Background: The interaction of PAK1 and the RAF-MEK-ERK cascade is unclear.

Results: Overexpression of a kinase-dead mutant form of PAK1 increased phosphorylation of MEK1/2 and ERK. Hyperactivated Rac1 induced the formation of a triple complex of Rac1, PAK1, and MEK1 independent of the kinase activity of PAK1.

Conclusion: PAK1 activated MEK-ERK cascade in a kinase-independent manner.

Significance: PAK1 might be a scaffold to facilitate interaction of C-RAF and MEK1.

Keywords: ERK, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), Rac1, RAF, Scaffold Proteins, MEK, PAK

Abstract

PAK1 plays an important role in proliferation and tumorigenesis, at least partially by promoting ERK phosphorylation of C-RAF (Ser-338) or MEK1 (Ser-298). We observed how that overexpression of a kinase-dead mutant form of PAK1 increased phosphorylation of MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and ERK (Thr-202/Tyr-204), although phosphorylation of B-RAF (Ser-445) and C-RAF (Ser-338) remained unchanged. Furthermore, increased activation of the PAK1 activator Rac1 induced the formation of a triple complex of Rac1, PAK1, and MEK1 independent of the kinase activity of PAK1. These data suggest that PAK1 can stimulate MEK activity in a kinase-independent manner, probably by serving as a scaffold to facilitate interaction of C-RAF.

Introduction

PAK1 is a member of the p21-activated kinase (PAK)3 family of serine/threonine kinases, which regulate cell morphology, motility, survival, and proliferation (1, 2). Important activators of PAK1 are the small GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42. In their active, membrane-bound form, they are able to recruit PAK1 to the cell membrane and induce a conformational shift, leading to the activation of the kinase function of PAK1 and autophosphorylation. Via the kinase function PAK1 has been described as phosphorylating different molecules, which then mediate the biological effects of PAK1. In addition, PAK1 is shown to activate AKT activation in a kinase-independent manner by aiding the recruitment of AKT to the membrane (3).

One of the pathways regulated by PAK is the RAF-MEK-ERK cascade, which is important for proliferation. RAF phosphorylates MEK1/2 at Ser-217/Ser-221, respectively, which is necessary and sufficient to activate MEK. Activated MEK then activates ERK by phosphorylation at Thr-202 and Tyr-204 (4).

Previous studies have demonstrated that MEK1 and C-RAF (also known as RAF-1) are two direct PAK substrates (5). PAK phosphorylation of C-RAF (Ser-338) should directly correspond to C-RAF activation, whereas phosphorylation of MEK1 at serine 298 facilitates the signal transduction from RAF to MEK, thus indirectly promoting MEK1 activation. Slack-Davis et al. (6) report that MEK1 is phosphorylated by PAK1/2 at position Ser-298, and it is thought that this phosphorylation is essential for transmitting mitogenic signals. More recently, we found that in primary mouse keratinocytes PAK1 regulates ERK activation by controlling the phosphorylation of MEK1/2 at Ser-217/Ser-221 without changing the phosphorylation of C-RAF at serine 338 or of B-RAF at serine 445. PAK2 regulates MEK1 at Ser-298, but this is neither required nor sufficient for ERK activation in vitro (7). However, we did not elucidate how PAK1 in this system might contribute to increased MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) phosphorylation.

Using cancer cell lines as a model, we report now that PAK1 can promote ERK activation in a kinase-independent manner, probably by recruiting MEK to the membrane, which facilitates the interaction with RAF. By this scaffold function, PAK1 contributes to cell proliferation and tumor formation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Human platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) was purchased from Sigma (SI P8147). The following primary antibodies were used: PAK1, C-RAF, MEK1, p-B-RAF (Ser-445), p-C-RAF (Ser-338), p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221), p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) (all from Cell Signaling Technology), and tubulin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection

HeLa, SW480, HT-29, IEC-6, and NIH3T3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal calf serum. The cells were plated at 3 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates in DMEM plus 10% calf serum. PAK1 WT cDNA or PAK1 K299R (PAK1 mutant) cDNA was cloned into Myc-tagged pcDNA3.0 vector. Cells were then transiently transfected with Myc-tagged PAKWT, Myc-tagged PAKmutant, or high cycling Rac1 vector using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). shRNA target PAK1 (3′-noncoding area) was purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co. (lot No. A05925). shRNA target constitutive PAK1 was purchased from Shanghai GenePharma Co. (lot No. A05927).

Subcellular Fractionation

Cell membrane protein was collected by using a plasma membrane protein extraction kit (Abcam, ab65400). In brief, cells were washed with cold PBS and suspended in homogenized buffer mix in an ice-cold Dounce homogenizer. Homogenates were centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants (cytosol) were collected, and the pellets were resuspended in upper and lower phase solution. The lysates were again centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min, and the pellets (membrane) were collected. The distributions of proteins in the cytosol and membrane fractions were analyzed by Western blot.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot were carried out as described previously (9). In brief, 48 h after transfection, cells were washed in cold PBS and lysed with 0.5 ml of immunoprecipitation lysis buffer for 0.5 h at 4 °C. The whole cell lysates were incubated with control rabbit normal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PAK1 antibody, HA, or the Myc antibody (all from Cell signaling) at 4 °C for 1 h. Pre-equilibrated protein G-agarose beads (Roche Applied Science) were then added, collected by centrifugation after 1 h of incubation, and then gently washed with the lysis buffer. The precipitates were washed with ice-cold lysis buffer. To elute the bound proteins, washed precipitates were boiled in SDS sample buffer. Protein samples were detected by the indicated antibodies using Western blot according to standard protocols. Western blot results were quantified using TotalLab TL100 software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), and tubulin was used to normalize for different protein amounts.

Immunofluorescent Staining

HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 48 h. For PDGF stimulation, cells were serum-starved for 4 h and then left unstimulated or stimulated with PDGF (20 ng·ml−1) for 15 min. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature after incubation with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 min to block nonspecific antibody binding. Endogenous MEK1 was detected using an anti-MEK1 mouse monoclonal antibody. After washing with PBS, the cells were stained with Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. Pictures were taken by confocal microscope.

Proliferation Assay

Cells were treated with the indicated reagents and plasmids. Proliferation was tested by crystal violet staining as described previously (7), Cell numbers were then determined by crystal violet staining. In brief, cells were seeded in 96-well plates for 2 days. Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 20% methanol for 15 min at room temperature. After cells were washed with PBS, cell-bound crystal violet was extracted with 10% SDS. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

Statistics

Averages are shown with standard deviation. Significance was calculated by Student's t test.

RESULTS

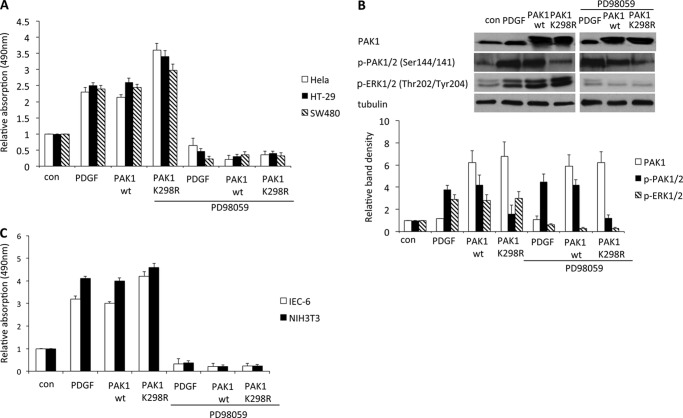

PAK1 Regulates Cells Proliferation Independent of Kinase Activity

PAK1 has been reported to be hyperactivated in various cancer tissues to promote cancer cell proliferation (8). However, unexpectedly, after we transfected two colon cancer cell lines, SW480 and HT-29 as well as HeLa cells with wild type PAK1 (PAK1WT) or kinase-negative PAK1 (K298R; PAK1K298R) plasmids, we observed an increase of p-PAK1/2 (Ser-144/Ser-141) and p-ERK1/2(Thr-202/Tyr-204) by Western blot. Using a crystal violet assay, expression of PAK1WT and PAK1K298R effectively promoted cell proliferation. Inhibition of MEK phosphorylation by PD98059 at 50 μm significantly decreased the level of p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) but not p-PAK1/2 (Ser-144/Ser-141), consistent with previous observations in keratinocytes (7), and reduced the proliferation induced by PDGF, PAK1WT, or PAK1K298R (Fig. 1, A and B). Similar results were obtained with the normal intestinal epithelial cell line IEC-6 and with NIH3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. 1C), suggesting that PAK1 promotes cell proliferation through MEK1 in a kinase-independent manner.

FIGURE 1.

PAK1 regulates cell proliferation through MEK1 activity independent of its kinase activity. A, SW480, HT-29, and HeLa cells were treated with PDGF (20 ng/ml) and/or the MEK inhibitor PD985402 (50 μm) or were transfected with the indicated plasmids and analyzed for growth by crystal violet staining 2 days later (n = 6; *, p < 0.01). B, HeLa cells were transfected with PAK1WT or PAK1 PAK1K299R plasmid for 18 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to p-B-RAF (Ser-445), p-C-RAF (Ser-338), p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221), and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204). Expression of PAK1 mutants was confirmed by immunoblotting with antibodies to PAK1, Myc, and p-PAK1/2 (Ser-144/Ser-141). Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown. C, IEC-6 and NIH3T3 cells were treated with PDGF (20 ng/ml) and/or the MEK inhibitor PD985402 (50 μm) or were transfected with the indicated plasmids and analyzed for growth by crystal violet staining 2 days later (n = 6; *, p < 0.01). con, control.

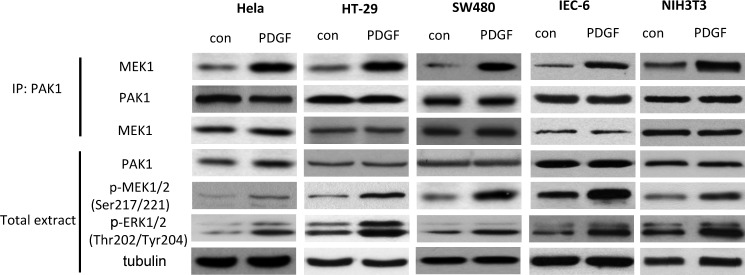

PDGF Increases Binding of PAK1 and MEK1

PDGF has been reported to stimulate cell proliferation partially by Rac1-dependent activation of the MEK-ERK pathway (9). To examine the interaction of PAK1 and MEK1 under this condition, HeLa, SW480, HT-29, IEC-6, and NIH3T3 cells were incubated with PDGF. Increased binding of MEK1 and PAK1 was observed in response to PDGF (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

PDGF mediated binding of PAK1 and MEK. Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of MEK1 and PAK1 in HeLa, SW480, HT-29, NIH3T3, and IEC-6 cell lysates. Cells were serum-starved for 4 h and then left unstimulated or stimulated with PDGF (20 ng·ml−1) for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to Myc and then immunoblotted with antibodies to Myc or MEK1. Western blotting was carried out with the indicated antibodies. con, control.

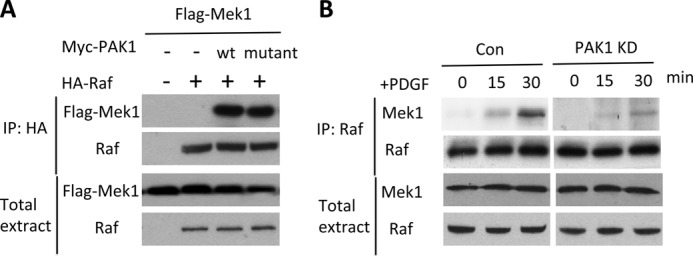

We next tested whether PAK1 promotes the association of RAF and MEK1. Indeed, expression of PAK1WT or PAK1K298R greatly increased the amount of FLAG-tagged MEK1, which co-immunoprecipitated with HA-tagged RAF (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, knockdown of endogenous PAK1 by shRNA reduced the amount of endogenous MEK1 that co-immunoprecipitated with RAF, regardless of incubation of PDGF, in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 3B). Our results indicate that PAK1 may regulate cell proliferation by promoting the interaction of RAF and MEK1, inducing MEK1 phosphorylation. However, this activation did not require PAK1 kinase activity.

FIGURE 3.

PAK1 bridged the interaction of RAF and MEK. A, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 18 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with antibodies against HA and immunoblotted with antibodies against FLAG or C-RAF. B, NIH3T3 cells were transfected with the shRNA against PAK1 for 48 h. Then cells were serum-starved for 4 h and then left unstimulated or stimulated with PDGF (20 ng·ml−1) for 0, 15, 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against RAF and immunoblotted with antibodies against MEK1 or C-RAF. Con, control.

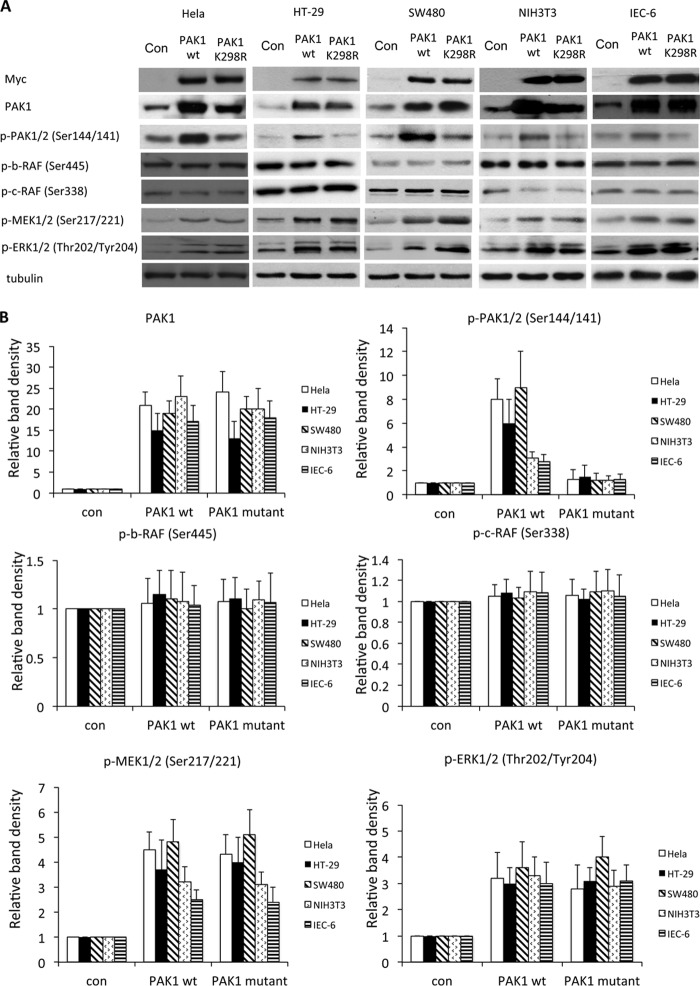

PAK1 Enhances Phosphorylation of MEK1 in a Kinase-independent Manner

To test the importance of the kinase function of PAK1 for MEK phosphorylation in cancer cells, we transfected SW480 HT-29, and HeLa cells, as well as IEC-6 and NIH3T3 cells, with PAK1WT or PAK1K298R plasmids. Overexpression of Myc-tagged PAK1WT resulted in increased levels of p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204), indicating increased activation of both MEK1/2 and ERK. Neither B-RAF nor C-RAF phosphorylation was altered in cells transfected with PAK1WT. Similar changes were observed in cells transfected with PAK1K298R, indicating that PAK1can activate MEK1/2 in a kinase-independent manner. Loss of kinase activity of PAK1K298R was confirmed by blotting for pPAK1/2 (Ser-144/Ser-141), which was increased after transfection with PAK1WT but unchanged after transfection with PAK1K298R, whereas ectopic expression of both PAK1 forms was comparable (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

PAK1 regulated MEK1 activity independent of its kinase activity. A, HeLa, SW480, HT-29, NIH3T3, and IEC-6 cells were transfected with PAK1WT or PAK1K299R plasmid for 18 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to p-B-RAF (Ser-445), p-C-RAF (Ser-338), p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221), and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204). Expression of PAK1 mutants was confirmed by immunoblotting with antibodies to PAK1, Myc, and p-PAK1/2 (Ser-144/Ser-141). Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown. B, quantification of Western blot analyses (n = 3; *, p < 0.01). Con, control.

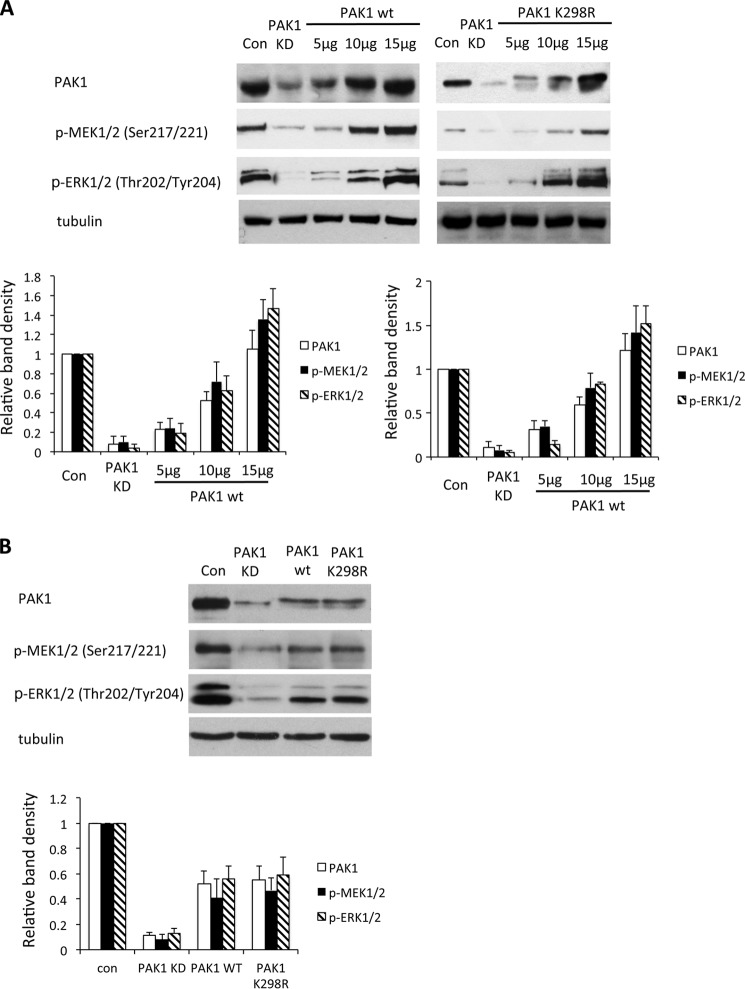

To show the importance of endogenous PAK1 for the activation of ERK in HeLa cells, we next depleted endogenous PAK1 by shRNA against the PAK1 3′-noncoding area (Fig. 5A). Indeed, knockdown of PAK1 resulted in decreased levels of p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204). We then tried to rescue the phenotype by transfection of PAK1WT and PAK1K298R into PAK1 knockdown cells. Because the PAK1 expression vectors did not contain the sequence targeted by the shRNA, they were insensitive to the PAK1 knockdown. We observed increased p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) by both PAK1WT and PAK1K298R in a dose-dependent manner. Similarly, transfection with PAK1WT and PAK1K298R could rescue the decrease of p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) because of the knockdown of endogenous PAK1 in NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 5B). These data corroborate PAK1 activation of MEK-ERK signaling in a kinase-independent manner.

FIGURE 5.

PAK1 regulated MEK1 phosphorylation independent of its kinase activity. A, HeLa cells were transfected with shRNA against endogenous PAK1 (PAK1 KD) and PAK1WT or PAK1 PAK1K299R plasmid at different concentrations for 18 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204). Each blot was quantified and analyzed (n = 3; *, p < 0.01). B, NIH3T3 cells were transfected with shRNA against endogenous PAK1 (PAK1 KD) and PAK1WT or PAK1K299R plasmid at a concentration of 15 μg for 18 h. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to p-MEK1/2 (Ser-217/Ser-221) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204). Each blot was quantified and analyzed (n = 3; *, p < 0.01). Con, control.

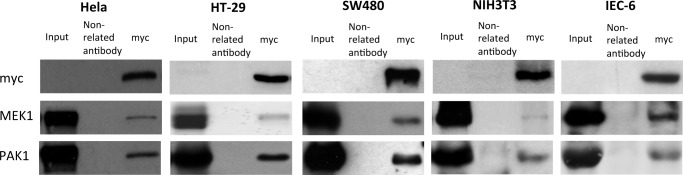

PAK1 Recruits MEK1 onto the Membrane

It was reported earlier that PAK1 activates AKT in a kinase-independent manner by recruiting AKT to the cell membrane (3). To investigate whether a similar mechanism could be involved in the kinase-independent MEK1/2 activation of PAK, we checked whether PAK1 could bind to MEK while at the cell membrane. PAK1 can be associated indirectly with the cell membrane by binding to GTP-bound, active Rac1 or Cdc42. If this interaction is stable, it might increase the amount of membrane-associated MEK that can bind to the activated PAK, resulting in a triple complex of Rac-GTP, PAK1, and MEK.

To probe for the existence of such triple complexes, we transfected the three cancer cell lines with a Myc-tagged, high cycling form of Rac1, which is preferentially in the GTP-bound state. Immunoprecipitation of Rac1 by antibodies against Myc pulled down PAK1 but also MEK1, suggesting the formation of a triple complex of activated Rac1, PAK1, and MEK1 at the cell membrane (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Association of MEK1 and PAK1. Immunoprecipitation of MEK1 and PAK1 in SW480, HT-29, HeLa, NIH3T3, and IEC-6 cell lysates. Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 36 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to Myc and then immunoblotted with antibodies to Myc, PAK1, or MEK1.

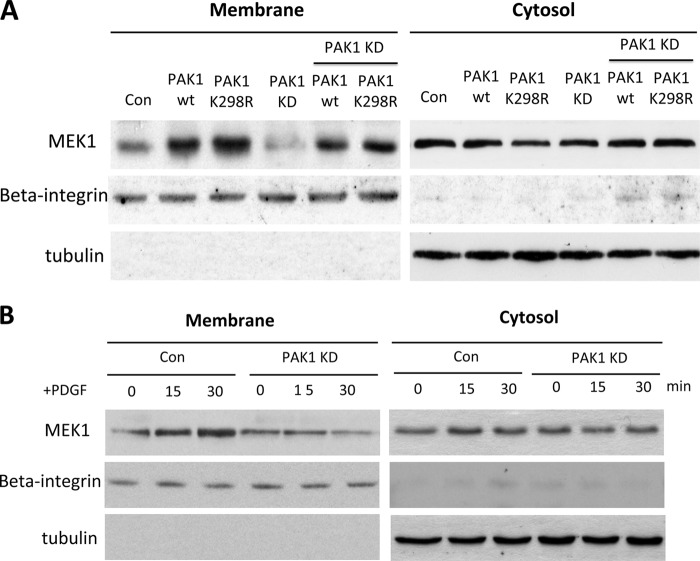

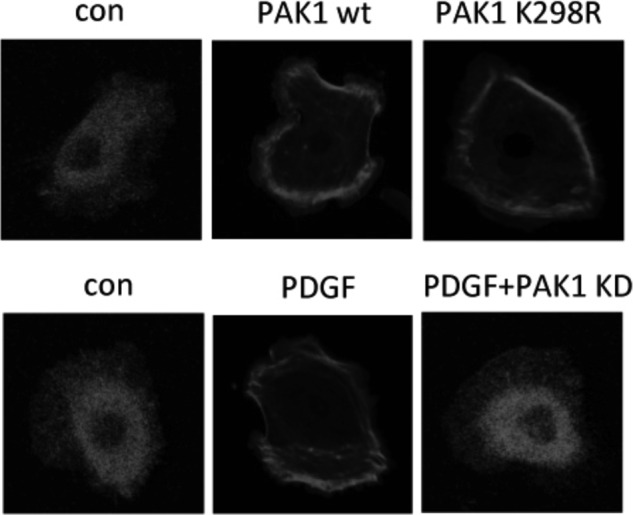

If MEK is recruited to the cell membrane via PAK1 bound to membrane-associated Rac1, we would expect an increase of MEK1 in the membrane fraction by overexpression of PAK1. This is exactly what we observed in HeLa cells overexpressing PAK1WT but also in those overexpressing the kinase-dead mutant form, PAK1K298R (Fig. 7A). Growth factor stimulation induced translocation of endogenous MEK1 (Fig. 7B) from the cytosolic to plasma membrane fractions, a process that was inhibited by repression of endogenous PAK1. A decrease in PAK1 expression by shRNA knockdown reduced translocation of MEK1 to the cell membrane (Fig. 7B). Moreover, immunofluorescent staining revealed that expression of PAK1WT and PAK1K298R effectively promoted the translocation of MEK1 to the membrane fraction (Fig. 8). Similarly, stimulation of growth factor PDGF induced translocation of endogenous MEK1 (Fig. 8) from the cytosolic to the plasma membrane, a process inhibited by PAK1 shRNA, suggesting that endogenous PAK1 is crucial for membrane translocation of MEK1 stimulated by growth factors.

FIGURE 7.

PAK1 recruits MEK1 onto the membrane and promotes its phosphorylation in a kinase-independent manner. A, HeLa cells were transfected with shRNA against PAK1 (PAK1 KD) and PAK1WT or PAK1 PAK1K299R plasmid for 48 h. Cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation, and the amounts of MEK1 in the membrane or cytosolic were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to MEK1. B, NIH3T3 cells were transfected with shRNA against endogenous PAK1 for 48 h. Then cells were serum-starved for 4 h and then left unstimulated or stimulated with PDGF (20 ng ml−1) for 0, 15, and 30 min. Cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation, and the amounts of MEK1 in the membrane or cytosolic were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to MEK1. Con, control.

FIGURE 8.

PAK1 recruits MEK1 onto the membrane and promotes its phosphorylation in a kinase-independent manner. HeLa cells were transfected with shRNA against endogenous PAK1 (PAK1 KD) and PAK1WT or PAK1 PAK1K299R plasmid for 48 h. Cells were serum-starved for 4 h and then left unstimulated or stimulated with PDGF (20 ng ml−1) for 15 min. Cells were fixed and stained with antibodies to MEK1. Scale bar, 20 μm. con, control.

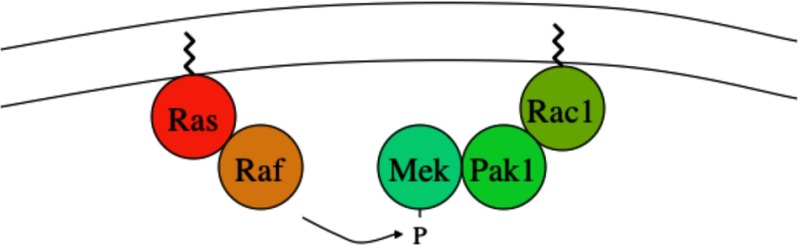

As a result, Rac1-mediated recruitment of MEK to the membrane increased the local concentration of MEK. This might facilitate the MEK1-dependent phosphorylation and activation of RAF that is recruited to the membrane by membrane-associated, activated Ras (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Activated Rac1 recruits PAK1 and MEK1 to the cell membrane, where MEK is phosphorylated by activated RAF bound to membrane-associated Ras.

DISCUSSION

PAK1 is widely up-regulated and hyperactivated in several human cancers, such as breast cancers, neurofibromatosis, and colorectal cancers (8, 10, 11). Although it has been shown by several groups that PAK1 regulates ERK-dependent proliferation, the molecular details of this process are not entirely clear. Our data suggest that PAK1 might contribute to ERK activation also in a kinase-independent manner, most possibly by facilitating MEK recruitment to the cell membrane.

About 30% of human tumors show hyperactivation of the MAPK pathway, represented by high phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 (12). Many in vitro studies have implicated PAK1 in the regulation of both C-RAF and MEK1 activity by directly phosphorylating these proteins at Ser-338 and Ser-298, respectively (3). Depletion of PAK1 expression decreased the activities of ERK and AKT, thereby inhibiting cell proliferation, migration/invasion, and survival, suggesting that PAK1 may act as a key molecule for transmitting signals from Ras and PI3K by activating downstream MEK/ERK and AKT pathways (13). We found previously that Rac1-controlled PAK1 activation is crucial in allowing activated C-RAF to interact with MEK1/2 to mediate ERK-dependent hyperproliferation in keratinocytes both in vivo and in vitro (7).

We report now that PAK1 is able to promote MEK1/2 phosphorylation in a kinase-independent manner, suggesting a scaffold function for PAK1 in addition to its kinase function. Already, earlier it was suggested that PAK1 has a kinase-independent scaffold function for the activation of AKT by recruiting AKT to the membrane. We have demonstrated in this study that PAK1 bound to membrane bound to membrane-associated, activated Ras (or RAF) can recruit MEK to the cell membrane. This will increase the local concentration of MEK at the cell membrane and by this mechanism promote MEK phosphorylation by activated RAF, which is indirectly associated to the cell membrane by binding to Ras. This recruitment will be important in those cases where normal diffusion of MEK to the cell membrane is not sufficient to saturate activated RAF. The lower the expression of MEK and the higher the activation of RAF, the more important the scaffold function of PAK is presumed to be. Future experiments should address the relative importance of the kinase-independent PAK function in vivo by xenotransplantation of cancer cells transfected with wild type and kinase-dead PAK1.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Steen Hansen for providing cDNAs for PAK1 WT and PAK1 K299R.

This work was supported by the Danish Cancer Foundation (to C. B.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81071689).

- PAK

- p21-activated kinase

- p-

- phosphorylated.

REFERENCES

- 1. Knaus U. G., Bokoch G. M. (1998) Interaction of the Nck adapter protein with p21-activated kinase (PAK1). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30, 857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bokoch G. M. (2003) Biology of the p21-activated kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 743–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Higuchi M., Onishi K., Kikuchi C., Gotoh Y. (2008) Scaffolding function of PAK in the PDK1-Akt pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1356–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Payne D. M., Rossomando A. J., Martino P., Erickson A. K., Her J. H., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Weber M. J., Sturgill T. W. (1991) Identification of the regulatory phosphorylation sites in pp42/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAP kinase). EMBO J. 10, 885–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. King A. J., Sun H., Diaz B., Barnard D., Miao W., Bagrodia S., Marshall M. S. (1998) The protein kinase Pak3 positively regulates Raf-1 activity through phosphorylation of serine 338. Nature 396, 180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Slack-Davis J. K., Eblen S. T., Zecevic M., Boerner S. A., Tarcsafalvi A., Diaz H. B., Marshall M. S., Weber M. J., Parsons J. T., Catling A. D. (2003) PAK1 phosphorylation of MEK1 regulates fibronectin-stimulated MAPK activation. J. Cell Biol. 162, 281–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang Z., Pedersen E., Basse A., Lefever T., Peyrollier K., Kapoor S., Mei Q., Karlsson R., Chrostek-Grashoff A., Brakebusch C. (2010) Rac1 is crucial for Ras-dependent skin tumor formation by controlling Pak1-Mek-Erk hyperactivation and hyperproliferation in vivo. Oncogene 29, 3362–3373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eswaran J., Li D. Q., Shah A., Kumar R. (2012) Molecular pathways: targeting p21-activated kinase 1 signaling in cancer: opportunities, challenges, and limitations. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 3743–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beeser A., Jaffer Z. M., Hofmann C., Chernoff J. (2005) Role of group A p21-activated kinases in activation of extracellular-regulated kinase by growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36609–36615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dummler B., Ohshiro K., Kumar R., Field J. (2009) Pak protein kinases and their role in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 51–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huynh N., Liu K. H., Baldwin G. S., He H. (2010) P21-activated kinase 1 stimulates colon cancer cell growth and migration/invasion via ERK- and AKT-dependent pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 1106–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dumesic P. A., Scholl F. A., Barragan D. I., Khavari P. A. (2009) Erk1/2 MAP kinases are required for epidermal G2/M progression. J, Cell Biol. 185, 409–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beeser A., Jaffer Z. M., Hofmann C., Chernoff J. (2005) Role of group A p21-activated kinases in activation of extracellular-regulated kinase by growth factors. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36609–36615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]