Abstract

Members of the Rab or ARF/Sar branches of the Ras GTPase super-family regulate almost every step of intracellular membrane traffic. A rapidly growing body of evidence indicates that these GTPases do not act as lone agents but are networked to one another through a variety of mechanisms to coordinate the individual events of one stage of transport and to link together the different stages of an entire transport pathway. These mechanisms include guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) cascades, GTPase-activating protein (GAP) cascades, effectors that bind to multiple GTPases, and positive-feedback loops generated by exchange factor-effector interactions. Together these mechanisms can lead to an ordered series of transitions from one GTPase to the next. As each GTPase recruits a unique set of effectors, these transitions help to define changes in the functionality of the membrane compartments with which they are associated.

Keywords: Rab, ARF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor, GTPase-activating protein, effector, vesicular transport

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic cells contain a variety of membrane-bounded organelles, each with its own specific set of resident components that confer to these organelles their unique functions. Organelles of the exocytic and endocytic pathways, including the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, plasma membrane, endosomes, and lysosomes are linked by rapid, bidirectional membrane traffic, primarily mediated by vesicular transport. One of the major challenges facing the membrane traffic field has been to understand how the unique composition of each organelle is maintained despite this high level of interorganelle traffic. Tightly controlled selection of cargo from the donor compartment during vesicle formation and faithful targeting of vesicles to the appropriate recipient compartment prior to fusion are essential to avoid the rapid dispersal and homogenization of all resident components among the interconnected organelles. GTPases from several branches of the Ras superfamily play essential roles in regulating these steps. However, these GTPases must themselves be regulated both spatially and temporally to maintain the orderly transport of cargo through a series of compartments. Over the past decade, evidence has mounted that these GTPases do not act as independent agents but rather are networked to one another by several different mechanisms, both to coordinate the various biochemical steps of each individual stage of membrane traffic and to link together the different stages of an entire transport pathway. In this review, we discuss specific examples ofGTPase networks in the regulation of membrane traffic. Although it is still too early to make broad generalizations regarding the mechanisms by which GTPases are networked, these examples offer some paradigms that may help speed the analysis of other stages of membrane traffic in diverse organisms.

The Ras GTPase superfamily includes several major branches that are primarily dedicated to the regulation of membrane traffic. The Arf/Sar branch is best known for the roles that its members play in the regulation of vesicle budding from donor compartments. Sar helps coordinate cargo selection and budding of coat protein II (COPII)-coated vesicles from ER exit sites (1), whereas Arf proteins play analogous roles in the budding of clathrin-coated and COPI-coated vesicles at the Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane. The Rab branch typically controls subsequent events, such as the active transport of vesicles along cytoskeletal elements, the initial recognition and tethering of vesicles to the target compartment, and the regulation of vesicle fusion with the acceptor compartment. Members of other branches of the Ras superfamily, including Rho and Ral, have important, but more specialized roles in membrane traffic.

Overview of the GTPase Cycle

All members of the Ras superfamily function as nucleotide-dependent switches. They exhibit high affinity for both GDP and GTP, and assume different conformations in two so-called switch regions, depending upon the nucleotide bound. On their own, these proteins can only slowly interconvert from one form to the other owing to low intrinsic rates of GDP dissociation and GTP hydrolysis. The switch mechanism is therefore controlled by accessory proteins: guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) catalyze the displacement of prebound GDP, allowing its replacement with GTP, while GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) greatly stimulate the slow intrinsic hydrolysis of GTP to GDP. The nucleotide-binding and hydrolysis cycles of both Arf/Sar and Rab proteins are coupled to cycles of membrane association and dissociation. In the case of Rab proteins, a protein termed Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor (Rab GDI) binds specifically to the GDP-bound form, masking the C-terminal prenyl lipid moieties and thereby extracting the inactive Rab from the membrane (2). Arf and Sar members are released from membranes following GTP hydrolysis by changing conformation in such a way that they mask their own N-terminal membrane-binding domains, without the involvement of a GDI protein (3, 4). Because the nucleotide cycle is coupled to membrane attachment and release, the localization of the GEFs and GAPs can help define the localization of the active form of the regulated GTPase.

In their GTP-bound form, members of the Ras superfamily bind to a specific set of effectors. These interactions recruit the effectors to their site of action and can directly stimulate their activity or promote their assembly into protein complexes. Arf and Sar effectors include the coat proteins needed for cargo selection and vesicle budding (5). Rab effectors represent a very diverse collection of proteins, including motors needed to transport vesicles on the cytoskeleton, tethers that direct the initial recognition of the target compartment, and regulators of SNARE complex assembly (6). By recruiting a new set of effectors, a GTPase can help to change the functional identity of the membrane with which it is associated. Understanding how GTPase activation and inactivation are spatially and temporally controlled is critical toward understanding the mechanism of membrane traffic.

GTPases in Membrane Traffic

The number of GTPases involved in membrane traffic varies over a large range from species to species. For example, yeast express only 10 Rab proteins, whereas humans express more than 60 (7). Much of the expansion appears to have arisen from gene duplication followed by specialization of function. In this way, one ancestral traffic pathway can be subdivided into multiple pathways under regulation by distinct Rabs. For the purposes of this review, we very briefly outline a basic cast of GTPases on the endocytic and exocytic pathways, with the recognition that many more are involved in many cell types (for more comprehensive reviews see References 8 and 9). Formation of the initial endocytic vesicles requires Arf6. Homotypic fusion of these vesicles and fusion to the early endosome require Rab5. Rapid recycling to the cell surface requires Rab4. Conversion of the early endosome to a late endosome requires Rab7. Transport from the endosome to the Golgi apparatus requires Rab9, and export of cargo from the recycling endosome back to the cell surface requires Rab11. On the exocytic pathway, the formation of vesicles from the ER requires Sar1. Fusion of those vesicles with the Golgi apparatus requires Rab1. Arf1 is needed to exit the Golgi apparatus, and Rab8 is needed for fusion of Golgi-derived vesicles with the plasma membrane. Rab6 controls retrograde transport within the Golgi apparatus. In the following sections, we review how some of these GTPases are linked to each other through coordinated regulation of exchange or hydrolysis and how some are linked to each other through a common effector.

GUANINE NUCLEOTIDE EXCHANGE FACTOR CASCADES

The cytoplasmic surface of every organelle of the endocytic and exocytic pathways is tagged with a specific set of Rab GTPases that play important roles in defining organelle function and identity. Typically, several Rab GTPases work cooperatively on the same traffic pathway and must be coordinately regulated to fulfill their functions in a sequential fashion. Rab activation requires a specific GEF; however, it is still unclear how these GEFs are regulated so that each Rab can be activated at the right time and place. One regulatory mechanism has been termed a Rab GEF cascade (Figure 1a). This mechanism was first documented through analysis of the yeast secretory pathway (10). Ypt31p and Ypt32p are closely related and redundant Rab11 homologs that localize to a late Golgi compartment. Active Ypt31p/Ypt32p recruit Sec2p, a GEF for the Rab GTPase Sec4p, which acts just downstream of Ypt31p/Ypt32p on Golgi-derived secretory vesicles (Figure 1b) (11, 12). Thus, two different Rabs are functionally linked in a regulatory cascade through a GEF. Subsequent studies have revealed the existence of several such cascades in both yeast and mammalian cells and at additional stages of membrane traffic, suggesting that the Rab GEF cascade is a common, conserved regulatory mechanism. In this article, we discuss various Rab GEF cascades.

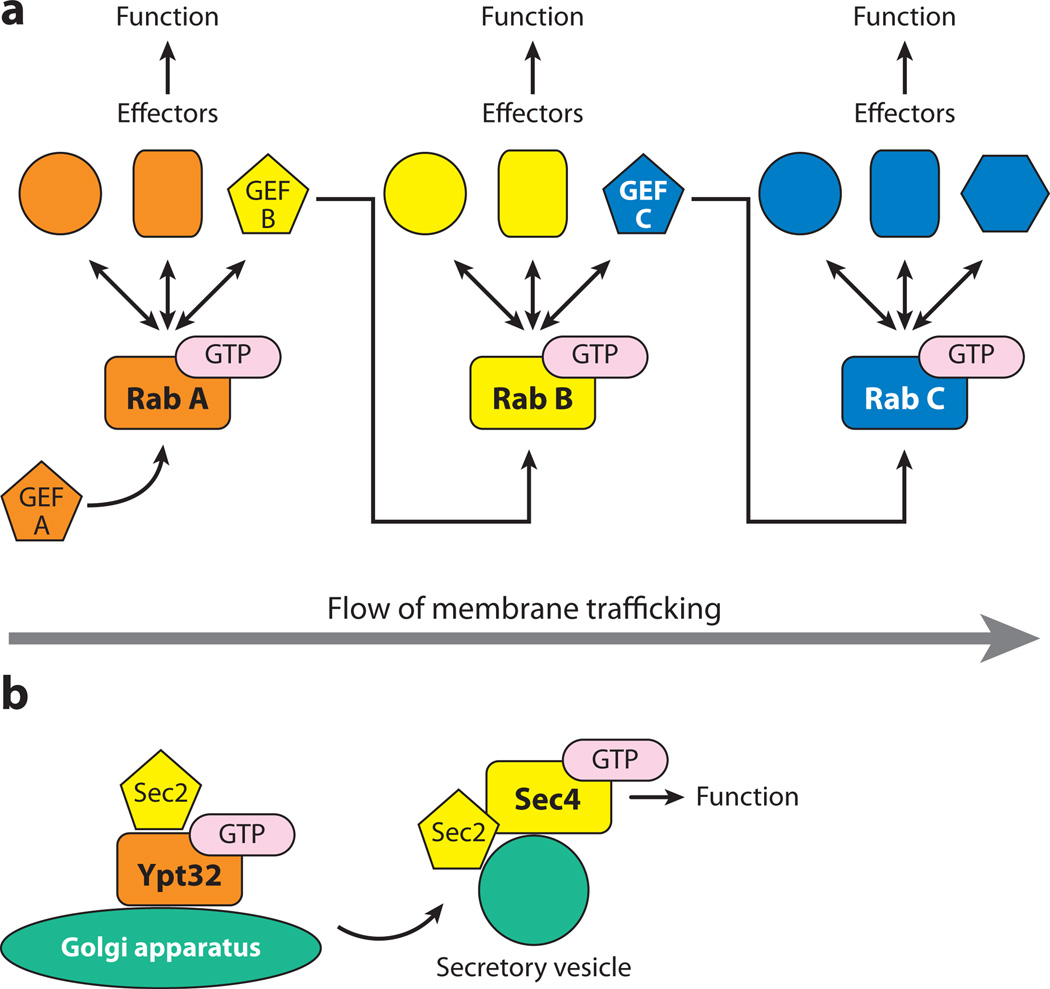

Figure 1.

Rab-guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) cascade. (a) A Rab GTPase is activated by its own GEF. The GTP-bound active form recruits several effectors to the organelle membrane to fulfill their functions. One of the effectors is a GEF for the downstream Rab: Active Rab A recruits GEF B for the downstream Rab B (left). GEF B activates Rab B, and then active Rab B recruits effectors, including GEF C for the downstream Rab C (middle). Again, GEF C activates the downstream Rab C (right). Thus, several Rab GTPases in the pathway are sequentially recruited to the membrane and efficiently activated. (b) The first Rab GEF cascade was found in yeast. Golgi-localized GTP-bound Rab Ypt31p/Ypt32p interacts with Sec2p, a GEF for the next Rab Sec4p (10).

Rab/Ypt Cascades in Endosomal Traffic

Rab5-HOPS-Rab7 cascade on endosome

Rab5 plays a key role in the early endocytic pathway (Figure 2). Rab5 has various functions: cargo sequestration and budding of endocytic vesicles from the plasma membrane, uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles, vesicle motility along microtubules, tethering of vesicles to acceptor membranes, and membrane fusion (13–17). After recruitment of Rab5 to the endosomalmembrane, Rab5must be activated by its nucleotide exchange factor, Rabex-5, to fulfill its functions. Active Rab5 binds various effectors, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase, hVps34, leading to the local production of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, together with Rab5-GTP, then recruits early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) to promote endosome fusion.

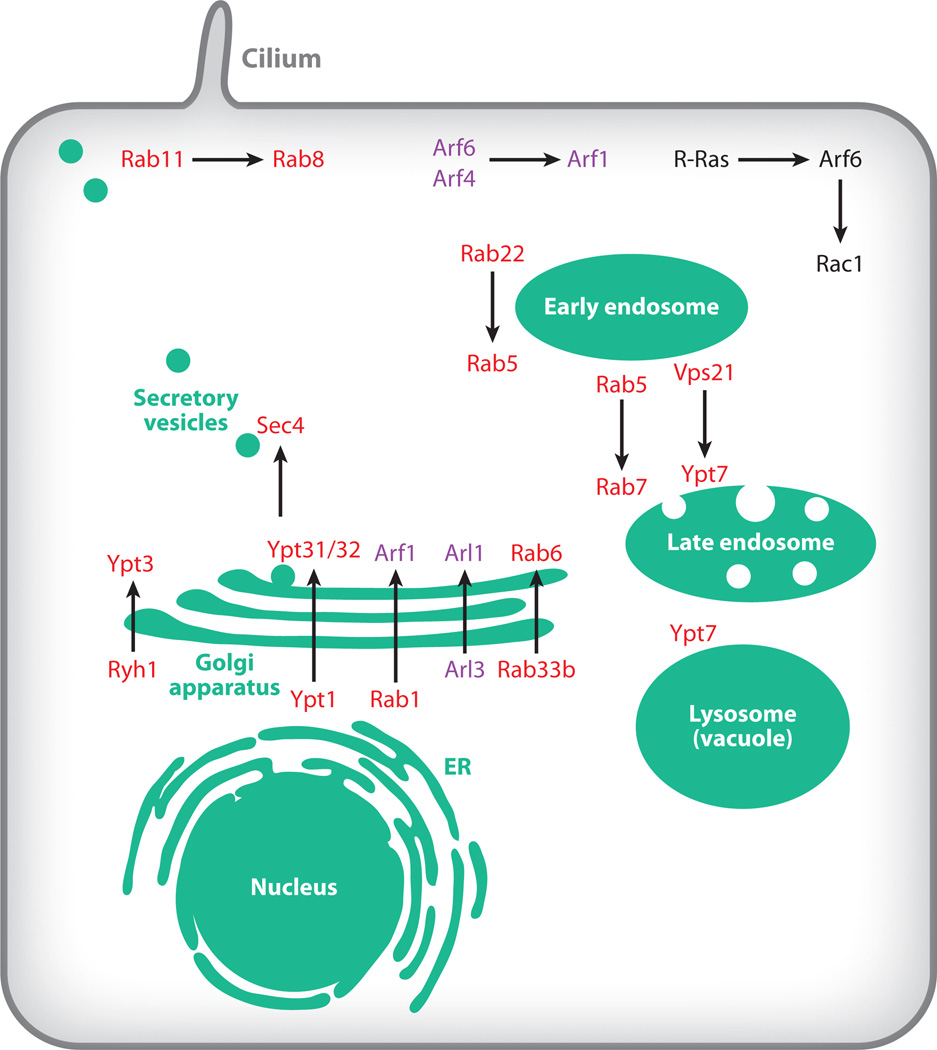

Figure 2.

Cellular localization of GTPase cascades in an epithelial cell. On endosomes, the Rab5-to-Rab7 transition is mediated by the Rab7 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), SAND1/Mon1-Ccz1 complex, to promote the endocytic pathway (24). The Vps21p-Ypt7p transition (yeast orthologs of Rab5 and Rab7) is also mediated by the Mon1-Ccz1 complex (23). Rab22 and Rab5 also form a cascade on endosomes through the Rab5 GEF, Rabex-5, regulating endosome fusion (28). In the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-Golgi trafficking pathway, yeast Ypt1p (homologous to Rab1) and Ypt31p/Ypt32p (homologous to Rab11) work sequentially, probably through a Ypt32p GEF (37). Ypt32p interacts with Sec2p, a GEF for the next Rab, Sec4p (Rab8 homolog) (10). Sec2p activates Sec4p on the secretory vesicle, which leads to vesicle tethering and fusion with plasma membrane thorough recruitment of the exocyst complex (11). A mammalian Rab11-Rab8 cascade is mediated by Rabin8, a GEF for Rab8; both Rab8 and Rabin8 are required for primary cilium formation (42, 43). A Rab33b-Rab6 cascade is proposed to work in the intra-Golgi apparatus retrograde trafficking (48). Fission yeast Ryh1p-Ypt3p (mammalian Rab6-Rab11) probably forms a cascade through the Ric1p/Rgp1p complex and works on the exocytic/recycling pathway (49). An Arl3-Arl1 cascade localizes to the Golgi apparatus, where it regulates protein sorting (58, 59). Rab1-Arf1 regulates coat protein I vesicle formation for ER-to-Golgi apparatus transport, which is mediated by GBF1, a Rab GEF for Arf1 (76). On the plasma membrane, Arl4 and Arf6 recruit Arno, a GEF for downstream GTPase Arf1, to regulate cytoskeletal organization and endocytosis (55–57). The R-Ras-Arf6-Rac1 pathway is required for cell spreading and migration, which is also mediated by Arno (83, 85, 86). Abbreviations: Arf1–Arf, Rab1–Rab33b, Rac1, members of the GTPase superfamily; R-Ras, a Ras-related protein.

Early endosomes contain not only Rab5, but also Rab4 and Rab11; however, each of these Rabs exhibits a distinct localization pattern, forming its own Rab-specific subdomains on early endosomal membranes. Similarly, late endosomes have both Rab7 and Rab9 subdomains (18). Fast live-cell imaging revealed that the Rab7 domain is derived from Rab5-positive endosomes (19) by the time-dependent disappearance of Rab5 and the acquisition of Rab7 on the same endosomes in human A431 cells (20). This Rab5-to-Rab7 transition was thought to be mediated by the class C vacuolar protein sorting (Vps)/homotypic fusion and vacuole protein sorting (HOPS) complex. The HOPS complex is highly conserved from yeast to human and serves as a tethering complex for vacuole homotypic fusion (21). Four of the six HOPS components bind to the GTP-bound form of Rab5, implying that HOPS is an effector of Rab5. Interestingly, one of the HOPS components, Vps39p, was claimed to have GEF activity toward Ypt7p, a yeast ortholog of Rab7 (21, 22). Thus, it appeared plausible that Rab5-GTP would recruit HOPS, thereby leading to activation of Rab7 and maturation of an early endosome into a late endosome. However, a recent study, discussed in the next section, revealed that the HOPS subunit Vps39p does not possess Rab7 GEF activity and that the Mon1p (monensin sensitivity 1)-Ccz1p (calcium caffeine zinc sensitivity) complex instead has this activity (23).

Rab5-SAND-1/Mon1-Rab7 cascade on endosomes

Poteryaev et al. (24) showed that Rab5-to-Rab7 conversion is also observed on endosomes in Caenorhabditis elegans, suggesting that Rab conversion is a general mechanism in metazoans. Importantly, SAND-1, an ortholog of yeast Mon1p, which was identified as an essential regulator of Rab7 function on endosomes, mediates this Rab transition (24, 25). SAND-1/Mon1 is recruited to the membrane by a direct interaction with Rabex-5, a GEF for Rab5, and phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Mon1 forms a stable complex with Ccz1 and works as a GEF for Rab7. SAND-1/Mon1 directly interacts with the HOPS complex and then recruits Rab7 through the HOPS complex. This observation again strongly suggests that SAND-1/Mon1 works as a switch for the Rab5-to-Rab7 transition to promote endosome maturation.

Rab22-Rabex-5-Rab5 cascade on endosomes

A new Rab GEF cascade was found to act at an earlier stage of the endosomal trafficking pathway. In mammalian cells, the Rab5 subfamily includes Rab5, Rab21, Rab22, and Rab31 (26, 27). The Rab5 GEF, Rabex-5, binds to Rab22-GTP yet does not exhibit GEF activity toward Rab22, indicating that Rabex-5 is a novel effector of Rab22. Rab22 recruits Rabex-5 to early endosomes, thus promoting Rab5 activation (28). In the absence of Rabex-5, Rab22 and Rab5 show only partial colocalization, whereas cells overexpressing both Rab22 and Rab5 exhibited enlarged endosomes, suggesting that these two Rab GTPases work cooperatively in the regulation of endosome fusion and the trafficking of epidermal growth factor receptors (28). A recent study demonstrated that RIN (Ras and Rab interactor) family protein Rin-like (Rinl) binds to the nucleotide-free form of Rab5a and Rab22, and Rinl has GEF activity toward both proteins, but it acts with higher efficiency on Rab22 (29). The functional relationship between Rin1 and Rabex-5 is not currently known. Rinl shows higher expression in thymus and spleen; thus, it might contribute to an additional level of regulation in those tissues.

Vps21p-CORVET-Mon1p/Ccz1p-Ypt7p cascade

Vps21p is a yeast ortholog of mammalian Rab5 (Figure 2) (30). Vps21p-GTP interacts with an endosomal tethering complex, CORVET (class C core vacuole/endosome tethering), which shares four of the six components of the HOPS complex, and thus, like HOPS, the CORVET complex is an effector of Vps21p (31). The CORVET complex can form an intermediate complex with a HOPS-specific subunit and then finally mature into the HOPS complex. The HOPS complex directly recruits Ypt7p and was believed to catalyze the Ypt7p nucleotide exchange reaction (22). However, the Mon1p-Ccz1p complex was recently shown to be the Ypt7p-specific GEF (23). Mon1p forms a stable complex with Ccz1p and shows GEF activity that is independent of the HOPS complex (23, 32, 33). Taken together, a molecular mechanism for the Rab conversion from Vps21p to Ypt7p can be proposed as follows: (a) active Vps21p recruits Mon1p-Ccz1p and the CORVET complex; (b) CORVET forms an intermediate complex, and Mon1p-Ccz1p directly associates with Vps39p, one of the components of the intermediate complex; (c) Mon1p-Ccz1p recruits and activates Ypt7p and (d) active Ypt7p triggers assembly of the final form of the HOPS complex needed for homotypic fusion of the vacuole.

Rab/Ypt Cascades in the Secretory Pathway

Ypt1p-Ypt32p cascade

A Rab GEF cascade mechanism is also utilized on the exocytic pathway. Ypt1p is a yeast ortholog of Rab1 that acts in the ER-to-Golgi and intra-Golgi trafficking (Figure 2) (34). Ypt1p is activated by a large protein complex, named TRAPP (transport protein particle) (35, 36). TRAPP has nucleotide exchange activity toward Ypt1p, but not Ypt31p or Ypt32p, Rab GTPases that act downstream of Ypt1p. Genetic experiments have suggested a functional relationship between Ypt1 and Ypt32. Overexpression of Ypt31p or Ypt32p suppresses the growth defect of cells expressing Ypt1p-D124N, an allele that is unable to bind guanine nucleotide or a temperature-sensitive TRAPP mutant in which Ypt1p activation is blocked. Wang & Ferro-Novick (37) showed that beads carrying Ypt1p loaded with the nonhydrolyzable GTP analog GTPγS could retain a factor from a yeast lysate that stimulated nucleotide exchange on Ypt32p, suggesting that the GEF for Ypt32p is an effector of Ypt1p. The identity of the GEF for Ypt31p and/or Ypt32p is still unclear; however, the results suggest that Ypt1p and Ypt32p are linked by a Rab GEF cascade mechanism. The mammalian Ypt1p homolog, Rab1, has several documented effectors, but none to date have been reported to have GEF activity.

Ypt32p-Sec2p-Sec4p cascade

On the yeast secretory pathway, Sec2p acts as a GEF for Sec4p, a Rab8 homolog that plays an essential role in the regulation of the final stage of the exocytic pathway (Figure 2) (12). Although Sec2p is normally concentrated on secretory vesicles along with its substrate Sec4p, temperature-sensitive sec2 mutants (sec2-59, sec2-78) mislocalize to the cytoplasm, and secretion is blocked. All of these phenotypes are suppressed by overexpression of Ypt32p. Sec2p interacts with the GTP-bound form of Ypt32p and has no GEF activity toward Ypt32p, indicating that Sec2p is an effector of Ypt32p (10). A subsequent study demonstrated that the Sec2p-Ypt32p interaction is required for Sec2p localization to the secretory vesicles (38). Thus, Ypt32p recruits Sec2p to the late Golgi membrane and possibly promotes vesicle budding from the Golgi compartment. Sec2p then catalyzes nucleotide exchange on the downstream Rab, Sec4p, which, in turn, leads to the delivery of vesicles and their fusion with the plasma membrane.

Rab11-Rabin8-Rab8 cascade

The mammalian orthologs of Ypt32p, Sec2p, and Sec4p are Rab11, Rabin8, and Rab8, respectively (Figure 2). Rab8 is involved in primary cilium formation, and its activation by Rabin8 is required for this function (39, 40). Rabin8 has specific GEF activity toward Rab8 (41). Rabin8 binds to the GTP-bound form of Rab11, and the interaction promotes activation of Rab8, which is required for ciliogenesis and apical membrane formation, indicating that a Rab GEF cascade directly analogous to the Ypt32-Sec2-Sec4 cascade is conserved in mammals (42, 43). Although Rab8 localizes to the primary cilium, Rabin8 is detected on Rab11-positive vesicles near the cilium base (44). Therefore, Rab11-positive vesicles may be converted into Rab8-positive compartments by a Rab transition mechanism. A recent study showed that Rabin8 binds to the mammalian TRAPP complex, and the localization of Rabin8 to the vesicle is TRAPP dependent; thus TRAPP may act together with Rab11 to recruit Rabin8 (44).

Rab33b-Rab6 cascade

The Golgi apparatus is composed of cis-, medial-, and trans-Golgi compartments (cisternae), and each cisterna has a distinct set of Golgi enzymes. These compartments may be maintained by a mechanism called “cisternal maturation,” in which each compartment gradually acquires, by vesicular traffic, the enzymes typifying the subsequent cisterna and donates its own resident enzymes to a preceding cistern (45, 46). By this model, resident proteins must be rapidly transported by retrograde traffic within the Golgi apparatus via COPI vesicles. Rab33b and Rab6 locate to the medial- and trans-Golgi compartments, respectively, and regulate retrograde intra-Golgi trafficking (Figure 2). Rab6 genetically interacts with the retrograde Golgi tether complex, conserved oligomeric Golgi (COG)3 and Zeste White 10 (ZW10), and knockdown of Rab6 suppresses COG3- or ZW10-depletion-induced disruption of the Golgi complex (47). Knockdown of Rab33b exhibits a phenotype similar to Rab6 depletion and overexpression of Rab33b displaces Rab6 from Golgi membranes (48). Although the precise molecular mechanism is unknown, Rab6 and Rab33b functionally overlap and might form a cascade for retrograde traffic within the Golgi apparatus.

Ryh1p-Ric1p/Rgp1p-Ypt3p cascade

The fission yeast proteins Ryh1p and Ypt3p are homologs of Rab6 (budding yeast Ypt6p) and Rab11 (budding yeast Ypt31p/Ypt32p), respectively (Figure 2). Deletion of ryh1 is synthetically lethal with a ypt3 mutation, and overexpression of the GDP-locked form of Ryh1p-T25N inhibits growth of a ypt3 mutant, indicating a genetic interaction between these two GTPases. Both Ryh1p and Ypt3p localize to the Golgi apparatus and endosome, where they regulate protein secretion and the recycling of the exocytic SNARE from endosomes to Golgi apparatus (49). The GEF for Ryh1p is presumed to be Ric1p, a component of the Ric1p/Rgp1p complex, which in budding yeast serves as a GEF for Ypt6p (50, 51). Although the GEF activity of Ric1p toward Ryh1p is unproven and it is unclear if Ric1p is an effector of Ypt3p, one could speculate that Ryh1p and Ypt3p form a Rab GEF cascade through the Ric1p/Rgp1p complex.

ADP Ribosylation Factors and Arf-Like Proteins

The ADP ribosylation factors (Arf) and Arf-like proteins (Arl) are small GTPases that regulate membrane traffic (8). Arf and Arl require nucleotide exchange for their function, and a number of GEFs for Arf and Arl have been identified to date (52). Arf and Arl also network with Rab proteins through cascade mechanisms.

Arf6-ARNO-Arf1 and Arl4-ARNO-Arf6 cascades

Arf1 localizes predominantly to the Golgi apparatus, where it regulates the formation of coated vesicles, whereas Arf6 localizes to the plasma membrane and is involved in cytoskeletal organization and endocytosis (Figure 2) (53). Although the functions of Arf1 and Arf6 are distinct, their GTP-bound conformations are very similar, and they share common effectors (54). The Arf nucleotide-binding site opener (Arno) has GEF activity toward both Arf1 and Arf6 but seems to prefer Arf1 over Arf6 (55). Arno has a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain that binds phosphatidylinositol 4,5-phosphate on the plasmamembrane. Interestingly, the PH domain of Arno also binds to the GTP-bound form of Arf6, and both lipid-binding and Arf6-binding abilities are required for recruitment of Arno to the plasma membrane. Arno leads to relocalization of Arf1 from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane, at least in part (55). A recent study showed that Arf6-GTP and liposomes promote the nucleotide exchange activity of Arno on Arf1 (56).

Arno also binds to the GTP-bound form of the Arf-like GTPase Arl4 together with phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and thereby relocates to the plasma membrane (57). Although Arno’s target at the plasma membrane is still unclear, these observations suggest that GTPases of the Arf branch can form a cascade through their interactions with a GEF that is analogous to the Rab GEF cascades discussed above.

Arl3p-Imh1p-Arl1p cascade

Two independent studies showed that the Golgi protein Imh1p, a yeast homolog of mammalian Golgin, mislocalizes to the cytoplasm when arl1 or arl3 is deleted (58, 59). Arl1p is a Golgi-localized GTPase, implicated in regulating Golgi structure and protein sorting (Figure 2) (60). The GRIP domain of Imh1p is able to bind directly to the GTP-bound form of Arl1p but not to Arl3p. Golgi localization of both Arl1p and Imh1p is nevertheless dependent on Arl3p, suggesting that Arl3p might recruit the GEF for Arl1p, forming a cascade.

Rho and Cdc42 GTPases

Rho (Ras homolog) GTPases play numerous cellular roles, including regulation of polarized cell growth, organization of the actin cytoskeleton, and axon signaling (61–63). Their role in regulating cellular polarity has been well studied. Rho proteins regulate both the assembly of the actin cytoskeleton and delivery, docking, and fusion of secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane. Yeast has six Rho GTPases, Rho1–5p, and Cdc42p (cell division cycle 42), yet only Rho1p and Cdc42p are essential. In mammals, 23 Rho member proteins have been identified, but only RhoA, Rac, andCdc42 have been studied in detail (64). Interestingly, a number of Rho GEFs and Rho GAPs have been identified, and a single Rho protein is often regulated by more than one GEF or GAP. However, it is not known if Rho family proteins form cascades through theirGEFs, as have been described for Rab and Arf. Below, we introduce a few examples of Rho networks relevant to membrane traffic.

Both Rho3p and Cdc42p are Exo70p effectors

Cellular polarization in yeast requires vectorial transport of secretory vesicles along actin cables. Rho3p and Cdc42p are key regulators of polarization of actin, whereas the type V myosin, Myo2p, directs the active delivery of vesicles on actin cables (65, 66). One of the Rho3p effectors is Exo70p, a component of the octameric exocyst complex needed for tethering secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane before fusion (67). Rho3p and Cdc42p mutants show similar trafficking defects, and both of them are required for efficient exocytosis, suggesting overlapping functions. Genetic studies have suggested that Exo70p is a target for both Rho3p and Cdc42p, and Wu et al. (68) showed that the GTP-locked forms of both Rho3p and Cdc42p are able to bind Exo70p, provided that they have undergone C-terminal prenylation. Thus, Exo70p is a common effector for both Rho3p and Cdc42p in exocytosis. Another exocyst component, Sec3p, works as an effector of both Rho1p and Cdc42p (69). The Cdc42p-Exo70p and Rho1p-Sec3p interactions appear to fulfill partially overlapping functions in exocyst localization; thus cross talk between these pathways may provide additional levels of regulation.

Rho1p and Cdc42p in vacuole fusion

In addition to regulation of cell polarity, both Rho1p and Cdc42p play roles in homotypic vacuole fusion (70, 71). This is supported by the observation that Rho guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor, Rdi1p, which extracts Rho1p and Cdc42p from the vacuole membrane, blocks vacuole fusion (70). Vacuole fusion is mediated by actin polymerization, which is initiated by Cdc42p (72). However, the mechanisms that trigger the activation of Cdc42p and Rho1p at the vacuole are unknown. Active Rho pools can be detected with probes containing the Rho-binding domains of their downstream effectors. Using such probes it was recently demonstrated that activation of Cdc42p and Rho1p occurs with different kinetics and conditions (73). Cdc42p is activated in an ATP-independent manner, whereas Rho1p activation requires ATP. Moreover, an in vitro vacuole fusion experiment showed that Cdc42p activation occurs within 5 min, but fusion signals reach a maximum at 60 min and correlate with Rho1p activation. Thus, Cdc42p and Rho1p may be sequentially activated to promote vacuole fusion.

Cross Talk Between Rab1, GBF1, and Arf1

The later stage of ER-to-Golgi transport requires COPI vesicle formation, which is mediated by Arf1 (74, 75). Arf1 activation is catalyzed by its nucleotide exchange factor, GBF1 (Golgi-specific brefeldin A resistance factor 1) (76). Rab1b is localized to the Golgi apparatus and ER-Golgi interface, and Rab1b is also required for ER-to-Golgi transport (77). A Rab1-Arf1 GTPase cascade has been proposed on the basis of genetic studies in yeast (78). Indeed, mammalian Rab1b in its GTP-bound form physically interacts with GBF1 (79). Rab1b is required for membrane association of GBF1 and Arf1 at ER exit sites. Therefore, a Rab1b-GBF1-Arf1 cascade stabilizes activated Arf1 on the membrane and promotes COPI recruitment and vesicle formation.

Ras-RLIP76-Arf6-Rac

The Ras family GTPase related-Ras (R-Ras) regulates pleiotopic cellular functions, including inhibition of cell proliferation and promotion of cell adhesion, spreading, and migration (80–84). R-Ras mediates these pathways through its effectors and thereby augments the activation of another GTPase, Rac1 (83). RLIP76 (RalBP1) was identified as an R-Ras specific effector (85). The interaction between active R-Ras and RLIP76 is required for cell spreading by promoting Rac1 GTPase activity. By contrast, the Arf6 GTPase regulates endosomal trafficking of Rac1 and mediates Rac1 activation (86). Interestingly, the cell spreading defect in RLIP76-depleted cells can be rescued by activation of Arf through overexpression of the Arf GEF Arno. Indeed, Arno directly binds to RLIP76 in vivo (77, 85). Thus, active R-Ras recruits RLIP76, which, in turn, binds to Arno to activate Arf6 and then consequently activates Rac1. This multiple GTPase cascade promotes cell spreading and migration.

RAB-GUANINE NUCLEOTIDE EXCHANGE FACTOR POSITIVE-FEEDBACK LOOPS

Local activation of Rab GTPases is important for their functions on specific membrane regions. Thus, proper localization of the GEF is the key to the activation of Rab at the right place. GEFs often directly bind to one of the effectors of the substrate Rab. This results in a Rab-GEF-effector complex, potentially generating a positive-feedback loop: (a) The GEF activates the Rab, (b) the activated Rab recruits its effector, (c) the effector binds to GEF, and (d) the GEF activates more Rab protein (Figure 3a). This positive-feedback loop could lead to the formation of a metastable platform of highly activated Rab proteins and highly concentrated effectors.

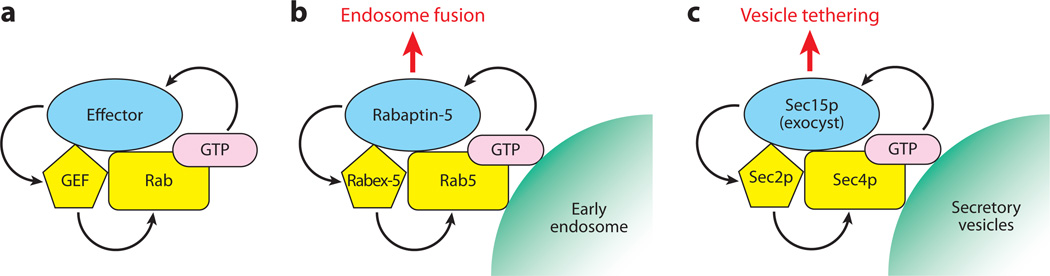

Figure 3.

Rab-guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF)-effector positive-feedback loop. (a) Upon Rab activation by its GEF, a GTP-bound Rab recruits its effector(s). An effector then binds to the GEF and increases the exchange activity on the Rab GTPase. This Rab-GEF-effector positive-feedback loop stabilizes the active Rab region on the membrane. (b) Rab5 is activated by its GEF Rabex-5, and then active Rab5 recruits its effector Rabaptin-5. Rabaptin-5, in turn, binds to Rabex-5 directly (87, 88). Association with Rabaptin-5 increases Rabex-5 activity toward Rab5, thereby stabilizing Rab5 in a GTP-bound state on the early endosome, which is needed for endosomal fusion (89). (c) In the yeast secretory pathway, Sec2p, which is recruited to the membrane by Ypt32p-GTP, activates Sec4p on the secretory vesicles (12). The GTP-bound form of Sec4p recruits Sec15p, which is a component of the exocyst complex (90). Sec15p binds to Sec2p and displaces Ypt32p (11). Sec2p is able to activate Sec4p, and Sec4p again recruits Sec15p, which leads to vesicle tethering with the plasma membrane through the exocyst complex prior to membrane fusion.

Rab5, Rabex-5, and Rabaptin-5

As mentioned in a previous section, Rab5 is activated by its GEF, Rabex-5. A number of Rab5 effectors have been identified, and each of them seems to regulate distinct downstream events. One of Rab5 effectors is Rabaptin-5 (87). Rabaptin-5 directly binds to Rabex-5, and the interaction is essential for endosomal fusion (88). Later it was shown that Rabaptin-5 stimulates Rabex-5 exchange activity in vitro (89). Although Rabaptin-5 is found to bind Rab5-GTP, recruitment of Rabaptin-5 to the membrane depends on its association with Rabex-5. This observation suggests that Rabex-5 and Rabaptin-5 work as a complex to stabilize an active Rab5 cluster on the endosome. Thus, the Rabex-5-Rabaptin-5 complex is recruited to the membrane, activates Rab5, and then Rabaptin-5 binds to Rab5 to form a positive-feedback loop promoting endosomal fusion (Figure 3b).

Sec4p, Sec2p, and Sec15p

In yeast, Sec2p, Sec4p and Sec15p work together on the secretory pathway. Sec15p, a component of exocyst complex, binds to GTP-bound Sec4p, following activation by its GEF, Sec2p (12, 90). Interestingly, Sec2p and Sec15p directly bind to each other on the surface of secretory vesicles; thus the Rab, its GEF, and effector (Sec4p-Sec2p-Sec15p) form a complex (Figure 3c) (11). This situation is some-what different from the case of Rab5-Rabex-5-Rabaptin-5 because Sec15p does not appear to modulate the GEF activity of Sec2p.

A recent study (38) has shown that Sec2p is recruited to the membrane by the combined signals of Ypt32p-GTP and phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P). Ypt32p and Sec15p compete for Sec2p binding, and the interaction of these proteins is regulated by PI4P (11, 38). Sec2p-Sec15p binding is inhibited by PI4P, yet the PI4P level on secretory vesicles appears to decrease as the vesicles are delivered to exocytic sites (38). Thus, after Sec2p recruitment to the Golgi membrane by active Ypt32p and PI4P, PI4P levels decrease, allowing Sec15p to displace Ypt32p and form a complex with Sec2p. Thus a switch from a Rab GEF cascade (Ypt32p-Sec2p-Sec4p) to a Sec2p-Sec4p-Sec15p positive-feedback loop transition may be regulated by PI4P levels, facilitating vesicle tethering and fusion with the plasma membrane. In mammals, the Ypt32p ortholog Rab11 directly binds to Sec15, indicating that the exocyst functions as a Rab11 effector, which is somewhat different from the yeast system (91).

GTPase-ACTIVATING PROTEIN CASCADES

The sequential recruitment and activation of Rabs, in an ordered series, may help define the directionality of membrane traffic. The Rab GEF cascade mechanism, discussed above, proposes that an upstream Rab recruits the GEF for the Rab acting just downstream, thereby initiating a Rab conversion along a transport pathway. However, the spatial and temporal regulation of Rab function requires not only GEFs to activate the appropriate Rab at the right time and place but also GAPs to inactivate the Rab after it has fulfilled its function and as it migrates beyond its limited domain on the surface of an organelle. Live-cell imaging has demonstrated that the colocalization of adjacent Rabs is typically only transient (92), suggesting the existence of a mechanism to avoid a prolonged overlap of active Rabs on the same membrane domain. One possibility is a GAP cascade mechanism in which the downstream Rab, in its active form, recruits the GAP that inactivates the upstream Rab, thus limiting overlap. The GEF and GAP cascades working in a countercurrent fashion could serve as self-organizing systems to promote an efficient, spatially and temporally controlled Rab conversion processes. We describe several examples of GAP cascades along the exocytic and endocytic pathways of eukaryotic cells that promote Rab conversions. In addition, we describe examples of GAP cascades involving members from different branches of the Ras superfamily.

Ypt1p, Gyp1p, and Ypt31p/Ypt32p

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells, Ypt1p and Ypt31p/Ypt32p are essential Rabs that act sequentially. Ypt1p is the homolog of Rab1, and it plays an important role in membrane traffic from the ER to the Golgi apparatus and within the Golgi apparatus (Figure 2) (93, 94). Ypt31p and Ypt32p are highly similar and functionally redundant homologs of Rab11 required for the exit of exocytic cargo from a late-Golgi compartment (95, 96). Even though both Ypt1p and Ypt31p/Ypt32p are associated with Golgi compartments, their overlap is low (97). Furthermore, live-cell imaging of individual Golgi compartments in yeast cells shows that they undergo a transition from Ypt1p to Ypt31p/Ypt32p, consistent with a Golgi maturation model (45, 46). Gyp1p, a Tre-2/Bub2/Cdc16 (TBC) domain-containing protein, which localizes to the Golgi apparatus, has been identified as the GAP that downregulates Ypt1p in vivo (98, 99). A GAP cascade model predicts that Gyp1p would be recruited to the Golgi membrane by binding to the active form of Ypt31p/Ypt32p. Yeast two-hybrid analysis and in vitro binding experiments demonstrated that Gyp1p interacts with Ypt31p/Ypt32p (97). The interaction between Gyp1p and Ypt32p depends on the first 200 amino acids of Gyp1p, and not the C-terminal portion, where the Gyp1p TBC GAP catalytic domain resides. Moreover, this interaction is important for the recruitment of Gyp1p to the Golgi compartment because a Gyp1p construct missing the first 200 amino acids remains cytosolic and loss of Ypt31p/Ypt32p results in mislocalization and destabilization of Gyp1p. Further support for a Rab GAP cascade mechanism came from live-cell imaging analysis of Ypt1p and Ypt32p localization in gyp1-deficient cells. On the basis of the GAP cascade model, the loss of Gyp1p should prolong the overlap between Ypt1p and Ypt32p on Golgi compartments. Live-cell imaging analysis of Ypt1p and Ypt32p in gyp1-deficient cells shows an increase in the colocaliziation between Ypt1p and Ypt32p in comparison with normal cells. In normal cells, Ypt1p compartments undergo a rapid conversion to Ypt32p compartments; however, in gyp1-deficient cells, this transition is greatly slowed. In addition, the absence of Gyp1p leads to increased colocalization of the Ypt1p effector, Cog3p, with the late Golgi marker Sec7p, demonstrating the mistargeting of a Ypt1p effector. The mislocalization of Cog3p may explain some of theGolgi complex–associated trafficking defects described in gyp1-deficient cells (98, 100). A question that remains to be answered regarding this GAP cascade is how the recruitment of other Ypt32p effectors, such as Sec2p or Rcy1p, might affect the interaction of Gyp1p with Ypt32p (10, 101).

Rab5, TBC-2, and Rab7

Mammalian endosomes undergo a conversion from Rab5 to Rab7 as they mature from early endosomes to late endosomes (Figure 2) (92), and this conversion appears to involve a GEF cascade mechanism. However, a mathematical model of Rab5-to-Rab7 conversion suggests the need for a cut-out switch mechanism in which Rab7 activation leads to removal of Rab5 (102). A cut-out switch could be explained by a Rab GAP cascade in which a GAP for Rab5 is recruited once the proper level of active Rab7 is acquired by the endosomal membrane. However, identifying a GAP cascade that would trigger the loss of Rab5 as Rab7 is activated has been hampered owing to the difficulty of identifying the relevant GAP for Rab5. Studies have identified several GAPs that affect Rab5 activity (RabGAP-5, RN-Tre) in mammalian cells; however, the loss of these GAPs does not lead to an increased overlap between Rab5 and Rab7, as expected for a GAP cascade, but rather it affects the functionality of the early endosome (103–105).

Conversion from Rab5 to Rab7 has also been observed during the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in C. elegans (106). C. elegans express 21 gene products containing TBC GAP domains, in comparison to the approximately 50 TBC proteins in mammalian cells. The powerful genetic and cell biological tools of C. elegans have helped to establish TBC-2 as a GAP for Rab5 that is important for a Rab5-to-Rab7 conversion (107). TBC-2, a homolog of human TBC1D2 and TBC1D2B, contains three conserved domains: an N-terminal PH domain, a coiled-coil region, and a C-terminal TBC domain. Worms deficient for TBC-2 accumulate large intestinal vesicles, which contain Rab7 and other late endosome markers on their membranes (108). These enlarged endosomes also contained Rab5 but not other Rabs, such as Rab10 or Rab11, suggesting an increased colocalization of Rab5 and Rab7 on the same compartment, a phenotype expected upon disruption of a Rab GAP cascade. These effects can be phenocopied by the expression of a Rab5 GTP hydrolysis-deficient mutant (Rab5-Q78L), demonstrating that the accumulation of these large vesicles is associated with the failure to inactivate Rab5. In further support of the Rab GAP cascade model is the observation that TBC-2 requires Rab7 to localize to endosomal compartments (108). The domain of TBC-2 that is important for the interaction with Rab7 remains to be elucidated, and it is important to determine if the PH domain of TBC-2 regulates this interaction.

Sec4p, Msb3p, Msb4p, and Cdc42p

In budding yeast, Sec4p, a homolog of mammalian Rab8, serves as the final Rab on the exocytic pathway (Figure 2). Sec4p is highly concentrated on secretory vesicles, where it acts to recruit several effectors, including the exocyst tethering complex, and to ensure the fusion of vesicles at the site of polarized secretion (90, 109). It is difficult to envisage how a Rab GAP cascade mechanism could remove Sec4p following exocytic fusion because there is no Rab that acts downstream of Sec4p on the plasma membrane. However, Rho GTPases are known to concentrate on the plasma membrane, where they control cell polarity and actin polymerization (110). A variant GAP cascade mechanism, which includes a RhoGTPase that recruits the GAP for Sec4p to the site of polarized secretion, may explain this conundrum. Msb3p/Msb4p are redundant GAPs that localize to the site of polarized secretion in yeast and exhibit GAP activity toward Sec4p in vitro (111). The localization and function of these GAPs require interactions with the polarisome subunit, Spa2p, and the Rho GTPase, Cdc42p (112). Moreover, the N-terminal domains of Msb3p/Msb4p are important for their interaction with Spa2p (112). However, the domain important for the interaction with Cdc42p has not yet been determined. The recruitment of Msb3p/Msb4p by these interactions would promote the inactivation of Sec4p at sites of polarized cell growth and would thereby ensure that Sec4p and its effectors are efficiently recycled from the membrane following fusion.

Rab35, Centaurinβ2, and Arf6

Mammalian cells contain more than 60 Rabs, and an important aspect of characterizing their function has been to identify effectors for each Rab. Recent screens have identified novel interacting partners for some of these Rabs (113, 114). Centaurinβ2 was identified as an effector of Rab35. Centaurinβ2 contains five domains: two coiled-coil domains, a PH domain, an Arf GAP domain, and an ANKR domain. In vitro binding experiments demonstrated that the interaction with Rab35 depends on the ANKR domain, and localization of Centaurinβ2 to the plasma membrane of cells depends on the expression of Rab35. The fact that Centaurinβ2 also contains an Arf GAP domain suggests that the interaction with Rab35 is important for the inactivation of an Arf GTPase. Analysis of the GTP-Arf6 levels on cells expressing Rab35 andCentaurinβ2 show a reduced level of GTP-Arf6, implicating Arf6 as a possible target of the Rab35-Centaurinβ2 complex (114).

The same screen also indicated that Rab22A interacts with the Rab GAP mKIAA1055 and that Rab36 interacts with GAPCenA protein (114). The mKIAA1055 interaction with Rab22A occurs through its coiled-coil region, and GAPCenA interacts with Rab36 through its PTB domain. Neither of these Rab GAPs showed significant GAP activity against these Rab-binding partners; however, they colocalized with them when coexpressed in mammalian cells. These results suggest the possibility of a Rab GAP cascade, yet the Rab substrates for mKIAA1055 and GAPCenA remain to be identified. It is important to determine if the loss of these GAPs increases the overlap of their substrate Rabs with Rab22A or Rab36.

RABS WITH COMMON EFFECTORS

The Rab family includes a large number of members, each concentrated on a specific membrane compartment or set of compartments (89). Many organelles, such as the Golgi apparatus and endosomes, are marked by multiple Rabs (Figure 2) (115), as would be expected because of the extensive membrane exchange that occurs between subcellular compartments. Still, the main function of Rabs is to direct the recruitment of their specific effectors to these locations. Recent studies have shown that certain effectors can interact with multiple Rabs, sometimes in combinations. Compartments carrying these multivalent effectors may represent crossroads where the sorting of protein and membrane must be regulated.

Rab4, Rab14, and Rabip4/RUFY1

Rab4 and Rab14 play significant roles in membrane traffic at the endosomal level. Rab4 is important in directing cargo between the sorting endosome and the recycling endosome, where it colocalizes with Rab5 and Rab11 (116, 117). Rab14 is important for traffic between the endosomes and a late Golgi compartment (118). In addition, Rab14 is associated with vesicles carrying the glucose transporter 4. These vesicles are generated from endosome and Golgi membranes and are translocated to the plasma membrane in response to insulin (119). Rabip4/RUFY1 was first identified as a Rab4 effector; however, it has also been shown to interact with Rab5 and play a role in trafficking from endosomes (120, 121). Rabip4 is composed of a RUN domain, two coiled-coil domain, and a FYVE motif. A recent study found that Rabip4 is also an effector of Rab14 (122). The interaction of Rabip4 with Rab14 is important for the localization of Rabip4 to the endosomes, where it is also colocalizes with Rab4 and Rab5 (122). Moreover, when Rab4, Rab14, and Rabip4 are coexpressed, endosomes become larger than normal. The study suggests a sequential interaction of Rabip4 with Rab14 and Rab4 to promote endosome tethering and fusion. Interestingly, Rabip4 can also interact with, and be phosphorylated by, the tyrosine kinase Etk, and this modification is important for Rabip4 localization to the endosomal membrane (123). This suggests a regulated mechanism that depends on the phosphorylation of Rabip4 to control its localization to the endosomes. It will be interesting to determine if such a mechanism can regulate the Rabip4 interaction with Rab14.

Rab4, Rab11, and D-AKAP2

Rab4 and Rab11 are important for the proper sorting of cargo and recruitment of effectors to the sorting and recycling endosome, respectively (116, 117). These Rabs also regulate the kinetics of recycling from endosomes; Rab4 controls fast recycling and Rab11 controls slow recycling from a perinuclear compartment (124). D-AKAP2 (dual-specific A-kinase-anchoring protein 2) contains three regulators of G protein–signaling domains, a protein kinase A–interacting domain, and a PDZ-binding motif (125). D-AKAP2 interacts with Rab4 and Rab11 through the region containing a regulator of G protein–signaling domain, and this interaction is important for the localization of D-AKAP2 to compartments containing Rab4 and Rab11 (125). However, yeast two-hybrid analysis and in vitro binding studies demonstrated preferential binding of D-AKAP2 to Rab11wt or Rab11S25N (mimicking the GDP-bound form), as well as to Rab4-Q67L (hydrolysis-deficient, GTP-bound form). These results suggest that D-AKAP2 is an effector of Rab4 and that it might have GEF activity toward Rab11, suggesting a possible GEF cascade. Interestingly, depletion of D-AKAP2 causes Rab11 compartments to accumulate in the cell periphery and causes the endosomal cargos to be released more rapidly from the cells (125). It is important to elucidate whether the protein kinase A–interacting domain of D-AKAP2 and the possible recruitment of PKA play any role in the function of this protein at the endosomal level.

Families of Interacting Proteins: Rab11 and Rab14

The Rab11 family of interacting proteins (FIPs) comprise five Rab11 effectors. These have been divided into two classes on the basis of their domain composition. Class I contains a C2 lipid-binding domain at theNterminus, a coiled-coil region, and a Rab11-binding domain (RBD) domain at theCterminus. Members of this class are Rip11, FIP2, and RCP. Class II contains EF domains at the N terminus and multiple coiled-coil domains with the RBD at the C terminus. Members of this class are FIP3 and FIP4 (126). A yeast two-hybrid screen revealed that FIP2 can interact with Rab14 (127) and that the GTPase-deficient mutant, Rab14-Q70L, interacts with the other two class I FIPs (127). The same study demonstrated that Rab14-Q70L localizes to recycling endosomes, whereas Rab14 S25N localizes to the Golgi apparatus. Rab14 interacts with the RBD domain of FIPs, suggesting either competition or cooperation with Rab11 for this binding site (127). It will be interesting to determine if any of the interactions between Rab14 and class I FIPs are regulated in a cell cycle–dependent manner to ensure the targeting of Rab14-Rab11 containing vesicles to the cleavage furrows of dividing cells.

Rab6, Rab11, and R6IP1

Rab6 plays a variety of roles in membrane traffic to and from the Golgi apparatus (128–131). More recently, it has also been associated with trafficking of post-Golgi vesicles to the plasma membrane and in the fission of vesicles from the Golgi apparatus (132–134). R6IP1A and R6IP1B are isoforms of a Rab6 effector, identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen, that contain two RUN domains (135). RUN domains have been shown to interact with both Rap and Rab GTPases (136). In addition to binding Rab6, R6IP1 can also interact with Rab11 (137). Interestingly, overexpression of Rab11 relocalizes R6IP1 onto endosomes from its normal Golgi membrane association mediated by binding Rab6 (137). The interaction of R6IP1 with both Rab11 and Rab6 might direct the traffic of vesicles from a Rab11 compartment to a Rab6 compartment when active Rab11 levels are high. For example, cells depleted of R6IP1 displayed a defect in cell division, a process that requires high temporal and spatial regulation of Rab11 endosomes (137, 138). More extensive analysis of the interaction between Rab11 and R6IP1 is required to determine which domain of R6IP1 is important for the interaction and to investigate how changes in this domain may change the ability of R6IP1 to localize to Rab11-positive compartments or how this interaction may change the ability of Rab11 to interact with the different FIP proteins.

Rab1, Rab6, and Giantin

There are several long coiled-coil proteins present on Golgi or endosomal membranes in mammalian cells that have been characterized as tethering factors (139) and Rab effectors. Giantin is the largest coiled-coil protein identified (3260 amino acids), and it has a putative trans-membrane domain at its C terminus that anchors it to the Golgi membrane. At the cis-Golgi level, the coiled-coil proteins p115 and GM130 have been established as effectors of Rab1 (140–142). In addition, these proteins interact with each other to regulate SNARE complex assembly (140, 143–145). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that Giantin can interact with and compete against GM130 for binding to the C terminus of p115 (146–148). The interaction of GM130 and Giantin with p115 is important for the tethering of COPII and COPI containing vesicles at the Golgi level (145). In addition, Giantin also interacts with Rab1 and Rab6, suggesting a possible mechanism of regulation of tethering of different classes of vesicles at the Golgi level, which may depend on the interaction of these Rabs with multiple coiled-coil proteins (149). The interaction of Giantin with Rab1 and Rab6 occurs at a similar region, amino acids 162–357; however, in vitro analysis has shown a better binding of Giantin with Rab6 than with Rab1 (149). Because of the recent findings that Rab6 can play an important role in exocytosis and vesicle fission from the Golgi apparatus (132, 133), it will be interesting to determine if the interaction with Giantin plays any role in these Rab6-dependent pathways. This would suggest a mechanism whereby traffic within the Golgi apparatus depends on the interactions of Giantin with both Rabs, but exit from the Golgi apparatus depends solely on the interaction of Giantin with Rab6.

Rab8, Rab13, and JRAB/MICAL-L2

MICAL represents a family of five proteins with the following domain composition: a FAD domain, a CH domain, a LIM domain, and coiled-coil domains. MICAL members have been identified as effectors for various Rabs (150). JRAB/MICAL-L2 is an effector of Rab13 that is important for the proper targeting of occludin to tight junctions (TJs) of polarized ephitelial cells (151, 152). This role depends on the C-terminal coiled-coil domain because deletion of this domain impaired the recycling of occludin, but not the recycling of the transferrin receptor to the plasma membrane of epithelial cells (152). Rab8 has also been implicated in traffic from endosomes to the basolateral membranes of polarized cells (153, 154). In polarized cells, TJs act as boundaries between the apical and basolateral membranes, whereas adherens junctions (AJs) are needed to stabilize cell-to-cell contacts (155). The TJ and AJ are composed of similar proteins; however, their localization at the plasma membrane is different. Moreover, it was observed that Rab13 depletion affects occludin delivery but not that of E-cadherin, suggesting distinct pathways for the delivery of these proteins to the plasma membrane (155). Nonetheless, JRAB depletion reduces the delivery of both proteins. By analyzing the interaction of JRAB with other Rabs, it was found that JRAB interacts with Rab8 in addition to Rab13. Interestingly, the interaction with Rab8 also depends on the coiled-coil domain of JRAB, and binding experiments demonstrated that Rab8 and Rab13 compete for binding to JRAB (155). Moreover, the interaction of JRAB with Rab8 and Rab13 occurs at different cellular compartments. The location and interaction of JRAB with these Rabs support its role in establishing both a TJ and an AJ and demonstrate how regulating the interaction of an effector with different Rabs can regulate the sorting of different cargos. It is important to determine if the interaction with a specific Rab allows JRAB to interact with specific cargos at the endosome level and if the interaction can promote JRAB to interact with other proteins. Recently, it has been demonstrated that MICAL3, Rab6, and Rab8 play roles in the docking and fusion of vesicles; however, Rab6 was proposed to interact with MICAL3/Rab8 through its effector ELKS, which can also bind MICAL3 (156).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We have presented some examples of the different mechanisms that link together two or more GTPases into a regulatory circuit that controls membrane traffic. As research continues, other mechanisms, no doubt, may come to light. Over time, we will learn how commonly these mechanisms are used in the regulation of the many stages of membrane traffic and to what extent they are conserved between species. A more complete description will require mathematical modeling of these regulatory networks with quantitative evaluation of all of the key parameters. This would represent an important step toward an understanding at a molecular level of the exocytic and endocytic pathways as stable, self-organizing systems.

SUMMARY POINTS.

GEF cascades and GAP cascades, working in concert, can direct a programmed series of GTPase transitions, while GEF-effector interactions can generate positive-feedback loops that lead to the formation of membrane domains marked by highly activated pools of a GTPase. The net effect of these various mechanisms is the establishment of regulatory circuits that control membrane traffic.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Additional studies are needed to establish the generality of the mechanisms presented here and to define at a quantitative level the effects of these mechanisms on membrane traffic. It will be interesting and informative to test the effects of “rewiring” the circuitry by mixing and matching the different domains of GEFs, GAPs, and effectors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants GM35370 and GM082861 from the National Institutes of Health (P.N.). E.M.Y. was supported by a fellowship from theHuman Frontier Science Program.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Spang A, Herrmann JM, Hamamoto S, Schekman R. The ADP ribosylation factor-nucleotide exchange factors Gea1p and Gea2p have overlapping, but not redundant functions in retrograde transport from the Golgi to the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12(4):1035–1045. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schalk I, Zeng K, Wu SK, Stura EA, Matteson J, et al. Structure and mutational analysis of Rab GDP-dissociation inhibitor. Nature. 1996;381(6577):42–48. doi: 10.1038/381042a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang M, Weissman JT, Beraud-Dufour S, Luan P, Wang C, et al. Crystal structure of Sar1-GDP at 1.7 A resolution and the role of the NH2 terminus in ER export. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155(6):937–948. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg J. Structural basis for activation of ARF GTPase: mechanisms of guanine nucleotide exchange and GTP-myristoyl switching. Cell. 1998;95(2):237–248. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillingham AK, Munro S. The small G proteins of the Arf family and their regulators. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:579–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosshans BL, Ortiz D, Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(32):11821–11827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira-Leal JB, Seabra MC. Evolution of the Rab family of small GTP-binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313(4):889–901. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):347–358. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortiz D, Medkova M, Walch-Solimena C, Novick P. Ypt32 recruits the Sec4p guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Sec2p, to secretory vesicles; evidence for a Rab cascade in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157(6):1005–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medkova M, France YE, Coleman J, Novick P. The rab exchange factor Sec2p reversibly associates with the exocyst. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17(6):2757–2769. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walch-Solimena C, Collins RN, Novick PJ. Sec2p mediates nucleotide exchange on Sec4p and is involved in polarized delivery of post-Golgi vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137(7):1495–1509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLauchlan H, Newell J, Morrice N, Osborne A, West M, Smythe E. A novel role for Rab5-GDI in ligand sequestration into clathrin-coated pits. Curr. Biol. 1998;8(1):34–45. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semerdjieva S, Shortt B, Maxwell E, Singh S, Fonarev P, et al. Coordinated regulation of AP2 uncoating from clathrin-coated vesicles by rab5 and hRME-6. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183(3):499–511. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen E, Severom F, Backer JM, Hyman AA, Zerial M. Rab5 regulates motility of early endosomes on microtubules. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1(6):376–382. doi: 10.1038/14075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubino M, Miaczynska M, Lippé R, Zerial M. Selective membrane recruitment of EEA1 suggests a role in directional transport of clathrin-coated vesicles to early endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(6):3745–3748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stenmark H, Parton RG, Steele-Mortimer O, Lütcke A, Gruenberg J, Zerial M. Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J. 1994;13(6):1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbero P, Bittova L, Pfeffer SR. Visualization of Rab9-mediated vesicle transport from endosomes to the trans-Golgi in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156(3):511–518. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vonderheit A, Helenius A. Rab7 associates with early endosomes to mediate sorting and transport of Semliki forest virus to late endosomes. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(7):e233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzdis Y, Zerial M. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell. 2005;122(5):735–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seals DF, Eitzen G, Margolis N, Wickner WT, Price A. A Ypt/Rab effector complex containing the Sec1 homolog Vps33p is required for homotypic vacuole fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(17):9402–9407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wurmser AE, Sato TK, Emr SD. New component of the vacuolar class C-Vps complex couples nucleotide exchange on the Ypt7 GTPase to SNARE-dependent docking and fusion. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151(3):551–562. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nordmann M, Cabrera M, Perz A, Bröcker C, Ostrowicz C, et al. The Mon1-Ccz1 complex is the GEF of the late endosomal Rab7 homolog Ypt7. Curr. Biol. 2010;20(18):1654–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poteryaev D, Datta S, Ackema K, Zerial M, Spang A. Identification of the switch in early-to-late endosome transition. Cell. 2010;141(3):497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poteryaev D, Fares H, Bowerman B, Spang A. Caenorhabditis elegans SAND-1 is essential for RAB-7 function in endosomal traffic. EMBO J. 2007;26(2):301–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira-Leal JB, Seabra MC. The mammalian Rab family of small GTPases: definition of family and subfamily sequence motifs suggests a mechanism for functional specificity in the Ras superfamily. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301(4):1077–1087. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenmark H, Olkkonen VM. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol. 2001;2(5):REVIEWS3007. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-5-reviews3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu H, Liang Z, Li G. Rabex-5 is a Rab22 effector and mediates a Rab22-Rab5 signaling cascade in endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4720–4729. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woller B, Luiskandl S, Popovic M, Prieter BE, Ikonge G, et al. Rin-like, a novel regulator of endocytosis, acts as guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rab5a and Rab22. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1813(6):1198–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horazdovsky BF, Busch GR, Emr SD. VPS21 encodes a rab5-like GTP binding protein that is required for the sorting of yeast vacuolar proteins. EMBO J. 1994;13(6):1297–1309. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peplowska K, Markgraf DF, Ostrowicz CW, Bange G, Ungermann C. The CORVET tethering complex interacts with the yeast Rab5 homolog Vps21 and is involved in endo-lysosomal biogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2007;12(5):739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostrowicz CW, Bröcker C, Ahnert F, Nordmann M, Lachmann J, et al. Defined subunit arrangement and Rab interactions are required for functionality of the HOPS tethering complex. Traffic. 2010;11(10):1334–1346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang CW, Stromhaug PE, Kauffman EJ, Weisman LS, Klionsky DJ. Yeast homotypic vacuole fusion requires the Ccz1-Mon1 complex during the tethering/docking stage. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163(5):973–985. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones S, Litt RJ, Richardson CJ, Segev N. Requirement of nucleotide exchange factor for Ypt1 GTPase mediated protein transport. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130(5):1051–1061. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang W, Sacher M, Ferro-Novick S. TRAPP stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on Ypt1p. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151(2):289–296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sacher M, Barrowman J, Wang W, Horecka J, Zhang Y, et al. TRAPP I implicated in the specificity of tethering in ER-to-Golgi transport. Mol. Cell. 2001;7(2):433–442. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W, Ferro-Novick S. A Ypt32p exchange factor is a putative effector of Ypt1p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:3336–3343. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizuno-Yamasaki E, Medkova M, Coleman J, Novick P. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate controls both membrane recruitment and a regulatory switch of the Rab GEF Sec2p. Dev. Cell. 2010;18(5):828–840. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshimura S, Egerer J, Fuchs E, Haas AK, Barr FA. Functional dissection of Rab GTPases involved in primary cilium formation. J. Cell Biol. 2007;178(3):363–369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nachury MV, Loktev AV, Zhang Q, Westlake CJ, Peränen J, et al. A core complex of BBS proteins cooperates with the GTPase Rab8 to promote ciliary membrane biogenesis. Cell. 2007;129(6):1201–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hattula K, Furuhjelm J, Arffman A, Paränen J. A Rab8-specific GDP/GTP exchange factor is involved in actin remodeling and polarized membrane transport. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:3268–3280. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knödler A, Feng S, Zhang J, Zhang X, Das A, et al. Coordination of Rab8 and Rab11 in primary ciliogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(14):6346–6351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002401107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryant DM, Datta A, Rodríguez-Fraticelli AE, Peränen J, Martín-Belmonte F, Mostov KE. A molecular network for de novo generation of the apical surface and lumen. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12(11):1035–1045. doi: 10.1038/ncb2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westlake CJ, Baye LM, Nachury MV, Wright KJ, Ervin KE, et al. Primary cilia membrane assembly is initiated by Rab11 and transport protein particle II (TRAPPII) complex-dependent trafficking of Rabin8 to the centrosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(7):2759–2764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018823108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuura-Tokita K, Takeuchi M, Ichihara A, Mikuriya K, Nakano A. Live imaging of yeast Golgi cisternal maturation. Nature. 2006;441(7096):1007–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature04737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Losev E, Reinke CA, Jellen J, Strongin DE, Bevis BJ, Glick BS. Golgi maturation visualized in living yeast. Nature. 2006;441(7096):1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature04717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y, Shestakova A, Hunt L, Sehgal S, Lupashin V, Storrie B. Rab6 regulates both ZW10/RINT-1 and conserved oligomeric Golgi complex-dependent Golgi trafficking and homeostasis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18(10):4129–4142. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Starr T, Sun Y, Wilkins N, Storrie B. Rab33b and Rab6 are functionally overlapping regulators of Golgi homeostasis and trafficking. Traffic. 2010;11(5):626–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He Y, Sugiura R, Ma Y, Kita A, Deng L, et al. Genetic and functional interaction between Ryh1 and Ypt3: two Rab GTPases that function in S. pombe secretory pathway. Genes Cells. 2006;11(3):207–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siniossoglou S, Peak-Chew SY, Pelham HR. Ric1p and Rgp1p form a complex that catalyses nucleotide exchange on Ypt6p. EMBO J. 2000;19(18):4885–4894. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.18.4885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma Y, Sugiura R, Zhang L, Zhou X, Takeuchi M, et al. Isolation of a fission yeast mutant that is sensitive to valproic acid and defective in the gene encoding Ric1, a putative component of Ypt/Rab-specific GEF for Ryh1 GTPase. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2010;284(3):161–171. doi: 10.1007/s00438-010-0550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casanova JE. Regulation of Arf activation: the Sec7 family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Traffic. 2007;8(11):1476–1485. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gillingham AK, Munro S. The small G proteins of the Arf family and their regulators. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:579–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pasqualato S, Ménétrey J, Franco M, Cherfils J. The structural GDP/GTP cycle of human Arf6. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(3):234–238. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen LA, Honda A, Varnai P, Brown FD, Balla T, Donaldson JG. Active Arf6 recruits ARNO/cytohesin GEFs to the PM by binding their PH domains. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18(6):2244–2253. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-0998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stalder D, Barelli H, Gautier R, Macia E, Jackson CL, Antonny B. Kinetic studies of the Arf activator Arno on model membranes in the presence of Arf effectors suggest control by a positive feedback loop. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(5):3873–3883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hofmann I, Thompson A, Sanderson CM, Munro S. The Arl4 family of small G proteins can recruit the cytohesin Arf6 exchange factors to the plasma membrane. Curr. Biol. 2007;17(8):711–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Setty S, Shin ME, Yoshino A, Marks MS, Burd CG. Golgi recruitment of GRIP domain proteins by Arf-like GTPase 1 is regulated by Arf-like GTPase 3. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:401–404. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Panic B, Whyte JRC, Munro S. The ARF-like GTPases Arl1p and Arl3p act in a pathway that interacts with vesicle-tethering factors at the Golgi apparatus. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Munro S. The Arf-like GTPase Arl1 and its role in membrane traffic. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33(4):601–605. doi: 10.1042/BST0330601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez P, Rincón SA. Rho GTPases: regulation of cell polarity and growth in yeasts. Biochem. J. 2010;426(3):243–253. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sit ST, Manser E. Rho GTPases and their role in organizing the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt. 5):679–683. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Samuel F, Hynds D. RHO GTPase signaling for axon extension: Is prenylation important? Mol. Neurobiol. 2010;42(2):133–142. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wherlock M, Mellor H. The Rho GTPase family: a Racs to Wrchs story. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt. 2):239–240. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adamo JE, Moskow JJ, Gladfelter AS, Viterbo D, Lew DJ, Brennwald PJ. Yeast Cdc42 functions at a late step in exocytosis, specifically during polarized growth of the emerging bud. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155(4):581–592. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adamo JE, Rossi G, Brennwald P. The Rho GTPase Rho3 has a direct role in exocytosis that is distinct from its role in actin polarity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1999;10:4121–4133. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robinson NGG, Guo L, Imai J, Toh-E A, Matsui Y, Tamanoi F. Rho3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which regulates the actin cytoskeleton and exocytosis, is a GTPase which interacts with Myo2 and Exo70. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19(5):3580–3587. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu H, Turner C, Gardner J, Temple B, Brennwald P. The Exo70 subunit of the exocyst is an effector for both Cdc42 and Rho3 function in polarized exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21(3):430–442. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roumanie O, Wu H, Molk JN, Rossi G, Bloom K, Brennwald P. Rho GTPase regulation of exocytosis in yeast is independent of GTP hydrolysis and polarization of the exocyst complex. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170(4):583–594. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eitzen G, Thorngren N, Wickner W. Rho1p and Cdc24p act after Ypt7p to regulate vacuole docking. EMBO J. 2001;20(20):5650–5656. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Müller O, Johnson DI, Mayer A. Cdc42p functions at the docking stage of yeast vacuole membrane fusion. EMBO J. 2001;20(20):5657–5665. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Isgandarova S, Jones L, Forsberg D, Loncar A, Dawson J, et al. Stimulation of actin polymerization by vacuoles via Cdc42p-dependent signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282(42):30466–30475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Logan MR, Jones L, Eitzen G. Cdc42p and Rho1p are sequentially activated and mechanistically linked to vacuole membrane fusion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;394(1):64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Donaldson JG, Cassel D, Kahn RA, Klausner RD. ADP-ribosylation factor, a small GTP-binding protein, is required for binding of the coatomer protein beta-COP to Golgi membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89(14):6408–6412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonifacino JS, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Coat proteins: shaping membrane transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4(5):409–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garcia-Mata R, Sztul E. The membrane-tethering protein p115 interacts with GBF1, an ARF guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(3):320–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tisdale EJ, Bourne JR, Khosravi-Far R, Der CJ, Balch WE. GTP-binding mutants of rabl and rab2 are potent inhibitors of vesicular transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119(4):749–761. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones S, Jedd G, Kahn RA, Franzusoff A, Bartolini F, Segev N. Genetic interactions in yeast between Ypt GTPases and Arf guanine nucleotide exchangers. Genetics. 1999;152(4):1543–1556. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Monetta P, Slavin I, Romero N, Alvarez C. Rab1b interacts with GBF1 and modulates both ARF1 dynamics and COPI association. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18(7):2400–2410. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-11-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Komatsu M, Ruoslahti E. R-Ras is a global regulator of vascular regeneration that suppresses intimal hyperplasia and tumor angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 2005;11(12):1346–1350. doi: 10.1038/nm1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang Z, Vuori K, Wang H, Reed JC, Ruoslahti E. Integrin activation by R-ras. Cell. 1996;85(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Keely PJ, Rusyn EV, Cox AD, Parise LV. R-Ras signals through specific integrin alpha cytoplasmic domains to promote migration and invasion of breast epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 1999;145(5):1077–1088. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holly SP, Larson MK, Parise LV. The unique N-terminus of R-ras is required for Rac activation and precise regulation of cell migration. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16(5):2458–2469. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ada-Nguema AS, Xenias H, Hofman JM, Wiggins CH, Sheetz MP, Keely PJ. The small GTPase R-Ras regulates organization of actin and drives membrane protrusions through the activity of PLCepsilon. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt. 7):1307–1319. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goldfinger LE, Ptak C, Jeffery ED, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Ginsberg MH. RLIP76 (RalBP1) is an R-Ras effector that mediates adhesion-dependent Rac activation and cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 2006;174(6):877–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]