Abstract

The authors evaluated emotional distress among 9th-12th grade students, and examined whether the association between LGBT status and emotional distress was mediated by perceptions of having been treated badly or discriminated against because others thought they were gay or lesbian. Data come from a school-based survey in Boston, MA (n=1,032); 10% were LGBT, 58% were female, and age ranged from 13-19 years. About 45% were Black, 31% were Hispanic, and 14% were White. LGBT youth scored significantly higher on the scale of depressive symptomatology. They were also more likely than heterosexual, non-transgendered youth to report suicidal ideation (30% vs. 6%, p<0.0001) and self-harm (5% vs. 3%, p<0.0001). Mediation analyses showed that perceived discrimination accounted for increased depressive symptomatology among LGBT males and females, and accounted for an elevated risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation among LGBT males. Perceived discrimination is a likely contributor to emotional distress among LGBT youth.

Keywords: Emotional distress, LGBT, self-harm, suicide, depression

Introduction

Accumulating evidence indicates that adolescents who have same-sex sexual attractions, who have had sexual or romantic relationships with persons of the same sex, or who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual are more likely than heterosexual adolescents to exhibit symptoms of emotional distress, including depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Faulkner & Cranston, 1998; Fergusson, Horwood, & Beautrais, 1999; Galliher, Rostosky, & Hughes, 2004; Garofalo, Wolf, Kessel, Palfrey, & DuRant, 1998; Garofalo, Wolf, Wissow, Woods, & Goodman, 1999; Lock & Steiner, 1999; Remafedi, French, Story, Resnick, & Blum, 1998; Russell & Consolacion, 2003; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Safren & Heimberg, 1999; Ueno, 2005). For instance, data from the 2007 Washington, D.C. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) system showed that 40% of youth who reported a minority sexual orientation indicated feeling sad or hopeless in the past two weeks, compared to 26% of heterosexual youth (District of Columbia Public Schools, 2007). Those data also showed that lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth were more than twice as likely as heterosexual youth to have considered attempting suicide in the past year (31% vs. 14%).

A much smaller body of research suggests that adolescents who identify as transgender or transsexual also experience increased emotional distress (Di Ceglie, Freedman, McPherson, & Richardson, 2002; Grossman & D'Augelli, 2006; Grossman & D'Augelli, 2007). In a study based on a convenience sample of 55 transgender youth aged to 15-21 years, the authors found that more than one-fourth reported a prior suicide attempt (Grossman & D'Augelli, 2007). All of those reporting having attempted suicide attributed their urge to take their own lives to being transgender. However, there is a paucity of research on transgender adolescents that comes from larger population-based samples, such as the YRBS surveys, because these surveys do not ask questions to identify transgender youth.

Explanations for Increased Levels of Emotional Distress among LGBT Youth

One potential explanation for the elevated risk of emotional distress among adolescents with a minority sexual orientation or transgendered identity (hereafter referred to as LGBT) is that these youth must deal with stressors related to having a stigmatized identity (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). While there has been substantially increased visibility of LGBT issues in public discourse and in popular culture (Gibson, 2006; Russell, 2002), and although attitudes towards same-sex relationships have generally become more favorable (Avery, Chase, Johansson, Litvak, Montero, & Wydra, 2007), social stigma associated with homosexuality, as well as toward deviation from socially-prescribed gender roles, remains pervasive, particularly for young people (Herek, 2002; Hoover & Fishbein, 1999; Horn, 2006; Taywaditep, 2001). Even though important efforts to improve support for LGBT youth have been undertaken – such as development of supportive policies and the establishment of student groups such as Gay-Straight Alliances – LGBT youth still face heightened difficulties as compared to their heterosexual, non-transgendered classmates (Fetner & Kush, 2008; Hansen, 2007; Szalacha, 2003). LGBT adolescents live in social environments in which they may be exposed to negative experiences, including social rejection and isolation, diminished social support, discrimination, and verbal and physical abuse (Lombardi, Wilchins, Priesing, & Malouf, 2001; Meyer, 1995; Savin-Williams, 1994; Wyss, 2004).

Although bullying and physical victimization are problems among youth in general, they are particularly important issues for LGBT youth. Simply put, LGBT adolescents are more likely than heterosexual, non-transgendered adolescents to report being bullied or physically assaulted, (Garofalo, Wolf, Kessel, Palfrey, & DuRant, 1998; Harry, 1989; Pilkington & D'Augelli, 1995; Robin, Brener, Donahue, Hack, Hale, & Goodenow, 2002; Russell, Franz, & Driscoll, 2001; Waldo, Hesson-McInnis, & D'Augelli, 1998; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, & Craig, 2003) and much of the bullying and victimization has strong anti-homosexual overtones (Poteat & Espelage, 2005). YRBS data from Washington D.C. show that 31% of youth with a minority sexual orientation reported having been bullied over the past year, compared to 17% of heterosexual youth (District of Columbia Public Schools, 2007). YRBS data from both Washington, D.C. and Massachusetts show that youth with a minority sexual orientation are more likely to report having skipped school in the past month because they felt unsafe there (26% and 20%, respectively), as compared to their heterosexual peers (11% and 6%) (District of Columbia Public Schools, 2007; Faulkner & Cranston, 1998). Massachusetts YRBS data also show that 45% of youth with a minority sexual orientation report having had their personal property stolen or deliberately damaged at school, compared to 29% of opposite-sex-only experienced adolescents (Faulkner & Cranston, 1998).

A growing body of research supports the theory that negative experiences resulting from LGBT stigma can lead to chronic stress that contributes to emotional distress among LGBT adolescents and adults (Bontempo & D'Augelli, 2002; Clements-Nolle, Marx, & Katz, 2006; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 2003; Murdock & Bolch, 2005; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, & Craig, 2005). Most studies investigating the consequences of stressors on the mental health of LGBT youth have been derived from community-based convenience samples of LGBT youth (e.g., (D'Augelli, 2002; D'Augelli, Grossman, Salter, Vasey, Starks, & Sinclair, 2005; D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Friedman, Koeske, Silvestre, Korr, & Sites, 2006; Hershberger & D'Augelli, 1995; Murdock & Bolch, 2005; Pilkington & D'Augelli, 1995; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002; Savin-Williams, 1989; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003)). These studies typically find support for an association between stressors associated with being LGBT and poorer mental health. For example, in two community-based studies of more than 500 lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth, D'Augelli and colleagues found a strong link between lifetime victimization directly attributable to one's minority sexual orientation (e.g., verbal abuse, threats of violence, physical assault, and sexual assault) and mental health problems (D'Augelli, 2002; D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006). In these studies, males reported more sexual orientation-related victimization than females.

Less frequently, information has come from school-based studies, sometimes representative, in which study participants are not selected on the basis of their minority sexual orientation (e.g., Bontempo & D'Augelli, 2002; Bos, Sandfort, de Bruyn, & Hakvoort, 2008; Williams, Connolly, Pepler, & Craig, 2005). One of the earliest school-based studies carried out by Bontempo and D'Augelli (2002) found that 10% of lesbian and bisexual females and 24% of gay and bisexual males reported high levels of past-year victimization at school (≥10 times in the past year), compared to 1% of heterosexual females and 3% of heterosexual males. Moreover, those lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth exposed to high levels of victimization had elevated rates of past-year suicide attempts than heterosexual youth exposed to high levels of victimization. The reasons that high levels of victimization appear to be more detrimental to the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth as compared to heterosexual youth remain unclear. It is possible that those youth have less social support or fewer resources to cope with victimization experiences, or that their victimization experiences are more severe (Dunbar, 2006).

Limitations of Prior Research

Studies with community and population-based samples have important strengths and notable limitations for investigating the impact of LGBT-associated stressors on the health of LGBT youth (Corliss, Cochran, & Mays, In press). Studies with community samples contain LGBT-specific measures to allow for a more in-depth assessment tailored to the experiences of the population. However, lack of generalizability is a major limitation. Participants in community samples are frequently recruited from places such as LGBT community social and support groups and pride events, and are therefore likely to be different from the larger population of youth expressing a minority sexual orientation or transgender identity in many ways (Corliss, Cochran, & Mays, In press). An additional limitation is that studies with community samples lack a comparable heterosexual, non-transgendered group necessary to quantify differences. While studies with population-based samples, such as school-based studies, are more generalizable, they frequently lack LGBT-specific measures helpful for investigating mechanisms accounting for the greater levels of emotional distress among LGBT youth.

Despite growing evidence of the emotional toll of negative experiences related to LGBT stigma, gaps in knowledge remain. For example, only community-based studies of LGBT youth have assessed the mental health impact of maltreatment specifically attributable to LGBT status. In contrast, the extant school-based studies of youth have used global measures of maltreatment, typically victimization occurring at school, which are not explicitly linked to sexual orientation. For example, YRBS questionnaires ask about victimization generally, without regard to the victim's perceptions about why he or she was targeted. Consequently, we are unsure about the extent to which LGBT youths' maltreatment experiences are direct consequences of others' negative LGBT attitudes and behaviors. In addition, representative studies have yet to investigate how perceived discrimination on the basis of minority sexual orientation accounts for differences in mental health status of heterosexual and LGBT youth. Directly examining how discrimination based on minority sexual orientation may play a role in the greater emotional distress among LGBT youth has the potential to inform targets for interventions to improve the mental health of LGBT youth.

Another area which deserves additional investigation is the extent to which there may be gender/sex differences in mechanisms leading to LGBT youths' greater emotional distress. Some community studies of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth generally point to a greater amount of sexual orientation-related maltreatment among males compared to females (D'Augelli, 2002; D'Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002). However, another study did not find differences between lesbian, gay, and bisexual males and females in reports of stressful life events related to sexual orientation such as having trouble with parents, siblings, teachers, and classmates (Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). To what extent this variation may differentially impact the mental health of LGBT males and females remains unknown.

The Current Study

In this study we explore the contribution of perceived discrimination on the basis of being lesbian, gay, or bisexual to elevated emotional distress among LGBT youth. To address prior methodological limitations and to advance knowledge of the impact of sexual orientation-related discrimination on LGBT youth, we capitalized on data collected from a representative sample of public high school students in Boston, MA. We examine the associations among LGBT status, perceived discrimination on the basis of minority sexual orientation, and three indicators of emotional distress.

The first aim was to estimate the prevalence of indicators of emotional distress among LGBT youth, including depressive symptomatology, self-harm, and suicidal ideation. Self-harm – which includes self-inflicted painful acts such as cutting or burning oneself – is increasingly recognized as a strong risk factor for suicide and suicide attempts, and is also indicative of depression (Hawton, Rodham, Evans, & Weatherall, 2002; Hawton, Zahl, & Weatherall, 2003). Data from representative samples of youth have yet to quantify differences between LGBT and heterosexual, non-transgendered youth in their risk for deliberate self-harm. Based on the existing literature, we expected that LGBT youth would have significantly higher levels of emotional distress as compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered youth. The second aim was to estimate the extent to which LGBT youth perceived that they had been discriminated against on the basis of sexual orientation. We projected that LGBT youth would be more likely than heterosexual, non-transgendered youth to report this type of discrimination. Our final aim was to examine whether perceived discrimination could explain the association between LGBT status and emotional distress. We hypothesized that perceived discrimination on the basis of minority sexual orientation would mediate, at least partially, this association. For each aim, we investigate differences by sex/gender through stratified analyses.

Methods

Study Sample

Data for this investigation come from the 2006 Boston Youth Survey (BYS), a biennial survey of 9th-12th grade students in selected Boston Public Schools. We used a two-stage, stratified random sampling strategy. The first sampling frame consisted of all 38 high schools in the Boston Public Schools system. Thirty schools were randomly selected for the survey, with a probability of selection proportional to each school's enrollment size. Eighteen schools agreed to participate. The mean high school drop-out rate for participating schools was not statistically different from the rate for non-participating schools.

Among the 18 participating schools, we generated a numbered list of unique homeroom classrooms within each school. Classrooms comprised of students with severe emotional or cognitive disabilities were excluded. Classrooms were stratified by grade, and then randomly selected for survey administration within each grade. Those classrooms that listed fewer than five students were skipped and the next randomly selected classroom was chosen. Selection continued until the total number of students to be surveyed ranged from 100-125 per school. In the two selected schools that had total enrollments close to 100, all classrooms in the school were sampled.

Data Collection

The BYS data collection instrument was developed by study staff. It covered a range of topics (e.g., health behaviors, use of school and community resources, developmental assets, risk factors), and had a particular emphasis on violence. The paper-and-pencil survey was administered in classrooms by trained staff in the spring of 2006. Survey administrators completed a brief training program prior to going into the schools.

Surveys were not marked with any information that could identify an individual. Passive consent was sought from students' parents prior to survey administration. Less than 1% of students were prohibited by their parents from participating. Survey administrators read an introduction and the informed consent statement prior to distributing the survey. Seventy of the 1,323 invited students (5.3%) declined to participate. Survey administrators remained in the room and were available to answer questions throughout the 50 minutes allotted for the survey. The Human Subjects Committee at the Harvard School of Public Health approved all procedures for this research project.

Measures

We used the Modified Depression Scale (MDS) to measure depressive symptomatology (Dahlberg, Toal, Swahn, & Behrens, 2005). The MDS is a shortened version of the DSM Scale for Depression (Kelder, Murray, Orpinas, Prokhorov, McReynolds, Zhang, et al., 2001; Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1997), and assesses depressive symptomatology within the past 30 days. It has been used in other studies and has been reported to have high internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.74 or greater (Bosworth, Espelage, & Simon, 1999; Dahlberg, Toal, Swahn, & Behrens, 2005; Goldstein, Walton, Cunningham, Trowbridge, & Maio, 2007). The MDS inquires about the frequency of six symptoms of depression including: sadness, irritability, hopelessness, sleep disturbance, difficulty concentrating, and eating problems. Based on data from pilot work, we dropped the item on eating problems, resulting in a 5-item scale. Each item measured the frequency of a symptom on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), for a total score range of 5-25, with higher scores indicating more frequent depressive symptoms. Because the total score includes the sum of the scores on all 5 items, students with missing values for any of the five items did not have a total score.

In addition to depressive symptomatology, we measured two other indicators of emotional distress. Students were asked about suicidal ideation (“Did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”) and acts of self-harm (“Did you ever cut or otherwise injury yourself on purpose?”), in the 12 months preceding the survey. The item on suicidal ideation was taken from the 2005 YRBS questionnaire (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005).

To assess sexual orientation respondents were asked to identify which of six categories best described themselves: (1) heterosexual, (2) mostly heterosexual, (3) bisexual, (4) mostly homosexual, (5) homosexual/ gay or lesbian, and (6) not sure. This measure has been used with adolescents in several population-based studies (Austin, Roberts, Corliss, & Molnar, 2008; Austin, Ziyadeh, Fisher, Kahn, Colditz, & Frazier, 2004; Remafedi, Resnick, Blum, & Harris, 1992). Those who indicated that they were mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly homosexual, or homosexual were coded as having a minority sexual orientation. Students were also asked whether they considered themselves to be transgendered (yes, no, don't know). Students who confirmed that they were transgendered and/or who had a minority sexual orientation were categorized as LGBT, i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered. To assess perceived discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, students were asked to answer yes or no to the following question: “Sometimes people feel they are discriminated against or treated badly by other people. In the past 12 months, have you felt discriminated against because someone thought you were gay, lesbian, or bisexual?”.

Additional covariates included age, sex, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and race. We measured sex with the following item: “What is your sex or gender?”, which had male and female as response options. To assess race, students were asked to indicate if they were: (1) White; (2) American Indian or Alaska Native; (3) Asian; (4) Black or African American; (5) Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; or (6) Some Other Race. Students were permitted to mark all options that applied to them. For this particular analysis we combined Hispanic/Latino ethnicity and race to create a race/ethnicity variable with the following four levels: (1) Hispanic/Latino; (2) Non-Hispanic, Black/African American; (3) Non-Hispanic, White; and (4) Other, which includes bi- or multi-racial students, Asians, Native Americans, and those who were not Hispanic and who could not specify a race.

Data Analysis

As a first step in constructing the analytic sample we excluded respondents who did not sufficiently complete the questionnaire. We then excluded respondents who skipped sex, or all of the items assessing emotional distress, including the five depressive symptomatology questions and the items on suicidal ideation and self-harm. For multivariate analyses we excluded respondents without complete data on any of the covariates in the model from the procedure.

Once the analytic sample had been constructed we conducted descriptive analyses to assess the frequency or level of important covariates, including: sexual orientation, transgender status, LGBT status, age, race/ethnicity, sex, self-harm, suicidal ideation, depressive symptomatology, and perceived discrimination on the basis of minority sexual orientation status. We also assessed the degree of association among covariates. We computed generalized linear regression models and estimated odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals to describe the association between suicidal ideation, self-harm, and perceived discrimination by race/ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, and transgender status. We also generated odds ratios to examine the association between perceived discrimination and self-harm and suicidal ideation. To examine whether there were age differences by suicidal ideation, self-harm, and perceived discrimination, we conducted simple t-tests. We also conducted t-tests or one-way ANOVA models to examine the difference in means on the scale for depressive symptomatology by race/ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, transgender status, and perceived discrimination. Finally, we used a Pearson's R correlation coefficient to examine the association between age and depressive symptomatology. The analyses described above were conducted with SAS software version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., 2008).

To test the hypothesis that perceived discrimination on the basis of minority sexual orientation was a mediator of the association between LGBT status and emotional distress, we followed the steps outlined in Baron and Kenny (1986) for each of the three indicators of emotional distress. The Baron and Kenny method has been used in studies assessing mediation in similar samples (Bos, Sandfort, de Bruyn, & Hakvoort, 2008; Busseri, Willoughby, Chalmers, & Bogaert, 2008), and involves a series of regression equations in which the following associations are estimated: (1) the predictor – LGBT status – with each outcome variable; (2) the predictor and the hypothesized mediator (i.e., perceived discrimination); and (3) the predictor with each outcome variable, while statistically controlling for the hypothesized mediator. For each set of regression equations, if there was a statistically significant and meaningful association found in the first two tests, we conducted a final mediation model. To account for the fact that students were clustered within school, we used the MLwiN software to estimate the regression models (Centre for Multilevel Modeling, 2008). MLwiN uses the iterative generalized least squares algorithm, explicitly models dependence between observations, and adjusts the standard errors to control for clustering (Rasbash, Steele, Browne, & Prosser, 2004).

To quantify the extent to which perceived discrimination mediated the association between LGBT status and emotional distress, we calculated the percent that the regression coefficients changed and the Sobel test related to this magnitude of change (Sobel, 1982). If perceived discrimination emerged as strong and statistically significant in the final model and there was attenuation of the effect of LGBT status, then mediation was deemed to be in effect. We expected to find a statistically significant positive association between LGBT status and each of the three indicators of emotional distress.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Twelve hundred fifty-three surveys were collected in the 18 schools. The surveys of 38 students (3%) were excluded from data analysis; 35 because they left at least 80% of the items unanswered, and 3 because of erratic answering patterns. An additional 183 respondents were excluded from the analysis sample because they had missing data on sex (n=11) or on all three indicators of emotional distress (n=172), resulting in a total sample size of 1,032.

The sample reflected the racial and ethnic diversity of Boston public high school students. More than a quarter (30.7%) were Hispanic/ Latino, 44.8% were non-Hispanic Black, 13.7% were non-Hispanic White, and 10.8% were Asian, Native Hawaii or Other-Pacific Islander, bi- or multi-racial, or reported being of another race category. The age of respondents ranged from 13 to 19 years, with a mean of 16.3 (SD=1.3). More than half (58.3%) of the respondents were female.

Table 1 shows the distribution of sexual orientation and transgendered status of respondents. It remains unclear whether those students who checked “not sure” for sexual orientation or “don't know” for transgender are questioning their identity or did not understand the question. For analyses, we coded those students who answered don't know or unsure as having missing data on sexual orientation, transgender status, or LGBT status. Nearly 10% of the respondents identified themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgendered (LGBT) (103 out of 1,032).

Table 1. Sexual Orientation and Transgendered Status of Respondents, n=1,032.

| Sexual Orientation | Transgender Status | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Yes” | “No” | “Don't Know” | Skipped | Total | |||||

| % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | % | (n) | ||

| “Heterosexual” | 0.6% | (5) | 89.7% | (760) | 4.8% | (41) | 4.8% | (41) | 847 |

| “Mostly Heterosexual” | 5.7% | (3) | 90.6% | (48) | 3.8% | (2) | -- | (0) | 53 |

| “Bisexual” | 11.5% | (3) | 76.9% | (20) | 11.5% | (3) | -- | (0) | 26 |

| “Mostly Homosexual” | -- | (0) | 100.0% | (3) | -- | (0) | -- | (0) | 3 |

| “Gay or Lesbian” | 9.1% | (1) | 90.9% | (10) | -- | (0) | -- | (0) | 11 |

| “Not Sure” | 20.8% | (5) | 41.7% | (10) | 29.2% | (7) | 8.3% | (2) | 24 |

| Skipped Item | -- | (0) | 58.8% | (40) | 17.7% | (12) | 23.5% | (16) | 68 |

| Total | 17 | 891 | 65 | 59 | 1,032 | ||||

Note. The dark gray shading represents respondents who are classified as transgendered (n=17); the comparison group includes non-transgendered youth (n=891). The black shading reflects the number of respondents who are classified as having a minority sexual orientation (n=93); the comparison group includes heterosexual youth (n=847). The light gray shading represents respondents who are classified as LGBT (n=103); the comparison group includes heterosexual, non-transgendered youth (n=760).

Demographic Differences in Sexual Orientation and Transgender Status

Girls were significantly more likely than boys to report a minority sexual orientation (including being mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly homosexual, or 100% homosexual) (13.3% vs. 5.3%, p<0.0001). Although more than half of the transgendered students chose female as their sex (11 out of 17), there were no statistically significant sex differences in transgendered status. There was little variation in sexual orientation by age and there were only modest differences by race/ethnicity. Whites were the most likely to have a minority sexual orientation (16.2%), followed by Hispanic/ Latinos (9.3%), those in the “other” race category (9.0%), and Blacks (8.5%) (p=0.07). There were too few transgendered students to discern differences by race/ethnicity or age.

Indicators of Emotional Distress

The mean score on the 5-item scale of depressive symptomatology was 13.4 (SD=4.0). (The scale ranged from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating more intense depressive symptomatology.) The scale demonstrated high internal consistency, as measured by a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.75. The depressive symptomatology score for girls (M=14.3, SD=3.9) was significantly higher than the score for boys (M=12.2, SD=3.9) (F statistic=69.3, p<0.0001). There were no statistically significant differences in depressive symptomatology by either age or race/ethnicity.

Less than one-tenth of the sample reported having engaged in self-harm (7.6%) or having experienced suicidal ideation (8.6%) in the 12 months preceding survey administration. Although girls had significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation compared to boys (11.0% vs. 5.2%, p=0.0014), there were only modest, non-statistically significant differences in self-harm by sex (8.0% vs. 7.1%, p=0.63). There was little difference in the prevalence of suicidal ideation and self-harm by race/ethnicity and age.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of indicators of emotional distress by LGBT status stratified by self-reported sex/gender. For these and most of the remaining analyses we analyzed LGBT youth as a single group (24 males, 79 females), with heterosexual, non-transgendered students as the comparison group (330 males, 430 females). This was done to maximize power and because results from individual group analyses (i.e., transgendered vs. not; minority sexual orientation vs. heterosexual) showed similar patterns (data not shown).

Table 2. Indicators of Emotional Distress Among Boston Youth, Stratified by Self-Reported Sex/Gender (n=863).

| Suicidal Ideation in the Past Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | (No.) | Odds Ratio | (95% CI) | |

| Female | ||||

| LGBT | 30.8% | (24) | 5.38 | (2.95, 9.80) |

| Heterosexual, Not Transgendered | 7.6% | (32) | ||

| Male | ||||

| LGBT | 29.2% | (7) | 10.67 | (3.73, 30.56) |

| Heterosexual, Not Transgendered | 3.7% | (12) | ||

| Self-Harm in the Past Year | ||||

| Percent | (No.) | Odds Ratio | (95% CI) | |

| Female | ||||

| LGBT | 14.3% | (11) | 2.17 | (1.04, 4.55) |

| Heterosexual, Not Transgendered | 7.1% | (30) | ||

| Male | ||||

| LGBT | 41.7% | (10) | 20.26 | (7.38, 55.62) |

| Heterosexual, Not Transgendered | 3.4% | (11) | ||

| Score on the Depressive Symptoms Scale* | ||||

| Mean (SD) | (No.) | F Statistic | P Value | |

| Female | ||||

| LGBT | 15.4 (4.1) | (77) | 5.70 | 0.0174 |

| Heterosexual, Not Transgendered | 14.2 (3.9) | (410) | ||

| Male | ||||

| LGBT | 13.6 (4.4) | (22) | 4.50 | 0.0346 |

| Heterosexual, Not Transgendered | 11.9 (3.6) | (315) | ||

Note. These analyses are restricted to respondents who did not have missing data on LGBT status (n=863). Of those, several respondents were missing data on suicidal ideation (n=28), self-harm (n=22), and depressive symptomatology (n=52).

A test of significant differences in means by group was conducted using a T test. Depressive symptomatology was assessed with a 5-item scale assessing frequency of symptoms, a higher score reflects more symptoms (range: 5-25).

Among both males and females, LGBT youth displayed more emotional distress as compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered youth as evidenced by significantly higher prevalence rates for suicidal ideation and self-harm. The prevalence of self-harm was particularly high among LGBT males; with 41.7% reporting (10 out of 24). LGBT youth also had significantly higher depressive symptomatology scores than heterosexual, non-transgendered youth.

Perceived Discrimination

About seven percent of the respondents reported that they had experienced discrimination because someone thought they were gay, lesbian, or bisexual. There were no notable differences in rates of perceived discrimination by age, race, or sex. Not surprisingly, youth with a minority sexual orientation were significantly more likely than heterosexual youth to report perceived discrimination (33.7% vs. 4.3%, p<0.0001). Similarly, a larger percentage of transgendered youth reported discrimination than non-transgendered youth (18.8% vs. 6.4%). LGBT youth as a whole had a substantially increased prevalence of perceived discrimination compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered youth (31.3% vs. 3.7%, p<0.0001). Among LGBT youth, a significantly larger percentage of males reported discrimination (12 out of 24, 50%) than LGBT females (19 out of 75, 25.3%).

Perceived Discrimination, LGBT Status, and Depressive Symptomatology

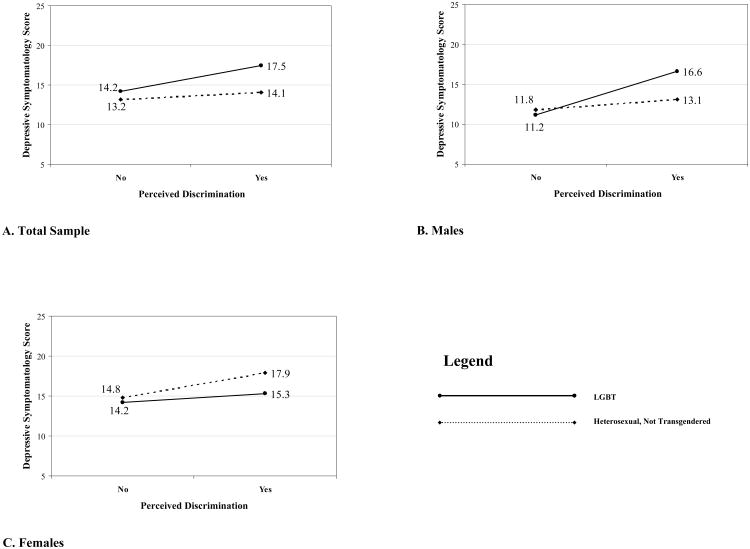

Respondents who reported having been discriminated against on the basis of minority sexual orientation were significantly more likely than those who had not felt this way to report self-harm (25.0% vs. 6.3%) and suicidal ideation (23.9% vs. 7.4%), and also had significantly higher mean scores on the depressive symptomatology scale (M=15.6, SD=4.3 vs. M=13.3, SD=3.9). We tested our expectation that the association between perceived discrimination and emotional distress would vary by LGBT status in multiple regression models. Specifically, we examined whether the interaction term of perceived discrimination and LGBT status was associated with increased levels of depressive symptomatology and found that the term was statistically significant for males (F= 5.22, p<0.05), but not for females (F=1.58, p=0.21) (Figure 1). (Due to limited power, we were unable to examine if perceived discrimination modified the association between LGBT status and self-harm or suicidal ideation in a similar manner as depressive symptoms.) Results indicate that, in the absence of perceived sexual orientation-based discrimination, LGBT males and females have similar levels of depressive symptoms as their heterosexual, non-transgendered peers. By contrast, in the face of discrimination, LGBT males have higher levels of depressive symptomatology as compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered boys, and LGBT girls had slightly lower levels of depressive symptomatology as compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered girls.

Figure 1. Depressive Symptomatology Scores by LGBT Status and Perceived Discrimination.

Note. Depressive symptomatology was assessed with a 5-item scale assessing frequency of symptoms, a higher score reflects more symptoms (range: 5-25).

Perceived Discrimination as a Mediator of the Association between LGBT Status and Emotional Distress

Because descriptive results showed that there were associations between LGBT status and depressive symptomatology, self-harm and suicidal ideation, and between LGBT status and perceived discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, we ran the full mediation analysis strategy. Table 3 summarizes the results of the regression analyses for each indicator of emotional distress stratified by self-reported sex/gender. We did not control for race/ethnicity or age in the mediation analyses because these variables were not significantly associated with LGBT status or indicators of emotional distress.

Table 3. The mediating effect of perceived discrimination on the association between LGBT status and emotional distress among Boston public high school students.

| Depressive Symptomatology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Girls (n=480) | Boys (n=326) | |||

|

| ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| b coefficient (se) | b coefficient (se) | b coefficient (se) | b coefficient (se) | |

| Orientation | ||||

| LGBT | 1.18 (0.48)* | 0.91 (0.52)∼ | 1.75 (0.79)* | 0.77 (0.85) |

| Heterosexual, non-transgendered | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Discrimination | ||||

| Yes | 2.21 (0.78)** | 2.58 (0.81)** | ||

| No | reference | reference | ||

|

| ||||

| Self-Harm | ||||

|

| ||||

| Girls (n=552) | Boys (n=398) | |||

|

| ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Orientation | ||||

| LGBT | 2.17 (1.04, 4.55) | 2.23 (1.00, 4.98) | 20.27 (7.40, 55.50) | 8.76 (2.69, 28.50) |

| Heterosexual, non-transgendered | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Discrimination | ||||

| Yes | 1.17 (0.35,3.88) | 3.29 (1.02, 10.67) | ||

| No | reference | reference | ||

|

| ||||

| Suicidal Ideation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Girls (n=552) | Boys (n=398) | |||

|

| ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Orientation | ||||

| LGBT | 5.39 (2.95, 9.84) | 5.32 (2.77, 10.23) | 8.58 (2.79, 26.44) | 5.37 (1.41,20.44) |

| Heterosexual, non-transgendered | reference | reference | reference | reference |

| Discrimination | ||||

| Yes | 1.26 (0.47, 3.35) | 3.06 (0.77.12.24) | ||

| No | reference | reference | ||

Note. Depressive symptomatology was assessed with a 5-item scale assessing frequency of symptoms, a higher score reflects more frequent symptoms (range: 5-25). Symbols are as follows:

p<0.10,

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

The mediation analyses for depressive symptomatology are presented in the top rows of Table 3. Model 1 for boys and girls shows that LGBT status was associated with significantly increased depressive symptoms for girls and boys. Model 2 shows the association between LGBT status and depressive symptoms adjusting for the effect of perceived discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. The addition of perceived discrimination attenuated the effect of LGBT status on depressive symptoms for girls by 23%. Evidence for the mediating role of perceived discrimination was obtained by conducting a Sobel test (Z-score 2.55, p<0.05). Among boys, the attenuation in the effect of LGBT status on depressive symptoms was even more pronounced (56%), and results of the Sobel test revealed that perceived discrimination was a highly significant mediator of this relationship (Z-score 2.81, p<0.005).

Results for self-harm stratified by sex are presented in the center rows of Table 3. Model 1 shows that LGBT girls and boys had significantly increased risks of self-harm compared to their heterosexual, non-transgendered peers. Model 2 shows that the addition of perceived discrimination slightly increased the effect of LGBT status on self-harm among girls by 2%, so that the effect of LGBT status was not statistically significant. The Sobel test for mediation revealed that perceived discrimination was not a significant intervening variable between LGBT status and acts of self-harm (Z-score 0.89, p=0.37) for girls. Among boys the effect of GBT status on self-harm was attenuated by 57% after accounting for the role of perceived discrimination. Results of the Sobel test indicated that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation strongly mediates the relationship between LGBT status and self-harm among boys (Z-score 4.16, p<0.0001).

Results of the stratified analysis for suicidal ideation are presented in the bottom rows of Table 3. Model 1 shows that LGBT girls and boys had significantly increased risks of suicidal ideation compared to their heterosexual, non-transgendered counterparts. Model 2 shows results of the final step of mediation analysis by regressing suicidal ideation on LGBT status while controlling for perceived discrimination among girls and boys. With the addition of the proposed mediator to the model the effect of LGBT status was reduced by 1%, among girls. Perceived discrimination did not mediate the relationship between LGBT status and suicidal ideation (Z-score 0.56, p=0.5) among girls. For boys, the main effect of LGBT status was attenuated by 37% with the addition of perceived discrimination to the model, and results of the Sobel test indicated that it was a significant mediator of the relationship between LGBT status and suicidal ideation (Z-score 3.5, p<0.001).

Discussion

Overview of Findings

In this study we used data from a representative sample of high school students in Boston, Massachusetts to examine: (1) emotional distress among LGBT youth as compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered youth; (2) whether LGBT youth were more likely to report being treated badly or discriminated against by others on the basis of presumed minority sexual orientation; and (3) the extent to which perceived discrimination was a mediator of the LGBT-emotional distress association. About 10% of youth in the sample identified as LGBT, a proportion similar to other youth samples (Austin, Roberts, Corliss, & Molnar, 2008; Austin, Ziyadeh, Fisher, Kahn, Colditz, & Frazier, 2004; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007). Similar to prior studies (District of Columbia Public Schools, 2007; Faulkner & Cranston, 1998; Fergusson, Horwood, & Beautrais, 1999; Galliher, Rostosky, & Hughes, 2004; Garofalo, Wolf, Kessel, Palfrey, & DuRant, 1998; Garofalo, Wolf, Wissow, Woods, & Goodman, 1999; Lock & Steiner, 1999; Remafedi, French, Story, Resnick, & Blum, 1998; Russell & Consolacion, 2003; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Safren & Heimberg, 1999; Ueno, 2005), we found that LGBT girls and boys in the sample were more likely than their heterosexual, non-transgendered peers to have emotional distress as demonstrated by higher levels of depressive symptoms, and a greater likelihood of reporting self-harm and suicidal ideation.

Also as expected, we also found that LGBT adolescents, were significantly more likely to report perceived discrimination on the basis of minority sexual orientation status. Almost one-third of LGBT youth reported this type of discrimination, compared to just 4% of heterosexual, non-transgendered youth. While few studies have examined this issue in population-based studies of youth, results are consistent with a study of U.S. adults in which lesbian, gay, and bisexual respondents were more likely than heterosexual respondents to report lifetime experiences of discrimination both in the form of discrete events such as being fired from a job or in day-to-day mistreatment by others (Mays & Cochran, 2001).

This study also uncovered important gender differences. Our data show that a larger percentage of LGBT males experienced discrimination (50%), than females (25%). This finding is consistent with community-based studies of LGBT youth, which found that males were more likely than females to report sexual orientation-related victimization (D'Augelli, 2002; D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; D'Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002).

An additional interesting finding relevant to gender differences was the interactive effect between discrimination and depressive symptomatology. Among those not reporting discrimination, LGBT youth and heterosexual, non-transgendered youth had similar levels of depressive symptomatology, across both sexes. However, among those who did report discrimination, LGBT males had significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms as heterosexual, non-transgendered males, whereas LGBT females actually had lower levels of depressive symptomatology than heterosexual, non-transgendered females. The results for LGBT girls were surprising. It is possible that factors contributing to depressive symptoms among LGBT males and females may be differently distributed or they have different magnitudes of effect. Alternatively, there could have been a ceiling effect for depressive symptoms among LGBT females due to the higher depressive symptoms scores observed among the females in general.

Our third second aim was to examine whether perceived discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation mediated the association between LGBT status and three indicators of emotional distress. Because research has demonstrated that sexual minority youth exist in a social environment which may be hostile in a variety of ways which could likely affect their mental health, we expected to see perceived discrimination account for higher levels of emotional distress among LGBT. Our data support this hypothesis for males, but not females. Discrimination accounted for one-third to over a half of the excess risk in indicators of emotional distress among LGBT males, as compared to heterosexual, non-transgendered males. Results were quite different for females. While perceived discrimination related to sexual orientation was found to be a modest mediator of the LGBT status-depressive symptoms association, it was not a mediator of the associations between LGBT status and self-harm or suicidal ideation.

These findings highlight the important role of perceived discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in explaining the association between LGBT status and depressive symptomatology among youth. Specifically, these results suggest that perceived discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation may more strongly account for increased depressive symptoms reported by LGBT boys, compared to the role that it plays in depressive symptoms among LGBT girls. However, future studies will need to replicate these findings before we can be confident that the observed gender differences are a real effect. These future studies will need to assess for differences based on subgroup of sexual minority status. As sexual orientation distributes differently among males and females, it is possible that our finding may reflect this distribution. Males are more likely to identify as either heterosexual or gay, whereas females are more likely to identify as bisexual or mostly heterosexual. These differences may mean that a greater proportion of minority sexual orientation males are “out” and affiliated with the LGBT community, as compared to minority sexual orientation females. Both of these factors are related to risk of sexual orientation-related victimization and discrimination (Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004; D'Augelli, Rilkington, & Hershberger, 2002).

Policy Directions

This study reports on the experiences of high school students in Boston, Massachusetts in 2006. Compared to other states in the United States, Massachusetts has taken important steps to expand rights to the LGBT population, including the adoption of same-sex marriage and policies to address LGBT inequalities. For example, in 1993, Massachusetts became the first state to establish a statewide program called the Safe Schools Program for Gay and Lesbian Youth for the purpose of enhancing support for and safety of LGBT youth (Szalacha, 2003). Despite the Program's success in improving the school climate for LGBT students and in increasing tolerance for diversity, the results of this study indicate that more work needs to be done. A significant proportion of LGBT students attending Boston public high schools say that they experienced discrimination in the past year because someone thought they were gay, lesbian, or bisexual. It is not surprising that these discrimination experiences appear to negatively impact the mental health of LGBT youth and to explain some of their excess risk for emotional distress. Population-based studies of adults document a robust association between perceived discrimination and poorer mental health (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999).

The good news is that expanding supportive policies and services in schools for LGBT adolescents may help to counter the detrimental effects of discrimination. Goodenow and colleagues (2006) documented the positive impact of LGBT support groups (e.g., Gay-Straight Alliances) and other efforts to improve the climate for LGBT high school students. For example, lesbian, gay, and bisexual high school students who attended schools with support groups had half the risk of reporting victimization and were less than one third as likely to report multiple suicide attempts. In addition, lesbian, gay, and bisexual students who perceived that there was a school staff member who they could turn to for help had a lower likelihood of reporting multiple suicide attempts.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations and should be carefully considered within the full body of literature on the well-being of sexual minority youth. Nearly one-third (382 of 1,215) of the Boston Youth Survey participants are not included in the analysis sample because they did not respond to items about sex, sexual orientation, transgendered status, depressive symptomatology, self-harm, or suicidal ideation. Because most of those were excluded from the analysis sample because they did not finish the questionnaire – and therefore did not answer the questions of primary interest – rather than because they skipped questions on depressive symptoms and sexual orientation, we do not believe the results were inconsistent with what they would have been if all participants were represented. Nonetheless, it is unclear how those participants' answers would have changed results.

As there were only about 100 sexual minority youth, we had limited power to conduct subgroup analyses. Classifying all the different types of sexual minority youth together into one category certainly masks some of the variation within the group (Savin-Williams, 2001). Future research should replicate this research with a larger population, and outline the extent to which results vary by whether youth are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender.

This study suggests that LGBT youth have significantly higher levels of emotional distress than heterosexual, non-transgendered youth, and that the perception of being discriminated against based on sexual orientation is a likely contributor to that distress, particularly for males. Taken with the entire body of literature on health among adolescent LGBT, our findings underscore the importance of understanding the experiences of these youths and supporting initiatives that address creating safe and supportive environments to ensure their emotional well-being (Galliher, Rostosky, & Hughes, 2004; Perrotti & Westheimer, 2001; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Silenzio, Pena, Duberstein, Cerel, & Knox, 2007).

Acknowledgments

The Boston Youth Survey 2006 (BYS) was funded by a grant from the CDC/NCIPC (U49CE00740) to the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center (David Hemenway, Principal Investigator). BYS was conducted in collaboration with the City of Boston and Mayor Thomas M. Menino. The survey would not have been possible without the participation of the faculty, staff, administrators, and students of Boston Public Schools. We also acknowledge the work of Daria Fanelli, Alicia Savannah, Angela Browne, and Steven Lippmann. We appreciate the assistance of Mary Vriniotis with data collection and management.

Note. The funding agency did not play a role in the design or conduct of this study, nor did they take part in the preparation of this manuscript. Individuals from the City of Boston contributed to survey development in that they made content recommendations. Both the CDC/NCIPC and the City of Boston have been notified that this manuscript is being submitted for publication.

Biographies

Joanna Almeida, ScD, is a post doctoral fellow at the Institute on Urban Health Research at Northeastern University. At the time of the study, she was a doctoral candidate in the Department of Society, Human Development and Health at the Harvard School of Public Health. Her research centers on the social determinants of mental health.

Renee M. Johnson, PhD, MPH is a Research Associate with the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center. She received a PhD and an MPH in Health Behavior & Health Education from The University of North Carolina School of Public Health. Her research focuses on risk behaviors among adolescents.

Heather L. Corliss, PhD, MPH is an Instructor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and a Research Scientist at Children's Hospital Boston. She received her PhD in Epidemiology and her MPH in Community Health Sciences, both from UCLA. Her major research interests include health disparities of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations, adolescent sexual identity development, adolescent substance use, and positive youth development.

Beth E. Molnar, ScD, is an Assistant Professor of Society, Human Development and Health at the Harvard School of Public Health. Her research interests include psychiatric epidemiology, community violence and their sequelae, and neighborhood protective factors affecting youth behavior.

Deborah Azrael, PhD, is Director of Research at the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center. She received her PhD in Health Policy from Harvard University. Her major research interests include public health approaches to suicide and youth violence prevention.

References

- Austin SB, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Molnar BE. Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort of “mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1015–1020. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Ziyadeh N, Fisher LB, Kahn JA, Colditz GA, Frazier AL. Sexual orientation and tobacco use in a cohort study of US adolescent girls and boys. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:317–322. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery A, Chase J, Johansson L, Litvak S, Montero D, Wydra M. America's changing attitudes toward homosexuality, civil unions, and same-gender marriage: 1977-2004. Soc Work. 2007;52(1):71–79. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, D'Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths' health risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(5):364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HM, Sandfort TG, de Bruyn EH, Hakvoort EM. Same-sex attraction, social relationships, psychosocial functioning, and school performance in early adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):59–68. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth K, Espelage DL, Simon TR. Factors associated with bullying behavior in middle school students. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:341–362. [Google Scholar]

- Busseri MA, Willoughby T, Chalmers H, Bogaert AF. On the association between sexual attraction and adolescent risk behavior involvement: Examining mediation and moderation. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):69–80. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005 National YRBS Data Users Manual. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Multilevel Modeling. MLwiN Software, Version 2.01. Bristol, United Kingdom: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. J Homosex. 2006;51(3):53–69. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Sampling approaches to studying mental health concerns in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. In: Meezan W, Martin JI, editors. Handbook of research with gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender populations. Routledge; In press. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR. Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2002;7(3):433–456. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Salter NP, Vasey JJ, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:646–660. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(11):1462–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, Hershberger SL. Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly. 2002;17:148–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg LL, Toal SB, Swahn M, Behrens CB. Measuring Violence-Related Attitudes, Behaviors, and Influences Among Youth: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ceglie D, Freedman D, McPherson S, Richardson P. Children and adolescents referred to a specialist gender identity development service: Clinical features and demographic characteristics. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2002;6(1) NP. [Google Scholar]

- District of Columbia Public Schools. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Sexual Minority Baseline Fact Sheet: Senior High School YRBS 2007 Baseline Findings for GLBQ Items. Washington, DC: District of Columbia Public Schools, HIV/AIDS Education Program; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar E. Race, gender, and sexual orientation in hate crime victimization: Identity politics or identity risk? Violence and Victims. 2006;21:323–337. doi: 10.1891/vivi.21.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner AH, Cranston K. Correlates of same-sex sexual behavior in a random sample of Massachusetts high school students. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):262–266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetner T, Kush K. Gay-straight alliances in high schools: Social predictors of early adoption. Youth & Society. 2008;40(1):114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Koeske GF, Silvestre AJ, Korr WS, Sites EW. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(5):621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliher RV, Rostosky SS, Hughes HK. School belonging, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in adolescents: An examination of sex, sexual attraction status, and urbanicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey SJ, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Wissow LS, Woods ER, Goodman E. Sexual orientation and risk of suicide attempts among a representative sample of youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(5):487–493. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R. From zero to 24-7: Images of sexual minorities on television. In: Castañeda L, Campbell SB, editors. News and sexuality: Media portraits of diversity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. pp. 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, Trowbridge MJ, Maio RF. Violence and substance use as risk factors for depressive symptoms among adolescents in an urban emergency department. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:276–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C, Szalacha L, Westheimer K. School support groups, other school factors, and the safety of sexual minority adolescents. Psychology in the Schools. 2006;43(5):573–589. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Transgender youth: invisible and vulnerable. J Homosex. 2006;51(1):111–128. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR. Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;37(5):527–537. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AL. School-based support for GLBT students: A review of three levels of research. Psychology in the Schools. 2007;44(8):839–848. [Google Scholar]

- Harry J. Sexual identity issues. In: Feinleib M, editor. Report of the Secretary's Task Force on Youth Suicide. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1989. pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatherall R. Suicide following deliberate self-harm: long-term follow-up of patients who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:537–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Heterosexuals attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. J Sex Res. 2002;39(4):264–274. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D'Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Dev Psychol. 1995;31(1):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover R, Fishbein HD. The development of prejudice and sex role stereotyping in white adolescents and white young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1999;20(3):431–448. [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS. Heterosexual adolescents' and young adults' beliefs and attitudes about homosexuality and gay and lesbian peers. Cognitive Development. 2006;21(4):420–440. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1200–1203. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelder SH, Murray NG, Orpinas P, Prokhorov A, McReynolds L, Zhang Q, Roberts R. Depression and substance use in minority middle-school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:761–766. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J, Steiner H. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth risks for emotional, physical, and social problems: results from a community-based survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(3):297–304. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199903000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi EL, Wilchins RA, Priesing D, Malouf D. Gender violence: transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. J Homosex. 2001;42(1):89–101. doi: 10.1300/j082v42n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Why lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender public health? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):856–859. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock TB, Bolch MB. Risk and Protective Factors for Poor School Adjustment in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual (LGB) High School Youth: Variable and Person-Centered Analyses. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42(2):159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti J, Westheimer K. When the Drama Club is Not Enough: Lessons from the Safe Schools Program for Gay and Lesbian Students. Boston: Beacon Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington NW, D'Augelli AR. Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. J Community Psychol. 1995;23(1):34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) scale. Violence and Victims. 2005;20(5):513–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash J, Steele F, Browne W, Prosser B. A User's Guide to MLwiN Version 2.0. London: London Institute of Education; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G, French S, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum R. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: Results of a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(1):57–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, Harris L. Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics. 1992;89(4 pt 2):714–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Ethnocultural differences in prevalence of adolescent depression. American Journal of Community Psychololgy. 1997;25:95–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649925737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin L, Brener ND, Donahue SF, Hack T, Hale K, Goodenow C. Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex sexual partners in representative samples of Vermont and Massachusetts high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(4):349–355. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay lesbian and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Queer in America: Citizenship for sexual minority youth. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6(4):258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Consolacion TB. Adolescent romance and emotional health in the United States: beyond binaries. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(4):499–508. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Franz BT, Driscoll AK. Same-sex romantic attraction and experiences of violence in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):903–906. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Heimberg RG. Depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and related factors in sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67(6):859–866. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. Statistical Applications Software, Version 9.1.3. Cary, N. C.: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams R. A critique of reseach on sexual minority youths. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:5–13. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Parental influences on the self-esteem of gay and lesbian youths: a reflected appraisals model. J Homosex. 1989;17(1-2):93–109. doi: 10.1300/J082v17n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Verbal and physical abuse as stressors in the lives of lesbian, gay male, and bisexual youths: associations with school problems, running away, substance abuse, prostitution, and suicide. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(2):261–269. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Suicide attempts among sexual-minority male youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(4):509–522. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silenzio VM, Pena JB, Duberstein PR, Cerel J, Knox KL. Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2017–2019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington, D.C.: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha L. Safer Sexual Diversity Climates: Lessons Learned from an Evaluation of Massachusetts Safe Schools Program for Gay and Lesbian Students [Article] American Journal of Education 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Taywaditep KJ. Marginalization among the marginalized: gay men's anti-effeminacy attitudes. J Homosex. 2001;42(1):1–28. doi: 10.1300/j082v42n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K. Sexual orientation and psychological distress in adolescence: examining interpersonal stressors and social support processes. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005;68:258–277. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo CR, Hesson-McInnis MS, D'Augelli AR. Antecedents and consequences of victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people: a structural model comparing rural university and urban samples. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26(2):307–334. doi: 10.1023/a:1022184704174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W. Questioning and sexual minority adolescents: high school experiences of bullying, sexual harassment and physical abuse. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2003;22(2):47–58. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W. Peer Victimization, Social Support, and Psychosocial Adjustment of Sexual Minority Adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2005;34(5):471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Wyss SE. ‘This was my hell’: The violence experienced by gender non-conforming youth in US high schools. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 2004;17(5):709–730. [Google Scholar]