Abstract

Both the 17‐item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17) and 30‐item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician‐rated (IDS‐C30) contain a subscale that assesses anxious symptoms. We used classical test theory and item response theory methods to assess and compare the psychometric properties of the two anxiety subscales (HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX) in a large sample (N = 3453) of outpatients with non‐psychotic major depressive disorder in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Approximately 48% of evaluable participants had at least one concurrent anxiety disorder by the self‐report Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ). The HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX were highly correlated (r = 0.75) and both had moderate internal consistency given their limited number of items (HRSDANX Cronbach's alpha = 0.48; IDS‐CANX Cronbach's alpha = 0.58). The optimal threshold for ascribing the presence/absence of anxious features was found at a total score of eight or nine for the HRSDANX and seven or eight for the IDS‐CANX. It would seem beneficial to delete item 17 (loss of insight) from the HRSDANX as it negatively correlated with the scale's total score. Both the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX subscales have acceptable psychometric properties and can be used to identify anxious features for clinical or research purposes. Copyright © 2011 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, rating scales, STAR*D, measurement‐based care

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has a lifetime prevalence rate of 15% to 20% and is a significant cause of disability worldwide (Murray and Lopez, 1996; McKenna et al., 2005; Moussavi et al., 2007). Individuals with MDD often have anxiety and sympathetic nervous system arousal, which characterizes anxious symptom features. Although depression with anxious features is not codified in the DSM‐IV‐TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), it has been defined in the literature as either MDD with high levels of anxiety symptoms, or the concurrent (not lifetime) presence of depression and anxiety (Fava et al., 2004).

Anxiety disorders are frequently comorbid with MDD. Studies have found comorbid anxiety (lifetime) in 60% to 65% of individuals with MDD in a community sample (Kessler et al., 1996) and comorbid anxiety disorder in 59.2% of individuals with MDD based on DSM‐IV criteria (Kessler et al., 2003). In clinical trial populations, prevalence rates of concurrent (not lifetime) anxious features of approximately 40% to 60% have been documented. Thus, roughly half of all patients who have MDD experience anxious symptoms and consequently suffer from increased levels of impairment (Fava et al., 2004; Lydiard and Brawman‐Mintzer, 1998).

While no standard measure exists for systematically identifying depressed outpatients with “anxious features” (Bramley et al., 1988), the six‐item anxiety/somatization factor within the 17‐item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17) (Hamilton, 1960, 1967; Cleary and Guy, 1977) has been used to assess anxiety as it contains items that measure psychic and somatic anxiety symptoms (Fava et al., 2008). However, no studies to date have assessed the psychometric properties of this anxiety/somatization factor (HRSDANX) in depressed patients with and without anxious features (Bagby et al., 2004). The 30‐item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician‐rated (IDS‐C30) (Rush et al., 1986, 1996) also assesses anxious features through the inclusion of items that assess anxious mood, somatic complaints, and sympathetic arousal. Again, no psychometric studies have yet assessed the anxiety subscale (IDS‐CANX).

The current study assessed the psychometric performance of both the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX in depressed outpatients enrolled in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. We hypothesized that both scales would have satisfactory psychometric properties.

Materials and methods

Study overview

The STAR*D study aimed to define prospectively the comparative effectiveness of several antidepressant treatments in individuals with non‐psychotic MDD who have an unsatisfactory clinical outcome to an initial and, if necessary, subsequent treatment(s) (Fava et al., 2003; Rush et al., 2004).

Fourteen Regional Centers oversaw the STAR*D study, which was conducted at 18 primary and 23 psychiatric care settings. The STAR*D protocol was developed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved and monitored by the study's National Coordinating Center (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX), Data Coordinating Center (University of Pittsburgh Epidemiology Data Center, Pittsburgh, PA), the institutional review boards at each Clinical Site and Regional Center, and the Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; Bethesda, MD). Prior to enrollment, all potential risks, benefits, and adverse events associated with STAR*D participation were explained and a written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Study population

STAR*D enrolled 4041 outpatients from across the United States, 18 to 75 years of age, who were diagnosed with non‐psychotic MDD (based on the Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) and had a baseline HRSD17 score ≥ 14 (moderate severity). Patients were excluded if they had schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, anorexia nervosa, a current primary diagnosis of bulimia nervosa or obsessive‐compulsive disorder, psychiatric disorders or substance abuse that required immediate hospitalization, general medical conditions or concomitant medications that contraindicated the use of protocol treatments in the first two treatment steps, were using a targeted psychotherapy for depression, or had a well‐documented history of non‐response or intolerance (in the current major depressive episode) to one or more of the protocol treatments in the first two treatment steps. The study also excluded patients who were breastfeeding, pregnant, or trying to become pregnant.

Assessment measures

Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected at the screening/baseline visit. Participants completed the self‐report Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ) (Zimmerman and Mattia, 1999) to identify the following concurrent anxiety disorders: Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder, Social Phobia, Obsessive‐Compulsive Disorder, and Agoraphobia (Zimmerman and Mattia, 1999, 2001; Castel et al., 2007; Gibbons et al., 2009). The presence of each disorder was determined based on the specific PDSQ subscales (each PDSQ subscale has an 89% sensitivity and 97% negative predictive value), which have been found to be valid for assessing DSM Axis‐I categories (Gibbons et al., 2009; Rush et al., 2005). Within 72 hours of the screening/baseline visit, trained Research Outcome Assessors (ROAs), who were masked to treatment and to the results of the PDSQ, conducted telephone interviews to complete the HRSD17 and the IDS‐C30. A study by Rush et al. (2006a) found the telephone interview format of the HRSD17 and the IDS‐C30 to be reliable and valid.

Defining anxious features

For this report, we defined the presence of anxious features as a minimum of one anxiety diagnosis based on the PDSQ (Zimmerman and Mattia, 1999). The HRSDANX was based on the analyses of Cleary and Guy (1977), while the IDS‐CANX was based on prior analyses (Gullion and Rush, 1998; Bernstein et al., 2006) and expert consensus.

Statistical analysis

Data for these analyzes were obtained by the ROA at baseline and at exit from the first treatment trial with one antidepressant medication (citalopram) (Rush et al., 2006b). Only those participants (N = 3453) who were not on any antidepressant medications at baseline were included in the analyses. Summary statistics were used to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Means and standard deviations are presented for continuous variables; percentages are presented for discrete variables. The association between sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and the number of anxiety comorbidities was estimated using a Poisson regression model that was adjusted for dispersion. Results were interpreted based on standard guidelines for acceptable psychometric properties (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). A p‐value of < 0.05 indicated a significant association.

To identify a possible threshold on the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX subscales for the identification of anxious features, sensitivity and specificity were calculated when comparing each subscale total to the presence of anxiety (yes/no). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated from the sensitivity and specificity estimates.

Similar to other investigations (Bernstein et al., 2007, 2009), data were analyzed using both classical test theory (CTT) (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994) and modern test theory (item response theory, IRT) (Embretson and Reise, 2000). CTT's key outputs are the item means, which define level of response, and item/total correlations (r it), which define the strength of relation between the item and the scale, plus the scale mean, scale standard deviation and a measure of internal consistency reliability, usually Cronbach's alpha. CTT assumes the dimension to be assessed (anxiety in the present case) is the sum of the item scores, whereas IRT views the dimension as a latent variable to be inferred. The two are complementary. Although CTT rests upon more familiar constructs so that its results are generally rather easily understood, IRT allows the sensitivity of the test in making discriminations at various levels of the latent variable, focusing on the reliabilities instead of treating it as a constant (the internal consistency, i.e. coefficient alpha) and focusing on the scores as is done in CTT. This analysis involves the test information function (TIF). The Samejima graded response model (Samejima, 1997) was employed for IRT analysis. IRT was also used to equate scores on the two tests being considered (Lord, 1980; Orlando et al., 2000).

IRT models can use a wide array of response formats (e.g. binary, multiple choice), but the Samejima model specifically assumes a graded response format. Thus, for the purpose of these analyses, we chose the Samejima model as it was designed for tests that employ an ordered series of responses, such as the 0–3 scale of the IDS‐C30. It is assumed that the probability of a participant choosing the higher of two response categories is a logistic (S‐shaped) function of the latent trait (symbolized “Θ”), which for this study represents depression. In this analysis, there are three possible categorizations (0 versus 1, 2, or 3 – normal versus pathological; 0 or 1 versus 2 or 3 – normal and mildly pathological versus moderately or severely pathological; and 0, 1, or 2 versus 3 – normal, mildly pathological, and moderately pathological versus severely pathological). The three categorizations are assumed to produce a common slope but different locations along the anxiety axis. Collectively, these categorizations form category response functions. The slope that is common to the three functions is designated “a”. The three locations along the depression axis are designated “b 1”, “b 2”, and “b 3” (“bi” collectively). A steeper slope indicates a more discriminating item. The higher the values of b, the less likely the more pathological category is chosen, yielding four parameter estimations per item. In view of the six HRSDANX items and five IDS‐CANX items, the item analysis generates 24 parameter estimates for the former measure and 20 for the latter. These a and bi parameters are of central interest when groups are being compared to investigate what is known as differential item functioning. However, they are of lesser interest in this one‐group design, so they have been omitted. They can be obtained upon request from the first author. The computation of TIF is described in Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) and Embretson and Reise (2000).

The Samejima model does assume that the items define a unidimensional scale. Scale dimensionality was inferred by parallel analysis (Horn, 1965; Humphreys and Ilgen, 1969; Humphreys and Montanelli, 1975; Montanelli and Humphreys, 1976). This involves generating matrices of random normal deviates with the same number of variables and observations as the obtained data. The random data are then factored. In the present case, 50 such random matrices were generated, and the results averaged. The dimensionality of the obtained data is the number of eigenvalues greater than in the randomly generated factors. Specifically, a series of variables is unidimensional if the first eigenvalue it generates is larger than the first eigenvalue of the randomly‐generated data but the reverse is true of the second eigenvalue.

Statistical software packages used included SAS (Version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for CTT and factor analyses, and MULTILOG (Version 7, Scientific Software International, Lincolnwood, Il) for IRT analyses.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

In our study sample (N = 3453), most participants were female and the racial composition was comparable to the US population (US Census Bureau, 2000) (Table 1). Although statistically significant associations were found in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, many were not clinically meaningful (Tables 1 and 2). Of clinical relevance, participants with anxiety comorbidities had higher rates of unemployment, correspondingly lower monthly household incomes, greater depression severity on both clinician‐rated and self‐report measures, and were more likely to have attempted suicide.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants by number of anxiety‐related disorders

| Number of anxiety related disordersa | Analyses | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | All (N = 3453) | 0 (N = 1799) | 1 (N = 852) | 2 (N = 415) | 3 (N = 203) | 4 (N = 117) | 5 (N = 67) | ||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | β | SE | χ 2 | df | p | |

| Male gender | 1291 | 37.4 | 718 | 39.9 | 324 | 38.0 | 136 | 32.8 | 59 | 29.1 | 34 | 29.1 | 20 | 29.9 | −0.0977 | 0.0259 | 14.2 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| Race | 24.8 | 2 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| White | 2622 | 76.0 | 1414 | 78.7 | 645 | 75.8 | 301 | 72.7 | 143 | 70.4 | 79 | 67.5 | 40 | 59.7 | |||||

| Black | 586 | 17.0 | 259 | 14.4 | 151 | 17.7 | 75 | 18.1 | 51 | 25.1 | 28 | 23.9 | 22 | 32.8 | 0.1595 | 0.0316 | 25.5 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 241 | 7.0 | 124 | 6.9 | 55 | 6.5 | 38 | 9.2 | 9 | 4.4 | 10 | 8.5 | 5 | 7.5 | 0.0475 | 0.0486 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.3285 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 426 | 12.3 | 186 | 10.3 | 103 | 12.1 | 68 | 16.4 | 38 | 18.7 | 22 | 18.8 | 9 | 13.4 | 0.1398 | 0.0357 | 15.3 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Employment status | 42.8 | 2 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Employed | 2001 | 58.0 | 1095 | 60.9 | 518 | 60.9 | 219 | 52.8 | 97 | 47.8 | 44 | 37.6 | 28 | 41.8 | |||||

| Unemployed | 1250 | 36.2 | 591 | 32.9 | 285 | 33.5 | 173 | 41.7 | 97 | 47.8 | 66 | 56.4 | 38 | 56.7 | 0.1651 | 0.0257 | 41.2 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Retired | 200 | 5.8 | 113 | 6.3 | 47 | 5.5 | 23 | 5.5 | 9 | 4.4 | 7 | 6.0 | 1 | 1.5 | −0.0091 | 0.0558 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.8707 |

| Medical insurance | 47.2 | 2 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Any private | 1762 | 52.6 | 997 | 57.1 | 435 | 52.6 | 187 | 47.1 | 82 | 41.2 | 35 | 30.7 | 26 | 41.3 | |||||

| Public only | 447 | 13.4 | 190 | 10.9 | 106 | 12.8 | 66 | 16.6 | 44 | 22.1 | 32 | 28.1 | 9 | 14.3 | 0.2344 | 0.0365 | 41.2 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| None | 1138 | 34.0 | 560 | 32.1 | 286 | 34.6 | 144 | 36.3 | 73 | 36.7 | 47 | 41.2 | 28 | 44.4 | 0.1249 | 0.0277 | 20.3 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | 3.9 | 3 | 0.2761 | ||||||||||||||||

| Never married | 1036 | 30.0 | 525 | 29.2 | 278 | 32.7 | 131 | 31.6 | 55 | 27.1 | 31 | 26.5 | 16 | 23.9 | 0.0091 | 0.0298 | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 1448 | 41.9 | 781 | 43.4 | 348 | 40.9 | 158 | 38.1 | 88 | 43.3 | 47 | 40.2 | 26 | 38.8 | |||||

| Divorced/separated | 870 | 25.2 | 444 | 24.7 | 200 | 23.5 | 114 | 27.5 | 53 | 26.1 | 37 | 31.6 | 22 | 32.8 | 0.0578 | 0.0309 | |||

| Widowed | 98 | 2.8 | 49 | 2.7 | 25 | 2.9 | 12 | 2.9 | 7 | 3.4 | 2 | 1.7 | 3 | 4.5 | 0.0465 | 0.0749 | |||

| Age at first episode <18 | 1280 | 37.4 | 603 | 33.8 | 340 | 40.3 | 185 | 44.9 | 76 | 38.0 | 50 | 43.9 | 26 | 40.0 | 0.0827 | 0.0254 | 10.6 | 1 | 0.0011 |

| At least one prior episode | 2373 | 74.0 | 1221 | 72.3 | 594 | 75.4 | 284 | 74.7 | 146 | 79.8 | 80 | 75.5 | 48 | 80.0 | 0.0625 | 0.0298 | 4.4 | 1 | 0.0362 |

| Ever attempted suicide | 574 | 16.6 | 248 | 13.8 | 144 | 16.9 | 88 | 21.2 | 43 | 21.3 | 34 | 29.3 | 17 | 25.4 | 0.1633 | 0.0315 | 26.9 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Family history of depression | 1887 | 55.1 | 974 | 54.6 | 464 | 54.9 | 232 | 56.3 | 117 | 57.9 | 63 | 54.3 | 37 | 56.1 | 0.0160 | 0.0250 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.5226 |

| Months since index onset ≥24 | 853 | 24.9 | 410 | 23.0 | 191 | 22.7 | 138 | 33.6 | 56 | 28.0 | 37 | 31.6 | 21 | 31.8 | 0.1003 | 0.0280 | 12.8 | 1 | 0.0003 |

| Psychiatric care | 2115 | 61.3 | 1086 | 60.4 | 536 | 62.9 | 262 | 63.1 | 129 | 63.5 | 61 | 52.1 | 41 | 61.2 | 0.0006 | 0.0254 | <0.01 | 1 | 0.9820 |

Assessed by the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants by number of anxiety‐related disorders

| Number of anxiety related disordersa | Analyses | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 3453) | 0 (N = 1799) | 1 (N = 852) | 2 (N = 415) | 3 (N = 203) | 4 (N = 117) | 5 (N = 67) | |||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | β | SE | χ b | df | p | |

| Age | 40.3 | 13.2 | 41.7 | 13.6 | 38.8 | 12.7 | 38.3 | 12.9 | 39.5 | 12.4 | 39.4 | 12.0 | 40.4 | 11.5 | −0.0035 | 0.0009 | 13.5 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| Education (years) | 13.5 | 3.2 | 14.0 | 3.3 | 13.4 | 3.1 | 12.9 | 3.3 | 12.3 | 3.0 | 11.7 | 2.6 | 12.5 | 2.4 | −0.0362 | 0.0038 | 93.1 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Monthly household incomeb | 2440 | 3191 | 2768 | 3735 | 2346 | 2569 | 2117 | 2582 | 1587 | 1788 | 1371 | 1744 | 1342 | 1323 | −0.0322 | 0.0049 | 42.6 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Age at first episode | 25.3 | 14.3 | 27.0 | 15.0 | 24.2 | 13.5 | 22.6 | 13.2 | 22.7 | 12.3 | 22.6 | 12.5 | 21.6 | 12.4 | −0.0056 | 0.0009 | 38.6 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Years since first episode | 15.1 | 13.1 | 14.7 | 13.5 | 14.6 | 12.4 | 15.6 | 12.8 | 17.0 | 12.9 | 16.9 | 12.7 | 18.8 | 12.8 | 0.0029 | 0.0009 | 9.4 | 1 | 0.0021 |

| N Episodes | 5.4 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 9.8 | 5.6 | 9.2 | 6.7 | 10.6 | 5.7 | 10.3 | 8.4 | 11.7 | 0.0038 | 0.0013 | 8.3 | 1 | 0.0040 |

| Months since index onset | 24.2 | 51.6 | 21.2 | 45.3 | 23.5 | 53.7 | 32.3 | 60.5 | 21.8 | 32.8 | 42.3 | 82.7 | 42.0 | 80.4 | 0.0009 | 0.0002 | 20.4 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| N Moderate to severe GMCsc | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | s1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.0481 | 0.0093 | 26.6 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| HRSD17 | 19.9 | 6.5 | 17.9 | 6.1 | 20.3 | 6.0 | 22.5 | 5.9 | 23.4 | 6.0 | 26.8 | 5.5 | 28.2 | 4.1 | 0.0386 | 0.0019 | 410 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| IDS‐C30 | 35.5 | 11.5 | 31.7 | 10.6 | 36.5 | 10.4 | 40.4 | 10.4 | 42.7 | 10.2 | 47.8 | 10.1 | 50.8 | 7.1 | 0.0233 | 0.0011 | 467 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| QIDS‐SR16 | 15.4 | 4.3 | 14.1 | 4.1 | 15.8 | 4.0 | 17.4 | 3.6 | 17.9 | 3.9 | 19.0 | 3.6 | 19.8 | 3.6 | 0.0561 | 0.0030 | 361 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| Q‐LES‐Q | 41.8 | 15.2 | 45.6 | 14.2 | 40.6 | 14.2 | 37.5 | 14.8 | 32.5 | 14.7 | 30.9 | 16.7 | 27.4 | 15.6 | −0.0131 | 0.0008 | 246 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| SF12 Mental | 26.5 | 8.6 | 27.7 | 9.0 | 25.5 | 8.1 | 24.4 | 7.6 | 25.1 | 7.1 | 26.8 | 9.1 | 23.4 | 7.4 | −0.0092 | 0.0015 | 36.8 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| SF12 Physical | 49.8 | 11.8 | 51.5 | 11.6 | 50.0 | 11.4 | 48.1 | 11.4 | 44.4 | 11.7 | 41.7 | 12.0 | 40.0 | 10.4 | −0.0118 | 0.0010 | 127 | 1 | <0.0001 |

| WSAS | 23.4 | 9.3 | 21.0 | 9.1 | 24.3 | 8.9 | 26.4 | 8.2 | 29.2 | 7.7 | 29.5 | 8.5 | 30.9 | 7.8 | 0.0219 | 0.0014 | 235 | 1 | <0.0001 |

Note: GMC, general medical comorbidity; HRSD17, 17‐item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IDS‐C30, 30‐item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician‐rated; QIDS‐SR16, 16‐item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self‐rated; Q‐LES‐Q, Quality of Life and Enjoyment Satisfaction Questionnaire; SF12, 12‐item short‐form health survey; WSAS, Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Assessed by the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire.

Beta based on units of $1000.

Assessed by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale.

CTT analysis

Given their brevity, both the HRSDANX (Cronbach's alpha = 0.48) and the IDS‐CANX (Cronbach's alpha = 0.58) demonstrated modest internal consistency (Table 3). The HRSD17 and the IDS‐C30 were highly correlated (r = 0.89). The HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX were also highly correlated (r = 0.75), indicating that they tend to measure the same general construct. One negative feature of the HRSDANX was that the correlation between item 17 (loss of insight) and the total score was essentially zero at both baseline and exit (rs = −0.07 and −0.15, respectively), suggesting it is irrelevant to the scale. Disattenuation (correction for unreliability) suggested that virtually all of the systematic variance in each respective test is shared with the other.

Table 3.

Comparison of HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX

| Baseline | Exit | Changea | Analyses | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Item | M | SD | r it | M | SD | r it | M | SD | t | df | p | ES |

| HRSDANX | α = 0.48 | α = 0.65 | |||||||||||

| 10 | Anxiety, psychic | 1.64 | 0.98 | 0.23 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.98 | 26.6 | 4924 | <0.0001 | 0.76 |

| 11 | Anxiety, somatic | 1.60 | 0.90 | 0.39 | 1.27 | 0.97 | 0.49 | 0.33 | 0.94 | 12.5 | 4894 | <0.0001 | 0.36 |

| 12 | Somatic symptoms, gastrointestinal | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.74 | 17.3 | 4577 | <0.0001 | 0.49 |

| 13 | Somatic symptoms, general | 1.41 | 0.74 | 0.31 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 24.9 | 4845 | <0.0001 | 0.71 |

| 15 | Hypochondriasis | 0.69 | 0.87 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.82 | 8.4 | 4844 | <0.0001 | 0.24 |

| 17 | Insight | 0.03 | 0.20 | –0.07 | 0.06 | 0.31 | –0.15 | –0.03 | 0.26 | 3.5 | 4274 | 0.0004 | 0.10 |

| Total | 6.03 | 2.52 | 3.86 | 2.84 | 2.17 | 2.69 | 28.4 | 4853 | <0.0001 | 0.81 | |||

| IDS‐CANX | α = 0.58 | α = 0.68 | |||||||||||

| 7 | Mood (anxious) | 1.37 | 0.88 | 0.36 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.87 | 25.1 | 4924 | <0.0001 | 0.72 |

| 25 | Somatic complaints | 1.31 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 1.01 | 12.7 | 4924 | <0.0001 | 0.36 |

| 26 | Sympathetic arousal | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.45 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.79 | 8.6 | 4924 | <0.0001 | 0.25 |

| 27 | Panic | 0.62 | 0.94 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 13.7 | 4598 | <0.0001 | 0.39 |

| 28 | Gastrointestinal | 0.63 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.84 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 3.6 | 4924 | 0.0003 | 0.10 |

| Total | 4.85 | 2.75 | 3.25 | 2.81 | 1.60 | 2.78 | 20.2 | 4924 | <0.0001 | 0.57 | |||

Note: HRSDANX, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression anxiety subscale; IDS‐CANX, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology –Clinician‐rated anxiety subscale; r it, item‐total correlation coefficient.

Change from baseline (entry into STAR*D Level 1) to exit (end of STAR*D Level 1).

The values of item‐total correlation (r it), and thus the overall coefficients alpha, increased from baseline to exit for both subscales (Table 3), which is expected given the greater variation among individual items at exit. At baseline, somatic anxiety, somatic symptoms‐general and hypochondriasis all contributed to the HRSDANX scale total, and were joined by psychic anxiety at exit. In fact, the baseline and exit values of r it have a very high correlation of 0.96. The most discriminating IDS‐CANX item at baseline was sympathetic arousal, followed by the nearly equal contribution of panic/phobic symptoms and anxious mood. At exit, the five items were closer to equal, with anxious mood and sympathetic arousal being the two most discriminating items. In general, the correlation between baseline and exit values of r it for the two subscales was relatively similar.

Table 3 shows the change in each item's mean score from baseline to exit (effect sizes), effect sizes in terms of Cohen's d = mean change/SD, the corresponding values of t testing the null hypothesis that the mean change was zero, and the total HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX scale scores. Overall, the two scales were similar in effect size (HRSDANX = 0.81 versus IDS‐CANX = 0.57) and the largest effect size was seen in psychic anxiety and general somatic symptoms on the HRSDANX and anxious mood on the IDS‐CANX.

All correlations of the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX with the anxiety dimensions of the PDSQ were significant (p < 0.0001) (Table 4). Although the correlations between the IDS‐CANX and PDSQ anxiety dimensions were slightly higher than those between HRSDANX and PDSQ, these differences were modest.

Table 4.

Correlations between the PDSQ anxiety subscales, HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX a (N = 3453)

| PDSQ anxiety subscale | HRSDANX | IDS‐CANX |

|---|---|---|

| Post traumatic stress | 0.31 | 0.41 |

| Panic | 0.34 | 0.42 |

| Agorophobia | 0.42 | 0.51 |

| Social phobia | 0.25 | 0.31 |

| Generalized anxiety | 0.16 | 0.24 |

Note: HRSDANX, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression Anxiety/Somatization Factor; IDS‐CANX, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Anxiety Factor; PDSQ, Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire.

All correlations were significant at p < 0.0001.

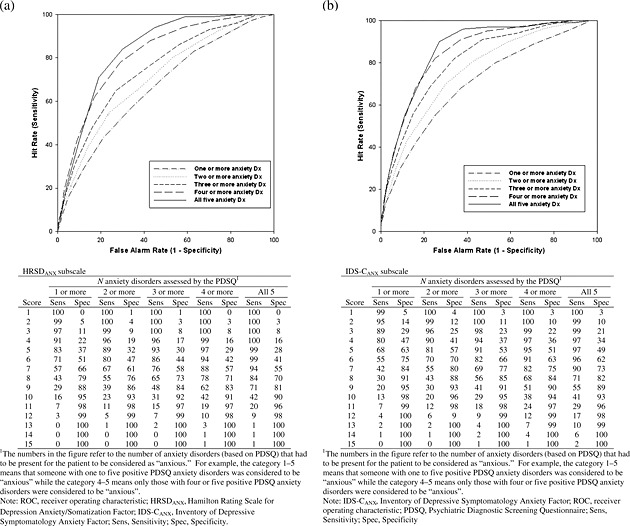

Sensitivity and specificity

Approximately 48% of participants had at least one PDSQ‐defined anxiety disorder. ROC curve analyses were estimated for the PDSQ anxiety diagnoses in each subscale (Figure 1) to examine the sensitivity and specificity estimates. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the HRSDANX was 0.656 for 1–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses, 0.702 for 2–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses, 0.740 for 3–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses, and 0.809 for 4–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses. For the IDS‐CANX, the AUC was 0.701 for 1–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses, 0.758 for 2–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses, 0.808 for 3–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses, and 0.849 for 4–5 PDSQ anxiety diagnoses. The AUC was greatest when all five anxiety diagnoses of the PDSQ were examined in relation to the HRSDANX (AUC = 0.833) and IDS‐CANX (AUC = 0.860) range of cut‐off scores. The greater area under the curve that is above the line of discrimination, the more valid is the classification system. Sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing depressed participants with and without at least one concurrent anxiety disorder were maximized with a cut‐off score of eight or nine for the HRSDANX, and seven or eight for the IDS‐CANX.

Figure 1.

ROC curve for the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX factors: (a) HRSDANX ROC curve; (b) IDS‐CANX ROC curve.

Factor analyses

The obtained first and second eigenvalues were 1.80 and 0.99 for the baseline HRSDANX, 2.37 and 0.97 for the exit HRSDANX, 1.99 and 1.018 for the baseline IDS‐CANX and 2.25 and 0.95 for the exit IDS‐CANX. The corresponding simulated eigenvalues were 1.05 and 1.05, 1.06 and 1.03, 1.05 and 1.021, and 1.06 and 1.01. Thus, the obtained first eigenvalue exceeded the simulated first eigenvalue, but the reverse was true for the second eigenvalue. This means that the two measures were unidimensional at both baseline and exit, fulfilling the requirements of the IRT analysis.

IRT analyses

The HRSDANX was better able to resolve differences in anxiety up to Θ of about 1.0 (Figure 2), which represents the bottom 84% of the sample (in reference to level of anxiety) since the scale for Θ is the normal distribution. Beyond this point, the IDS‐CANX was the more sensitive to anxious features. Thus, the HRSDANX was more sensitive to anxious features in participants with low depression severity, whereas the IDS‐CANX was more sensitive to anxious features in participants with moderate to high depression severity.

Figure 2.

Test information function for the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX.

Test equating

Test equating involves associating total test scores on each test with values of the dimension under investigation, commonly denoted “Θ”. Total scores on each test that have similar values of Θ derived from the same sample are considered matched. Table 5 contains the matching scores on the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX with their estimated values of Θ.

Table 5.

Equated scores on the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX a

| HRSDANX | IDS‐CANX | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw score | Θ | Raw score | Θ |

| 0 | −1.40 | 0 | −1.20 |

| 1 | −0.84 | 1 | −0.63 |

| 2 | −0.48 | 2 | — |

| 3 | −0.17 | 3 | −0.27 |

| 4 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.01 |

| 5 | 0.36 | 5 | 0.29 |

| 6 | 0.60 | 6 | 0.54 |

| 7 | 0.84 | 7 | 0.78 |

| 8 | 1.10 | 8 | 1.00 |

| 9 | 1.30 | 9 | 1.20 |

| 10 | 1.50 | 10 | 1.50 |

| 11 | 1.80 | 11 | 1.70 |

| 12 | 2.00 | 12 | 1.90 |

| 13 | 2.30 | 13 | 2.10 |

| 14 | 2.50 | 14 | 2.40 |

| 15 | 2.70 | 15 | 2.70 |

| 16 | 2.90 | — | — |

| 17 | 3.30 | — | — |

Note: HRSDANX, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression Anxiety/Somatization Factor (N = 2697); IDS‐CANX, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Anxiety Factor (N = 2698).

Test equating involves associating raw scores on each test with values of the dimension under investigation denoted Θ, which in this case are anxious symptom features. The total range for the HRSDANX is 0–18 and the total range for the IDS‐CANX is 0–15.

Discussion

Both the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX subscales were found to have adequate psychometric properties and were moderately sensitive indicators of anxious features in depressed outpatients. IDS‐CANX demonstrated a moderate level of internal consistency. The lack of redundancy in the IDS‐CANX items suggests that all are valuable. The high correlation between the subscales supported their concurrent validity, and both showed discriminant ability in identifying patients with anxious features. Factor analytic methods indicated that both scales were unidimensional. The IDS‐CANX had greater sensitivity to anxious features in patients with moderate to severe depression, while the HRSDANX had greater sensitivity to anxious features in patients with mild depression severity.

CTT and IRT analyses indicated that HRSDANX item 17 (loss of insight) may be problematic. Its removal improved the measure's Cronbach's alpha coefficient (increased to 0.54), suggesting greater internal consistency among the remaining five items (removal of any of these items lowered alpha between 0.37 and 0.49). Item 17 has been found to have variable internal reliability and poor inter‐rater reliability (Bagby et al., 2004). Other investigations of factors on the HRSD17 have also reported mixed results (Fleck et al., 1995; Pancheri et al., 2002). Recent research (Pancheri et al., 2002) suggests that the HRSD17 contains two independent anxiety factors: somatic anxiety (including somatic anxiety, hypochondriasis, somatic energy, appetite, and insomnia symptoms) and psychic anxiety (including psychic anxiety, psychomotor agitation, insight, and guilt). This dispute, however, does not bear upon what we found to be a unidimensional structure of the six anxiety items.

The IDS‐C30 has been well validated as a comprehensive measure of depression severity (Rush et al., 1996; Trivedi et al., 2004) with demonstrated significant strengths (e.g. excellent psychometric properties, structured gradient metric, sensitivity to change, and availability of self‐report). Bernstein et al. (2006) found that the IDS‐C30 had two dimensions, a depressive dimension that consists mainly of core depressive items, and a second dimension containing somatic and anxiety items (e.g. somatic complaints, sympathetic arousal, gastrointestinal complaints). Our investigation confirms that certain items contribute to a somatic/anxiety domain.

The threshold total score by which to identify anxious features with either subscale depends on the desired ratio between sensitivity (i.e. correctly identifying depressed patients with anxious features) and specificity (i.e. correctly identifying depressed patients without anxious features). Ideally, the threshold should maximize both sensitivity and specificity (Loong, 2003). Based on this paradigm, the thresholds that maximized sensitivity and specificity in this study (based on 69 participants with five or more anxiety disorders) were 8–9 for the HRSDANX and 7–8 for the IDS‐CANX. The cut‐off score previously recommended for the HRSDANX (Cleary and Guy, 1977) and used in clinical trials was seven (Fava et al., 2004, 2008), which the present study indicates would result in high sensitivity (94.2) but moderate specificity (55.5). This could result in some over‐identification of patients with anxious features.

Differences between the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX

The HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX are unitary measures of anxious features, but these subscales differ in terms of item content (i.e. face validity) and rating metric. The face validity of these scales is different based on their respective item content. Both measure physical and psychic anxious symptoms, but the HRSDANX includes items related to appetite, energy, and insight, all core depressive features in the DSM‐IV‐TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Also, Gullion and Rush (1998) reported HRSD17 item 13 (somatic symptoms: general) loaded on the “hedonic capacity” factor, and item 17 (loss of insight) was excluded from their analyses as it was endorsed by less than 25% of the participant sample and could have obscured factor construction. Other studies have also suggested that item 17 does not contribute to the HRSD17 (Bech, 1981; Bech et al., 1981). The present study further suggests that item 17 was poor in discriminating between the presence and absence of anxious features. Thus, the HRSDANX may have poor face validity, as only two of the six items are related to anxiety. The IDS‐CANX items, however, are representative of symptoms included in DSM‐IV‐TR anxiety spectrum disorders. These items are germane to anxiety, somatic and phobic symptoms, and demonstrate good discriminatory ability (e.g. the removal of any one item from the subscale did not result in a significant change in the Cronbach's alpha, which indicates its relative importance in the IDS‐CANX).

The HRSD17 and the HRSDANX weigh items disproportionately by assigning greater weight to psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety and hypochondriacal symptoms. This could be problematic as there is no theoretical or empirical basis for the HRSDANX item metric‐rating assignments. In contrast, the IDS‐CANX assigns equal weight to all items with the rationale that all contribute equally to the total score.

Utility of the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX

Both the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX would be useful for systematically monitoring anxious features in clinical practice and research studies. Depressed patients with comorbid anxiety may have increased levels of clinical impairment and functional impairment (Fava et al., 2004), and may be less likely to achieve remission with antidepressant medications than depressed patients without anxiety (Fava et al., 2008, 1997). Thus, the monitoring and treatment of anxiety symptoms can enhance clinical practice by optimizing antidepressant therapy and overall clinical outcome (Zimmerman and McGlinchey, 2008). Further, the monitoring of anxiety symptoms is warranted for research studies to address their effects on therapeutic outcome. Use of the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX by clinicians or trained interviewers is feasible (Duffy et al., 2008) and may enhance time management and office‐visit efficiency because they are subscales of the HRSD17 and the IDS‐C30, respectively, and thus enable depression and anxiety symptoms to be monitored with a single instrument. Both of these psychometrically sound instruments can play a vital role for psychiatric practitioners and researchers with the advent of measurement‐based care (Trivedi and Daly, 2007; Rush et al., 2009). Indeed, recommendations from international studies suggest that many clinicians and clinical practices could maximize efficiency and increase quality of care through the use of depression and anxiety rating instruments (Gibody et al., 2002; Pancheri et al., 2002; Laugharne 2009; Zimmerman et al., 2010).

Limitations

The study sample comprised patients who did and did not remit with citalopram, which could introduce a treatment bias as alternative therapeutic interventions (e.g. psychotherapy) may have resulted in different change scores on the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX. However, these measures will be useful in assessing anxious features in depressed patients regardless of treatment intervention. This study used the self‐report PDSQ to diagnose anxiety disorders, an instrument designed to compliment, not replace, clinical interview strategies (e.g. SCID‐I [First et al., 1997]) for diagnoses (Zimmerman and Chelminski, 2006). It may be possible that the sensitivity and specificity of the HRSD17 and IDS‐C30 anxiety subscales could be different if they were validated by the SCID‐I. However, the STAR*D trial benefited from the moderate to strong sensitivity and negative predictive value of the PDSQ anxiety disorder subscales (Rush et al., 2005; Zimmerman and Chelminski, 2006). Further, the PDSQ has been shown to be a valid instrument for assessing DSM diagnostic categories (Gibbons et al., 2009). Nonetheless, a structured clinical interview such as the SCID‐I would be helpful in future validation studies. A second limitation was not comparing either subscale to pure anxiety rating measures such as the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 2005) or the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HRSA) (Hamilton, 1959), which would have improved the reliability and validity of the psychometric analyses. However, we did compare the HRSDANX and IDS‐CANX to the PDSQ anxiety dimensions and found convergent validity for both subscales. Although not a limitation of the present study, both subscales had modest alpha levels, which were likely related to the small number of items (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994) that constitute the respective scales. In future investigations, these subscales may benefit from the addition of newer items that measure anxiety spectrum symptoms. One approach to optimize the item content would be to combine these psychometric data with the clinimetric method (Bech, 2004; Emmelkamp, 2004). Clinimetrics principally focuses on the sensitivity of the rating scale to discriminate between cohorts and has been used to evaluate and develop other depression and anxiety rating scales (Sirri et al., 2008; Bech, 2009). Lastly, the high correlation between the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX could have been due to their administration by the same trained ROA.

Conclusion

Both the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX have adequate psychometric properties and reliably identify anxious features in depressed patients. Thus, both may be useful for clinical and research work by systematically monitoring both depressive symptoms and anxious features in order to optimize therapeutic outcome. Given the validity and utility of self‐report measures of depression and anxiety (Prusoff et al., 1972; Fava et al., 1986), future research to evaluate the anxiety subscale of the patient self‐report version of the IDS is warranted. Further, future studies should examine the HRSDANX and the IDS‐CANX for sensitivity to change with antidepressant therapies as well as their predictive validity. In future studies, the utility of the HRSDANX to identify anxious features may benefit from the removal of item 17 (loss of insight).

Declaration of interest statement

Dr Alpert has served as in the advisor/consultative relationship role with Eli Lilly & Company, Pamlab LLC, and Pharmavite LLC. Dr Biggs has served as a consultant for Bristol‐Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaoxSmithKline, Merck, and Pfizer. Dr Fava has provided scientific consultation to or served on the Advisory Boards for Aspect Medical Systems, Astra‐Zeneca, Bayer AG, Biovail Pharmaceuticals, Inc., BrainCells, Inc. Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Compellis, Cypress Pharmaceuticals, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly & Company, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Fabre‐Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal GmBH, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, J & J Pharmaceuticals, Knoll Pharmaceutical Company, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Inc., Neuronetics, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Organon Inc., PamLab, LLC, Pfizer Inc, PharmaStar, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Sepracor, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Somaxon, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories. He has been on speaker bureaus for Astra‐Zeneca, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Organon Inc., Pfizer Inc, PharmaStar, Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories. He has received research/grant support from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Aspect Medical Systems, Astra‐Zeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, J & J Pharmaceuticals, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Organon Inc., PamLab, LLC, Pfizer Inc, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories. He has equity holdings in Compellis, MedAvante. Dr Husain has served on Advisory Boards for AstraZeneka, VersusMed, Avinar, Boston Scientific, MEASURE, Bristol‐Meyer‐Squibb, and Clinical Advisors and on speakers bureaus for Cyberonics, Inc., Avinar, Inc., Cerebrio, Inc., AstraZeneka, Bristol‐Meyers‐ Squibb, Optima/Forrest Pharmaceuticals, Glaxo‐Smith‐Kline, Forrest Pharmaceuticals, and Janssen. Dr Kornstein has served on Advisory Boards/recieved honoraria from Pfizer, Inc., Wyeth, Inc., Lilly, Inc., Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Warner‐Chilcott, Inc., Biovail Laboratories, Berlex Laboratories, Forest Laboratories, Neurocrine, and Sepracor, Inc. She has received book royalties from Guilford Press. Dr Morris has been a consultant for Pfizer. Dr Rush has provided scientific consultation to or served on Advisory Boards for Advanced Neuromodulation Systems, Inc.; Best Practice Project Management, Inc.; Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; Cyberonics, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Gerson Lehman Group; GlaxoSmithKline; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Eli Lilly & Company; Merck & Co., Inc.; Neuronetics; Ono Pharmaceutical; Organon USA Inc.; Personality Disorder Research Corp.; Pfizer Inc.; The Urban Institute; and Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories Inc. He has received royalties from Guilford Press and Healthcare Technology Systems and research/grant support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Stanley Foundation; has been on speaker bureaus for Cyberonics, Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, and Eli Lilly & Company; and owns stock in Pfizer Inc. Dr Trivedi has received research support from Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Corcept Therapeutics, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Eli Lilly & Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Pharmaceutica; Merck; National Institute of Mental Health; National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression; Novartis; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia & Upjohn; Predix Pharmaceuticals; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories. He has served on Advisory Boards for or provided consultation to Abbott Laboratories, Inc.; Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc.); Bayer; Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP; Johnson & Johnson PRD; Eli Lilly & Company; Meade Johnson; Parke‐Davis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Pharmacia & Upjohn; Sepracor; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories and has been on speaker's bureaus for Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc.); Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company; Cephalon, Inc.; Cyberonics, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals; Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP; Eli Lilly & Company; Pharmacia & Upjohn; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; and Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories. Dr. Warden currently owns stock in Pfizer and previously owned stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr Wisniewski has served as a consultant for Cyberonics Inc. (2005‐2005) and ImaRx Therapeutics, Inc. (2006). The remaining authors report no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) under contract N01MH90003 to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (A.J. Rush, principal investigator). The NIMH had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. Also, we thank Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, King Pharmaceuticals, Organon, Pfizer, and Wyeth for providing medications at no cost for this trial. Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00021528

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Anna Brandon at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Ms Sara Mlynarchek at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health for input into this manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the editorial support of Mr Jon Kilner, MS, MA (Pittsburgh, PA).

Dr McClintock has received research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD). Dr Alpert has received research support from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Aspect Medical Systems, Astra‐Zeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly & Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithkline, J & J Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Organon Inc., PamLab, LLC, Pfizer Inc, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Wyeth‐Ayerst Laboratories. He has received speakers' honoraria from Eli Lilly & Company, Janssen, Organon. Dr Husain has received research support from the National Institute of Mental Health, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Cyberonics, Inc., Neuronetics, Inc., Magstim, and Advanced Neuromodulation Systems. Dr Kornstein has received research support from the Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Mental Health, Pfizer, Inc., Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, Lilly, Inc., Forest Laboratories, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Inc., Mitsubishi‐Tokyo, Merck, Inc., Biovail Laboratories, Inc., Wyeth, Inc., Berlex Laboratories, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sepracor, Inc., Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Sanofi‐Synthelabo, and Astra‐Zeneca.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, Text Revision), Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby R.M., Ryder A.G., Schuller D.R., Marshall M.B. (2004) The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the gold standard become a lead weight? American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 2163–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P. (1981) Rating scales for affective disorders: Their validity and consistency. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 64(Supplement 295), 11–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P. (2004) Modern psychometrics in clinimetrics: Impact on clinical trials of antidepressants. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 73, 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P. (2009) Fifty years with the Hamilton scales for anxiety and depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech P., Allerup P., Gram L.F., Reisby N., Rosenberg R. (1981) The Hamilton Depression Scale: Evaluation of objectivity using logistic models. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 63, 290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein I.H., Rush A.J., Carmody T.J., Woo A., Trivedi M.H. (2007) Clinical vs. self‐report versions of the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology in a public sector sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 41(3–4), 239–246, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein I.H., Rush A.J., Suppes T., Trivedi M.H., Woo A., Kyutoku Y., Crismon M.L., Dennehy E., Carmody T.J. (2009) A psychometric evaluation of the clinician‐rated Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS‐C16) in patients with bipolar disorder. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18(2), 138–146, DOI: 10.1002/mpr.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein I.H., Rush A.J., Thomas C.J., Woo A., Trivedi M.H. (2006) Item response analysis of the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2(4), 557–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramley P.N., Easton A.M., Morley S., Snaith R.P. (1988) The differentiation of anxiety and depression by rating scales. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 77(2), 133–138, DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel S., Rush B., Kennedy S., Fulton K., Toneatto T. (2007) Screening for mental health problems among patients with substance use disorders: Preliminary findings on the validation of a self‐assessment instrument. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary P., Guy W. (1977) Factor analysis of the Hamilton Depression Scale. Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research, 1, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy F.F., Chung H., Trivedi M., Rae D.S., Regier D.A., Katzelnick D.J. (2008) Systematic use of patient‐rated depression severity monitoring: Is it helpful and feasible in clinical psychiatry? Psychiatric Services, 59(10), 1148–1154, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.10.1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embretson S.E., Reise S. (2000) Item Response Theory for Psychologists, Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Emmelkamp P.M.G. (2004) The additional value of clinimetrics needs to be established rather than assumed. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 73, 142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M., Alpert J.E., Carmin C.N., Wisniewski S.R., Trivedi M.H., Biggs M.M., Shores‐Wilson K., Morgan D., Schwartz T., Balasubramani G.K., Rush A.J. (2004) Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR*D. Psychological Medicine, 34(7), 1299–1308, DOI: 10.1017/S0033291704002612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava G., Kellner R., Lisansky J., Park S., Perini G.I., Zielezny M. (1986) Rating depression in normals and depressives: Observer versus self‐rating scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 11, 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M., Rush A.J., Alpert J.E., Balasubramani G.K., Wisniewski S.R., Carmin C.N., Biggs M.M., Zisook S., Leuchter A., Howland R., Warden D., Trivedi M.H. (2008) Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 342–351, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M., Rush A.J., Trivedi M.H., Nierenberg A.A., Thase M.E., Sackeim H.A., Quitkin F.M., Wisniewski S., Lavori P.W., Rosenbaum J.F., Kupfer D.J. (2003) Background and rationale for the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 26(2), 457–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M., Uebelacker L.A., Alpert J.E., Nierenberg A.A., Pava J.A., Rosenbaum J.F. (1997) Major depressive subtypes and treatment response. Biological Psychiatry, 42, 568–576, DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00440-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M.B., Spitzer R.L., Gibbon M., Williams J.B.W. (1997) User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV Axis I Disorders: SCID‐1 Clinician Version, Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck M.P., Poirier‐Littre M.F., Guelfi J.D., Bourdel M.C., Loo H. (1995) Factorial structure of the 17‐item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 92(3), 168–172, DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons R.D., Rush A.J., Immekus J.C. (2009) On the psychometric validity of the domains of the PDSQ: An illustration of the bi‐factor item response theory model. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43, 401–410, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibody S., House A., Sheldon T. (2002) Psychiatrists in the UK do not use outcome measures. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 101–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullion C.M., Rush A.J. (1998) Toward a generalizable model of symptoms in major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 44(10), 959–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1959) The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 32, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1960) A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 23, 56–62, DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. (1967) Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 6(4), 278–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn J.L. (1965) An empirical comparison of various methods for estimating common factor scores. Education and Psychological Measures, 25, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys L.G., Ilgen D. (1969) Note on a criterion for the number of common factors. Education and Psychological Measures, 29, 571–580. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys L.G., Montanelli R.G. (1975) An investigation of the parallel analysis criterion for determining the number of common factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 10, 193–205, DOI: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1002_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Koretz D., Merikangas K.R., Rush A.J., Walters E.E., Wang P.S., National Comorbidity Survey Replication . (2003) The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS‐R). JAMA, 289, 3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Nelson C.B., McGonagle K.A., Liu J., Swartz M., Blazer D.G. (1996) Comorbidity of DSM‐III‐R major depressive disorder in the general population: Results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry, 30(Suppl.), 17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugharne R. (2009) Quality standards for community mental health teams. The Psychiatrist, 33, 387–389. [Google Scholar]

- Loong T.W. (2003) Understanding sensitivity and specificity with the right side of the brain. British Journal of Psychiatry, 327(7417), 716–719, DOI: 10.1136/bmj.327.7417.716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord F.M. (1980) Applications of Item Response Theory for Practical Testing Problems, Hillsdale, NJ, LEA. [Google Scholar]

- Lydiard R.B., Brawman‐Mintzer O. (1998) Anxious depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Supplement 18), 10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M.T., Michaud C.M., Murray C.J., Marks J.S. (2005) Assessing the burden of disease in the United States using disability‐adjusted life years. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28, 415–423, DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanelli R.G., Humphreys L.G. (1976) Latent roots of random data correlation matrices with squared multiple correlations on the diagonal: A Monte Carlo study. Psychometrika, 41, 341–380, DOI: 10.1007/BF02293559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S., Chatterji S., Verdes E., Tandon A., Patel V., Ustun B. (2007) Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: Results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet, 370, 851–858, DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J., Lopez A.D. (1996) Evidenced‐based health policy‐Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science, 274, 740–743, DOI: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J.C., Bernstein I.H. (1994) Psychometric Theory, New York, McGraw‐Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M., Sherbourne C.D., Thissen D. (2000) Summed‐score linking using item response theory: Application to depression measurement. Psychological Assessment, 12, 354–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pancheri P., Picardi A., Pasquini M., Gaetano P., Biondi M. (2002) Psychopathological dimensions of depression: A factor study of the 17‐item Hamilton depression rating scale in unipolar depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 68(1), 41–47, DOI: 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00328-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusoff B.A., Klerman G.L., Paykel E.S. (1972) Concordance between clinical assessments and patients' self‐report in depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 26, 546–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Bernstein I.H., Trivedi M.H., Carmody T.J., Wisniewski S., Mundt J.C., Shores‐Wilson K., Biggs M.M., Woo A., Nierenberg A.A., Fava M. (2006a) An evaluation of the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology and the Hamilton rating scale for depression: A sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression trial report. Biological Psychiatry, 59(6), 493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Fava M., Wisniewski S.R., Lavori P.W., Trivedi M.H., Sackeim H.A., Thase M.E., Nierenberg A.A., Quitkin F.M., Kashner T.M., Kupfer D.J., Rosenbaum J.F., Alpert J., Stewart J.W., McGrath P.J., Biggs M.M., Shores‐Wilson K., Lebowitz B.D., Ritz L., Niederehe G., STAR*D Investigators Group . (2004) Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): Rationale and design. Controlled Clinical Trials, 25(1), 119–142, DOI: 10.1016/S0197-2456(03)00112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Giles D.E., Schlesser M.A., Fulton C.L., Weissenburger J., Burns C. (1986) The Inventory for Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Preliminary findings. Psychiatry Research, 18(1), 65–87, DOI: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90060-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Gullion C.M., Basco M.R., Jarrett R.B., Trivedi M.H. (1996) The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): Psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine, 26(3), 477–486, DOI: 10.1017/S0033291700035558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Trivedi M.H., Wisniewski S.R., Stewart J.W., Nierenberg A.A., Thase M.E., Ritz L., Biggs M.M., Warden D., Luther J.F., Shores‐Wilson K., Niederehe G., Fava M. (2006b) Bupropion‐SR, Sertraline, or Venlafaxine‐XR after Failure of SSRIs for Depression. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(12), 1231–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Warden D., Wisniewski S.R., Fava M., Trivedi M.H., Gaynes B.N., Nierenberg A.A. (2009) STAR*D: Revising conventional wisdom. CNS Drugs, 23(8), 627–647, DOI: 10.2165/00023210-200923080-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush A.J., Zimmerman M., Wisniewski S.R., Fava M., Hollon S.D., Warden D., Biggs M.M., Shores‐Wilson K., Shelton R.C., Luther J.F., Thomas B., Trivedi M.H. (2005) Comorbid psychiatric disorders in depressed outpatients: Demographic and clinical features. Journal of Affective Disorders, 87(1), 43–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samejima F. (1997) Graded response model In Handbook of Modern Item Response Theory, van Linden W., Hambleton R.K. (eds) pp. 85–100, New York, Springer‐Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavis J., Weiller E., Hergueta T., Baker R., Dunbar G.C. (1998) The Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM‐IV and ICD‐10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Supplement 20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirri L., Grandi S., Fava G.A. (2008) The Illness Attitude Scales: A clinimetric index for assessing hypochondriacal fears and beliefs. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 77, 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D. (2005) State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults, Redwood City, CA, Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi M.H., Daly E.J. (2007) Measurement‐based care for refractory depression: A clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(Supplement 2), S61–S71, DOI: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi M.H., Rush A.J., Ibrahim H.M., Carmody T.J., Biggs M.M., Suppes T., Crismon M.L., Shores‐Wilson K., Toprac M.G., Dennehy E.B., Witte B., Kashner T.M. (2004) The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (IDS‐C) and Self‐Report (IDS‐SR), and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating (QIDS‐C) and Self‐Report (QIDS‐SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine, 34(1), 73–82, DOI: 10.1017/S0033291703001107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau . (2000) Census 2000 PHC‐T‐1. Population by Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin for the United States: 1990 and 2000 [updated July 18, 2006; cited July 18, 2006]. http://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/phc-t1/tab01.pdf [25 August 2008].

- Zimmerman M., Chelminski I. (2006) Screening for anxiety disorders in depressed patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(3), 267–272, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., Chelminski I., Young D., Dalrymple K. (2010) A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(5), 534–542. DOI: 10.4088/JCP.09m05264blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., Mattia J.I. (1999) The reliability and validity of a screening questionnaire for 13 DSM‐IV Axis I disorders (the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire) in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60(10), 677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., Mattia J.I. (2001) A self‐report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(8), 787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., McGlinchey J.B. (2008) Why don't psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 1916–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]