Abstract

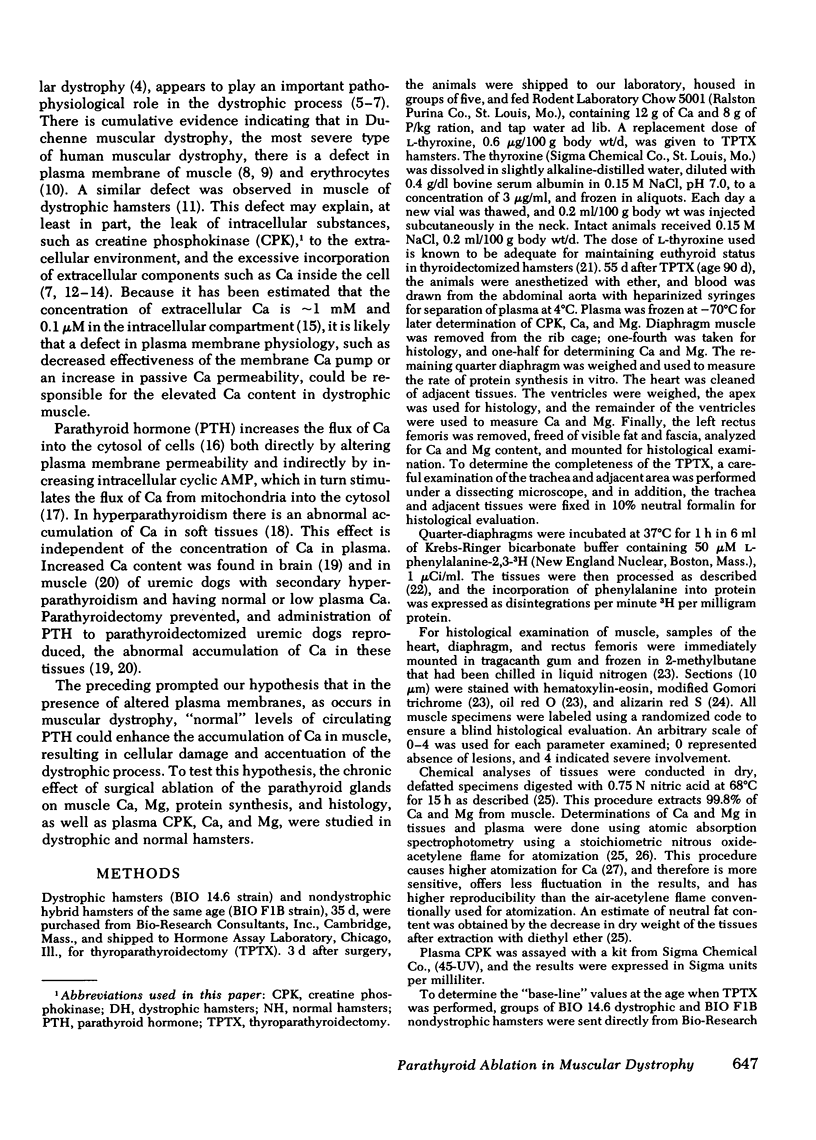

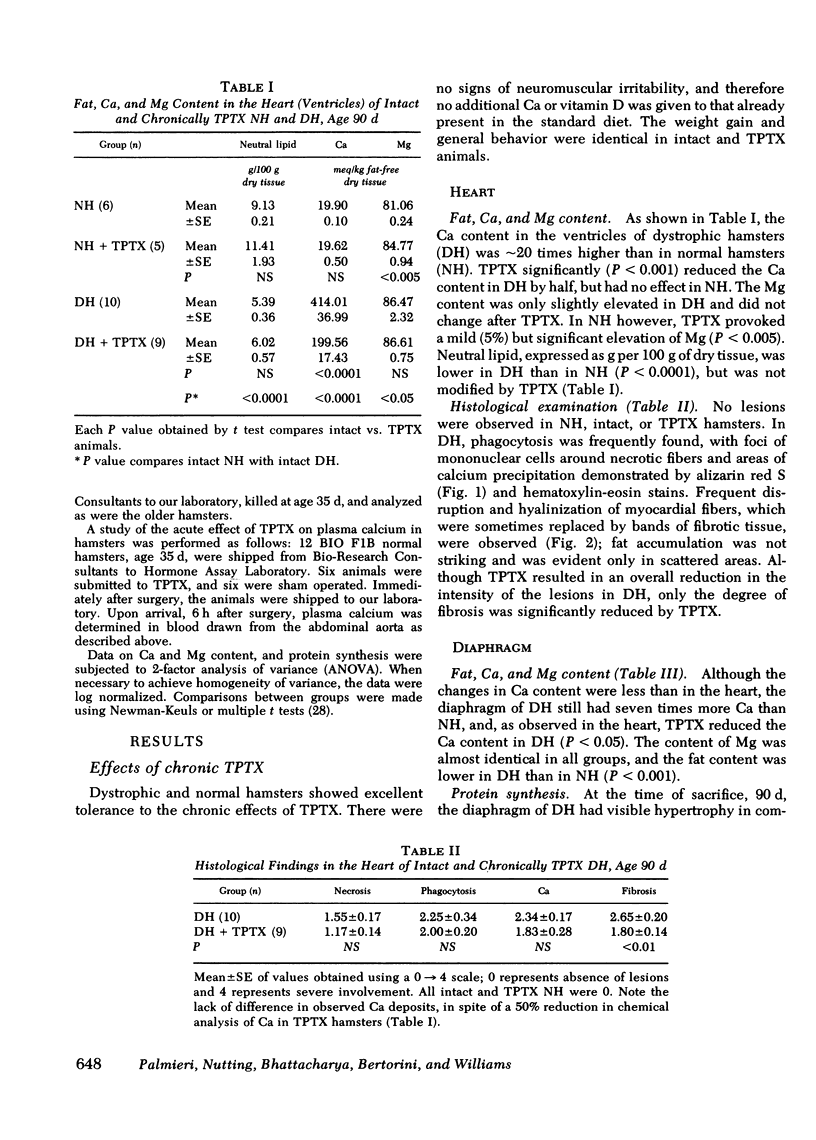

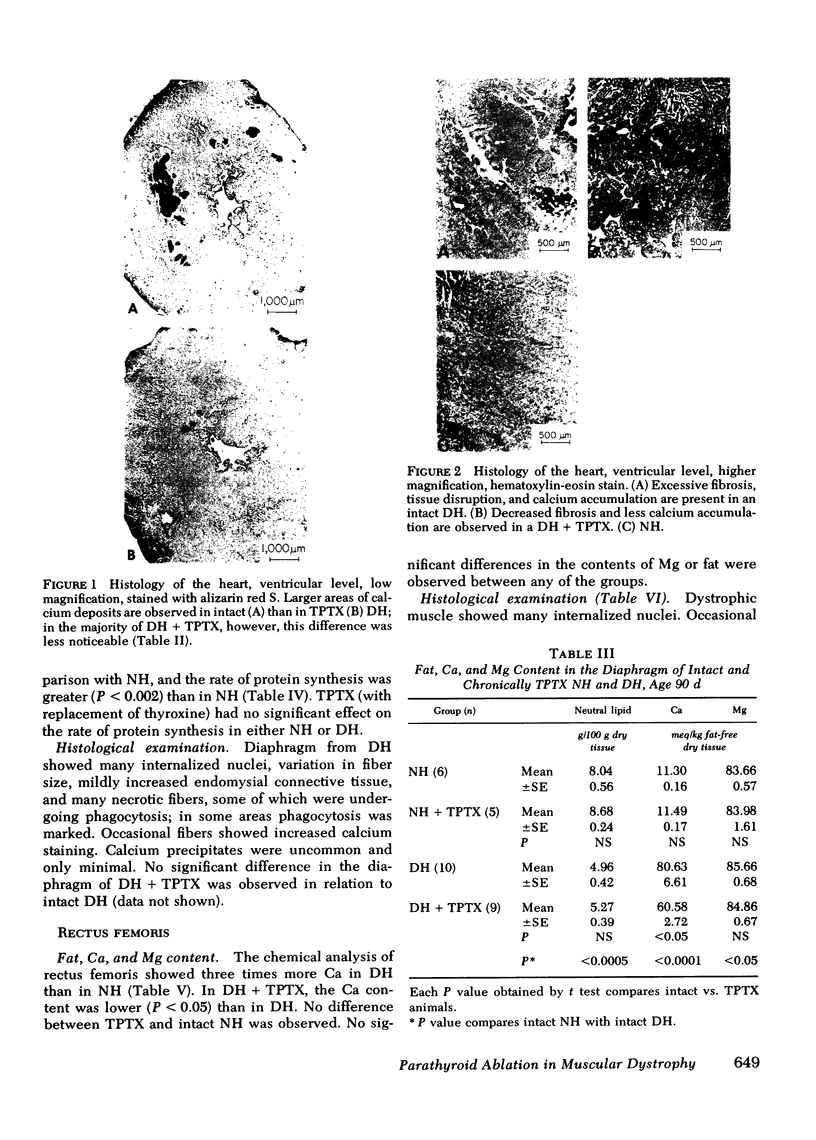

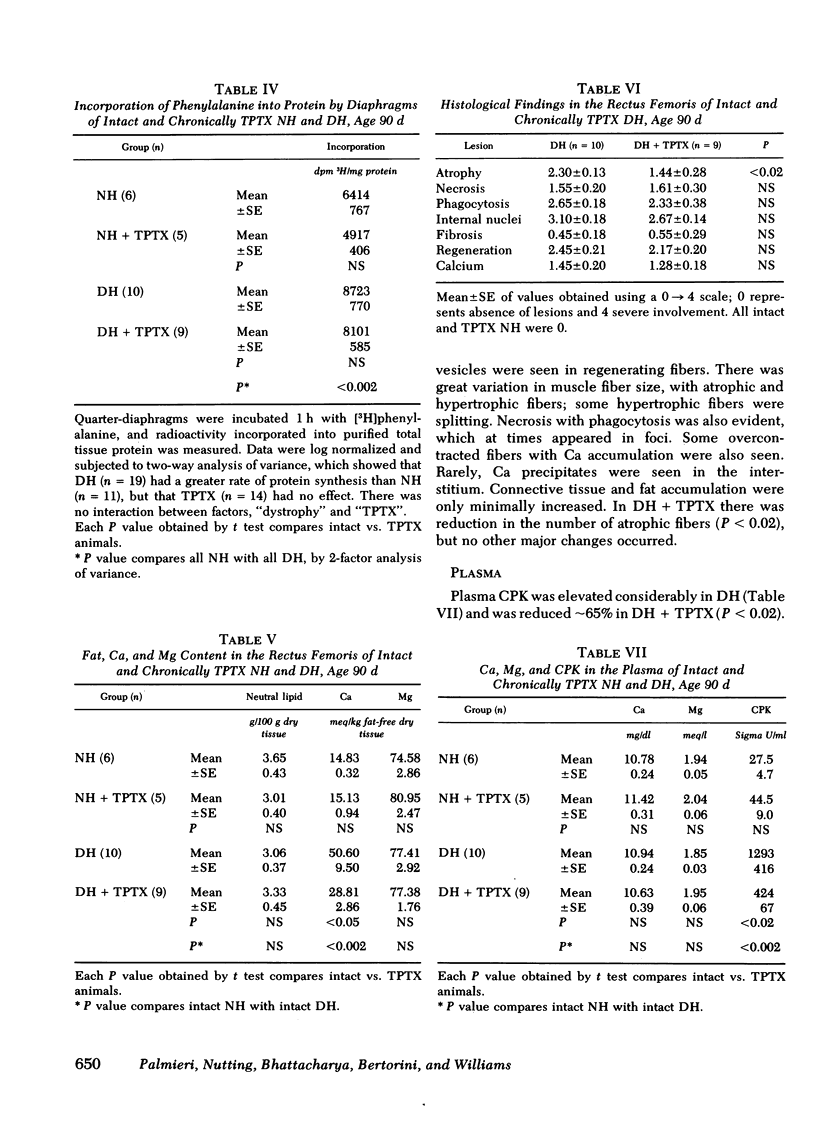

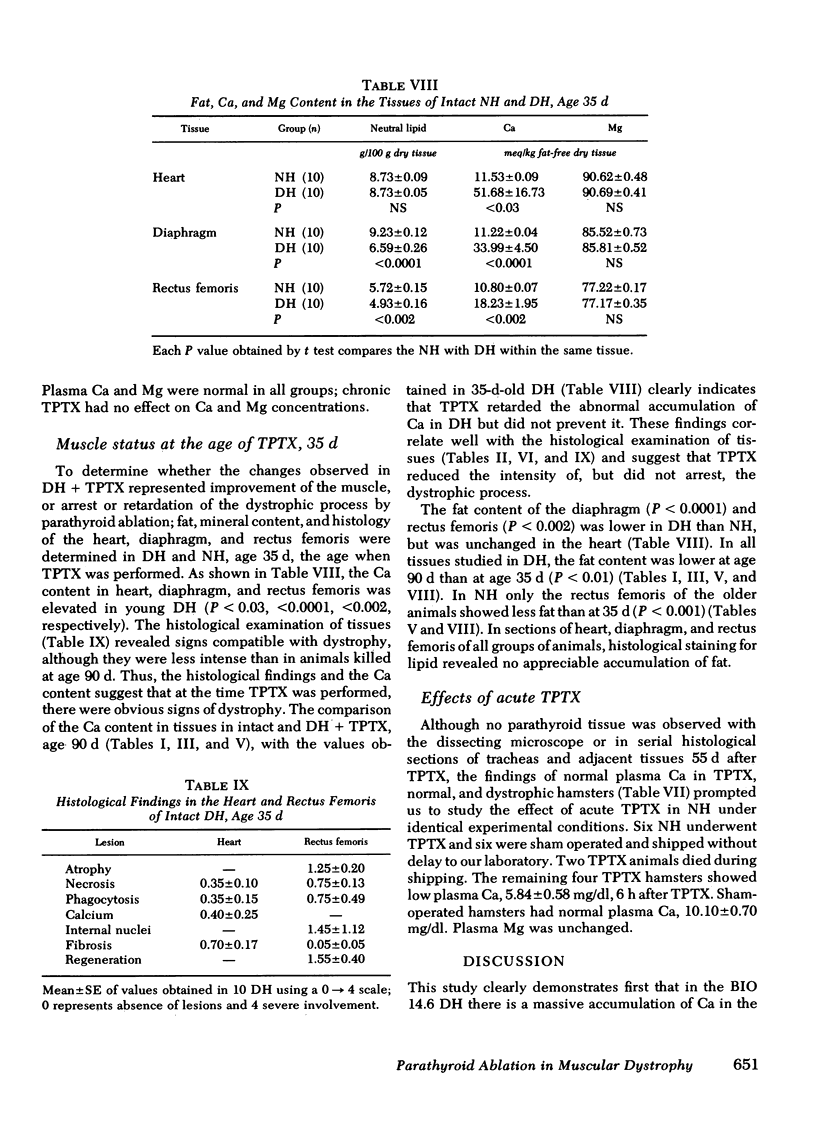

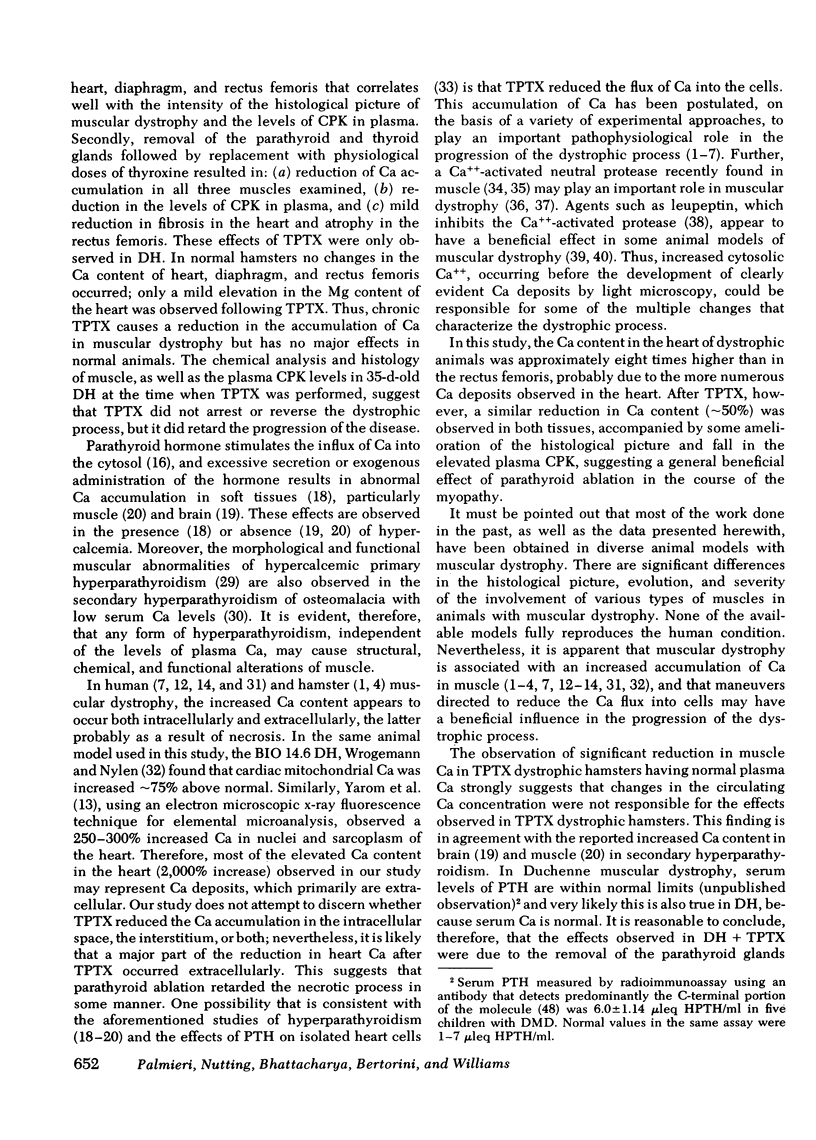

Cumulative evidence indicates that there is an increased accumulation of calcium in dystrophic muscle and that this may have a pathophysiological role in the progression of the dystrophic process. The accumulation may be related to a defect of the plasma membrane. Because parathyroid hormone (PTH) stimulates calcium influx into the cytosol, the chronic effects of surgical ablation of the parathyroid glands on muscle Ca, Mg, protein synthesis, and histology, as well as plasma creatine phosphokinase (CPK), Ca, and Mg, were studied in normal and dystrophic (BIO 14.6) hamsters. Thyroparathyroidectomized (TPTX) hamsters receiving replacement doses of l-thyroxine were killed at age 90 d, 55 d after TPTX. In intact dystrophic hamsters, the Ca content in the heart was 20 times higher than in normal animals and was reduced by half in TPTX dystrophic hamsters. Similar results were observed in diaphragm and rectus femoris. No abnormalities in Mg content were observed in intact or TPTX dystrophic hamsters. Ether-extractable fat of the heart and diaphragm was reduced in dystrophic hamsters and was not modified by TPTX. Protein synthesis was enhanced in the diaphragm of dystrophic hamsters but was not changed by TPTX. The concentration of CPK in plasma was elevated in dystrophic hamsters and fell significantly after TPTX. In the latter animals, microscopic examination of the heart showed lesser signs of dystrophy, particularly in the degree of fibrosis.

To determine the degree of dystrophy at the age when TPTX was performed, identical analyses were made in 35-d-old hamsters. Definitive histological signs of dystrophy were observed, and although the Ca content in heart, diaphragm, and rectus femoris was elevated, the values were lower than in 90-d-old intact and TPTX dystrophic hamsters. This indicates that chronic TPTX in dystrophic hamsters reduces, but does not arrest, the dystrophic process.

In normal hamsters, a 50% reduction in plasma Ca concentration was observed 6 h after TPTX; 55 d after TPTX, however, plasma Ca was within normal limits in both normal and dystrophic hamsters. No parathyroid tissue was observed in serial sections of the trachea and adjacent tissues in TPTX animals. This suggests that in chronically TPTX hamsters fed a standard laboratory diet, plasma Ca can be maintained by mechanisms independent of parathyroid function.

The data indicate that in dystrophic hamsters TPTX causes a marked reduction in: (a) muscle Ca accumulation, (b) levels of plasma CPK and, (c) intensity of histological changes in the heart. These changes were independent of the levels of plasma Ca and were not observed in normal hamsters. We conclude that PTH accentuates the dystrophic process, probably by enhancing the already increased Ca flux into muscle (apparently caused by defective sarcolemma). We postulate that normal secretion of PTH may have a deleterious effect in congenital or acquired conditions associated with altered plasma membranes.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Araki S., Mawatari S. Ouabain and erythrocyte-ghost adenosine triphosphatase. Effects in human muscular dystrophies. Arch Neurol. 1971 Feb;24(2):187–190. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1971.00480320115012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieff A. I., Massry S. G. Calcium metabolism of brain in acute renal failure. Effects of uremia, hemodialysis, and parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1974 Feb;53(2):387–392. doi: 10.1172/JCI107571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajusz E. Hereditary cardiomyopathy: a new disease model. Am Heart J. 1969 May;77(5):686–696. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat H. A., Dohm G. L., Loesche P., Tapscott E. B., Smith C. Lipid content and fatty acid composition of heart and muscle of the BIO 82.62 cardiomyopathic hamster. Lipids. 1976 Oct;11(10):747–751. doi: 10.1007/BF02533049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkow J. W., Fine B. S., Zimmerman L. E. Unusual ocular calcification in hyperparathyroidism. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968 Nov;66(5):812–824. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(68)92795-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson S. A., Yalow R. S., Aurbach G. D., Potts J. T. IMMUNOASSAY OF BOVINE AND HUMAN PARATHYROID HORMONE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1963 May;49(5):613–617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.49.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodensteiner J. B., Engel A. G. Intracellular calcium accumulation in Duchenne dystrophy and other myopathies: a study of 567,000 muscle fibers in 114 biopsies. Neurology. 1978 May;28(5):439–446. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogin E., Massry S. G., Harary I. Effect of parathyroid hormone on rat heart cells. J Clin Invest. 1981 Apr;67(4):1215–1227. doi: 10.1172/JCI110137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle A. B. Membrane transfer of calcium. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967 May-Jun;52:267–291. doi: 10.1097/00003086-196700520-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle A. B. Regulation of cellular calcium metabolism and calcium transport by calcitonin. J Membr Biol. 1975 Apr 23;21(1-2):125–146. doi: 10.1007/BF01941066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton W. R., Goll D. E., Zeece M. G., Robson R. M., Reville W. J. A Ca2+-activated protease possibly involved in myofibrillar protein turnover. Purification from porcine muscle. Biochemistry. 1976 May 18;15(10):2150–2158. doi: 10.1021/bi00655a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton W. R., Reville W. J., Goll D. E., Stromer M. H. A Ca2+-activated protease possibly involved in myofibrillar protein turnover. Partial characterization of the purified enzyme. Biochemistry. 1976 May 18;15(10):2159–2167. doi: 10.1021/bi00655a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin K. O., Edwardly J., Fuss C. N. Retention of 45Ca in rats and lambs associated with the onset of nutritional muscular dystrophy. Aust J Biol Sci. 1975 Dec;28(5-6):457–464. doi: 10.1071/bi9750457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldspink D. F., Goldspink G. Age-related changes in protein turnover and ribonucleic acid of the diaphragm muscle of normal and dystrophic hamsters. Biochem J. 1977 Jan 15;162(1):191–194. doi: 10.1042/bj1620191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisado R., Arieff A. I., Massry S. Muscle water and electrolytes in uremia and the effects of hemodialysis. J Lab Clin Med. 1977 Feb;89(2):322–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiura S., Murofushi H., Suzuki K., Imahori K. Studies of a calcium-activated neutral protease from chicken skeletal muscle. I. Purification and characterization. J Biochem. 1978 Jul;84(1):225–230. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar N. C., Pearson C. M. A calcium-activated neutral protease in normal and dystrophic human muscle. Clin Chim Acta. 1976 Dec 1;73(2):293–297. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(76)90175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox F. G., Preiss J., Kim J. K., Dousa T. P. Mechanism of resistance to the phosphaturic effect of the parathyroid hormone in the hamster. J Clin Invest. 1977 Apr;59(4):675–683. doi: 10.1172/JCI108686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossnitzer K., Janke J., Hein B., Stauch M., Fleckenstein A. Disturbed myocardial calcium metabolism: a possible pathogenetic factor in the hereditary cardiomyopathy of the Syrian hamster. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab. 1975;6:207–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallette L. E., Patten B. M., Engel W. K. Neuromuscular disease in secondary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1975 Apr;82(4):474–483. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-4-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder-Sewry C. A., Gorodetsky R., Yarom R., Dubowitz V. Element analysis of skeletal muscle in Duchenne muscular dystrophy using x-ray fluorescence spectrometry. Muscle Nerve. 1980 Nov-Dec;3(6):502–508. doi: 10.1002/mus.880030607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell J. R., Higgins R., Sahenk Z., Cosmos E. Relevance of genetic animal models of muscular dystrophy to human muscular dystrophies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1979;317:409–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokri B., Engel A. G. Duchenne dystrophy: electron microscopic findings pointing to a basic or early abnormality in the plasma membrane of the muscle fiber. Neurology. 1975 Dec;25(12):1111–1120. doi: 10.1212/wnl.25.12.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molak V., Stracher A., Erlij D. Dystrophic mouse muscles have leaky cell membranes. Exp Neurol. 1980 Nov;70(2):452–457. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(80)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neerunjun J. S., Dubowitz V. Increased calcium-activated neutral protease activity in muscles of dystrophic hamsters and mice. J Neurol Sci. 1979 Feb;40(2-3):105–111. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(79)90196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutting D. F. Ontogeny of sensitivity to growth hormone in rat diaphragm muscle. Endocrinology. 1976 May;98(5):1273–1283. doi: 10.1210/endo-98-5-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLDFIELD J. E., ELLIS W. W., MUTH O. H. White muscle disease (myopathy) in lambs and calves. III. Experimental production in calves from cows fed alfalfa hay. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1958 Mar 1;132(5):211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberc M. A., Engel W. K. Ultrastructural localization of calcium in normal and abnormal skeletal muscle. Lab Invest. 1977 Jun;36(6):566–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten B. M., Bilezikian J. P., Mallette L. E., Prince A., Engel W. K., Aurbach G. D. Neuromuscular disease in primary hyperparathyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 1974 Feb;80(2):182–193. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-2-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer M., Rosbash M., Huang A. S., Baltimore D. Complementarity between messenger RNA and nuclear RNA from HeLa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972 Oct 6;49(1):217–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracher A., McGowan E. B., Shafiq S. A. Muscular dystrophy: inhibition of degeneration in vivo with protease inhibitors. Science. 1978 Apr 7;200(4337):50–51. doi: 10.1126/science.635570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrogemann K., Jacobson B. E., Blanchaer M. C. On the mechanism of a calcium-associated defect of oxidative phosphorylation in progessive muscular dystrophy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1973 Nov;159(1):267–278. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(73)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrogemann K., Nylen E. G. Mitochondrial calcium overloading in cardiomyopathic hamsters. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1978 Feb;10(2):185–195. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(78)90042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrogemann K., Pena S. D. Mitochondrial calcium overload: A general mechanism for cell-necrosis in muscle diseases. Lancet. 1976 Mar 27;1(7961):672–674. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92781-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarom R., Friedman I., Hall T. A. Calcium and chloride content in myocardium-trapped erythrocytes of cardiomyopathic hamsters. Isr J Med Sci. 1977 Dec;13(12):1222–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]