Abstract

The encounter between registered nurses and persons in need of healthcare has been described as fundamental in nursing care. This encounter can take place face-to-face in physical meetings and through meetings via distance-spanning technology. A strong view expressed in the literature is that the face-to-face encounter is important and cannot entirely be replaced by remote encounters. The encounter has been studied in various healthcare contexts but there is a lack of studies with specific focus on the encounter in home-based nursing care. The aim of this study was to explore the encounter in home-based nursing care based on registered nurses’ experiences. Individual interviews were performed with 24 nurses working in home-based nursing care. The transcribed interviews were analyzed using thematic content analysis and six themes were identified: Follows special rules, Needs some doing, Provides unique information and understanding, Facilitates by being known, Brings energy and relieves anxiety, and Can reach a spirit of community. The encounter includes dimensions of being private, being personal and being professional. A good encounter contains dimensions of being personal and being professional and that there is a good balance between these. This is an encounter between two human beings, where the nurse faces the person with herself and the profession steadily and securely in the back. Being personal and professional at the same time could encourage nurses to focus on doing and being during the encounter in home-based nursing care.

Keywords: Encounters face-to-face, remote encounters, home-based nursing care, nurses, thematic content analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Home-based healthcare has increasingly become a more common model for the organization of healthcare [1-3] and this development is a challenge both for the person in need of healthcare and the healthcare professionals. In order to cater to the individual needs of each person and provide support in the home, the nurses have to meet with them and assess their needs. The traditional way to do this is when nurses are encountering and supporting the person during face-to-face home visits [4] or the person is asked to visit the healthcare centres. The use of distance-spanning technology is an alternative way for encounters which is increasingly used in healthcare at home [5]. When using distance-spanning technology in home-based healthcare, persons in need of healthcare [6] and general practitioners [7] have expressed the importance of personal encounters (i.e. face-to-face encounters) and that the distance-spanning technology cannot replace the personal encounter. These findings are in line with many other studies and this emphasizes the need for an increased understanding of the encounter.

BACKGROUND

The nursing discipline is shaped by several defining characteristics and the integration of these defines the nursing perspective. A nursing perspective is known by exploring nursing as a human science, with a practice orientation, caring tradition, and a health orientation [8]. An investigation [9] about nursing as an art shows encounter as a fundamental category and it is in the encounter that the work of art is created. The encounter is described as being on the same wavelength but not being controlled by each other. The encounter is characterized by solidarity and closeness and in the encounter one is “naked” and completely open to what is happening. The encounter means to enter by oneself and the encounter might entails fear of vulnerability [9]. The first nurse-patient encounter should not be seen as an isolated nursing intervention but rather the start of an ongoing professional caring relationship [10]. The prerequisite for the relationship between the person and the nurse has changed as the healthcare changed with shorter interpersonal encounters [11].

A theory of caring and uncaring encounters has been developed by Halldórsdóttir [12]. She proposed a continuum of caring and uncaring dimensions and later five modes of being with another. The life-destroying mode is when the care provider depersonalizes the recipient and increases the recipient’s vulnerability by humiliating approaches. The life-restraining mode is when the provider is perceived as insensitive or indifferent towards the recipient. The life-neutral mode is when the provider is not perceived to affect well-being, neither positively nor negatively. The life-sustaining mode is when the provider acknowledges the personhood of the recipient by supporting, encouraging and reassuring, which affect well-being positively but does not increase the perceived sense of healing. The life-giving mode is when the provider of professional human service affirms the personhood of the recipient by connecting in a caring way, thus relieving vulnerability and making the recipient stronger and potentiating perceived well-being, healing and learning. Bailey [13] discussed that the caring dimensions in Halldórsdóttir’s theory could serve as a means to preserve dignity for vulnerable persons. Nurses awareness of the person’s suffering can be considered a precondition for a genuine encounter and the encounter might increase the person’s feeling of dignity and human dignity is confirmed a great degree during encounters [9]. When persons were asked to talk about caring and uncaring encounters with caregivers they described uncaring encounters before caring encounters. It has also been described that uncaring encounters are not helpful for the person [13]. The encounters with nurses in palliative care have been described as a contribution to a person’s sense of security, comfort and well-being [14]. This further indicates the importance of knowledge about encounters in healthcare and nursing care in order to encounter the person with dignity and support the health and well-being. According to Gallagher [15] there are opportunities for dignity promotion since dignity arises in every nurse-person encounter.

The encounter in healthcare has been studied in different contexts. The home care encounters in a multicultural context are described as essential for creation of trust, support and consolation [16]. The ethical dilemmas have been described during the faceless encounter in telephone nursing, when nurses have to prioritize between persons they cannot see. Nurses experienced difficulties when they could not read the caller’s face and reaction as they might do in face-to-face encounters. Another dilemma was that nurses have to balancing the caller’s information needs with nurse’s professional responsibility [17]. A study [18] shows that nurses have a theoretical knowledge of good caring encounters but need more training to develop their encounters with persons and the professional role in nursing homes. Another study [19] shows that the encounter between nurses and persons with severe dementia could create meaningfulness for both parties when the encounter confirmed the person’s and the nurse’s identity and nurse’s professional role.

Nåden and Eriksson [9] expressed the encounter has been studied more in terms of technical aspects. Studies in this field also often include a mix of healthcare professionals as enrolled nurses, registered nurses, physicians and healthcare managers [18, 20, 21]. An important aspect of quality of nurse-patient interactions is the interpersonal skills [22]. One aspect of that competence is knowledge about the person-nurse encounters, which is needed in order to meet the person’s nursing needs [20]. Nåden and Eriksson [9] stated that the description of the encounter is ambiguous and the encounter is often viewed in relation to confirmation. They argue that even if the encounter is an act of confirmation there is still something more. According to Westin [23] the term encounter can be viewed as relating to the terms meeting, appointment or relationship but differs as the encounter often means more personal contact that occur between people who come across and get in touch with each other.

The literature review shows that findings in several studies within nursing research touch the encounter in healthcare but there is a lack of studies with specific focus on the professional encounter from registered nurses’ and district nurses’ perspective in home-based nursing care. There are also several concepts often mentioned in connection to encounter as relationship, interaction and communication. These concepts are fundamental in our understanding of nursing care and are close and to some extent also are overlapping. Regardless of which of these concepts is in focus, the encounter is always the start of the process. The encounter in home-based nursing care can take place through face-to-face encounters and remote encounters. Through the ongoing development of distance-spanning technology the numbers of ways the professional encounter can take place is steadily increasing. The encounter is an important dimension in home-based healthcare [6, 7] and in order to promote nursing care that supports dignity, health and well-being there is a need for deeper knowledge. One way to achieve that is to draw on the experiences of nurses who work daily in home-based nursing care. The aim of the study was to explore the encounter in home-based nursing care based on registered nurses’ experiences.

METHODS

The study was conducted within the qualitative research approach using a method for interview studies. The aim was to explore the encounter through the participants’ experiences and therefore the method was found appropriate [24].

Participants and Procedure

The study was carried out in the northern part of Sweden. Healthcare managers (n=8) in four territories were contacted and gave their consent for the study. They were also asked to name those registered nurses (RNs) and district nurses (DNs) that fulfill the inclusion criteria, which was at least one year’s experience of work as a RN or DN in home-based nursing care. Information about the study was sent out to 24 RNs and 18 DNs and they were asked to participate in an interview. Of these 13 RNs and 11 DNs, all female, agreed to participate in the study. Six RNs and six DNs declined to participate and five RNs and one DN did not answer. Written and verbal information about the study and that the participation was voluntary with the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time without explanation was given. Assurance was given that the presentation of the findings would be performed in such a way that none of individuals could be recognized by others. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden (Dnr 2010-224-31M).

Context

The four chosen territories represent three remote areas and one city area. In the same area, both healthcare managers in primary healthcare and healthcare managers for social welfare services are responsible for home care services. This means that both the county council and the municipality were involved. The DNs were employed by the county council and they were responsible for healthcare in ordinary homes and the RNs were employed by the municipality and they were responsible for healthcare in sheltered housing e.g. residential homes. The DNs and the RNs had extensive experience of home visits as well as distance-spanning technology e.g. phone contact in daily work in home-based nursing care. They had large variation in travel distance to persons they care for (Table 1). The DNs have no staff they can delegate assignments to, while the RNs have enrolled nurses that they supervise. DNs work at a healthcare center and the policy in Sweden is that most care should be performed at the healthcare center and only for special reasons home visits should be performed and the home visits are free of charge for the person. The RNs have always the possibility to send an enrolled nurse to visit the person and report from the visit.

Table 1.

Overview of Travel Distance, Numbers of Sheltered Housing and Home Visits

| RN (n=13) | DN (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|

| One way travel distance for home visits | (n) | (n) |

| 0-54 km | 13 | 4 |

| 0-83 km | - | 2 |

| 0-100 km | - | 1 |

| 0-130 km | - | 2 |

| 0-200 km | - | 2 |

| Responsible for the numbers of sheltered housing during daytime | (n) | (n) |

| 1 | 8 | - |

| 2 | 4 | - |

| 3 | 1 | - |

| Average number of home visits per week | (n) | (n) |

| 10 | - | 2 |

| 11-20 | - | 6 |

| 21-30 | 1 | 1 |

| 31-40 | 7 | 2 |

| 41-50 | 3 | - |

| 51-60 | 1 | - |

| 120 | 1 | - |

Concepts

The conception nurse in present study includes RNs and DNs. The home includes ordinary homes and sheltered housing, and a sheltered housing in Sweden can be a residential home and a nursing home. The concept encounter constitutes a professional encounter in nursing care at home, and the encounter can take place through face-to-face encounter and remote encounter. A face-to-face encounter means a physical meeting in the same room and a remote encounter means a meeting through distance-spanning technology. Distance-spanning technology in the present study means phone, web camera and videoconference.

Data Collection and Analysis

The participants were interviewed individually and according to the participants’ wishes the interviews were carried out at the participant’s home (n=2), place of work (n=21) or at the interviewer’s office (n=1). An open interview with five areas was used (Table 2) [25]. The interview opened with: Please tell me about a situation where the encounter was crucial for the person in need of healthcare and nursing care at home. The interviewer asked follow-up questions to stimulate and elicit the participants to share their experiences to get a clearer picture for the focus areas for the interview. The interview ended with the question: If you could describe a good encounter in healthcare at home, which three words would you choose. Data was collected by the first author between October 2010 and December 2010, except for one interview which took place in March 2011. The interviews were tape-recorded and lasted for 60-90 minutes.

Table 2.

Areas for the Interviews (n=5)

| Areas |

|---|

| Situations when the encounter were crucial |

| What happens during home visits |

| Face-to-face encounter |

| Remote encounter |

| Three words describing the good encounter |

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. From the beginning the interview text from RNs was viewed as one text and the text from DNs as another text. The analysis was started, reading the text several times in order to get a sense of the whole [26]. During these readings it was clear how similar RNs and DNs described the encounter and it was only contextual differences in the texts. The interview texts were then viewed as one text and during the next reading two main areas were identified, encounter and relationship. A decision was made to divide the text according to those areas and analyze them separately. The analysis of relationship will be published elsewhere.

A thematic content analysis inspired by Berg [27] was used. The text about encounter was read several times before it was divided into meaning units and then condensed. The condensed meaning units were sorted according to similarities and differences in content. The sorting was done in several steps during the analysis process. To provide rigor in the analysis process an audit trail of each step of the analysis process was stored in NVivo 9 [28]. This made it possible to work in a systematic way and to follow the process of analyzing from the single meaning through the different steps until the final themes. In this process the groups of text at different abstraction level were compared with the raw data to ensure that the themes reflect the data. All the authors took part in the analysis process to ensure trustworthiness.

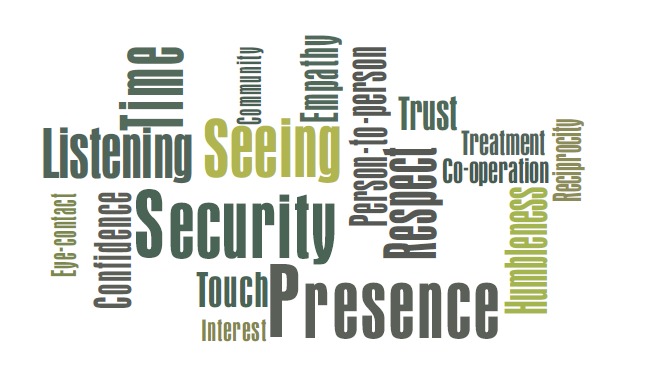

The nurses’ choice of three words describing the encounter were clustered in Swedish and later translated supported by a person fluent in Swedish and native in English. The clustering meant that words with similar meaning were brought together in one word e.g. “present” and “being here and now” were represented by the word “present”. After translation, words that occurred more than once were put into the computer program Wordle in order to generate a word cloud as a visualization of data. Fig. (1) provides a snapshot of words that occurred more than once, which reflect parts of the interviews. The word cloud gives greater prominence to words that appear more frequently.

Fig. (1).

The nurses’ choice of three words that describe the good encounter in home-based nursing care that occurred more than once. The word cloud gives greater prominence to words that appear more frequently.

RESULTS

Words Describing the Encounter

The three words the nurses chose to describe a good encounter were to large extent in congruence with the themes of the interviews. In the clustering the words security, presence, time, respect and seeing (the person) were most common (Fig. 1).

The Themes of Encounters

During the analysis six themes about the encounter in home-based nursing care were identified (Table 3). When nurses described the remote encounter, it was common that they compared with a face-to-face encounter, although they were not asked to do that.

Table 3.

Themes Found in Nurses’ Descriptions of Encounters in Home-Based Nursing Care (n=6)

| Themes |

|---|

| Follows special rules |

| Needs some doing |

| Provides unique information and understanding |

| Facilitates by being known |

| Brings energy and relieves anxiety |

| Can reach a spirit of community |

Follows Special Rules

From the nurses’ narrations it was obvious that they entered the homes as guests and followed common social rules. They entered both as private persons in a normal social encounter and as professionals, and the challenge seemed to be to find the right balance between these two.

Follow common social rules meant for example to wait for invitations or appointments, to greet and take of their coats and shoes in the hallway before entering the home. It was common to start the conversation about everyday life issues, and wait with the discussion about caring tasks until they had established the contact. To take time was essential and as a guest it is not acceptable to rush the encounter. The social aspect of the visit is never in vain since it always has a personal meaning for both the person and the nurse, and also provides information for the professional assessment.

when I come home to someone I’m the guest in their home…so I have to listen and check out what what do you want that I almost so to speak how should I behave myself, I cannot just trudge in and like here I come…but then I take a step back and so we meet half-way

(DN7:91)

The challenge to balance between being a social and professional person is to balance between being private and being close, to respect integrity and privacy. The encounter means, among other things, to reach a person-to-person level where the person can feel loved and confirmed without being private. It also means being able to share personal experiences or thoughts.

and I think it is important that you therefore should be professional but still be personal in some way…this personal encounter in the personal encounter then so I’m mainly professional…I want to be but you still become personal and I think after all that it is important to show that you are not only a district nurse but I’m also one who can think and have an opinion

(DN9:67)

and I think after all that it is important to show that you are not only a district nurse but I’m also one who can think and have an opinion

(DN9:67)

Needs Some Doing

The encounter often included doing, which had a special value and was central during home visits. Doing in the face-to-face encounter meant for example assessment of health status, support the person’s daily life, create care plans and doing follow-ups, assessing situations in the home environment, doing what the person asks the nurses to do, performing what the physician prescribes, giving injections and measuring blood pressure (Table 4). The nurses usually had to work alone and sometimes do tasks they had never done before. Nurses should also support the enrolled nurses in order to support them when they worked with persons at home.

Table 4.

Examples Given in the Interviews About what Nurses had Performed During Home Visits

| Tasks |

|---|

| Assessments e.g. assessing health status, symptoms, skin control with Norton and risk assessments in home environment |

| Measurements e.g. measuring blood pressure, blood tests and weight |

| Assistance and guidance e.g. conversations and responding to questions, give advice, give information and education, and supporting next of kin and enrolled nurses |

| Interventions e.g. facilitate and support the person’s everyday life, calm, console and relieve anxiety, treatment of wounds, massage and preventive care in home environment |

| Follow-ups e.g. care plans, ADL-status and nutrition status |

During a one-off visit, the focus was often on doing and the encounter was usually more distanced, which meant that the intention was not primarily to build a relationship. This changed when the nurse knew that she would meet the person on a regular basis. The issue of whether they should focus on building a relationship was often an ethical question for nurses in particular when they worked as a stand-in nurse. The face-to-face encounter included an initial assessment of what needed to be done and this assessment often changed during the communication. It seemed as there was a risk that too much focus on doing in the encounter meant that the person was not seen.

I notice myself that when I start as a stand-in…it feels I know myself that I'm not committed because I think that I cannot build a deeper relationship because I'm only here now…because sometimes I feel the need to continue time after…you cannot sort of begin to tear or get a human open up and then goodbye and thanks…but then I stay distanced that I have felt that one does…at least I stick only to what I should do…and I think that’s sufficiently, everything else [primary nurse] can deal with

(DN2:52)

Supervisory visits to meet the person and get a sense of their situation were made when nurses deemed it necessary but were not encouraged by their employers. In those cases the nurses often invented an excuse of some doing as measuring the blood pressure to legitimate the visit. An encounter via distance-spanning technology was sometime an alternative when doing were required, but it also had its limitations. An assessment over the phone could be a challenge in particular when the person had difficulties in explaining and specifying the problem and it was usually easier and safer to make decisions at distance when the person was known. Making decisions over the phone or via other modes of remote communication is a skill that takes time to learn and the nurses had the experience that they sometimes made a decision over the phone that they later had to revise.

but I do not think that uh…you go to somebody like that just because… you only must have a reason why you are coming

(DN6:106)

Provides Unique Information and Understanding

The nurses had the experience that face-to-face encounters could provide unique information and special understanding that was necessary for good and safe care of the person. They felt that the face-to-face encounter was necessary in order to get a holistic picture of the person and their situation at home. In comparison, the remote encounter provided less information and understanding, and the holistic picture was difficult to achieve.

Much of the important information needed in the assessments was made when being with the person, information that was perceived difficult to get without a home visit. This included, for example, information about moods and the atmosphere in the family. Trust and confidence were essential to build and the respect of the person was a prerequisite for a genuine encounter where information could be exchanged freely. Needs were identified through conversation, observation and assessment, and evaluation was done by observation. How nurses listened, spoke, used body language and physical contact were important when supporting the person. The experiences were that the nurses’ own stress could be transferred in the encounter but also that their presence could provide peace and calm. The person could read the nurses e.g. if the nurse was interested in the person and how the nurse related.

you become more confident of what you…you prescribe or assess yes in the face-to-face encounter? Yes you get it there

(RN9:81)

A unique understanding was sometimes achieved when the encounter was good. In face-to-face encounter this meant to meet at the same level i.e. nurses encounter the person with dignity at the person’s level despite differences as social class, drug addiction and sexual orientation. This could provide an understanding of the person behind all facades, frailties and different behaviors. Face-to-face encounters gave possibilities to understand the person’s background and personality i.e. take part of the person’s life story and not just present symptoms and diseases. The experience was that in order to understand the whole they had to dare to be close to the person.

but if it’s about for example you have a dressing it might be difficult for a person to describe but uh…it's impossible to do without the personal encounter…either it’s not possible to get a real idea how it looks…even if they're trying to describe…so yes it's necessary to do that visit to get a comprehensive view

(DN9:34)

The encounter at home included contact with next of kin and nurses had to understand and meet their needs too. A mutual communication between the person, next of kin and the nurses was a prerequisite for understanding where needs were identified and understood. It was common that drinking coffee or eating together, small talk and touching when accepted could provide special understanding.

they [the persons] can also have a family member or…and it’s also very important not to forget them that I’m so…they care for those closest…so that I don’t forget about them because many times there are two personal encounters during a visit

(DN6:126)

During remote encounters the conversation over the phone often gave less information and it required a skill and previous knowledge of the person to compensate. Videoconferences added more information in the interaction, but the experience was that it was still difficult to get a holistic picture since subtle information that could lead to identification of additional nursing needs was often missing. Touch was missing, the atmosphere could not be read and the sense of control was lost. Remote encounters were positive and useful when the technical quality was good, but poor sound decreased the sense of security. In situations with long travel distance between the person and the nurse the remote communication was perceived as very useful since the number of encounters could be increased. The experience of the nurses was that it was more useful with remote communication in the interaction with colleagues than when supporting a person at home.

Facilitates by Being Known

In general, nurses knew how to create a good encounter, although there was no simple recipe for a successful encounter in the home. The experience was that many things could influence the outcome of an encounter that was connected to people, the situation at a special moment and conditions on that particular day. Despite the variation in factors and situations, a common thread in a nurse’s experience was that knowing the person was an important facilitator for the encounter. Encounters when not knowing each other could lead to a wait-and-see approach while knowing the person meant knowing how to approach the person. Knowing the person was especially important during remote encounters. The experience was that an unknown nurse could frighten and make the person in need of healthcare uncertain while a known nurse could stimulate the communication and support the person in telling them about their needs. Relationships were developed when nurses showed engagement and gave a sense of caring for the person.

it depends on who it is and how well I know them if I have had they've lived here for ten years already well then I know them quite well [laughs] maybe then I can assess over the phone and if it’s something common and it also depends on what it is also

(RN7:1)

The way the encounter developed had an impact on if it was going to be a superficial or nurturing caring relationship. The ultimate encounter takes place face-to-face at home and gives opportunities to develop good relationships. Encounters that never reach a personal level could lead to harm, especially in illness and it seemed that nurses have to fight for having good encounters. With sadness they stated that encounters on a personal level were not promoted or rewarded by the management in the home-based nursing care.

it should be included in work descriptions that you will actually establish…you will have meetings, encounters and established good contact with care recipients

(RN4:74)

Brings Energy and Relieves Anxiety

During face-to-face encounters the sense of being with the person in need of care could develop and become a dominant feeling, a feeling that could influence and alter the atmosphere and mood, both of the nurses and the persons in need of care. This feeling was rare to sense in remote encounters through distance-spanning technology.

Altered atmosphere and mood meant, for example, that the person’s and the nurse’s negative emotions could turn into positive feelings during the face-to-face encounter. The encounter brings joy and energy in spite of difficult situations when emotions were shared. This sense of presence could relieve anxiety, give support and comfort to the person at home. The nurses’ willingness to meet with the next of kin together with the person with health problems was regarded as an expression of the nurse’s appreciation of them as persons, especially when nurses had to travel long distance for a home visit.

and when I went outside, I felt God what a good work I did she felt so heavenly and I felt so good I got such an energy when she was so happy that I came in and I did nothing more I just stood there talking I didn’t really do anything and…so you felt yes this is what I want to experience every day that’s why I’m a nurse

(RN1:22)

During remote encounters, the personal level and the feeling of being present were more difficult to obtain. For example, encounters via a web camera often gave a different contact and it was difficult to sense energy in the interaction. When unfamiliar with the videoconference encounter the focus was often on technical issues and appearance, which sometime created a tension between the nurse and the person in need of healthcare. Part of the body language can be read but certain cues were hard to read and situations with small talk were rare in videoconferences. Encounters via the phone were complicated by the loss of body language.

you can probably sense a mood when you get to meet a person in the same room and you can never feel that when using a computer screen absolutely not, it is important to capture…but then it may change during the encounter, it needs not be static because it is living

(RN4:55)

Can Reach a Spirit of Community

The face-to-face encounter could sometime develop to a sense of reciprocity and deeper fellowship between the nurse and the person. The experience was that this sense of community could be reached both in silence and in conversation. An increased focus on being during the encounter gave the opportunity to achieve a sense of community. The experience was that extensive work experience as a nurse increased the courage to focus on being. On the other hand, much use of remote encounters reduced the possibility of sensing a spirit of community. During encounters in the home there were periods when no words were spoken, when words were not necessary. Silence meant calm and peace where thoughts and questions could be formulated and deeper understanding occurred in the spirit of community, when silence could facilitate seeing each other’s reactions. The sense of a spirit of community could also be reached through conversation about important issues and when having something in common. Reciprocity and deeper fellowship during encounters was important for both the person with caring needs and the nurse and sharing in a spirit of community means promoting a sense of being together.

we humans are such beings who needs each other, even if I am the one that gives at that occasion, it’s still I…I get of it as a human being…simply get from another human being it’s hard to know and that could mean…it’s actually also love yes then you get love it is something like that yes… some exchange that you get then maybe you could call it…or mutual understanding….undoubtedly there are needs for me to give and to help for this particular mutual needs to be there for other human beings…you have needs to give that’s also a part, it’s not only yes not only to receive

(RN5:23)

it can be quiet but then it may also be that they start to tell you more, things are being brought up that would not have come up otherwise if we had not had this silence…that I need to know to provide good nursing care yes to give adequate care

(RN5:43)

I’ve been in encounters where you almost have not said anything because there have been no words…there haven’t been any words to use no but I have been there and been supportive and comforting in this being

(DN1:81)

Remote encounters reduced feelings of thinking and solving problems together and it was a different way of interacting than sitting next to each other. Nurses described that “real” encounters must take place in the same room. The nurses perceived that the future will bring more remote encounters in healthcare at home, but still they hoped that face-to-face encounters were possible when it is time to be cared for.

at least I want to meet people [laughs] that someone can sit next to me…me and I can talk…uh even I also can talk through video contact but it it’s different

(RN12:52)

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to explore the encounter in home-based nursing care based on registered nurses’ experiences. The analysis resulted in six themes; Follows special rules, Needs some doing, Provides unique information and understanding, Facilitates by being known, Brings energy and relieves anxiety, and Can reach a spirit of community.

The findings indicate that the encounter has a personal meaning for both the nurse and the person. It is important and fundamental in home-based nursing care and there are various dimensions of it. The importance of the encounter is emphasized by the Buber’s argumentation [29] about the interpersonal encounter. Buber described human existence as the encounter I and Thou, and he argues that all authentic life is encounter.

Viewing the findings of the present study, in the light of Halldórsdóttir’s theory [12] of different modes of nursing encounters it provides the possibility of a greater understanding. A fundamental concept in the theory is that the human encounter should not be described as a dichotomy of caring encounter/uncaring encounter, instead encounters can be viewed as a continuum of caring and uncaring dimensions. The theory includes five basic modes of being with another and the themes of the present study support the importance of being with the person in the encounter.

The five modes of caring encounters can be described as a continuum of modes from the most uncaring to the highest quality of caring mode [12]. In present study the nurses gave no examples that can be referred to the life-destroying mode, which is a destructive mode when the nurse depersonalizes the person and increases the person’s vulnerability by humiliating approaches [12]. The findings show no explicit dimensions of life-restraining mode however the nurses described the importance of taking time and not rush the encounter which could be understood as avoiding life-restraining mode. Life-restraining mode is for example when the person feels that she is bothering the nurse when asking for help which negatively affect the person’s well-being [12]. There were many examples that can be referred to the life-neutral mode, for example when the nurse focused on doing the encounter was more distanced and the intention was not primarily to build relationship. Another example was the wait-and-see approach that often occurred when the nurse and the person were strangers for each other. Most of the description of remote encounters, could be understood as a life-neutral mode, which is when the nurse is detached from the true center of the person and there is no or limited effect on the energy or life of the person. The nurse cares about routines and tasks to perform but not about the person as a person, and the person’s specific needs. In this mode the nurse is not perceived to affect the person’s well-being neither positively or negatively and relates to making and maintaining the contact [12].

The positive caring encounter was characterized by the nurse confirming the person. The nurse takes part of the person’s life story, their next of kin, symptoms and diseases. Face-to-face encounters were important to get unique information, understanding and a holistic picture. Knowing each other was also important. This could be understood as the life-sustaining mode and means that the nurse is genuinely interested in the person and is skillful and committed to the provision of personalized care, and safeguards the person’s integrity and dignity which affect well-being positively [12]. The encounter could sometime reach a spirit of community with reciprocity and deeper fellowship with the person in need of care. Being together could bring energy and relieves anxiety. This could be understood as a life-giving mode. The life-giving mode is being with each other i.e. nurses being with the person rather than working on the person. The nurse connects in a caring way, relieves vulnerability and supports the person to increase well-being, healing and learning. This mode is the truly human mode of being and is represented by healing love [12].

The findings emphasize that the good caring encounter means an encounter on a person-to-person level where the person is seen behind all facades and roles. According to Buber [29] the I and Thou encounter is a concrete encounter because the persons encounter one another in their authentic existence without any qualification or objectification of one another. Buber argues that all authentic life is encounter where I encounter Thou. A study [30] shows that the encounter should be at the level where the person is spiritually and existentially situated and when the nurse and the person work with meaning-creating of the situation, it can alleviate suffering. In present study when nurses focused on doing the encounter tended to be more distanced and this can be a threat to the I and Thou encounter. Ford [31] describes a caring encounter as “caring for is a way of doing while caring is a way of being”. Halldórsdóttir’s theory [12] presents the professional caring within nursing to involve competence, caring and connection, and is described with the metaphor the bridge. Lack of professional caring involves perceived incompetence, indifference and disconnection, and is described with the metaphor the wall. In the present study the balance between being professional and private was emphasized and the components of being professional were described in a similar way as in the Halldórsdóttir’s theory [12]. The balance meant to be professional and personal but not private, which according to Öresland, Määttä, Norberg, Winther Jörgensen and Lützén [32] is difficult. Taylor [33] points out the need to conceptualize the nurse as a person not only as a professional role, a person who shares the everyday human qualities of the persons they care for.

The present study indicates that remote encounters could sometimes be useful in home-based care, but it also provides limitations to the encounter. There were experiences were the videoconference gave more information than the phone but also that distance-spanning technology limited the possibility of having a holistic picture. However the relationship between technological support and the quality of the encounter was not the focus of the study and it is difficult to draw robust conclusions. There are examples of research that indicate that remote consultations can reach higher levels of quality in encounters then just life-neutral mode [12]. One example was a study that shown that teleconsultations could provide feelings of nursing presence in remote communication with elderly persons in nursing homes when familiarity, safety and interest were promoted [34]. Other studies indicated that distance-spanning technology could increase the number of encounter and could lead to more specialized contacts between nurses and persons in their homes [35].

It is reasonable to conclude from this study that it is not the different technologies or the mode of communication that is the main issue in the encounter with the person with a health problem and their next of kin, rather if the technology can facilitate a communication where the person and person’s needs are in focus. There is a risk that the cost efficiency will guide the development rather than the need. Buber [36] describes this risk as the modern man’s crisis. Technology was created to be a tool and support the human but the technology took the human into its service and the human became its extension. The human’s task became peripheral, to feed the technology and take care of what it produces. In order to handle this risk nurses in home-based nursing care need to learn how to use the distance-spanning technology as a tool in situations when it can serve to promote competence, caring and connection in the encounter [12].

Methodological Considerations

The aim of the study was to explore the encounter in home-based nursing care and this was done through a method for interview studies. The nurses provided rich realistic stories based on their extensive experiences of both face-to-face encounters as well as remote encounters in home-based nursing care, which provided a good and rich base for the analysis.

In order to avoid unreasonable interpretations when identifying the themes, all authors took part in the analysis and the writing of the article and alternative interpretations were tried, which increase the trustworthiness of the interpretation [27]. The presentation of the results of the three most important words describing a positive encounter as a “word cloud” should be viewed as a snapshot, indicating a direction and not an exact measurement. The transferability of the results has to be viewed from the standpoint that this is a qualitative study that is carried out in a special context [37]. However the topic of the study relates to a common human phenomenon where we all have some experience. Stake [37] stated that people make generalizations from personal or others’ experiences and this can sometimes be an unconscious process when new and old experiences are put together. This means that the reader of this article can determine whether these findings can be transferred to the context in which the reader is located and how these findings can be connected to the readers own existing knowledge.

Transferability of the results of this study is supported by the fact that parts of the findings confirm previous findings in nursing research and add some new dimensions which further develop the understanding of the encounter. The findings are also, to large extent, supported by Halldórsdóttir’s theory [12] about encounter in nursing care. We did not ask for descriptions of destructive encounters which might be an explanation as the lack of these expressions in the results compared to the theory.

CONCLUSION

The findings indicate that there are three important dimensions in the nurse-person encounter in home-based nursing care, the dimension of being private, being personal and being professional. A positive encounter contains dimensions of being personal and being professional and that there is a good balance between these. The encounter in home-based healthcare constitutes a special context where the nurse is a guest and where the balance between being personal and professional is a challenge. In a situation where more remote encounters through distance-spanning technology are encouraged, the nurse have to learn to develop work strategies that can promote competence, caring and connection in the encounter in home-based nursing care. More research has to be carried out where the perspective of the person in need of health care and the family in the encounter also is explored.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all nurses for their cooperation in this study and Tarquin Shepherd for valuable language revision of the manuscript. We are also grateful for the support received from the Department of Health Science, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Duke M, Street A. Hospital in the home: constructions of the nursing role- a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:852–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magnusson A, Severinsson E, Lützén K. Reconstructing mental health nursing in home care. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43:351–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molin R, Rom M. Utveckling i svensk hälso- och sjukvård - struktur och arbetssätt för bättre resultat. [Developments in Swedish health care - structure and procedures for better results] [cited 2012 July 9];Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting. 2009 [28 screens]. Available from: http://brs.skl.se/brsbibl/kata_documents/doc39550_1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicolaides-Bouman A, van Rossum E, Habets H, Kempen G, Knipschild P. Home visiting programme for older people with health problems: process evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:425–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shepperd S, Iliffe S. Hospital at home versus in-patient hospital care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD000365. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000356.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wälivaara BM, Andersson S, Axelsson K. Views on technology among people in need of health care at home. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68:158–69. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i2.18326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wälivaara BM, Andersson S, Axelsson K. General practitioners' reasoning about using mobile distance-spanning technology in home care and in nursing home care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meleis AI. Theoretical nursing: development and progress. 5th. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nåden D, Eriksson K. Encounter: a fundamental category of nursing as an art. Int J Hum Caring. 2002;6:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sjöstedt E, Dahlstrand A, Severinsson E, Lützén K. The first nurse-patient encounter in a psychiatric setting: discovering a moral commitment in nursing. Nurs Ethics. 2001;8:313–27. doi: 10.1177/096973300100800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hagerty BM, Patusky KL. Reconceptualizing the nurse-patient relationship. J Nurs Scholarship. 2003;35:145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halldórsdóttir H. PhD Thesis. Linköping Linköping Univ, Department of Caring Sciences. 1996. Caring and uncaring encounters in nursing and health care: developing a theory. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bailey DN. Healthcare of vulnerable populations: through the lens of Halldórsdottir's theory. Int J Hum Caring. 2010;14:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14. McKenzie H, Boughton M, Hayes L, et al. A sense of security for cancer patients at home: the role of community nurses. Health Soc Care Community. 2007;15:352–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallagher A. Dignity and respect for dignity- two key health professional values: implications for nursing practice. Nurs Ethics. 2004;11:587–99. doi: 10.1191/0969733004ne744oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lundgren SM, Holmberg M, Valmari G, Skott C. Home care encounters in a multicultural context- a diverse space for caring. Int J Hum Caring. 2011;15:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holmström I, Höglund A. The faceless encounter: ethical dilemmas in telephone nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1865–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wadensten B, Engholm R, Fahlström G, Hägglund D. Nursing staff's description of a good encounter in nursing homes. Int J Older People Nurs. 2009;4:203–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2009.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holst G, Edberg AK, Hallberg IR. Nurses' narrations and reflections about caring for patients with severe dementia as revealed in systematic clinical supervision sessions. J Aging Stud. 1999;13:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Westin L, Danielson E. Nurses' experiences of caring encounters with older people living in Swedish nursing homes. Int J Older People Nurs. 2006;1:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2006.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takman C, Severinsson EI. A description of health care professionals' experiences of encounters with patients in clinical settings. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:1368–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shattell M. Nurse-patient interaction: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:714–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Westin L. PhD Thesis. Gothenburg: Institute of Health and Care Sciences at Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg. 2008. Encounters in nursing homes: experiences from nurses, residents and relatives. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. In: Introduction: the Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. CA, USA: Thousand Oaks Sage; 2005. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kvale S, Brinkmann S. InterViews learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 2nd. Sage Publications: Los Angeles; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sandelowski M. Qualitative analysis what it is and how to begin. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:371–5. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 6th. Boston: Pearson; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richards L. Handling qualitative data: a practical guide. 2nd. London: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buber M. [Ich and Du] Ludvika: Dualis; 1990. Jag och du. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rehnsfeldt A, Eriksson K. The progression of suffering implies alleviated suffering. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18:264–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ford JS. Caring encounters. Scand J Caring Sci. 1990;4:157–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1990.tb00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Öresland S, Määttä S, Norberg A, Jörgensen M, Lützén K. Nurses as guests or professionals in home health care. Nurs Ethics. 2008;15:371–83. doi: 10.1177/0969733007088361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taylor BJ. From helper to human: a reconceptualization of the nurse as person. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:1042–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb02038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sävenstedt S, Zingmark K, Sandman PO. Being present in a distant room: aspects of teleconsultations with older people in a nursing home. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:1046–57. doi: 10.1177/1049732304267754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pols J. The heart of the matter. About good nursing and telecare. Health Care Anal. 2010;18:374–88. doi: 10.1007/s10728-009-0140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Buber M. [Das problem des menschen] Ludvika: Dualis; 2005. Människans väsen. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stake RE. In: Qualitative case studies. 3rd. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Calif: Thousand Oaks Sage; 2005. pp. 443–66. [Google Scholar]