Background: Gating mechanisms of TRPC channels are mostly unknown.

Results: Replacing the highly conserved glycine residue within the linker between transmembrane domains 4 and 5 by serine renders TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels constitutively active.

Conclusion: TRPC channel opening seems to require similar constraints than the voltage-gated potassium channels.

Significance: Novel mechanistic insights into structural requirements of TRPC channel gating are provided.

Keywords: Calcium Imaging, Ion Channels, Patch Clamp, Signal Transduction, TRP Channels, Calcium Influx, Channel Gating

Abstract

TRPC4 and TRPC5 proteins share 65% amino acid sequence identity and form Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channels. They are activated by stimulation of receptors coupled to the phosphoinositide signaling cascade. Replacing a conserved glycine residue within the cytosolic S4–S5 linker of both proteins by a serine residue forces the channels into an open conformation. Expression of the TRPC4G503S and TRPC5G504S mutants causes cell death, which could be prevented by buffering the Ca2+ of the culture medium. Current-voltage relationships of the TRPC4G503S and TRPC5G504S mutant ion channels resemble that of fully activated TRPC4 and TRPC5 wild-type channels, respectively. Modeling the structure of the transmembrane domains and the pore region (S4-S6) of TRPC4 predicts a conserved serine residue within the C-terminal sequence of the predicted S6 helix as a potential interaction site. Introduction of a second mutation (S623A) into TRPC4G503S suppressed the constitutive activation and partially rescued its function. These results indicate that the S4–S5 linker is a critical constituent of TRPC4/C5 channel gating and that disturbance of its sequence allows channel opening independent of any sensor domain.

Introduction

TRPC3 channels are in vivo coincidence detectors, which integrate multiple signal transduction pathways originating from the plasma membrane (1, 2). They provide specific transmembrane signaling pathways, shape the membrane potential, and accomplish Ca2+ entry. Thereby, they essentially trigger a variety of functions in excitable and nonexcitable cells. Seven mammalian TRPC proteins (TRPC1–7) have been identified that can be divided into three subgroups by amino acid sequence similarity, C1/C4/C5 (41% sequence identity), C3/C6/C7 (69% sequence identity), and C2. The TRPC proteins form tetrameric channels, which are activated after stimulation of G-protein-coupled receptors or receptor tyrosine kinases linked to phospholipase Cβ or -γ, respectively.

The mammalian TRPC4 and TRPC5 proteins share 65% sequence identity and were initially identified by their sequence similarity with the Drosophila TRP protein (∼40% sequence identity), the founding member of the TRP superfamily of proteins. TRPC4 is expressed in a broad range of tissues, including brain, endothelium, and intestinal smooth muscle. In smooth muscle cells, TRPC4 channels are gated by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and contribute more than 80% to the muscarinic receptor-induced cation current (mICAT) (3). In these cells, TRPC4 channels couple muscarinic receptors to smooth muscle cell depolarization, voltage-activated Ca2+ influx, and contraction, and thereby accelerate small intestinal motility (3). TRPC5 is predominantly expressed in the brain (4). Although channel properties are similar to those of TRPC4, TRPC5 channels are cold-sensitive (5) and can be activated by a variety of additional stimuli, including a rise of cytosolic Ca2+ (6).

The predicted transmembrane topology indicates that TRPC proteins structurally resemble voltage-gated K+ channel proteins, and the overall architecture of TRPC channels and voltage-gated K+ channels is presumably similar. However, their structural relation is not close enough to build functional hybrid channels (7). Nevertheless, like the voltage-gated K+ channel proteins, the TRPC proteins encompass six putative transmembrane helices (S1–S6) (8). Their S1–S4 segments form the sensor domain, and upon tetramerization their S5 and S6 segments constitute a central ion-conducting pore (8). In voltage-gated K+ channels, the cytosolic S4–S5 linker connects the S1–S4 helices to the S5–S6 pore. It triggers motion of the S6 helices to open or close the pore in response to voltage changes. These voltage changes are detected by a typical voltage sensor domain in S4 consisting of four negatively charged amino acid residues (9, 10). Along these lines, a state-dependent interaction between the S4–S5 linker and a site in the S6 transmembrane segment has been suggested to stabilize the closed state of the depolarization-activated Kv7.1 (KCNQ1) channel (11, 12) and the open state of hyperpolarization-activated potassium channels like KAT1 (13) and HCN (14). Although TRP channels lack the typical voltage sensor domain of voltage-activated K+ channels in transmembrane segment S4, the opening of TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels may require similar structural constraints. We identified a conserved glycine residue within the S4–S5 linkers of TRPC4 and TRPC5 being crucial in this respect. Mutation of this glycine in either channel protein to a serine keeps the channels in a constitutive open conformation. This “gain-of-function” mutation was partially rescued by introducing a second mutation just C-terminal of the predicted S6 helix. Our data indicate that the glycine residues at position 503 and 504 identified in the S4–S5 linker of TRPC4 and TRPC5, respectively, are crucial for keeping the channels in a closed and gateable conformation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Transfected cDNA, and Transfection

HEK-293 cells (ATCC, CRL 1573) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA); the Flp-InTM-293 cells were from Invitrogen. HEK-293 cell lines stably expressing the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor type 2 (M2R), TRPC4 (or both) and TRPC5, respectively, were described previously (15). HEK-293 cells and/or HEK-293 M2R cells were transiently transfected with 3 μg of cDNA (TRPC4, TRPC4G503S, TRPC4G503A, TRPC4G503M, TRPC4G503L, TRPC4G503S/S623A, TRPC5G504S, and TRPC5G504C) in 5 μl of the PolyFect® reagents (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). To obtain the bicistronic expression plasmids pdiTRPC4 and pdiTRPC5, the entire coding regions of mouse TRPC4 (accession number NM_016984.3) and mouse TRPC5 (accession number NM_009428.2) were subcloned into the pCAGGS-IRES-GFP vector downstream of the chicken β-actin promotor followed by the consensus sequence for initiation of translation in vertebrates; the stop codons are followed by an IRES and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA. To generate stable inducible Flp-InTM cell lines, the TRPC4G503S and the TRPC5G504S cDNAs were subcloned into the pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector. For patch clamping and Ca2+ imaging, wild-type or stably M2R-expressing HEK-293 cells were plated on glass coverslips 24 h after transfection, and experiments were performed at indicated times. HEK-293 cells stably expressing TRPC4 (with and without the M2 receptor) and TRPC5 and Flp-InTM-293 cells expressing TRPC4G503S or TRPC5G504S after induction in the presence of tetracycline (10 μg/ml) were grown on glass coverslips and were used up to 48 h after plating or induction. All cells, except after transient transfection of TRPC5G504S (see below), were grown in minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Mutagenesis was carried out using the QuikChangeTM site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as described previously. To generate the point mutations, the TRPC4, TRPC5, and TRPC4G503S cDNAs in pBluescriptSK− (Stratagene) were used as templates and the following primer pairs for PCR: TRPC4G503S, 5′-GCC AAT TCT CAC CTG TCG CCT CTG CAG ATA TC-3′ and 5′-GAT ATC TGC AGA GGC GAC AGG TGA GAA TTG GC-3′; TRPC5G504S, 5′-AGC CCT CTG CAG ATC TCT TTG G-3′ and 5′-TAA ATG GGA GTT GGC TGT GAA C-3′; TRPC5G504C, 5′-TGC CCT CTG CAG ATC TCT TTG G-3′ and 5′-TAA ATG GGA GTT GGC TGT GAA C-3′; TRPC4G503S/S623A, 5′-ATT ATT CAT CAT AGC AAT T-3′ and 5′-GCA TAC CAA CTA ATT GCC GAC CAT G-3′; TRPC4G503A, 5′-GCT CCT CTG CAG ATA TCT CTG GG-3′ and 5′-CAG GTG AGA ATT GGC AGT G-3′; TRPC4G503L, 5′-CTG CCT CTG CAG ATA TCT CTG GG-3′ and 5′-CAG GTG AGA ATT GGC AGT G-3′; and TRPC4G503M, 5′-ATG CCT CTG CAG ATA TCT CTG GG-3′ and 5′-CAG GTG AGA ATT GGC AGT G-3′. Amplified cDNAs were subcloned into the pCAGGS-IRES-GFP vector (TRPC4G503S, TRPC4G503A, TRPC4G503M, TRPC4G503L, TRPC4G503S/S623A, TRPC5G504S, and TRPC5G504C), and the pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector (TRPC4G503S and TRPC5G504S). All mutant cDNAs were sequenced on both strands.

Cell Viability Assays

HEK-293 cells grown on coverslips (2.5 cm) were transfected with TRPC5G504S-IRES-GFP cDNA and cultured in minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum in the absence and presence of 1.3, 1.7, 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5 mm EGTA buffering the free Ca2+ concentration (∼2 mm in total) in the culture medium to 700, 301, 103, 3.2, 1, and 0.7 μm, respectively (calculated with WebMaxC). The number of green fluorescent cells in 10 randomly chosen fields of view (×10 magnification) were counted, averaged, and plotted versus the concentration of free Ca2+ in the culture media. To assess viability, Flp-InTM-293 cells expressing TRPC4G503S or TRPC5G504S and HEK-293 cells transiently expressing the TRPC4G503S/S623A-IRES-GFP cDNA were grown in cell culture flasks in minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (with Ca2+) and split into 96-well plates. The cells were counted using a flow cytometer (Guava EasyCyte 8HT) at indicated time points after induction/transfection, and the percentage of living cells, detected as viable by the incubation with Guava ViaCount reagent, was plotted versus time. To evaluate the effect of the TRPC channel inhibitor SKF 96365 on viability, the cells were grown for 48 h in the presence of the indicated concentrations of SKF 96365 in the culture media and then counted by the cytometer as above.

Western Blot Analysis

Lysates were prepared from HEK-293 wild-type cells and the various TRPC4- and TRPC5-expressing HEK-293 and Flp-InTM-293 cells. Cells were grown up to 80–90% confluence on 3.5-cm dishes. After removing the medium and washing in the presence of PBS, the cells were lysed in the presence of 150 μl of Laemmli buffer. The proteins of the lysate were denatured and subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies for TRPC4 and TRPC5 (in-house generated affinity-purified antibodies 1056 (mTRPC4) and 3B3-A5 (mTRPC5)). Proteins were detected using horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies and the Western Lightning chemiluminescence reagent Plus (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Original scans were saved as TIFF files from LAS 3000 (Fuji-film), which were further processed in Adobe Photoshop and/or CorelDraw. Images were cropped, resized proportionally, and brought to the resolution required for publication.

Cell Surface Biotinylation

Nontransfected HEK-293 cells and cells transiently expressing TRPC4G503S/S623A grown up to 80–90% confluency in 3.5-cm culture dishes were placed on ice and washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 8) supplemented with 1 mm MgCl2 and 0.5 mm CaCl2. After incubation in the presence of sulfosuccinimidyl-6-(biotinamido) hexanoate (0.5 mg/ml) at 4 °C for 30 min, the dishes were rinsed twice with PBS supplemented with 1 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm CaCl2, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin and once with PBS, pH 7.4. Cells were harvested in the presence of PBS supplemented with 2 mm EGTA, centrifuged at 1000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min, resuspended in ice-cold PBS, pH 7.4, supplemented with 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, and a mixture of protease inhibitors (lysis buffer), and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 1000 × g and 4 °C for 5 min. Samples containing 600 μg of protein were incubated in the presence of avidin-agarose beads (150 μl of suspension, pre-equilibrated in lysis buffer) at 4 °C for 3 h. After centrifugation (1000 × g) at 4 °C for 5 min, the precipitated beads were washed four times with lysis buffer supplemented with NaCl to give a final concentration of 0.4 m NaCl. Proteins were eluted by 2× Laemmli buffer (60 μl), denatured (37 °C for 30 min), separated by SDS-PAGE, and thereafter blotted on nitrocellulose membranes.

Homology Modeling

Primary sequences of the TRP proteins were retrieved from the Uniprot database. As template for homology modeling, we used the crystal structure 3LUT of the Kv1.2 channel that was obtained from the Protein Data Bank. Initially, the putative transmembrane domains of each TRP channel were predicted with the TOPCONS server that combines predictions from five different topology algorithms (16). Then the sequences representing the consensus region of the transmembrane domain were used as input for a multiple sequence alignment between the target proteins and the 3LUT template (17) using the program ClustalW2 (18). The program Jalview (19) was used to visually inspect the final alignment and to convert the MSA to pir format. Finally, three-dimensional models were built by the Modeler9 package (20). For each TRP sequence, 15 models were computed. Subsequently, the best model (with the highest discrete optimized protein energy score) was selected for further refinement with Modeler using default scripts.

Electrophysiological Recordings and Solutions

Membrane currents were recorded in the tight seal whole-cell patch clamp configuration using an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA Electronics, Lambrecht, Germany). Patch pipettes were pulled from glass capillaries GB150T-8P (Science Products, Hofheim, Germany) at a vertical Puller (PC-10; Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) and had resistances between 2 and 4 megaohms when filled with standard internal solution (in mm: 120 cesium glutamate, 8 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetracesium salt, 3.1 CaCl2 (100 nm free Ca2+, calculated with WebMaxC), pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). Instead of 3.1 mm CaCl2, 0 or 9.8 mm was added to obtain 0 and 10 μm free Ca2+, respectively. Standard external solution contained the following (in mm): 140 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. For monovalent cation-free solution Na+ was replaced by NMDG. IsoCa (0Na) solution contained (in mm) 125 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NMDG, and isoNa (0Ca) solution contained (in mm) 140 NaCl, 3 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH. The La3+ application contained 2 or 0.1 mm LaCl3, and for M2 receptor stimulation 100 μm carbachol were added to the respective external solution. Osmolarity of all solutions ranged between 285 and 315 mOsm.

Voltage ramps of 400 ms duration spanning a voltage range from −100 to 100 mV were applied at 0.5 Hz from a holding potential of 0 mV over a period of 150–500 s using the PatchMaster software (HEKA). All voltages were corrected for a 10-mV liquid junction potential. Currents were filtered at 2.9 kHz and digitized at 100-μs intervals. Capacitive currents and series resistance were determined and corrected before each voltage ramp using the automatic capacitance compensation of the EPC-9. Inward and outward currents were extracted from each individual ramp current recording by measuring the current amplitudes at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, and plotted versus time. Current-voltage (IV) relationships were extracted at indicated time points. For some experiments, the inward and outward currents were normalized to the cell capacitance to get the current density in picoampere/picofarad.

Ca2+ Imaging

Intracellular live cell Ca2+ imaging experiments were performed using a Polychrome V and CCD camera (ANDOR iXon 885, ANDOR Technology, South Windsor, CT)-based imaging system from TILL Photonics (Martinsried, Germany) at a Zeiss Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope equipped with a ×20 Zeiss Plan Neofluar objective. Data acquisition was accomplished with the imaging software TILLVision (TILL Photonics). Prior to the experiments, cells were incubated in media supplemented with 5 μm of the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye fura-2-AM for 30 min in the dark at room temperature and washed twice with nominally Ca2+-free external solution (in mm: 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH) to remove excess fura-2-AM. The fura-2-loaded cells, growing on 2.5-cm glass coverslips, were transferred to a bath chamber containing nominally Ca2+-free solution, and fura-2 fluorescence emission was monitored at >510 nm after excitation at 340 and 380 nm for 30 ms each at a rate of 1 Hz for 600 s. Cells were marked, and the ratios of the background-corrected fura-2 fluorescence at 340 and 380 nm (F340/F380) were plotted versus time.

Data Analysis

Initial whole-cell patch clamp and Ca2+ imaging analyses were performed with FitMaster (HEKA) and TILLVision (TILL Photonics), respectively. IGOR Pro (Wave Metrics, Lake Oswego, OR) was used for further analysis and for preparing the figures. Where applicable, the data were averaged and given as means ± S.E. for a number (n) of cells. For Ca2+ imaging data, the number of averaged experiments (x) and the number of included cells (n) are given as (x/n).

Relative Ca2+ permeabilities (PCa/PNa) of TRPC4 wild-type and mutant channels were calculated using Equation 1,

|

with R = 8.314 J/(mol·K), T = 297 K, and F = 96485 C/mol (21). VCa and VNa represent the reversal potentials of the currents in external saline containing just Ca2+ ([Ca]o) or just Na+ ([Na]o), respectively (see Fig. 7).

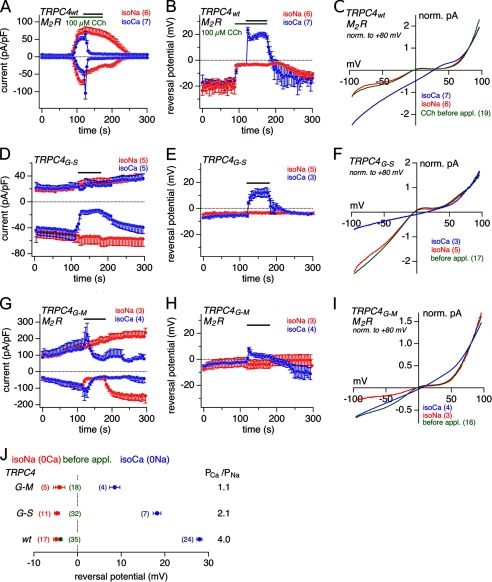

FIGURE 7.

Na+ and Ca2+ permeability of TRPC4WT, TRPC4G-S, and TRPC4G-M. A, D, and G, inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, from HEK-293 cells stably expressing M2R and TRPC4WT (A), HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC4G-S 24 h after induction (D), and HEK-293 cells stably expressing M2R and transiently 24–48 h TRPC4G-M (G). At the indicated time (black bar) isoNa (0Ca, red) or isoCa (0Na, blue) were applied onto the CCh-induced (green bar) TRPC4 current in A, and the constitutive active TRPC4 currents in D and G. B, E, and H represent the reversal potentials of the currents shown in A, D, and G, respectively. The corresponding TRPC4 current-voltage relationships (IVs) before (green) and in isoNa (red) and isoCa (blue) are shown in C, F, and I. All IVs were normalized to the amplitude of the outward current at 80 mV to compare the current-voltage relationship in dependence of the external cation conditions. J, summary of the reversal potentials of the currents via TRPC4WT, TRPC4G-S, and TRPC4G-M in control condition (before application, green, behind red), isoNa (0Ca, red), and isoCa (0Na, blue), and the calculated PCa/PNa. The statistics include further experiments with application at different time points, which could not be averaged together with the traces shown above. Data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged experiments. pA/pF, picoampere/picofarad.

Chemicals

Fura-2-AM was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), all other chemicals were from Sigma.

RESULTS

S4–S5 Linker Alignment

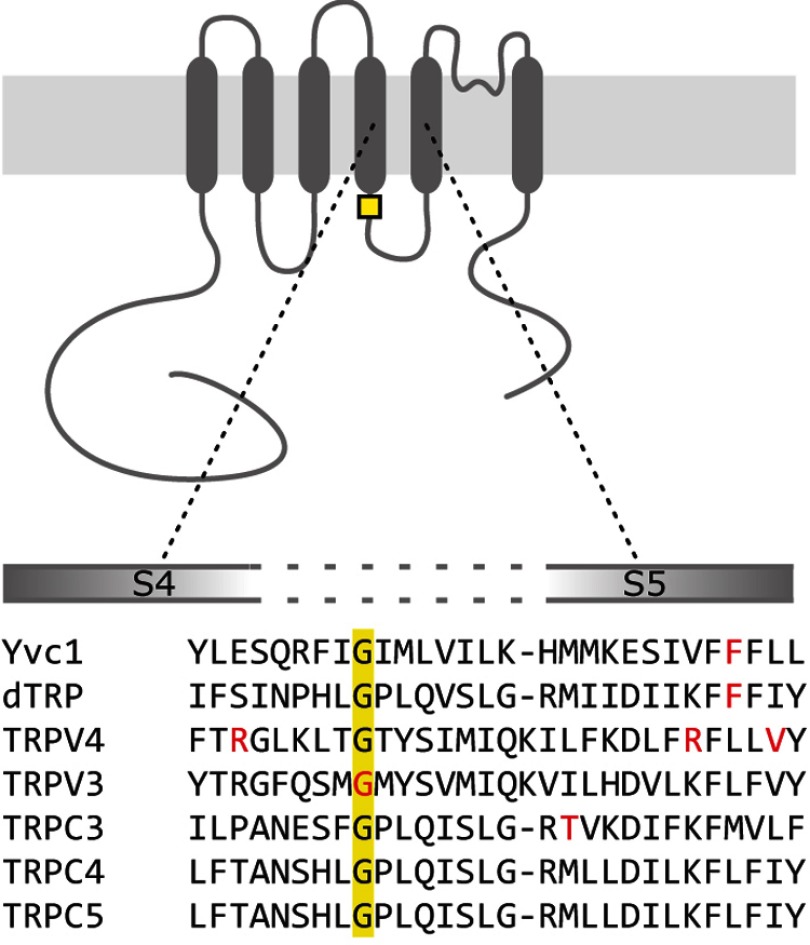

Several gain-of-function mutations within the S4–S5 linker of TRP genes have been identified, including the yeast Yvc1 F380L (22), the Drosophila TRP F550I (23), the human TRPV4 R594H, R616Q, and V620I (24, 25), the human, mouse, and rat TRPV3 G573S, and G573C (26–29), and the mouse TRPC3 T635A mutations (30), which are indicated in red in Fig. 1. The alignment of the S4–S5 linker sequences of these different TRP proteins with the corresponding sequences of TRPC4 and TRPC5 reveals that none of the amino acid residues affected by those mutations are conserved except the glycine residue at position 573 of the human, rat, and mouse TRPV3, which corresponds to position 503 and 504 of the mouse TRPC4 and TRPC5, respectively (Fig. 1, yellow box). In TRPV3, the spontaneous G573S or G573C mutations have been associated with the Nh (non-hair) and Ht (hypotrichosis) mutations in rodents, which are associated with defective hair growth and dermatitis (28), and the Olmsted syndrome in human, which is associated with palmoplantar and periorificial keratoderma and severe itching (26, 27). Introducing these mutations in the mouse or human TRPV3 cDNA results in constitutively active channels in the heterologous HEK-293 expression system (26, 29).

FIGURE 1.

Alignment of the cytosolic S4–S5 linker in TRP proteins. Transmembrane topology of a TRP channel protein with transmembrane helices S1 to S6, intracellular N and C termini, and alignment of the amino acid sequences of the cytosolic S4–S5 linker of yeast Yvc1 (accession number NP_014730), Drosophila (d)TRP (NP_476768.1), human TRPV4 (NP_ 067638.3), and mouse TRPV3 (NP_659567), TRPC3 (NP_062383), TRPC4 (NM_016984.3), and TRPC5 (NM_009428.2) are shown. The published sites of mutations leading to constitutive channel activity (red) and the conserved glycine residues (yellow) are indicated. Alignment was obtained by the MUSCLE and prediction of transmembrane helices by the TMHMM algorithms.

Cell Survival Is Affected by G503S and G504S Mutation in TRPC4 and TRPC5, Respectively

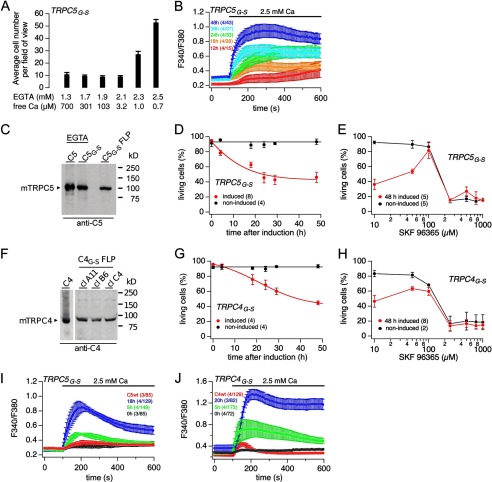

By site-directed mutagenesis, we replaced the conserved glycine residue in the S4–S5 linker in TRPC5 by a serine or a cysteine residue. In a first series of experiments, we transiently expressed the TRPC5G504S or TRPC5G504C cDNA in HEK-293 cells, and we noticed that in both populations a considerable fraction of cells did not survive. Most probably the introduced mutations render the channels open thereby allowing nonrestricted Ca2+ influx into the transfected cells, which causes cell death. Therefore, in a second series of experiments, cells transfected with the TRPC5G504S cDNA were continuously grown in the presence of increasing concentrations of EGTA in the culture medium reducing its free Ca2+ concentration to less than 1 μm. Under these conditions, a substantial number of transfected cells survived (Fig. 2A). To measure Ca2+ influx, we kept the cells in nominally Ca2+-free solution, added 2.5 mm Ca2+ to the bath solution, and monitored changes of the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. As shown in Fig. 2B, Ca2+ influx (F340/F380) increased with time after transfection in TRPC5G504S-expressing cells independent of any receptor activation. Next, we generated two cell lines with tetracycline-inducible TRPC5G504S and TRPC4G503S cDNAs. After induction, the TRPC5G504S and the TRPC4G503S proteins are expressed (Fig. 2, C and F). We next measured cell survival when growing the cells in the presence of “normal” Ca2+ (2 mm) in the culture medium. As shown in Fig. 2, D and G, the number of viable TRPC5G504S- and TRPC4G503S-expressing cells declined over time to about 40% within 48 h after induction, although we could not detect any changes in the survival rate of noninduced cells. Growing the induced TRPC5G504S- and TRPC4G503S-expressing cells for 48 h in the presence of different concentrations of SKF 96365 attenuates the rate of cell death in the range of 100 μm, a concentration known to block TRP channel activity (Fig. 2, E and H). However, higher concentrations of SKF 96365 resulted in a massive reduction of living cells even in the noninduced culture.

FIGURE 2.

Spontaneous Ca2+ influx in TRPC5G-S- and TRPC4G-S-expressing cells. A, HEK-293 cells were transfected with TRPC5G-S-IRES-GFP cDNA and kept for 48 h in media containing 1.3–2.5 mm EGTA (700 to 0.7 μm free Ca2+). The green (transfected) cells from 10 randomly chosen fields of view (×10 magnification) were counted, averaged, and plotted versus EGTA (free Ca2+) concentration in the media. B, cells transfected with TRPC5G-S-IRES-GFP cDNA were grown in the presence of 2.5 mm EGTA for 12–48 h after transfection. Imaging experiments started in nominally Ca2+-free solution, and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, represented by the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380), was measured versus time. Ca2+ influx was challenged by adding 2.5 mm Ca2+ to the bath solution. C and F, Western blot. Expression of TRPC5 (C5) and TRPC5G504S (C5G-S) (C) and TRPC4 (C4) in HEK-293 (F), and TRPC5G504S (C5G-S) (C) and TRPC4G503S (C4G-S) in Flp-InTM-293 cells (FLP) 16 h after induction (F); C4G-S FLP cell clone A11 was used for experiments. HEK-293 cells expressing TRPC5 and TRPC5G-S were grown in the presence of 2.5 mm EGTA (C). D, E, G, and H, viability assays of HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC5G-S (D and E) and TRPC4G-S (G and H). D and G, cells were induced (or noninduced as control) and grown for 0–48 h (as indicated). The percentage of living cells, counted by a flow cytometer (Guava EasyCyte 8HT), was plotted versus time after induction. E and H, viability of HEK-293 cells expressing TRPC5G-S (E) or TRPC4G-S (H), grown in different concentrations of the nonspecific TRPC channel inhibitor SKF 96365. The percentage of living cells was plotted versus the concentration of SKF 96365 in the culture medium 48 h after induction (control = no induction). I and J, HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC5G-S (I; 0, 5, and 18 h after induction) and TRPC4G-S (J; 0, 5, and 20 h after induction) or stably expressing the corresponding wild-type (C4WT and C5WT) were loaded with fura-2-AM and kept in nominally Ca2+-free bath solution. Ca2+ influx was challenged by adding 2.5 mm Ca2+ to the bath solution, and the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, represented by the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380), was measured versus time. Imaging data represent means ± S.E. with x averaged experiments, including n measured cells (x/n), and all other data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged experiments.

Taken together, these data suggest that after induction of TRPC4G503S and TRPC5G504S expression, constitutive Ca2+ influx takes place leading to cell death because of Ca2+ overload. To measure Ca2+ influx in the inducible cell lines, we monitored Ca2+ influx either without induction (“0 h”) or with induction of TRPC5G504S and TRPC4G503S expression for 5 or 18–20 h (Fig. 2, I and J). As controls, we used cell lines stably expressing wild-type TRPC4 or TRPC5 proteins (TRPC4WT and TRPC5WT). Compared with noninduced cells, the wild-type controls show, at best, only a small increase of cytosolic Ca2+ in response to re-addition of extracellular Ca2+. In contrast, cells expressing the TRPC5G504S and TRPC4G503S mutants after induction reveal a substantial Ca2+ influx, which increased over time (Fig. 2, I and J).

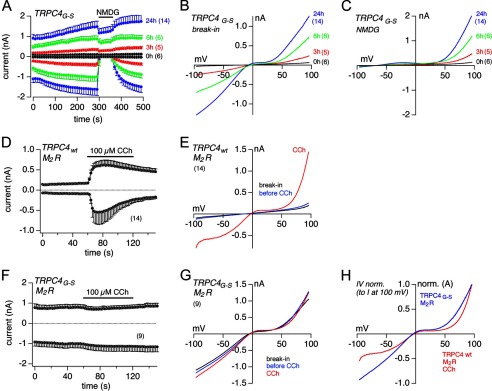

Functional Characterization of Mutant TRPC Channels

Next, we measured the ionic currents after induction of TRPC4G503S expression. Like the Ca2+ influx, constitutive current activities were detected upon establishing the whole-cell configuration, and the current amplitudes, measured at −80 and 80 mV, increased with time after induction (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B shows the corresponding current-voltage relationships (IVs) immediately after break-in. They revealed the typical features of wild-type TRPC4 currents with inward and outward rectification. Substitution of external TRPC channel-permeable monovalent cations by NMDG almost completely prevented the inward current, indicating that this current was carried by cations (see Fig. 3A). Fig. 3C shows the IVs during NMDG application in Fig. 3A. As a control, we transiently expressed TRPC4WT in a HEK-293 cell line stably expressing the M2R and used the cells 24–48 h after transfection. These cells showed no basal activity but responded to application of 100 μm carbachol (CCh) with a large increase in current (Fig. 3D); the corresponding IVs at break-in, before and during CCh application, are shown in Fig. 3E. Transient expression (24 h) of TRPC4G503S into the same M2R-expressing HEK-293 cells revealed spontaneous currents similar to 24 h after induction of the stable inducible TRPC4G503S-expressing HEK-293 cells (Fig. 3F). Stimulation with CCh did not further increase the current. This suggests that the G503S mutation fully activates the TRPC4 channel. The corresponding IVs at break-in, immediately before and during CCh application, are shown in Fig. 3G. Fig. 3H shows the comparison of the normalized IVs of the TRPC4WT current activated by CCh and the spontaneous TRPC4G503S current obtained in the absence of CCh 24 h after transfection of the corresponding cDNA in M2R-expressing HEK-293 cells.

FIGURE 3.

TRPC4G-S cells reveal spontaneous cation-selective currents. A, inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, from HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC4G-S 0, 3, 6, and 24 h after induction plotted versus time. To verify cation conductance, NMDG-based solution was applied as indicated. The corresponding current-voltage relationships immediately after break-in and during the application of NMDG are displayed in B and C, respectively. D, current versus time in HEK-293 cells stably expressing the M2R and transiently transfected with TRPC4WT for 24 h, challenged by the application of 100 μm CCh. E, IVs of currents in D immediately after break-in (black), before (blue), and during the application of CCh (red). F, currents at −80 and 80 mV from M2R-expressing HEK-293 cells 24 h after transient expression of TRPC4G-S stimulated by 100 μm CCh at the indicated time. G, corresponding IVs immediately after break-in (black), before (blue), and during application of CCh (red). H, for comparison, normalized IVs (to I at 100 mV) from M2R- plus TRPC4G-S-expressing cells before application of CCh (blue; see G) and M2R- plus TRPC4WT-expressing cells during stimulation with CCh (red; see E). Data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged cells.

After induction of protein expression, the TRPC5G504S-expressing cells also revealed spontaneous outward and inward currents (Fig. 4A). Like the TRPC4G503S current, the TRPC5G504S current was reduced by substitution of permeable monovalent cations with NMDG in the bath solution (Fig. 4A). Fig. 4, B and C, shows the corresponding IV relationships immediately after break-in and in NMDG-based bath solution, respectively. Cells expressing wild-type TRPC5 did not show such a spontaneous current upon break-in using patch pipettes that contained 100 nm free Ca2+ (Fig. 4D). However, when they were dialyzed with 10 μm free Ca2+ via the patch pipette, an immediate Ca2+-dependent activation of TRPC5 currents was obtained (Fig. 4, D and E). The TRPC5G504S-expressing cells dialyzed intracellularly with 10 μm free Ca2+ did not reveal such an immediate current increase on top of the constitutive activity (Fig. 4F). The average constitutive current amplitude in TRPC5G504S-expressing cells was only slightly affected when cells were infused with 0, 100 nm, and 10 μm free Ca2+ (Fig. 4, F and G). Thus, as already seen for TRPC4G503S, the G504S mutation in TRPC5 also seems to fully activate the current. Fig. 4H shows the comparison of the normalized IVs of the current activated in the presence of intracellular 10 μm free Ca2+ in TRPC5WT cells and the current from TRPC5G504S mutant cells 24 h after induction of TRPC5G504S protein expression.

FIGURE 4.

TRPC5G-S cells reveal spontaneous cation-selective currents. A, inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, from HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC5G-S 0, 10, and 24 h after induction plotted versus time. To verify cation conductance, NMDG-based solution was applied as indicated. The corresponding current-voltage relationships (IVs) immediately after break-in and during the application of NMDG are displayed in B and C, respectively. D, current versus time in HEK-293 cells stably expressing TRPC5WT, with the presence of 100 nm and 10 μm free Ca2+ in the patch pipette. E, IVs of maximal currents in D after break-in with 100 nm (black) and 10 μm free Ca2+ (red) in the patch pipette. F, currents at −80 and 80 mV from HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC5G-S 24 h after induction measured with 0 (light blue), 100 nm (blue), and 10 μm (red) free Ca2+ in the patch pipette plotted versus time. The corresponding IVs immediately after break-in are displayed in G. H, for comparison, normalized IVs (to I at 100 mV) from 24 h induced TRPC5G-S cells directly after break-in (blue; see B) and TRPC5WT cells activated by 10 μm free Ca2+ within the patch pipette (red; see E). Data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged cells.

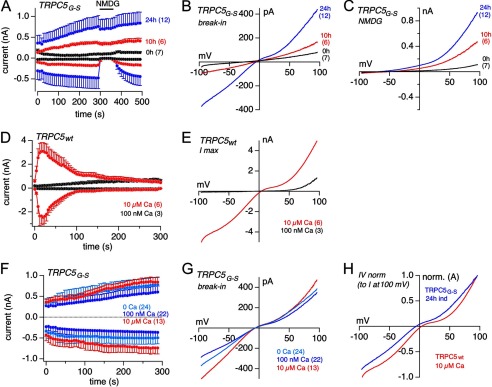

Extracellular La3+ at 1–2 mm typically blocks all TRPC channels, but TRPC4 and TRPC5 are unique in that low extracellular concentrations of La3+ (100 μm) can potentiate already activated currents (21, 31). Therefore, we tested 2 mm and 100 μm extracellular La3+ to inhibit and potentiate, respectively, the constitutive TRPC4G503S- and TRPC5G504S-mediated currents. Both currents could be blocked by 2 mm extracellular La3+, but none of them could be potentiated by 100 μm La3+ (Fig. 5, A and D). The IVs of TRPC4G503S- and TRPC5G504S-mediated currents at break-in, before and during high and low La3+ application, are shown in Fig. 5, B and C, and E and F, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of external La3+ on TRPC4G-S and TRPC5G-S currents. Normalized inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, from HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC4G-S (A) and TRPC5G-S (D) 18–24 h after induction plotted versus time. As indicated by the bars, 100 μm (red traces) or 2 mm La3+ (black traces) were applied. Currents were normalized to the amplitude of the inward current at 120 s (I/I120 s) immediately before application of La3+. The corresponding current-voltage relationships immediately after break-in (black), before (blue), and during the application of 2 mm (B and E) and 100 μm (C and F) La3+ (red) are displayed in B and C for TRPC4G-S and E and F for TRPC5G-S, respectively. Data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged cells.

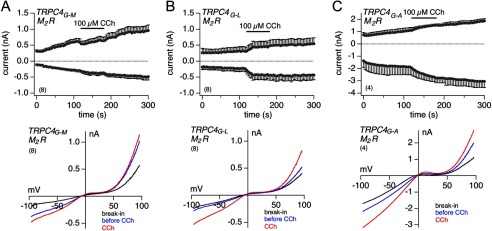

Replacing Gly-503 in TRPC4 by Amino Acid Residues Other than Serine

With the G503S mutation, a nonpolar amino acid residue was replaced by a polar residue. We now replaced the glycine residue at position 503 in TRPC4 by the nonpolar amino acid residues methionine, leucine, and alanine. As already seen for G503S, the mutations G503M, G503L, and G503A all resulted in a constitutive TRPC4 activity, measured 24 h after transient transfection of the corresponding cDNA in HEK-293 M2R cells (Fig. 6, A–C). Stimulation with CCh further increased the constitutive current of the TRPC4G503L and TRPC4G503A mutant channels (Fig. 6, B and C). The upper graphs in Fig. 6, A–C, show inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, and the lower graphs display the IVs of the current at break-in (black) and before (blue) as well as during the application of CCh (red).

FIGURE 6.

Expression of additional TRPC4 mutations at Gly-503 in HEK-M2R cells, and stimulation with carbachol. A–C, inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, from HEK-293 cells stably expressing the M2 receptor and transiently expressing TRPC4 carrying single point mutations at Gly-503 (Gly-Met in A, Gly-Leu in B, and Gly-Ala in C) 24–48 h after transfection. Bars indicate the application of 100 μm carbachol. The corresponding current-voltage relationships immediately after break-in (black), before (blue), and during carbachol stimulation (red) are displayed below the time courses. Data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged experiments.

To determine the relative Ca2+ permeability of TRPC4WT, TRPC4G503S, and TRPC4G503M, we measured the reversal potentials of currents from voltage ramps applied in 140 mm Na+ (nominally Ca2+-free, isoNa) and 125 mm Ca2+ (Na+-free, isoCa) containing external solution (Fig. 7). Inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, from HEK-293 cells stably expressing M2R and TRPC4WT (activated by 100 μm CCh), HEK-293 cells inducibly expressing TRPC4G-S 24 h after induction, and HEK-293 cells stably expressing M2R and transiently 24–48 h TRPC4G-M are shown in Fig. 7, A, D, and G, respectively. Fig. 7, B, E, and H represent the reversal potentials of the currents shown in Fig. 7, A, D, and G, respectively. At the indicated time isoNa (red) or isoCa (blue) was applied. The corresponding TRPC4 current-voltage relationships, normalized to the amplitude of the outward current at 80 mV, before (green) and in isoNa (red) and isoCa (blue), are shown in Fig. 7, C, F, and I. Fig. 7J summarizes the reversal potentials of currents via TRPC4WT, TRPC4G503S, and TRPC4G503M under control conditions (before application, green), in the presence of isoNa (red) and isoCa (blue). Using Equation 1 (see “Experimental Procedures”), we calculated the relative Ca2+ permeability (PCa/PNa) from the reversal potential shift in isoNa to isoCa solution as 4.0 for TRPC4WT (VrevNa −4.9 ± 0.6 mV, n = 17; VrevCa 27.9 ± 0.6 mV, n = 24), 2.1 for TRPC4G503S (VrevNa −4.7 ± 0.6 mV, n = 11; VrevCa 18.2 ± 0.9 mV, n = 7), and 1.1 for TRPC4G-M (VrevNa −4.2 ± 1.3 mV, n = 5; VrevCa 8.5 ± 1.2 mV, n = 4).

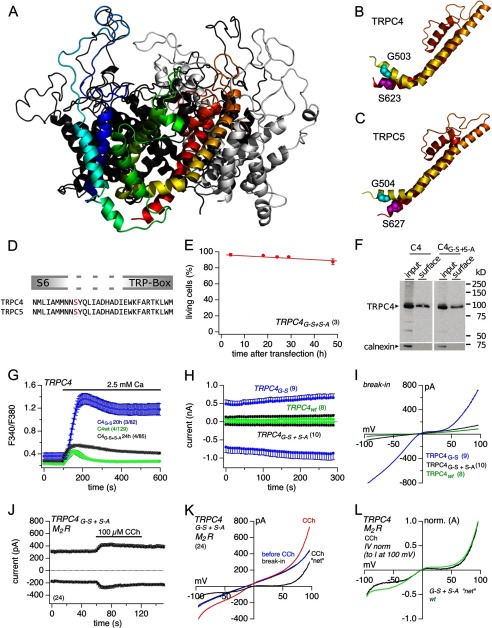

Partial Rescue of the Wild-type Phenotype

Replacing the glycine residue at position 503 in TRPC4 by a polar (serine) or a nonpolar (methionine, leucine, and alanine) residue always led to constitutive activity. For the G503S and G504S mutations in TRPC4 and TRPC5, respectively, it is possible that the polar serine residue, which replaces the nonpolar glycine residue within the S4–S5 linker, interacts with another polar amino acid residue(s) within the channel proteins to keep the channel open. To find potential interaction partners, we constructed a homology model for TRPC4 on the basis of the known structure of a voltage-gated potassium (KV) channel (Fig. 8A; one of the four subunits of TRPC4 is shown in color) (9). Fig. 8B shows the extracted structure for the sequence starting from linker S4–S5 via the transmembrane segment (TM) S5 (yellow), the pore region (orange) to the distal parts of TM S6 (red). According to the model, the S4–S5 linker contacts the distal end of the predicted TM S6 within the same subunit and potentially to helices S5 and S6 of neighboring subunits. In particular, the glycine 503 is located in about 8 Å distance from a serine residue at position 623 that was positioned in the model at the distal end of the predicted TM S6 of TRPC4. When the glycine at position 503 is replaced by a serine, a water-mediated contact may be formed between the hydroxyl groups of both amino acid residues or even a direct contact after some minor conformational rearrangements might occur. This interaction could elicit some constraint on the positions of the S4–S5 linker and the distal part of the S6, and as a result the channel may be forced into an open conformation. If such contacts were indeed formed, replacing the serine residue at position 623 by an alanine might counteract the impact of the mutant serine residue at position 503 in TRPC4 and yield a channel that can be regulated again. For comparison, we also generated a structural model for TRPC5 (Fig. 8C). This model also shows a similar proximity of the amino acids in the positions equivalent to TRPC4 Gly-503 and TRPC4 Ser-623, and the serine residue Ser-623 in TRPC4 is conserved in TRPC5 (Fig. 8D). Thus, we introduced a second mutation S623A into the TRPC4G503S mutant protein, expressed the double mutant in HEK-293 cells, and tested for cell survival, spontaneous Ca2+ influx, and ionic currents. Fig. 8E shows that the survival of HEK-293 cells was not affected by the expression of the double mutant TRPC4G503S/S623A. The double mutated TRPC4 protein is expressed and present in the plasma membrane as shown by Western blot and surface biotinylation (Fig. 8F). In contrast to the spontaneous Ca2+ influx and ionic currents of the TRPC4G503S-expressing HEK-293 cells, almost no constitutive Ca2+ influx (Fig. 8G) or currents (Fig. 8, H and I) appeared in cells expressing the double mutant. In this respect the double mutant closely resembles the wild-type TRPC4.

FIGURE 8.

Possible interaction between residues in S4–S5 linker and distal to S6 and partial reversion of the G503S-induced effect. A, ribbon model of the murine TRPC4 tetramer structure based on the structure 3LUT of the Shaker potassium channel Kv1.2. The subunit in the front is shown in color, the other three subunits are shown in various gray levels. TM segments 1–4 are colored blue and green, TM segment S5 in yellow, the pore helix orange, and TM segment S6 in red. B, blow-up of the modeled conformation for one TRPC4 subunit encompassing the S4–S5 linker, the S5 TM domain (yellow), the pore helix (orange), and the S6 TM domain (red). Gly-503 at the N-terminal end of the S4–S5 linker is shown as cyan spheres; Ser-623 at the C-terminal end of the S6 helix is shown as magenta spheres. C, similar model as in B for murine TRPC5. D, alignment of the TRPC4 and TRPC5 amino acid sequences of the distal S6 segments and adjacent regions, including the TRP box. Serine residues 623 (TRPC4) and 627 (TRPC5) are indicated in red. E, viability assay of HEK-293 cells transiently expressing TRPC4G-S/S-A 0–48 h after transfection. The percentage of living cells, counted by a flow cytometer (Guava EasyCyte 8HT), was plotted versus time after transfection. F, Western blot and surface biotinylation. Surface expression of TRPC4WT and TRPC4G-S/S-A proteins 48 h after transfection of HEK-293 cells is shown. Calnexin was used as negative control for surface biotinylation. Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging (G) and currents at −80 and 80 mV (H) from cells transiently expressing TRPC4G-S and TRPC4G-S/S-A (24 h after transfection) or stably expressing TRPC4WT. I, corresponding current-voltage relationships (IVs) immediately after break-in. J, currents at −80 and 80 mV from stable M2R-expressing HEK-293 cells transiently expressing TRPC4G-S/S-A 24–48 h after transfection plotted versus time. CCh (100 μm) was applied as indicated by the bar. K, corresponding IVs of the current at break-in (gray, behind blue IV), before (blue), and during CCh application (red), and “net” CCh-induced current (current during CCh minus current before CCh; black). L, for comparison, normalized IVs (to I at 100 mV) from net CCh-induced currents in M2R plus TRPC4G-S/S-A-expressing cells (black; see K) or TRPC4WT-expressing cells (green; normalized TRPC4WT IV is the same as already shown in Fig. 3H, red IV). Imaging data represent means ± S.E. with x averaged experiments, including n measured cells (x/n), and all other data represent means ± S.E. with n averaged cells.

To activate TRPC4G503S/S623A channels, we expressed the TRPC4G503S/S623A mutant cDNA in the M2R-expressing HEK-293 cells and applied 100 μm CCh. Fig. 8, J and K, shows the currents in TRPC4G503S/S623A-expressing M2R cells before and during the application of CCh. Stimulation with CCh significantly increased current size, and the normalized IV relationships of TRPC4WT and TRPC4G503S/S623A currents are almost identical (Fig. 8L). These data show that the TRPC4G503S/S623A protein is expressed in the plasma membrane and that TRPC4G503S/S623A channels, like TRPC4WT channels, are activated by CCh via muscarinic receptor activation. Apparently the introduction of a second mutation within the sequence distal to the S6 segment is offsetting the effect of the single G503S mutation introduced into the S4–S5 linker.

DISCUSSION

The data shown here support a TRPC4 and TRPC5 channel model in which the cytosolic S4–S5 linker is crucial for the regulation of channel gating. A single point mutation within this linker encodes hyperactive gain-of-function channels.

In the Shaker potassium channel, the S4–S5 linker forms a ring around the C-terminal end of the S6 helices and may trigger motion of the S6 helices to open or to close in response to voltage changes (10). A similar mechanism is likely to be conserved in TRPC channels, although TRPC proteins have no defined S4 voltage sensor, with only one charged residue within the predicted S4 amino acid sequence. The S4–S5 linker in TRPC4 and TRPC5 proteins resides within the cytosol and includes the sequence GPLQISLGRMLLD; the conservation of this motif is obvious within the members of the TRP proteins (see Fig. 1). In this study we have shown that replacing the conserved glycine residue at position 503 in TRPC4 by any other amino acid residue tested, polar (serine) or nonpolar (methionine, leucine, and alanine), leads to constitutive channel activity. This glycine residue seems to be invariant for keeping the TRPC4 channel, which is not receptor-activated, closed. All replacement amino acids form larger residues than glycine. Thus, maybe “simple” structural constraints might trigger motion of the S6 helices to open the channel pore similar to the mechanism of the voltage-gated potassium channel. Alternatively, it is possible that only the remarkable flexibility of the glycine peptide bond enables closure of the TRPC4 channel.

In the case of replacing the nonpolar glycine residue by the polar serine residue in TRPC4, constitutive activity could be reversed by a second mutation of a polar residue (serine) adjacent to the distal part of the S6 transmembrane domain, probably interacting with the serine in the S4–S5 linker via a water bridge, into a nonpolar residue (alanine). The double mutant TRPC4G503S/S623A channel was not constitutively open but could be stimulated by receptor activation. This suggests a possible mechanism of interaction of the S4–S5 linker with the distal S6 transmembrane domain to open the TRPC4G503S ion channel.

The Gly-to-Ser gain-of-function mutants in TRPC4 and TRPC5 are not further activated by the stimulation of G-protein-coupled signaling pathways via CCh and cytosolic high Ca2+, respectively. Thus, the TRPC4G503S and TRPC5G504S gain-of-function mutations seem to fully open the channels. The corresponding IV relationships resemble the IV of wild-type channels maximally challenged by receptor activation (TRPC4) or high internal Ca2+ (TRPC5). Potentiation in the presence of 100 μm La3+ in the extracellular solution described for both TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels (21, 31, 32) did not occur for the mutant channels either. Both gain-of-function channels maintain robust steady-state inward and outward rectification indicating the existence of additional channel properties such as voltage dependence and intracellular Mg2+ block (33), which are hardly influenced by the mutation. However, the replacement of glycine 503 in TRPC4 changes the relative Ca2+ permeability from PCa/PNa = 4.0 for WT to 2.1 for the Gly-to-Ser and 1.1 for the Gly-to-Met mutation. In the literature PCa/PNa of TRPC4 varies from 1.1 for human TRPC4α (34) and mouse TRPC4β (35), and 7 for bovine TRPC4α (36).

Replacement of the conserved glycine at position 573 by a serine or a cysteine residue in the human, mouse, and rat TRPV3 proteins has been shown to be associated with the Olmsted Syndrome, a rare human congenital disorder, the spontaneous Nh (non-hair) mutation in mice, and Ht (hypotrichosis) mutation in rats (26–28). TRPV3 is expressed in keratinocytes, and the mutant channel proteins are associated with defective hair growth and dermatitis in the rodents and palmoplantar and periorificial keratoderma and severe itching in human patients. The mutant TRPV3 forms constitutively active channels (26, 29). In contrast, replacement of the corresponding glycine residue by a serine in TRPV1 (TRPV1G563S) yields channels that exhibit only slightly enhanced basal activity (37).

However, plenty of other single point mutations in or close to the S4–S5 linker of TRP proteins are reported to result in constitutive channel activity and thus in diverse pathological phenotypes. For example, the T635A mutation in TRPC3 is associated with the loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells and the appearance of a so-called moonwalker phenotype as a result of cerebellar ataxia (30). The F550I mutation in the Drosophila TRP channel is associated with blindness and severe retinal degeneration (23). The human TRPV4 mutation R594H causes autosomal dominant spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, and the R616Q and V620I mutations cause brachyolmia (38). The A419P mutation in TRPML3 is causing a varitint-waddler phenotype with deafness and skin pigmentation defects in mice (39). The F380L mutation in the yeast yvc1 (yeast vacuolar conductance 1) causes stronger responses upon addition of osmotic shock-induced Ca2+ release from the vacuole into the cytosol (22, 40).

The mutant TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels described here cause cell death when expressed in HEK-293 cells, presumably because of the elevation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration as well as membrane depolarization, as a result of constitutively active ion conductance. Growing the TRPC4 and TRPC5 mutant-expressing HEK-293 cells in the presence of SKF 96365, a nonspecific TRPC channel blocker, attenuates the cytotoxic phenotype. Lowering the Ca2+ concentration in the medium prevented cell death indicating that each mutant essentially contributes to Ca2+ influx rather than that other events downstream of TRPC4 and TRPC5 activation and/or expression are involved. Ca2+ imaging and whole-cell patch clamp experiments revealed that the mutated TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels are indeed constitutively active and lead to massive Ca2+ influx. The partial rescue by introducing a second mutation in TRPC4 adjacent to the distal part of the S6 transmembrane helix demonstrates that the Ca2+ influx and hence death of cells expressing the Gly-to-Ser mutant proteins are due to channel function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Wolske, Heidi Löhr, and Christine Wesely for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB894 (to A. B., S. E. P., and V. F.), the Homburg Forschungsförderungsprogramm HOMFOR (to A. B., C. S., and S. E. P.), and the Forschungskommission der Universität des Saarlandes (to A. B., S. E. P., U. W., and V. F.).

- TRPC

- transient receptor potential canonical

- TRP

- transient receptor potential

- IRES

- internal ribosomal entry site

- NMDG

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- M2R

- muscarinic acetylcholine receptor type 2

- CCh

- carbachol

- TM

- transmembrane.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gees M., Colsoul B., Nilius B. (2010) The role of transient receptor potential cation channels in Ca2+ signaling. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2, a003962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu L. J., Sweet T. B., Clapham D. E. (2010) International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXVI. Current progress in the mammalian TRP ion channel family. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 381–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsvilovskyy V. V., Zholos A. V., Aberle T., Philipp S. E., Dietrich A., Zhu M. X., Birnbaumer L., Freichel M., Flockerzi V. (2009) Deletion of TRPC4 and TRPC6 in mice impairs smooth muscle contraction and intestinal motility in vivo. Gastroenterology 137, 1415–1424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Philipp S., Hambrecht J., Braslavski L., Schroth G., Freichel M., Murakami M., Cavalié A., Flockerzi V. (1998) A novel capacitative calcium entry channel expressed in excitable cells. EMBO J. 17, 4274–4282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zimmermann K., Lennerz J. K., Hein A., Link A. S., Kaczmarek J. S., Delling M., Uysal S., Pfeifer J. D., Riccio A., Clapham D. E. (2011) Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 5 (TRPC5) is a cold-transducer in the peripheral nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18114–18119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gross S. A., Guzmán G. A., Wissenbach U., Philipp S. E., Zhu M. X., Bruns D., Cavalié A. (2009) TRPC5 is a Ca2+-activated channel functionally coupled to Ca2+-selective ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34423–34432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalia J., Swartz K. J. (2013) Exploring structure-function relationships between TRP and Kv channels. Sci. Rep. 3, 1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li M., Yu Y., Yang J. (2011) Structural biology of TRP channels. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 704, 1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Long S. B., Campbell E. B., Mackinnon R. (2005) Voltage sensor of Kv1.2: structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science 309, 903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Long S. B., Tao X., Campbell E. B., MacKinnon R. (2007) Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature 450, 376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Labro A. J., Boulet I. R., Choveau F. S., Mayeur E., Bruyns T., Loussouarn G., Raes A. L., Snyders D. J. (2011) The S4–S5 linker of KCNQ1 channels forms a structural scaffold with the S6 segment controlling gate closure. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 717–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Labro A. J., Raes A. L., Grottesi A., Van Hoorick D., Sansom M. S., Snyders D. J. (2008) Kv channel gating requires a compatible S4–S5 linker and bottom part of S6, constrained by non-interacting residues. J. Gen. Physiol. 132, 667–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grabe M., Lai H. C., Jain M., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (2007) Structure prediction for the down state of a potassium channel voltage sensor. Nature 445, 550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prole D. L., Yellen G. (2006) Reversal of HCN channel voltage dependence via bridging of the S4–S5 linker and Post-S6. J. Gen. Physiol. 128, 273–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller M., Shi J., Zhu Y., Kustov M., Tian J. B., Stevens A., Wu M., Xu J., Long S., Yang P., Zholos A. V., Salovich J. M., Weaver C. D., Hopkins C. R., Lindsley C. W., McManus O., Li M., Zhu M. X. (2011) Identification of ML204, a novel potent antagonist that selectively modulates native TRPC4/C5 ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33436–33446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernsel A., Viklund H., Hennerdal A., Elofsson A. (2009) TOPCONS: consensus prediction of membrane protein topology. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W465–W468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen X., Wang Q., Ni F., Ma J. (2010) Structure of the full-length Shaker potassium channel Kv1.2 by normal-mode-based x-ray crystallographic refinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 11352–11357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Waterhouse A. M., Procter J. B., Martin D. M., Clamp M., Barton G. J. (2009) Jalview Version 2–a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25, 1189–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M. A., Madhusudhan M. S., Eramian D., Shen M. Y., Pieper U., Sali A. (2006) Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics, Chapter 5, Unit 5.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jung S., Mühle A., Schaefer M., Strotmann R., Schultz G., Plant T. D. (2003) Lanthanides potentiate TRPC5 currents by an action at extracellular sites close to the pore mouth. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3562–3571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Su Z., Zhou X., Haynes W. J., Loukin S. H., Anishkin A., Saimi Y., Kung C. (2007) Yeast gain-of-function mutations reveal structure-function relationships conserved among different subfamilies of transient receptor potential channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19607–19612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hong Y. S., Park S., Geng C., Baek K., Bowman J. D., Yoon J., Pak W. L. (2002) Single amino acid change in the fifth transmembrane segment of the TRP Ca2+ channel causes massive degeneration of photoreceptors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33884–33889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krakow D., Vriens J., Camacho N., Luong P., Deixler H., Funari T. L., Bacino C. A., Irons M. B., Holm I. A., Sadler L., Okenfuss E. B., Janssens A., Voets T., Rimoin D. L., Lachman R. S., Nilius B., Cohn D. H. (2009) Mutations in the gene encoding the calcium-permeable ion channel TRPV4 produce spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, Kozlowski type, and metatropic dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84, 307–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rock M. J., Prenen J., Funari V. A., Funari T. L., Merriman B., Nelson S. F., Lachman R. S., Wilcox W. R., Reyno S., Quadrelli R., Vaglio A., Owsianik G., Janssens A., Voets T., Ikegawa S., Nagai T., Rimoin D. L., Nilius B., Cohn D. H. (2008) Gain-of-function mutations in TRPV4 cause autosomal dominant brachyolmia. Nat. Genet. 40, 999–1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin Z., Chen Q., Lee M., Cao X., Zhang J., Ma D., Chen L., Hu X., Wang H., Wang X., Zhang P., Liu X., Guan L., Tang Y., Yang H., Tu P., Bu D., Zhu X., Wang K., Li R., Yang Y. (2012) Exome sequencing reveals mutations in TRPV3 as a cause of Olmsted syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 558–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai-Cheong J. E., Sethuraman G., Ramam M., Stone K., Simpson M. A., McGrath J. A. (2012) Recurrent heterozygous missense mutation, p.Gly573Ser, in the TRPV3 gene in an Indian boy with sporadic Olmsted syndrome. Br. J. Dermatol. 167, 440–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Asakawa M., Yoshioka T., Matsutani T., Hikita I., Suzuki M., Oshima I., Tsukahara K., Arimura A., Horikawa T., Hirasawa T., Sakata T. (2006) Association of a mutation in TRPV3 with defective hair growth in rodents. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 2664–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xiao R., Tian J., Tang J., Zhu M. X. (2008) The TRPV3 mutation associated with the hairless phenotype in rodents is constitutively active. Cell Calcium 43, 334–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Becker E. B., Oliver P. L., Glitsch M. D., Banks G. T., Achilli F., Hardy A., Nolan P. M., Fisher E. M., Davies K. E. (2009) A point mutation in TRPC3 causes abnormal Purkinje cell development and cerebellar ataxia in moonwalker mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6706–6711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schaefer M., Plant T. D., Stresow N., Albrecht N., Schultz G. (2002) Functional differences between TRPC4 splice variants. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3752–3759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Obukhov A. G., Nowycky M. C. (2008) TRPC5 channels undergo changes in gating properties during the activation-deactivation cycle. J. Cell. Physiol. 216, 162–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Obukhov A. G., Nowycky M. C. (2005) A cytosolic residue mediates Mg2+ block and regulates inward current amplitude of a transient receptor potential channel. J. Neurosci. 25, 1234–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McKay R. R., Szymeczek-Seay C. L., Lievremont J. P., Bird G. S., Zitt C., Jüngling E., Lückhoff A., Putney J. W., Jr. (2000) Cloning and expression of the human transient receptor potential 4 (TRP4) gene: localization and functional expression of human TRP4 and TRP3. Biochem. J. 351, 735–746 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schaefer M., Plant T. D., Obukhov A. G., Hofmann T., Gudermann T., Schultz G. (2000) Receptor-mediated regulation of the nonselective cation channels TRPC4 and TRPC5. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17517–17526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Philipp S., Cavalié A., Freichel M., Wissenbach U., Zimmer S., Trost C., Marquart A., Murakami M., Flockerzi V. (1996) A mammalian capacitative calcium entry channel homologous to Drosophila TRP and TRPL. EMBO J. 15, 6166–6171 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boukalova S., Marsakova L., Teisinger J., Vlachova V. (2010) Conserved residues within the putative S4–S5 region serve distinct functions among thermosensitive vanilloid transient receptor potential (TRPV) channels. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41455–41462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Verma P., Kumar A., Goswami C. (2010) TRPV4-mediated channelopathies. Channels 4, 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grimm C., Cuajungco M. P., van Aken A. F., Schnee M., Jörs S., Kros C. J., Ricci A. J., Heller S. (2007) A helix-breaking mutation in TRPML3 leads to constitutive activity underlying deafness in the varitint-waddler mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19583–19588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Myers B. R., Saimi Y., Julius D., Kung C. (2008) Multiple unbiased prospective screens identify TRP channels and their conserved gating elements. J. Gen. Physiol. 132, 481–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]