Abstract

♦ Introduction: After a training period, patients maintained on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) assume responsibility for their own treatment. With the aid of appropriate tools, home visits help with ongoing evaluation and training for these patients.

♦ Methods: We conducted a home visit survey of 50 patients maintained on CAPD in Sudan between April 2009 and June 2010. Housing conditions, home environment, and patient’s or caregiver’s knowledge about peritoneal dialysis and the exchange procedure were evaluated using structured data collection sheets. Scores were compared with infection rates in the patients before the home visit.

♦ Results: Patients were maintained on CAPD for a median duration of 11 months. Their mean age was 42 ± 23 years; 70% were male; and 14% had diabetes. Only 34% of patients had suitable housing conditions, and 56% required assisted PD. Of the autonomous patients and assisting family members, 11.6% were illiterate. The median achieved knowledge score was 11.5 of 35 points. The median achieved exchange score was 15 of 20 points. Knowledge and exchange scores were positively and significantly correlated (R = 0.5, p = 0.00). More patients in the upper quartile than in the middle and lower quartiles of knowledge scores were adherent to daily exit-site care (33.3% vs 5.3%, p = 0.02). Compared with patients in the middle and lower quartiles of knowledge score, patients in the upper quartile had lower rates of peritonitis, exit-site infection, and hospitalization.

♦ Conclusions: The proposed evaluation form is a valid and reliable assessment tool for the follow-up of CAPD patients. Patients in the upper quartile of knowledge score demonstrated better adherence to the recommended treatment protocols and lower infection rates.

Key words: Adherence, housing conditions, knowledge, peritonitis

After a training period, patients maintained on con tinuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) assume responsibility for their own treatment. The need for a home visiting service to manage this program of self-care is widely acknowledged (1-5). The provision of specialist community care for CAPD patients was reported to be associated with significant reductions in infections and hospital admissions (1). The development of home visit protocols has also been reported to be a valuable addition to continuous quality improvement projects in established PD centers (6).

Sudan currently has 7 active peritoneal dialysis (PD) units: 6 in Khartoum state and 1 in Al-Gezira state. The most recent unit was established in December 2008 as part of the adult nephrology service at Soba University Hospital in Khartoum. In that unit, strong emphasis is placed on application of the principles of the adult learning theory in patient education. Patients are evaluated in their own homes at the end of training and at regular intervals afterwards. For that purpose, we designed a concise evaluation form that focuses on practical aspects of PD-related knowledge in compliance with the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis recommendations (7). We also designed comprehensive checklists for the evaluation of PD-related procedures and the home environment. To ensure construct validity, those tools were reviewed and refined by a group of doctors and nurses with working experience in PD, and they were piloted in a small group of patients.

In the present study, we used those same tools to evaluate a group of prevalent PD patients who had been maintained on CAPD for variable durations in Sudan. The patients received conventional training upon initiation of dialysis in the other 6 PD units and were never visited in their homes by the PD team. We also evaluated the association between scores on the evaluation tools and infection rates before the home visit.

Methods

From an average of 70 active patients between April 2009 and June 2010, we made a convenience selection of 50 patients living in Khartoum or Al-Gezira state whose houses could be reached within working hours and who had never been visited by their PD nurse. All patients welcomed the visit, and the PD nurse who initially trained the patient accompanied the visiting team whenever possible. Considering the prevalent social conditions in Sudan, a house that contained more than one room and that had electricity and tap water supplies was considered suitable for PD regardless of the number of occupants.

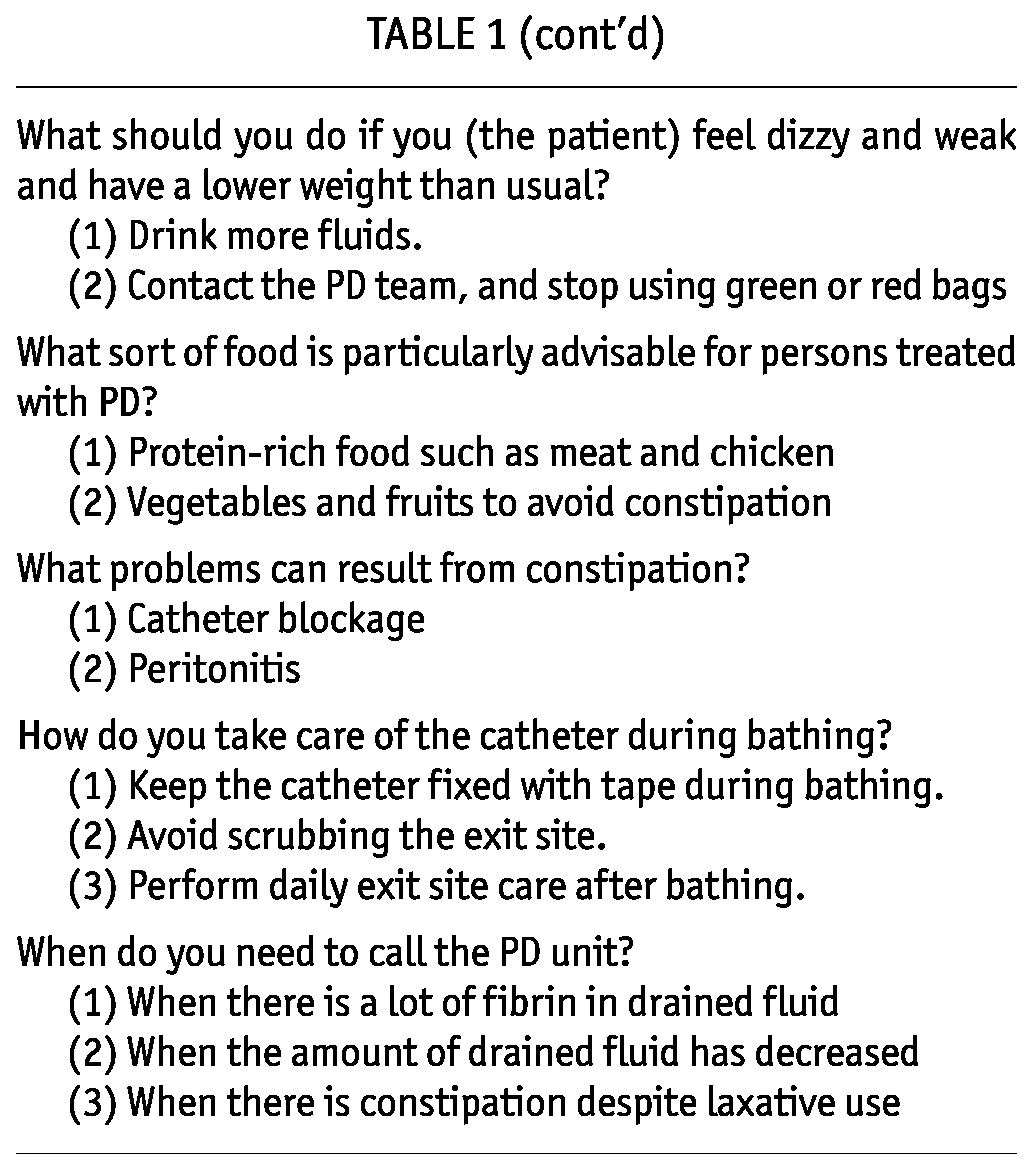

We evaluated the patient’s or caregiver’s knowledge about PD using a structured data collection sheet with a maximum possible score of 35 points (Table 1). We evaluated the home environment and the exchange technique using 10-item and 20-item checklists respectively. We also observed the patient’s or caregiver’s handwashing and exit-site cleaning techniques. Data related to the patient’s age, diabetes status, training duration, duration on PD, and number of peritonitis and exit-site infections and of hospital admissions before the home visit were collected through patient interviews and record review. During the home visit, after completion of the evaluation, patients were offered advice appropriate to their needs.

TABLE 1.

Evaluation Form Scoring Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) Patient Knowledge

The data analysis used SPSS for Windows (version 19: SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Proportions and median scores were compared using the chi-square test and the Mann-Whitney U-test. Patient knowledge and exchange scores were correlated using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

All patients (70% being male, 14% having diabetes) used twin-bag systems (Clear-Flex: Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL, USA). The median training duration was 6 days (range: 3 - 25 days), and the median duration on CAPD was 11 months (range: 1 - 40 months). Mean age of the patients was 42 ± 23 years in a population that included 12 children (24%) 18 years of age or younger and 10 elderly patients (20%) 65 years or age or older.

Only 17 patients (34%) had suitable housing conditions. Twenty-eight houses (56%) consisted of a single room, 22% lacked tap water, and 6% lacked an electrical supply. Practically all houses were clean, and patients were found wearing clean clothes, but 3 patients had untrimmed fingernails. Tables used by 14 patients (28%) for exchanges were unsuitable, being either too small to accommodate all the equipment or having rough surfaces that were difficult to clean. One patient used a hanger that was too short for the dialysis bag. Three patients stored supplies in unsuitable places. Of the 50 study patients, 28 (56%) required full assistance from their family members. That group included 11 children, 7 patients with poor eyesight, and 10 elderly and debilitated patients, and the knowledge and skills evaluation was therefore performed for the corresponding caregiver. Of the autonomous patients and family assistants, 11.6% were illiterate, 32.6% had some schooling, 27.9% had completed high school, and 27.9% had college or higher education. The median achieved knowledge score was 11.5 of 35 points, with a maximum score of 27 points. More than half the patients failed to give the following appropriate responses:

Abdominal pain and fever as signs of peritonitis

Handwashing and adherence to the recommended exchange technique as important ways of avoiding peritonitis

Daily exit-site care as an important way of avoiding exit-site infection

Stopping the exchange procedure as a necessary measure in the case of touch contamination

Modification of fluid intake as a necessary measure in the case of fluid overload or depletion

A high-fiber diet as an important measure to avoid constipation

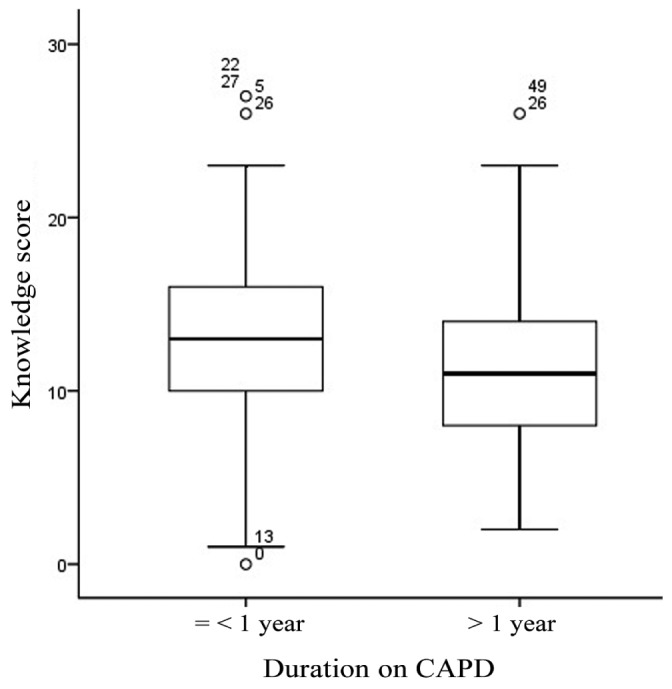

Age, education level, and duration on CAPD had no clear association with the achieved knowledge scores (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

— Duration on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) had no clear association with the knowledge scores achieved by the patients.

The median achieved exchange score was 15 of 20 points. Steps that were most commonly neglected were application of hand disinfectant before disconnection (84%), application of hand disinfectant before connection (78%), avoidance of air drafts (40%), washing hands with soap and water before the exchange (30%), examining the dialysate bag before the exchange (30%), replacing the catheter into the belt immediately after the exchange (30%), recording in the log book (28%), asking other family members to step outside during the exchange (22%), and inspecting the effluent (14%). Knowledge and exchange scores were positively and significantly correlated (R = 0.5, p = 0.00; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

—Knowledge scores were positively and significantly correlated with exchange scores.

Only 38% of patients and caregivers demonstrated proper handwashing technique. The commonest deficiency was inadequate scrubbing of all hand surfaces (52%) followed by use of unclean water (32%). One patient (2%) did not use soap at all, and four other patients (8%) used regular rather than antiseptic soap. Only 12% of patients reported adherence to daily exit-site care, and only 45% were able to demonstrate proper exit-site cleaning technique. In addition, 80% of patients did not wash their hands before cleaning the exit site and 86% did not apply a topical antibiotic after cleaning it. Compared with patients in the middle and lower quartiles, more patients in the upper quartile of knowledge score were adherent to daily exit-site care (33.3% vs 5.3%, p = 0.02). Compared with patients who were not adherent to daily exit-site care, adherent patients had a better median exit-site score (2 vs 3, p = 0.04).

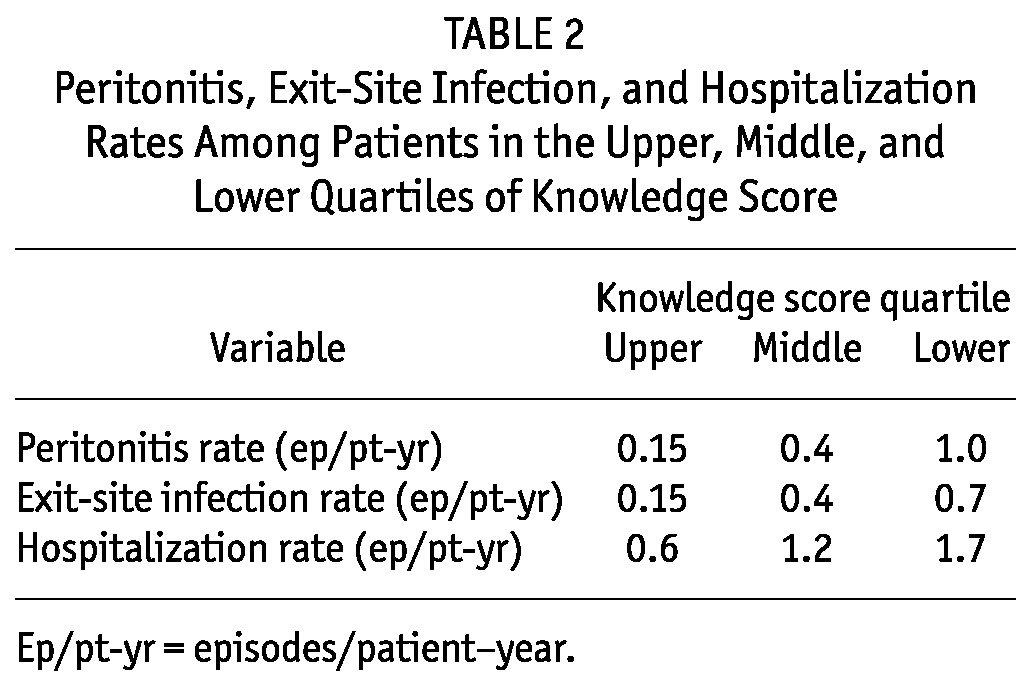

Overall peritonitis-free survival at 1 year was 77%. The overall peritonitis, exit-site infection, and hospitalization rates were 0.49, 0.39, and 1.16 episodes per patient-year respectively. Compared with patients in the middle and lower quartiles, patients in the upper quartile of knowledge score had lower rates of peritonitis, exit-site infection, and hospitalization (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Peritonitis, Exit-Site Infection, and Hospitalization Rates Among Patients in the Upper, Middle, and Lower Quartiles of Knowledge Score

Discussion

Sudan is ranked among the world’s least developed countries, and the socio-economic status of the study patients reflects the general socio-economic status in the country. Only one third of our patients had suitable housing conditions, but housing had no clear association with infection rates. With proper instruction, most patients were able to adapt their home environment for PD. Visiting patient homes allowed the PD nurse to detect minor problems and to suggest practical solutions.

The current survey revealed serious gaps in knowledge about PD among the patients. The lack of a significant difference between the knowledge scores of “new” and “old” patients and the rather wide range of scores in both groups indicate the possibility of various deficits in the initial patient training. In contrast, patients demonstrated better performance and less variability in their exchange technique. That finding may indicate that, during the initial training of most patients, more focus was placed on acquiring skills than on acquiring knowledge. Such variability in training content results from reliance on non-standardized conventional training methods.

Preparing patients for self-management is one of the most important aspects of patient education, and it has the greatest potential for benefit. According to the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis recommendations (7), formalized PD training programs must cover such aspects as emergency measures for contamination and potential complications (for example, peritonitis, fluid balance, drain problems, constipation, exit-site infection, fibrin blockages, and leaks). Training must continue until the patient is able to safely perform all required procedures, recognize contamination and infection, and list appropriate responses to potential problems (7).

Poor compliance with exchange technique is a common problem. Even after good training, some patients feel more secure with time and start skipping steps in the procedure. Patients can also make mistakes without being aware of them. In a multicenter study by Russo et al. (3), observation revealed that 23% of patients were not compliant with the exchange protocol recommendations aimed at preventing infections. The authors concluded that approximately one third of patients need reinforcement of knowledge and ability to correctly perform PD with respect to infection control. Dong and Chen (8) recently evaluated the bag exchange procedure of 130 patients who had been on CAPD for only 6 months. They reported that 51.5% of their patients washed their hands improperly and that 46.2% failed to check for expiration date or leakage before bag use.

The positive correlation between knowledge and exchange scores in the current study suggests that patients are more likely to adhere to recommended steps when they are aware of the significance of those steps. It may not be surprising that one third of patients neglected to wash their hands before the exchange because most patients did not mention handwashing as an important way of preventing peritonitis. Only a few patients reported adherence to daily exit-site care, and only a few patients said that daily exit-site care was important for preventing exit-site infection.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a clear relationship between knowledge about PD and infection rates. The great variability in the knowledge scores of the study patients probably facilitated the detection of this association despite the small number of patients. Knowledge scores as calculated in this study were also associated with better adherence to the exchange protocol, better adherence to the exit-site care protocol, and lower hospitalization rates, indicating that our knowledge evaluation form is a valid and reliable assessment tool for the follow-up of PD patients. This proposed knowledge questionnaire has additional merits when compared with other published knowledge evaluation forms (3,4). First, it focuses on practical aspects of PD-related knowledge that have clear implications for self-management. It does not include questions about drugs, physical activity, or tasks that are the responsibility of renal specialists (for example, transfer-set change). Second, it does not attempt to assess the patient’s behavior, attitude, or adherence. Those domains are important in the management of PD patients and are closely linked with patient’s knowledge, but they are not part of it. Third, the final score is easy to calculate and is based on a standard set of expected responses. It does not disregard “incomplete” answers.

Our study related current patient knowledge scores with their historic infection rates. That choice was based on the assumption that current knowledge scores would reflect patient knowledge levels during the preceding period. Once a patient is seen to have gaps in knowledge or skills, the PD team must promptly attempt to rectify those gaps. It is not ethical to leave such patients without retraining in an attempt to study how their lack of knowledge might affect infection rates.

By constructing and using our evaluation tools, we aim to enforce our commitment to the implementation of a standardized and structured PD training curriculum. We hope that this effort will have a positive impact on outcomes in our PD patients.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the PD patients and nurses who generously assisted us during this survey.

References

- 1. Warmington V. A home visit program for CAPD. Perit Dial Int 1996; 16(Suppl 1):S475–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Farina J. Peritoneal dialysis: a case for home visits. Nephrol Nurs J 2001; 28:423–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Russo R, Manili L, Tiraboschi G, Amar K, De Luca M, Alberghini E, et al. Patient retraining in peritoneal dialysis: why and when it is needed. Kidney Int Suppl 2006; (103):S127–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ozturk S, Yucel L, Guvenc S, Ekiz S, Kazancioglu R. Assessing and training patients on peritoneal dialysis in their own homes can influence better practice. J Ren Care 2009; 35:141–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kazancioglu R, Ozturk S, Ekiz S, Yucel L, Dogan S. Can using a questionnaire for assessment of home visits to peritoneal dialysis patients make a difference to the treatment outcome? J Ren Care 2008; 34:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nasso L. Our peritonitis continuous quality improvement project: where there is a will there is a way. CANNT J 2006; 16:20–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bernardini J, Price V, Figueiredo A on behalf of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) Nursing Liaison Committee Peritoneal dialysis patient training, 2006. Perit Dial Int 2006; 26:625–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dong J, Chen Y. Impact of the bag exchange procedure on risk of peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:440–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]