Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the incidence and distribution of specific types of parkinsonism and related proteinopathies.

Design

We used the medical records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project to identify all subjects who received a screening diagnostic code of interest. A movement disorders specialist reviewed the complete medical records of each subject to confirm the type of parkinsonism and the presumed proteinopathy using specified criteria.

Setting

Olmsted County, MN, from 1991 through 2005 (15 years)

Participants

All residents of Olmsted County, MN

Main Outcome Measure

Incidence of parkinsonism

Results

Among 542 incident cases of parkinsonism, 409 (75.5%) were classified as proteinopathies. Of 389 patients with presumed synucleinopathies (71.8% of cases), 264 had Parkinson's disease (48.7% of all cases). The incidence rate (per 100,000 person-years) of synucleinopathies was 21.0 overall and increased steeply with age. The incidence rate of tauopathies was 1.1 overall (20 cases) and the most common tauopathy was progressive supranuclear palsy (16 cases). Thirty-six subjects had drug-induced parkinsonism (6.6%), 11 had vascular parkinsonism (2.0%), 1 had amyotropic lateral sclerosis in parkinsonism (0.2%), 1 had parkinsonism secondary to surgery (0.2%), and 84 remained unspecified (15.5%). Men had higher incidence than women for most types of parkinsonism. Findings at brain autopsy confirmed the clinical diagnosis in 53 out of 65 patients who underwent autopsy (81.5%).

Conclusions

The incidence of proteinopathies related to parkinsonism increases steeply with age and is consistently higher in men than women. Clinically-diagnosed synucleinopathies are much more common than tauopathies. Findings at autopsy confirm the clinical diagnosis.

Keywords: incidence, sex differences, epidemiology, pathology, proteinopathies, synucleinopathies, tauopathies

In the United States, as in many countries world-wide, life expectancy has increased dramatically in the past century. With more of the population living to older ages, a larger number of persons are expected to develop a neurodegenerative disorder. A recent study estimated that the prevalence of Parkinson's disease (PD) and related disorders will increase dramatically in the next decades.1

Several studies assessed the incidence of PD and other parkinsonisms.2–4 Although all of the studies confirmed that PD is the most common type,2 the data regarding other types of parkinsonism remain limited because the diagnosis is difficult and the diseases are relatively rare.5, 6 Neurodegenerative conditions have now been classified also on the basis of the presumed underlying protein substrates. Because alpha-synuclein is the predominant protein associated with PD, other Lewy Body disorders, and with multiple system atrophy (MSA), these conditions have been termed synucleinopathies.7, 8 Similarly, parkinsonisms thought to be related to microtubule-associated protein tau have been termed tauopathies.9 This group includes progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and many cases of corticobasal syndrome (CBS). In this study, we investigated the incidence and the distribution by age and sex of clinically-diagnosed proteinopathies related to parkinsonism in a well-defined population over a 15-year period. For a subsample of our patients, we were able to validate our clinical diagnosis at autopsy.

METHODS

Study Population

We studied the geographically defined population of Olmsted County, located in southeastern Minnesota, USA from January 1, 1991 through December 31, 2005 (incidence study period of 15 years). Extensive details about the Olmsted County population were reported elsewhere.10–13 The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Mayo Clinic and of Olmsted Medical Center. Written informed consent was not required for passive medical record review.11

Case Ascertainment

We ascertained cases of parkinsonism through the records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. This system provides the infrastructure for indexing and linking essentially all medical information of the county population.10–13 All medical diagnoses, surgical interventions, and other procedures are entered into computerized indexes using codes from the Hospital Adaptation of the International Classification of Diseases – 8th Revision (H-ICDA) or the International Classification of Diseases – 9th Revision (ICD-9).14, 15

We ascertained potential cases of parkinsonism using a computerized screening phase and a clinical confirmation phase. In phase 1, we searched the indexes for 31 H-ICDA and 7 ICD-9 diagnostic codes: 5 codes for PD, 14 for parkinsonism, 7 for tremor, 2 for extrapyramidal disorders, 5 for non-specific neurodegenerative diseases, 2 for multiple system atrophy, and 3 for progressive supranuclear palsy. These 38 codes were the smallest subset of codes which completely captured all cases of parkinsonism in a previous study of the incidence of parkinsonism performed in the same population from 1976 to 1990 (the list is reported in eTable 1).6 This list of 38 codes was designed to yield maximum sensitivity at the cost of low specificity, because the clinical confirmation phase was relatively rapid and did not involve the participants (no burden to study subjects).

eTable 1.

List of codes from the International Classification of Diseases used to search the electronic indexes

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| H-ICDA Codes | |

| 03339113 | Disease, brain, degenerative, hereditary |

| 03339510 | Tremor, familial |

| 03339521 | Tremor, rest |

| 03420110 | Disease, Parkinson's |

| 03420111 | Paralysis, agitans |

| 03420114 | Parkinsonism, NOS |

| 03420120 | Parkinsonian features |

| 03420121 | Disease, diffuse Lewy Body |

| 03420122 | Body, Lewy |

| 03420210 | Hemiparkinsonism, NOS |

| 03420430 | Parkinsonism, drug-induced |

| 03420600 | Parkinsonism, dementia complex |

| 03420601 | Parkinsonism, with dementia |

| 03420604 | Parkinson's plus (code also additional condition stated) |

| 03420810 | Tremor, senile |

| 03420811 | Tremor, Parkinson's |

| 03449711 | Paralysis, supranuclear |

| 03449717 | Paralysis, supranuclear, progressive |

| 03449722 | Syndrome, Steele-Richardson-Olszewski |

| 03479131 | Degeneration, olivopontocerebellar |

| 03479413 | Disease, CNS, degenerative |

| 03479416 | Degeneration, brain, NOS |

| 03479720 | Syndrome, extrapyramidal (movement) |

| 03479751 | Degeneration, striatonigral |

| 03479821 | Atrophy, multiple system (CNS) |

| 03479880 | Syndrome, basal ganglion |

| 07732210 | Tremor, NOS |

| 07732220 | Tremor, essential |

| 07732340 | Syndrome, bradykinetic, atypical (movement) |

| 07732341 | Bradykinesia (movement disorder) |

| 07734510 | Tremor, intention |

| ICD-9 Codes | |

| 331.9 | Cerebral degeneration, unspecified |

| 332.0 | Paralysis agitans |

| 332.1 | Secondary parkinsonism |

| 333.0 | Other degenerative diseases of the basal ganglia |

| 333.1 | Essential and other specified forms of tremor |

| 781.0 | Abnormal involuntary movements |

| 781.3 | Lack of coordination |

In phase 2, a movement disorders specialist (R.S.) reviewed the complete records of all persons who received at least one of these diagnostic codes during the 15-year incidence study period or in the following 5 years, using a specifically designed data abstraction form that was computerized for direct data entry (clinical confirmation phase). We extended the search for incident cases of parkinsonism for 5 years after the incidence study period (2006 – 2010) to insure that persons with delayed diagnosis could be correctly counted. The movement disorders specialist defined the approximate date of onset and the type of parkinsonism using specified diagnostic criteria and following a manual of instructions (Table 1).6, 16–20 Onset of PD was defined as the approximate date in which 1 of the 4 cardinal signs of PD was first noted by the patient, by family members, or by a care provider (as documented in the medical record).

Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinsonisms and for Proteinopathies

Our diagnostic criteria included two steps: the definition of parkinsonism as a syndrome and the definition of types of parkinsonism within the syndrome. Parkinsonism was defined as the presence of at least two of four cardinal signs: rest tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and impaired postural reflexes. Among the persons who fulfilled the criteria for parkinsonism, we applied the diagnostic criteria listed in Table 1 to classify the type of parkinsonism. In addition, we used clinical characteristics to group patients with parkinsonism into presumed synucleinopathies or presumed tauopathies.7–9 Synucleinopathies included PD, parkinsonism with dementia, and MSA.7–8 Tauopathies included PSP and CBS.9

Patients with uncertain underlying proteinopathy were included in the category “other types of parkinsonism.” This category included patients who did not have enough clinical information to fulfill the criteria for a particular type of parkinsonism (parkinsonism unspecified) and patients with types of parkinsonism not associated with a specific pathological hallmark (e.g., drug-induced parkinsonism, vascular parkinsonism, and secondary parkinsonism).

Reliability and Validity of Diagnosis and Classification

To study the reliability of our case-finding procedure, 40 records reviewed by the primary movement disorders specialist (R.S.) were independently reviewed by a second movement disorders specialist (J.H.B.) who was kept unaware of the initial diagnosis. The 40 records were selected randomly among those classified by the primary neurologist as parkinsonism (15 records), Parkinson's disease (15 records), and parkinsonism excluded after screening positive (10 records). Agreement on presence of parkinsonism or PD was 90.0% (27 out of 30). The three disagreements involved persons diagnosed as PD, drug-induced parkinsonism, or vascular parkinsonism by the primary neurologist and excluded by the second neurologist. Agreement on exclusion of parkinsonism in subjects who screened positive was 70.0% (7 out of 10). The three disagreements involved persons found to have PD, drug-induced parkinsonism, and parkinsonism unspecified by the second neurologist.

For the 27 subjects found to be affected by parkinsonism by both neurologists, the agreement was 74.1% (20 out of 27) for PD versus other type of parkinsonism and 85.2% (23 out of 27) for synucleinopathy versus other type. Finally, for the subjects found to be affected by parkinsonism by both neurologists, the agreement on year of onset of symptoms was within 1 year in 21 subjects (77.8%) and within 3 years for 26 of the 27 subjects (96.3%). In general, the agreement regarding the year of onset was high (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0.85; 95% CI 0.77–0.92).21

To validate the classification in presumed synucleinopathies and tauopathies, we reviewed the autopsy reports for all the patients who died during the study and for whom an autopsy was available. Detailed results of the validation study are reported in the Results section.

Statistical Analysis

We excluded subjects who denied authorization to use their medical records for research.11 All individuals who met criteria for parkinsonism with symptom onset between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2005, and who were residents of Olmsted County at the time of symptom onset were included as incident cases. We calculated incidence rates using incident cases as the numerator and population counts from the Rochester Epidemiology Project Census as the denominator.11 The denominator was corrected by removing prevalent cases of parkinsonism estimated using prevalence figures from several European populations.22 Details about this correction were published elsewhere.6

We computed age- and sex-specific incidence rates for parkinsonism overall, for specific subtypes of parkinsonism, and for specific proteinopathies. Because our study was descriptive and involved the entire Olmsted County population, no sampling procedures were involved and statistical tests were not necessary for the interpretation of the data.23

RESULTS

We identified 5,505 individuals with at least one screening code of interest from 1991 through 2010. We excluded 400 individuals because they were not residents of Olmsted County at the time of onset of symptoms and 136 persons because they did not give permission to use their medical records for research. Of the 4,969 remaining persons, 3,877 were found not affected by parkinsonism at record review, 12 lacked sufficient clinical documentation to determine their parkinsonism status, 374 had onset of parkinsonism before January 1, 1991, and 164 persons had onset after December 31, 2005. In summary, we included 542 incident cases of parkinsonism with onset between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2005. Only 35 persons (6.5%; 18 with PD) received a first screening diagnostic code after December 31, 2005 but had the onset of parkinsonism retro-dated to within the study period (1991–2005).

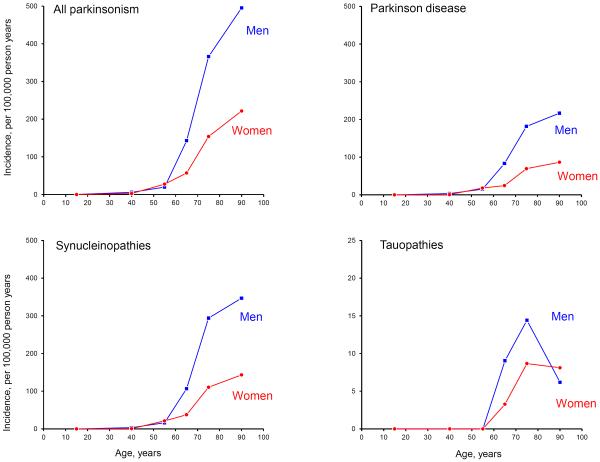

Table 2 shows the age- and sex-specific incidence rates for presumed synucleinopathies, presumed tauopathies, and for other types of parkinsonism. Figure 1 shows the age- and sex-specific incidence rates of all parkinsonisms, PD, synucleinopathies, and tauopathies. Of the 542 patients identified, 389 cases had clinically-presumed synucleinopathies (71.8%), 20 cases had clinically-presumed tauopathies (3.7%), and 133 cases had other types of parkinsonism (24.5%; Table 2). The overall incidence rate for parkinsonism of all types was 29.3 cases per 100,000 person-years. Incidence rates increased sharply with age from 97.9 at age 60 to 69 years to 304.8 at age 80 to 99 years (Figure 1).

TABLE 2.

Incidence rates (per 100,000 person-years) of specific types of parkinsonism and proteinopathies in Olmsted County, MN, 1991–2005a

|

Age group, yr

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Parkinsonism | 0–29 Rate (No.) | 30–49 Rate (No.) | 50–59 Rate (No.) | 60–69 Rate (No.) | 70–79 Rate (No.) | 80–99 Rate (No.) | All ages Rate (No.) |

| Any parkinsonism | 0.1 (1) | 4.2 (24) | 23.8 (43) | 97.9 (114) | 245.0 (198) | 304.8 (162) | 29.3 (542) |

| Men | 0.2 (1) | 5.8 (16) | 19.7 (17) | 142.9 (79) | 366.0 (127) | 495.2 (80) | 36.0 (320) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 2.7 (8) | 27.6 (26) | 57.2 (35) | 153.9 (71) | 221.7 (82) | 23.0 (222) |

| Synucleinopathies | 0.0 (0) | 1.9 (11) | 18.8 (34) | 70.4 (82) | 189.3 (153) | 205.1 (109) | 21.0 (389) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (9) | 16.2 (14) | 106.7 (59) | 294.0 (102) | 346.6 (56) | 27.0 (240) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.7 (2) | 21.2 (20) | 37.6 (23) | 110.5 (51) | 143.3 (53) | 15.4 (149) |

| Parkinson's disease | 0.0 (0) | 1.9 (11) | 16.6 (30) | 52.4 (61) | 117.5 (95) | 126.1 (67) | 14.2 (264) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (9) | 15.0 (13) | 83.2 (46) | 181.6 (63) | 216.7 (35) | 18.7 (166) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.7 (2) | 18.0 (17) | 24.5 (15) | 69.4 (32) | 86.5 (32) | 10.2 (98) |

| Parkinsonism with dementia | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.6 (1) | 13.7 (16) | 64.3 (52) | 77.2 (41) | 5.9 (110) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.2 (1) | 14.5 (8) | 98.0 (34) | 123.8 (20) | 7.1 (63) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 13.1 (8) | 39.0 (18) | 56.8 (21) | 4.9 (47) |

| Multiple system atrophy | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.7 (3) | 4.3 (5) | 7.4 (6) | 1.9 (1) | 0.8 (15) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 9.0 (5) | 14.4 (5) | 6.2 (1) | 1.2 (11) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 3.2 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 2.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.4 (4) |

| Tauopathies | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 6.0 (7) | 11.1 (9) | 7.5 (4) | 1.1 (20) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 9.0 (5) | 14.4 (5) | 6.2 (1) | 1.2 (11) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 3.3 (2) | 8.7 (4) | 8.1 (3) | 0.9 (9) |

| Progressive supernuclear palsy | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (5) | 8.7 (7) | 7.5 (4) | 0.9 (16) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 7.2 (4) | 14.4 (5) | 6.2 (1) | 1.1 (10) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.6 (1) | 4.3 (2) | 8.1 (3) | 0.6 (6) |

| Corticobasal syndrome | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.7 (2) | 2.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.2 (4) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.1 (1) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.6 (1) | 4.3 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.3 (3) |

| Other types of parkinsonism b | 0.1 (1) | 2.3 (13) | 5.0 (9) | 21.5 (25) | 44.5 (36) | 92.2 (49) | 7.2 (133) |

| Men | 0.2 (1) | 2.5 (7) | 3.5 (3) | 27.1 (15) | 57.6 (20) | 142.4 (23) | 7.8 (69) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 2.0 (6) | 6.4 (6) | 16.3 (10) | 34.7 (16) | 70.3 (26) | 6.6 (64) |

| Drug induced parkinsonism | 0.1 (1) | 1.0 (6) | 3.3 (6) | 6.0 (7) | 9.9 (8) | 15.1 (8) | 1.9 (36) |

| Men | 0.2 (1) | 1.1 (3) | 2.3 (2) | 1.8 (1) | 11.5 (4) | 12.4 (2) | 1.5 (13) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 (3) | 4.2 (4) | 9.8 (6) | 8.7 (4) | 16.2 (6) | 2.4 (23) |

| Vascular parkinsonism | 0.0 (0) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 3.4 (4) | 3.7 (3) | 5.6 (3) | 0.6 (11) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 0.4 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 5.4 (3) | 5.8 (2) | 12.4 (2) | 0.9 (8) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.6 (1) | 2.2 (1) | 2.7 (1) | 0.3 (3) |

| Parkinsonism unspecified | 0.0 (0) | 0.9 (5) | 1.7 (3) | 12.0 (14) | 29.7 (24) | 71.5 (38) | 4.5 (84) |

| Men | 0.0 (0) | 1.1 (3) | 1.2 (1) | 19.9 (11) | 37.5 (13) | 117.6 (19) | 5.3 (47) |

| Women | 0.0 (0) | 0.7 (2) | 2.1 (2) | 4.9 (3) | 23.8 (11) | 51.4 (19) | 3.8 (37) |

Incidence rates per 100,000 person-years. Numbers in parentheses to the right of the rates indicate the actual number of cases. Incidence rates can be computed by dividing the number in parentheses by the corresponding denominator and multiplying by 100,000. Denominators in person-years for men and women combined were as follows: 0–29 = 843,999; 30–49 = 577,614; 50–59 = 180,689; 60–69 = 116,489; 70–79 = 80,829; 80–99 = 53,142; all ages = 1,852,762. Denominators for men were as follows: 0–29 = 418,326; 30–49 = 277,387; 50–59 = 86,452; 60–69 = 55,288; 70–79 = 34,695; 80–99 = 16,155; all ages = 888,303. Denominators for women were as follows: 0–29 = 425,673; 30–49 = 300,227; 50–59 = 94,237; 60–69 = 61,201; 70–79 = 46,134; 80–99 = 36,987; all ages = 964,459.

This group included one patient with amyothropic lateral sclerosis in parkinsonism who carried a repeat expansion in the non-coding region of chromosome 9.24 In addition, this group included one patient with parkinsonism secondary to cingulotomy.

Figure 1.

Age- and sex-specific incidence rates for parkinsonism, Parkinson's disease, synucleinopathies, and tauopathies manifesting with parkinsonism (per 100,000 person-years). The scale for incidence was reduced in the graph for tauopathies (the y-axis values range from 0 to 25 per 100,000 person-years).

Synucleinopathies

The incidence rate of synucleinopathies was 21.0 (per 100,000 person-years) overall, was higher in men (27.0) than in women (15.4), and it increased steeply with age. We identified 264 patients with PD, 110 with parkinsonism with dementia, and 15 with MSA. PD was the most common type of synucleinopathy and was more frequent in men than in women (62.9% of PD cases were men). The incidence rate was higher in men than in women for all synucleinopathies (Figure 1).

Tauopathies

Presumed tauopathies manifesting as parkinsonism were uncommon, with a total of 20 patients (11 men, 9 women) and an overall incidence of 1.1 cases per 100,000 person-years. All patients with presumed tauopathies had onset of symptoms at age 60 years or older. The most common tauopathy was PSP, with incidence higher in men than in women (1.1 in men vs. 0.6 in women). CBS was more frequent in women (3 cases) than in men (1 case) and had an overall incidence of 0.2 per 100,000 person-years (0.1 in men and 0.3 in women; Figure 1).

Other Parkinsonism

We identified 36 patients with drug-induced parkinsonism, 11 with vascular parkinsonism, 1 with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in parkinsonism (the patient carried a repeat expansion in the non-coding region of chromosome 9),24 1 with parkinsonism secondary to cingulotomy, and 84 with unspecified parkinsonism. The overall incidence of other types of parkinsonism was higher in men than in women (7.8 in men vs. 6.6 in women). Unspecified parkinsonism and vascular parkinsonism were more common in men, whereas drug-induced parkinsonism was more common in women (Table 2).

Pathological Validation of Clinical Diagnoses

Of the 542 incident cases of parkinsonism, 343 (63.3%) had died through December 31, 2011, and 65 (19.0% of deceased patients) had a brain autopsy available for review (Table 3). The pathology observed at autopsy was consistent with the type of proteinopothy that was presumed clinically in 53 patients (81.5%). The concordance was 80.4% for synucleinopathies (45 cases out of 56 cases), 100% for tauopathies (2 cases with CBS), and 85.7% for other parkinsonisms (6 cases out of 7). Of the remaining 11 patients presumed to have a synucleinopathy at clinical diagnosis, 3 had tau pathology and 8 had nonspecific age-related changes (6 of these 8 cases had incontinence of substantia nigra without evidence of Lewy bodies or tau pathology). Of the 7 patients with other parkinsonisms, 1 had Lewy body pathology. None of the brains exhibited both Lewy body pathology and tau pathology.

TABLE 3.

Validation of clinical types of parkinsonism and presumed proteinopathies vs. neuropathological findings

| Neuropathological findings |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical classification | Lewy bodies No. | Tau No. | Othera No. | Total No. | Percent Agreement % |

| By type of parkinsonism | |||||

| Parkinson's disease | 17 | 1 | 2 | 20 | 85.0 |

| Parkinsonism with dementia | 24 | 1 | 6 | 31 | 77.4 |

| Multiple system atrophy | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 80.0 |

| Corticobasal syndrome | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Drug-induced parkinsonism | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 75.0 |

| Vascular parkinsonism | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 |

| Parkinsonism unspecified | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Total | 46 | 5 | 14 | 65 | 81.5 |

| By proteinopathy b | |||||

| Synucleinopathy | 45 | 3 | 8c | 56 | 80.4 |

| Tauopathy | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Other parkinsonism | 1 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 85.7 |

| Total | 46 | 5 | 14 | 65 | 81.5 |

Neuropathological findings listed as “other” include Alzheimer's disease pathologies.

Synucleinopathies include Parkinson's disease, parkinsonism with dementia, and multiple system atrophy. Tauopathies include corticobasal syndrome. Other parkinsonism includes drug-induced parkinsonism, vascular parkinsonism, and parkinsonism unspecified.

Six of these 8 cases had incontinence of substantia nigra without evidence of Lewy bodies or tau pathology.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that clinically-presumed synucleinopathies are the most common type of parkinsonism, and PD is the most common synucleinopathy. The second most common synucleinopathy is parkinsonism with dementia, followed by MSA. The incidence of all synucleinopathies increases steeply with age and is higher in men than women. The incidence of all tauopathies increases after age 60 years, and men have higher incidence than women, except for ages 80–99 years. PSP is the most common tauopathy followed by CBS. For a subsample of our patients, we were able to validate our clinical diagnosis at autopsy (65 incident cases; 12.0% of all cases and 19.0% of deceased cases).

There are several studies of the incidence of parkinsonism or PD but, to our knowledge, there are no population-based studies of the incidence of clinically-presumed proteinopathies.3, 4 Previous studies have found that PD is the most common type of parkinsonism.6, 22 Age and sex standardized incidence rates for PD have been reported in the range of approximately 10 to 18 cases per 100,000 person-years (rates adjusted to the 1990 US Census population).4 Onset of PD is uncommon before age 60 years, and the incidence of PD and other types of parkinsonism increases steeply after age 60 years.3, 4, 25

In our study, PD and most other types of parkinsonism were more common in men than in women. This pattern is consistent with a number of studies that showed a higher incidence of PD in men than women.4, 6, 26–30 In addition, some studies reported sex differences in clinical and preclinical characteristics and in risk factors for PD.27, 31, 32 Genetic, endocrinologic, environmental, or social and cultural differences may explain the differences in risk of PD between men and women.32–35

Findings from this investigation were consistent with results from a previous study in the same Olmsted County population.5, 6, 36–39 The overall age and sex adjusted incidence rate for PD was 16.5 in the current study and 14.2 in 1976 – 1990 (both rates adjusted to the 1990 US Census population). In addition, we found consistent patterns of incidence by age and sex.6 However, there were also small differences. For example, there were no cases of CBS in the 1976 – 1990 study, probably because CBS was not adequately recognized at the time.6

Our study has a number of strengths. First, taking advantage of the records-linkage system of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, we studied a large and well-defined population (1,852,762 person-years overall).10–12 Second, because our study included 542 incident cases of parkinsonism, we were able to explore the distribution of clinical subtypes of parkinsonism by age and sex. In addition, we were able to group incidence cases by presumed proteinopathy. Third, 63.3% of cases were followed from the onset of parkinsonism to the time of death, and 94.3% were followed through death or for at least five years after onset. This long follow-up provided information on the natural history of the disease and strengthened the classification by type of parkinsonism.

Fourth, all of the cases were adjudicated by a movement disorder specialist at the time of medical records abstraction to reduce differences in the diagnostic criteria over time or across the different care professionals (nurses, generalists, or specialists). Fifth, all of the medical facilities in Olmsted County, MN are included in the REP,10–12 and it is unlikely that a patient living in the county would have been seen for parkinsonism only at a medical facility outside of the system. In addition, the Olmsted County population is stable especially for subjects 65 years and older.11, 13 Finally, the agreement of autopsy findings with the clinical diagnosis of proteinopathy was high, suggesting that a clinical classification of patients with parkinsonism in synucleinopathies and tauopathies is valid.

Our study also has a number of limitations. First, it is possible that some of the persons with parkinsonism were unaware of their symptoms and had not received a diagnosis within the incidence period. However, our data collection spanned across 20 years, and we collected data for an additional five years after the incidence period (2006 – 2010). This allowed us to appropriately retro-date the time of onset of symptoms when needed. Second, the diagnoses obtained through review of historical medical records may be unreliable. The documents available in the records-linkage system were a combination of paper and electronic medical records from multiple care professionals and from multiple institutions. A majority of patients with parkinsonism had been seen by a neurologist at least once; however, the clinical findings were recorded as part of routine clinical practice and were not standardized for research (e.g., standard research scales for parkinsonism or for dementia were not used). Our small reliability study showed an agreement of 90.0% between the two neurologists for parkinsonism. However, the agreement by type of parkinsonism was less complete (74.1%). Third, because neurological practices and diagnostic criteria changed over time, some patients had more complete diagnostic information available in their records than others. In fact, the discordant diagnoses observed in our reliability study involved persons with multiple and atypical parkinsonian features. The classification of patients in a single clinical subtype involved clinical judgment (e.g., parkinsonism with concurrent use of neuroleptics, autonomic dysfunction, and cognitive disorders). The adjudication of all patients by a single movement disorder specialist should have attenuated these possible differences; however, 15.5% of the patients with parkinsonism remained unspecified.

Fourth, it is possible that the clinical diagnosis did not correspond with pathological findings in some cases. The agreement between clinically presumed proteinopathy and autopsy was 81.5% in our population-based sample. Clinicopathological concordance above 90% has previously been described when cases were selected using strict clinical criteria.40 On the other hand, a patient may have more than one pathological finding at autopsy;41, 42 thus, the clinical diagnosis of a single presumed proteinopathy may be incomplete. Interestingly, none of the brains exhibited both Lewy body pathology and tau pathology in our study. Fifth, we found only 20 patients with a presumed tauopathy manifesting with parkinsonism. Therefore, the results for tauopathy and its subtypes should be interpreted cautiously.

In conclusion, our study provides new data on the incidence of clinically-presumed proteinopathies related to parkinsonism in men and women. Synucleinopathies are the most common type of proteinopathies; among them, PD is the most common subtype, followed by parkinsonism with dementia, and MSA. Tauopathies manifesting with parkinsonism are rare disorders, and PSP is more common than CBS. The incidence of proteinopathies increases with age, and most types of proteinopathies are more frequent in men than women.

TABLE 1.

Diagnostic criteria for specific types of parkinsonism and for proteinopathies

Parkinsonism: a syndrome with any two of four cardinal signs

|

| Synucleinopathies 7, 8 |

Parkinson's disease: parkinsonism with all three of

|

| Parkinsonism with dementia: parkinsonism with evidence of dementia before or after the onset of parkinsonian symptoms. We combined the two conditions of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) defined by the McKeith consensus guidelines.18 |

Multiple system atrophy: parkinsonism with one of

|

| Tauopathies 9 |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy: criteria by Collins et al.16 |

| Corticobasal syndrome: Criteria by Maraganore et al.19, 20 |

| Other types of parkinsonism |

Drug-induced parkinsonism: parkinsonism with all three of

|

Vascular parkinsonism: Parkinsonism with all three of

|

| Secondary parkinsonism: parkinsonism secondary to brain tumor, surgical procedures, post-encephalitis. |

| Parkinsonism unspecified: parkinsonism with insufficient clinical documentation or not meeting any of the other criteria. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding/Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AG034676 and by the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding organizations had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and in the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: R. Savica designed the study, abstracted all medical records, applied the diagnostic criteria, and drafted the manuscript. B. Grossardt assisted with the design of the study, performed the statistical analyses, and reviewed the manuscript. J. Bower and J.E. Ahlskog provided movement disorders expertise in the diagnosis and classification of study subjects, participated in the diagnostic reliability study, and reviewed the manuscript. W. Rocca assisted with the design of the study, contributed to the analyses and to the interpretation of findings, and reviewed the manuscript. W. Rocca has had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach JP, Ziegler U, Deuschl G, Dodel R, Doblhammer-Reiter G. Projected numbers of people with movement disorders in the years 2030 and 2050. Mov Disord. 2011 Oct;26(12):2286–2290. doi: 10.1002/mds.23878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twelves D, Perkins KS, Counsell C. Systematic review of incidence studies of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2003 Jan;18(1):19–31. doi: 10.1002/mds.10305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006 Jun;5(6):525–535. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Den Eeden SK, Tanner CM, Bernstein AL, et al. Incidence of Parkinson's disease: variation by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Jun 1;157(11):1015–1022. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Incidence of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976 to 1990. Neurology. 1997 Nov;49(5):1284–1288. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.5.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Incidence and distribution of parkinsonism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–1990. Neurology. 1999 Apr 12;52(6):1214–1220. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.6.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HJ, Patel S, Lee SJ. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates. J Neurosci. 2005 Jun 22;25(25):6016–6024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0692-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jellinger KA. Formation and development of Lewy pathology: a critical update. J Neurol. 2009 Aug;256(Suppl 3):270–279. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DR. Tauopathies: classification and clinical update on neurodegenerative diseases associated with microtubule-associated protein tau. Intern Med J. 2006 Oct;36(10):652–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of Epidemiologic Findings and Public Health Decisions: An Illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 May 1;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St. Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: Half a Century of Medical Records Linkage in a US Population. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. Data Resource Profile: The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;18:18. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Commission on Professional and Hospital Activities. National Center for Health Statistics . H-ICDA, Hospital Adaptation of ICDA. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor, MI: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . Manual of the international classification of diseases, injuries, and causes of death, based on the recommendations of the ninth revision conference, 1975, and adopted by the twenty-ninth World Health Assemby. Geneva: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins SJ, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, Maraganore DM. Progressive supranuclear palsy: neuropathologically based diagnostic clinical criteria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995 Feb;58(2):167–173. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.2.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilman S, Low P, Quinn N, et al. Consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. American Autonomic Society and American Academy of Neurology. Clin Auton Res. 1998 Dec;8(6):359–362. doi: 10.1007/BF02309628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKeith IG. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9(3 Suppl):417–423. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boeve BF. Corticobasal Degeneration: The Syndrom and the Disease. In: Litvan I, editor. Current Clinical Neurology: Atypical Pakinsonian Disorders. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 2005. pp. 309–333. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maraganore DM, Ahlskog JE, Peterson RT. Progressive asymmetric regidity with apraxia: a distinct clinical entity [abstract] Mov Disord. 1992;7:80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Rijk MC, Tzourio C, Breteler MM, et al. Prevalence of parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease in Europe: the EUROPARKINSON Collaborative Study. European Community Concerted Action on the Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997 Jan;62(1):10–15. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson DW, Mantel N. On epidemiologic surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 1983 Nov;118(5):613–619. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boeve BF, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, et al. Characterization of frontotemporal dementia and/or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with the GGGGCC repeat expansion in C9ORF72. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2012 Mar;135(Pt 3):765–783. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayeux R, Marder K, Cote LJ, et al. The frequency of idiopathic Parkinson's disease by age, ethnic group, and sex in northern Manhattan, 1988–1993. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Oct 15;142(8):820–827. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haaxma CA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, et al. Gender differences in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Aug 1;78(8):819–824. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.103788. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajput AH, Offord KP, Beard CM, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of parkinsonism: incidence, classification, and mortality. Ann Neurol. 1984 Sep;16(3):278–282. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldereschi M, Di Carlo A, Rocca WA, et al. Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism in a longitudinal study: two-fold higher incidence in men. ILSA Working Group. Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neurology. 2000 Nov 14;55(9):1358–1363. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.9.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wooten GF, Currie LJ, Bovbjerg VE, Lee JK, Patrie J. Are men at greater risk for Parkinson's disease than women? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004 Apr;75(4):637–639. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.020982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor KSM, Cook JA, Counsell CE. Heterogeneity in male to female risk for Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007 Aug 1;78(8):905–906. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104695. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott B, Borgman A, Engler H, Johnels B, Aquilonius SM. Gender differences in Parkinson's disease symptom profile. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102(1):37–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.102001037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Risk factors for Parkinson's disease may differ in men and women: an exploratory study. Horm Behav. 2012 Jun 8; doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.05.013. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saunders-Pullman R, Stanley K, San Luciano M, et al. Gender differences in the risk of familial parkinsonism: beyond LRRK2? Neurosci Lett. 2011 Jun 1;496(2):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung SJ, Armasu SM, Biernacka JM, et al. Variants in estrogen-related genes and risk of Parkinson's disease. Movement disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2011 Jun;26(7):1234–1242. doi: 10.1002/mds.23604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frigerio R, Sanft KR, Grossardt BR, et al. Chemical exposures and Parkinson's disease: a population-based case-control study. Mov Disord. 2006;21(10):1688–1692. doi: 10.1002/mds.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Rocca WA. Influence of strict, intermediate, and broad diagnostic criteria on the age- and sex-specific incidence of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2000 Sep;15(5):819–825. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<819::aid-mds1009>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rocca WA, Bower JH, McDonnell SK, Peterson BJ, Maraganore DM. Time trends in the incidence of parkinsonism in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology. 2001 Aug 14;57(3):462–467. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elbaz A, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Risk tables for parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002 Jan;55(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bower JH, Dickson DW, Taylor L, Maraganore DM, Rocca WA. Clinical correlates of the pathology underlying parkinsonism: a population perspective. Mov Disord. 2002 Sep;17(5):910–916. doi: 10.1002/mds.10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Blankson S, Lees AJ. A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases of Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 1993 Feb;50(2):140–148. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540020018011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fotuhi M, Hachinski V, Whitehouse PJ. Changing perspectives regarding late-life dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009 Dec;5(12):649–658. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oinas M, Sulkava R, Polvikoski T, Kalimo H, Paetau A. Reappraisal of a consecutive autopsy series of patients with primary degenerative dementia: Lewy-related pathology. APMIS. 2007 Jul;115(7):820–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]