Abstract

Current treatments for human coronary artery disease necessitate the development of the next generations of vascular bioimplants. Recent reports provide evidence that controlling cell orientation and morphology through topographical patterning might be beneficial for bioimplants and tissue engineering scaffolds. However, a concise understanding of cellular events underlying cell-biomaterial interaction remains missing. In this study, applying methods of laser material processing, we aimed to obtain useful markers to guide in the choice of better vascular biomaterials. Our data show that topographically treated human primary vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) have a distinct differentiation profile. In particular, cultivation of VSMC on the microgrooved biocompatible polymer E-shell induces VSMC modulation from synthetic to contractile phenotype and directs formation and maintaining of cell-cell communication and adhesion structures. We show that the urokinase receptor (uPAR) interferes with VSMC behavior on microstructured surfaces and serves as a critical regulator of VSMC functional fate. Our findings suggest that microtopography of the E-shell polymer could be important in determining VSMC phenotype and cytoskeleton organization. They further suggest uPAR as a useful target in the development of predictive models for clinical VSMC phenotyping on functional advanced biomaterials.

Keywords: urokinase receptor, focal adhesion, vascular smooth muscle cell, vascular injury, microstructured biomaterial.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in industrial countries. Negative vascular remodeling resulting in accumulation of new tissue within blood vessel wall plays a principal role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, in-stent restenosis, and graft vasculopathy 1, 2. Although much effort has been devoted to understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms of these processes, the pathogenesis remains largely unknown and, consequently, effective therapy has not yet been established 3. Current invasive treatment strategies are based on usage of either autologous vein grafts or vascular bioimplants to bypass occluded arteries. Increasing body of evidence suggests that biomaterial surface topography independently of its biochemical and biomechanical properties significantly affects biological response, such as cell morphology, proliferation, migration, adhesion, endocytosis, and gene expression pointing to importance of the topographical cues for bioimplants 4. Consequently, novel classes of the next generation of biomaterials have been designed by means of micro- and nanofabrication techniques and examined for affecting functional properties of different cell types 5. Data from this research contributed significantly to understanding of topography-mediated cell fate determination. However, cellular and molecular events initiated by surface pattering and related controlling mechanisms remain sparsely explored. Even less is known regarding specific functional behavior and underlying mechanisms for vascular cells. It is not clear what type of proteins may mediate and affect the mechanism vascular cells utilize to recognize and response to topographically modified surfaces.

In propagation of occlusive cardiovascular disease, the main role is attributed to vascular smooth muscle cells (VSCM) migrating into intima, where they proliferate and produce extracellular matrix (ECM) 6, 7. In “healthy” contractile state, the main function of VSMC is to maintain vascular tone via cell contraction/relaxation. However, in response to injury VSMC change from their physiological contractile to the pathophysiological synthetic phenotype and acquire ability to migrate, proliferate and produce ECM. Multiple factors influencing phenotypic modulation of VSMC have been identified. Among them are soluble factors such as cytokines and growth factors, mechanical stress, ECM composition. We have recently demonstrated that the urokinase receptor uPAR is one of the key regulators of VSMC transdifferentiation contributing to development of negative vascular remodeling in in vitro and in vivo models 8.

The aim of this study was to analyze VSMC properties and physiological responses by applying topographic features of the biocompatible polymer E-shell. One further objective was to elucidate a probable role for uPAR in these processes.

To address these aims, polymer structures in form of grooves and gratings were fabricated on glass substrates by two-photon polymerization (2PP). 2PP is technology based on photo-polymerization of photo-curable resin induced by two-photon absorption of light by molecules of photo-starter 9. 2PP is mostly aiming at 3D fabrication with resolution beyond the diffraction limit 10. Nevertheless, applications of 2PP technique are of a much broader range. If more standard 2D polymer structures have to be fabricated, 2PP can be an alternative to commonly used UV lithography. Advantage of 2PP technique is its high flexibility. On the contrary to standard UV lithography, no mask is needed for 2PP fabrication. The structures parameters can be flexibly modified. Since small feature size is not required, in order to speed up the fabrication large voxel size formed by low numerical aperture focusing optics was used in combination with the high energy femtosecond laser pulses. That allowed rapid fabrication of large structures appropriate for performing cell culture study.

Material and Methods

Substrate fabrication

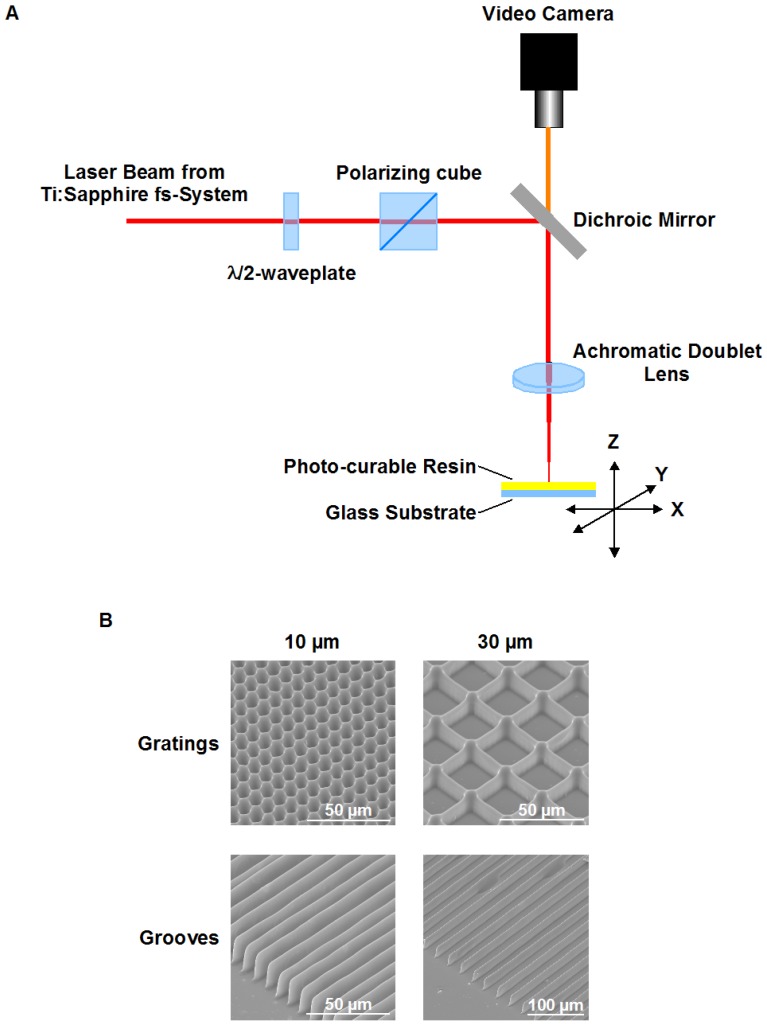

Structures used in this research were fabricated with a setup, based on femtosecond laser system with regenerative amplification (Spitfire Pro 35F-XP from Spectra-Physics). The laser system is capable to deliver up to 3.5 mJ pulses at 1 kHz with pulse duration of 50 fs. Detail arrangement of the fabrication setup is presented in Fig. 1A. The optical beam path incorporated a combination of a λ/2 waveplate and a polarizer cube for the pulse energy adjustment. The beam was focused by the achromatic doublet lens. Structures were obtained after scanning a layer of photo-curable resin on a glass substrate in the lens focal plane. Scanning of the horizontally oriented sample was done by a PC-controlled x-y translation stages (M-511.DG, Physik Instrumente GmbH, Germany). Vertically sample was positioned by Physik Instrumente M-451.1DG PC-controlled translation stage. Fabrication process was observed in real time with use of video camera.

Fig 1.

Fabrication of microstructured e-Shell substrates using 2PP. A. Fabrication setup. The optical beam path incorporated a combination of a λ/2 waveplate and a polarizer cube for the pulse energy adjustment. The beam was focused by the achromatic doublet lens. Structures were obtained after scanning a layer of photo-curable resin on a glass substrate in the lens focal plane. Scanning of the horizontally oriented sample was done by a PC-controlled x-y translation stages. Vertically sample was positioned by the PC-controlled translation stage. Fabrication process is observed in real time with use of video camera. B. SEM images of example structures.

Round glass cover slips (12 mm diameter) were used as substrates for the biocompatible photo-curable acrylate resin e-Shell 300 from envisionTEC GmbH, Germany (CE certified and Class-IIa biocompatible according to ISO 10993). Adhesion of the resin to the substrates was improved through silanization of the glass surface by 3-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (Polysciences, Inc., USA). The resin was spin-coated on the cleaned and dried substrates. Samples were pre-baked on a hot plate at 60°C for 15 min and degassed in vacuum prior to structuring. Resulting thickness of the e-Schell resin layer was of about 20 µm.

Four sets of the structures were fabricated by 2PP: grooves with period of 10 µm; grooves with period of 30 µm; square gratings with period of 10 µm; square gratings with period of 30 µm. Structures with 10 µm and 30 µm periodicity were fabricated with the use of 60 mm and 80 mm focal length achromatic doublets, respectively. The 10 µm structures were scanned at the speed of 3 mm/s with average laser power of 0.5 mW. The 30 µm structures were fabricated at 4 mm/s scan speed with 0.78 mW average laser power. Each line in the structures was scanned four times. After laser processing samples were developed in isopropanol in order to remove nonpolymerized resin.

The resulting polymer structures spans over 6 mm x 6 mm area and has a rectangular shape approximately centered on the glass coverslip. Dimensions of the structures were estimated with use of scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging. An SEM images of example structures are shown in Fig. 1B.

Several samples were illuminated by UV lamp instead of laser processing so that uniform polymer film is formed on the glass substrate. These samples were used in control experiments. Control samples also were cleaned in isopropanol after UV polymerization.

Cell culture and cell nucleofection

Human VSMC were isolated from umbilical arteries using explant technique in VascuLife SMC cell culture medium (CellSystems® Biotechnologie Vertrieb GmbH). VSMC were used between passages 4-6. After 1st passage, fibroblasts were removed from the culture by cell separation using monoclonal anti-fibroblasts antibodies (anti-CD90, Dianova) and magnetic Dynabeads® Goat anti-Mouse IgG (Invitrogen). Primary VSMC were transfected using Amaxa Nucleofector I (Lonza Group Ltd) and Human Primary Smooth Muscle Cells Basic Nucleofection Kit accordingly to manufacturer's instructions. Control and uPAR siRNA duplexes were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. VSMC were seeded on UV-sterilized e-Shell structured substrates and cultivated for 3-5 days. 16 hrs before fixation, cells were starved in serum-free medium.

Immunocytocheminstry

For immunocytochemical staining, VSMC were fixed by addition of 37% PFA to culture medium to give final PFA concentration of 2%. After 10 min fixation at room temperature cells were washed with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% triton X100/PBS for 10 min at room temperature, blocked with 3% BSA/PBS overnight at 4°C. Labelling with primary antibody (2 hrs) and fluorescent secondary antibodies (1 h) was performed in the dark at room temperature. Monoclonal anti-SMA and anti-Calponin antibody was from Sigma; anti-Connexin 43 antibody was from Cell Signaling; monoclonal anti-uPAR (3937) antibody was from American Diagnostica; polyclonal anti-focal adhesion kinase antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; anti-phospho (Tyr397) focal adhesion kinase antibody was from Transduction Laboratories. Fluorescently labelled secondary antibody was from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen). As DNA stain DraQ5 (Biostatus Limited) was used. Coverslips were mounted using Aqua PolyMount medium (Polysciences).

The fluorescence cell images were captured using a Leica TCS-SP2 AOBS confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). All the cell images were taken with oil-immersed x63 objective, NA = 1.4. All the images were acquired with a resolution of 1024 x 1024 pixels.

The cells shape with respect of their elongation was characterized using Circularity plugin of ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.42, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/plugins/circularity.html). A circularity value of 1 indicates a perfect circle. As the value approaches 0, it indicates an increasingly elongated shape. Images intensity profiles along the lines indicated on the figure were created using ImageJ software.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was isolated from UASMC using QIAGEN QiaSpin miniprep kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. TaqMan analysis was performed on a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System using LightCycler® 480 RNA Master Hydrolysis probes (Roche Applied Sciences). Nucleotide sequence of primers used for TaqMan RT-PCR is given in Table 1. Beta-glucuronidase (GUSB) expression was used for normalization.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequence of primers used for TaqMan RT-PCR.

| Name | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GUSB | Sense | 5'-GTGGTGCTGAGGATTGGCA-3' |

| Antisense | 5'-TAGCGTGTCGACCCCATTC-3' | |

| Probe | 6-FAM-TGCCCATTCCTATGCCATCGTGTG- TAMRA | |

| SMA | Sense | 5'-CAAGTGATCACCATCGGAAATG-3' |

| Antisense | 5'-GACTCCATCCCGATGAAGGA-3' | |

| Probe | 6-FAM-CGTTTCCGCTGCCCAGAGACCC-TAMRA | |

| Calponin | Sense | 5'-GCCAACGACCTGTTTGAGAAC-3' |

| Antisense | 5'-GCCATGCTGGCCAAAGC-3' | |

| Probe | 6-FAM-CCAACCATACACAGGTGCAGTCCACC-TAMRA | |

| uPAR | Sense | 5'-ACCACCAAATGCAACGAGG-3' |

| Antisense | 5'-GTAACACTGGCGGCCATTCT-3' | |

| Probe | 6-FAM-CAATCCTGGAGCTTGAAAATCTGCCG-TAMRA | |

| Cx 43 | Sense | 5'-GGTGACTGGAGCGCCTTAG-3' |

| Antisense | 5'-CAGCAGGATTCGGAAAATGAAAAG-3' | |

| Probe | 6-FAM-ACAGCCACACCTTCCCTCCAGCAGT-TAMRA |

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using the two-tailed Student's t test for independent samples (OriginPro 8 SRO). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant at a value of p<0.05 that is indicated as “*”.

Results

VSMC on topographically modified E-shell substrates

Microgrooved and micrograting substrates were fabricated on E-shell polymer with similar depth of 20 μm and periods of 10 and 30 μm. The quality, reproducibility, and fidelity of fabrication process were analyzed using light and electron microscopy (Fig. 1B).

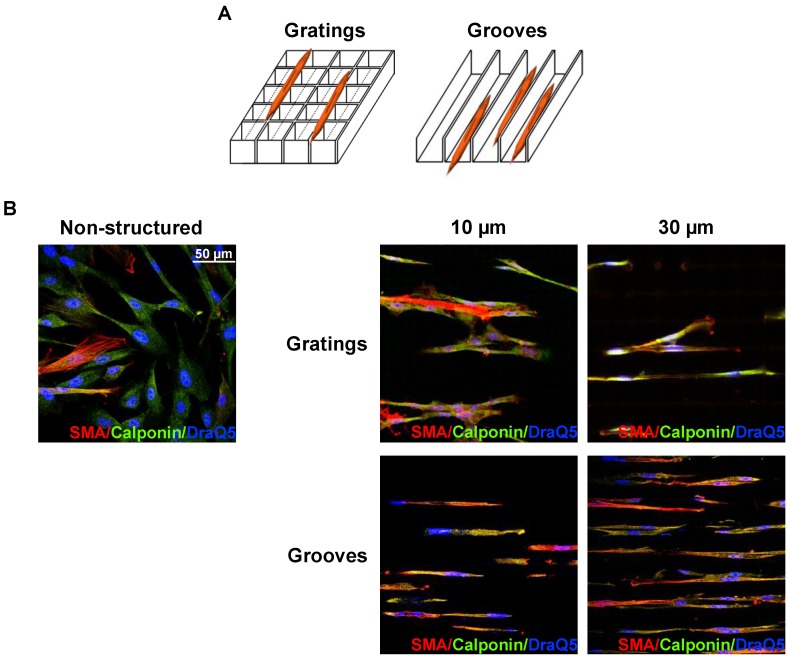

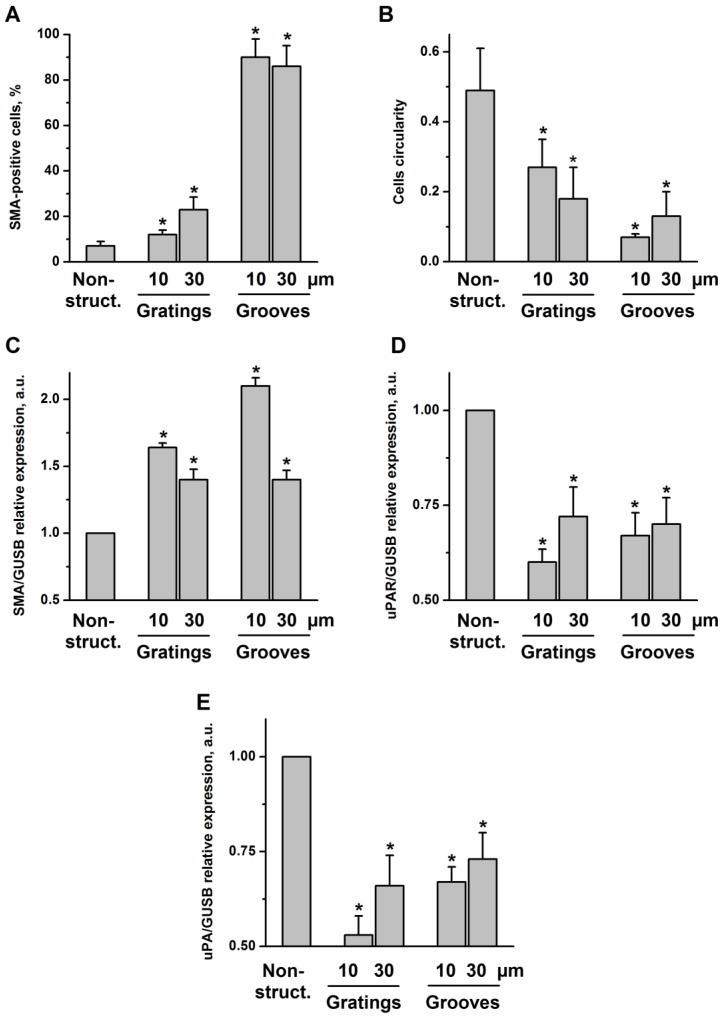

VSMC were seeded on structured substrates and cultured for 3-5 days; non-structured flat E-shell surfaces served as controls. To examine whether and how VSMC phenotypic behavior might be affected by substrate microtopography, cells were immunofluorescently stained for specific contractile marker proteins, such as SMA and calponin, and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 2B). We observed that VSMC cultured on structured substrates revealed clearly different morphology than those on the non-structured controls. When placed on grooved substrates, VSMC lied inside the grooves and acquire elongated morphology. Even when placed on 10 µm-wide grooves, VSMC were located inside the grooves that lead to extreme cell and nucleus elongation. Interestingly, when placed on grating structure of the same height, the cells elongate on the top of the grating without contacting the bottom of the wells (schematically shown in Fig. 2A). VSMC morphology changes from elongated spindle-like shape towards spread-out epithelioid/rhomboid cell shape accompany VSMC phenotypic modulation and may reflect and control proliferative properties of cells 11. Our observations indicate that on micro-structured substrates VSMC reveal elongated morphology and exhibit a very strong alignment along the direction of the grooves (Fig. 2B). Expression of both SMA and calponin in VSMC cultured on the grooves was upregulated confirming a contractile phenotype of these cells. Quantification of these data shown in Fig. 3A demonstrates that the percentage of cells in the contractile state increased on the structured substrates especially on grooved surface. We next performed quantitative analysis of cell morphology changes and calculated circularity of VSMC cultivated on structured substrates as described in above using ImageJ software analysis. The perfect circle has the circularity parameter equal to 1. Decrease of circularity value reflects more elongated cell shape. As shown in Fig. 3B, circularity of cells on structured substrates was dramatically decreased that illustrates VSMC morphological changes towards more functional elongated spindle phenotype. Taq Man analysis confirmed elevated expression of SMA in VSMC cultivated on structured surface (Fig. 3C). On the contrary, expression of uPAR and its ligand urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) is decreased (Fig. 3D, E).

Fig 2.

VSMC cultivation on microstructured substrates. A. Schematic presentation of VSMC location on grating and groove substrates. Independently, whether 10 µm or 30 µm period grating was used, VSMC elongate on the top edge of the gratings (Left panel). On the contrary, on grooved substrate VSMC were located inside the grooves (Right panel). B. VSMC cultured on non-structured and structured as indicated e-Shell were fixed and stained for SMA(Cy3), Calponin (Alexa 488) and DraQ5 as nuclear stain.

Fig 3.

VSMC on structured substrate acquire contractile phenotype. A. Quantification of percentage of cells containing SMA-positive contractile fibrils after VSMC cultivation of non-structured and structured substrates. B. Morphology of VSMC cultivated on non-structured and structured substrates was characterized by calculating cells circularity using ImageJ software. Expression of SMA (C), uPAR(D), and uPA (E) in VSMC cultivated on plane and structured substrate was assessed by TaqMan RT-PCR. GUSB expression was used for normalization.

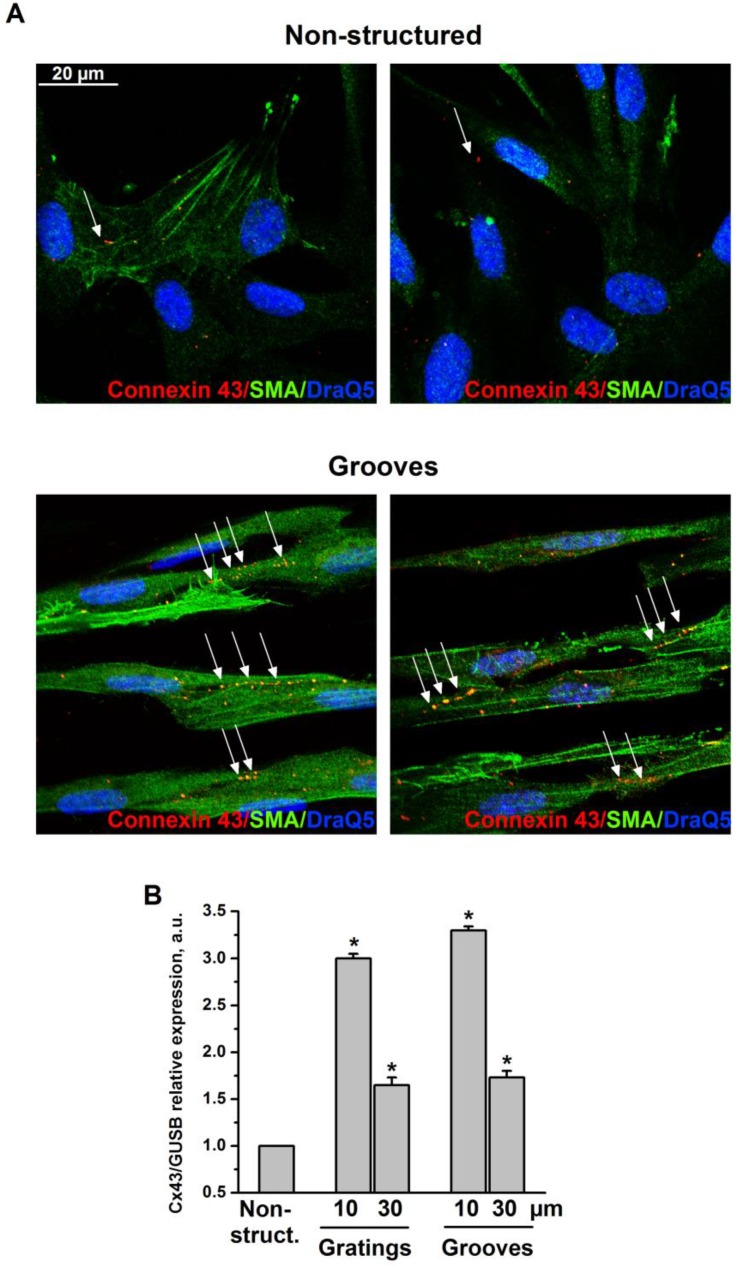

Substrate microtopography affects formation of intercellular contact structures

Formation of a functional layer of interconnecting VSMC is a prerequisite for neovascularization and a fundamental part of the vascular repair. Specifically, connexin 43 (Cx43), which is the major component of gap junctions expressed in VSMC is supposed to play a key role in neointima formation after vascular injury in vivo 12. Therefore, we next analyzed cell-cell interactions and localization of Cx43 in VSMC cultured on grooved surfaces (Fig. 4A). 30 μm grooves were used. We observed that cells exhibited stronger interaction capability when cultured on 30 μm grooves compared with non-structured controls. Specifically, cells formed intercellular contacts when aligned according to the grooves. Cx43 was randomly distributed over the cell body in control samples. However, in response to topographical modification Cx43 underwent a relocalization to clearly formed junctional plaques at intercellular boundaries within the grooves. Cx43 expression was also upregulated in VSMC cultivated on structured substrates as was shown by TaqMan RT-PCR (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

VSMC on grooves but not on non-structured e-Shell develop Cx43-containing cell-cell contacts. A. VSMC cultivated on non-structured e-Shell and on 30 µm groove substrates were fixed and stained for Cx43 (Alexa 594), SMA (Alexa 488) and DraQ5 as nuclear stain. Arrows indicate single randomly distributed cell-cell junctions on control substrate and highly organized functional junctions between cells cultivated on grooves. B. Cx43 expression was assessed by TaqMan analysis. GUSB expression was used for normalization.

uPAR counteracts effects of structured substrates on VSMC morphology and phenotype

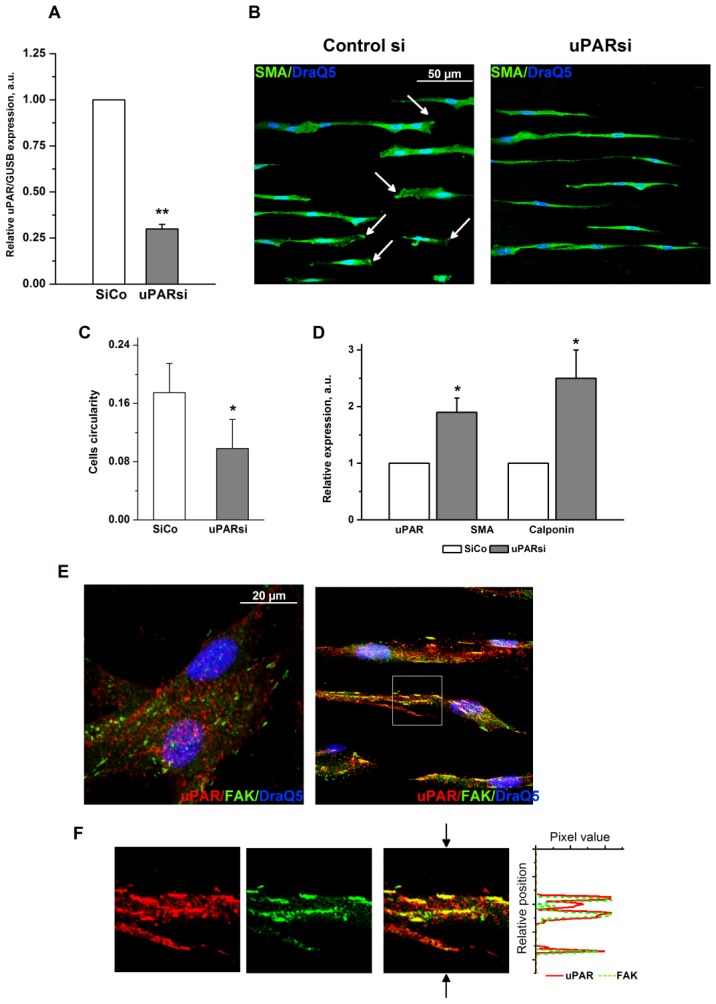

The multifunctional cell surface receptor uPAR has been recognized as one of the key regulators of VSMC functional responses 13, 14. Specifically, uPAR upregulation in VSMC supports pathophysiological synthetic cell phenotype, whereas uPAR deficiency results in transdifferentiation to physiological contractile phenotype 8, 15. To explore whether uPAR might interfere with effects induced by changes in surface microtopography, we used VSMC with uPAR downregulation that was effectively achieved by means of small interfering RNA. Since VSMC functional behavior was strongly affected by surface topography and microgrooves induced a phenotypic switch to contractile phenotype, we did not expect that uPAR deficiency could affect VSMC any further. Interestingly, we observed, however, that uPAR downregulation (Fig. 5A) resulted in significantly pronounced further cell elongation as judged by measurement of cells circularity (Fig. 5B, C) thus pointing to uPAR indispensability in regulation of VSMC functions. Control VSMC cultured on microgrooves, though being phenotypically modified, still retained a clear cell polarization pattern that reflects their migratory capacity. In uPARsi VSMC, cell polarization was completely abolished (Fig. 5B). TaqMan analysis confirmed that expression of contractile proteins, namely SMA and calponin is further upregulated after uPARsi in comparison to SiCo VSMC (Fig. 5D).

Fig 5.

uPAR counteracts substrate topography-induced VSMC morphological changes. A. Efficiency of uPAR expression downregulation was assessed by TaqMan analysis. GUSB expression was used for normalization. B. VSMC nucleofected with control siRNA or uPARsi RNA and cultivated on 30 µm groove substrates were fixed and stained for SMA (Alexa 488) and DraQ5 as nuclear stain. Arrows in the left panel indicate cells with clearly developed leading edge. C. More elongated morphology of uPARsi VSMC was characterized by calculating cells circularity using ImageJ software. D. Relative expression of SMA and calponin in SiCo and uPARsi VSMC cultivated on 30 µm groove substrates was assessed by TaqMan analysis. GUSB expression was used for normalization. E. VSMC cultivated on non-structured E-Shell and 30 µm groove substrate were fixed and stained for uPAR (Alexa 594) and FAK (Alexa 488) to reveal focal adhesions. F. The panels show indicated area of the right upper panel. The right panel shows image intensity profiles obtained using ImageJ software. The position of the image used for image intencity profile is shown by arrows.

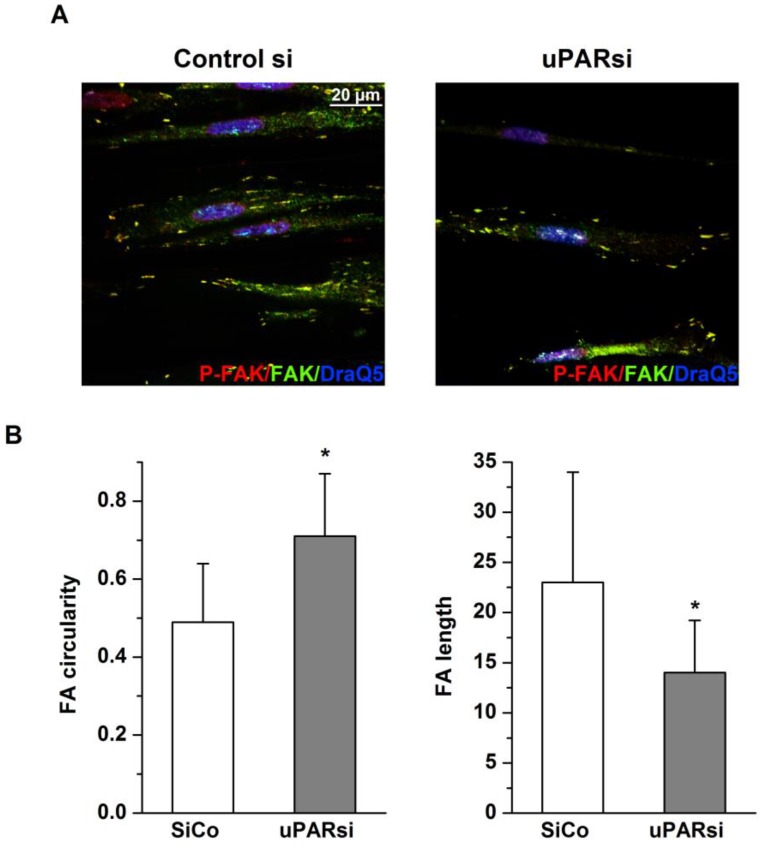

uPAR stabilizes focal adhesion complexes in VSMC on microgrooves

Focal adhesions, the specific structures providing cell attachment to the substrate, are implicated as important regulators in cellular responses to surface topographical modification 16. Specifically, a pivotal role was attributed to a balance between maturation of focal adhesion structures and related cell signaling in these processes 17. To address this issue in the next experimental settings, immunocytochemical analysis of VSMC cultured on structured and control surfaces and stained for focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and uPAR was performed. As shown in Fig. 5E, cells cultured on microgrooves, but not on control surfaces, exhibited formation of clearly mature focal adhesions where both uPAR and FAK were colocalized. Image intencity profiles shown in Fig. 5F confirm colocalization of proteins. We further analyzed the morphology of focal adhesions of control and uPARsi VSMC cultivated in microgrooves. As shown in Fig. 6 A, B, focal adhesions in uPARsi cells were less developed, as measured by average circularity and length of focal adhesions. Circularity of focal adhesions in uPARsi cells was higher, whereas their length was shorter. That points to impaired maturation and formation of active focal adhesions in VSMC with uPARsi providing thus evidence for uPAR involvement in this process.

Fig 6.

uPAR stabilizes focal adhesion complexes in VSMC on microgrooves. A. VSMC nucleofected with control siRNA or uPARsi RNA and cultivated on 30 µm groove substrates were fixed and stained for Phospho-FAK (Alexab 594), FAK (Alexa 488) and DraQ5 as nuclear stain. B. Morphological features of FA of SiCo and uPARsi-nucleofected VSMC were quantified using ImageJ software. The left panel shows average FA circularity, the left panel shows average FA length.

Discussion

The multifunctional receptor uPAR plays a pivotal role in vascular remodeling acting either together with its natural ligand, uPA, or in an uPA-independent fashion. Both, uPA and uPAR are upregulated in vascular tissue upon response-to-injury process and promote vascular remodeling 18 and remodeling-related inflammation 19, 20 in cardiovascular diseases. The uPA/uPAR system controls functional properties of VSMC, such as migration, proliferation, and deposition of extracellular matrix proteins 13. Our recent studies provide evidence that uPAR is an active regulator of VSMC phenotypic changes 15, 21 and dissect the complex cascade of uPAR-directed molecular events leading to VSMC transition from their physiological contractile to the pathophysiological synthetic phenotype 8. Our further research points to uPAR involvement in propagation and transmission of mechanical stimuli in VSMC 22. In this study, we aimed at translation of these collective findings into the clinical arena. We show that surface topographical microstructuring influences the VSMC phenotype in a manner that could be relevant for the next generation biomaterials used for vascular applications. Our data further indicate that uPAR actively interferes with VSMC functional behavior on structured substrates and suggest uPAR targeting as a promising tool to control tissue-bioimplantable device response.

Accumulating evidence indicates that substrate topography regulates main cellular functions 23, 24. Ability to control cell properties and physiological responses by artificially created surface topography is of great importance for the development of biomedical implants, since performance of many implantable medical devices is dependent on the desired device-tissue response. However, the effects of surface topography on vascular cells and, in particular, on human VSMC functional behavior are less examined 25-27. Studies on cell orientation and morphology using micro- and nanostructured surfaces have shown that grooved topographies induce elongation and nuclear polarization in a very wide range of cell types, such as macrophages, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, nerve cells and mesenchymal stem cells 28-31. A few number of reports documented similar elongated morphologies and lower proliferation rates for VSMC 11, 32. These studies support our observations that E-shell fabricated microgrooves induce VSMC alignment to the long axis of the grooves, cell elongation, and reorganization of the cytoskeleton. However, there is not a common trend for changes in cell morphology regarding grooves depths and widths that could be related to properties of material used for grooves fabrication. Our results show that beyond changes in cell morphology, microgrooved E-shell surfaces affected gene expression and resulted in upregulated expression of contractile marker proteins and in a switch to contractile VSMC phenotype. We also found that microgrooves promoted intercellular contacts and formation of junctional complexes enriched in Cx43.

We were interested to know whether uPAR, which is an important modulator of VSMC functions, may affect changes in cell properties on microstructured surfaces. We observed that uPAR expressing VSMC exhibited a contractile phenotype when cultured on microgrooves. Since uPAR generally supports VSMC synthetic phenotype, these data may imply that effects of surface topography could overcome or bypass those of uPAR. However, experiments on VSMC with downregulated uPAR provide evidence that uPAR actively counteracts with topography directed cell changes. Specifically, uPAR deficiency lead to further significant increase in VSMC elongation, loss of cell polarization, and changes in maturation of focal adhesion structures.

Focal adhesions are dynamic structures playing a pivotal role in cellular response to surface topography 17. Beyond mediating adhesive functions, focal adhesions mediate bidirectional signaling between the cell and its environment recruiting diverse signaling molecules. This chain of signaling events promotes posttranslational modification of critical proteins culminating in changes of transcriptional regulation and gene expression 16, 17. In vascular wall, focal adhesion structures serve as mechanosensors translating mechanical signals, such as hemodynamic forces or vascular topography, to biochemical events 33. Recent studies provide evidence that topographical properties of biomaterials affect focal adhesion formation and related cellular functions, though the observed effects varied significantly depending on cell type and parameters of surface fabrication 17. We observed that VSMC culturing on E-shell microgrooves correlated with formation of mature elongated focal adhesion plaques. We further found that uPAR was colocalized in these structures with FAK, which is one of the main proteins acting at the crossroads of signaling pathways within the focal adhesion complexes 34. Obviously, uPAR was required for maturation of focal adhesion structures, because uPAR silencing strongly impaired their size, shape and cellular distribution. These data further imply that these properties of adhesion complexes may be involved in controlling VSMC transcriptional activity leading to phenotypic changes initiated by substrate topography and counteracted by uPAR.

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that substrate micro- and nanotopography is a powerful tool to modify differentiation of stem cells 16, 35. It was suggested that focal adhesion formation, in particular their maturation and elongation, may be critical for related signaling machinery and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) 17. MSC are considered as the most attractive and reliable candidate for tissue repair including vascular regeneration 36-38. We have shown earlier that uPAR is an important mediator of MSC differentiation to VSMC lineage 39. Whether and how uPAR may interfere with MSC differentiation and cell fate on microstructured bioimplants remains an intriguing topic for the future research with a big potential for clinical translation. One further question to be addressed in the future studies are the mechanisms, both gap junction-dependent und independent, mediating the revealed intercellular communications on microgrooves and uPAR participation in these processes.

In the last decades, integration of new physical methods in biological science, has led to developing of new materials and tools. 2PP is a very promising technology for fabrication of micrometer scale biomedical devices, patient-specific medical prosthesis and scaffolds for tissue engineering 39, 40. Arrays of microneedles for transdermal drug delivery were successfully fabricated with this technology41. Middle-ear bone replacement prosthesis was fabricated as an example of personalized prosthesis42. Our data provide evidence that artificially created surface microtopography using biocompatible E-shell polymer possesses the ability to control VSMC properties and physiological responses. These findings serve as a reliable basis for application of this topographycally treated biopolymer for vascular prosthesis, such as vascular stents. For more clinical relevance, in vivo studies should be performed, to examine how substrate topography of the biocompatible polymer E-shell used as a stent may affect VSMC functional behavior under blood circulation. Our data inspirit further research on uPAR as an attractive target for vascular tissue repair and new therapeutic strategies for vascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Petra Wuebbolt-Lehmann and Birgit Habermeier for excellent technical assistance. This study was funded by the Grant P59/10//A101/10 from Else Kroener-Fresenius-Stiftung; Grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [DU 344/7-1 and KI 1376/2-1]; Grant “Development and fabrication of functional micromechanical and MicroOptoElectro-Mechanical Systems (MOEMS) by ultra-high resolution 3D multi-photo material processing of new polymer materials” from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

References

- 1.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: A perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garas SM, Huber P, Scott NA. Overview of therapies for prevention of restenosis after coronary interventions. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;92:165–178. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinez E, Engel E, Planell J, Samitier J. Effects of artificial micro- ad nano-structured surfaces on cell behavior. Annals Anatomy. 2009;191:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtis A, Dalby M, Gadegaard N. Cell signaling arising from nanotopography: Implications for nanomedical devices. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2006;1:67–72. doi: 10.2217/17435889.1.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rzucidlo EM, Martin KA, Powell RJ. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:25A–32A. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiyan Y, Limbourg A, Kiyan R, Tkachuk S, Limbourg F, Ovsianikov A, Chichkov B, Haller H, Dumler I. Urokinase receptor associates with myocardin to control vascular smooth muscle cells phenotype in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:110–122. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ovsianikov A, Passinger S, Houbertz R, Chichkov BN. Laser ablation and its applications. Springer Series in Optical Sciences. 2007;129:121–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Fourkas JT. Multiphoton polymerization. Materials Today. 2007;10:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thakar R, Cheng Q, Patel S, Chu J, Nasir M, Liepmann D, Komvopoulos K, Li S. Cell-shape regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation. Biophys J. 2009;96:3423–3432. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song M, Yu X, Cui X, Zhu G, Zhao G, Chen J, Huang L. Blockage of connexin 43 hemichannels reduces neointima formation after vascular injury by inhibiting proliferation and phenotypic modulatiopn of smooth muscle cells. Exp Biol Med. 2009;34:1192–1200. doi: 10.3181/0902-RM-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binder BR, Mihaly J, Prager GW. Upar-upa-pai-1 interactions and signaling: A vascular biologist's view. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuhrman B. The urokinase system in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;32:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiyan J, Smith G, Haller H, Dumler I. Urokinase receptor-mediated phenotypic changes of vascular smooth muscle cells require involvement of membrane rafts. Biochem J. 2009;423:343–351. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamara L, McMurray R, Biggs M, Kantawong F, Oreffo R, Dalby M. Nanotopographical control of stem cell differentiation. J Tissue Eng. 2010;2010:1–13. doi: 10.4061/2010/120623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biggs M, Richards R, Dalby M. Nanotopographical modification: A regulator of cellular function through focal adhesions. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steins mB, Padro T, Schwaenen C, Ruiz S, Mesters RM, Berdel WE, Kienast J. Overexpression of urokinase receptor and cell surface urokinase-type plasminogen activator in the human vessel wall with different types of atherosclerotic lesions. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2004;15:383–391. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000114441.59147.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu J-M, Johns A, Morser J, Dole WP, Greaves DR, Deng GG. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor promotes macrophage infiltration into the vascular wall of apoe deficient mice. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:73–82. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shushakova N, Eden G, Dangers M, Menne J, Gueler F, Luft FC, Haller H, Dumler I. The urokinase/urokinase receptor system mediates the igg immune complex-induced inflammation in lung. J Immunol. 2005;175:4060–4068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiyan J, Kusch A, Tkachuk S, Kramer J, Dietz R, Smith G, Dumler I. Rosuvastatin regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation in vascular remodeling: Role for the urokinase receptor. Atheriosclerosis. 2007;195:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dangers M, Kiyan J, Grote K, Schieffer B, Haller H, Dumler I. Mechanical stress modulates socs-1 expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Res. 2010;47:432–440. doi: 10.1159/000281583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bettinger C, Langer R, Borenstein J. Engineering substrate topography at the micro- and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5406–5415. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guduru D, Niepel M, Vogel J, Groth T. Nanostructured material surfaces - preparation, effect on cellular behavior, and potential biomedical applications: A review. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34:963–985. doi: 10.5301/IJAO.5000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller D, Thapa A, Haberstroh K, Webster T. Enhanced functions of vascular and bladder cells on poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid polymers with nanostructured surfaces. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2002;1:61–66. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2002.806917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pareta R, Reising A, Miller T, Storey D, Webster T. Increased endothelial cell adhesion on plasma modified nanostructured polymeric and metallic surfaces for vascular stent applications. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:459–471. doi: 10.1002/bit.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller D, Haberstroh K, Webster T. Mechanism(s) of increased vascular cell adhesion on nanostructured poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) films. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;73:476–484. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark P, Connolly P, Curtis A, Dow J, Wilkinson C. Topographical control of cell behaviour: Ii. Multiple grooved substrata. Development. 1990;108:635–644. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyle J, Gültig K, Nisch W. Variation in contact guidance by human cells on a microstructured surface. J Biomed Mater Res. 1995;29:81–88. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820290112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wójciak-Stothard B, Madeja Z, Korohoda W, Curtis A, Wilkinson C. Activation of macrophage-like cells by multiple grooved substrata. Topographical control of cell behaviour. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:485–490. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1995.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn G, Brown A. Alignment of fibroblasts on grooved surfaces described by a simple geometric transformation. J Cell Sci. 1986;83:313–340. doi: 10.1242/jcs.83.1.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mai J, Sun C, Li S, Zhang X. A microfabricated platform probing cytoskeleton dynamics using multidirectional topographical cues. Biomed Microdevices. 2007;9:523–531. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romer L, Birukov K, Garcia J. Focal adhesions: Paradigm for a signaling nexus. Circ Res. 2006;98:606–616. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207408.31270.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaller M. Biochemical signals and biological responses elicited by the focal adhesion kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1540:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirmizidis G, Birch M. Microfabricated grooved substrates influence cell-cell communication and osteoblast differentiation in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1427–1436. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J, Fang W, Krasnodembskaya A, Howard J, Matthay M. Concise review: Mesenchymal stem cells for acute lung injury: Role of paracrine soluble factors. Stem Cells. 2011;29:913–919. doi: 10.1002/stem.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang NF, Li S. Mesenchymal stem cells for vascular regeneration. Regen Med. 2008;3:877–892. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.6.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams AR, Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: Biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:923–940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doraiswamy A, Jin C, Narayan RJ, Mageswaran P, Mente P, Modi R, Auyeung R, Chrisey DB, Ovsianikov A, Chichkov B. Two photon induced polymerization of organic-inorganic hybrid biomaterials for microstructured medical devices. Acta Biomaterialia 2. 2006;2:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlie S, Ngezahayo A, Ovsianikov A, Fabian T, Kolb HA, Haferkamp H, Chichkov BN. Three-dimensional cell growth on structures fabricated from ormocer by two-photon polymerization technique. J Biomater Appl. 2007;22:275–287. doi: 10.1177/0885328207077590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ovsianikov A, Chichkov B. Two photon polymerization of polymer-ceramic hybrid materials for transdermal drug delivery. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2007;4:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ovsianikov A, Chichkov B, Adunka O, Pillsbury H, Doraiswamy A, Narayan RJ. Rapid prototyping of ossicular replacement prostheses. Applied Surface Science (2007) 2007;253:6603–6607. [Google Scholar]