Abstract

This supplement highlights the efforts of Morehouse School of Medicine’s Prevention Research Center and its partners to reduce the disparities experienced by African American women for breast and cervical cancer in Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina. The project (entitled the Southeastern U.S. Collaborative CEED, or SUCCEED) is supported by a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant to establish a Center of Excellence in the Elimination of Disparities (CEED). This introductory paper provides an overview describing the project’s goals and core components and closes by introducing the adjoining papers that describe in more detail these components. The program components for SUCCEED include providing training and technical assistance for implementing evidence-based interventions for breast and cervical cancer; supporting capacity-building and sustainability efforts for community-based organizations; promoting the establishment of new empowered community coalitions and providing advocacy training to cancer advocates in order to affect health systems and policies.

Keywords: African American women, breast and cervical cancer, cancer control, cancer, disparities

In 2007, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the REACH US Program (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health across the United States). CDC funded 22 Action Communities and 18 Centers of Excellence in the Elimination of Disparities (CEEDs). The former are local projects, while the latter are regional projects intended not only to provide services within the region but to provide technical assistance to other projects throughout the country on topics such as program implementation and evaluation, staff development and training, the creation of community action plans, capacity building, and disseminating evidence-based approaches to prevention. Both types of project are housed within community-based organizations, institutions of higher education, county health departments, tribal councils, hospitals, or community clinics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

REACH U.S. centers of excellence for the elimination of health disparities multi-state/regional sites.

The health priority areas that are the foci of REACH US include breast and cervical cancer, asthma, infant mortality, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hepatitis, immunizations, and tuberculosis. Each grantee addresses one of these health issues as it affects one of five racial/ethnic groups: African Americans, Latinos/Hispanics, Asian Americans, Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians and Alaskan Natives

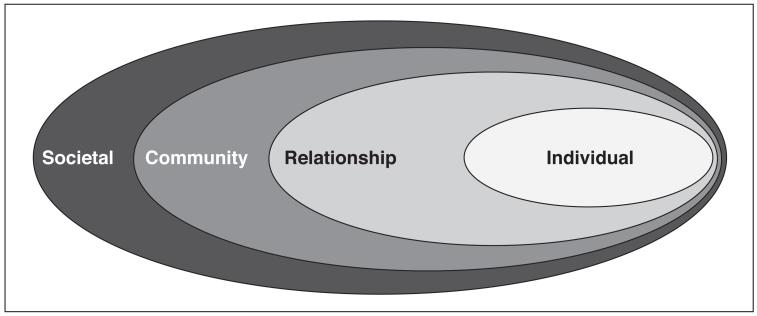

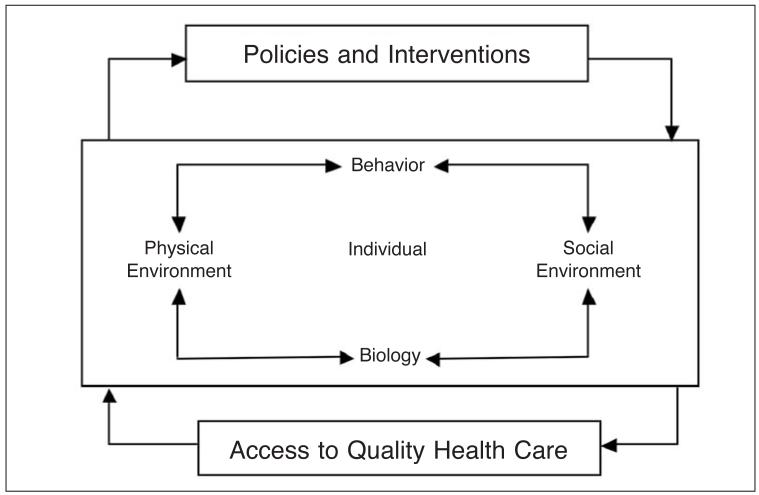

REACH US is the CDC’s signature effort for the reduction and elimination of health disparities affecting ethnic and racial minorities in the United States. The emphasis of the program is on the social-ecological model of health, which incorporates the social determinants of human health (see Figure 2). The social-ecological model recognizes that health is contextually and reciprocally influenced by the social ecology. Similarly, within various contexts are social determinants—e.g., health care access, poverty, social class, education, racism, and sexism—that influence how these systems operate and ultimately affect the health of the citizenry and in this instance African American women. For example, health is not only influenced by individual choices but also by access to health care, quality foods within the community, and health policy at a societal level.

Figure 2.

Social-ecological model: a framework for prevention.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Injury center: violence prevention. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/overview/social-ecological model.html.

REACH US is a second generation effort of this program, preceded by REACH 2010. REACH 2010 focused on prophylactic and health education interventions whereas REACH US focuses on influencing social determinants and systems and policy changes in ways that promote positive health outcomes.

The Morehouse School of Medicine Prevention Research Center (MSM PRC) was funded as a CEED by the CDC’s REACH US program. The program at MSM is entitled the Southeastern US Collaborative CEED or SUCCEED; it serves the three-state region of Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. In this introduction, we provide an overview of each of the components of SUCCEED as well as briefly introduce each of the other papers in the supplement. The goal of SUCCEED is to create a regional center that will function as a model and a national leader in the elimination of disparities in breast and cervical cancer incidence and mortality among African American women.

The primary SUCCEED partners in this endeavor are the Fulton County Department of Health and Wellness (the local health department serving most of Atlanta and some of its suburbs), the Emory University Prevention Research Center, the Medical University of South Carolina’s Hollings Cancer Center, and the Comprehensive Cancer Control Collaborative of North Carolina (4CNC), a program of the University of North Carolina PRC. The intent of SUCCEED, through these partnerships and in collaboration with a host of local partners, was to create a regional infrastructure of academic and community partners committed to reducing breast and cervical cancer disparities.

In addition to building a regional infrastructure, the specific objectives of the program call for SUCCEED to provide training and technical assistance to agencies and organizations throughout the region in evidence-based approaches to increase breast and cervical cancer screening among African American women. Additional training and technical assistance to these entities promotes capacity-building and sustainability for evidence-based programs, program implementation, and assisting with evaluation and grant-seeking. SUCCEED also emphasizes the development of community coalitions, using the Community Organization and Development for Health Promotion model, a community partnership framework pioneered over 20 years ago at MSM.1

A final objective includes efforts to promote health systems and policy changes that support and encourage screening for breast and cervical cancer, particularly for low-income women. In pursuit of this objective, SUCCEED provides training in public policy advocacy for community organizations and concerned citizens. This last objective is critical; one of the social determinants informing the disparities that African American women experience for breast and cervical cancer is access to screening services. This determinant is largely influencing by the capacity of the public health system to respond to the screening needs among these and other underserved women.

First, however, a brief overview of the burden of breast and cervical cancer incidence and mortality experienced by African American in this region is required. The incidence and mortality rates reported here reflect the available data when we began our program in 2007 as well as the most recent data available as this paper was prepared.

As these tables show, mortality rates are coming down generally for African American women across the tri-state region although the magnitude of the disparity between racial/ethnic groups has not decreased. Problematic is that disparities continue to exist at all for African American women as the impact of these cancer sites continues to decline for all women.2,3 A number of social determinants influence these disparities although significant here is differential access to high-quality health care (e.g., screening). Other social determinants operating more specifically on African American women in the tri-state region are socio-economic status, racism, inequities in neighborhood environments, as well as limited educational and employment opportunities.2-4 These are examples of factors operating in the social-ecological framework that guides SUCCEED’s efforts and describes conceptually and operationally how these determinants work and the reciprocal influence they have on each other.

The Social-Ecological Model, Social determinants of Health, and the community organization and development for Health Promotion Model

The social-ecological model is built on the notion that health status is affected by many factors other than medical care—that, in fact, medical care may be the least important factor. “Social determinants of health” is the term that has been given to such other factors as social class, socioeconomic status, sexism, racism, and education; community factors such as employment and adequate housing; and relationship factors such as family and social support systems.5

Addressing social determinants may present a challenge to the health care professional, since the default approach has typically been to strive to provide more medical care and many of these determinants are socially embedded and do not respond to the care provided in a physician’s office. The Community Organization and Development for Health Promotion (CODHP) model offers an alternative—organizing a community around a health or medical issue in order to create a lever for other issues. Hence, a group of concerned citizens may work together to increase access to screening for breast and cervical cancer, and may go on to take action on matters of education, transportation, or any other issue affecting their community.

In low-income communities, organizing by principles such as those described in the CODHP model has the potential to change the power relationships that are an important component of social determinants of health.6 Poor people rarely have the opportunity to control the services that affect their lives. So, for instance, breast and cervical cancer services may be available, but neither the clients nor their representatives have any control over those services, where or when they are provided. Hence, the services may be offered at inconvenient times and locations, by personnel that lack cultural competence, and with prohibitive cost or other barriers. A community coalition organized around cancer control can make a difference on that issue (see Advocacy, later in this article) and can later take on other issues, some of which may not be related to medical care.

Working with community coalitions, or organizing them where they did not exist, has been high on the SUCCEED agenda. Several of the papers in this issue of the Journal report on this work. In Atlanta, we worked with other partners to develop and organize the Atlanta Cancer Awareness Partnership, which has sponsored a number of educational and community awareness events and has recently begun to engage in advocacy activities as well.

Evidence-Based approaches

Another factor that influences health inequities is the failure by public health organizations (e.g., health departments, local health clinics, community-based health organizations) to attend to the existing evidence base for promoting breast and cervical cancer screening among all women but especially among African American women, for whom the cancer burden is the most devastating.7 Public health’s efforts at dissemination are paltry given what is known about effective preventive interventions and the success of these interventions in reducing rates of cancer mortality by promoting preventive screenings. The National Cancer Institute has sought to address this issue with the development of its national cancer communications centers and previously through the Cancer Information Service whose resources included cancer control information specialists whose mandate was to be a resources at the community, state and national level about the extant evidence base for cancer control. The adoption of evidence-based innovations often requires considerable technical assistance for effective translation and implementation and these National Cancer Institute (NCI) information specialist were often instrumental in providing technical assistance.8,9 Several evidence-based strategies for promoting breast and cervical cancer screening have been identified and published in The Guide to Community Preventive Services, and the National Cancer Institute’s Research-Tested Interventions Program although many health organizations and agencies have not adopted these strategies.10,11 Another important consideration regarding evidence-based approaches is the fact that many have been tested largely or entirely on White women and empirical support for some of these interventions in African American women is limited.

A significant focus of SUCCEED and its partners is providing technical assistance and training for implementing evidence-based interventions. Below we briefly describe the current sources for evidence-based interventions and programs in cancer control and specifically breast and cervical cancer. An evidence-based intervention is an intervention that has been tested and found to be effective, using rigorous research methods. The National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Services (CIS) describes five levels of evidence of effectiveness.12 Level one programs have the strongest evidence of effectiveness, and level five programs while still considered evidence-based, have the weakest supporting evidence. Several criteria are considered in judging the strength of evidence for a particular intervention. Those criteria are: (1) publication of results in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) funding by a peer-reviewed grant; (3) inclusion in a systematic review; (4) recommendation of effectiveness by the CDC Community Guide; (5) strategy from a systematic review (other than the Community Guide); and strategies from a single study.

Sources of Evidence-based approaches: cancer control P.L.A.N.E.T. (Plan, Link, act, network with Evidence-Based tools)

Cancer Control P.L.A.N.E.T. (CCP) offers a comprehensive approach to assisting cancer control intervention planners.13 It guides the health promotion planner through a series of steps that begin with identifying a specific cancer site for which to develop intervention activities. It uses State Cancer Profiles to assist intervention planners in determining which cancer site and/or geographic location would most benefit from their efforts. At the next step, CCP provides a Regional and State Partnership Web site to assist intervention planners in identifying local partners who may be able to assist in program planning or delivery. In steps three and four, CCP directs the intervention planner to sources of detailed information on interventions. These sources—the Guide to Community Preventive Services and Research-Tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs) are described below. In the final step, CCP provides resources in program evaluation.

The Guide to Community Preventive services

The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide) identifies health promotion strategies that research has shown to be effective.10 Community Guide recommendations are based on a systematic review of all evidence for a given intervention strategy, and as such is considered the gold standard of reviews of empirical evidence. The Community Guide review seeks to provide information to prevention specialists about which intervention approaches have worked, in what settings, and the benefits and costs related to an intervention. For a given approach, the Guide review will yield one of three results: (1) recommended; (2) recommended against; or (3) insufficient evidence. Recommended strategies show strong or sufficient evidence of effectiveness. Strategies that are recommended against, show strong or sufficient evidence that the strategy is not effective or may be harmful. Strategies with insufficient evidence of effectiveness require further research to make a determination of effectiveness. The Community Guide recommends effective strategies or approaches, but not pre-packaged programs, and can be a critical tool for planners of health promotion programs.

Research-Tested Intervention Programs

For several of the strategies recommended by the Community Guide, the National Cancer Institute’s Research-Tested Intervention Programs (RTIPs) programs are available pre-packaged for use. Whereas the Community Guide identifies effective strategies and approaches, RTIPs detail specific interventions that have been demonstrated to be effective and have been packaged for dissemination. These are interventions that are the product of research development and testing through a peer-reviewed research grant, and the intervention outcomes have been published in a peer-reviewed journal.11 The RTIP interventions are rated according to six criteria: (1) dissemination capability; (2) cultural appropriateness; (3) age appropriateness; (4) gender appropriateness; (5) research integrity; and (6) intervention impact.

There are several approaches and specific programs that have been shown to be effective in promoting screening for breast and cervical cancer specifically for African American women. The Community Guide identifies four approaches to breast and cervical cancer screening including:

Client Reminders: Printed materials or telephone reminders informing people that they are either due or late for cancer screening.

Small Media Interventions: Printed materials or videos that provide educational or motivational information to promote cancer screening.

One-on-One Education: A health professional, lay health advisor, or volunteer provides information to individual clients either in-person or by telephone.

Multi-component Media-Interventions: A combination of strategies, including small media, mass media (e.g., radio and/or television advertising), client reminders, and reduced out-of-pocket costs, are used to promote and provide community-wide interventions.

Specific RTIPs relevant to the work of SUCCEED include:

Friend to Friend: a community-based intervention that relies on local organizations and peer volunteers. It aims to promote awareness about the benefits of mammography and address knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs concerning breast cancer and mammography. Friend to Friend uses social dynamics and social networks to encourage observational learning, reinforcement from friends and peers, and emotional support to help overcome barriers to mammography.

The Witness Project: a community-based breast and cervical cancer education program designed to increase awareness, knowledge, and motivation among African American women for screening. The Witness Project involves training a team of local African American breast and cervical cancer survivors, Witness Role Models, to speak to groups of other African American women at local churches and community organizations in rural areas.

Maximizing Mammography Participation: an intervention that is suitable for health care agencies or community-based organizations (CBOs) with strong ties to health care agencies. It includes delivery of reminder postcards and reminder telephone calls to encourage women to schedule and keep mammography appointments. This intervention could be implemented in combination with other approaches and could be modified for cervical cancer screening promotion.

The Forsyth County Cancer Screening Project (FoCaS): a multi-component intervention designed to increase breast and cervical cancer screening among African American women. FoCaS is a program that includes several evidence-based intervention strategies.

Since a central function of SUCCEED is the provision of multi-component technical assistance in evidence-based approaches to promoting breast and cervical cancer screening, achieving our goals is mediated by our ability to support our local and regional partners in the adoption and implementation of these approaches and programs as new evidence-based programs are added to the research literature.

An important element of effective breast and cervical cancer control is the translation and appropriate adaptation of these approaches and programs. One of the challenges faced by prevention specialists is overcoming what might be called the creative imperative: the desire to invent something novel. Considerable personal and professional satisfaction, as well as recognition by others, attends the creation of an original intervention, even if it has not been shown to be efficacious. By contrast, replicating an intervention developed elsewhere may be seen as much less exciting or rewarding. As a compromise, one might be tempted to modify a published intervention in significant ways, thus making it one’s own.

Changing the core components of an intervention is likely to change its effectiveness. A growing body of literature describes surface-level and deep-structure cultural adaptations of evidence-based interventions.13,14 Specifically, this research describes the problems with such adaptations when they compromise the effectiveness of the intervention by compromising those intervention features responsible for the desire effects. In a similar vein, there are unique challenges to developing new interventions including the time to develop the intervention, financial costs associated with development and piloting, as well as the time required to establish the efficacy of the intervention. Oftentimes, however, an evidence-based intervention can be adapted with minor modifications in a manner that is appropriate for the target demographic and may be more economical than the prototype. The National Cancer Institute provides guidance through its resource Using What Works15 on what components of an evidence-based intervention can and cannot be adapted or modified for implementation with different demographic groups.

Legacy Program

Our emphasis on evidence-based approaches and interventions is central to the goals of SUCCEED’s Legacy Program, described in more detail by Wingfield, Ford, and Atkintobi (this volume). Briefly, the goals of the Legacy program include supporting community-based organizations through a competitive grant-making process; increasing the capacity of these organizations to adopt and implement evidence-based approaches that promote breast and cervical cancer screening; and conducting community assessments regarding the impact of breast and cervical cancer. Organizations that successfully compete for a Legacy grant work closely with staff from MSM or one of its partners to carry out the goals of the project. The role of MSM and its partners is to provide technical assistance to grantees to increase the efficiency and impact of their programmatic efforts and support the development of capacity-building and sustainability within the organization. The Legacy program is an annual endeavor sponsored by SUCCEED and we have now provided funding (range $20,000 to $25,000 annually) to four cohorts of Legacy grantees (n=17).

Community action Plan

A cornerstone of MSM’s work in communities over the past 20 years and more is the many partnerships developed with community constituents and stakeholders to promote health equity, reduce disparities in health, education and economic status, and support the central role that communities must have in addressing their own concerns. SUCCEED is based at the Morehouse School of Medicine’s Prevention Research Center (PRC), one of a network of 37 academic research centers funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The MSM PRC engages in interdisciplinary community-based participatory research with a mission to advance scientific knowledge in the field of prevention for African American and other minority and underserved communities and to disseminate new information and strategies for prevention. It is governed by our Community Coalition Board (CCB), a Board constituted of agency representatives (e.g., state and local health departments, Atlanta School System, Atlanta Housing Authority), academic representatives, and neighborhood representatives. The latter are appointed by neighborhood organizations in the communities with which the PRC works; the Board’s by-laws require that they are always in the majority and that one of them serve as the Board Chair. The CCB is a policy-making board (as opposed to an advisory board) and must sign off on any project that the center proposes to undertake—including the REACH US project.

A requirement of REACH US was that each grantee had to develop a Community Action Plan (CAP) that described how it was going to partner with its targeted communities to reduce disparities for their health priority area. Our CAP focused on the disseminating of evidence-based approaches to promote screening for breast and cervical cancer. The other objective of the CAP was to support the development of newly empowered community coalitions. Our efforts in developing our CAP model and community coalitions is reflected in the creation of the Atlanta Cancer Awareness Partnership (ACAP). An additional objective for our CAP was added during the course of the project including engaging our community partners in efforts to understand, influence and change health systems and health policy. Our efforts in this regard focused on developing a cadre of community advocates who could engage members of the legislature around the development of legislation specific to breast and cervical cancer. We partnered with the Georgia Breast Cancer Coalition (GBCC) in pursuit of these goals. The GBCC has provided a number of trainings across Georgia that have included community-based organizations, cancer advocates, concerned citizens, and members of the state legislature.

Conclusion

The goal of this introductory paper was to introduce SUCCEED, the organization of the project and the rationale behinds its goals and objectives. The papers that follow provide more detailed descriptions of specific components of SUCCEED and a paper by Wingfield et al. provides an overview of the Legacy grant-making program. This paper briefly describes the projects that have been supported thus far, and concludes with a selective presentation of impact data and the overall evaluation of the Legacy projects efforts. Again, the goals of the Legacy program include providing limited financial support for community-based organizations implementing evidence-based approaches and interventions that promote breast and cervical cancer screening among African American women while supporting the development of capacity building and sustainability. Grantees also receive regular technical assistance from SUCCEED and participate in training offered by the project. Next a contribution by Miles-Richardson et al. (this volume).16 describes an evaluation of health policies enacted across the tri-state region and how such laws work (or fail to work) to reduce the disparities experienced by underserved and African American women by their impact on the availability of low cost preventive cancer screenings. This paper describes the critical role that effective health policy has in supporting the public health infrastructure at the local and state level in adequately responding to the needs of women for preventive screenings. There is also a contribution by a former Legacy grantee (Samaritan Clinic) in which Fortson and colleagues (this volume) describe their efforts to reduce breast and cervical cancer at their faith-based health clinic, a collaboration between two churches in Albany, Georgia. Important to this contribution is the framing of the faith community as a critical partner to any effort to promote positive health among African Americans. Indeed, it could reasonably be argued that real efforts at programmatic sustainability should begin in dialogue with members of the community and the faith community. Another important offering is found in the contribution of Teal, Moore et al. describing the development and effectiveness afforded through a partnership between a community-based organization and a university. Specifically, these authors describe their efforts to train community lay health advisors in an effort to promote breast cancer screening among older African American women living in rural North Carolina building on the currency of the community agency and incorporating the resources of a comprehensive cancer center (this volume). Finally, a commentary is offered by Martin and Wingfield (this volume) that carefully examines the new mammography recommendations and the implications of those recommendations for underserved and African American women and the work of prevention scientists and cancer control specialists. This commentary raises important questions that require careful attention and answers in order not to stall the efforts to reduce the disproportionate impact of breast cancer on African American women.

This supplement is the first in a series of planned dissemination efforts by SUCCEED and its partners. It is our belief that the answers to the elimination of health disparities and promotion of health equity for cancer and other health outcomes are myriad, complex, and in need of input from academic institutions, community gatekeepers and organizations, public health officials, and most importantly the citizens affected by the burden of preventable disease. In this series of papers, we have sought to reflect that complexity and those voices.

Figure 3.

Determinants of health.

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000.

Table 1. INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY RATES FOR BREAST CANCER IN WOMEN, 2003.

| Incidence Rate |

Mortality Rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | White | Black | White | Black |

| GA | 122.2 | 120.5 | 23.4 | 34.5 |

| NC | 112.5 | 109.0 | 23.4 | 33.5 |

| SC | 120.7 | 116.3 | 22.9 | 31.6 |

Table 2. INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY RATES FOR CERVICAL CANCER, 2003.

| Incidence Rate |

Mortality Rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | White | Black | White | Black |

| GA | 8.6 | 13.1 | 2.5 | 4.4 |

| NC | 6.9 | 9.2 | 2.4 | 4.5 |

| SC | 9.3 | 13.0 | 2.3 | 5.6 |

Table 3. INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY RATES FOR BREAST CANCER IN WOMEN, 2007.

| Incidence Rate |

Mortality Rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | White | Black | White | Black |

| GA | 131.4 | 117.8 | 22.2 | 30.4 |

| NC | 121.7 | 119.7 | 23.0 | 33.7 |

| SC | 121.0 | 113.9 | 22.2 | 31.2 |

Table 4. INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY RATES FOR CERVICAL CANCER IN WOMEN, 2007.

| Incidence Rate |

Mortality Rate |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | White | Black | White | Black |

| GA | 8.4 | 10.5 | 2.2 | 4.4 |

| NC | 7.4 | 9.4 | 2.0 | 3.9 |

| SC | 7.2 | 10.5 | 2.0 | 5.0 |

Acknowledgments

The program is funded by grants from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Grant number 5U58DP000984 REACH US and 1U48DP001907-02 Prevention Research Center).

Notes

- 1.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. Free Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures for African Americans 2011-2012. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17(11):2913–23. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiatt RA, Breen N. Social determinants of cancer: a challenge for transdisciplinary science. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braithwaite RL, Murphy F, Lythcott N, et al. Community organization and development for health promotion within an urban Black community: a conceptual model. Health Educ. 1989 Dec;20(5):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures for African Americans 2011-2012. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in healthcare. JAMA. 2003 Apr;289(15):1969–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller RL, Shinn M. Learning from communities: overcoming difficulties in dissemination of prevention and promotion efforts. Am J Community Psychology. 2005 Jun;35(3–4):169–83. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-3395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guide to Community Preventive Services . Cancer prevention and control, client-oriented screening interventions: client reminders. Community Guide Center; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Cancer Institute . Research-tested interventions programs website. National Cancer Institute; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute . Cancer Information Services website. National Cancer Institute; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Cancer Society . Cancer control planet—state cancer profiles. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnicow K, Solar R, Braithwaite RL, et al. Cultural sensitivity in substance abuse prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(3):271–90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute . Using what works: adapting evidence based programs to fit your needs. National Cancer Institute; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenthal DS. A community coalition board creates a set of values for community-based research. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006 Jan;3(1):A16. Epub 2005 Dec 15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]