Abstract

Objective

A retrospective case report of a 24-year-old man with recurrent lumbar disk herniation and epidural fibrosis is presented. Recurrent lumbar disk herniation and epidural fibrosis are common complications following lumbar diskectomy.

Clinical Features

A 24-year-old patient had a history of lumbar diskectomy and new onset of low back pain and radiculopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed recurrent herniation at L5/S1, left nerve root displacement, and epidural fibrosis.

Intervention and Outcomes

The patient received a course of chiropractic care including lumbar spinal manipulation and rehabilitation exercises with documented subjective and objective functional and symptomatic improvement.

Conclusion

This case report describes chiropractic management including spinal manipulative therapy and rehabilitation exercises and subsequent objective and subjective functional and symptomatic improvement.

Key indexing terms: Low back pain, Recurrent, Disk displacement, Intervertebral, Chiropractic manipulation, Diskectomy

Introduction

Lumbar disk herniation is a common cause of low back pain and/or sciatica. In 23% to 48% of cases, radiculopathy caused by lumbar disk herniation resolves spontaneously.1 Cases that do not resolve spontaneously may be treated operatively or nonoperatively.2 One option for operative management is diskectomy. Following lumbar diskectomy, recurrent lumbar disk herniation causing low back pain and/or sciatica occurs in 5% to 18% of postoperative patients, with most occurring between 6 months and 2 years.3 The clinical implications of postoperative fibrosis have been debated, although many treatments to prevent its formation have been developed.4 In a study conducted by Kayaoglu et al, 85 (12%) out of 715 patients with lumbar disk surgery required a subsequent lumbar surgical procedure. Of the 85 patients requiring subsequent operations, 45.8% of patients with epidural fibrosis and a small recurrent protrusion had “excellent” results, 2% had “good” results, 29% had “moderate” results, and 16.7% had “poor” results.5 A trial period of conservative management was not an aim of the study. In contrast, a study conducted by Schlarb and Wenker reported a failure rate for reoperation in patients with epidural fibrosis as high as 76%.6

Clinical guidelines for the management of recurrent lumbar herniation have not been developed. A keyword search using the terms Recurrent lumbar herniation AND Chiropractic was performed using the National Library of Medicine PubMed database. The search revealed no studies documenting chiropractic management of recurrent lumbar disk herniations at the time of this publication. Thus, chiropractic management of these conditions is poorly documented. This case report outlines the successful chiropractic management, including spinal manipulative therapy, of a patient with a large lumbar disk herniation and a history of diskectomy at the same level. Postoperative epidural fibrosis was also detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the time of the recurrent herniation diagnosis.

Case report

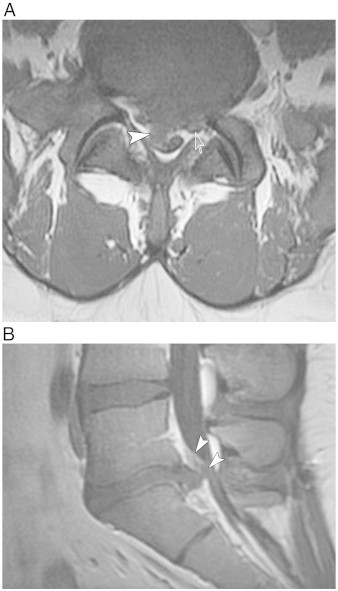

A 24-year-old male family-employed construction and property maintenance worker presented to a chiropractic clinic with a chief concern of low back pain with radiation into the right gluteal region of 4 weeks’ duration. The onset of his symptoms occurred following a heavy snow in which he was required to manually remove snow from the walkways of multiple properties. His medical history included a lumbar disk herniation at L5/S1 that was managed surgically with a diskectomy and partial laminectomy 3 years prior. Following the initial surgery, the patient reported continued, although lessened, localized pain while working. Consultation with his orthopedic surgeon regarding his current chief concern prompted a contrast-enhanced MRI of the lumbar spine. It revealed a large, broad-based paracentral protrusion with ventral thecal sac effacement, encroachment of the left neural foramen, and displacement of the left S1 nerve root (Fig 1A and B). Mildly enhancing epidural fibrosis was present and displaced by the herniation along with the ventral thecal sac. Flexeril (McNeil Consumer and Specialty Pharmaceuticals, Fort Washington, PA) and Naprosyn (Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ) were prescribed in addition to a standing prescription for Percocet (Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA) as needed for pain. Revision surgery was recommended based on the MRI findings. The patient was unable to refrain from working following a surgical intervention and instead opted for chiropractic management of his condition to continue to support his family business. Examination by the chiropractic physician yielded a subjective pain rating of “10/10” at worst on a verbal analog scale. Physical examination was significant for antalgic posture. Deep tendon reflexes were unable to be elicited bilaterally at L4 and S1 levels, although examination by the orthopedic physician reported only diminished left S1 reflexes 3 weeks prior. Sensory examination was within normal limits bilaterally. Motor examination was limited because of patient pain intolerance. Provocation of low back pain with radiation by straight leg raise was elicited at 30° on the left. Valsalva maneuver provoked radiation with cough, sneeze, and bowel movements. No loss of bowel or bladder function was reported. Extension maneuvers were provocative, and active ranges of motion were limited in flexion (40° out of 80°) and extension (20° out of 30°). Spasticity of the lumbar erector spinae musculature was present bilaterally. A Revised Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire7 was administered and revealed 50% disability at presentation.

Fig 1.

Axial (A) and sagittal (B) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance images at L5/S1 demonstrated a large, focal paracentral protrusion with significant ventral thecal sac effacement and encroachment of the left neural foramen at L5/S1. Left-sided nerve root displacement and enhancement were present (open arrow). Mildly enhancing postoperative fibrosis was displaced by the herniation (arrowheads).

Interventions and outcomes

A trial of chiropractic treatment was administered for 12 weeks while the patient continued to work with modification of work posture and limited lifting. A treatment frequency of 3 visits per week for 2 weeks was prescribed. Treatment included flexion/distraction chiropractic manipulation (Fig 2) of the lumbar spine from L5/S1 to L1/2 and postisometric relaxation techniques of the lumbar erector spinae. High-velocity/low-amplitude techniques were not used. Core stabilization and “bird dog” exercises were prescribed at home and reviewed at regular intervals in office. For pain management, a stabilizing lumbar brace was prescribed for use while the patient worked. Following the initial 2-week treatment period, straight leg raise on the left side improved slightly to 35° without pain. Active range of motion with flexion improved to 50° out of 80°, limited because of persistent pain. Subjective pain intensity was reported at 9/10 at worst. Result of Valsalva maneuver was only positive during straining with bowel movements. Oswestry disability score improved to 42%.

Fig 2.

Demonstration of a chiropractic physician performing flexion/distraction chiropractic manipulation technique. (Color version of figure is available online.)

Treatment frequency was tapered to 2 visits per week for 3 weeks with continued flexion/distraction chiropractic manipulation and core stabilization exercises. Because of cancelled visits, the next evaluation was performed at week 6. Straight leg raise improved to 50° with minor radiation provocation. Deep tendon reflexes at L4 and S1 levels returned to normal. Result of Valsalva maneuver was negative. Dependency on the lumbar spine brace while working diminished. Subjective pain intensity was reported at 5/10 at worst. Oswestry disability score improved to 33%.

A total of 27 treatment sessions had been administered at the 12-week reevaluation. Continued progress was monitored with follow-up Oswestry questionnaire revealing 17.7% disability at the end of week 10. Active flexion improved to 80° and extension improved to 30° with mild persistent localized pain. The initial antalgia and pain provocation with Valsalva maneuver and extension motions were resolved. Straight leg raise testing improved to 50° without pain. Subjective pain intensity was reported at 3/10 at worst. The patient was allowed to return to full work without use of the lumbar spine brace. Visit frequency was tapered because of continued patient improvement to 1 visit every other week at the end of week 12 to continue treatment and monitoring of rehabilitation exercises. No “flare ups” were noted for a total of 9 more visits before the patient discontinued care.

Discussion

The presence of recurrent lumbar disk herniation in association with epidural fibrosis is a common cause of recurrent low back pain and/or sciatica following lumbar diskectomy, occurring in 10% to 30% of postoperative patients as reported by Hoogland et al.3 Although the clinical implications of epidural scar have been debated, it is found in 24% of cases of failed back surgery syndrome; and numerous treatments have been implemented to prevent the replacement of normal epidural fat with fibroblasts.4 A prospective study by Lebow et al demonstrated a 23.1% incidence of recurrent same-site herniation within 2 years of operation. Forty-four percent of those recurrent herniations were symptomatic. Those patients with symptomatic recurrent herniations reported worse leg pain and disability 2 years after the initial surgery.8

Current practice guidelines based on a review of the literature performed by Chou et al state that the benefits of diskectomy or microdiskectomy for primary disk herniation with radiculopathy are only moderately superior to conservative management for pain and functional improvements through 2 to 3 months. The results after 2 to 3 months are inconsistent.9 A study conducted by McMorland et al indicated that 60% of patients approved as surgical candidates after failing initial medical management of primary lumbar disk herniations could gain equal pain relief with a regimen of spinal manipulative treatment compared with patients undergoing a primary diskectomy. Those patients also gained statistically significant quality of life and disability improvements and aided in avoidance of surgical management.10 Patients that fail primary surgical management are at high risk for failure of subsequent operations.11 The financial costs associated with patients requiring revision surgery following recurrent herniation are also significantly higher (US $39 836) than those in cases of recurrent herniation that respond to conservative management (US $2315).12 It has also been found that imaging is not indicated in the first 4 to 6 weeks of acute symptoms of herniation because 70% of patients will have subjective and objective improvement in this time frame.13 Imaging findings are a poor indicator of outcomes, as imaging signs of herniation resolution tend to lag behind signs of clinical improvement.14

Our case demonstrated subjective and objective improvement in a patient following the initiation of chiropractic management. The patient failed to respond to a prior trial of medical therapy. Chiropractic treatment included spinal manipulative therapy and core strengthening exercises after a recurrent lumbar herniation. Although a diagnosis of diskogenic pain cannot always be definitively provided, a recent study diagnostically provoked diskogenic pain in 82% of patients with a surgical diskectomy and chronic low back pain, making it the most likely source of pain in this population.15 Similar results have been reported in postoperative patients with continued low back pain, although the clinical findings differed in the patient's radiation pattern and imaging was only acquired before the surgery.16 The need for controlled studies of chiropractic management of recurrent herniation and continued low back pain following surgical management is essential. The presence of epidural fibrosis appears to have played a limited role, if any, in the outcome of this case. This opinion has been mirrored in a study by Coskun et al in which postoperative Oswestry scores did not differ significantly among patients with differing levels of fibrosis severity.17

Limitations

This case report has limitations including a relatively short timeline of patient follow-up. As stated previously, repeated MR images may continue to demonstrate the presence of the herniation even though clinical symptoms have resolved. The natural history associated with recurrent lumbar herniation has not been determined, so the comparative effectiveness of our treatment cannot be established. In addition, the results of this case report cannot be generalized to all cases of recurrent or residual low back pain after previous surgical intervention; treatment should be tailored to the needs of the individual patient. Surgical management of this patient's recurrent herniation may still be required. Controlled studies are needed to assess the efficacy of chiropractic manipulative therapy for the treatment of symptomatic recurrent herniations after lumbar diskectomy.

Conclusion

There is little documentation of chiropractic management for symptomatic recurrent lumbar disk herniations following diskectomy. This case report outlines the successful management of a patient with recurrent disk herniation complicated by postoperative epidural fibrosis. Treatment of this condition included chiropractic manipulative therapy and rehabilitation exercises. Subsequent objective and subjective functional and symptomatic patient improvement was recorded.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References

- 1.Manchikanti L., Singh V., Cash K.A., Pampati V., Damron K.S., Boswell M.V. Effect of fluoroscopically guided caudal epidural steroid or local anesthetic injections in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation and radiculitis: a randomized, controlled, double blind trial with a two-year follow-up. Pain Physician. 2012;15(4):273–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tosteson A.N., Tosteson T.D., Lurie J.D., Abdu W., Herkowitz H., Andersson G. Comparative effectiveness evidence from the spine patient outcomes research trial: surgical versus nonoperative care for spinal stenosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis, and intervertebral disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(24):2061–2068. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318235457b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoogland T., van den Brekel-Dijkstra K., Schubert M., Miklitz B. Endoscopic transforaminal discectomy for recurrent lumbar disc herniation: a prospective, cohort evaluation of 262 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33(9):973–978. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816c8ade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rönnberg K., Lind B., Zoega B., Gadeholt-Göthlin G., Halldin K., Gellerstedt M. Peridural scar and its relation to clinical outcome: a randomised study on surgically treated lumbar disc herniation patients. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(12):1714–1720. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayaoglu C.R., Calikoglu C., Binler S. Re-operation after lumbar disc surgery: results in 85 cases. J Int Med Res. 2003;31(4):318–323. doi: 10.1177/147323000303100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erbayraktar S., Acar F., Tekinsoy B., Acar U., Güner E.M. Outcome analysis of reoperations after lumbar discectomies: a report of 22 patients. Kobe J Med Sci. 2002;48(1-2):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairbank J.C. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66(8):271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebow R.L., Adogwa O., Parker S.L., Sharma A., Cheng J., McGirt M.J. Asymptomatic same-site recurrent disc herniation after lumbar discectomy: results of a prospective longitudinal study with 2-year serial imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(25):2147–2151. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182054595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou R., Baisden J., Carragee E.J., Resnick D.K., Shaffer W.O., Loeser J.D. Surgery for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34(10):1094–1109. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a105fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMorland G., Suter E., Casha S., du Plessis S.J., Hurlbert R.J. Manipulation or microdiskectomy for sciatica? A prospective randomized clinical study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(8):576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guyer R.D., Patterson M., Ohnmeiss D.D. Failed back surgery syndrome: diagnostic evaluation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(9):534–543. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrossi G.L., McGirt M.J., Sciubba D.M., Witham T.F., Wolinsky J.P., Gokaslan Z.L. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation after single-level lumbar discectomy: incidence and health care cost analysis. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(3):574–578. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000350224.36213.F9. [discussion 578] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awad J.N., Moskovich R. Lumbar disc herniations: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:183–197. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000198724.54891.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komori H., Shinomiya K., Nakai O., Yamaura I., Takeda S., Furuya K. The natural history of herniated nucleus pulposus with radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21(2):225–229. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199601150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DePalma M.J., Ketchum J.M., Saullo T.R., Laplante B.L. Is the history of a surgical discectomy related to the source of chronic low back pain? Pain Physician. 2012;15(1):E53–E58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estadt G.M. Chiropractic/rehabilitative management of post-surgical disc herniation: a retrospective case report. J Chiropr Med. 2004;3(3):108–115. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coskun E., Süzer T., Topuz O., Zencir M., Pakdemirli E., Tahta K. Relationships between epidural fibrosis, pain, disability, and psychological factors after lumbar disc surgery. Eur Spine J. 2000;9(3):218–223. doi: 10.1007/s005860000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]