Abstract

NKX3.1 allelic loss and MYC amplification are common events during prostate cancer progression and have been recognized as potential prognostic factors in prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy or precision radiotherapy. We have developed a 4FISH-IF assay (a dual-gene fluorescence in situ hybridization combined with immunofluorescence) to measure both NKX3.1 and MYC status on the same slide. The 4FISH-IF assay contains four probes complementary to chromosome 8 centromere, 8p telomere, 8p21, and 8q24, as well as an antibody targeting the basal cell marker p63 visualized by immunofluorescence. The major advantages of the 4FISH-IF include the distinction between benign and malignant glands directly on the 4FISH-IF slide and the control of truncation artifact. Importantly, this specialized and innovative combined multiprobe and immunofluorescence technique can be performed on diagnostic biopsy specimens, increasing its clinical relevance. Moreover, the assay can be easily performed in a standard clinical molecular pathology laboratory. Globally, the use of 4FISH-IF decreases analytic time, increases confidence in obtained results, and maintains the tissue morphology of the diagnostic specimen.

Keywords: biopsy, fluorescence in situ hybridization, immunofluorescence, MYC, NKX3.1, prostate cancer

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common cancer in Canadian men (National Cancer Institute of Canada 2011). As the 5-year relative survival associated with localized PCa is more than 90% (Damber and Aus 2008; Jemal et al. 2009; National Cancer Institute of Canada 2011), many efforts are directed at decreasing the human and financial burden of unnecessary radical treatments. In addition, patients may have great clinical heterogeneity despite similar clinical prognostic factors (e.g., prostate-specific antigen [PSA], Gleason score and stage). Therefore, genetic factors could help place patients into prognostic subgroups and drive novel therapies.

Monoallelic deletion of NKX3.1 has been associated with PCa progression, whereas the gene would be required for prostatic stem cell maintenance (Bowen et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2009). Recently, NKX3.1 has been implicated in DNA damage response through interactions with topoisomerase I and by facilitating recruitment of phosphorylated ATM and γH2AX to sites of DNA double-strand break damage (Bowen et al. 2007; Bowen and Gelmann 2010). NKX3.1 allelic loss has been associated with increased genomic instability that is independent of PSA, T stage, and Gleason score (Bowen et al. 2000; Asatiani et al. 2005; Kindich et al. 2005; Bethel et al. 2006; Locke et al. 2012). Using array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) on biopsy specimens from men with intermediate-risk PCa treated by radiation therapy, we previously showed that NKX3.1 allelic loss was also associated with early biochemical recurrence in men treated by precision radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy (Locke et al. 2012).

Amplification at 8q24, harboring the MYC oncogene, is one of the most common chromosomal abnormalities in PCa progression. MYC regulates a myriad of genes controlling cell proliferation, metabolism, differentiation, and apoptosis (Gurel et al. 2008). Several groups correlated 8q gain, MYC gain, and MYC messenger RNA levels with aggressive disease, early disease progression, and early cancer death (van Duin et al. 2005; Sato et al. 2006; Lapointe et al. 2007; Ishkanian et al. 2009; Ishkanian et al. 2010; Locke et al. 2012; Zafarana et al. 2012).

Importantly, preclinical models have supported a unique cooperation between MYC overexpression and NKX3.1 allelic loss in driving prostate cancer progression and aggression (Kim et al. 2007; Iwata et al. 2010; Anderson et al. 2012). We also demonstrated that such interplay was of clinical significance, as in our aCGH cohort, the presence of NKX3.1 allelic loss in combination with MYC amplification was associated with earlier biochemical recurrence than either allelic change alone (Locke et al. 2012).

We therefore expect that the assessment of both MYC gain and NKX3.1 deletion would be very relevant to clinical care of men with PCa by identifying patients with more aggressive disease. To be used in routine clinical care, detection of these alterations has to be easily achieved in a standard molecular pathology laboratory. For these reasons, we decided to develop a high-efficiency fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technique to detect both NKX3.1 loss and MYC amplification in diagnostic samples such as needle biopsies. As FISH can be performed on slides from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, it is a very useful adjunct to histopathological diagnosis. Further interest for the development of the technique comes from its in situ nature that allows for specific analysis of the cells of interest. This is especially true in PCa, with its characteristic intermingling of benign and malignant glands. On the other hand, truncation artifact, associated complexity in positive threshold determination, and difficult histological interpretation of the usual 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) counterstain may limit reliable FISH interpretation.

Briefly, our 4FISH-IF (a dual-gene FISH combined with immunofluorescence assay) contains four FISH probes, two being used as controls (complementary to chromosome 8 centromere and 8p telomere) and two targeting NKX3.1 (8p21) and MYC (8q24), as well as an antibody targeting the basal cell marker p63 visualized by immunofluorescence (IF). This combination addresses most drawbacks associated with the use of FISH in PCa FFPE specimens. As such, this simple yet efficient combination makes the 4FISH-IF a very powerful technique that can be performed in a standard molecular pathology laboratory on clinical diagnostic biopsy specimens.

Materials and Methods

Probes Selection, Testing, and Optimization

Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) corresponding to 8p telomere and 8p21 were identified using the UCSC Genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and ordered from the BACPAC Resources Center (Oakland, CA). Chromosome 8 centromere (CEP8) was visualized using a commercial probe (Vysis CEP 8 SpectrumAqua Probe, 06J54-018; Abbott Molecular, Markham, Canada). The 8p telomere and CEP8 were selected according to the smallest region of deletion as observed in our aCGH cohort (Locke et al. 2012). The 8p21 BAC (NKX3.1) covered the region that was deleted in the tumors with an allelic loss. The flanking 8p telomere BAC and CEP8 covered regions that were intact in the vast majority of tumors with 8p21 allelic loss. Both the CEP8 and the 8p telomere were the references for 8p21 deletion (flanking gene approach) (Sircar et al. 2009). The MYC (8q24) gene was visualized using a commercial probe (Vysis LSI MYC SpectrumGold probe, 04N35-020; Abbott Molecular).

Selected BACs were labeled with green (02N32-050; Abbott Molecular) and red (02N34-050; Abbott Molecular) dUTPs using the nick translation kit (07J00-001; Abbott Molecular) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The optimal labeling conditions for each BAC were determined by testing the length of the labeled probes on agarose gels. After nick translation and before ethanol precipitation, 10 µg of human COT-1 DNA (06J31-001, 1 µg/µl; Abbott Molecular) was added to each microgram of labeled BAC. Precipitated DNA was resuspended in hybridization buffer (06J67-001; Abbott Molecular) diluted in deionized water (7:10) to a final concentration of 1:10 (w/v).

To determine the specificity of our BAC probes, we hybridized them to a chromosome spread obtained from the peripheral blood lymphocytes collected from a healthy man. The sensitivity of our assay was determined by hybridization of the BAC probes to interphase blood lymphocytes collected from five healthy donors (5-pooled blood). For both specificity and sensitivity assays, the sample slides were processed as follows. Slides were incubated in the oven at 60C for 1 hr, then incubated in 2× saline-sodium citrate (SSC) at 37C for 30 min and finally dehydrated in graded alcohols. Following dehydration, 2.5 µl of a probe mix (each probe, 50 ng; human COT-1 DNA, 2 µg; hybridization buffer, 6 µl; deionized water, 1 µl) was co-denatured in a Thermobrite apparatus (Abbott Molecular) at 75C for 1 min. The hybridization was carried out overnight at 37C. Slides were then washed in 0.4× SSC/0.3% IGEPAL at 72C for 2 min and in 2× SSC/0.1% IGEPAL at room temperature for 30 sec, air dried, counterstained with DAPI, and mounted in an aqueous mounting medium (H-1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlington, Canada). Two independent readers (DT, CLH) verified the position of the signals in five metaphases on the chromosome spread and counted the number of signals in 250 interphase cells on the 5-pooled blood.

FISH Procedure

The FISH protocol was optimized for FFPE sections of clinical samples. After deparaffinization in xylene, pretreatment (see below), and dehydration in graded alcohols, the sample slides were co-denatured with the probe mix in the Thermobrite apparatus at 75C for 10 min. The hybridization was carried out for 18 hr at 37C. The slides were then washed in 0.4× SSC/0.3% IGEPAL at 69C for 2 min and in 2× SSC/0.1% IGEPAL at room temperature for 1 min.

Immunofluorescence Procedure Testing and Optimization

Immunofluorescence was performed using an antibody targeting p63, a marker of the basal cells lining the non-malignant glands in prostatic tissue. With this antibody, it is possible to easily and reliably exclude benign glands from the FISH analysis.

The IF protocol was optimized for FFPE sections of clinical samples. All incubations were performed at room temperature and all reagents were rinsed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline when incubation time was over. Deparaffinization in xylene was followed by rehydration in graded alcohols and blocking with normal horse serum (S-2000, 1/10 dilution in 0.05 M Tris-buffered saline [TBS] [pH 7.4–7.6] with 0.5% casein, 0.05% thimerosal, 2.5:1000 Tween-80, and 2.25:1000 Triton X-100 [antibody diluting buffer, ADB]; Vector Laboratories) for 10 min. The slides were then incubated with the p63 antibody (clone 4A4, SC-8431, 1/200 to 1/100 dilutions in ADB with 3% bovine serum albumin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 to 2 hr. Slides were finally incubated with a secondary antibody labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (A-11029, 1/100 dilution in ADB; Life Technologies, Burlington, Canada) for 1 hr.

Alternatively, an alkaline phosphatase system was used to reveal the antibody-antigen reaction. All incubations were performed at room temperature, and all reagents were rinsed with 1× TBS when incubation time was over. After serum blocking, the slides were incubated with the p63 antibody (1/1000 to 1/100 dilutions in ADB with 3% bovine serum albumin) for 30 min to 1 hr. The slides were further incubated with a biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG antibody (BA-2001, 1/100 dilution in ADB; Vector Laboratories) for 30 min, followed by an incubation with streptavidin, alkaline phosphatase conjugated (SA-5100, 1/100 dilution in ABD; Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Vector Red alkaline phosphatase substrate (SK-5100, prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 0.1% Triton-X, with or without levamisole solution [SP-5000]; Vector Laboratories) was finally added to the slides for 5 to 15 min.

Test Chronology and Pretreatment Conditions, Testing, and Optimization

Regular pretreatment conditions for immunohistochemistry and FISH were tested with both FISH and IF (Table 1) to identify the best condition(s) for both techniques. After submitting the slides to the optimal pretreatment, FISH was performed either after or before IF, following the protocols as described above. When FISH was performed after Alexa Fluor 488–revealed IF, slides were also incubated in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at room temperature for 0 to 30 min and in deionized water at room temperature for 10 min between IF and FISH (Krenacs et al. 2010). Slides were then dehydrated in graded ethanols and submitted to FISH.

Table 1.

Individual Pretreatment Conditions.

| Condition No. | Reagent/Condition | Temperature, C | Time, min |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aging (dry oven) | 60 | Overnight |

| 2 | Sodium citrate 10 nM (pH 6.0) | 120 → 90 → room temperature | 10 → 5 → cool down |

| 3 | Sodium citrate 10 mM (pH 6.0) | 80 | 45 |

| 4 | 0.01N HCl | 37 | 2 |

| 5 | Pepsin 75,000 U/mL in 0.01N HCl, 1:100 | 37 | 5–10 |

| A | Deionized water | Room temperature | 10 |

All slides were counterstained with DAPI and mounted in aqueous mounting medium (H-1000; Vector Laboratories).

4FISH-IF Final Conditions

Paraffin sections were incubated in the oven at 60C overnight, deparaffinized in xylene, and hydrated in graded alcohols. Slides were incubated in sodium citrate 10 mM (pH 6.0) at 120C for 10 min, then at 90C for 5 min. Slides were cooled down in deionized water. IF was performed at room temperature, and all reagents were rinsed with 1× TBS when incubation time was over. Briefly, the slides were consecutively incubated with normal horse serum (S-2000, 1/10 dilution in ABD [0.05 M TBS] [pH 7.4–7.6] with 0.5% casein, 0.05% thimerosal, 2.5:1000 Tween-80, and 2.25:1000 Triton X-100; Vector Laboratories) for 10 min, with the p63 antibody (clone 4A4, SC-8431, 1/1000 dilution in ABD with 3% bovine serum albumin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 min, with the biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG antibody (BA-2001, 1/100 dilution in ADB; Vector Laboratories) for 30 min, and with the streptavidin, alkaline phosphatase conjugated (SA-5100, 1/100 dilution in ABD; Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. The Vector Red alkaline phosphatase substrate (SK-5100, prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions with 0.1% Triton-X; Vector Laboratories) was then added to the slides for 10 min. The slides were incubated in 1× TBS for 5 min, then immediately incubated in 0.01 N HCl 37C for 2 min and in pepsin (P7012-1G, 75,000 U/ml, 1/100 dilution in 0.01 N HCl; Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Canada) at 37C for 15 min. Pepsin was inactivated by incubating the slides in deionized water at room temperature for 5 min. The slides were further quickly dehydrated in graded alcohols. In a Thermobrite apparatus (Abbott Molecular), samples were co-denatured with the probe mix (each probe, 50 ng; human COT-1 DNA, 2 µg; hybridization buffer, 6 µl; deionized water, 1 µl) at 75C for 10 min. The hybridization was carried at 37C for 18 hr. Slides were washed in 0.4× SSC/0.3% IGEPAL at 69C for 2 min and in 2× SSC/0.1% IGEPAL at room temperature for 1 min. The slides were counterstained with DAPI and mounted in aqueous mounting medium (H-1000; Vector Laboratories).

Normal Thresholds Determination

Ten non-neoplastic areas were selected from pT3 PCa cases and embedded in a tissue microarray (TMA). 4FISH-IF was performed on two different sections of the TMA as a technical replicate, and five cases were evaluated on each section as a biological replicate. Assessed cells were from glands with p63-positive basal cells but were themselves negative for p63 (luminal cells). They had non-overlapping nuclei with at least two 8p telomere and two chromosome 8 signals (4 control signals). Proportions of cells with less than two copies of NKX3.1 and more than two copies of MYC in the normal cells were calculated and the 99% confidence intervals for NKX3.1, and MYC proportions were calculated using the exact binomial method. A wider confidence interval was chosen to guard against a high false-positive rate due to the cell truncation artifact secondary to the use of FFPE sections. Normal thresholds were defined as the upper limit of the confidence intervals as calculated using cases from both sections of the TMA. To compare cases from both sections of the TMA, we calculated the proportion of cases with less than two copies of NKX3.1 and the proportion of cases with more than two copies of MYC for each patient and then used a two-sided independent Mann-Whitney test to compare whether the average proportion among the first section was significantly different from that in the second section. A two-sided p value of less than 0.05 was used to assess statistical significance.

Patients

Patients were identified from the laboratory information system (Copath) of the University Health Network, Toronto, Canada. We selected five consecutive patients who were diagnosed with bilateral intermediate-risk prostate cancer (according to D’Amico et al. 2001) and treated by radical prostatectomy in our institution between March 2011 and 2012. Cores with cancer from left and right sides were selected for each patient (two blocks/patient). To corroborate the clonality of tumors (Barry et al. 2007), selected blocks were stained with ERG antibody as previously described (Kron et al. 2012). The global extent of tumor involvement and Gleason scores were obtained from the pathology report.

Scoring

In each tumor focus, we aimed to assess 60 cells. Assessed cells were from glands without p63-positive basal cells and had non-overlapping nuclei with at least two 8p telomere and two chromosome 8 signals (4 control signals). The average number of chromosome 8, 8p21 (NKX3.1), and 8q24 (MYC) was counted for each scored focus.

Results

Probes

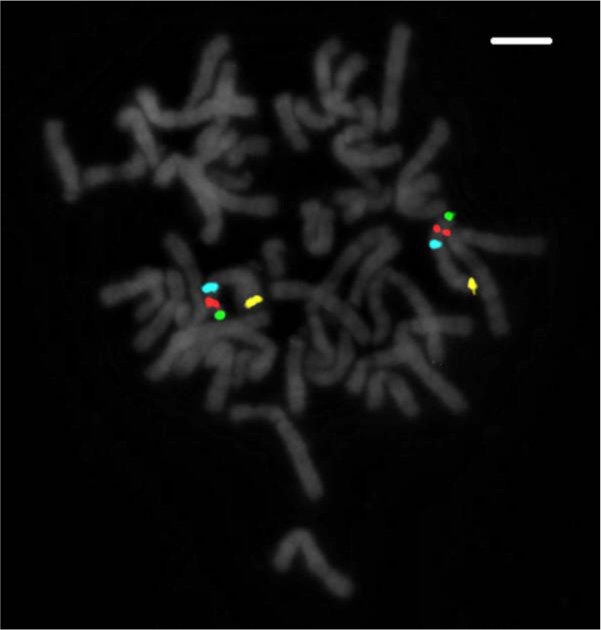

Optimal labeled probe size was of approximately 450 kb (data not shown). A specific BAC or commercial probe was found for each of the target loci of chromosome 8 (8p telomere, centromere, 8q24, and 8p21) (Fig. 1). A mean (SD) of 1.96 to 1.99 (0.17–0.24) signals/BAC/cell were counted on the 5-pooled blood slide.

Figure 1.

Metaphase spread showing 8p telomere (green), 8p21 (red), 8p centromere (aqua), and 8q24 (gold) in chromosome 8. Scale bar: 3 µm.

FISH, Immunofluorescence, and Pretreatment Conditions Testing and Optimization

Table 2 summarizes the obtained FISH and IF results with the different pretreatment conditions. The only condition that led to signals from both IF and FISH was overnight incubation of the slides at 60C, followed by deparaffinization and incubation in sodium citrate 10 mM (pH 6.0) at 120C for 10 min and then at 90C for 5 min. These conditions were further used in the testing of combined FISH and IF.

Table 2.

Tested Pretreatment Conditions and Associated Results for Independent Methods.

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Used, Condition No. from Table 1a | Immunofluorescence Result | Nuclei | % of Cells with Expected Signalsb |

| 1, 3, A, 4, 5, A | No staining | Appropriate digestion | >95 |

| 1, 2, A, 4, 5, A | No staining | Appropriate digestion | >95 |

| 2 | Excellent | Underdigested | <10 |

| 1, 2 | Good | Underdigested | >90 |

Performed in the described sequence.

Most benign cells harboring two copies of each probe and most cancer cells harboring two copies of each control probes (8 telomere, CEP8).

Table 3 shows a summary of the tested conditions. We first determined if FISH should be performed before or after IF. FISH followed by IF led to good FISH signals but no IF signals. When Alexa Fluor 488-revealed IF was performed before FISH, observed IF and FISH signals were strong. In those conditions, however, cells were underdigested and led to a low level of adequate cells for FISH evaluation. Treating the cells with pepsin between IF and FISH led to good FISH signals in nuclei with appropriate digestion but clearly decreased IF signals. Incubation in 10% neutral buffered formalin before the pepsin treatment only slightly increased the quality of IF signals and did not modify the quality of FISH signals. Despite being feasible, this combination (Alexa Fluor 488–IF, formalin incubation, pepsin treatment, FISH) was not believed to be clinically applicable.

Table 3.

Summary of the Different Conditions Tested.

| Conditions | IF | FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Test chronology | ||

| FISH, IF | No signal | Signals |

| Alexa Fluor 488–revealed IF, FISH | Signals, quick quenching | Signals, underdigestion |

| Alexa Fluor 488–revealed IF, formalin incubation, FISH | Signals, acceptable quenching | Signals, underdigestion |

| Alkaline phosphatase–revealed IF, FISH | Signals, high background depending on IF conditions | Signals, gold and red probes similar to IF background when present |

| IF conditions | ||

| Alexa Fluor 488 revelation, primary antibody 1/100 to 1/200, incubation 1 hr | Higher signals with 1/200 | NA |

| Alkaline phosphatase revelation, primary antibody 1/100 to 1/1000, incubation 1 hr | Background decreases with increasing dilutions | NA |

| Alkaline phosphatase revelation, primary antibody incubation 30 min to 1 hr | Background decreases with decreased incubation time | NA |

| Alkaline phosphatase revelation with levamisole added to the substrate | No change in the background | NA |

| Combined conditions | ||

| Immunofluorescence, 0.01N HCl 37C × 2 min, pepsin 75,000 U/ml in 0.01N HCl (1:100) 37C × 5–15 min, and ddH2O room temperature × 5 min before FISH | Alexa Fluor 488–revealed IF: signal loss | Adequate digestion and signals |

| Alkaline phosphatase–revealed IF: intact signals | ||

FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IF, immunofluorescence; NA, not applicable.

To address the variable IF signals, we used an alkaline phosphatase method to reveal the antibody-antigen reaction (Speel et al. 1992; Speel et al. 1994). When performed before pepsin treatment and FISH, adequate IF signals were obtained but with high background levels. Addition of levamisole to the alkaline phosphatase substrate did not modify the background level. Different antibody concentrations, incubation times, and revelation times were tested to optimize the staining. Of note, in the cases with high background, incubation of the slides in 100% ethanol at room temperature for about 5 min decreased the background level without affecting the readability of the 4FISH-IF signals. This incubation step, when performed, has to be adjusted to the background level because the IF signals will eventually decrease to a low intensity, preventing its interpretation.

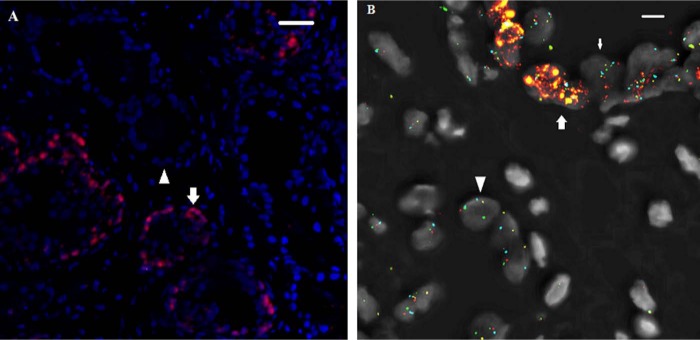

4FISH-IF

The optimized 4FISH-IF conditions led to stable IF and FISH signals with good reproducibility. As such, p63-positive basal cells were clearly identifiable both at low and high power, making the identification of tumor foci easier (Fig. 2). Benign basal cells were used as internal controls for p63 staining. The IF was visible both in the gold and in the Texas Red filter sets, with signals being large, granular, and highly resistant to bleaching. The evaluation of FISH signals in malignant cells was not affected by the presence of the IF signals in the benign glands. When nuclear digestion was not optimal, further treatment in 0.01 N HCl 37C for 2 min and then in pepsin (75,000 U/ml, 1/100 dilution in 0.01 N HCl) at 37C for 1 to 3 min before rehybridization did not impair IF signals.

Figure 2.

(A) A biopsy specimen showing the p63-positive basal cells (arrow) surrounding the benign glands and the p63-negative cancer focus (arrowhead). Texas Red and DAPI channels are shown after thresholds adjustments. Scale bar: 30 µm. (B) p63-positive basal cells (now showing the addition of red and gold due to the fluorescence in both channels, thick arrow) surrounding benign luminal cells with two signals of each probe (thin arrow) and p63-negative cancer cells (arrowhead) with more variable number if signals were due to truncation artifact and NKX3.1 deletion. FISH probes for 8p telomere, 8p centromere, NKX3.1, and MYC are shown in green, aqua, red, and gold, respectively. SpectrumAqua, FITC, Texas Red, SpectrumGold, and DAPI channels are shown after thresholding adjustments. Scale bar: 4.5 µm.

Normal Thresholds

Overall, 1147 cells were evaluated from 10 cases. Of these, 440 cells had non-overlapping nuclei and at least two 8p telomere and two chromosome 8 signals (4 control signals). Cases evaluated from the two sections of the TMA were not significantly different (p>0.05). According to the 99% confidence intervals, >20.4% of cells with less than two copies of NKX3.1 were consistent with NKX3.1 deletion and >2.5% of cells with more than two copies of MYC were consistent with MYC amplification (Table 4).

Table 4.

Normal Thresholds Determination.

| Alteration | Section of the TMA | n | Proportion of Cells with Alteration, % | 99% Confidence Interval, % | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NKX3.1 deletion (less than two copies) | First | 212 | 10.8 | 6.0–17.5 | |

| Second | 228 | 19.7 | 13.4–27.4 | ||

| Both | 440 | 15.5 | 11.3–20.4 | 0.11 | |

| MYC amplification (more than two copies) | First | 212 | 1.4 | 0.2–5.1 | |

| Second | 228 | 0 | 0–2.3 | ||

| Both | 440 | 0.7 | 0.08–2.5 | 0.26 |

Results of the evaluation of 10 normal prostatic tissues from 2 tissue microarray (TMA) sections are shown.

Patients

Five men treated in our institution for intermediate-risk bilateral PCa were selected. All men had clinical T1c PCa with pretreatment PSA ranging from 4.7 to 15.37 ng/ml (mean, 9.2 ng/ml). Gleason score was 7 (3 + 4) for the five biopsy specimens. The minimum percentage of tissue involved in selected specimens was 5%, as stated in the diagnostic report. ERG immunohistochemistry was positive in three biopsy specimens and negative in one, and both positive and negative foci were found in the last one (Table 5).

Table 5.

Characteristics of Selected Cases and 4FISH-IF Results.

| Case No. | Side | Involved Cores /Cores | % Involvement | ERG Status | Evaluated Cells | Chromosome 8/Cell | Cells with <2 Copies, NKX3.1, % | NKX3.1 Status | Cells with >2 Copies, MYC, % | MYC Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R | 3/3 | 30 | (+) | 60 | 2.06 | 7.1 | Normal | 3.6 | Amplified |

| 63 | 2.30 | 9.1 | Normal | 11.4 | Amplified | |||||

| L | 1 | 100 | (+) | 60 | 2.13 | 30.0 | Deleted | 14.0 | Amplified | |

| 2 | R | 1/2 | 20 | (–) | 46 | 2.16 | 13.9 | Normal | 0.0 | Normal |

| L | 3/3 | 30 | (–) | 60 | 2.03 | 8.9 | Normal | 1.8 | Normal | |

| 3 | R | 2/3 | 20 | (–) | 53 | 2.04 | 19.6 | Normal | 0.0 | Normal |

| (+) | 60 | 2.03 | 63.8 | Deleted | 1.7 | Normal | ||||

| L | 2/2 | 25 | (–) | 50 | 2.04 | 8.5 | Normal | 2.1 | Normal | |

| 60 | 2.03 | 13.5 | Normal | 3.8 | Amplified | |||||

| 4 | R | 2/2 | 5 | (+) | 35 | 2.20 | 3.7 | Normal | 0.0 | Normal |

| 60 | 2.00 | 16.7 | Normal | 0.0 | Normal | |||||

| L | 2/3 | 10 | (+) | 20 | 2.05 | 5.6 | Normal | 5.6 | Amplified | |

| 5 | R | 3/4 | 30 | (+) | 45 | 2.93 | 50.0 | Deleted | 12.5 | Amplified |

| L | 3/4 | 20 | (+) | 60 | 2.13 | 26.4 | Deleted | 3.8 | Amplified |

4FISH-IF, dual-gene fluorescence in situ hybridization combined with immunofluorescence; L, left; R, right.

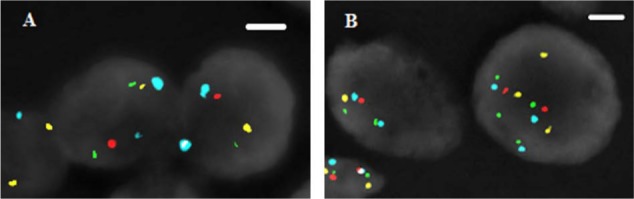

4FISH-IF

Overall, 10 biopsy blocks were submitted to 4FISH-IF. At both low and high power, IF allowed for easy identification of tumor foci and of intermingled benign glands (Fig. 2). In tumor foci, three major patterns were identified: cells with two copies of NKX3.1, cells with one copy of NKX3.1 (Fig. 3A), and cells with three to five 8q24 copies and a variable number of CEP8 and telomere 8 signals (Fig. 3B). In some cases, more than one pattern could be observed in the same tissue. Characteristics of the selected cases and corresponding 4FISH-IF results are shown in Table 5.

Figure 3.

(A) A high-power view of a case with NKX3.1 deletion, in which a cell with two chromosome 8 centromeres (aqua), two chromosome 8p telomeres (green), two 8q24 loci (MYC, gold), and one 8p21 locus (NKX3.1, red) can be seen. SpectrumAqua, FITC, Texas Red, SpectrumGold, and DAPI channels are shown after thresholds adjustments. Scale bar: 2 µm. (B) A high-power view of a case with both NKX3.1 deletion (left) and MYC amplification (right). The cell on the right has three chromosome 8 centromeres (aqua), four chromosome 8p telomeres (green), three 8q24 loci (MYC, gold), and two 8p21 loci (NKX3.1, red). SpectrumAqua, FITC, Texas Red, SpectrumGold, and DAPI channels are shown after thresholds adjustments. Scale bar: 2.0 µm.

Discussion

Herein, we report a 4FISH-IF protocol to determine both NKX3.1 and MYC status in the same diagnostic biopsy slide. This assay can be done in a standard molecular pathology laboratory. To our knowledge, this is the first description of a technique combining FISH to detect two genetic alterations in the same cell with IF, developed to be performed in situ on diagnostic FFPE tissues for use in standard clinical molecular pathology laboratories.

The assessment of two genes in the same cell may have important biological and clinical importance in PCa. Preclinical models and clinical data suggest that NKX3.1 allelic loss contributes to MYC overexpression, driving prostate cancer progression and aggression (Kim et al. 2007; Iwata et al. 2010; Anderson et al. 2012; Locke et al. 2012). As such, the capacity to assess those genetic alterations in one cell and in cell groups in human PCa might bring some new insights into PCa biology.

Also, this dual-gene FISH will allow for a thorough investigation of the multifocality in PCa, a phenomenon observed in more than 60% of PCa (Barry et al. 2007; Mehra et al. 2007). We here show that assessment of individual tumor foci could be of clinical significance, as some cases clearly showed heterogeneity not only in ERG status but also in NKX3.1 status. The 4FISH-IF will allow us to conduct cohort studies with very specific knowledge of NKX3.1 and MYC status for each patient. As more and more focal therapies are being introduced, the identification of the clinically significant clone(s) will become critical in the good clinical care of men with PCa.

The in situ nature of the 4FISH-IF is especially relevant to the characteristic PCa histomorphology. As a PCa focus can be very small on a biopsy specimen (less than 400 µm in diameter), it is not possible to perform confidently any molecular testing using a 50-µm-thick section as routinely done to perform PCR testing on clinical samples, for example. Both the DAPI counterstain and the very high power at which FISH must be read decrease the capacity of recognizing malignant glands. As PCa glands are typically intermingled with benign glands (Epstein et al. 2005), a major concern with every PCa FISH testing is the reliability of the results. Combining FISH with IF for p63—a marker of the basal cells surrounding benign glands—increases the reliability of FISH in PCa, allowing the reader to exclude benign glands from the analysis. As p63-positive basal cells are absent in prostate cancer, this does not interfere with FISH readings. This approach favors including false-negative benign glands in the analysis (e.g., adenosis)—which is already likely to happen in a standard FISH experiment—over the risk of excluding cancer cells. Optimally, we could have chosen a marker that is present in PCa cells and not in benign glands. As of today, there is only one PCa cell-“specific” marker, the p504s or AMACR. This marker can be negative in as much as 20% of the cancer cases and can be positive in benign and pre-neoplastic glands (Brimo and Epstein 2012). Those caveats, added to the fact that the cytoplasmic positivity in prostate cancer cells will interfere with FISH interpretation, prompted us to eliminate this choice. Other markers such as cytokeratins and PSA are positive in both benign and malignant prostate cells and could not be used.

From a technical perspective, we confirmed the importance of adequate controls to interpret correctly the assessed alterations. In our view, two copies of NKX3.1 with three copies of CEP8 and MYC can lead to the understanding that NKX3.1 is normal while there is an amplification of the chromosome 8 from centromere to 8q. Inclusion of the 8p telomere probe led to an improved understanding. For example, in case 5, we can acknowledge that most cells harbor three copies of chromosome 8, one of which shows a deletion of 8p21. The biological significance of such a phenomenon is still to be understood, both regarding NKX3.1 haploinsufficiency and MYC amplification in the context of chromosome 8 polysomy. On the other hand, two drawbacks of scoring only cells with the required two controls situated on the p arm of the chromosome 8 to assess NKX3.1 deletion are the possibility of (1) underestimating the number of 8q24 copies and (2) missing a chromosome 8 monosomy.

Last, the overall procedure adds approximately 2 hr to the standard FISH procedure. The pretreatments used and the IF procedures are usually well mastered in regular pathology laboratories. In our environment, the quality of the 4FISH-IF is easily reproducible. Through our technique optimization, we also showed that potential quality issues can be easily corrected without impairing the final reading of the slides. In a clinical scenario in which diagnostic tissue is scarce, this can be crucial. We also observed subjectively that the 4FISH-IF is associated with a decrease in the analytical time compared with traditional 4FISH. As such, we believe the implementation of the 4FISH-IF in other laboratories, including clinical laboratories, can be done without requiring extensive modification to the existing protocols.

We believe the concepts underlying the 4FISH-IF will be of great importance, not only in PCa but also in other contexts. HER2 amplification could be easily targeted with combined FISH and IF in breast and stomach cancers. CD20 and cytokeratins could be used to make sure the diagnostic and prognostic alterations are assessed in melanoma cells (Moore and Gasparini 2011), not in lymphocytes or keratinocytes. Deep sequencing data will reveal more and more genetic signatures of clinical importance, and we want to assess as much information as possible in the target cells. As identification of significant genetic alterations is already becoming a major companion to histopathological diagnosis, we believe the 4FISH-IF technique will aid in acquiring new relevant data both for the science and for the patients.

Acknowledgments

D. Trudel is part of The Terry Fox Foundation Strategic Health Research Training Program in Cancer Research at Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Ontario Institute of Cancer Research (Molecular Oncologic Pathology). This work would not have been possible without the close collaboration of the people from the Pathology Research Program Laboratory at UHN, especially Melanie Macasaet-Peralta. We also thank François Sanschagrin, PhD, and Michèle Orain for their helpful suggestions, and the work of Trevor Do for picture adjustments.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: A patent is pending for the proposed application.

References

- Anderson PD, Mckissic SA, Logan M, Roh M, Franco OE, Wang J, Doubinskaia I, Van Der Meer R, Hayward SW, Eischen CM, et al. 2012. NKX3.1 and MYC crossregulate shared target genes in mouse and human prostate tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 122:1907–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asatiani E, Huang WX, Wang A, Rodriguez Ortner E, Cavalli LR, Haddad BR, Gelmann EP. 2005. Deletion, methylation, and expression of the NKX3.1 suppressor gene in primary human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 65:1164–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry M, Perner S, Demichelis F, Rubin MA. 2007. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion heterogeneity in multifocal prostate cancer: clinical and biologic implications. Urology. 70:630–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethel CR, Faith D, Li X, Guan B, Hicks JL, Lan F, Jenkins RB, Bieberich CJ, De Marzo AM. 2006. Decreased NKX3.1 protein expression in focal prostatic atrophy, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, and adenocarcinoma: association with Gleason score and chromosome 8p deletion. Cancer Res. 66:10683–10690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen C, Bubendorf L, Voeller HJ, Slack R, Willi N, Sauter G, Gasser TC, Koivisto P, Lack EE, Kononen J, et al. 2000. Loss of NKX3.1 expression in human prostate cancers correlates with tumor progression. Cancer Res. 60:6111–6115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen C, Gelmann EP. 2010. NKX3.1 activates cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 70:3089–3097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen C, Stuart A, Ju JH, Tuan J, Blonder J, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Gelmann EP. 2007. NKX3.1 homeodomain protein binds to topoisomerase I and enhances its activity. Cancer Res. 67:455–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimo F, Epstein JI. 2012. Immunohistochemical pitfalls in prostate pathology. Hum Pathol. 43:313–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damber JE, Aus G. 2008. Prostate cancer. Lancet. 371:1710–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, Weinstein M, Tomaszewski JE, Schultz D, Rhude M, Rocha S, Wein A, Richie JP. 2001. Predicting prostate specific antigen outcome preoperatively in the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol. 166:2185–2188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL. 2005. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:1228–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurel B, Iwata T, Koh CM, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG, De Marzo AM. 2008. Molecular alterations in prostate cancer as diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic targets. Adv Anat Pathol. 15:319–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishkanian AS, Mallof CA, Ho J, Meng A, Albert M, Syed A, Van Der Kwast T, Milosevic M, Yoshimoto M, Squire JA, et al. 2009. High-resolution array CGH identifies novel regions of genomic alteration in intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Prostate. 69:1091–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishkanian AS, Zafarana G, Thoms J, Bristow RG. 2010. Array CGH as a potential predictor of radiocurability in intermediate risk prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 49:888–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata T, Schultz D, Hicks J, Hubbard GK, Mutton LN, Lotan TL, Bethel C, Lotz MT, Yegnasubramanian S, Nelson WG, et al. 2010. MYC overexpression induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and loss of NKX3.1 in mouse luminal epithelial cells. Plos One. 5:E9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Center MM, Ward E, Thun MJ. 2009. Cancer occurrence. Methods Mol Biol. 471:3–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Gu W, Yu J, Kumar-Sinha C, Cao X, Dash A, Wang L, et al. 2007. Integrative analysis of genomic aberrations associated with prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 67:8229–8239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindich R, Florl AR, Jung V, Engers R, Muller M, Schulz WA, Wullich B. 2005. Application of a modified real-time PCR technique for relative gene copy number quantification to the determination of the relationship between NKX3.1 loss and MYC gain in prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 51:649–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenacs T, Krenacs L, Raffeld M. 2010. Multiple antigen immunostaining procedures. Methods Mol Biol. 588:281–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kron K, Liu L, Trudel D, Pethe V, Trachtenberg J, Fleshner NE, Bapat B, Van Der Kwast T. 2012. Correlation of erg expression and DNA methylation biomarkers with adverse clinicopathological features of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 18:2896–2904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, Li C, Giacomini CP, Salari K, Huang S, Wang P, Ferrari M, Hernandez-Boussard T, Brooks JD, Pollack JR. 2007. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 67:8504–8510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke JA, Zafarana G, Ishkanian AS, Milosevic M, Thoms J, Have CL, Malloff CA, Lam WL, Squire JA, Pintilie M, et al. 2012. NKX3.1 haploinsufficiency is prognostic for prostate cancer relapse following surgery or image-guided radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 18:308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra R, Han B, Tomlins SA, Wang L, Menon A, Wasco MJ, Shen R, Montie JE, Chinnaiyan AM, Shah RB. 2007. Heterogeneity of TMPRSS2 gene rearrangements in multifocal prostate adenocarcinoma: molecular evidence for an independent group of diseases. Cancer Res. 67:7991–7995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MW, Gasparini R. 2011. FISH as an effective diagnostic tool for the management of challenging melanocytic lesions. Diagn Pathol. 6:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute of Canada, Canadian Cancer Society, Provincial/Territorial Cancer Registries & Public Health Agency of Canada 2011. Statistiques canadiennes sur le cancer. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Minei S, Hachiya T, Yoshida T, Takimoto Y. 2006. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of C_MYC amplification in stage TNM prostate cancer in Japanese patients. Int J Urol. 13:761–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sircar K, Yoshimoto M, Monzon FA, Koumakpayi IH, Katz RL, Khanna A, Alvarez K, Chen G, Darnel AD, Aprikian AG, et al. 2009. PTEN genomic deletion is associated with p-Akt and AR signalling in poorer outcome, hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Pathol. 218:505–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speel EJ, Herbergs J, Ramaekers FC, Hopman AH. 1994. Combined immunocytochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization for simultaneous tricolor detection of cell cycle, genomic, and phenotypic parameters of tumor cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 42:961–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speel EJ, Schutte B, Wiegant J, Ramaekers FC, Hopman AH. 1992. A novel fluorescence detection method for in situ hybridization, based on the alkaline phosphatase–fast red reaction. J Histochem Cytochem. 40:1299–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duin M, Van Marion R, Vissers K, Watson JE, Van Weerden WM, Schroder FH, Hop WC, Van Der Kwast TH, Collins C, Van Dekken H. 2005. High-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization of chromosome arm 8q: evaluation of genetic progression markers for prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 44:438–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kruithof-De M, Economides KD, Walker D, Yu H, Halili MV, Hu YP, Price SM, Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. 2009. A luminal epithelial stem cell that is a cell of origin for prostate cancer. Nature. 461:495–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Timme TL, Frolov A, Wheeler TM, Thompson TC. 2005. Combined c-Myc and caveolin-1 expression in human prostate carcinoma predicts prostate carcinoma progression. Cancer. 103:1186–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafarana G, Ishkanian AS, Malloff CA, Locke JA, Sykes J, Thoms J, Lam WL, Squire JA, Yoshimoto M, Ramnarine VR, et al. 2012. Copy number alterations of C-MYC and PTEN are prognostic factors for relapse after prostate cancer radiotherapy. Cancer. 118:4053–4062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]