Abstract

Objective

To assess the relationship between unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression.

Design

Secondary analysis of data from a prospective pregnancy cohort.

Setting

The study was performed at the University of North Carolina prenatal care clinics.

Population/Sample

Pregnant women enrolled for prenatal care at the University of North Carolina Hospital Center.

Methods

Participants were questioned about pregnancy intention at 15–19 weeks gestational age, and classified as having an intended, mistimed, or unwanted pregnancy. They were evaluated for postpartum depression at three and twelve months postpartum. Log binomial regression was used to assess the relationship between unintended pregnancy and depression, controlling for confounding by demographic factors and reproductive history.

Main Outcome Measures

Depression at three and twelve months postpartum, defined as Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) score >13.

Results

Data were analyzed for 688 women at three months and 550 women at twelve months. Depression was more likely in women with unintended pregnancies at both three months (RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2, 3.6) and twelve months (RR 3.6, 95% CI 1.8, 7.1). Using multivariable analysis adjusting for confounding by age, poverty and education level, women with unintended pregnancy were twice as likely to have postpartum depression at twelve months (RR 2.0, 95% CI 0.96, 4.0).

Conclusion

While many elements may contribute to postpartum depression, unintended pregnancy could also be a contributing factor. Women with unintended pregnancy may have an increased risk of depression up to one year postpartum.

Keywords: Pregnancy intention, depression, unwanted pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Unintended pregnancy is common; an estimated 49% of all pregnancies in the US each year are unintended. While many such pregnancies end in abortion, about 58% result in live birth. 1 Unintended pregnancy has been linked to poor prenatal care, high risk pregnancy behaviors,2 increased rates of preterm birth and low birth weight,3 poor social outcomes in childhood 4 and increased medical costs.5 The relation between unintended pregnancy and poor neonatal outcomes has been extensively studied, but less is known about the effect of an unintended pregnancy carried to term on the woman herself after the pregnancy.

Several studies have demonstrated that unintended pregnancy is associated with increased risk of maternal postpartum depression,6–9 but these studies have limitations. Most have relied on postpartum recall of pregnancy intention. Longitudinal studies demonstrate that many women will deny that a pregnancy was ever unintended or unwanted after their children are delivered.4, 10 This suggests that recall does not accurately capture how a woman felt about her pregnancy at the time of conception. Therefore, these retrospective studies may underestimate frequency of unintended pregnancy, and may not accurately assess the effect of an unintended pregnancy on maternal well-being. A few studies have collected information about pregnancy intention during the antepartum period, 11–14 but they have limited generalizability. One included only women with a known history of depression or high risk screening; 13 another primarily focused on discordance in partner intentions.14 A third was conducted in Brazil, where abortion is illegal, and this population is likely to be different from that in a place where abortion is legal and available.12

All of these studies also have limited follow-up time at three to six months, which may not give an accurate assessment of long-term well-being. This dearth of longitudinal studies with longer follow-up times represents a lack of knowledge about how an unintended pregnancy may increase risk for postpartum depression. We performed a secondary analysis of data from a prospective cohort of pregnant women to assess the relationship between unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression at three and twelve months.

METHODS

The Pregnancy Infection and Nutrition Study (PIN) was a multi-phase prospective cohort study of pregnant women in North Carolina conducted from 1996–2005. The PIN study’s primary aim was to identify etiologic factors for preterm delivery and related complications of pregnancy. Details of the study enrollment and protocols have been described previously. 15, 16 Between 2001–2005, pregnant women at 15–22 weeks gestational age who were receiving prenatal care at the University of North Carolina Hospital in Chapel Hill were offered enrollment in the PIN3 phase of the study. Women were excluded if they did not speak English, were less than 16 years of age, had multiple gestations, or would not be able to complete telephone follow-up interviews. Out of 3203 eligible participants, 2006 women (63%) were enrolled in PIN3.

A subset of 938 women from PIN3 were offered enrollment in the PIN Postpartum study after their deliveries. Women were eligible for PIN Postpartum if they agreed to be contacted after delivery, lived within a two hour radius of Chapel Hill North Carolina, and who could be reached by phone at approximately six weeks postpartum. Of the 938 eligible women, 688 (73%) agreed to participate and completed a interview in their home at three month postpartum. The women enrolled in PIN Postpartum who did complete this interview were the population for the current study. There were no significant differences in socio-demographic characteristics between women who enrolled in PIN Postpartum and those who were either not eligible or declined to participate. Women who enrolled in the study but who became pregnant prior to the 12- month postpartum visit (n=45) were not followed, since the main focus of PIN Postpartum study was weight retention. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

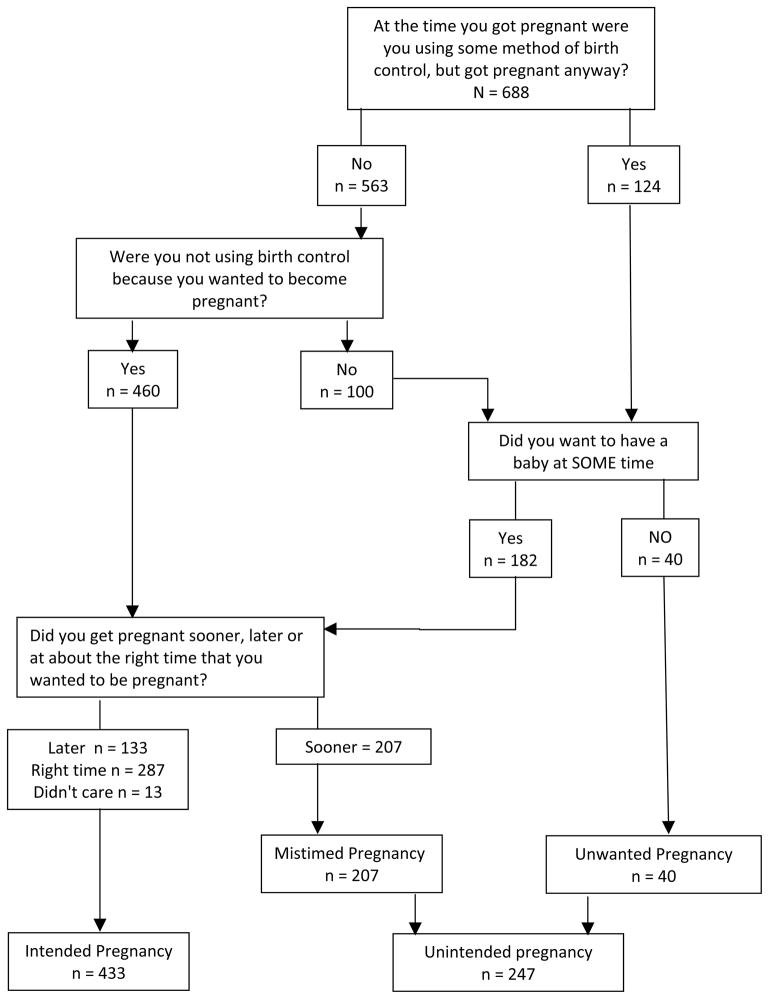

After enrollment in PIN3, demographic information including age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, income level and reproductive history was collected through a telephone interview at 17–21 weeks gestation. Pregnancy intention was assessed with a modified version of the CDC’s Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS) questions. (Figure 1) Women who were attempting pregnancy at the time of conception were defined as having an “intended” pregnancy. Women who were not attempting pregnancy at the time of conception, but who had intended to become pregnant at some future time were defined as having “mistimed” pregnancy. Women who were not attempting pregnancy at the time of conception, and stated they had not intended a pregnancy at any future time were defined as an “unwanted” pregnancy. Mistimed and unwanted pregnancies were classed together in a global category of “unintended” pregnancy as well. After delivery, women enrolled in PIN Postpartum were screened for depression during in-home interviews with the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) at three and twelve months.17

FIGURE 1.

Assessment of Pregnancy Intention

* Lack of additivity represents non-respondents to individual questions

Analyses were performed on data from the subjects who enrolled in the PIN Postpartum study and completed the three-month and twelve month postpartum interview. We examined means, standard deviations and distribution of all continuous variables, and we compared frequencies of categorical variables. We assessed for missing or extreme values and concluded that no imputation was necessary due to minimal missing data. Our primary exposure was pregnancy intention, which was divided into three categories (intended, mistimed, unwanted). Because of the small numbers of women reporting an unwanted pregnancy (6% of the total sample), we also combined mistimed and unwanted pregnancies into a global category of unintended pregnancy in addition to considering the three category exposure. Our primary outcome was depression at three and twelve months postpartum. Women were considered to be depressed with an EPDS score of 13 or higher, as this cut-point is generally accepted to ideally balance sensitivity and specificity of the screening tool. 17, 18

Other possible risk factors for postpartum depression were considered as potential confounders of the pregnancy intention and postpartum depression relationship. Possible confounders were selected based on prior literature and likelihood of relation to either unintended pregnancy or depression (age, race, ethnicity, gestational age, income, education, parity, prior abortion, outcome of index pregnancy). Race/ethnicity was combined into three categories of white, African American, and Hispanic; the small number of participants (n=38) reporting Asian, American Indian or unspecified other ethnicity were excluded whenever race/ethnicity was included in the analysis. Education level was collapsed to two categories of high school graduate or less vs. more than high school. Income was related to federal poverty levels through calculations from reported income and reported household size. Poverty level was considered as both a continuous variable (percentage of federal poverty level accounting for household size) and a categorical variable with <300% federal poverty level as a cutoff for low-income status.

We used log binomial regression models to estimate risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for postpartum depression in women with intended versus unintended pregnancies, adjusted for any confounding factors. Possible confounders were examined for differential distribution in exposure and outcome categories. Those factors which were differentially distributed were considered to have potential to be confounders. Separate models were developed for postpartum depression at three months and at twelve months. A full model was estimated including pregnancy intention, all potential confounders, and interaction terms. After removal of non-significant interaction effects based on likelihood ratio tests, we estimated the risk ratio and 95% confidence interval for postpartum depression between categories of pregnancy intention, adjusted for all potential confounders. We then used a change-in-effect method to determine which variables were confounders and needed to remain in the model.19 The final model retained any factors that changed the pregnancy intention/postpartum risk ratio by >10% when removed. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12 software. (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX 77845 USA.)

RESULTS

The PIN Postpartum study included 688 women. The mean gestational age was 15 weeks at recruitment and 19 weeks at the first phone interview when pregnancy intention was assessed. Three-month EPDS scores were available for all participants. Twelve-month EPDS scores were available for 550 women (80%), and pregnancy intention data were complete for 680 women (99%). Missing data were minimal, and any missing data or data lost to follow-up or study withdrawal were non-differentially distributed by pregnancy intention, postpartum depression, and other variables included in the analyses.

There were 433 women (64%) with an intended pregnancy, 207 with a mistimed pregnancy (30%), and only 40 (6%) with an unwanted pregnancy. With the latter two categories combined, there were 247 women (36%) reporting an “unintended” pregnancy. The overall mean age for the cohort was 29.4 years, although those with unintended pregnancies were somewhat younger that those with intended pregnancies (Table 1). About half of the women with unintended pregnancy had incomes below the 300% poverty level; only 19% of the women with intended pregnancy were in this poverty group. The majority of the cohort was white, but the distribution of race was similar to that of the US population as a whole as described in 2010 Census data20, 21. The unintended pregnancy group had fewer whites than the intended group. The women in the unintended group also were much more likely to be unmarried than in the intended group. Overall, it was a highly educated sample; in the unintended group 70% had more than a high school education and 90% of the intended group had more than high school education. Most women had one or more prior pregnancies, but approximately half were nulliparous. In this study pregnancy, 87% had a term delivery and 99% had a live birth.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics and pregnancy intention

| Characteristic | Overall Sample | By Pregnancy Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| (n=688) | Unintendedǂ (n=247) | Intended (n=433) | |

| Mean Age (years) | 29.4 | 26.8 | 30.9 |

| Mean Gestational Age at 1st interview (days) | 138 | 138 | 137 |

| Mean Income as % of federal poverty level* | 423 | 316 | 483 |

| % with income <300% poverty level* | 31 | 51 | 19 |

| % White | 79 | 68 | 86 |

| % Black | 15 | 26 | 9 |

| % Hispanic | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| % Not married | 20 | 38 | 9 |

| % Education >high school | 82 | 70 | 90 |

| % Primigravid | 32 | 29 | 33 |

| % Nulliparous | 49 | 42 | 54 |

| % Prior spontaneous abortion | 28 | 24 | 30 |

| % Prior induced abortion | 18 | 19 | 16 |

| % Fetal death in study pregnancy | 1 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| % Preterm birth in study pregnancy | 13 | 15 | 11 |

Unintended combines mistimed (n=207) and unwanted (n=40) pregnancies

Income reported at enrollment. Relation to poverty level calculated from income and reported household size

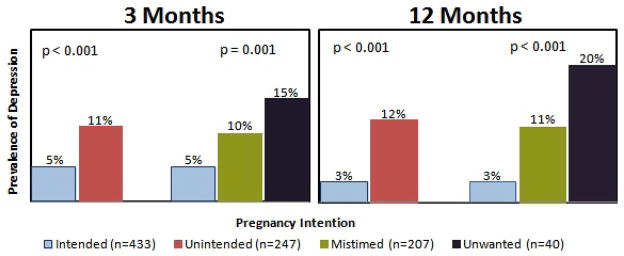

Overall, the prevalence of postpartum depression was low in the sample, with only 7.3% depressed at three months and 6% depressed at twelve months. When pregnancy intention was considered, depression was more common among women with unintended pregnancy than women with intended pregnancy: 11% vs. 5% at three months (p<0.001) and 12% vs. 3% at twelve months (p <0.001). Women with unwanted pregnancy had the highest risk of depression when compared with mistimed and intended pregnancy at both three and twelve months (p <0.00) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of depression by pregnancy intention

Intended pregnancy was the reference group for both the two-level and three-level categorizations of pregnancy intention in the log binomial models. Before adjusting for any potential confounders, women with mistimed, unwanted, and unintended pregnancy had significantly increased risk of postpartum depression at both three months and at twelve months (Table 2). Both mistimed and unwanted pregnancy were associated with an unadjusted higher risk of depression, with the greatest effect sizes seen in unwanted pregnancy compared to intended pregnancy at three months (RR=3.0; 95% CI: 1.3, 6.8) and at twelve months (RR=5.5; 95% CI: 2.1, 14). We then fit sequential log binomial regression models to assess interaction and confounding. Based on the likelihood ratio tests, there were no significant interactions between any variables and pregnancy intention. Age, education level, and poverty status caused a substantive change in the adjusted risk ratios, and therefore were retained in the final models as confounders.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted risk of post-partum depression by pregnancy intention categories

| 3 MONTHS | 12 MONTHS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Pregnancy Intention | Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted* Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

| 3 category | Intended | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mistimed | 1.9 (1.1, 3.4) | 1.1 (0.6, 1.9) | 3.3 (1.6, 6.6) | 1.9 (0.9, 3.9) | |

| Unwanted | 3.0 (1.3, 6.8) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.1) | 5.5 (2.1, 14) | 2.3 (0.8, 6.4) | |

|

| |||||

| 2 category | Intended | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unintendedǂ | 2.1 (1.2, 3.6) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.1) | 3.6 (1.8, 7.1) | 2.0 (0.96, 4.0) | |

Unintended combined mistimed and unwanted pregnancies

Adjusted for age, education, and poverty level

In the adjusted models with the three-category exposure, women with unwanted pregnancies were not significantly more likely to have postpartum depression than women with intended pregnancies at three months postpartum (RR 1.3; 95% CI: 0.5, 3.1). At 12 months, women with unwanted pregnancies were over twice as likely to be depressed compared to women with intended pregnancies (RR 2.3; 95% CI: 0.8, 6.5). For the combined category for unintended pregnancy, at three months women had minimally increased risk of depression compared to intended pregnancy (RR 1.2; 95% CI: 0.6, 2.1). At 12 months postpartum, women with an unintended pregnancy had a two-fold increased risk of depression (RR 2.0; 95% CI 0.96, 4.00).

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

Women with unintended pregnancy had an increased risk of postpartum depression when compared to women with intended pregnancy. The increased risk was highest at 12 months postpartum, when women with unintended pregnancy had a three-fold increased risk of depression and women with an unwanted pregnancy had five times the risk of depression. After adjusting for confounding by age, education and income level, the risk was still increased approximately two-fold for both unwanted pregnancies and combined unintended pregnancies, though the increased risk was of borderline statistical significance.

Overall, prevalence of depression was higher at three months than at twelve months (7.3% vs 6%), and declined from three to twelve months among the intended-pregnancy group (from 5.1% to 3.4%). However, among women with unwanted pregnancy, depression increased between three and twelve months (15.0% vs 19.5%). This suggests that women with an unwanted pregnancy may have a longer-term risk of depression.

Interpretation

Our findings linking postpartum depression to unintended pregnancy in this prospective cohort are similar to those of previous retrospective studies, which have reported an association with significant confounding by socio-economic factors. This study demonstrates an association between postpartum depression and unintended pregnancy. As we lack baseline depression data, it is impossible to state with certainty that this is a causal relationship; it is possible that women with unintended pregnancies had depression that preceded the index pregnancy. Women with pre-existing depression may be more likely to have an unwanted pregnancy; therefore the causality or directionality is difficult to define with certainty. However, the strength of association, a “dose-response” effect (Figure 2), the consistency of the relationship with other retrospective studies, and the plausibility and coherence of the association support the theory of association between unintended pregnancy and post-partum depression.

This pregnancy cohort is a unique population choosing to continue an unintended pregnancy. Abortion is legal and generally accessible where this study is performed; most likely many women with unintended and unwanted pregnancies obtain abortions. Risk of depression is still twice as high among women with unintended pregnancy, even though they decided to continue the pregnancy. Since about 25% of all live births result from unintended pregnancy, even a small increase in risk of depression has significant implications for public health. Outcomes could be worse among women who wished to terminate the pregnancy but were prevented from legally or safely doing so, as one long-term study has reported.4

Strengths and Weaknesses

The PIN Postpartum study has both strengths and limitations. The major limitation is the lack of information on pre-pregnancy depression for the study participants. It is possible that some patients identified in the study as having postpartum depression in fact have pre-existing depression. While we did not have a measure of pre-existing depression, our models were able to adjust for major known risk factors for postpartum depression, including non-white race and low income.

Another potential limitation is the unreliability inherent in the assessment of pregnancy intention. Social-desirability bias may make some women unwilling to honestly state that a current pregnancy is unwanted. While antepartum assessment is closer to the time of conception, it does still involve recall of intentions prior to pregnancy. Recall bias may affect women’s answers, and these estimates may not truly reflect intention prior to conception.

In this study, EPDS was used to assess for depression. The use of a screening scale to define depression could be seen as a limitation. However, most studies of postpartum depression use EPDS screen as a proxy for diagnosis, and in practice many clinicians will treat depression on the basis of the screen alone. Therefore, use of EPDS to define outcome is well within the limits of general research and clinical practice. The EPDS cutoff of 13 has sensitivity and specificity as high as 95% and 93% respectively;18 the lower estimate of positive predictive values is 85%.17 While our analysis is limited by the relatively low rates of depression in the cohort, the EPDS is still a robust tool in low-prevalence populations.

Finally, while the sample size was large, small numbers of unwanted pregnancies and low overall prevalence of depression decreased statistical power in the analysis.

Strengths include the longitudinal study design allowing direct estimation of the risk of depression following an unintended pregnancy carried to term, and this is one of few studies that has assessed pregnancy intention antepartum in the early second trimester. The large cohort with excellent follow-up rates also strengthens our analysis. Finally, the study is strengthened by the length of follow-up. Women were followed for twelve months, providing valuable information about the incidence of depression beyond the immediate postpartum period, which has not been well-documented in prior studies.

CONCLUSION

This study suggests that unintended pregnancy is associated with maternal depression at twelve months postpartum. Unintended pregnancy may have a long term effect on maternal well being, even when the woman chooses to continue the pregnancy. Clinically, providers should consider asking about pregnancy intention at early antepartum visits to screen for unintended pregnancy. Women who report that their pregnancy was unintended or unwanted may benefit from earlier or more targeted screening for depression both during and following pregnancy. Simple, low-cost screening interventions to identify women at risk could allow targeted intervention when appropriate. Timely intervention could potentially prevent complications from future unintended pregnancies and the sequelae of depression. Future research should focus on the complex interaction between social confounders and unintended pregnancy. Further research which addresses pre-pregnancy depression could help illuminate the direction of causality between depression and unintended pregnancy.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTION TO AUTHORSHIP

Rebecca J Mercier: Responsible for study concept, study design, data analysis, drafting of manuscript.

Joanne Garrett: Participated in study design, supervised data analysis and assisted in drafting and revising the manuscript. She has approved the final version of the manuscript.

John Thorp: Was a principal investigator for the parent study and original data collection. For this study he approved the concept and design and participated in revisions of the manuscript. He has approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ana Maria Siega-Riz: Was a principal investigator for the parent study and original data collection. For this study she approved the concept and design, provided data for this analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. She has approved the final version of the manuscript.

DETAILS OF ETHICS APPROVAL

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. Reference number IRB 11-2328.

DISCLOSURE OF INTERESTS

Disclosure of financial support: none

Disclosure of institutional support: The corresponding author is supported by an NIH T-32 grant for clinical research (Grant # T32 HD 40672-11) and the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute. The Institute is supported by grants UL1RR025747, KL2RR025746, and TLRR025745 from the NIH National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Rebecca J. Mercier, Email: rmercier@med.unc.edu, Campus Box 7570, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UNC School of Medicine Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

Joanne Garrett, Email: joanne_garrett@med.unc.edu, Campus Box 7570, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UNC School of Medicine Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

John Thorp, Email: john_thorp@med.unc.edu, Campus Box 7570, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UNC School of Medicine Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

Anna Maria Siega-Riz, Email: am_siegariz@unc.edu, Campus Box 7435, Departments of Epidemiology and Nutrition, UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

References

- 1.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79:194–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, Frick C. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:205–16. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David H. Born Unwanted, 35 Years Later: The Prague Study. Reproductive Health Matters. 2006;14:181–190. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messer LC, Dole N, Kaufman JS, Savitz DA. Pregnancy intendedness, maternal psychosocial factors and preterm birth. Matern Child Health J. 2005;9:403–12. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakku JE, Nakasi G, Mirembe F. Postpartum major depression at six weeks in primary health care: prevalence and associated factors. Afr Health Sci. 2006;6:207–14. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2006.6.4.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owoeye AO, Aina OF, Morakinyo O. Risk factors of postpartum depression and EPDS scores in a group of Nigerian women. Trop Doct. 2006;36:100–3. doi: 10.1258/004947506776593341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karacam Z, Onel K, Gercek E. Effects of unplanned pregnancy on maternal health in Turkey. Midwifery. 2011;27:288–93. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warner R, Appleby L, Whitton A, Faragher B. Demographic and obstetric risk factors for postnatal psychiatric morbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:607–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce T, Kaestner R, Korenman S. The stability of pregnancy intentions and pregnancy-related maternal behaviors. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:171–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1009571313297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, Harlow BL, McLaughlin TJ, Joffe H, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:221–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludermir AB, Araya R, de Araujo TV, Valongueiro SA, Lewis G. Postnatal depression in women after unsuccessful attempted abortion. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198:237–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen AL, Stuart EA, Perry DF, Le HN. Unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression trajectories in low-income, high-risk Hispanic immigrants. Prev Sci. 2011;12:289–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0213-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leathers SJ, Kelley MA. Unintended pregnancy and depressive symptoms among first-time mothers and fathers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:523–31. doi: 10.1037/h0087671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siega-Riz AM, Herring AH, Carrier K, Evenson KR, Dole N, Deierlein A. Sociodemographic, perinatal, behavioral, and psychosocial predictors of weight retention at 3 and 12 months postpartum. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1996–2003. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demissie Z, Siega-Riz AM, Evenson KR, Herring AH, Dole N, Gaynes BN. Physical activity and depressive symptoms among pregnant women: the PIN3 study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:145–57. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris B, Huckle P, Thomas R, Johns S, Fung H. The use of rating scales to identify post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:813–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinbaum DGKM. Logistic Regression: a self-learning text. New York NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed on 1/29/2013];2010 Census Briefs: The Black Population 2010. 2011 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-06.pdf.

- 21.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed on 1/30/2013];2010 Census Briefs: The White Population 2010. 2011 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-05.pdf.