Abstract

Inflammation has been associated with the two classic lesions in the Alzheimer’s (AD) brain, amyloid deposits and neurofibrillary tangles. Recent data suggest that Triflusal, a compound with potent anti-inflammatory effects in the central nervous system in vivo, might delay the conversion from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to a fully established clinical picture of dementia. In the present study, we investigated the effect of Triflusal on brain Aβ accumulation, neuroinflammation, axonal curvature and cognition in an AD transgenic mouse model (Tg2576). Triflusal treatment did not alter the total brain Aβ accumulation but significantly reduced dense-cored plaque load and associated glial cell proliferation, proinflammatory cytokine levels and abnormal axonal curvature, and rescued cognitive deficits in Tg2576 mice. Behavioral benefit was found to involve increased expression of c-fos and BDNF, two of the genes regulated by CREB, as part of the signal transduction cascade underlying the molecular basis of long-term potentiation. These results add preclinical evidence of a potentially beneficial effect of Triflusal in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Transgenic mice, Triflusal, Amyloid, Neuroinflammation, Cytokines, Cognition, CREB, c-fos, BDNF

Introduction

Neuropathological and epidemiological data suggest that inflammation plays an important role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Wyss-Coray, 2006). Abundant activated microglia and astrocytes, and release of proinflammatory mediators have been invariantly identified in AD brains in association with the classic extracellular deposits of amyloid called senile plaques (SP), in particular with dense-core or fibrillar Aβ-containing plaques, and are believed to contribute to neurotoxicity (Akiyama et al., 2000; Koenigsknecht and Landreth, 2004). In addition, multiple epidemiological investigations point to a risk reduction in long-term users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (McGeer and McGeer, 1996; Wyss-Coray, 2006). The biological mechanism underlying this protection is not completely understood. Even though the main activity of NSAIDs is to inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX) activity, other mechanisms of action have been proposed for activity of certain NSAIDs such inhibition of amyloid-β formation, PPAR-gamma agonism and NFkappaB negative regulation or stimulation of neurotrophin synthesis, that could be potentially beneficial in AD (reviewed in Imbimbo, 2009). Multiple studies have tested the effects of traditional NSAIDs on transgenic mouse models of AD. Consistent in most of these studies there is a reduction of activated microglia in many cases accompanied by a decrease in Aβ load (reviewed in McGeer and McGeer, 2007). However, placebo-controlled clinical trials with NSAIDs in AD patients have produced negative results so far (reviewed in McGeer and McGeer, 2007). A trial with rofecoxib in individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was also negative (Thal, 2005). The primary prevention study with naproxen and celecoxib (ADAPT) in elderly subjects at high risk of dementia was terminated early because of cardiovascular risks associated with both these agents, and meaningful data on the study’s primary outcome (prevention of AD) were not available (Martin, 2008). Of note, most of the above clinical trials have involved agents with a selective action against COX-2. However there are no epidemiological data indicating that COX-2 selective inhibitors would decrease the risk of AD and, as opposed to traditional NSAIDs that inhibit COX-1 with variable actions against COX-2, they conferred no protection or even increased the levels of Aβ, like in the case of celecoxib, when tested in AD transgenic mouse models (Kukar et al., 2005).

We have recently conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial of Triflusal in patients with amnestic MCI (aMCI), in many cases the earliest clinical phases of AD, and found that Triflusal significantly lowered the rate of conversion from aMCI to dementia of AD type (Gomez-Isla et al., 2008). Triflusal (2-acetoxy-4-trifluoromethylbenzoic acid), a widely used platelet antiaggregant with structural similarities to salicylates platelet but which is not derived from aspirin, is a COX-1 inhibitor that also inhibits to a lesser extent inflammatory induced COX-2 expression (reviewed in Murdoch and Plosker, 2006). After oral administration, Triflusal is rapidly hydrolysed to its active metabolite 2-hydroxy-4-trifluoromethyl-benzoic acid (HTB), which is able to cross the blood brain barrier as it has been recently shown in healthy volunteers (Valle et al., 2005). Triflusal is well tolerated and has a reduced risk of haemorrhagic complications in comparison to aspirin (reviewed in Murdoch and Plosker, 2006). In vitro studies have demonstrated that Triflusal and HTB are potent inhibitors of NFkappaB activation and the subsequent expression of several cytokines and COX-2 (Fernández de Arriba et al., 1999; Bayon et al., 1999; Hernández et al., 2001). Moreover orally administered Triflusal conferred robust neuroprotection and downregulated glial activation and expression of NFkappaB-regulated proinflammatory genes, like IL-1β, TNF-α or COX2, in postnatal rat models of cerebral ischemia and excitotoxicity (Acarin et al., 2001, 2002).

In the present study we hypothesized that Triflusal may also help protect the brain against AD-related neuroinflammatory mechanisms and improve cognition in vivo. To test this hypothesis, Tg2576 mice overexpressing human mutant APP (Swedish mutation KM670/671NL) (Hsiao et al., 1996) received Triflusal or vehicle beginning at 10 months of age for 3 consecutive months and at 13 months of age for 5 consecutive months. Triflusal treatment significantly reduced compact (fibrillar, Thioflavin-S reactive) plaque load and associated neuroinflammatory changes (activated glial cells and levels of proinflammatory IL-1β and TNF-α), and significantly improved altered neurite trajectories both near and far away from cored plaques in the brain of Tg2576 mice. Moreover, Triflusal treatment rescued spatial learning and context fear conditioning deficits, and up-regulated expression of c-fos and BDNF, two of the genes regulated by CREB (cyclic AMP response element binding protein) as part of the signal transduction cascade underlying the molecular mechanisms of neuronal plasticity. These results further suggest that Triflusal may be therapeutically beneficial in AD.

Materials and methods

Animals

Tg2576 mice overexpressing human mutant APP (Swedish mutation KM670/671NL) on a mixed hybrid genetic background C57Bl6j/SJL were used in this study (Hsiao et al., 1996).

Groups of Tg2576 mice (Tg+) were administered Triflusal (n=19) or vehicle (n=20) starting at 10 months of age during 3 consecutive months and used for subsequent clinicopathological and biochemical analyses. A group of age and gender-matched non-transgenic littermate controls (Tg−) received vehicle (n=20) on a similar timetable schedule. Additional smaller groups of Tg+ mice were administered Triflusal (n=6) or vehicle (n=6) starting at 13 months of age during 5 consecutive months and used for confirmatory neuropathological assessments. A group of age and gender-matched Tg− controls received vehicle (n=6) on a similar timetable schedule.

All animals were maintained and sacrificed according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. The study conformed to the European Union Directive 86/609/EEC.

Triflusal administration

Triflusal (a kind gift of Grupo Uriach) was administered at a daily dose of 30 mg/kg. Drug or vehicle (sodium bicarbonate) was administered for 3–5 consecutive months by oral gavage to Tg2576 mice. For Triflusal and HTB plasma measurements mice were fully anaesthetized with isoflurane and blood was drawn by cardiac puncture before sacrificing them.

Behavioral studies

Spatial reference learning and memory testing (Morris water maze)

Groups of 19–20 Tg+ and Tg− littermates underwent spatial reference learning and memory testing in the Morris water maze at 13 months of age according to previously described protocols (Gomez-Isla et al., 2003). In brief, the maze was a circular pool (diameter 1.45 m) filled with water at 20 °C. The mice underwent visible-platform training for three consecutive days (8 trials/day) using a platform raised above the water. This was followed by hidden-platform training, during which the mice were trained to locate a platform submerged 1 cm beneath the surface for 9 consecutive days (4 trials/day). Each trial was terminated when the mouse reached the platform or after 60 seconds (s), whichever came first. Twenty-four hours after the 12th, 24th and 36th trials, the mice were subjected to a probe trial in which they swam for 60 s in the pool with no platform. Trials were recorded using an HVS water maze program for analysis of escape latencies, percent of time spent in each quadrant of the pool and number of platform crossings during probe trials (analysis program Video-Tracking SMART, Panlab).

Contextual fear conditioning

For contextual fear conditioning (CFC), the mice (N=19–20 per group) were placed within the conditioning chamber and allowed to explore it for 3 minutes (min) before the onset of the unconditioned stimulus (US; footshock; 1 s/1 mA). After the footshock, they were left in the chamber for 2 min (immediate freezing) and returned to their home cages. Conditioning was tested 7 days after training for 4 min in the same conditioning chamber. Freezing response (a behavioral index of conditioned fear response) was scored by using an automated Video Tracking Fear Conditioning System (VFC) (Med Associates, St Albant, VT).

Neuropathological analysis

Tissue preparation

Mice were sacrificed under isoflurane administration and brains were immediately removed. One hemisphere was snapfrozen in dry ice for Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis. The other hemisphere was fixed for 24 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and coronally sectioned at 30 μm on a freezing sledge microtome for histological analyses.

Immunostaining

30 μm coronal sections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA), and sequentially probed with primary antibody (4G8 mouse anti-Aβ1:500, Chemicon, Temecula, CA; rabbit anti-GFAP 1:500, Chemicon; rabbit anti-IBA-1 1:2000, Wako, Osaka, Japan; mouse neurofilament antibody SMI-312 1:1000, Covance Research Products, Inc., Berkeley, CA) and the appropriate secondary antibody (anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG 1:200, Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL; Vector ABC Kit; anti-mouse conjugated with cyanine 3 (Cy3) 1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were also processed by Thioflavin-S staining for dense-core plaque counts.

Amyloid burden quantification

Total amyloid deposition was quantified using Aβ immunostaining (monoclonal anti-Aβ 4G8 and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-anti-mouse) and the anaLYSIS image system according to protocols previously published (Gomez-Isla et al., 1996; Irizarry et al., 1997). Video images were captured of each region of interest on 30 μm sections, and a threshold of optical density was obtained that discriminated staining from background. Manual editing eliminated artefacts. The total “amyloid burden”, defined as the total percentage of cortex covered by immunostained amyloid deposits, the number of plaques and the average plaque size over three sections were calculated for CA1, cingulate, dentate gyrus molecular layer, entorhinal cortex (EC), and motor, olfactory and visual cortices. Identical measurements were conducted for the subpopulation of dense-core plaques on Thioflavin-S stained sections, and vascular amyloid load was also quantified on the same sections (N=12 per group at 13 months, and N=6 per group at 18 months).

Axon curvature

Axonal curvature analyses were conducted in the EC (N=4 per group at 13 months and N=4 per group at 18 months). To visualize axons the tissue was incubated with SMI-312 antibody (1:1000, Covance Research Products) that predominantly labels axons, and a secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated with cyanine 3 (Cy3) (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch), and then counterstained with Thioflavin-S (0.05% in 50% ethanol). The analysis of axonal ratio curvature was conducted according to previously published protocols (Spires-Jones et al., 2009). In brief, microphotographs were obtained on an upright Olympus BX51 (Olympus, Denmark) fluorescence microscope with a DP70 camera using DPController and CPManager software (Olympus). Axonal curvature ratio and distance to senile plaques were measured using ImageJ software from the NIH. Axons longer than 20 μm were analyzed and their curvature ratio was calculated by dividing the curvilinear length of the axon by the straight line length of the process (D’Amore et al., 2003; Knowles et al., 1999; Lombardo et al., 2003). Distance from the measured axon segment to the closest senile plaque (if present) was measured at three points—from each end and the midpoint of the segment and the average distance was calculated from these three measurements. Axons that were closer than 50 μm to the plaque (n= =88–107 axon segments for each group) were defined as being close to plaques and the others as far from plaques (n=100–135 axon segments for each group).

Stereological astrocyte and microglial counts

Astrocyte and microglial counts were performed in the CA1 hippocampal subfield and EC using the optical disector technique (West and Gundersen, 1990) in 30 μm GFAP (astrocytes) and IBA-1 (microglia) immunostained coronal sections at equally spaced intervals (450 μm), excluding cells in the superficial plane of section. The entire volume of each region of interest was estimated according to the principle of Cavalieri, using the C.A.S.T Grid System (Olympus).

The CA1 hippocampal subfield was sampled from its caudal extent anteriorly (Bregma-3.40 to Bregma-1.46) using 50 optical disectors in each case.

The margins of the lateral EC were defined as follows: caudal, Bregma-3.88; rostral, Bregma-3.16; lateral, rhinal fissure; and medial, amygdalopyriform transition area. The number of astrocytes and microglia in the entire region was estimated using 50 optical disectors in each case.

The average coefficient of error from the sampling technique was <0.05, suggesting that a minimal amount of variance observed in the counts is due to variance from the technique (N=12 per group at 13 months, and N=6 per group at 18 months).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Aβ40 and Aβ42 ELISA

Aβ40 and Aβ42 protein levels were measured by sandwich ELISA. In brief, for the soluble Aβ fraction, 50 mg of frozen brain tissue was homogenized with 8 times volume of Tris extraction buffer (Tris/HCl 50 mM pH 7.2, NaCl 200 mM, EDTA 2 mM) with Triton X-100, 2% protease free bovine serum albumin and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 7 min at 4 °C, the resulting supernatant was diluted up to 100 times and used for ELISA measurements. For the insoluble Aβ fraction, 50 mg of frozen brain tissue was homogenized with 8 times volume of Tris extraction buffer with 2% protease free bovine serum albumin and protease inhibitor cocktail. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 7 min at 4 °C, the resulting pellet was homogenized in 70% formic acid and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then neutralized with 1M Tris buffer pH 11 and diluted up to 10,000 times for ELISA measurements. For Aβ ELISA we used 6E10 (against Aβ1–17, Chemicon) as a capture antibody and a rabbit policlonal Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 (Chemicon) as detection antibodies. After incubation for 3 h, wells were washed and a HRP-conjugated Donkey anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was added. After the plates were washed with PBS, Quantablue reagent was added and fluorescence intensity was measured at 320 nm using a Victor3 Wallac plate reader (Perkin Elmer) (N=6 per group at 18 months).

Cytokine ELISA

Frozen dissected cortices were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, pH7.4, 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% Nadeoxycholate) supplemented with 1 mM sodium fluoride (NaF); 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4); 1 mM phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride (PMSF) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) without thawing by using a glass homogenizer. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, protein concentration of the supernatant was determined with the alkaline carbonate buffer (BCA) (Pierce, Rockford, IL). 80–100 μg of protein extracts were used for mouse tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) ELISA Array Kits (Pierce). Quantification was performed using a Victor3 Wallac plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) (N=3–4 per group at 13 months).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from mouse hippocampus using the RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purified RNA (2 μg) was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript™ II First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, a reaction mix containing 0.25 μg of Oligo(dT) primers, 0.5 mM dNTP, 0.45 mM DTT, 10 U of RNaseOut and 200 U of SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min and then at 1 h at 42 °C. The reaction was stopped by incubating at 72 °C for 10 min. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in an ABI PRISM 7900 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR reaction mix contained cDNA (1 μl), 50 nM of each primer pair and 10 μl of QuantiMix EASY SYG KIT mix (Biotools, Madrid, Spain). The primers were the following: c-fos, 5′-GATGTTCTCGGGTTTCAACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGAAGGAGTCGGCTGG-3′ (reverse); BDNF, 5′-CTT CTT TGC TGC AGA ACA GG-3′ (forward) and BDNF, 5′-CTT CTC ACC TGG TGG AAC TT-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-AATTCAACGGCACAGTCAAGGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TACTCAGCACCGGCCTCACC-3′ (reverse). PCR reactions were performed by duplicate for each sample (N=9–10 per group at 13 months). Data analysis was performed by the ΔΔCt method using the SDS 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems) and normalizing each sample with GAPDH RNA.

Statistical analysis

An ANOVA with one within subject factor (day) and two between subject factors (transgenic status and treatment) for repeated measures was conducted to analyze performances on the Morris water maze test. Two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were carried out to examine main effects and possible interactions of transgenic status and treatment on CFC performance, number of astrocyte and microglial cells, levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, parenquimal and vascular amyloid burden, number of plaques, plaque size, and expression levels of c-fos and BDNF. A Tukey test was used for post-hoc analyses in the absence of interactions. ANOVA test was used to test for single effects when significant interactions could be demonstrated. For axonal curvature (which was not normally distributed), a Mann–Whitney test or Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric ANOVA was used to compare groups. In all tests the level of significance was at p<0.05. Data are presented as mean±standard error or median [25th and 75th percentile], unless otherwise indicated.

Results

The average plasma concentration of Triflusal active metabolite HTB determined in mice killed 24 h after final administration was 47.13±24.70 μg/ml.

Triflusal treatment rescued spatial memory deficits in Tg2576 mice at 13 months of age

To assess spatial reference learning and memory function, groups of 19–20 Tg+ Triflusal or untreated mice, and age and gender-matched Tg− littermates underwent testing in the Morris water maze at 13 months of age. All mice were tested in a coded manner.

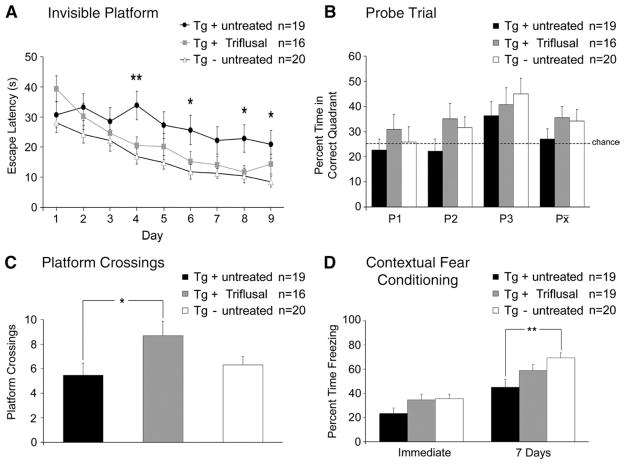

Spatial reference memory deficits, as measured by the Morris water maze test, could be detected in untreated Tg+ mice at 13 months when compared to Tg− mice (Figs. 1A–C). A mixed multifactorial ANOVA showed significant main effects of transgenic status and treatment (invisible platform p=0.048, and number of platform crossings p=0.035) on the Morris water maze test performance (Figs. 1A–C). A Tukey test showed that untreated Tg+ mice at this age showed no deficits on the visible platform training (data not shown) but performed significantly worse than similarly aged Tg− mice during the invisible platform training with longer escape latencies on multiple days (p =0.038) (Fig. 1A). These observations further confirm the deleterious impact of the transgene on spatial reference memory in the Tg2576 mouse line at 13 months of age. Of note, no significant differences could be demonstrated on any of the 9 days of invisible platform training (p= 0.555), the three probe trials administered (p=0.994) or the number of platform crossings during the probe trials (p=0.189) when comparing Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice to age-matched Tg− controls, indicating that Triflusal treatment was able to successfully rescue the spatial memory impairment displayed by Tg2576 mice at this age (Figs. 1A–C).

Fig. 1.

(A–B) Untreated Tg+ mice showed significantly longer escape latencies on multiple days of the invisible platform training compared to Tg− untreated littermates (p=0.038). Escape latencies of Triflusal Tg+ mice did not significantly differ from those of Tg− mice (p=0.555) indicating a treatment related benefit. (C) In addition, Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice achieved a significantly higher number of crossings over the platform during the probe trials than untreated Tg+ mice (p=0.040). 5 Tg+ mice of the original groups (3 Triflusal and 2 untreated) had to be excluded from the analysis due to circling behavior. (D) Conditioned freezing (fear response) was measured immediately and 7 days after the training. After seven days, untreated Tg+ mice demonstrated significantly less freezing than Tg− mice (p=0.006), while no significant differences were found between Triflusal Tg+ mice and Tg− mice (p=0.344) indicating a treatment related benefit. *p<0.05 **p<0.01.

Triflusal treatment rescued CFC deficits in Tg2576 mice at 13 months of age

To further assess hippocampal function, we tested all groups of 13 month-old animals (n=19–20 per group) in contextual fear conditioning where mice learn to associate a conditioned stimulus (test chamber) with an unconditioned stimulus (footshock) (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992). After the pairing of both stimuli, a robust associative memory is formed such that the conditioned stimulus alone can elicit a fear response (e.g., freezing behavior). As expected, all three groups displayed similar levels of freezing immediately after training (p >0.05). However, when presented with the training contest after a retention delay of 7 days, untreated Tg+ mice showed significantly reduced levels of freezing (45.23 ±6.97%; n =19) compared to Tg− control mice (69.44±4.25; n=20) (p=0.006) (Fig. 1D). Of note, Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice exhibited comparable levels of freezing (59.03±5.00; n=19) to those of Tg− controls (n=20). These results show that Triflusal treatment was able to rescue contextual memory impairment in the Tg2576 mouse line.

Triflusal treatment decreased dense-core amyloid plaque load in the brain of Tg2576 mice

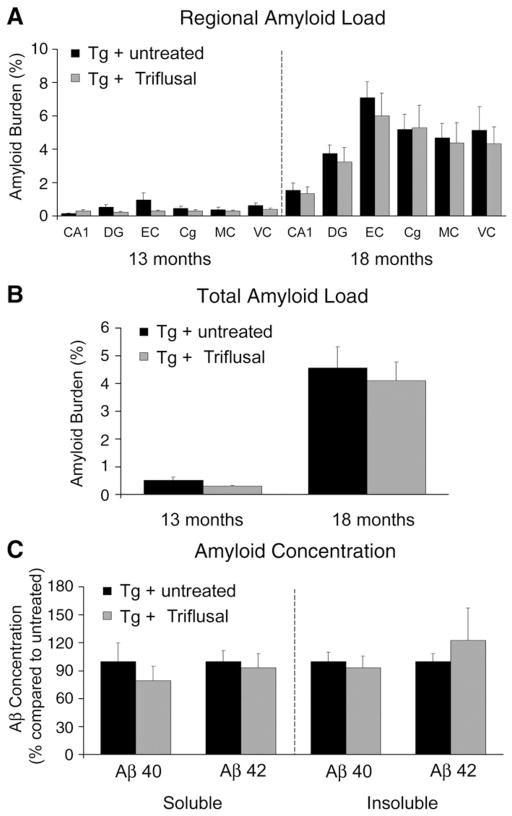

It has been previously shown that at 9 months of age Tg2576 mice develop scarce brain amyloid deposits beginning in the cingulate, motor and EC (Hsiao et al., 1996). Amyloid deposits become consistently present and numerous in older mice and many of them are surrounded by abnormally phosphorylated tau-containing punctate neurites. A two-way ANOVA failed to demonstrate a significant main effect of Triflusal treatment on the amount of brain amyloid deposition (amyloid burden and number of plaques) as labelled by Aβ immunostaining in any of the several different brain regions examined at 13 (n=12 per group) and 18 months (n=6 per group) (p>0.05) (Figs. 2A–B) or the brain levels of soluble and insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 as determined by ELISA at 18 months (p>0.05) (Fig. 2C). These results argue against Triflusal being an amyloid-β lowering drug as opposed to a subset of NSAIDs like sulindac sulfide, ibuprofen or indomethacin that have been shown to decrease amyloid-β production through γ-secretase modulation (Weggen et al., 2001, 2003). Triflusal treatment did not modify plaque size (509.4 μm2 [342.3, 604.8] Triflusal Tg+ vs. 519.2 μm2 [272.8, 729.7] untreated Tg+, p=0.880) or vascular amyloid load (0.088 ± 0.011 Triflusal Tg+ vs. 0.120 ± 0.0.3 untreated Tg+, p=0.286) suggesting that this compound does not have a significant impact on clearance of immunostained amyloid-β deposits either. Western-blot analysis showed no change in full-length APP and BACE-1 levels on Triflusal-treated mice (data no shown).

Fig. 2.

(A–B) No significant effect of treatment was observed on the amount of brain amyloid deposition as labelled by Aβ immunostaining (4G8) in any of brain regions examined at 13 (n=12 per group) (p=0.232) and 18 months of age (n=6 per group) (p=0.680). (C) No significant differences were detected on brain levels of soluble and insoluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 as determined by ELISA at 18 months (N=6 per group) (p>0.05). DG = dentate gyrus, EC = entorhinal cortex, Cg = cingulate, MC = motor cortex, VC = visual cortex. *p<0.05 **p<0.01.

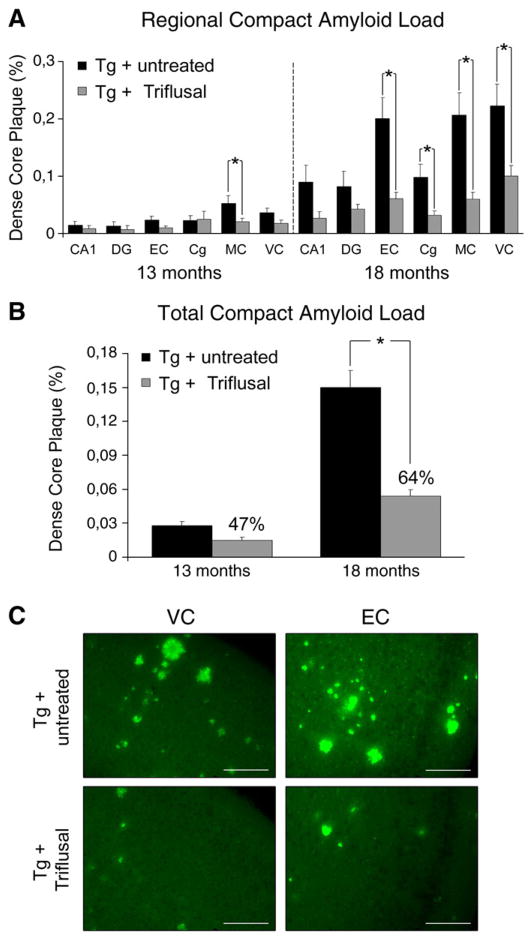

However, a significant main effect of treatment on the sub-population of dense-cored amyloid plaques was detected. At 13 months, an overall 47% reduction on compact (fibrillar, Thioflavin-S reactive) plaque burden was observed in the brain of Triflusal-treated Tg+ in comparison to untreated Tg+ animals (n =12 per group) (p = 0.052) (Figs. 3A–B). To confirm the robustness of this finding, similar measurements were conducted in mice sacrificed at 18 months. In this older group a 64% reduction in the amount of dense-core amyloid plaque load was detected in the brain of Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice in comparison to untreated Tg+ animals (n =6 per group) (p =0.002) further demonstrating a treatment effect on dense fibrillar amyloid-β deposits (Figs. 3A–C). Consistent with these data, the total number of Thio-S reactive plaques was decreased by 37% at 13 months (n =12 per group) and by 57% at 18 months in Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice when compared to untreated Tg+ animals (n =6 per group) (p =0.005). No significant differences were detected in Thio-S plaque size among the groups (305.5 μm2 [214.4, 373.6] Triflusal Tg+ vs. 324.5 μm2 [278.9, 417.8] untreated Tg+, p =0.522). The lack of a statistically significant impact of the Thioflavin-S compact plaque load reduction observed here on the total amount of immunostained amyloid-β deposits is not surprising since dense-cored plaques reactive to Thio-S in these mice at the ages examined represent only a small fraction (about 3–6%) of the total brain amyloid load labelled by 4G8 antibody.

Fig. 3.

(A) Triflusal treatment significantly decreased dense-core amyloid plaque load and number in several brain regions. (B) At 13 months, an overall 47% reduction on compact (fibrillar, Thioflavin-S reactive) plaque load was observed in the brain of Triflusal-treated Tg+ in comparison to untreated Tg+ animals (n=12 per group) (p=0.052). At 18 months, an overall 64% reduction in the amount of dense-core amyloid plaque load was detected in the brain of Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice in comparison to untreated Tg+ animals (n=6 per group) (p=0.002). (C) Representative photomicrographs of visual cortex and EC sections from untreated and Triflusal Tg+ mice stained with Thio-S. Calibration bars 400 μm. DG = dentate gyrus, EC = entorhinal cortex, Cg = cingulate, MC = motor cortex, VC = visual cortex. *p<0.05 **p<0.01.

Triflusal treatment decreased glial activation in the brain of Tg2576 mice

It has been previously demonstrated that Triflusal and its active metabolite HTB have potent anti-inflammatory effects in the CNS in vivo. Orally administered Triflusal was neuroprotective and decreased glial cell activation and inflammatory mediators in rat models of excitotoxicity and cerebral ischemia (Acarin et al., 2001, 2002).

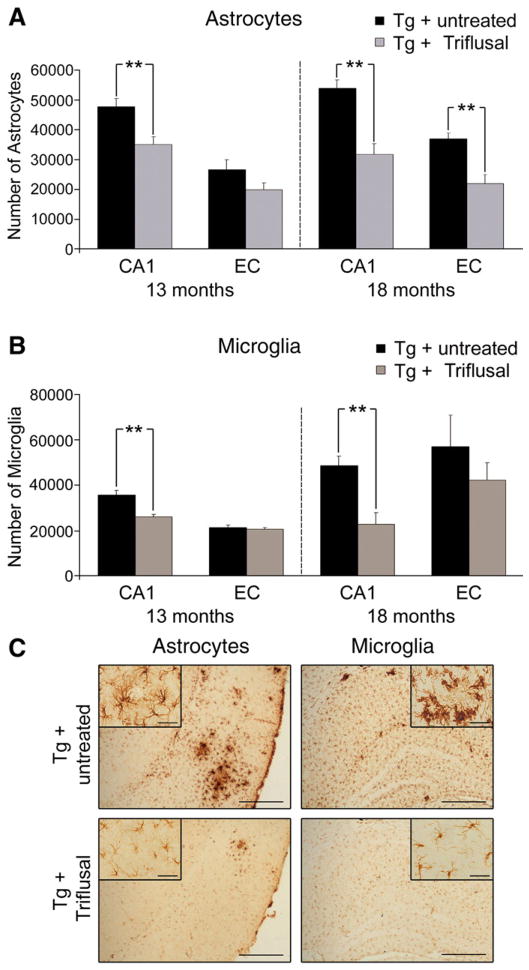

In the present study we carried out stereologically-based astrocyte and microglial counts in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus and EC in 30 μm GFAP and IBA-1 immunostained coronal sections. We concentrated on these regions for astrocyte and microglial counts because they undergo early amyloid deposition in these mice and AD brains.

The ANOVA analysis showed a significant main effect of treatment on EC and CA1 astrocyte counts (p<0.01). The total number of astrocytes in the CA1 region of Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice at 13 months of age decreased by about 25% as an average when compared to untreated Tg+ mice (n=12 per group) (p=0.004) (Figs. 4A and C). Consistent with this finding, 40% fewer astrocytes in the EC and CA1 region were detected in 18 month-old Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice when compared to untreated Tg+ animals (n=6 per group) (p=0.001 and p=0.002, respectively) (Figs. 4A and C). The amount of microglial cells as labelled by IBA-1 antibody in the CA1 region of the hippocampus was also significantly reduced in Triflusal Tg+ in comparison to untreated Tg+ animals at 13 (n=12 per group) (p=0.001) and 18 months of age (n=6) (p=0.004), (Figs. 4B–C) further demonstrating a significant anti-inflammatory effect of the compound in the brain of this AD mouse model.

Fig. 4.

(A) Stereologically-based astrocyte counts showed a significant reduction in Triflusal Tg+ mice compared to untreated Tg+ mice at 13 months in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (n=12 per group) (p=0.004). Significant reductions in the number of astrocytes in the CA1 and the EC were also observed at 18 months in Triflusal Tg+ mice compared to untreated Tg+ mice (n=6 per group) (p=0.001 and p=0.002, respectively). (B) Stereologically-based microglial cell counts also showed a significant reduction in Trifusal Tg+ mice compared to untreated Tg+ mice in the CA1 region of the hippocampus both at 13 (n=12 per group) (p=0.001) and 18 months of age (n=6 per group) (p=0.004). (C) Representative photomicrographs of EC and CA1 sections from untreated and Triflusal Tg+ mice stained with GFAP and IBA-1. Calibration bars 400 μm (EC) and 100 μm (CA1). Calibration bars 150 μm and 40 μm for the insert. *p<0.05 **p<0.01.

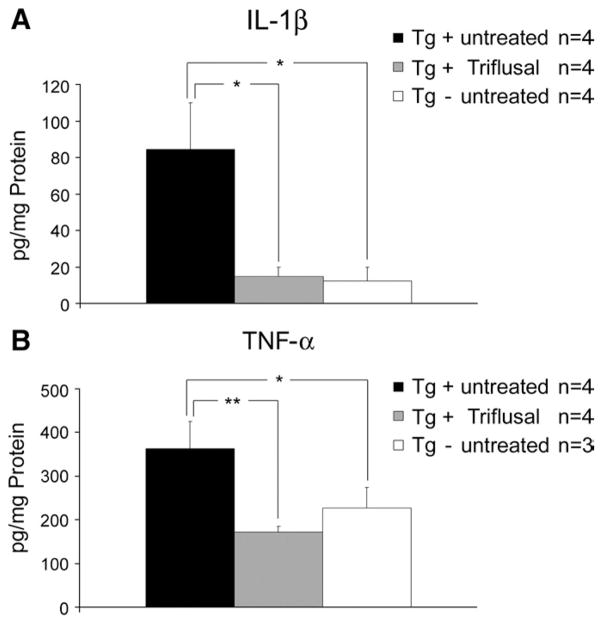

Triflusal treatment decreased the levels of proinflammatory mediators in the brain of Tg2576 mice

Along with the presence of abundant activated microglia and astrocytes, the release of numerous cytokines has been invariantly identified in AD and implicated in its pathogenesis (Griffin et al., 1998, 2000; Sheng et al., 1996). When activated, microglia and astrocytes release proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β or TNF-α among others (Lue et al., 2001). Significantly increased levels of IL-1β and TNF-α have been found in the brain of Tg2576 compared to non-trangenic littermate controls (Lim et al., 2000; Sly et al., 2001). Moreover, age-related memory loss and defective hippocampal LTP have been linked to elevations of IL-1β in rodents (Murray and Lynch, 1998). In the present study we confirmed that the levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, as determined by ELISA, were significantly increased in the brain of Tg+ compared to Tg− mice at 13 months (n=4 per group) (p<0.05). Of note, treatment with Triflusal significantly reduced the levels of both IL-1β (Fig. 5A) and TNF-α (Fig. 5B) by 70% (p<0.05) and 50% (p<0.001), respectively, in Tg+ mice (n=3–4 per group) further confirming the robust anti-inflammatory effect of Triflusal in the CNS in vivo.

Fig. 5.

(A–B) Brain levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were significantly increased in untreated Tg+ compared to Tg− mice. A significant effect of treatment was observed both on levels of IL-1β (p=0.020) and TNF-α (p=0.004) as determined by ELISA when comparing Triflusal Tg+ to untreated Tg+ mice at 13 months (n=3–4 per group). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

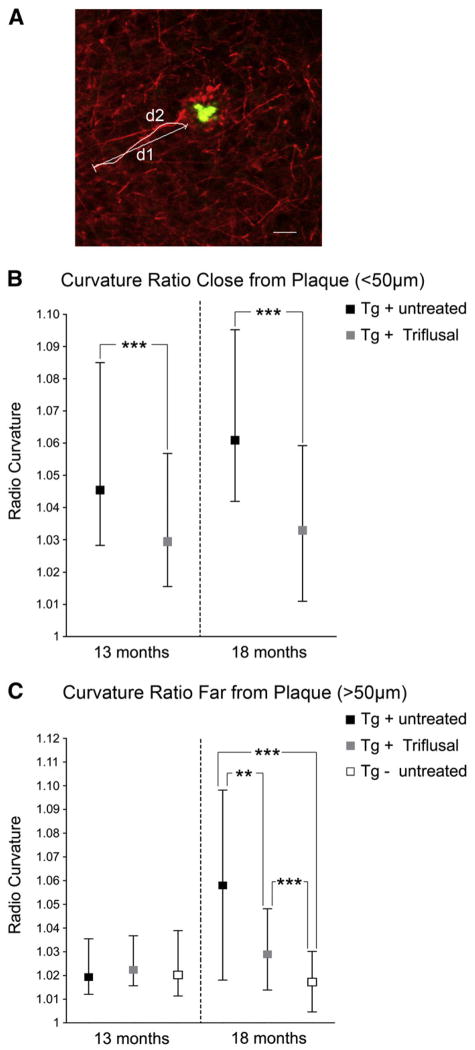

Triflusal treatment decreased plaque associated axonal trajectory alterations in the brain of Tg2576 mice

Previous studies have demonstrated dense-cored plaque associated dystrophic neurites with disrupted trajectories and reductions in dendritic spine density that likely contribute, along with inflammation and free radical generation near plaques, to altered neural system function and behavioral impairments observed in Tg2576 mice (D’Amore et al., 2003; Spires et al., 2005). In the present study we analyzed the axonal curvature ratio in the EC in 30 μm SMI-312 immunostained coronal sections (Figs. 6A–C). We confirmed that Tg2576 mice have significantly curvier axons at 13 and 18 months compared to similarly aged non-transgenic littermate controls (p<0.001). When distance from a plaque was taken into account, axons were significantly more curved close to plaque (<50 μm) compared to far from plaque (>50 μm) (p<0.001). Treatment with Triflusal significantly reduced axonal curvature in Tg2576 mice near plaques at 13 months of age (p<0.001), and both near and far from plaques at 18 months of age (p<0.01) (Figs. 6B–C). These results demonstrate that the altered axonal morphologies that accompany amyloid deposition in the brain of Tg2576 mice can be significantly ameliorated by Triflusal administration.

Fig. 6.

(A) Representative image of SMI312-positive neurites immunostaining (red) and senile plaque (Thioflavin-S) (green). Curvature ratio was calculated by dividing the curvilinear length (d1) of the axon by the straight line length of the axon (d2). Calibration bar 10 μm. (B) Treatment with Triflusal significantly reduced axonal curvature in Tg2576 mice close to plaques (<50 μm) at 13 months (p=0.0006) and 18 months of age (p<0.0001). (B) Axons far (>50 μm) from plaques were significantly curvier in 18 month-old Tg+ mice compared to non-Tg littermate controls (p<0.001). Triflusal treatment significantly straightened axons further from plaques at 18 months of age (p <0.01) (N =88–135 axons analyzed per group). *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p<0.001.

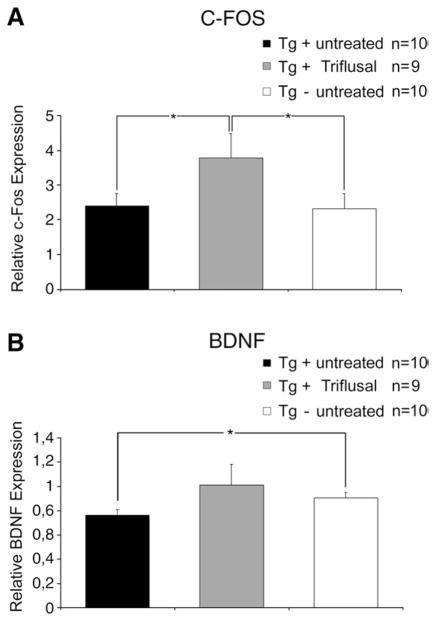

Triflusal treatment increased c-fos and BDNF expression in the brain of Tg2576 mice

The cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) appears to play a critical role in the consolidation of short-term changes in neuronal activity into long-term memory storage in a variety of systems (reviewed in Abel and Kandel, 1998). Reduced expression of several CREB target genes required for long-term potentiation (LTP), a model for synaptic plasticity in the mammalian hippocampus, has been previously found in amyloid-containing areas of aged PS1/APP transgenic mice (Dickey et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2007). Our previous results indicating that Triflusal significantly improved the performance of Tg2576 in two hippocampal tasks, the Morris water maze and CFC tests, prompted us to examine the effect of Triflusal on the hippocampal expression of memory-related genes. We examined the expression of c-fos and BDNF, two of the CREB-dependent genes essential for hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (Fleischmann et al., 2003). The hippocampus of untreated and Triflusal-treated mice tested in the water maze and CFC at 13 months of age were isolated within 2 h after completion of behavioral testing, and the expression of c-fos and BDNF mRNA was quantified by real-time RT-PCR analysis. The levels of c-fos expression did not significantly change in the hippocampus of untreated Tg+ mice in comparison to Tg− mice in this younger group (p>0.05). However, we detected a significant decrease in the levels of BDNF mRNA in the hippocampus of 13 month-old untreated Tg+ mice in comparison to Tg− mice (p<0.05). Interestingly, Triflusal-treated Tg+ mice displayed significant increase of c-fos and BDNF hippocampal levels of expression in comparison to untreated Tg+ mice (p<0.05) (Fig. 7). This result suggests that the rescue of learning capacity observed in Triflusal-treated Tg2576 mice might be related to higher hippocampal levels of CREB target genes, such as c-fos and BDNF.

Fig. 7.

(A) Triflusal treatment increased hippocampal levels of c-fos expression in Tg+ mice compared to untreated mice as measured by RT-PCR (p=0.042). (B) The level of hippocampal BDNF expression was significantly decreased in untreated Tg+ compared to Tg− mice (p=0.022). BDNF levels of Triflusal Tg+ mice did not significantly differ from those of Tg− mice (p=0.263) indicating a treatment related benefit (N=9–10 per group at 13 months). *p<0.05.

Discussion

Inflammatory changes, including the presence of abundant activated microglia and astrocytes, and release of proinflammatory mediators are consistently identified in association with the classic “neuritic” or dense-core fibrillar Aβ-containing plaques from early stages of the disease process in AD brains and transgenic mouse models, suggesting that inflammation is an important player in the pathogenesis of the disease. Of note, this subpopulation of “neuriti ” plaques surrounded by clusters of glial cells is strongly associated with a particularly severe form of dendritic and axonal changes with local spine loss, axonal swellings, and disrupted neurite trajectories both in human AD brains and transgenic mouse models (Braak and Braak, 1988; D’Amore et al., 2003; Delatour et al., 2004; Spires et al., 2005). These observations favour the idea that dense-cored plaques and concomitant chronic inflammatory changes have a dramatic synaptotoxic effect that likely contributes to cognitive decline in AD. In this scenario, inhibition of chronic inflammation has been proposed as a potentially beneficial disease-modifying strategy in the treatment of AD and other neurodegenerative conditions (Salloway et al., 2008).

Despite the failures of NSAIDs in clinical trials conducted in AD patients to date, we have recently reported the results of a placebo-controlled-trial of Triflusal in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) and found that Triflusal therapy significantly lowered the rate of conversion from aMCI to dementia of AD type (Gomez-Isla et al., 2008). Even though these results require confirmation due to premature termination of the trial, they suggest that Triflusal might be beneficial at the early clinical stages of AD. Thus, we asked whether chronic treatment with Triflusal, a compound with a demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory action in the CNS in rat models of ischemia and excitotoxicity (Acarin et al., 2001, 2002), would influence AD-like pathology and cognition in an APP transgenic mouse model (Tg2576). Tg2576 mice exhibit age-related deficits in learning and memory associated with accumulation of Aβ in their brains starting at around 9–10 months of age (Hsiao et al., 1996). As mice age, increasing numbers of neuritic (dense-core amyloid) plaques elicting an astrocytic and microglial response (Frautschy et al., 1998; Irizarry et al., 1997) and profound changes in axons and dendrites architecture (Spires and Hyman, 2004) are present in cortical and limbic structures. It remains to be clarified though why activated microglia, a cell type with phagocytic capacity, fails to efficiently clear insoluble fibrillar Aβ deposits both in AD transgenic mouse models and human AD brains.

In this study, chronic oral treatment (3–5 consecutive months) of Tg2576 mice with Triflusal at therapeutically relevant doses starting at 10 and 13 months of age did not alter the amount of Aβ40, Aβ42 or total Aβ in the brain as measured by ELISA or the total load of immunostained amyloid-β deposits but significantly lowered by more than 50% as an average the amount of dense-cored amyloid plaques in comparison to untreated animals. These results differ from other studies in which traditional NSAIDs have been tested on transgenic mouse models of AD and a dramatic reduction of total brain amyloid-β load has been reported, especially for ibuprofen and flurbiprofen (Lim et al., 2000; Yan et al., 2003; Jantzen et al., 2002) and to a lesser extent for indomethacin (Quinn et al., 2003; Sung et al., 2004). Most recently, in vitro studies have shown that this subset of NSAIDs decrease amyloid-β production through γ-secretase modulation (Weggen et al., 2001, 2003). Our results argue against Triflusal being an amyloid-β lowering drug but demonstrate that this compound selectively targets the small subset of amyloid plaques that are more intimately associated to inflammation and glial cell proliferation, dense-core or fibrillar Aβ-containing plaques that stain with Thio-S. Of note, a parallel and robust reduction in the amount of astrocytes in the EC, and of astrocytes and microglial cells in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus could be demonstrated in Triflusal-treated compared to untreated Tg2576 mice, supporting a potent anti-inflammatory action of this compound in the CNS of this transgenic mouse model of AD.

At least two hypothetical mechanisms could explain the apparent discrepancy on the observed effects of Triflusal mentioned above on different amyloid plaque subpopulations. Triflusal might: 1) interfere with Aβ aggregation process and/or 2) help protect the brain against deleterious neuroinflammatory mechanisms in AD (e.g. release of inflammatory mediators), and favour microglial phagocytosis of dense-core/highly fibrillar Aβ-containing plaques.

We cannot rule out an impact of Triflusal on amyloid aggregation, even though the absence of a significant reduction in the total amount of insoluble Aβ in the brain of Triflusal-treated Tg2576 as measured by ELISA does not favour this possibility. It has been recently demonstrated in vitro that the microglial phagocytosis elicited by the presence of fibrillar Aβ is inhibited by the presence of proinflammatory cytokines and argued that this could contribute to the accumulation of fibrillar Aβ-containing plaques in AD brains (Koenigsknecht-Talboo and Landreth, 2005). The robust impact of Triflusal treatment in the levels of proinflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, observed in the present study raises the possibility that the anti-inflammatory effect of this compound might have helped relieve an underlying proinflammatory suppression of fibrillar Aβ phagocytosis favouring the phagocytic capacity of microglial cells that intimately surround dense-cored plaques. In agreement with this hypothesis, ibuprofen has been shown to rescue fibrillar Aβ-elicited phagocytosis under a proinflammatory environment in a microglia cell line (Koenigsknecht-Talboo and Landreth, 2005). Further studies are now needed to explore this hypothetical mechanism.

As noted earlier, dense-cored or neuritic plaques are associated with a particularly severe form of dendritic and axonal changes surrounding the plaques. In addition, recent data suggest that there is an even more widespread alteration in the geometry and morphology of dendrites and axons that occurs both near plaques and distant from them (Knowles et al., 1999; Le et al., 2001). For example, in experimental animals dendrites are thinned to about 80% of their normal width; spine density is reduced by about 25%; axon and dendritic trajectories become substantially changed from normal straight patterns, both close and distant from plaques (Spires et al., 2005). The relative contribution of Aβ (aggregated vs. soluble species), inflammation and/or oxidative stress, among others, to these morphological neurite changes remains to be clarified. Previous studies have shown that curcumin, a compound with a broad spectrum of anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-fibrilogenic activities, as well as several antioxidants like alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butyl nitrone (PBN), Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) and Trolox had rapid and long-lasting straightening effects on curved neurites (Garcia-Alloza et al., 2007, 2009). In the present study we found that Triflusal treatment causes an increase in structural plasticity, as axonal curvature became significantly ameliorated, and axons in treated mice more closely approached normal straight patterns both near and away from neuritic plaques compared to untreated animals. Of note, this finding demonstrates that the axonal trajectory distortion observed in the brain of Tg2576 is reversible. Dense-cored plaque load reduction and/or decreased inflammation directly or indirectly through oxidative stress may be responsible for the observed effect.

Interestingly, the reduction of neuritic amyloid plaque load and associated inflammatory changes, and the improvement of disrupted axonal trajectories observed in the brain of Tg2576 Triflusal-treated mice may have been clinically relevant in this mouse model as they were accompanied by a rescue of memory deficits as measured by two different hippocampal tasks, the Morris water maze and the CFC test. The impact of Triflusal treatment in cognition, despite the lack of a significant reduction of total brain amyloid-β load, is particularly relevant and suggests that it may not be necessary to reduce brain amyloid burden to restore cognitive deficits. Along these lines, and additional interesting observation in this study is that Triflusal treatment was associated with a significant increase in the expression of c-fos and BDNF in the hippocampus. C-fos and BDNF are CREB-dependent genes essential for hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (Fleischmann et al., 2003), and part of the signal transduction cascade underlying the molecular basis of long-term potentiation. The relevance of c-fos induction by Triflusal remains to be clarified as we did not observed an impact of the transgenic status on c-fos. However, because these measurements were only conducted in the younger group of mice (13 months) we cannot ruled out a transgene effect on c-fos expression at more advanced ages. The impact of Triflusal on hippocampal BDNF expression is of modest proportions, however it may be relevant as the finding is in agreement with recent in vitro data that showed that R-flurbiprofen protection from cytotoxicity induced by exposure to Aβ was associated with an up-regulation of BDNF and NGF (Zhao et al., 2008). A very recent study found that long-term administration green tea catechins, known to have powerful anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties, prevented aged-related spatial learning and memory decline of C57BL/6 J mice in the Morris water maze, and increased the hippocampal expression levels of CREB-dependent genes BDNF and Bcl-2 (Li et al., 2009). Moreover, hippocampal neural stem cell transplantation rescued spatial learning and memory deficits in aged triple transgenic mice (3xTg-AD) without altering Aβ or tau pathology via BDNF (Blurton-Jones et al., 2009). Intriguingly, recent data have suggested that decreased levels of BDNF in AD mouse models may depend on the state of amyloid-β aggregation (Peng et al., 2009). Thus, the increased CREB-target gene expression in the hippocampus of Triflusal-treated animals might well underlie the rescued learning capacity of Tg2576 mice observed in the present study. Future studies will address whether Triflusal can also regulate the hippocampal CREB signaling cascade and enhance memory in wild-type mice.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that chronic treatment with Triflusal has a robust impact on dense-cored amyloid deposits and associated neuroinflammation and neuritic changes, and rescues memory deficits in a transgenic mouse model of AD. These data are in good correlation with those from a recent placebo-controlled trial of Triflusal in patients with aMCI where Triflusal therapy significantly lowered the rate of conversion from aMCI to dementia of AD type (Gomez-Isla et al., 2008), and argue that this compound might have a potential benefit in AD. The specific mechanism by which Triflusal accomplishes the observed behavioral and pathological effects requires further study.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part by FIS PI041887, CIBERNED, NIH AG020570 and Marato 072610.

References

- Abel T, Kandel E. Positive and negative regulatory mechanisms that mediate long-term memory storage. Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:360–378. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acarin L, et al. Triflusal posttreatment inhibits glial nuclear factor-kappaB, downregulates the glial response, and is neuroprotective in an excitotoxic injury model in postnatal brain. Stroke. 2001;32:2394–2402. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.097243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acarin L, et al. Decrease of proinflammatory molecules correlates with neuroprotective effect of the fluorinated salicylate triflusal after postnatal excitotoxic damage. Stroke. 2002;33:2499–2505. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000028184.80776.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, et al. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayon Y, et al. 4-trifluoromethyl derivatives of salicylate, triflusal and its main metabolite 2-hydroxy-4-trifluoromethylbenzoic acid, are potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappaB activation. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;126:1359–1366. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M, et al. Neural stem cells improve cognition via BDNF in a transgenic model of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901402106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Neuropil threads occur in dendrites of tangle-bearing nerve cells. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1988;14:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1988.tb00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore JD, et al. In vivo multiphoton imaging of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease reveals marked thioflavine-S-associated alterations in neurite trajectories. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:137–145. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delatour B, et al. Alzheimer pathology disorganizes cortico-cortical circuitry: direct evidence from a transgenic animal model. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey CA, et al. Selectively reduced expression of synaptic plasticity-related genes in amyloid precursor protein+presenilin-1 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5219–5226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05219.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Arriba A, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by 4-trifluoromethyl derivatives of salicylate, triflusal, and its deacetylated metabolite, 2-hydroxy-4-trifluoromethylbenzoic acid. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann A, et al. Impaired long-term memory and NR2A-type NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in mice lacking c-Fos in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9116–9122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09116.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frautschy SA, et al. Microglial response to amyloid plaques in APPsw transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:307–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alloza M, et al. Curcumin labels amyloid pathology in vivo, disrupts existing plaques, and partially restores distorted neurites in an Alzheimer mouse model. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1095–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alloza M, et al. Antioxidants have a rapid and long-lasting effect on neuritic abnormalities in APP:PS1 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Isla T, et al. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4491–4500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04491.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Isla T, et al. Motor dysfunction and gliosis with preserved dopaminergic markers in human alpha-synuclein A30P transgenic mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Isla T, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled-trial of triflusal in mild cognitive impairment: the TRIMCI study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22:21–29. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181611024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, et al. Glial-neuronal interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: the potential role of a ‘cytokine cycle’ in disease progression. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, et al. The pervasiveness of interleukin-1 in alzheimer pathogenesis: a role for specific polymorphisms in disease risk. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:481–487. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00110-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández M, et al. Effect of 4-trifluoromethyl derivatives of salicylate on nuclear factor kappaB-dependent transcription in human astrocytoma cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:547–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, et al. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbimbo BP. An update on the efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1147–1168. doi: 10.1517/13543780903066780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, et al. APPSw transgenic mice develop age-related A beta deposits and neuropil abnormalities, but no neuronal loss in CA1. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:965–973. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen PT, et al. Microglial activation and beta-amyloid deposit reduction caused by a nitric oxide-releasing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug in amyloid precursor protein plus presenilin-1 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2246–2254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles RB, et al. Plaque-induced neurite abnormalities: implications for disruption of neural networks in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5274–5279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsknecht J, Landreth G. Microglial phagocytosis of fibrillar beta-amyloid through a beta1 integrin-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9838–9846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2557-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Landreth GE. Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid and IgGs are differentially regulated by proinflammatory cytokines. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8240–8249. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1808-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukar T, et al. Diverse compounds mimic Alzheimer disease-causing mutations by augmenting Ab42 production. Nat Med. 2005;11:545–550. doi: 10.1038/nm1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le R, et al. Plaque-induced abnormalities in neurite geometry in transgenic models of Alzheimer disease: implications for neural system disruption. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:753–758. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.8.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, et al. Long-term administration of green tea catechins prevents age-related spatial learning and memory decline in C57BL/6 J mice by regulating hippocampal cyclic amp-response element binding protein signaling cascade. Neuroscience. 2009;159:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim GP, et al. Ibuprofen suppresses plaque pathology and inflammation in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5709–5714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo JA, et al. Amyloid-beta antibody treatment leads to rapid normalization of plaque-induced neuritic alterations. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10879–10883. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10879.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue LF, et al. Modeling microglial activation in Alzheimer’s disease with human postmortem microglial cultures. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BK. Cognitive function over time in the Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial (ADAPT): results of a randomized, controlled trial of naproxen and celecoxib. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:896–905. doi: 10.1001/archneur.2008.65.7.nct70006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Anti-inflammatory drugs in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. NSAIDs and Alzheimer disease: epidemiological, animal model and clinical studies. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch D, Plosker GL. Triflusal: a review of its use in cerebral infarction and myocardial infarction, and as thromboprophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Drugs. 2006;66:671–692. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CA, Lynch MA. Evidence that increased hippocampal expression of the cytokine interleukin-1 beta is a common trigger for age- and stress-induced impairments in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2974–2981. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02974.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, et al. Decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor depends on amyloid aggregation state in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9321–9329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4736-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J, et al. Inflammation and cerebral amyloidosis are disconnected in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;137:32–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloway S, et al. Disease-modifying therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:65–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, et al. In vivo and in vitro evidence supporting a role for the inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 as a driving force in Alzheimer pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:761–766. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly LM, et al. Endogenous brain cytokine mRNA and inflammatory responses to lipopolysaccharide are elevated in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:581–588. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00730-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires TL, Hyman BT. Neuronal structure is altered by amyloid plaques. Rev Neurosci. 2004;15:267–278. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2004.15.4.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires TL, et al. Dendritic spine abnormalities in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice demonstrated by gene transfer and intravital multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7278–7287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1879-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires-Jones TL, et al. Passive immunotherapy rapidly increases structural plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung S, et al. Modulation of nuclear factor-kB activity by indomethacin influences Ab levels but not Ab precursor protein metabolism in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:2197–2206. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63269-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal LJ. A randomized, double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1204–1215. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle M, et al. Access of HTB, main metabolite of triflusal, to cerebrospinal fluid in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0887-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggen S, et al. A subset of NSAIDs lower amyloidogenic Abeta42 independently of cyclooxygenase activity. Nature. 2001;414:212–216. doi: 10.1038/35102591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weggen S, et al. Evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease amyloid beta 42 production by direct modulation of gamma-secretase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31831–31837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the number of neurons in the human hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:1–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, et al. Transducer of regulated CREB and late phase long-term synaptic potentiation. Febs J. 2007;274:3218–3223. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med. 2006;12:1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q, et al. Anti-inflammatory drug therapy alters beta-amyloid processing and deposition in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7504–7509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07504.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, et al. Tarenflurbil protection from cytotoxicity is associated with an upregulation of neurotrophins. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:397–407. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]