Synopsis

Delirium is defined as an acute change in cognition that cannot be better accounted for by a preexisting or evolving dementia. This form of organ dysfunction commonly occurs in older emergency department (ED) patients and is associated with a multitude of adverse patient outcomes. Consequently, delirium should be routinely screened for in older ED patients. Once delirium is diagnosed, the ED evaluation should focus on searching for the underlying etiology. Infection is one of the most common precipitants of delirium, but multiple etiologies may exist concurrently.

Keywords: delirium, emergency department, epidemiology, diagnosis, management

Introduction

Delirium is an under recognized public health problem that affects 7% – 10% of older emergency department (ED) patients.1–3 This form of organ failure has devastating consequences for older patients and poses a significant threat to their quality of life. It has been associated with higher death rates,4, 5 accelerated functional and cognitive decline,6–8 and longer hospital length of stays.9, 10 Delirium also places a tremendous financial burden on the United States health care system, costing over an estimated $100 billion in direct and indirect charges.11, 12

Despite its negative consequences, delirium is frequently missed by emergency physicians,1, 3 and this is a serious quality of care issue.13 Currently, 20 million older Americans visit the ED each year,14–16 and are the fastest growing users.14, 17 With the elderly population expected to grow exponentially over the next several decades, delirium’s burden on EDs will intensify.18 Therefore, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Geriatrics Task Force has recommended that delirium screening in the ED be one of the key quality indicators for emergency geriatric care.19 Given this urgency, the purpose of this review is to discuss delirium’s definition, risk factors, and consequences in older ED patients, and also discuss its diagnosis and management in the ED setting.

Definition of Delirium

Delirium is defined as an acute change in cognition that cannot be better accounted for by preexisting or evolving dementia.20 This change in cognition is rapid, occurring over a period of hours or days, and is classically described as reversible. Patient’s with delirium typically have inattention, disorganized thinking, altered level of consciousness (somnolent or agitated), and perceptual disturbances.20

Delirium is classified into three psychomotor subtypes: hypoactive, hyperactive, and mixed.21 Hypoactive delirium is described as “quiet” delirium and is characterized by decreased psychomotor activity. These patients can appear depressed, sedated, somnolent, or even lethargic. Conversely, patients with hyperactive delirium have increased psychomotor activity and they appear restless, anxious, agitated, and even combative. Patients with mixed-type delirium exhibit fluctuating levels of psychomotor activity (hypoactive and hyperactive) over a period of time. Several epidemiological studies have investigated the frequency in which different psychomotor subtypes occur in a wide variety of settings (Table 1); hypoactive delirium and mixed-type delirium appear to be the predominant subtypes in older patients.22–27 In the ED setting, Han et al. observed 96% of older patients with delirium exhibited the hypoactive or mixed subtype.3

Table 1.

Studies that have evaluated the psychomotor subtypes of delirium.

| Author | Age Inclusion | Setting | Psychomotor Subtype

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypo | Hyper | Mixed | |||

|

| |||||

| Han 20093 | ≥ 65 | ED | 92% | 4% | 4% |

|

| |||||

| Liptzkin 199223 | >65 | Inpatient, medical | 19% | 15% | 52% |

|

| |||||

| O’keefe 199924 | Not reported | Inpatient, geriatrics | 29% | 21% | 43% |

|

| |||||

| Marcanontio 200226 | ≥ 65 | Inpatient, hip fracture repair | 71% | - | 29% |

|

| |||||

| Kelly 200125 | Nursing Home | Inpatient, geriatrics | 56% | 3% | 41% |

|

| |||||

| Peterson et al. 200622 | None | Inpatient, Medical ICU | 44% | 2% | 55% |

|

| |||||

| Pandharipande et al. 200927 | Non | Inpatient, | |||

| Surgical ICU | 64% | 9% | 0% | ||

| Trauma ICU | 60% | 6% | 1% | ||

Hypo, hypoactive; hyper, hyperactive; ICU, intensive care unit; ED, emergency department.

Each psychomotor subtype is hypothesized to have a different underlying pathophysiological mechanism and underlying etiology.21, 28 For example, delirium caused by alcohol withdrawal is more likely to be the hyperactive subtype, whereas delirium caused by a metabolic derangement is more likely to be the hypoactive subtype.29 Not surprisingly, the various psychomotor subtypes of delirium have a differential effect on clinical course and outcomes,30, 31 and also affect recognition by health care providers. Hyperactive delirium is more easily recognized. On the contrary, hypoactive delirium is often undetected because of its subtle clinical presentation, 32 and is often ascribed to other etiologies such as depression or fatigue.33

The Distinction between Delirium and Dementia

Delirium and dementia both cause cognitive impairment, and health care providers often confuse these two distinct clinical entities. This confusion is exacerbated by the high frequency in which delirium is superimposed upon dementia,34 which is why delirium is often missed in these patients.35 However, there are several key distinguishing features between delirium and dementia (Table 1), and most delirium assessments capitalize upon these differences. Unlike delirium, dementia is characterized by a gradual decline in cognition occurring over months or years, and is usually irreversible. Altered level of consciousness, inattention, perceptual disturbances and disorganized thinking are not commonly observed in patients with dementia.

However, there are some instances when the clinical features of delirium and dementia overlap, making them difficult to distinguish from each other. This is especially the case in patients with severe or end-stage dementia, where they can exhibit symptoms of inattention, perceptual disturbance, disorganized thinking, and altered level of consciousness even in the absence of delirium. When these patients develop delirium, an acute change in mental status is usually observed and any pre-existing abnormalities with inattention, disorganized thinking, or level of alertness may worsen. This is why establishing their baseline mental status is crucial to diagnosing delirium in patients with severe dementia.

Though classically thought of as irreversible, there are certain circumstances in which dementia may be reversible. Hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, normal pressure hydrocephalus, and depression are examples of illnesses that can cause reversible dementia or a dementia-like illness (pseudodementia). However, the cognitive decline observed in reversible dementia is usually gradual as opposed to the rapid cognitive decline seen in delirium. Conversely, there is also a proportion of patients whose delirium is not transient; their symptoms can persist for months or even years.36, 37

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) deserves special mention because it can be very difficult to distinguish from delirium. DLB is the second most common subtype of dementia (after Alzheimer’s) and affects15–25% of elderly demented patients.38 Similar to delirium, DLB is characterized by a rapid decline and fluctuation in cognition, attention, and level of consciousness. Such fluctuations can be observed over several hours or days. Like delirium, perceptual disturbances are frequently observed in patients with Lewy body dementia. In contrast to delirium, however, patients with DLB have Parkinsonian motor symptoms, such as cog wheeling, shuffling gait, stiff movements, and reduced arm-swing during walking. Nevertheless, differentiating between DLB and delirium can be difficult in the ED and may require a detailed evaluation by a psychiatrist or neurologist.

Etiology of Delirium

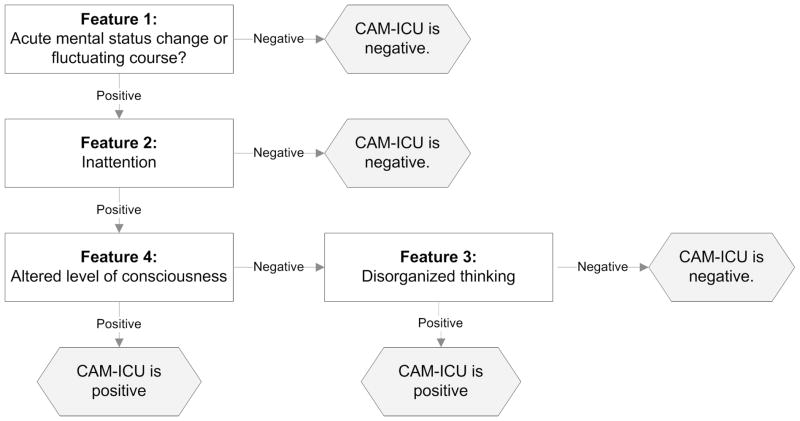

Delirium is often the initial manifestation of an underlying acute illness and can be present before fever, tachypnea, tachycardia, or hypoxia.39 The etiology of delirium is multifactorial and involves a complex interrelationship between patient vulnerability and precipitating factors (Figure 1).40, 41 Patients who are highly vulnerable may be older, have severe dementia, and have multiple comorbidities. In these patients, a relatively benign insult, such as a small dose of narcotic medication, can precipitate delirium. Patients who are less vulnerable to developing delirium, like those who are younger and have little comorbidity burden, require higher doses of noxious stimuli (e.g. severe sepsis) to develop delirium.42 Because older patients are more likely to have multiple vulnerability factors, they are disproportionately more susceptible to becoming delirious compared to younger patients. For this reason, nursing home patients are especially vulnerable.43

Figure 1.

The interrelationship between patient vulnerability and precipitating factors in the development of delirium.41 Patients who have little vulnerability require significant noxious stimuli to develop delirium (black arrow). Conversely, patients who are highly vulnerable require only minor noxious stimuli to develop delirium (gray arrow).

Most of what is known about delirium vulnerability factors is from studies performed in hospitalized patients (Table 3).44–46 There are limited data from the ED, but one study identified dementia, premorbid functional impairment, and hearing impairment as independent risk factors for delirium in the ED.3 Similar observations have been made in the medical and surgical inpatient population.10, 40, 47–49 Dementia is probably the most consistently observed independent vulnerability factor for delirium across different clinical settings.40, 48–55 As the severity of dementia worsens, the risk of developing delirium also increases.56 Other vulnerability factors have also been reported in the hospital literature and include old age,48, 51, 54 high comorbidity burden,55 visual impairment,40 baseline psychoactive drug use such as narcotics, benzodiazepines,10, 48 and medications with anticholinergic properties,51 history of alcohol abuse,50, 55 and malnutrition.41, 57

Table 3.

Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium.

| Predisposing Factors |

Demographics

|

Comorbidity

|

Medications and Drugs

|

Functional Status

|

Sensory Impairment

|

Decreased oral intake

|

Psychiatric

|

| Precipitating Factors |

Systemic

|

Metabolic

|

Medications and Drugs

|

CNS

|

Cardiopulmonary

|

Iatrogenic

|

Numerous precipitating factors of delirium have also been reported in the hospital literature (Table 3). Regardless of what the precipitating factors are, patients with higher severities of illness have a higher likelihood of developing delirium.10, 40, 47, 54 It is important to keep in mind that multiple delirium precipitants can exist concurrently and on occasion, no obvious etiologic agent can be found.58 Infections, such as a urinary tract infection or pneumonia, are one of the most common causes of delirium (34 – 43% of cases).48, 52–54, 59, 60 Dehydration,40 electrolyte abnormalities,10, 61 organ failure,10, 61 drug withdrawal, central nervous system insults,52, 53, 59 and cardiovascular illnesses such as congestive heart failure54 and acute myocardial infarction62 have all been implicated as delirium precipitants. Poorly controlled somatic pain may also cause delirium,48, 63, 64 and pain control with non-narcotic or narcotic analgesia may help resolve delirium in this case.64 Delirium can also be precipitated by iatrogenic events. Inouye et al. observed that the use of physical restraints or bladder catheters, or the addition of more than three medications were associated with delirium development.41

Psychoactive Medications as Risk Factors for Delirium

Medications with anticholinergic properties, benzodiazepines, and narcotics are notorious for precipitating and exacerbating delirium. Such medication risk factors are particularly relevant to the older patient population because polypharmacy is highly prevalent.49 Medications with anticholinergic properties are more frequently associated with delirium than any other drug class.65–67 Over 600 medications with anticholinergic properties exist, and of these, 11% are commonly prescribed to the elderly.68 Some examples of commonly prescribed medications with anticholinergic properties are promethazine, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, meclizine, lomotil, and heterocyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline, doxepin).

Benzodiazepines have also been implicated as common delirium precipitants in hospitalized patients.69–72 However, it is important to emphasize that delirium is heterogeneous and benzodiazepines can have a protective effect in a subgroup of delirious patients. For example, patients who are withdrawing from alcohol or sedatives have improved mortality and morbidity when given benzodiapezpines.73 Narcotic medications are also deliriogenic, 48 and meperidine is a consistently observed culprit.70, 72, 74–76 Similar to benzodiazepines, there is a subgroup of delirious patients who may benefit from narcotic medications. In patients with poor pain control, narcotic analgesia can reduce delirium severity. 64, 65

To illustrate this point, we present a hypothetical case scenario. Mr. B is an 83 year old patient with a past history of dementia, hearing impairment, and depression who presents to an urgent clinic for nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. He takes amitriptyline for his depression and donezepil for his dementia. The patient has normal vital signs, normal physical examination, and unremarkable laboratory workup. The urgent care clinician diagnoses Mr. B with gastroenteritis and prescribes promethazine 25mg tablets for symptomatic relief. Mr. B takes the medication as prescribed and develops a change in acute change mental status 24 hours later, which is subsequently diagnosed as delirium at the local ED.

In this scenario, this was a patient who was highly susceptible to developing delirium and possessed two vulnerability factors (dementia and hearing impairment). In addition, he was already on a medication with anticholinergic properties (amitriptyline) and the addition of promethazine increased the patient’s anticholinergic burden, enough to precipitate delirium. This case illustrates how seemingly benign medications can precipitate delirium in a high risk patient.

The Negative Consequences of Delirium

There is an abundance of hospital-based studies which have investigated delirium’s deleterious effects. From these studies, delirium is a powerful prognostic marker and has been associated with in-hospital and long-term mortality.4, 5, 77–79 Though some have argued that delirium is simply a surrogate for severity of illness and comorbidity burden,80 the relationship between delirium and death has been shown to be independent of these factors.4, 5

Delirium also has a profound impact on the older patient’s quality of life. The trajectory of cognitive decline is accelerated in delirious patients compared non-delirious patients, and this effect is evident in patients with and without preexisting dementia.6, 10, 78, 81, 82 Delirium is also associated with accelerated functional decline,8, 81, 83 which can lead to subsequent loss of independent living and future nursing home placement.8, 77

Hospitalized patients with delirium are more prone to developing urinary incontinence, decubitus ulcers, and malnutrition.11, 12, 51, 84 This can then lead to prolonged hospital stays and increased health care costs.10, 55, 84, 85 Once discharged from the hospital, delirious patients are more likely to be rehospitalized, further adding to the financial burden.8, 60, 77, 84 Moreover, there is also a huge emotional cost. Many patients are able to recall their experiences with delirium, causing patients and their families significant emotional distress.86, 87

To date, only four delirium outcome studies have been conducted in the ED setting. In 385 older ED patients, Lewis et al. observed that patients with delirium were significantly more likely to die at 3-months (14% versus 8%), but their analysis did not adjust for potential confounders.2 Kakuma et al. studied 107 older patients discharged from the ED and reported that delirium was independently associated with 6-month mortality,88 but this study excluded patients who were admitted to the hospital. Han et al. studied 303 older ED patients that were both admitted and discharged.89 They found that patients who were delirious in the ED were more likely to die at 6-months compared to non-delirious patients (36% versus 10%). This relationship was independent of age, comorbidity burden, and severity of illness.89 However, they did not incorporate other important confounders such as dementia and functional impairment in the multivariable model. Only one ED study has investigated the relationship between delirium and long-term functional outcomes. Vida et al. reported that delirium in the ED was associated with accelerated functional decline at 18-months in patients without pre-existing dementia only.90 However, this association disappeared after adjusting for potential confounders.90 Even with the relatively small number of ED studies and the limited external validity of hospital studies, delirium in the ED appears to be a marker for adverse patient outcomes.

Unrecognized Delirium in the Emergency Department

Despite delirium’s negative consequences, emergency physicians miss 57% to 83% of cases due to lack of appropriate and routine screening. 1–3, 88, 91–93 This quality of care issue extends beyond the ED as similar miss rates have been observed in the hospital setting.32, 94–97 Delirium is more commonly missed in patients with hypoactive symptomotology, who are aged 80 years and older, have visual impairment, or have dementia.32, 35

The consequences of missing delirium in the ED are unclear. However, Kakuma et al. reported that discharged ED patients in whom delirium was missed by the emergency physician were more likely to die at 6-months compared to patients in whom delirium was recognized (30.8% versus 11.8%).88 Though the mechanism for this is uncertain, ED patients with undetected delirium may receive inadequate diagnostic workups, and an underlying life-threatening illness may remain undiagnosed. They may also receive inappropriate interventions such as medications with anticholinergic properties or benzodiazepines. Lastly, delirious patients who are discharged from the ED are less likely to understand their discharge instructions,98 which may lead to non-compliance, recidivism, and increased mortality and morbidity.99, 100

Diagnosing Delirium in the ED

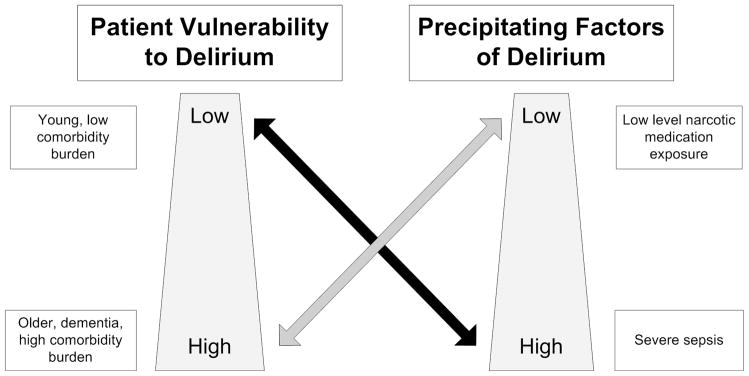

Several delirium assessments exist, but the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is probably the most widely accepted by clinicians. The CAM was developed for non-psychiatrists and is based upon the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised 3rd Edition criteria.101 It consists of four features: 1) acute onset of mental status changes and a fluctuating course, 2) inattention, 3) disorganized thinking, and 4) altered level consciousness.101 A patient must have both features 1 and 2 and either feature 3 or 4 to meet criteria for delirium (Figure 2). The CAM training manual recommends using a cognitive screening test such as the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Digit Span Test to help determine the features of the CAM.102

Figure 2.

Features of the Confusion Assessment Method. A patient must have both features 1 and 2, and either 3 or 4 to meet criteria for delirium.

An acute change in mental status and fluctuating course (feature 1) is a cardinal feature of delirium and must be present for a patient to be CAM positive. In the ED, this feature is determined from interviewing a proxy such as a family member. Feature 1 can be difficult to ascertain if a proxy is not readily available in the ED. If a patient comes from a long-term care facility, contacting the patient’s nurse or physician at that facility can often help establish the patient’s baseline mental status. Similarly, the patient’s primary care provider, if available, is another potential resource. In some patients, an acute change and fluctuation in mental status can be observed first hand during the ED stay.

Features 2, 3, and 4 are assessed during the patient interview and cognitive screen. Similar to feature 1, inattention (feature 2) is considered another cardinal feature of delirium and is described as a patient who is easily distractible and has difficulty maintaining focus. A patient with disorganized thinking (feature 3) may ramble, display tangential thoughts, or demonstrate an illogical flow of ideas. Patients with altered level of consciousness (feature 4) may exhibit drowsiness, lethargy, anxiety, hypervigilance, or combativeness (hyperactive).

Inouye et al. found the CAM to have excellent sensitivity (94% – 100%) and specificity (90% – 95%) in hospitalized patients.101 Subsequent validation studies have shown more variability in diagnostic performances with sensitivities ranging from 46% to 94% and specificities ranging from 63% to 100%.103 However, this variability is most likely attributable to the level of training.104 The CAM has excellent interobserver reliability (kappa 0.70 – 1.00) when performed by trained personnel.103 Thus far, the CAM is the only delirium assessment validated for use in the ED. Using lay interviewers to perform the CAM and a geriatrician’s assessment as the reference standard, Monette et al. observed that the CAM was 86% sensitive and 100% specific in ED patients. They also reported that the CAM had excellent interobserver reliability (kappa = 0.91) in this setting.105

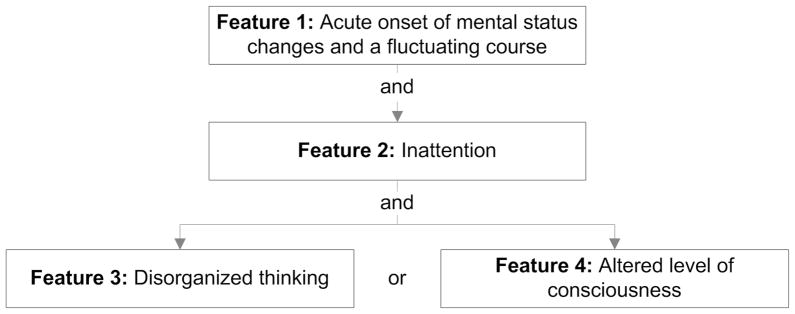

However, the CAM takes up to 10 minutes to perform,102 which can be challenging in a highly demanding ED environment. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) may be more feasible in the ED because it takes less than two minutes to perform. The CAM-ICU primarily uses the same the same four features as the CAM: 1) acute onset of mental status changes or a fluctuating course, 2) inattention, 3) altered level consciousness, and 4) disorganized thinking. Similar to the CAM, a patient must have both features 1 and 2, and either feature 3 or 4 to meet criteria for delirium. However, there are several notable differences between these two assessments. The CAM-ICU uses brief neuropsychiatric screening assessments to test for inattention and disorganized thinking. These screening assessments help minimize subjectivity and improve its ease of use. The CAM-ICU also slightly modifies the original CAM’s feature 1, requiring either an acute change in mental status or fluctuating course.106 In the latest iteration, the CAM-ICU also reorders features 3 and 4 of the CAM; the CAM-ICU’s feature 3 is altered level of consciousness and feature 4 is disorganized thinking. The rationale for this change is detailed in the next paragraph. Lastly, the CAM-ICU also uses the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale to help determine altered level of consciousess.106

Testing all four features of the CAM-ICU typically takes less than two minutes to perform. However, using the algorithm provided in Figure 3, the CAM-ICU can take less than 1 minute to perform in many cases. This algorithm provides a stepwise approach to performing the CAM-ICU and allows the rater to stop the assessment early, especially if either feature 1 (acute change in mental status or fluctuating course) or feature 2 (inattention) is negative. Disorganized thinking (CAM-ICU’s feature 4) is performed only if features 1 and 2 are both positive, and there is no evidence of any altered level of consciousness (CAM-ICU’s feature 3). Because the majority of CAM-ICU positive patients has altered mental status or a fluctuating course, inattention, and altered level consciousness, disorganized thinking (CAM-ICU’s feature 4) is usually not assessed in the clinical setting. For this reason, the latest version of the CAM-ICU reverses the order of the original CAM’s features 3 and 4 as described in the previous paragraph.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for performing the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) in the clinical setting. The shaded hexagons indicate a stopping point for the CAM-ICU.

The CAM-ICU has been validated in mechanically ventilated and non-mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Ely et al. reported that the CAM-ICU was highly sensitive (93% – 100%) and specific (89–100%) with excellent interrater reliability (kappa= 0.84 to 0.96) between nurses and physicians.107, 108 However, the CAM-ICU has not been validated in the ED patients and spectrum bias may exist. A validation study in the ED setting is currently ongoing.

Several other delirium instruments exist in the literature (Table 4). Similar to the CAM, these instruments require subjective assessments and many take up to 10 minutes to complete, making them difficult to perform in the ED.109–122 However, the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESc) may be potentially useful in the ED because it takes less than two minutes to perform. The NuDESc is a checklist that asks nurses about the presence of disorientation, inappropriate behavior, inappropriate communication, hallucinations, and the presence of psychomotor retardation over an 8-hour shift.113 However, the NuDESc does not assess for an acute change in mental status or fluctuating course and inattention, which are cardinal to the diagnosis of delirium. Despite this, the NuDESc appears to have excellent diagnostic characteristics. Using the CAM as the reference standard, Gaudreau et al. reported the NuDESc to be 86% sensitive and 87% specific.113 Radtke et al. observed that the NuDESc was 95% sensitive and 87% specific compared to a research assistant’s assessment using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition criteria.112 The NuDESc’s interrater and interobserver reliability are unknown and will be important to elucidate given its use of subjective observations. Similar to the CAM-ICU, the NuDESc still requires validation in the ED setting.

Table 4.

Other delirium assessments.

| Delirium Instrument | Duration or items | Interrater reliability | Reference Standard | Validated in ED? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium Rating Scale – Revised 98118 | 15 – 30 minutes | Excellent | DSM-IV by psychiatrist | No |

| Delirium Symptom Interview119 | 15 minutes | Excellent | Psychiatrist or Neurologist | No |

| Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale120 | 10 items | Excellent | DSM-IIIR/IV by psychiatrist | No |

| Confusional State Examination122 | 22 items | Moderate to excellent | Psychiatrist | No |

| * Confusion Rating Scale110, 111 | 2 minutes | Unknown | CAM, SPMSQ | No |

| * Nursing Delirium Screening Scale112, 113 | 2 minutes | Unknown | CAM, DSM-IV by research assistant | No |

| * NEECHAM Confusion Scale114–116 | 10 minutes | Excellent | DSM-III by research nurse/CAM | No |

These instruments were developed specifically for nurses.

Diagnostic Evaluation for Delirium in the ED

Once delirium is detected in the ED, the diagnostic evaluation should be focused on uncovering the underlying etiology. Though infection is the most common etiology of delirium in the older ED patient, life threatening causes should initially be considered and can recalled using the mnemonic device “WHHHHIMPS” (Table 5).123 After these life threatening causes have been considered, the ED evaluation can focus on ruling out other causes of delirium listed in Table 3.

Table 5.

Life-threatening causes of delirium.123

| Wernicke’s disease |

| Hypoxia |

| Hypoglycemia |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy |

| Hyperthermia or hypothermia |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| Meningitis/encephalitis |

| Poisoning (whether exogenous or iatrogenic) |

| Status epilepticus |

The ED evaluation of the delirious patient is summarized in Table 6. If available, obtaining a detailed history from a proxy is crucial. A careful review of the patient’s home medication list should also be performed, including eliciting a history of any recent changes or additions to the patient’s home medication regimen. Because alcohol and benzodiazepine abuse can still occur in elderly patients, a careful social history should also be obtained.

Table 6.

Evaluation of the older emergency department patient with delirium.

| History | Careful review of home medications Recent changes in home medications History of drug and alcohol abuse |

| Physical Examination | Vital signs Signs of infection Toxidromes Volume status Neurologic examination |

| Laboratory tests to consider | Urinalysis Blood glucose Electrolytes Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine Liver function tests and/or ammonia Thyroid stimulating hormone Arterial blood gas if hypercarbia is suspected Cardiac biomarkers if AMI is suspected Lumbar puncture if meningitis is suspected Urine drug screen |

| Radiological Tests to Consider | Chest x-ray Computed tomography of the head |

| Other Tests to Consider | 12-lead electrocardiogram |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

The physical examination should look for any vital sign abnormalities, although they will be normal in most cases. A neurological examination should be performed looking for any focal neurological findings suggestive of a central nervous system insult. Laboratory and radiologic tests are commonly performed in all patients with delirium (Table 6). A urinalysis should be performed in all patients as urinary tract infections are common amongst delirious patients.. Electrolytes should be obtained to rule out hyper- or hyponatremia, or hypercalcemia. Because organ failure can precipitate delirium, a blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine should be obtained to rule out uremia. Liver function tests and ammonia levels can also be considered, especially in patients with physical findings of end stage liver disease. Because thyroid dysfunction can cause delirium,124 thyroid stimulating hormone should also be considered. An arterial or venous blood gas may be obtained if hypercarbia is suspected, especially in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rarely, patients with acute myocardial infarction can also present with delirium as the sole manifestation;62 a 12-lead electrocardiogram and cardiac biomarkers can be considered, but their diagnostic yield in ED patients with delirium remains unknown. A lumbar puncture, though not routinely performed, should be considered if there is a clinical suspicion for meningitis/encephalitis and especially if no other etiologies for delirium are found.

A chest x-ray should also be considered to rule out pneumonia, especially in the setting of hypoxemia, tachypnea, or a history of cough and dyspnea. Performing computed tomography (CT) of the head in all delirious patients is controversial as it may have low diagnostic yield.125 However, it may be ordered when no other cause for delirium is found. Based upon two studies, the head CT’s diagnostic yield is increased when performed in patients with impaired level consciousness, a focal neurological defecit, or a recent history of a fall or head trauma.125, 126 However, these studies were retrospective in nature and have yet to prospectively validated. Regardless, clinical judgment should be used when deciding if a delirious patient needs a head CT.

Disposition

There is little evidence based guidance regarding the disposition of older ED patients with delirium. However, admission of delirious patients is likely warranted in most cases. Older delirious patients who are discharged from the ED have higher death rates compared to non-delirious patients, and this effect is magnified when delirium is unrecognized by the emergency physician.88 In addition, delirious patients may be more likely to return to the ED and be hospitalized.1 For a small minority, ED discharge can be considered, particularly if close home supervision and follow-up can be arranged. For example, a patient who accidentally overdoses on a narcotic medication can be discharged home if the delirium resolves and if the patient remains delirium free after a period of ED observation. If admitted to the hospital, admission to an inpatient unit that specializes in geriatric care is preferable as it may improve patient outcomes.127 Regardless of the patient’s disposition, if delirium is detected in the ED, this should be communicated to the physician at the next stage of care.

Pharmacologic Management of Delirium

The single most effective treatment for delirium is to diagnose and treat the underlying etiology. Adjunct pharmacologic treatments have been investigated for delirium, but most studies are limited by their non-blinded trial design, poor randomization, or inadequate power. The American Psychiatry Association recommends avoiding benzodiazepines as monotherapy in delirious patients, except in the setting of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal.45 As previously mentioned, benzodiazepines can precipitate and exacerbate delirium in most cases and they also have relatively high side effect profiles. One randomized trial attempted to compare the efficacy of antipsychotic medications and lorazepam in delirious patients, but was prematurely terminated because the lorazepam arm showed a higher prevalence of treatment limiting side effects such as over-sedation, disinhibition, ataxia, and increased confusion.128

Instead, antipsychotic medications should be used, especially in delirious patients with behavioral disturbances, agitation, and overt psychotic manifestations (i.e. visual hallucinations and delusions). Haloperidol is a commonly used typical antipsychotic and has been shown to improve delirium severity; Hu et al. compared haloperidol to placebo, and reported that 70.4% of patients who received haloperidol showed improvement in their delirium severity at the end of one week compared to 29.7% of the placebo group.129 Intravenous haloperidol should be used cautiously because torsades de point has been reported when given in this formulation.130

Atypical antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine and risperidone are also frequently used to treat patients with delirium.131 Compared to typical antipsychotics, this class of medications have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects.132 Olanzapine has been shown to improve delirium severity compared to placebo in one randomized control trial,129 but it’s efficacy may be attenuated in patients aged 70 years and older.133 Risperdone has also been used to treat delirium, but only one clinical trial has been conducted to date. Han et al. compared risperidone to haloperidol and they observed that 75% of the haloperidol group versus 42% of the risperidone group showed improvement in their delirium severity. However, this difference was non-significant and the trial was underpowered.134 Some studies have used quetiapine to treat delirium,131, 135, 136 but no randomized control trials have been performed.

There are limited data on the effectiveness of typical and atypical antipsychotic medications in patients with different delirium subtypes; their use in patients with hypoactive delirium is controversial. However, a significant proportion of patients with hypoactive delirium will have some element of psychosis.23 For many psychiatrists, when delirium is detected, an antipsychotic is initiated regardless of the subtype.137

Similar to benzodiazepines, medications with anticholinergic properties should be avoided. Narcotic medications should not be used to sedate an agitated patient and should only be used to treat acute pain. Although rare, there are reports of histamine-2 blockers, such as famotidine, ranitidine, and cimetidine, causing delirium.138, 139 These should be avoided in delirious patients if at all possible.

Non-Pharmacologic Management of Delirium

Several non-pharmacologic delirium interventions have been developed for the in-hospital setting and may be tailored for the ED. Most of these non-pharmacologic interventions contain multiple components and involve a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, and social workers or case managers.140, 141 Moreover, geriatricians or geriatric psychiatrists are commonly consulted for these interventions.140–142

These interventions usually emphasize decreased use of psychoactive medications, increased mobilization by reducing the use of physical restraints and bladder catheters, and minimized disruptions in normal sleep-wake cycles. Many also encourage reorienting the patient by placing a large white board with the day and date, large clocks, or calendars in the patients’ rooms. Cognitive stimulation, placing familiar objects in the patient’s room as well as encouraging the presence of family members are also advocated. Though these delirium interventions have shown to be beneficial in the post-operative setting,141, 143 their efficacy in medical patients is equivocal.140, 144 In medical inpatients, Pitkala et al. did find that their non-pharmacologic intervention improved delirium resolution during hospitalization and cognition at six months, but no improvement in nursing home placement or mortality was observed.145 Additional research is required to determine if non-pharmacologic interventions are feasible and cost-effective in the ED setting.

Conclusion

Delirium is common in older ED patients and its etiology is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay between patient vulnerability and precipitating factors. Based upon numerous hospital studies and a limited number of ED studies, delirium has devastating effects on the patient’s well being. As a result, delirium surveillance should be routinely performed in older ED patients, especially those at high risk. The CAM is the only delirium assessment validated for the ED and it has excellent diagnostic characteristics. However, it can take up to 10 minutes to complete and may be difficult to perform in the demanding ED environment. The CAM-ICU and NuDESc take less than two minutes to perform and may be more feasible to perform in the ED. However, they still require validation in the ED population. Once delirium is detected in the ED, the primary goal is to find and treat the underlying cause. Other adjunct pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions have been studied in the hospital setting, but their efficacy is equivocal and their usefulness in the ED setting is unknown. Indeed, significant knowledge gaps exist in regards to the optimal diagnostic evaluation, disposition, and management of delirious ED patients. Given the impending exponential growth of the elderly patient population, intense research efforts to ameliorate these deficiencies are needed.

Table 2.

Differences between delirium and dementia.

| Characteristic | Delirium | Dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Rapid over a period of hours or days | Gradual over a long period of time |

| Course | Fluctuating | Stable |

| Is cognitive decline reversible? | Yes | No |

| Altered of level of consciousness? | Yes | * No |

| Inattention present? | Yes | * No |

| Disorganized thinking present? | Yes | * No |

| Altered perception present? | Yes | * No |

May be present in patients with severe dementia.

Acknowledgments

Jin H. Han and Amanda Wilson were supported in part by the Emergency Medicine Foundation Grant Career Development Award. Dr. Wes Ely was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health AG01023 and the Veterans Affairs Tennessee Valley Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (GRECC).

Contributor Information

Jin Ho Han, Department of Emergency Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Amanda Wilson, Departments of Psychiatry and Emergency Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

E. Wesley Ely, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

References

- 1.Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Smith MD, et al. The effect of mental status screening on the care of elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(5):678–684. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis LM, Miller DK, Morley JE, et al. Unrecognized delirium in ED geriatric patients. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13(2):142–145. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han JH, Zimmerman EE, Cutler N, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(3):193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–1762. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):457–463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, et al. Delirium in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and functional status: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):575–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson JC, Gordon SM, Hart RP, et al. The association between delirium and cognitive decline: a review of the empirical literature. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14(2):87–98. doi: 10.1023/b:nerv.0000028080.39602.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, et al. Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three-site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):234–242. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(12):1892–1900. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1132-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor WN. A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1990;263(8):1097–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4):955–962. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000119429.16055.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders AB. Missed delirium in older emergency department patients: a quality-of-care problem. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):338–341. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCaig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2002 emergency department summary. Adv Data. 2004;(340):1–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strange GR, Chen EH, Sanders AB. Use of emergency departments by elderly patients: projections from a multicenter data base. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(7):819–824. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wofford JL, Schwartz E, Timerding BL, et al. Emergency department utilization by the elderly: analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(7):694–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roskos E, Wilber S. The Effect of Future Demographic Changes on Emergency Medicine Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;48(4 Supplement):65–65. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 18.He W, Sengupta M, Velkoff VA, et al. U.S Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P23–209, 65+ in the United States: 2005. U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terrell KM, Hustey FM, Hwang U, et al. Quality indicators for geriatric emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(5):441–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meagher DJ, Trzepacz PT. Motoric subtypes of delirium. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5(2):75–85. doi: 10.153/SCNP00500075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson JF, Pun BT, Dittus RS, et al. Delirium and its motoric subtypes: a study of 614 critically ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liptzin B, Levkoff SE. An empirical study of delirium subtypes. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:843–845. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Keeffe ST. Clinical subtypes of delirium in the elderly. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):380–385. doi: 10.1159/000017174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly KG, Zisselman M, Cutillo-Schmitter T, et al. Severity and course of delirium in medically hospitalized nursing facility residents. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(1):72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcantonio E, Ta T, Duthie E, et al. Delirium severity and psychomotor types: their relationship with outcomes after hip fracture repair. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):850–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Motoric subtypes of delirium in mechanically ventilated surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(10):1726–1731. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0687-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross CA. CNS arousal systems: possible role in delirium. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):353–371. doi: 10.1017/s1041610291000819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross CA, Peyser CE, Shapiro I, et al. Delirium: phenomenologic and etiologic subtypes. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):135–147. doi: 10.1017/s1041610291000613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Keeffe ST, Lavan JN. Clinical significance of delirium subtypes in older people. Age Ageing. 1999;28(2):115–119. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiely DK, Jones RN, Bergmann MA, et al. Association between psychomotor activity delirium subtypes and mortality among newly admitted post-acute facility patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(2):174–179. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, et al. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467–2473. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.20.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholas LM, Lindsey BA. Delirium presenting with symptoms of depression. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(5):471–479. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71628-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1723–1732. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fick D, Foreman M. Consequences of not recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia in hospitalized elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26(1):30–40. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20000101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marcantonio ER, Simon SE, Bergmann MA, et al. Delirium symptoms in post-acute care: prevalent, persistent, and associated with poor functional recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):4–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.51002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levkoff SE, Evans DA, Liptzin B, et al. Delirium. The occurrence and persistence of symptoms among elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(2):334–340. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1113–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flaherty JH, Rudolph J, Shay K, et al. Delirium is a serious and under-recognized problem: why assessment of mental status should be the sixth vital sign. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(5):273–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, et al. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):474–481. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275(11):852–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inouye SK. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):393–400. doi: 10.1159/000017177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han JH, Morandi A, Ely W, et al. Delirium in the nursing home patients seen in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(5):889–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pun BT, Ely EW. The importance of diagnosing and managing ICU delirium. Chest. 2007;132(2):624–636. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 Suppl):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fearing MA, Inouye SK. Delirium. In: Blazer DG, Steffens DC, editors. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry. 4. Washington, D. C: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hodkinson HM. Mental impairment in the elderly. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1973;7(4):305–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schor JD, Levkoff SE, Lipsitz LA, et al. Risk factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1992;267(6):827–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, et al. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):204–212. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gustafson Y, Berggren D, Brannstrom B, et al. Acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(6):525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jitapunkul S, Pillay I, Ebrahim S. Delirium in newly admitted elderly patients: a prospective study. Q J Med. 1992;83(300):307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolbeinsson H, Jonsson A. Delirium and dementia in acute medical admissions of elderly patients in Iceland. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87(2):123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rockwood K. Acute confusion in elderly medical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(2):150–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb05874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pompei P, Foreman M, Rudberg MA, et al. Delirium in hospitalized older persons: outcomes and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(8):809–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voyer P, Cole MG, McCusker J, et al. Prevalence and symptoms of delirium superimposed on dementia. Clin Nurs Res. 2006;15(1):46–66. doi: 10.1177/1054773805282299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bourdel-Marchasson I, Vincent S, Germain C, et al. Delirium symptoms and low dietary intake in older inpatients are independent predictors of institutionalization: a 1-year prospective population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(4):350–354. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.4.m350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koponen H, Stenback U, Mattila E, et al. Delirium among elderly persons admitted to a psychiatric hospital: clinical course during the acute stage and one-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79(6):579–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahkonen T, Makela H, Paanila S, et al. Delirium in elderly people without severe predisposing disorders: etiology and 1-year prognosis after discharge. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(4):473–481. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.George J, Bleasdale S, Singleton SJ. Causes and prognosis of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a district general hospital. Age Ageing. 1997;26(6):423–427. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.6.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Foreman MD. Confusion in the hospitalized elderly: incidence, onset, and associated factors. Res Nurs Health. 1989;12(1):21–29. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770120105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bayer AJ, Chadha JS, Farag RR, et al. Changing presentation of myocardial infarction with increasing old age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(4):263–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb04221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lynch EP, Lazor MA, Gellis JE, et al. The impact of postoperative pain on the development of postoperative delirium. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(4):781–785. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaurio LE, Sands LP, Wang Y, et al. Postoperative delirium: the importance of pain and pain management. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(4):1267–1273. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000199156.59226.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caeiro L, Ferro JM, Claro MI, et al. Delirium in acute stroke: a preliminary study of the role of anticholinergic medications. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11(10):699–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tune LE, Egeli S. Acetylcholine and delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):342–344. doi: 10.1159/000017167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beresin EV. Delirium in the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1988;1(3):127–143. doi: 10.1177/089198878800100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tune LE. Anticholinergic effects of medication in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62 (Suppl 21):11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foy A, O’Connell D, Henry D, et al. Benzodiazepine use as a cause of cognitive impairment in elderly hospital inpatients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(2):M99–106. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.2.m99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcantonio ER, Juarez G, Goldman L, et al. The relationship of postoperative delirium with psychoactive medications. JAMA. 1994;272(19):1518–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rogers MP, Liang MH, Daltroy LH, et al. Delirium after elective orthopedic surgery: risk factors and natural history. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1989;19(2):109–121. doi: 10.2190/2q3v-hyt4-nn49-bpr4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pandharipande P, Shintani A, Peterson J, et al. Lorazepam is an independent risk factor for transitioning to delirium in intensive care unit patients. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, et al. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(13):1405–1412. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.13.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adunsky A, Levy R, Heim M, et al. Meperidine analgesia and delirium in aged hip fracture patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35(3):253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, et al. Relationship Between Pain and Opioid Analgesics on the Development of Delirium Following Hip Fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):M76–81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dubois MJ, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1297–1304. doi: 10.1007/s001340101017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, et al. Prognostic significance of delirium in frail older people. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19(2–3):158–163. doi: 10.1159/000082888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rockwood K, Cosway S, Carver D, et al. The risk of dementia and death after delirium. Age Ageing. 1999;28(6):551–556. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, et al. Days of Delirium are Associated with 1-year Mortality in an Older Intensive Care Unit Population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0537OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cole MG, Primeau FJ. Prognosis of delirium in elderly hospital patients. CMAJ. 1993;149(1):41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Francis J, Kapoor WN. Prognosis after hospital discharge of older medical patients with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(6):601–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, et al. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72(18):1570–1575. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a4129a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murray AM, Levkoff SE, Wetle TT, et al. Acute delirium and functional decline in the hospitalized elderly patient. J Gerontol. 1993;48(5):M181–186. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.m181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.O’Keeffe S, Lavan J. The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospital patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(2):174–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thomason JW, Shintani A, Peterson JF, et al. Intensive care unit delirium is an independent predictor of longer hospital stay: a prospective analysis of 261 non-ventilated patients. Crit Care. 2005;9(4):R375–381. doi: 10.1186/cc3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer. 2009;115(9):2004–2012. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):183–194. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kakuma R, du Fort GG, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):443–450. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Han JH, Cutler N, Zimmerman E, et al. Delirium in the emergency department is associated with six month mortality. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(S1):S214. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00339.x. (Abstract) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vida S, Galbaud du Fort G, Kakuma R, et al. An 18-month prospective cohort study of functional outcome of delirium in elderly patients: activities of daily living. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):681–700. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):248–253. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Naughton BJ, Moran MB, Kadah H, et al. Delirium and other cognitive impairment in older adults in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25(6):751–755. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Elie M, Rousseau F, Cole M, et al. Prevalence and detection of delirium in elderly emergency department patients. CMAJ. 2000;163(8):977–981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rockwood K, Cosway S, Stolee P, et al. Increasing the recognition of delirium in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(3):252–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Zyl LT, Davidson PR. Delirium in hospital: an underreported event at discharge. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(8):555–560. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Inouye SK. Delirium in hospitalized older patients: recognition and risk factors. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1998;11(3):118–125. doi: 10.1177/089198879801100302. discussion 157–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gustafson Y, Brannstrom B, Norberg A, et al. Underdiagnosis and poor documentation of acute confusional states in elderly hip fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(8):760–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bryce SN, Han JH, Kripilani S, et al. Cognitive Impairment and Comprehension of Emergency Department Discharge Instructions in Older Patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):S80–81. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Clarke C, Friedman SM, Shi K, et al. Emergency department discharge instructions comprehension and compliance study. Cjem. 2005;7(1):5–11. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500012860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hastings SN, Barrett A, Hocker M, et al. Older patients’ understanding of emergency department discharge information and its relationship with adverse outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(S1):S71. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31820c7678. (Abstract) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Inouye SK. Training Manual and Coding Guide. Yale University School of Medicine; 2003. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, et al. The Confusion Assessment Method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rolfson DB, McElhaney JE, Jhangri GS, et al. Validity of the confusion assessment method in detecting postoperative delirium in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11(4):431–438. doi: 10.1017/s1041610299006043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Monette J, Galbaud du Fort G, Fung SH, et al. Evaluation of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) as a screening tool for delirium in the emergency room. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(1):20–25. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ely EW, Pun BT. The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU Training Manual. Vanderbilt University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370–1379. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–2710. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.21.2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Trzepacz PT, Baker RW, Greenhouse J. A symptom rating scale for delirium. Psychiatry Res. 1988;23(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gagnon P, Allard P, Masse B, et al. Delirium in terminal cancer: a prospective study using daily screening, early diagnosis, and continuous monitoring. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(6):412–426. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Williams MA, Ward SE, Campbell EB. Confusion: testing versus observation. J Gerontol Nurs. 1988;14(1):25–30. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19880101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Radtke FM, Franck M, Schneider M, et al. Comparison of three scores to screen for delirium in the recovery room. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(3):338–343. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gaudreau JD, Gagnon P, Harel F, et al. Fast, systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized patients: the nursing delirium screening scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(4):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Neelon VJ, Champagne MT, Carlson JR, et al. The NEECHAM Confusion Scale: construction, validation, and clinical testing. Nurs Res. 1996;45(6):324–330. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199611000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Champagne MT, Neelon VJ, McConnell ES, et al. The NEECHAM confusion scale: assessing acute confusion in teh hospitalized and nursing home elderly [Abstract] Gerontologist. 1987;27:4A. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Milisen K, Foreman MD, Hendrickx A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Flemish translation of the NEECHAM Confusion Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Trzepacz PT, Dew MA. Further analyses of the Delirium Rating Scale. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17(2):75–79. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(94)00095-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Trzepacz PT, Mittal D, Torres R, et al. Validation of the Delirium Rating Scale-revised-98: comparison with the delirium rating scale and the cognitive test for delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(2):229–242. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Albert MS, Levkoff SE, Reilly C, et al. The delirium symptom interview: an interview for the detection of delirium symptoms in hospitalized patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1992;5(1):14–21. doi: 10.1177/002383099200500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, et al. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Williams MA. Delirium/acute confusional states: evaluation devices in nursing. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3(2):301–308. doi: 10.1017/s1041610291000741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Robertsson B, Karlsson I, Styrud E, et al. Confusional State Evaluation (CSE): an instrument for measuring severity of delirium in the elderly. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:565–570. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Caplan JP, Cassem NH, Murray GB, et al. Delirium. In: Stern TA, editor. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier; 2008. p. xvii.p. 1273. [Google Scholar]

- 124.El-Kaissi S, Kotowicz MA, Berk M, et al. Acute delirium in the setting of primary hypothyroidism: the role of thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Thyroid. 2005;15(9):1099–1101. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Naughton BJ, Moran M, Ghaly Y, et al. Computed tomography scanning and delirium in elder patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(12):1107–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hardy JE, Brennan N. Computerized tomography of the brain for elderly patients presenting to the emergency department with acute confusion. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20(5):420–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Naughton BJ, Saltzman S, Ramadan F, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce prevalence of delirium and shorten hospital length of stay. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(1):18–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):231–237. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Hu H, Deng W, Yang H. A prospective random control study comparison of olanzapine and haloperidol in senile delirium. Chongging Medical Jounral. 2004;8:1234–1237. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hassaballa HA, Balk RA. Torsade de pointes associated with the administration of intravenous haloperidol:a review of the literature and practical guidelines for use. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2003;2(6):543–547. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lee KU, Won WY, Lee HK, et al. Amisulpride versus quetiapine for the treatment of delirium: a randomized, open prospective study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(6):311–314. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ozbolt LB, Paniagua MA, Kaiser RM. Atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of delirious elders. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Breitbart W, Tremblay A, Gibson C. An open trial of olanzapine for the treatment of delirium in hospitalized cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):175–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Han CS, Kim YK. A double-blind trial of risperidone and haloperidol for the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(4):297–301. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(04)70170-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Khouzam HR. Quetiapine in the treatment of postoperative delirium. A report of three cases. Compr Ther. 2008;34(3–4):207–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kim KY, Bader GM, Kotlyar V, et al. Treatment of delirium in older adults with quetiapine. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(1):29–31. doi: 10.1177/0891988702250533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Platt MM, Breitbart W, Smith M, et al. Efficacy of neuroleptics for hypoactive delirium. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6(1):66–67. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Catalano G, Catalano MC, Alberts VA. Famotidine-associated delirium. A series of six cases. Psychosomatics. 1996;37(4):349–355. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71548-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Picotte-Prillmayer D, DiMaggio JR, Baile WF. H2 blocker delirium. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(1):74–77. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Cole MG, McCusker J, Bellavance F, et al. Systematic detection and multidisciplinary care of delirium in older medical inpatients: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2002;167(7):753–759. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, et al. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bailey RF, et al. Systematic intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 1994;151(7):965–970. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gustafson Y, Brannstrom B, Berggren D, et al. A geriatric-anesthesiologic program to reduce acute confusional states in elderly patients treated for femoral neck fractures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(7):655–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Cole MG, Primeau F, McCusker J. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent delirium in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. CMAJ. 1996;155(9):1263–1268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pitkala KH, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, et al. Multicomponent geriatric intervention for elderly inpatients with delirium: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(2):176–181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]