Abstract

Aims

In the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, digoxin reduced mortality or hospitalization due to heart failure (HF) in several pre-specified high-risk subgroups of HF patients, but data on protocol-specified 2-year outcomes were not presented. In the current study, we examined the effect of digoxin on HF death or HF hospitalization and all-cause death or all-cause hospitalization in high-risk subgroups during the protocol-specified 2 years of post-randomization follow-up.

Methods and results

In the DIG trial, 6800 ambulatory patients with chronic HF, normal sinus rhythm, and LVEF ≤45% (mean age 64 years, 26% women, 17% non-whites) were randomized to receive digoxin or placebo. The three high-risk groups were defined as NYHA class III–IV symptoms (n = 2223), LVEF <25% (n = 2256), and cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) >55% (n = 2345). In all three high-risk subgroups, compared with patients in the placebo group, those in the digoxin group had a significant reduction in the risk of the 2-year composite endpoint of HF mortality or HF hospitalization: NYHA III–IV [hazard ratio (HR) 0.65; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57–0.75; P < 0.001], LVEF <25% (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.53–0.71; P < 0.001), and CTR >55% (HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.57–0.75; P < 0.001). Digoxin-associated HRs (95% CI) for 2-year all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization for subgroups with NYHA III–IV, LVEF <25%, and CTR >55% were 0.88 (0.80–0.97; P = 0.012), 0.84 (0.76–0.93; P = 0.001), and 0.85 (0.77–0.94; P = 0.002), respectively.

Conclusions

Digoxin improves outcomes in chronic HF patients with NYHA class III–IV, LVEF <25%, or CTR >55%, and should be considered in these patients.

Keywords: Digoxin, Heart Failure, High risk, Morbidity, Mortality

Introduction

In the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, the largest randomized clinical trial (RCT) of digoxin efficacy in heart failure (HF), digoxin reduced the combined endpoint of hospitalization due to worsening HF and death due to progressive HF, but had no association with all-cause mortality.1 Taken together with the findings from the Prospective Randomized Study of Ventricular Function and Efficacy of Digoxin (PROVED) and Randomized Assessment of Digoxin on Inhibitors of the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (RADIANCE),2,3 this cumulative evidence was used by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve digoxin for use in HF in 1997 and, subsequently, all major national HF guidelines recommended the use of digoxin in HF.4,5 The outcomes used by the FDA and presented in the package insert for Lanoxin® tablets were the combined endpoints of death or hospitalization due to HF and death or hospitalization due to all causes during the first 2 years of follow-up.6 The DIG investigators hypothesized the effect of digoxin to be more pronounced during the first 2 years after randomization.7 These analyses also included three high-risk subgroups.6 The DIG report presented the effect of digoxin on HF death or HF hospitalization during the entire follow-up in these three subgroups.1 However, baseline characteristics of these high-risk subgroups and the effect of digoxin on 2-year outcomes have not been previously published in the peer-reviewed medical literature. The objective of the current study was to examine the effect of digoxin on 2-year HF death or HF hospitalization and total death or total hospitalization in high-risk HF patients in the DIG trial.

Methods

Study design and patients

The DIG trial was a placebo-controlled double-blind RCT of digoxin in HF. The detailed description of the rationale, design, implementation, patient characteristics, and results of the DIG trial has been reported previously.1,8 Briefly, the DIG trial enrolled 7788 ambulatory chronic HF patients in normal sinus rhythm from 302 centres in the USA and Canada from 1991 to 1993. Patients were randomized to receive either digoxin or placebo. Of these patients, 6800 had LVEF ≤45% (main study) and 988 had LVEF >45% (ancillary study).1,9 Most patients were receiving background therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and diuretics. Although data on beta-blocker use were not collected, the rate of beta-blocker use would be expected to be low, as these drugs were not yet approved for use in HF. The current study was based on a public-use copy of the DIG data obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which also sponsored the DIG trial.

High-risk patients

High risk was defined as NYHA class III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, or cardiothoracic ratio (CTR) >55%. Although the NYHA subgroup was specifically mentioned in the DIG trial protocol, both the DIG report and FDA analyses included the other two subgroups.1,6 Because the FDA determines the requirements for drug packaging, including findings of subgroup analyses,10 we used all three high-risk subgroups for the purpose of the current study. Findings from the RADIANCE and PROVED trials suggested that discontinuation of digoxin tended to worsen NYHA class symptoms, reduce LVEF, and increase the CTR.3 Therefore, it was expected that digoxin would be most effective in HF patients with higher NYHA class symptoms, lower LVEF, and larger hearts. To compare the effect of digoxin in low-risk HF patients, we assembled a cohort that excluded patients with any of the three high-risk characteristics, namely NHYA class III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, or CTR >55%.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the DIG trial was all-cause mortality during a median follow-up of 37.9 months. Vital status of all patients was collected up to 31 December 1995 and was 98.9% complete.11 Because the effect of digoxin was expected to be more pronounced in the first 2 years after randomization, the DIG trial protocol pre-specified separate analysis of the effect of digoxin on mortality and HF hospitalization during that period.7 Outcomes of interest for the current analysis were combined endpoints of HF mortality or HF hospitalization and all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization during the first 2 years after randomization.6

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of high-risk HF patients were compared using Pearson's χ2 and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Kaplan–Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to determine the effect of digoxin on various outcomes. Using a serum digoxin concentration (SDC) cut-off of 0.5–0.9 ng/mL and ≥1 ng/mL as low and high SDCs, respectively,12 we examined the association of low and high SDCs with the combined endpoints of 2-year all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization and 2-year HF mortality or HF hospitalization. We then repeated our analysis in low-risk HF patients. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with P-values <0.05 considered significant. SPSS-18 for Windows (Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Overall, DIG trial participants included 4367 high-risk patients. These patients had a mean age of 64 (SD ±11) years, 26% were female, and 17% were non-whites. Of these patients, 2223 (51%), 2256 (52%), and 2345 (54%) had NYHA class III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, and CTR >55%, respectively. Baseline characteristics of patients receiving digoxin and placebo were similar in all three high-risk subgroups, except for a lower prevalence of diabetes among patients with LVEF <25% receiving digoxin (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics in subgroups of high-risk heart failure patients in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial

| Variables, mean ± SD or n (%) | NYHA class III–IV |

LVEF <25% |

Cardiothoracic ratio >55% |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin (n = 1118) | Placebo (n = 1105) | Digoxin (n = 1127) | Placebo (n = 1129) | Digoxin (n = 1175) | Placebo (n = 1170) | |

| Age (years) | 65 ± 11 | 65 ± 11 | 63 ± 11 | 63 ± 11 | 64 ± 11 | 65 ± 11 |

| Female | 305 (27%) | 312 (28%) | 209 (19%) | 203 (18%) | 399 (34%) | 389 (33%) |

| Non-white | 167 (15%) | 150 (14%) | 180 (16%) | 195 (17%) | 279 (24%) | 280 (24%) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27 ± 6 | 27 ± 6 | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 6 | 27 ± 6 |

| Duration of HF (months) | 35 ± 41 | 32 ± 38 | 31 ± 36 | 32 ± 34 | 30 ± 38 | 30 ± 37 |

| LVEF (%) | 27 ± 9 | 26 ± 9 | 19 ± 4 | 18 ± 4 | 27 ± 9 | 27 ± 9 |

| LVEF <25% | 468 (41%) | 487 (44%) | 1127 (100%) | 1129 (100%) | 509 (43%) | 509 (44%) |

| Cardiothoracic ratio | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.07 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >55% | 499 (45%) | 487 (44%) | 509 (45%) | 509 (45%) | 1175 (100%) | 1170 (100%) |

| NYHA functional class | ||||||

| I | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 117 (10%) | 108 (10%) | 133 (11%) | 110 (9%) |

| II | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 542 (48%) | 534 (47%) | 543 (46%) | 573 (49% |

| III | 1042 (93%) | 1039 (94%) | 428 (38%) | 443 (39%) | 449 (38%) | 444 (38%) |

| IV | 76 (7%) | 66 (6%) | 40 (4%) | 44 (4%) | 50 (4%) | 43 (4%) |

| Signs or symptoms of HF | ||||||

| Dyspnoea at rest | 454 (41%) | 466 (42%) | 295 (26%) | 294 (26%) | 339 (29%) | 348 (30%) |

| Dyspnoea on exertion | 1046 (94%) | 1027 (93%) | 883 (50%) | 887 (79%) | 904 (77%) | 940 (80%) |

| Jugular venous distension | 265 (24%) | 277 (25%) | 195 (17%) | 215 (19%) | 244 (21%) | 243 (21%) |

| Pulmonary râles | 343 (31%) | 323 (29%) | 237 (21%) | 220 (20%) | 292 (25%) | 288 (25%) |

| Lower extremity oedema | 358 (32%) | 331 (30%) | 253 (22%) | 224 (20%) | 316 (27%) | 347 (30%) |

| Pulmonary congestion | 272 (24%) | 267 (24%) | 217 (19%) | 206 (18%) | 280 (24%) | 276 (24%) |

| No. of signs or symptoms of HFa | ||||||

| 0 | 0 (0%) | 2 (0.2%) | 15(1.3%) | 12 (1.1%) | 10 (0.9%) | 7 (0.6%) |

| 1 | 2 (0.2%) | 4 (0.4%) | 17 (1.5%) | 16 (1.4%) | 19 (1.6%) | 15 (1.3%) |

| 2 | 27 (2.4%) | 34 (3.1%) | 53 (4.7%) | 51 (4.5%) | 54 (4.6%) | 50 (4.3%) |

| 3 | 57 (5.1%) | 74 (6.7%) | 84 (7.5%) | 82 (7.3%) | 79 (7.3%) | 85 (6.7%) |

| ≥4 | 1032 (92.3%) | 991 (89.7%) | 958 (85%) | 968 (85.7%) | 1013 (86.6%) | 1013 (86.2%) |

| Co-morbid conditions | ||||||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 706 (63%) | 718 (65%) | 679 (60%) | 690 (61%) | 655 (56%) | 658 (56%) |

| Current angina pectoris | 394 (35%) | 380 (34%) | 287 (26%) | 265 (24%) | 261 (24%) | 283 (22%) |

| Hypertension | 522 (47%) | 497 (45%) | 489 (43%) | 459 (41%) | 621 (53%) | 625 (53%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 381 (34%) | 367 (33%) | 312 (28%)* | 267 (24%)* | 354 (30%) | 359 (31%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 576 (52%) | 593 (54%) | 507 (45%) | 509 (45%) | 567 (48%) | 562 (48%) |

| Primary cause of HF | ||||||

| Ischaemic | 787 (70%) | 770 (70%) | 747 (66%) | 738 (65%) | 728 (62%) | 705 (60%) |

| Hypertensive | 92 (8%) | 84 (8%) | 95 (8%) | 85 (8%) | 150 (13%) | 162 (14%) |

| Idiopathic | 167 (15%) | 170 (15%) | 213 (19%) | 215 (19%) | 217 (19%) | 203 (17%) |

| Others | 72 (6%) | 81 (7%) | 72 (6%) | 91 (8%) | 80 (7%) | 100 (9%) |

| Medications | ||||||

| Pre-trial digoxin use | 532 (48%) | 517 (47%) | 533 (47%) | 577 (51%) | 544 (47%) | 573 (49%) |

| ACE inhibitors | 1060 (95%) | 1036 (94%) | 1077 (96%) | 1082 (96%) | 1104 (94%) | 1110 (95%) |

| Diuretics | 983 (88%) | 969 (88%) | 950 (84%) | 957 (85%) | 1009 (86%) | 1017 (87%) |

| Nitroglycerines | 578 (52%) | 568 (51%) | 460 (41%) | 482 (43%) | 531 (45%) | 534 (50%) |

| Dose of study medication (mg/dL) | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | 0.24 ± 0.08 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 81 ±13 | 82 ± 13 | 81 ± 13 | 81 ± 13 | 80 ± 13 | 81 ± 13 |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Systolic | 124 ± 20 | 123 ± 21 | 122 ± 19 | 121 ± 19 | 125 ± 21 | 126 ± 21 |

| Diastolic | 74 ± 12 | 74 ± 12 | 75 ± 12 | 74 ± 11 | 75 ± 13 | 75 ± 12 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.33 ± 0.40 | 1.34 ± 0.41 | 1.3 ± 0.37 | 1.3 ± 0.36 | 1.28 ± 0.38 | 1.29 ± 0.37 |

HF, heart failure.

*P-value <0.05.

aClinical signs or symptoms included rales, elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral oedema, dyspnoea at rest or on exertion, orthopnoea, limitation of activity, S3 gallop, and radiological evidence of pulmonary congestion present in past or present.

Two-year heart failure mortality or heart failure hospitalization

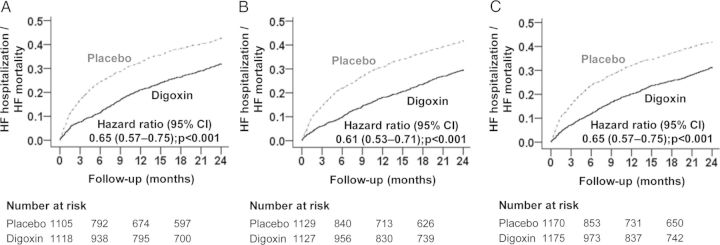

Compared with patients receiving placebo, digoxin-associated hazard ratios (HRs) for the combined endpoint of 2-year HF death or HF hospitalization in subgroups with NYHA class III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, and CTR >55% were 0.65 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57–0.75; P < 0.001], 0.61 (95% CI 0.53–0.71; P < 0.001), and 0.65 (95% CI 0.57–0.75; P < 0.001), respectively (Table 2 and Figure 1). Of the 4367 high-risk patients, 3079 had data on SDC, and digoxin significantly reduced the risk of HF death or HF hospitalization both at low SDC (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.46–0.68; P < 0.001) and at high SDC (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.59–0.87; P = 0.001; data not presented in the tables).

Table 2.

Combined mortality or hospitalization endpoints during the first 2 years after randomization by digoxin and placebo in subgroups of high-risk heart failure patients in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial

| Outcomes | % (events) |

Absolute risk differencea | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin | Placebo | ||||

| NYHA class III–IV | (n = 1118) | (n = 1105) | |||

| HF mortality or HF hospitalization | 29% (329) | 40% (445) | –11% | 0.65 (0.57–0.75) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 70% (779) | 72% (795) | –2% | 0.88 (0.80–0.97) | 0.012 |

| LVEF <25% | (n = 1127) | (n = 1129) | |||

| HF mortality or HF hospitalization | 27% (304) | 39% (444) | –12% | 0.61 (0.53–0.71) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 64% (716) | 68% (767) | –4% | 0.84 (0.76–0.93) | 0.001 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >55% | (n = 1175) | (n = 1170) | |||

| HF mortality or HF hospitalization | 29% (336) | 40% (465) | –11% | 0.65 (0.57–0.75) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 65% (764) | 69% (805) | –4% | 0.85 (0.77–0.94) | 0.002 |

| High risk (any of the above) | (n = 2191) | (n = 2176) | |||

| HF mortality or HF hospitalization | 26% (566) | 36% (783) | –10% | 0.66 (0.59–0.73) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 64% (1391) | 67% (1459) | –3% | 0.87 (0.81–0.94) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure.

aAbsolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percentage events in patients receiving placebo from those in patients receiving digoxin.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots for heart failure (HF) mortality or HF hospitalization by treatment groups in high-risk patients with chronic HF in the DIG trial: (A) NYHA class III–IV, (B) LVEF <25%, and (C) cardiothoracic ratio >55%. CI, confidence interval.

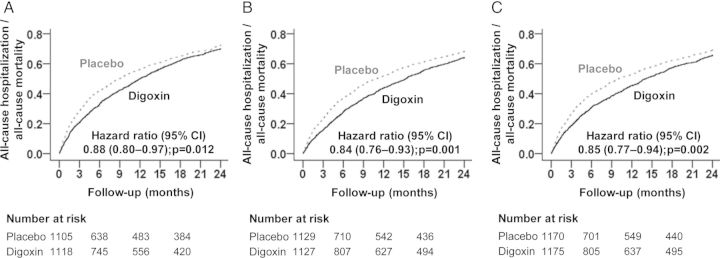

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots for all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization by treatment groups in high-risk patients with chronic heart failure (HF) in the DIG trial: (A) NYHA class III–IV, (B) LVEF <25%, and (C) cardiothoracic ratio >55%. CI, confidence interval.

Two-year all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization

Compared with the patients receiving placebo, digoxin-associated HRs for the combined endpoint of 2-year total death or all-cause hospitalization in subgroups with NYHA class III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, and CTR >55% were 0.88 (95% CI 0.80–0.97; P = 0.012), 0.84 (95% CI 0.76–0.93; P = 0.001), and 0.85 (95% CI 0.77–0.94; P = 0.002), respectively (Table 2 and Figure 2). Digoxin significantly reduced the risk of all-cause death or all-cause hospitalization at low SDC in those in the high-risk group (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.67–0.86; P < 0.001), but not at high SDC (HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.84–1.08; P = 0.437; data not presented in the tables).

Other 2-year outcomes

Digoxin significantly reduced the risk of HF and all-cause hospitalization in all three subgroups of high-risk HF patients (Table 3). In patients with CTR >55%, digoxin significantly reduced HF mortality (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.56–0.91; P = 0.007; Table 3), but this effect was not significant in the other high-risk subgroups. The associations of digoxin with other outcomes are displayed in Table 3. These associations were similar during the entire length of the study follow-up.

Table 3.

Individual mortality or hospitalization endpoints during the first 2 years after randomization by digoxin and placebo in subgroups of high-risk heart failurepatients in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial

| Outcomes | % (events) |

Absolute risk differencea | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin | Placebo | ||||

| NYHA class III–IV | (n = 1118) | (n = 1105) | |||

| All-cause mortality | 30% (340) | 30% (330) | 0% | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | 0.988 |

| CV mortality | 25% (276) | 25% (277) | 0% | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.686 |

| HF mortality | 12% (130) | 13% (147) | –1% | 0.86 (0.68–1.09) | 0.204 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 61% (678) | 64% (709) | –3% | 0.86 (0.78–0.96) | 0.005 |

| CV hospitalization | 47% (525) | 53% (590) | –6% | 0.79 (0.70–0.88) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 26% (290) | 37% (404) | –11% | 0.63 (0.54–0.74) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 44% (491) | 51% (565) | –7% | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | <0.001 |

| CV mortality or HF hospitalization | 39% (441) | 48% (533) | –9% | 0.73 (0.64–0.82) | <0.001 |

| LVEF <25% | (n = 1127) | (n = 1129) | |||

| All-cause mortality | 29% (321) | 29% (329) | 0% | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 0.600 |

| CV mortality | 24% (273) | 25% (287) | –1% | 0.94 (0.79–1.10) | 0.433 |

| HF mortality | 10% (116) | 13% (144) | –3% | 0.79 (0.62–1.01) | 0.062 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 54% (603) | 61% (683) | –7% | 0.79 (0.71–0.88) | <0.001 |

| CV hospitalization | 42% (475) | 50% (569) | –8% | 0.75 (0.66–0.84) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 24% (271) | 36% (406) | –12% | 0.60 (0.51–0.70) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 41% (466) | 50% (568) | –9% | 0.73 (0.65–0.83) | <0.001 |

| CV mortality or HF hospitalization | 38% (433) | 48% (542) | –10% | 0.71 (0.63–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >55% | (n = 1175) | (n = 1170) | |||

| All-cause mortality | 29% (335) | 28% (332) | +1% | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) | 0.933 |

| CV mortality | 23% (274) | 24% (277) | –1% | 0.97 (0.82–1.15) | 0.759 |

| HF mortality | 9% (107) | 13% (148) | –4% | 0.71 (0.56–0.91) | 0.007 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 57% (667) | 62% (727) | –5% | 0.83 (0.74–0.92) | <0.001 |

| CV hospitalization | 44% (521) | 53% (615) | –9% | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 27% (311) | 36% (421) | –9% | 0.67 (0.58–0.77) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 43% (506) | 50% (579) | –7% | 0.79 (0.70–0.89) | <0.001 |

| CV mortality or HF hospitalization | 40% (465) | 46% (543) | –6% | 0.77 (0.68–0.87) | <0.001 |

| High risk (any of the above) | (n = 2191) | (n = 2176) | |||

| All-cause mortality | 26% (570) | 26% (567) | 0% | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.806 |

| CV mortality | 21% (467) | 22% (475) | –1% | 0.96 (0.85–1.10) | 0.574 |

| HF mortality | 9% (192) | 11% (235) | –2% | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | 0.023 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 55% (1204) | 60% (1309) | –5% | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | <0.001 |

| CV hospitalization | 43% (935) | 49% (1076) | –6% | 0.79 (0.72–0.86) | <0.001 |

| HF hospitalization | 23% (509) | 33% (718) | –10% | 0.64 (0.57–0.72) | <0.001 |

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 39% (859) | 46% (1008) | –7% | 0.77 (0.70–0.84) | <0.001 |

| CV mortality or HF hospitalization | 36% (784) | 44% (946) | –8% | 0.75 (0.68–0.82) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure.

aAbsolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percentage events in patients receiving placebo from those in patients receiving digoxin.

Two-year outcomes in low-risk heart failure patients

The combined endpoint of 2-year HF death or HF hospitalization occurred in 14% and 18% of low-risk chronic HF patients receiving digoxin and placebo, respectively (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.62–0.94; P = 0.009; Table 4). Digoxin had no significant effect on any other outcomes, including the two combined endpoints of all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization (HR 1.07; 95% CI 0.96–1.20; P = 0.221) and cardiovascular mortality or HF hospitalization (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.73–1.03; P = 0.110; Table 4). Among the 2425 low-risk patients, 1785 had available data on SDC, and digoxin significantly reduced the risk of HF death or HF hospitalization at low SDC (HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.38–0.77; P = 0.001), but not at high SDC (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.72–1.44; P = 0.931).

Table 4.

Individual or combined endpoints during the first 2 years after randomization by digoxin and placebo in subgroups of low-risk heart failurepatients in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial

| Outcomes | % (events) |

Absolute risk differencea | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin (n = 1201) | Placebo (n = 1224) | ||||

| Low-risk (NYHA class I–II symptoms, EF >25%, and CTR <55%) | |||||

| HF mortality or HF hospitalization | 14% (167) | 18% (216) | –4% | 0.76 (0.62–0.94) | 0.009 |

| All-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization | 52% (623) | 49% (601) | +3% | 1.07 (0.96–1.20) | 0.221 |

| All-cause mortality | 12% (147) | 13% (158) | –1% | 0.95 (0.76–1.19) | 0.632 |

| CV mortality | 10% (119) | 9% (111) | +1% | 1.09 (0.84–1.41) | 0.512 |

| HF mortality | 3% (32) | 3% (41) | 0% | 0.80 (0.50–1.26) | 0.330 |

| All-cause hospitalization | 47% (564) | 45% (552) | +2% | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) | 0.355 |

| CV hospitalization | 33% (393) | 33% (405) | 0% | 0.98 (0.86–1.13) | 0.803 |

| HF hospitalization | 13% (155) | 17% (202) | –4% | 0.76 (0.62–0.94) | 0.009 |

| All-cause mortality or HF hospitalization | 22% (263) | 25% (307) | –3% | 0.85 (0.72–1.00) | 0.046 |

| CV mortality or HF hospitalization | 20% (240) | 22% (273) | –2% | 0.87 (0.73–1.03) | 0.110 |

CI, confidence interval; CTR, cardiothoracic ratio; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure.

aAbsolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percentage events in patients receiving placebo from those in patients receiving digoxin.

Discussion

Findings from the current study demonstrate that over half of chronic HF patients in the DIG trial had severe and more advanced disease as evidenced by the presence of NYHA III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, or CTR >55%, and that digoxin significantly improved outcomes in all three high-risk subgroups. The effect of digoxin was most pronounced on the combined endpoints of HF mortality or HF hospitalization, and could be observed regardless of SDC and in those without the high-risk characteristics. However, the effect on the combined endpoints of total mortality or total hospitalization was primarily observed in those receiving digoxin at low SDC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the effect of digoxin outcomes in the three pre-specified high-risk subgroups during the protocol-specified 2 years of follow-up.

Digoxin is the only positive inotrope that does not increase mortality.1 Furthermore, when used in lower doses resulting in lower SDC, it may also significantly reduce total mortality.12–14 Importantly, digoxin significantly reduces HF hospitalization, regardless of SDC, although the magnitude of this effect is greater at lower SDC.12 The superior effect of low-dose digoxin, also observed in the current analysis, has been attributed to its neurohormonal inhibitory effects.15–19 The lack of a significant effect on individual endpoints of total mortality is probably due to the high digoxin doses and the high SDC targets used in the DIG trial.1,7,8 Yet, in the DIG trial, there was significant reduction in total mortality during the first year of follow-up,20 and a trend toward reduced risk of death due to progressive HF in patients receiving digoxin.1 The lack of significant reduction in HF death in the NYHA class III–IV subgroup may be explained by the preferential effect of digoxin on HF death. As HF advances, death due to pump failure becomes more common than sudden cardiac death.21,22 Unlike CTR >55% and LVEF <25%, which may indicate biologically advanced HF, NYHA class III–IV symptoms may occur in both early and advanced stage HF. Fewer HF deaths in NYHA class III–IV patients may explain a weaker effect of digoxin in these patients.

Despite many advances in drug and device therapy, HF remains a leading cause of hospitalization for patients.23 Mortality and rehospitalization rates within 60–90 days of hospital discharge approach 15% and 30%, respectively.24 Yet, findings from both contemporary HF registries and RCTs suggest that digoxin is underutilized in HF.25,26 Although the lack of mortality benefit of digoxin is often cited as a reason, drugs without mortality benefit play important roles in HF care.5,27,28 Another reason for underutilization of digoxin is that DIG trial patients were not receiving beta-blockers and thus those findings may not be generalizable to contemporary HF patients receiving beta-blockers. However, most HF patients in the beta-blocker trials were receiving digoxin and it could be argued that the results from those beta-blocker trials may not be generalized to contemporary HF patients not receiving digoxin. Most patients in the early RCTs of ACE inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists did not receive beta-blockers,29,30 and yet these drugs have later been shown to improve outcomes in HF patients receiving beta-blockers.26,31 Given the magnitude of the effect of digoxin on HF hospitalization in the high-risk group observed in the current study (36% relative reduction and 10% absolute reduction; Table 3), these findings would probably be replicated in contemporary HF patients. This optimism was voiced in recent clinical research that found the effect of digoxin in the DIG trail to be similar to that of ivabradine in the Systolic Heart failure treatment with If inhibitor ivabradine Trial (SHIFT).32 Finally, digoxin is inexpensive and safe, and may also reduce HF hospitalization in HF with preserved LVEF.9,33,34

The effect of digoxin on HF death and hospitalization during the first 2 years of follow-up was similar to that observed during the entire follow-up presented in the original DIG report.1 This is remarkable considering that in the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trial enalapril had no effect on mortality after the first 2 years of follow-up, and in the Candesartan in Heart failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) trial, most of the cardiovascular death reduction occurred during the first year of follow-up.29,35 In addition to presenting baseline characteristics of the three pre-specified high-risk subgroups, the current study is also distinguished by its focus on the outcomes during the protocol-specified 2 years of follow-up which was the basis of the approval of digoxin for use in HF.6,7 The new US healthcare reform law has targeted 30-day all-cause hospital readmission as a key outcome to reduce the cost of Medicare.36 We observed that the rate of HF hospitalization was twice as high among patients in the high-risk group as in those in the low-risk group (Tables 3 and 4). Taken together with the fact that worsening HF is a key reason for hospital admission and readmission in patients with HF,37 and that the rate of HF hospitalization has not declined in the past decades,38 these findings suggest that digoxin may play a role in reducing hospital admission in high-risk HF patients.

Our study has several limitations. DIG trial participants were predominantly white men, with normal sinus rhythm, and did not receive beta-blockers or aldosterone antagonists. In addition, the high dose and high SDC target used in the DIG trial may have led to a higher SDC, thus attenuating the effect of digoxin on outcomes. Therefore, there is a need to examine the effect of low-dose digoxin on outcomes in contemporary HF patients with reduced and preserved LVEF in a well-designed RCT with substantial participation of women and minorities.

In conclusion, digoxin significantly reduces the risk of clinically important composite endpoints of mortality or hospitalizations in ambulatory chronic HF patients with NYHA class III–IV symptoms, LVEF <25%, or CTR >55%, and should be considered in these patients.

Acknowledgements

The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the DIG Investigators. This manuscript was prepared using a limited access data set obtained from the NHLBI and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the DIG Study or the NHLBI.

Conflict of interest: M.G. has been a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare AG, CorThera, Cytokinetics, DebioPharm S.A., Errekappa Terapeutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Ikaria, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi-Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Trevena Therapeutics. M.M. has received fees for participation in Steering or Executive Committees from Bayer, Corthera, Daiichi Sankyo, and Novartis, and fees for speeches from Novartis and Servier. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE, Yellen LG, Harrison MC, Jolly MK. Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure: results of the PROVED trial. PROVED Investigative Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:955–962. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90403-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, Costantini PJ, Adams KF, Cody RJ, Smith LK, Van Voorhees L, Gourley LA, Jolly MK. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. RADIANCE Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307013290101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rnnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, McDonagh T, Sechtem U, Bonet LA, Avraamides P, Ben Lamin HA, Brignole M, Coca A, Cowburn P, Dargie H, Elliott P, Flachskampf FA, Guida GF, Hardman S, Iung B, Merkely B, Mueller C, Nanas JN, Nielsen OW, Orn S, Parissis JT, Ponikowski P; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:803–869. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:e391–e479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GlaxoSmithKline LLC. LANOXIN® (digoxin) Tablets, USP. 2009 http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/archives/fdaDrugInfo.cfm?archiveid=13577 . [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Digitalis Investigation Group. Protocol: Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Digitalis on Mortality in Heart Failure. Bethesda, MD: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Digitalis Investigation Group. Rationale, design, implementation, and baseline characteristics of patients in the DIG trial: a large, simple, long-term trial to evaluate the effect of digitalis on mortality in heart failure. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:77–97. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, Zile MR, Young JB, Kitzman DW, Love TE, Aronow WS, Adams KF, Jr, Gheorghiade M. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. The FDA Announces New Prescription Drug Information Format. 2009 http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/LawsActsandRules/ucm188665.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins JF, Howell CL, Horney A Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. Determination of vital status at the end of the DIG trial. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Love TE, Lloyd-Jones DM, Aban IB, Colucci WS, Adams KF, Gheorghiade M. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the DIG trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:178–186. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed A. Digoxin and reduction in mortality and hospitalization in geriatric heart failure: importance of low doses and low serum concentrations. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:323–329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed A, Pitt B, Rahimtoola SH, Waagstein F, White M, Love TE, Braunwald E. Effects of digoxin at low serum concentrations on mortality and hospitalization in heart failure: a propensity-matched study of the DIG trial. Int J Cardiol. 2008;123:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrari A, Gregorini L, Ferrari MC, Preti L, Mancia G. Digitalis and baroreceptor reflexes in man. Circulation. 1981;63:279–285. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gheorghiade M, Hall V, Lakier JB, Goldstein S. Comparative hemodynamic and neurohormonal effects of intravenous captopril and digoxin and their combinations in patients with severe heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:134–142. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90561-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gheorghiade M, Hall VB, Jacobsen G, Alam M, Rosman H, Goldstein S. Effects of increasing maintenance dose of digoxin on left ventricular function and neurohormones in patients with chronic heart failure treated with diuretics and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Circulation. 1995;92:1801–1807. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newton GE, Tong JH, Schofield AM, Baines AD, Floras JS, Parker JD. Digoxin reduces cardiac sympathetic activity in severe congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Veldhuisen DJ. Low-dose digoxin in patients with heart failure. Less toxic and at least as effective? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:954–956. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01710-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed A, Waagstein F, Pitt B, White M, Zannad F, Young JB, Rahimtoola SH. Effectiveness of digoxin in reducing one-year mortality in chronic heart failure in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carson P, Anand I, O'Connor C, Jaski B, Steinberg J, Lwin A, Lindenfeld J, Ghali J, Barnet JH, Feldman AM, Bristow MR. Mode of death in advanced heart failure: the Comparison of Medical, Pacing, and Defibrillation Therapies in Heart Failure (COMPANION) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2329–2334. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zile MR, Gaasch WH, Anand IS, Haass M, Little WC, Miller AB, Lopez-Sendon J, Teerlink JR, White M, McMurray JJ, Komajda M, McKelvie R, Ptaszynska A, Hetzel SJ, Massie BM, Carson PE I-Preserve Investigators. Mode of death in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-Preserve) trial. Circulation. 2010;121:1393–1405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.909614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Pieper K, Sun JL, Yancy C, Young JB. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;297:61–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB OPTIMIZE-HF Investigators and Hospitals. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, Vincent J, Pocock SJ, Pitt B EMPHASIS-HS Study Group. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohn JN, Tognoni G Valsartan Heart Failure Trial Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1667–1675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, Cody R, Castaigne A, Perez A, Palensky J, Wittes J. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Held P, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet. 2003;362:772–776. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castagno D, Petrie MC, Claggett B, McMurray J. Should we SHIFT our thinking about digoxin? Observations on ivabradine and heart rate reduction in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1137–1141. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer P, White M, Mujib M, Nozza A, Love TE, Aban I, Young JB, Wehrmacher WH, Ahmed A. Digoxin and reduction of heart failure hospitalization in chronic systolic and diastolic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1681–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed A, Young JB, Gheorghiade M. The underuse of digoxin in heart failure, and approaches to appropriate use. CMAJ. 2007;176:641–643. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, Held P, McMurray JJ, Michelson EL, Olofsson B, Ostergren J, Yusuf S, Pocock S CHARM Investigators and Committee. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. Lancet. 2003;362:759–766. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone J, Hoffman GJ. Medicare Hospital Readmissions: Issues, Policy Options and PPACA. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress. Washington, DC: Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gheorghiade M, Braunwald E. Reconsidering the role for digoxin in the management of acute heart failure syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302:2146–2147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, Chen J, Vidan MT, Normand SL, Curtis JP, Drye EE, Lichtman JH, Keenan PS, Kosiborod M, Krumholz HM. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA. 2010;303:2141–2147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]