Abstract

Objective

To explore the associations among dating violence (DV), aggression, relationship power, and depressive symptoms.

Design

A cross-sectional survey secondary analysis.

Setting

An urban, school based health center, October, 2009 through May, 2009.

Participants

Low income, adolescent girls (n= 155), ages 14–18.

Methods

Descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted to illustrate patterns and associations among variables. Key variables included depressive symptoms, DV victimization and aggression, and relationship power. We used mediation analyses to determine the direct and indirect effects among variables.

Results

Both DV victimization and aggression were reported frequently. Furthermore, DV victimization had a significant direct effect on depression and an indirect effect through relationship power. Depressive symptoms and relationship power were associated with DV aggression. Although relationship power did have a significant inverse effect on depressive symptoms, it was not through DV aggression.

Conclusions

Complex associations remain between mental health and DV; however, relationship power partially accounts for DV victimization's effect on depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms are associated with DV victimization and aggression; therefore, nurses should address relationship power in clinical and community interventions.

Keywords: dating violence, depression, relationship power, adolescent, aggression

The incidence of depression in adolescence is staggering. According to a national survey, over one-third of adolescent girls reported depressive symptoms every day for more than two consecutive weeks within the past 12 months (Eaton et al., 2010). The human cost of depression is serious and illustrated by suicide epidemiology; almost 18% of adolescent girls have seriously considered suicide, 13% have made a suicide plan, and 8% have attempted suicide within the last year (Eaton). Furthermore, depression has been linked to negative psychosocial health outcomes in adolescent girls, including low self-esteem, poor school performance, anxiety, and antisocial outcomes (DiClemente et al., 2005; Repetto, Caldwell, & Zimmerman, 2004). Depression increases health compromising behaviors such as substance use, self-injury, peer aggression, antisocial behavior, and sexual risk (DiClemente et al.; Gomes, Davis, Baker, & Servonsky, 2009; Hall-fors, Waller, Bauer, Ford, & Halpern, 2005; Hankin & Abela, 2011; Waller et al., 2006). A composite of depressive symptoms, such as feeling hopeless, may indicate a diagnosis of depression; however, symptoms must be contextualized by a clinician (Brawner & Waite, 2009).

Low relationship power and dating violence (DV) are known to contribute to depressive symptoms in women (Campbell et al., 2002; Coker, Smith, & Fadden, 2005; Filson, Ulloa, Runfola, & Hokoda, 2010; Golding, 1999). Relationship power within a sexual relationship is defined as the ability to act independently despite a partner's wishes, to control the partner's actions, and to dominate decision-making (Pulerwitz, Gortmaker, & DeJong, 2000). Since relationship power is a relative measure, low relationship power indicates that the partner has greater relationship power than the person, whereas high relationship power refers to the person having greater relationship power than the partner (Pulerwitz et al.). Relationship power is understudied within populations of low-income, urban adolescent girls (Blanc, 2001).

Dating violence can be examined as two components: DV victimization in which the person is the target of violence from a dating partner and DV aggression in which the person is the perpetrator of the violence towards a dating partner (Archer, 2000). Dating violence is unfortunately common among adolescents; one third of adolescents reported DV victimization (physical, psychological, or sexual) and more than 10% of adolescent girls and boys reported physical DV victimization within the last year (Eaton et al., 2010; Halpern, Oslak, Young, Martin, & Kupper, 2001). In this study, DV victimization is defined as physical, psychological or sexual victimization of minor and severe violence. Furthermore, DV aggression is defined as physical, psychological or sexual perpetration of minor and severe violence. Adolescents most frequently report mutual violence, DV victimization and aggression, within relationships (Prospero & Kim, 2009; Straus & Douglas, 2004). Although studies reporting factors associated with DV victimization in adolescent girls are numerous, factors associated with DV aggression in the same population are less understood. In this study, we tested the relationship of DV victimization with depressive symptoms through relationship power in urban, adolescent girls who reported having a boyfriend. In addition, we explored frequency and severity of DV aggression and its associations among relationship power and depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that in a sample of urban, low-income adolescent girls, relationship power mediates the association between DV victimization and depressive symptoms. Further, based on initial evidence, we predicted that adolescent girls' DV aggression would be related to relationship power and depressive symptoms.

Background and Significance

Adolescent DV victimization and aggression are linked to mental health outcomes, including depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and low self-esteem that often persist into adulthood (Anderson, 2002; Banyard & Cross, 2008; DiClemente et al., 2005; Howard, Wang, & Yan, 2007, 2008; Sabina & Straus, 2008). Mental and physical health repercussions associated with poor relationship conflict and DV victimization persist even after the abuse has ended (Coker, Smith, Bethea, King, & McKeown, 2000; Jones et al., 2006; Sabina & Straus; Vujeva, & Furman, 2011). Furthermore, adolescents who reported DV victimization were more likely to report suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts (Banyard & Cross; Howard et al.). Psychological DV victimization has a particularly strong, persistent link to mental health outcomes (Blasco-Ros, Sanchez-Lorente, & Martinez, 2010; Harned, 2001; Straus et al., 2009). However, often DV victimization type, including physical, psychological, and sexual, is not isolated. This poly-victimization increases risk for depressive symptoms though often is not included in research (Blasco-Ros et al.; Sabina & Straus;Sears, Byers, & Price, 2007). Additionally, economically-challenged communities have the highest rates of DV victimization and aggression (Spriggs, Halpern, Herring, & Schoenbach, 2009). Therefore, understanding DV and its relationship to mental health outcomes such as depressive symptoms in adolescents in low-income areas is a public health priority.

The mechanism explaining the association between dating violence victimization and depression is not well understood in urban, low-income adolescent girls.

Conceptual Framework of Relationship Power

Connell's Theory of Power and Gender (Connell, 1987) informed this study. Connell identified the social structures of gender power that put woman at risk for gender violence and poor health outcomes, including depression. Robust evidence supports the association between depressive symptoms and DV victimization (Coker et al., 2005; DiClemente et al., 2005; Filson et al., 2010; Golding, 1999; Sabina & Straus, 2008). Yet there is limited literature in which the researchers explore the mechanism for this linkage. However, Filson and colleagues (2010) constructed and tested a mediation model of powerlessness explaining the link between violence and depression based on Connell's (1987) work. In this work, powerlessness was conceptualized as low relationship power. Among a sample of predominantly White, college women, powerlessness partially mediated the relationship between intimate partner violence (IPV) and depression (Filson et al.). The model of Filson and colleagues serves as the conceptual model tested in this analysis.

We built on the work of Filson et al. (2010) work by extending the model to urban, low-income adolescent girls. Adolescence commonly includes the initiation of romantic relationships, and these affiliations have significant impact on individual developmental trajectories and long-term health outcomes (Collins, 2003; Furman, Low, & Ho, 2009). We applied the concepts of relationship dynamics, violence and relationship power, and how they are associated with mental health of urban, low-income adolescents who are at significant risk for depressive symptoms and DV victimization (Brawner & Waite, 2009; Silverman, Raj, & Clements, 2004; Spriggs et al., 2009; Vest, Catlin, Chen, & Brownson, 2002). Moreover, although adolescent girls perpetrate equal or greater amounts of DV aggression towards dating partners as boys, there is a paucity of information about the manner in which this influences their mental health or how it may indicate a sense of low relationship power or economic disempowerment (Banyard & Cross, 2008; Eaton et al., 2010; Prospero & Kim, 2009).

Depression and Dating Violence Aggression

Dating violence that is bi-directional between males and females, or mutual violence, is the most common pattern of violence in adolescence (Straus & Ramirez, 2007). In adult women, mutual DV has been associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, hostility, and somatization (Anderson, 2002; Prospero & Kim, 2009). A component of mutual violence, DV aggression among adolescent females, is a relatively new area of investigation, despite the fact that relational aggression, which includes DV aggression, leads to poor health and externalizing behaviors (Williams, Fredland, Han, Campbell, & Kub, 2009). The lack of examination of DV aggression among females may be because investigators assume that DV aggression in girls is only in self-defense and not harmful to either victim or perpetrator (Straus, 2006). However, in a recent meta-analysis, researchers reported on 15 articles that examined adolescent girls' use of DV aggression and found ranges of DV aggression varied between 4–79%; other studies demonstrated that DV aggression had a significant impact on victims and perpetrators (Howard et al., 2008; Williams et al.; Williams, Ghandour, & Kub, 2008). Predictors of young women's aggression were partners' use of violence, alcohol use, fathers' use of violence, and maladaptive problem solving skills (Luthra & Gidycz, 2006).

Foshee and colleagues (2007) found that DV aggression was most often in response to physical or psychological victimization or an emotional response to transgressions. Almost half of DV aggression accompanies DV victimization (Williams et al., 2008). Other investigators corroborated the rationale of emotional responses and found the most frequent motivators of violence among young women included anger and jealousy (Harned, 2001; O'Leary, Smith Slep, & O'Leary, 2007; Shorey, Meltzer, & Cornelius, 2010). Notably, a predictor of adult women's aggression towards their partners is a history of adolescent aggression (O'Leary et al.). This link supports the need for increased understanding of factors contributing to and outcomes associated with DV aggression in urban, adolescent girls.

Relationship Power

Gender-based power inequities in sexual relationships have long been assumed to be responsible for many of the psychosocial and physical disadvantages women and girls suffer (Blanc, 2001; Connell, 1987). In a review of descriptive and intervention literature, Blanc found clear and consistent associations between relationship power and violence among diverse samples. Gender-based power inequities in sexual relationships, conceptualized as relationship power, have been consistently defined as the control over one's partner and decision-making authority (Pulerwitz, Amaro, De Jong, Gortmaker, & Rudd, 2002; Pulerwitz et al., 2000). In adolescent girls, moderate to strong effects have been demonstrated between DV victimization and relationship power (Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, & Shai, 2010; Teitelman, Ratcliffe, Morales-Aleman, & Sullivan, 2008). It is important to determine if relationship power mediates the relationship between DV victimization and depressive symptoms in urban, adolescent girls as this link has not been established.

Although less frequently studied in women, DV aggression has been associated with relationship power and controlling behavior that have been conceptualized as a construct of relationship power (Follingstad, Bradley, Helff, & Laughlin, 2002; Kaura & Allen, 2004; O'Leary et al., 2007; Timmons Fritz & O'Leary, 2004). However, some evidence indicates that regardless of gender, dissatisfaction with relationship power is a stronger predictor of DV aggression than absolute relationship power (Kaura & Allen; Ronfeldt, Kimerling, & Arias, 1998). These findings in women, suggest that DV aggression may be a manifestation of frustration with relationship power, a desire to acquire relationship power or increase relationship control in adolescent girls, or serve to maintain relationship power or relationship control. Despite initial provocative, contradictory findings, there remains scant literature on relationship power in adolescents and DV, particularly as it relates to DV aggression.

In summary, the literature illustrates pressing public health concerns in adolescents related to DV victimization and depression and a clear linkage between the two. However, mechanisms explaining this relationship are unknown, leaving gaps in intervention strategies. One proposed framework suggests that the DV victimization and depression linkage works through low relationship power (Filson et al., 2010), but this has yet to be tested in low-income, urban adolescents. Additionally, there is a paucity of literature examining DV aggression in adolescent girls, despite its prevalence. Therefore, we tested the framework of Filson et al. in urban, low-income adolescent girls and then further explored associations between DV aggression, relationship power, and depressive symptoms.

Methods

Design and Participants

This study was a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data from a parent study designed to evaluate partner age and sexual risk behavior among a sample of adolescent girls (Volpe, 2010). In this descriptive analysis, we examined associations among relationship power, DV victimization and aggression, and depressive symptoms in a sample of low-income, adolescent girls. Participants were recruited in a school-based health center (SBHC) in an urban high school in the Northeastern, United States. The high school consists of grades 7–12, has a population of more than 2,000 students, and 80% of the school population qualifies for free or reduced lunch. The SBHC enrolls approximately 80% of the student population.

During the study enrollment period (November 2008–May 2009), adolescent girls who were enrolled in the SBHC were invited to learn more about a “Healthy Relationships” study by the center's staff or providers during a confidential visit. If interested, the girls were introduced to the principal investigator and were screened in a private office. The screening tool was written at a 6th grade reading level by Flesch–Kincaid reading test and included questions assessing inclusion criteria as well general health questions to mask eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria included girls who were age 14–18 and sexually active (vaginal, anal, or oral) within the past 90 days with a boyfriend. Adolescent girls in relationships that include sexual intercourse are most likely to experience DV victimization (Kaestle & Halpern, 2005). Exclusion criteria included pregnancy.

We invited 412 adolescents to participate, and 257 were ineligible. The most frequent reason for not meeting the inclusion criteria was not having a boyfriend or not currently being sexually active. The final sample included 155 participants with a mean age of 16 years, predominantly Black, and low-income. Details on the sample description are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Sample and Scales (n= 155).

| Characteristic | M (SD) | Range | N(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Age (in years) | 16.1 (SD 1.3) | 14–18 | |

| Race Category | |||

| African American/Black | 108 (69) | ||

| White | 10 (7) | ||

| Race >1 | 28 (18) | ||

| Hispanic | 30 (19) | ||

| Low Socio-economic Status | 125 (81) | ||

| Scales | |||

| Dating violence victimization | 3.7 (4.1) | 0–22 | |

| Dating violence aggression | 5.7 (5.1) | 0–22 | |

| Relationship power | 2.94 (0.57) | 1.01–4.00 | |

| • Relationship control | 3.34 (0.46) | 1.67–4.00 | |

| • Decision-making dominance | 2.09 (0.33) | 1.00–3.00 | |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.4 (5.9) | 0–27 | |

| Dating Violence Mutual Scale | |||

| Physical dating violence | |||

| • Male-only | 3 (2) | ||

| • Female-only | 38 (25) | ||

| • Mutual violence | 53 (34) | ||

| Psychological violence • Male-only | 4 (3) | ||

| • Female-only | 21 (14) | ||

| • Mutual violence | 104 (67) | ||

| Percentages rounded, may not add to 100%. |

Procedure

The university's Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study. Eligible, interested participants were consented (>18 years old) or assented (ages 14–17). Obtaining parental consent for the study would have compromised the adolescents' right to confidential reproductive health care and therefore was waived by the IRB. Participants were verbally informed about the study's purpose and procedures and received written consent or assent forms. They were asked if they had any questions or concerns before they began the survey. Participants had the option of having the survey read to them if they felt more comfortable, and one participant used this option. They were reminded they could withdraw at any time although no one selected this option.

Participants completed an anonymous, computer-assisted self-interview survey (CASI) in a private area, which improves reporting of sensitive issues, such as sexual activity (Morrison-Beedy, Carey, & Tu, 2006). Participants were given a 3-month calendar to assist with recall (Bralock & Koniak-Griffin, 2007; Jemmott, Jemmott, Fong, & Morales, 2010). The CASI was adapted from Promote Health, a survey tool that provides a written health report and a local referral list targeted to individual responses (Rhodes, Lauderdale, He, Howes, & Levinson, 2002). Promote Health has been validated with low-income and minority populations (Rhodes & Levinson, 2003; Rhodes & Pollock, 2006). Promote Health was adapted to a 6th grade reading level and pilot tested before study initiation. Participants were given the individual local referral resources and a $15 payment for participation.

Measures

Demographic variables included participants' reported age, race and ethnicity. In addition, the survey asked if the participant had ever taken part of the free lunch program, a proxy measure of socioeconomic status (Morrison-Beedy, Carey, Crean, & Jones, 2010). We assessed the length of relationships in months. Relationship duration was a categorical variable with response options of less than one month, 1–3 months, 3–6 months, greater than six months, or greater than 12 months.

Dating violence victimization and aggression were assessed using a modified version of the Conflict Tactic Scale-Short form (Straus & Douglas, 2004). Participants reported minor and severe dating violence incidents as victims and aggressors. Examples of items included, “I pushed, shoved, or slapped my partner” (DV aggression) and “my partner pushed, shoved, or slapped me” (DV victimization). Both victimization and aggression response sets included violence frequency reported as 1) never, 2) 1 time, 3) 2 times 4) 3 times and 5) 4 or more. The CTS-Short Form had concurrent validity with the CTS long form (0.77 to .89 for DV aggression and 0.65 to 0.94 for DV victimization), which is the most common scale used in DV research (Straus & Douglas). Modifications from the original CTS-SF included reduced time frame to three months and a smaller increment response set to account for shorter duration of adolescent relationships (Collins, Welsh, & Furman, 2009).

To calculate the variable DV victimization, counts of minor and severe victimization in domains of physical, psychological, and sexual violence were summed. The same was with done DV aggression. To account for frequency of poly-victimization, reports of physical, psychological, and sexual violence were added together for a composite score (Filson et al., 2010; Sabina & Straus, 2008). Mutuality typologies of DV physical and psychological violence were calculated to measure if the participants reported both, either or neither DV victimization and DV aggression (Straus & Douglas, 2004). The categorical variable had options of “no violence,” “male-only violence,” “female-only violence,” and “mutual violence” for both physical and psychological violence (Straus & Douglas).

Relationship power was measured using the Sexual Relationship Power Scale (SRPS), (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). This scale was developed in a culturally diverse sample of women to conceptualize two domains of interpersonal relationship power, relationship control and decision-making dominance within a sexual relationship. Initial items were developed through focus groups to identify important domains within relationship power (Pulerwitz et al.). The relationship control subscale (RCS) has 15 items that were used to measure the participant's agreement about their partner's command or influence within the relationship. An example of an RCS item is “when my partner and I disagree, he gets his way most of the time.” Responses for the RCS were on a 4-likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The DMDS had eight items that questioned the participant about “who had more say” in each item. An example of a DMDS item is “who usually has more say about what you do together?” Responses for the DMDS were “my partner,” “both of us equally,” or “me.” Scores for the SRPS, RCS, and DMDS were calculated according to methods recommended by Pulerwitz and colleagues. Subscale score means were calculated separately, reweighted from 1– 4, and then combined for total SRPS score. The 23-item SRPS had an internal reliability of 0.82 in this sample. Construct validity was demonstrated by significant correlations with a number of variables hypothesized to represent relationship power, such as relationship satisfaction, relationship physical and sexual violence, and similar scales, such as the Sexual Pressure Scale (Jones & Gulick, 2009; Pulerwitz et al.;Pulerwitz et al., 2002).

Depressive symptoms were measured using a modified version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D was developed by the National Institute of Mental Health Center for Epidemiologic Studies (Radloff, 1977). Nine items were chosen to assess mood frequency over the last week. An example of an item was, “I felt sad.” The participant was instructed to respond how many times over the last week she felt this way. The response selection was as follows: 0 = less than 1 day per week, 1 = 1– 2 days per week, 2 = 3–4 days per week, or 3 = 5–7 days per week. To calculate a score for depressive symptoms, two depressive symptoms items were reverse scored because they indicated happy moods. Participants' scores were totaled so that higher scores represented increased depressive symptoms. This scale has demonstrated good validity among adolescents, with sensitivity of 0.83 and specificity of 0.77 for clinical diagnosis of depression among adolescent girls using a cutoff score of 22 (Garrison, Addy, Jackson, McKeown, & Waller, 1991; Prescott et al., 1998; Radloff, 1991). The internal reliability for this scale was 0.80 in this sample.

Data Management and Analysis

Participants' survey responses were recorded by study identification numbers not associated with signed consent or assent forms to maintain anonymity. The Promote Heath survey was downloaded in groups of 20, cleaned, and stored in a password secured file.

Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe the sample. Sociodemographic factors were not included in the final model due to lack of variability in the sample and non-significance correlations with outcomes. Relationship duration was also not included in the final model as its relationship to major variables of relationship power and depressive symptoms had a significance level of greater than 0.20. The CES-D scale, measuring depressive symptoms, was log transferred to account for skewness; the skew was reduced from 1.01 to −0.45 and the log used in subsequent analysis. To address the research question and primary hypothesis, analysis was conducted using asymptotic and resampling strategies (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) for assessing indirect effects. This method estimates the total, direct, and indirect effects of the predictor variable, DV victimization, on the outcome variable depressive symptoms through a proposed mediator variable, relationship power. The indirect effect of DV victimization on depressive symptoms through relationship power was conducted through percentile-based, bias-corrected, and accelerated bootstrap confidence intervals (Preacher & Hayes). This method was selected over causal steps and the Sobel's test due to its increased statistical power to detect indirect effects of variables within a model and to account for a non-normal distribution of indirect effect (Fritz & Mackinnon, 2007; Preacher & Hayes).

Dating violence victimization directly affects depressive symptoms in adolescent girls and partially affects them through relationship power.

Exploratory analysis of adolescent girls' DV aggression was examined using the DV aggression severity score and a mutual DV typology for both physical and psychological violence. Correlations between key variables and DV aggression were also taken into account. Then a mediation analysis was proposed based on initial findings and background literature that suggested significant relationships among DV aggression, low relationship power, and depressive symptoms. Because the literature suggested that low relationship power predicted DV aggression and initial analysis of this study's variables found that low relationship power was related to both DV aggression and depressive symptoms, model 2 was tested according to Preacher and Hayes' (2008) methods as described above. The relationship of low relationship power to depressive symptoms through DV aggression was tested.

Results

The sample characteristics and scores on the scales are described in Table 1. The majority of the sample was African-American/Black (69%) and low-income (81%). The vast majority of the sample of adolescent girls reported violence aggression. Most (67%) reported mutual, psychological DV, and more than one third (34%) reported mutual, physical violence. One fourth (25%) of the sample reported female-only psychological violence, and 14% reported female-only physical violence. The majority of the sample (76%) indicated that their relationship duration was more than four months.

Bivariate Correlations

Significant bivariate correlations among major variables are presented in Table 2. Depressive symptoms were correlated with DV victimization (.304,p< .001) and DV aggression (.237,p< .001). Depressive symptoms were moderately correlated with relationship power (.434,p< .001). The RCS had a strong inverse correlation with both depressive symptoms (−.434,p< .001) and DV aggression (−.455,p< .001). However, the other subscale, DMDS, was not correlated with either depressive symptoms or DV aggression. Relationship power demonstrated a strong correlation with DV victimization (.−494,p< .001) and a moderate correlation with DV aggression (−.307,p< .001).

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations between Major Variables.

| 1 | a | b | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relationship power | — | .830*** | .783*** | −.494*** | −.307*** | −.306*** |

| a. Relationship control | .830*** | — | .303*** | −.556*** | −.455*** | −.434*** |

| b. Decision-making dominance | .783*** | .303*** | — | −.224** | −.016 | 0.039 |

| 2. Dating violence victimization | −.494*** | −.556*** | −.224** | — | .743*** | .304*** |

| 3. Dating violence aggression | −.307*** | −.455*** | −.016 | .743∗∗∗ | — | .237*** |

| 4. Depressive symptoms | −.306*** | −.434*** | 0.039 | .304*** | .237*** | — |

Note.

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001.

Relationship control and Decision-making dominance are subscales of relationship power.

Mediation Analysis

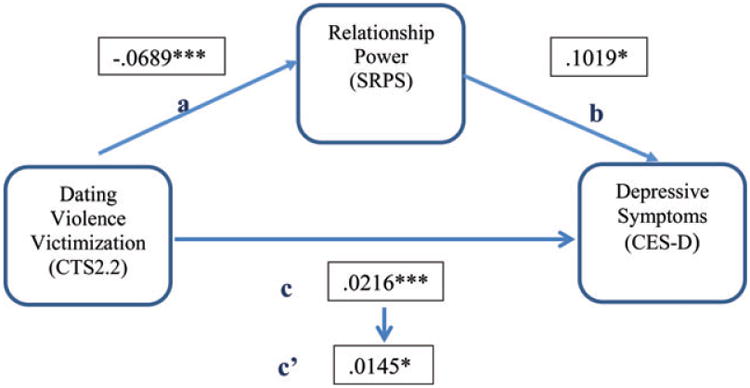

We conducted mediation analysis based on Preacher and Hayes (2008) to account for the small sample size and non-normal distribution of the indirect effect.Figure 1 illustrates indirect and direct effects between DV victimization, relationship power, and depressive symptoms. Furthermore the total model demonstrated statistical significance (R2 = 0.106,p= .000) and accounted for 11% of the variance in depressive symptoms. The indirect effect of DV victimization on depressive symptoms through relationship power was analyzed and 95% confidence was constructed around the point estimate. This was statistically significant since the confidence interval did not cross zero. The indirect effect of DV victimization on depressive symptoms through relationship power was 0.0070 (95% CI = .001–.015) (see Table 3). The first hypothesis was supported; DV victimization had an indirect effect on depressive symptoms through relationship power.

Figure 1.

Power as a Mediator of the Effects of Victimization on Depressive Symptoms.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < 001. Pathways: a = dependent variable to mediator, b = direct path of mediator to dependent variable, c = total effect of independent variable to dependent variable, c′ = direct effect of independent variable to dependent variable (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). SRPS = Sexual Relationship Power Scale; CTS2.2 = Conflict Tactic Scale-Short Form, CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Table 3. Mediation Analysis of Models.

| Direct Effect | Total Effect | Bootstrap analysis of indirect effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Path | Pathway | B | SE | B | SE | M | SE | 95% CI |

| Model: | Dating violience victimization on depressive symptoms as mediated by power | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| a | DV victimization on relationship power | −.0689*** | .0098 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| b | Relationship power on depressive symptoms | −.1019** | .0456 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| c/c′ | DV victimization on depressive symptoms | .0145** | .0064 | .0216*** | .0056 | |||

|

| ||||||||

| DV victimization on depressive symptoms through relationship power | .0068 | .0032 | [.0010, .0150] | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Model: | Relationship power on depressive symptoms as mediated by DV Aggression | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| a | Relationship power on DV aggression | −2.7669*** | .6942 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| b | DV aggression on depressive symptoms | .0074 | .0047 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| c/c′ | Relationship power on depressive symptoms | −.1328* | .0420 | −.1534*** | .0402 | |||

|

| ||||||||

| DV aggression on depressive symptoms through relationship power | −.0216 | .0162 | [−.0627, .0040] | |||||

Note.

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001.

Exploratory Analysis of Adolescent Girls Dating Violence Aggression

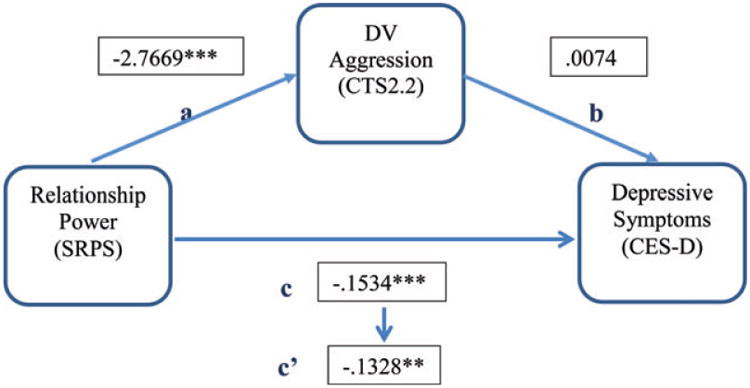

Based on initial exploration of the characteristics of DV aggression, its association with increased depressive symptoms and decreased relationship power, and the background literature, a model was tested to determine if the inverse association between relationship power and depressive symptoms had an indirect effect through DV aggression (see Fig. 2). In this mediation analysis (see Table 3), the total model was significance (R2 = 0.090,p= .000) and accounted for 9% of the variance in depressive symptoms (see Fig. 2). However, the indirect effect of low relationship power on depressive symptoms did not have a significant pathway through DV aggression.

Figure 2.

Dating Violence Aggression as a Mediator of the Effects of Relationship Power on Depressive Symptoms.

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01. Pathways: a = dependent variable to mediator, b = direct path of mediator to dependent variable, c = total effect of independent variable to dependent variable, c′ = direct effect of independent variable to dependent variable (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). SRPS = Sexual Relationship Power Scale; CTS2.2 = Conflict Tactic Scale-Short Form, CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Discussion

The relationship between mental health and DV remains complex. This analysis illustrated that not only did DV victimization directly affect depressive symptoms, but also worked indirectly through relationship power to increase depressive symptoms. These results, found within a sample of urban, low-income, adolescent girls, extended previous work that demonstrated that relationship power partially mediated the association between DV victimization and depression in college women (Filson et al., 2010). In this sample of adolescent girls, there was a larger effect size between DV victimization and depressive symptoms than found in the adult sample, but in both cases the mediation effect of relationship power was significant.

These findings are important because they increase our understanding of mental health of adolescent girls by explaining that DV victimization increases depressive symptoms partly through relationship power. The premise of relationship power as the mechanism through which violence works supports Connell's (1987) theories that society is structure in which violence, in this case DV victimization, works through interpersonal power, in this case relationship power, to influence the health of women and girls. Therefore, to decrease the risk of depression in urban adolescent girls, health initiatives should address relationship power for those in sexual relationships. Targeting relationship power in adolescent girls could capitalize on a critical stage in romantic relationship development that predicts present and individual psychosocial functioning (Collins et al., 2009). Furthermore, the RCS demonstrated a stronger association to both DV victimization and depression, than DMDS. Therefore, strategies increasing equality in relationship control should be the focus of mental health interventions for urban adolescent girls in sexual relationships.

The path between DV victimization and increased depressive symptoms was also significant, while accounting for relationship power. This supports a multifactor relationship between DV victimization and depression that includes but is not limited to relationship power. This sample's high rates of DV victimization and its relationship to depressive symptoms make identifying additional pathways a public health priority for urban adolescents. Depression in adolescents also predicts current and future relationship quality, including conflict and negative problem solving (Vujeva & Furman, 2011). Our results emphasize early intervention to identify and address depressive symptoms through both DV victimization and relationship power.

Furthermore, this sample of urban, adolescent girls reported high rates of DV aggression, physical and psychological, consistent with previous evidence (Williams et al., 2008). These findings are concerning because girls' DV aggression increases their risk for immediate injury and links to mental health status, high-risk sexual behavior, substance use, and future relationship violence for their male partners (Harned, 2001; Howard et al., 2008). In addition, this analysis adds new information to the field of DV and mental health; depressive symptoms have a moderate correlation with DV aggression. Dating violence aggression is associated with victimization emotional responses to transgressions, including jealously and anger (Foshee, Bauman, Linder, Rice, & Wilcher, 2007; Harned). As seen in this sample, DV victimization is related to depressive symptoms. It is plausible that poor relationship quality and interactions that motivate anger and jealous predict depressive symptoms as well as DV aggression.

The associations between DV aggression and low relationship power may lend support to findings that dissatisfaction with the relationship or an attempt to increase relationship power or control precipitates violence (Harned, 2001; Kaura & Allen, 2004; Ronfeldt et al., 1998; Smith Slep, Foran, Heyman, & Snarr, 2010). However, the connection between low relationship power and depressive symptoms was not through DV aggression, which suggests an increased understanding of motives, precipitating factors and contexts for DV aggression in girls is needed to address this common, concerning behavior (Dichter, Cederbaum, & Teitelman, 2010; Foshee et al., 2007). Other mediators that may explain the relationship between low relationship power and depressive symptoms could be relationship dynamics that foster jealousy, anger or self-defense in light of threatening behavior (Harned).

Nurses are well-positioned to identify depressive symptoms and dating violence victimization and aggression and to improve outcomes with interventions that address relationship power.

Limitations

These results must be discussed in light of the study's limitations. The cross-sectional design limits causal attribution and generalizability. However, for shorter causal effects, such as effects in relatively short-term adolescent relationships, cross sectional designs are able to provide stronger inferences (Rindfleisch, Malter, Ganesan, & Moorman, 2008). Studies that examine relationship power, depression, and DV over time will be able to further explore longer term causation but most likely the variables will continue to dynamically affect each other.

Self-report is also a study limitation, however, efforts were made to assure participants of confidentiality. Such efforts were shown to improve adolescent self-report in other studies assessing sensitive topics (Jones, 2003). In addition, DV is measured by incident counts that limit understanding of DV context, meaning, and motivation (Dichter et al., 2010). Furthermore, due to intercollinearity of the variables DV aggression and victimization, they could not be explored as multiple mediators. Increased sensitive measures of DV would help differentiate the violence context and help inform targeted interventions effective at preventing or addressing DV. This measure of relationship power only included domains of relationship control and decision-making dominance and was only examined in sexual relationships. Future work may include other aspects of relationship power and examine differences in those relationships that do not include sexual activity.

Despite these limitations, this study adds to the extant literature concerning the high prevalence of DV victimization and associated depressive symptoms through low relationship power in a sample of adolescent girls at-risk for both relationship violence and depression. New contributions to the literature are evidence that adolescent girls' DV aggression is common, frequently as a sole aggressor, and DV aggression is associated with depressive symptoms and low relationship power. However, it does not explain the association between low relationship power and depressive symptoms. These results add to the urgency to understand DV aggression among adolescent girls not only as it affects their victims, but as it is associated with their own mental health.

Implications for Nursing Practice

Depression in adolescent girls is common and has severe health consequences, immediate and long term (DiClemente et al., 2005; Eaton et al., 2010; Hallfors et al., 2004; Hankin & Abela, 2011). It is essential that nurses lead prevention, assessment, and treatment efforts. This study informs nursing practice by supporting associations of DV victimization and aggression and low relationship power to depressive symptoms. Clinical nursing implications include increasing screening measures for depression and DV victimization and aggression. High scores on depression screens and any reports of violence should prompt further investigation into the other relationship factors. Dating patterns that indicate relationship control and power imbalances should raise concern. Additionally, girls who report DV aggression should not be ignored in light of important evidence of its associations with depressive symptoms and DV victimization. The participants in this sample reported their current romantic relationships were of fairly long duration and were important to them. Taking evidence from this sample and existing literature into account, it is clear that romantic relationships are a critical part of adolescent development. Clinical and community intervention research needs to target relationship equity and skills, including communication and negotiation, to positively influence relationship power and improve mental health outcomes for this population (Furman et al., 2009).

Nurses are also at the forefront of women's health research. Research implications indicate a need for longitudinal studies with large, heterogeneous samples for multivariate path analysis to increase understanding of adolescent DV and depression. In addition, qualitative research has the potential to contribute to holistic understanding of context, motivations and meaning of DV victimization and aggression within adolescent populations. This understanding will increase the success of individual and community interventions targeting depression related to DV.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institutes of Mental Health (F31MH082646-01A2), the National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR 007100), Sigma Theta Tau, Epsilon Xi Chapter, and Susan B. Anthony Institute. The authors thank Drs. Morrison-Beedy, Tuttle, Fals-Stewart, and Sommers.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest or relevant financial relationships.

Contributor Information

Ellen M. Volpe, Centers for Health Equity Research and Global Woman's Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Thomas L. Hardie, Drexel University and an adjunct full professor in the School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Catherine Cerulli, Laboratory of Interpersonal Violence and Victimization, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY.

References

- Anderson KL. Perpetrator or victim? Relationships between intimate partner violence and well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(4):851–863. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(5):651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Cross C. Consequences of teen dating violence: Understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women. 2008;14(9):998–1013. doi: 10.1177/1077801208322058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK. The effect of power in sexual relationships on sexual and reproductive health: An examination of the evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(3):189–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco-Ros C, Sanchez-Lorente S, Martinez M. Recovery from depressive symptoms, state anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder in women exposed to physical and psychological, but not to psychological intimate partner violence alone: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:98–110. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bralock AR, Koniak-Griffin D. Relationship, power, and other influences on self-protective sexual behaviors of African American female adolescents. Health Care for Women International. 2007;28(3):247–267. doi: 10.1080/07399330601180123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawner BM, Waite RL. Exploring patient and provider level variables that may impact depression outcomes among African American adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2009;22(2):69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, et al. Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(10):1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9(5):451–457. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Fadden MK. Intimate partner violence and disabilities among women attending family practice clinics. Journal of Women's Health. 2005;14(9):829–838. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA. More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Gender and power. 1st. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter M, Cederbaum JA, Teitelman AM. The gendering of violence in intimate relationships. In: Chesney-Lind M, Jones N, editors. Fighting for girls: New perspectives on gender and violence. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2010. pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Lang DL, Crosby RA, Salazar LF, Harrington K, Hertzberg VS. Adverse health consequences that co-occur with depression: A longitudinal study of black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):78–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, et al. Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(SS05):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filson J, Ulloa E, Runfola C, Hokoda A. Does powerlessness explain the relationship between intimate partner violence and depression? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25(3):400–415. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Bradley RG, Helff CM, Laughlin JE. A model for predicting dating violence: Anxious attachment, angry temperament, and need for relationship control. Violence & Victims. 2002;17(1):35–47. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.35.33639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Linder F, Rice J, Wilcher R. Typologies of adolescent dating violence: Identifying typologies of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22(5):498–519. doi: 10.1177/0886260506298829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Low S, Ho MJ. Romantic experience and psychosocial adjustment in middle adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(1):75–90. doi: 10.1080/15374410802575347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Waller JL. The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):636–641. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes MM, Davis BL, Baker SR, Servonsky EJ. Correlation of the experience of peer relational aggression victimization and depression among African American adolescent females. Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2009;22(4):175–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, Ford CA, Halpern CT. Which comes first in adolescence–Sex and drugs or depression? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(3):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic relationships: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(10):1679–1685. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abela JRZ. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Prospective rates and risk factors in a 21/2 year longitudinal study. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS. Abused women or abused men? An examination of the context and outcomes of dating violence. Violence & Victims. 2001;16(3):269–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Wang MQ, Yan F. Psychosocial factors associated with reports of physical dating violence among U.S. adolescent females. Adolescence. 2007;42(166):311–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Wang MQ, Yan F. Psychosocial factors associated with reports of physical dating violence victimization among U.S. adolescent males. Adolescence. 2008;43(171):449–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, Morales KH. Effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for adolescents when implemented by community-based organizations: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(4):720–726. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study. The Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AS, Dienemann J, Schollenberger J, Kub J, O'Campo P, Gielen AC, Campbell JC. Long-term costs of intimate partner violence in a sample of female HMO enrollees. Women's Health Issues. 2006;16(5):252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R. Survey data collection using audio computer assisted self-interview. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2003;25(3):349–358. doi: 10.1177/0193945902250423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R, Gulick E. Reliability and validity of the Sexual Pressure Scale for Women-revised. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32(1):71–85. doi: 10.1002/nur.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT. Sexual intercourse precedes partner violence in adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;36(5):386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaura SA, Allen CM. Dissatisfaction with relationship power and dating violence perpetration by men and women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(5):576–588. doi: 10.1177/0886260504262966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Gidycz CA. Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(6):717–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Crean HF, Jones SH. Determinants of adolescent female attendance at an HIV risk reduction program. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2010;21(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10(5):541–552. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Smith Slep AM, O'Leary SG. Multivariate models of men's and women's partner aggression. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(5):752–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, McArdle JJ, Hishinuma ES, Johnson RC, Miyamoto RH, Andrade NN, et al. Carlton BS. Prediction of major depression and dysthymia from CES-D scores among ethnic minority adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(5):495–503. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospero M, Kim M. Mutual partner violence: Mental health symptoms among female and male victims in four racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(12):2039–2056. doi: 10.1177/0886260508327705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Amaro H, De Jong W, Gortmaker SL, Rudd R. Relationship power, condom use, and HIV risk among women in the USA. AIDS Care. 2002;14(6):789–800. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/STD research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7):637–660. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. A CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repetto PB, Caldwell CH, Zimmerman MA. Trajectories of depressive symptoms among high risk African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(6):468–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Lauderdale DS, He T, Howes DS, Levinson W. “Between me and the computer:” Increased detection of intimate partner violence using a computer questionnaire. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2002;40(5):476–484. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.127181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Levinson W. Interventions for intimate partner violence against women: Clinical applications. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(5):601–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes KV, Pollock DA. The future of emergency medicine public health research. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2006;24(4):1053–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfleisch A, Malter AJ, Ganesan S, Moorman C. Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research. 2008;45(3):261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ronfeldt HM, Kimerling R, Arias I. Satisfaction with relationship power and the perpetration of dating violence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60(1):70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sabina C, Straus MA. Polyvictimization by dating partners and mental health among U.S. college students. Violence & Victims. 2008;23(6):667–682. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears H, Byers E, Price E. The co-occurrence of adolescent boys' and girls' use of psychologically, physically, and sexually abusive behaviours in their dating relationships. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30(3):487–504. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Meltzer C, Cornelius TL. Motivations for self-defensive aggression in dating relationships. Violence & Victims. 2010;25(5):662–676. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman JG, Raj A, Clements K. Dating violence and associated sexual risk and pregnancy among adolescent girls in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):e220–e225. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep AM, Foran HM, Heyman RE, Snarr JD. Unique risk and protective factors for partner aggression in a large scale air force survey. Journal of Community Health. 2010;35(4):375–383. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs AL, Halpern CT, Herring AH, Schoenbach VJ. Family and school socioeconomic disadvantage: Interactive influences on adolescent dating violence victimization. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(11):1956–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus H, Cerulli C, McNutt LA, Rhodes KV, Conner KR, Kemball RS, et al. Houry D. Intimate partner violence and functional health status: Associations with severity, danger, and self-advocacy behaviors. Journal of Women's Health. 2009;18(5):625–631. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Future research on gender symmetry in physical assaults on partners. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(11):1086–1097. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Victims. 2004;19(5):507–520. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.5.507.63686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Ramirez IL. Gender symmetry in prevalence, severity, and chronicity of physical aggression against dating partners by university students in Mexico and USA. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33(4):281–290. doi: 10.1002/ab.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Ratcliffe SJ, Morales-Aleman MM, Sullivan CM. Sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, and condom use among minority urban girls. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1694–1712. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons Fritz PA, O'Leary KD. Physical and psychological partner aggression across a decade: A growth curve analysis. Violence & Victims. 2004;19(1):3–16. doi: 10.1891/088667004780842886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vest JR, Catlin TK, Chen JJ, Brownson RC. Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(3):156–164. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe EM. Doctoral dissertation. University of Rochester; Rochester: 2010. HIV-risk behaviors and intimate partner violence in urban, adolescent girls: Impact of sexual relationship power and partner age differential. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/503576748?accountid=14707 (503576748) [Google Scholar]

- Vujeva HM, Furman W. Depressive symptoms and romantic relationship qualities from adolescence through emerging adulthood: A longitudinal examination of influences. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(1):123–135. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller MW, Hallfors DD, Halpern CT, Iritani BJ, Ford CA, Guo G. Gender differences in associations between depressive symptoms and patterns of substance use and risky sexual behavior among a nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2006;9(3):139–150. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Fredland N, Han HR, Campbell JC, Kub JE. Relational aggression and adverse psychosocial and physical health symptoms among urban adolescents. Public Health Nursing. 2009;26(6):489–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Ghandour RM, Kub JE. Female perpetration of violence in heterosexual intimate relationships: Adolescence through adulthood. Trauma Violence & Abuse. 2008;9(4):227–249. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]