Abstract

Adenosine concentrations are elevated in the lungs of patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, where it balances between tissue repair and excessive airway remodeling. We previously demonstrated that the activation of the adenosine A2A receptor promotes epithelial wound closure. However, the mechanism by which adenosine-mediated wound healing occurs after cigarette smoke exposure has not been investigated. The present study investigates whether cigarette smoke exposure alters adenosine-mediated reparative properties via its ability to induce a shift in the oxidant/antioxidant balance. Using an in vitro wounding model, bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to 5% cigarette smoke extract, were wounded, and were then stimulated with either 10 μM adenosine or the specific A2A receptor agonist, 5′-(N-cyclopropyl)–carboxamido–adenosine (CPCA; 10 μM), and assessed for wound closure. In a subset of experiments, bronchial epithelial cells were infected with adenovirus vectors encoding human superoxide dismutase and/or catalase or control vector. In the presence of 5% smoke extract, significant delay was evident in both adenosine-mediated and CPCA-mediated wound closure. However, cells pretreated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a nonspecific antioxidant, reversed smoke extract–mediated inhibition. We found that cells overexpressing mitochondrial catalase repealed the smoke extract inhibition of CPCA-stimulated wound closure, whereas superoxide dismutase overexpression exerted no effect. Kinase experiments revealed that smoke extract significantly reduced the A2A-mediated activation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase. However, pretreatment with NAC reversed this effect. In conclusion, our data suggest that cigarette smoke exposure impairs A2A-stimulated wound repair via a reactive oxygen species–dependent mechanism, thereby providing a better understanding of adenosine signaling that may direct the development of pharmacological tools for the treatment of chronic inflammatory lung disorders.

Keywords: cigarette smoke extract, adenosine, wound closure, oxidants

Clinical Relevance

Our experiments demonstrate that cigarette smoke exposure impairs adenosine A2A–stimulated wound repair, resulting in a deregulation of epithelial wound restoration. Considering that cigarette smoking is by far the primary risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and that adenosine concentrations are elevated in patients suffering with asthma and COPD, our present study also provides evidence for the involvement of either cigarette smoke–generated oxidants or a possible shift in the antioxidant/oxidant balance, which may play a pivotal role in deregulating the reparative nature of the adenosine A2A receptor. We believe our study provides a better understanding of the specific mechanisms governing the tissue-protective and tissue-destructive properties of adenosine signaling, with the potential to direct pharmacological tools toward the treatment of chronic inflammatory lung disorders such as asthma and COPD.

Normal epithelial lining provides the airway a barrier against the external environment, and is capable of initiating a variety of responses when injured, such as rapidly supporting repair processes. Chronic lung diseases associated with persistent lung inflammation and remodeling produce elevated concentrations of adenosine (1, 2). Adenosine, a purine nucleoside, exerts a modulatory effect on a large number of cell systems. Because of its extremely short half-life, the physiological actions of adenosine result from the binding of specific adenosine receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) and the activation of signal transduction systems (3). Increased concentrations of adenosine usually appear in the extracellular space when oxygen delivery is reduced or when the utilization of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in tissues is elevated (4). This increase in extracellular adenosine implies that adenosine functions as a signaling molecule when produced in response to cell damage, and that it can regulate tissue injury and repair (5). We previously demonstrated that the adenosine activation of the adenosine A2A receptor (A2AAR) promotes wound closure in bronchial epithelial cells (BECs) (6). However, in that study, when we exposed cells to cigarette smoke extract, the tissue-protective effect of adenosine was blocked. Previous studies demonstrated that cigarette smoke contains more than 4,000 chemical compounds, including approximately 1 × 1015 free radical molecules and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the gas phase, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radicals, and organic radicals, and approximately 1 × 1018 of these toxic species in the tar phase (7, 8), causing injury to the lung epithelium (7).

The mechanism by which adenosine-mediated wound healing and repair occur after exposure to cigarette smoke has not been investigated. Understanding that cigarette smoke alters the balance between tissue destruction and tissue repair, and that adenosine plays a pivotal role in airway wound repair, we hypothesized that smoke extract attenuates adenosine-mediated wound repair in bronchial epithelial cells via a ROS-dependent mechanism. We demonstrate that cigarette smoke creates a persistent cycle of injury mediated by oxidants, and particularly by the generation of hydrogen peroxide, which plays a pivotal role in deregulating the reparative nature of A2AAR.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Materials

Additional details are provided in the online supplement.

Cell Preparation

Primary-culture bovine bronchial epithelial cells (BBECs) were obtained from bovine lungs by a modification of a method described by Wu and Smith (9). Transformed human BEAS-2B and Nuli-1 bronchial epithelial cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). For these experiments, growth media were replaced with experimental media and with M199 medium in the absence of serum.

Adenoviral Vectors

All adenovirus vectors were purchased from Viraquest (North Liberty, IA), and constructed as previously described (10).

Cigarette Smoke Extract Preparation

The Tobacco–Health Research Division at the University of Kentucky supplied the cigarettes (unfiltered, code 2R1). Smoke extract was prepared as previously described (11).

In Vitro Wound Closure (Migration) Assay

BBECs and/or BEAS-2B cells were grown to confluence in 12-well, 96-well flat-bottomed or 60-mm tissue-culture dishes, and wounded as previously described [6]. Only wounds of similar size were used, with a typical wounding size of 782,500 ± 44,600 μm2. In some experiments, cell monolayers were “wounded” 48 hours after adenovirus infection. For signaling experiments, cell monolayers were wounded using a sterile “cell rake,” as described elsewhere (12).

Electric Cell Substrate Impedance Sensing Wounding (Migration) Assay

Nuli-1 cells were grown to confluence on electric cell substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) 96-well plate arrays (8W1E; Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY). Cells were wounded using an elevated field pulse of 1,400 μA at 32,000 Hz applied for 20 seconds, producing a uniform circular lesion of 250 μm in size, and wounds were tracked over a period of 24 hours. The impedance was measured at 4,000 Hz, normalized to its value at the initiation of data acquisition, and plotted as a function of time.

Determination of Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate–Dependent Protein Kinase and Protein Kinase C

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase (PKA) and/or protein kinase C (PKC) activity was determined in crude whole-cell fractions of bronchial epithelial cells, using a modification of procedures previously described (13).

Determination of Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate Concentration

The production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) was determined using a cAMP immunoassay kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as previously described (14).

RT-PCR of Adenosine Receptor mRNA in Cultured Cells

TaqMan real-time PCR was performed on BEAS-2B cells, stimulated in the presence or absence of 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE), as previously described (6).

Preparation of Membranes

Cell membranes from BEAS-2B cells were prepared according to the modification of a method described elsewhere (6). A NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) was used for the determination of protein concentrations.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was determined by a modification of procedures previously described (6). Results were expressed as the ratio of relative intensity of the target protein to that of the internal standard, β-actin. Immunoreactive bands were detected using Odyssey Infrared Imager Model 9201-03 (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

Determination of Intracellular Adenosine via Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

High-performance liquid chromatography analysis for the determination of intracellular adenosine concentrations was performed as previously described (14).

Detection of Smoke Extract–Generated Hydrogen Peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentrations were measured using a Fluorescent Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Detection Kit (Cell Technology, Mountain View, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until assayed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Determination of Glutathione and Oxidized Glutathione Concentrations

Glutathione (GSH) concentrations were evaluated using a commercial kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until assayed according to the manufacturer’s protocol for GSH and oxidized GSH measurements.

Cell Viability and Toxicity Assays

Cell viability and cytotoxicity induced by smoke extract were determined by cell media assays of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, using a commercially available kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

The wound-closure assays were performed with duplicate or triplicate wounds (in separate wells). Kinase assay were assayed in triplicate. All other assays were performed in triplicate, and repeated in three separate experiments with similar results. One-way ANOVA, followed by a multiple comparisons test, was used to determine significance. Paired t tests were used to pool data from multiple independent experiments. Significance was assigned at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Smoke Extract Stimulates Adenosine Receptor mRNA Expression and Adenosine A2A Receptor Protein Expression in Human Bronchial Epithelial BEAS-2B Cells

To better understand the mechanisms by which cigarette smoke alters adenosine signaling, we investigated the expression profile of adenosine receptors. BEAS-2B cells were exposed to media ± 5% smoke extract for 30 minutes. Unstimulated cells expressed all four adenosine receptors at a constant level. However, when BEAS-2B cells were treated with 5% smoke extract, concentrations of all four adenosine receptors were markedly elevated (5- to 10-fold; see Figure E1A in the online supplement). To identify whether elevated adenosine A2A receptor expression results in increased A2A receptor protein expression, cells were stimulated with 5% smoke extract. Western blot analysis revealed a considerable increase in the relative intensity of A2A receptor protein in cells that were stimulated with 5% smoke extract for either 2 or 24 hours, compared with unstimulated cells (see Figure E1B). For the A2A receptor, each band was quantified by densitometric analysis for the indicated time points in Figure E1C. These findings indicate that adenosine receptors exist in normal airways at a constant level, and that smoke-induced cell injury increases both adenosine receptor mRNA concentrations and A2A receptor protein expression.

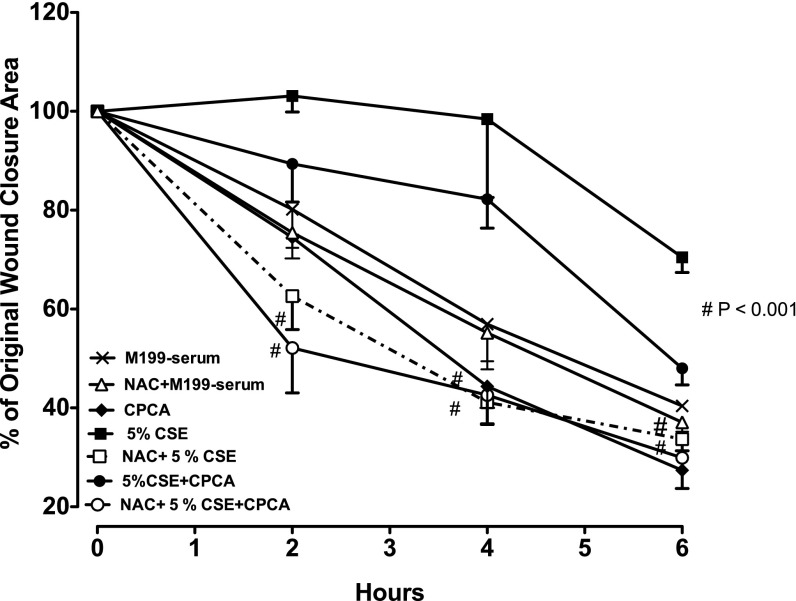

N-Acetylcysteine Attenuates Smoke Extract–Mediated Inhibition of A2A-Stimulated Wound Closure

Understanding that cigarette smoke contains oxidants and that exposure to smoke extract increases cellular oxidants (8), we investigated the role of a nonselective antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), in smoke extract–impaired A2A-mediated wound closure. BBECs were pretreated overnight with NAC (100 μM). Wound closure was assessed by digital imaging. Cells stimulated with 5′-(N-cyclopropyl)–carboxamido–adenosine (CPCA) alone revealed a significantly accelerated increase in the rate of wound closure at 4 hours, and this was maintained up to 6 hours, compared with medium control cells (Figure 1). This rate of closure was maintained, resulting in rapid wound closure during approximately the first 24 hours (data not shown). Cells exposed to smoke extract alone and in combination with CPCA revealed a significantly slower wound-closure rate than in media control cells (P < 0.001; Figure 1). Experiments with LDH revealed no cytotoxicity induced by smoke extract exposure (data not shown). NAC alone exerted no effect on cell migration in response to a wound (Figure 1). However, cells pretreated with NAC notably reversed smoke extract inhibition in CPCA-stimulated cells, and this was also observed in smoke extract–treated cells (P < 0.001; Figure 1). These findings suggest that the oxidants found in cigarette smoke may play a role in impairing A2A-mediated wound closure.

Figure 1.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) attenuates the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of adenosine A2A–stimulated wound closure. Bovine bronchial epithelial cells (BBECs) were pretreated overnight with 100 μM of NAC, a potent antioxidant. After pretreatment, the cells were wounded and then stimulated with or without 10 μM 5′-(N-cyclopropyl)–carboxamido–adenosine (CPCA) ± 5% cigarette smoke extract (CSE) in serum-free media. Cells pretreated with NAC significantly attenuated the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of adenosine-stimulated wound closure. Data represent the mean ± SE of triplicate wells within a single experiment. #P < 0.001, in comparison with smoke extract–exposed group and/or CPCA + smoke extract–exposed group at the same time point, according to ANOVA. The experiment was repeated twice using different preparations of BBECs, with similar results.

NAC Reversed the Smoke Extract–Mediated Inhibition of A2AAR-Stimulated Activation of PKA in Wounded Bovine Bronchial Epithelial Cells

We previously established that the adenosine occupancy of the A2A receptors stimulates wound closure, and this activation is mediated through PKA (6). We performed direct kinase activity measurements to determine whether smoke extract exposure altered the A2A-mediated activation of PKA. Smoke extract significantly blocked the CPCA stimulation of PKA activation, compared with CPCA alone (P < 0.01; Figure 2). However, NAC reversed the smoke extract attenuation of CPCA-mediated activation (P < 0.001; Figure 2). NAC alone exerted no effect on stimulating PKA activation, compared with the media-alone group. Interestingly, NAC lowered the smoke extract–treated group baseline activation of PKA below that of the media control group (P < 0.05; Figure 2). Collectively, the data suggest that smoke extract alters A2A-mediated PKA activation, and further indicate that cigarette smoke–induced oxidative stress is involved in modulating CPCA reparative properties.

Figure 2.

NAC reversed the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of adenosine A2A receptor (A2AAR)–stimulated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)–dependent protein kinase (PKA) activation in wounded bovine bronchial epithelial cells. BBECs were pretreated overnight with 100 μM NAC. The next day, cells were incubated in serum-free media, wounded, stimulated with or without 10 μM CPCA ± 5% smoke extract, and assessed for kinase activity. Smoke extract noticeably (**P < 0.01) reduced the CPCA-mediated activation of PKA, compared with the CPCA-stimulated group. NAC significantly (#P < 0.001) reversed the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of adenosine-stimulated PKA activation, compared with the smoke extract + CPCA − NAC–exposed group, according to ANOVA. Data represent the mean ± SE of triplicate wells within a single experiment. The experiment was repeated twice using different preparations of BBECs, with similar results.

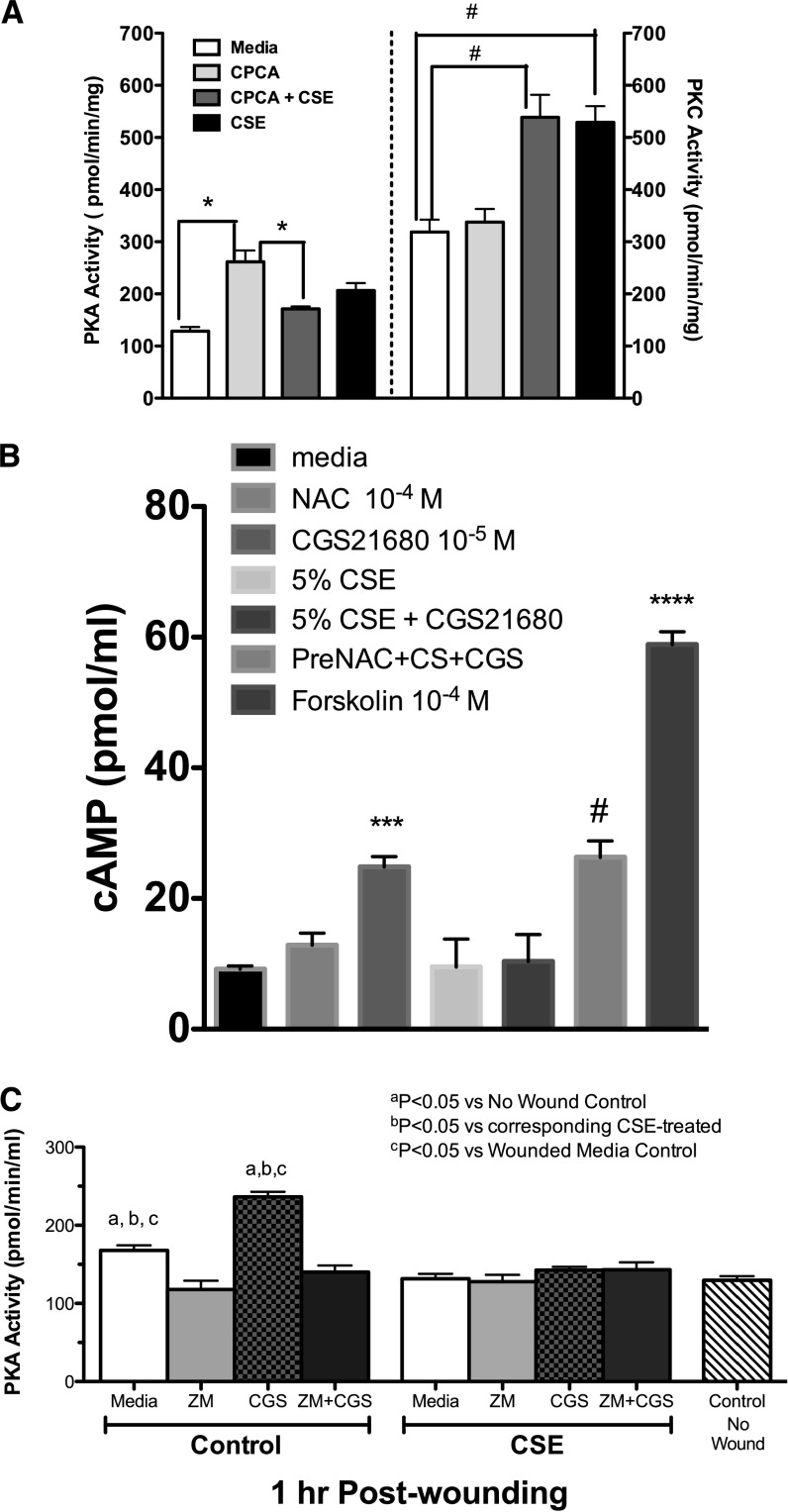

Smoke Extract Exposure Blunts the A2A-Mediated Activation of cAMP and the cAMP-Dependent Kinase PKA, and Stimulates Protein Kinase C Activation in Wounded Bronchial Epithelial Cells

We previously established that a wounded bronchial epithelial cell monolayer stimulated with adenosine or CPCA via the A2A receptor activates PKA to enhance cell migration into a wound (15). Conversely, agents that activate protein kinase C (PKC), such as smoke extract and malondialdehyde–acetaldehyde–adducted protein (16, 17), slow cellular migration during wound repair. Based on these observations, we used direct kinase activity measurements to determine whether the smoke-extract inhibition of A2A-mediated wound closure changed the balance of PKC and PKA activation. We observed a significant increase (∼ 3-fold) in PKA activation when cells were stimulated with CPCA, compared with media-treated cells (P < 0.01; Figure 3A, left y axis). However, in the presence of smoke extract, a significant reduction in PKA activity was evident when compared with CPCA treatment (P < 0.01; Figure 3A, left y axis). Interestingly, we observed robust PKC activation when cells were stimulated with smoke extract alone (P < 0.001; Figure 3A, right y axis) or in combination with CPCA (P < 0.001; Figure 3A, right y axis), compared with media-treated cells. Cells pretreated with CPCA alone did not elicit PKC activation compared with control cells, but demonstrated significantly less PKC activity (P < 0.01; Figure 3A, right y axis) compared with smoke extract + CPCA–treated cells. cAMP experiments revealed that cells stimulated with CGS21680 (a selective A2A agonist; 10 μM) and exposed to cigarette smoke extract had decreased concentrations of cAMP, whereas pretreatment with NAC reversed this effect (Figure 3B; P < 0.001), compared with smoke extract + CGS2160–treated cells. Positive control groups were treated with 100 μM forskolin. As confirmation, wounded Nuli-1 cells were pretreated for 1 hour with a specific A2A antagonist, ZM241385, at a concentration (100 nM) effective in blocking A2A receptors (18–20). Stimulation with CGS2160 ± smoke extract revealed that A2A receptor activation is required for PKA activation, further corroborating that cigarette smoke extract blunts A2A-mediated PKA activity (Figure 3C). Collectively, these data suggest that smoke extract blocks the A2A-mediated activation of cAMP, subsequently inhibiting cAMP-dependent PKA activity. Furthermore, the data suggest that the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of A2A-stimulated PKA activation may involve oxidants causing shifts in the balance of kinase action toward PKC activation, which may account for the observed impaired A2A-dependent wound closure.

Figure 3.

Smoke extract exposure blunts the A2A-mediated activation of cAMP and cAMP-dependent kinase (PKA), and stimulates protein kinase C (PKC) activation in wounded bronchial epithelial cells. (A) Direct kinase activity measurement was used to determine the effects of smoke extract on the CPCA-mediated activation of PKA (left y axis) and the activation by smoke extract of PKC (right y axis). *P < 0.01; #P < 0.001. (B) CSE exposure blunts the A2A-mediated activation of cAMP. Monolayers of Nuli-1 cells were either pretreated for 1 hour with NAC (100 nM) and stimulated with CGS21680 (CGS; an A2A agonist) ± 5% smoke extract (CS), and cAMP activity was assayed. CGS21680 significantly increased the activation of cAMP, compared with media control cells (***P < 0.001). Smoke extract noticeably reduced the CGS21680-mediated activation of cAMP, compared with the CGS21680-stimulated group. NAC significantly (#P < 0.001) reversed the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of adenosine-stimulated cAMP activation, compared with the smoke extract + CGS21680 − NAC–exposed group. As a positive control, some cells were treated with 100 nM forskolin (a cAMP activator; ****P < 0.0001). Data represent the mean ± SE of triplicate wells within a single experiment. (C) Blocking A2A receptor reduces PKA activation in wounded cells. Wounded Nuli-1 cells were either pretreated for 1 hour with ZM241385 (ZM; 100 nM) and stimulated with CGS21680 ± 5% smoke extract, and PKA was assayed. CGS21680 significantly increased the activation of cAMP, compared with media control cells (P < 0.05). Smoke extract notably blunted CGS21680-stimulated PKA. Data represent the mean ± SE of three separate experiments performed in triplicate.

Smoke Extract Inhibits A2A-Stimulated Wound Closure

Our laboratory recently acquired the ECIS system for evaluating wound repair. This system provides a consistent area of injury (250 μm), and the measurements are automated, producing quantifying data in real time. Upon electrical injury, cell migration results in a rise in transepithelial impedance/resistance (TEER; ohms). Using this device, we duplicated the inhibitory effect of smoke extract exposure on A2A-mediated airway wound repair (Figures E3A–E3E). As confirmation, Nuli-1 cells were pretreated for 1 hour with ZM241385 (100 nM) and stimulated with CGS2160 ± smoke extract. The outcome revealed A2A receptor activation is required to promote wound closure. A marked decrease in TEER was evident when cells were pretreated with ZM241385 (Figure E3C). In the absence of A2A agonist, smoke extract alone impaired wound closure. However, in the presence of the A2A antagonist, ZM241385 further blunted A2A-stimulated wound closure (see E3D online). These experiments support the finding from our in vitro wounding model that smoke extract exposure impairs A2AAR repair, and provide a novel approach to evaluating cellular wounding activities with the ECIS biosensor technology.

Smoke Extract Exposure Generates H2O2 in Wounded Bronchial Epithelial Cells

Cigarette smoke generates approximately 1 × 1015 free radical molecules, including ROS. Considering that the short-acting radical superoxide can react with the long-acting radical semiquinone to produce H2O2 (21), we examined the generation of H2O2 by smoke extract, using the human transformed cell line BEAS-2B. Wounded cells exposed to smoke extract generated H2O2 maximally by 4 hours, and returned to baseline by 24 hours (Figure 4). In the absence of cells, the generation of H2O2 by smoke extract was concentration-dependent, whereas in the presence of nonwounded cells, smoke extract–generated H2O2 was moderately scavenged (data not shown). Collectively, these data demonstrate that smoke extract generates H2O2.

Figure 4.

Smoke extract exposure generates hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in wounded bronchial epithelial cells. Wounded monolayers of BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 5% smoke extract, and after 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours, the supernatants were collected, and H2O2 concentrations were measured. A significant release of H2O2 occurred in a time-dependent fashion (**P < 0.01, compared with baseline; #P < 0.001, compared with baseline). Error bars represent the SE of three separate experiments performed in duplicate. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

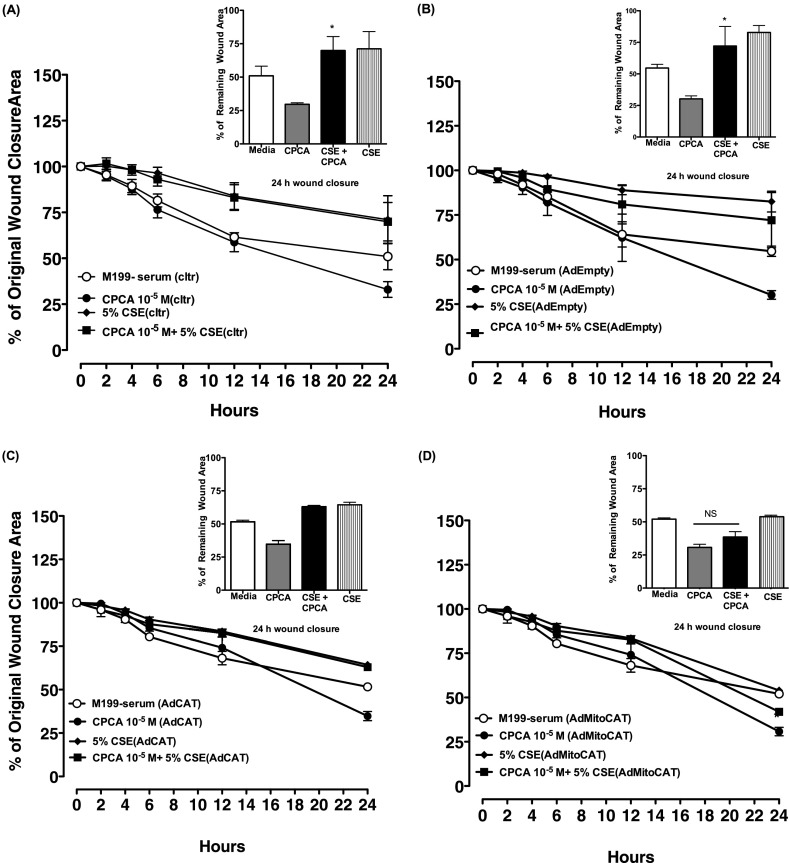

The Transfection of Catalase Blocks the Smoke Extract–Mediated Inhibition of Adenosine-Stimulated Wound Closure

Experiments using the adenovirus-mediated overexpression of catalase were performed to determine the functional role of H2O2 in the smoke extract–induced inhibition of adenosine wound closure. For theses experiments, we used our human transformed epithelial cell line, BEAS-2B, instead of our primary BBECs because of the difficulties associated with obtaining efficient viral infection with primary cells. BEAS-2B cells were infected with adenovirus encoding the H2O2 scavenging enzyme, catalase (AdCat), a mitochondrially targeted catalase (AdmitoCat), or empty vector (AdEmpty; control). Both nontransfected and transfected BEAS-2B cells were treated with serum-free media, the adenosine A2A receptor agonist CPCA (10 μM) ± 5% smoke extract, or 5% smoke extract alone, and wounding was assessed. As shown in Figure 5A, we observed significant and accelerated wound closure when nontransfected, wounded BEAS-2B cells were stimulated alone with CPCA within 24 hours, compared with media control cells. Consistent with our earlier experiments (Figure 5A), smoke extract treatment blocked CPCA-stimulated wound closure, and smoke extract alone further impeded cellular wound migration, as indicated at 24 hours. Five percent smoke extract–treated with CPCA wounds remained approximately 69% open and without CPCA wounds remained 71% open. AdEmpty transfected BEAS-2B cells also exhibited a rate of wound closure similar to that of nontransfected cells (Figure 5B), suggesting that the introduction of the adenovirus empty vector does not significantly affect the rate of wound closure subsequent to smoke extract treatment. AdCat did not effectively attenuate the smoke-induced inhibition of A2A-mediated wound closure (Figure 5C). However, AdmitoCat completely reversed the effects of smoke extract. (Figure 5D). In contrast to the effects of overexpressing mitoCat, the overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD, also known as SOD2), the mitochondrial-targeted superoxide scavenger, failed to modulate the smoke-induced inhibition of A2A-mediated wound closure (Figure E2D). Likewise, the overexpression of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD, also known as SOD1), which is primarily localized in the cytoplasm, did not attenuate the smoke-induced inhibition of A2A-mediated wound closure (Figure E2C). Collectively, these data suggest that mitochondrial-derived H2O2, but not superoxide, contributes to the smoke extract–mediated inhibition of A2AAR-stimulated wound closure.

Figure 5.

The adenovirus-mediated expression of mitochondrially targeted catalase blocks the smoke extract–induced inhibition of adenosine-stimulated wound closure. Smoke extract blocks CPCA-mediated wound closure in (A) noninfected (cltr), (B) empty vector (AdEmpty)–infected, and (C) adenovirus encoding H2O2 scavenging enzyme catalase (AdCat)–infected BEAS-2B cells in serum-free media, compared with CPCA alone (*P < 0.05). (D) In contrast, mitochondrially targeted catalase (AdMitoCat) reversed the CSE inhibition of CPCA-mediated wound closure, compared with CPCA alone (*P > 0.05). Error bars represent the SE of three separate experiments performed in duplicate. NS, no significance.

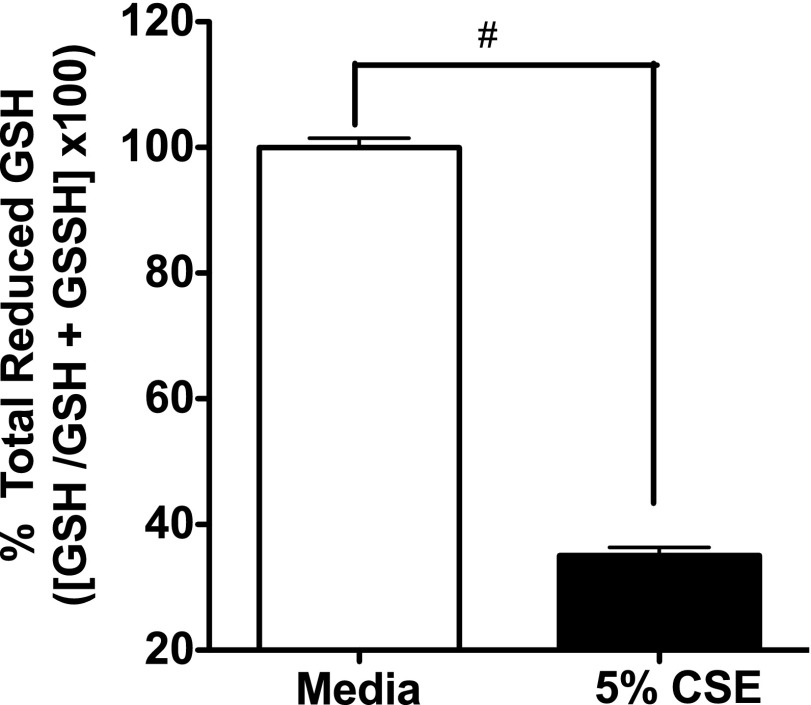

Smoke Extract Reduces Glutathione Concentrations in Bronchial Epithelial Cells

The GSH redox system is crucial in maintaining intracellular GSH homeostasis, and is one of the primary antioxidant systems in the lungs (21). This system uses GSH as a substrate in the detoxification of peroxides, including hydrogen peroxide (22). To investigate the mechanisms of smoke extract–generated ROS (H2O2) in BEAS-2B cells, we measured intracellular GSH concentrations. Our results demonstrate that 5% smoke extract treatment significantly depleted total GSH concentrations within 1 hour (P < 0.01; Figure 6). These data suggest that the depletion of the antioxidant GSH by smoke extract contributes to the disturbance in cellular redox homeostasis, leading to increased concentrations of H2O2, which may subsequently alter adenosine’s protective and reparative wound functions.

Figure 6.

Smoke extract reduces glutathione (GSH) concentrations in bronchial epithelial cells. Confluent monolayers of BEAS-2B cells were exposed to 5% smoke extract for 1 hour, and total GSH concentrations were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the mean ± SE of triplicate wells within a single experiment. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results. #P < 0.01, versus media control cells according to ANOVA.

Smoke Extract Exposure Increases Intracellular Adenosine in Bronchial Epithelial Cells

Adenosine is produced constitutively by cells under normal conditions, and can be produced in high concentrations at sites of tissue injury. To delineate the role of cigarette smoke exposure further in the deregulation of A2AAR reparative function, we investigated the role of smoke extract exposure on endogenous concentrations of adenosine. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis was performed to determine intracellular concentrations of adenosine in bronchial epithelial cells exposed for 1 hour to either 5% smoke extract or medium. A significant increase in intracellular adenosine accumulations was observed in smoke extract–treated cells compared with control cells (P < 0.01; Figure 7). These findings indicate that smoke increases endogenous lung adenosine concentrations, which may directly influence the dysregulation of A2AAR-mediated airway repair.

Figure 7.

Smoke extract exposure increases intracellular adenosine in bronchial epithelial cells. The determination of adenosine using isocratic, reversed-phase, high-performance liquid chromatography, coupled with an online detector for ultraviolet light absorbance and electrochemical activity, was performed in BEAS-2B. Cells were treated with either 5% smoke extract or medium for 1 hour. The smoke extract–treated cells demonstrated a significant elevation of intracellular adenosine (85 ± 10.7 pmole/106 cells; #P < 0.01, compared with 39 ± 11.7 pmole/106 control cells). Data represent the mean ± SD of two separate experiments performed in duplicate.

Discussion

Cigarette smoke exposure induces oxidant stress by shifting the balance between oxidants and antioxidants, and plays a putative role in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (23, 24). Numerous studies demonstrated that cigarette smoke exposure leads to impaired lung function, DNA damage, and the induction of stress signaling pathways and apoptosis (25–27). The present study was designed to investigate whether cigarette smoke exposure alters adenosine-mediated wound repair via its ability to induce a shift in the cellular oxidative environment. We explored this hypothesis by using primary bovine epithelial cells, BBECs, and the human transformed epithelial cell lines (BEAS-2B and/or Nuli-1) to demonstrate the similarity and functionality of the epithelium’s role in protecting the airways. LDH studies revealed no cytotoxicity induced by smoke extract exposure under these conditions. Moreover, experiments using NAC, a nonselective antioxidant, revealed a critical role for oxidants in mediating the inhibitory effect of smoke extract on adenosine-stimulated wound closure, suggesting that cigarette smoke exposure alters A2A-mediated airway wound repair via an oxidant-driven mechanism. Our data demonstrate that cigarette smoke creates a chronic cycle of injury mediated by oxidants, particularly the generation of hydrogen peroxide, which appears to play a pivotal role in deregulating the reparative property of A2AAR. Furthermore, cigarette smoke blunts cAMP activation, which results in changing A2A-stimulated PKA activity to shift toward a robust cigarette smoke–stimulated PKC activation. The present study revealed not only that smoke extract blocks A2A-stimulated cAMP and PKA activation, but that such alteration is also mediated through the generation of cigarette smoke–induced oxidants.

Adenosine exerts both anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective effects, and is usually generated at sites of tissue injury and inflammation (28, 29). We previously demonstrated that adenosine promotes wound closure when acting on its A2A receptor in mechanically wounded bronchial epithelial cells (15). Furthermore, our novel approach (ECIS) confirmed the involvement of the A2A receptor, and duplicated the results of our earlier mechanical wounding model. Our ECIS data revealed full restitution by measuring how increases in impedance occurred rapidly, with an average time of 4 to 5 hours in the absence of cigarette smoke exposure. However, in the presence of cigarette smoke exposure, this protective role was blocked, and the inhibition of the A2A receptor with ZM241385 potentiated this effect. Treatment with NAC restored A2A-mediated wound closure, implicating the role of cigarette smoke–generated ROS in modulating A2A-mediated wound closure in bronchial epithelial cells. Experiments using epithelial cells infected with mitochondrially targeted catalase revealed that scavenging mitochondrially produced H2O2 completely prevented the inhibition by cigarette smoke of A2A-stimulated wound closure. Unlike superoxide, H2O2 is capable of diffusing across membranes from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm, where it participates as a second messenger in the regulation of NF-κB and other intracellular signaling pathways (30, 31). On the other hand, superoxide is one of the first oxidants produced by cigarette smoke (23). However, our data demonstrate that intracellular SOD1, mitochondrial SOD2, and extracellular SOD (data not shown), which is the most abundant isoform of SOD found in the lung (32, 33), had no effect in reversing the cigarette smoke–mediated inhibition of A2A-stimulated wound closure. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that hydrogen peroxide is the prevailing cigarette smoke–generated oxidant involved in altering the adenosine reparative mode.

H2O2 has been implicated in many oxidative stress conditions, including the induction of growth arrest and cellular death (34, 35). However, evidence suggests that the H2O2-mediated oxidative stress response may shift to proliferation and conversion for cells exhibiting defects in growth pathway regulation (including damaged tight junctions), and apoptosis depends on the up-regulation of catalase activity and glutathione concentrations (35, 36). We observed that cigarette smoke–generated H2O2 increased significantly over time, reaching maximal concentrations by 4 hours. We speculate that cigarette smoke–generated H2O2 may lead to the activation of downstream signaling, which further impairs the A2A-mediated reparative role. Our data further establish that increased mitochondrially targeted catalase activity is crucial for effectively removing cigarette smoke–generated H2O2. Cigarette smoke exposure also significantly decreased intracellular reduced GSH concentrations. This decrease in intracellular GSH can indirectly affect the activity of glutathione peroxidase (GPx), another enzyme involved in H2O2 detoxification. Intracellular GSH is the principal substrate of GPx, and although we did not directly measure GPx activity, Dringen and Hamprecht described how H2O2 exposure induced a rapid oxidation of glutathione, with a decline in its intracellular form (37). This is supported by both our wounding (in vitro migration) and kinase experiments. In other words, the inhibitory action of NAC on smoke extract may have resulted from both the antioxidant action of NAC and its ability to increase cellular GSH.

Growing evidence suggests that adenosine plays a role in the pathogenesis of COPD and asthma (38–41). Smokers demonstrate significantly increased adenosine concentrations in airway lining fluid, and patients with COPD exhibit enhanced adenosine receptor density in their lung parenchyma (42, 43). In our study, we observed an increase in intracellular adenosine concentrations in the bronchial epithelial cells exposed to smoke extract. We believe this noticeable increase in intracellular adenosine resulted as a consequence of the hypoxic environment and the rapid hydrolysis of ATP induced by smoke extract exposure (44–46). Of the four receptors, the adenosine A2A receptor is strongly linked to controlling inflammation and tissue protection (47, 48). Our data demonstrate that cigarette smoke exposure not only increases the mRNA expression of A2AAR, but also that of the other adenosine receptors. Furthermore, cigarette smoke exposure significantly increased A2AAR protein expression. Collectively, our findings suggest that the tightly regulated balance of adenosine concentrations is susceptible to cigarette smoke–mediated oxidative stress, which may ultimately contribute to the altered state of adenosine’s tissue-protective/tissue-destructive signaling pathway.

The present study also explored the signaling mechanisms by which cigarette smoke exposure alters A2A-stimulated wound repair. A2AARs are similar to other Gs protein–coupled receptors, signaling through the activation of adenylate cyclase, the generation of intracellular cAMP, and the activation of PKA (6, 29). We expected the A2AAR activation of PKA, and hypothesized that cigarette smoke exposure would alter this activation, resulting in decreased A2A-mediated PKA activation. Smoke extract significantly reduced A2A-stimulated PKA, and was mediated by the smoke extract reduction of cAMP concentrations. These data further support earlier studies that revealed how cigarette smoke exposure decreases cAMP concentrations (49). Cigarette smoke has also been documented to activate PKC (50), and considering the differential roles of PKA and PKC, we investigated the smoke extract–mediated activation of PKC, and found a robust activation of PKC in A2A-stimulated wounded epithelial cells exposed to smoke extract. These studies indicate that smoke extract exposure activated PKC and simultaneously blocked A2A-mediated PKA activation, providing more evidence that crosstalk between PKA and PKC signaling occurs at the level of kinase activity regulation. This regulation of kinase activity appears to play a role in the cigarette smoke–mediated inhibition of A2A-stimulated wound repair. Furthermore, this shift in PKC signaling provides evidence for the involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation during the early events in epithelial cell migration after injury (51, 52).

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that cigarette smoke exposure modulates the adenosine A2A receptor’s protective and reparative modes in injured airway epithelial cells. The effects that we observed in our experiments suggest that cigarette smoke exposure contributes to sustained adenosine elevation, which is likely mediated by the shift in the antioxidant/oxidant balance, providing a potential explanation for the loss of the A2AAR reparative role (2, 39). The generation of hydrogen peroxide by cigarette smoke provides further evidence that this oxidant also acts as a signaling molecule that may indirectly affect the A2AAR reparative role by targeting other signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, providing the opportunity for a better understanding of adenosine’s role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory lung diseases such as asthma and COPD.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jane M. DeVasure for her exemplary technical support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant K01HL084684 (D.S.A.-G.), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant R37AA008769 (J.H.S.), and NIAAA grants R01AA017993 and VA101BX000728 (T.A.W.) from the National Institutes of Health.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0273OC on January 31, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Eckle T, Koeppen M, Eltzschig HK. Role of extracellular adenosine in acute lung injury. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:298–306. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00022.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Murthy JN, Zeng D, Belardinelli L, Blackburn MR. Alterations in adenosine metabolism and signaling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredholm BB, Jzerman I AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology: XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linden J. Molecular approach to adenosine receptors: receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:775–787. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn MR. Too much of a good thing: adenosine overload in adenosine–deaminase–deficient mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen-Gipson DS, Wong J, Spurzem JR, Sisson JH, Wyatt TA. Adenosine A2A receptors promote adenosine-stimulated wound healing in bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L849–L855. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00373.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung KF, Adcock IM. Multifaceted mechanisms in COPD: inflammation, immunity, and tissue repair and destruction. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1334–1356. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00018908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu R, Smith D. Continuous multiplication of rabbit tracheal epithelial cells in a defined, hormone-supplemented medium. In Vitro. 1982;18:800–812. doi: 10.1007/BF02796504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Lang JA, Sinnayah P, Ahmad IM, Spitz DR, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates the actions of angiotensin II in the central nervous system. Circ Res. 2002;91:1038–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043501.47934.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen-Gipson DS, Floreani AA, Heires AJ, Sanderson SD, MacDonald RG, Wyatt TA. Cigarette smoke extract increases C5a receptor expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:476–482. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.079822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spurzem JR, Gupta J, Veys T, Kneifl KR, Rennard SI, Wyatt TA. Activation of protein kinase A accelerates bovine bronchial epithelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L1108–L1116. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00148.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang H, Colbran JL, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Direct evidence for cross-activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase by cAMP in pig coronary arteries. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen-Gipson DS, Jarrell JC, Bailey KL, Robinson JE, Kharbanda KK, Sisson JH, Wyatt TA. Ethanol blocks adenosine uptake via inhibiting the nucleoside transport system in bronchial epithelial cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:791–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen-Gipson DS, Spurzem K, Kolm N, Spurzem JR, Wyatt TA. Adenosine promotion of cellular migration in bronchial epithelial cells is mediated by the activation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate–dependent protein kinase A. J Investig Med. 2007;55:378–385. doi: 10.2310/6650.2007.00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slager RE, Allen-Gipson DS, Sammut A, Heires A, DeVasure J, Von Essen S, Romberger DJ, Wyatt TA. Hog barn dust slows airway epithelial cell migration in vitro through a PKCalpha-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1469–L1474. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00274.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyatt TA, Kharbanda KK, Tuma DJ, Sisson JH, Spurzem JR. Malondialdehyde–acetaldehyde adducts decrease bronchial epithelial wound repair. Alcohol. 2005;36:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevigny CP, Li L, Awad AS, Huang L, McDuffie M, Linden J, Lobo PI, Okusa MD. Activation of adenosine 2A receptors attenuates allograft rejection and alloantigen recognition. J Immunol. 2007;178:4240–4249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan GW, Lee DD, Ross WG, DiVietro JA, Lappas CM, Lawrence MB, Linden J. Activation of A2A adenosine receptors inhibits expression of alpha 4/beta 1 integrin (very late antigen–4) on stimulated human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:127–134. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latini S, Bordoni F, Corradetti R, Pepeu G, Pedata F. Effect of A2A adenosine receptor stimulation and antagonism on synaptic depression induced by in vitro ischaemia in rat hippocampal slices. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahman I, MacNee W. Lung glutathione and oxidative stress: implications in cigarette smoke–induced airway disease. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L1067–L1088. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.6.L1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantin AM, Begin R. Glutathione and inflammatory disorders of the lung. Lung. 1991;169:123–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02714149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinnula VL. Focus on antioxidant enzymes and antioxidant strategies in smoking related airway diseases. Thorax. 2005;60:693–700. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.037473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacNee W. Pulmonary and systemic oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:50–60. doi: 10.1513/pats.200411-056SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kode A, Yang SR, Rahman I. Differential effects of cigarette smoke on oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine release in primary human airway epithelial cells and in a variety of transformed alveolar epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2006;7:132. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tkac J, Man SF, Sin DD. Systemic consequences of COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2007;1:47–59. doi: 10.1177/1753465807082374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, Liu X, Umino T, Skold CM, Zhu Y, Kohyama T, Spurzem JR, Romberger DJ, Rennard SI. Cigarette smoke inhibits human bronchial epithelial cell repair processes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:772–779. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.6.4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: pathophysiological roles. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;78:113–145. doi: 10.1254/jjp.78.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasko G, Pacher P. A2A receptors in inflammation and injury: lessons learned from transgenic animals. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:447–455. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zmijewski JW, Lorne E, Zhao X, Tsuruta Y, Sha Y, Liu G, Siegal GP, Abraham E. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I regulates neutrophil activation and severity of lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:168–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1602OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li WG, Miller FJ, Jr, Zhang HJ, Spitz DR, Oberley LW, Weintraub NL. H(2)O(2)-induced O(2) production by a non-phagocytic NAD(P)H oxidase causes oxidant injury. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29251–29256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamezaki F, Tasaki H, Yamashita K, Tsutsui M, Koide S, Nakata S, Tanimoto A, Okazaki M, Sasaguri Y, Adachi T, et al. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase ameliorates pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:219–226. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-264OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lund DD, Gunnett CA, Chu Y, Brooks RM, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase improves relaxation of aorta after treatment with endotoxin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H805–H811. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00907.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preston TJ, Muller WJ, Singh G. Scavenging of extracellular H2O2 by catalase inhibits the proliferation of HER-2/Neu-transformed rat–1 fibroblasts through the induction of a stress response. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9558–9564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishikawa Y, Kitamura M. Dual potential of extracellular signal–regulated kinase for the control of cell survival. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:696–701. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaya M, Sekizawa K, Masuda T, Morikawa M, Sawai T, Sasaki H. Oxidants affect permeability and repair of the cultured human tracheal epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L284–L293. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.2.L284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dringen R, Hamprecht B. Involvement of glutathione peroxidase and catalase in the disposal of exogenous hydrogen peroxide by cultured astroglial cells. Brain Res. 1997;759:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valls MD, Cronstein BN, Montesinos MC. Adenosine receptor agonists for promotion of dermal wound healing. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Y, Schneider DJ, Blackburn MR. Adenosine signaling and the regulation of chronic lung disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polosa R, Blackburn MR. Adenosine receptors as targets for therapeutic intervention in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Versluis M, ten Hacken N, Postma D, Barroso B, Rutgers B, Geerlings M, Willemse B, Timens W, Hylkema M. Adenosine receptors in COPD and asymptomatic smokers: effects of smoking cessation. Virchows Arch. 2009;454:273–281. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0727-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Driver AG, Kukoly CA, Ali S, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:91–97. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varani K, Caramori G, Vincenzi F, Adcock I, Casolari P, Leung E, Maclennan S, Gessi S, Morello S, Barnes PJ, et al. Alteration of adenosine receptors in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:398–406. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-869OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazar Z, Huszar E, Kullmann T, Barta I, Antus B, Bikov A, Kollai M, Horvath I. Adenosine triphosphate in exhaled breath condensate of healthy subjects and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inflamm Res. 2008;57:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s00011-008-8009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miro O, Alonso JR, Jarreta D, Casademont J, Urbano-Marquez A, Cardellach F. Smoking disturbs mitochondrial respiratory chain function and enhances lipid peroxidation on human circulating lymphocytes. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1331–1336. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.7.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mortaz E, Folkerts G, Nijkamp FP, Henricks PA. ATP and the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;638:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellman PI, Reece TB, Law MG, Gazoni LM, Singh R, Laubach VE, Linden J, Tribble CG, Kron IL. Adenosine A2A activation attenuates nontransplantation lung reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2008;149:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantell SJ, Stephenson PT, Monaghan SM, Maw GN, Trevethick MA, Yeadon M, Keir RF, Walker DK, Jones RM, Selby MD, et al. Inhaled adenosine A(2A) receptor agonists for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:1284–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh SP, Barrett EG, Kalra R, Razani-Boroujerdi S, Langley RJ, Kurup V, Tesfaigzi Y, Sopori ML. Prenatal cigarette smoke decreases lung cAMP and increases airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:342–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200211-1262OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyatt TA, Heires AJ, Sanderson SD, Floreani AA. Protein kinase C activation is required for cigarette smoke–enhanced C5a-mediated release of interleukin-8 in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:283–288. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.2.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung KF. p38 mitogen–activated protein kinase pathways in asthma and COPD. Chest. 2011;139:1470–1479. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luppi F, Aarbiou J, van Wetering S, Rahman I, de Boer WI, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. Effects of cigarette smoke condensate on proliferation and wound closure of bronchial epithelial cells in vitro: role of glutathione. Respir Res. 2005;6:140. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]