Methods commonly used for the insertion of peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheters are the surgical, laparoscopic, peritoneoscopic, and blind techniques. Blind insertion techniques include the Seldinger technique, the trochar method, and fluoroscopic guidance. Even though these techniques have evolved, most catheters are still being placed by a surgical technique. A recent report showed that only 2.3% of all catheter placements and 1% of laparoscopic insertions are performed by nephrologists (1). The involvement of other specialties and the associated need for interdepartmental coordination results in delays because of factors such as non-availability of a procedure room and the precedence of other surgical procedures and interventions over PD catheter placement.

Ultrasound guidance (USG) has been used to insert peritoneal catheters for palliation of malignant ascites (2). Contrast provided by the peritoneal fluid provides better visualization of the intraperitoneal structures and bowel loops (3). Maya (4) first described a fluoroscopic technique using additional USG to localize the epigastric artery and to observe the intraperitoneal entry of the introducer needle. That procedure provided additional safety by avoiding injury to the epigastric artery and related bleeding.

Developing countries have poor infrastructure, which limits the dissemination of PD as an alternative renal replacement therapy. We set out to use USG as the only guidance to balance the safety of a guided procedure with the risks of a blind procedure. Here, we describe the method we used.

Methods

Patients choosing to use continuous ambulatory PD (CAPD) and not having any contraindications for PD catheter insertion were selected after informed consent was obtained. Premedication with 1 g cefazolin was given 30 minutes before the procedure. Patients allergic to penicillin were given 500 mg vancomycin. Conscious sedation was given with intravenous midazolam and ketamine.

Grayscale ultrasonography of the abdominal wall was performed on the side where the insertion was planned to determine the thickest portion of the rectus abdominis muscle for implantation of the inner cuff and to ensure that no underlying bowel loops were present in that location. Color Doppler sonography was used to visualize the epigastric artery, and the puncture site was kept at least 2 - 3cm away from the artery. All catheters used were 62-cm Tenckhoff catheters with two cuffs, provided in a commercial kit (Quinton Curl Cath Peritoneal Catheter kit: Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA). The position of the deep cuff and the exit site were determined and marked.

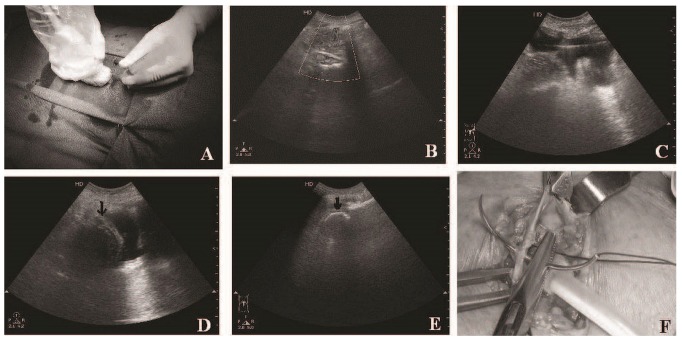

The entry site was then infiltrated with 10 mL 2% lignocaine, and the 18-gauge introducer needle (provided in the catheter kit) was inserted at an angle of 45 degrees, directed toward the pelvis under USG [Figure 1(A)]. The tip was positioned just under the peritoneum, avoiding underlying bowel loops.

Figure 1.

— (A) Using the ultrasound probe to direct the introducer needle. (B) Doppler ultrasonography shows a localized disturbance just under the peritoneum, because of the flow of peritoneal dialysis fluid into the peritoneal cavity. Deeper vessels can also be delineated. (C) The guidewire is seen in the pelvis, (D) followed by visualization of the catheter coil (black arrows) in the pelvis. (E) Catheter coil seen in another patient. (F) Anterior rectus sheath being closed over the deep cuff by applying a purse-string suture.

One liter of PD fluid was then instilled into the peritoneal cavity through the introducer needle. Free flow of the fluid was confirmed by demonstration of localized turbulence on Doppler USG [Figure 1(B)]. The presence of fluid in the pelvis and the separation of bowel loops was noted. A 1-mm J guidewire (provided in the catheter kit) was then inserted through the introducer needle, and with the peritoneal fluid providing contrast, the guidewire position was visualized in the pelvis [Figure 1(C)].

The introducer needle was then removed, and a 3-cm vertical incision was made at the insertion site. Subcutaneous tissue was dissected with sharp and blunt dissection to expose the anterior rectus sheath. A 0.5-cm transverse incision was made on the anterior rectus sheath, and a pocket big enough to accommodate the deep cuff was made in the rectus muscle. A purse-string suture was then applied around the rectus sheath using 1-0 nylon and was left without knotting.

The peel-apart sheath, together with the dilator (16F Pull-Apart Sheath/Dilator: Covidien) was threaded over the guidewire directed toward the pelvis. The guidewire and the dilator were then removed, and the PD catheter was inserted through the sheath into the peritoneal cavity. The deep cuff was advanced into the rectus muscle by peeling away the sheath. The position of the catheter coil in the pelvis was checked using grayscale ultrasonography [Figure 1(D,E)]. The 1-0 nylon suture was then tightened over the deep cuff, and fluid drainage was checked before the knot was tightened [Figure 1(F)].

The catheter was then placed in the subcutaneous tunnel created using the tunneling stylet (provided in the catheter kit) and was brought out at the exit site (made by a 0.5-cm stab incision). Free flow of the PD fluid was confirmed, and the catheter position in the pelvis was rechecked by USG. The subcutaneous tissue over the catheter was closed in layers using absorbable sutures (1-0 Vicryl: Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA), and the skin was closed with 1-0 silk sutures. The titanium adapter and connecting segment were then connected to the catheter, and free outflow of the instilled fluid was rechecked. The remaining 1 L of PD fluid was then instilled into the peritoneal cavity, and free inflow was again confirmed.

Finally, all fluid was drained and measured to ensure that the drained fluid totalled to at least 1800 mL. The connecting segment and the titanium adapter, together with the exposed portion of the catheter were covered with gauze, and a transparent dressing was applied.

Erect and supine radiographs of the abdomen were taken immediately post-procedure to check the position of the catheter and to rule out bowel perforation. The patient was instructed to avoid heavy lifting and excessive straining. Laxatives were also given to prevent constipation and straining at stools. The transparent dressing was checked daily for soakage and infection, and was changed on day 4, when small-volume (300 - 500 mL) flushing was initiated. The volume of the fluid flushes and the duration of the fluid dwells were gradually increased to achieve the desired volume and duration by day 10.

Results

Over a period of 6 months from January 2012 to June 2012, we inserted 21 PD catheters. No immediate procedure-related complications occurred, including bowel perforation or bleeding.

One patient had a previous abdominal wall hernia repair, and a surgical option was contraindicated. Because of multiple access failures and an urgent need for dialysis, a percutaneous insertion was attempted for this patient. On insertion of the guidewire on the left side, USG showed the wire coiled in the left hypochondrium because of adhesions in the left paracolic region (which was visualized because of the instilled fluid). We changed the site of insertion to the right side, and after demonstrating the presence of the guidewire in the pelvis, we inserted the catheter, which could also be demonstrated in the pelvis. This patient did not experience any procedure-related complications, and PD was initiated without any problems on day 4.

Dialysis was able to be initiated in 20 patients (95.23%) starting on post-procedure day 4, and full-volume exchanges were achieved by 10.23 ± 0.53 days in these 20 patients. Only 1 patient (4.76%) developed pericatheter leakage, and after a rest of 4 days, full-volume exchanges were achieved by post-procedure day 15. Only 1 episode of peritonitis occurred, on day 24 in a patient with end-stage renal disease related to systemic lupus erythematosus, which was adequately treated. Catheter position was rechecked on the day 30 by erect radiography of the abdomen, and no catheter malposition was documented.

Discussion

Good access to the pelvic peritoneum for placing the CAPD catheter is the most important aspect of PD. Direct visualization of the abdominal cavity using a laparoscopic approach has yielded results comparable to those using the open surgical technique, with the advantage of being able to perform additional procedures such as adhesiolysis (5). But both of those procedures require greater sophistication, including an operating theater and general anesthesia. Although modifications such as peritoneal helium insufflation (6) have been used to avoid the need for general anesthesia, the role of the nephrologist in conducting these procedures is restricted to just a few centers with good training in interventional nephrology.

The Seldinger technique is a blind procedure, and it has an inherent risk of complications such as bowel perforation and bleeding. Bowel perforation, the most dreaded early complication after PD catheter insertion, has been reported in 1% of patients (5). This complication usually occurs during the entry to the abdominal cavity or when the straightening stylet is advanced to the pelvis. Fluoroscopy has been used with comparable efficacy, especially by intervention radiologists, to ensure safe entry into the abdominal cavity and correct placement of the PD catheter in the pelvis (4).

Nonsurgical techniques using fluoroscopy have also shown advantages such as decreased procedure time and a very short time to CAPD initiation. Banli et al. (7) were able to initiate CAPD by day 6 after catheter insertion. Only 4.8% patients in their study had early pericatheter leakage, and none experienced bowel perforation. An Indian study also showed that blind PD catheter insertions by nephrologists resulted in shorter time to initiation of CAPD (4.6 ± 2.4 days vs 6.31 ± 2.68 days), shorter duration of hospital stay, and a cost reduction of 50% (8).

Insertion of the PD catheter using the Seldinger technique results in outcomes that are similar to those with the open surgical and laparoscopic methods. But the inherent bias of most of the studies toward selection of patients that have a more favorable safety profile for the Seldinger method (blind or fluoroscopy guided) has been highlighted in an editorial by Crabtree (9). Voss et al. (10), in a recently published randomized trial without that bias, compared fluoroscopy-assisted catheter insertion with laparoscopic catheter insertion. Those authors concluded that radiologic insertion is a clinically non-inferior and cost-effective alternative to surgical laparoscopic insertion. The long-term catheter survival rate was also higher in the radiologic insertion group in the study.

For percutaneous PD catheter insertion, fluoroscopy guidance is the only alternative method (short of a blind procedure) commonly used by intervention radiologists and nephrologists. But this facility is not available in most centers in the developing world. Involvement of the nephrologist in catheter insertion has been seen to lead to an increase of 22% - 32% in patients on CAPD; numbers decline when surgeons take over (11).

Initiation of CAPD can be accelerated by percutaneous methods that result in a shorter time to insertion, shorter time to initiation of PD, and comparable safety (12). Our method of using USG alone might make things simpler. The initial results have been encouraging. Short of the “blind” procedure, our technique can be used to “look into” the abdomen, reducing potential complications.

The limitations of our study are the small number of patients and their lower average body mass index of 22.13 ± 4.28 kg/m2. Thus, more experience with our USG procedure, especially in patients with a larger body mass index, is needed for further validation.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts interest to declare.

References

- 1. Crabtree JH. Who should place peritoneal dialysis catheters? Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:142–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Savader SJ. Percutaneous radiologic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1999; 10:249–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hanbidge AE, Lynch D, Wilson SR. US of the peritoneum. RadioGraphics 2003; 23:663–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maya ID. Ultrasound/fluoroscopy-assisted placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters. Semin Dial 2007; 20:611–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peppelenbosch A, van Kuijk WHM, Bouvy ND, van der Sande FM, Tordoir JHM. Peritoneal dialysis catheter placement technique and complications. NDT Plus 2008; 1(Suppl 4):iv23–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crabtree JH, Fishman A. A laparoscopic approach under local anesthesia for peritoneal dialysis access. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20:757–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Banli O, Altun H, Oztemel A. Early start of CAPD with the Seldinger technique. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25:556–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sampathkumar K, Mahaldar AR, Sooraj YS, Ramkrishnan M, Ajeshkumar Ravichandran R. Percutaneous CAPD catheter insertion by a nephrologist versus surgical placement: a comparative study. Indian J Nephrol 2008; 18:5–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crabtree JH. Fluoroscopic placement of peritoneal dialysis catheters: a harvest of the low-hanging fruits. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:134–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Voss D, Hawkins S, Poole G, Marshall M. Radiological versus surgical implantation of first catheter for peritoneal dialysis: a randomized non-inferiority trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:4196–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Asif A, Pflederer TA, Vieira CF, Diego J, Roth D, Agarwal A. Does catheter insertion by nephrologists improve peritoneal dialysis utilization? A multicenter analysis. Semin Dial 2005; 18:157–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li PK, Chow KM. Importance of peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion by nephrologists: practice makes perfect. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24:3274–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]