Abstract

Introduction

Modulation of the gamma-secretase enzyme, which reduces the production of the amyloidogenic Aβ42 peptide while sparing the production of other Aβ species, is a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Satori has identified a unique class of small molecule gamma-secretase modulators (GSMs) capable of decreasing Aβ42 levels in cellular and rodent model systems. The compound class exhibits potency in the nM range in vitro and is selective for lowering Aβ42 and Aβ38 while sparing Aβ40 and total Aβ levels. In vivo, a compound from the series, SPI-1865, demonstrates similar pharmacology in wild-type CD1 mice, Tg2576 mice and Sprague Dawley rats.

Methods

Animals were orally administered either a single dose of SPI-1865 or dosed for multiple days. Aβ levels were measured using a sensitive plate-based ELISA system (MSD) and brain and plasma exposure of drug were assessed by LC/MS/MS.

Results

In wild-type mice using either dosing regimen, brain Aβ42 and Aβ38 levels were decreased upon treatment with SPI-1865 and little to no statistically meaningful effect on Aβ40 was observed, reflecting the changes observed in vitro. In rats, brain Aβ levels were examined and similar to the mouse studies, brain Aβ42 and Aβ38 were lowered. Comparable changes were also observed in the Tg2576 mice, where Aβ levels were measured in brain as well as plasma and CSF.

Conclusions

Taken together, these data indicate that SPI-1865 is orally bioavailable, brain penetrant, and effective at lowering Aβ42 in a dose responsive manner. With this unique profile, the class of compounds represented by SPI-1865 may be a promising new therapy for Alzheimer's disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a severe neurodegenerative disease that is defined by two pathological features, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Because amyloid plaques appear before the onset of clinically-defined dementia symptoms, neurodegeneration and subsequent cognitive impairment are hypothesized to be a downstream consequence of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide dysregulation [1-3]. Aβ peptides are small fragments cleaved from a much larger integral membrane protein, the amyloid precursor protein (APP). In the AD cascade, APP is cleaved initially by β-secretase (BACE), leaving the C99 fragment in the membrane, which is then cleaved by gamma-secretase, an aspartyl protease complex [4,5]. Gamma-secretase continues to make sequential cleavages every three to four amino acids [6-9], resulting in Aβ fragments ranging in size from 49 to fewer than 34 amino acids [10,11]. Much of the focus in AD research has been on Aβ42, since it has been shown to be the most amyloidogenic and neurotoxic fragment [12-14]. More recently, Aβ43 has also been shown to have these detrimental properties [15]. To test the hypothesis that lowering Aβ42 levels may slow the progression of or prevent AD, multiple amyloid-targeted therapeutic approaches have been developed and moved into human clinical trials. These include Aβ clearance-directed immunotherapies as well as inhibitors of BACE or gamma-secretase enzyme activities, both of which are required for Aβ production.

To prevent the production of these neurotoxic Aβ peptides, researchers have focused on developing small molecule inhibitors of BACE and gammasecretase. In preclinical animal models, in vivo administration of gamma secretase inhibitors led to severe side effects, including an increased number of goblet cells in the intestine and decreased intrathymic differentiation and lymphocyte development [16-18]. These adverse events were found to be the result of inhibiting gamma-secretase's ability to process other substrates, specifically NOTCH [19-21], which is critical for cell development and differentiation [22]. Similar adverse events were also observed in recent clinical trials of semagacestat and avagacestat, further suggesting that complete inhibition of gamma-secretase is not a viable approach [23-25]. Much remains unknown about the approach to prevent Aβ production through BACE inhibition, as a subset of those molecules are currently in human clinical trials [26].

The discovery of multiple structural classes of compounds that modulate gamma-secretase activity, instead of inhibiting it, offers the potential promise of avoiding the mechanism-based adverse events observed with gamma-secretase inhibitors. Gamma-secretase modulators (GSMs) are observed to decrease the production of the more amyloidogenic Aβ42 peptide, while preserving total Aβ levels and sparing gamma-secretase cleavage of the other substrates, such as NOTCH. Modulation allows the initial cleavage of substrates, but alters the processivity of the enzyme by shifting the production of Aβ peptides to the shorter, non-amyloidgenic forms without affecting the total level [27]. A first generation GSM, Flurizan from Myraid Genetics was tested in a Phase 3 trial. However, the compound is a weak modulator (IC50 = 250 μM), lacks brain penetration, and produced side effects [10,28]. The compound failed to show efficacy, and development was halted in 2008 [29]. Since the approach of gamma modulation has not been adequately tested in humans, it is still believed that a more potent, drug-like compound could be a viable therapeutic approach.

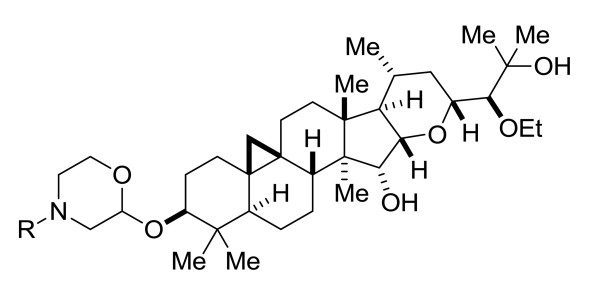

Here we describe the in vivo pharmacology for a novel series of compounds, represented by SPI-1865 (Figure 1). All compounds within the series that have been tested in vivo show a PK/PD relationship in rodents as robust as SPI-1865 (data not shown). The compound scaffold is derived from an initial hit, a triterpene glycoside (SPI-014), which was discovered through a screen of a natural products library for compounds with GSM properties [30]. Following a comprehensive and focused research effort, compounds like SPI-1865 were identified [31,32]. The compounds in this series, including SPI-1865, have a novel and proprietary structure, as well as the unique effect on the Aβ profile of lowering both Aβ42 and Aβ38, without effecting Aβ40 in cellular systems [33]. Using immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry (IP/MS) analysis of conditioned media from Satori compound-treated versus control 2B7 cells, it was observed that the total Aβ levels are maintained with concomitant lowering of Aβ38 and Aβ42 and increases in Aβ37 and Aβ39 [34]. Furthermore, since increasing substrate levels do not result in an IC50 shift, it is likely that SPI-1865 binds to the gamma-secretase complex as do other GSMs [35-37] instead of the APP substrate [33,34]. In the studies described here, the effects of SPI-1865 on Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 in both wild-type and transgenic animals were examined. The Aβ changes observed in these studies reflect the changes observed in our cellular systems, resulting in a decrease of both Aβ38 and Aβ42 in all three models, suggesting that SPI-1865 maintains its GSM properties in vivo.

Figure 1.

General structure of Satori gamma-secretase modulators (GSMs), including SPI-1865.

Materials and methods

Test compound

SPI-1865 was prepared in a manner as described in Bronk et al., patent WO2011109657 A1 20110909. Merck GSM1 was prepared as described in Madin et al., patent WO2007116228 A120071018.

Cell culture and compound treatment

CHO-2B7 cells (Mayo Clinic) are Chinese hamster ovary cells stably transfected with human βAPP 695wt [38,39]. The cells were cultured in Ham's F12 media (Thermo Fisher SH30026.01, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.25 mg/mL Zeocin and 90 ug/mL penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For compound treatment, cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/mL and allowed grow to 100% confluence over two days. Test compounds in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were diluted 100-fold directly into the media before being adding to the cells. Immediately prior to adding compound-containing media to the cells, the cells were washed once with 1X PBS. Conditioned media from CHO-2B7 cells were collected after 5 hrs of treatment and the levels of Aβ peptides were assessed as described below.

Aβ in vitro assay measurement

Conditioned media were collected after 5 hrs of treatment and diluted with one volume of MSD blocking buffer (1% BSA in MSD wash buffer). MSD Human (6E10) Aβ 3-Plex plates, which are pre-spotted with three separate spots in each well containing capture antibodies against the unique C-terminal ends of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively, were blocked with MSD blocking buffer for one hour. Samples were transferred to the blocked plates with 6E10 detection antibody and incubated for 2 hrs at room temperature with orbital shaking followed by washing and reading according to the manufacturer's instructions (SECTOR® Imager 2400 Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg MD, USA).

In vivo study methods

The animal handling and procedures were performed either at Agilux Laboratories in Worcester, MA, USA, or Cerebricon in Kuopio, Finland. All animal handling and procedures were conducted in full compliance to AAALAC International and NIH regulations and guidelines regarding animal care and welfare. These protocols were reviewed and approved by Agilux's or Cerebricon's respective Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) prior to any activities involving animals.

Female transgenic mice (Tg2576, 3 months of age; n = 20), wild-type male CD-1 mice (six weeks of age; n = 8 to 12) or wild-type male Sprague Dawley rats (200 to 225 g body weight; n = 12) were utilized to assess in vivo efficacy.

For wild-type rat and mouse studies, all animals were acclimated to the test facility for a minimum of two days prior to initiation of the study. Compounds were dosed orally in 10:20:70 ethanol/solutol/water or 10:20:70 ethanol/cremaphor/water via oral gavage. Samples were harvested at either at 6 or 24 hrs post dose for Aβ and compound exposure measurements. Blood samples were collected into K2ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and stored on wet ice until processed to plasma by centrifugation (3,500 rpm at 5°C) within 30 minutes of collection. Each brain was dissected into three parts: left and right hemispheres and cerebellum. Brain tissues were rinsed with ice cold PBS (without Mg2+ or Ca2+), blotted dry and weighed. Plasma and cerebella were analyzed for parent drug via liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). Parent drug levels were compared to a standard curve to establish the plasma and brain levels.

In the transgenic studies, compound was dosed in 10:20:70 ethanol/solutol/water via oral gavage. Samples were harvested at 24 hrs post dose for Aβ and compound exposure measurement. The mice were subjected to cisterna magna puncture and collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (approximately 5 μl per mouse). Individual CSF samples were flash-frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C. Thereafter, the mice were subjected to cardiac puncture and blood samples were collected into K2EDTA tubes and stored on wet ice until processed to plasma by centrifugation (2,000 g at 4°C for 10 minutes) within 30 minutes of collection. The plasma was aliquoted for both Aβ measurements and parent drug using LC/MS/MS. Both sets of tubes were frozen at -80°C. The brains were perfused with non-heparinized saline (the blood flushed away) and removed carefully. Brains were rinsed with ice cold PBS (without Mg2+ or Ca2+), blotted dry, dissected on ice into three pieces (left and right hemisphere and cerebellum). Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately prior to storage at -80°C. Cerebella were analyzed for parent drug via LC/MS/MS. Parent drug levels were compared to a standard curve to establish the plasma, brain and CSF levels.

Rodent Aβ determination

This protocol is a modification of protocols described by Lanz and Schachter [40] and Rogers et al. [41,42]. Frozen hemispheres were weighed into tared homogenization tubes (MP Biomedicals#6933050 for rat; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) and (Simport#T501-4AT; Simport, Beloeil, Qc, Canada) containing one 5-mm stainless steel bead (Qiagen#69989 for mouse). For every gram of brain, 10 mLs of either 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (wild-type rat and mouse) or 0.2% diethyl amine in 50 mM NaCl (transgenic mouse) was added to the brain-containing tubes on wet ice. Rat hemispheres were homogenized for one minute and mouse hemispheres were homogenized for 30 seconds at the 6.5 setting using the FastPrep-24 Tissue and Cell homogenizer (MP Biomedicals#116004500). Homogenates were rocked for 2 hrs at 4°C, then pre-cleared by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for one hour at 4°C. Pre-cleared wild-type rat and mouse homogenates were concentrated over solid phase extraction (SPE) columns (Oasis HLB 96-well SPE plate 30 μm, Waters#WAT058951; Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). Briefly, SPE columns were prepared by wetting with 1 mL of 100% methanol followed by dH20 using vacuum to pull liquids through. Brain homogenates were then added to the prepared columns (1.0 mL from rat and 0.7 mL from wild-type mouse). Columns were washed twice with 1 mL of 10% methanol followed by two 1 mL washes with 30% methanol. Labeled eluent collection tubes (Costar cluster tubes #4413; Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) were placed under SPE columns and samples were eluted under very mild vacuum with 300 μL of 2% NH4OH/90% methanol. Eluents were dried to films under vacuum with no heat in a speed vacuum microcentrifuge. Films were resuspended in 150 μL of Meso Scale Discovery (MSD, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) blocking buffer (1% BSA in MSD wash buffer) for one hour at room temperature with occasional vortexing. Transgenic mouse plasma (50 μL) was extracted in 500 μL of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride briefly at room temperature and then 450 μL was concentrated over SPE columns and dried to films as described above. Transgenic plasma films were resuspended in 225 μL of MSD blocking buffer. Pre-cleared transgenic mouse brain homogenates were diluted and neutralized as follows. A volume of 45 μL of pre-cleared transgenic mouse brain homogenates were diluted into 450 μL of blocking buffer and were neutralized with 5 μL of 0.5 M Tris pH 6.8. For Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 measurements, MSD 96-well multi-spot Human/Rodent (4G8) Aβ triplex ultra-sensitive ELISA plates, which are pre-spotted with three separate spots in each well containing capture antibodies against the unique C-terminal ends of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively, were blocked with MSD blocking buffer for one hour at room temperature with orbital shaking. A volume of 25 μL of neat resuspended wild-type rat or mouse brain homogenates were added in duplicates to the blocked 3-plex Aβ MSD plates with SULFO-TAG 4G8 antibody (MSD). Diluted and neutralized transgenic mouse brain homogenates, neat resuspended transgenic plasma samples or transgenic mouse CSF samples (diluted 1:10 in MSD blocking buffer) were added as described above to blocked MSD 96-well multi-spot Aβ triplex ultra-sensitive ELISA plates with SULFO-TAG 6E10 antibody (MSD). The Aβ 3-Plex plates were incubated for 2 hrs at room temperature with orbital shaking followed by washing and reading according to the manufacturer's instructions (SECTOR® Imager 2400, MSD). The average Aβ concentrations from duplicate measurements of each animal were converted to percent vehicle values and the treatment group averages were statistically compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.01 in all experiments.

Results

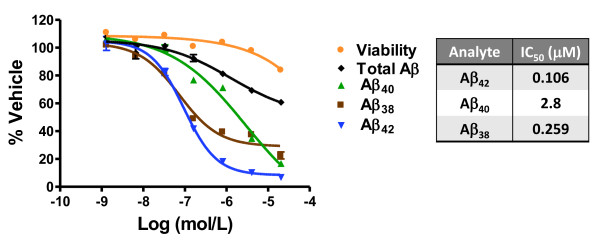

SPI-1865 decreases Aβ42 and Aβ38 in 2B7 cells

CHO-2B7 cells, which over-express human wild-type APP, were treated with increasing concentrations of SPI-1865. Conditioned media from CHO-2B7 cells were collected after 5 hrs of treatment and the levels of Aβ peptides were assessed using the MSD 3-Plex assay for Aβ42, Aβ40 and Aβ38. As shown in Figure 2, SPI-1865 reduces both Aβ38 and Aβ42 with an IC50 of 259 nM and 106 nM, respectively. Aβ40 was found to have an IC50 of 2.8 μM, resulting in > 20-fold selectivity for Aβ42 over Aβ40. Total Aβ only decreased at doses where cytotoxicity was observed, indicating that SPI-1865 is capable of modulating gamma-secretase processivity, not inhibiting enzyme activity.

Figure 2.

In vitro pharmacology of SPI-1865, a unique gamma-secretase modulator that lowers β-amyloid (Aβ)42 and Aβ38. CHO-2B7 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of SPI-1865. Conditioned media were collected after 5 hrs of treatment and the levels of Aβ peptides were assessed. The values for each Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 for each of the doses are expressed as a percentage of the Aβ levels from vehicle-treated cells. IC50's of Aβ38 (259 nM), Aβ42 (106 nM) and Aβ40 (2.8 μM) were calculated by using the inflection point or extrapolated from the curve at Aβxx 50% lowering, as appropriate. The listed values were averaged from multiple experiments and a representative dose response is shown here.

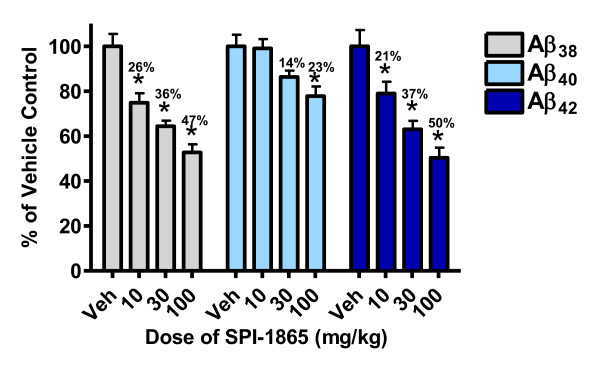

SPI-1865 reduces Aβ42 and Aβ38 with a single oral dose in Sprague Dawley rats

The compound was assessed for efficacy in Sprague Dawley rats. SPI-1865 has a delayed Tmax and half-life in excess of 24 hrs following a single oral dose in rats (Table 1). Based on this profile, compound efficacy was examined using a single oral dose and tissues were harvested 24 hrs post dose. Male Sprague Dawley rats were administered an oral dose of 10, 30 or 100 mg/kg SPI-1865 in a formulation of 10/20/70 of ethanol/cremaphor/water. The average amounts of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 (pg Aβ/g of brain) for the vehicle-treated group of rats were 312 ± 21, 3,094 ± 192 and 682 ± 61, respectively. As shown in Figure 3, at all doses, a significant lowering of brain Aβ42 and Aβ38 levels was observed compared to vehicle-treated animals. Aβ40 was significantly reduced at only the highest dose by 22 ± 5% (average percent lowering ± standard error of the mean, SEM). The decreases in Aβ42 levels were dose-responsive and correlated with the exposures in both brain and plasma. In the rats dosed with 10 mg/kg SPI-1865, brain levels reached 2.8 ± 0.3 μM and plasma levels were 3.3 ± 0.1 μM, which resulted in a lowering of Aβ42 by 21 ± 6% relative to vehicle control. The compound levels increased with the 30 mg/kg dose to 11 ± 1 μM in the brain and 8.5 ± 0.3 μM in the plasma and resulted in a 37 ± 5% decrease in Aβ42. In the 100 mg/kg dose group, brain levels reach 33 ± 2 μM and plasma levels were 14 ± 1 μM of SPI-1865, leading to an Aβ42 reduction of 50 ± 5%. Similar changes occurred with brain Aβ38 levels, resulting in dose-responsive reductions of 26 ± 5, 36 ± 3 and 47% ± 5 upon the administration of 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg SPI-1865, in that order. These data demonstrate that SPI-1865 is capable of modulating gamma-secretase in vivo and results in a similar Aβ profile as observed in vitro.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic properties of SPI-1865 in mouse and rat

| Species | Volume (L/kg)2 | Brain/plasma (24 h)1 | T1/2 (h)2 | Tmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | 9.2 | 0.4 to 1.4 | 8.3 | approximately 4 hrs |

| Rat | 5.8 | 0.5 to 1.5 | 129 | 6 to 8 hrs |

The pharmacokinetic properties of SPI-1865 were assessed in both mouse and rat. 1Based on various oral dosing regimens; 2Volume and T1/2 values are based on intravenous drug delivery data. T1/2, half-life; Tmax, time of maximum concentration.

Figure 3.

SPI-1865 dose-responsively lowers β-amyloid (Aβ)42 and Aβ38 after a single oral dose. Sprague Dawley rats were orally administered a single dose of SPI-1865 of 10, 30 or 100 mg/kg. Plasma and brain were harvested 24 hrs post dose and analyzed for compound, Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 levels. Data are graphed as a percent of vehicle control. *P-value < 0.01 based on analysis of variance (Dunnett's test).

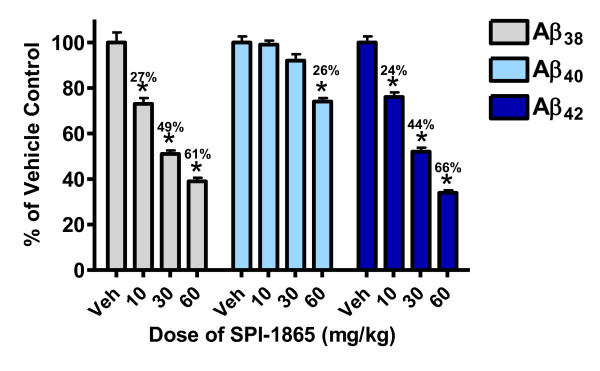

Efficacy in Sprague Dawley rats is improved following multiple day dosing

To further investigate the effects of SPI-1865 in the rat, a multiple-day study was performed. Male Sprague Dawley rats were orally dosed once a day for six days with 10, 30 or 60 mg/kg of SPI-1865. The average amounts of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 (pg Aβ/g of brain) for the vehicle-treated group of rats were 98 ± 47, 2,690 ± 92 and 840 ± 32, respectively. As shown in Figure 4, the 10 mg/kg dose resulted in brain levels of 4.4 ± 0.2 μM, plasma levels of 8.0 ± 0.4 μM, and approximately a 25% reduction in both brain Aβ38 and Aβ42 levels with no significant alteration in Aβ40 as compared to vehicle control. The 30 mg/kg dose lowered both Aβ38 and Aβ42 levels in the brain by roughly 44%, with brain exposures of 16 ± 1 μM and plasma levels 13 ± 1 μM, once again without significantly affecting Aβ40. At the highest dose, Aβ42 was reduced by 66 ± 1% at exposures of approximately 45 μM (brain) and 19 ± 1 μM (plasma). At this highest dose, Aβ40 was significantly lowered by 26 ± 2%. For all doses, Aβ38 levels were lowered to a similar degree as Aβ42. This demonstrates that multiple-day administration of SPI-1865 can result in higher compound exposures and enhanced lowering of Aβ42 levels.

Figure 4.

SPI-1865 dose-responsively lowers β-amyloid (Aβ)42 and Aβ38 after multiple oral doses. Sprague Dawley rats were orally administered SPI-1865 for six days, once a day (QD){AU query: ok as defined? yes} at a dose of 10, 30 or 60 mg/kg. Plasma and brain were harvested 24 hrs post the final dose and analyzed for compound, Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 levels. Data are graphed as a percent of vehicle control. *P-value < 0.01 based on analysis of variance (Dunnett's test).

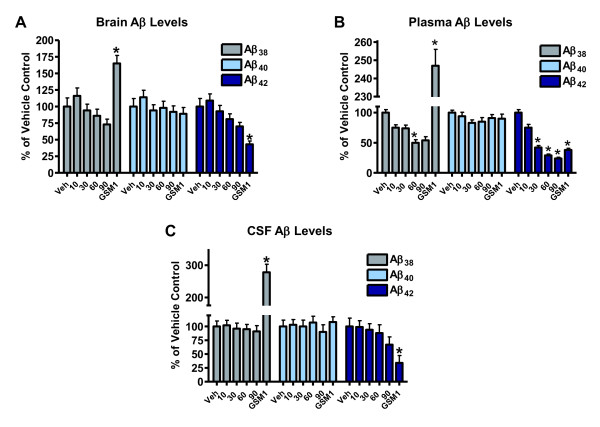

SPI-1865 reduces Aβ42 and Aβ38 in both brain and plasma of Tg2576 mice

The use of transgenic mouse models, which over-express human APP, allows for the measurement of Aβ peptides in three compartments: the brain, plasma and CSF. In this study, three month old female Tg2576 mice (n = 20 per group) were administered SPI-1865 for six days, which is sufficient to reach steady state exposures based on previous murine pharmacokinetic analysis (data not shown). The mice received 10, 30, 60 or 90 mg/kg of SPI-1865 orally once a day for six days or a positive control, Merck GSM-1, orally once on day six. Samples were harvested 24 hrs post dose for SPI-1865 and 6 hrs post dose for GSM-1. CSF and blood were directly harvested and the brain was perfused prior to collection.

As shown in Figure 5, dose-responsive decreases in Aβ38 and Aβ42 were observed in plasma with SPI-1865. In the brain, there was a trend towards lowering Aβ38 and Aβ42 levels, but the changes did not reach statistical significance. Aβ42 seemed to be somewhat lower in the 90 mg/kg dose group in the CSF, but the change was also statistically insignificant. The average amounts of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the brain (pg Aβ/g of brain), for the vehicle-treated group of Tg mice were 4,202 ± 547, 44,052 ± 5,262 and 6,470 ± 812, respectively. In the plasma of the vehicle-treated Tg2576 mice, average Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were found to be 412 ± 21 6,266 ± 251 and 1,294 ± 66 pg Aβ/g and 4,384 ± 446, 35,137 ± 4,111 and 5,057 ± 785 pg Aβ/g in the CSF, respectively. At the highest dose, an Aβ42 reduction of 76 ± 2% in the plasma was observed, with a plasma exposure of 6.4 ± 0.5 μM as measured 24 hrs post the final dose. The 10 mg/kg-treated group had no significant effect on any brain Aβ levels with drug levels in brain of 0.5 μM and plasma drug levels of 1 μM. The 30 and 60 mg/kg treatment groups had more pronounced reductions, which correlated with the increased brain and plasma exposures. For example, in the 60 mg/kg group, compound levels reached 5.4 ± 0.5 μM in the plasma and 3.9 ± 0.4 μM in the brain that resulted in a decrease in Aβ38 by 50 ± 2.4% and Aβ42 by 71 ± 2% in the plasma, respectively. Merck GSM-1 significantly reduced Aβ42 and increased Aβ38 levels. In this study, large variability was observed in both the brain and CSF samples, possibly due to blood contamination in both tissues. The variability was also observed in the vehicle and positive control groups, indicating that this is not a consequence of SPI-1865 treatment.

Figure 5.

Efficacy data for SPI-1865 in human amyloid precursor protein (APP)-overexpressing transgenic mice. SPI-1865 was orally dosed once a day (QD) for six days in female Tg2576 mice. Tissues were harvested 24 hrs after the final dose. The levels of compound, β-amyloid (Aβ)38, Aβ40, Aβ42 were measured in brain and plasma. Aβ38, Aβ40, Aβ42 levels were also measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). All values are graphed as % of vehicle control. *P-value < 0.01 based on analysis of variance (Dunnett's test).

Most interestingly, when examining the total data set from the transgenic mouse study, the plasma reductions stand out as being significantly greater than those in brain and CSF. It has been reported that the Tg2576 mice do produce peripheral Aβ and SPI-1865 could be impacting those sources directly [43]. Other studies with SPI-1865 indicate that the compound is highly protein bound, with 97.6% bound in the plasma and approximately 99.9% in the brain. When we calculate the free fraction in plasma from the 90 mg/kg dose group where there was 76% lowering of plasma Aβ42, the free plasma fraction is calculated to be 154 nM which exceeds the IC50 of 106 ± 19 nM. If we perform a similar comparison focusing on plasma levels using the 30 mg/kg group, where 58% lowering was observed, the free plasma levels are found to be 60 nM, which with inherent assay variability is reasonably close to the in vitro IC50 of 106 nM. These data suggest that free plasma concentrations of SPI-1865 are driving the efficacy that was observed in the periphery. In the brain, the highest dose resulted in a non-significant 30% lowering and a calculated brain free fraction of 6.9 ± 6 nM, which is in the range of the IC25 of 33 ± 18 nM. With the difficulty in measuring brain protein binding accurately when the free fraction is quite small, the high variability in measuring Tg2576 brain Aβ42 in vivo and the fact that there were no significant data points for brain Aβ42 lowering, we needed another study investigating free brain versus free plasma concentrations as the cause of Aβ42 reduction in the central compartment.

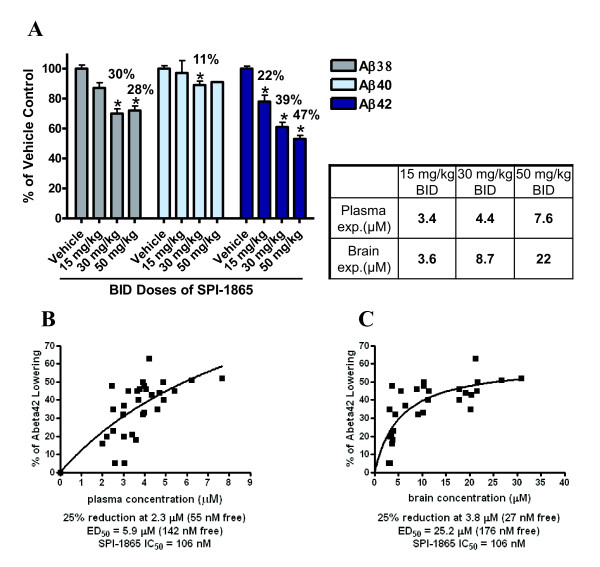

SPI-1865 lowers Aβ42 and Aβ38 in wild-type CD-1 mice

To further examine the effects of SPI-1865, an improved study design in wild-type mice, which have much less variability in Aβ levels, was performed. However, due to very low plasma levels of Aβ in wild-type mice, we are unable to measure efficacy in plasma. Based on the half-life of 8 hrs and a Tmax of approximately 4 hrs in the mouse, samples were collected 6 hrs post dose to optimize the measurement of Aβ and compound exposures. A twice-daily (BID) dosing regimen for six days was selected to ensure steady state was attained and maximize the time SPI-1865 was engaged with the enzyme complex. The results of this treatment are shown in Figure 6. The average amounts of Aβ38, Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the brain (pg Aβ/g of brain) for the vehicle-treated group of wild-type mice were 324 ± 8.5, 4,465 ± 98 and 1,012 ± 18, respectively. A significant lowering of brain Aβ42 was observed at all doses. Brain Aβ38 was also significantly lowered at the two top doses and a slight, but significant lowering of 11% was observed for brain Aβ40 levels at the 30 mg/kg dose. The total compound exposures in the 50 mg/kg BID group were found to be 7.6 ± 0.3 μM in the plasma and 22 ± 1 μM in the brain where brain Aβ42 was decreased by 47 ± 2%. The 30 mg/kg BID treatment reduced brain Aβ42 by 39 ± 2% with a total plasma exposure of 4.4 ± 0.3 μM and brain levels of 8.7 ± 1 μM. In the 15 mg/kg BID-treated animals, brain exposures of 3.6 ± 0.1 μM and a plasma exposure of 3.4 ± 0.2 μM to reduce brain Aβ42 by 22%.

Figure 6.

Steady-state efficacy of SPI-1865 in wild-type mice. SPI-1865 was orally dosed twice daily (BID) for six days in male CD-1 mice. Tissues were harvested 6 hrs after the final dose. The levels of compound, β-amyloid (Aβ)38, Aβ40, Aβ42 were measured in brain. Compound levels were also measured in plasma. (A) Aβ levels are graphed as % of vehicle control. *P-value < 0.01 based on analysis of variance (Dunnett's test). The percent Aβ42 lowering for each of the animals in this study was then plotted against the concentrations of SPI-1865 in the plasma (B) and brain (C). A best-fit line was plotted using GraphPad and the ED50s were extrapolated and shown under each graph with the IC50 of SPI-1865 in cells.

The percent Aβ42 lowering of each dosed animal was plotted against the plasma (Figure 6B) and brain exposures (Figure 6C) in μM. Best-fit lines were superimposed over the data revealing the roughly hyperbolic nature of the PK/PD relationship in BID-dosed mice. From these lines, the plasma and brain exposure levels required for 25% and 50% Aβ42 lowering were extrapolated. We found that 25% Aβ42 lowering correlated with a 2.3 μM exposure in the plasma and 3.8 μM exposure in the brain and the exposure levels associated with 50% Aβ42 lowering were 5.9 and 25.2 μM in the plasma and brain, respectively. We compared brsain free-fraction levels to the efficacy and once again found the exposures to be below the IC25 (33 ± 18 nM) even at the highest dose where 22 ± 1 nM was achieved and corresponded with 47% reduction. Taken together with the Tg2576 data, we cannot determine if brain free-fraction plays a role in SPI-1865 efficacy. Conversely, plasma free-fraction, and the observed efficacy in the brain, appear to be strongly correlated. At the highest dose, plasma free-fraction was calculated to 182 nM, which resulted in a 47% reduction in brain Aβ42, while the 30 mg/kg dose group was determined to have a plasma free-fraction of 105 nM (39% lowering of brain Aβ42) and the low dose, a plasma free-fraction of 82 nM (22% lowering of brain Aβ42). With an in vitro Aβ42 IC50 of 106 ± 19 nM and an IC25 of 33 ± 18 nM, there is a significant correlation between plasma free-fraction and brain efficacy. At all doses, the plasma free-fraction was slightly higher than the amount of compound expected to induce the same response in vitro, but the numbers are within the range of variability. Taken together these data further support the Tg2576 data that plasma free-fraction of SPI-1865 correlates with brain efficacy.

Discussion

The studies described here demonstrate that SPI-1865 is a novel modulator of gamma-secretase, which is capable of lowering both Aβ42 and Aβ38 in multiple animal models. In Sprague-Dawley rats, the compound effectively lowered Aβ42 levels following a single dose. With once a day dosing for six days, the Aβ42 and Aβ38 response was improved. Given that the half-life of SPI-1865 is greater than 24 hrs in the rat, improved efficacy was anticipated, since accumulation of compound in the plasma occurs following multiple days of dosing. However, the compound levels in the brain did not show the same degree of accumulation with multiple dosing, even though brain efficacy was improved. Based on multiple in vitro studies (data not shown), SPI-1865 is not a substrate for transporters nor does it cause CYP induction, either of which may lower the brain exposure. Together these data suggest that sustained exposure to SPI-1865 levels over multiple days contributes to enhanced efficacy of the compound to modulate gamma-secretase.

SPI-1865 was next examined for efficacy in 3-month-old, female Tg2576 mice. These mice produce human APP with the SWE mutation via the prion promoter [44]. The transgene expression has been shown to be highest in the brain, but the transgene is also expressed in peripheral tissues [43]. The peripheral production of Aβ in the Tg2576 mouse may influence the effects of SPI-1865 on brain Aβ versus plasma Aβ levels when comparing efficacy in transgenic and wild-type models.

Data from this study indicate that SPI-1865 readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, as evident in the levels of SPI-1865 measured in brain. The ability to measure efficacy in both the brain and plasma compartments in the transgenic mice allows us to probe whether total or free concentrations of compound drives efficacy. If total compound were responsible for efficacy in both tissue compartments, one would expect to see similar decreases in Aβ42 and Aβ38 in both the plasma and brain in the Tg2576, as the exposure in each compartment is similar. However, what is observed is a significantly improved lowering of Aβ42 and Aβ38 in the plasma relative to the brain. The most likely reason for the difference in efficacy between the two compartments is the level of free drug available in the plasma versus the brain. The level of compound binding in the plasma is 97.6% based on in vitro studies, leaving 2.4% free compound to interact with gamma-secretase. This is a significantly higher free fraction than the estimates for free fraction in the brain, where protein binding was measured at approximately 99.9%. When the average free fraction for each compartment is compared for the 90 mg/kg dose (braintotal = 6.9 μM; plasmatotal = 6.4 μM), the plasma free-fraction levels of 153 nM exceed the in vitro IC50 of SPI-1865 (106 ± 19 nM) and plasma Aβ42 levels were lowered by 76 ± 2%. The average brain free-fraction was only 6.9 nM, below the IC25 of 33 ± 18 nM, and while a trend toward lowering of Aβ42 was observed, it was not statistically significant. It is important to note the high variability of Aβ42 measurement in the Tg2576 brains impacted the ability to see statistically significant decreases in brain Aβ42, even with a large number of animals per group (n = 20) and may affect our determination of free versus bound in the brain. Moreover, it is challenging to get an accurate measure of free concentration in brain when brain protein binding is greater than 99%. Even in the face of these technical challenges, the data presented here indicate that the plasma free-fraction of SPI-1865 correlates most closely with Aβ lowering in that compartment.

In the Tg2576 study, the changes in CSF Aβ levels were examined along with the plasma and brain. While treatment with SPI-1865 trended towards a decrease in brain Aβ38 and Aβ42 and significantly lowered the plasma levels of Aβ42 at the three highest doses tested, in the CSF the Aβ peptide levels were not significantly decreased. There are several possible explanations for the lack of a significant effect. The high variability in CSF Aβ measurements within this study may mask an effect on the Aβ38 and Aβ42 levels. In addition, the timing of sample collection relative to dosing may have been more optimal to assess plasma changes than to assess changes in brain and CSF Aβ levels.

In wild-type mice, we further investigated the in vivo activity of SPI-1865 once steady state plasma levels were achieved. With a half-life of 8 hrs and a Tmax of approximately 4 hrs in the mouse (Table 1), a six-day BID dosing study was designed to measure exposure and Aβ levels 6 hrs post dose, allowing maximal efficacy to be observed by capturing exposures near the maximal plasma concentration and providing nearly continuous engagement with the enzyme. This is different from the Tg2576 study where once-a-day dosing was utilized for six days and samples were harvested 24 hrs post dose. In this study, there was much less variability of Aβ levels among animals than the Tg2576 mice and six days of BID dosing resulted in a significant lowering of brain Aβ42 at all doses compared to vehicle-dosed animals. Plasma and CSF levels were not measured in this experiment. When we examined plasma free-fraction versus efficacy, an Aβ42 lowering of 22 ± 4%, 39 ± 3% and 47 ± 2% occurred as the doses increased, and these changes corresponded with free plasma concentrations of 82, 105 and 182 nM, respectively. Together, this wild-type mouse study in combination with the Tg2576 model and rat data, demonstrate the ability of SPI-1865 to lower both Aβ38 and Aβ42 in vivo.

Conclusions

Taken together the data shown in these studies demonstrate that SPI-1865 is an efficacious gamma-modulator in vivo (all in vivo data are summarized in Table 2). This is demonstrated in multiple rodent models using a single dose, multiple-day dosing or a multiple-day BID dosing regimen. These data indicate that SPI-1865 is orally bioavailable, brain penetrant, and has a different Aβ profile from other GSMs, both in vitro and in vivo. SPI-1865 lowers Aβ42 and Aβ38 while sparing Aβ40 levels. This novel GSM pharmacology is dose-responsive, driven by the plasma free-fraction of the compound and is capable of reducing both Aβ42 and Aβ38 levels in APP over-expressing mice. Overall, SPI-1865 exemplifies the unique Aβ profile and good drug-like properties of SPI compounds, and further suggests they may be novel therapeutic approaches for Alzheimer's disease.

Table 2.

Summary of SPI-1865 PK/PD studies in wild-type and transgenic mouse and wild-type rat

| Species and dosing regime | Dose (mg/kg) | Tissue | Plasma exposure (μM) | Brain exposure (μM) | %Aβ38 lowering | %Aβ40 lowering | %Aβ42 lowering | Collection time (hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type rat single dose | 10 | Brain | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 26 ± 5 | 1 ± 5 | 21 ± 6* | 24 |

| 30 | Brain | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 1 | 36 ± 3* | 14 ± 4 | 37 ± 5* | 24 | |

| 100 | Brain | 14 ± 1 | 33 ± 2 | 47 ± 5* | 22 ± 5* | 50 ± 5* | 24 | |

| Wild-type rat multiple doses | 10 | Brain | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 27 ± 3* | 1 ± 2 | 24 ± 2* | 24 |

| 30 | Brain | 13 ± 1 | 16 ± 1 | 49 ± 2* | 8 ± 3 | 44 ± 2* | 24 | |

| 60 | Brain | 19 ± 1 | 45 ± 4 | 61 ± 2* | 26 ± 2* | 66 ± 1* | 24 | |

| Tg2576 mouse multiple doses | 10 | Brain | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | -16 ± 12 | -14 ± 11 | -9 ± 10 | 24 |

| 30 | Brain | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 6 ± 9 | 6 ± 9 | 7 ± 9 | 24 | |

| 60 | Brain | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 14 ± 10 | 2 ± 10 | 19 ± 8 | 24 | |

| 90 | Brain | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 27 ± 8 | 8 ± 9 | 30 ± 6 | 24 | |

| 10 | Plasma | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 25 ± 5 | 6 ± 7 | 25 ± 5* | 24 | |

| 30 | Plasma | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 26 ± 5 | 17 ± 5 | 58 ± 3* | 24 | |

| 60 | Plasma | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 50 ± 5* | 15 ± 7 | 71 ± 2* | 24 | |

| 90 | Plasma | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 46 ± 6* | 9 ± 6 | 76 ± 2* | 24 | |

| 10 | CSF | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | -2 ± 9 | -3 ± 9 | 1 ± 11 | 24 | |

| 30 | CSF | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 4 ± 10 | 0 ± 11 | 6 ± 11 | 24 | |

| 60 | CSF | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 5 ± 9 | -7 ± 12 | 22 ± 15 | 24 | |

| 90 | CSF | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 9 ± 11 | 10 ± 13 | 33 ± 14 | 24 | |

| Wild-type mouse multiple twice-daily doses | 15 | Brain | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 13 ± 4 | 3 ± 2 | 22 ± 4* | 6 |

| 30 | Brain | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 1.0 | 30 ± 3* | 11 ± 2* | 39 ± 3* | 6 | |

| 50 | Brain | 7.6 ± 0.3 | 22 ± 1 | 28 ± 2* | 9 ± 2 | 47 ± 2* | 6 |

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of SPI-1865 were assessed in mouse and rat model systems. *Statistically significant lowering of the indicated β-amyloid (Aβ) species compared to vehicle-treated animals (P < 0.01). CSF, cerebrospinal fluid. Values are given as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Abbreviations

Aβ: β-amyloid; AD: Alzheimer's disease; ANOVA: analysis of variance; APP: amyloid precursor protein; BACE: beta-secretase; BID: bis in diem or twice a day; BSA: bovine serum albumin; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide; EDTA: ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FBS: fetal bovine serum; GSM: gamma-secretase modulator; IP/MS: immunoprecipitation/mass spectrometry; LC/MS/MS: liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry; QD: quaque die, or once a day; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; SEM: standard error of the mean; SPE: solid phase extraction.

Competing interests

All authors are, or have been employees with Satori Pharmaceuticals.

Authors' contributions

RML carried out the processing and analysis of the study samples, aided in study design, and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. JAD designed the studies and coordinated with the contract research organizations to ensure studies were performed as designed and contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. TDM developed the in vitro assay used for compound assessment and produced the in vitro data shown here and edited manuscript drafts. WFA, NOF, JLH, RS and BSB designed and produced the chemical matter utilized in the described studies. JJ and JI provided support and advice for these studies. BT oversaw the biology efforts, ensured data quality and edited manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Robyn M Loureiro, Email: rloureiro@shire.com.

Jo Ann Dumin, Email: joadumin@gmail.com.

Timothy D McKee, Email: timothy.mckee@biogenidec.com.

Wesley F Austin, Email: wesleyfaustin@gmail.com.

Nathan O Fuller, Email: nathan.fuller@astrazeneca.com.

Jed L Hubbs, Email: jedhubbs@gmail.com.

Ruichao Shen, Email: rcshen@gmail.com.

Jeff Jonker, Email: jeff.jonker@satoripharma.com.

Jeff Ives, Email: jeff.ives@satoripharma.com.

Brian S Bronk, Email: brian.s.bronk@satoripharma.com.

Barbara Tate, Email: Barbara.Tate@satoripharma.com.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Paul Pearson for his insightful discussions, Kelly Ames and Kristin Rosner for their support throughout these studies, and the members of Agilux and Cerebricon for their contributions to the in vivo studies

References

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre M, Steiner H, Fuchs K, Capell A, Multhaup G, Condron MM, Teplow DB, Haass C. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein at a site corresponding to the S3 cleavage of Notch. EMBO reports. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidemann A, Eggert S, Reinhard FB, Vogel M, Paliga K, Baier G, Masters CL, Beyreuther K, Evin G. A novel epsilon-cleavage within the transmembrane domain of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein demonstrates homology with Notch processing. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2825–2835. doi: 10.1021/bi015794o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuda N, Funamoto S, Yagishita S, Takami M, Osawa S, Dohmae N, Ihara Y. Equimolar production of amyloid beta-protein and amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain from beta-carboxyl-terminal fragment by gamma-secretase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14776–14786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi-Takahara Y, Morishima-Kawashima M, Tanimura Y, Dolios G, Hirotani N, Horikoshi Y, Kametani F, Maeda M, Saido TC, Wang R, Ihara Y. Longer forms of amyloid beta protein: implications for the mechanism of intramembrane cleavage by gamma-secretase. J Neurosci. 2005;25:436–445. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1575-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Dohmae N, Qi Y, Kakuda N, Misonou H, Mitsumori R, Maruyama H, Koo EH, Haass C, Takio K, Morishima-Kawashima M, Ishiura S, Ihara Y. Potential link between amyloid beta-protein 42 and C-terminal fragment gamma 49-99 of beta-amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24294–24301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagishita S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Ishiura S, Ihara Y. Abeta46 is processed to Abeta40 and Abeta43, but not to Abeta42, in the low density membrane domains. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:733–738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde TE, Ran Y, Felsenstein KM. Shifting a complex debate on gamma-secretase cleavage and Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 2012;31:2237–2239. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takami M, Nagashima Y, Sano Y, Ishihara S, Morishima-Kawashima M, Funamoto S, Ihara Y. gamma-Secretase: successive tripeptide and tetrapeptide release from the transmembrane domain of beta-carboxyl terminal fragment. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13042–13052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2362-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett JT, Berger EP, Lansbury PT Jr. The carboxy terminus of the beta amyloid protein is critical for the seeding of amyloid formation: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4693–4697. doi: 10.1021/bi00069a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT Jr. Seeding "one-dimensional crystallization" of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie? Cell. 1993;73:1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E, Pickford F, Kim J, Onstead L, Eriksen J, Yu C, Skipper L, Murphy MP, Beard J, Das P, Jansen K, Delucia M, Lin WL, Dolios G, Wang R, Eckman CB, Dickson DW, Hutton M, Hardy J, Golde T. Abeta42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron. 2005;47:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Suemoto T, Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Funamoto S, Mihira N, Matsuba Y, Yamada K, Nilsson P, Takano J, Nishimura M, Iwata N, Van Broeckhoven C, Ihara Y, Saido TC. Potent amyloidogenicity and pathogenicity of Abeta43. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1023–1032. doi: 10.1038/nn.2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano J, McKay J, Dagenais C, Foster-Brown L, Pognan F, Gadient R, Jacobs RT, Zacco A, Greenberg B, Ciaccio PJ. Modulation of notch processing by gamma-secretase inhibitors causes intestinal goblet cell metaplasia and induction of genes known to specify gut secretory lineage differentiation. Toxicol Sci. 2004;82:341–358. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searfoss GH, Jordan WH, Calligaro DO, Galbreath EJ, Schirtzinger LM, Berridge BR, Gao H, Higgins MA, May PC, Ryan TP. Adipsin, a biomarker of gastrointestinal toxicity mediated by a functional gamma-secretase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46107–46116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GT, Manfra D, Poulet FM, Zhang Q, Josien H, Bara T, Engstrom L, Pinzon-Ortiz M, Fine JS, Lee HJ, Zhang L, Higgins GA, Parker EM. Chronic treatment with the gamma-secretase inhibitor LY-411,575 inhibits beta-amyloid peptide production and alters lymphopoiesis and intestinal cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12876–12882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fre S, Huyghe M, Mourikis P, Robine S, Louvard D, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signals control the fate of immature progenitor cells in the intestine. Nature. 2005;435:964–968. doi: 10.1038/nature03589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, Pedersen EE, Galante P, Hald J, Heller RS, Ishibashi M, Kageyama R, Guillemot F, Serup P, Madsen OD. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:36–44. doi: 10.1038/71657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es JH, van Gijn ME, Riccio O, van den Born M, Vooijs M, Begthel H, Cozijnsen M, Robine S, Winton DJ, Radtke F, Clevers H. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele L, Osborne B. Arbiter of differentiation and death: Notch signaling meets apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:393–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199912)181:3<393::AID-JCP3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coric V, van Dyck CH, Salloway S, Andreasen N, Brody M, Richter RW, Soininen H, Thein S, Shiovitz T, Pilcher G, Colby S, Rollin L, Dockens R, Pachai C, Portelius E, Andreasson U, Blennow K, Soares H, Albright C, Feldman HH, Berman RM. Safety and tolerability of the gamma-secretase inhibitor avagacestat in a phase 2 study of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1430–1440. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extance A. Alzheimer's failure raises questions about disease-modifying strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:749–751. doi: 10.1038/nrd3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly Halts Development of Semagacestat for Alzheimer's Disease Based on Preliminary Results of Phase III Clinical Trials. http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=499794

- Ghosh AK, Brindisi M, Tang J. Developing beta-secretase inhibitors for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2012;120:71–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggen S, Beher D. Molecular consequences of amyloid precursor protein and presenilin mutations causing autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4:9. doi: 10.1186/alzrt107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbimbo BP. Why did tarenflurbil fail in Alzheimer's disease? J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:757–760. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS. Book Flurizan's Failure Leaves Key Alzheimer's Theory Unresolved (Editor ed.^eds.) City: Wall Street Journal; 2008. Flurizan's Failure Leaves Key Alzheimer's Theory Unresolved. [Google Scholar]

- Findeis MA, Schroeder F, McKee TD, Yager D, Fraering PC, Creaser SP, Austin WF, Clardy J, Wang R, Selkoe D, Eckman CB. Discovery of a novel pharmacological and structural class of gamma secretase modulators derived from the extract of Actaea racemosa. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:941–951. doi: 10.1021/cn3000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbs JL, Fuller NO, Austin WF, Shen R, Creaser SP, McKee TD, Loureiro RM, Tate B, Xia W, Ives J, Bronk BS. Optimization of a natural product-based class of gamma-secretase modulators. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9270–9282. doi: 10.1021/jm300976b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller NO, Hubbs JL, Austin WF, Creaser SP, McKee TD, Loureiro RM, Tate B, Xia W, Ives J, Findeis MA, Bronk BS. The initial optimization of a new series of gamma-secretase modulators derived from a triterpene glycoside. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:908–913. doi: 10.1021/ml300256p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee TD, Loureiro RM, Dumin JA, Zarayskiy V, Tate B. An improved cell-based method for determining the gamma-secretase enzyme activity against both Notch and APP substrates. J Neurosci Methods. 2013;213:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate B, McKee TD, Loureiro RM, Dumin JA, Xia W, Pojasek K, Austin WF, Fuller NO, Hubbs JL, Shen R, Jonker J, Ives J, Bronk BS. Modulation of gamma-secretase for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:210756. doi: 10.1155/2012/210756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebke A, Luebbers T, Fukumori A, Shirotani K, Haass C, Baumann K, Steiner H. Novel gamma-secretase enzyme modulators directly target presenilin protein. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37181–37186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.276972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumpertz T, Rennhack A, Ness J, Baches S, Pietrzik CU, Bulic B, Weggen S. Presenilin is the molecular target of acidic gamma-secretase modulators in living cells. PloS one. 2012;7:e30484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki Y, Higo T, Uemura K, Shimada N, Osawa S, Berezovska O, Yokoshima S, Fukuyama T, Tomita T, Iwatsubo T. Phenylpiperidine-type gamma-secretase modulators target the transmembrane domain 1 of presenilin 1. EMBO J. 2011;30:4815–4824. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugabook SJ, Yager DM, Eckman EA, Golde TE, Younkin SG, Eckman CB. High throughput screens for the identification of compounds that alter the accumulation of the Alzheimer's amyloid beta peptide (Abeta) J Neurosci Methods. 2001;108:171–179. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MP, Uljon SN, Fraser PE, Fauq A, Lookingbill HA, Findlay KA, Smith TE, Lewis PA, McLendon DC, Wang R, Golde TE. Presenilin 1 regulates pharmacologically distinct gamma -secretase activities. Implications for the role of presenilin in gamma -secretase cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26277–26284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz TA, Karmilowicz MJ, Wood KM, Pozdnyakov N, Du P, Piotrowski MA, Brown TM, Nolan CE, Richter KE, Finley JE, Fei Q, Ebbinghaus CF, Chen YL, Spracklin DK, Tate B, Geoghegan KF, Lau LF, Auperin DD, Schachter JB. Concentration-dependent modulation of amyloid-beta in vivo and in vitro using the gamma-secretase inhibitor, LY-450139. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2006;319:924–933. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K Chesworth R Felsenstein KM Shapiro G Albayya F Tu Z Spaulding D Catana F Hrdlicka L Nolan S Wen M Yang Z Vulsteke V Patzke H Koenig G DeStrooper B Ahlijanian M Putative gamma secretase modulators lower Aβ42 in multiple in vitro and in vivo models Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association 20095P428–P429.23604405 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K, Felsenstein KM, Hrdlicka L, Tu Z, Albayya F, Lee W, Hopp S, Miller MJ, Spaulding D, Yang Z, Hodgdon H, Nolan S, Wen M, Costa D, Blain JF, Freeman E, De Strooper B, Vulsteke V, Scrocchi L, Zetterberg H, Portelius E, Hutter-Paier B, Havas D, Ahlijanian M, Flood D, Leventhal L, Shapiro G, Patzke H, Chesworth R, Koenig G. Modulation of gamma-secretase by EVP-0015962 reduces amyloid deposition and behavioral deficits in Tg2576 mice. Mol Neurodegen. 2012;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]