If a movie star trips over a poodle outside a sushi bar in Los Angeles in front of camera-ready paparazzi, school girls in Japan would, within minutes, undoubtedly find links to photos of the mishap as they thumb through the Twitter feed on their iPhones. Yet in an age where information moves almost at the speed of thought, an important health warning on a drug in Europe took years to reach labels on the same product in Canada.

And many people in Canada who took that drug aren’t too happy about the delay.

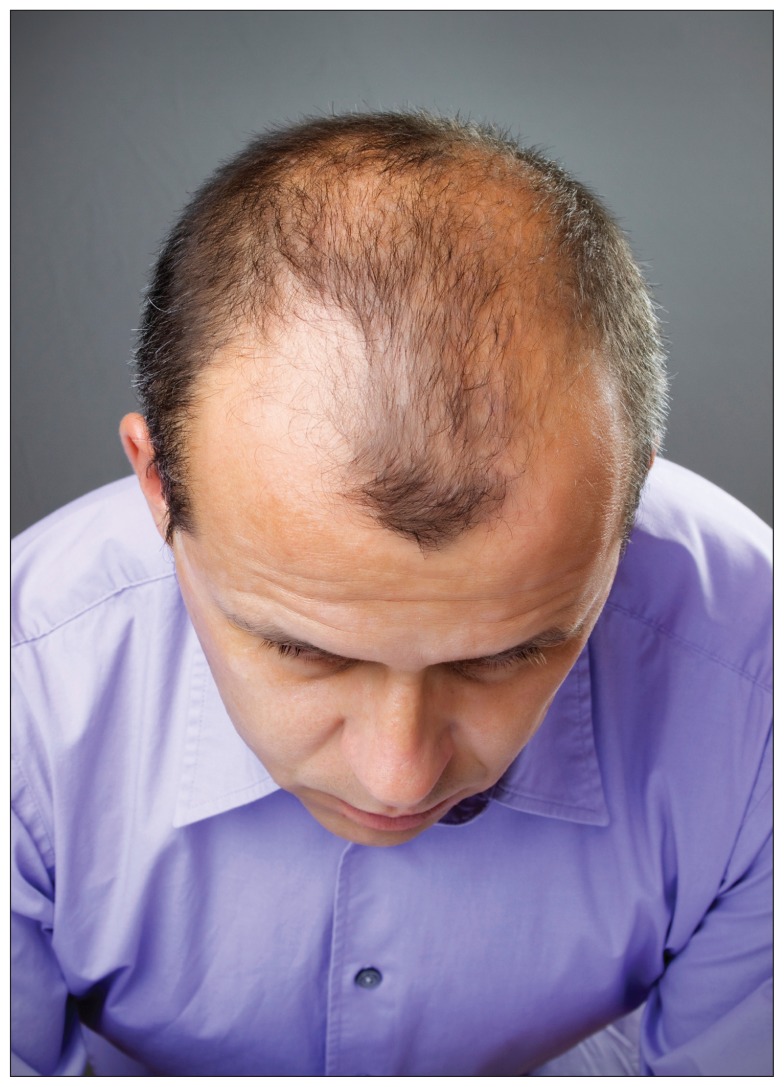

Finasteride is the active ingredient in Propecia, a hair-loss drug, and in Proscar, which is used to treat prostate enlargement but also promotes hair growth. The drug company Merck makes both products.

In 2008, Sweden updated the monographs on these drugs to warn of persistent sexual dysfunction even after men stopped taking them. Italy soon followed suit, as did the United Kingdom. Though labels in Canada warned of possible sexual dysfunction, they were not updated to include the bit about how it could continue “after discontinuation of treatment” until 2011.

“A three-year delay? That’s pretty bad. That’s really pretty bad,” says David Klein, a lawyer in Vancouver, British Columbia. “When you have a three- or four-year time lag between warnings in Europe and warnings in Canada, that’s a serious public health issue.”

Hundreds of men in Canada with lasting sexual dysfunction believe that Merck should have warned them earlier. Klein’s law firm, Klein Lyons, has launched class-action lawsuits against the drug company on their behalf in BC, Ontario and Quebec. “They keep calling us,” says Klein. “These are, for the most part, young men who had no sexual problems before they went on the drug.”

Men involved in class-action lawsuits against Merck claim to have erectile dysfunction that continued after they stopped taking the hair-loss drug Propecia, but the drug company attributes these problems to pre-existing conditions and other risk factors.

Image courtesy of © 2013 Thinkstock

According to Merck, however, the available data do not support claims of a causal link between Propecia or Proscar and persistent erectile dysfunction that continues after going off either drug.

“In these cases, Merck believes that the evidence will show that the company acted responsibly and appropriately with respect to Propecia and Proscar throughout the development, marketing and post-marketing monitoring of these medicines,” Merck says in a statement sent to CMAJ from Lainie Keller, the company’s director of global communications.

“Merck also believes that the evidence will show that pre-existing conditions and other risk factors, not Propecia or Proscar, caused the claimed conditions.”

And according to Health Canada, the agency responsible for pharmaceutical monographs, delays in updating drug warning labels are to be expected because it conducts an independent review when new safety issues arise in other countries.

“This analysis takes into account a variety of domestic factors, such as the pattern of use of the drug in Canada, availability in Canada, Canadian prescribing practices and Canadian treatment guidelines,” Health Canada states in an email sent to CMAJ from media relations officer Leslie Meerburg.

“When Health Canada’s assessment of all available data identifies a new health risk with a product, Health Canada takes appropriate action, such as working with the manufacturer to update the product labelling and notifying health professionals and consumers of this change.”

Despite updated warning labels and notifications, there still appears to be many doctors prescribing these drugs to patients without adequately informing them of the risks, says Dr. Michael Irwig, an assistant professor of medicine at George Washington University in Washington, DC. Irwig has written several papers exploring the adverse medical effects of finasteride, including one that showed 61 former users who developed persistent sexual side effects had higher rates of depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts than 29 men in a control group (J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:1220–3).

“If you want to use this medication for your hair, you may grow a little hair, but there are cases of men who have persistent sexual side effects that last a decade after stopping this medication,” says Irwig. “This is some very serious stuff.”