Abstract

Summary

The International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) Capture the Fracture Campaign aims to support implementation of Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) throughout the world.

Introduction

FLS have been shown to close the ubiquitous secondary fracture prevention care gap, ensuring that fragility fracture sufferers receive appropriate assessment and intervention to reduce future fracture risk.

Methods

Capture the Fracture has developed internationally endorsed standards for best practice, will facilitate change at the national level to drive adoption of FLS and increase awareness of the challenges and opportunities presented by secondary fracture prevention to key stakeholders. The Best Practice Framework (BPF) sets an international benchmark for FLS, which defines essential and aspirational elements of service delivery.

Results

The BPF has been reviewed by leading experts from many countries and subject to beta-testing to ensure that it is internationally relevant and fit-for-purpose. The BPF will also serve as a measurement tool for IOF to award ‘Capture the Fracture Best Practice Recognition’ to celebrate successful FLS worldwide and drive service development in areas of unmet need. The Capture the Fracture website will provide a suite of resources related to FLS and secondary fracture prevention, which will be updated as new materials become available. A mentoring programme will enable those in the early stages of development of FLS to learn from colleagues elsewhere that have achieved Best Practice Recognition. A grant programme is in development to aid clinical systems which require financial assistance to establish FLS in their localities.

Conclusion

Nearly half a billion people will reach retirement age during the next 20 years. IOF has developed Capture the Fracture because this is the single most important thing that can be done to directly improve patient care, of both women and men, and reduce the spiralling fracture-related care costs worldwide.

Keywords: Capture the Fracture, Coordinator-based, FLS, Fracture Liaison Service, Fracture prevention, Fragility fracture

The International Osteoporosis Foundation Capture the Fracture Campaign

In 2012, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) launched the Capture the Fracture Campaign [1, 2]. Capture the Fracture is intended to substantially reduce the incidence of secondary fractures throughout the world. This will be delivered by establishment of a new standard of care for fragility fracture sufferers, whereby health care providers always respond to the first fracture to prevent the second and subsequent fractures. The most effective way to achieve this goal is through implementation of coordinator-based, post-fracture models of care. Exemplar models have been referred to as ‘Fracture Liaison Services’ (United Kingdom [3–7], Europe [8, 9] and Australia [10–12]), ‘Osteoporosis Coordinator Programs’ (Canada [13, 14]) or ‘Care Manager Programs’ (USA [15, 16]). For the purposes of this position paper, they will be referred to as Fracture Liaison Services (FLS).

During the first 10 years of the twenty-first century—the first Bone and Joint Decade [17]—considerable progress was made in terms of establishment of exemplar FLS in many countries [1] and the beginning of inclusion of secondary fracture prevention into national health policies [18–26]. However, FLS are currently established in a very small proportion of facilities that receive fracture patients worldwide, and many governments are yet to create the political framework to support funding of new services. The goal of Capture the Fracture is to facilitate adoption of FLS globally. This will be achieved by recognising and sharing best practice with health care professionals and their organisations, national osteoporosis societies and the patients they represent, and policymakers and their governments. This position paper describes why Capture the Fracture is needed and precisely how the campaign will operate over the coming years. IOF believes this is the single most important thing that can be done to directly improve patient care, for women and men, and reduce spiralling fracture-related health care costs worldwide.

The need for a global campaign

Half of women and a fifth of men will suffer a fragility fracture in their lifetime [23, 27–29]. In year 2000, there were an estimated 9 million new fragility fractures including 1.6 million at the hip, 1.7 million at the wrist, 0.7 million at the humerus and 1.4 million symptomatic vertebral fractures [30]. More recent studies suggest that 5.2 million fragility fractures occurred during 2010 in 12 industrialised countries in North America, Europe and the Pacific region [31] alone, and an additional 590,000 major osteoporotic fractures occurred in the Russian Federation [32]. Hip fracture rates are increasing rapidly in Beijing in China; between 2002 and 2006 rates in women rose by 58 % and by 49 % in men [33]. The costs associated with fragility fractures are currently enormous for Western populations and expected to dramatically increase in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East as these populations age:

In 2005, the total direct cost of osteoporotic fractures in Europe was 32 billion EUR per year [34], which is projected to rise to 37 billion EUR by 2025 [35]

In 2002, the combined cost of all osteoporotic fractures in the USA was 20 billion USD [36]

In 2006, China spent 1.6 billion USD on hip fracture care, which is projected to rise to 12.5 billion USD by 2020 and 265 billion USD by 2050 [37]

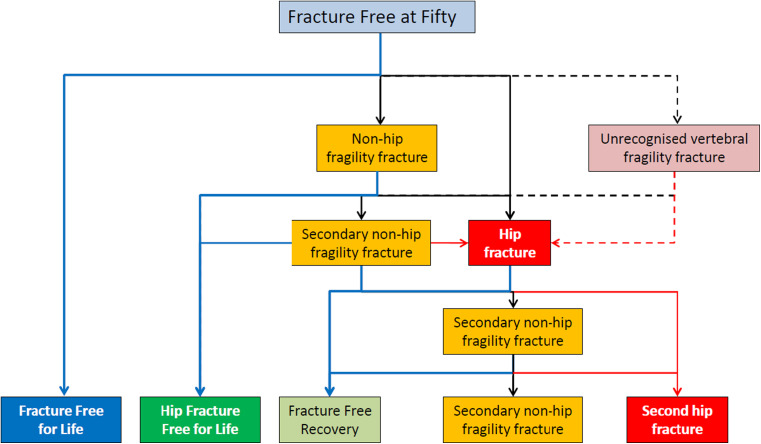

A challenge on this scale can be both daunting and bewildering for those charged with developing a response, whether at the level of an individual institution or a national health care system. Fortuitously, nature has provided us with an opportunity to systematically identify almost half of individuals who will break their hip in the future. Patients presenting with a fragility fracture today are twice as likely to suffer future fractures compared to peers that haven’t suffered a fracture [38, 39]. Crucially, from the obverse view, amongst individuals presenting with a hip fracture, almost half have previously broken another bone [40–43]. A broad spectrum of effective agents are available to prevent future fractures amongst those presenting with new fractures, and can be administered as daily [44–46], weekly [47, 48] or monthly tablets [49, 50], or as daily [51, 52], quarterly [53], six-monthly [54] or annual injections [55]. Thus, a clear opportunity presents to disrupt the fragility fracture cycle illustrated in Fig. 1, by consistently targeting fracture risk assessment, and treatment where appropriate, to fragility fracture sufferers [56].

Fig. 1.

The fragility fracture cycle (reproduced with permission of the Department of Health in England [56])

Regrettably, the majority of health care systems around the world are currently failing to respond to the first fracture to prevent the second. The ubiquitous nature of the secondary fracture prevention care gap is evident from the national audits summarised in Table 1, for both women and men [57–66]. Additionally, a substantial number of regional and local audits have been summarised in the 2012 IOF World Osteoporosis Day Report, which mirror the findings of the national audits [1]. The secondary fracture prevention care gap is persistent. A recent prospective observational study of >60,000 women aged ≥55 years, recruited from 723 primary physician practices in 10 countries, reported that less than 20 % of women with new fractures received osteoporosis treatment [67]. A province-wide study in Manitoba, Canada has revealed that post-fracture diagnosis and treatment rates have not substantially changed between 1996/1997 and 2007/2008, despite increased awareness of osteoporosis care gaps during the intervening decade [68].

Table 1.

National audits of secondary fracture prevention

| Country | No. of fracture patients | Study population | Fracture risk assessment done or risk factors identified (%) | Treated for osteoporosis (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1,829 | Minimal-trauma fracture presentations to Emergency Departments | – < 13 % had risk factors identified | –12 % received calcium | Teede et al. [57] |

| –10 % ‘appropriately investigated’ | –12 % received vitamin D | ||||

| –8 % received a bisphosphonate | |||||

| Canada | 441 | Men participating in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) with a prevalent clinical fracture at baseline | –At baseline, 2.3 % reported a diagnosis of osteoporosis | –At baseline, <1 % were taking a bisphosphonate | Papaioannou et al. [58] |

| –At year 5, 10.3 % (39/379) with a clinical fragility fracture (incident or prevalent) reported a diagnosis of osteoporosis | –At year 5, the treatment rate for any fragility fracture was 10 % (36/379) | ||||

| Germany | 1,201 | Patients admitted to hospital with an isolated distal radius fracture | 62 % of women and 50 % of men had evidence of osteoporosis | 7 % were prescribed osteoporosis-specific medication | Smektala et al. [59] |

| Italy | 2,191 | Ambulatory patients with a previous osteoporotic hip fracture attending orthopaedic clinics | No data | –< 20 % of patients had taken an antiresorptive drug before their hip fracture | Carnevale et al. [60] |

| –< 50 % took any kind of treatment for osteoporosis 1.4 years after initial interview | |||||

| Japan | 2,328 | Females suffering their first hip fracture | BMD was measured before or during hospitalisation for 16 % of patients | –19 % of patients received osteoporosis treatment in the year following fracture | Hagino et al. [61] |

| –36 % of patients receiving osteoporosis treatment during hospitalisation continued at 1 year | |||||

| Korea | 151,065 | Nationwide cohort of females with hip, spine and wrist fractures | BMD was measured for 23 % with hip fracture, 29 % with spine fracture and 9 % with wrist fracture | ≥1 approved osteoporosis treatment was received by 22 % with hip fracture, 30 % with spine fracture and 8 % with wrist fracture | Gong et al. [62] |

| Netherlands | 1,654 | Patients hospitalised for a fracture of the hip, spine, wrist or other fractures | For a sample of 208 out of 1,654 cases, GP case records were available. Of these patients, 5 % had a diagnosis of osteoporosis in the GP records | 15 % of patients received osteoporosis treatment within 1 year after discharge from hospital | Panneman et al. [63] |

| Switzerland | 3,667 | Patients presenting with a fragility fracture to hospital emergency wards | BMD was measured for 31 % of patients | 24 % of women and 14 % of men were treated with a bone active drug, generally a bisphosphonate with or without calcium and/or vitamin D | Suhm et al. [64] |

| UK | 9,567 | Patients who presented with a hip or non-hip fragility fracture | 32 % of non-hip fracture and 67 % of hip fracture patients had a clinical assessment for osteoporosis and/or fracture risk | 33 % of non-hip fracture and 60 % of hip fracture patients received appropriate management for bone health | Royal College of Physicians [65] |

| USA | 51,346 | Patients hospitalised for osteoporotic hip fracture | No data | 7 % received an anti-resorptive or bone-forming medication | Jennings et al. [66] |

The reason that the care gap exists, and persists, is multi-factorial in nature. A systematic review from Elliot-Gibson and colleagues in 2004 identified the following issues [69]:

Cost concerns relating to diagnosis and treatment

Time required for diagnosis and case finding

Concerns relating to polypharmacy

Lack of clarity regarding where clinical responsibility resides

The issue regarding where clinical responsibility resides resonates with health care professionals throughout the world. Harrington’s metaphorical depiction captures the essence of the problem [70]:

‘Osteoporosis care of fracture patients has been characterised as the Bermuda Triangle made up of orthopaedists, primary care physicians and osteoporosis experts into which the fracture patient disappears’

Surveys have shown that in the absence of a robust care pathway for fragility fracture patients, a ‘Catch-22’ scenario prevails [71]. Orthopaedic surgeons rely on primary care doctors to manage osteoporosis; primary care doctors routinely only do so if so advised by the orthopaedic surgeon; and osteoporosis experts—usually endocrinologists or rheumatologists—have no cause to interact with the patient during the fracture episode. The proven solution to close the secondary fracture prevention care gap is to eliminate this confusion by establishing a Fracture Liaison Service (FLS).

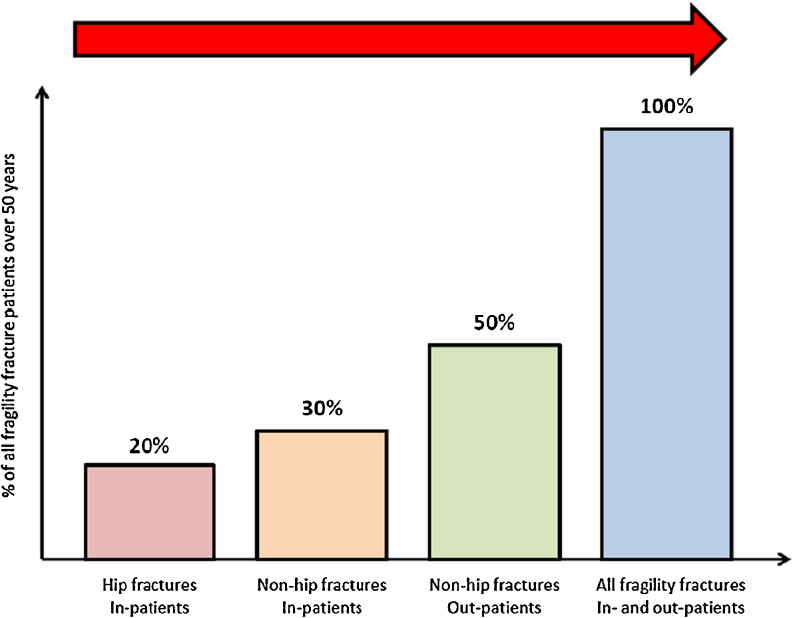

Systematic literature review of programs designed to deliver secondary preventive care reported that two thirds of services employ a dedicated coordinator to act as the link between the patient, the orthopaedic team, the osteoporosis and falls prevention services, and the primary care physician [72]. Successful and sustainable FLS report that clearly defining the scope of the service from the outset is essential. Some FLS began by focusing initially on hip fracture patients, and subsequently expanded the scope of the service until all fracture patients presenting to their institution were assessed as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Defining the scope of an FLS and expansion of fracture population assessed [1] n.b. The ultimate goal of an FLS is to capture 100 % of fragility fracture sufferers. This figure recognises that development of FLS may be incremental

The core objectives of an FLS are:

Inclusive case finding

Evidence-based assessment—stratify risk, identify secondary causes of osteoporosis, tailor therapy

Initiate treatment in accordance with relevant guidelines

Improve long-term adherence with therapy

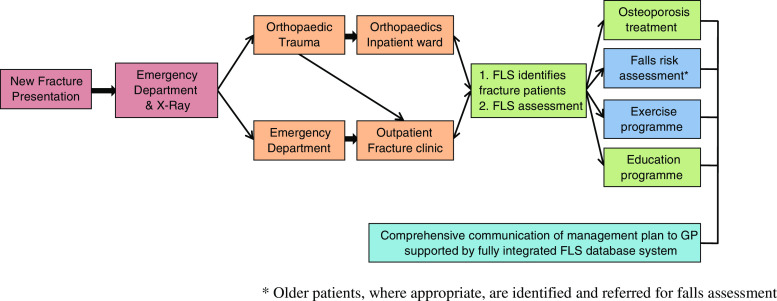

The operational characteristics of a comprehensive FLS have been described as follows [1]. The FLS will ensure fracture risk assessment, and treatment where appropriate, is delivered to all patients presenting with fragility fractures in the particular locality or institution. The service will be comprised of a dedicated case worker, often a clinical nurse specialist, who works to preagreed protocols to case-find and assess fracture patients. The FLS can be based in secondary or primary care and requires support from a medically qualified practitioner, be they a hospital doctor with expertise in fragility fracture prevention or a primary care physician with a specialist interest. The structure of a hospital-based FLS in the UK was presented in a national consensus guideline on fragility fracture care as shown in Fig. 3 [73].

Fig. 3.

The operational structure of a hospital-based Fracture Liaison Service [73] Asterisk (*) older patients, where appropriate, are identified and referred for falls assessment

FLS have been established in a growing number of countries including Australia [11, 12, 74–76], Canada [13, 77–79], Ireland [80], the Netherlands [81–84], Singapore [26], Spain [85], Sweden [86, 87], Switzerland [88], the United Kingdom [3–7] and the USA [89–92]. FLS have been reported to be cost-effective by investigators in Australia [10], Canada [14, 93], the United Kingdom [94] and the USA [15], and by the Department of Health in England [95]. In 2011, the IOF published a position paper on coordinator-based systems for secondary fracture prevention [96] which was followed in 2012 by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Secondary Prevention Task Force Report [97]. These major international initiatives underscore the degree of consensus shared by professionals throughout the world on the need for FLS to be adopted and adapted for implementation in all countries. FLS serves as an exemplar in relation to the Health Care Quality Initiative of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [98]. The IOM defines quality as:

‘The degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge’

We know that secondary fracture prevention is clinically and cost-effective, but does not routinely happen. FLS closes the disparity between current knowledge and current practice.

An important component of the Capture the Fracture Campaign will be to establish global reference standards for FLS. Several systematic reviews have highlighted that a range of service models have been designed to close the secondary fracture prevention care gap, with varying degrees of success [72, 99, 100]. Having clarity on precisely what constitutes best practice will provide a mechanism for FLS in different localities and countries to learn from one another. The Capture the Fracture ‘Best Practice Framework’ described later in this position paper aims to provide a mechanism to facilitate this goal.

How Capture the Fracture works

Background

The Capture the Fracture Campaign was launched at the IOF European Congress on Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis in Bordeaux, France in March 2012. Healthcare professionals that have played a leading role in establishing FLS and representatives from national patient societies shared their efforts to embed FLS in national policy in their countries. In October 2012, the IOF World Osteoporosis Day report was devoted to Capture the Fracture [1] and disseminated at events organised by national societies throughout the world [101]. This position paper presents the aims and structure of the Capture the Fracture Campaign. A Steering Committee comprised of the authorship group of this position paper has led development of the campaign and will provide ongoing support to the implementation of the next steps.

Aims

The aims of Capture the Fracture are:

- Standards: To provide internationally endorsed standards for best practice in secondary fracture prevention. Specific components are:

- Best Practice Framework

- Best Practice Recognition

- Showcase of best practices

- Change: Facilitation of change at the local and national level will be achieved by:

- Mentoring programmes

- Implementation guides and toolkits

- Grant programme for developing systems

- Awareness: Knowledge of the challenges and opportunities presented by secondary fracture prevention will be raised globally by:

- An ongoing communications plan

- Anthology of literature, worldwide surveys and audits

- International coalition of partners and endorsers

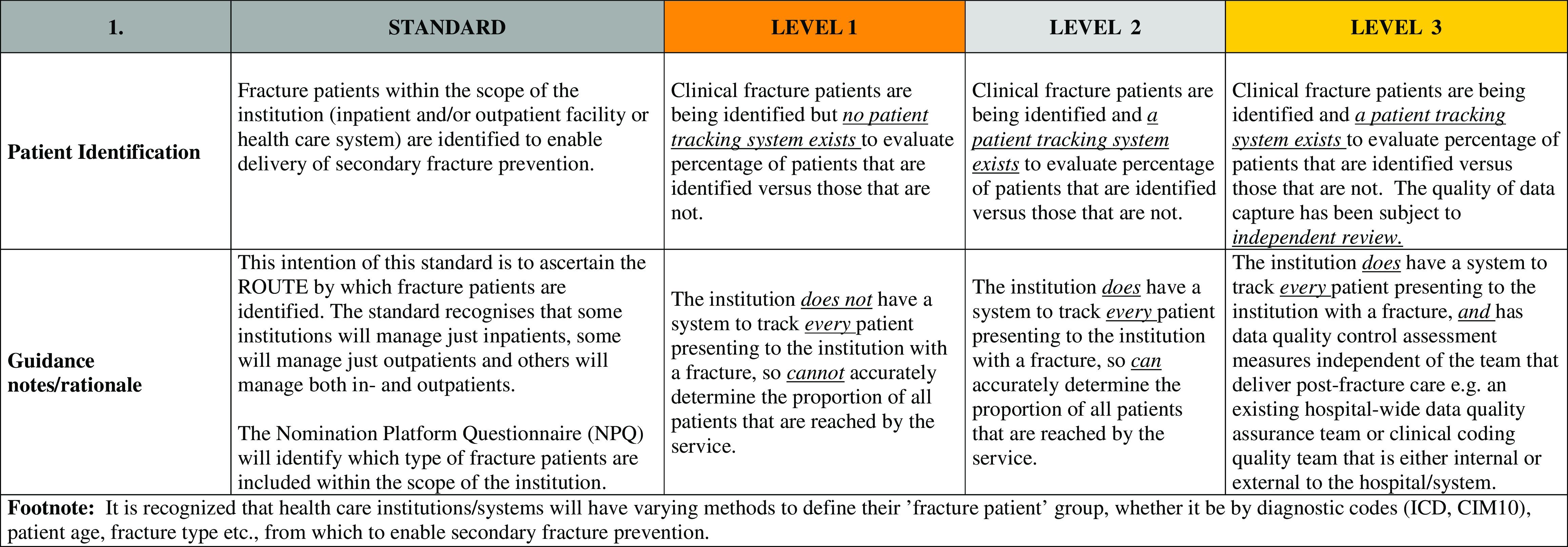

Internationally endorsed standards

The centrepiece of the Capture the Fracture Campaign is the Best Practice Framework (BPF), provided as Appendix. The BPF is comprised of 13 standards which set an international benchmark for Fracture Liaison Services. Each standard has three levels of achievement: Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3. The BPF:

Defines the essential and aspirational building blocks that are necessary to implement a successful FLS, and

Serves as the measurement tool for IOF to award ‘Capture the Fracture Best Practice Recognition’ in celebration of successful FLS worldwide

Establishing standards for health care delivery systems that have global relevance is very difficult. However, the ‘parallel evolution’ of FLS with broadly similar structure and function in many countries of the world, as described previously, suggested that a meaningful platform for benchmarking could be created. The structure of healthcare systems varies considerably throughout the world, so the context within which FLS have, and will be established in different countries may be markedly different. Accordingly, the BPF has been developed with cognisance that the scope of an FLS—and the limits of its function and effectiveness—may be constrained by the nature of health care infrastructure in the country of origin. To this end, clinical innovators who choose to submit their FLS for benchmarking by the BPF are encouraged to:

Use existing procedures as they correspond to their health care system: Existing, individual systems and procedures that are currently in place can be used to measure performance against the standards.

Meaning of the term ‘institution’: Throughout the BPF, the word ‘institution’ is used which is intended to be a generic term for: the inpatient and/or outpatient facilities, and/or health care systems for which the FLS was established to serve.

Limit applications to ‘systems’ of care: The BPF is intended for larger ‘systems’ of care, within the larger health care setting, which consist of multidisciplinary providers and deal with a significant volume of fracture patients.

- Recognise that the BPF is both achievable and ambitious: Some of the BPF standards address essential aspects of an FLS, while others are aspirational. A weight has been assigned to each standard based on how important the standard is in relation to an FLS delivering best practice care. This:

- Enables recognition of systems who have achieved the most essential elements, while leaving room for improvement towards implementing the aspirational elements

- Allows systems to achieve a standard of care, Silver for example, with a range of levels of achievement across the 13 standards

Applications will be received through a web-based questionnaire, at www.capturethefracture.org, which gathers information about the FLS and its achievements as they correspond to the Best Practice Framework. IOF staff will process submissions which will be reviewed and validated by members of the Steering Committee to generate a summary profile. This will determine the level of recognition to be assigned to the FLS as Unclassified, Bronze, Silver or Gold across four key fragility fracture patient groups—hip fracture, other inpatient fractures, outpatient fracture, vertebral fracture—and organizational characteristics. Applicants achieving Capture the Fracture Recognition will be recognised by IOF in the following ways:

Placement of the applicant’s FLS on the Capture the Fracture website’s interactive map, including the system name, location, link and programme showcase

Awarded use of the IOF-approved, Capture the Fracture Best Practice Recognition logo for use on the applicant’s websites and materials

Facilitating change at the local and national level

The Capture the Fracture website—www.capturethefracture.org—provides links to resources related to FLS and secondary fracture prevention. These include FLS implementation guides and national toolkits which have been developed for some countries. As new resources become available, the website will serve as a portal for sharing of materials to support healthcare professionals and national patient societies to establish FLS in their institutions and countries.

Further supporting the establishment of FLS, Capture the Fracture will organise a locality specific mentoring programme between sites that have achieved Best Practice Recognition and those systems that are in early stage development. An opportunity exists to create a global network to support sharing of the successes and challenges that will be faced in the process of implementing best practice. This network has the potential to contribute significantly to adoption of FLS throughout the world. During 2013, IOF intends to develop a grant programme to aid clinical systems around the world which require financial assistance to establish FLS.

Raising awareness

A substantial body of literature on secondary fracture prevention and FLS has developed over the last decade. A feature of the Capture the Fracture website is a Research Library which organises the world’s literature into an accessible format. This includes sections on care gaps and case finding; assessment, treatment and adherence; and health economic analysis.

IOF has undertaken to establish an international coalition of partners and endorsers to progress implementation of FLS. At the national level, establishment of multi-sector coalitions has played an important role in achieving prioritisation of secondary fracture prevention and FLS in national policy and reimbursement systems [1]. The Capture the Fracture website provides a mechanism to share such experience between organisations and national societies in different countries. Increasing awareness that the secondary fracture prevention care gap has been closed by implementation of FLS, and that policy and reimbursement systems have been created to support establishment of new FLS, will catalyse broader adoption of the model.

A global call to action

During the next 20 years, 450 million people worldwide will celebrate their 65th birthday [102]. As a result, in the absence of systematic preventive intervention, the human and financial costs of fragility fractures will rise dramatically. Policymakers, professional organisations, patient societies, payers and the private sector must work together to ensure that every fracture that could be prevented is prevented. Almost half of hip fracture patients suffer a previous fragility fracture before breaking their hip, creating an obvious opportunity for intervention. However, currently, a secondary fracture prevention care gap exists throughout the world. This care gap can and must be eliminated by implementation of Fracture Liaison Services. The Capture the Fracture Campaign provides all necessary evidence, international standards of care, practical resources and a network of innovators to support colleagues globally to close the secondary prevention care gap. We call upon those responsible for fracture patient care throughout the world to implement Fracture Liaison Services as a matter of urgency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gilberto Lontro (Senior Graphic Designer, IOF), Chris Aucoin (Multimedia Intern) and Shannon MacDonald, RN (Science Coordinator, IOF) for their excellent and many contributions to development of the Capture the Fracture Campaign. We are also very grateful to the following colleagues throughout the world who have provide invaluable support in the development of the Best Practice Framework: Dr. Andrew Bunta (Own the Bone, American Orthopaedic Association, USA), Dr. Pedro Carpintero (University Hospital Reina Sofia, Cordoba, Spain), Dr. Manju Chandran (Singapore General Hospital, Singapore), Dr. Gavin Clunie (Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, UK), Professor Elaine Dennison (University of Southampton, UK), Ravi Jain (Osteoporosis Canada), Professor Stephen Kates (University of Rochester Medical Center, USA), Dr. Ambrish Mithal (Medanta Medicity, Gurgaon, India), Dr. Eric Newman (Geisinger Health System, USA), Dr. Marcelo Pinheiro (Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil), Professor Markus Seibel (The University of Sydney at Concord, Australia), Dr. Bernardo Stolnicki (Federal Hospital Ipanema, Brazil), Professor Thierry Thomas (Groupe de Recherche et d’Information sur L' Ostéoporose [GRIO], France), Dr. Jan Vaile (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia), Dr. John Van Der Kallen (John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, Australia).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Appendix. Capture the Fracture Best Practice Framework

The 13 Capture the Fracture Best Practice Standards are:

Patient Identification Standard

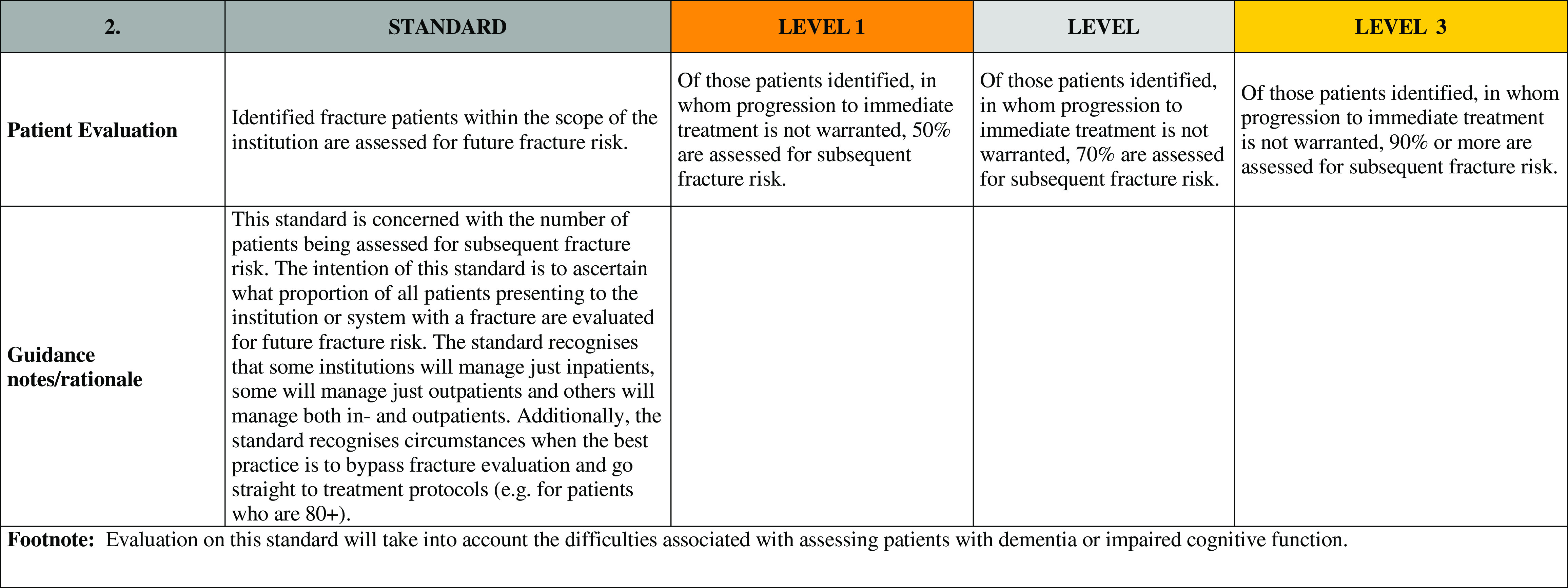

Patient Evaluation Standard

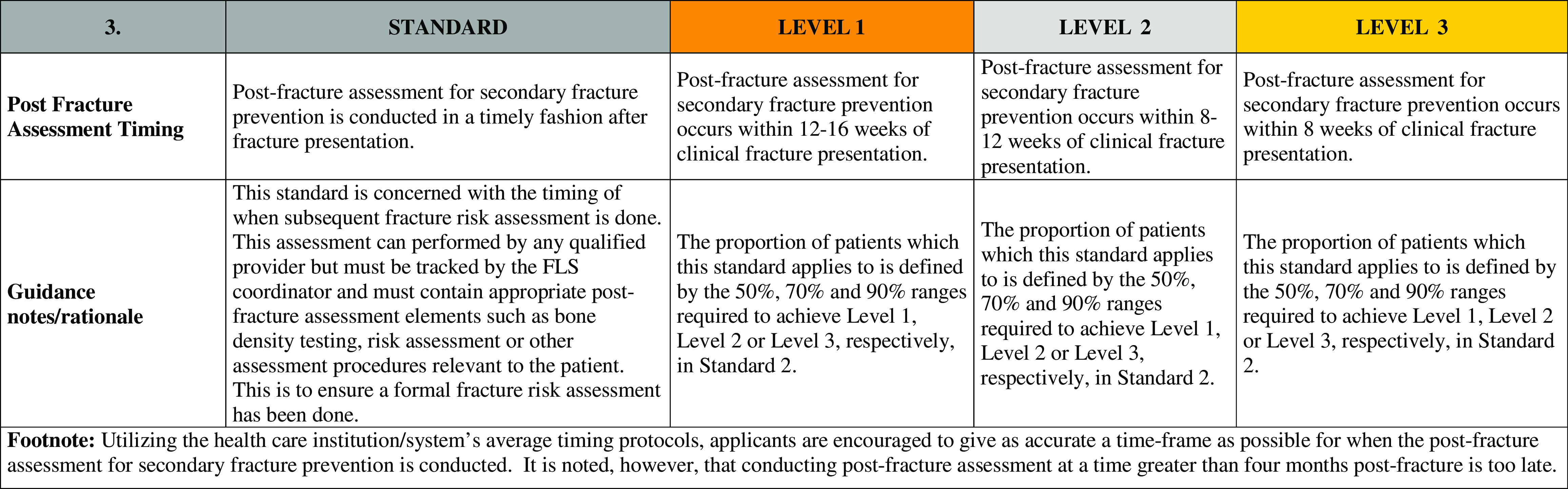

Post-fracture Assessment Timing Standard

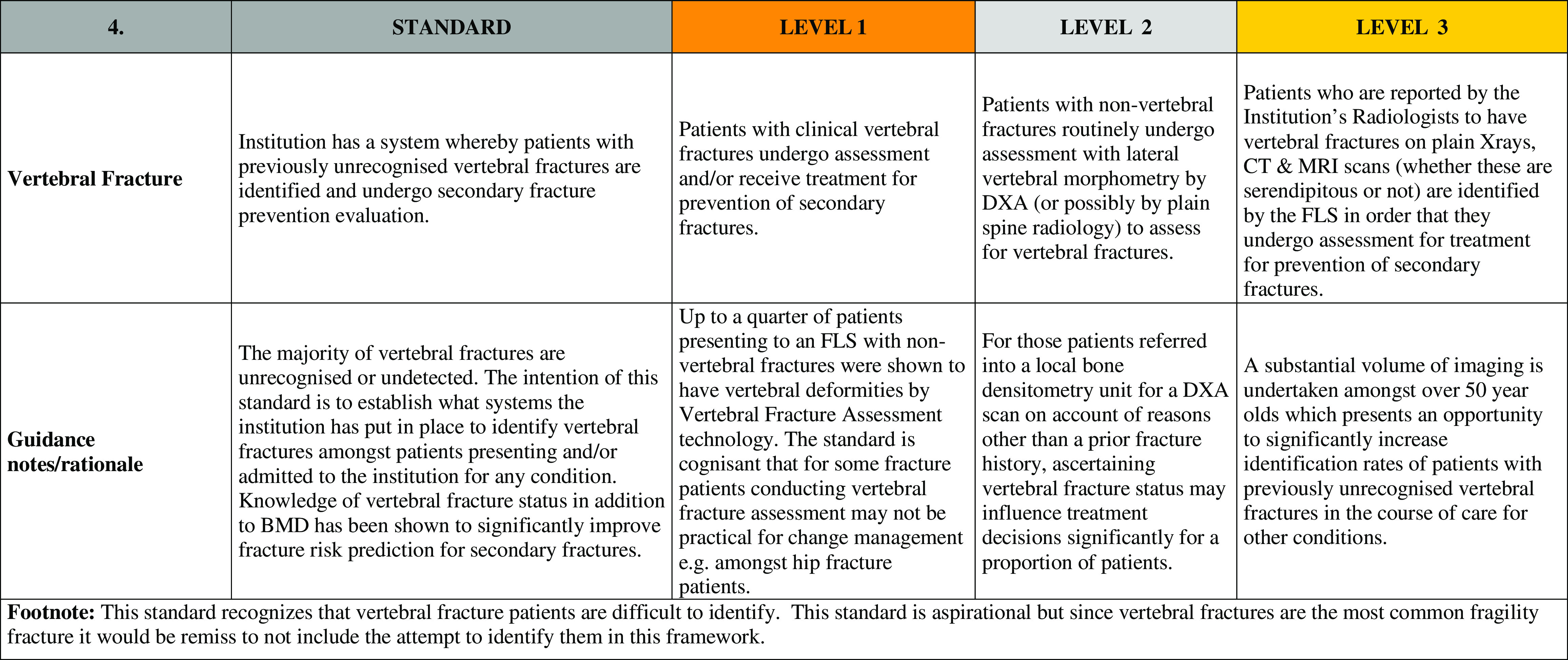

Vertebral Fracture Standard

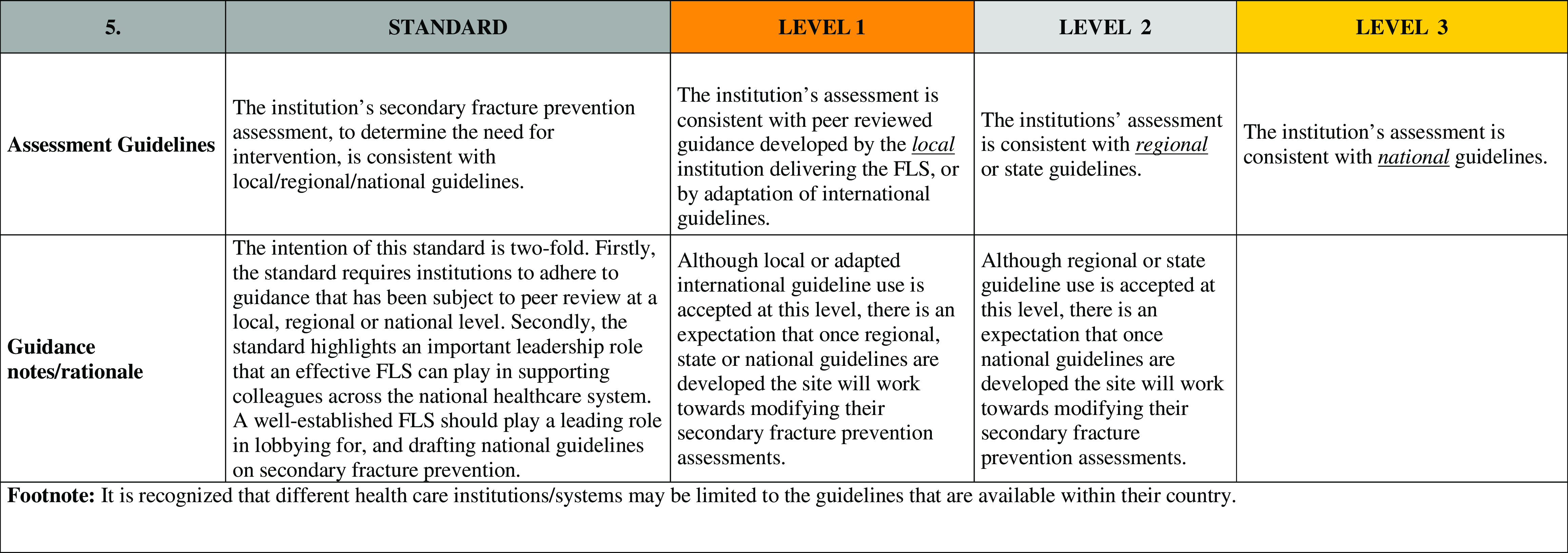

Assessment Guidelines Standard

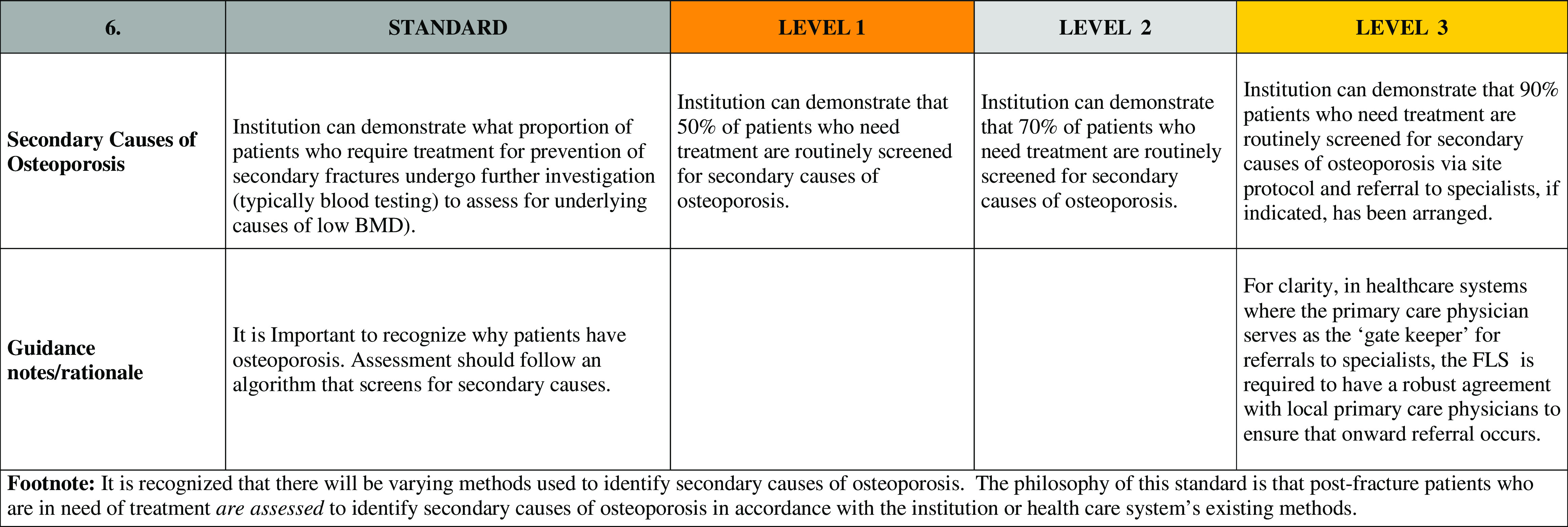

Secondary Causes of Osteoporosis Standard

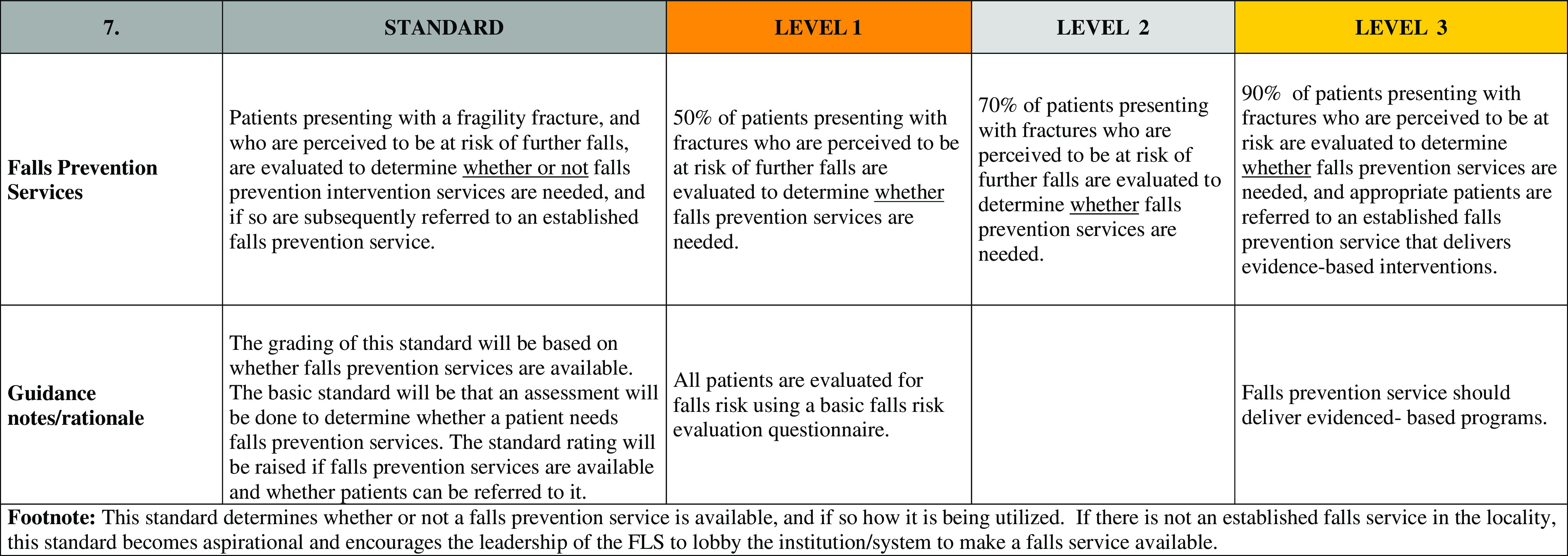

Falls Prevention Services Standard

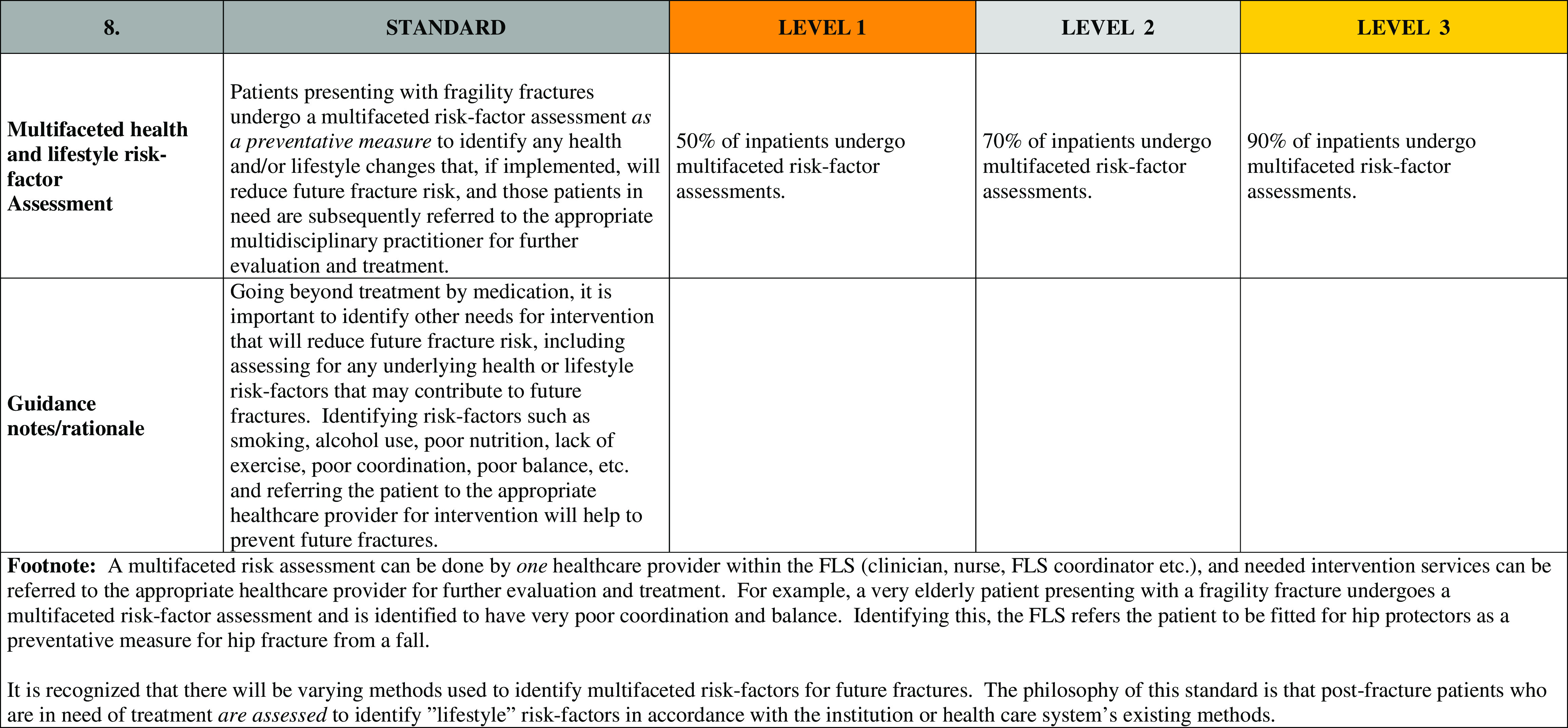

Multifaceted health and lifestyle risk-factor Assessment Standard

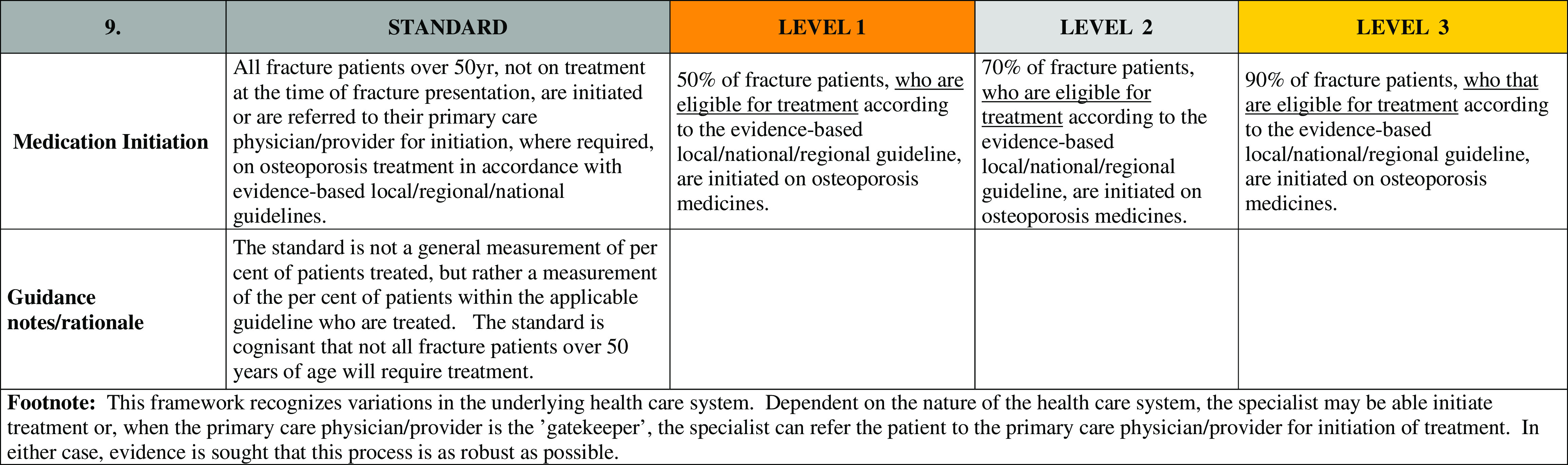

Medication Initiation Standard

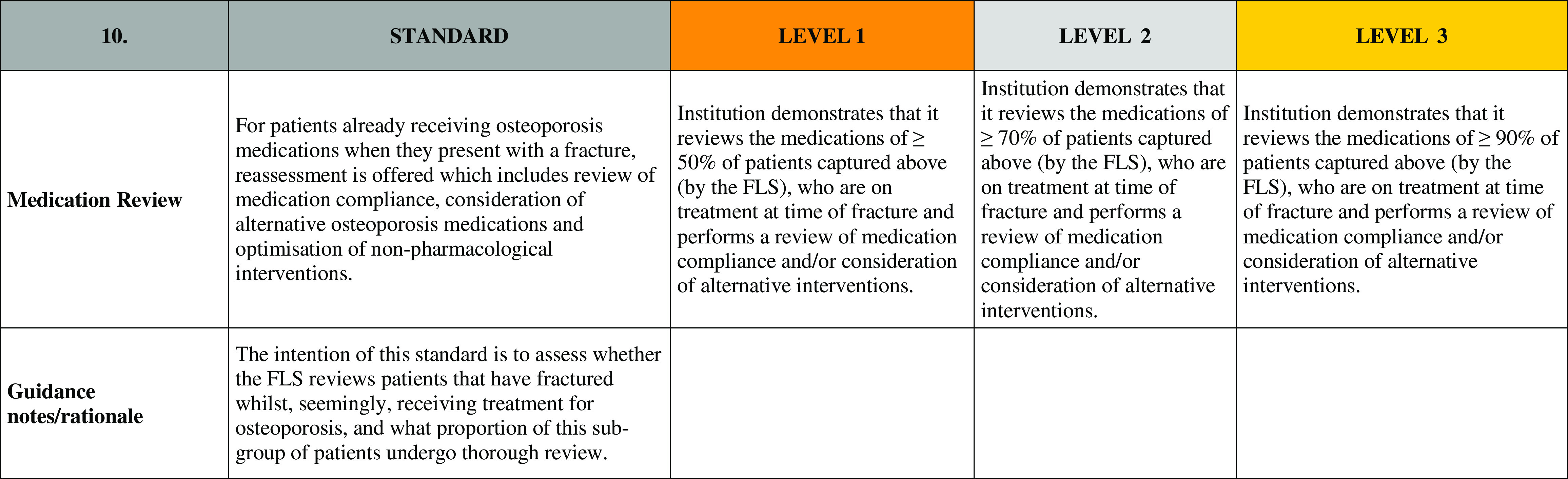

Medication Review Standard

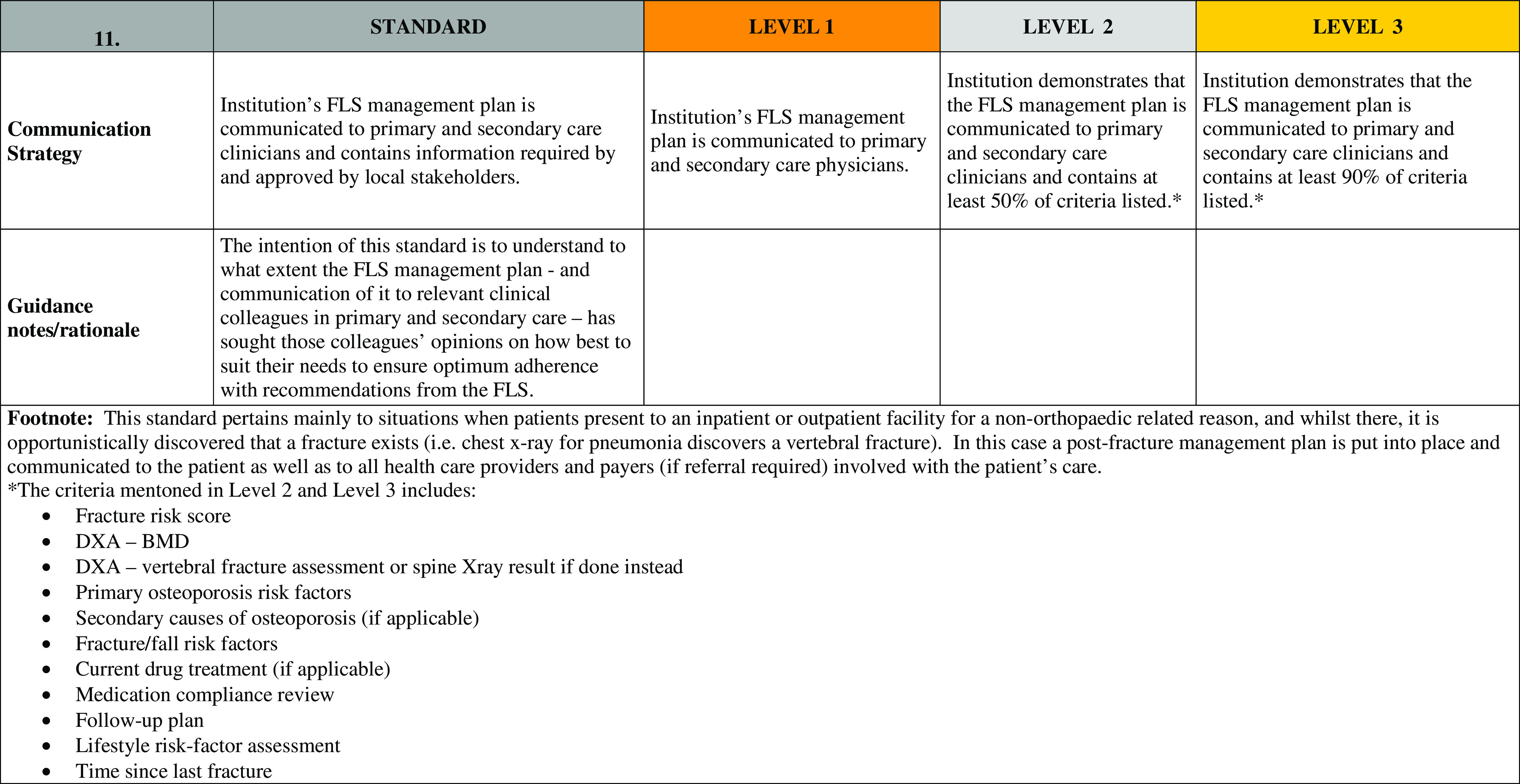

Communication Strategy Standard

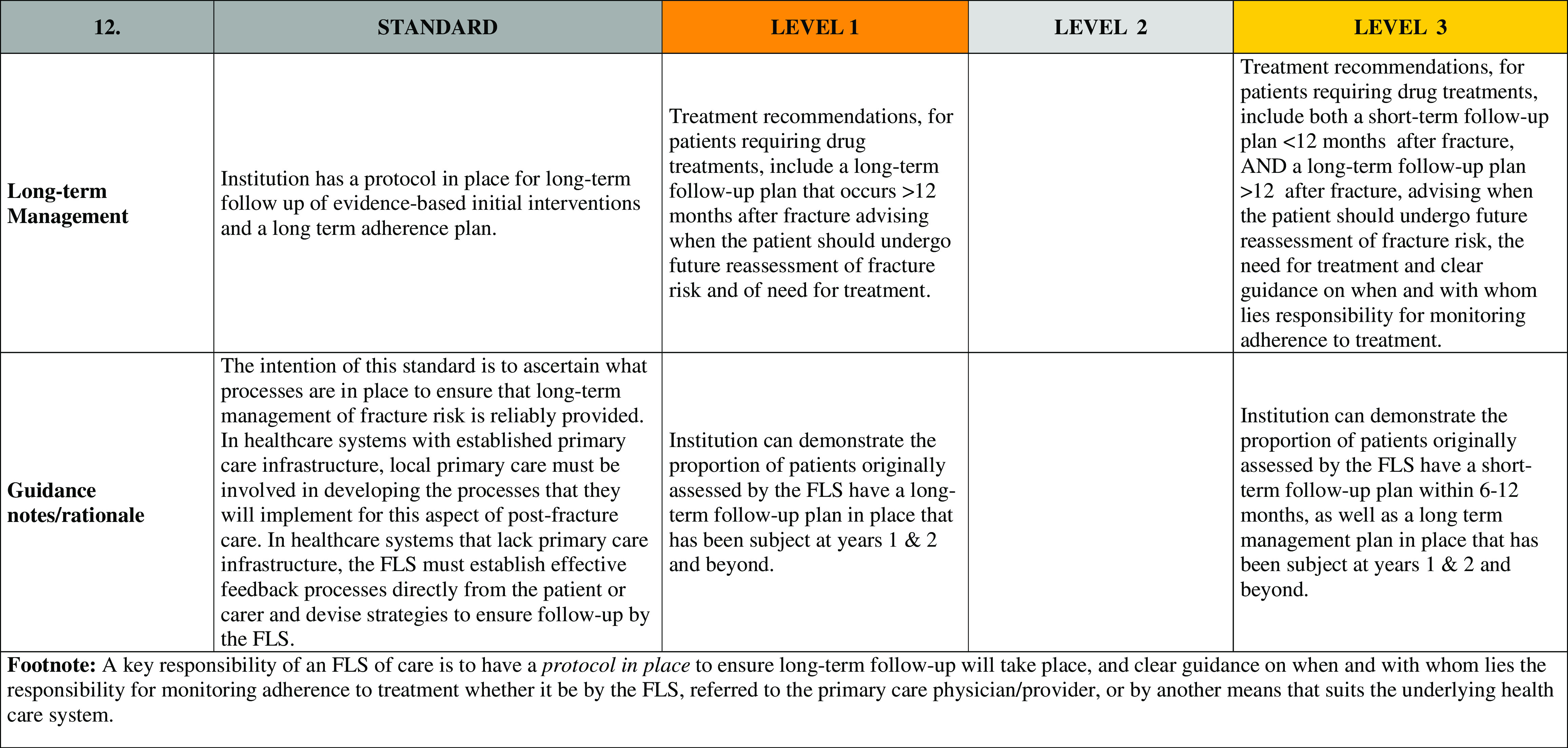

Long-term Management Standard

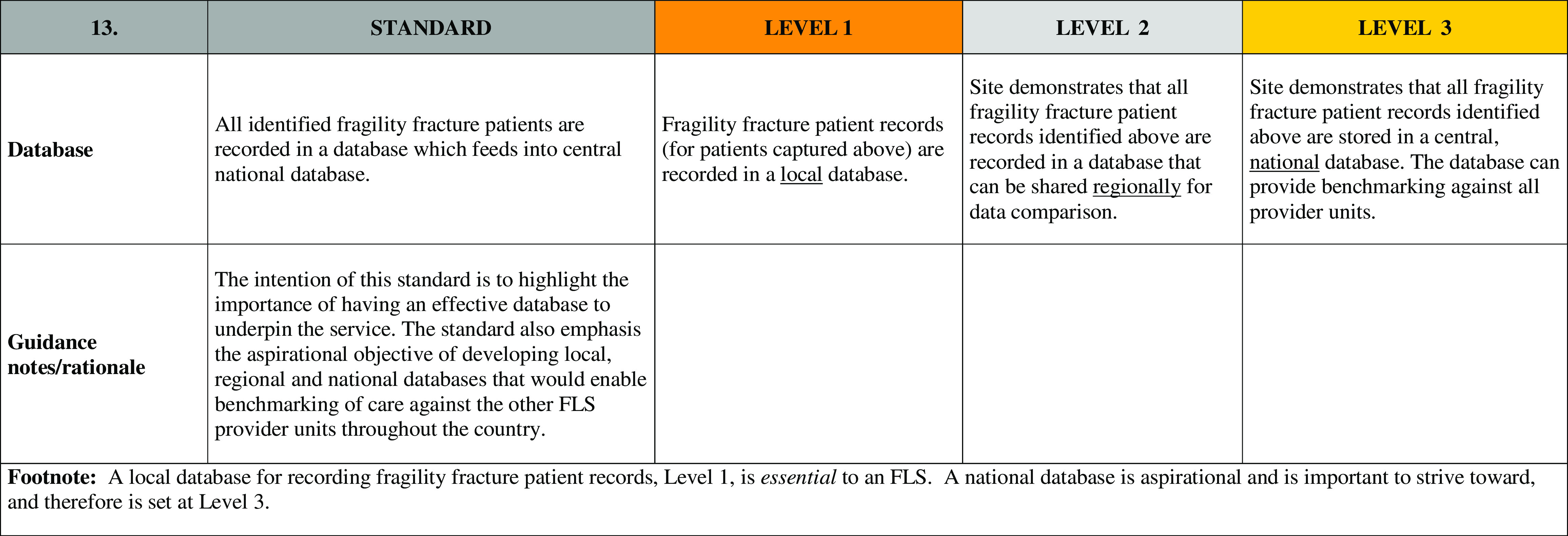

Database Standard

The BPF contains standards that are both essential and aspirational; therefore, a weight is assigned to each standard based on how essential the standard is to a successful FLS. Three levels of achievement against each standard attract scores of 1, 2 or 3 (n.b. standard 12 is dichotomous). The weighting and scoring system is as follows:

| The standards are weighted: | The scores within each standard are: |

| Essential = weight of 1 | Level 1 = 1 |

| Medium = weight of 2 | Level 2 = 2 |

| Aspirational = weight of 3 | Level 3 = 3 |

The calculator is as follows (for each standard, multiply the weight by the Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3 achieved, and add the total):

| Standard | Weight | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Achievement Level ENTER Level1/Level2/Level3 SCORE HERE | Standard Total (weight × level) | ||

| 1 | Patient Identification | 1 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 2 | Patient Evaluation | 1 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 3 | Post-fracture Assessment Timing | 2 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 4 | Vertebral Fracture | 3 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 5 | Assessment Guidelines | 3 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 6 | Secondary Causes of Osteoporosis | 3 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 7 | Falls Prevention Services | 1 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 8 | Multifaceted health and lifestyle risk-factor Assessment | 3 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 9 | Medication Initiation | 1 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 10 | Medication Review | 2 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 11 | Communication Strategy | 2 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 12 | Long-term Management | 2 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 13 | Database | 1 | x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| TOTAL Achievement Level | 0 | |||||||

It is important that the output of the framework tool is clear for health care professionals, patients and the public as it well permit meaningful comparisons both across sites nationally and globally as well as through the coming years as services evolve.

To this end, a level of recognition will be assigned to each centre as a summary profile from Unclassified through Bronze, Silver and/or Gold in up to four key fragility fracture patient groups—hip fractures, other in-patient fractures, outpatient fractures and vertebral fractures—and organizational characteristics. This will be achieved in a two-stage process.

Sites will independently complete a fracture service questionnaire and submit this to the IOF Capture the Fracture Committee of Scientific Advisors (IOF CTF CSA). The IOF CTF CSA would acknowledge receipt of the form and perform a draft grading from both administrative and clinical perspectives depending on the achievement of the IOF BPF standards within each domain. A summary profile for each domain will be made as a series of star ratings (Unclassified, Bronze, Silver and Gold).

The draft summary profile will then be fed back to the site with a request for further information if there are areas of uncertainty. On receipt of the site’s response, a suggested final summary profile will be presented to the IOF CTF CSA for approval. Importantly, should this process of recognition highlight areas for improving the fracture site questionnaire, additional recommendations will be presented to the IOF CFA CSA and, if approved, an updated version of the questionnaire will be hosted on the website for future sites to complete. Through this iterative clinically led process, the IOF BPF will remain responsive to changes in clinical practice globally as well as retain key attributes that permit meaningful comparisons in service excellence globally.

The details of the 13 standards are provided below with explanatory guidance:

Footnotes

IOF Fracture Working Group members include: Åkesson K (chair), Boonen S (Leuven, Belgium), Brandi ML (Florence, Italy), Cooper C (Oxford, UK), Dell R (Downey, USA) co-opted, Goemaere S (Gent, Belgium), Goldhahn J (Basel, Switzerland), Harvey N (Southampton, UK), Hough S (Cape Town, South Africa), Javaid MK (Oxford, UK), Lewiecki M (Albuquerque, USA), Lyritis G (Athens, Greece), Marsh D (London, UK), Napoli N (Rome, Italy), Obrant K (Malmo, Sweden), Silverman S (Beverly Hills, USA), Siris E (New York, USA) and Sosa M (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain)

This position paper was endorsed by the Committee of Scientific Advisors of IOF.

References

- 1.International Osteoporosis Foundation (2012) Capture the Fracture: a global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. http://www.worldosteoporosisday.org/ Accessed 17 Dec 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.International Osteoporosis Foundation (2012) Capture the Fracture: break the worldwide fragility fracture cycle. http://www.osteofound.org/capture-fracture Accessed 1 Nov 2012

- 3.McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C. The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:1028–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1507-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright SA, McNally C, Beringer T, Marsh D, Finch MB. Osteoporosis fracture liaison experience: the Belfast experience. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:489–490. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clunie G, Stephenson S. Implementing and running a fracture liaison service: an integrated clinical service providing a comprehensive bone health assessment at the point of fracture management. J Orthop Nurs. 2008;12:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.joon.2008.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Premaor MO, Pilbrow L, Tonkin C, Adams M, Parker RA, Compston J. Low rates of treatment in postmenopausal women with a history of low trauma fractures: results of audit in a Fracture Liaison Service. QJM. 2010;103:33–40. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace I, Callachand F, Elliott J, Gardiner P. An evaluation of an enhanced fracture liaison service as the optimal model for secondary prevention of osteoporosis. JRSM Short Rep. 2011;2:8. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2010.010063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudou L, Gerbay B, Chopin F, Ollagnier E, Collet P, Thomas T. Management of osteoporosis in fracture liaison service associated with long-term adherence to treatment. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2099–2106. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huntjens KM, van Geel TA, Blonk MC, Hegeman JH, van der Elst M, Willems P, et al. Implementation of osteoporosis guidelines: a survey of five large fracture liaison services in the Netherlands. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2129–2135. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1442-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper MS, Palmer AJ, Seibel MJ. Cost-effectiveness of the Concord Minimal Trauma Fracture Liaison service, a prospective, controlled fracture prevention study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:97–107. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1802-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inderjeeth CA, Glennon DA, Poland KE, Ingram KV, Prince RL, Van VR, et al. A multimodal intervention to improve fragility fracture management in patients presenting to emergency departments. Med J Aust. 2010;193:149–153. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lih A, Nandapalan H, Kim M, Yap C, Lee P, Ganda K, et al. Targeted intervention reduces refracture rates in patients with incident non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures: a 4-year prospective controlled study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:849–858. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM. Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:25–34. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sander B, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Maetzel A. A coordinator program in post-fracture osteoporosis management improves outcomes and saves costs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1197–1205. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K. Osteoporosis disease management: the role of the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 4):188–194. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene D, Dell RM. Outcomes of an osteoporosis disease-management program managed by nurse practitioners. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010;22:326–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Bone and Joint Decade (2012) Global Alliance for Musculoskeletal Health. http://bjdonline.org/ Accessed 14 Nov 2012

- 18.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2008) Alendronate (review), etidronate (review), risedronate (review), raloxifene (review) strontium ranelate and teriparatide (review) for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women. Technology Appraisal 161. NICE, London

- 19.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2010) Denosumab for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance 204. NICE, London

- 20.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture. London: NICE; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.British Geriatrics Society (2010) Best practice tariff for hip fracture—making ends meet http://www.bgs.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=700:tariffhipfracture&catid=47:fallsandbones&Itemid=307 Accessed 14 Nov 2012

- 22.Brown P, Carr W, Mitchell P (2012) Osteoporosis is a new domain in the GMS contract for 2012/13. http://www.eguidelines.co.uk/eguidelinesmain/gip/vol_15/apr_12/brown_osteoporosis_apr12.php Accessed 14 Nov 2012

- 23.Strom O, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C, McCloskey EV, et al. Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU: a report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA) Arch Osteoporos. 2011;6:59–155. doi: 10.1007/s11657-011-0060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Government (2006) PBS extended listing of alendronate for treating osteoporosis and Medicare extended listing for bone mineral density testing. In Department of Health and Ageing (ed). Canberra

- 25.PHARMAC . In: Pharmaceutical schedule. Wilson K, Bloor R, Jennings D, editors. Wellington: Pharmaceutical Management Agency; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Healthcare Group (2012) OPTIMAL (Osteoporosis Patient Targeted and Integrated Management for Active Living) Programme. https://www.cdm.nhg.com.sg/Programmes/OsteoporosisOPTIMAL/tabid/108/language/en-GB/Default.aspx Accessed 11 May 2012

- 27.van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517–522. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, on behalf of the Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) and the Committee of Scientific Advisors of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wade SW, Strader C, Fitzpatrick LA, Anthony MS (2012) Sex- and age-specific incidence of non-traumatic fractures in selected industrialized countries. Arch Osteoporos 1–2:219–227 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Lesnyak O, Ershova O, Belova K, et al. (2012) Epidemiology of fracture in the Russian Federation and the development of a FRAX model. Arch Osteoporos 1–2:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Xia WB, He SL, Xu L, Liu AM, Jiang Y, Li M, et al. Rapidly increasing rates of hip fracture in Beijing, China. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:125–129. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanis JA, Johnell O. Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:229–238. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jönsson B, Kanis JA (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos. doi:10.1007/s11657-013-0136-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Cummings SR, Melton LJ. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet. 2002;359:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Osteoporosis Foundation (2009) The Asian Audit: epidemiology, costs and burden of osteoporosis in Asia 2009. IOF, Nyon

- 38.Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA, 3rd, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721–739. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanis JA, Johnell O, De Laet C, et al. A meta-analysis of previous fracture and subsequent fracture risk. Bone. 2004;35:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallagher JC, Melton LJ, Riggs BL, Bergstrath E (1980) Epidemiology of fractures of the proximal femur in Rochester, Minnesota. Clin Orthop Relat Res 163–171 [PubMed]

- 41.Port L, Center J, Briffa NK, Nguyen T, Cumming R, Eisman J. Osteoporotic fracture: missed opportunity for intervention. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:780–784. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McLellan A, Reid D, Forbes K, Reid R, Campbell C, Gregori A, Raby N, Simpson A (2004) Effectiveness of strategies for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in Scotland (CEPS 99/03). NHS Quality Improvement Scotland, Glasgow

- 43.Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Simonelli C, Bolander M, Fitzpatrick LA. Prior fractures are common in patients with subsequent hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;461:226–230. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180534269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reginster JY, Seeman E, De Vernejoul MC, et al. Strontium ranelate reduces the risk of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: treatment of Peripheral Osteoporosis (TROPOS) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2816–2822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizzoli R, Greenspan SL, Bone G, 3rd, et al. Two-year results of once-weekly administration of alendronate 70 mg for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1988–1996. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.11.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris ST, Watts NB, Li Z, Chines AA, Hanley DA, Brown JP. Two-year efficacy and tolerability of risedronate once a week for the treatment of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:757–764. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reginster JY, Adami S, Lakatos P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of once-monthly oral ibandronate in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2 year results from the MOBILE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:654–661. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McClung MR, Zanchetta JR, Racewicz A, et al. (2012) Efficacy and safety of risedronate 150-mg once a month in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2-year data. Osteoporos Int 24:293–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Greenspan SL, Bone HG, Ettinger MP, et al. Effect of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–84) on vertebral fracture and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:326–339. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisman JA, Civitelli R, Adami S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of intravenous ibandronate injections in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2-year results from the DIVA study. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:488–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756–765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Department of Health (2010) Herald Fractures: clinical burden of disease and financial impact. Department of Health, London

- 57.Teede HJ, Jayasuriya IA, Gilfillan CP. Fracture prevention strategies in patients presenting to Australian hospitals with minimal-trauma fractures: a major treatment gap. Intern Med J. 2007;37:674–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, et al. The osteoporosis care gap in men with fragility fractures: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smektala R, Endres HG, Dasch B, Bonnaire F, Trampisch HJ, Pientka L. Quality of care after distal radius fracture in Germany. Results of a fracture register of 1,201 elderly patients. Der Unfallchirurg. 2009;112:46–54. doi: 10.1007/s00113-008-1523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carnevale V, Nieddu L, Romagnoli E, Bona E, Piemonte S, Scillitani A, et al. Osteoporosis intervention in ambulatory patients with previous hip fracture: a multicentric, nationwide Italian survey. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:478–483. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hagino H, Sawaguchi T, Endo N, Ito Y, Nakano T, Watanabe Y. The risk of a second hip fracture in patients after their first hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;90:14–21. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gong HS, Oh WS, Chung MS, Oh JH, Lee YH, Baek GH. Patients with wrist fractures are less likely to be evaluated and managed for osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2376–2380. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Panneman MJ, Lips P, Sen SS, Herings RM. Undertreatment with anti-osteoporotic drugs after hospitalization for fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:120–124. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suhm N, Lamy O, Lippuner K, OsteoCare study group Management of fragility fractures in Switzerland: results of a nationwide survey. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138:674–683. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Royal College of Physicians’ Clinical Effectiveness and Evaluation Unit (2011) Falling standards, broken promises: report of the national audit of falls and bone health in older people 2010. Royal College of Physicians, London

- 66.Jennings LA, Auerbach AD, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Lee SJ. Missed opportunities for osteoporosis treatment in patients hospitalized for hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:650–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Greenspan SL, Wyman A, Hooven FH, et al. Predictors of treatment with osteoporosis medications after recent fragility fractures in a multinational cohort of postmenopausal women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leslie WD, Giangregorio LM, Yogendran M, Azimaee M, Morin S, Metge C, et al. A population-based analysis of the post-fracture care gap 1996–2008: the situation is not improving. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1623–1629. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA, Beaton DE. Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:767–778. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Harrington J. Dilemmas in providing osteoporosis care for fragility fracture patients. US Musculoskelet Rev Touch Brief. 2006;II:64–65. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chami G, Jeys L, Freudmann M, Connor L, Siddiqi M. Are osteoporotic fractures being adequately investigated?: a questionnaire of GP & orthopaedic surgeons. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sale JE, Beaton D, Posen J, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch E. Systematic review on interventions to improve osteoporosis investigation and treatment in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2067–2082. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1544-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.British Orthopaedic Association, British Geriatrics Society (2007) The care of patients with fragility fracture, 2nd edn. British Orthopaedic Association, London

- 74.Vaile J, Sullivan L, Bennett C, Bleasel J. First Fracture Project: addressing the osteoporosis care gap. Intern Med J. 2007;37:717–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giles M, Van Der Kallen J, Parker V, Cooper K, Gill K, Ross L, et al. A team approach: implementing a model of care for preventing osteoporosis related fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2321–2328. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kuo I, Ong C, Simmons L, Bliuc D, Eisman J, Center J. Successful direct intervention for osteoporosis in patients with minimal trauma fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1633–1639. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ward SE, Laughren JJ, Escott BG, Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Beaton DE. A program with a dedicated coordinator improved chart documentation of osteoporosis after fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1127–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Majumdar SR, Beaupre LA, Harley CH, Hanley DA, Lier DA, Juby AG, et al. Use of a case manager to improve osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2110–2115. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Bellerose D, et al. Nurse case-manager vs multifaceted intervention to improve quality of osteoporosis care after wrist fracture: randomized controlled pilot study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:223–230. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ahmed M, Durcan L, O’Beirne J, Quinlan J, Pillay I. Fracture liaison service in a non-regional orthopaedic clinic—a cost-effective service. Irish Med J. 2012;105(24):26–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blonk MC, Erdtsieck RJ, Wernekinck MG, Schoon EJ. The fracture and osteoporosis clinic: 1-year results and 3-month compliance. Bone. 2007;40:1643–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huntjens KM, van Geel TC, Geusens PP, Winkens B, Willems P, van den Bergh J, et al. Impact of guideline implementation by a fracture nurse on subsequent fractures and mortality in patients presenting with non-vertebral fractures. Injury. 2011;42(Suppl 4):S39–S43. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(11)70011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Helden S, Cauberg E, Geusens P, Winkes B, van der Weijden T, Brink P. The fracture and osteoporosis outpatient clinic: an effective strategy for improving implementation of an osteoporosis guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:801–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schurink M, Hegeman JH, Kreeftenberg HG, Ten Duis HJ. Follow-up for osteoporosis in older patients three years after a fracture. Neth J Med. 2007;65:71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carpintero P, Gil-Garay E, Hernandez-Vaquero D, Ferrer H, Munuera L. Interventions to improve inpatient osteoporosis management following first osteoporotic fracture: the PREVENT project. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:245–250. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Astrand J, Thorngren KG, Tagil M, Akesson K. 3-year follow-up of 215 fracture patients from a prospective and consecutive osteoporosis screening program. Fracture patients care! Acta orthopaedica. 2008;79:404–409. doi: 10.1080/17453670710015328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Astrand J, Nilsson J, Thorngren KG (2012) Screening for osteoporosis reduced new fracture incidence by almost half: a 6-year follow-up of 592 fracture patients from an osteoporosis screening program. Acta Orthop 83(6):661–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Chevalley T, Hoffmeyer P, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. An osteoporosis clinical pathway for the medical management of patients with low-trauma fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:450–455. doi: 10.1007/s001980200053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Newman ED, Ayoub WT, Starkey RH, Diehl JM, Wood GC. Osteoporosis disease management in a rural health care population: hip fracture reduction and reduced costs in postmenopausal women after 5 years. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:146–151. doi: 10.1007/s00198-002-1336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dell RM, Greene D, Anderson D, Williams K. Osteoporosis disease management: what every orthopaedic surgeon should know. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 6):79–86. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Harrington JT, Barash HL, Day S, Lease J. Redesigning the care of fragility fracture patients to improve osteoporosis management: a health care improvement project. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:198–204. doi: 10.1002/art.21072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Madison LD, DeSantis A, Ramsey-Goldman R, Taft L, et al. An osteoporosis and fracture intervention program increases the diagnosis and treatment for osteoporosis for patients with minimal trauma fractures. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:267–274. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Majumdar SR, Lier DA, Beaupre LA, Hanley DA, Maksymowych WP, Juby AG, et al. Osteoporosis case manager for patients with hip fractures: results of a cost-effectiveness analysis conducted alongside a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archinte.169.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McLellan AR, Wolowacz SE, Zimovetz EA, Beard SM, Lock S, McCrink L, et al. Fracture liaison services for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture: a cost-effectiveness evaluation based on data collected over 8 years of service provision. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2083–2098. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Department of Health (2009) Fracture prevention services: an economic evaluation. Department of Health, London

- 96.Marsh D, Akesson K, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Boonen S, Brandi ML, et al. Coordinator-based systems for secondary prevention in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2051–2065. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:2039–2046. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2012) Crossing the quality chasm: the IOM Health Care Quality Initiative. http://www.iom.edu/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx Accessed 17 Dec 2012

- 99.Ganda K, Puech M, Chen JS, Speerin R, Bleasel J, Center JR, Eisman JA, March L, Seibel MJ (2013) Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 24:393–406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Little EA, Eccles MP. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to improve post-fracture investigation and management of patients at risk of osteoporosis. Implement Sci: IS. 2010;5:80. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.International Osteoporosis Foundation (2012) Stop at One: Make your first break your last-events. http://www.worldosteoporosisday.org/events-eng Accessed 16 Nov 2012

- 102.Global Coalition on Aging (2012) Welcome to the Global Coalition on Aging. http://www.globalcoalitiononaging.com/ Accessed 16 Nov 2012