Abstract

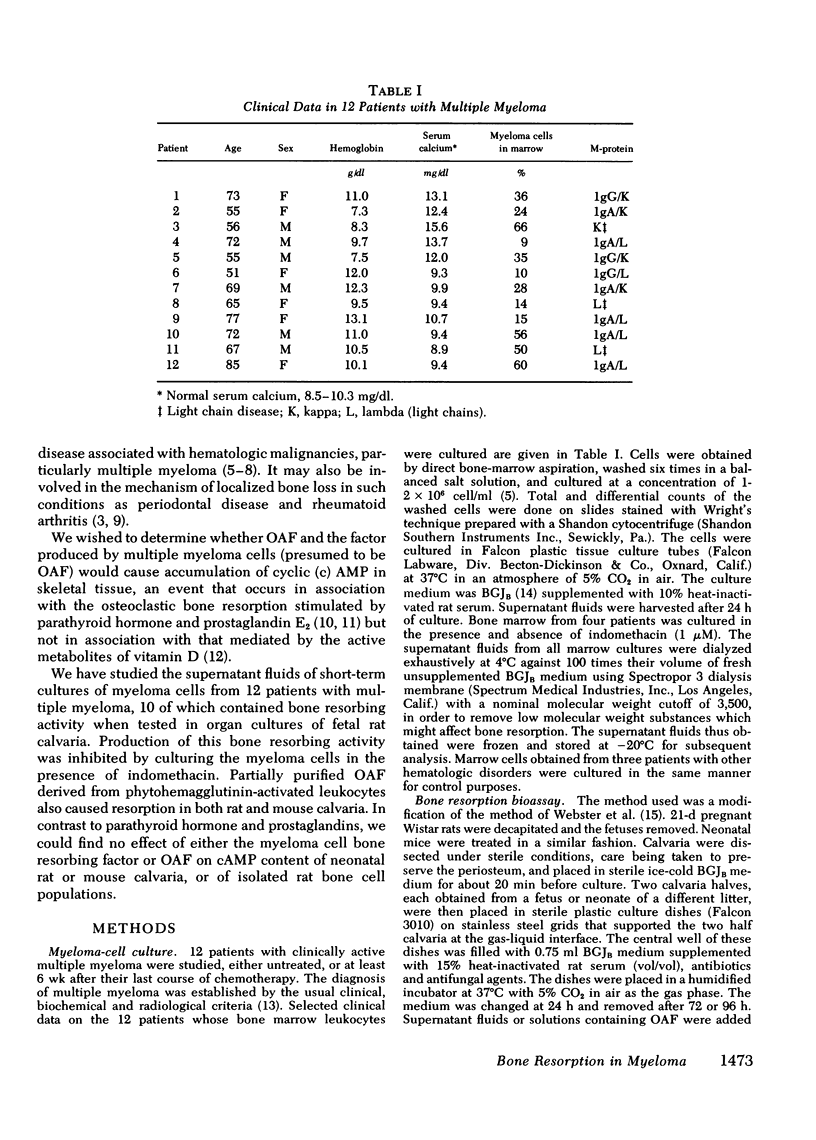

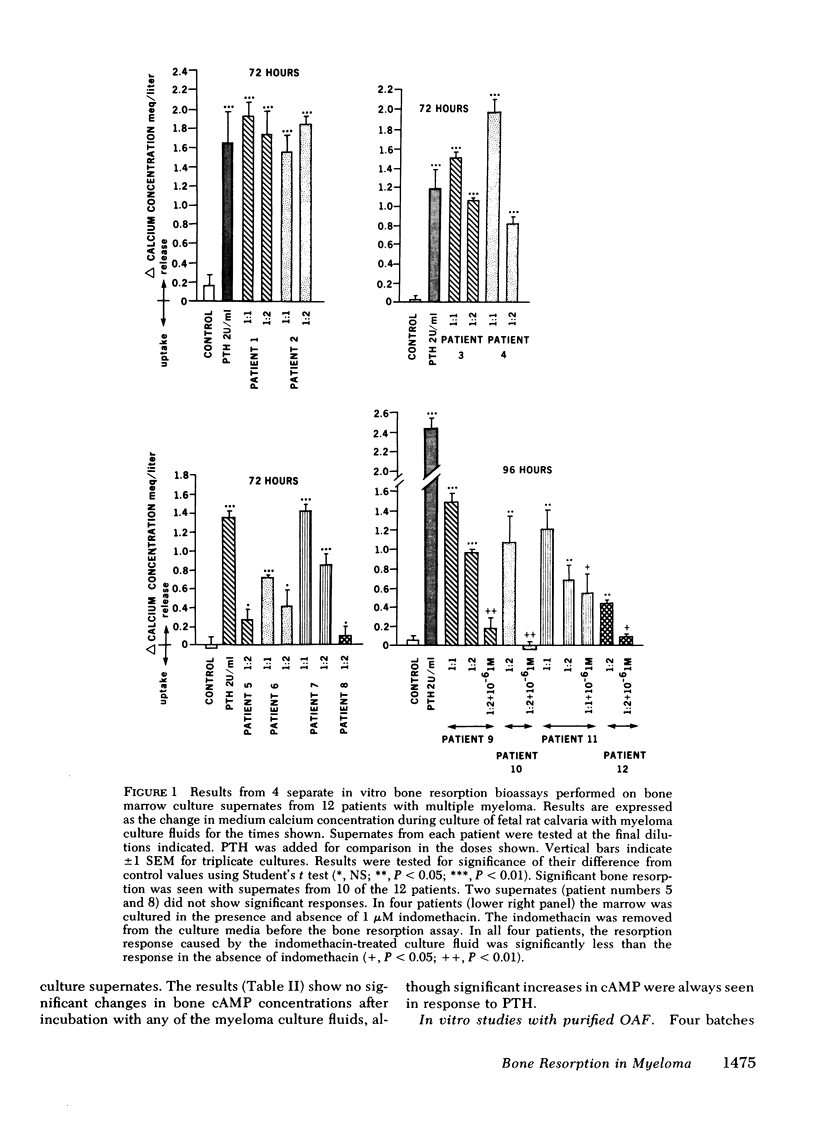

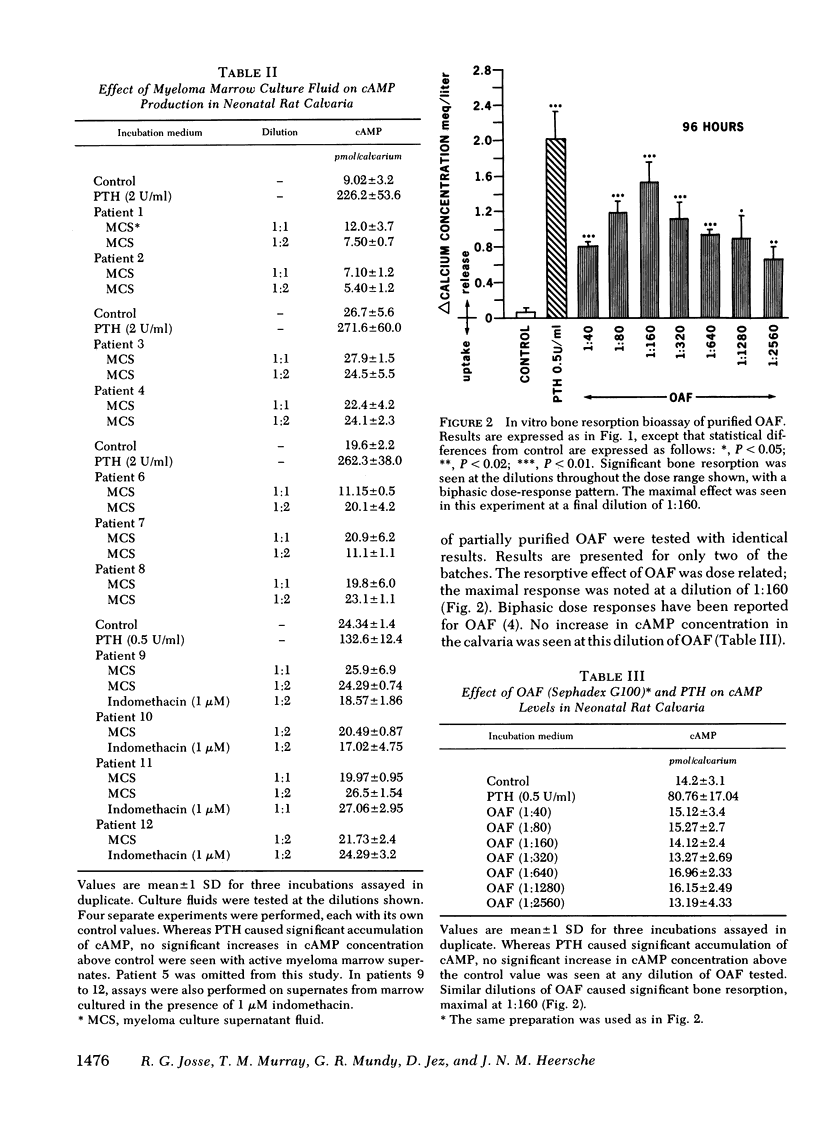

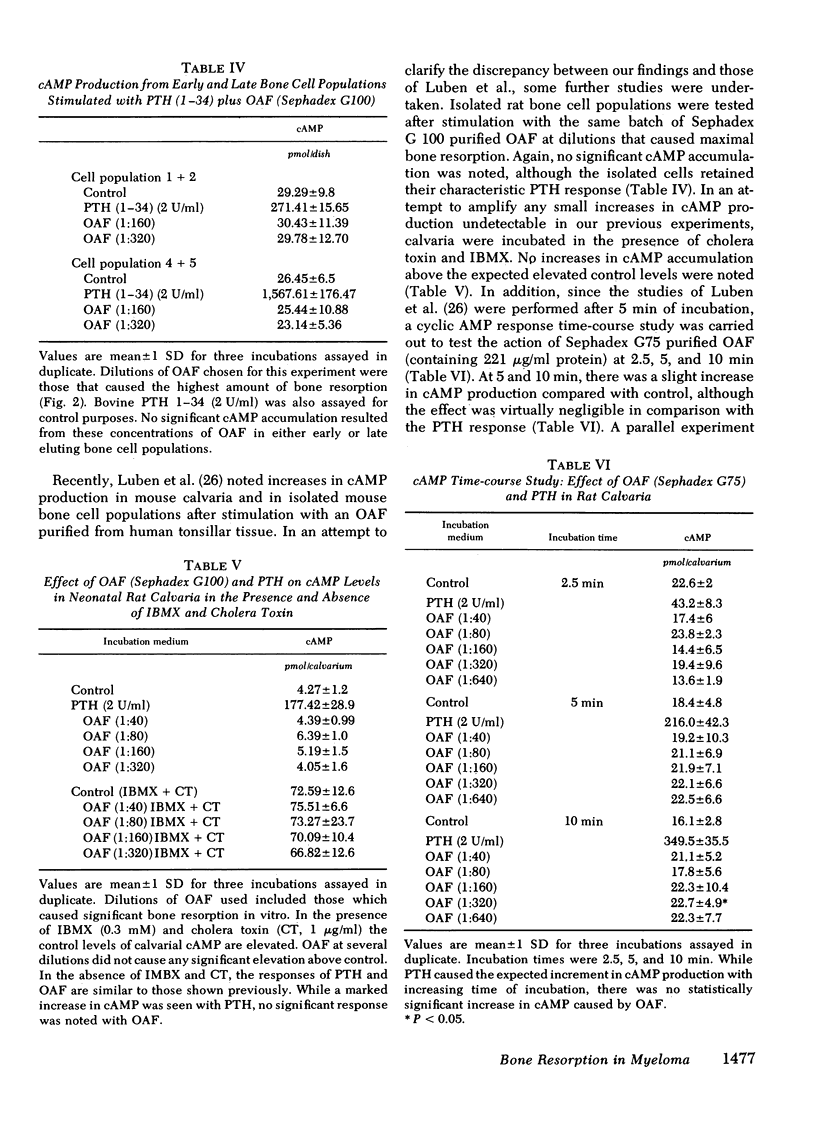

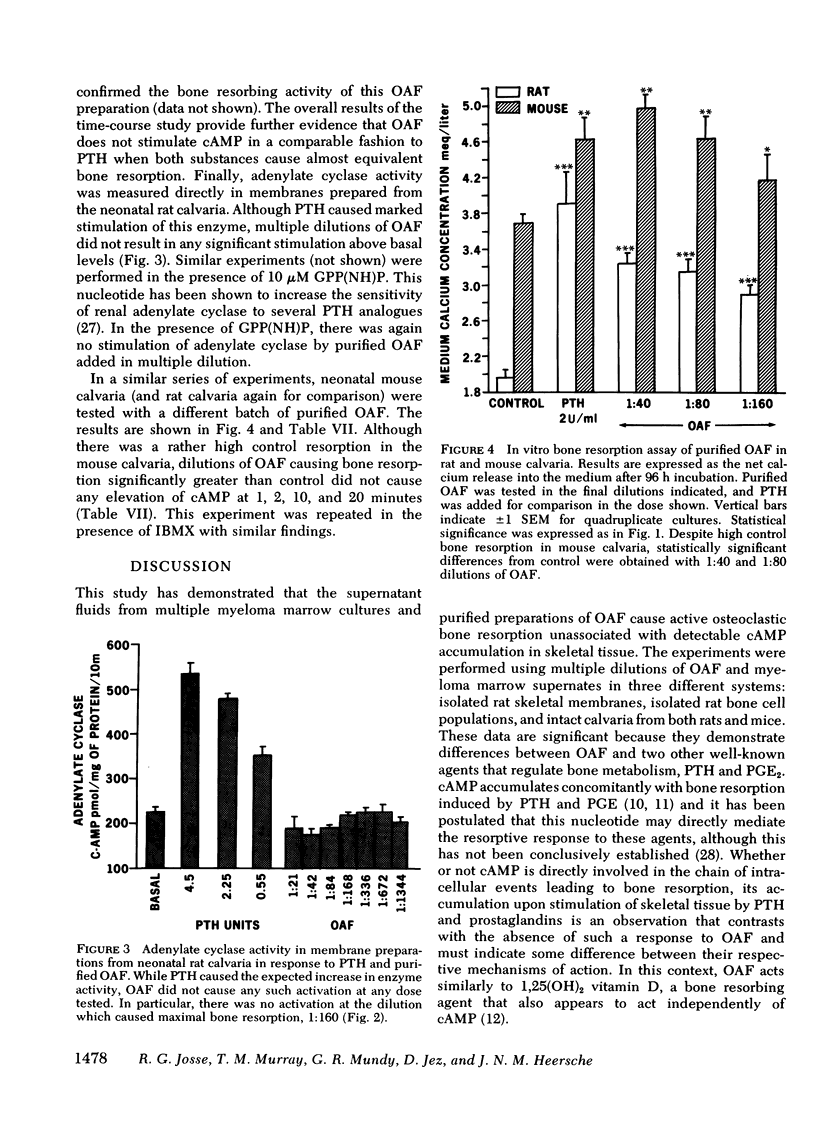

Supernatant fluids from the cultures of bone marrow cells from 10 of 12 patients with multiple myeloma (MM) caused bone resorption in organ cultures of fetal rat calvaria. In four patients, the marrow cells were cultured with and without indomethacin (1 μM). The supernatant fluids from indomethacintreated marrow cultures caused significantly less bone resorption than supernatant fluids of cell cultures without indomethacin. This inhibition of release of bone resorbing factor(s) by myeloma cultures is similar to the previously observed indomethacin-induced inhibition of osteoclast-activating factor (OAF) production by activated human leukocytes. None of the MM supernatants had any effect on cyclic (c)AMP accumulation in resorbing bone in vitro.

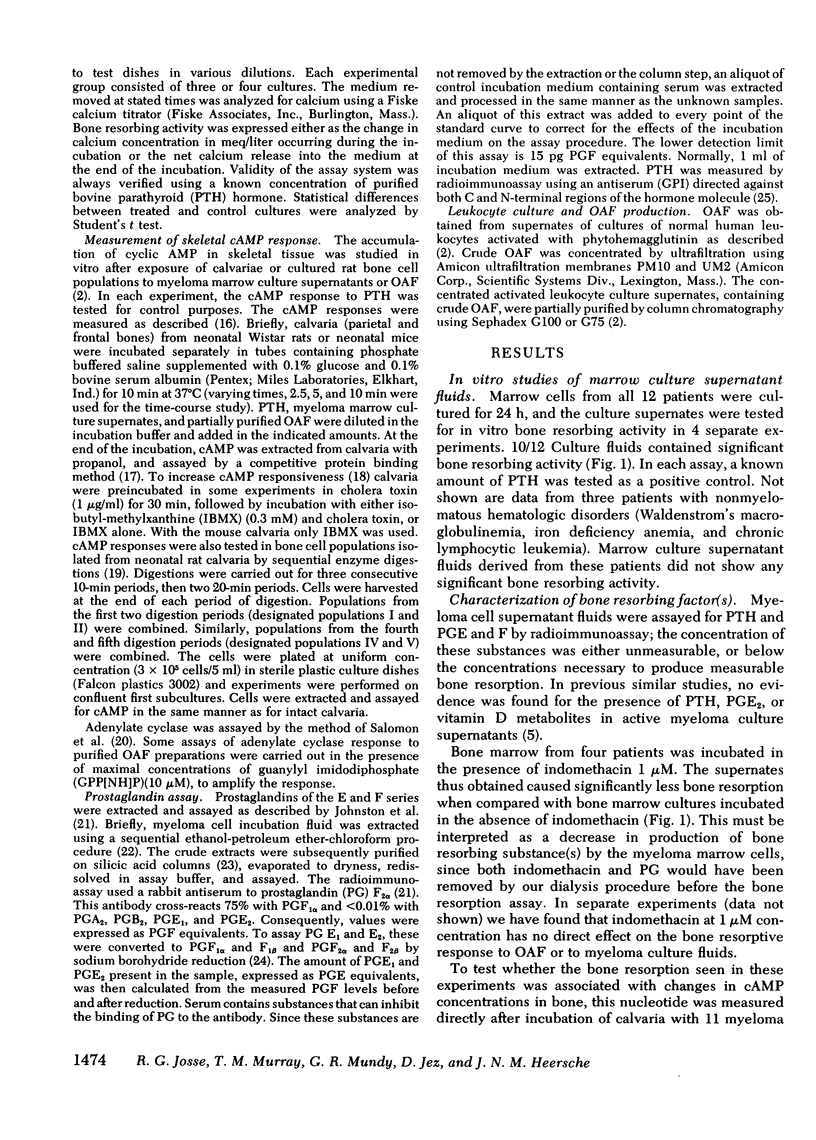

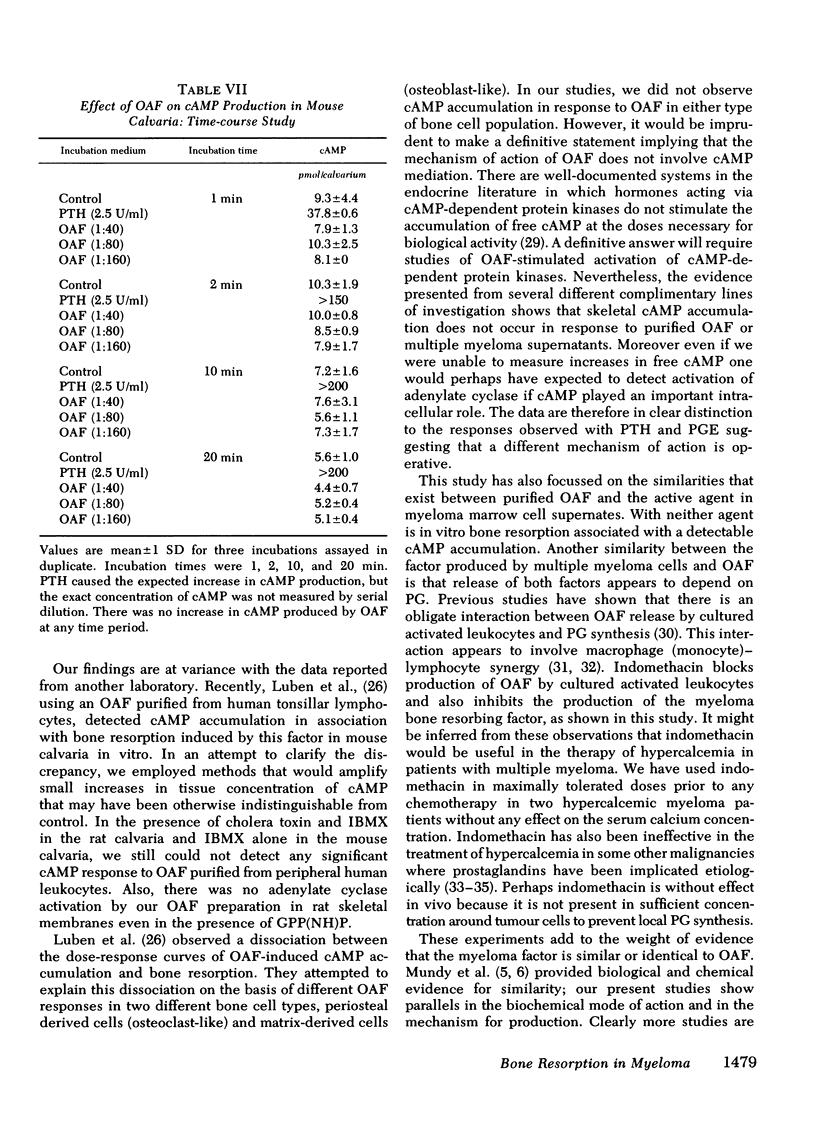

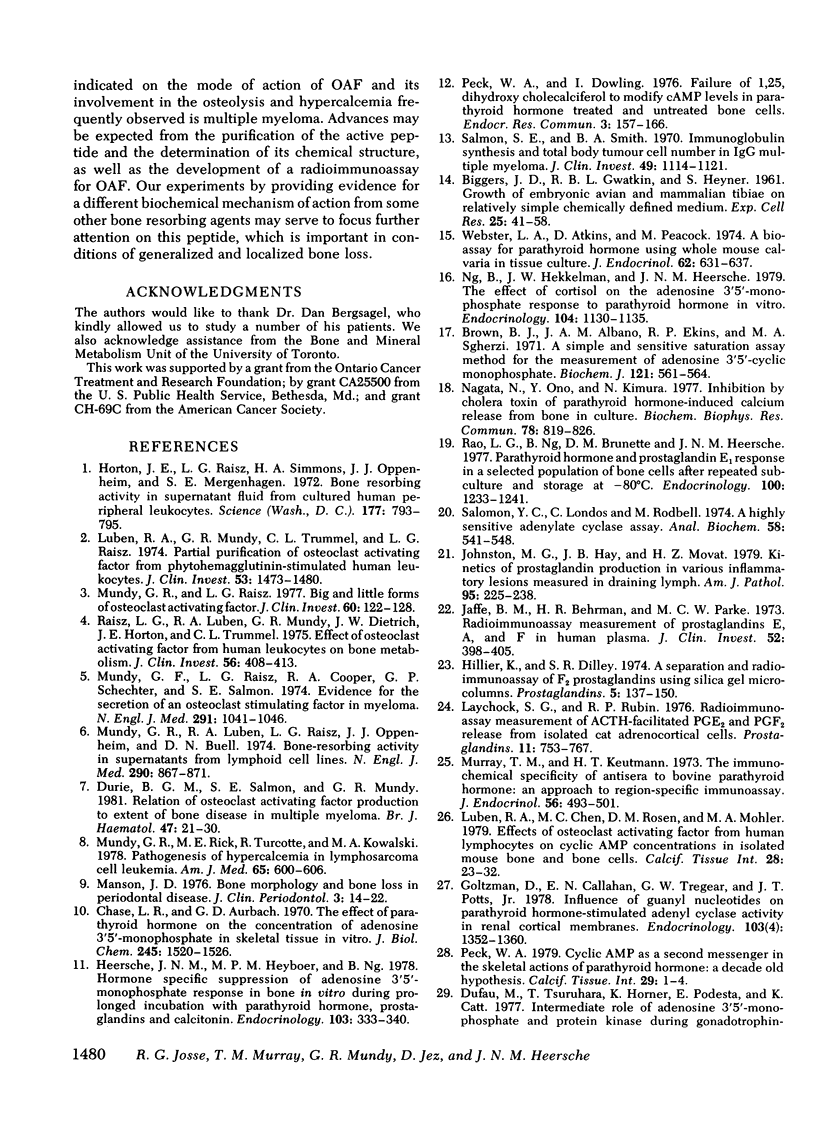

Four separate preparations of partially purified OAF obtained from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated peripheral human leukocytes were tested for their ability (a) to cause bone resorption in organ cultures of fetal rat and neonatal mouse calvaria and (b) to cause accumulation of cAMP in rat and mouse skeletal tissue in vitro. Those dilutions of OAF that caused bone resorption had no effect on accumulation of cAMP in rat or mouse calvaria incubated in vitro. In addition, no stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity in membranes prepared from fetal rat calvaria could be found. Bone cell populations isolated by sequential collagenase digestion of fetal rat calvaria also showed no cAMP response to these dilutions of OAF. Parathyroid hormone caused a clear response in all three systems. Furthermore, no cAMP response to OAF was observed in calvaria in the presence of cholera toxin (1 μg/ml) and isobutyl-methylxanthine (0.3 mM).

These observations demonstrate that (a) supernatant fluids from MM marrow cultures stimulate bone resorption but do not increase cAMP accumulation in vitro; (b) indomethacin interferes with the release of bone resorbing factors by MM bone marrow cultures suggesting that this process requires prostaglandins; and (c) Sephadex G100 or G75 purified OAF does not stimulate adenylate cyclase or increase cAMP accumulation at equivalent bone resorbing concentrations in rat and mouse skeletal tissue.

The resorptive action of MM culture fluids is similar to that of partially purified OAF from activated cultured leukocytes, but different from those of other bone resorbing factors, parathyroid hormone and prostaglandin E2, which stimulate cAMP production in skeletal tissue.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BIGGERS J. D., GWATKIN R. B., HEYNER S. Growth of embryonic avian and mammalian tibiae on a relatively simple chemically defined medium. Exp Cell Res. 1961 Oct;25:41–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. L., Albano J. D., Ekins R. P., Sgherzi A. M. A simple and sensitive saturation assay method for the measurement of adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate. Biochem J. 1971 Feb;121(3):561–562. doi: 10.1042/bj1210561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase L. R., Aurbach G. D. The effect of parathyroid hormone on the concentration of adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate in skeletal tissue in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1970 Apr 10;245(7):1520–1526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufau M. L., Tsuruhara T., Horner K. A., Podesta E., Catt K. J. Intermediate role of adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate and protein kinase during gonadotropin-induced steroidogenesis in testicular interstitial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Aug;74(8):3419–3423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durie B. G., Salmon S. E., Mundy G. R. Relation of osteoclast activating factor production to extent of bone disease in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1981 Jan;47(1):21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1981.tb02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goltzman D., Callahan E. N., Tregear G. W., Potts J. T., Jr Influence of guanyl nucleotides on parathyroid hormone-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in renal cortical membranes. Endocrinology. 1978 Oct;103(4):1352–1360. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-4-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heersche J. N., Heyboer M. P., Ng B. Hormone-specific suppression of adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate responses in bone in vitro during prolonged incubation with parathyroid hormone, prostaglandin E1, and calcitonin. Endocrinology. 1978 Aug;103(2):333–340. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-2-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J. E., Oppenheim J. J., Mergenhagen S. E., Raisz L. G. Macrophage-lymphocyte synergy in the production of osteoclast activating factor. J Immunol. 1974 Oct;113(4):1278–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J. E., Raisz L. G., Simmons H. A., Oppenheim J. J., Mergenhagen S. E. Bone resorbing activity in supernatant fluid from cultured human peripheral blood leukocytes. Science. 1972 Sep 1;177(4051):793–795. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4051.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe B. M., Behrman H. R., Parker C. W. Radioimmunoassay measurement of prostaglandins E, A, and F in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 1973 Feb;52(2):398–405. doi: 10.1172/JCI107196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M. G., Hay J. B., Movat H. Z. Kinetics of prostaglandin production in various inflammatory lesions, measured in draining lymph. Am J Pathol. 1979 Apr;95(1):225–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laychock S. G., Rubin R. P. Radioimmunoassay measurement of ACTH-facilitated PGE2 and PGF2alpha release from isolated cat adrenocortical cells. Prostaglandins. 1976 Apr;11(4):753–767. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luben R. A., Chen M. C., Rosen D. M., Mohler M. A. Effects of osteoclast activating factor from human lymphocytes on cyclic AMP concentrations in isolated mouse bone and bone cells. Calcif Tissue Int. 1979 Aug 24;28(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02441214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luben R. A., Mundy G. R., Trummel C. L., Raisz L. G. Partial purification of osteoclast-activating factor from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human leukocytes. J Clin Invest. 1974 May;53(5):1473–1480. doi: 10.1172/JCI107696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson J. D. Bone morphology and bone loss in periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1976 Feb;3(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1976.tb01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy G. R., Luben R. A., Raisz L. G., Oppenheim J. J., Buell D. N. Bone-resorbing activity in supernatants from lymphoid cell lines. N Engl J Med. 1974 Apr 18;290(16):867–871. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197404182901601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy G. R., Raisz L. G., Cooper R. A., Schechter G. P., Salmon S. E. Evidence for the secretion of an osteoclast stimulating factor in myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1974 Nov 14;291(20):1041–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197411142912001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy G. R., Raisz L. G., Shapiro J. L., Bandelin J. G., Turcotte R. J. Big and little forms of osteoclast activating factor. J Clin Invest. 1977 Jul;60(1):122–128. doi: 10.1172/JCI108748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy G. R., Rick M. E., Turcotte R., Kowalski M. A. Pathogenesis of hypercalcemia in lymphosarcoma cell leukemia. Role of an osteoclast activating factor-like substance and a mechanism of action for glucocorticoid therapy. Am J Med. 1978 Oct;65(4):600–606. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90847-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T. M., Keutmann H. T. The immunochemical specificity of antisera to bovine parathyroid hormone: an approach to region-specific radioimmunoassay. J Endocrinol. 1973 Mar;56(3):493–501. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0560493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata N., Ono Y., Kimura N. Inhibition by cholera toxin of parathyroid hormone-induced calcium release from bone in culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977 Sep 23;78(2):819–826. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng B., Hekkelman J. W., Heersche J. N. The effect of cortisol on the adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate response to parathyroid hormone of bone in vitro. Endocrinology. 1979 Apr;104(4):1130–1135. doi: 10.1210/endo-104-4-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck W. A. Cyclic AMP as a second messenger in the skeletal actions of parathyroid hormone: a decade-old hypothesis. Calcif Tissue Int. 1979 Nov;29(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02408047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck W. A., Dowling I. Failure of 1, 25 dihydroxycholecalciferol (1, 25-(OH) 2-D3) to modify cyclic AMP levels in parathyroid hormone-treated and untreated bone cells. Endocr Res Commun. 1976;3(2):157–166. doi: 10.3109/07435807609052930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisz L. G., Luben R. A., Mundy G. R., Dietrich J. W., Horton J. E., Trummel C. L. Effect of osteoclast activating factor from human leukocytes on bone metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1975 Aug;56(2):408–413. doi: 10.1172/JCI108106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao L. G., Ng B., Brunette D. M., Heersche J. N. Parathyroid hormone- and prostaglandin E1-response in a selected population of bone cells after repeated subculture and storage at -80C. Endocrinology. 1977 May;100(5):1233–1241. doi: 10.1210/endo-100-5-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon S. E., Smith B. A. Immunoglobulin synthesis and total body tumor cell number in IgG multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest. 1970 Jun;49(6):1114–1121. doi: 10.1172/JCI106327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y., Londos C., Rodbell M. A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Anal Biochem. 1974 Apr;58(2):541–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyberth H. W., Segre G. V., Hamet P., Sweetman B. J., Potts J. T., Jr, Oates J. A. Characterization of the group of patients with the hypercalcemia of cancer who respond to treatment with prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1976;89:92–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashjian A. H., Jr Editorial: Prostaglandins, hypercalcemia and cancer. N Engl J Med. 1975 Dec 18;293(25):1317–1318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197512182932511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster L. A., Atkins D., Peacock M. A bioassay for parathyroid hormone using whole mouse calvaria in tissue culture. J Endocrinol. 1974 Sep;62(3):631–637. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0620631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda T., Mundy G. R. Monocytes regulate osteoclast-activating factor production by releasing prostaglandins. J Exp Med. 1979 Aug 1;150(2):338–350. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.2.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda T., Mundy G. R. Prostaglandins are necessary for osteoclast-activating factor production by activated peripheral blood leukocytes. J Exp Med. 1979 Jan 1;149(1):279–283. doi: 10.1084/jem.149.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]