Abstract

Rationale: Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) behaves as a complex genetic trait, yet knowledge of genetic susceptibility factors remains incomplete.

Objectives: To identify genetic risk variants for ARDS using large scale genotyping.

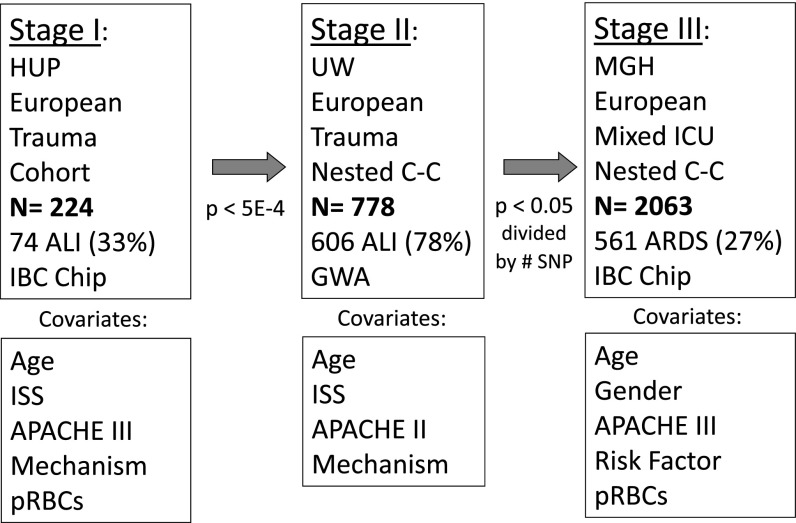

Methods: A multistage genetic association study was conducted of three critically ill populations phenotyped for ARDS. Stage I, a trauma cohort study (n = 224), was genotyped with a 50K gene-centric single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array. We tested SNPs associated with ARDS at P < 5 × 10−4 for replication in stage II, a trauma case–control population (n = 778). SNPs replicating their association in stage II (P < 0.005) were tested in a stage III nested case–control population of mixed subjects in the intensive care unit (n = 2,063). Logistic regression was used to adjust for potential clinical confounders. We performed ELISA to test for an association between ARDS-associated genotype and plasma protein levels.

Measurements and Main Results: A total of 12 SNPs met the stage I threshold for an association with ARDS. rs315952 in the IL1RN gene encoding IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RA) replicated its association with reduced ARDS risk in stages II (P < 0.004) and III (P < 0.02), and was robust to clinical adjustment (combined odds ratio = 0.81; P = 4.2 × 10−5). Plasma IL1RA level was associated with rs315952C in a subset of critically ill subjects. The effect of rs315952 was independent from the tandem repeat variant in IL1RN.

Conclusions: The IL1RN SNP rs315952C is associated with decreased risk of ARDS in three populations with heterogeneous ARDS risk factors, and with increased plasma IL1RA response. IL1RA may attenuate ARDS risk.

Keywords: functional genetic polymorphism, acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, IL-1 receptor antagonist, replication

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The genetic determinants of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) susceptibility remain incompletely understood. Few ARDS candidate genes' associations have been replicated in more than one population, or in more than one ARDS at-risk population.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We have identified a coding region variant in the IL1RN gene, encoding the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RA) protein, which demonstrates a consistent association with reduced ARDS susceptibility in two trauma populations and one heterogeneous, mixed intensive care unit population. The same genetic variant is associated with higher plasma IL1RA level among patients with severe trauma or septic shock, suggesting that some patients may be protected from ARDS by virtue of higher IL1RA.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a syndrome characterized by acute bilateral alveolar flooding and severe hypoxemia in the absence of clinical heart failure (1, 2). ARDS afflicts an estimated 190,000 people annually in the United States, and carries a mortality of between 30 and 40% (3). The syndrome can emerge after a variety of potential inciting events, such as sepsis, pneumonia, aspiration, and trauma. However, the risk of ARDS after potential at-risk injuries is not uniform; it appears that individual genetic variation contributes to a patient’s susceptibility to ARDS (4, 5). The pathophysiology underlying ARDS remains imprecisely understood, but dysregulated inflammation and altered permeability of the alveolocapillary membrane seem paramount (6). A number of studies have identified genetic variants in genes controlling inflammation or permeability that may confer differential risk of developing ARDS (7–12) or of ARDS mortality (9, 13). However, to date, many candidate gene studies have proven difficult to replicate, either due to small sample sizes, unrecognized population stratification, variability of the control population, or heterogeneity of the ARDS phenotype, particularly when ARDS is caused by different predisposing events (14).

To investigate the impact of potential candidate genes on ARDS susceptibility, we performed a multistage genetic association study using three critically ill populations at risk for ARDS. We hypothesized that we could efficiently identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with a differential risk for development of ARDS by using high-throughput candidate gene technology and a three-stage strategy to replicate results. To amplify the genetic signal, we used subjects with a homogeneous ARDS risk factor—severe trauma—in stages I and II, and then tested generalizability of replicating SNPs in a third population with heterogeneous ARDS risk factors (stage III). We assayed plasma from a subset of subjects in stage I and from an independent population with septic shock to test for potential functional implications of ARDS-associated genotypes. Some results have previously been reported in the form of abstracts (15).

Methods

Patients

Stage I included patients of European ancestry (EA) with severe trauma admitted to the surgical intensive care unit (ICU) of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), as previously described (11, 12, 16). In stage II, patients with trauma admitted to the Harborview Medical Center ICU for 48 hours or longer were prospectively enrolled and followed for organ failure (17). A subset of EA ARDS cases and controls were shared with the Trauma-associated ARDS SNP Consortium (TASC) (14). Subjects with stage III were EA adults admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) ICU with one or more risk factor for ARDS (18, 19). To confirm functional associations, we used plasma from stage I where available, and from a prospective severe sepsis cohort at HUP. Eligible subjects with sepsis met American College of Chest Physicians consensus criteria (20) for septic shock on presentation to the emergency department or medical ICU. At each site, the Institutional Review Board and/or Human Subjects Committee reviewed and approved the study. Subjects were designated as ARDS cases if they met all Berlin criteria for mild, moderate, or severe ARDS (2), corresponding to previous consensus criteria for acute lung injury (1), while intubated and mechanically ventilated (11, 12, 17–19, 21). Chest radiograph interpretation was performed by physician investigators (phase I and III) or trained study personnel (phase II) to characterize ARDS (17, 21, 22).

Genotyping, Sequencing, and ELISA

DNA was extracted from buffy coats or whole blood of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid blood samples. Laboratory personnel were unaware of the ARDS status of each sample. We performed a multistage study beginning with the most homogeneous population (HUP) and a 50K SNP array—the ITMAT, Broad Institute, CARe Consortium (IBC) chip (Illumina, San Diego, CA)—designed to assay candidate genes and pathways affecting cardiovascular, pulmonary, and metabolic phenotypes (23). Out of roughly 2,000 genes covered by the IBC chip, 30 of 35 (86%) genes previously associated with ARDS are included (see Table E1 in the online supplement) (24, 25). The IBC array covers genes with higher density than most genome-wide platforms (7, 23, 25–29). Stage II was genotyped with the Human 610-quad (Illumina), and results were filtered for the SNPs passing stage I at P < 5 × 10−4 (7, 30). Calls for nongenotyped markers were imputed using MaCH and 1,000 Genomes European haplotypes from the 11/23/10 release (31, 32). Only European haplotypes were used for imputation to ensure accuracy given that the stage II population had been previously filtered to remove non-Euopean outliers (14, 33). In stage III, trauma-associated ARDS SNPs were tested in subjects with heterogeneous ARDS risk factors genotyped with the IBC chip. Repeat genotyping of roughly 10% samples was performed to confirm positive findings. DNA from 24 subjects of EA with stage I was sequenced by PCR to characterize a variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) region of intron 4 of the IL1RN gene. Primer design and sequencing was as previously described (7), with VNTR calls made by manual inspection and counting. Primer sequences are provided in Table E2. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between sequenced markers was determined using Haploview (34). Plasma from 31 subjects with septic shock drawn on the day of sepsis presentation, and from 106 subjects with trauma with available plasma was assayed for IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RA) by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical Analysis

A three-stage association study was performed (35). Analyses were restricted to subjects of genetically determined EA and adjusted for population structure as previously described (36–38). For each SNP, significance of odds ratios (ORs) was determined in PLINK (39) using the χ2 test assuming an additive model of genetic risk. We used logistic regression to adjust for clinical factors associated with ARDS at each stage, including age, APACHE (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) score, injury severity score and blunt mechanism (exclusive to trauma populations), sepsis (phase III only), and packed red blood cell transfusion (unavailable in phase II). Pooled trauma results using subject-level data were tested by logistic regression, and metaanalysis P values were obtained using METAL (39). Using Haploview (34), we inferred haplotypes based on stage I data and tested association with ARDS. Results are visualized using SNAP (41).

SNPs associated with ARDS at P value less than 5 × 10−4 in stage I were tested in stages II and III. This α threshold has been applied previously for the IBC array (42), and was chosen to achieve approximately 10 SNPs for replication, given that the IBC chip types approximately 30,000 nonrare polymorphic SNPs in EA subjects (10/30,000 = 3.3 × 10−4). In stage II, a Bonferroni-adjusted P value less than 0.05/number of SNPs tested was considered significant, and a P value less than 0.05 was significant for stage III, as we hypothesized that it would be rare for any SNP to display a consistent association with ARDS in three studies by chance (43). Epistasis was tested between two loci by logistic regression, including both a main effect for each variant and an interaction term combining them; an interaction term P value less than 0.10 was considered significant. Plasma IL1RA levels were compared between genotypes by rank-sum, nonparametric trend, and linear regression after quantile transformation. Detailed methods, including quality control thresholds, are provided in the online supplement (44, 45).

Detectable Relative Risk

For stage I, we calculated 80% power to detect α of 0.0005, assuming an additive model for detectable genotype relative risks in the range of 1.8–2.2 for minor allele frequencies (MAFs) greater than 0.05 (46).

Results

Patient Populations

In stage I, the HUP trauma cohort, over 2,000 subjects with trauma were screened for eligibility, of whom 521 met all eligibility criteria and 474 had adequate DNA available. A total of 224 (47.3%) of the subjects were of EA; 74 subjects of EA (33.0%) developed ARDS during the first 5 days after trauma. In stage II, 606 cases and 172 controls were shared with the TASC (14). The imbalance of cases to controls reflects the TASC study design, which used population-based controls in the discovery phase and critically ill trauma controls in replication; the present study used all EA Harborview cases and at-risk controls submitted to TASC. In stage III, 2,063 subjects were recruited from 2,786 consecutive ICU admissions; 561 were determined to be ARDS cases and 1,502 ARDS controls. Further details about the study populations, including relevant clinical covariates for each stage, are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. Severity of illness was comparable across all three populations. Severity of ARDS varied slightly by stage; the percentage of ARDS cases with moderate or severe ARDS was 91, 67, and 100% for stages I, II, and III, respectively (2). The MGH population (stage III) had heterogeneous ARDS risk factors, with the vast majority of subjects exhibiting sepsis as their risk factor for ARDS.

TABLE 1.

STUDY POPULATIONS AND AVAILABLE CLINICAL COVARIATES

| Variable | ARDS | No ARDS | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I: HUP trauma cohort |

|

|

|

| n |

74 |

150 |

|

| Moderate–severe ARDS* |

68 (91.9) |

— |

|

| Age |

41.4 ± 20.5 |

43.9 ± 20.0 |

0.27 |

| Male |

52 (69.3) |

106 (70.2) |

0.89 |

| Blunt trauma† |

71 (94.7) |

141 (93.4) |

0.71 |

| ISS |

26.4 ± 7.6 |

25.4 ± 7.3 |

0.34 |

| Modified APACHE III |

63.9 ± 25.1 |

59.6 ± 19.8 |

0.40 |

| Pulmonary contusion |

35 (46.7) |

47 (31.5) |

0.027 |

| Any pRBC first 24 h |

30 (41.1) |

38 (25.7) |

0.020 |

| Total pRBC first 24 h |

2.59 ± 4.8 |

1.0 ± 2.3 |

0.007 |

| Stage II: Harborview trauma case–control |

|

|

|

| n |

606 |

172 |

|

| Moderate–severe ARDS* |

412 (68.0) |

— |

|

| Age |

44.6 ± 20.0 |

33.8 ± 19.0 |

<0.001 |

| Male |

445 (73.4) |

133 (77.9) |

0.37 |

| Blunt trauma† |

550 (92.8) |

149 (86.1) |

0.007 |

| ISS |

26.9 ± 10.3 |

22.7 ± 9.7 |

<0.001 |

| APACHE II score |

24.8 ± 7.6 |

16.7 ± 7.7 |

<0.001 |

| Stage III: MGH mixed ICU nested case–control |

|

|

|

| n |

561 |

1,502 |

|

| Moderate–severe ARDS* |

561 (100) |

— |

|

| Age |

58.8 ± 18.1 |

62.5 ± 17.1 |

<0.001 |

| Male |

357(63.6) |

924 (61.5) |

0.048 |

| APACHE III |

75.4 ± 23.2 |

63.6 ± 22.5 |

<0.001 |

| Sepsis |

491 (87.5) |

1183 (78.8) |

<0.001 |

| Septic Shock |

357 (63.3) |

673 (44.8) |

<0.001 |

| Pneumonia |

394 (70.2) |

649 (43.2) |

<0.001 |

| Trauma | 44 (7.8) | 131 (8.7) | 0.16 |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE III = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation III; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; HUP = Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; ICU = intensive care unit; ISS = injury severity score; MGH = Massachusetts General Hospital; pRBC = packed red blood cell transfusion.

Continuous variables are shown as means ± SD, and categorical variables are shown as number (%) of total population.

Moderate–severe ARDS as categorized by the Berlin definition (2), with PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200, while receiving positive end-expiratory pressure ≥ 5 cm H2O.

“Blunt” refers to a blunt as opposed to a penetrating mechanism of trauma.

Figure 1.

Multistage large-scale genetic association study: summary. Stage I was designed to use the most homogeneous population (severely ill adult trauma subjects, injury severity score [ISS] ≥ 16, first 5 d after trauma) and a candidate gene–centric genotyping platform. In stage II, trauma-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) gene variants were tested for replication in a larger, more heterogeneous trauma population followed over their entire intensive care unit (ICU) course. In stage III, replicating variants were tested in a mixed ICU case–control population with various risk factors for ARDS, predominantly sepsis. Clinical adjustment was performed for each stage using the relevant covariates. Trauma populations were adjusted for ISS and mechanism of trauma, while all sites were adjusted for age and severity of illness. Because the trauma populations demonstrated significant sex imbalance, which caused model instability, only stage III was adjusted for sex. The stage III model also included ARDS risk factor (sepsis, pneumonia, aspiration, transfusion, or trauma). pRBC = packed red blood cell transfusion.

Genotyping Results: Stages I and II

Genotyping with the IBC chip in stage I yielded successful typing of 45,448 polymorphic SNPs with MAF greater than 0.01, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) P value greater than 10−4, and genotyping call rate greater than 95% (Table E3a). A total of 12 SNPs within 10 genes demonstrated an association with ARDS with additive model P less than 5 × 10−4. Stage I ARDS-associated SNPs are listed in Table 2, along with the gene annotation and MAF in ARDS and non-ARDS populations for each SNP.

TABLE 2.

STAGE I SINGLE-NUCLEOTIDE POLYMORPHISMS ASSOCIATED WITH ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME

| SNP | Gene | HWE P Value | ARDS MAF | No ARDS MAF | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10779329C |

TGFB2 |

0.84 |

0.10 |

0.27 |

0.30 (0.16–0.55) |

1.1 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs2494283T |

CHIT1 |

0.17 |

0.17 |

0.04 |

4.27 (2.03–9.00) |

1.3 × 10−4 |

Promoter |

| rs380092T |

IL1RN |

0.21 |

0.19 |

0.38 |

0.38 (0.23–0.63) |

1.4 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs28365063G |

UGT2B7 |

0.10 |

0.27 |

0.12 |

3.01 (1.70–5.35) |

1.6 × 10−4 |

Syn coding |

| rs2124458C |

CBS |

0.026 |

0.23 |

0.43 |

0.42 (0.27–0.66) |

1.8 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs315952C |

IL1RN |

0.61 |

0.17 |

0.34 |

0.37 (0.22–0.62) |

1.9 × 10−4 |

Syn coding |

| rs17624740C |

GPR98 |

1.0 |

0.17 |

0.06 |

3.80 (1.88–7.77) |

2.2 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs379863C |

ADA |

0.81 |

0.28 |

0.13 |

2.70 (1.59–4.67) |

2.7 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs8072266C |

FZD2 |

0.067 |

0.12 |

0.01 |

10.3 (2.91–36.8) |

3.1 × 10−4 |

3′ UTR |

| rs7865617T |

VLDLR |

0.84 |

0.12 |

0.27 |

0.34 (0.19–0.62) |

4.1 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs6145T |

VLDLR |

1.0 |

0.12 |

0.27 |

0.35 (0.19–0.63) |

4.9 × 10−4 |

Intron |

| rs7571879T | EPAS1 | 0.56 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 4.82 (1.99–11.7) | 4.9 × 10−4 | Intron |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI = confidence interval; HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF = minor allele frequency; OR = odds ratio; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphisms; Syn coding = coding SNP, synonymous; UTR = untranslated region.

A total of 12 SNPs within 10 genes demonstrated an association with ARDS with P values more extreme than 5 × 10−4, assuming an additive model of risk. These SNPs were carried forward for testing in stages II and III. Each SNP is listed with its minor allele in the European population, such that ORs > 1 indicate that the minor allele is the risk allele, and ORs < 1 indicate that the major allele is the risk allele for ARDS. Function refers to the location of the SNP with respect to its annotated gene, and whether the amino acid coding sequence is affected by the single base change. HWE P values are the result of the chi-square statistic testing HWE proportions in stage I.

In stage II, genotyping with the Human 610-quad assayed over 600,000 LD-bin–tagging SNPs, of which 530,626 passed all quality control measures (Table E3b); the genomic inflation factor for this set was 1.027. Results were filtered for the 12 SNPs passing stage I. Of the 12, 5 SNPs were directly genotyped by the 610-quad platform and 7 were imputed using 1,000 Genomes haplotypes (32) for 379 European individuals (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

SINGLE-NUCLEOTIDE POLYMORPHISMS ASSOCIATED WITH ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME IN STAGE II

| Gene | SNP | HWE P Value | ARDS MAF | No ARDS MAF | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage II genotyped SNPs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CHIT1 |

rs2494283T |

0.87 |

0.13 |

0.13 |

1.06 (0.73–1.55) |

0.77 |

| IL1RN |

rs315952C |

0.54 |

0.27 |

0.36 |

0.67 (0.52–0.88) |

0.0023 |

| CBS |

rs2124458C |

0.58 |

0.36 |

0.36 |

1.01 (0.78–1.31) |

0.92 |

| GPR98 |

rs17624740C |

1.0 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.95 (0.61–1.51) |

0.81 |

| ADA |

rs379863C |

0.37 |

0.21 |

0.19 |

1.11 (0.81–1.52) |

0.51 |

| Stage II imputed SNPs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| TGFB2 |

rs10779329C |

|

0.24 |

0.25 |

0.99 (0.70–1.41) |

0.97 |

| IL1RN |

rs380092T |

|

0.29 |

0.36 |

0.71 (0.52–0.96) |

0.026 |

| UGT2B7 |

rs28365063G |

|

0.15 |

0.16 |

0.98 (0.67–1.43) |

0.92 |

| FZD2 |

rs8072266C |

|

0.04 |

0.03 |

1.49 (0.70–3.15) |

0.30 |

| VLDLR |

rs7865617T |

|

0.23 |

0.25 |

0.93 (0.68–1.27) |

0.64 |

| VLDLR |

rs6145T |

|

0.22 |

0.24 |

0.88 (0.64–1.22) |

0.44 |

| EPAS1 | rs7571879T | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.75 (0.45–1.23) | 0.25 |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI = confidence interval; HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF = minor allele frequency; OR = odds ratio; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

The SNPs meeting the stage I threshold for significance were tested in the stage II population (Harborview trauma), genotyped with the human 610-quad platform. SNPs are listed depending on whether their association with ARDS was determined by direct genotyping or by imputation using European haplotypes in 1000 Genomes (32). The α level to declare significance in stage II was 0.05/12 SNPs, or ≤0.0042. Only one SNP met this threshold: rs315952 (bold text) in IL1RN. By imputation, rs380092, also in IL1RN and with strong linkage disequilibrium with rs315952 (r2 = 0.73), showed a marginal ARDS association that did not survive adjustment for multiple comparison testing. HWE P values are the result of the chi-square statistic testing HWE proportions for the entire stage II population.

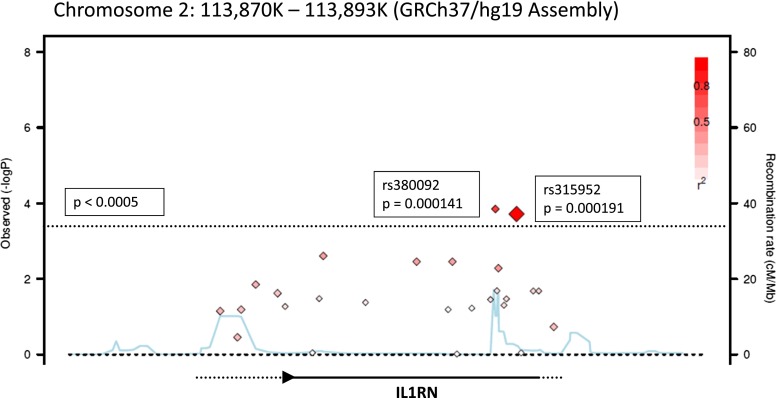

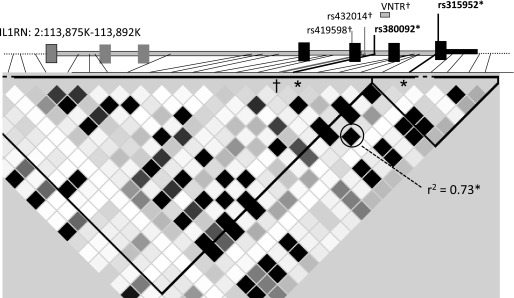

A total of 10 SNPs failed to replicate their association with ARDS in stage II, whereas 2 SNPs, both in the IL1RN gene, reproduced their association with decreased risk of ARDS (Table 3). Only one IL1RN SNP, rs315952C in the terminal exon of the gene, met the predetermined level of statistical significance for stage II (P < 0.0042). The IL1RN SNPs, rs380092 and rs315952, demonstrated significant LD with one another (r2 0.73) in the stage I population (Figure 2), and the haplotype tagged by rs315952C was also significantly associated with a decreased risk of ARDS, as shown in Table E4 (OR = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.22–0.64). The regional association plot (41) of IL1RN with ARDS is shown in Figure 3. Confirmatory genotyping of 213 subjects for rs315952 by multiplex PCR demonstrated 100% concordance with genotyping by the IBC chip.

Figure 2.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) plot of IL1RN. Grayscale within the triangular LD plot indicate pairwise LD measured by r2 in stage I, with black indicating high LD, gray moderate LD, and white absent LD. ARDS-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms rs315952 (*) and rs380092 (*) display strong LD (r2 = 0.73) and are associated with reduced ARDS risk. In contrast, markers highlighted with † (rs432014 and rs419598) are in LD with allele 2 of the variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism and demonstrate association with increased trauma-associated ARDS risk, but no association with all-cause ARDS risk. Plot created using Haploview (34).

Figure 3.

Regional association plot of IL1RN with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in stage I. Shown is a mini-Manhattan plot for single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) annotated to IL1RN created using the SNAP program (41). The y axis is the –log (P value) for an additive model association with ARDS, whereas the x axis represents the genomic locus of chromosome 2 on which IL1RN resides. Each diamond represents one genotyped SNP. The dashed line reflects the α level of significance (P = 0.0005), and diamonds that are above this line demonstrate association with ARDS at P values more extreme than 0.0005. The red coloration of each diamond indicates the degree of linkage disequilibrium (LD) between the SNP and rs315952 in the stage I population, with increased red intensity reflecting greater degree of LD. The blue line reflects the global recombination rate for this region of the genome.

Reproducibility of Associations in Nontrauma ARDS Risk Population

Having demonstrated a reproducible association between IL1RN variants and ARDS risk in two separate trauma populations, we next tested the generalizability of these SNPs in a mixed ICU population with heterogeneous risk factors for ARDS. Both rs315952 and rs380092, the SNPs associated with decreased trauma-ARDS risk, replicated their association with decreased all-cause ARDS risk, as shown in Table 4. We confirmed that none of our other stage I SNPs replicated their ARDS association in the mixed ICU population (Table E5); a marginal association between the very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) SNP rs6145T and ARDS was present in the stage III population, but the direction was opposite to that in the stage I population.

TABLE 4.

STAGE III REPLICATION RESULTS FOR THE TWO IL1RN SINGLE-NUCLEOTIDE POLYMORPHISMS THAT DEMONSTRATED AT LEAST MARGINAL ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME ASSOCIATION IN STAGES I AND II

| SNP | HWE P Value | ARDS MAF | No ARDS MAF | Stage III OR (95% CI) | Stage III P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs315952C |

0.018 |

0.24 |

0.28 |

0.83 (0.71–0.96) |

0.015 |

| rs380092T | 0.073 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.83 (0.72–0.97) | 0.017 |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI = confidence interval; HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF = minor allele frequency; OR = odds ratio; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Results for loci which failed to replicate their association in stage II are shown in the online supplement (see Table E5). The α level to declare significance in stage III was less than 0.05. Both stage I IL1RN variants, rs315952 and rs380092, replicated their associations with decreased risk of ARDS in the mixed intensive care unit population, for whom sepsis was the most common risk factor for ARDS. HWE P values are the result of the chi-square test for HWE proportions in the overall population.

Adjustment for Clinical Covariates and Metaanalysis

We tested whether the association between rs315952 and ARDS was affected by clinical covariates using multivariate logistic regression. The covariates chosen for adjustment varied by stage in accordance with trauma- and mixed ICU-specific risk factors and covariate availability (Figure 1). In adjusted analyses, rs315952C remained independently associated with decreased development of ARDS in all three populations, applying stage-specific multivariable models adjusting for injury severity, APACHE score, blunt trauma, red cell transfusion, and sepsis (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

POOLED TRAUMA AND METAANALYSIS RESULTS OF RS315952C–ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME ASSOCIATION ACROSS THREE POPULATIONS, WITH CLINICAL ADJUSTMENT

| Stage | n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value (Adjusted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I |

224 |

0.37 (0.22–0.62) |

1.9 × 10−4 |

0.39 (0.23–0.66) |

4.0 × 10−4 |

| II |

778 |

0.67 (0.52–0.88) |

2.3 × 10−3 |

0.66 (0.49–0.88) |

6.0 × 10−3 |

| I/II pooled |

1002 |

0.62 (0.53–0.80) |

2.3 × 10−5 |

0.66 (0.53–0.82) |

9.9 × 10−5 |

| III |

2063 |

0.83 (0.71–0.96) |

0.015 |

0.82 (0.70–0.97) |

0.021 |

| Metaanalysis | 3065 | 0.81 (0.72–0.91) | 1.1 × 10−5 | — | 4.2 × 10−5 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Subject-level data were available for stages I and II, which allowed for a pooled trauma association with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Stage III results were then metaanalyzed with the pooled trauma results as enacted in METAL (40), to obtain unadjusted and adjusted metaanalysis P values. We estimated the pooled OR by chi-square testing using absolute genotype counts in subjects with ARDS (78/467/689) versus those without ARDS (non-ARDS; 179/705/927). Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania trauma population was adjusted for age, injury severity score (ISS), modified Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III scores, blunt mechanism of injury, and packed red blood cell transfusion during the first 24 hours after trauma. The stage II (Harborview) population was adjusted for age, sex, ISS, APACHE II score, and blunt mechanism of injury. The Massachusetts General Hospital population was adjusted for age, sex, modified APACHE III scores, and clinical risk factors (bacteremia, sepsis without shock, sepsis with shock, pneumonia, trauma, aspiration, multiple transfusion). The IL1RN SNP rs315952 demonstrated a significant association with decreased ARDS risk that was robust to adjustment for clinical covariates in each stage. Modified APACHE scores reflect removal of the oxygenation component, as hypoxemia was collinear with a diagnosis of ARDS.

We next tested for the combined effect of rs315952C across all three stages. Individual-level data were combined for stages I and II to obtain pooled trauma estimates, and the association of rs315952C remained highly significant and robust to clinical adjustment, with an OR of 0.66 and P value of 9.9 × 10−5. A metaanalysis combining the stage III effect size and weight with the pooled trauma effect size resulted in an overall adjusted P value of 4.2 × 10−5 and unadjusted P of 1.1 × 10−5, with unadjusted OR of 0.81 (95% CI = 0.72–0.91), based on 3,041 subjects (Table 5).

Sequencing of IL1RN in ARDS Cases and Noncases

Given previous reports of association between a possibly functional VNTR structural variant in IL1RN and altered risk of ARDS or sepsis outcomes (47, 48), we sought to determine the LD structure between the VNTR and the block tagged by rs315952C. We sequenced the IL1RN gene from transcription start site to the 3′ untranslated region in 24 European subjects with stage I trauma split equally by ARDS status to understand the VNTR LD structure and to investigate potential functional variants in LD with our association signals. We estimated 95% power to detect SNPs with MAFs greater than 0.05 (49–51). Sequencing revealed 73 novel polymorphisms in addition to reported variants in National Center for Biotechnology Information dbSNP human build 132 (GRCh37), which annotates the VNTR allele 2 as rs71941886 (Table E6). No novel coding polymorphisms were identified.

The VNTR allele 2 variant (VNTR*2, two copies, in comparison to the more common four-copy allele 1, VNTR*1) (52) was not in LD with rs315952 (r2 < 0.1). Proxy SNPs for VNTR*2 with perfect LD (r2 = 1.0) were identified: rs432014 (stages I and III) and rs419598 (stage II) (41). In the combined trauma population (stages I and II), we observed an association between increased risk of ARDS and VNTR*2 (Table 6). In contrast, the VNTR-tagging SNP showed no association with ARDS in stage III: adjusted OR of 1.07 (0.91–1.26; P = 0.42; Table 6). A formal test for interaction between rs315952 and the VNTR on the risk for trauma-associated ARDS showed significant effect modification (interaction term P = 0.018) between VNTR*2 and rs315952C (Table E7). Whereas the adjusted main effect of rs315952C remained strong (P = 0.001) when accounting for the interaction term, the adjusted main effect of VNTR*2 was no longer significant (P = 0.62); thus, rs315952C exerted the independent effect in subjects with trauma.

TABLE 6.

ASSOCIATION OF IL1RN*2–TAGGING SINGLE-NUCLEOTIDE POLYMORPHISM AND INCREASED RISK FOR ACUTE RESPIRATORY DISTRESS SYNDROME IN TWO TRAUMA POPULATIONS

| Stage | VNTR*2 Tag SNP | ARDS MAF | No ARDS MAF | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I: HUP |

rs432014C |

0.32 |

0.23 |

1.65 (1.01–2.67) |

0.047 |

| II: Harborview |

rs419598C |

0.29 |

0.21 |

1.68 (1.18–2.39) |

0.004 |

| Pooled trauma |

|

0.29 |

0.22 |

1.52 (1.19–1.94) |

0.001 |

| III: MGH | rs432014C | 0.27 | 0.26 | 1.07 (0.91–1.26) | 0.42 |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI = confidence interval; HUP = Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; MAF = minor allele frequency; MGH = Massachusetts General Hospital; OR = odds ratio; SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphisms; VNTR = variable number of tandem repeat.

All stage I subjects were subsequently genotyped by Taqman methodology for rs419598; the correlation (r2) for rs432014 and rs419598 in this population was 0.92. Whereas rs432014 and rs419598 demonstrated association with increased ARDS risk in both trauma populations, rs432014 did not exhibit ARDS association in the mixed intensive care unit population. The HUP trauma population was adjusted for age, injury severity score (ISS), modified Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) III scores, blunt mechanism of injury, and packed red blood cell transfusion during the first 24 hours after trauma. The Harborview population was adjusted for age, sex, ISS, APACHE II score, and blunt mechanism of injury. The MGH population was adjusted for age, sex, modified APACHE III scores, and clinical risk factor.

Functional Analysis

To investigate potential functional consequences of rs315952C, we assayed plasma IL1RA levels in subjects in stage I with available plasma (n = 106) and subjects with septic shock from a distinct cohort enrolling at HUP (n = 31). Characteristics of subjects with available plasma and genotype are presented in Table E8. Plasma IL1RA levels were higher with increasing copies of the rs315952C allele: regression P value of 0.048 (Table 7). This effect was particularly pronounced for homozygous carriers of the C allele, the median IL1RA level of which was greater than 11,000 pg/ml, more than twice that of nonhomozygous carriers (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

INCREASING PLASMA IL-1 RECEPTOR ANTAGONIST LEVELS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASING COPIES OF RS315952

| |

rs315952 Genotype |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC (n = 25) | CT (n = 51) | TT (n = 61) | P Value | Regression P Value | |

| IL1RA, pg/ml, additive |

11,351 (2,000–24,587) |

5,176 (1,008–16,558) |

3,725 (1,229–8,185) |

0.071* |

0.048 |

| IL1RA, pg/ml, recessive | 11,351 (2,000–24,587) | 3,880 (1,193–11,832) | 0.049† | 0.045 | |

Definition of abbreviation: IL1RA = IL-1 receptor antagonist.

Levels are shown as median (interquartile range). The additive model tests three levels of genotype in an ordered fashion (CC versus CT versus TT), whereas the recessive model tests homozygous minor allele versus nonhomozygous (CC versus CT + TT). Plasma levels were then quantile transformed and tested by linear regression for an association with the C allele, which was statistically significant for both genetic models.

Plasma levels compared between genotype by nonparametric test of trend, assuming an additive genetic model.

Plasma levels compared between genotype by rank-sum test, assuming a recessive model of action.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a synonymous coding SNP in IL1RN, which displays a consistent association with reduced risk of ARDS in heterogeneous critically ill populations, is distinct from the well described VNTR polymorphism, and which associates with circulating IL1RA protein level (53). Taken together, our findings suggest that the association of rs315952C with decreased ARDS risk occurs on the basis of carriers expressing higher levels of IL1RA, which is protective for ARDS from diverse causes.

IL1RN is an attractive candidate gene for acute lung injury risk. IL-1β is considered to be among the most biologically active cytokines found in the lungs of patients with ARDS (54–56), and increases lung permeability in animal models and human lung epithelium (54, 57, 58). Experimental lung injury potentiated by IL-1β can be mitigated by treatment with IL1RA, the gene product of IL1RN (59). Nonsurvivors with ARDS have reduced levels of IL1RA in their Day 1 bronchoalveolar lavage compared with survivors (60). In addition, IL1RA has shown therapeutic promise in animal models of ARDS (61, 62), and is a critical mediator of the beneficial effect of mesenchymal stem cells in models of lung injury (63). There is strong evidence that an individual’s response to infection and injury has a heritable component (64, 65), and IL1RN is one of many cytokine genes exhibiting significant variation between ancestries (66, 67). The genetic determinants of circulating IL1RA levels are therefore of significant interest in ARDS.

In three critically ill populations, rs315952C associated with lower risk of ARDS. Given our finding of dramatically increased plasma IL1RA levels on presentation with trauma or septic shock, we hypothesize that the reduced risk of ARDS is mediated through increased IL1RA levels. It is notable that, although our sample size for the plasma analysis is small, our results in critical illness are consonant with a large metaanalysis of European subjects, which identified rs315952 as a protein quantitative trait locus for circulating IL1RA (P = 2.8 × 10−11), with increasing copies of the minor C allele associating with increased ambulatory plasma IL1RA levels (53). Among tagging SNPs, rs315952C was the strongest genetic predictor of IL1RA levels after adjusting for sex and age, accounting for 4% of the variation among myocardial infarction survivors and 0.7% among healthy population control subjects (53). Our results focus attention on the role of the inflammasome in ARDS pathogenesis (68), and the possibility that IL1RA may act as a molecular brake during trauma- or sepsis-driven injury.

Importantly, our findings do not support the IL1RN VNTR as the functional genetic variant driving the association with reduced ARDS risk. The dominant allele (VNTR*1) of the VNTR has 4 copies of an intronic 86–base pair repeat, whereas other alleles carry two copies (VNTR*2), or rarely between one and six copies (52). VNTR*2 has been associated with respiratory failure among children with pneumonia and with increased mortality among patients with severe sepsis (47, 48). The functional significance of the VNTR or linked variants is unclear; most studies report decreased circulating IL1RA levels with the haplotype tagged by VNTR*2, and rs419598C, a proxy SNP for VNTR*2 in Europeans, appears to regulate expression of resting IL-1β, but not IL1RA (69, 70). Conversely, VNTR*2 may result in higher levels of stimulated IL1RA production (71, 72). Although we identified an increased risk of trauma-associated ARDS for carriers of VNTR*2, the effect was no longer observed when accounting for interaction with rs315952C, the ARDS low-risk SNP. The two IL1RN loci are not in LD, but are not fully independent, in that VNTR*2 and rs315952C almost never coexist on the same haplotype. Our analysis determined rs315952C to display the more consistent effect on ARDS.

The association between rs315952 and ARDS was stronger for trauma populations than in the predominantly septic mixed ICU population. It may be that IL1RN signaling has a more prominent role in trauma-associated ARDS compared with sepsis-associated ARDS, or the relative homogeneity of the ARDS-inciting insult in trauma-restricted populations may have allowed detection of a stronger signal. It is also possible that the anti-inflammatory role of IL1RA could have deleterious effects on the ability to fight infection, and could even be a risk factor for developing severe sepsis. In a similar manner, it has been observed that a functional IL10 promoter variant causing higher levels of circulating IL10 seems to be associated with increased susceptibility to sepsis and sepsis-associated ARDS, but decreased mortality among septic subjects (73). Perhaps supporting an association between rs315952 and sepsis, the SNP deviated slightly from predicted HWE proportions (Table 4). Alternatively, significant HWE deviation may indicate genotyping error (74). While we cannot exclude this possibility, it seems unlikely given accuracy of IBC genotyping calls in stage I as well as manual inspection of genotype scatterplots. Nonetheless, additional replication in general ICU populations would be helpful.

The major strengths of our approach include prospective ARDS phenotyping, dense coverage of the inflammatory and permeability candidate genes typed on the IBC chip, and the implementation of a rigorous three-stage design progressing from the most homogeneous to most heterogeneous population. However, our study has several limitations. Our discovery cohort sample size was small. This limited our power to detect all but the strongest effects (relative risk > 1.8) in the discovery phase. Negative findings from stage I should be interpreted with caution, as the discovery phase was not powered to detect modest effect sizes, and the risk for a type II error is significant. Our associations were also limited to SNPs represented on the IBC chip, comprised of publicly available, validated SNPs, and thus there may be important genetic variation, including structural, copy number, or rare variation that we did not detect. Our sequencing was designed to determine the LD structure between the VNTR and our ARDS association signal, and might not fully discover rare variation within IL1RN. Furthermore, we were limited to the genes on the IBC chip, which included 86% of previously reported ARDS genetic risk factors among the approximately 2,000 high-priority metabolic, inflammatory, and vascular candidate genes covered (24, 75). A hypothesis-free approach, such as whole-genome analysis, would potentially highlight novel loci or other candidates of interest (14). Although our stage II population had genome-wide genotyping available, those results were filtered for only the 12 SNPs established in stage I. Genome-wide ARDS associations of the TASC population, which included our stage II population, have been published (14).

Although our findings were adjusted for population structure, our populations were limited to EA, and, thus, we cannot determine if the association between IL1RN and ARDS is present in non-European populations. Both rs315952 and the VNTR demonstrate significantly different minor allele frequencies in the HapMap Yoruban and African American populations compared with HapMap European populations (76, 77). In our previously reported study of African American patients with trauma, genotyping with the IBC chip did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with rs315952 or any other IL1RN variant, although that investigation was not powered to detect modest effect sizes (7). In addition, because the reported protein quantitative trait locus studies were performed exclusively in European populations (53), it remains unknown whether non-European populations manifest the same genetic determinants of circulating IL1RA.

ARDS continues to inflict significant morbidity and mortality upon critically ill patients (2, 3, 21, 78). A clearer understanding of genetic risk factors for ARDS susceptibility may help to identify subgroups best suited for participation in clinical trials, and may aid in the development of specific, targeted therapy for molecular subgroups as our understanding of ARDS pathogenesis and ARDS endophenotypes evolves. By demonstrating reduced ARDS incidence among carriers of a genetic variant that associates with higher circulating IL1RA, our study prioritizes future research to determine whether preventative or therapeutic applications of recombinant IL1RA may be helpful for some patients at risk for ARDS.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Harborview, and Massachusetts General Hospital patients and their families for participating in this research. In addition, they thank Feng Chen and Li Su for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to fund the study populations, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HL060290, HL079063), Harborview (GM066946), and Massachusetts General Hospital (HL060710). Additional NIH grants RC2HL101770, HL081619, HL090021, and HL102254 supported the genetic and molecular investigations described herein.

Author Contributions: N.J.M. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: N.J.M., J.D.C., M.M.W., G.E.O’K., and D.C.C. Acquisition of data: N.J.M., M.R., R.A., P.N.L., C.-C.S., P.T., J.D.C., M.M.W., G.E.O’K., and D.C.C. Analysis and interpretation of data: N.J.M., J.D.C., R.F., M.L., Y.Z., C.-C.S., R.G., S.B., M.R., R.A., and D.C.C. Drafting of the manuscript: N.J.M., J.D.C., M.M.W., G.E.O’K., and D.C.C. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: N.J.M., R.F., M.L., Y.Z., C.-C.S., P.T., R.G., S.B., M.R., P.N.L., R.A., G.E.O’K., M.M.W., D.C.C., and J.D.C. Statistical analysis: N.J.M., R.F., M.L., and Y.Z. Obtained funding: P.N.L., J.D.C., G.E.O’K., M.M.W., D.C.C., and N.J.M. Administrative, technical, or material support: R.A. Study supervision: N.J.M., J.D.C., M.M.W., G.E.O’K., and D.C.C.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1501OC on February 28, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, Stern EJ, Hudson LD. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong MN. Genetic epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome: implications for future prevention and treatment. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27:705–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes KC. Genetic determinants and ethnic disparities in sepsis-associated acute lung injury. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:195–201. doi: 10.1513/pats.200502-013AC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer NJ, Li M, Feng R, Bradfield J, Gallop R, Bellamy S, Fuchs BD, Lanken PN, Albelda SM, Rushefski M, et al. ANGPT2 genetic variant is associated with trauma-associated acute lung injury and altered plasma angiopoietin-2 isoform ratio. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1344–1353. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201005-0701OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao L, Grant A, Halder I, Brower R, Sevransky J, Maloney JP, Moss M, Shanholtz C, Yates CR, Meduri GU, et al. Novel polymorphisms in the myosin light chain kinase gene confer risk for acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:487–495. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0404OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arcaroli JJ, Hokanson JE, Abraham E, Geraci M, Murphy JR, Bowler RP, Dinarello CA, Silveira L, Sankoff J, Heyland D, et al. Extracellular superoxide dismutase haplotypes are associated with acute lung injury and mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:105–112. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1566OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye SQ, Simon BA, Maloney JP, Zambelli-Weiner A, Gao L, Grant A, Easley RB, McVerry BJ, Tuder RM, Standiford T, et al. Pre-B-cell colony–enhancing factor as a potential novel biomarker in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:361–370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-563OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzec JM, Christie JD, Reddy SP, Jedlicka AE, Vuong H, Lanken PN, Aplenc R, Yamamoto T, Yamamoto M, Cho HY, et al. Functional polymorphisms in the transcription factor NRF2 in humans increase the risk of acute lung injury. FASEB J. 2007;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7759com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christie JD, Ma SF, Aplenc R, Li M, Lanken PN, Shah CV, Fuchs B, Albelda SM, Flores C, Garcia JG. Variation in the myosin light chain kinase gene is associated with development of acute lung injury after major trauma. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2794–2800. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e318186b843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall RP, Webb S, Bellingan GJ, Montgomery HE, Chaudhari B, McAnulty RJ, Humphries SE, Hill MR, Laurent GJ. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is associated with susceptibility and outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:646–650. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christie JD, Wurfel MM, Feng R, O’Keefe GE, Bradfield J, Ware LB, Christiani DC, Calfee CS, Cohen MJ, Matthay M, et al. Genome wide association identifies PPFIA1 as a candidate gene for acute lung injury risk following major trauma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e28268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer NJ, Sheu CC, Li M, Chen F, Gallop R, Localio AR, Bellamy S, Kaplan S, Lanken PN, Fuchs B, et al. IL1RN polymorphism is associated with lower risk of acute lung injury in two separate at-risk populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:A1023. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Civil ID, Schwab CW. The abbreviated injury scale, 1985 revision: a condensed chart for clinical use. J Trauma. 1988;28:87–90. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shalhub S, Junker CE, Imahara SD, Mindrinos MN, Dissanaike S, O’Keefe GE. Variation in the TLR4 gene influences the risk of organ failure and shock posttrauma: a cohort study. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2009;66:115–123. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181938d50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su L, Zhai R, Sheu CC, Gallagher DC, Gong MN, Tejera P, Thompson BT, Christiani DC. Genetic variants in the angiopoietin-2 gene are associated with increased risk of ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1024–1030. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhai R, Zhou W, Gong MN, Thompson BT, Su L, Yu C, Kraft P, Christiani DC. Inhibitor kappaB-alpha haplotype GTC is associated with susceptibility to acute respiratory distress syndrome in Caucasians. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:893–898. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000256845.92640.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, Sibbald WJ. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–874. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah CV, Localio AR, Lanken PN, Kahn JM, Bellamy S, Gallop R, Finkel B, Gracias VH, Fuchs BD, Christie JD. The impact of development of acute lung injury on hospital mortality in critically ill trauma patients. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2309–2315. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180dc74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong MN, Zhou W, Williams PL, Thompson BT, Pothier L, Boyce P, Christiani DC. −308GA and TNFB polymorphisms in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:382–389. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating BJ, Tischfield S, Murray SS, Bhangale T, Price TS, Glessner JT, Galver L, Barrett JC, Grant SF, Farlow DN, et al. Concept, design and implementation of a cardiovascular gene-centric 50 K SNP array for large-scale genomic association studies. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer NJ, Daye ZJ, Rushefski M, Aplenc R, Lanken PN, Shashaty MG, Christie JD, Feng R. SNP-set analysis replicates acute lung injury genetic risk factors. BMC Med Genet. 2012;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao L, Barnes KC. Recent advances in genetic predisposition to clinical acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L713–L725. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90269.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flores C, Pino-Yanes Mdel M, Villar J. A quality assessment of genetic association studies supporting susceptibility and outcome in acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:R130. doi: 10.1186/cc7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pino-Yanes M, Ma SF, Sun X, Tejera P, Corrales A, Blanco J, Perez-Mendez L, Espinosa E, Muriel A, Blanch L, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase 3 gene associates with susceptibility to acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:740–745. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0292OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villar J, Perez-Mendez L, Flores C, Maca-Meyer N, Espinosa E, Muriel A, Sanguesa R, Blanco J, Muros M, Kacmarek RM. A CXCL2 polymorphism is associated with better outcomes in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2292–2297. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000284511.73556.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sapru A, Curley MA, Brady S, Matthay MA, Flori H. Elevated PAI-1 is associated with poor clinical outcomes in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1690-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuniga J, Buendia I, Zhao Y, Jimenez L, Torres D, Romo J, Ramirez G, Cruz A, Vargas-Alarcon G, Sheu CC, et al. Genetic variants associated with severe pneumonia in A/H1N1 influenza infection. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:604–610. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00020611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett J, Fry B, Maller J, Daly M. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Satagopan JM, Elston RC. Optimal two-stage genotyping in population-based association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:149–157. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cappola TP, Li M, He J, Ky B, Gilmore J, Qu L, Keating B, Reilly M, Kim CE, Glessner J, et al. Common variants in HSPB7 and FRMD4B associated with advanced heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:147–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.898395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hakonarson H, Grant SF, Bradfield JP, Marchand L, Kim CE, Glessner JT, Grabs R, Casalunovo T, Taback SP, Frackelton EC, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature. 2007;448:591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O’Donnell CJ, de Bakker PI. SNAP: a Web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tejera P, Meyer NJ, Chen F, Feng R, Zhao Y, O’Mahony DS, Li L, Sheu C-C, Zhai R, Wang Z, et al. Distinct and replicable genetic risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome of pulmonary or extrapulmonary origin. J Med Genet. 2012;49:671–680. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Hunter DJ, Thomas G, Hirschhorn JN, Abecasis G, Altshuler D, Bailey-Wilson JE, et al. Replicating genotype–phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447:655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pongpanich M, Sullivan PF, Tzeng JY. A quality control algorithm for filtering SNPs in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1731–1737. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Teo YY, Fry AE, Clark TG, Tai ES, Seielstad M. On the usage of HWE for identifying genotyping errors. Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71:701–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menashe I, Rosenberg PS, Chen BE. PGA: power calculator for case–control genetic association analyses. BMC Genet. 2008;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patwari PP, O’Cain P, Goodman DM, Smith M, Krushkal J, Liu C, Somes G, Quasney MW, Dahmer MK. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist intron 2 variable number of tandem repeats polymorphism and respiratory failure in children with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:553–559. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818d32f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arnalich F, Lopez-Maderuelo D, Codoceo R, Lopez J, Solis-Garrido LM, Capiscol C, Fernandez-Capitan C, Madero R, Montiel C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphism and mortality in patients with severe sepsis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;127:331–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frazer KA, Murray SS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:241–251. doi: 10.1038/nrg2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guey LT, Kravic J, Melander O, Burtt NP, Laramie JM, Lyssenko V, Jonsson A, Lindholm E, Tuomi T, Isomaa B, et al. Power in the phenotypic extremes: a simulation study of power in discovery and replication of rare variants. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:236–246. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kruglyak L, Nickerson DA. Variation is the spice of life. Nat Genet. 2001;27:234–236. doi: 10.1038/85776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarlow JK, Blakemore AI, Lennard A, Solari R, Hughes HN, Steinkasserer A, Duff GW. Polymorphism in human IL-1 receptor antagonist gene intron 2 is caused by variable numbers of an 86-bp tandem repeat. Hum Genet. 1993;91:403–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00217368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luotola K, Pietilä A, Alanne M, Lanki T, Loo B-M, Jula A, Perola M, Peters A, Zeller T, Blankenberg S, et al. Genetic variation of the interleukin-1 family and nongenetic factors determining the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist phenotypes. Metabolism. 2010;59:1520–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ganter MT, Roux J, Miyazawa B, Howard M, Frank JA, Su G, Sheppard D, Violette SM, Weinreb PH, Horan GS, et al. Interleukin-1beta causes acute lung injury via alphavbeta5 and alphavbeta6 integrin–dependent mechanisms. Circ Res. 2008;102:804–812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pugin J, Ricou B, Steinberg KP, Suter PM, Martin TR. Proinflammatory activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids from patients with ARDS, a prominent role for interleukin-1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1850–1856. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pugin J, Verghese G, Widmer MC, Matthay MA. The alveolar space is the site of intense inflammatory and profibrotic reactions in the early phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:304–312. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199902000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee YM, Hybertson BM, Cho HG, Terada LS, Cho O, Repine AJ, Repine JE. Platelet-activating factor contributes to acute lung leak in rats given interleukin-1 intratracheally. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L75–L80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.1.L75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roux J, Kawakatsu H, Gartland B, Pespeni M, Sheppard D, Matthay MA, Canessa CM, Pittet JF. Interleukin-1beta decreases expression of the epithelial sodium channel alpha-subunit in alveolar epithelial cells via a p38 MAPK–dependent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18579–18589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herold S, Tabar TS, Janssen H, Hoegner K, Cabanski M, Lewe-Schlosser P, Albrecht J, Driever F, Vadasz I, Seeger W, et al. Exudate macrophages attenuate lung injury by the release of IL-1 receptor antagonist in gram-negative pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1380–1390. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201009-1431OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donnelly SC, Strieter RM, Reid PT, Kunkel SL, Burdick MD, Armstrong I, Mackenzie A, Haslett C. The association between mortality rates and decreased concentrations of interleukin-10 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in the lung fluids of patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:191–196. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-3-199608010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chada M, Nögel S, Schmidt A-M, Rückel A, Bosselmann S, Walther J, Papadopoulos T, von der Hardt K, Dötsch J, Rascher W, et al. Anakinra (IL-1R antagonist) lowers pulmonary artery pressure in a neonatal surfactant depleted piglet model. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:851–857. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun D, Zhao M, Ma D, Liao S, Di C. Protective effect of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist on oleic acid–induced lung injury. Chin Med J (Engl) 1996;109:522–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ortiz LA, DuTreil M, Fattman C, Pandey AC, Torres G, Go K, Phinney DG. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sorensen TI, Nielsen GG, Andersen PK, Teasdale TW. Genetic and environmental influences on premature death in adult adoptees. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:727–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803243181202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chapman SJ, Hill AV. Human genetic susceptibility to infectious disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:175–188. doi: 10.1038/nrg3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Dyke AL, Cote ML, Wenzlaff AS, Land S, Schwartz AG. Cytokine SNPs: comparison of allele frequencies by race and implications for future studies. Cytokine. 2009;46:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zabaleta J, Schneider B, Ryckman K, Hooper P, Camargo M, Piazuelo M, Sierra R, Fontham E, Correa P, Williams S, et al. Ethnic differences in cytokine gene polymorphisms: potential implications for cancer development. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:107–114. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0358-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dolinay T, Kim YS, Howrylak J, Hunninghake GM, An CH, Fredenburgh L, Massaro AF, Rogers A, Gazourian L, Nakahira K, et al. Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1225–1234. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0003OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dixon AL, Liang L, Moffatt MF, Chen W, Heath S, Wong KCC, Taylor J, Burnett E, Gut I, Farrall M, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1202–1207. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clay FE, Tarlow JK, Cork MJ, Cox A, Nicklin MJ, Duff GW. Novel interleukin-1 receptor antagonist exon polymorphisms and their use in allele-specific mRNA assessment. Hum Genet. 1996;97:723–726. doi: 10.1007/BF02346180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reiner AP, Wurfel MM, Lange LA, Carlson CS, Nord AS, Carty CL, Rieder MJ, Desmarais C, Jenny NS, Iribarren C, et al. Polymorphisms of the IL1-receptor antagonist gene (IL1RN) are associated with multiple markers of systemic inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1407–1412. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Danis VA, Millington M, Hyland VJ, Grennan D. Cytokine production by normal human monocytes: inter-subject variation and relationship to an IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) gene polymorphism. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb05549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams PL, Zhou W, Wang MZ, Pothier L, Christiani DC. Interleukin-10 polymorphism in position −1082 and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:674–681. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00046405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yong Zou G, Donner A. The merits of testing Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the analysis of unmatched case–control data: a cautionary note. Ann Hum Genet. 2006;70:923–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meyer NJ, Christie JD. Genetic heterogeneity and risk for ARDS. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351121. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.The International HapMap 3 Consortium. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Boudreau A, Hardenbol P, Leal SM, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blank R, Napolitano LM. Epidemiology of ARDS and ALI. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:439–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]