Background: Insulin receptor (IR)-phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway provides neuroprotection to cones.

Results: Loss of PI3K in cones triggers cone degeneration that is not protected by rod derived cone survival factors.

Conclusion: Cones have their own endogenous PI3K-mediated neuroprotective pathway.

Significance: The IR-PI3K signaling pathway may be a target for neuroprotective therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Cell Death, Insulin, Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, Photoreceptors, Insulin Receptor, Photoreceptor Degeneration, Cone Photoreceptors

Abstract

In humans, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy are the most common disorders affecting cones. In retinitis pigmentosa (RP), cone cell death precedes rod cell death. Systemic administration of insulin delays the death of cones in RP mouse models lacking rods. To date there are no studies on the insulin receptor signaling in cones; however, mRNA levels of IR signaling proteins are significantly higher in cone-dominant neural retina leucine zipper (Nrl) knock-out mouse retinas compared with wild type rod-dominant retinas. We previously reported that conditional deletion of the p85α subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) in cones resulted in age-related cone degeneration, and the phenotype was not rescued by healthy rods, raising the question of why cones are not protected by the rod-derived cone survival factors. Interestingly, systemic administration of insulin has been shown to delay the death of cones in mouse models of RP lacking rods. These observations led to the hypothesis that cones may have their own endogenous neuroprotective pathway, or rod-derived cone survival factors may be signaled through cone PI3K. To test this hypothesis we generated p85α−/−/Nrl−/− double knock-out mice and also rhodopsin mutant mice lacking p85α and examined the effect of the p85α subunit of PI3K on cone survival. We found that the rate of cone degeneration is significantly faster in both of these models compared with respective mice with competent p85α. These studies suggest that cones may have their own endogenous PI3K-mediated neuroprotective pathway in addition to the cone viability survival signals derived from rods.

Introduction

Of all of the tissues in the body, the retina is the most susceptible to oxidant stress due to the high levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids (primarily docosahexaenoic acid, 22:6n3) in the outer segments, the high concentration of oxygen that passes through these membranes from the pigment epithelium to the mitochondria in the inner segments, and the light-induced production of free radicals in outer segments (1). In addition, the huge oxygen consumption by the mitochondria in light and dark generates abundant free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Several studies have shown that protection against reactive oxygen species-induced cell death can be mediated via phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), a downstream effector of the insulin receptor (2–5).

Insulin receptors (IR) and insulin signaling proteins are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (6). Previous experiments have suggested a role for insulin signaling in the regulation of food intake (7, 8) and neuronal growth and differentiation (9, 10). Disregulation of insulin signaling in the CNS has been linked to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer and Parkinson disease (11, 12). Cells of bovine and rat retina contain high affinity receptors for insulin (6). IR signaling provides a trophic signal for transformed retinal neurons in culture, and IR activation has been shown to rescue retinal neurons from apoptosis through a PI3K cascade (13). The lack of IR activation leads to neurodegeneration in brain/neuron-specific IR knock-out mice (14). We have previously reported that conditional deletion of IR in rod photoreceptor neurons resulted in a stress-induced photoreceptor degeneration (15).

Although cone photoreceptors constitute a small percent (3–5%) of retinal photoreceptors in humans and rodents (16, 17), they are essential in humans for optimal visual acuity, color vision, and visual perception under moderate to high light intensities. In humans, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy are the most common disorders affecting cones (18–22). Cones are affected indirectly in diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa (RP)2 and directly in cone and cone-rod dystrophies (23–26). Selective loss of cones has been reported in diabetic retinopathy (21, 22), and retinal IR/PI3K/Akt signaling has been shown to be down-regulated in diabetes (27, 28). Insulin/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway has been shown to be essential for cone survival, and activation of this pathway by systemic administration of insulin delays the death of cones in a mouse model of RP (26, 29). These studies suggest the importance of insulin signaling in cones. We previously reported that deletion of three of the five regulatory subunits of PI3K (p85α) resulted in cone (30) but not rod (31) degeneration after 6 months, perhaps due to the differences in the day and night activities between rods and cones (32, 33). One of the differences is in ATP consumption, as its consumption is significantly reduced in rods during the day, whereas it is increased in cones (33). We have previously reported that deletion of Akt2 in rods resulted in photoreceptor degeneration (34) but not in cones as we observed in this study.

To date there are no studies available on insulin receptor signaling in cones, so we examined the expression of proteins involved in insulin receptor signaling this important class of photoreceptors. In some experiments, we used “pure cone” retinas of mice depleted of neural retina leucine zipper (Nrl) (35), a transcription factor necessary for production of rod photoreceptors. We previously showed that conditional deletion of p85α in cones resulted in an age-related cone degeneration (30). The phenotype was not rescued by healthy rods, suggesting that rod-derived cone survival factors (36) may signal through cone PI3K. Interestingly, systemic administration of insulin has been shown to delay the degeneration of cones in mouse models of RP lacking rods (29). These studies led to our hypothesis that survival signals to cones from either rods or within cones mediate their neuroprotective effects through a cone PI3K-dependent manner, or cones may have their own endogenous survival factors. For the current study, we generated two additional mouse models (VPP-cone specific p85α−/− transgenic and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice) to demonstrate the existence of an endogenous cone survival signaling pathway independent of survival signals derived from rods. Our studies suggest that cones may have their own endogenous PI3K-mediated neuroprotective pathway in addition to the cone viability survival signals derived from rods. Even though the degeneration phenotype in cone-specific p85α−/− mice is similar to Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice, our study is novel in that it provides additional evidence that challenges the established dogma that cones rely on rods for survival. Furthermore, this is the first comprehensive study of insulin signaling in cones.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Rabbit polyclonal anti-pan-p85α, anti-P110α, anti-IRβ, anti-IGF1-R, anti-IRS-1, anti-IRS-2, anti-Gab1, anti-Grb14, anti-PDK1, anti-pAkt (S473), anti-Akt1, anti-Akt2, anti-Akt3, anti-mTOR, anti-p70S6K, anti-4E-BP1, anti-GSK-3β, and anti-hexokinase II antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Polyclonal anti-PTP1B antibody was purchased from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA). Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO). Rabbit polyclonal anti-red/green cone opsin (M-opsin) was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Mouse monoclonal anti-Cre antibody suitable for immunohistochemistry was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Polyclonal anti-cone Tα antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Biotinylated peanut agglutinin (PNA) and secondary antibodies were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). DAPI stain used for nuclear staining was purchased from Invitrogen-Molecular Probes. Anti-rhodopsin (RD14) was a kind gift from Dr. Robert Molday (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Rabbit polyclonal anti-cone arrestin 4 antibody was generously provided by Dr. Cheryl Craft (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA). An immortalized mouse cone cell line (661W) (37) was a generous gift of Dr. Muayyad Al-Ubaidi (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK). All other reagents used for buffer preparations were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma.

Animals

The p85α floxed mice (38) were kindly provided by Dr. Lewis Cantley (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA). The Nrl−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Anand Swaroop (NEI, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The generation of human red/green pigment gene promoter mice was reported previously (39). All animals were treated in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Protocols used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the Dean A. McGee Eye Institute.

Animals were born and raised in our vivarium and kept under dim cyclic light (40–60 Lux, 12-h light/dark cycle). For experiments that required enucleating the eye or removing the retina, mice were killed by asphyxiation with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. Mice designated wild type (WT) are controls in which both p85α alleles are floxed. Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 heterozygous mice on a mixed genetic background of 129/C57BL/6 were obtained from Dr. Morris Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania) and bred for six generations with Balb/C mice to generate mice with an albino background. Heterozygotes were bred to generate Akt1−/−, Akt2−/−, and Akt3−/− mice; wild type littermates were used as controls. A breeding colony of VPP (rhodopsin mutant) transgenic mice were obtained from Dr. Connie Cepko (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA) and bred with cone conditional p85α−/− mice to generate cone conditional p85α−/−/VPP rhodopsin mutant mice. All mice were born and raised in 60-Lux cyclic light (12 h on/off) in our animal facility and maintained under these lighting conditions until they were used in an experiment.

Generation of Cone Photoreceptor-specific p85α−/− Mice

To produce mice with cone-specific deletion of p85α, mice expressing Cre recombinase specifically in cones under the control of the human red/green pigment gene promoter (39) were bred with p85α floxed mice in which a 2.6-kb fragment of the mouse pi3k gene containing exon 7 was flanked with loxP sites, which enabled deletion of all three p85α isoforms (p50, p55, and p85) as previously described (38). The breeding strategy to generate Nrl−/−/cone p85α−/− double knock-out mice is described in Table 1. In the initial breeding protocol, Nrl−/− mice were crossed with cone Cre+/−p85αf/f (cone Cre-p85α knock-out) mice, and the resultant F1 generation yielded two genotypes (50% each), Nrl+/−/cone Cre−/−p85αw/f and Nrl+/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f. In the next breeding, we crossed Nrl+/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f mice with Nrl−/− mice, and from the offspring we selected the Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f and mated with Nrl−/−/cone Cre−/−p85αw/f. The resultant F3 generation yielded six genotypes: Nrl−/−/cone Cre−/−p85αf/f (12.5%), Nrl−/−/cone Cre−/−p85αw/f (25%), Nrl−/−/cone Cre−/−p85αw/w (12.5%), Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αf/f (12.5%), Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f (25%), and Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/w (12.5%). Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from tail snips. Each mouse was genotyped for cone opsin-Cre, p85α floxed allele, and Nrl. For Cre genotype screening, a forward primer TTG GTT CCC AGC AAA TCC CTC TGA designed within the promoter DNA sequence and a reverse primer GCC GCA TAA CCA GTG AAACAG CAT designed within the Cre sequence were used to amplify PCR product of 411 bp. To distinguish the p85α floxed allele from the WT p85α allele, primer pairs of CAC CGA GCA CTG GAG CAC TG and CCA GTT ACT TTC AAA TCA GCA CAG were used to amplify a 252-bp fragment from the WT p85α allele and a 301-bp fragment from the floxed p85α allele (see Fig. 6, E and F). For Nrl genotyping, a forward primer TGA ATA CAG GGA CGA CAC CA and a reverse primer GTT CTA ATT CCA TCA GAA GCT GAC were used to detect a knock-out band of ∼450 bp. For wild type, a forward primer GTG TTC CTT GGC TGG AAA GA and a reverse primer CTG TTC ACT GTG GGC TTT CA were used to detect a wild type band of ∼250 bp.

TABLE 1.

Breeding strategy to generate Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− mice

| Breeding between | Genotypes | Expected frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nrl−/− | Cone Cre+/−p85αfs/f | Nrl+/−/cone Cre−/−p85αw/f | 50% |

| Nrl+/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f | 50% | ||

| Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f | Nrl−/−/cone Cre−/−p85αw/f | Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αf/f | 12.5% (double KO mice) |

| Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/f | 25% | ||

| Nrl−/−/cone Cre+/−p85αw/w | 12.5% | ||

| Nrl−/−/cone Cre−/−p85αf/f, w/f, and w/w | 50% (controls) | ||

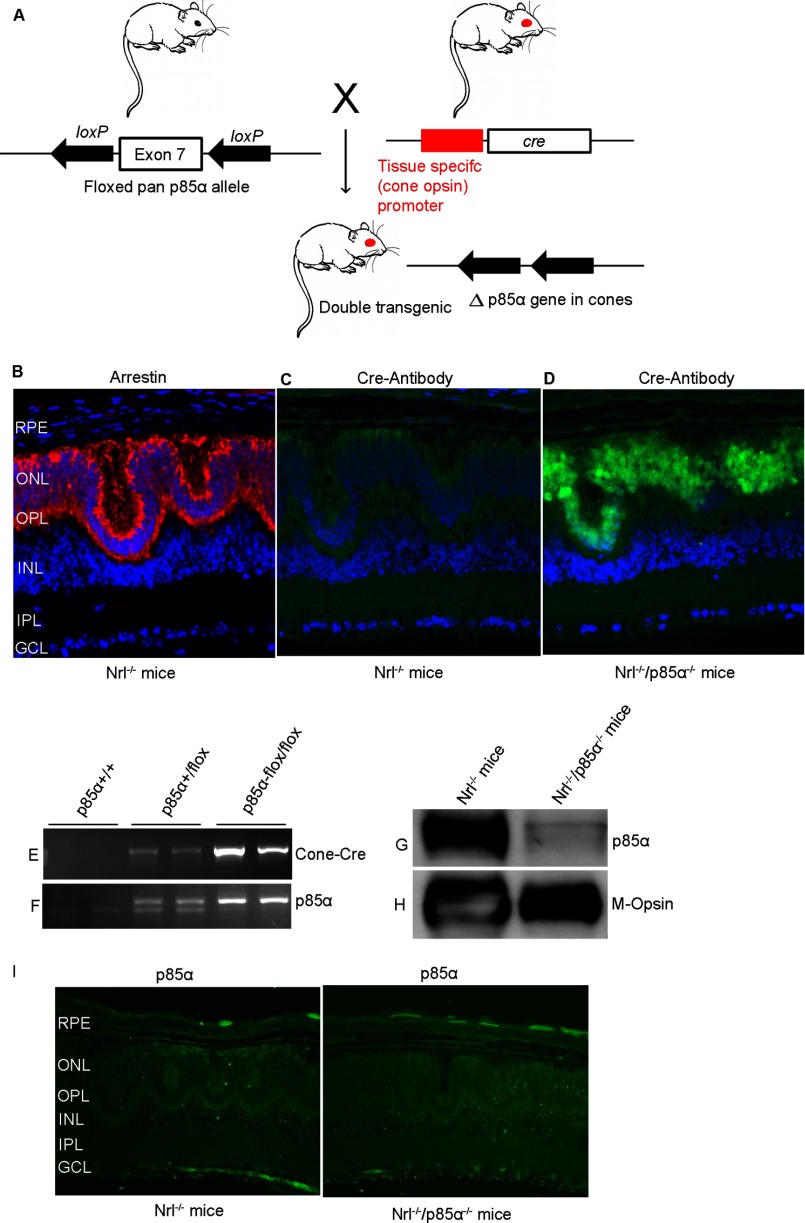

FIGURE 6.

Generation of Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− double knock-out mice. Cone photoreceptor-specific deletion of p85α was achieved by cross-breeding floxed p85α mice to cone-specific Cre-recombinase mice under the control of red/green opsin promoter to delete exon 7 (A). Cone-conditional p85α−/− mice were bred to Nrl−/− mice, generating an Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/−double knock-out mouse line as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− retinal sections were subjected to immunohistochemistry with anti-arrestin (B) anti-Cre (C and D), and anti-p85α (I) antibodies. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Mouse tail DNA samples were genotyped for cone opsin cre (E) and floxed p85α (F) genes. POS were prepared from Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− mouse retinas by discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation. Equal amounts of POS proteins (20 μg) were immunoblotted with anti-p85α (G) and anti-M-opsin (H) antibodies.

Preparation of Tissue for Paraffin Sectioning Using Prefer as a Fixative

Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and the eyeballs were placed in Prefer solution (Anatech Ltd, Battle Creek, MI) for 15 min at room temperature followed by 70% ethanol overnight. The tissue was paraffin-embedded and 5-μm-thick sections were cut and mounted onto slides. Sections were deparaffinized in 2–3 changes of xylene (10 min each) and hydrated in 2 changes of 100% ethanol for 3 min each, 95 and 80% ethanol for 1 min each, and then rinsed in distilled water. The slides were then subjected to antigen retrieval (boiled in 10 mm sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and in sub-boiling temperature for 10 min and cooled down for 30 min). The slides were washed 3 times in 1× PBS containing 0.1%Triton X-100 and blocked with horse serum for 1 h, and primary antibody was added overnight at 4 °C. For fluorescent detection, slides were incubated with a mixture of Texas Red anti-mouse and FITC anti-rabbit antibodies (Vector Laboratories), each diluted 1:200 in PBS with 10% horse serum. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the slides were washed with PBS and cover-slipped in 50% glycerol in PBS. Antibody-labeled complexes were examined on a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a digital camera, and images were captured using Metamorph (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA) image analysis software. For quantitation, all images were captured using identical microscope and camera settings so that intensities of the digital images quantitatively reflected antibody binding.

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of IR signaling proteins and cone and rod photoreceptor specific proteins (short and middle-wavelength cone opsin, rhodopsin and cone and rod transducin α-subunits) were analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR using specific primer pairs (Table 2) using Primer3 software. All primer sets were designed from mRNA sequences spanning big introns to avoid amplification from possible genomic DNA contamination. The primer sequences were checked by a BLAST search to assure sequence specificity. RNA (TRIzol and Pure link RNA kit; Invitrogen) was isolated from two mice (pooled four retinas), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III first strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen). The RT products were diluted 1:3, and 2 μl of each of the diluted RT products and 3 pmol of primers and Eva green super mix (Bio-Rad) were used for a final volume of 10 μl. The PCR was carried out on a CFX96TM Real-Time System and C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). Fluorescence changes were monitored after each cycle (SYBR Green). Melting curve analysis was performed (0.5 °C/s increase from 55 to 95 °C with continuous fluorescence readings) at the end of 40 cycles to ensure that specific PCR products were obtained. Amplicon size and reaction specificity were confirmed by electrophoresis on a 2.0% agarose gel. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The average CT (threshold cycle) of fluorescence units was used for analysis. Each mRNA level was normalized by the 18 S rRNA levels. Quantification was calculated using the CT of the target signal relative to the 18 S rRNA signal in the same RNA sample. Effects were quantified and expressed by the x-fold change method calculated as: mean CQ (quantification cycle) gene − mean CQ housekeeping gene = dCQ and -fold = 2∧ − dCQ. The mRNA levels were averaged in the six Nrl−/− mice (three samples from two mice each) and compared with those of the WT mice.

TABLE 2.

Real-time PCR primers to study the gene expression of IR signaling

MWL, middle wavelength; SWL, short wavelength.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| IR | CCCCCTGATAACTGTCCAGA | CTCCATCTCCAGCTCCTCAC |

| IGF1-R | GACGGACTACTACCGGAAAGG | ACGAAGAACTTGCTCGTTGG |

| P110α | GATTTTGGGCACTTTTTGGA | CAGAGCCAAGCATCATTGAA |

| p85α | TGACGAGAAGACGTGGAATG | CCGGTGGCAGTCTTGTTAAT |

| PTP1B | ACCTGTGGGGATGAAGACAG | ATGCACACATTGACCAGGAA |

| Grb14 | TTTCTTGGTACGGGATAGTCAGA | CAGCTGGATGAGGTCTGTGA |

| SRC | TACCGTATGTCCCACATCCA | CCAGTTTCTCGTGCCTCAGT |

| mTOR | CGGTTTGGTGAAACCAGAAG | GTGAGATGTTGCCTGCTTGA |

| P70S6 kinase | CTCAGTGAAAGTGCCAACCA | CGCTCACTGTCACATCCATC |

| 4E-BP1 | GGGGACTACAGCACCACTCC | ATCGCTGGTAGGGCTAGTGA |

| Rhodopsin | CAAGAATCCACTGGGAGATGA | GTGTGTGGGGACAGGAGACT |

| Rod Tα | GAGGATGCTGAGAAGGATGC | TGAATGTTGAGCGTGGTCAT |

| Cone Tα | GCATCAGTGCTGAGGACAAA | CTAGGCACTCTTCGGGTGAG |

| MWL opsin | CTCTGCTACCTCCAAGTGTGG | AAGTATAGGGTCCCCAGCAGA |

| SWL opsin | TGTACATGGTCAACAATCGGA | ACACCATCTCCAGAATGCAAG |

| 18 S RNA | TTTGTTGGTTTTCGGAACTGA | CGTTTATGGTCGGAACTACGA |

Immunostaining of Retinal Whole-mounts

Eyes were enucleated and placed in cold Hanks' balanced salt solution buffered with 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.2), after which the cornea and lens were removed, and retinas were carefully isolated. Relaxing cuts were made in the retinal margins, and the whole retina was flattened onto a black filter membrane. Whole-mounted retinas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C for 2 h and rinsed in PBS, and nonspecific labeling was blocked using 10% horse serum in PBS. Whole-mounts were incubated in a combination of biotinylated PNA (1:500) and anti-cone arrestin (1:500) or anti-cone Tα (1:50) overnight at 4 °C. Streptavidin conjugated to Texas Red (1:250) was used to visualize PNA labeling. Cone arrestin or cone-Tα immunoreactivity was visualized using an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200). Labeling in retinal whole mounts was imaged using either a Nikon Eclipse E800 (Tokyo, Japan) or an Olympus IX70 (Olympus USA, Center Valley, PA) epifluorescence microscope.

Preparation of Photoreceptor Outer Segment Membranes from Cone-dominant Nrl−/− Retina

Photoreceptor outer segments (POS) were prepared using discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation. Thirty Nrl−/− mouse retinas were homogenized in ice-cold 47% sucrose solution containing 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) (buffer A). Retinal homogenates were transferred to centrifuge tubes and sequentially overlaid with 42, 37, and 32% sucrose dissolved in buffer A. The gradients were spun at 82,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The 32%/37% interfacial sucrose band containing POS membranes was harvested and diluted with 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 100 mm NaCl and 1 mm EDTA and centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 min. The POS pellets were resuspended in 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 100 mm NaCl and 1 mm EDTA and stored at −20 °C. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA reagent from Pierce following the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Culture

661W cone cell line and HEK-293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance and post-hoc statistical analysis using Bonferroni pairwise comparisons were used to determine statistical significance (p < 0.05).

RESULTS

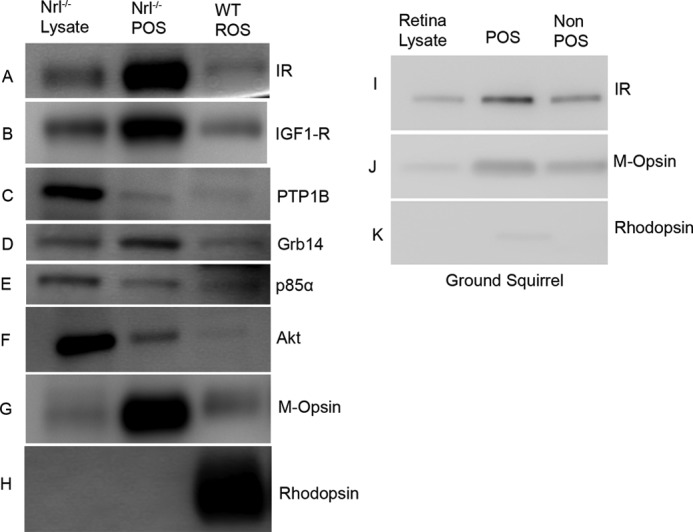

Expression of Insulin Receptor Signaling Proteins in Mature Cone Photoreceptors

To determine whether mature cone photoreceptors express insulin signaling protein in vivo, we took advantage of the Nrl−/− mouse model, where the photoreceptor population consists exclusively of cones by virtue of the absence of the rod differentiation transcription factor Nrl (35). Retinas from and Nrl−/− and wild type mice were harvested and used for the preparation of POS membranes, which were immunoblotted with antibodies to the IR, insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 (IGF-1R), protein-tyrosine phosphatase-IB (PTP1B), p85α, Akt, and growth factor receptor bound protein-14 (Grb14). Rod and cone photoreceptor-specific proteins, rhodopsin and M-opsin, were used as markers. The results indicate that mature cone POS express IR, IGF1-R, PTP1B, Grb14, p85α, and Akt (Fig. 1, A–H). The rod-specific protein marker opsin was absent from Nrl−/− POS and Nrl−/− retinal lysates, both of which contained M-opsin (Fig. 1H).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of IR signaling proteins in POS. POS were prepared by discontinuous sucrose (47, 42, 37, and 32%) density gradient centrifugation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Retina lysates prepared from Nrl−/− mice and POS from Nrl−/− and wild type mice were immunoblotted with anti-IR, anti-IGF1-R, anti-PTP1B, anti-Grb14, anti-p85α, anti-Akt, anti-M-opsin, and anti-rhodopsin antibodies (A–H). POS and non-POS fractions prepared from ground squirrel retina were immunoblotted with anti-IR, anti-M-opsin, and anti-rhodopsin antibodies (I–K). Equal amounts of protein from mice (5 μg) and squirrel (5 μg) were applied to the gel.

To further establish the existence of insulin receptor signaling pathway proteins in cone photoreceptors, we prepared POS from cone-rich ground squirrel retinas (∼90% cones) (40). Immunoblot analysis with anti-IR antibody shows its expression in POS (Fig 1, I–K). Some of the antibodies against IR signaling proteins did not recognize squirrel tissue (data not shown). Higher levels of M-opsin were present in ground squirrel POS compared with non-POS (Fig. 1K). The rod-specific protein marker opsin was barely detected in ground squirrel POS (Fig. 1K).

Localization of Insulin Signaling Proteins in Cone Photoreceptors

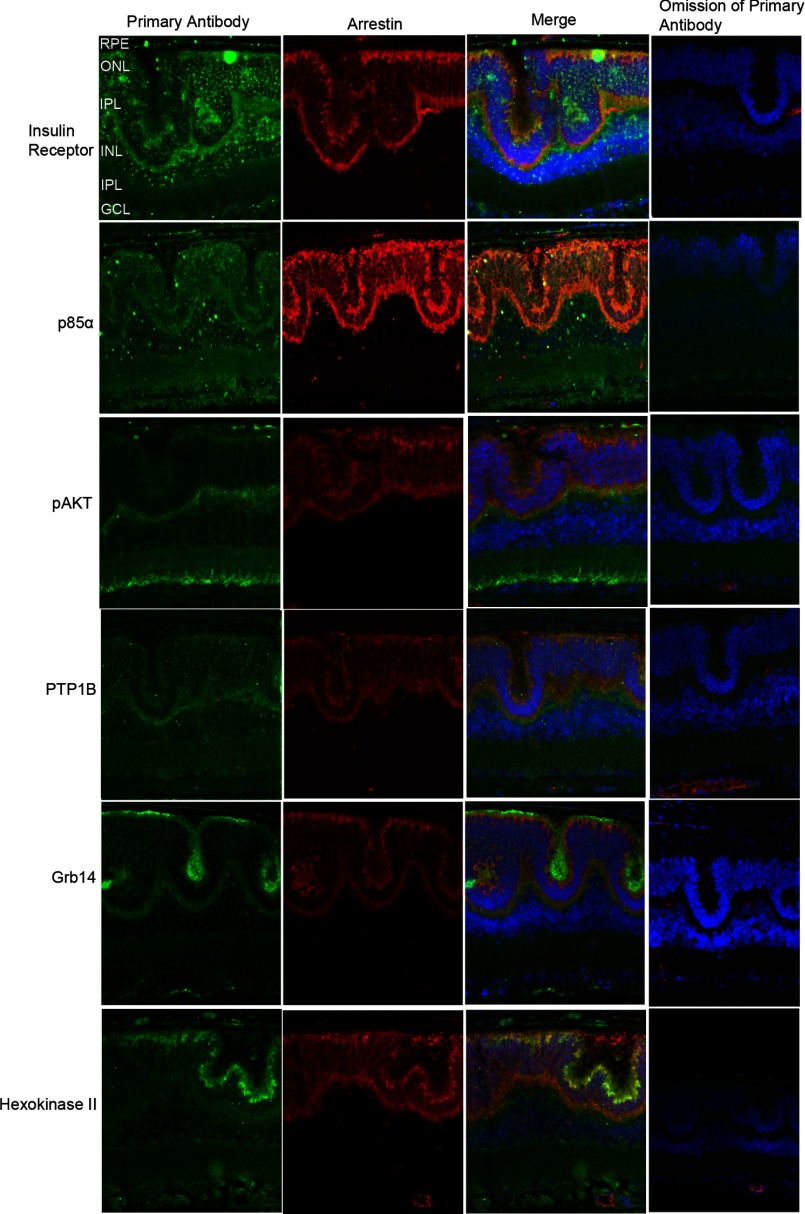

In the Nrl−/− retina, the absence of the transcription factor leads to the development of only functional cone-like cells. The Nrl−/− retina is characterized by large undulations of the outer nuclear layer, commonly known as rosettes. These arise due to defects in the outer limiting membrane and delayed maturation of a subset of photoreceptors (41). To examine the localization of insulin signaling pathway proteins in Nrl−/− retina, Prefer-fixed Nrl−/− retina sections were co-labeled with primary antibodies against various IR signaling pathway proteins and arrestin, a photoreceptor-specific marker. The arrestin antibody we used cross-reacts with both rod and cone arrestin (42). In this study we labeled the Nrl−/− retina sections with IR, p85α, pAkt, PTP1B, Grb14, and hexokinase II. We also tried total Akt antibody but failed to observe the immunoreactivity toward Nrl−/− retina, although Akt was seen on Western blots (Fig. 1F). Hexokinase II is a downstream effector of Akt (43), and hence, we labeled the Nrl−/− retina with hexokinase II antibody. Negative controls include the omission of primary antibodies. We found that IR, p85α, pAkt, PTP1B, Grb14, and hexokinase II (green signal) co-localized (Merge) with photoreceptor-specific marker arrestin (red signal), suggesting that IR signaling proteins are expressed in cone photoreceptors (Fig. 2). Omission of primary antibody did not show any further staining, attesting to the specificity of antibodies toward their specific target protein epitopes. It should be noted that the secondary anti-mouse antibody (red signal) non-specifically labeled endogenous IgGs in the blood vessels (Fig. 2, omission of the primary antibody panel). Nuclei are stained with DAPI in the last two columns.

FIGURE 2.

Immunocytochemical analysis of IR signaling proteins in Nrl−/− mouse retina. Prefer-fixed sections of Nrl−/− mouse retinas were subjected to immunohistochemical analysis with anti-IR, anti-p85α, anti-pAkt (Ser-473), anti-PTP1B, anti-Grb14, and anti-hexokinase II antibodies. All sections were co-labeled with IR signaling proteins (green) and photoreceptor specific protein marker arrestin (red). For controls, primary antibodies were omitted. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue).

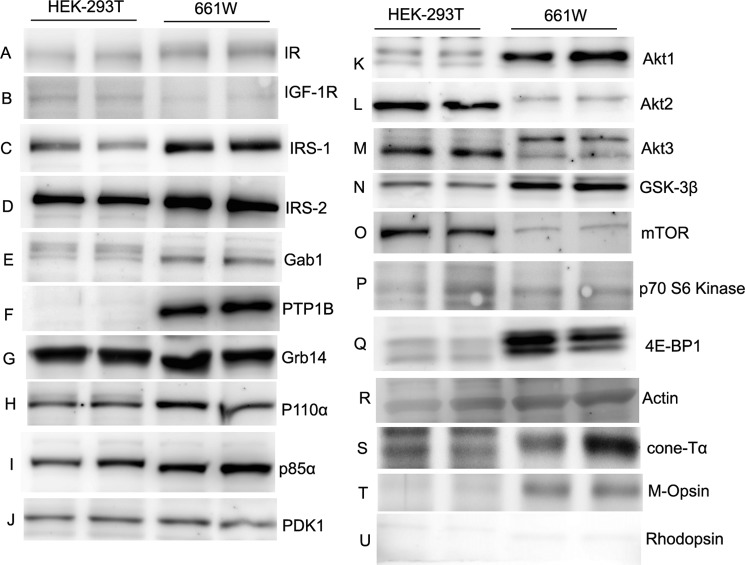

Expression of IR Signaling Proteins in Cone Photoreceptor Cell Line

To further establish the existence of an IR signaling pathway in cone photoreceptors, we analyzed immunoblots of lysates of 661W cells (a mouse retinal photoreceptor-derived cone-like transformed cell line (37)) for IR signaling protein expression. Human embryonic kidney cell (HEK-293T) lysates were used as control. Equal amounts of proteins from 661W and HEK-293T cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-IR, anti-IGF1-R, anti-IRS-1, anti-IRS-2, anti-Gab1, anti-PTP1B, anti-Grb14, anti-P110α, anti-p85α, anti-PDK1, anti-mTOR, anti-p70 S6 kinase, anti-4E-BP1, anti-GSK-3β, anti-actin, anti-cone Tα, anti-M-opsin, and anti-rhodopsin antibodies. The results indicate that all proteins either upstream or downstream of IR signaling pathway are expressed in the 661W cone-like cell line (Fig. 3). The cell line also expresses the markers of cone photoreceptor cells, cone Tα, and M-opsin but not the rod cell marker rhodopsin (Fig. 3). These results further confirm the existence of an IR signaling pathway in cones.

FIGURE 3.

Expression levels of IR signaling proteins in 661W cone cell line. Cell extracts (20 μg of protein) from HEK-293T and 661W cone cell lines from two independent cultures were immunoblotted with anti-IR, anti-IGF1-R, anti-IRS-1, anti-IRS-2, anti-Gab1, anti-PTP1B, anti-Grb14, anti-p110α, anti-p85α, anti-PDK1, anti-Akt1, anti-Akt2, anti-Akt3, anti-GSK-3β, anti-mTOR, anti-p70S6K, anti-4E-BP1, anti-actin, anti-cone-Tα, anti-M-opsin, and anti-rhodopsin antibodies.

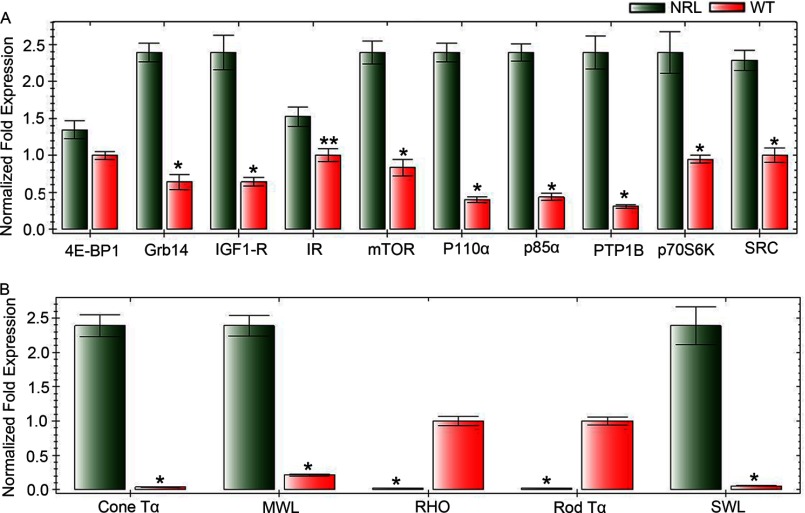

Expression Levels of Proteins Involved in the IR Signaling Pathway in Rod and Cone-dominant Retina

Real-time RT-PCR analysis was used to confirm the expression levels of proteins involved in the IR signaling pathway and a subset of cone and rod specific photoreceptor genes in rod and cone-dominant retinas. The primers used in this study are described in Table 1. cDNAs were prepared from RNA isolated from three groups of independent wild type and Nrl−/− mouse retinas (each group has four retinas from two mice). The mRNA levels of these genes were normalized against 18 S rRNA levels. The results indicate that expression levels of IR, IGF1-R, Grb14, 4E-BP1, mTOR, P110α, p85α, PTP1B, p70S6 kinase, and Src are significantly higher in cone-like Nrl−/− retina compared with rod dominant retina (Fig. 4). The expression levels of cone photoreceptor-specific markers cone Tα, medium wavelength opsin, and short wave length opsin were significantly higher in cone-like Nrl−/− retina compared with rod dominant retina, whereas rod photoreceptor-specific markers rhodopsin and rod Tα were almost absent in cone-like Nrl−/− retina compared with rod dominant retina (Fig. 4). These studies further confirm the existence of an IR signaling pathway in cone photoreceptor neurons.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of mRNA levels of IR signaling proteins in rod- and cone-dominant retina. Equal amounts of retinal mRNA from three independent Nrl−/− and C57BL/6 mice were used for real-time RT-PCR and normalized by 18 S rRNA levels. mRNA levels were averaged for 4E-BP1, Grb14, IGF1-R, IR, mTOR, p110α, p85α, PTP1B, P70S6K, Src, cone-Tα, middle wavelength (MWL) cone opsin, rhodopsin, rod Tα, and short wavelength (SWL) cone opsin. Each mRNA level in Nrl−/− and C57BL/6 mice was expressed as normalized -fold expression (normalized by 18 S rRNA). The data are the mean ± S.D. n = 3. **, p < 0.05; *, p < 0.001.

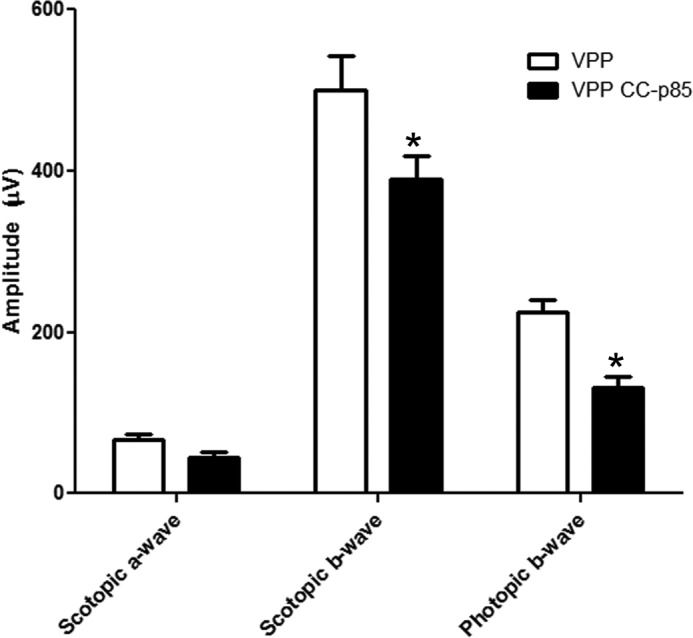

Generation of Cone Cre-p85α−/−/VPP Transgenic Mice

VPP mice possess a mutant transgene for opsin and exhibit a progressive rod degeneration that resembles one form of human autosomal dominant RP (44). Rod degeneration in these mice is followed by cone degeneration (44). Furthermore, the reduced electroretinography (ERG) function in these mice is correlated with the rate of retinal degeneration (44). To determine whether the loss of p85α in cones exacerbates the loss of cones before rod degeneration, we generated cone p85α−/−/VPP transgenic mice. At 1-month age, the cone p85α−/−/VPP mice had significantly lower scotopic b-wave and photopic b-wave amplitudes than the VPP mice; however, scotopic a-wave amplitudes remained the same in both groups (Fig. 5). The reduction in scotopic b-wave amplitude in p85α−/−/VPP transgenic mice was surprising, as there was no difference in the a-wave values. We previously reported that ablation of p85α in cones leads to progressive disorganization of synaptic ultrastructure in surviving cone terminals, indicating that PI3K signaling is critical to the maintenance of synaptic terminals and connections by cones (30). It may be that the synaptic changes noted in the cones have some effect on rod b-wave function. These results suggest that survival signals to cones from either rods or within cones, independent of rod survival signals, mediate their neuroprotective effects through PI3K.

FIGURE 5.

Function of VPP and VPP/p85α−/− mouse retina. Scotopic a- and b-wave and photopic b-wave ERG amplitudes of VPP and VPP-cone-cre-p85α−/− mice at 1 month of age are shown. Data are the mean ± S.D. n = 3; *, p < 0.05.

Generation and Characterization of Nrl−/−/cone p85α−/− Double Knock-out Mice

To produce mice with cone-specific deletion of p85α, mice expressing Cre recombinase specifically in cones under the control of the human red/green pigment gene promoter (39) were bred with p85α floxed mice in which a 2.6-kb fragment of the mouse pi3k gene containing exon 7 was flanked with loxP sites, which enabled deletion of p85α in cones (Fig. 6A). The breeding strategy to generate Nrl−/−/cone p85α−/− double knock-out mice is described in Table 1.

To ensure that Cre expression in cones was working properly, we assessed Cre protein expression and cellular localization in the retinas of Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− littermates by immunofluorescence microscopy using an anti-Cre antibody (Fig. 6, C and D). Arrestin immunostaining was used to localize cone photoreceptors in Nrl−/− retina (Fig. 6B). Cre expression was localized to cone photoreceptor nuclei in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− retinas (Fig. 6D) but was absent in Nrl−/− (Fig. 6C). To determine the deletion of p85α in Nrl−/− retinas, we prepared POS from Nrl−/−/p85α−/− and Nrl−/− retinas on a discontinuous sucrose density gradient centrifugation. POS proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-p85α and anti-M-opsin antibodies, and densitometric analysis of immunoblots was performed in the linear range of detection, and absolute value of p85α was normalized to M-opsin. The Nrl−/− (p85α/M-opsin) was set as 100% (data not shown). The results indicate a deletion of >80% of p85α in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice compared with Nrl−/− mice (Fig. 6, G and H). Consistent with these observations, immunohistochemical analysis with p85α antibody also shows a decreased expression of p85α in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice compared with Nrl−/− mice (Fig. 6I).

Effect of p85α Deletion on Cone Survival in Nrl−/− Mouse Retinas

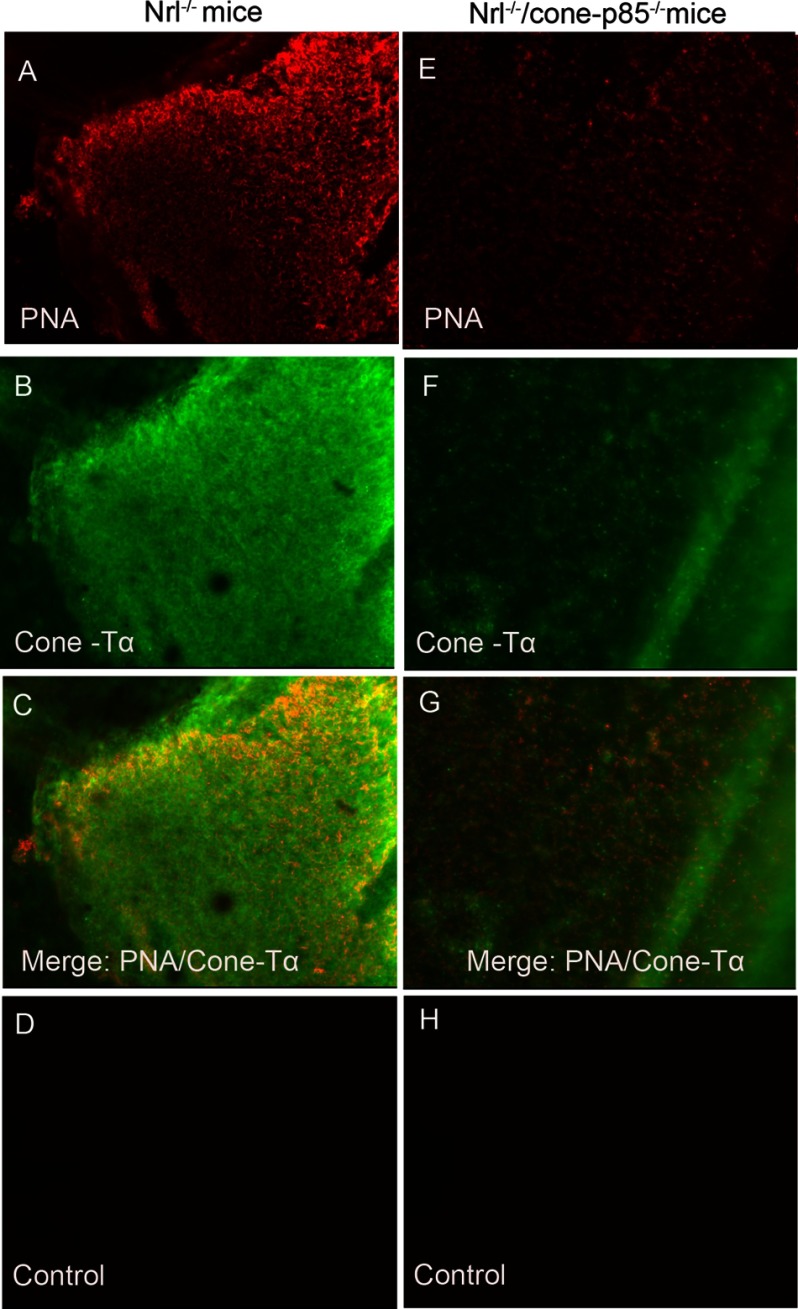

To test if the deletion of p85α triggers cone cell death in Nrl−/− mouse retinas, we performed lectin cytochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of whole retinal flat mounts using PNA and anti-cone Tα to label cone outer and inner segments (45), respectively. Fluorescence microscopic analysis of Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− retinal flat mounts indicated that distribution and density of cone photoreceptors was reduced at 1 month age in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− retinas compared with Nrl−/− retinas (Fig. 7, A–H). These experiments suggest that cones may have their own endogenous survival pathway, which is signaling though PI3K.

FIGURE 7.

Increased cone cell death in Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− mice at 1 month of age. PNA (red) and anti-cone-Tα cone (green) immunofluorescence staining of retinal whole mounts from Nrl−/− (A–C) and Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− mice (E–G) is shown. For a control, primary antibodies were omitted (D and H).

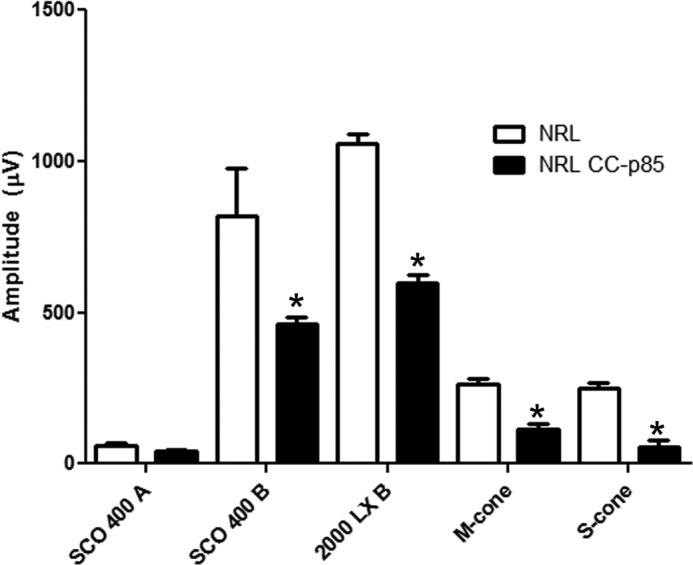

Effect of p85α Deletion on Retinal Function in Nrl−/− Mouse Retinas

Retinal function of Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice was assessed at 1 month of age by ERG. As expected (35), neither Nrl−/− nor Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice exhibited any rod function (Fig. 8). The scotopic b-wave amplitudes were reduced in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice compared with Nrl−/− mice. The amplitude of the maximum light-adapted cone b-wave for the Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice was significantly reduced compared with Nrl−/− mice (Fig. 8). Consistent with these observations, we also found decreased amplitudes of 30 Hz flicker ERG of M- and S-cone responses in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice compared with Nrl−/− mice (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Function of Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− mouse retina. Shown is scotopic a- and b-wave and photopic b-wave ERG analysis of Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/cone-p85α−/− mice at 1 month of age. 30-Hz flicker ERG M- and S-cone responses of Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice are shown. Data are the mean ± S.E. n = 3. *, significance p < .05.

Effect of Deletion of Individual Akt Isoforms on Cone Survival

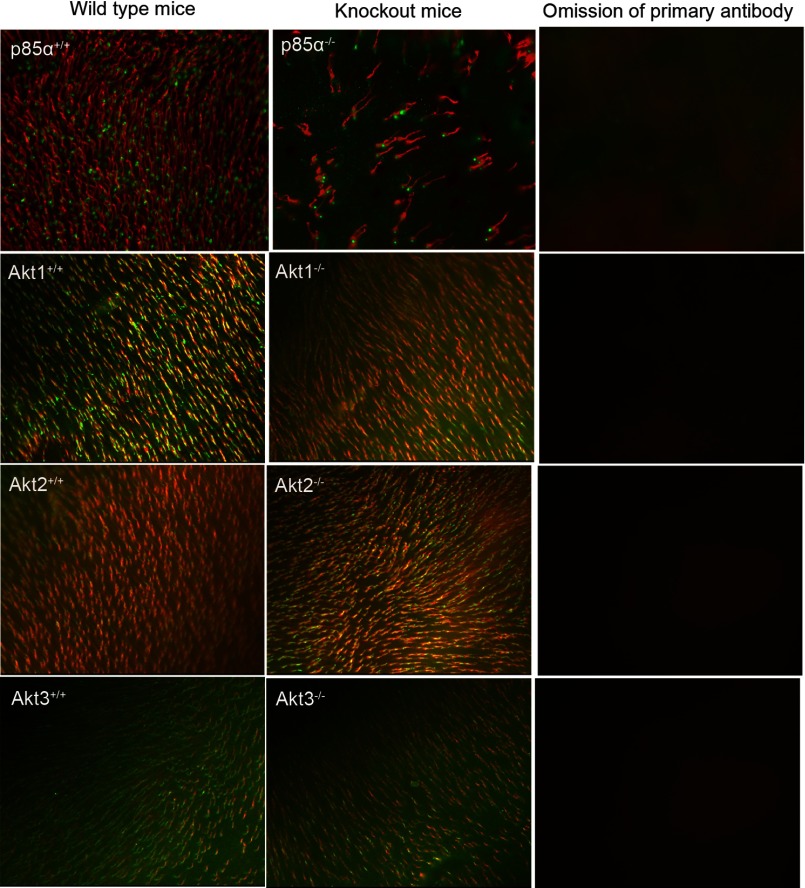

Retinal flat mounts of 6-month-old Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 knock-out mice and their wild type littermates were subjected to lectin cytochemical and immunohistochemical analysis using PNA and anti-cone Tα to label cone outer and inner segments (45), respectively. Fluorescence microscopic analysis of WT and respective Akt isoform knock-out retinal flat mounts indicated that distribution and density of cone photoreceptors was not affected at 6 months of age (Fig. 9). On the other hand, cone p85α−/− mice exhibited a significant loss of cones at 6 months of age compared with WT (Fig. 9). The absence of a phenotype in individual Akt isoforms suggests the existence of a functional redundancy among Akt isoforms in cones.

FIGURE 9.

Flat mounts of cone photoreceptors in wild type, cone-specific p85α−/−, Akt1−/−, Akt2−/−, and Akt3−/− mice. Shown is PNA (red) and anti-cone arrestin (p85α) or anti-cone Tα (green) immunofluorescence staining of retinal whole mounts from WT, knock-out mice (cone specific 85α, global Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3). For a control, primary antibodies were omitted.

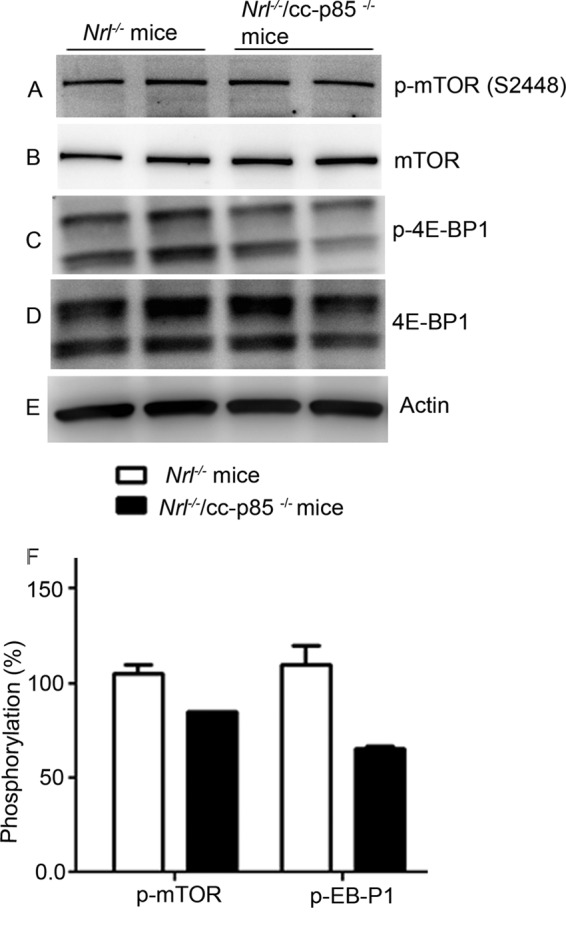

Decreased Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, a Repressor of mRNA Translation

Retinal proteins from Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice were immunoblotted with anti-p-mTOR (Ser-2448), anti-mTOR, anti-p-4E-BP1, and anti-4E-BP1 antibodies. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots was performed in the linear range of detection, and absolute values of the phosphorylation signal on mTOR and 4E-BP1 were normalized to their respective pan-mTOR, pan-4E-BP1, and actin antibodies. We observed a decreased phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and mTOR in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mouse retinas compared with Nrl−/− retinas, although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10.

Phosphorylation status of mTOR and 4E-BP1 in Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mouse retina. Equal amounts of retinal proteins (20 μg) from Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-p-mTOR (Ser-2448), mTOR anti-p-4E-BP1, anti-4E-BP1, and anti-actin antibodies. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots was performed in the linear range of detection, and absolute values of phosphorylation signals on mTOR and 4E-BP1 were normalized to their respective pan-mTOR, pan-4E-BP1, and actin antibodies. The phosphorylation status in Nrl−/− mouse retina was set at 100%.

DISCUSSION

In humans and rodents, cone photoreceptors constitute a small percent (3–5%) of total retinal photoreceptors (16, 17). Technically, it is challenging to study cone-specific expression of a particular protein common for both rod and cone photoreceptors in the rod-dominant retina. To determine the existence of a functional IR signaling survival pathway in cones, we took advantage of pure-cone retinas of the neural retina leucine zipper (Nrl) knock-out mice (35). Mice lacking the transcription factor Nrl experience a block in the differentiation of rod precursor cells, resulting in retinas containing a single class of photoreceptors that are indistinguishable from authentic cones on the basis of a number of criteria (35, 46–48). Although the retinas of Nrl−/− mice experience age-related changes after 3 months of age, studies in young animals provide a powerful approach to understanding cone cell function in a normally rod-dominant retina. These mice will serve as a valuable tool to generate double knock-out mice and have been used in several studies to define the functional aspects of a protein(s) in cones (46, 47, 49).

Immunoblot analysis of IR signaling proteins in POS from Nrl−/− retinas clearly indicate the expression of these proteins. Our immunohistochemical studies on Nrl−/− retinas further support our immunoblot analysis. Consistent with the expression of IR in POS in Nrl−/− retinas, we also found the expression of IR in cone dominant ground squirrel POS. To further substantiate the existence of the IR signaling pathway in cone photoreceptors, we analyzed lysates of 661W cells (a cone-like transformed cell line) for expression of IR and its downstream effectors by immunoblotting analysis. This cell line has previously been used to study the multiple death pathways in cone photoreceptors (50). The results indicate that 661W cells express almost all IR signaling proteins. These experiments provide evidence for the existence of an IR signaling pathway in cone photoreceptors in vivo and in vitro. One of the novel findings we observed in this study is that the expression levels of IR signaling proteins (IR, IGF1-R, mTOR, p110α, p85α, PTP1B, p70S6K, and Src) in cone dominant retinas were significantly higher compared with the rod dominant retina. These studies further confirm that increased levels of IR signaling proteins in cones may play an important role in cone survival.

Even though age-related cone degeneration occurred in cone-p85α−/− mice, rod viability was not affected in these mice (30). These results suggest that cone cell death due to the absence of p85α could not be rescued by surrounding healthy rods and their putative trophic survival signals. Rod-derived cone viability factor (RdCVF) has been shown to protect cones in the absence of rods (36). On the other hand, insulin can delay the death of cones in mouse models of RP lacking rods (29). These studies led to the hypothesis that survival signals to cones from either rods or within cones mediate their neuroprotective effects through a cone-PI3K-dependent manner. In either case, our studies suggest the importance of p85α on cone cell survival. It is well known that mutations of rod-specific genes that lead to rod malfunction and death also compromise cone function and survival, eventually resulting in complete blindness (19, 44, 51–53). Even though the underlying genetic mutations of RP are known, the particular cone survival pathways affected, ultimately leading to cone photoreceptor death, are not well known. In the current study ablation of cone p85α under a rhodopsin mutant background (VPP) exacerbates a decrease in cone function compared with rhodopsin mutant mice with a competent p85α. Interestingly, the rhodopsin mutant mice have rod function, presumably making rod-derived and other putative trophic survival factors for cone survival, but fail to prevent the loss of cone function in the absence of p85α. These observations suggest that rod-derived cone survival factors may be signaled through cone PI3K.

Systematic administration of insulin has been shown to delay the death of cones in mouse models of RP lacking rods (29). These observations suggest that cones may have their own endogenous neuroprotective pathway(s) in addition to rod-derived cone viability factor (36) and other rod-derived trophic factors. To test this hypothesis, we generated a Nrl−/−/p85α−/− double knock-out mouse line and examined the effect of p85α on cone function and cone cell survival. At one month of age, the Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice show a significant decrease in cone function compared with Nrl−/− mice, and this functional loss is due to significant cone cell death. If cones do not have an endogenous neuroprotective pathway, one would expect to observe no difference in the cone function and cone cell death between Nrl−/− and Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mice. The rapid cone degeneration in the absence of cone p85α under Nrl−/− background suggests that cones may have their own endogenous survival signals in addition to cone survival factors communicated by rods.

Our study suggests several differences between rods and cones. The expression levels of IR signaling proteins are significantly higher in cones compared with rods. Our current and earlier functional studies on PI3K suggest that this pathway is essential for cone survival (30), and we observed a functional redundancy in rod-specific p85α−/− mice (31). The PKB/Akt family consists of three members, PKBα/Akt1, PKBβ/Akt2, and PKBγ/Akt3, which are products of three separate genes located on distinct chromosomes (54–59). The isoforms share a high degree of structural and sequence conservation through evolution (54–59). Akt1 and Akt2 are ubiquitously expressed (60), whereas Akt3 is found primarily in brain with little expression in heart, kidney, and placenta (54). We found that all three Akt isoforms are expressed in both rods (61) and cones. In this study, deletion of individual Akt isoforms, Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3, did not show any retinal phenotype, suggesting a functional redundancy exists among Akt isoforms. Surprisingly, in rods, Akt2 deletion has both a functional and a structural phenotype, enforcing a non-redundant role of Akt2 in rod photoreceptor function (34).

mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase that plays a critical role in coordinating cell growth, cell proliferation, cell motility, cell survival, protein synthesis, and transcription (62) with growth factor inputs as well as cellular nutrient and energy status (63–66). The activation of mTOR is positively regulated by Akt (67). mTOR is phosphorylated at serine 2448 via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (68). Two major substrates for mTOR include the serine/threonine kinase p70S6K and the 4E-binding protein 4E-BP1, both of which have been implicated in the control of protein translation (67). The phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 by mTOR results in the release of the cap-binding protein eIF-4E, which is held inactive when bound to hypophosphorylated 4E-BP1, allowing eIF-4E to form an initiation factor complex (69). In our study we found a decreased phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in Nrl−/−/p85α−/− mouse retinas compared with Nrl−/− mouse retinas. 4E-BP1 is a repressor of mRNA translation, and it has been previously shown to be phosphorylated and inactivated by PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (70). Postmitotic neurons also require protein synthesis for survival (71). Consistent with this idea is that stimulation of the insulin/mTOR pathway has been shown to delay cone cell death in a mouse model of RP (29). Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans identified the mammalian equivalents of insulin and PI3K as modulators of longevity, probability through regulation of metabolism and protein synthesis (72, 73). Insulin receptor activation has also been shown to promote rat retinal neuronal cell survival in a p70S6K-dependent manner (74). These studies suggest that the absence of p85α in cones may lead to cone degeneration, and this could be due to decreased mRNA translation and protein synthesis. Further studies are required to identify the ways to activate the mRNA translation and protein synthesis in retinal degenerative diseases affecting the cones.

Our studies suggest that activation of the IR (or other receptor)/mTOR/PI3K/Akt pathways may have clinical relevance. Age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and RP are retinal diseases that result in loss of cone function and ultimately lead to cone death, resulting in blindness. Our findings may have significance in other chronic neurological diseases such as Parkinson, Huntington, and Alzheimer disease as deficient brain insulin signaling pathway in Alzheimer disease and diabetes has recently been reported (75, 76).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lewis Cantley (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for pan-p85αflox/flox mice, Dr. Anand Swaroop (NEI, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for providing Nrl−/− mice, and Dr. Yun Le (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center (OUHSC), Oklahoma City, OK) for providing cone cre-opsin mice. We thank Dr. Dana Vaughan (University of WI, Oshkosh) for providing ground squirrel retinal tissue. We also thank Dr. Muayyad Al-Ubaidi (OUHSC) for providing the 661W cone cell line. The technical assistance of Dustin Allen and Halie Ferguson was highly acknowledged. We also thank Richard Brush for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants EY016507, EY00871, RR17703, EY12190, and EY021725. This work was also supported by an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc.

- RP

- retinitis pigmentosa

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- PNA

- peanut agglutinin

- IGF-1R

- insulin-like growth factor receptor-1

- PTP1B

- protein-tyrosine phosphatase-IB

- Grb14

- growth factor receptor bound protein-14

- ERG

- electroretinography

- POS

- photoreceptor outer segment.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fliesler S. J., Anderson R. E. (1983) in Progress in Lipid Research (Holman R.T., ed) pp. 79–131, Pergamon Press, Inc., Elmsford, NY: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou F., Qu L., Lv K., Chen H., Liu J., Liu X., Li Y., Sun X. (2011) Luteolin protects against reactive oxygen species-mediated cell death induced by zinc toxicity via the PI3K-Akt-NF-κB-ERK-dependent pathway. J. Neurosci. Res. 89, 1859–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng Z., Tseng Y., White M. F. (2010) Insulin signaling meets mitochondria in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21, 589–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao Y., Dong C., Yin J., Shen J., Tian J., Li C. (2012) Neuroprotective effect of fucoidan on H2O2-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells via activation of PI3K/Akt pathway. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 32, 523–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanghera K. P., Mathalone N., Baigi R., Panov E., Wang D., Zhao X., Hsu H., Wang H., Tropepe V., Ward M., Boyd S. R. (2011) The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway mediates retinal progenitor cell survival under hypoxic and superoxide stress. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 47, 145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Havrankova J., Roth J., Brownstein M. (1978) Insulin receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system of the rat. Nature 272, 827–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baskin D. G., Figlewicz Lattemann D., Seeley R. J., Woods S. C., Porte D., Jr., Schwartz M. W. (1999) Insulin and leptin. Dual adiposity signals to the brain for the regulation of food intake and body weight. Brain Res. 848, 114–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwartz M. W., Sipols A. J., Marks J. L., Sanacora G., White J. D., Scheurink A., Kahn S. E., Baskin D. G., Woods S. C., Figlewicz D. P. (1992) Inhibition of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y gene expression by insulin. Endocrinology 130, 3608–3616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heidenreich K. A. (1993) Insulin and IGF-I receptor signaling in cultured neurons. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 692, 72–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robinson L. J., Leitner W., Draznin B., Heidenreich K. A. (1994) Evidence that p21ras mediates the neurotrophic effects of insulin and insulin-like growth factor I in chick forebrain neurons. Endocrinology 135, 2568–2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takahashi M., Yamada T., Tooyama I., Moroo I., Kimura H., Yamamoto T., Okada H. (1996) Insulin receptor mRNA in the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 204, 201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frölich L., Blum-Degen D., Bernstein H. G., Engelsberger S., Humrich J., Laufer S., Muschner D., Thalheimer A., Türk A., Hoyer S., Zöchling R., Boissl K. W., Jellinger K., Riederer P. (1998) Brain insulin and insulin receptors in aging and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J. Neural. Transm. 105, 423–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barber A. J., Nakamura M., Wolpert E. B., Reiter C. E., Seigel G. M., Antonetti D. A., Gardner T. W. (2001) Insulin rescues retinal neurons from apoptosis by a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-mediated mechanism that reduces the activation of caspase-3. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32814–32821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brüning J. C., Gautam D., Burks D. J., Gillette J., Schubert M., Orban P. C., Klein R., Krone W., Müller-Wieland D., Kahn C. R. (2000) Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science 289, 2122–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rajala A., Tanito M., Le Y. Z., Kahn C. R., Rajala R. V. (2008) Loss of neuroprotective survival signal in mice lacking insulin receptor gene in rod photoreceptor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19781–19792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carter-Dawson L. D., LaVail M. M. (1979) Rods and cones in the mouse retina. II. Autoradiographic analysis of cell generation using tritiated thymidine. J. Comp. Neurol. 188, 263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carter-Dawson L. D., LaVail M. M. (1979) Rods and cones in the mouse retina. I. Structural analysis using light and electron microscopy. J. Comp. Neurol. 188, 245–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adler R., Curcio C., Hicks D., Price D., Wong F. (1999) Cell death in age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 5, 31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stone E. M., Braun T. A., Russell S. R., Kuehn M. H., Lotery A. J., Moore P. A., Eastman C. G., Casavant T. L., Sheffield V. C. (2004) Missense variations in the fibulin 5 gene and age-related macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shen J., Yang X., Dong A., Petters R. M., Peng Y. W., Wong F., Campochiaro P. A. (2005) Oxidative damage is a potential cause of cone cell death in retinitis pigmentosa. J. Cell Physiol. 203, 457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cho N. C., Poulsen G. L., Ver Hoeve J. N., Nork T. M. (2000) Selective loss of S-cones in diabetic retinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 118, 1393–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nork T. M. (2000) Acquired color vision loss and a possible mechanism of ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 98, 331–363 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamel C. P. (2007) Cone rod dystrophies. Orphanet. J. Rare. Dis. 2, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kellner U., Foerster M. H. (1993) Pattern of dysfunction in progressive cone dystrophies. An extended classification. Ger. J. Ophthalmol. 2, 170–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kohl S. (2009) Genetic causes of hereditary cone and cone-rod dystrophies. Ophthalmologe 106, 109–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Punzo C., Xiong W., Cepko C. L. (2012) Loss of daylight vision in retinal degeneration. Are oxidative stress and metabolic dysregulation to blame? J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1642–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park S. H., Park J. W., Park S. J., Kim K. Y., Chung J. W., Chun M. H., Oh S. J. (2003) Apoptotic death of photoreceptors in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat retina. Diabetologia 46, 1260–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reiter C. E., Wu X., Sandirasegarane L., Nakamura M., Gilbert K. A., Singh R. S., Fort P. E., Antonetti D. A., Gardner T. W. (2006) Diabetes reduces basal retinal insulin receptor signaling. Reversal with systemic and local insulin. Diabetes 55, 1148–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Punzo C., Kornacker K., Cepko C. L. (2009) Stimulation of the insulin/mTOR pathway delays cone death in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 44–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ivanovic I., Anderson R. E., Le Y. Z., Fliesler S. J., Sherry D. M., Rajala R. V. (2011) Deletion of the p85α regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in cone photoreceptor cells results in cone photoreceptor degeneration. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 3775–3783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ivanovic I., Allen D. T., Dighe R., Le Y. Z., Anderson R. E., Rajala R. V. (2011) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in retinal rod photoreceptors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52, 6355–6362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Linton J. D., Holzhausen L. C., Babai N., Song H., Miyagishima K. J., Stearns G. W., Lindsay K., Wei J., Chertov A. O., Peters T. A., Caffe R., Pluk H., Seeliger M. W., Tanimoto N., Fong K., Bolton L., Kuok D. L., Sweet I. R., Bartoletti T. M., Radu R. A., Travis G. H., Zagotta W. N., Townes-Anderson E., Parker E., Van der Zee C. E., Sampath A. P., Sokolov M., Thoreson W. B., Hurley J. B. (2010) Flow of energy in the outer retina in darkness and in light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8599–8604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okawa H., Sampath A. P., Laughlin S. B., Fain G. L. (2008) ATP consumption by mammalian rod photoreceptors in darkness and in light. Curr. Biol. 18, 1917–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li G., Anderson R. E., Tomita H., Adler R., Liu X., Zack D. J., Rajala R. V. (2007) Nonredundant role of Akt2 for neuroprotection of rod photoreceptor cells from light-induced cell death. J. Neurosci. 27, 203–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mears A. J., Kondo M., Swain P. K., Takada Y., Bush R. A., Saunders T. L., Sieving P. A., Swaroop A. (2001) Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat. Genet. 29, 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang Y., Mohand-Said S., Danan A., Simonutti M., Fontaine V., Clerin E., Picaud S., Léveillard T., Sahel J. A. (2009) Functional cone rescue by RdCVF protein in a dominant model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Ther. 17, 787–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tan E., Ding X. Q., Saadi A., Agarwal N., Naash M. I., Al-Ubaidi M. R. (2004) Expression of cone-photoreceptor-specific antigens in a cell line derived from retinal tumors in transgenic mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 764–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Luo J., McMullen J. R., Sobkiw C. L., Zhang L., Dorfman A. L., Sherwood M. C., Logsdon M. N., Horner J. W., DePinho R. A., Izumo S., Cantley L. C. (2005) Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates heart size and physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9491–9502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Le Y. Z., Ash J. D., Al-Ubaidi M. R., Chen Y., Ma J. X., Anderson R. E. (2004) Targeted expression of Cre recombinase to cone photoreceptors in transgenic mice. Mol. Vis. 10, 1011–1018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kryger Z., Galli-Resta L., Jacobs G. H., Reese B. E. (1998) The topography of rod and cone photoreceptors in the retina of the ground squirrel. Vis. Neurosci. 15, 685–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stuck M. W., Conley S. M., Naash M. I. (2012) Defects in the outer limiting membrane are associated with rosette development in the Nrl−/− retina. PLoS ONE 7, e32484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Elias R. V., Sezate S. S., Cao W., McGinnis J. F. (2004) Temporal kinetics of the light/dark translocation and compartmentation of arrestin and α-transducin in mouse photoreceptor cells. Mol. Vis. 10, 672–681 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Majewski N., Nogueira V., Bhaskar P., Coy P. E., Skeen J. E., Gottlob K., Chandel N. S., Thompson C. B., Robey R. B., Hay N. (2004) Hexokinase-mitochondria interaction mediated by Akt is required to inhibit apoptosis in the presence or absence of Bax and Bak. Mol. Cell 16, 819–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Naash M. I., Hollyfield J. G., al-Ubaidi M. R., Baehr W. (1993) Simulation of human autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa in transgenic mice expressing a mutated murine opsin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5499–5503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nikonov S. S., Brown B. M., Davis J. A., Zuniga F. I., Bragin A., Pugh E. N., Jr., Craft C. M. (2008) Mouse cones require an arrestin for normal inactivation of phototransduction. Neuron 59, 462–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhu X., Brown B., Li A., Mears A. J., Swaroop A., Craft C. M. (2003) GRK1-dependent phosphorylation of S and M opsins and their binding to cone arrestin during cone phototransduction in the mouse retina. J. Neurosci. 23, 6152–6160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nikonov S. S., Daniele L. L., Zhu X., Craft C. M., Swaroop A., Pugh E. N., Jr. (2005) Photoreceptors of Nrl−/− mice coexpress functional S- and M-cone opsins having distinct inactivation mechanisms. J. Gen. Physiol. 125, 287–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Daniele L. L., Lillo C., Lyubarsky A. L., Nikonov S. S., Philp N., Mears A. J., Swaroop A., Williams D. S., Pugh E. N., Jr. (2005) Cone-like morphological, molecular, and electrophysiological features of the photoreceptors of the Nrl knockout mouse. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 2156–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feathers K. L., Lyubarsky A. L., Khan N. W., Teofilo K., Swaroop A., Williams D. S., Pugh E. N., Jr., Thompson D. A. (2008) Nrl-knockout mice deficient in Rpe65 fail to synthesize 11-cis-retinal and cone outer segments. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 1126–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gómez-Vicente V., Donovan M., Cotter T. G. (2005) Multiple death pathways in retina-derived 661W cells following growth factor deprivation. Cross-talk between caspases and calpains. Cell Death Differ. 12, 796–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bowes C., Li T., Danciger M., Baxter L. C., Applebury M. L., Farber D. B. (1990) Retinal degeneration in the rd mouse is caused by a defect in the β subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase. Nature 347, 677–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lem J., Krasnoperova N. V., Calvert P. D., Kosaras B., Cameron D. A., Nicolò M., Makino C. L., Sidman R. L. (1999) Morphological, physiological, and biochemical changes in rhodopsin knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 736–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tsang S. H., Gouras P., Yamashita C. K., Kjeldbye H., Fisher J., Farber D. B., Goff S. P. (1996) Retinal degeneration in mice lacking the γ subunit of the rod cGMP phosphodiesterase. Science 272, 1026–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Masure S., Haefner B., Wesselink J. J., Hoefnagel E., Mortier E., Verhasselt P., Tuytelaars A., Gordon R., Richardson A. (1999) Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of the human serine/threonine kinase Akt-3. Eur. J. Biochem. 265, 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Staal S. P. (1987) Molecular cloning of the akt oncogene and its human homologues AKT1 and AKT2. Amplification of AKT1 in a primary human gastric adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 5034–5037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Brodbeck D., Cron P., Hemmings B. A. (1999) A human protein kinase Bγ with regulatory phosphorylation sites in the activation loop and in the C-terminal hydrophobic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 9133–9136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jones P. F., Jakubowicz T., Hemmings B. A. (1991) Molecular cloning of a second form of rac protein kinase. Cell Regul. 2, 1001–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jones P. F., Jakubowicz T., Pitossi F. J., Maurer F., Hemmings B. A. (1991) Molecular cloning and identification of a serine/threonine protein kinase of the second-messenger subfamily. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 4171–4175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nakatani K., Sakaue H., Thompson D. A., Weigel R. J., Roth R. A. (1999) Identification of a human Akt3 (protein kinase B γ) which contains the regulatory serine phosphorylation site. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 257, 906–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Coffer P. J., Woodgett J. R. (1991) Molecular cloning and characterisation of a novel putative protein-serine kinase related to the cAMP-dependent and protein kinase C families. Eur. J. Biochem. 201, 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li G., Rajala A., Wiechmann A. F., Anderson R. E., Rajala R. V. (2008) Activation and membrane binding of retinal protein kinase Bα/Akt1 is regulated through light-dependent generation of phosphoinositides. J. Neurochem. 107, 1382–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hay N., Sonenberg N. (2004) Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 18, 1926–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gingras A. C., Raught B., Sonenberg N. (2001) Regulation of translation initiation by FRAP/mTOR. Genes Dev. 15, 807–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dennis P. B., Jaeschke A., Saitoh M., Fowler B., Kozma S. C., Thomas G. (2001) Mammalian TOR. A homeostatic ATP sensor. Science 294, 1102–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sarbassov D. D., Ali S. M., Sabatini D. M. (2005) Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17, 596–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sengupta S., Peterson T. R., Sabatini D. M. (2010) Regulation of the mTOR complex 1 pathway by nutrients, growth factors, and stress. Mol. Cell 40, 310–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schmelzle T., Hall M. N. (2000) TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell 103, 253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chiang G. G., Abraham R. T. (2005) Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 25485–25490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang X., Proud C. G. (2006) The mTOR pathway in the control of protein synthesis. Physiology 21, 362–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gingras A. C., Kennedy S. G., O'Leary M. A., Sonenberg N., Hay N. (1998) 4E-BP1, a repressor of mRNA translation, is phosphorylated and inactivated by the Akt(PKB) signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 12, 502–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rehen S. K., Neves D. D., Fragel-Madeira L., Britto L. R., Linden R. (1999) Selective sensitivity of early postmitotic retinal cells to apoptosis induced by inhibition of protein synthesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 4349–4356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Morris J. Z., Tissenbaum H. A., Ruvkun G. (1996) A phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase family member regulating longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 382, 536–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kimura K. D., Tissenbaum H. A., Liu Y., Ruvkun G. (1997) daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 277, 942–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wu X., Reiter C. E., Antonetti D. A., Kimball S. R., Jefferson L. S., Gardner T. W. (2004) Insulin promotes rat retinal neuronal cell survival in a p70S6K-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9167–9175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Liu Y., Liu F., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Gong C. X. (2011) Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J. Pathol. 225, 54–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Deng Y., Li B., Liu Y., Iqbal K., Grundke-Iqbal I., Gong C. X. (2009) Dysregulation of insulin signaling, glucose transporters, O-GlcNAcylation, and phosphorylation of tau and neurofilaments in the brain. Implication for Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 2089–2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]