Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between community measures of youth access to alcohol, enforcement of possession laws, and the frequency of youth alcohol use and related problems in those communities.

Design

Multi-level analysis of a cross-sectional student survey. Setting: Ninety-two communities in Oregon.

Participants

Students in grade 11 (ages 16–17) in each participating community.

Main outcome measures

Thirty-day frequency of alcohol use, binge drinking, use of alcohol at school, and drinking and driving.

Results

The rate of illegal merchant sales in the communities directly related to all four alcohol-use outcomes. There was also evidence that communities with higher minor in possession law enforcement had lower rates of alcohol use and binge drinking. The use of various sources in a community expanded and contracted somewhat depending on levels of access and enforcement.

Conclusions

This evidence provides much needed empirical support for the potential utility of local efforts to invest in increasing access control and possession enforcement.

Keywords: access, youth alcohol use, community enforcement

Introduction

Despite nationwide adoption of a 21-year-old minimum legal drinking age, national surveys consistently indicate that young people use alcohol frequently. For example, the 2002 Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey reveals that, by their senior year in high school, 78% of adolescents reported having experimented with alcohol, 49% report drinking within the previous month, 30% report being intoxicated during the previous month, and 29% report heavy episodic drinking (having five or more drinks in a row) during the past two weeks.1 Adolescent alcohol use, and especially heavy episodic drinking, is related to a wide variety of problem behaviors including drinking and driving, fighting, truancy, theft, assault and precocious and risky sexual activities.2,3,4,5 In addition to the immediate costs of underage drinking, early initiation to drinking may also be associated with other adverse outcomes including increased risk for the development of alcohol abuse and dependence later in life.6

Young people secure alcohol from a variety of commercial and social sources. Research indicates that while parties, friends, and adult purchasers, are the most common sources of alcohol among adolescents, 7, 8, 9, 10 commercial outlets are also used. Purchase surveys reveal that anywhere from 30% to 90% of outlets will sell alcohol to underage or apparent underage buyers, depending upon their geographical location.8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15

Traditionally, adolescent drinking and drinking problem prevention strategies have relied on school-based programs that attempt to reduce demand by providing new information, teaching new skills, or countering erroneous normative beliefs.16, 17 School-based programs, however, cannot provide a complete answer to the problem of drinking by young people, as evidenced by their somewhat limited success of in reducing alcohol use.18, 19, 20, 21 In part, this limitation arises because young people are immersed in a broader social context in which alcohol is readily available and glamorized.22

In contrast to school-based approaches, environmental strategies focus on policy, legal/regulatory changes, and enforcement.22, 23 Many environmental interventions directly target the availability of alcohol to underage drinkers by increasing personal or economic costs associated with obtaining or possessing it. Research shows that even moderate increases in enforcement can reduce sales of alcohol to minors by as much as 35% to 40%, especially when combined with strategic media advocacy and other community and policy activities. 13, 24

Although community-level restrictions on alcohol availability to youth and increased enforcement of minor possession laws are becoming increasingly important as local intervention strategies, 25 few studies have investigated the effects of alcohol availability and possession enforcement at the local level on consumption by young people.21, 22 As a result, little is known about how increased enforcement and resulting changes in local availability of alcohol are related to reductions in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among young people. Measures of availably of alcohol have been found to predict drinking and related problems in adults.26, 27, 28 More recently alcohol outlet density has been related to ease of underage purchase of alcohol29 and to frequency of underage drinking and driving and riding with drinking drivers.30 In the only currently published experimental study addressing changes in availability on youth drinking, 24 it was found that while a comprehensive environmentally focused program, which included enforcement of sales laws as one of several components, led to increases in checking age-identification by alcohol merchants and reduced sales to minors, it had no observed effects on drinking by high school students. In part, this absence of effects may have resulted from a lack of statistical power because of the relative small number of communities in the study (N = 15). This pattern of findings may also have resulted because adolescents often obtain alcohol from a variety of non-commercial sources that may not have been affected by the program.

In the current study, we examine the strength and variations in the relationship of social and commercial alcohol access sources to youth drinking in a population based survey conducted 93 communities. We further investigate the community level variations in the use of these sources as a function of community level indictors of local commercial availability and enforcement of minor in possession (MIP) laws.

Method

Design and Participants

Oregon Healthy Teens (OHT) is a survey-based study of influences on adolescent health behaviors that is designed to examine the relative impact of different prevention activities. We identified and recruited a population-based sample of communities in Oregon for participation in the study. The primary sampling unit (PSU) for the study was the community defined by the catchment area of a high school and the middle, junior, or elementary schools that feed into them. We randomly sampled, proportional to size, 115 such PSUs, and successfully recruited 93 (81%) to participate. We attempted to survey all of the 8th and 11th grade students in these PSUs annually during the spring of 2001 and 2002. Research staff administered student questionnaires in classrooms during a regular school period. For the present report, we analyzed data from the 11th grade students.

There were 16,694 11th grade student participants overall, with 7,486 (45%) surveyed in 2001 and 9,208 (55%) were surveyed in 2002. Three percent of the students were Native American, 4% were Asian, 1% were Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders, 2% were African American, 8% were Hispanic, and 85% were White, non-Hispanic. Fifty percent of the sample was female. The average 11th grade enrollment in a PSU was 288 (SD=141).

Measures

The OHT questionnaire consists of a demographics section that is completed by all students and a set of six modules ordered into sets of three so that any given student completes a randomly chosen set of three. This allowed the collection of data on a wide range of aspects of adolescent well-being as well as data on risk and protective factors. Approximately 50% of the students in a given classroom received any given survey module, and approximately 20% received any given pair of modules.

Alcohol Use

The primary outcome variables used in this analysis are student alcohol use in the last 30 days. Estimates of frequency of alcohol use were derived from students answers to the question, “During the PAST 30 DAYS, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?” with choices: 0 days, 1 or 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 6 to 9 days, 10 to 19 days, 20 to 29 days, and all 30 days.

Heavy episodic or “binge” drinking (excessive quantity of drinking) was assessed with the question, “During the PAST 30 DAYS, on how many days did you have five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is within a couple of hours?” The response choices were: 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 6 to 9 days, 10 to 19 days, and 20 or more days.

Alcohol use at school was measured by the question “During the PAST 30 DAYS, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol on school property?” with the same response choices as for the binge drinking question.

Drinking and driving/riding (DUI) was measured by the items “During the past 30 days, how many times did you …” “Drive a car or other vehicle when you had been drinking alcohol?” and “Ride in a car of other vehicle with a teenage driver who had been drinking alcohol?” Responses were “0 times,” “1 time,” “2 or 3 times,” “4 or 5 times,” and “6 or more times.” For the purposes of analysis, these two items were summed.

All these items are derived from the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey.31

Sources of alcohol

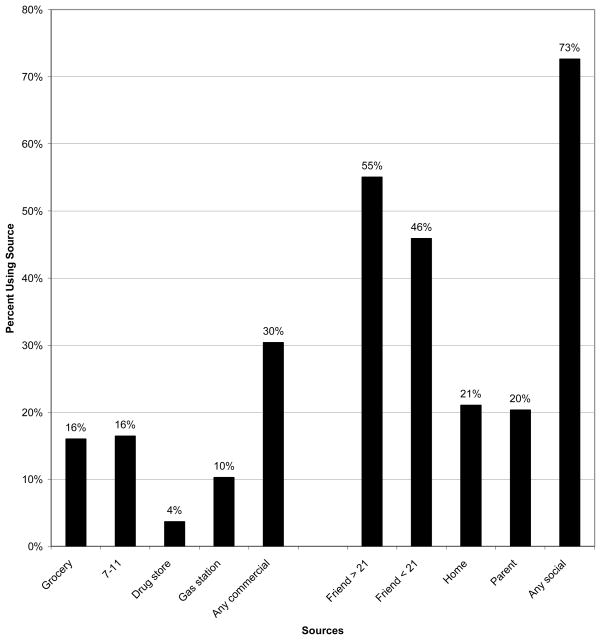

On a separate module, students reported where they obtained alcohol: “During the past 30 days, how many times did you get alcohol (beer, wine, or hard liquor) from each of the following sources…” The questionnaire included 8 possible sources, as indicated in Figure 1. These sources included both commercial and social sources. Students indicated their use of each source on an 8-point scale (none, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5–9, 10–14, 15 or more). For the purposes of analysis, a ‘commercial source’ variable was formed as the sum of grocery stores, convenience stores, drug stores, and gas stations.

Figure 1.

Source of alcohol among 30-day users (Oregon 2000–2002)

Community level indicators

As a community index of commercial alcohol availability, we calculated the percent of students in each community that reported using any of the four commercial sources above. As a community index of enforcement of minor in possession laws, we computed the mean in each community on the following item, “If a kid drank some beer, wine, or hard liquor in your neighborhood, would he or she be caught by the police?” The 4-point response scale was “NO!” “no,” “yes,” and “YES!”

Analysis

We used a multilevel modeling approach to examine the relationship of both individual-level and community-level access measures to youthful alcohol use. Conceptually, the model evaluates the effect of both individual level (Level 1) and community level (Level 2) variables by simultaneously estimating three combined regression equations. At level 1, an alcohol use variable, Yij, of individual student i residing in community j is predicted by the equation:

where values of β0j and β1j are allowed to vary across the j communities such that the intercept term β0j represents the mean level of alcohol use in each community; and the βlj represent the relative use in each community of the (l = 1 to 5) commercial or social source predictors, X1ji. The term rij is the level-1 random error term.

While the individual-level analysis estimates are of substantive interest in and of themselves, the extent to which there is variability of these estimates across communities, and the extent to which that variability can be explained as a function of the community level (Level 2) variables of commercial access rates and MIP enforcement is the primary analytical goal.

At Level 2, each community’s alcohol use mean (β0j) and source slopes (βlj) are modeled as a function of level-2 variables:

where γ00 is the average intercept (average level of alcohol use frequency) across communities, and the γl0 are the average slopes (average relative use) of each of the sources, βlj, across communities. Wj are level-2 predictors, in this case, the estimated youth commercial access rate and level of MIP enforcement in each community; γ0z represents the secular rise or fall in 11th grade alcohol use over the two measurement time points (years), and u0j and ulj are the level-2 random error terms. The term γ0w represents the direct or main effect of community-level access rates and MIP enforcement on mean levels of youth alcohol use. The terms γlw estimate the cross-level or interactional effects of community access rates and MIP enforcement and the use of each of the l = 1 to 5 examined sources of alcohol. That is, they estimate the degree to which the relative use of a source, as it relates to the frequency of alcohol use, varies as a function of rate of illegal sales or MIP enforcement in the community.

We performed computations using SAS Proc Mixed.32 Proc Mixed, which provides a general linear mixed model capability suitable for analyze outcomes with errors assumed to be normally distributed have also shown to work well for dependent variables that are non-normally distributed.33

To make the results more directly interpretable, we centered the Level-1 source predictor variables around the around the group (community) means. Group-mean centering compares each score relative to the mean for its particular group. For example, with group centering, a student’s use of a particular source is centered relative to the mean use of that source in their community. We also grand mean centered the outcomes and level-2 variables, and standardized them to unit variance. Year was effect coded (−1, 1). Sampling weights were used in all calculations.

Results

Sources of Alcohol

Figure 1 presents data on the percent of current drinkers who reported obtaining alcohol from each of eight sources, as well as for any commercial and any social source. Overall, commercial sources were used by 30% of current drinkers, while social sources were used by over 70%.

Tables 1–4 present the individual level coefficients predicting the relative use of sources to predict the alcohol-use frequency outcomes. These coefficients represent the average use of the sources across the population. The scale on these predictors was centered but left at number of days used. Because the alcohol outcome variables were standardized, coefficients represent standard deviation unit changes in the outcomes for each addition day a source was used, controlling for the use of other sources, and are directly comparable across sources and outcomes. Positive coefficients indicate increasing alcohol use with increased source use, whereas negative coefficients indicate that use of a source is associated with increasingly less alcohol use.

Table 1.

Results from multi-level modeling for 11th grade: frequency of alcohol use last 30 days

| Fixed effect | Coefficient | se | t Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model for Individuals (N = 3,318) | |||

| Commercial sources | 0.041 | 0.006 | 6.84** |

| Friends >21 source | 0.175 | 0.007 | 24.71** |

| Friends <21 source | 0.059 | 0.010 | 5.51** |

| Parent source | 0.075 | 0.016 | 4.49** |

| Stole from home source | −0.016 | 0.015 | −1.06 |

|

| |||

| Model for Communities (N=93) | |||

| Commercial access rate (CAR) | 0.054 | 0.025 | 2.15* |

| Minor in possession enforcement (MIP) | −0.040 | 0.021 | −1.96* |

|

| |||

| Cross-level effects | |||

| CAR → Commercial source | 0.013 | 0.006 | 1.96* |

| CAR → Friend > 21 source | −0.005 | 0.006 | −0.88 |

| CAR → Friend < 21 source | 0.026 | 0.010 | 2.46** |

| CAR → Parent source | 0.058 | 0.017 | 3.28** |

| CAR → Home source | 0.019 | 0.016 | 1.19 |

| MIP → Commercial source | −0.004 | 0.006 | −0.70 |

| MIP → Friend > 21 source | 0.011 | 0.007 | 1.38 |

| MIP → Friend < 21 source | −0.021 | 0.011 | −1.87+ |

| MIP → Parent source | −0.025 | 0.016 | −1.56 |

| MIP → Home source | 0.059 | 0.018 | 3.29** |

| Variance

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effect | Component | se | t-value |

| Community means, u0j | 0.033 | 0.009 | 3.62** |

| Commercial source slopes, u1j | 0.015 | 0.004 | 3.71** |

| Friends >21 source slopes, u2j | 0.008 | 0.002 | 3.47** |

| Friends <21 source slopes, u3j | 0.017 | 0.004 | 3.59** |

| Parent source slopes, u4j | 0.023 | 0.009 | 2.40** |

| Stole from home source slopes, u5j | 0.047 | 0.017 | 2.67** |

| Individual students, rij | 0.457 | 0.011 | 38.46** |

p<.10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 4.

Results from multi-level modeling 11th grade: frequency drinking & driving/riding last 30 days

| Fixed effect | Coefficient | se | t Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model for Individuals (N = 3,073) | |||

| Commercial sources | 0.056 | 0.006 | 8.81** |

| Friends >21 source | 0.129 | 0.008 | 14.63** |

| Friends <21 source | 0.100 | 0.013 | 7.40** |

| Parent source | −0.082 | 0.016 | −5.03** |

| Stole from home source | −0.005 | 0.015 | −0.34 |

|

| |||

| Model for Communities (N = 93) | |||

| Commercial access rate (CAR) | 0.078 | 0.024 | 3.19** |

| Minor in possession enforcement (MIP) | 0.032 | 0.021 | 1.49 |

|

| |||

| Cross-Level Effects | |||

| CAR → Commercial source | −0.027 | 0.006 | −4.06** |

| CAR → Friend > 21 source | 0.044 | 0.008 | 5.09** |

| CAR → Friend < 21 source | −0.084 | 0.013 | −6.50** |

| CAR → Parent source | 0.030 | 0.016 | 1.79+ |

| CAR → Home source | 0.057 | 0.016 | 3.47** |

| MIP → Commercial source | −0.036 | 0.005 | −6.22** |

| MIP → Friend > 21 source | 0.056 | 0.008 | 6.68** |

| MIP → Friend <21 source | −0.022 | 0.014 | −1.52 |

| MIP → Parent source | −0.041 | 0.018 | −2.25** |

| MIP → Home source | −0.017 | 0.016 | −1.10 |

| Variance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effect | Component | se | t-value |

| Community means, u0j | 0.028 | 0.008 | 3.26** |

| Commercial source slopes, u1j | 0.042 | 0.014 | 3.01** |

| Friends >21 source slopes, u2j | 0.013 | 0.004 | 3.21** |

| Friends <21 source slopes, u3j | 0.042 | 0.012 | 3.47** |

| Parent source slopes, u4j | 0.028 | 0.013 | 2.13* |

| Stole from home source slopes, u5j | 0.055 | 0.019 | 2.91** |

| Individual students, rij | 0.523 | 0.014 | 36.21** |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Provision of alcohol by friends over 21 was the largest contributor to frequency of alcohol use outcomes (range .129 to .187) for all but use at school, followed by provision of alcohol by friend under 21 (range .059 to .100). Parent sources contributed positively to general frequency of use (.075), but negatively to frequency of binge drinking (−.055) and driving/riding while drinking (−.082). Taking from home without permission was associated only with frequency of drinking at school (.113). Use of commercial sources independently contributed significantly and positively to each of the alcohol use outcomes examined (range .041 to .108). The estimates for variance components at the bottom of tables 1–4 indicate that the relationship of sources to outcomes varied significantly across communities.

Prediction of Community-Level Alcohol Use from Access and Enforcement

Higher rates of community level commercial access, as indexed by the number of students in the community that reported buying, was significantly and positively related to the mean levels of alcohol use and related problems in those communities (range .054 to .078). Stronger enforcement of minor in possession laws, as indexed by the students average perceived level of enforcement in the community, was significantly related to lower levels in the communities general frequency of use and binge drinking (−.040 and −.035, respectively), but not levels of drinking in school or drinking and driving/riding. Because the community level variables are standardized, coefficients indicate standard deviation changes in outcomes for each standard deviation increase in the community level predictors and are directly comparable across outcomes and to each other (but not to the individual level coefficients). We also tested the interaction between the two community levels variables, i.e., whether increase MIP enforcement in combination with higher or lower commercial access had a differential impact than expected from each additively, and found none to be significant.

Impact of Community-Level Access and Enforcement on Source Use

Levels of commercial access interacted with the individuals use of sources such that communities with overall higher commercial access had more frequent use of those sources regarding general alcohol use and binge drinking (.013 and .021), and less frequent use of those sources in relation to alcohol use in school and when drinking and driving/riding (−.043 and −.027, respectively). Regarding the impact on friends as a social source, communities with higher levels of commercial access has slightly less dependence on sources over 21 (−.016) for binge drinking but more dependence on that source while drinking and driving/riding (.044); and more use of sources under 21 for binge drinking (.030) and in general (.026) but less use of those under 21 while driving (−.084). Communities with higher commercial access also had higher provision of alcohol by parents for all outcomes but drinking and driving (.058 to .088); and taking from home without permission was used more often in high access communities for use in school (.036) or drinking and driving (.057).

Community level enforcement of minor in possession laws was a deterrent for individual’s use of commercial sources to drink in school (−.019) or to drink and drive (−.036). It also deterred the use of friends under 21 for binge drinking (−.033) and use in general (−.021) and the use of parent sources for drinking and driving (−.041). On the other hand, communities with higher MIP enforcement also tended to have more reliance on taking from home without permission for binge drinking (.0303) and use in general (.059), and for more frequent use of friends over 21 as a source while driving (.056).

Discussion

Of primary substantive interest in this analysis was the relationship of the community level variables of access and enforcement on the communities mean level of alcohol use and related problems. Using a relatively large number of communities (N = 93), the results above provide evidence for the direct impact of these community level predictors on a range of youth alcohol related outcomes. This evidence provides much needed empirical support for the potential utility of local efforts to invest in increasing access control and possession enforcement as recommend by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention “Best Practices.” 25

Regarding commercial access, the results indicated a consistent pattern on both the independent use of those sources by individual adolescents and the association between levels of youth access and alcohol problems in the community. The independent contribution of commercial sources to the general frequency of drinking is troubling, but the evidence for use of these sources for excessive (binge) drinking and drinking in very inappropriate contexts (school and driving) at the individual and local community level raises the level of concern. Increased efforts to reduce youth commercial access to alcohol, including merchant education and surveillance programs, may well serve local public health and law enforcement officials.

Community levels of commercial access also were seen to modify (interact with) the frequency of use of social sources of alcohol in a somewhat complex fashion. This may occur because, as access to one source (commercial) becomes more difficult, resourceful adolescents modify their alcohol seeking behavior to compensate and/or may simply use a larger number of alternative sources. For example, we found that for general alcohol use and binge drinking frequency those communities with higher access rates also had adolescents who used friends under 21 and parent sources more often, in addition to the increased use of commercial sources. The increased use of friends under 21 certainly could be the indirect result of more of youth suppliers who themselves obtained the alcohol from commercial sources. The increased reliance on parent sources however, may reflect a community wide tolerance for adolescent drinking, as evidenced by both commercial availability and adult provision of alcohol. A similar explanation may underlie the finding of increased use of parent sources for use in school, and the provision of alcohol by adults (friends over 21) while drinking and driving or riding in communities with higher commercial access rates.

Regarding enforcement of minor in possession laws, we found that communities with increased levels of enforcement tended to have lower community levels of binge drinking and drinking in general. These effects are consistent with the notion that perceived negative consequences (being caught by the police), if broad and severe enough, could be a deterrent to behavior. The effect on in-school drinking and on drinking and driving/riding was not reliable. The lack of associations on those outcomes may have been due to the literal interpretation of the item, which referred to being caught if used in the neighborhood. Youth may have interpreted that not to mean while at school or in a car. Alternatively, community-level police enforcement may simply be unassociated with, or perceived as highly unlikely, in these alcohol use contexts.

Enforcement interacted with source usage. Use of sources under the age of 21 for binge drinking and general alcohol use was curtailed in communities with high enforcement, as could be expected when possession by those under 21 is restricted. Use of commercial sources was also curtailed in communities with high MIP enforcement for in school and drinking while driving. In the case of in-school use, this interaction brings the impact of MIP enforcement to a significant level overall (−.042), in communities with high access. However, in the case of drinking and driving, the overall effect of MIP enforcement is still near zero (−.004) in communities with high access. Higher MIP enforcement in the community does appear to increase the use of taking from home without permission for binge and general drinking, perhaps because youth simply drink at home if they feel they would be caught outside the home. The negative interaction between use of parent sources (with or without permission) for drinking and driving does appear to be reduced in stricter MIP enforced communities below already infrequent overall levels, perhaps because of the wider message it sends parents regarding the unacceptability of provision of alcohol to their children, especially if they are going to be involved with vehicles. The same does not appear to be true for friends over 21 however, as evidenced by the positive interaction term for that effect.

Limitations

First, our data are epidemiological in nature, being observations of natural occurring variations in individuals and communities, and as such, our conclusions are limited to observed associations at levels of the examined variables. Experimental manipulation of community access and enforcement is needed to draw casual inference on the relationship between access, enforcement, and levels of youthful alcohol use. However, the consistency of associations across a large number of communities and outcomes strengthens our confidence in these findings. Second, we use somewhat non-traditional measures of community level access and enforcement. It is certainly possible that different associations and conclusions would be drawn from access measures such as alcohol outlet density, minor decoy purchase survey rates, or enforcement measures such as number of officers assigned or citations issued, etc. We feel our community level measures do have meaningful direct interpretation, and at least index the level of youth access and MIP enforcement in a community. Finally, our results are limited to a narrow age range (16–17 year old) of in-school youth, of fairly homogeneous ethnic makeup (85% White) in a sample of largely rural northwestern communities. The impact of access and enforcement in other youth populations may vary as a function of age and region. Again however, the large number of communities examined, and the manner in which they were chosen, provides confidence that similar results would be obtained in similarly composed communities elsewhere.

Table 2.

Results from multi-level modeling for 11th grade: frequency binge drinking last 30 days

| Fixed effect | Coefficient | se | t Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model for Individuals (N=3,318) | |||

| Commercial sources | 0.061 | 0.005 | 10.52** |

| Friends >21 source | 0.187 | 0.006 | 27.53** |

| Friends <21 source | 0.070 | 0.010 | 6.90** |

| Parent source | −0.055 | 0.016 | −3.42** |

| Stole from home source | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.69 |

|

| |||

| Model for Communities (N=93) | |||

| Commercial access rate (CAR) | 0.060 | 0.024 | 2.46** |

| Minor in possession enforcement (MIP) | −0.035 | 0.020 | −1.68+ |

|

| |||

| Cross-Level Effects | |||

| CAR → commercial source | 0.021 | 0.006 | 3.43** |

| CAR → Friend > 21 source | −0.016 | 0.006 | −2.59** |

| CAR → Friend < 21 source | 0.030 | 0.010 | 2.97** |

| CAR → Parent source | 0.088 | 0.017 | 5.21** |

| CAR → Home source | −0.000 | 0.015 | −0.00 |

| MIP → Commercial source | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.18 |

| MIP → Friend > 21 source | −0.002 | 0.007 | −0.37 |

| MIP → Friend <21 source | −0.033 | 0.011 | −3.05** |

| MIP → Parent source | 0.020 | 0.015 | 1.34 |

| MIP → Home source | 0.030 | 0.017 | 1.80+ |

| Variance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effect | Component | se | t-value |

| Community means, u0j | 0.033 | 0.008 | 3.80** |

| Commercial source slopes, u1j | 0.023 | 0.006 | 3.89** |

| Friends >21 source slopes, u2j | 0.009 | 0.002 | 3.50** |

| Friends <21 source slopes, u3j | 0.024 | 0.006 | 3.78** |

| Parent source slopes, u4j | 0.026 | 0.011 | 2.40** |

| Stole from home source slopes, u5j | 0.081 | 0.024 | 3.31** |

| Individual students, rij | 0.392 | 0.010 | 38.06** |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Table 3.

Results from multi-level modeling 11th grade: frequency drinking at school last 30 days

| Fixed effect | Coefficient | se | t Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model for Individuals (N = 3,318) | |||

|

| |||

| Commercial sources | 0.108 | 0.007 | 13.70** |

| Friends >21 source | 0.012 | 0.009 | 1.34 |

| Friends <21 source | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.32 |

| Parent source | 0.018 | 0.022 | 0.82 |

| Stole from home source | 0.113 | 0.020 | 5.46** |

|

| |||

| Model for Communities (N=93) | |||

| Commercial access rate (CAR) | 0.058 | 0.025 | 2.28** |

| Minor in possession enforcement (MIP) | −0.023 | 0.022 | −1.05 |

|

| |||

| Cross-Level Effects | |||

| CAR → Commercial source | −0.043 | 0.008 | −5.03** |

| CAR → Friend > 21 source | 0.009 | 0.008 | 1.12 |

| CAR → Friend < 21 source | −0.000 | 0.014 | −0.06 |

| CAR → Parent source | 0.059 | 0.023 | 2.53** |

| CAR → Home source | 0.036 | 0.021 | 1.74+ |

| MIP → Commercial source | −0.019 | 0.008 | −2.29** |

| MIP → Friend > 21 source | −0.049 | 0.010 | −4.83** |

| MIP → Friend <21 source | 0.021 | 0.015 | 1.45 |

| MIP → Parent source | −0.021 | 0.021 | −1.00 |

| MIP → Home source | −0.021 | 0.023 | −0.94 |

| Variance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effect | Component | se | t-value |

| Community means, u0j | 0.010 | 0.005 | 1.89* |

| Commercial source slopes, u1j | 0.014 | 0.004 | 3.06** |

| Friends >21 source slopes, u2j | 0.031 | 0.006 | 4.74** |

| Friends <21 source slopes, u3j | 0.015 | 0.005 | 2.63** |

| Parent source slopes, u4j | 0.030 | 0.015 | 1.95* |

| Stole from home source slopes, u5j | 0.086 | 0.033 | 2.55** |

| Individual students, rij | 0.725 | 0.018 | 38.65** |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Acknowledgments

National Cancer Institute Grant CA 86169, Contract #103446 with the State of Oregon Department of Human Services, and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA 06282 supported the work of the authors during preparation of this paper.

References

- 1.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. NIH Pub No 03-5374. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2002. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2002. Available online at: http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/overview2002.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT. Alcohol misuse and adolescent sexual behaviors and risk taking. Pediatrics. 1996;98:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Alcohol misuse and juvenile offending in adolescence. Addiction. 1996;91:483–494. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9144834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy DT, Miller TR, Cox KC. Costs of underage drinking. Calverton, MD: OJJDP Center for Enforcing Underage Drinking Laws; 1999. Available online at: http://www.udetc.org/documents/costunderagedrinking.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wechsler H, Molnar BE, Davenport AE, Baer JS. College alcohol use: A full or empty glass? Journal of American College Health. 1999;47:247–252. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Park E. Relative importance of social versus commercial sources in youth access to tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:39–48. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preusser DF, Williams AF. Sales of alcohol to underage purchasers in three New York counties and Washington DC. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1992;13:306–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz RH, Farrow JA, Banks B, Giesel AE. Use of false ID cards and other deceptive methods to purchase alcoholic beverages during high school. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1998;17:25–34. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagenaar AC, Toomey TL, Murray DM, Short BJ, Wolfson M, Jones-Webb R. Sources of alcohol for underage drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:325–333. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forster JL, McGovern PG, Wagenaar AC, Wolfson M, Perry CL, Anstine PS. The ability of young people to purchase alcohol without age identification in northeastern Minnesota, USA. Addiction. 1994;89:699–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster JL, Murray DM, Wolfson M, Wagenaar AC. Commercial availability of alcohol to young people: Results of alcohol purchase attempts. Preventive Medicine. 1995;24:342–347. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grube JW. Preventing sales of alcohol to minors: Results from a community trial. Addiction. 1997;92(Suppl 2):S251–S260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones-Webb R, Toomey TL, Short B, Murray DM, Wagenaar A, Wolfson M. Relationships among alcohol availability, drinking location, alcohol consumption and drinking problems in adolescents. Substance Use Misuse. 1997;32:1261–1285. doi: 10.3109/10826089709039378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagenaar AC, Finnegan JR, Wolfson M, Anstine PS, Williams CL, Perry CL. Where and how adolescents obtain alcoholic beverages. Public Health Reports. 1993;108:459–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sussman S. Curriculum development in school-based prevention research. Health Education Research: Theory and Practice. 1991;6:339–351. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen WB. Prevention of alcohol use and abuse. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:683–687. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foxcroft DR. Adolescent alcohol use and misuse in the UK. Educational and Child Psychology. 1996;13(1):60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foxcroft DR, Lister-Sharp D, Lowe G. Alcohol misuse prevention for young people: A systematic review reveals methodological concerns and lack of reliable evidence of effectiveness. Addiction. 1997;92:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giesbrecht N, Grube JW. Information, education, and persuasion as strategies for reducing or preventing drinking-related problems. In: Babor T, editor. Alcohol: No ordinary commodity. Research and Public Policy. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paglia A, Room R. Preventing substance use problems among youth: A literature review and recommendations. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1999;20:3–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grube JW, Nygaard P. Overview of effective interventions for young people. In: Stockwell T, Gruenewald PJ, Toumbourou J, Loxley W, editors. Working upstream: Drugs, science and prevention policy. New York: Wiley; (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toomey TL, Wagenaar AC. Policy options for prevention: The case of alcohol. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1999;20:193–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagenaar AC, Murray DM, Gehan JP, Wolfson M, Forster JL, et al. Communities mobilizing for change on alcohol: Outcomes from a randomized community trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:85–94. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention. Regulatory strategies for reducing youth access to alcohol: best practices. Calverton, MD: Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention, Center for Enforcing Underage Drinking Laws; 1999. Available online at: http://www.udetc.org/documents/accesslaws.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbey A, Scott RO, Smith MJ. Physical, subjective, and social availability: Their relationship to alcohol consumption in rural and urban areas. Addiction. 1993;88:489–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treno AJ, Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW. Alcohol availability and injury: The role of local outlet densities. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1467–1471. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruenewald PJ, Millar AB, Treno AJ, Yang Z, Ponicki WR, Roeper P. Geography of availability and driving after drinking. Addiction. 1996;91:967–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9179674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freisthler B, Gruenewald PJ, Treno AJ, Lee J. Evaluating alcohol access and the alcohol environment in neighborhood areas. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:477–84. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057043.04199.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Treno AJ, Grube JW, Martin S. Alcohol outlet density as a predictor of youth drinking and driving: A hierarchical analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:835–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000067979.85714.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2000;49(SS-5):1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SAS Version 9.0, User Manual. Cary, NC: [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannan PJ, Murray DM. Gauss or Bernoulli? A Monte Carlo comparison of the performance of the linear mixed-model and the logistic mixed-model analyses in simulated community trials with a dichotomous outcome variable at the individual level. Evaluation Review. 1996;20(3):338–352. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9602000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]