Background: Prefoldin, a molecular chaperone composed of six subunits, prevents misfolding of newly synthesized nascent polypeptides.

Results: Prefoldin inhibited aggregation of pathogenic Huntingtin and subsequent cell death.

Conclusion: Prefoldin suppressed Huntingtin aggregation at the small oligomer stage.

Significance: Prefoldin plays a role in preventing protein aggregation in Huntington disease.

Keywords: Cell Death, Chaperone Chaperonin, Neurodegeneration, Polyglutamine Disease, Protein Aggregation

Abstract

Huntington disease is caused by cell death after the expansion of polyglutamine (polyQ) tracts longer than ∼40 repeats encoded by exon 1 of the huntingtin (HTT) gene. Prefoldin is a molecular chaperone composed of six subunits, PFD1–6, and prevents misfolding of newly synthesized nascent polypeptides. In this study, we found that knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 disrupted prefoldin formation in HTT-expressing cells, resulting in accumulation of aggregates of a pathogenic form of HTT and in induction of cell death. Dead cells, however, did not contain inclusions of HTT, and analysis by a fluorescence correlation spectroscopy indicated that knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 also increased the size of soluble oligomers of pathogenic HTT in cells. In vitro single molecule observation demonstrated that prefoldin suppressed HTT aggregation at the small oligomer (dimer to tetramer) stage. These results indicate that prefoldin inhibits elongation of large oligomers of pathogenic Htt, thereby inhibiting subsequent inclusion formation, and suggest that soluble oligomers of polyQ-expanded HTT are more toxic than are inclusion to cells.

Introduction

Huntington disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor impairment, involuntary movements (chorea), psychiatric disorders, and dementia (1). Huntington disease is caused by the expansion of a CAG repeat in exon 1 of the huntingtin gene, and resultant polyglutamine (polyQ) tracts longer than ∼40 repeats trigger cell death of affected neurons (2, 3). The conformation of Huntingtin (HTT) protein is altered by the existence of expanded polyQ, leading to oligomerization and aggregation of mutant/pathogenic HTT into β-sheet-rich fibrils, thereby forming large aggregates (inclusion bodies) in affected neurons (4, 5). The monomer of pathogenic HTT protein is assumed to form a conformation rich in random coils or α-helices and to turn β-sheets (6, 7). Oligomerized pathogenic HTT, however, tends to form fibrils and inclusions. Although the inclusion body of pathogenic HTT has long been thought to be a causative factor for Huntington disease, accumulating evidence suggests that formation of pathogenic HTT inclusion is not correlated with neuronal cell death (8, 9). It is therefore thought that the inclusion body acts as a deposit of pathogenic HTT to decrease the risk of neuronal cell death.

Many molecular chaperones associate with polyglutamine proteins to inhibit formation of aggregations in test tubes, cell lines, and model animals (10–14). Purified heat shock proteins HSP70 and HSP40 (Hdj1) suppress the toxicity of polyQ-expanded HTT exon 1. These proteins promote formation of nontoxic oligomers of polyQ-expanded HTT, instead of SDS-insoluble amyloid fibrils (15, 16). Furthermore, several groups have reported that overexpression of HSP70/HSP40 chaperones suppresses polyQ-induced neurotoxicity in animal models of polyglutamine disease (17–19) and that chaperonin CCT2 (chaperonin-containing TCP-1, also known as TRiC) prevents the toxicity of pathogenic HTT by inhibiting formation of toxic oligomers through interaction with soluble oligomers (20–22). It is therefore possible that other chaperones also modify aggregation of pathogenic HTT.

Prefoldin is a molecular chaperone found in eukarya and archaea domains and assists folding of a newly synthesized polypeptide chain in cooperation with HSP70/HSP40 and with CCT in the cytosol (23, 24). Prefoldin is composed of six subunits, PFD1–6, and it forms a “jellyfish-like” structure (25) and binds to a substrate with its tentacle-like structures (26). Although distal end regions of prefoldin's tentacles are hydrophobic and are thought to be accessible with hydrophobic surfaces of the substrate (25), little is known about the mechanisms by which prefoldin recognizes substrates. Prefoldin binds to newly synthesized nascent polypeptides such as actin and tubulin in the cytosol to prevent their misfolding (24, 27). Recent studies have shown that after capturing newly synthesized polypeptide chains, prefoldin transports them to CCT to assist with folding polypeptides (23, 24, 28). Furthermore, Sakono et al. (29) have reported that archaeal prefoldin forms soluble amyloid β oligomers but not fibrils in vitro, suggesting that prefoldin plays a modifier role against the toxicity of misfolded proteins, including proteins that cause neurodegenerative diseases.

In this study, we examined the effect of human prefoldin on the formation and toxicity of pathogenic HTT aggregation using in vitro and in vivo systems and found that prefoldin prevents HTT neurotoxicity by inhibiting its aggregation at a small oligomer stage. We discuss prefoldin-dependent protection mechanisms of neuronal cells against the toxicity of pathogenic HTT.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

pEGFP-C1 and pcDNA3 were obtained from Clontech and Invitrogen, respectively. Expression vectors for EGFP-Q11 and EGFP-Q72 and for Htt-exon 1 fused with GFP were described previously (21, 30). Htt-polyQ-GFP regions were recloned into ptet-CMV minimal containing minimal CMV promoter. pGEXGST-myc-Htt Gln-23/Gln-53 exon 1 (15, 31) was used for expression of GST-Htt proteins in Escherichia coli. For fluorescence labeling of GST-HTT exon 1, all of the cysteine residues present in GST were replaced with serine as described previously (20).

Analyses of Aggregate-containing Cells and Cell Death

Neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% calf serum. Cells were cultured on a 3.5-cm glass bottom dish (Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan) coated with type IV collagen (CellMatrix, Nitta Gelatin, Osaka, Japan). Nucleotide sequences of the upper and lower strands for siRNA were as follows: 5′-GGAGCAUGUGCUUAUUGAUGU-3′ and 5′-AUCAAUAAGCACAUGCUCCAC-3′ for PFD2 and 5′-GGAGCGGACUGUCAAAGAATT-3′ and 5′-UUCUUUGACAGUCCGCUCCTT-3′ for PFD5. Neuro-2a cells were first transfected with PFD2 siRNA and PFD5 siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). AllStars negative control siRNA (Qiagen) was used as a nonspecific negative control (Qiagen). Twenty four h after transfection, cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of an expression vector for EGFP-polyQ or HTT-polyQ-GFP and induced to undergo neuronal cell differentiation by addition of 5 mm dibutyryl cAMP for 48 h. After transfection of polyQ expression vectors into Neuro-2a cells, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 0 or 5 mm dibutyryl cAMP and 2 μg/ml propidium iodide. At 48 h after transfection, cell images were taken by using Biozero BZ-8000 (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) with Plan-Apo 20 × 0.75 NA (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Propidium iodide-positive cells were counted as dead cells.

Neuro-2a cells were transfected with 5 and 10 ng of expression vectors for six prefoldin subunits PFD1–6 using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. Twenty four h after transfection, cells were transfected with an expression vector for HTT23-polyQ-GFP or HTT78-polyQ-GFP. Neuronal differentiation of Neuro-2a cells was then carried out as described above.

Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted from cells after incubation of cells with a Hepes buffer containing 40 mm Hepes-NaOH (pH 7.4), 120 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitors and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-PFD1 (PA006499, Sigma), anti-PFD2 and anti-PFD3 (K-13, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-PFD4 and anti-PFD5 (S-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-PFD6 (AP2836a, Abgent, San Diego), and anti-GAPDH (MAB374, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) antibodies. Proteins were then reacted with an IRDye800- or Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized by using an infrared imaging system (Odyssey, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Anti-PFD2 and anti-PFD4 antibodies were established by injection of GST-PFD2 and GST-PFD4, respectively, into rabbits. The anti-PFD2 antibody was purified from rabbit serum, and serum from GST-PFD4-injected rabbits was used as the anti-PFD4 antibody.

Glycerol Density Gradient Centrifugation to Separate the Prefoldin Complex

Neuro-2a cells in a 10-cm dish were transfected with 240 μmol of siRNAs targeting PFD2 and PFD5 and with nonspecific siRNA. At 48 h after transfection, proteins were extracted from cells in a Hepes buffer and separated by a glycerol density gradient centrifugation at 40,000 rpm for 16 h at 4 °C using an SW41 rotor. After samples had been fractionated into 22 fractions, proteins in fractions were precipitated with acetone at −80 °C for 1 h, dissolved in an SDS buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 1% SDS, 2% β-mercaptoethanol, and 8.7% glycerol, and subjected to Western blotting or Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining on 15% SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels. Aldolase (160 kDa), bovine serum albumin (BSA) (56 kDa), and RNase A (13 kDa) were used as molecular weight markers. When differentiated Neuro-2a cells were used, proteins were separated on 7.5% SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels, and Native Mark (Invitrogen) was used as molecular weight markers.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Neuro-2a cells were cultured on coverslips and transfected with an expression vector for Htt-polyQ-EGFP. At 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 37 °C for 10 min for staining PFD2, PFD5, and GAPDH or with methanol at −20 °C for 5 min for staining CCT and HSC70. After treatment of cells with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min, cells were incubated with a blocking buffer containing 5% calf serum, 20% glycerol, and 0.02% Triton X-100 at 4 °C for 16 h. Cells were stained with anti-PFD2 (1:100), anti-PFD5 (1:50), anti-HSC70 (1:100, SPA-815, StressGen, Farmingdale, NY), anti-CCT (1:100, sc-47717, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-GFP (1:100, JL-8, MBL, Nagoya, Japan) antibodies and then reacted with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-rat, or anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:100, Invitrogen). Images were observed using LSM510 META (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with Plan-Apo ×63/1.4 differential interference contrast. An anti-PFD5 antibody for immunofluorescence detection was developed by us after immunization of rabbits with recombinant GST-PFD5 and purified from serum through an affinity column with GST-PFD5.

Filter Trap Assay of Cell Lysates

At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors and sonicated using a water bath-type sonicator at 4 °C for 5 min. Lysates were diluted with 1% SDS-PBS, boiled for 10 min, and filtrated through a cellulose acetate membrane (0.2 μm) using a dot blotter (Bio-dot SF, Bio-Rad). The membrane was incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS overnight and reacted with a mouse anti-GFP antibody (JL-8). The membrane was then reacted with an Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated secondary antibody, and proteins on the membrane were visualized by an Odyssey system.

FCS Analysis

At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed in PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors, sonicated as described above, and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to remove insoluble GFP-polyQ aggregates. Supernatants were then filtrated through a PVDF membrane (0.22 μm) and replaced on a glass bottom 96-well plate and then subjected to FCS analysis using a ConfoCor 2 system with a water immersion objective lens (C-Apochromat 40 × 1.2 NA, Carl Zeiss) at excitation of 488 nm and emission of 505–550 nm. The confocal pinhole diameter was adjusted to 70 μm, and fluorescence was measured 50 times for 10 s at room temperature. Analyses by FCS were performed as described previously (21).

Protein Purification

GST-fused with HTT exon 1 (GST-HTT23Q and GST-HTT53Q) were expressed in E. coli (BL21DE3) and purified as described previously (32). Human prefoldin (PFD) was assembled from six individual subunits of PFD that had been expressed in and purified from E. coli (BL21DE3) as described previously (33).

Filter Trap Assay of in Vitro Aggregation

HTT protein was prepared by digestion of GST-HTT with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) to cleave off GST and reacted with human PFD or with BSA as a negative control in a buffer A containing 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA at 30 °C for 13 h as described previously (15). Reaction mixtures were then filtrated through a cellulose acetate membrane using a dot blotter and washed three times with TBST (0.05% Tween 20 in TBS). After blocking the membrane with 5% skim milk in TBST, the membrane was incubated with a mouse anti-c-MYC antibody (1:1000, 9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and then with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:2000, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Proteins were visualized using an ECL Plus blotting detection system (GE Healthcare).

Electron Microscopy

HTT protein samples were diluted 10-fold with distilled water and placed on a carbon-coated copper grid and air-dried. After negative staining of samples with uranyl acetate, images were taken with an excitation voltage of 100 kV using a JEM-1011 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

TIRFM Single Particle Analysis of Aggregation

A unique cysteine residue on GST-HTTQ23 or GST-HTTQ53 was labeled with a 10-fold molar excess of Alexa Fluor 488-maleimide (Invitrogen) in a labeling buffer containing 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, and 10% glycerol for 4 h at 4 °C. Excess free dye was removed by a NAP5 column (GE Healthcare), and a typical ratio of GST-HTT-labeled dye was 1:0.7. After addition of PreScission protease to the mixture, Alexa Fluor 488-labeled GST-HTTQ23/53 (2.5 μm) was incubated with human PFD (2.5 μm) at 30 °C for 13 h. Samples were then diluted 3000-fold and analyzed by TIRFM (34–36). Alexa Fluor 488-labeled proteins were illuminated with a blue solid-state laser (11.8 milliwatt, 488 nm, Coherent). The fluorescence emission from the specimen was collected with an oil-immersion microscope objective (1.40 NA, ×100, PlanApo, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and images were taken using a CCD camera (MC681SPD-R0B0, Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX) coupled with an image intensifier (C8600, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). Fluorescence intensity of the single dye was determined from a distribution of photobleaching unitary step intensities of labeled monomer proteins. The number of HTTQ53 molecules per particle was estimated by dividing initial fluorescence intensities from the single particle by fluorescence intensity of the single dye (37).

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as means ± S.D. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by unpaired Student's t test. For comparison of multiple samples, the Tukey-Kramer test was used.

Ethics Statement

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the protocols were approved by the Committee for Animal Research at Hokkaido University (the permit number 08-0467).

RESULTS

Knockdown of Prefoldin Subunits Causes Disruption of Prefoldin Complex

The prefoldin complex is composed of six subunits (PFD1–6), and these subunits are divided into α-type and β-type subunits based on their secondary structures (25). To examine the role of prefoldin in polyQ/HTT aggregation, we used an siRNA-mediated knockdown system to reduce the expression of prefoldin subunits in cells. Because the prefoldin complex contains two α-type subunits (PFD3 and PFD5) and four β-type subunits (PFD1, PFD2, PFD4, and PFD6), siRNAs targeting PFD5 (α-type subunit) and PFD2 (β-type subunit) were chosen for knockdown. Synthetic PFD2 and PFD5 siRNAs were ectopically transfected into mouse neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells, and the expression levels of PFD2 and PFD5 mRNAs were examined by RT-PCR. The results showed that PFD2 and PFD5 mRNA levels were specifically reduced by their own siRNAs (data not shown). Analysis of prefoldin subunits by Western blotting showed that protein levels of PFD2 and PFD5 in siRNA-transfected cells were decreased to ∼25 and 15%, respectively, of those in nonspecific siRNA-transfected cells (control) (Fig. 1A). In addition to reduced levels of PFD2 and PFD5, protein expression levels of other subunits were also reduced, although the levels of PFD2 and PFD3 were unaffected by PFD5 siRNA. These results support the notion that the expression levels of prefoldin subunits are mutually regulated at the protein level through the ubiquitin-proteasome system as we reported previously (38). To examine whether knockdown of a prefoldin subunit affects formation of the prefoldin complex, proteins extracted from siRNA-transfected cells were separated on a glycerol density gradient followed by Western blotting with anti-PFD2 and anti-PFD5 antibodies. The prefoldin complex was observed in fractions 8–14 by estimating the fractions compared with those of protein markers, aldolase (160 kDa), BSA (56 kDa), and RNase A (13 kDa), in the gradient. As shown in Fig. 1B, amounts of the prefoldin complex in cells that had been transfected with PFD2 and PFD5 siRNAs were reduced to 12 and 15%, respectively, of that in control cells, indicating that RNAi-mediated knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 effectively reduced formation of the prefoldin complex. As we reported previously (38), these results suggest that free forms of prefoldin subunits are unstable compared with prefoldin subunits in the prefoldin complex.

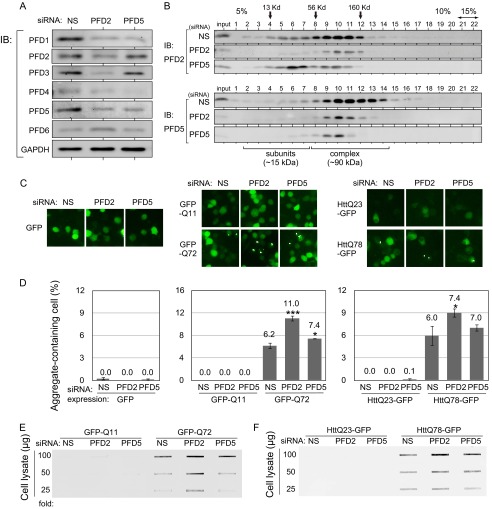

FIGURE 1.

RNAi-mediated knockdown of PFD2 significantly stimulates aggregation of polyQ/HTT in undifferentiated neuronal cells. A, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA (NS) as a control. Proteins were extracted at 48 h after transfection and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against prefoldin subunits. IB, immunoblot. B, cell lysates prepared from siRNA-transfected cells as described in the legend for C were fractionated on a 5–15% glycerol density gradient, and proteins in each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-PFD2 and anti-PFD5 antibodies. C, fluorescent microscopic images of GFP (left panel), GFP-polyQ (middle panel), and HTT-GFP (right panel) expressed in Neuro-2a cells. Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control for 24 h. Cells were then transfected with expression vectors for GFP-Q72, GFP-Q11, HTTQ78-GFP, HTTQ23-GFP, or GFP alone, and cell images were obtained at 48 h after siRNA transfection. D, aggregate-containing cells were counted in cell images of C, and data are shown as mean ± S.D. of three experiments. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 compared with control (NS). E and F, filter-trap assays of SDS-insoluble aggregates of GFP-polyQ (E) and HTT-GFP (F). Cell lysates prepared from siRNA-transfected cells as described in the legend for C were passed through a cellulose acetate membrane and reacted with an anti-GFP antibody.

Knockdown of PFD2, but Not That of PFD5, Strongly Stimulates PolyQ/HTT Aggregation in Undifferentiated Neuro-2a Cells

Because the pathogenic length of expanded polyQ in Huntington disease patients is longer than ∼40 repeats, polyQ tracts containing 11 and 72 repeats were fused with GFP at the N terminus (GFP-Q11 and GFP-Q72) and used as nonpathogenic and pathogenic models, respectively. To examine the effect of prefoldin on polyQ aggregation under pathologically relevant conditions, exon 1 of the huntingtin gene encoding 23 and 78 repeats of glutamine was also fused with GFP at the C terminus (HTTQ23-GFP and HTTQ78-GFP). Undifferentiated Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control. At 24 h after transfection, cells were transfected with expression vectors for GFP-polyQ and HTTQ-GFP, and GFP signals in cells were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope at 48 h after transfection of GFP-polyQ and HTTQ-GFP. As shown in Fig. 1, C and D, PFD2 knockdown increased the numbers of dots in GFP-Q72- and HTTQ78-GFP-expressing cells but not in cells expressing GFP, GFP-Q11, or HTTQ23-GFP. Dots are large protein aggregates and termed as inclusions. Although PFD5 knockdown also slightly but significantly increased GFP-Q72 aggregation, the degree of aggregation was less than that in the case of PFD2 knockdown, and no significant increase in aggregation of HTTQ78-GFP was observed after cells had been knocked down by PFD5 siRNA. Filter-trap assays were also carried out to examine the effects of PFD2 and PFD5 knockdown on aggregation of polyQ and Htt. The results showed that PFD2 knockdown stimulated formation of SDS-insoluble aggregates of GFP-Q72 and HTTQ78-GFP but that the effect of PFD5 knockdown was weak compared with that of PFD2 knockdown (Fig. 1, E and F), which is consistent with the results of microscopic observation. These results indicate that knockdown of PFD2 and that of PDF5, but to a lesser extent, increase aggregation of polyQ-expanded proteins in undifferentiated Neuro-2a cells.

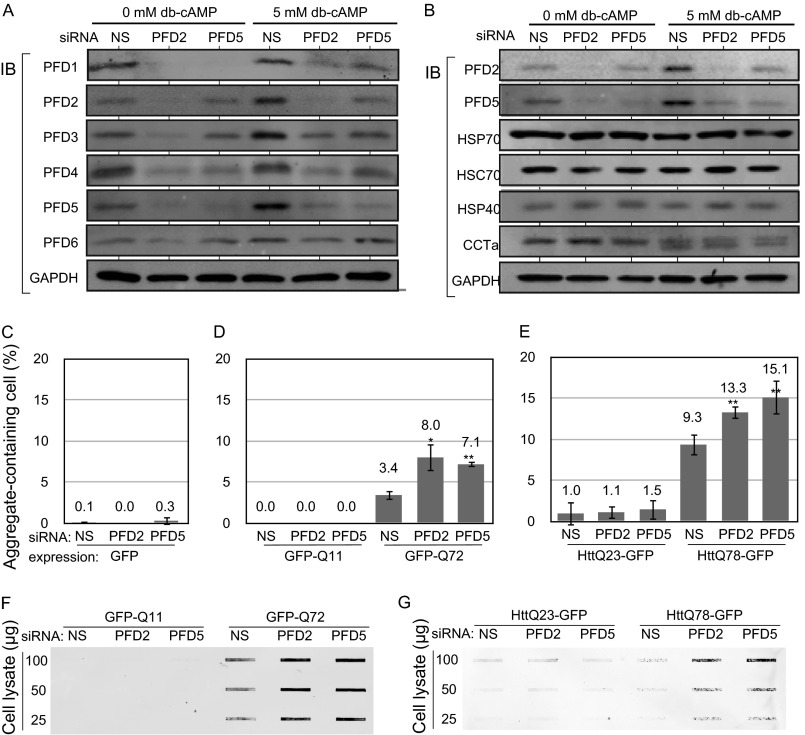

Knockdown of PFD5 and PFD2 Stimulates Toxicity and Aggregation of PolyQ/HTT in Differentiated Neuro-2a Cells

To examine the effect of prefoldin on the toxicity of polyQ-expanded proteins in differentiated neuronal cells, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control. At 24 h after transfection, cells were transfected with expression vectors for healthy and pathogenic forms of GFP-polyQ and HTT-GFP, treated with 5 mm dibutyryl cyclic AMP (Bt2cAMP) at 4 h after transfection, and analyzed at 48 h after transfection of GFP-polyQ and HTT-GFP. It was first confirmed that PFD2 and PFD5 siRNAs effectively decreased expression levels of PFD subunits in differentiated Neuro-2a cells (Fig. 2A). The reduced level of the prefoldin complex in differentiated Neuro-2a cells was also confirmed by glycerol gradient centrifugation (data not shown). Furthermore, as described in the Introduction, various chaperones influence polyQ formation. It is therefore possible that knockdown of prefoldin affects the expression level of chaperones. The expression levels of HSP70, HSC70, HSP40, and CCTα in Neuro-2a cells that had been transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA were examined by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 2B, there are few or no changes in their expression levels both in undifferentiated and differentiated cells. Microscopic observation of GFP-polyQ and HTT-GFP showed that aggregation of pathogenic forms, but not that of healthy forms, of GFP-polyQ and HTT-GFP was significantly enhanced by both knockdown of PFD5 and that of PFD2 (Fig. 2, C–E). Filter-trap assays also showed that knockdown of PFD5 and PFD2 increased the amount of SDS-insoluble aggregates of pathogenic forms of polyQ proteins in differentiated Neuro-2a cells (Fig. 2, F and G).

FIGURE 2.

RNAi-mediated knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 significantly stimulates aggregation of polyQ/HTT in differentiated neuronal cells. A, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control and treated with 5 mm dibutyryl cyclic AMP (db-cAMP) at 4 h after transfection. Proteins were extracted at 48 h after siRNA transfection and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against prefoldin subunits. IB, immunoblot. B, Neuro-2a cells were treated as described in the legend for A. Proteins extracted were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-PFD2, anti-PFD5, anti-HSP70, anti-HSC70, anti-HSP40, anti-CCTα, and anti-GAPDH antibodies. C–E, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control. At 24 h after transfection, cells were transfected with expression vectors for GFP (C), GFP-polyQ (D), and HTT-GFP (E) and treated with 5 mm Bt2cAMP at 4 h after transfection. Aggregate-containing cells were counted at 48 h after transfection of GFP, GFP-polyQ, and HTT-GFP. n = 3. F and G, Neuro-2a cells were treated as described in the legend for C–E, and protein extracts prepared from cells were subjected to filter-trap assays as described under “Experimental Procedures.” NS, nonspecific siRNA.

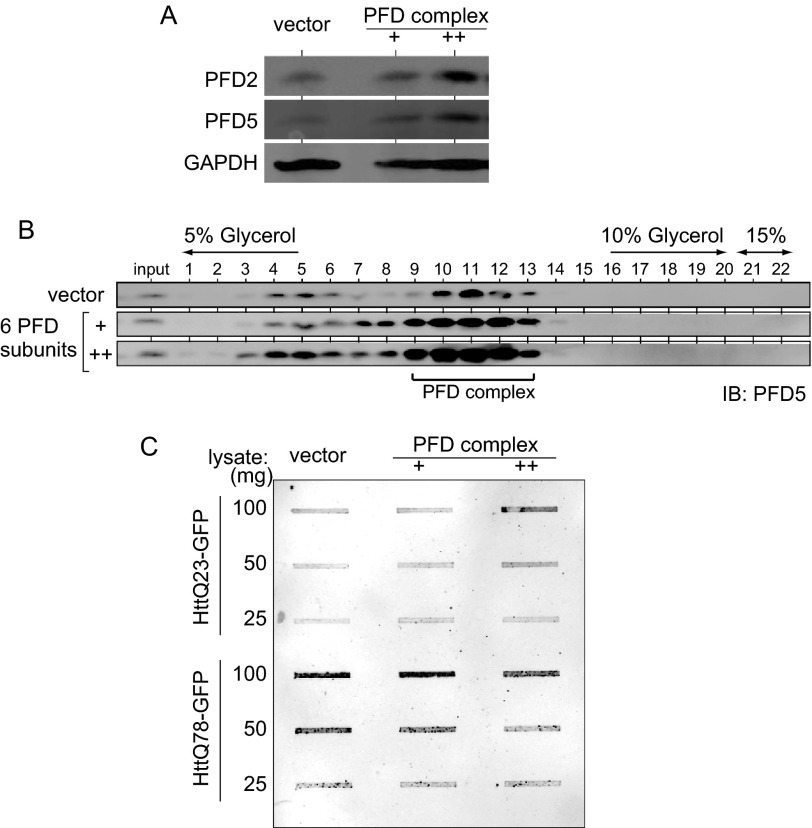

Overexpression of Prefoldin Reduced Aggregation of PolyQ/HTT in Differentiated Neuro-2a Cells

To examine the effect of prefoldin on aggregation of polyQ/HTT in differentiated Neuro-2a cells, Neuro-2a cells were first transfected with two doses of expression vectors for six prefoldin subunits or a control vector and then with those for HTTQ23-GFP and HTTQ78-GFP. Forty eight h after transfection, the expression level of prefoldin and formation of the prefoldin complex in cells were examined by Western blotting and by a glycerol density gradient centrifugation followed by Western blotting, respectively, with anti-PFD2 and anti-PFD5 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, the levels of expression and formation of prefoldin were increased in a dose-dependent manner. Filter-trap assays were then carried out using cell extracts from prefoldin and HTT-GFP-transfected cells. The results showed that overexpressed prefoldin reduced the level of the aggregated form of HTTQ78-GFP but not HTTQ23-GFP in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Overexpression of prefoldin inhibits aggregation of polyQ/HTT. Neuro-2a cells were transfected with 5 and 10 ng of expression vectors for six prefoldin subunits. Twenty four h after transfection, cells were transfected with an expression vector for HTT23-polyQ-GFP or HTT78-polyQ-GFP and differentiated into neuronal cells by addition of Bt2cAMP. Forty eight h after transfection, protein extracts prepared from cells were subjected to filter-trap assays as described under “Experimental Procedures.” IB, immunoblot.

Pathogenic HTT-induced Cell Death Occurs in Cells without Inclusions

Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA and PFD5 siRNA and then transfected with expression vectors for healthy and pathogenic forms of HTT-GFP and differentiated with Bt2cAMP as described above. At 48 h after transfection of HTT-GFP, cells expressing HTTQ23-GFP and HTTQ78-GFP (green) were stained with propidium iodide, and dead cells (propidium iodide staining-positive cells), and dead cells (propidium iodide staining-positive cells) were counted. The results showed that knockdown of PFD2 significantly increased pathogenic HTT-induced cell death in both undifferentiated and differentiated Neuro-2a cells and that PFD5 knockdown significantly stimulated pathogenic HTT-induced cell death only in differentiated Neuro-2a cells (Fig. 4, A and B, respectively). The effects of PFD5 knockdown in differentiated Neuro-2a cells are in contrast to those in undifferentiated Neuro-2a cells in terms of aggregate formation. These results suggest that prefoldin-dependent protective reactions against toxicity of polyQ-expanded proteins are stronger in differentiated neuronal cells than in undifferentiated cells.

FIGURE 4.

Dead cells did not contain HTT inclusions and prefoldin was not co-localized with inclusions. A and B, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA (NS). At 24 h after transfection, cells were transfected with expression vectors for GFP and HTT-GFP and treated with 0 or 5 mm Bt2cAMP (db-cAMP) at 4 h after transfection (A and B, respectively). Cells expressing HTTQ78-GFP (green) were stained with propidium iodide (red) as an indicator of cell death at 48 h after transfection of GFP and HTT-GFP, and the number of propidium iodide-stained cells in GFP-expressing cells was counted (n = 3). More than 92% of cell death occurred without inclusion formation, and knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 resulted in no significant difference in the proportion. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control (NS). C and D, dead cells as shown in A and B were categorized into two groups by GFP signals, inclusion-containing cells and diffusely distributed cells. The numbers of the categorized cells were counted. E, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with an expression vector for HTTQ78-GFP. At 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed, immunostained with anti-PFD2, anti-PFD5, anti-CCTβ, anti-HSC70, and anti-GFP antibodies, and then reacted with an Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-IgG antibody. Cell images were then obtained under a confocal laser microscope. Insets show enlarged views of inclusions. DIC, differential interference contrast.

To assess cell death induced by polyQ aggregation, the number of dead cells containing inclusions in cells shown in Fig. 4, A and B, was counted. As shown in Fig. 4, C and D, more than 90% of both undifferentiated and differentiated forms of dead Neuro-2a cells contained diffusely distributed but not largely aggregated cytosolic HTTQ78 (HTTQ78 inclusion), but the number of HTTQ78 inclusions in undifferentiated cells was slightly larger than that in differentiated cells, indicating that knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 did not significantly affect the number of HTTQ78 inclusions. These results suggest that protective activity of prefoldin against HTTQ78-induced cell death occurs before inclusion formation and that protective activity is stronger in differentiated cells than in undifferentiated cells.

Because prefoldin inhibited cell death in an inclusion formation-independent manner, localization of prefoldin in HTTQ78-GFP-expressing Neuro-2a cells was examined by immunofluorescence staining with anti-PFD2 and PFD5 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 4E, neither PFD2 nor PFD5 (red color) was co-localized with HTTQ78-GFP inclusions (green color), and PFD2 and PFD5 were diffusely distributed in the cytosol (Fig. 4E, panels a and b). The distribution pattern of PFD2 and PFD5 was similar to that of CCT (Fig. 4E, panel c) but was different from that of HSC70, which was co-localized with HTTQ78-GFP inclusions (Fig. 4, panel d). These results suggest that prefoldin prevents formation of pathogenic HTT aggregates by interacting with monomers or soluble oligomers rather than with inclusions, as does CCT but not HSC70.

Size of HTT-soluble Aggregates Is Increased by Prefoldin Knockdown

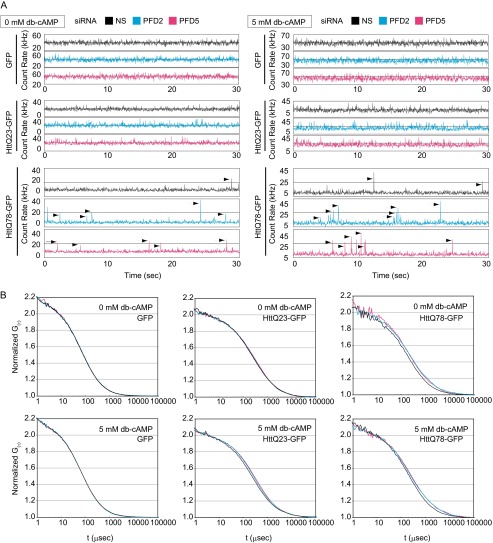

Although the presence of HTT inclusions in the brain of Huntington disease patients is a hallmark of Huntington disease, studies showed that formation of HTT inclusions was not correlated with the degree of cell death, suggesting that polyQ/HTT oligomers, rather than inclusions, are toxic to neurons (8, 9). We therefore examined whether prefoldin affects soluble oligomer formation of pathogenic Htt by using FCS. FCS is a tool for investigating dynamics of fluorescent particles in homogeneous solution or in a living cell with single molecule sensitivity (39, 40). FCS shows fluorescent intensity of fluorescent molecules or particles passing through a detection volume, in which a soluble oligomer is recognized as a single particle with strong intensity. Neuro-2a cells were transfected with siRNA and then with expression vectors for GFP, HTTQ23-GFP, and HTTQ78-GFP and differentiated with Bt2cAMP. Cell lysates prepared from HTT-GFP-expressing cells were then centrifuged to remove insoluble polyQ aggregates such as visible aggregates under a fluorescent microscope.

First, it was found that there are no differences in fluorescence fluctuation and autocorrelation curves obtained from extracts of both undifferentiated and differentiated cells expressing GFP and HTTQ23-GFP and that knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 did not affect waveforms and autocorrelation curves compared with those for cells without knockdown (Fig. 5, A and B). Relatively fine waveforms of fluctuations observed in FCS indicate monomers or dimers of HTTQ23-GFP. Waveforms from HTTQ78-GFP-expressing cells were, however, found to contain spikes with high fluorescence intensities, and these spikes more frequently appeared when expression of PFD2 and PFD5 was knocked down both in undifferentiated and differentiated cells (Fig. 5A). Autocorrelation curves obtained from undifferentiated and differentiated HTT-Q78-expressing cells were also shifted to the right after expression of PFD2 and PFD5 had been knocked down (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that HTTQ78 formed oligomers and that the size of HTTQ78-containing soluble species was increased by PFD knockdown.

FIGURE 5.

Prefoldin-knockdown increased soluble aggregates of polyQ-expanded HTT. Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA (NS) as a control. At 24 h after transfection, cells were transfected with expression vectors for HTTQ78-GFP, HTTQ23-GFP, and GFP and treated with 5 mm Bt2cAMP (db-cAMP) 4 h after transfection. At 48 h after transfection of HTTQ78-GFP, HTTQ23-GFP, and GFP, cell lysates prepared from cells were centrifuged at 17,400 × g, and supernatants were analyzed by FCS. A, count rates of fluorescence fluctuation for 30 s are shown as blue, pink and gray lines from PFD2 siRNA-, PFD5 siRNA-, and nonspecific siRNA-transfected cells, respectively. Arrows indicate signals of strong fluorescence intensity from soluble GFP-HTT aggregates. B, normalized autocorrelation curves of HTT-GFP proteins in FCS are shown.

To estimate the size and proportion of soluble polyQ/HTT species, autocorrelation curves were analyzed by curve fitting using two-component fitting analysis due to the presence of various sizes of soluble Htt aggregates in cell lysates (Table 1). Fast and slow fractions were defined as fractions 1 and 2, respectively. First, it was found both in undifferentiated and differentiated cells that since diffusion time of fraction 1 of HTTQ78-GFP (76 μs) was similar to that of GFP (75–79 μs), fraction 1 contained HTTQ78-GFP monomers and that the diffusion time (106 μs) of fraction 1 of HTTQ23-GFP was slightly longer than that of GFP, suggesting that a major fraction of HTTQ23-GFP forms dimers under the conditions used. Furthermore, diffusion time of fraction 2 of HTTQ23-GFP (660–772 μs) and HTTQ78-GFP (542–851 μs) in undifferentiated and differentiated cells was much longer than that of fraction 1, and the average volume of aggregates in fraction 2 was estimated to be 6.1–11.2-fold larger than that in fraction 1, indicating the existence of HTT-soluble aggregates in fraction 2 from both types of cells.

TABLE 1.

Diffusion time and content of HTT proteins under normal and prefoldin knockdown conditions

Diffusion time (DT) was estimated by curve fitting of the autocorrelation curves of FCS analysis of HTT-GFP at 48 h (mean ± S.D., n = 3). The data of GFP were analyzed by a one-component model, whereas the HTTQ23 and HTTQ78-GFP data were analyzed by a two-component model to provide the best fit. Significance of curve fitting was analyzed by the χ2 test. To accurately estimate the diffusion time and content of the second component (soluble aggregates) at 48 h, the diffusion time of the first component was fixed to the values of monomers that were determined at 24 h.

| Bt2cAMP | Expression | siRNA | Rapid fraction (F1) |

Slow fraction (F2) |

χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DT | Content | DT | Content | ||||

| μs | % | μs | % | ||||

| 0 mm | GFP | NS | 78 ± 5 | 100 | 7.79 ± 4.77 × 10−7 | ||

| 0 mm | GFP | PFD2 | 78 ± 8 | 100 | 9.79 ± 7.82 × 10−7 | ||

| 0 mm | GFP | PFD5 | 79 ± 7 | 100 | 6.75 ± 4.70 × 10−7 | ||

| 5 mm | GFP | NS | 78 ± 9 | 100 | 2.11 ± 5.47 × 10−7 | ||

| 5 mm | GFP | PFD2 | 78 ± 7 | 100 | 2.19 ± 1.08 × 10−7 | ||

| 5 mm | GFP | PFD5 | 75 ± 6 | 100 | 4.81 ± 3.31 × 10−7 | ||

| 0 mm | HTTQ23-GFP | NS | 106 | 59.7 | 698 ± 50 | 40.3 ± 10.5 | 2.00 ± 0.46 × 10−6 |

| 0 mm | HTTQ23-GFP | PFD2 | 106 | 57.0 | 665 ± 38 | 43.0 ± 14.4 | 3.71 ± 0.68 × 10−6 |

| 0 mm | HTTQ23-GFP | PFD5 | 106 | 57.6 | 772 ± 47 | 42.4 ± 13.4 | 2.89 ± 1.45 × 10−6 |

| 0 mm | HTTQ78-GFP | NS | 76 | 58.0 | 558 ± 33 | 42.0 ± 6.7 | 3.68 ± 4.74 × 10−5 |

| 0 mm | HTTQ78-GFP | PFD2 | 76 | 57.5 | 737 ± 75 | 42.5 ± 1.5 | 2.69 ± 0.31 × 10−5 |

| 0 mm | HTTQ78-GFP | PFD5 | 76 | 59.1 | 728 ± 127 | 40.9 ± 6.3 | 1.60 ± 0.88 × 10−5 |

| 5 mm | HTTQ23-GFP | NS | 106 | 55.6 | 650 ± 69 | 44.4 ± 2.4 | 4.75 ± 0.29 × 10−7 |

| 5 mm | HTTQ23-GFP | PFD2 | 106 | 50.9 | 713 ± 59 | 49.1 ± 3.2 | 7.20 ± 0.30 × 10−7 |

| 5 mm | HTTQ23-GFP | PFD5 | 106 | 46.9 | 701 ± 11 | 53.1 ± 6.8 | 0.69 ± 4.29 × 10−6 |

| 5 mm | HTTQ78-GFP | NS | 76 | 54.5 | 542 ± 50 | 45.5 ± 1.7 | 0.59 ± 3.34 × 10−6 |

| 5 mm | HTTQ78-GFP | PFD2 | 76 | 52.5 | 756 ± 140 | 47.5 ± 3.1 | 1.23 ± 4.92 × 10−6 |

| 5 mm | HTTQ78-GFP | PFD5 | 76 | 51.7 | 851 ± 194 | 48.3 ± 5.9 | 0.28 ± 2.52 × 10−5 |

Second, when expression of PFD2 and PFD5 was knocked down by corresponding siRNAs, the diffusion times of fraction 2 in HTTQ78-GFP-expressing undifferentiated cells were significantly increased from 558 to 737 and 728 μs, respectively, but contents of fraction 2 (40.9–42.5%) were not affected, indicating that the volume of soluble aggregates was increased by 1.30–1.32- and by 2.2–2.3-fold, respectively. After Neuro-2a cells had been differentiated, knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 expression increased the diffusion times of fraction 2 of HTTQ78-GFP from 542 to 756 and 851 μs (1.39–1.58- and 2.7–3.9-fold increases in volume, respectively), and these values were larger than those obtained in undifferentiated cells. Diffusion time of fraction 2 of HTTQ23-GFP aggregation was, however, not affected by prefoldin knockdown. These results revealed that prefoldin knockdown significantly increases the size of soluble aggregates of a pathogenic form of HTT without affecting the number of soluble aggregates, especially in differentiated Neuro-2a cells.

Prefoldin Prevents HTT Aggregation at the Small Oligomer Stage in Vitro

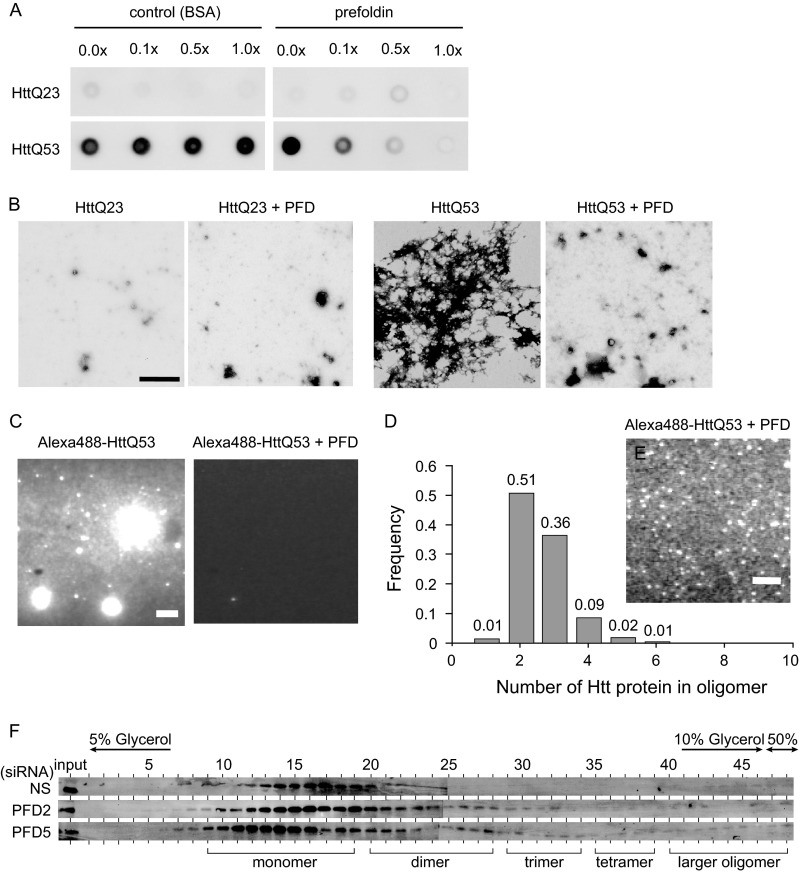

To investigate more precisely how prefoldin inhibits aggregation of pathogenic HTT, we used an in vitro aggregation assay system. First, GST-tagged prefoldin subunits were expressed in and purified from E. coli; GST was cleaved off by PreScission protease, and the prefoldin complex was reconstituted as described previously (33). GST-HTTQ53 and GST-HTTQ23 were expressed in and purified from E. coli, and addition of PreScission protease into a solution containing GST-HTTQ53 or GST-HTTQ23 triggered aggregation of HTTQ53 and HTTQ23. The effect of reconstituted prefoldin on aggregation of HTTQ53 and HTTQ23 was then examined using filter-trap assays. As shown in Fig. 6A, reconstituted prefoldin, but not BSA as a negative control, strongly inhibited aggregation of HTTQ53 in a dose-dependent manner, and complete inhibition of aggregation by prefoldin was observed with a molar ratio of prefoldin to HTTQ53 of 1:1. Furthermore, electron microscopic observation revealed the number of large aggregates of HTTQ53, but not that of HTTQ23, was reduced by prefoldin (Fig. 6B). To quantitatively analyze the aggregation status at the single molecule level, HTT proteins were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and analyzed by TIRFM in vitro (Figs. 6, C–E, and 7). The results of TIRFM observation at low and high gain levels of an image intensifier showed that aggregation of fluorescently labeled HTTQ53 was clearly inhibited by prefoldin and that there was a significantly large number of brighter particles compared with monomers (Fig. 6, C and D, respectively). After calculation of the size of HTTQ53 oligomers, HTTQ53 oligomers were found to be mostly dimers and trimers with a small amount of tetramers (Fig. 6E). These results clearly indicate that prefoldin inhibits elongation of aggregates with a larger size than that of tetramers, thereby inhibiting further fibrillization of pathogenic HTT.

FIGURE 6.

Prefoldin directly suppresses aggregation of polyQ-expanded HTT. A, filter-trap assays of HTTQ53 and HTTQ23 aggregation in the presence and absence of prefoldin. Aggregation of HTTQ53 and HTTQ23 was initiated by addition of PreScission protease to a solution containing GST-HTTQ53 and GST-HTTQ23, and the solution was incubated at 30 °C for 12 h. Aggregates were then trapped on filters and analyzed by immunoblotting with an anti-GFP antibody. Bovine serum albumin was used as a control. B, electron microscopic analysis of HTTQ53 and HTTQ23 aggregation in the presence or absence of prefoldin. Bar indicates a size of 1 μm. C, fluorescent microscopic observation of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled HTTQ53 aggregation in the presence or absence of prefoldin by the TIRFM system. Samples were diluted 10 times immediately before observation under a fluorescent microscope. The gain level of the image intensifier was set at 1.3. Bar indicates a size of 10 μm. D, distribution of the number of HTTQ53 molecules per particle. Fluorescence intensity of the single dye was determined by distribution of photobleaching unitary step intensities of labeled monomer proteins. The number of HTTQ53 molecules per particle was determined by dividing fluorescence intensities of particles by that of single dye after adjusting light attenuation levels by ND filters. E, observation of a single molecule of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled-HTTQ53 aggregation in the presence of prefoldin by the TIRFM system. Samples were diluted 3000 times immediately before observation under a fluorescent microscope. The gain level of the image intensifier was set at 4.2. Bar indicates a size of 10 μm. F, detection of pathogenic HTT oligomers under prefoldin-knockdown conditions. Differentiated Neuro-2a cell lysates containing HTTQ78-GFP were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures” and were fractionated on a 5–50% glycerol density gradient. Proteins in each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-GFP antibody.

FIGURE 7.

TIRFM analyses of HTT oligomers. A, photobleaching of Alexa Fluor 488-HTTQ53 molecule. B, distribution of photobleaching unitary step intensity of Alexa Fluor 488 dye (n = 209). The peak fluorescence intensity was estimated by Gaussian fitting and shown as mean ± S.D. C and D, fluorescence intensities of single particles of Alexa Fluor 488-GST-HTTQ53 (C) and Alexa Fluor 488-GST-HTTQ23 (D) were measured before (white column) and after (black column) incubation of proteins with PreScission protease in the presence of prefoldin for 13 h. Samples were diluted 3000-fold and illuminated by a blue laser (488 nm, 11.8 milliwatts). The gain level of the image intensifier was set at 4.2. To correctly measure the intensity of Alexa Fluor 488-GST-HTTQ53 samples that had been incubated with prefoldin for 13 h, an ND40 filter (5.2 milliwatts) was used to avoid saturation of fluorescence intensities, and their fluorescence intensities were multiplied by 2.4, which was calculated from the linear correlation between laser power and fluorescent intensity shown in E. E, fluorescent intensities of FluoSpheres (0.1 μm diameter and yellow-green, Molecular Probes) were excited with a blue laser using different ND filters. Each laser beam power was measured by a power meter. Fluorescence intensity was decreased to 41.5 ± 1.9% (1/2.4-fold) by the ND40 filter compared with that in the absence of an ND filter (ND100). a.u., arbitrary unit.

To examine whether prefoldin also inhibits formation of large oligomers of pathogenic HTT in neuronal cells, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA and PFD5 siRNA and then transfected with a pathogenic form of HTTQ78-GFP and differentiated by addition of 5 mm Bt2cAMP as described above. At 48 h after transfection of siRNAs, proteins extracted from Neuro-2a cells were separated on 5–50% glycerol density gradients. As shown in Fig. 6F, knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 increased dimer, trimer, tetramer, and larger oligomers of HTTQ78-GFP, suggesting that prefoldin inhibits large oligomer formation of pathogenic HTT.

Prefoldin Prevents Specifically HTT Aggregation

We showed that prefoldin knockdown enhances soluble oligomer formation of pathogenic HTT and decreases cell viability. Because knockdown of prefoldin and/or pathogenic HTT give harmful conditions into cells, it is also possible that harmful conditions activate apoptosis pathways independently of prefoldin or pathogenic HTT, resulting in cell death. To examine this, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA and PFD5 siRNA. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with two apoptosis inducers, staurosporine and thapsigargin, for 24 h, and cell viability was measured by an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Staurosporine and thapsigargin are inhibitors of protein kinase C and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, respectively. As shown in Fig. 8A, treatment of staurosporine and thapsigargin reduced cell viability in a dose-dependent manner, but knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 did not significantly affect staurosporine and thapsigargin-induced cell viability. These results indicate that loss of prefoldin activity targeting pathogenic HTT decreased cell viability. It is also possible that harmful conditions activate autophagy pathways independently of prefoldin or pathogenic HTT, resulting in protein aggregation. To examine this, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control for 24 h. Cells were then transfected with expression vectors for HTTQ78-GFP and HTTQ23-GFP. Twenty four h after transfection, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of the late phase of autophagy, for 12 h. SDS-insoluble aggregates were then examined by a filter-trap assay. The results showed that the levels of SDS-insoluble aggregates were increased both in control and bafilomycin A1-treated cells, suggesting that prefoldin inhibits aggregation formation of HTTQ78 independently of autophagy induction (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Prefoldin specifically affects cell viability by targeting polyQ-expanded HTT. A, Neuro-2a cells in 96-well plates were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA (N.S.) as a control. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with various amounts of staurosporine (A, panel a) and thapsigargin (A, panel b) for 24 h, and cell viability was examined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assays. A negative control, shown as “nega,” indicates cells that were added with a transfection buffer and DMSO and then killed with 20% Triton X-100 before measuring their viability. A positive control, shown as “posi,” indicates cells that were added with a transfection buffer and DMSO. B, Neuro-2a cells were transfected with PFD2 siRNA, PFD5 siRNA, or nonspecific siRNA as a control for 24 h. Cells were then transfected with expression vectors for HTTQ78-GFP and HTTQ23-GFP. Twenty-four h after transfection, cells were treated with bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of the late phase of autophagy, for 12 h. SDS-insoluble aggregates were then examined by a filter trap assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

DISCUSSION

Because accumulating evidence suggests that formation of pathogenic HTT inclusions is not correlated with neuronal cell death (8, 9), it is thought that soluble oligomers, rather than inclusions, have an important role in neuronal cell toxicity. Oligomerized number and characteristics of pathogenic proteins, however, have not been investigated in detail. This study first showed that knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 disrupted prefoldin formation in healthy and pathogenic forms of polyQ or HTT-expressing cells, resulting in accumulation of aggregates of a pathogenic form of polyQ or HTT and in induction of cell death (Figs. 1 and 2). Overexpression of the prefoldin complex reduced accumulation of aggregates of the pathogenic form of HTT (Fig. 3). Knockdown of PFD2 and PFD5 also increased the size of soluble oligomers of the pathogenic form of HTT in cells (Fig. 5). These phenomena observed in polyQ or HTT-expressing cells were also observed in an in vitro system composed of reconstituted prefoldin against purified HTT (Fig. 6, A and B). Furthermore, in vitro single molecule observation by TIRFM analysis demonstrated that prefoldin suppressed HTT aggregation at the small oligomer (dimer to tetramer) stage (Fig. 6E). When PFD2 and PFD5 were knocked down, amounts of dimer, trimer, and larger oligomers of pathogenic HTT were increased (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, prefoldin suppresses neuronal cell death, and dead cells did not contain HTT inclusions (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that prefoldin inhibits elongation of large oligomers of the pathogenic HTT, thereby inhibiting subsequent aggregate and inclusion formation, and suggest that soluble large oligomers of polyQ-expanded HTT are more toxic than are inclusions to cells.

Immunofluorescence experiments in this study showed that prefoldin was localized in the cytosol without co-localization with inclusions in HTT-expressing cells, in contrast to the fact that HSP70 was co-localized with inclusions (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that once an inclusion is formed, prefoldin is not able to disrupt inclusion formation and that the inclusion itself is not toxic to cells. Because the localization of prefoldin is reminiscent of that of CCT (21), it is possible that prefoldin cooperates with CCT to prevent the toxicity of HTT at the soluble stage of aggregation or oligomer formation. Because prefoldin interacts with substrate proteins via the tips of tentacles using its hydrophobic surfaces (25, 26, 41), prefoldin may trap misfolded proteins more easily than CCT, which has the substrate recognition site in the cavity near the entrance (42–44).

How does prefoldin inhibit polyglutamine toxicity? Simply thinking from the experimental results in this study, prefoldin delays formation of dimers and trimers of pathogenic HTT oligomers by inhibiting further their elongation, suggesting that pathogenic HTT oligomers of more than tetramers are toxic and that dimers and trimers of pathogenic HTT oligomers are not toxic to cells. However, considering that prefoldin is a chaperone, the following is also possible. Prefoldin may trap misfolded small species (monomers or dimers) and change them into nontoxic small oligomers such as dimers, trimers, and tetramers (Fig. 9). Toxic soluble oligomers are thought to exert their toxicity by interacting with other proteins (e.g. co-aggregation with functional cellular proteins such as transcription factors TBP and CBP) (38). Co-existence of nontoxic and toxic oligomers of amyloidogenic proteins in cells has indeed been reported (45). If toxic species trapped by prefoldin (e.g. hydrophobic β-sheets) cannot easily be changed into nontoxic forms, prefoldin probably transfers them to CCT or other appropriate chaperones. Prefoldin might also deliver misfolded toxic species to the proteasome for degradation through direct interaction (38, 46).

FIGURE 9.

Schematic model of action of prefoldin against pathogenic forms of Huntingtin.

Knockdown of prefoldin expression increased aggregation of both GFP-Q72 and HTTQ78-GFP, the latter of which possesses regions of polyQ and of proteins other than polyQ, indicating that prefoldin recognizes the polyQ sequence rather than a sequence unique to HTT protein. Expression of PFD subunits, particularly PFD2, PFD3, and PFD5, was significantly stimulated after differentiation of Neuro-2a cells (Fig. 2). Although knockdown of PFD5 and PFD2 significantly stimulated aggregation and toxicity of pathogenic HTT in differentiated Neuro-2a cells, knockdown of PFD2, but not that of PFD5, enhanced aggregation and toxicity in undifferentiated Neuro-2a cells. These observations suggest that activity of PFD, including aggregation prevention activity, appears more strongly in neuronal cells than in non-neuronal cells. Intriguingly, PFD1 knock-out mice show neuronal loss in the cerebellum and defects in lymphocyte development (47). PFD5-L110R mutant mice also showed that PFD5 missense mutation causes neurodegeneration, photoreceptor degeneration, and male infertility (48). These observations suggest that prefoldin plays a pivotal role in maintenance of neuronal cell activity. It has been reported that each of the PFD subunits has its own function, including transcriptional regulation for PFD5 (49, 50) and PFD4 (51) and DNA binding activity for PFD1 and PFD2 (52), and that there are some distinctive phenotypes between PFD1-null and PFD5-L110R mice (47, 48). PFD5/MM-1 is known to act as a c-MYC-binding protein that suppresses cell growth and transformation independently of the prefoldin complex (49, 53). Furthermore, Tang et al. (54) have reported that the expression level of PFD5 mRNA was up-regulated in HTTQ300-expressing mice (R6/2) despite the fact that mRNA levels of other subunits were unaffected. Thus, it is possible that PFD5 alone, or other subunits also, protects neuronal cells through its specific activity. In addition, Simons et al. (33) showed that the prefoldin complex interacts with actin and tubulin in a subunit-specific manner, and each subunit differentially binds to a target protein. CCT also suppresses toxic HTT oligomer formation through specific recognition by its α subunit (55). These observations suggest that particular subunits require their own function to explore their maximal activity in addition to activity as the complex such as prefoldin and CCT.

Knockdown of prefoldin stimulated formation of HTT aggregation and reduced viability of pathogenic HTT-expressing Neuro-2a cells. Because treatment of cells with two apoptosis inducers did not change viability of prefoldin knockdown cells (Fig. 7), it is thought that reduced prefoldin activity is directly associated with pathogenic HTT-induced cell toxicity. It has recently been reported that prothymosin-α interacted with pathogenic HTT and suppressed its toxicity through inhibiting pathogenic HTT-induced apoptosis pathway (56). Prothymosin-α was co-localized with HTT in the nucleus and facilitated aggregate formation of pathogenic HTT (56). Although both prefoldin and prothymosin-α show protective activity against the toxicity of pathogenic HTT, their mechanisms may be different.

In conclusion, this study clearly indicates that prefoldin prevents toxicity of polyQ-expanded HTT by inhibiting formation of toxic oligomers. Up-regulation of prefoldin by introduction of its subunit genes and by drugs may be useful as a therapy for Huntington disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Profs. R. I. Morimoto and F. U. Hartl for providing expression vectors for HTT and for GST-HTT, respectively.

This work was supported by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization, RIKEN, and the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, Japan.

- CCT

- chaperonin-containing TCP-1

- TIRFM

- total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy

- PFD

- prefoldin

- Bt2cAMP

- dibutyryl cyclic AMP

- FCS

- fluorescence correlation spectroscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1. Walker F. O. (2007) Huntington's disease. Lancet 369, 218–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Langbehn D. R., Brinkman R. R., Falush D., Paulsen J. S., Hayden M. R. (2004) A new model for prediction of the age of onset and penetrance for Huntington's disease based on CAG length. Clin. Genet. 65, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zoghbi H. Y., Orr H. T. (2000) Glutamine repeats and neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 217–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davies S. W., Turmaine M., Cozens B. A., DiFiglia M., Sharp A. H., Ross C. A., Scherzinger E., Wanker E. E., Mangiarini L., Bates G. P. (1997) Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell 90, 537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DiFiglia M., Sapp E., Chase K. O., Davies S. W., Bates G. P., Vonsattel J. P., Aronin N. (1997) Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science 277, 1990–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perutz M. F., Johnson T., Suzuki M., Finch J. T. (1994) Glutamine repeats as polar zippers: their possible role in inherited neurodegenerative diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5355–5358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perutz M. F., Finch J. T., Berriman J., Lesk A. (2002) Amyloid fibers are water-filled nanotubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5591–5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arrasate M., Mitra S., Schweitzer E. S., Segal M. R., Finkbeiner S. (2004) Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature 431, 805–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saudou F., Finkbeiner S., Devys D., Greenberg M. E. (1998) Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions. Cell 95, 55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krobitsch S., Lindquist S. (2000) Aggregation of huntingtin in yeast varies with the length of the polyglutamine expansion and the expression of chaperone proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 1589–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Satyal S. H., Schmidt E., Kitagawa K., Sondheimer N., Lindquist S., Kramer J. M., Morimoto R. I. (2000) Polyglutamine aggregates alter protein folding homeostasis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 5750–5755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wyttenbach A., Sauvageot O., Carmichael J., Diaz-Latoud C., Arrigo A. P., Rubinsztein D. C. (2002) Heat shock protein 27 prevents cellular polyglutamine toxicity and suppresses the increase of reactive oxygen species caused by huntingtin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1137–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morimoto R. I. (2008) Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes Dev. 22, 1427–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Broadley S. A., Hartl F. U. (2009) The role of molecular chaperones in human misfolding diseases. FEBS Lett. 583, 2647–2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Muchowski P. J., Schaffar G., Sittler A., Wanker E. E., Hayer-Hartl M. K., Hartl F. U. (2000) hsp70 and hsp40 chaperones can inhibit self-assembly of polyglutamine proteins into amyloid-like fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 7841–7846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wacker J. L., Zareie M. H., Fong H., Sarikaya M., Muchowski P. J. (2004) Hsp70 and Hsp40 attenuate formation of spherical and annular polyglutamine oligomers by partitioning monomer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 1215–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cummings C. J., Sun Y., Opal P., Antalffy B., Mestril R., Orr H. T., Dillmann W. H., Zoghbi H. Y. (2001) Overexpression of inducible HSP70 chaperone suppresses neuropathology and improves motor function in SCA1 mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1511–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kazemi-Esfarjani P., Benzer S. (2000) Genetic suppression of polyglutamine toxicity in Drosophila. Science 287, 1837–1840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Warrick J. M., Chan H. Y., Gray-Board G. L., Chai Y., Paulson H. L., Bonini N. M. (1999) Suppression of polyglutamine-mediated neurodegeneration in Drosophila by the molecular chaperone HSP70. Nat. Genet. 23, 425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Behrends C., Langer C. A., Boteva R., Böttcher U. M., Stemp M. J., Schaffar G., Rao B. V., Giese A., Kretzschmar H., Siegers K., Hartl F. U. (2006) Chaperonin TRiC promotes the assembly of polyQ expansion proteins into nontoxic oligomers. Mol. Cell 23, 887–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitamura A., Kubota H., Pack C. G., Matsumoto G., Hirayama S., Takahashi Y., Kimura H., Kinjo M., Morimoto R. I., Nagata K. (2006) Cytosolic chaperonin prevents polyglutamine toxicity with altering the aggregation state. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1163–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tam S., Geller R., Spiess C., Frydman J. (2006) The chaperonin TRiC controls polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity through subunit-specific interactions. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1155–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siegers K., Waldmann T., Leroux M. R., Grein K., Shevchenko A., Schiebel E., Hartl F. U. (1999) Compartmentation of protein folding in vivo: sequestration of non-native polypeptide by the chaperonin-GimC system. EMBO J. 18, 75–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vainberg I. E., Lewis S. A., Rommelaere H., Ampe C., Vandekerckhove J., Klein H. L., Cowan N. J. (1998) Prefoldin, a chaperone that delivers unfolded proteins to cytosolic chaperonin. Cell 93, 863–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siegert R., Leroux M. R., Scheufler C., Hartl F. U., Moarefi I. (2000) Structure of the molecular chaperone prefoldin: unique interaction of multiple coiled coil tentacles with unfolded proteins. Cell 103, 621–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martín-Benito J., Gómez-Reino J., Stirling P. C., Lundin V. F., Gómez-Puertas P., Boskovic J., Chacón P., Fernández J. J., Berenguer J., Leroux M. R., Valpuesta J. M. (2007) Divergent substrate-binding mechanisms reveal an evolutionary specialization of eukaryotic prefoldin compared to its archaeal counterpart. Structure 15, 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Geissler S., Siegers K., Schiebel E. (1998) A novel protein complex promoting formation of functional α- and γ-tubulin. EMBO J. 17, 952–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. (2002) Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295, 1852–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sakono M., Zako T., Ueda H., Yohda M., Maeda M. (2008) Formation of highly toxic soluble amyloid β oligomers by the molecular chaperone prefoldin. FEBS J. 275, 5982–5993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kouroku Y., Fujita E., Tanida I., Ueno T., Isoai A., Kumagai H., Ogawa S., Kaufman R. J., Kominami E., Momoi T. (2007) ER stress (PERK/eIF2α phosphorylation) mediates the polyglutamine-induced LC3 conversion, an essential step for autophagy formation. Cell Death Differ. 14, 230–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schaffar G., Breuer P., Boteva R., Behrends C., Tzvetkov N., Strippel N., Sakahira H., Siegers K., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F. U. (2004) Cellular toxicity of polyglutamine expansion proteins: mechanism of transcription factor deactivation. Mol. Cell 15, 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wanker E. E., Scherzinger E., Heiser V., Sittler A., Eickhoff H., Lehrach H. (1999) Membrane filter assay for detection of amyloid-like polyglutamine-containing protein aggregates. Methods Enzymol. 309, 375–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simons C. T., Staes A., Rommelaere H., Ampe C., Lewis S. A., Cowan N. J. (2004) Selective contribution of eukaryotic prefoldin subunits to actin and tubulin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4196–4203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taguchi H., Ueno T., Tadakuma H., Yoshida M., Funatsu T. (2001) Single-molecule observation of protein-protein interactions in the chaperonin system. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 861–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zako T., Iizuka R., Okochi M., Nomura T., Ueno T., Tadakuma H., Yohda M., Funatsu T. (2005) Facilitated release of substrate protein from prefoldin by chaperonin. FEBS Lett. 579, 3718–3724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gell C., Brockwell D., Smith A. (eds) (2006) Handbook of Single Molecule Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Oxford University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leake M. C., Chandler J. H., Wadhams G. H., Bai F., Berry R. M., Armitage J. P. (2006) Stoichiometry and turnover in single, functioning membrane protein complexes. Nature 443, 355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Miyazawa M., Tashiro E., Kitaura H., Maita H., Suto H., Iguchi-Ariga S. M., Ariga H. (2011) Prefoldin subunits are protected from ubiquitin-proteasome system-mediated degradation by forming complex with other constituent subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 19191–19203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eigen M., Rigler R. (1994) Sorting single molecules: application to diagnostics and evolutionary biotechnology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5740–5747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Elson E. L. (2001) Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy measures molecular transport in cells. Traffic 2, 789–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martín-Benito J., Boskovic J., Gómez-Puertas P., Carrascosa J. L., Simons C. T., Lewis S. A., Bartolini F., Cowan N. J., Valpuesta J. M. (2002) Structure of eukaryotic prefoldin and of its complexes with unfolded actin and the cytosolic chaperonin CCT. EMBO J. 21, 6377–6386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ditzel L., Löwe J., Stock D., Stetter K. O., Huber H., Huber R., Steinbacher S. (1998) Crystal structure of the thermosome, the archaeal chaperonin and homolog of CCT. Cell 93, 125–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klumpp M., Baumeister W., Essen L. O. (1997) Structure of the substrate binding domain of the thermosome, an archaeal group II chaperonin. Cell 91, 263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Llorca O., Smyth M. G., Carrascosa J. L., Willison K. R., Radermacher M., Steinbacher S., Valpuesta J. M. (1999) 3D reconstruction of the ATP-bound form of CCT reveals the asymmetric folding conformation of a type II chaperonin. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 639–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uversky V. N. (2010) Mysterious oligomerization of the amyloidogenic proteins. FEBS J. 277, 2940–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mousnier A., Kubat N., Massias-Simon A., Ségéral E., Rain J. C., Benarous R., Emiliani S., Dargemont C. (2007) von Hippel Lindau binding protein 1-mediated degradation of integrase affects HIV-1 gene expression at a postintegration step. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13615–13620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cao S., Carlesso G., Osipovich A. B., Llanes J., Lin Q., Hoek K. L., Khan W. N., Ruley H. E. (2008) Subunit 1 of the prefoldin chaperone complex is required for lymphocyte development and function. J. Immunol. 181, 476–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee Y., Smith R. S., Jordan W., King B. L., Won J., Valpuesta J. M., Naggert J. K., Nishina P. M. (2011) Prefoldin 5 is required for normal sensory and neuronal development in a murine model. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 726–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mori K., Maeda Y., Kitaura H., Taira T., Iguchi-Ariga S. M., Ariga H. (1998) MM-1, a novel c-Myc-associating protein that represses transcriptional activity of c-Myc. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29794–29800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Satou A., Taira T., Iguchi-Ariga S. M., Ariga H. (2001) A novel transrepression pathway of c-Myc. Recruitment of a transcriptional corepressor complex to c-Myc by MM-1, a c-Myc-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 46562–46567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Iijima M., Kano Y., Nohno T., Namba M. (1996) Cloning of cDNA with possible transcription factor activity at the G1-S phase transition in human fibroblast cell lines. Acta Med. Okayama 50, 73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Myung J. K., Afjehi-Sadat L., Felizardo-Cabatic M., Slavc I., Lubec G. (2004) Expressional patterns of chaperones in 10 human tumor cell lines. Proteome Sci. 2, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fujioka Y., Taira T., Maeda Y., Tanaka S., Nishihara H., Iguchi-Ariga S. M., Nagashima K., Ariga H. (2001) MM-1, a c-Myc-binding protein, is a candidate for a tumor suppressor in leukemia/lymphoma and tongue cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45137–45144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tang B., Seredenina T., Coppola G., Kuhn A., Geschwind D. H., Luthi-Carter R., Thomas E. A. (2011) Gene expression profiling of R6/2 transgenic mice with different CAG repeat lengths reveals genes associated with disease onset and progression in Huntington's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 42, 459–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tam S., Spiess C., Auyeung W., Joachimiak L., Chen B., Poirier M. A., Frydman J. (2009) The chaperonin TRiC blocks a huntingtin sequence element that promotes the conformational switch to aggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 1279–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dong G., Callegari E. A., Gloeckner C. J., Ueffing M., Wang H. (2012) Prothymosin-α interacts with mutant huntingtin and suppresses its cytotoxicity in cell culture. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1279–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]