Abstract

Background

Data on outcomes of allogeneic transplantation in children with Down syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia (DS-AML) are scarce and conflicting. Early reports stress treatment-related mortality as the main barrier; a recent case series points to post-transplant relapse.

Design and methods

We reviewed outcome data for 28 patients with DS-AML reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) between 2000 and 2009 and performed a first matched-pair analysis of 21 patients with DS-AML and 80 non-DS AML controls.

Results

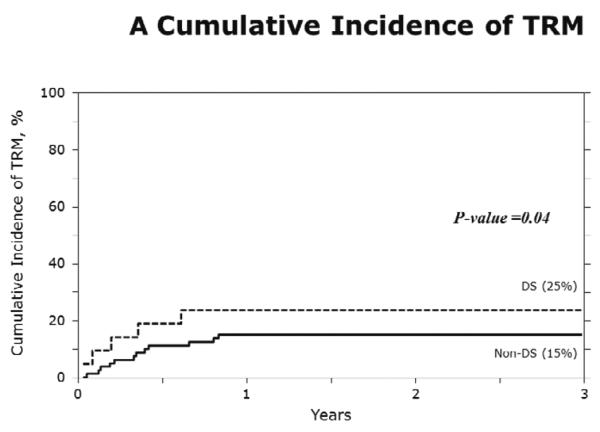

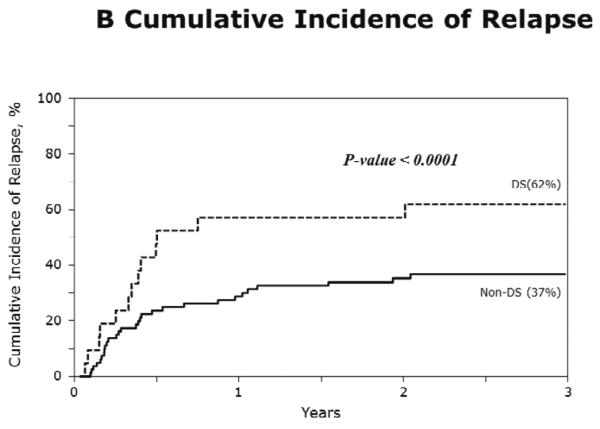

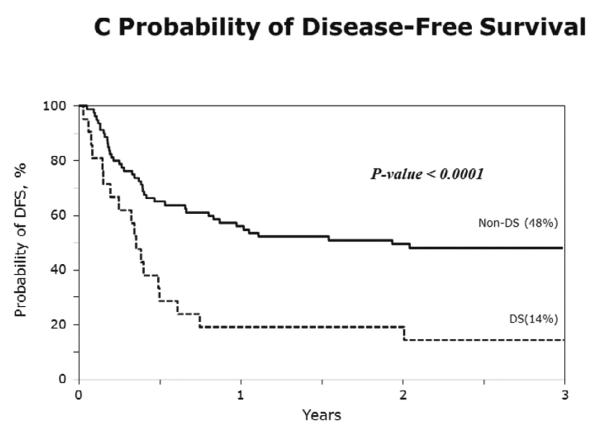

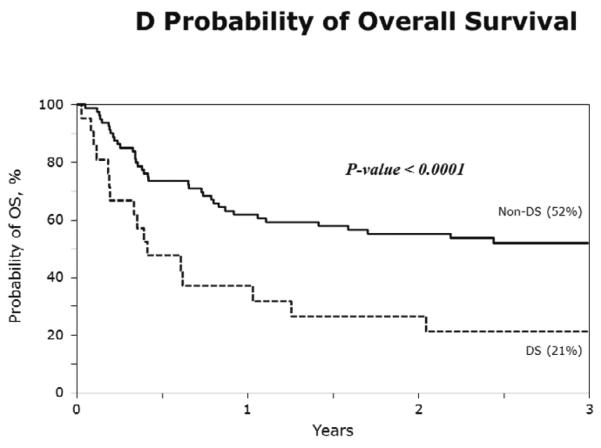

The median age at transplantation for DS-AML was 3 years and almost half of the cohort was in second remission. The 3-year probability of overall survival was only 19%. In multivariate analysis, adjusting for interval from diagnosis to transplantation, risks of relapse (HR 2.84, p<0.001; 62% vs. 37%) and transplant-related mortality (HR 2.52, p=0.04; 24% vs. 15%) were significantly higher for DS-AML compared to non-DS AML. Overall mortality risk (HR 2.86, p<0.001; 21% vs. 52%) was significantly higher for DS-AML.

Conclusions

Both transplant-related mortality and relapse contribute to higher mortality. Excess mortality in DS-AML patients can only effectively be addressed through an international multi-center effort to pilot strategies aimed at lowering both transplant-related mortality and relapse risks.

Keywords: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Down syndrome, trisomy 21, AML, ALL, relapse, pediatric

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is an integral part of treatment for high-risk acute myelogenous (AML) in children and adolescents. Disease-free survival (DFS) for pediatric AML after HCT ranges between 40% and 60%, and varies depending on donor and graft source (1–3). For patients with Down syndrome (DS) and acute leukemia, the role of HCT remains unclear. Children with DS (OMIM, #190685) have a 10–20 fold increased risk for acute leukemia compared to the general pediatric population(4). AML in DS (DS-AML) is characterized by a young age of onset, somatic mutations of the hematopoietic transcription factor GATA1 and excellent outcomes with chemotherapy (DFS 80% (5–7) due to the increased drug sensitivity of DS-AML blasts especially in the younger patients most of whom have M7 disease (8). Consequently HCT is not typically considered for DS-AML in first remission. For patients beyond first remission, allogeneic transplantation may be offered but data are scarce and the pattern of treatment failure is unclear. An earlier report of 27 patients with DS and AML or ALL suggested treatment-related mortality (TRM) was the predominant cause of treatment failure (9), while a later report of 11 patients suggested relapse as the primary cause of treatment failure (10). To our knowledge there are no reports that have directly compared transplant outcomes for AML in patients with or without DS. Therefore, to better define patterns of post-transplant treatment failure we conducted a matched-pair analysis of patients with DS-AML and non-DS AML.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data source

Data were obtained from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). The CIBMTR is a working group of more than 400 transplant centers worldwide that provide detailed patient, disease and transplant characteristics and outcomes on consecutive transplantations to the Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin or the Data-coordinating Center, National Marrow Donor Program. Participating centers report data on consecutive transplantations; all patients are followed longitudinally until death or lost to follow-up. Guardians provided written informed consent for data submission and research participation. The Institutional Review Boards of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the National Marrow Donor Program approved this study.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with DS-AML who received grafts from HLA-matched siblings, and matched or mismatched unrelated adult donors or umbilical cord blood were eligible. A similar population of non-DS AML patients served as controls. All transplantations occurred between 2000 and 2009. Transplantations prior to 2000 were excluded as a result of substantial changes in front-line chemotherapeutic regimens and supportive care after transplantation.

Risk Classification

Risk classification was assigned based on cytogenetic and molecular markers. Patients were classified into three risk groups: (11) the favorable risk group included the t(8;21), t(15;17) and inv(16) karyotypes; high risk was defined by the presence of −7, −5, del (5q), abnormalities of the long arm of chromosome 3 or complex karyotype that was defined as more than four abnormalities; all other AML karyotypes were classified as intermediate risk. Blast phenotype was not used for risk stratification or matching of cases and controls (see below). This approach is consistent with the exclusion of blast phenotype from contemporary prognostication and treatment stratification of AML in children with(5, 7, 12) and without DS(2, 11, 13). FLT3 mutations were not considered, as this information was not systematically collected in the early 2000s.

Outcomes

Neutrophil recovery was defined by an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥500/μl for three consecutive measurements; platelet recovery as a platelet count >20,000/μL for seven days without transfusion. Grade 2–4 acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and chronic GVHD were defined using standard criteria (14, 15). TRM was defined as death occurring in remission. Relapse was defined as morphological recurrence of leukemia at any site. DFS (inverse of treatment failure; relapse or death) was defined as survival in continuous complete remission. Surviving patients were censored at last contact.

Statistical analysis

The probability of neutrophil and platelet recovery, acute and chronic GVHD, TRM and relapse was calculated using the cumulative incidence function estimator (16). For neutrophil and platelet recovery and GVHD, death without the event was the competing risk. For TRM, relapse was the competing event and for relapse, TRM, the competing event. The probabilities of DFS and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan Meier estimator (16). 95% confidence intervals were calculated using log transformation. For overall survival, death from any cause was considered an event and for DFS, relapse or death were considered events.

Patients with DS-AML (cases) were matched to patients with non-DS AML (controls). Cases and controls were matched on disease status, risk group, donor and graft source and donor-recipient HLA match. Additionally, matched pairs with the smallest age difference between the case and controls were selected. Among the 28 patients with DS-AML, 7 patients were excluded from the matched analysis: age >18 years (n=1), reduced intensity conditioning regimen (n=1), absence of cytogenetic data (n=4), or control case not available (n=1). Twenty-one cases were matched to 80 controls from a population of 746 controls: 18 pairs matched 1:4, 2 pairs matched 1:3, and 1 pair matched 1:2. All patients included in the matched pair analysis received myeloablative transplant conditioning regimen. Cox regression models (16) were built to examine the risk of relapse, TRM, treatment failure and overall mortality for patients with DS-AML and non-DS AML. As cases and controls were matched on known prognostic factors, the only additional variable considered was interval from diagnosis to transplantation (≤12 vs. >12 months) to adjust for the prognostic impact of early relapse. All p-values are two-sided and value ≤0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient, disease and transplant characteristics for all patients with DS-AML are shown in Table 1. The median age at transplantation was 3 years; all patients were aged less than 18 years except for one patient who was aged 24 years. Forty-three percent of transplantations occurred in second remission and 39%, in relapse or after primary induction failure. Most patients were transplanted for early treatment failure as 64% of patients were transplanted within a year from diagnosis. All but one patient received myeloablative transplant-conditioning regimens. Grafts from mismatched unrelated donors or umbilical cord blood units each accounted for 40% of all transplantations and HLA-mismatching was almost entirely confined to the cord blood grafts. All patients received cyclosporine or tacrolimus containing GVHD prophylaxis and approximately 30% received methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil with the calcineurin inhibitor.

Table 1.

Patient, disease and transplant characteristics

| Number of patients | 28 |

| Number of transplant centers | 24 |

| Age, median (range), years | 3 (2–24) |

| ≤5 years | 25 |

| 6–18 years | 2 |

| >18 years | 1 |

| Lansky performance score | |

| <90 | 1 |

| 90–100 | 25 |

| Not reported | 2 |

| Disease status | |

| First complete remission | 5 |

| Second complete remission* | 12 |

| Relapse | 9 |

| Primary Induction failure | 2 |

| Blast phenotype (FAB) | |

| M0 | 2 |

| M1 | 1 |

| M2 | 3 |

| M3 | 0 |

| M4 | 1 |

| M5 | 0 |

| M6 | 0 |

| M7 | 16 |

| not specified | 5 |

| Risk group | |

| Intermediate risk | 16 |

| High risk | 6 |

| Not reported | 6 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | |

| ≤ 12 months | 18 |

| 13–36 months | 10 |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Total body irradiation + cyclophosphamide | 7 |

| Total body irradiation + other agents | 2 |

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide | 13 |

| Busulfan + fludarabine | 2 |

| Busulfan + melphalan | 4 |

| In vivo T-cell depletion (ATG or alemtuzumab) | |

| None | 18 |

| Yes | 10 |

| Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis | |

| Cyclosporine-containing | 22 |

| Tacrolimus-containing | 5 |

| Not reported | 1 |

| Donor type | |

| HLA-matched sibling (BM 1, PBSC 3, CB 0) | 4 |

| HLA-matched unrelated donor (BM 5, PBSC 2, CB 2) | 9 |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated donor (BM 2, PBSC 1, CB 12) | 15 |

| Graft type | |

| Bone marrow | 8 |

| Peripheral blood progenitor cells | 6 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 14 |

| Transplant period | |

| 2000 – 2005 | 17 |

| 2005 – 2009 | 11 |

| Median follow-up, (range), months | 47 (7 – 60) |

duration 4.8–22.0 months;

ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells; CB, cord blood

The probabilities of hematopoietic recovery, GVHD, TRM, relapse, DFS and OS are shown in Table 2. TRM rate was high but the relapse rate was substantially higher for DS-AML than non-DS AML patients. One patient with DS-AML aged 24 years was included in the unmatched analysis and should not have significantly influenced the aforementioned poor outcomes. An additional univariate analysis restricted to patients aged 18 years and younger at transplantation confirmed that no differences emerged when this young adult was excluded (data not shown). Only 4 of 28 patients are alive and disease-free. Of the 23 patients who are dead, 16 (70%) died of recurrent disease. Other causes of death include organ failure (n=4), hemorrhage (n=1), infection (n=1) and cause of death not reported (n=1). One patient who relapsed is alive at last follow-up.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis

| Outcomes | number events/evaluable | Probability (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil recovery | 24/28 | |

| at 28 days | 75 (58–89) | |

| Platelet recovery | 15/25 | |

| at 100 days | 52 (31–69) | |

| Grade 2–4 acute graft vs. host disease | 8/28 | |

| at 100 days | 29 (14–46) | |

| Chronic graft vs. host disease | 6/28 | |

| at 3 years | 23 (9–40) | |

| Transplant-related mortality | 7/28 | |

| at 100 days | 14 (4–29) | |

| at 3 years | 25 (11–42) | |

| Relapse | 17/28 | |

| at 3 years | 61 (42–78) | |

| Disease-free survival | 24/28 | |

| at 3 years | 14 (4–29) | |

| Overall survival | 23/28 | |

| at 3 years | 19 (7–36) |

The characteristics of cases (DS-AML; n=21) and controls (non-DS AML; n=80) are shown in Table 3. Figure 1A–D show the probabilities of relapse, TRM, DFS and overall survival of cases (DS-AML) and controls (non-DS AML). Consistent with the results of univariate analysis, in multivariate analysis, after adjusting for interval from diagnosis to transplantation, risks of TRM, relapse, treatment failure (inverse of DFS) and overall mortality are significantly higher in DS-AML patients compared to non-DS AML (Table 4).

Table 3.

Characteristics of DS-AML and non DS-AML patients matched for age, cytogenetic risk, disease status, donor and graft source and donor-recipient HLA-match

| Non DS-AML n(%) | DS-AML n(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 80 | 21 |

| Number of centers | 47 | 19 |

| Age | ||

| ≤ 5 years | 60 (75) | 19 (90) |

| 6–10 years | 14 (18) | 1 (5) |

| 11–18 years | 6 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 54 (68) | 13 (62) |

| Female | 26 (33) | 8 (38) |

| Lansky performance score | ||

| <90 | 16 (20) | 1 (5) |

| >=90 | 60 (75) | 18 (86) |

| Unknown | 4 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, months (m) | ||

| ≤12 m | 46 (58) | 13 (62) |

| 13–36 months | 34 (43) | 8 (38) |

| Disease status prior to transplant | ||

| First remission | 16 (20) | 4 (19) |

| Second remission | 36 (45) | 9 (43) |

| Relapse | 16 (20) | 7 (33) |

| Primary induction failure | 12 (15) | 1 (5) |

| Blast phenotype (FAB) | ||

| M0 | 3 (4) | 2 (10) |

| M1 | 5 (6) | 1 (5) |

| M2 | 15 (19) | 1 (5) |

| M3 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| M4 | 5 (6) | 1 (5) |

| M5 | 25 (31) | 0 |

| M6 | 3 (4) | 0 |

| M7 | 10 (13) | 12 (57) |

| Not specified | 13 (16) | 4 (19) |

| Risk groups | ||

| Intermediate risk | 67 (84) | 17 (81) |

| High risk | 13 (16) | 4 (19) |

| Conditioning regimen | ||

| Total body irradiation + cyclophosphamide | 38 (48) | 6 (29) |

| Total body irradiation + other agents | 4 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide | 25 (31) | 10 (48) |

| Busulfan + fludarabine | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Busulfan + melphalan | 9 (11) | 3 (14) |

| Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis | ||

| Cyclosporine-containing | 64 (80) | 15 (71) |

| Tacrolimus-containing | 11 (14) | 5 (24) |

| Methotrexate | 3 (3) | 0 |

| Not reported | 3 (3) | 1 (5) |

| Donor type | ||

| HLA-matched sibling | 4 (5) | 1 (5) |

| BM | 0 | 0 |

| PBSC | 4 | 1 |

| CB | 0 | 0 |

| Matched unrelated | 33 (41) | 9 (43) |

| BM | 20 | 5 |

| PBSC | 5 | 2 |

| CB | 8 | 2 |

| Mismatched unrelated | 43 (54) | 11 (52) |

| BM | 4 | 1 |

| PBSC | 4 | 1 |

| CB | 35 | 9 |

| Graft type | ||

| Bone marrow | 24 (30) | 6 (29) |

| Peripheral blood progenitor cells | 13 (16) | 4 (19) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 43 (54) | 11 (52) |

| Median (range) follow-up, months | 37 (3 – 120) | 47 (7 – 60) |

BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells; CB, cord blood

Figure. 1.

A) The 3-year probabilities of TRM: 24% (95% CI 9–44) and 15% (95% CI 8–24) for DS-AML and non-DS AML, respectively, (p=0.04);

B) The 3-year probabilities of relapse: 62% (95% CI 41 – 81) and 37% (95% CI 27 – 48), for DS-AML and non-DS AML, respectively, p<0.001;

C) The 3-year probabilities of DFS: 14% (95% CI 3–32) and 48% (95% CI 37–59) for DS-AML and non-DS AML, respectively, p<0.001;

D) The 3-year probabilities of overall survival: 21% (95% CI 6–42) and 52% (95% CI 41–63), for DS-AML and non-DS AML, respectively p<0.001.

Table 4.

Results of multivariate analysis of DS-AML and non DS-AML matched pair

| Relative Risk (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Transplant-related mortality | ||

| DS-AML vs. non DS-AML* | 2.52 (1.06 – 6.00) | 0.04 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant ≤12 month vs. 13 –36 month* | 2.17 (0.75 – 6.25) | 0.15 |

| Relapse | ||

| DS-AML vs. non DS-AML* | 2.84 (1.75 – 4.59) | <0.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant ≤12 month vs. 13 – 36 month* | 1.43 (0.76 – 2.63) | 0.27 |

| Treatment failure | ||

| DS-AML vs. non DS-AML* | 2.75 (1.75 – 4.31) | <0.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant ≤12 month vs. 13 – 36 month* | 1.59 (0.92 – 2.78) | 0.10 |

| Overall mortality | ||

| DS-AML vs. non DS-AML* | 2.86 (1.77 – 4.64) | <0.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant ≤12 month vs. 13 – 36 month* | 1.89 (1.05 – 3.45) | 0.03 |

Reference group

DISCUSSION

While chemotherapy approaches are now well defined for DS-AML(5, 7, 8, 17–20), the role of allogeneic transplantation has been limited to case reports and small series (21) that are more pertinent to previous treatment eras (22), and the results are conflicting (9, 10)(9, 22). Our current analysis sought to delineate the relative contributions of TRM and relapse to treatment failure after allogeneic transplantation in a relatively large contemporary cohort of patients with DS-AML and our findings confirm that high rates of TRM and relapse both play a role. Confirmation of this observation was strengthened by the additional matched pair analyses of DS-AML and non-DS AML patients which adjusted for risk factors associated with transplantation outcomes. High rates of treatment failure led to an overall survival rate of only 21% after transplantation for DS-AML compared to 52% for non-DS AML.

It is tempting to attribute high relapse rates in our DS-AML cohort to the 39% of patients whose leukemia was active at transplantation. However, results from our matched pair comparison do not support this notion. Therefore, the reported overall favorable prognosis of DS-AML at time of original diagnosis appears to reflect outcomes in two different risk settings: one where over 80% of patients achieve long term remission with lower intensity chemotherapy alone (5–7) and a smaller percentage, who respond poorly to up front therapy(23) as manifest by early relapse and inability to achieve complete remission after a relapse.

The current analysis used data reported to a transplant registry. A significant limitation is the heterogeneity of the patients with respect to their disease status at transplantation and transplant-conditioning regimen. However, we were able to perform a carefully controlled analysis adjusting for the known risk factors that influence transplantation outcomes. The observed poor outcome may be attributed to differences in the biology of DS-AML and/or the intensity of front-line chemotherapy regimens used in these patients compared to non-DS AML patients. Another plausible explanation could be the presence of minimal residual disease (MRD) at transplantation; data on MRD were not collected during the study period and is a limitation.

Our data suggest a reduction in TRM remains desirable, but the data also highlight the importance of leukemia recurrence as a major cause of treatment failure. Therefore, the decision to offer transplant for DS-AML must consider the excess risk of leukemia recurrence after transplantation even for those who attain remission after an initial relapse in addition to TRM risks. One strategy to improve survival could focus on carefully selecting transplant candidates such as those in morphological remission and MRD negative. Other strategies include planned post-transplant therapy to ensure better leukemia control post-transplant. Lowering TRM risks remains a challenge in these patients; full intensity regimens, which offer leukemia control, are offset by life-threatening infections and/or organ toxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and HHSH234200637015C, from the Health Resources and Services Administration. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

J.K.H., J.D., M.E. and P.A.C. designed the study design and interpreted data. J.K.H. and M.E. drafted the manuscript. W.H. prepared the dataset. W.H. and M.J.Z. did the statistical analysis. W.H., M.C., B.M.C., K.W.C., M.A.D., C.F., T.G.G., J.T.H., A.A.K.N., C.K., J.K., L.L., T.O.B., M.A.P., F.O.S., M.J.Z. and P.A.C. interpreted data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: There is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Horan JT, Alonzo TA, Lyman GH, Gerbing RB, Lange BJ, Ravindranath Y, et al. Impact of disease risk on efficacy of matched related bone marrow transplantation for pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: the Children's Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Dec 10;26(35):5797–801. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson BE, Wheatley K, Hann IM, Stevens RF, Webb D, Hills RK, et al. Treatment strategy and long-term results in paediatric patients treated in consecutive UK AML trials. Leukemia. 2005 Dec;19(12):2130–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw PJ, Kan F, Woo Ahn K, Spellman SR, Aljurf M, Ayas M, et al. Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2010 Nov 11;116(19):4007–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261958. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasle H, Clemmensen IH, Mikkelsen M. Risks of leukaemia and solid tumours in individuals with Down's syndrome. Lancet. 2000 Jan 15;355(9199):165–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creutzig U, Reinhardt D, Diekamp S, Dworzak M, Stary J, Zimmermann M. AML patients with Down syndrome have a high cure rate with AML-BFM therapy with reduced dose intensity. Leukemia. 2005 Aug;19(8):1355–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo K, Kojima S, Tabuchi K, Yabe H, Tawa A, Imaizumi M, et al. Prospective Study of a Pirarubicin, Intermediate-Dose Cytarabine, and Etoposide Regimen in Children With Down Syndrome and Acute Myeloid Leukemia: The Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Dec 1;25(34):5442–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3687. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorrell AD, Alonzo TA, Hilden JM, Gerbing RB, Loew TW, Hathaway L, et al. Favorable survival maintained in children who have myeloid leukemia associated with Down syndrome using reduced-dose chemotherapy on Children's Oncology Group trial A2971: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2012 Mar 5; doi: 10.1002/cncr.27484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taub JW, Ge Y. Down syndrome, drug metabolism and chromosome 21. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005 Jan;44(1):33–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin CM, Mick R, Johnson FL. Bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of haematological disorders in Down's syndrome: toxicity and outcome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996 Sep;18(3):533–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meissner B, Borkhardt A, Dilloo D, Fuchs D, Friedrich W, Handgretinger R, et al. Relapse, not regimen-related toxicity, was the major cause of treatment failure in 11 children with Down syndrome undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute leukaemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007 Nov;40(10):945–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheatley K, Burnett AK, Goldstone AH, Gray RG, Hann IM, Harrison CJ, et al. A simple, robust, validated and highly predictive index for the determination of risk-directed therapy in acute myeloid leukaemia derived from the MRC AML 10 trial. British Journal of Haematology. 1999;107(1):69–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gamis AS, Alonzo TA, Hilden JM, Gerbing RB, Loew TW, Hathaway L, et al. Outcome of Down Syndrome (DS) Children with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) or Myelodysplasia (MDS) Treated with a Uniform Prospective Clinical Trial - Initial Report of the COG Trial A2971. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts; 2006 November 16; p. 15. 2006. - [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creutzig U, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Gibson B, Dworzak MN, Adachi S, de Bont E, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents: recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2012 Oct 18;120(16):3187–205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-362608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flowers ME, Kansu E, Sullivan KM. Pathophysiology and treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999 Oct;13(5):1091–112. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70111-8. viii-ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann H, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1995;15(6):825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein J, Moeschberger M. Survival analysis: Techniques of censored and truncated data. 2nd ed. Springer Verlag; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gamis AS. Acute myeloid leukemia and Down syndrome evolution of modern therapy--state of the art review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005 Jan;44(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwaan CM, Kaspers GJ, Pieters R, Hahlen K, Janka-Schaub GE, van Zantwijk CH, et al. Different drug sensitivity profiles of acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia and normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells in children with and without Down syndrome. Blood. 2002 Jan 1;99(1):245–51. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hitzler JK, Zipursky A. Origins of leukaemia in children with Down syndrome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005 Jan;5(1):11–20. doi: 10.1038/nrc1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange BJ, Kobrinsky N, Barnard DR, Arthur DC, Buckley JD, Howells WB, et al. Distinctive demography, biology, and outcome of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome in children with Down syndrome: Children's Cancer Group Studies 2861 and 2891. Blood. 1998 Jan 15;91(2):608–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goleta-Dy A, Dalla Pozza L, Shaw PJ, Stevens MM. Acute myeloid leukaemia in patients with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) treated by bone marrow transplantation. J Paediatr Child Health. 1994 Jun;30(3):275–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1994.tb00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arenson EB, Jr., Forde MD. Bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia and Down syndrome: report of a successful case and results of a national survey. J Pediatr. 1989 Jan;114(1):69–72. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taga T, Saito AM, Kudo K, Tomizawa D, Terui K, Moritake H, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of refractory/relapsed myeloid leukemia in children with Down syndrome. Blood. 2012 Aug 30;120(9):1810–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414755. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]