiovascular surgeon/physician executive, noted in 2008, “Given the many efforts made in the 1990s to align hospitals and physicians, today’s financial pressures give both parties reason to work out some of the problems identified the first time around and try again.”

Drivers Motivating Orthopaedic Surgeons to Align with Hospitals

As a potentially lucrative and growing service line, orthopaedic practices have been targeted by hospitals for alignment and acquisition [1, 49]. For many hospitals, maintaining the profitable service lines, which include orthopaedics, has influenced the need for collaboration [1, 4, 7]. However, rising costs associated particularly with joint arthroplasty implants actually started to decrease the profitability of orthopaedic service lines, creating another motivation for physician-hospital collaboration [2]. This erosion of profitability associated with orthopaedic service lines has been multifactorial. Unfavorable changes in hospital reimbursement for orthopaedic procedures, widespread adoption of expensive new premium, higher-cost technologies, and the transition of many profitable procedures to ambulatory surgery centers have all contributed to declining profitability of inpatient orthopaedic service lines [23].

Burns et al. [2] noted the financial benefit of alignment regarding implant/device contracting. This could benefit orthopaedic surgeons and hospitals alike as bundled payment becomes more common. From the hospital view, the costs of implants can be a driving force for aligning with orthopaedic surgeons [2, 3, 12, 13, 16, 30, 46]. DiConsiglio [12] offered the example of a high-volume surgeon who considered himself a top performer but, due to choice of expensive surgical supplies, the hospital lost money on most of his cases. In the context of surgeon preference cards, acknowledging surgeons have preferences driven by their desire to deliver high-quality care to their patients, one article from the hospital administration literature also noted, “Physicians’ personal preferences significantly drive up health care costs” [17].

Surgeon-owned ambulatory surgery centers and independent imaging centers have historically been in direct competition with hospital imaging and outpatient surgery centers [1]. From the hospital perspective, regaining this profit center makes alignment with the physician-owners attractive [8, 25, 51, 54]. One earlier study noted: “Most specialist initiatives are designed to compete directly for a share of the most profitable health-care system facility and ancillary revenue sources” [11]. Earlier in the process of integration, hospitals pursued economic integration with physicians as a response [3, 11]. However, declining profitability seems to be driving more recent joint ventures with hospitals or outright sales of ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient imaging centers [15, 49].

Discussion

Through a comprehensive review of medical and healthcare administrative, economic, and health policy literature over the past 20 years, we have categorized the changes in the healthcare environment and identified multiple factors driving physician-hospital alignment (summarized in Table 1). Motivations for orthopaedic surgeons parallel those of other physicians, with the addition of some factors particular to the specialty. Understanding the motivations for alignment can clarify goals for all stakeholders. In this review, we (1) identified the primary drivers of physician alignment with hospitals, including financial, healthcare reform, and cultural factors; (2) reviewed factors promoting alignment from the hospital perspective; and (3) assessed the drivers more specific to motivating orthopaedic surgeons to align with hospitals.

Table 1.

Factors influencing physician-hospital alignment

| Type of factor | Established physicians | Orthopaedic surgeons | New physicians | Hospitals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial | Declining reimbursement Increasing practice overhead Limited capital for expansion |

Same as other established physicians Orthopaedic service line often highly desired Significant financial impact of implant costs Ambulatory surgery centers, other ancillary services |

Increased educational debt More financial concerns, limited ability to start or buy into practice |

Declining reimbursement Need to assure service line |

| Regulatory | Electronic health record, meaningful use Physician Quality Reporting System Compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

Same as other established physicians | Same as other established physicians | Need to maintain emergency room coverage Perceived improved ability to control quality |

| Healthcare reform | Risk-based contracting Accountable care organizations |

Same as other established physicians | Same as other established physicians | Preparation for value-based payment Accountable care organizations |

| Cultural | Practice control in comanagement arrangements Participation in hospital leadership Lifestyle |

Same as other established physicians | Generational change in value of work-life balance | Involvement of physicians in hospital leadership |

Our analysis is limited by limitations of review of nonmedical or healthcare sources. Our search sought to include hospital administrative sources to reflect the hospital perspective. Given a relative dearth of literature in the orthopaedic or even true medical literature, this strategy produced the majority of the references. However, we recognize other business or economic literature may exist that we were not able to access. The majority of articles published outside of the core medical literature could raise concern for bias. We found concordant observations in the health policy, administrative, and economic literature with the available publications in peer-reviewed medical journals.

The most consistently identified factor driving physician-hospital alignment was economic concerns. Decreasing reimbursement combined with mounting costs of compliance with regulatory requirements challenges both physicians and hospitals, setting the stage for participation in alignment models. Regulatory and legal changes with civil monetary penalty, the Federal Anti-Kickback Statute, and Stark laws eliminated some of the opportunities for ancillary income, thus contributing to the economic forces that promote physicians interest in alignment. However, the antitrust laws also complicate alignment models [31, 51, 54]. Cultural aspects proved to be a commonly identified driver for physicians seeking alignment. Even in the setting of rapid changes in the healthcare environment, physicians recognize the need to maintain leadership and influence over their service line and hospital setting. However, while several references identified desire to regain or maintain leadership as a reason for physicians collaborating with hospitals, even more sources elaborated on a cultural shift in the other direction. Younger physicians prioritize work-life balance when seeking practice models, and financial concerns starting with educational debt deter interest or ability to invest in starting or buying into a practice. Even established physicians express desire for income guarantees or freedom from the challenges of running a business. Understanding these changing expectations from both new and established physicians can impact how surgical practices are able to recruit new partners. With all these factors driving physicians to consider employment, established practices may need to align with hospitals to access manpower to cover call and subspecialty needs. Further, beyond employment, other models of professional service agreements with hospitals can be pursued.

All the described factors influence orthopaedic surgeons, but factors specific to the specialty have been dominated by the case of total joint arthroplasty. With decreasing physician reimbursements and rising costs, collaboration with hospitals through comanagement allows potential for regaining profitability of this service line. From the hospital perspective, engaging surgeons in selection and pricing of implants has been important and will likely become more important as bundled payment models proliferate. Increasingly, beyond total joint arthroplasty, controlling costs of implant and nonimplant technologies has prompted many hospitals to seek collaboration with orthopaedic surgeons.

Shared risk between healthcare payers and providers is rapidly evolving as a leading paradigm for reimbursement. The allocation of risk/reimbursement between the hospital and the surgeon can be expected to be an area of increasing contention. Distribution of the sum for a bundled payment or payment of shared savings in an ACO model will be decisions that may test the physician-hospital alignment. Going forward, surgeons and all physicians may find, while alignment is necessary for achieving some goals, there may be increasing controversy over disparate goals in other areas.

As more innovative models of healthcare delivery emerge, we may need to consider: is the physician-hospital relationship mandatory? As the ambulatory surgery center model revealed, hospitals do not have a monopoly on the operating room. Specialty hospitals reveal “focused factories” can improve efficiencies. While treatment of acute injuries and patients with comorbidities requires resources classically limited to a general hospital, advances in technology at all levels permit delivery of even more services in novel settings.

The reasons driving physician-hospital alignment in general and specifically in the field of orthopaedic surgery are multifactorial. Identification of which strategies will lead to sustainable, patient-centered value will be paramount as our healthcare payment and delivery systems shift from an emphasis on volume to value.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Bielman, MLIS, for assistance with literature searches and document procurement and Vanessa Chan, MPH, for assistance with preparation of this manuscript.

Appendix 1

Search Strategies Used in Our Literature Review

| MeSH® terms | Number of articles retrieved |

|---|---|

| (“hospital-physician relations”[MeSH Terms] OR (“hospital-physician”[All Fields] AND “relations”[All Fields]) OR “hospital-physician relations”[All Fields] OR (“hospital”[All Fields] AND “physician”[All Fields] AND “relations”[All Fields]) OR “hospital physician relations”[All Fields]) AND alignment[All Fields] | 30 |

| (“hospital”[All Fields] AND “physician”[All Fields]) OR “hospital physician”[All Fields]) AND alignment[All Fields] | 9 |

| “Physician Incentive Plans”[MAJR] AND (“insurance”[MeSH Terms] OR “insurance”[All Fields]) | 4 |

| (“hospitals”[MeSH Terms] OR “hospitals”[All Fields] OR “hospital”[All Fields]) AND purchasing[All Fields] AND (“orthopaedic”[All Fields] OR “orthopedics”[MeSH Terms] OR “orthopedics”[All Fields] OR “orthopedic”[All Fields]) | 10 |

| (“Physician Incentive Plans/economics”[MeSH Terms] AND “Physician Incentive Plans/organization and administration”[MAJR]) AND “Physician Incentive Plans”[MAJR] | 15 |

| (physician[All Fields] AND ((“motivation”[MeSH Terms] OR “motivation”[All Fields] OR “incentive”[All Fields]) AND plans[All Fields]) AND ((“delivery of health care”[MeSH Terms] OR (“delivery”[All Fields] AND “health”[All Fields] AND “care”[All Fields]) OR “delivery of health care”[All Fields] OR (“delivery”[All Fields] AND “healthcare”[All Fields]) OR “delivery of healthcare”[All Fields]) AND integrated[All Fields]) AND (“economics”[Subheading] OR “economics”[All Fields] OR “economics”[MeSH Terms]) | 5 |

| (“delivery of health care”[MeSH Terms] OR (“delivery”[All Fields] AND “health”[All Fields] AND “care”[All Fields]) OR “delivery of health care”[All Fields]) AND (“economics”[Subheading] OR “economics”[All Fields] OR “economics”[MeSH Terms]) AND Competition[All Fields] AND (“health services”[MeSH Terms] OR (“health”[All Fields] AND “services”[All Fields]) OR “health services”[All Fields]) AND (“united states”[MeSH Terms] AND English[lang] | 4 |

| “Delivery of Health Care, Integrated/economics”[MeSH Terms] AND “Delivery of Health Care, Integrated/legislation and jurisprudence”[MeSH Terms] AND “Delivery of Health Care, Integrated/organization and administration”[All Fields] AND English[lang] | 2 |

| (“orthopedics”[MeSH Terms] OR “orthopedics”[All Fields]) AND (“motivation”[MeSH Terms] OR “motivation”[All Fields] OR “incentives”[All Fields]) AND (“ethics”[Subheading] OR “ethics”[All Fields] OR “ethics”[MeSH Terms]) AND English[lang] | 1 |

| “orthopedics/economics”[MeSH Terms] AND reimbursement[All Fields] AND (“insurance”[MeSH Terms] OR “insurance”[All Fields]) AND English[lang] | 1 |

The remaining articles in the primary MEDLINE® search were located through the Related Citations search function in PubMed.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, CA, USA) and Kaiser Permanente, San Diego (San Diego, CA, USA).

References

- 1.Berenson RA, Ginsburg PB, May JH. Hospital-physicians relations: cooperation, competition, or separation? Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:w31–w43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns LR, Housman MG, Booth RE, Jr, Koenig A. Implant vendors and hospitals: competing influences over product choice by orthopedic surgeons. Health Care Manage Rev. 2009;34:2–18. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000342984.22426.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns LR, Muller RW. Hospital-physician collaboration: landscape of economic integration and impact on clinical integration. Milbank Q. 2008;86:375–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantlupe J. Leadership, physician alignment, and service line success. HealthLeaders Magazine. 2012;15:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casalino L, Robinson JC. Alternative models of hospital-physician affiliation as the United States moves away from tight managed care. Milbank Q. 2003;81:331–351, 173–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician self referral. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud-and-Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/index.html. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 7.Ciliberto F, Dranove D. The effect of physician-hospital affiliations on hospital prices in California. J Health Econ. 2006;25:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohn KH, Gill SL, Schwartz RW. Gaining hospital administrators’ attention: ways to improve physician-hospital management dialogue. Surgery. 2005;137:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosson FJ. The delivery system matters. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:1543–1548. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuellar AE, Gertler PJ. Strategic integration of hospitals and physicians. J Health Econ. 2006;25:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson RA, Thomas MS, Naughton BB. Rethinking specialist integration strategies. Healthc Financ Manage. 1999;53:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiConsiglio J. Biggest winners: optimizing group purchasing relationships. Mater Manag Health Care. 2010;19:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dirschl DR, Goodroe J, Thornton DM, Eiland GW. AOA Symposium. Gainsharing in orthopaedics: passing fancy or wave of the future? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2075–2083. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edmiston G, Wofford D. Physician alignment: the right strategy, the right mind-set. Healthc Financ Manage. 2010;64:60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felland LE, Grossman JM, Tu HT. Key findings from HSC’s 2010 site visits: health care markets weather economic downturn, brace for health reform. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2011;135:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fighting back against price increases for ortho implants. OR Manager. 2001;17:1, 8–10. [PubMed]

- 17.Goodroe JH. Using comparative data to improve healthcare value. Healthc Financ Manage. 2010;64:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grauman DM, Harris JM. 3 durable strategies for physician alignment. Healthc Financ Manage. 2008;62:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grauman DM, Neff G, Johnson MM. Capital planning for clinical integration. Healthc Financ Manage. 2011;65:56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grayson M. Back to the future. Anon! Hospitals & Health Networks. 2009;38:4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harbeck C. Hospital-physician alignment: the 1990s versus now. Healthc Financ Manage. 2011;65:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartzell ST, Sturm MR, Lopez ED. Choosing the right physician practices. Healthc Financ Manage. 2011;65:58–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healy WL. Gainsharing: a primer for orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1880–1887. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosler FW, Nadle PA. Physician-hospital partnerships: incentive alignment through shared governance within a performance improvement structure. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2000;26:59–73. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(00)26005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iglehart JK. The emergence of physician-owned specialty hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:78–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr043631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs C. Collaborating on quality improvement: don’t wait for payment reform. Healthc Financ Manage. 2009;63:22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Japsen B. Columbia offering stake to academic docs. Mod Healthc. 1996;26:78, 80. [PubMed]

- 28.Johnson R, Thompson WC, Phillips J, Stubbefiel A, James J. Ties that bind: developing hospital-physician alignment. HealthLeaders Magazine. 2008;11:RT1–RT6.

- 29.Kennedy D, Clay S, Collier DK. Financial implications of moving to a physician employment model. Healthc Financ Manage. 2009;63:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ketcham JD, Furukawa MF. Hospital-physician gainsharing in cardiology. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:803–812. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koster JF, Smithson KW. Customize physician incentive programs to fit the individual doctor’s needs. Med Netw Strategy Rep. 1996;5:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liebhaber A, Draper DA, Cohen GR. Hospital strategies to engage physicians in quality improvement. Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2009;127:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovrien K, Peterson L. Hospital-physician alignment: making the relationship work. Healthc Financ Manage. 2011;65:72–76, 78. [PubMed]

- 34.MacNulty A, Kennedy D. Beyond the models: investing in physician-hospital relationships. Healthc Financ Manage. 2008;62:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacNulty A, Reich J. Survey and interviews examine relatonships between physicians and hospitals. Physician Exec. 2008;34:48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madison K. Hospital-physician affiliations and patient treatments, expenditures, and outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:257–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcus RE, Zenty TF, 3rd, Adelman HG. Aligning incentives in orthopaedics: opportunities and challenges—the Case Medical Center experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2525–2534. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0956-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.May EL. Well-balanced partnerships: achieving physician-hospital alignment. Healthc Exec. 2011;26:18–20, 22–14, 26. [PubMed]

- 39.McGowan RA. Strengthening hospital-physician relationships. Healthc Financ Manage. 2004;58:38–40, 42. [PubMed]

- 40.Mitlyng JW, Laskowski RJ. A new tool for hospital/ physician strategic alignment: the subsidiary physician corporation. Physician Exec. 2008;34:40–42, 44–45. [PubMed]

- 41.O’Malley AS, Bond AM, Berenson RA. Rising hospital employment of physicians: better quality, higher costs? Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2011;136:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pizzo JJ, Grube ME. Keys to lasting partnerships. Trustee. 2011;64:23–26, 21. [PubMed]

- 43.Rice JA, Sagin T. New conversations for physician engagement: five design principles to upgrade your governance model. Healthc Exec. 2010;25:66, 68–70. [PubMed]

- 44.Sandrick K. Hospital-physician alignment. Trustee. 2009;62:19–22, 12. [PubMed]

- 45.Sears N. Hospital-physician alignment takes on new urgency. Healthcare Purchasing News. 2008;32:50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serb C. Strategic savings: as supply costs climb, hospitals rethink their purchasing strategies. Hosp Health Netw. 2004;78:54–58, 60. [PubMed]

- 47.Simmons J. Quality: toward unity. HealthLeaders Magazine. 2009;12:52–53. [Google Scholar]

- 48.StarkLaw.org. Stark Law information, regulations, legal solutions. Available at: http://starklaw.org/stark_law.htm. Accessed June 30, 2012.

- 49.Terry K. Physician alignment. Hosp Health Netw. 2009;83:22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas JR. Hospital-physician alignment: no decision is a decision. Healthc Financ Manage. 2009;63:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson RC Jr, Bishop JR. Controlling costs: opportunities for physician-hospital collaborations and ventures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:S27–S32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Trybou J, Gemmel P, Annemans L. The ties that bind: an integrative framework of physician-hospital alignment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warner JJ, Herndon JH, Cole BJ. An academic compensation plan for an orthopaedic department. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:64–72. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31803372f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson NA, Ranawat A, Nunley R, Bozic KJ. Executive summary: aligning stakeholder incentives in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2521–2524. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0909-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuckerman HS, Hilberman DW, Andersen RM, Burns LR, Alexander JA, Torrens P. Physicians and organizations: strange bedfellows or a marriage made in heaven? Front Health Serv Manage. 1998;14:3–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]