Abstract

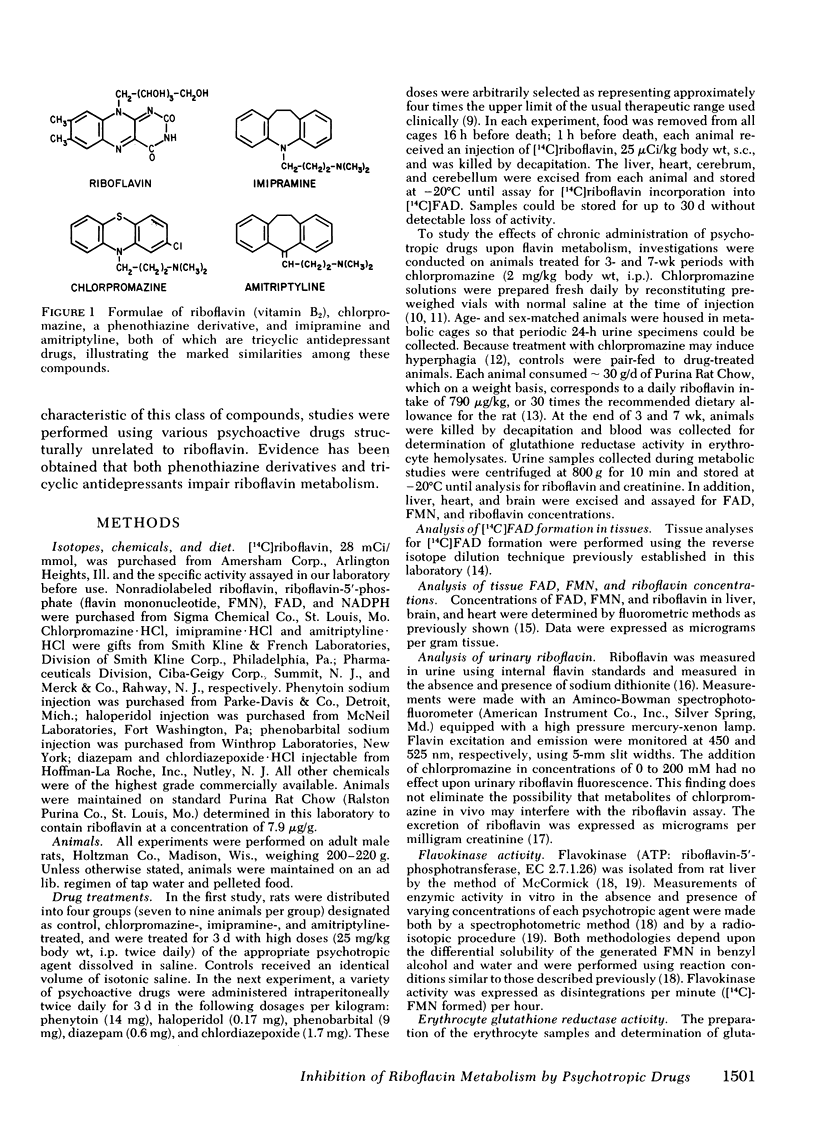

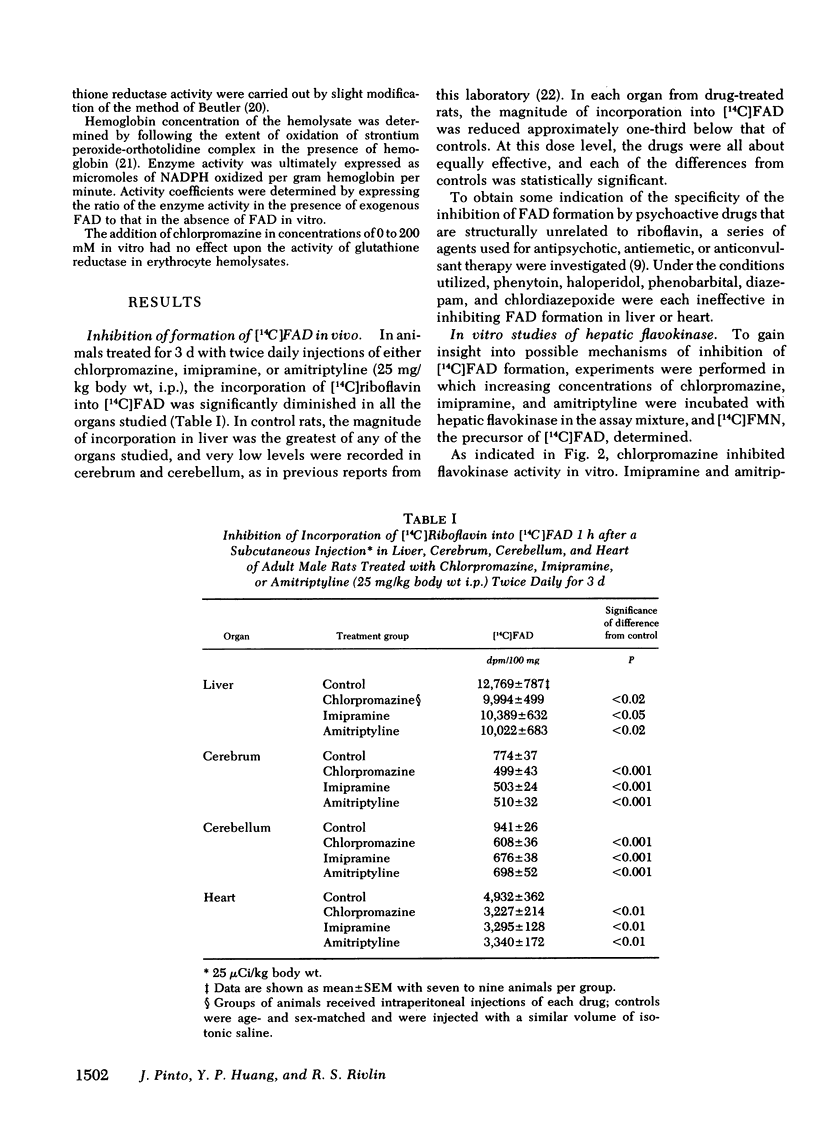

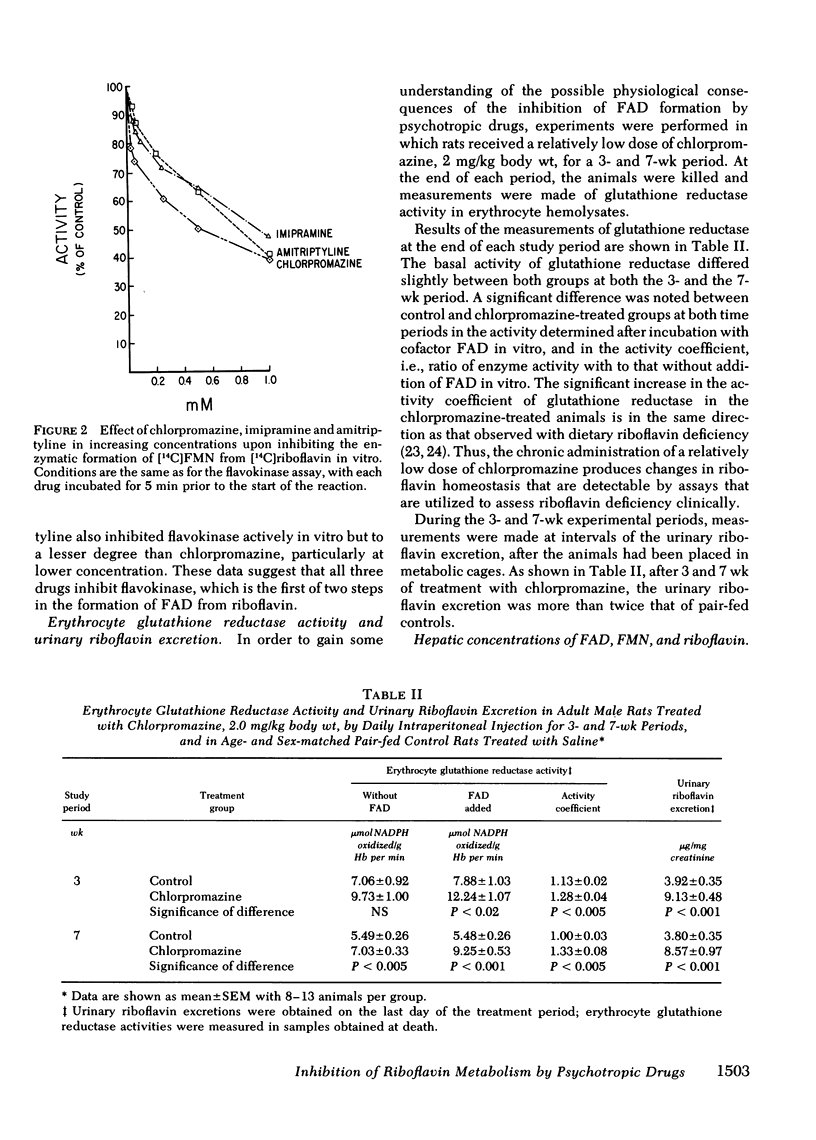

Prompted by recognition of the similar structures of riboflavin (vitamin B2), phenothiazine drugs, and tricyclic antidepressants, our studies sought to determine effects of drugs of these two types upon the conversion of riboflavin into its active coenzyme derivative, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) in rat tissues. Chlorpromazine, a phenothiazine derivative, and imipramine and amitriptyline, both tricyclic antidepressants, each inhibited the incorporation of [14C]riboflavin into [14C]FAD in liver, cerebrum, cerebellum, and heart. A variety of psychoactive drugs structurally unrelated to riboflavin were ineffective. Chlorpromazine, imipramine, and amitriptyline in vitro inhibited hepatic flavokinase, the first of two enzymes in the conversion of riboflavin to FAD.

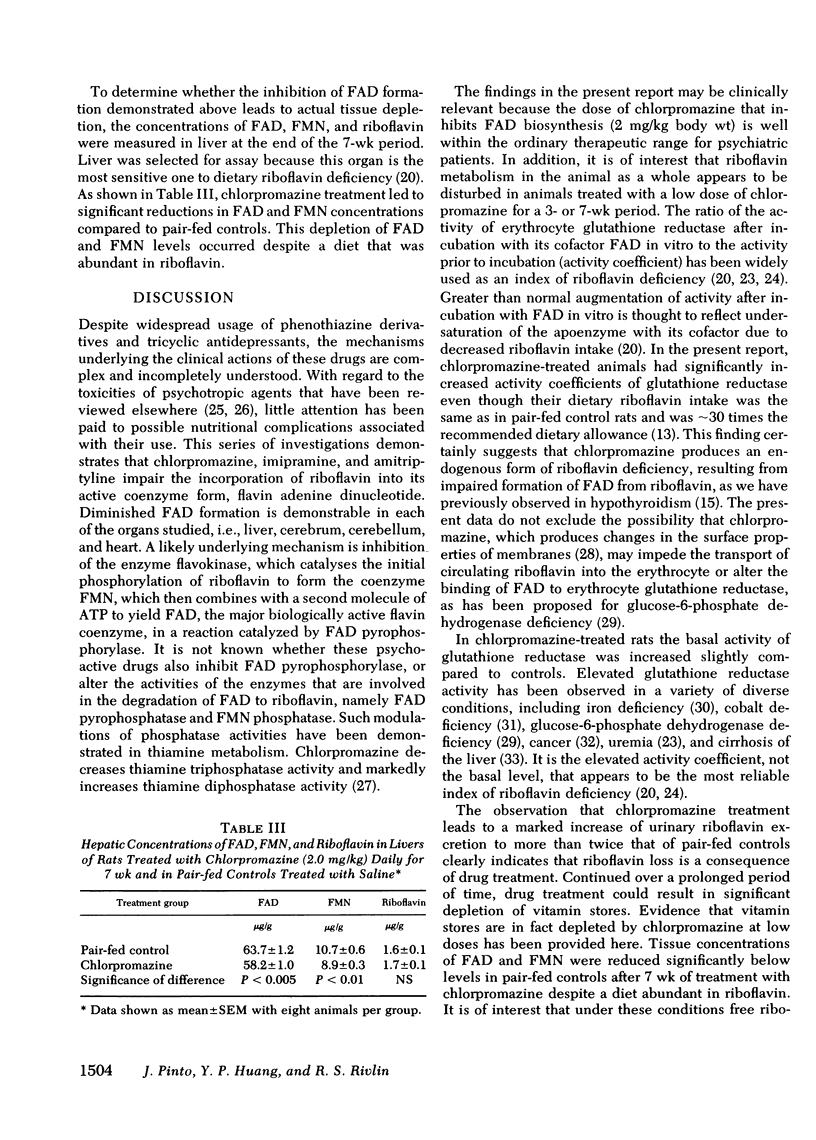

Evidence was obtained that chlorpromazine administration for a 3- or 7-wk period at doses comparable on a weight basis to those used clinically has significant effects upon riboflavin metabolism in the animal as a whole: (a) the activity coefficient of erythrocyte glutathione reductase, an FAD-containing enzyme used as an index of riboflavin status physiologically, was elevated, a finding compatible with a deficiency state, (b) the urinary excretion of riboflavin was more than twice that of age- and sex-matched pair-fed control rats, and (c) after administration of chlorpromazine for a 7-wk period, tissue levels of flavin mononucleotide and FAD were significantly lower than those of pair-fed littermates, despite consumption of a diet estimated to contain 30 times the recommended dietary allowance. The present study suggests that certain psychotropic drugs interfere with riboflavin metabolism at least in part by inhibiting the conversion of riboflavin to its coenzyme derivatives, and that as a consequence of such inhibition, the overall utilization of the vitamin is impaired.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bamji M. S. Glutathione reductase activity in red blood cells and riboflavin nutritional status in humans. Clin Chim Acta. 1969 Nov;26(2):263–269. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(69)90376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E. Effect of flavin compounds on glutathione reductase activity: in vivo and in vitro studies. J Clin Invest. 1969 Oct;48(10):1957–1966. doi: 10.1172/JCI106162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delides A., Spooner R. J., Goldberg D. M., Neal F. E. An optimized semi-automatic rate method for serum glutathione reductase activity and its application to patients with malignant disease. J Clin Pathol. 1976 Jan;29(1):73–77. doi: 10.1136/jcp.29.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfernik J. G. The asymmetric distribution of chlorpromazine and its quaternary analogue over the erythrocyte membrane. Biochem Pharmacol. 1977 Dec 15;26(24):2411–2416. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(77)90450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIELDING H. E., LANGLEY P. E. A simple method for measurement of hemoglobin in serum and urine. Am J Clin Pathol. 1958 Dec;30(6):528–529. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/30.6.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatz G. Enhanced binding of FAD to glutathione reductase in G6PD deficiency. Nature. 1970 May 23;226(5247):755–755. doi: 10.1038/226755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GABAY S., HARRIS S. R. STUDIES OF FLAVIN ADENINE DINUCLEOTIDE-REQUIRING ENZYMES AND PHENOTHIAZINES-I. INTERACTIONS OF CHLORPROMAZINE AND D-AMINO ACID OXIDASE. Biochem Pharmacol. 1965 Jan 1;14:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(65)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay S., Harris S. R. Inhibition of flavoenzymes by phenothiazines. Agressologie. 1968 Jan-Feb;9(1):79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay S., Harris S. R. Studies of flavin-adenine dinucleotide-requiring enzymes and phenothiazines. 3. Inhibition kinetics with highly purified D-amino acid oxidase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1967 May;16(5):803–812. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(67)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay S., Harris S. R. Studies of flavin-adenine dinucleotide-requiring enzymes and phenothiazines. II. Structural requirements for D-amino acid oxidase inhibition. Biochem Pharmacol. 1966 Mar;15(3):317–322. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(66)90302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombe S., Verjee Z. H. Erythrocyte glutathione metabolism in cobalt-deficient goats. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1976;46(2):165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata H., Baba A., Matsuda T., Terashita Z. Properties of thiamine di- and triphosphatases in rat brain microsomes: effects of chlorpromazine. J Neurochem. 1975 Jun;24(6):1209–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1975.tb03900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARREMAN G., ISENBERG I., SZENT-GYORGYI A. On the mechanism of action of chlorpromazine. Science. 1959 Oct 30;130(3383):1191–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.130.3383.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KING T. E., HOWARD R. L., WILSON D. F., LI J. C. The partition of flavins in the heart muscle preparation and heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1962 Sep;237:2941–2946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljunggren B. Phenothiazine phototoxicity: toxic chlorpromazine photoproducts. J Invest Dermatol. 1977 Oct;69(4):383–386. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12510313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill A. H., Addison R., McCormick D. B. Induction of hepatic and intestinal flavokinase after oral administration of riboflavin to riboflavin-deficient rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1978 Sep;158(4):572–574. doi: 10.3181/00379727-158-40248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muttart C., Chaudhuri R., Pinto J., Rivlin R. S. Enhanced riboflavin incorporation into flavins in newborn riboflavin-deficient rats. Am J Physiol. 1977 Nov;233(5):E397–E401. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1977.233.5.E397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto J., Wolinsky M., Rivlin R. S. Chlorpromazine antagonism of thyroxine-induced flavin formation. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979 Mar 1;28(5):597–600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran M., Iyer G. Y. Erythrocyte glutathione reductase in iron deficiency anaemia. Clin Chim Acta. 1974 Apr;52(2):225–229. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(74)90214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin R. S., Menendez C., Langdon R. G. Biochemical similarities between hypothyroidism and riboflavin deficiency. Endocrinology. 1968 Sep;83(3):461–469. doi: 10.1210/endo-83-3-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R. G., McHugh P. R., Bloom F. E. Chlorpromazine induced hyperphagia in the rat. Psychopharmacol Commun. 1975;1(1):37–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J. B. Tricyclic antidepressant toxicity. Clin Toxicol. 1977;11(4):391–402. doi: 10.3109/15563657708988202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawata Y., Tanaka K. R. Regulatory mechanism of glutathione reductase activity in human red cells. Blood. 1974 Jan;43(1):99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]