Abstract

Background

Cognitive rehabilitation has emerged as an effective treatment for addressing cognitive impairments and functional disability in schizophrenia; however, the degree to which changes in various social and non-social cognitive processes translate into improved functioning during treatment remains unclear. This research sought to identify the neurocognitive and social-cognitive mechanisms of functional improvement during a two-year trial of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET) for early course schizophrenia.

Method

Patients in the early course of schizophrenia were randomly assigned to CET (n = 31) or an Enriched Supportive Therapy control (n = 27) and treated for up to two years. A comprehensive neurocognitive assessment battery and the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) were completed annually, along with measures of functioning. Mediator analyses using mixed-effects growth models were conducted to examine the effects of neurocognitive and social-cognitive improvement on functional change.

Results

Two-year improvement in neurocognition and the emotion management branch of the MSCEIT were found to be significantly related to improved functional outcome in early course schizophrenia patients. Neurocognitive improvement, primarily in executive functioning, and social-cognitive change in emotion management also mediated the robust effects of CET on functioning.

Conclusions

Improvements in neurocognition and social cognition that result from cognitive rehabilitation are both significant mediators of functional improvement in early course schizophrenia. Cognitive rehabilitation programs for schizophrenia may need to target deficits in both social and non-social cognition to achieve an optimal functional response.

Schizophrenia is an often chronic mental disorder that is characterized by significant impairments in cognition and functioning. Marked deficits have been observed in social and non-social cognitive domains (Heinrichs & Zakzanis, 1998; Penn, Corrigan, Bentall, Racenstein, & Newman, 1997), which cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have found to be significant and consistent predictors of functional outcome (Couture, Penn, & Roberts, 2006; Green, Kern, Braff, & Mintz, 2000). Such findings have fueled arguments for the treatment of cognitive impairments in schizophrenia as a key mechanism for improving functioning in the disorder (Green & Nuechterlein, 1999; Hogarty & Flesher, 1992).

While the pharmacologic treatment of cognitive impairments in schizophrenia has produced limited improvements (Keefe et al., 2007; Sergi et al., 2007), a number of psychosocial cognitive rehabilitation approaches have emerged as effective methods for addressing cognitive deficits in the disorder (McGurk, Twamley, Sitzer, McHugo, & Mueser, 2007). One integrated approach to the remediation of social and non-social cognitive impairments in schizophrenia that has been shown to be particularly effective at improving cognition and functioning in the disorder is Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET; Hogarty & Greenwald, 2006). In the initial CET study with chronically ill patients, we demonstrated that CET resulted in marked improvements in processing speed, neurocognition, and social cognition, as well as social adjustment (Hogarty et al., 2004). A one-year follow-up study also showed that these improvements could be maintained after the completion of treatment (Hogarty, Greenwald, & Eack, 2006). Recently, we tested the effects of CET as an early intervention approach with 58 early course schizophrenia outpatients, and again found substantial improvements in neurocognition (d = .46) and social cognition (d = 1.55), but not processing speed, which was relatively preserved among early course patients. In addition, large (d = 1.53) and broad functional improvements were observed in vocational functioning, activities of daily living, and other domains of social adjustment (Eack et al., 2009; Eack et al., in press).

The effects of CET and other cognitive rehabilitation approaches on functional outcome strongly support the treatment of cognition as a critical mechanism for functional improvement in schizophrenia. Unfortunately, few studies have explicitly tested the degree to which improvements in cognition contribute to functional improvement. In the initial CET study with chronically ill patients, we found that improvements in processing speed served as a significant partial mediator of CET effects on social adjustment (Hogarty, Greenwald, & Eack, 2006). Wykes and colleagues studied Cognitive Remediation Therapy among early-onset patients and found that improvements in executive functioning, working memory, and planning were related to improved social behavior (Wykes et al., 2007); however, previous studies of that intervention with chronic patients did not demonstrate a link between changes in neurocognitive domains and functioning (Reeder et al., 2004; Reeder et al., 2006). To date, no studies have examined the effect of both improved neurocognition and social cognition on functional outcome during cognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia.

Having recently found substantial functional benefits of CET in early schizophrenia during a two year randomized trial (Eack et al., 2009), we now examine the degree to which social-cognitive and neurocognitive enhancement during this trial served as active mechanisms of functional improvement in these early course patients. It was hypothesized that both improved neurocognition and social cognition would contribute to improvements in functioning, and mediate the differential effects of CET on functional outcome. Unlike our initial CET study (Hogarty, Greenwald, & Eack, 2006), the mediational effects of improved processing speed were not investigated, as this sample of early course patients demonstrated relatively preserved performance in processing speed that did not change with treatment (Eack et al., 2009).

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 58 early course outpatients with schizophrenia (n = 38) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 20), as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), treated in a two-year trial of CET. The early course of schizophrenia was defined for this research as no greater than eight years since the first emergence of psychotic symptomatology. Eligible participants included individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or schizophreniform disorder stabilized on antipsychotic medications who experienced their first psychotic symptom within the past 8 years, were not abusing substances for at least 2 months prior to study enrollment, had an IQ > 80, and exhibited significant social and cognitive disability on the Cognitive Style and Social Cognition Eligibility Interview (Hogarty et al., 2004). The Cognitive Style and Social Cognition Eligibility Interview is a structured interview measure that was used to ensure enrolled patients experienced significant cognitive and functional disability warranting treatment. Demographic and clinical characteristics of CET and EST patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Treated with Cognitive Enhancement Therapy or Enriched Supportive Therapy.

| Variable | CET (N = 31)

|

EST (N = 27)

|

pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 25.88 (6.46) | 25.97 (6.26) | .955 |

| Male (N/%) | 20 (65%) | 20 (74%) | .617 |

| Caucasian (N/%) | 21 (68%) | 19 (70%) | .662 |

| Attended College (N/%) | 9 (29%) | 10 (37%) | .713 |

| Not Employed (N/%) | 8 (26%) | 7 (26%) | .772 |

| Schizophrenia (N/%) | 21 (68%) | 17 (63%) | .916 |

| Years Since First Psychotic Symptom | 3.07 (2.34) | 3.32 (2.16) | .675 |

| IQ | 97.74 (7.66) | 98.52 (9.74) | .736 |

| Symptoms | |||

| BPRS Total | 39.77 (9.21) | 40.70 (10.64) | .723 |

| Wing Negative Symptoms Scale | 18.35 (4.14) | 18.15 (3.63) | .842 |

| Raskin Depression Scale | 6.77 (2.77) | 6.33 (1.98) | .494 |

| Covi Anxiety Scale | 5.84 (2.08) | 6.11 (2.22) | .632 |

| Medications | |||

| Dose (baseline, cpz) | 405.38 (339.95) | 460.68 (335.05) | .536 |

| Dose (year 1, cpz) | 402.33 (332.93) | 529.38 (374.13) | .215 |

| Dose (year 2, cpz) | 473.58 (384.43) | 548.71 (402.05) | .520 |

Note. CET = Cognitive Enhancement Therapy, BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, EST = Enriched Supportive Therapy.

χ2 test or independent t-test, two-tailed, for significant differences between CET and EST participants.

Treatments

Participants were treated with either CET or an Enriched Supportive Therapy (EST) control, both of which have been described in detail elsewhere (Hogarty et al., 2004; Eack et al., 2009). Briefly, CET is a comprehensive cognitive rehabilitation intervention designed to address the social and non-social cognitive deficits that limit functional recovery from schizophrenia. Patients treated with CET complete approximately 60 hours of computer-based training in attention, memory, and problem-solving and 45 small group social-cognitive therapy sessions designed to enhance perspective-taking, social context appraisal, foresightfulness, and getting the “gist” out of social situations. EST is an illness management and education approach based on Personal Therapy (Hogarty, 2002), which provides patients with psychoeducation about schizophrenia and teaches applied coping strategies to reduce stress. EST is tailored to the patient’s level of recovery, and begins with weekly 30–60 minute individual therapy sessions. As patients progress through the treatment, increasingly complex coping strategies are taught and applied, and therapy sessions are provided on a biweekly basis. All participants were maintained on antipsychotic medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Measures

Neurocognition

A comprehensive battery of paper-and-pencil and computerized neuropsychological tests representing the domains of verbal and working memory, executive functioning, language ability, psychomotor speed, and neurological soft signs was used to assess the neurocognitive mechanisms of CET effects on functional outcome. These domains assessed reflect the prominent areas of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, and are largely consistent with those outlined by the MATRICS committee (Green et al., 2004). Items from tests of these domains were combined into an overall composite measure of neurocognitive function, and included immediate and delayed recall items from stories A and B of the Revised Wechsler Memory Scale (Wechsler, 1987); List A total recall, short-term free recall, and long-term free recall from the California Verbal Learning Test (Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Ober, 1987); digit span, digit symbol, picture arrangement, and vocabulary items from the Revised Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 1981); Trails B time to completion (Reitan & Waltson, 1985); perseverative and non-perseverative errors, categories completed, and percentage of conceptual responses from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay, & Curtiss, 1993); total move score and ratio of initiation to execution (planning) time from the Tower of London (Culbertson & Zillmer, 1996); and cognitive-perceptual and repetition-motor subscales from the Neurological Evaluation Scale (Buchanan & Heinrichs, 1989). Items were scaled to a common metric and then averaged to form an overall neurocognitive composite. The reliability of this composite was good (Cronbach’s α = .87).

Social cognition

Social cognition was assessed using the MATRICS-recommended Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, 2003). The MSCEIT is a performance-based measure of emotional intelligence that requires participants to solve emotionally-laden problems regarding the perception, facilitation, understanding, and management of emotion. In keeping with the developers’ administration guidelines, patients completed the MSCEIT as a computerized, self-administered test in this research. The instrument consists of 141-items across 8 distinct tasks form the emotion perception, facilitation, understanding, and management branches of Salovey & Mayer’s (1990) proposed 4-branch model of emotional intelligence. Although the MATRICS committee only recommended the use of the emotion management branch of the MSCEIT, all four branches were used in this research. We have previously shown the MSCEIT to be a reliable measure of social cognition that is unique from both neurocognitive function and symptomatology (Eack et al., 2010), and the MATRICS initiative has demonstrated the test-retest reliability of the emotion management branch of the instrument to be adequate (Nuechterlein et al., 2008). Behavioral ratings of social cognition previously reported on were not considered for mediator analyses, due to their completion by the same raters who assessed functional outcome and were not blind to treatment assignment.

Functional outcome

Functional outcome was assessed largely using field standards of social adjustment and functioning in schizophrenia. Measures included the Social Adjustment Scale-II (Schooler, Weissman, & Hogarty, 1979), Global Assessment Scale (Endicott et al., 1976), Major Role Inventory (Hogarty et al., 1974), and Performance Potential Inventory (Hogarty et al., 2004; Department of Health and Human Services, 1986). These measures have been described in greater detail in previous reports (Eack et al., 2009), and together they cover the broad domains of social, vocational, family, sexual, independent living, and leisure functioning. An overall composite index of functional outcome was used to avoid excessive inference testing among the large number of items cleaned from these instruments. This composite was calculated by scaling individual functional outcome items to a common metric and then averaging them to form the functional outcome composite, which displayed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .87).

Procedures

Participants were recruited from outpatient services at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh, and nearby community clinics. Patients who met eligibility requirements were randomly assigned to CET or EST and treated for a full two years in their respective treatment condition. Cognitive and functional assessments were performed prior to treatment and then annually at 12 and 24 months for two years using the aforementioned measures by study clinicians or trained neuropsychologists, who were not blind to treatment assignment. However, assessors administering the performance-based neurocognitive and MSCEIT tests were blind to clinical assessments of functional outcome. There were no significant differences between treatment groups with regard to demographic and symptom characteristics at baseline, attrition, or medication characteristics (Eack et al., 2009). Of the 58 patients randomized and treated, 49 and 46 completed 1 and 2 years of treatment, respectively. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation, and the study was reviewed annually by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Mechanisms of functional improvement during CET were analyzed using path analysis based on the mediator-analytic framework for clinical trials outlined by Kraemer and colleagues (2002). This framework is based on seminal work by Baron and Kenny (1986), where a series of linear models are used to evaluate the impact of treatment assignment or choice (CET vs. EST) on an outcome (improved functional outcome) through an intermediate treatment response or putative mediator (improved cognition). In a clinical trial, treatment assignment or choice has k levels corresponding to the number of treatment groups in the trial (in this case 2 levels, CET or EST). In order to demonstrate that improved cognition is a mediator between treatment assignment and improved functional outcome outcome, several conditions must be met.

First, treatment assignment must be associated with outcome response, that is assignment to CET vs. EST must have a direct impact on changes in functional outcome (Criterion A). This condition is otherwise known as a main effect of treatment on outcome, and establishes that the type of treatment provided (e.g., CET vs. EST) is associated with different changes in outcome (e.g., individuals in CET improve more on functional outcome than those in EST). Second, treatment assignment must be associated with response to an intermediate outcome or mediator, that is assignment to CET vs. EST must have a direct impact on changes in cognition (Criterion B). This condition establishes that the type of treatment provided is also associated with a differential response on the putative mediator (e.g., individuals in CET improve more on cognition than those in EST). Third, changes in the mediator must be associated with changes in the outcome, or changes in cognition must have a direct impact on changes in functional outcome (Criterion C). This condition demonstrates the interrelationship between improvement on the mediator and improved outcome. Linear models used to assess this relationship across treatment groups first adjust for treatment assignment to remove the possibility of an illusory association between the mediator and outcome, simply because of their shared relationship with treatment assignment (which is given from Criteria A–B). Finally, the direct effect of treatment assignment on changes in outcome must be reduced, after accounting for the association between changes in the mediator and changes in the outcome. That is, the relationship between assignment to CET vs. EST and changes in functional outcome will be reduced (i.e., partially explained by the mediator) or eliminated (i.e., entirely explained by the mediator) after adjusting for the association between changes in cognition and changes in functional outcome (Criterion D). When Criterion D is met, the direct effect of treatment assignment on changes in outcome is reduced because the total effect of treatment is partitioned into its direct and indirect (through the mediator) components.

Within the context of this research, these principles of mediation were applied to examine whether treatment assignment to CET (versus EST) resulted in improved functional outcome, and whether this differential functional improvement was mediated by the beneficial effect of treatment assignment to CET on neurocognition and social cognition. To accomplish this, a series of path analyses employing linear mixed-effects growth models was used to show that, consistent with previous reports from this trial (Eack et al., 2009; Eack et al., 2007), treatment assignment to CET resulted in greater improvement in functional outcome (Criterion A) and the putative mediators, neurocognition and social cognition (Criterion B), compared to EST. Next, mixed-effects models examined the association between changes in neurocognition and social cognition, and changes in functional outcome (Criterion C), by predicting functional outcome from the neurocognition composite and MSCEIT branch scores over the course of the study (i.e., time-varying covariates) after adjusting for treatment assignment (Singer & Willet, 2003). Finally, the adjusted direct effect of CET on functional outcome after controlling for cognitive change was obtained from these models, as well as the indirect effect of treatment assignment to CET on functional outcome through improved cognition (Criterion D).

It is important to note that both treatment groups (CET and EST) are included in all of these models, as CET-specific effects or the true effect of CET on both cognition and functional outcome can only be estimated in contrast to a control condition. This is one of the core principles of experimental designs and randomized clinical trials (Campbell & Stanley, 1963), where improvement within the CET group alone could be a function of many different factors other than the specific elements of the treatment (e.g., repeated testing effects, the provision of skilled clinicians, the use of supportive therapy). The use of a randomized control condition is designed to control for these factors, and EST in particular is designed to control for the non-specific effects of supportive treatment. As such, only improvements in CET that exceed those of patients treated with EST can be considered true, CET-specific treatment effects, and it is these CET-specific effects that are the subject of mediator analyses. In fact, because of this property of randomized-controlled trials, the examination of mediators in the context of clinical trials is particularly advantageous, as the source of differential change in both the outcome and mediator is known and inferences regarding causality are considerably strengthened (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002).

All mixed-effects models employed intent-to-treat analyses with all 58 patients who received any exposure to their respective treatment condition. Missing data was handled using the expectation-maximization approach (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977). In addition, all models adjusted for the potential confounding effects of age, sex, illness duration, and IQ at baseline, as well as current medication dose. Only confounders that demonstrated a significant effect on outcome change were retained to conserve power. Model coefficients are presented using z-scale transformations to ease interpretation and coefficient comparisons, and all models made use of intent-to-treat analyses with all 58 individuals who were randomized and received any of the study treatments. The size and significance of mediation effects was estimated using MacKinnon and colleagues’ (2002) asymptotic z′ test of indirect effects.

Results

Mediating Effects of Neurocognitive and Social-Cognitive Improvement on Functional Change

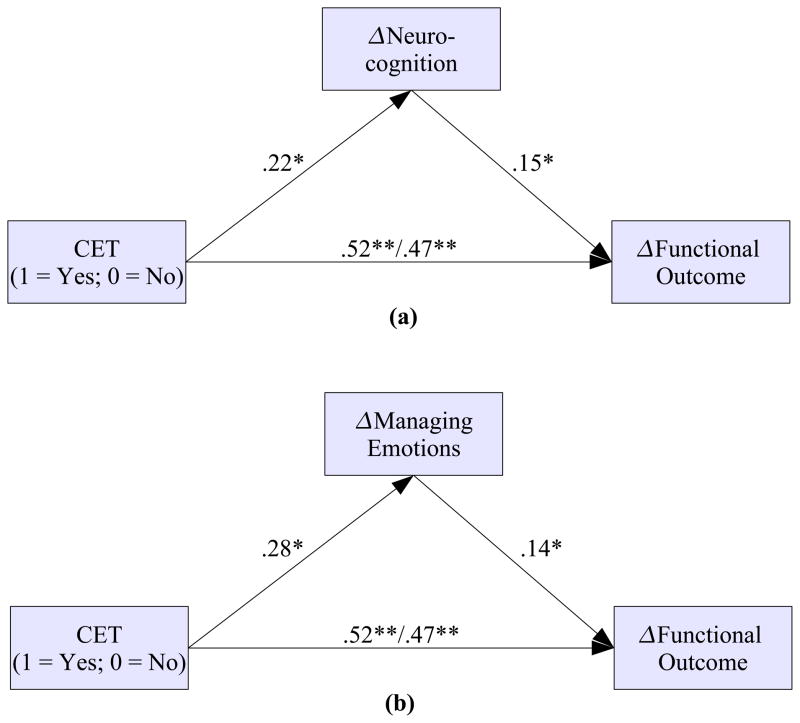

Neurocognitive and social-cognitive correlates and mediators of functional improvement among early course patients participating in a two-year trial of CET are presented in Table 2. Neurocognitive composite improvement was significantly related to improvements in functional outcome, with patients who experienced larger neurocognitive gains during the course of the trial experiencing a greater functional response. With regard to social cognition, of the four branches of the MSCEIT that were examined, only the emotion management branch demonstrated a significant longitudinal relationship with functional change. Figure 1 presents the results of path models examining the mediating effect of overall neurocognitive and emotion management improvement on functional outcome. As shown in Figure 1a, CET exerted a significant effect on the neurocognitive composite, which in turn was directly related to improved function. This cascade of neurocognitive change proved to significantly mediate the robust direct effects of CET on functional outcome, z′ = 1.50, N = 58, p = .047. A similar pattern of results was observed for the MSCEIT emotion management branch, where CET had its largest effects, which again was related to functional improvement and significantly mediated the effects of CET on functioning, z′ = 1.56, N = 58, p = .039 (see Figure 1b). When examining the relative impact of neurocognitive and social-cognitive improvement on functional outcome concurrently, improved emotion management continued to demonstrate a significant direct effect on functional improvement (B = .14, df = 86, p = .045), whereas the effect of neurocognitive change on functioning was only marginal, but of similar magnitude (B = .13, df = 86, p = .072). Interestingly, overall changes in neurocognition were not associated with improvements in the MSCEIT Managing Emotions subscale (B = .06, df = 87, p = .445), although improved neurocognition was significantly associated with improvements in the MSCEIT Facilitating Emotions subscale (B = .20, df = 87, p = .006). Together, these findings indicate largely independent improvements in both neurocognition and social cognition, particularly emotion management, as mechanisms of functional change during CET in early course schizophrenia.

Table 2.

Associations Between Changes in Neurocognition and Social Cognition and Improved Functional Outcome (N = 58).

| Variable | ΔFunctional Outcome

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effecta | Mediator Effectb | |||||

|

| ||||||

| B | SE | t | df | p | z′ | |

| ΔNeurocognition Composite | .15 | .07 | 2.07 | 89 | .041 | 1.50* |

| ΔSocial Cognition (MSCEIT) | ||||||

| ΔPerceiving emotions | −.07 | .07 | −1.07 | 87 | .288 | −.98 |

| ΔFacilitating emotions | −.05 | .06 | −.79 | 87 | .434 | −.63 |

| ΔUnderstanding emotions | −.00 | .07 | −.01 | 87 | .989 | −.01 |

| ΔManaging emotions | .14 | .07 | 2.10 | 87 | .038 | 1.56* |

Note. Results are based on mixed-effects regression models with a single social cognition variable as the primary covariate, adjusting for age, gender, IQ, illness duration, medication dose, and treatment assignment.

MSCEIT = Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test

Direct effects represent direct relations between changes in cognition and changes in functional outcome

Mediator effects represent the intervening effect of changes in cognition on CET effects on functional outcome

p < .05

Figure 1.

Neurocognitive and Social-Cognitive Mediators of the Effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy on Functional Outcome in Early Course Schizophrenia (N = 58). Note. Regression weights on the left and right of the slash (/) represent direct and indirect effects, respectively.

*p < .05, **p < .01

Mediating Effects of Improvement in Individual Neurocognitive Tasks on Functional Change

Having found evidence for improvements in overall neurocognitive ability as a significant mediator of CET effects on functioning at the composite level, we proceeded to conduct a series of exploratory analyses to examine the degree to which individual neurocognitive tests contributed to this effect. Results revealed that improved delayed recall on the Wechsler Memory Scale (B = .13, df = 82, p = .032) and long-term free recall on the California Verbal Learning Test (B = .12, df = 87, p = .037) were significantly related to greater functional improvement, and reduced time to complete Trails B (B = −.16, df = 87, p = .011) and perseverative (B = −.12, df = 88, p = .016) and non-perseverative (B = −.10, df = 87, p = .031) errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test were also associated with greater functional gains. Despite several direct relations between changes in verbal memory, executive function domains, and improved functional outcome, decreases in Trails B time to completion proved to be the only significant neurocognitive mediator of CET effects on functioning, z′ = 1.60, N = 58, p = .038. Such results suggest the importance of verbal memory and executive functioning improvement to functional outcome in early course schizophrenia, and point to improved executive performance as a key neurocognitive mediator of CET effects on functioning.

Discussion

Cognition has emerged as a key target of schizophrenia treatment, and a variety of psychosocial cognitive rehabilitation programs have been developed and shown to be effective at improving both cognition and functional outcome in the disorder (McGurk et al., 2007). Unfortunately, the mechanisms of functional improvement that accrue from these interventions remain largely unknown, and thus the degree to which targeting cognition results in meaningful gains in functioning is not clear. We conducted a first investigation of the neurocognitive and social-cognitive mechanisms of functional improvement during a two-year trial of CET for patients in the early course of schizophrenia. Overall, improvement in neurocognitive composite scores were significantly associated with improved functioning, which partially mediated the effect of CET on functional outcome. Of the four branches of the MSCEIT that were examined, only the MATRICS-recommended emotion management branch proved to be a significant mediator of CET effects on functioning. Exploratory analyses of individual neurocognitive tests also revealed significant relations between verbal memory, executive function, and functional improvement, with decreased Trails B time to completion exerting a significant mediating effect on functioning. Such findings signify both neurocognitive and social-cognitive improvement, particularly in the domains of executive performance and emotion management, as mechanisms of functional improvement during cognitive rehabilitation in early schizophrenia.

The results of this investigation support previous cross-sectional and naturalistic longitudinal studies documenting the importance of both neurocognition and social cognition to functional outcome in schizophrenia (Brekke et al., 2007; Brekke et al., in press; Sergi et al., 2006). Consistent with previous studies (Green, Kern, Braff, & Mintz, 2000), verbal memory improvements were the most reliable neurocognitive predictors of functional change in this research, and may represent an important neurocognitive precursor for benefiting most from treatment strategies used in CET, such as active thinking, giving feedback, responding to coaching, and abstracting the social gist. Improvements in social cognition also proved to be important contributors to functional outcome and mediated CET effects on functioning. Unfortunately, despite growing evidence on the importance of social cognition to functional outcome (Couture, Penn, & Roberts, 2006), the majority of cognitive rehabilitation approaches do not address social-cognitive impairments.

Although the results of this research begin to provide some evidence of a mediational relationship between changes in neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcome within the context of a clinical trial, it is important to remember that not all mediators are causal mechanisms (Kraemer et al., 2002). In addition, correlational analyses of change cannot disambiguate the direction of mediational relations, and it is possible that a bidirectional relationship exists between improved cognition and functioning. The clear identification of causality and directionality with regard to a mediator requires a priori studies designed to manipulate the presence or absence of a putative mechanism. This research lays the foundation for such studies, by identifying a need for controlled trials that examine the functional effects of treating neurocognition and social cognition either alone or jointly. Further, both social-cognitive and neurocognitive improvement were only partial mediators of functional improvement, which indicates the presence of other active mechanisms of functional change. These may include such factors as increased socialization or decreased anxiety and negative symptoms.

In addition, although a modest number of inference tests were conducted when examining associations between cognitive and functional change, corrections for multiple inference testing were not conducted and these results would not have survived Type I error corrections. As such, care will need be taken when interpreting these findings until confirmation from future studies. Finally, it is also important to note that the measurement of social cognition in this study was restricted to the MSCEIT, and that future studies will need to expand to broader measures of social cognition. It should be noted, however, that these findings do support the recommendations of the MATRICS committee to use the emotion management branch of the instrument, which we have previously observed to be the most sensitive to social-cognitive treatment effects (Eack et al., 2007).

In summary, this first study of the effects of improved neurocognition and social cognition on functional outcome during a randomized trial of cognitive rehabilitation for early schizophrenia found that improvement in neurocognitive and social-cognitive domains both served as significant mediators of functional improvement. These results suggest that functional recovery from the illness might best be promoted through the early application of cognitive rehabilitation programs that target both social and non-social cognition.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: National Institute of Mental Health

This work was supported by NIMH grants MH 60902 (MSK) and MH 79537 (SME). We thank the late Gerard E. Hogarty, M.S.W. for his leadership and direction as Co-Principal Investigator of this study, and Susan Cooley M.N.Ed., Anne Louise DiBarry, M.S.N., Konasale Prasad, M.D., Haranath Parepally, M.D., Debra Montrose, Ph.D., Diana Dworakowski, M.S., Mary Carter, Ph.D., and Sara Fleet, M.S. for their help in various aspects of the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no competing financial or other conflicts of interest with this research.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braw Y, Bloch Y, Mendelovich S, Ratzoni G, Gal G, Harari H, Tripto A, Levkovitz Y. Cognition in young schizophrenia outpatients: comparison of first-episode with multiepisode patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(3):544–554. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Hoe M, Green MF. Neurocognitive change, functional change and service intensity during community-based psychosocial rehabilitation for schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. doi: 10.1017/S003329170900539X. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke JS, Hoe M, Long J, Green MF. How Neurocognition and Social Cognition Influence Functional Change During Community-Based Psychosocial Rehabilitation for Individuals with Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(5):1247–1256. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW. The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 1989;27(3):335–350. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The Functional Significance of Social Cognition in Schizophrenia: A Review. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(Suppl1):S44–S63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson WC, Zillmer EA. Unpublished manuscript. 1996. Tower of London-DX manual. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data using the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1977;39(1):1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Disability Evaluation Under Social Security. Washington, DC: Author; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Greeno CG, Pogue-Geile MF, Newhill CE, Hogarty GE, Keshavan MS. Assessing social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(2):370–380. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Cooley SJ, DiBarry AL, Montrose DM, Keshavan MS. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy for early-course schizophrenia: Effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(11):1468–1476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.11.1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy improves Emotional Intelligence in early course schizophrenia: Preliminary effects. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;89(1–3):308–311. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. Effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy on employment outcomes in early schizophrenia: Results from a two-year randomized trial. Research on Social Work Practice. doi: 10.1177/1049731509355812. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The Global Assessment Scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33(6):766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview For DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH. Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25(2):309–319. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the right stuff? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26(1):119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, Barch DM, Cohen J, Essock S, et al. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: The NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56(5):301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF, Olivier B, Crawley JN, Penn DL, Silverstein S. Social cognition in schizophrenia: Recommendations from the measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia new approaches conference. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2005;31(4):882–887. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GG, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual: Revised and Expanded. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, Zakzanis KK. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(3):426–445. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbener ES, Hill SK, Marvin RW, Sweeney JA. Effects of Antipsychotic Treatment on Emotion Perception Deficits in First-Episode Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1746–1748. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE. Personal Therapy for schizophrenia and related disorders: A guide to individualized treatment. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Flesher S. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: Proceed … with caution. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1992;18(1):51–57. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP. Cognitive Enhancement Therapy: The Training Manual. University of Pittsburgh Medical Center: Authors; 2006. Available through www.CognitiveEnhancementTherapy.com. [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, et al. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia. Effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):866–876. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC, Schooler NR the Collaborative Study Group. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients: III. Adjustment of nonrelapsed patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1974;31(5):609–618. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Eack SM. Durability and mechanism of effects of Cognitive Enhancement Therapy. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(12):1751–1757. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.12.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RSE, Bilder RM, Davis SM, Harvey PD, Palmer BW, Gold JM, Meltzer HY, Green MF, Capuano G, Stroup TS, et al. Neurocognitive Effects of Antipsychotic Medications in Patients With Chronic Schizophrenia in the CATIE Trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(6):633–647. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson G, Fairburn CG, Agras W. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–884. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3(1):97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Remediation in Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(12):1791–1802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Essock S, Fenton WS, Frese FJ, III, Gold JM, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, Part 1: Test Selection, Reliability, and Validity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Corrigan PW, Bentall RP, Racenstein J, Newman L. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121(1):114–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder C, Newton E, Frangou S, Wykes T. Which executive skills should we target to affect social functioning and symptom change? A study of a cognitive remediation therapy program. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(1):87–100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder C, Smedley N, Butt K, Bogner D, Wykes T. Cognitive predictors of social functioning improvements following cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32(Supplement 1):S123–S131. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Waltson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD. Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality. 1990;9(3):185–221. [Google Scholar]

- Schooler N, Weissman M, Hogarty G. Social adjustment scale for schizophrenics. In: Hargreaves WA, Attkisson CC, Sorenson J, editors. Resource material for community mental health program evaluators. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1979. pp. 290–303. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM) 79328. [Google Scholar]

- Sergi MJ, Green MF, Widmark C, Reist C, Erhart S, Braff DL, Kee KS, Marder SR, Mintz J. Cognition and Neurocognition: Effects of Risperidone, Olanzapine, and Haloperidol. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007a;164(10):1585–1592. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi MJ, Rassovsky Y, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF. Social Perception as a Mediator of the Influence of Early Visual Processing on Functional Status in Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):448–454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willet JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological Corp; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Newton E, Landau S, Rice C, Thompson N, Frangou S. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;94(1–3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]