Abstract

Initial Ca2+-dependent contraction of the intestinal smooth muscle mediated by Gq-coupled receptors is attenuated by RGS4 (regulator of G-protein signalling 4). Treatment of colonic muscle cells with IL-1β (interleukin-1β) inhibits acetylcholine-stimulated initial contraction through increasing the expression of RGS4. NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) signalling is the dominant pathway activated by IL-1β. In the present study we show that RGS4 is a new target gene regulated by IL-1β/NF-κB signalling. Exposure of cultured rabbit colonic muscle cells to IL-1β induced a rapid increase in RGS4 mRNA expression, which was abolished by pretreatment with a transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D, implying a transcription-dependent mechanism. Existence of the canonical IKK2 [IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) kinase 2]/IκBα pathway of NF-κB activation induced by IL-1β in rabbit colonic muscle cells was validated with multiple approaches, including the induction of reporter luciferase activity and endogenous NF-κB-target gene expression, NF-κB-DNA binding activity, p65 nuclear translocation, IκBα degradation and the phosphorylation of IKK2 at Ser177/181 and p65 at Ser536. RGS4 up-regulation by IL-1β was blocked by selective inhibitors of IKK2, IκBα or NF-κB activation, by effective siRNA (small interfering RNA) of IKK2, and in cells expressing either the kinase-inactive IKK2 mutant (K44A) or the phosphorylation-deficient IκBα mutant (S32A/S36A). An IKK2-specific inhibitor or effective siRNA prevented IL-1β-induced inhibition of acetylcholine-stimulated PLC-β (phopsholipase C-β) activation. These results suggest that the canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway of NF-κB activation mediates the up-regulation of RGS4 expression in response to IL-1β and contributes to the inhibitory effect of IL-1β on acetylcholine-stimulated PLC-β-dependent initial contraction in rabbit colonic smooth muscle.

Keywords: interleukin-1β (IL-1β), intestinal smooth muscle, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), phospholipase C, regulator of G-protein signaling 4 (RGS4), small interfering RNA

INTRODUCTION

In gastrointestinal smooth muscle, ACh (acetylcholine) induces contraction via muscarinic M3 receptors coupled to Gαq protein [1]. The strength and duration of Gα signalling is regulated by a large family of multifunctional signalling proteins known as RGS (regulators of G-protein signalling). RGS4 is one of the best-studied RGS proteins and plays an important role in regulating smooth muscle contraction, cardiomyocyte development, neural plasticity and psychiatric disorders [2,3]. Our previous studies in gut smooth muscle have shown that RGS4 regulates Gαq signalling coupled to M3 and motilin receptors [4].

The pro-inflammatory cytokines, IL (interleukin)-1β and TNF (tumour necrosis factor)-α, are well-known to inhibit the contractile response to excitatory agonists in the gut smooth muscle cells, which might be attributed to several mechanisms. Induction of ICAM (intercellular adhesion molecule)-1 expression by TNF-α in colonic smooth muscle mediates the decrease in muscle contraction [5] and blockade of this process reverses TNF-α-induced inhibition on the muscle contractility [5]. H2O2 formed in the colonic and oesophageal sphincter smooth muscle in response to IL-1β [6,7], inhibits neurokinin-A-induced contraction by decreasing Ca2+ mobilization [8]. Our recent studies demonstrated for the first time that IL-1β inhibits ACh-induced initial contraction via increasing RGS4 expression in rabbit colonic circular muscle cells [9]. Up-regulation of RGS4 by IL-1β leads to rapid inactivation of Gαq signalling and a decrease in the ACh-induced PLC (phospholipase C)-β activity and MLC20 (myosin light chain) phosphorylation during the initial phase of contraction [1,9,10]. Up-regulation of RGS4 expression by LPS (lipopolysaccharide) [11], perhaps through IL-1β and TNF-α [12], has been reported in cardiomyocytes. However, there is no report on the mechanism of RGS4 up-regulation by these pro-inflammatory cytokines.

NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB) is a ubiquitous heterodimeric transcription factor, important in regulating numerous inducible genes involved in inflammation, immunity, cancer and neural plasticity. Three pathways for NF-κB activation have been characterized: canonical, alternative and atypical [13,14]. The canonical pathway triggered by classical stimuli such as TNF-α and IL-1β depends on the IKK [IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) kinase] signalsome, which consists of at least two catalytic subunits (IKK1 and IKK2) and a regulatory subunit (IKKγ ). The activated IKK complex phosphorylates the IκBs to induce their ubiquitination and degradation, resulting in the nuclear translocation of NF-κB dimers (mainly p65/p50) and the transcriptional regulation of specific target genes. Activation of NF-κB has been demonstrated in IBD (inflammatory bowel disease), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [15,16]. Although NF-κB activation has been shown to regulate the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells, little is known about the effects of NF-κB activation on smooth muscle contractility. NF-κB activation mediates the suppression of intestinal smooth muscle contraction by H2O2 in the dog [17] and TNFα in humans [5]. TNFα-induced inhibition in intestinal smooth muscle contraction is mediated by NF-κB-dependent activation of ICAM-1 [5,18,19].

In the present study, we identified the presence of NF-κB signalling in cultured rabbit colonic circular muscle cells, and delineated the role of the canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway of NF-κB activation in mediating the up-regulation of RGS4 by IL-1β. The results further show that IKK2 mediates the inhibitory effect of IL-1β on ACh-induced PLC-β activation and thus initial contraction in the colonic smooth muscle cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

IL-1β was obtained from Alexis Biochemicals. IKK2-IV (IKK2 inhibitor IV), MG132 (carbobenzoxy-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-leucinal Z-LLL-CHO) and APQ [NF-κB activation inhibitor, 6-amino-4-(4-phenoxyphenylethylamino)quinazoline] were from EMD Chemicals and were dissolved in DMSO. Antibodies against p65, IKK2, IκBα and β-actin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Affinity-purified RGS4 antibody was kindly provided by Dr Susanne M. Mumby (Department of Pharmacology, University of Texas Southwest Medical Center, TX, U.S.A.). Antibodies against phospho-IKK1/2, and phospho-p65 were from Cell Signalling Technology. [γ-32P]ATP was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. All other reagents were from Sigma.

Isolation and culture of smooth muscle cells

Rabbit colonic circular muscle cells were isolated and cultured as previously described [20,21].

Conventional and real-time RT (reverse transcription)–PCR

Total RNA was isolated from smooth muscle cells with TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion). A 2 μg aliquot of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with a random hexanucleotide primer. Conventional PCR was performed on the cDNA using the HotMaster™ Taq DNA polymerase kit (Eppendorf). The sequences for each pair of primers were derived from results published previously [22,23] or designed based on conserved sequences as shown in Table 1. PCR products were purified and cloned into a T-A vector for confirmation by sequencing.

Table 1. Primer sequences for conventional PCR.

Optimal conditions are temperature (in °C) × cycle number.

| Gene | Accession number | Size (bp) | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Location | Optimal conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGS4 | DQ120011 | 617 | ATGTGCAAAGGACTTGCAGGTC GTGAGAATTAGGCACACTGGG |

Exon 1 Exon 5 |

55 × 30 |

| IL-6 | AF169176 | 593 | GAATAATGAGACCTGCCTGCTGAG GCCCATTGTGCACTATTCGTTCA |

Exon 1 Exon 2 |

55 × 30 |

| COX-2 | U97696 | 282 | TCAGCCACGCAGCAAATCCT GTGATCTGGATGTCAGCACG |

Exon 1/2 Exon ¾ |

60 × 28 |

| VCAM1 | AY212510 | 469 | TTGGATGATGATTGCAGCTTCTC ACTTCCTGTCCATGTCTTCCA |

Exon 1 Exon 3 |

55 × 30 |

| MMP1 | M17821.1 | 322 | TCAGTTCGTCCTCACTCCAG TTGGTCCACCTGTCATCTTC |

Exon 2 Exon 4 |

55 × 30 |

| MMP2 | D63579.1 | 313 | AGCCTTCTCACCCCCACCTG GCCCTTATCCCACTGCCCC |

Exon 12 Exon 13 |

55 × 30 |

| MMP3 | M25664.1 | 400 | TGGCCATCTCTTCCTTCAGC GTCACTTTCTTTGCATTTGG |

Exon 7 Exon 10 |

55 × 30 |

| TIMP1 | J04712.1 | 326 | GCAACTCCGACCTTGTCATC AGCGTAGGTCTTGGTGAAGC |

Exon 1/2 Exon 4 |

60 × 28 |

| TIMP2 | Af069713 | 416 | GTAGTGATCAGGGCCAAAG TTCTCTGTGACCCAGTCCAT |

Exon 1 Exon 4 |

60 × 28 |

| TIMP3 | EF472914 | 454 | TCTGCAACTCCGACATCGTG CGGATGCAGGCGTAGTGTT |

Exon 1 Exon 5 |

60 × 28 |

| GAPDH | DQ403051 | 293 | TCACCATCTTCCAGGAGCGA CACAATGCCGAAGTGGTCGT |

Exon ? Exon ? |

55 × 22 |

Real-time PCR analysis was carried out on the ABI Prism® 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Expression of RGS4 was analysed using the TaqMan® PCR master mix reagents kit (Applied Biosystems). The TaqMan probe and primers for rabbit RGS4 (DQ120011) were designed using the Primer Express® 2.0 version and were as follows: 5′-TCCCACAGCAAGAAGGACAAA-3′ (forward, nucleotides 232–252, exon 2), 5′-TTCGGCCCATTTCTTGACTT-3′ (reverse, nucleotides 303–284, exon 3) and 5′-TTGACTCACCCTCTGG-CAAACAACCA-3′ (probe, nucleotides 254–279, across exon 2 and 3 with 321 bp of intron 2). The optimized concentrations were 0.4 μM for both primers and 0.2 μM for the probe and 5 ng of cDNA in a 20 μl reaction volume. Rabbit GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) primers (forward, 5′-CGCCTGGAGAAAGCTGCTAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGACCTGGTCCTCGGTGTAG-3′) were used as an internal control. Each sample was tested in triplicate, and the mRNA level was normalized to that of GAPDH. The real-time PCR data were analysed using ddCT relative quantification or absolute quantification with plasmid as standard calibration.

Preparation and validation of IKK2 siRNA (small interfering RNA)

Lentiviral vectors encoding EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) as an internal marker together with siRNA for IKK2 were generated as previously described [21]. Briefly, three siRNA encoding sequences (21 bp for each) were designed based on 95–100 % homology between human, mouse and rat IKK2, and targeted the nucleotides 784, 1221 and 1911 of human IKK2 (AF031416). The siRNA expression cassette was generated through two consecutive rounds of PCR, and cloned into pLL3.7 lentiviral vector via XbaI/XhoI cloning sites. The sequence of each siRNA expression cassette in the vector was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion with BamHI/EcoRI and DNA sequencing. Silencing efficiency and specificity of these siRNA constructs were determined by Western blot analysis and RT–PCR analysis in cultured colonic smooth muscle cells. The DNA sequence for the most effective IKK2 siRNA construct (IKK2A) was 5′-CCCAATAATCTTAACAGTGTC-3′ and this was therefore used for the RGS4 expression and PLC-β activation studies.

Transfection of cultured colonic muscle cells

Confluent smooth muscle cells in first passage grown on six-well plates were transiently transfected with the indicated vectors using Lipofectamine™ 2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Fluorescence analysis of EGFP or immunocytochemical staining with an anti-Tag antibody showed a transfection efficiency of 60–70 %.

EMSA (electrophoretic mobility-shift assay)

Nuclear extracts were prepared using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent kit (Pierce). Since the standard NF-κB consensus probe (Promega) did not work in rabbit smooth muscle cells in our preliminary studies, a predicted NF-κB binding site within the promoter of rabbit RGS4 was used. Synthesized sense and antisense oligonucleotides (5′-TCGA-TTTGGAAGAGGATTTTCCCAGCTT-3′) were annealed to generate a double-stranded DNA probe. The probe was labelled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega), and was added to binding reactions in the presence of poly(dI-dC):poly(dI-dC) (Sigma), herring sperm DNA (Invitrogen) and nuclear extracts. Equal amounts of extracts (10 μg) were loaded in each binding reaction. After 30 min incubation at room temperature (25 °C), samples were loaded on to a pre-electrophoresed 0.5 × TBE (Tris/borate/EDTA buffer), 6 % polyacrylamide gel and run at 150 V for approx. 1.5 h. The gels were then fixed and dried and autoradiograms obtained.

Reporter gene assay

The chemiluminescent reporter gene assay for the combined detection of luciferase and β-galactosidase activity was performed with the dual-light combined reporter gene assay system from Applied Biosystems according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Within the same experiment, each transfection was performed in triplicate and, when necessary, empty control plasmid was added to each sample to ensure each transfection received the same amount of total DNA. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase. Four separate experiments were conducted and, in each experiment, data were calculated as the average ± S.E.M. of triplicate samples.

Immunofluorescent cytochemistry

Cells were seeded on eight-well glass chamber slides (Nalge Nunc, Lab-Teck) and cultured until full confluence. After 24 h serum-starvation, cells were treated with IL-1β for different time periods followed by fixation with 4 %paraformaldehyde/PBS for 30 min. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.5 % (v/v) Triton X-100 for 30 min, blocked with 10 % normal donkey serum for 1 h and incubated with the primary anti-p65 polyclonal antibody (1:200) for 2 h. After washing, the Alexa Fluor® 488 (green)-linked secondary donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes) at a dilution of 1:200 was applied for 1 h. The staining specificity was determined by omitting the primary antibody. Hoechst 33258 was used for counterstaining of nuclei. The slides were coverslipped with anti-fading aqueous mounting medium (Biomeda). The fluorescent images were taken under the fluorescent invert microscope using NIS Elements F Version 2.10 software (Nikon).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, cells were solubilized in Triton X-100-based lysis buffer plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors (100 μg/ml PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 30 mM sodium fluoride and 3 mM sodium vanadate). After centrifugation of the lysates at 20 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, the protein concentrations of the supernatant were determined with a Dc protein assay kit from Bio-Rad. Equal amount of proteins were fractionated by SDS/PAGE, and transferred on to nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were blocked in 5 % (w/v) non-fat dried milk/TBS-T [tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6) plus 0.1 % Tween-20] for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with various primary antibodies in TBS-T plus 1 % (w/v) non-fat dried milk. After incubation for 1 h with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated corresponding secondary antibody (1:2000; 10 μg/ml, Pierce) in TBS-T plus 1 % (w/v) non-fat dried milk, immunoreactive proteins were visualized using SuperSignal Femto maximum sensitivity substrate kit (Pierce). All washing steps were performed with TBS-T.

PLC-β activity assay

PLC-β activity was determined in cultured smooth muscle cells by measuring the formation of inositol phosphates using ion-exchange chromatography as described previously [24]. Cultured smooth muscle cells, labelled with myo-[3H]inositol (0.5 μCi/ml) for 24 h in inositol-free DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) without FBS (foetal bovine serum), were washed with PBS and treated with ACh (0.1 μM) plus methoctramine (0.1 μM) for 0.5 min in 1 ml of Hepes-buffered solution (pH 7.4). The reaction was terminated by the addition of 940 μl of chloroform/methanol/HCl (50:100:1). The aqueous phase after extraction and centrifugation (1000 g for 15 min) was applied to a DOWEX AG-1 column, and [3H]inositol phosphates were eluted with 0.8 M ammonium formamate plus 0.1 M formic acid. Radioactivity was determined by liquid-scintillation counting and expressed as c.p.m. (counts per min).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

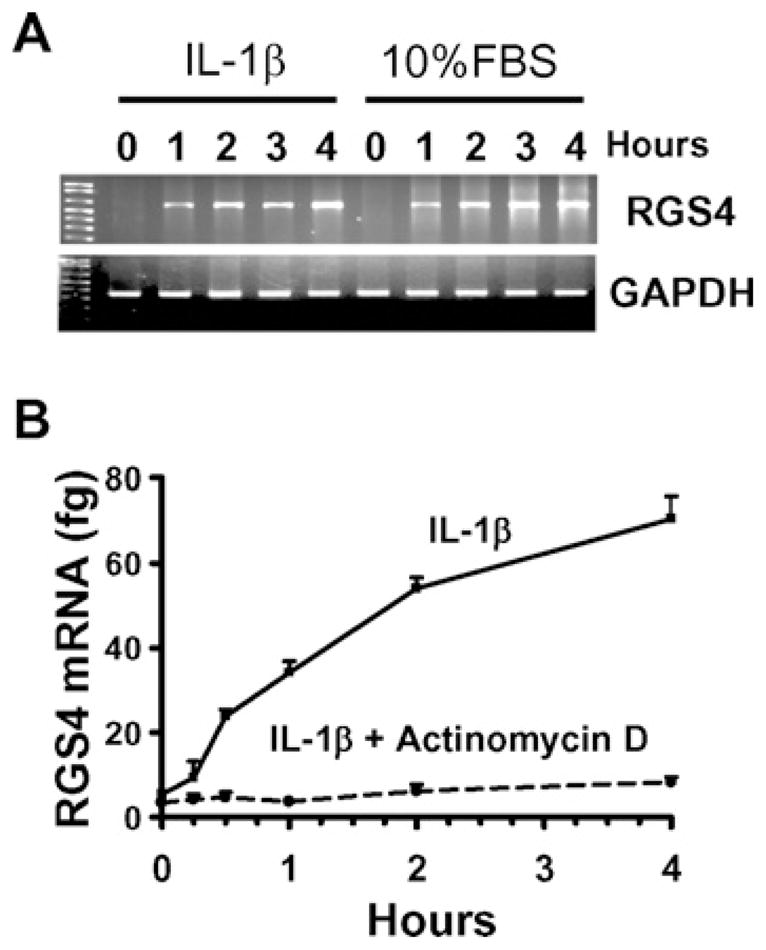

Up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA by IL-1β is transcription dependent

Although the function of RGS4 has been widely studied [2,3], the regulatory mechanism of RGS4 expression is not well understood. At the protein level, RGS4 is regulated by the N-end rule pathway [25]. At the mRNA level, RGS4 is regulated by a neural type-specific transcription factor Phox2b [26]. A recent study has identified different splice variants of RGS4 in human and murine brains [27], implying that RGS4 transcription is differentially regulated. Our previous studies have identified the up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA expression by IL-1β in rabbit colonic muscle cells [9], which reflects the increase in mRNA synthesis and/or the decrease in mRNA degradation. To determine the synthesis rate, in the present study we examined the time course of RGS4 mRNA expression using conventional and real-time RT–PCR. Treatment with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) in cultured colonic muscle cells after serum starvation for 24 h induced a rapid synthesis of RGS4 mRNA as early as 15 min and a linear increase for a few hours (Figures 1A and 1B). The expression level remained high 2–3 days after IL-1β treatment [9] (results not shown). Pretreatment with a transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (10 μM) for 1 h before IL-1β exposure completely inhibited IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA (Figure 1B). Restoration of serum also induced a rapid and increasing synthesis of RGS4 mRNA (Figure 1A). These results provide the first direct evidence that RGS4 is transcriptionally regulated by IL-1β.

Figure 1. IL-1β up-regulates RGS4 mRNA expression in a transcription-dependent manner.

Confluent colonic muscle cells were serum-starved for 24 h and pretreated without (A) or with (B) actinomycin D (10 μM) for 1 h before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) or 10 % FBS for the indicated time period. The expression level of RGS4 mRNA was determined by conventional RT–PCR (A) and real-time RT–PCR using plasmid standard calibration (B).

IL-1β activates NF-κB in colonic circular muscle cells

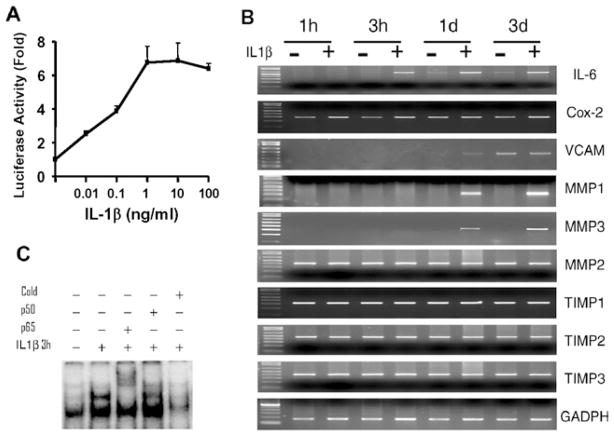

In gut inflammation, the excessive mucosal immune responses are characterized by the increased synthesis of inflammatory mediators, which activate and also depend on the signalling pathway of NF-κB in various cell types within the gut. The smooth muscle cells act as both the source and the target of these inflammatory mediators [16,28]. The presence and in particular the signalling pathway of NF-κB activation in the gut smooth muscle cells are not well understood, even though a few studies have been reported in vascular and airway smooth muscle cells [29,30]. Natarajan et al. [31] were the first to demonstrate the constitutive and inducible activation of NF-κB in human ileal smooth muscle. NF-κB activation was later reported in canine colonic circular muscle cells after acetic-acid-induced colitis or exposure to H2O2 [17]. In mouse intestinal muscle cells, LPS induces NF-κB activation via Toll-like receptor 4 [32]. In gut smooth muscle cells, IL-1β has been shown to induce NF-κB-dependent gene expression such as iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase), COX-2 (cyclo-oxygenase 2), IL-6, IL-8, etc. [28,33,34]. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on NF-κB activation and its signalling pathways in rabbit gut smooth muscle cells. Therefore we authenticated the presence of NF-κB activation in rabbit colonic muscle cells. The reporter gene assay showed a dose-dependent activation of NF-κB by IL-1β in cultured colonic muscle cells transfected with NF-κB-specific luciferase plasmid (Figure 2A). Conventional RT–PCR analysis demonstrated that IL-1β induced a time-dependent up-regulation of selective endogenous genes such as IL-6, COX-2, VCAM (vascular cell adhesion molecule) and MMP (matrix metalloproteinase)-1 and -3, which are known to be NF-κB-dependent [35] (Figure 2B). However, other NF-κB-dependent genes such as MMP-2 and TIMP (tissue inhibitor of MMP) did not show any differences after IL-1β treatment (Figure 2B), consistent with the notion that NF-κB signalling regulates gene expression in a cell-type-dependent manner. EMSA analysis measuring the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB showed that IL-1β induced the formation of an NF-κB-binding complex, which was completely shifted by pre-incubation with an anti-p65 antibody but not an anti-p50 antibody (Figure 2C). The specificity of NF-κB-binding activity was confirmed by the complete competition with the non-radioactive probe. These results suggest that IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation exists in rabbit colonic muscle cells.

Figure 2. IL-1β induces NF-κB activation in rabbit colonic muscle cells.

(A) NF-κB-luciferase reporter assay. Cells were co-transfected with NF-κB-luciferase and β-galactosidase vectors for 24 h, serum-starved for 24 h and treated with increasing concentrations of IL-1β for 24 h. The luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured with a dual-light reporter gene assay. Values are expressed as the relative fold induction compared with the control. (B) Selective NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Confluent cells after 24 h serum starvation were treated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods, and the mRNA expression levels of selected genes as indicated were detected by conventional RT–PCR. TIMP, tissue inhibitor of MMP; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule. (C) NF-κB-DNA binding activity. Serum-starved cells were treated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h and nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA. The binding complex was supershifted with an anti-p65 antibody (lane 3).

The canonical IKK2/IκBα/p65 pathway mediates NF-κB activation in colonic smooth muscle cells

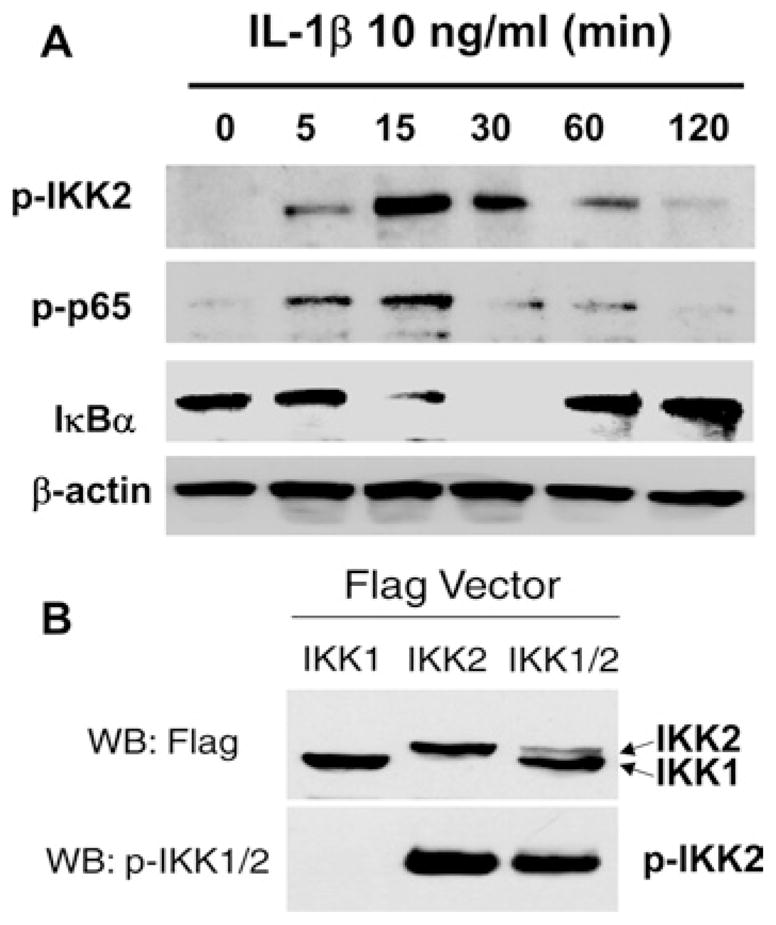

Although it is well established that IL-1β activates NF-κB through the canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway in many cell types such as lymphocytes [36] and neurons [37], the role of this canonical pathway in smooth muscle cells remains uncertain. Recent studies have demonstrated that the IKK2/IκBα pathway stimulated by TNF-α or angiotensin II is present in vascular and airway smooth muscle cells [30,38]. However, Douillette et al [39] reported that angiotensin II does not affect the canonical pathway leading to IκBα phosphorylation and degradation in vascular smooth muscle cells [39]. Much convincing evidence in the present study shows that IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation in colonic muscle cells involves the canonical IKK2/IκBα/p65 pathway. As shown in Figure 3(A), IL-1β induced rapid phosphorylation of IKK2 at Ser177/181, accompanied by degradation of IκBα and phosphorylation of p65 at Ser536. The phosphorylated band of IKK2 recognized by an anti-phosphoIKK1/2 antibody was confirmed through detecting the fusion proteins of Flag-tagged IKK1 or IKK2 (Figure 3B). Consistent with previous reports in other cell types [40,41], overexpression of IKK2, not IKK1, led to corresponding auto-phosphorylation in smooth muscle cells while co-expression of IKK1 inhibited IKK2 auto-phosphorylation (Figure 3B). However, co-expression of IKK2 did not induce the phosphorylation of IKK1 in rabbit colonic muscle cells, contradicting previous reports [40,41]. The mechanism and biological significance of the lack of IKK1 phosphorylation in the smooth muscle cells remain to be determined. A previous study has demonstrated that H2O2 activates IKK1 but not IKK2 in canine colonic muscle cells [17]. Therefore the phosphorylation of the IKK subunit is cell-specific and stimulus-dependent.

Figure 3. IL-1β induces phosphorylation of IKK2 and p65 and degradation of IκBα.

(A) Western blot analysis. Serum-starved cells were treated with or without IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time period and Western blot analysis was performed using specific antibodies. (B) Validation of IKK2 phosphorylation. Cells were transfected with the indicated vectors for 24 h followed by Western blot analysis. p-IKK2, phosphorylated IKK2; p-p65, phosphorylated p65 subunit; WB, Western blot.

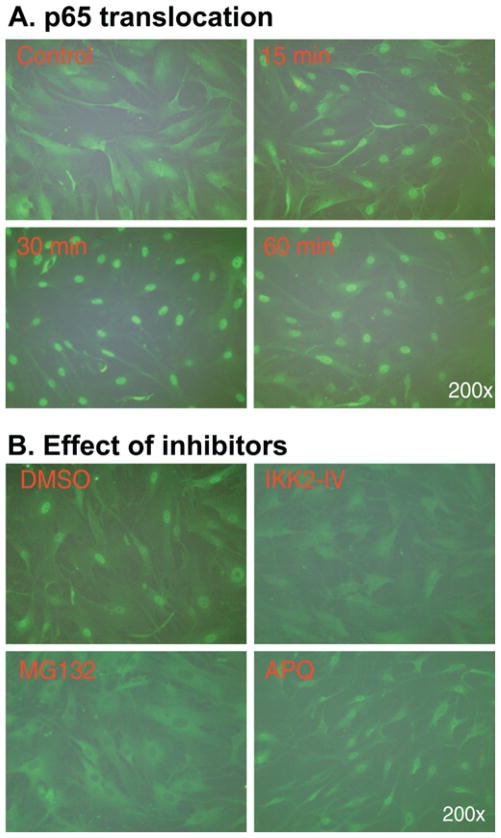

Cytokine-induced nuclear translocation of p65 is well known in different cell types, including smooth muscle cells [29]. Nuclear translocation of p65, p50 and c-rel induced by H2O2 has been reported in canine colonic muscle cells [17]. LPS-induced nuclear translocation of p65 is shown in the muscle layer of mouse intestine [32]. In the present study we provide clear evidence that IL-1β induces rapid nuclear translocation of p65, as detected by immunofluorescent staining with an anti-p65 antibody in cultured rabbit colonic muscle cells (Figure 4A). To further determine whether the IKK2/IκBα pathway mediates p65 nuclear translocation, the serum-starved smooth muscle cells were pretreated with either IKK2-IV or the proteasome inhibitor MG132 which has been widely used to inhibit IκBα degradation resulting in blockade of NF-κB activation. As shown in Figure 4(B), the nuclear translocation of p65 was completely blocked by pretreatment with either IKK2-IV or MG132. However, the cell-permeable quinazoline compound APQ that acts as a potent inhibitor of NF-κB transcriptional activation, downstream of p65 nuclear translocation, did not prevent IL-1β-induced nuclear translocation of p65 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. IL-1β induces nuclear translocation of p65 via IKK2 and IκBα.

(A) IL-1β induces nuclear translocation of p65. Serum-starved cells were treated with IL-1β and immunofluorescent staining was performed with an anti-p65 antibody. (B) Blockade of the canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway abolishes IL-1β-induced p65 translocation. Cells were pretreated for 1 h with IKK2-IV (10 μM), MG132 (10 μM) and APQ (10 μM) before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 30 min, and immunofluorescent staining was performed.

NF-κB signalling mediates IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 expression

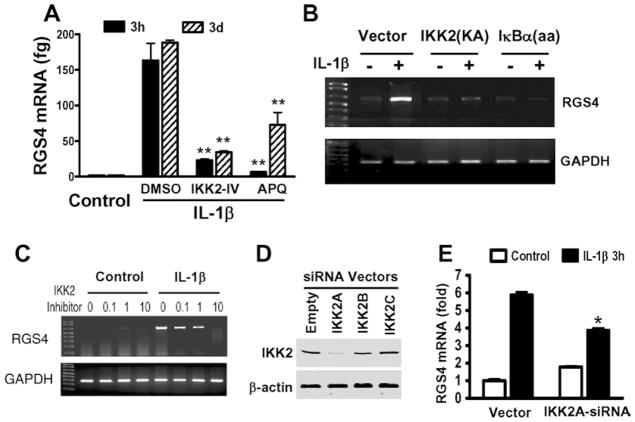

IL-1β up-regulates RGS4 mRNA predominantly via a transcription-dependent mechanism, and activates the canonical NF-κB pathway in smooth muscle cells as demonstrated above. Therefore we tested the hypothesis that NF-κB-dependent transcriptional regulation may mediate IL-1β-stimulated induction of RGS4 mRNA expression. As shown in Figure 5(A), pretreatment with the specific NF-κB activation inhibitor, APQ, significantly blocked the IL-1β-induced increase in RGS4 mRNA expression at 3 h and 3 days after IL-1β exposure. Thus NF-κB activation mediates up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA expression by IL-1β in rabbit colonic muscle cells.

Figure 5. IL-1β-induced NF-κB activation mediates RGS4 mRNA up-regulation.

(A) Blockade of NF-κB activation and IKK2 inhibit IL-1β-induced RGS4 expression. Serum-starved cells were pretreated with DMSO, IKK2-IV (10 μM) or APQ (10 μM) for 1 h before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h or 3 days. The expression level of RGS4 mRNA was quantified by real-time RT–PCR using plasmid standard calibration. **P < 0.01, indicates a significant decrease by selective inhibitors compared with DMSO. (B) The mutants of IKK2 and IκBα block IL-1β-induced RGS4 expression. Cells were transfected with indicated mutants for 24 h and serum-starved for 24 h before exposure to IL-1β for 3 h. The expression level of RGS4 and GAPDH mRNA was determined by conventional RT–PCR. IKK2(KA), IKK2 mutant (K44A); IκBα(aa), IκBα mutant (S32A/S36A). (C) An IKK2 inhibitor suppresses IL-1β-induced RGS4 expression in a dose-dependent manner. Serum-starved cells were pretreated with indicated concentrations of IKK2-IV (μM) for 1 h before exposure to IL-1β for 3 days. The expression level of RGS4 and GAPDH mRNA was determined by conventional RT–PCR. (D) Efficiency of the vector-based IKK2 siRNA. Cultured cells were transfected with the indicated siRNA vectors for 3 days and the expression level of IKK2 was determined by Western blot analysis with an anti-IKK2 antibody. The β-actin was used as loading control. (E) Effective IKK2A siRNA inhibits IL-1β-induced RGS4 expression. Cells were transfected with IKK2A siRNA or empty vector for 2 days and serum-starved for 24 h before exposure to IL-1β for 3 h. The expression level of RGS4 mRNA was determined by real-time RT–PCR. Results are expressed as the fold induction compared with the control after GAPDH normalization. *P < 0.05, indicates a significant decrease by IKK2A siRNA compared with the corresponding empty vector.

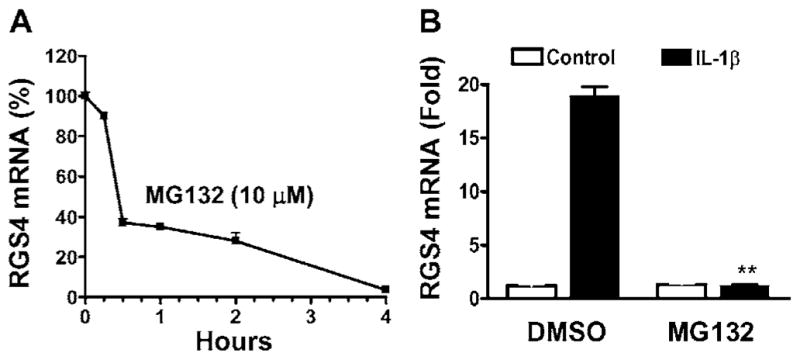

To determine the role of the canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway in mediating IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 expression, we transfected colonic muscle cells with a kinase-inactive IKK2 mutant IKK2(K44A) or a phosphorylation-deficient IκBα mutant IκBα(S32A/S36A) before IL-1β treatment. As shown in Figure 5(B), overexpression of IKK2(K44A) attenuated IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA expression, whereas overexpression of IκBα(S32A/S36A) abolished IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA expression. To examine the role of endogenous IKK2 in mediating IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 expression, we pre-treated the colonic muscle cells with IKK2-IV or transfected the cells with IKK2 siRNA expression vector. IKK2-IV pretreatment for 1 h before IL-1β exposure inhibited IL-1β-induced RGS4 expression in a dose-dependent manner, with an over 90 %reduction at 10 μM, whereas IKK2-IV alone had no effect (Figure 5C). Real-time RT–PCR showed an 80–90 % reduction in RGS4 mRNA by IKK2-IV at 10 μM (Figure 5A). Silencing of the endogenous IKK2 by the specific and effective IKK2A siRNA (Figure 5D) significantly attenuated IL-1β-induced RGS4 mRNA expression (Figure 5E). To address whether the endogenous IκBα mediates IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA expression, we treated the serum-starved smooth muscle cells with MG132. MG132 treatment alone caused a rapid decrease in the ‘constitutive’ level of RGS4 mRNA expression as determined by real-time RT–PCR (Figure 6A). Pretreatment with MG132 for 1 h before IL-1β exposure for 3 h abolished IL-1β-induced RGS4 mRNA expression (Figure 6B). These results suggest that IL-1β up-regulates RGS4 mRNA expression through a canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway of NF-κB activation.

Figure 6. MG132 inhibits the constitutive and inducible expression of RGS4 mRNA.

Serum-starved cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for different time periods (A), or for 1 h (B) before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h. The expression level of RGS4 mRNA was quantified by real-time RT–PCR. The relative expression level is presented as compared with the control after GAPDH normalization. **P < 0.01, indicates a significant decrease by MG132 compared with DMSO.

The mechanism for the time-dependent decrease in the basal expression of RGS4 mRNA by MG132 treatment in serum-starved colonic muscle cells remains to be determined. It may suggest that proteasome-mediated degradation of IκBα or other signalling components maintains the constitutive activation of those signalling pathways that facilitate the transcription or mRNA stabilization of RGS4. All the known signalling pathways of NF-κB activation involve proteasome-mediated degradation or cleavage of the family of IκB proteins [14,42]. The fact that MG132 abolished IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA expression indicates that the signalling pathways in addition to the degradation of IκBα stimulated by IL-1β are involved in RGS4 mRNA regulation.

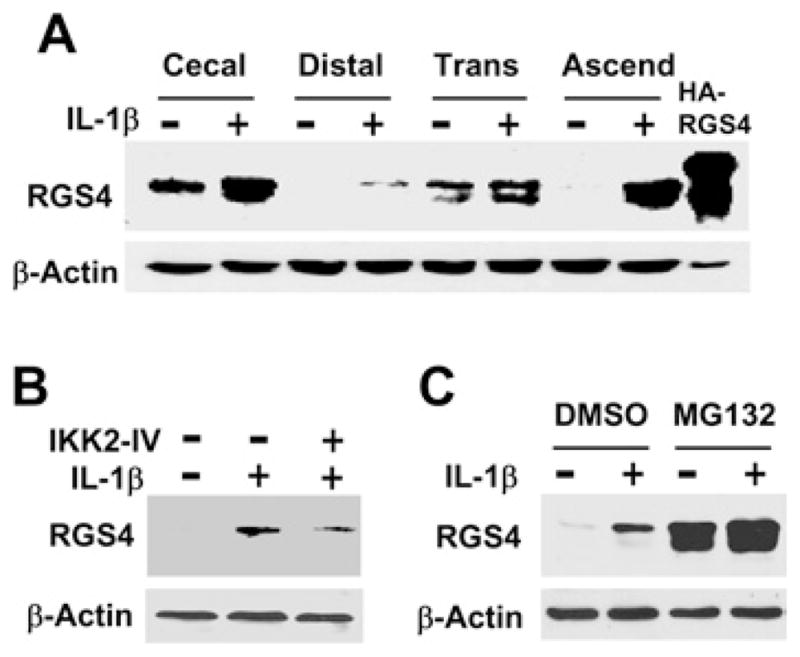

IKK2 mediates IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 protein expression

Up-regulated mRNA of RGS4 leads to the production of RGS4 protein. As demonstrated previously, IL-1β induced a time-dependent up-regulation of RGS4 protein expression in cultured circular muscle cells of the rabbit distal colon [9]. We also compared the protein expression level of RGS4 in cultured circular muscle cells from the distal, transversal, ascending and cecal colon. As shown in Figure 7(A), constitutive expression of RGS4 protein was present in the serum-starved smooth muscle cells from the cecal and transversal colon. IL-1β treatment for 3 h increased RGS4 protein expression in all of the regions tested. The specificity of the anti-RGS4 antibody was verified using overexpressed HA (haemagglutinin)-tagged RGS4, consistent with the previous reports [43]. As predicted, inhibition of NF-κB signalling with IKK2-IV prevented IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 protein expression in colonic muscle cells (Figure 7B), suggesting that IKK2 mediates IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 protein. Surprisingly, in contrast with the inhibition of RGS4 constitutive expression at the mRNA level (Figure 6), MG132 treatment increased the constitutive level of RGS4 protein (Figure 7C). In addition, MG132 treatment did not prevent IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 protein expression. These results suggest that proteasome-mediated signalling pathways in addition to the IκBα degradation regulate RGS4 protein expression [25]. The opposite effect of proteasome signalling on RGS4 mRNA and protein expression implies a complex mechanism for RGS4 regulation. This also suggests that more specific inhibitors for NF-κB signalling should be developed and utilized in clinical trials.

Figure 7. IL-1β up-regulates RGS4 protein expression through the IKK2 pathway.

(A) IL-1β increases RGS4 protein expression in colonic muscle cells. Smooth muscle cells cultured from the indicated region of the rabbit colon were serum-starved for 24 h followed by exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h. Whole cell extracts were subject to Western blot analysis with an anti-RGS4 or anti-β-actin antibody. Cells transfected with HA–RGS4 vector were used as positive control. (B) The IKK2 inhibitor IKK2-IV prevents IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 protein. Serum-starved cells were pretreated with IKK2-IV (10 μM) for 1 h before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h. The expression level of RGS4 protein was determined with Western blot analysis. (C) MG132 increases constitutive and inducible expression of the RGS4 protein. Serum-starved cells were pretreated with MG132 (10 μM) for 1 h before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h. The expression level of RGS4 protein was determined with Western blot analysis.

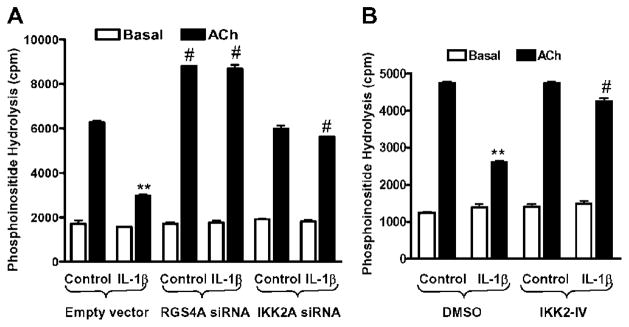

IKK2 mediates IL-1β-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation during the initial phase of contraction

RGS4 functions by inactivating Gαq signalling of various receptors and attenuating agonist-induced PLC-β activation and initial contraction in gut smooth muscle cells [1,4,44]. We have previously demonstrated that silencing of endogenous RGS4 expression by the effective RGS4A siRNA in rabbit colonic muscle strips and cultured muscle cells prevents the IL-1β-induced inhibitory effect on ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation and initial contraction [9]. This provides a direct link between up-regulation of RGS4 expression and inhibition of initial muscle contraction induced by IL-1β. To explore further the biological significance of the IKK2-mediated NF-κB signalling pathway in regulating the signalling targets during the initial phase of agonist-induced contraction, we selected PLC-β activity as a marker to reflect the initial contractile response of smooth muscle cells [24,44]. In agreement with our previous study [9], treatment with IL-1β for 3 h inhibited ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation whereas silencing of RGS4 by the effective RGS4A siRNA increased ACh-stimulated PLC-β activity and blocked IL-1β-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation (Figure 8A). Silencing of IKK2 by the effective IKK2A siRNA did not affect ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation but prevented IL-1β-induced inhibition (Figure 8A). Similarly, inhibition of the endogenous IKK2 by specific inhibitor IKK2-IV (10 μM), which inhibited IL-1β-induced up-regulation of RGS4 expression (Figure 6), prevented IL-1β-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation (Figure 8B). Taken together, these results suggest that the IKK2-mediated pathway of NF-κB activation contributes to the inhibitory effect of IL-1β on ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation during the initial phase of contraction in rabbit colonic muscle cells. This conclusion is supported by the previous report that blockade of NF-κB activation reverses inflammation-induced suppression in colonic muscle motility [17]. In addition to RGS4, many other signalling components mediating smooth muscle contraction may be regulated by NF-κB. Inhibition of NF-κB signalling, in particular at the level of IKK2, has been targeted for use in the pharmaceutical industry [42] and also has been shown to be effective in treating IBD-related colitis [16,45].

Figure 8. IKK2 mediates IL-1β-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation in rabbit colonic muscle cells.

(A) Silencing of either RGS4 or IKK2 by vector-based siRNA prevents IL-1β-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation. Cultured cells were transfected with empty vector or effective siRNA for RGS4 or IKK2 for 2 days, and then labelled with myo-[3H]inositol in serum-free medium for 1 day, pretreated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h and stimulated with ACh (0.1 μM) plus methoctramine (0.1 μM) for 0.5 min. [3H]Inositol phosphate was determined as described in the Materials and methods section and is expressed as cpm. Values are means ± S.E.M. of three experiments. **P < 0.01, indicates a significant decrease by IL-1β in ACh-induced PLC-β activity compared with control. #P < 0.05, indicates a significant increase in ACh-induced PLC-β activity compared with the corresponding empty siRNA vector. (B) The IKK2 inhibitor IKK2-IV blocks IL-1β-induced inhibition of ACh-stimulated PLC-β activation. Cultured cells were labelled with myo-[3H]inositol in serum-free medium for 1 day, pretreated with IKK2-IV (10 μM) for 1 h before exposure to IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for 3 h and stimulated with ACh (0.1 μM) plus methoctramine (0.1 μM) for 0.5 min. PLC-β activity was measured and statistically analysed as above.

In conclusion, the present study provides the first evidence that IL-1β up-regulates RGS4 expression through a canonical IKK2/IκBα pathway of NF-κB activation in colonic muscle cells. Other signalling pathways activated by IL-1β, such as MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinases) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt/GSK3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3β) that could influence directly or indirectly the activation of NF-κB and the expression of RGS4 in smooth muscle cells, remain under investigation. Increased RGS4 expression by IL-1β contributes to the deactivation of Gαq signalling and inhibition of initial muscle contraction during inflammatory responses of the gut. Intervention of NF-κB signalling to balance the expression and function of RGS4 and other signalling molecules in the contractile pathway may provide a potential target for therapeutic development in IBD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant DK075964 and DK015564 from the National Institutes of Diabetes, and Kidney and Digestive Diseases.

Abbreviations used

- ACh

acetylcholine

- APQ

6-amino-4-(4-phenoxyphenylethylamino)quinazoline

- COX-2

cyclo-oxygenase 2

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility-shift assay

- FBS

foetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HA

haemagglutinin

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule

- IκB

inhibitor of nuclear factor κB

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IKK2-IV

IKK2 inhibitor IV

- IL

interleukin

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MG132

carbobenzoxy-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-leucinal Z-LLL-CHO

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- PLC

phospholipase C

- RGS

regulator of G-protein signalling

- RT

reverse transcription

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor α

References

- 1.Murthy KS. Signaling for contraction and relaxation in smooth muscle of the gut. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:345–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie GX, Palmer PP. How regulators of G protein signaling achieve selective regulation. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levitt P, Ebert P, Mirnics K, Nimgaonkar VL, Lewis DA. Making the case for a candidate vulnerability gene in schizophrenia: convergent evidence for regulator of G-protein signaling 4 (RGS4) Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:534–537. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J, Zhou H, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Murthy KS. Inhibition of Gαq-dependent PLC-β1 activity by PKG and PKA is mediated by phosphorylation of RGS4 and GRK2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C200–C208. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00103.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pazdrak K, Shi XZ, Sarna SK. TNFα suppresses human colonic circular smooth muscle cell contractility by SP1- and NF-κB-mediated induction of ICAM-1. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1096–1109. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao W, Harnett KM, Cheng L, Kirber MT, Behar J, Biancani P. H2O2: a mediator of esophagitis-induced damage to calcium-release mechanisms in cat lower esophageal sphincter. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1170–G1178. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00509.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao W, Vrees MD, Potenti FM, Harnett KM, Fiocchi C, Pricolo VE. Interleukin 1β-induced production of H2O2 contributes to reduced sigmoid colonic circular smooth muscle contractility in ulcerative colitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:60–70. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao W, Cheng L, Behar J, Biancani P, Harnett KM. IL-1β signaling in cat lower esophageal sphincter circular muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G672–G680. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00110.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu W, Mahavadi S, Li F, Murthy KS. Upregulation of RGS4 and downregulation of CPI-17 mediate inhibition of colonic muscle contraction by interleukin-1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1991–C2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00300.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang WC, Ju TK, Hung MC, Chen CC. Phosphorylation of CBP by IKKα promotes cell growth by switching the binding preference of CBP from p53 to NF-κB. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patten M, Bunemann J, Thoma B, Kramer E, Thoenes M, Stube S, Mittmann C, Wieland T. Endotoxin induces desensitization of cardiac endothelin-1 receptor signaling by increased expression of RGS4 and RGS16. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:156–164. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patten M, Stube S, Thoma B, Wieland T. Interleukin-1β mediates endotoxin- and tumor necrosis factor α-induced RGS16 protein expression in cultured cardiac myocytes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;368:360–365. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-κB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escarcega RO, Fuentes-Alexandro S, Garcia-Carrasco M, Gatica A, Zamora A. The transcription factor nuclear factor-κB and cancer. Clin Oncol. 2007;19:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber S, Nikolaus S, Hampe J. Activation of nuclear factor κB inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1998;42:477–484. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura K, Honda K, Mizutani T, Akiho H, Harada N. Novel strategies for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: selective inhibition of cytokines and adhesion molecules. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4628–4635. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi XZ, Lindholm PF, Sarna SK. NF-κB activation by oxidative stress and inflammation suppresses contractility in colonic circular smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi XZ, Pazdrak K, Saada N, Dai B, Palade P, Sarna SK. Negative transcriptional regulation of human colonic smooth muscle Cav1.2 channels by p50 and p65 subunits of nuclear factor-κB. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1518–1532. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi XZ, Sarna SK. Transcriptional regulation of inflammatory mediators secreted by human colonic circular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G274–G284. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00512.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM. Differential coupling of muscarinic m2 and m3 receptors to adenylyl cyclases V/VI in smooth muscle. Concurrent M2-mediated inhibition via Gαi3 and m3-mediated stimulation via Gbetagammaq. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21317–21324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu W, Huang J, Mahavadi S, Li F, Murthy KS. Lentiviral siRNA silencing of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors S1P1 and S1P2 in smooth muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:1038–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi A, Tojyo I, Yoshida H, Fujita S. Role of hypoxia and interleukin-1β in gene expressions of matrix metalloproteinases in temporomandibular joint disc cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reno C, Boykiw R, Martinez ML, Hart DA. Temporal alterations in mRNA levels for proteinases and inhibitors and their potential regulators in the healing medial collateral ligament. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:757–763. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM. Opioid μ, δ, and κ receptor-induced activation of phospholipase C-β3 and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase is mediated by Gi2 and G(o) in smooth muscle. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:870–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodenstein J, Sunahara RK, Neubig RR. N-terminal residues control proteasomal degradation of RGS2, RGS4, and RGS5 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1040–1050. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grillet N, Dubreuil V, Dufour HD, Brunet JF. Dynamic expression of RGS4 in the developing nervous system and regulation by the neural type-specific transcription factor Phox2b. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10613–10621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding L, Mychaleckyj JC, Hegde AN. Full length cloning and expression analysis of splice variants of regulator of G-protein signaling RGS4 in human and murine brain. Gene. 2007;401:46–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salinthone S, Singer CA, Gerthoffer WT. Inflammatory gene expression by human colonic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G627–G637. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00462.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreau ME, Bawolak MT, Morissette G, Adam A, Marceau F. Role of nuclear factor-κB and protein kinase C signaling in the expression of the kinin B1 receptor in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:949–956. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang KC, Lee CW, Lin WN, Lin CC, Wu CB, Luo SF, Yang CM. Interleukin-1β induces MMP-9 expression via p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK, and nuclear factor-κB signaling pathways in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:759–770. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Natarajan R, Ghosh S, Fisher BJ, Diegelmann RF, Willey A, Walsh S, Graham MF, Fowler AA., 3rd Redox imbalance in Crohn’s disease intestinal smooth muscle cells causes NF-κB-mediated spontaneous interleukin-8 secretion. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:349–359. doi: 10.1089/107999001750277826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rumio C, Besusso D, Arnaboldi F, Palazzo M, Selleri S, Gariboldi S, Akira S, Uematsu S, Bignami P, Ceriani V, et al. Activation of smooth muscle and myenteric plexus cells of jejunum via Toll-like receptor 4. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:47–54. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan I, Blennerhassett MG, Kataeva GV, Collins SM. Interleukin 1β induces the expression of interleukin 6 in rat intestinal smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1720–1728. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuemmerle JF. Synergistic regulation of NOS II expression by IL-1β and TNF-α in cultured rat colonic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G178–G185. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perkins ND, Gilmore TD. Good cop, bad cop: the different faces of NF-κB. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:759–772. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayden MS, West AP, Ghosh S. NF-κB and the immune response. Oncogene. 2006;25:6758–6780. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Memet S. NF-κB functions in the nervous system: from development to disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1180–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKenzie CJ, Ritchie E, Paul A, Plevin R. IKKα and IKKβ function in TNFα-stimulated adhesion molecule expression in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Cell Signalling. 2007;19:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douillette A, Bibeau-Poirier A, Gravel SP, Clement JF, Chenard V, Moreau P, Servant MJ. The proinflammatory actions of angiotensin II are dependent on p65 phosphorylation by the IκB kinase complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13275–13284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, Karin M. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science. 1999;284:309–313. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu WH, Pendergast JS, Mo XM, Brambilla R, Bracchi-Ricard V, Li F, Walters WM, Blits B, He L, Schaal SM, Bethea JR. NIBP, a novel NIK and IKKβ-binding protein that enhances NF-κB activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29233–29241. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080042. Received 8 January 2008/4 February 2008; accepted 8 February 2008 Published as BJ Immediate Publication 8 February 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strnad J, Burke JR. IκB kinase inhibitors for treating autoimmune and inflammatory disorders: potential and challenges. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krumins AM, Barker SA, Huang C, Sunahara RK, Yu K, Wilkie TM, Gold SJ, Mumby SM. Differentially regulated expression of endogenous RGS4 and RGS7. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2593–2599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J, Zhou H, Mahavadi S, Sriwai W, Lyall V, Murthy KS. Signaling pathways mediating gastrointestinal smooth muscle contraction and MLC20 phosphorylation by motilin receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G23–G31. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00305.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shibata W, Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Yanai A, Ohmae T, Sakamoto K, Nakagawa H, Ogura K, Omata M. Cutting edge: the IκB kinase (IKK) inhibitor, NEMO-binding domain peptide, blocks inflammatory injury in murine colitis. J Immunol. 2007;179:2681–2685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]