Abstract

Inflammation plays a significant role in many disease processes. Development in molecular imaging in recent years provides new insight into the diagnosis and treatment evaluation of various inflammatory diseases and diseases involving inflammatory process. Positron emission tomography using 18F-FDG has been successfully applied in clinical oncology and neurology and in the inflammation realm. In addition to glucose metabolism, a variety of targets for inflammation imaging are being discovered and utilized, some of which are considered superior to FDG for imaging inflammation. This review summarizes the potential inflammation imaging targets and corresponding PET tracers, and the applications of PET in major inflammatory diseases and tumor associated inflammation. Also, the current attempt in differentiating inflammation from tumor using PET is also discussed.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography, inflammation, molecular imaging, biomarker.

1. Introduction

Inflammation acts as the initial host defense against invasive pathogens and other inciting stimulus. It plays an important role in tissue repair and elimination of harmful pathogens. Although the inflammatory response is essential for host defense, it is very much a double-edged sword. Inappropriate inflammatory reaction or delay in the resolution of inflammation will damage adjacent normal cells in the tissue. Microbial infection is most commonly caused by bacteria and viruses, while sterile inflammation is triggered by sterile stimulus involving physical, chemical or metabolic noxiae such as burns, trauma, and dead cells 1, 2. Similar to infection, the sterile inflammatory process also includes the recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, and the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines 3. Accumulating evidence supports that various human diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer's disease, atherosclerosis, and many autoimmune diseases, are related to sterile inflammation. These diseases happen and evolve, at least in part, due to the improper resolution of inflammatory processes 4.

Molecular imaging can visualize, characterize, and measure the biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels in humans and other organisms 5. Many imaging techniques are incorporated in the molecular imaging realm, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET), single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), optical imaging, ultrasound 6, and photoacoustic imaging 7. Each technique has its own unique applications, advantages, and limitations. Compared with other imaging modalities, PET features high sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, PET has become one of the most frequently used molecular imaging techniques in the clinic. Besides, the hybridization of PET with CT and MR provides additional anatomical details to the lesions, allowing for both high sensitivity molecular and anatomical/functional imaging.

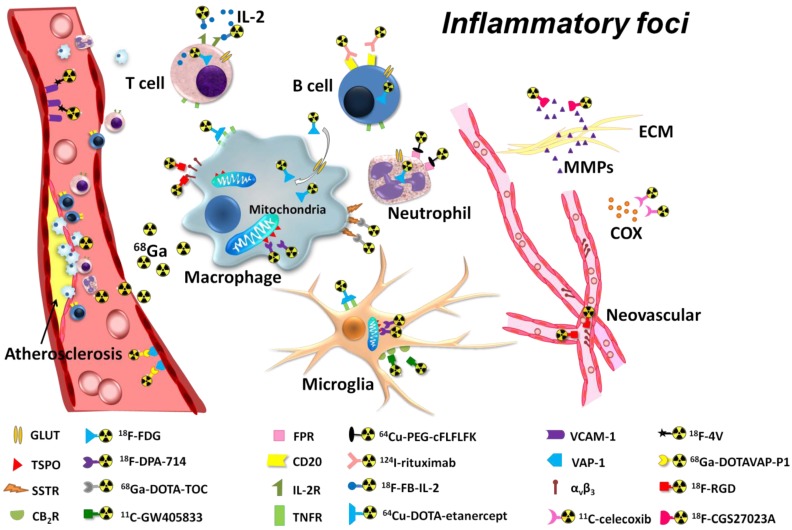

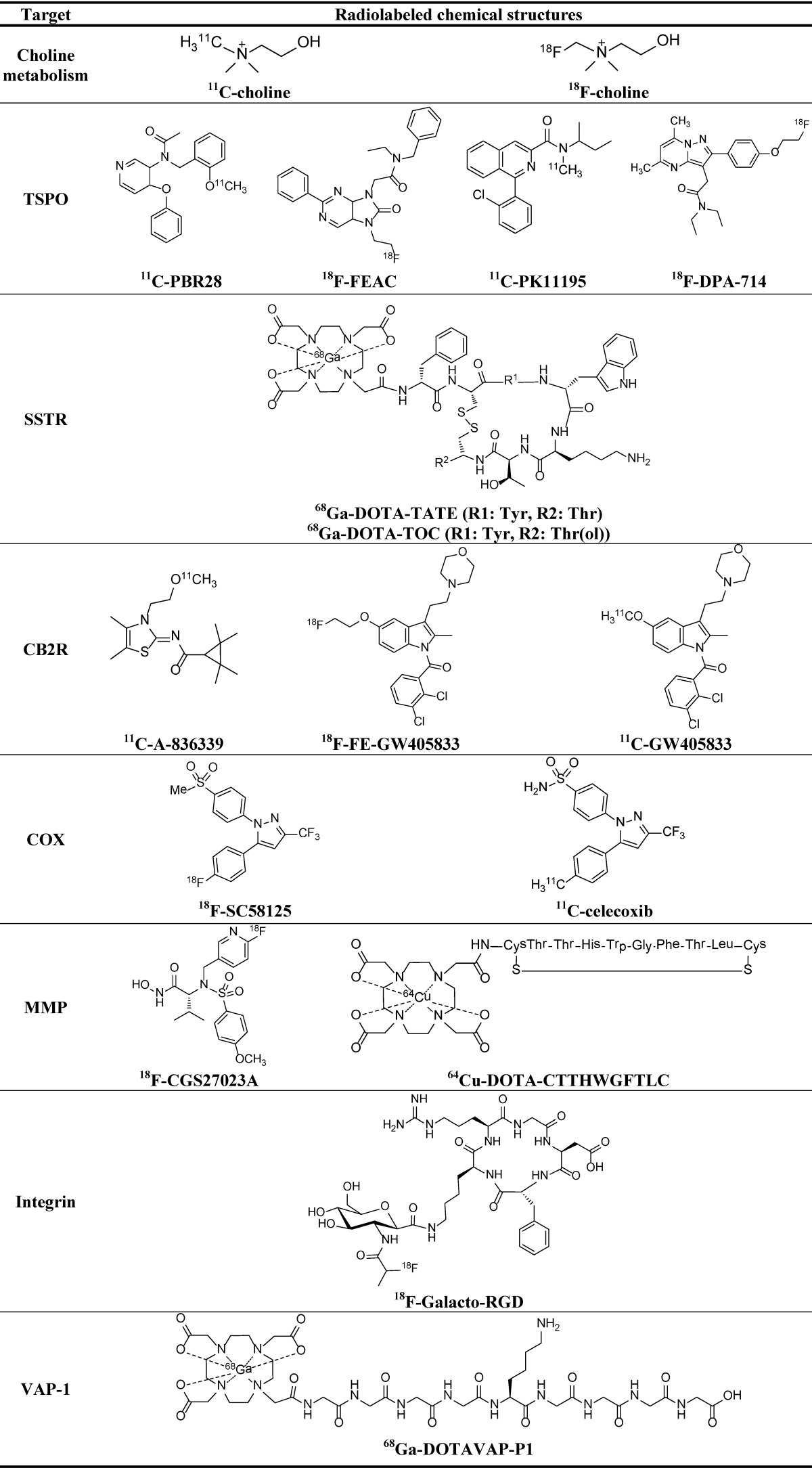

18F-FDG (2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoro-D-glucose) is the most extensively used PET imaging tracer and has been applied successfully in tumor detection, staging, and therapy evaluation, as well as in cardiovascular and neurological diseases 8. In inflammatory diseases, 18F-FDG PET also has its value, particularly in atherosclerosis and some arthritis diseases 9, 10 (Table 1). However, 18F-FDG PET imaging of inflammation tends to give false-positive results, especially in patients with cancer. Moreover, the high tracer accumulation in the heart and brain makes it difficult to detect inflammatory foci near those organs or tissues. Consequently, new imaging tracers and targets for more specific inflammation detection and therapy evaluation are under intensive investigation. PET imaging with these new tracers greatly improved our understanding of the mechanism of inflammation and increased the diagnostic specificity and accuracy of inflammatory foci. As summarized in Figure 1, various radiopharmaceuticals have been developed for PET imaging of inflammation, targeting different biomarkers from macrophages to angiogenesis. In this review, we will summarize these potential imaging targets and tracers for inflammation PET imaging, the applications of PET in major inflammatory diseases, and tumor associated inflammation imaging. The current attempt to differentiate inflammation from tumor using PET is also elaborated. A discussion of pathogen targeted PET imaging is beyond the scope of this review.

Table 1.

18F-FDG imaging of sterile inflammatory diseases.

| Diseases | Study type | References | Tracers | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerotic inflammation |

Clinical | Li, 2012 11 | 18F-FDG, 68Ga-DOTATATE ( PET/CT) | In patients with neuroendocrine tumors or thyroid cancer |

| Preclinical | Silvola, 2011 12 | 18F-FDG, 68Ga (microPET/CT) | In LDLR-/- ApoB100/100 mice | |

| Clinical | Yarasheski, 2012 13 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | In HIV-infected patients | |

| Vasculitis | Clinical | Bissonnette, 2012 14 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | In psoriasis patients |

| Clinical | Maki-Petaja, 2012 15 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | Anti-TNF therapy, in rheumatoid arthritis patients | |

| Clinical | Tegler, 2012 16 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | Aortic aneurysms | |

| Clinical | Tezuka, 2012 17 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | Takayasu arteritis | |

| Clinical | Sarda-Mantel, 2012 18 | 18F-FDG, 18F-DPA714, 18F-FCH (PET) | Abdominal aneurysms | |

| Clinical | Kim, 2010 19 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | In T2DM patients | |

| Valvular inflammation | Clinical | Dweck, 2012 20 | 18F-FDG, 18F-NaF (PET/CT) | |

| Arthritis | Preclinical | Irmler, 2010 21 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | With etanercept therapy |

| Clinical | Yamashita, 2012 22 | 18F-FDG (PET/CT) | Differentiation among PMR, SpA and RA | |

| Skin inflammation | Preclinical | McLarty, 2011 23 | 18F-FDG, 18F-scyllo-inositol (microPET) | |

| Preclinical | Autio, 2010 24 | 18F-FDG, 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 (animal/brain PET) | ||

| Bone inflammation | Preclinical | Brown, 2012 25 | 18F-FDG (microPET) | Differentiation with osteomyelitis |

| Myocardial inflammation |

Clinical | Lee, 2012 26 | 18F-FDG (PET/MR) | Post-myocardial infarction |

TNF: tumor necrosis factor T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus RA: rheumatoid arthritis PMR: polymyalgia rheumatic SpA: seronegative spondyloarthritis.

Figure 1.

PET inflammation imaging biomarkers within the inflammatory foci.

2. Biomarkers for inflammation imaging

After being triggered by various stimuli, the inflammation cascade begins with the release of various pro-inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines, and leukotrienes by resident inflammatory and endothelial cells. Next, vascular permeability is increased with the infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages. In the late phase, the release of pro-resolving mediators causes apoptosis of inflammatory cells and leads to the termination of inflammation. All these key inflammatory mediators and specific features of dominant inflammatory cells are potential targets for either visualization or treatment of inflammatory disorders. In this section, we will cover the major biomarkers of inflammation and the corresponding probes for PET imaging, including the metabolic rate and membrane markers of inflammatory cells, cytokines, and vessels within inflamed foci, as well as some newly identified inflammation related targets.

2.1 Metabolic activity of inflammatory cells

2.1.1 Glucose metabolism

High glucose metabolism and consequent high FDG accumulation are not unique phenomena for malignant cells. Benign processes including inflammatory disorders also show increased FDG uptake, which bring about false positiveness in tumor detection 27. As the key indicators and core participants in inflammatory foci, infiltrating inflammatory cells utilize glucose at a much higher level than peripheral non-inflammatory cells. Therefore, the increased glucose metabolism of inflamed foci due to oxidative burst in the inflammatory cells become an important and most frequently used target in PET imaging of inflammation. CT or MRI is often combined with 18F-FDG PET to increase the diagnostic accuracy. Indeed, 18F-FDG has been used intensively in a great number of inflammatory diseases and therapy evaluations, part of which are summarized in Table 1. For details of the applications of 18F-FDG in inflammation imaging, please refer to previously published review articles 28, 29.

2.1.2 Choline metabolism

Choline is an important precursor of phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, two classes of phospholipids that are abundant in cell membranes. The phosphatidylcholine catabolism by many nucleated cells, mostly proliferative cells, serves as an imaging target both in cancers and in some inflammatory diseases. PET using radiolabeled choline has been used to image prostate cancer 30-33. By targeting the macrophages and monocytes in inflammatory diseases, choline is also used to image atherosclerosis 34-36 and to evaluate necrosis after brain tumor radiation therapy 37. Matter et al. found via ex vivo micro-autoradiography that 18F-choline had greater sensitivity in detecting atherosclerotic plaques than FDG (84% versus 64%) 34. In a clinical setting with five patients, Bucerius et al. 36 demonstrated the feasibility of 18F-choline to image structural wall alteration in humans. A major advantage offered by 18F-choline imaging over 18F-FDG is the lack of 18F-choline uptake in the myocardium 38. Thus choline may be superior to FDG in detecting coronary plaques.

2.2 Membrane markers of inflammatory cells

2.2.1 Translocator protein (TSPO)

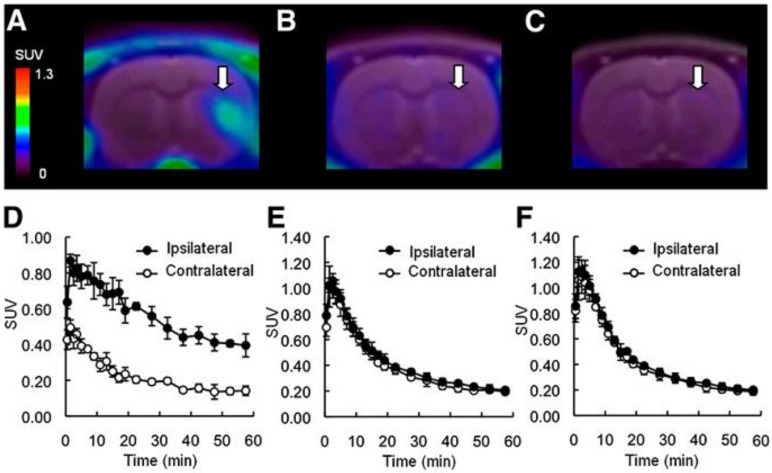

Formerly known as peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR), the 18 kDa translocator protein is located on the outer mitochondrial membrane and can bind with cholesterol and various classes of drug ligands. TSPO is ubiquitously expressed in peripheral tissues but is only minimally expressed in the healthy human brain. Previous studies found high TSPO expression in macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes 39-41, activated microglia, and astrocytes 42-46. Microglia have been found to contribute to neuroinflammation in many types of central nervous system (CNS) disorders, such as stroke, multiple sclerosis (MS) 45, Alzheimer's disease (AD) 47, Parkinson's disease (PD) 48, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) 49, and epilepsy 50. Therefore, TPSO expressed on microglial cells in CNS emerges as a promising target for PET imaging of neuroinflammation. The most studied PET tracers binding to TPSO are 11C or 18F-labeled isoquinoline carboxamide PK11195 (1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinoline carboxamide) 40, 43 and more recently 11C-PBR28 (N-(2-[11C]methoxybenzyl)-N-(4-phenoxypyridin-3-yl)acetamide) 42, 51. Syntheses of these tracers are now mostly automated and are efficient, which guarantees the future application in the clinic. In preclinical studies, for example, Yui et al. 52 used TSPO radioligands 18F-FEAC (N-benzyl-N-ethyl-2-[7,8-dihydro-7-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-8-oxo-2-phenyl-9H-purin-9-yl]acetamide) and 18F-FEDAC (N-benzyl-N-methyl-2-[7,8-dihydro-7-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-8-oxo-2-phenyl-9H-purin-9-yl]acetamide) in a rat brain ischemia model and found both tracers could accumulate in the infarct areas, and the uptake could be inhibited by pretreatment with TSPO ligands PK11195 or AC-5216 (N-benzyl-N-ethyl-2-(7-methyl-8-oxo-2-phenyl-7,8-dihydro-9H-purin-9-yl)acetamide) (Figure 2). In an AD model, Maeda et al. 53 found elevated TSPO levels in tau-rich hippocampus and entorhinal cortex region of the brain by 11C-AC-5216 microPET, and there was a constant increase of tracer uptake in the brain region with the progression of AD. In a clinical study, Gulyás et al. used 11C-vinpocetine (ethyl apovincaminate) to evaluate the TSPO levels in the brains of stroke patients and found different uptake patterns in ischemic cores and peri-infarct zone over time 54.

Figure 2.

Representative PET images and time activity curves of 18F-FEAC in infarcted rat brains 7 days after surgery. PET images were generated by averaging the whole 60-min scans and were overlaid on MR images. Arrows indicate infarcted areas. Shown are control rats (A and D), rats pretreated with AC-5216 (B and E), and rats pretreated with PK11195 (C and F) (Yui, 2010 52).

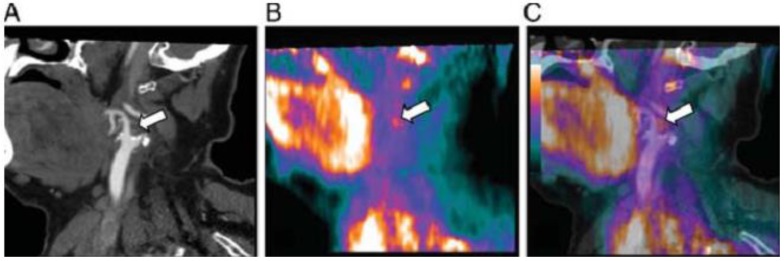

PET imaging using TSPO as an inflammation biomarker has also been reported for atherosclerosis detection with promising results 39, 40, 55, 56. Using autoradiography, Bird and colleagues 39 found both 3H-DAA1106 ((N-5-fluoro-2-phenoxyphenyl)-N-(2,5-dimethoxybenzyl)acetamide) and 3H-(R)-PK11195 have the potential to quantify the macrophage content in human atherosclerotic plaques obtained from six patients. More recently, Gaemperl et al. 40 successfully applied 11C-PK11195 to image intraplaque inflammation in carotid atherosclerosis in 36 patients with carotid stenosis and found a significant correlation between 11C-PK11195 uptake ratio and autoradiographic measurement of TSPO binding sites (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Computed tomography angiography (A), 11C-PK11195 PET (B), and PET/CT fusion (C) in a 52-year-old patient with right amaurosis fugax 2 weeks prior to the scans. The white arrows denote a focal area of 11C-PK11195 uptake in the carotid bifurcation (Gaemperl, 2011 40).

TSPO PET has also been used to image inflamed lung and liver diseases. In normal lungs, TPSO is expressed in bronchial, bronchiole epithelium, and submucosal glands in intrapulmonary bronchi. In a lipopolysaccharide induced infectious lung inflammation model, PET imaging using TSPO radio-ligands 18F-FEDAC, 11C-(R)- PK11195 41, and 123I-(R)-PK11195 57 all showed significant lung lesion uptake, mainly from activated neutrophils and macrophages. Due to its higher lesion accumulation, 18F-FEDAC was claimed to be superior to 11C-(R)-PK11195. In a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Xie et al. confirmed from autoradiography and histopathology that 18F-FEDAC uptake in NAFLD was mainly from injured hepatocytes and CD11b+ macrophages/activated lymphocytes located in the necroinflammatory loci 58, suggesting that inflammation may also contribute to NAFLD process, and 18F-FEDAC may be a potential tracer for NAFLD imaging.

2.2.2 Somatostatin Receptor

Somatostatin receptor (SSTR) has been investigated as a target for neuroendocrine tumor imaging. SPECT imaging of SSTR expression in neuroendocrine tumors has been well-established for lesion detection and therapeutic monitoring 59-62. Since a high level of SSTR expression was found on activated lymphocytes and macrophages 63, this receptor has the potential to be used as a new target for inflammation imaging. Compared with tumor imaging, only limited studies have reported using PET tracers to target SSTR in inflammatory disorders or diseases with mild/intense inflammatory infiltration, including atherosclerotic inflammation 11, 64, inflamed pulmonary fibrosis 65, carcinoids, and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors 66.

TATE (Tyr3-octreotate) and TOC (Tyr3-octreotide) are analogues of octreotide that bind to the somatostatin type 2 receptor (SSTR-2). 1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N",N"'-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) conjugation of these peptides allows for stable chelation to a variety of radiometals such as 111In, 177Lu, 90Y, 68Ga and 64Cu 67-69. In atherosclerosis imaging, clear plaque uptake of 68Ga-DOTA-TATE or 68Ga-DOTA-TOC in carotid arteries was found, and the uptake has strong association with known risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Due to the much lower uptakes in myocardium, these tracers provided clearer and more consistent detection of macrophage accumulation than FDG in coronary arteries plaques 70, 71.

2.2.3 Type 2 Cannabinoid Receptor (CB2R)

There are at least two subtypes of CBRs in the endocannabinoid system. CB1R is involved in the immune system and mainly expressed in the CNS. CB2R is expressed at a much lower level in the normal brain tissue compared to CB1R. Under pathological conditions, especially immune-mediated pathologies, up-regulation of CB2R is found on activated microglia, the resident immune cells in the CNS 72. Three major groups of CB2R ligands can be labeled with radioisotopes for PET, including pyrazole derivatives, indole derivatives, and quinoline derivatives 73. For 11C-labeling of pyrazole derivatives, a boron precursor was first synthesized and later reacted with 11C-methyl iodide via a Suzuki coupling 74. Indole derivatives such as GW405833 (1-(2,3-dichlorobenzoyl)-5-methoxy-2-methyl-3-[2-(4-morpholinyl)ethyl]-1H-indole) are usually labeled with 18F by alkylation of the phenol precursor with 1-bromo-2-18F-fluoroethane 75. Labeling the quinoline derivatives was readily achieved by methylating the precursor 7-methoxy-2-oxo-6-pentyloxy-1,2-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid with methyl triflate 73. The first in vivo PET of brain CB2R was performed in 2010 by Horti and his group 76. Mice with lipopolysaccharide induced neuroinflammation showed a significant increase in 11C-A-836339 uptake in all brain regions. The uptake could be blocked by a CB2R selective ligand, indicating the specificity of the tracer accumulation. In the same study, brain uptake of 11C-A-836339 (2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid (3-(2-methoxy-ethyl)-4,5-dimethyl-3H-thiazol-(2Z)-ylidene)amide) uptake in AD mice was blocked only in regions with high Aβ amyloid deposition. In another imaging study, Even et al. used two tracers, 11C-Sch 225336 (N-[(1s)-1-[4-[[4-methoxy-2-[(4-[11C]methoxyphenyl)sulfonyl)-phenyl]sulfonyl] phenyl]ethyl]methanesulfonamide] and 18F-FE-GW405833, and found intense tracer accumulation in the brain of a rat model with hCB2R overexpression in the right striatum 75, 77. Vandeputte et al. 78 imaged brain CB2R based on a reporter gene system, in which 11C-GW405833 clearly accumulated in the brain region with pre-injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors encoding hCB2R. These promising results on CB2R targeted PET imaging warrant further applications in a wide range of neuroinflammatory diseases and evaluation of the therapeutic value of novel CB2R-related drugs. However, the exact role of CB2R in CNS still remains to be fully elucidated, and more in vivo studies using relevant disease models should be conducted to get a better understanding.

2.2.4. Other membrane markers on inflammatory cells

Formyl peptide receptor (FPR) is a type of G-protein coupled receptor expressed on neutrophils, responsible for the leukocyte migration cascade in the inflammation process. Using FPR-specific ligand cFLFLFK, neutrophil infiltration in the inflammatory foci could be visualized with various imaging modalities, including MRI 79, optical imaging 80, SPECT 81 and PET 82, 83. PET, using cFLFLFK-PEG-64Cu, could visualize inflammatory foci within the lung in an animal model of lung inflammation induced by Klebsiella pneumonia 82. Moreover, B lymphocyte CD20 antigen imaging has been utilized to visualize synovial membrane in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 84. Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, was radiolabeled with 124I for PET/CT imaging in six patients with rheumatoid arthritis. 124I-rituximab showed increased uptake in most clinically symptomatic joints, indicating the infiltration of B lymphocytes.

2.3. Inflammatory cytokines

2.3.1. COX

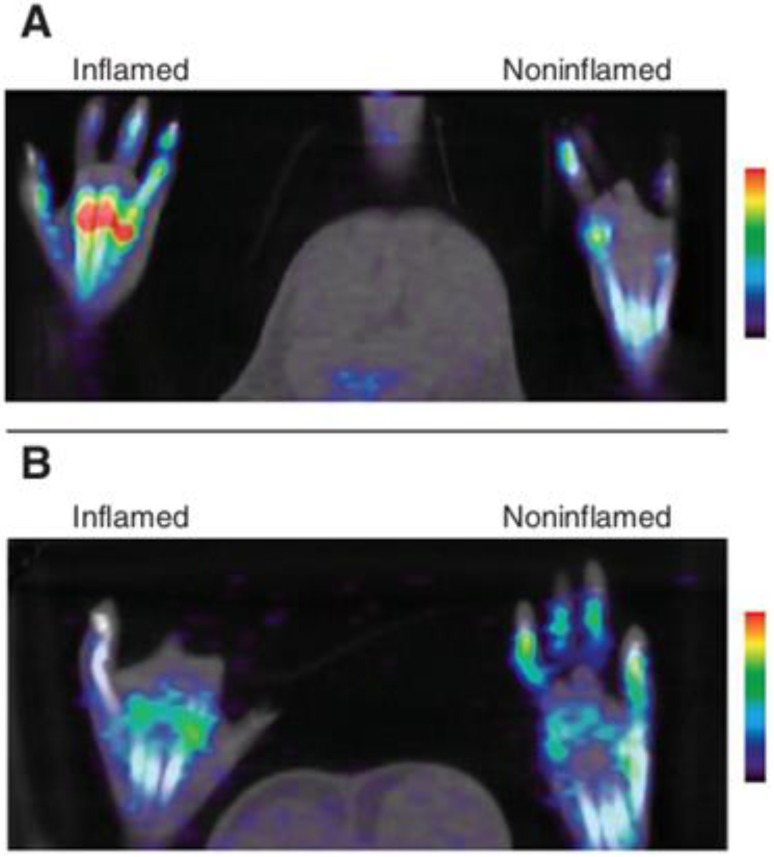

Cyclooxygenase (COX), also known as prostaglandin H, is an enzyme responsible for the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins. COX is the target of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 85 . In addition, COX is an integral membrane glycoprotein which can be induced by acute and chronic inflammatory stimulations. Thus far, three COX subtypes (COX-1, 2, and 3) have been identified. Among them, the inducible isoform COX-2 plays a pivotal role in cancer, cardiac/cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer's/Parkinson's disease, and response to inflammatory stimuli, especially neuroinflammation 86, 87. Celecoxib (4-(5-p-tolyl-3-trifluoromethylpyrazol-1-yl)benzenesulfonamide) is broadly used as a selective COX-2 inhibitor to treat inflammatory diseases. Imaging tracers have also been developed using celecoxib and some other COX inhibitors by radiolabeling them with either 18F or 11C. Reported PET tracers include 18F-desbromo-Dup-697 (2-(4-18F-fluorophenyl)-3-[4-(methylsul-fonyl)phenyl]thiophene) 88, 18F-SC58125 (1-[4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl]-5-(4-18F-fluorophenyl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazole) 89, 11C-celecoxib 90, and 11C-rofecoxib (4-(4-11C-methylsulfonylphenyl)-3-phenyl-5H-furan-2-one) 91. They have been used to image neuroinflammations 91-93, tumors 94-96, or experimental skin inflammation 96. However, most of the tracers showed unsatisfactory ex vivo or in vivo properties due to either non-specific bindings or low sensitivity in inflammatory foci, or both. Recently, Uddin et al. 96 reported an 18F-labeled celecoxib derivative in a rat skin model of inflammation. This derivative featured higher COX-2 inhibitory activity than celecoxib but much less defluorination rate than other 18F-based agents. From microPET/CT imaging, they found significant tracer uptake in the inflamed paw induced by carrageenan, which could be inhibited by celecoxib pretreatment, indicating the specificity of the tracer (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(A) COX-2 targeted microPET/CT imaging of mouse paw inflammation induced by carrageenan. The PET image shows that the radiotracer targeted the swollen footpad (inflamed) selectively over the contralateral footpad (control). (B) PET image of rats with paw inflammation predosed with celecoxib (Uddin, 2011 96).

2.3.2 MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc- and calcium-dependent metalloproteases, which can degrade protein components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) 97-100. MMPs and its inhibitors, MMPIs, control the balance of extracellular proteolysis, while increased MMPs activity is considered critical in many pathological processes including cancer, atherosclerosis, and some other inflammatory conditions. Therefore, in vivo imaging of MMP activity would be useful to detect MMPs in these disorders. The activity of MMPs has been visualized by various probes using optical imaging, which has been summarized in several previously published review articles 101, 102. Quite a few MMPIs have been successfully radiolabeled as imaging tracers, mainly for breast cancer detection 103. 99mTc and 123I coupled SPECT tracers targeting MMP have been broadly applied in vascular inflammation 104, 105 as well as tumor imaging. Several PET tracers have been reported, such as 64Cu-DOTA-CTTHWGFTLC 106, 18F-CGS27023A ((R)-2-(N-((6-18F-fluoropyridin-3-yl)methyl)-4-methoxyphenyl-sulphonamido)-N-hydroxy-3-methylbutanamide) derivative 49, and 11C-labelled counterpart of CGS27023A 107, for tumor imaging. In a PET study of vessel inflammation, Hartung et al. 108 used 124I-HO-MIP (CGS 27023A) in ApoE-/- mice after carotid ligation following a high-cholesterol diet. Intense tracer uptake in the carotid lesion was detected from microPET images, indicating increased local MMP activity (Figure 5). The imaging results were in accordance with histology and immunohistochemistry for MMP expression. In another study 103, 18F-MMPI was used in ApoE-/- mice on a high-cholesterol diet. Ex vivo PET/CT shows MMP-positive plaques in the inner curvature of the aorta.

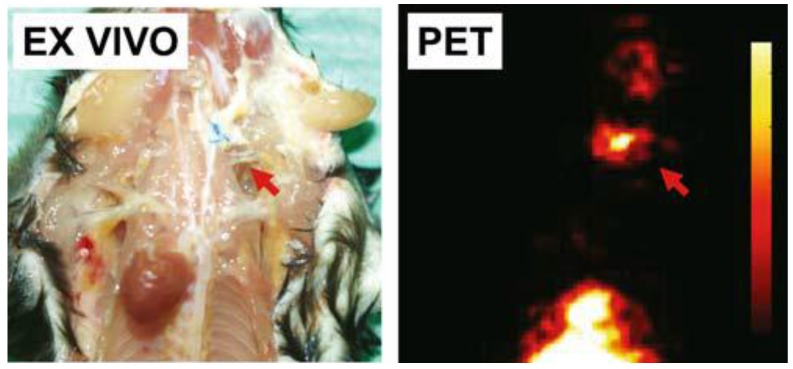

Figure 5.

Site of ligated left common carotid artery (left panel) and a corresponding whole body coronal slice (0.4 mm thick) through a left carotid lesion (right panel) 4 weeks after ligation and a high cholesterol diet in an apoE-/- mouse. Intense uptake of the radiolabeled broad spectrum MMP inhibitor 124I-HO-MPI in the left carotid lesion (arrow) 30 min after intravenous injection is visible using high-resolution small animal PET (Hartung, 2007 108).

2.3.3 IL-2

Interleukin (IL)-2 is a small single-chain glycoprotein (15.5 kDa) of 133 amino acids synthesized and secreted by activated T lymphocytes, especially CD4+ and CD8+ Th1 lymphocytes. T lymphocyte activation is seen in many types of inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory degenerative diseases, graft rejection, tumor inflammation, organ-specific autoimmune diseases, and adipose inflammatory insulin resistance 109. IL-2 binds with high affinity to the cell membrane IL-2 receptor, which is mainly expressed on the cell surface of activated T lymphocytes. PET imaging of activated T lymphocytes by radiolabeled IL-2 therefore provides an in vivo, dynamic approach in studying the immune-cell infiltration in these inflammatory diseases. Previously, 123I and 99mTc labeled IL-2 have been used in many chronic inflammatory diseases, such as autoimmune diseases 110, coeliac disease 111, and vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques 112 via SPECT imaging. However, routine application of this technique was limited because the labeling procedures is complex and the spatial resolution of SPECT is not high enough. Recently, Gialleonardo et al. reported the labeling of IL-2 with N-succinimidyl 4-18F-fluorobenzoate (18F-SFB) for the synthesis of 18F-FB-IL-2 to detect activated T lymphocytes in inflammation 113. In one of their studies, SCID mice were inoculated with phytohemagglutinin-activated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMc) in Matrigel on the right flank while only Matrigel was injected as control on the left. At 60-90 min after cell inoculation, PET imaging found that 18F-FB-IL-2 could detect the implanted hPBMc on the right flank. However, the control side also showed tracer uptake, mainly around the Matrigel site. The authors claimed that it was probably due to the migration of hPBMc from right side to left as a result of Matrigel induced inflammation. They also performed a dynamic PET study in Wistar rats with xenografted hPBMC 114. Tracer accumulation to activated T cells was clearly observed and the kinetics of 18F-FB-IL-2 in an inflammatory lesion could be described by Logan graphical analysis and compartment modeling. These pilot studies suggest that 18F-FB-IL-2 is stable, biologically active, and allows for in vivo detection of activated T lymphocytes.

2.3.4 TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a cytokine that can contribute to cell apoptosis and organ dysfunction 115. In the early phase of inflammation, TNF-α increases the transport of white blood cells to the inflammation sites. In the late phase, TNF-α level is lowered and can cause the apoptosis of inflammatory cells to terminate further unnecessary inflammation. Many studies show that TNF-α is important in acute immune response to infection, injury, autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis 15 and psoriasis 14. Previously, our group used a PET tracer 64Cu-DOTA-etanercept, to image acute inflammatory process induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate, TPA) 116. MicroPET imaging showed high 64Cu-DOTA-etanercept uptake in the inflamed ear only during the early acute inflammatory phase but not the chronic inflammation phase, indicating that TNF-α contributes to the onset of acute inflammation (Figure 6, left). This imaging trend was confirmed by ex vivo enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay of TNF-α levels in the inflamed ears. Gao et al. synthesized 11C-labeled tricyclic Nec-3 necroptosis inhibitor 3,3a,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-benz[g]indazoles as a potential PET tracer for imaging TNF-α, but without in vivo evaluation 117.

Figure 6.

MicroPET imaging using 64Cu-DOTA-etanercept (left) and 64Cu-DOTA-RGD (right) of mouse right ear subjected to TPA challenge at various times. 64Cu-DOTA-etanercept showed intensive ear uptake only in acute inflammation phase, while 64Cu-DOTA-RGD showed chronic inflammatory ear uptake (Cao, 2007 116).

2.4 Targets on inflammation related vessels

2.4.1 Integrin receptor

Integrin αvβ3, a cell adhesion molecule, is overexpressed in various cancer cells 118, endothelial cells of neovessels 119, and also in some inflammatory cells such as macrophages 120, 121. The study of integrin αvβ3 in cancers and tumor related angiogenesis has been extensively investigated in the past two decades 122-124. RGD peptides containing the three amino acid sequence Arg-Gly-Asp, are αvβ3 specific ligands. Radiolabeled RGD peptides have been successfully tested in the clinic 125, complementing conventional FDG imaging. Recently, some chronic inflammatory conditions with inflammatory angiogenesis, such as inflammatory bowel disease 126 and rheumatoid arthritis 127, also showed the participation of integrin αvβ3 in the inflammatory neovessels in disease etiology and progression. Therefore, integrin αvβ3 emerges as a target for inflammation therapy as well as molecular imaging. Actually, studies on αvβ3 targeted treatment have shown success in several inflammatory diseases 127, 128. Several PET studies of inflammatory processes using radiolabeled RGD peptides have also been reported. Pichler et al. 129 used 125I-gluco-RGD and 18F-gluco-RGD to study 2,4,6-trinitrochlorobenzene (TNCB) induced delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (DTHR) model of inflammation and found chronic but not acute inflammatory ear had intensive tracer uptake, which could be further blocked by pre-injection of cold RGD. The imaging result was verified by histology and immunohistochemistry of αvβ3 expression in the inflammatory foci. These findings echo what we observed in acute and chronic ear inflammation models using a different αvβ3 radioligand, 64Cu-DOTA-E[c(RGDyK)]2}2 116 (Figure 6, right). Both studies suggest that radiolabeled RGD peptides can reflect the angiogenesis during chronic inflammatory process.

In addition to imaging inflammatory angiogenesis, using RGD peptide in atherosclerosis imaging also came with positive results. Laitinen et al. 130 found 18F-Galacto-RGD accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions of mouse aorta by small animal PET/CT, and the high tracer uptake was associated with macrophage density revealed by histology study. In another study using hypercholesterolemic LDLR-/- ApoB100/100 mice, the same group investigated the effect of lipid-lowering diet on plaque formation. They found that 18F-galacto-RGD uptake in the aorta from regular food group is significantly lower than that from the high-fat diet group, indicating lipid-lowering diet could decrease the formation of atherosclerosis. Overexpression of αv and β3 integrins on macrophages in the aorta was confirmed by flow cytometry 131. Still others used 68Ga-DOTA-RGD to image plaques ex vivo to measure the degree of inflammation and the vulnerability of atherosclerotic plaques 132. Autoradiography showed significantly higher uptake of 68Ga-DOTA-RGD in plaques as compared to the healthy vessel wall and adventitia. However, there was no significant difference in aorta tracer uptake compared to control mice, which was probably due to the tissues around the healthy vessel wall, and the overall low uptake of the tracer in therosclerotic plaques. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine the validity of RGD peptide tracers to image arterial plaques in human.

2.4.2 VAP-1

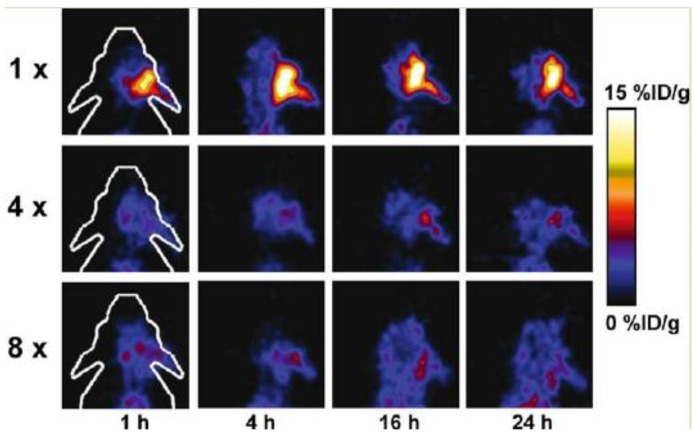

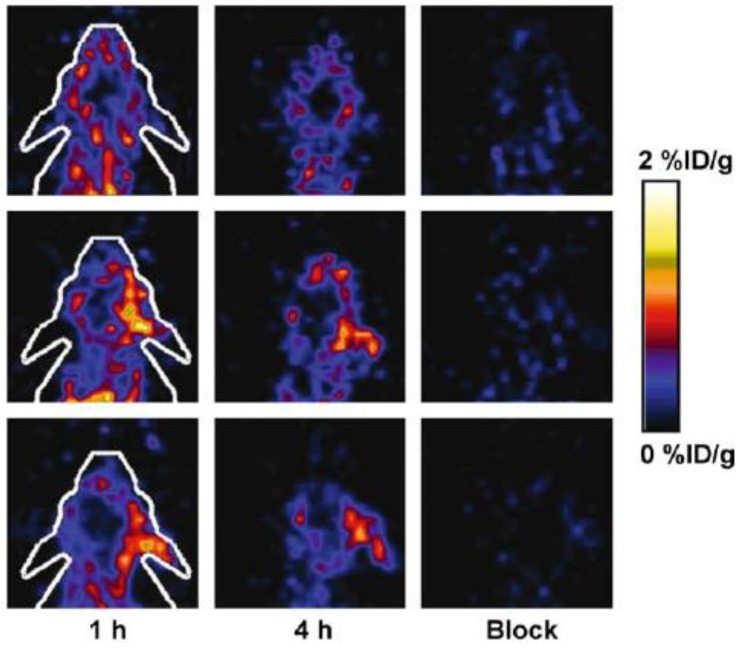

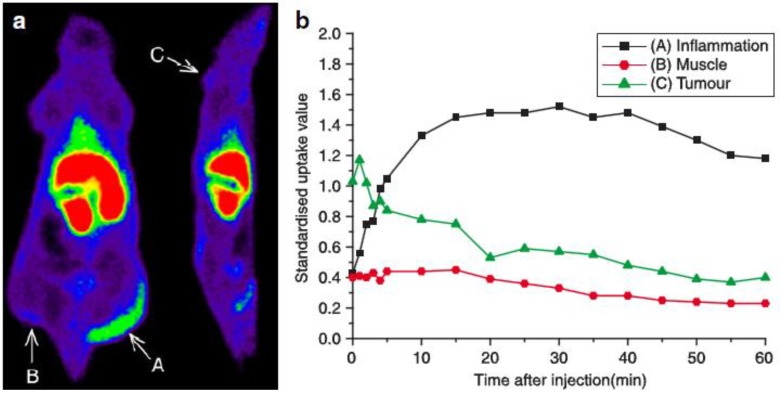

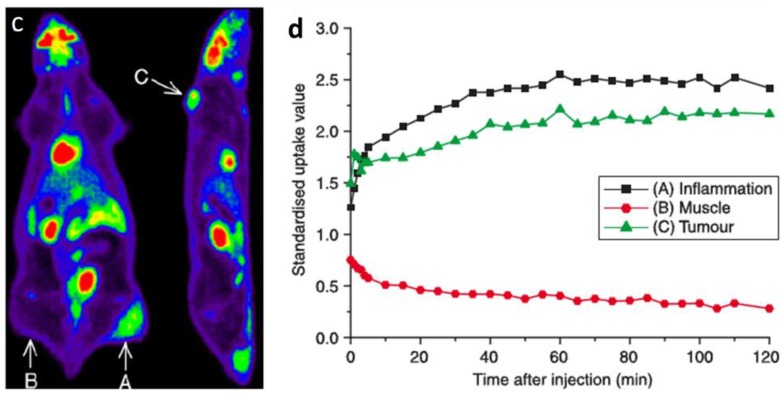

Vascular adhesion protein 1 (VAP-1) is an endothelial adhesion protein stored in intracellular granules within endothelial cells. The expression of VAP-1 is quite low on the endothelial surface of normal tissues. Upon stimulation, VAP-1 is translocated onto the luminal surface of endothelial cells at sites of inflammation, causing the migration of leukocytes, especially CD8+ T lymphocytes, from the blood into the non-lymphoid inflammatory foci 133. VAP-1 is, therefore, a promising target for both anti-inflammation therapy and molecular imaging of inflammation. A number of studies using radiolabeled synthetic peptides have been attempted to image VAP-1 expression 24, 134-137. These ligands were either designed by molecular modeling based on the crystal structure of human VAP-1 or selected from phage display libraries and were labeled with 68Ga to form 68Ga-DOTA-Siglec-9 136, 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 24, 137, 68Ga-DOTAVAP-PEG-P1 134, or 68Ga-DOTAVAP-PEG-P2 135. These VAP-1 targeted PET tracers have been tested in sterile/infectious inflammatory and tumor-bearing animal models. In one study, 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 was compared with 18F-FDG to differentiate turpentine oil induced muscular inflammation and human BxPC3 xenografted tumors 24. PET with 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 showed intensive inflammatory foci uptake, concordant with the high VAP-1 expression examined by ex vivo studies. However, 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 had very low uptake in BxPC3 tumors (Figure 7), suggesting the ability of this tracer to tell inflammation from tumor. In contrast, FDG showed high uptake in both inflammation foci and tumors, unable to discriminate one from the other. 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 has also been used to image osteomyelitic bones 138 and differentiate osteomyelitic bones from inflammation in healing bones 137. In the differentiation study in particular, rat model of healing cortical bone defects (representing the sterile inflammation process of bone healing) and bone osteomyelitis were compared using 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 PET. At day 7 after operation, the sterile inflammation in healing cortical bone defect showed a significant decrease in tracer uptake, while osteomyelitis uptake of 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 remained high. This study showed the potential of 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 to differentiate bacterial infection from nonbacterial inflammation.

Figure 7.

68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 (a, b) and 18F-FDG (c, d) PET imaging of mice with BxPC-3 tumor inoculation and turpentine induced inflammation. (a) 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 uptake is clearly seen at the site of inflammation (arrow A) but not in the muscle (arrow B) or the tumor (arrow C). (b) Time-activity curve (TAC) of 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1 uptake in the inflammation site, muscle and tumor. (c) 18F-FDG uptake is clearly seen at the site of inflammation (arrow A) as well as the tumor (arrow C). (d) TAC of 18F-FDG uptake in the inflammation site, muscle, and tumor (Autio, 2010 24).

2.4.3 VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 is one member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of endothelial adhesion molecules. It plays an important role in all stages of atherosclerotic plaque 139, 140. It is expressed on activated endothelium and can induce the adhesion of macrophages at the early stage of plaque formation. A linear peptide affinity ligand, VHPKQHR, was identified using in vivo phage display in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. This sequence is homologous to very late antigen-4, a known ligand for VCAM-1 141. A multivalent PET imaging agent (18F-4V) has been developed based on this peptide sequence and applied to evaluate expression of VCAM-1. In (ApoE)-/- mice with atherosclerotic plaques located in the aortic root, PET images showed strong focal signal in the aortic root. Consistent with the imaging results, a high level of VCAM-1 mRNA was confirmed in the aortic sections. Also in this study, PET imaging using 18F-4V was used for other cardiovascular disorders, such as myocardial infarction and transplant rejection with possible VCAM-1-mediated monocyte recruitment. Images showed 18F-4V uptake in the infarcted left ventricular wall in the MI model mice and in the cardiac allograft models; the inflamed myocardium also showed high tracer uptake after transplanted cardiac allografts underwent rejection.

2.4.4 Vessel permeability

In normal conditions, vascular integrity is important in maintaining the homeostasis of the internal environment. Upon stimulation by various stimuli, as in acute inflammatory process, local vessel permeability is remarkably increased due to the release of many cytokines, chemokines, and leukotrienes by resident inflammatory cells and endothelial cells. This is important for self-defense by allowing immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages to infiltrate into inflammatory foci. Therefore, either in sterile or infectious inflammation, increased vessel permeability could be utilized as a “biomarker” for inflammation imaging. Gallium ion has traditionally been used to image inflammation with gamma cameras. The accumulation of 67Ga in inflammation foci can be explained either by binding to transferrin then diffusing into sites of inflammation via increased vascular permeability, or by binding to local lactoferrin produced by leucocytes, or siderophores produced by infecting micro-organisms 142. However, the disadvantages of 67Ga limit its wide-spread applicationz, such as high cost, long half-life (3.26 d) and poor imaging quality due to its wide spectrum of gamma rays emitted. 68Ga has the same chemical characteristics as 67Ga, but with easier production procedure, short half-life (68 min) and positron-emitting property, therefore making it a better alternative for inflammation PET imaging. In fact, 68Ga is now in clinical trials for imaging infectious bone 143 and non-infectious bone defect healing process 144. In these studies, infectious inflammatory bones showed high uptake of 68Ga or 68Ga-citrate, while animal models of bone defect without infection did not show very significant local 68Ga uptake. Although local vessel permeability is increased under both conditions, the authors suggested that this might due to the binding of 68Ga to the siderophores produced by micro-organisms which did not exist in the sterile inflammation. Therefore infectious bone had higher 68Ga uptake than the non-infectious bone defect. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that 68Ga PET will be more valuable than conventional 18F-FDG imaging in lowering the odds of false-positive findings in post-surgical and post-traumatic bone healing 144.

68Ga has also been used to image atherosclerotic inflammation in animal models 12. Intensive atherosclerosis uptake of 68Ga was observed in this study. The reasons for the accumulation in inflamed plaques, as the authors claimed, might be due to locally increased vessel permeability, competitive binding to the Ca2+ and Mg2+ in calcified areas or binding to the circulating transferrin and to the transferrin receptors at the site of atherosclerotic artery binding sites.

3. Evaluation of inflammatory diseases using PET

An increasing number of diseases have recently been found to be inflammation related, such as atherosclerosis 145, neurodegenerative disorders 146, and malignant tumors 147. Non-invasive PET imaging has the potential to help figure out the mechanism of inflammatory disease processes, discover potential targeted therapeutics, and establish new diagnostic standards.

3.1 Cardiovascular inflammation: focusing on atherosclerosis

As an inflammatory disease, the onset, progression, and destabilization of atherosclerosis involves multi-participants within the immune response, including activation of endothelial cells, infiltration of various cells, release of inflammatory cytokines, and macrophage apoptosis. Due to the high morbidity and mortality rates of atherosclerosis, early detection and full characterization of atherosclerosis is of extreme necessity. So far, 18F-FDG is the most extensively used probe for atherosclerosis imaging 9, 13, 148, 149 (Table 1). Many preclinical and clinical studies have established the correlation not only between local FDG uptake and plaque macrophage density but also between high metabolic activities of macrophages within plaques and cardiovascular risk factors. However, the partial volume effect, high physiology uptake of 18F-FDG in the myocardium or brain, and motion artifacts from cardiac movement all make visualization of small atherosclerotic plaques in these areas rather cumbersome. In fact, besides high glucose metabolism, many inflammation biomarkers have been evaluated for atherosclerosis PET imaging, including the aforementioned choline metabolism, TSPO, SSTR, VAP-1, MMPs, integrin receptors, and VCAM-1. Some of the PET probes, such as radio-labeled PK11195 (binding to TPSO), choline (targeting to the phosphatidylcholine catabolism of macrophages and monocytes), TATE/TOC (binding to SSTR), are superior to conventional 18F-FDG in their low myocardium biodistribution. Consequently, the images achieved high target-to-background ratio, facilitating the analysis of small coronary plaques. In addition, PET imaging of MMPs could assess the plaque-promoting activity of macrophages rather than their density in vulnerable plaques, and integrin receptor targeted imaging could detect CD68-positive macrophages in the vulnerable plaques 120. PET imaging of these biomarkers, together with other conventional angiography, opens up the opportunity for better diagnosis and prognosis of atherosclerosis.

3.2 Neuroinflammation

Recently, accumulating evidences have revealed that many chronic neuroinflammatory diseases are caused by activated microglia in the CNS 150. As the resident immune cells in the CNS, microglial cells are activated in the acute neuroinflammation phase and protect brain tissue from further injury through migration, proliferation, and production of neurotoxic factors. However in chronic neuroinflammation, microglia activation causes long-term cerebral damage by inducing autoimmune reaction. The activation of microglia is observed in various CNS diseases such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease 151. Several known neuroinflammation related targets include TSPO, CB2R, and COX-2. Among them, TSPO is the most popular target for PET imaging which has already undergone clinical application, while CB2R and COX-2 are still in the preliminary stage as imaging targets (Table 3).

Table 3.

CNS diseases evaluated by PET targeting on inflammatory biomarkers.

| Disease Type | Imaging target | Clinical / Preclinical | Imaging modality | Tracer | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traumatic brain injury (TBI) | TSPO | Preclinical, rat | Animal PET | 18F-DAA1106, 11C-verapamil, 11C-PK11195 | Yu, 2010 160 Folkersma, 2011 161 |

|

| TSPO | Clinical | PET, MRI | 11C-PK11195 | Ramlackhansingh, 2011 158 | ||

| Cerebral ischemia | TSPO | Preclinical, rat | PET, MRI |

18F-DPA-714 18F-FEAC 18F-FEDAC |

Martin, 2010 162 Yui, 2010 52 |

|

| TSPO | Clinical | PET, MRI |

11C-vinpocetine 11C-Pk11195 |

Gulyás, 2012 54 Thiel, 2010 157 |

||

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) | TSPO | Preclinical, rat | Animal PET | 11C-DAC | Xie, 2012 163 | |

| TSPO | Clinical | PET, MRI | 11C-PBR28 | Oh, 2011 45 | ||

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | TSPO | Preclinical, mouse | Animal PET |

11C-AC-5216 18F-FEDAA1106 |

Maeda, 2011 53 | |

| TSPO | Clinical | PET, MRI |

11C-vinpocetine 11C-PK11195 |

Gulyás, 2011 153 Yokokura, 2011 152 |

||

| CB2R | Preclinical, mouse | animal PET | 11C-A-836339 | Horti, 2010 76 | ||

| Parkinson's Disease (PD) | TSPO | Clinical | PET, MRI | 11C-PK11195 | Gerhard, 2006 164 Edison, 2012 156 |

|

| Huntington's disease (HD) |

TSPO | Clinical | PET, MRI |

11C-PK11195 11C-raclopride |

Politis, 2011 165 | |

| Epilepsy | TSPO | Clinical (one case) | PET, MRI | 11C-PK11195 | Dedeurwaerdere, 2012 51 | |

| Brain inflammation | COX | Preclinical, rat | Animal PET |

11C-ketoprofen methyl ester 11C-rofecoxib |

Shukuri, 2011 92 de Vries, 2008 91 |

|

As for the clinical translation, although some limitations do exist, TPSO targeted PET imaging of neuroinflammatory disease has provided some helpful information in disease diagnosis and prognosis. For example, in AD patients, TPSO PET enabled the discovery of the relationship between Aβ accumulation and microglia activation during disease process 152 and can detect an age related increase in microglia activation in normal human brains and in AD progression 153. However, based on current research, no definite conclusion can be drawn between the results of amyloid plaque imaging using 11C-PIB and inflammation imaging targeting TPSO 53, 154, 155. Microglia activation was found to be a potential driving force in the development of Parkinson's disease with dementia (PDD) and could be detected via TPSO PET at the early phase in PD patients 156. In stroke, TSPO PET imaging was able to find the temporal dynamics of microglia activation in patients, which was correlated with clinical outcome 157. In traumatic brain injury (TBI), the imaging of microglia via TSPO was found to be present up to 17 years after TBI, indicating the possible benefit of long-term interventions for post-TBI patients 158. However, some discrepancies exist among different studies, and this might be due to the lack of standardized analysis of imaging results and certain limitations of radiotracer for PET neuroinflammation imaging, such as low binding affinity and low target-to-background ratio 159. Therefore, the development of new tracers with better imaging properties and the improvement in quantitative data analysis should be of great importance for PET guided neuroinflammation imaging in the future.

3.3 Tumor related inflammation

Inflammation contributes to a tumor's immune escape phenomenon, creating a proper environment for neoplastic onset and continued growth. In fact, inflammatory cells and mediators are present in the microenvironment of virtually all tumors that are not epidemiologically related to inflammation 166. Recently, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) or tumor-infiltrating macrophages (TIMs) have been intensively investigated as a target for imaging and therapy 167. TAMs enhance tumor cell migration and invasion through their secretion of chemotactic and chemokinetic factors 168. Depletion of TAMs improved the effect of chemotherapy in some cancer models 169. Therefore, TAMs targeted imaging would have great value providing guidance for macrophage targeted cancer therapy and patient stratification for personalized treatment. Various molecular imaging techniques have been applied to study TAMs, including MRI 170, optical imaging 171, PET 172, SPECT 173, and hybrid molecular imaging modality 174, 175, in which most of the imaging agents are nanomaterial based. Studies performed by Zheng et al. 176 using 18F-DPA-714, a TSPO specific tracer, proved that TSPO was positive in both breast cancer cells and TAMs. These results supported that TSPO expression inside tumors came from mixed cell populations, leading the way for future development of imaging and therapeutic ligands targeting TSPO on macrophages. In another study, Locke et al. 82 performed PET imaging of TAMs using mannose coated 64Cu liposomes and showed that the imaging agent could accumulate in TAMs in a pulmonary adenocarcinoma foci in a mouse model.

Because FDG could also accumulate in non-neoplastic cells that infiltrate neoplasms 167, without histological validation, it remains unclear what percentage of FDG accumulation is caused by peritumoral and intratumoral inflammation. Hence, it is a consensus in clinical setting that cancer therapy evaluation using FDG PET should be carefully conducted, especially when effective treatment can lead to massive inflammation. Consequently, many studies focused on developing more tumor cell specific PET tracers beyond FDG. Some tumor proliferation markers such as lipid precursors, amino acids, nucleosides, and receptor ligands have been tested for this purpose. For example, 11C-choline was developed to evaluate intracellular choline kinase activity, 11C-methionine (MET) to image amino acid transporter, and 18F-fluorothymidine (FLT) to determine thymidine kinase 1 activity 177. In a preclinical study, Lee et al. 178 examined 18F-FET and 18F-FLT along with 18F-FDG to differentiate tumor from inflammation. They found 18F-FET and 18F-FLT selectively localized in tumor tissues but not inflammation. Similar results were also reported elsewhere 179, 180. Clinical studies also demonstrated that 18F-FLT is significantly better than 18F-FDG as a measure of tumor proliferation and more specific than 18F-FDG PET for cancer staging. However, tumor uptake of 18F-FLT is much less than 18F-FDG, resulting in a significantly lower sensitivity for 18F-FLT PET than for 18F-FDG PET 181.

Several inflammation biomarkers may be promising in differentiating tumor from inflammation including VAP-1 and integrins. As mentioned before, the VAP-1 targeted peptidic tracer, 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1, showed accumulation in inflammation foci but not as much in tumors, making it a potential inflammation-targeting tracer 24. 18F-FPPRGD2, an integrin receptor targeting probe, was found to be superior to 18F-FDG in monitoring tumor response to Abraxane treatment, possibly due to less uptake in TAM 182. Admittedly, it is very challenging to develop an imaging probe which can separate tumor and inflammation completely since inflammation is an inherent tumor microenvironment.

4. Conclusion and perspectives

The process of inflammation is involved, either directly or indirectly in various human diseases, including stroke, Alzheimer's disease, atherosclerosis, autoimmune diseases, and even malignant disorders. Therefore, information extracted from molecular imaging of inflammation in these disorders is definitely helpful in disease diagnosis, and prognosis, therapy response monitoring, and shedding light on understanding the nature of disease processes. So far, many inflammation related biomarkers have been identified and investigated as imaging or therapy targets, including inflammatory cell metabolism, membrane markers, cytokines, and vascular changes during inflammation. After intensive preclinical studies, some of these targets have been tested in humans. For example, FDG PET has been used to evaluate inflammation in atherosclerosis plaques, and many new tracers in proof-of-concept clinical studies showed promise in discerning inflammation from background. To evaluate neuroinflammation in AD, PD, and ischemic neural diseases, PET imaging of TSPO expression on activated microglia showed very promising results. For tumor related inflammation imaging, tumor-associated macrophages become widely explored targets. In the never-ending debate on differentiating tumor from inflammation, a variety of PET probes have been studied. However, very few of them are considered to be inflammation specific. With better understanding of the inflammatory reaction in each disease type, more sensitive and specific biomarkers will be identified, and potential new imaging probes may be developed to target these biomarkers. Moreover, multiplexed imaging with tracers targeting different biomarkers and multimodal imaging by incorporating PET with other imaging modalities will also contribute to improved visualization and quantification of the inflammatory diseases.

Table 2.

PET imaging targets for inflammation and corresponding PET probes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:851–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. doi:10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rock KL, Latz E, Ontiveros F, Kono H. The sterile inflammatory response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:321–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101311. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen GY, Nuñez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–37. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. doi:10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnamoorthy S, Honn KV. Inflammation and disease progression. Cancer Met Rev. 2006;25:481–91. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9016-0. doi:10.1007/s10555-006-9016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankoff DA. A definition of molecular imaging. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Imaging in the era of molecular oncology. Nature. 2008;452:580–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06917. doi:10.1038/nature06917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emelianov SY, Li PC, O'Donnell M. Photoacoustics for molecular imaging and therapy. Phys Today. 2009;62:34–9. doi: 10.1063/1.3141939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saraste A, Nekolla SG, Schwaiger M. Cardiovascular molecular imaging: an overview. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:643–52. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp209. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum D, Millon A, Fayad ZA. Molecular imaging in atherosclerosis: FDG PET. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14:429–37. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0264-x. doi:10.1007/s11883-012-0264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhari AJ, Bowen SL, Burkett GW, Packard NJ, Godinez F, Joshi AA. et al. High-resolution 18F-FDG PET with MRI for monitoring response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1047.. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1364-x. doi:10.1007/s00259-009-1364-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Samnick S, Lapa C, Israel I, Buck AK, Kreissl MC. et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT for the detection of inflammation of large arteries: correlation with 18F-FDG, calcium burden and risk factors. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2:52.. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-52. doi:10.1186/2191-219X-2-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silvola JM, Laitinen I, Sipila HJ, Laine VJ, Leppanen P, Yla-Herttuala S. et al. Uptake of 68Gallium in atherosclerotic plaques in LDLR-/-ApoB100/100 mice. EJNMMI Res. 2011;1:14.. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-14. doi:10.1186/2191-219X-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yarasheski KE, Laciny E, Overton ET, Reeds DN, Harrod M, Baldwin S. et al. 18FDG PET-CT imaging detects arterial inflammation and early atherosclerosis in HIV-infected adults with cardiovascular disease risk factors. J Inflamm (Lond) 2012;9:26.. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-9-26. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bissonnette R, Tardif JC, Harel F, Pressacco J, Bolduc C, Guertin MC. Effects of the TNF alpha antagonist Adalimumab on arterial inflammation assessed by positron emission tomography in patients with psoriasis: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:83–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.975730. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.975730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maki-Petaja KM, Elkhawad M, Cheriyan J, Joshi FR, Ostor AJ, Hall FC. et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy reduces aortic inflammation and stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2012;126:2473–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120410. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tegler G, Ericson K, Sorensen J, Bjorck M, Wanhainen A. Inflammation in the walls of asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms is not associated with increased metabolic activity detectable by 18-fluorodeoxglucose positron-emission tomography. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.024. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tezuka D, Haraguchi G, Ishihara T, Ohigashi H, Inagaki H, Suzuki J. et al. Role of FDG PET-CT in Takayasu arteritis: sensitive detection of recurrences. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:422–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.013. doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarda-Mantel L, Alsac JM, Boisgard R, Hervatin F, Montravers F, Tavitian B. et al. Comparison of 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose, 18F-fluoro-methyl-choline, and 18F-DPA714 for positron-emission tomography imaging of leukocyte accumulation in the aortic wall of experimental abdominal aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:765–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.069. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim TN, Kim S, Yang SJ, Yoo HJ, Seo JA, Kim SG. et al. Vascular inflammation in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes: analysis with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:142–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.888909. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.888909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dweck MR, Jones C, Joshi NV, Fletcher AM, Richardson H, White A. et al. Assessment of valvular calcification and inflammation by positron emission tomography in patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2012;125:76–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051052. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irmler IM, Opfermann T, Gebhardt P, Gajda M, Brauer R, Saluz HP. et al. In vivo molecular imaging of experimental joint inflammation by combined 18F-FDG positron emission tomography and computed tomography. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R203.. doi: 10.1186/ar3176. doi:10.1186/ar3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamashita H, Kubota K, Takahashi Y, Minamimoto R, Morooka M, Kaneko H. et al. Similarities and differences in fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography findings in spondyloarthropathy, polymyalgia rheumatica and rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLarty K, Moran MD, Scollard DA, Chan C, Sabha N, Mukherjee J. et al. Comparisons of [18F]-1-deoxy-1-fluoro-scyllo-inositol with [18F]-FDG for PET imaging of inflammation, breast and brain cancer xenografts in athymic mice. Nucl Med Biol. 2011;38:953–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.017. doi:10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Autio A, Ujula T, Luoto P, Salomaki S, Jalkanen S, Roivainen A. PET imaging of inflammation and adenocarcinoma xenografts using vascular adhesion protein 1 targeting peptide 68Ga-DOTAVAP-P1: comparison with 18F-FDG. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1918–25. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1497-y. doi:10.1007/s00259-010-1497-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown TL, Spencer HJ, Beenken KE, Alpe TL, Bartel TB, Bellamy W. et al. Evaluation of dynamic [18F]-FDG-PET imaging for the detection of acute post-surgical bone infection. PloS One. 2012;7:e41863.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041863. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee WW, Marinelli B, van der Laan AM, Sena BF, Gorbatov R, Leuschner F. et al. PET/MRI of inflammation in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.066. doi:S0735-1097(11)04600-6 [pii]10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenbaum SJ, Lind T, Antoch G, Bockisch A. False-positive FDG PET uptake--the role of PET/CT. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1054–65. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0088-y. doi:10.1007/s00330-005-0088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buscombe J, Signore A. FDG-PET in infectious and inflammatory disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1571–3. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1360-5. doi:10.1007/s00259-003-1360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu S, Zhuang H, Torigian DA, Rosenbaum J, Chen W, Alavi A. Functional imaging of inflammatory diseases using nuclear medicine techniques. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39:124–45. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.10.006. doi:10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mertens K, Slaets D, Lambert B, Acou M, De Vos F, Goethals I. PET with 18F-labelled choline-based tracers for tumour imaging: a review of the literature. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:2188–93. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1496-z. doi:10.1007/s00259-010-1496-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jadvar H. Can Choline PET Tackle the challenge of imaging prostate cancer? Theranostics. 2012;2:331–2. doi: 10.7150/thno.4288. doi:10.7150/thno.4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarzenbock S, Souvatzoglou M, Krause BJ. Choline PET and PET/CT in primary diagnosis and staging of prostate cancer. Theranostics. 2012;2:318–30. doi: 10.7150/thno.4008. doi:10.7150/thno.4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picchio M, Castellucci P. Clinical indications of 11C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical relapse. Theranostics. 2012;2:313–7. doi: 10.7150/thno.4007. doi:10.7150/thno.4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matter CM, Wyss MT, Meier P, Spath N, von Lukowicz T, Lohmann C. et al. 18F-choline images murine atherosclerotic plaques ex vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:584–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000200106.34016.18. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000200106.34016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laitinen IE, Luoto P, Nagren K, Marjamaki PM, Silvola JM, Hellberg S. et al. Uptake of 11C-choline in mouse atherosclerotic plaques. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:798–802. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.071704. doi:10.2967/jnumed.109.071704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bucerius J, Schmaljohann J, Bohm I, Palmedo H, Guhlke S, Tiemann K. et al. Feasibility of 18F-fluoromethylcholine PET/CT for imaging of vessel wall alterations in humans--first results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:815–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0685-x. doi:10.1007/s00259-007-0685-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spaeth N, Wyss MT, Weber B, Scheidegger S, Lutz A, Verwey J. et al. Uptake of 18F-fluorocholine, 18F-fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine, and 18F-FDG in acute cerebral radiation injury in the rat: implications for separation of radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1931–8. doi:45/11/1931 [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roivainen A, Yli-Kerttula T. Whole-body distribution of 11C-choline and uptake in knee synovitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1372–3. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0184-5. doi:10.1007/s00259-006-0184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bird JL, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Davies JR, Rudd JH, Probst KC, Figg N. et al. Evaluation of translocator protein quantification as a tool for characterising macrophage burden in human carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:388–91. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.047. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaemperli O, Shalhoub J, Owen DR, Lamare F, Johansson S, Fouladi N. et al. Imaging intraplaque inflammation in carotid atherosclerosis with 11C-PK11195 positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1902–10. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr367. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatori A, Yui J, Yamasaki T, Xie L, Kumata K, Fujinaga M. et al. PET imaging of lung inflammation with [18F]FEDAC, a radioligand for translocator protein (18 kDa) PloS One. 2012;7:e45065.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045065. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045065PONE-D-12-07784 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hannestad J, Gallezot JD, Schafbauer T, Lim K, Kloczynski T, Morris ED. et al. Endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation activates microglia: [11C]PBR28 positron emission tomography in nonhuman primates. NeuroImage. 2012;63:232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.055. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roeda D, Kuhnast B, Damont A, Dollé F. Synthesis of fluorine-18-labelled TSPO ligands for imaging neuroinflammation with Positron Emission Tomography. J Fluor Chem. 2012;134:107–14. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2011.03.020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ching AS, Kuhnast B, Damont A, Roeda D, Tavitian B, Dolle F. Current paradigm of the 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) as a molecular target for PET imaging in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Insights Imaging. 2012;3:111–9. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0128-x. doi:10.1007/s13244-011-0128-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh U, Fujita M, Ikonomidou VN, Evangelou IE, Matsuura E, Harberts E. et al. Translocator protein PET imaging for glial activation in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:354–61. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9243-6. doi:10.1007/s11481-010-9243-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papadopoulos V, Lecanu L. Translocator protein (18 kDa) TSPO: an emerging therapeutic target in neurotrauma. Exp Neurol. 2009;219:53–7. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.016. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gulyás B, Makkai B, Kása P, Gulya K, Bakota L, Várszegi S. et al. A comparative autoradiography study in post mortem whole hemisphere human brain slices taken from Alzheimer patients and age-matched controls using two radiolabelled DAA1106 analogues with high affinity to the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) system. Neurochem Int. 2009;54:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.10.001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takashima-Hirano M, Shukuri M, Takashima T, Goto M, Wada Y, Watanabe Y. et al. General method for the 11C-labeling of 2-arylpropionic acids and their esters: construction of a PET tracer library for a study of biological events involved in COXs expression. Chemistry. 2010;16:4250–8. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903044. doi:10.1002/chem.200903044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner S, Breyholz HJ, Holtke C, Faust A, Schober O, Schafers M. et al. A new 18F-labelled derivative of the MMP inhibitor CGS 27023A for PET: radiosynthesis and initial small-animal PET studies. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67:606–10. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.12.009. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2008.12.009S0969-8043(08)00554-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devinsky O, Vezzani A, Najjar S, De Lanerolle NC, Rogawski MA. Glia and epilepsy: excitability and inflammation. Trends Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.008. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dedeurwaerdere S, Callaghan PD, Pham T, Rahardjo GL, Amhaoul H, Berghofer P. et al. PET imaging of brain inflammation during early epileptogenesis in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2:60.. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-60. doi:10.1186/2191-219X-2-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yui J, Maeda J, Kumata K, Kawamura K, Yanamoto K, Hatori A. et al. 18F-FEAC and 18F-FEDAC: PET of the monkey brain and imaging of translocator protein (18 kDa) in the infarcted rat brain. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1301–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.072223. doi:jnumed.109.072223 [pii]10.2967/jnumed.109.072223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maeda J, Zhang MR, Okauchi T, Ji B, Ono M, Hattori S. et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic imaging of glial responses to amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4720–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3076-10.2011. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3076-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gulyas B, Toth M, Schain M, Airaksinen A, Vas A, Kostulas K. et al. Evolution of microglial activation in ischaemic core and peri-infarct regions after stroke: a PET study with the TSPO molecular imaging biomarker [11C]vinpocetine. J Neurol Sci. 2012;320:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.06.026. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pugliese F, Gaemperli O, Kinderlerer AR, Lamare F, Shalhoub J, Davies AH. et al. Imaging of vascular inflammation with [11C]-PK11195 and positron emission tomography/computed tomography angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:653–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.063. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamare F, Hinz R, Gaemperli O, Pugliese F, Mason JC, Spinks T. et al. Detection and quantification of large-vessel inflammation with 11C-(R)-PK11195 PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:33–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079038. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.079038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hardwick MJ, Chen MK, Baidoo K, Pomper MG, Guilarte TR. In vivo imaging of peripheral benzodiazepine receptors in mouse lungs: a biomarker of inflammation. Mol Imaging. 2005;4:432–8. doi: 10.2310/7290.2005.05133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie L, Yui J, Hatori A, Yamasaki T, Kumata K, Wakizaka H. et al. Translocator protein (18kDa), a potential molecular imaging biomarker for non-invasively distinguishing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1076–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.002S0168-8278(12)00529-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maecke HR, Reubi JC. Somatostatin receptors as targets for nuclear medicine imaging and radionuclide treatment. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:841–4. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.084236. doi:jnumed.110.084236 [pii]10.2967/jnumed.110.084236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Ruiter ED, Kwekkeboom DJ, Mooi WJ, Knegt P, Tanghe HL, van Hagen PM. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the fossa pterygopalatina: diagnosis and treatment. Neth J Med. 2000;56:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(99)00102-3. doi:S0300297799001023 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwekkeboom DJ, van Hagen PM, Krenning EP. Refractory immune-mediated and haematological diseases: candidates for peptide receptor radiotherapy? Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143(Suppl 1):S53–6. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.143s053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamphuis LSJ, Kwekkeboom DJ, van Laar JAM, van Daele PLA, Baarsma GS, van Hagen PM. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in sarcoidosis. J Transl Med. 2011;9:P9. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dalm VA, van Hagen PM, van Koetsveld PM, Achilefu S, Houtsmuller AB, Pols DH. et al. Expression of somatostatin, cortistatin, and somatostatin receptors in human monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E344–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00048.2003. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00048.200300048.2003 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rominger A, Saam T, Vogl E, Ubleis C, la Fougere C, Forster S. et al. In vivo imaging of macrophage activity in the coronary arteries using 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT: correlation with coronary calcium burden and risk factors. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:193–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070672. doi:10.2967/jnumed.109.070672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ambrosini V, Zompatori M, De Luca F, Antonia D, Allegri V, Nanni C. et al. 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT allows somatostatin receptor imaging in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: preliminary results. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1950–5. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079962. doi:jnumed.110.079962 [pii]10.2967/jnumed.110.079962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jindal T, Kumar A, Dutta R, Kumar R. Combination of 18F-FDG and 68Ga-DOTATOC PET-CT to differentiate endobronchial carcinoids and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. J Postgrad Med. 2009;55:272–4. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.58932. doi:jpgm_2009_55_4_272_58932 [pii]10.4103/0022-3859.58932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oberg K. Molecular Imaging Radiotherapy: Theranostics for Personalized Patient Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs) Theranostics. 2012;2:448–58. doi: 10.7150/thno.3931. doi:10.7150/thno.3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garske U, Sandstrom M, Johansson S, Granberg D, Lundqvist H, Lubberink M. et al. Lessons on tumour response: Imaging during therapy with 177Lu-DOTA-octreotate. A case report on a patient with a large volume of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. Theranostics. 2012;2:459–71. doi: 10.7150/thno.3594. doi:10.7150/thno.3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Delpassand ES, Samarghandi A, Mourtada JS, Zamanian S, Espenan GD, Sharif R. et al. Long-term survival, toxicity profile, and role of F-18 FDG PET/CT scan in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors following peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with high activity In-111 Pentetreotide. Theranostics. 2012;2:472–80. doi: 10.7150/thno.3739. doi:10.7150/thno.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pettinato C, Sarnelli A, Di Donna M, Civollani S, Nanni C, Montini G. et al. 68Ga-DOTANOC: biodistribution and dosimetry in patients affected by neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:72–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0587-y. doi:10.1007/s00259-007-0587-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hofmann M, Maecke H, Borner R, Weckesser E, Schoffski P, Oei L. et al. Biokinetics and imaging with the somatostatin receptor PET radioligand 68Ga-DOTATOC: preliminary data. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1751–7. doi: 10.1007/s002590100639. doi:10.1007/s002590100639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cabral GA, Raborn ES, Griffin L, Dennis J, Marciano-Cabral F. CB2 receptors in the brain: role in central immune function. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:240–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707584. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evens N, Bormans GM. Non-invasive imaging of the type 2 cannabinoid receptor, focus on positron emission tomography. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:1527–43. doi: 10.2174/156802610793176819. doi:BSP/ CTMC /E-Pub/-0096-10-16 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hostetler ED, Terry GE, Donald Burns H. An improved synthesis of substituted [11C]toluenes via Suzuki coupling with [11C]methyl iodide. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2005;48:629–34. doi:10.1002/jlcr.953. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Evens N, Vandeputte C, Muccioli GG, Lambert DM, Baekelandt V, Verbruggen AM. et al. Synthesis, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of fluorine-18 labelled FE-GW405833 as a PET tracer for type 2 cannabinoid receptor imaging. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:4499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.033. doi:S0968-0896(11)00461-5 [pii]10.1016/j.bmc.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horti AG, Gao Y, Ravert HT, Finley P, Valentine H, Wong DF. et al. Synthesis and biodistribution of [11C]A-836339, a new potential radioligand for PET imaging of cannabinoid type 2 receptors (CB2) Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:5202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.05.058. doi:S0968-0896(10)00489-X [pii]10.1016/j.bmc.2010.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evens N, Vandeputte C, Coolen C, Janssen P, Sciot R, Baekelandt V. et al. Preclinical evaluation of [11C]NE40, a type 2 cannabinoid receptor PET tracer. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:389–99. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.09.005. doi:S0969-8051(11)00218-6 [pii]10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vandeputte C, Evens N, Toelen J, Deroose CM, Bosier B, Ibrahimi A. et al. A PET brain reporter gene system based on type 2 cannabinoid receptors. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1102–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.084426. doi:jnumed.110.084426 [pii]10.2967/jnumed.110.084426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stasiuk GJ, Smith H, Wylezinska-Arridge M, Tremoleda JL, Trigg W, Luthra SK. et al. Gd3+ cFLFLFK conjugate for MRI: a targeted contrast agent for FPR1 in inflammation. Chem Commun (Camb) 2013;49:564–6. doi: 10.1039/c2cc37460a. doi:10.1039/c2cc37460a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xiao L, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Yang M, Pu L, Pan D. Synthesis of the Cyanine 7 labeled neutrophil-specific agents for noninvasive near infrared fluorescence imaging. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:3515–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.136. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang Y, Xiao L, Chordia MD, Locke LW, Williams MB, Berr SS. et al. Neutrophil targeting heterobivalent SPECT imaging probe: cFLFLF-PEG-TKPPR-99mTc. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:1788–93. doi: 10.1021/bc100063a. doi:10.1021/bc100063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Locke LW, Chordia MD, Zhang Y, Kundu B, Kennedy D, Landseadel J. et al. A novel neutrophil-specific PET imaging agent: cFLFLFK-PEG-64Cu. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:790–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056127. doi:10.2967/jnumed.108.056127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang Y, Kundu B, Fairchild KD, Locke L, Berr SS, Linden J. et al. Synthesis of novel neutrophil-specific imaging agents for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:6876–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.013. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tran L, Huitema AD, van Rijswijk MH, Dinant HJ, Baars JW, Beijnen JH. et al. CD20 antigen imaging with 124I-rituximab PET/CT in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Hum Antibodies. 2011;20:29–35. doi: 10.3233/hab20110239. doi:10.3233/HAB2011023910.3233/HAB-2011-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hawkey CJ. COX-2 inhibitors. Lancet. 1999;353:307–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)12154-2. doi:S0140673698121542 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Katori M, Majima M. Cyclooxygenase-2: its rich diversity of roles and possible application of its selective inhibitors. Inflamm Res. 2000;49:367–92. doi: 10.1007/s000110050605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Minghetti L. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in inflammatory and degenerative brain diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:901–10. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Vries EF, van Waarde A, Buursma AR, Vaalburg W. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of 18F-desbromo-DuP-697 as a PET tracer for cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1700–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McCarthy TJ, Sheriff AU, Graneto MJ, Talley JJ, Welch MJ. Radiosynthesis, in vitro validation, and in vivo evaluation of 18F-labeled COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:117–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Prabhakaran J, Majo VJ, Simpson NR, Van Heertum RL, Mann JJ, Kumar JSD. Synthesis of [11C]celecoxib: a potential PET probe for imaging COX-2 expression. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2005;48:887–95. doi:10.1002/jlcr.1002. [Google Scholar]

- 91.de Vries EFJ, Doorduin J, Dierckx RA, van Waarde A. Evaluation of [11C]rofecoxib as PET tracer for cyclooxygenase 2 overexpression in rat models of inflammation. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.07.015. doi:10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shukuri M, Takashima-Hirano M, Tokuda K, Takashima T, Matsumura K, Inoue O. et al. In vivo expression of cyclooxygenase-1 in activated microglia and macrophages during neuroinflammation visualized by PET with 11C-ketoprofen methyl ester. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1094–101. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.084046. doi:jnumed.110.084046 [pii]10.2967/jnumed.110.084046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Vries EFJ, Doorduin J, Vellinga NAR, van Waarde A, Dierckx RA, Klein HC. Can celecoxib affect P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux? A microPET study. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.01.005. doi:10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]