Abstract

Several researchers have suggested that the nature of the covariation between internalizing and externalizing disorders may be understood better by examining the associations between temperament or personality and these disorders. The present study examined neuroticism as a potential common feature underlying both internalizing and externalizing disorders and novelty seeking as a potential broad-band specific feature influencing externalizing disorders alone. Participants were 12- to 18-year-old twin pairs (635 monozygotic twin pairs and 691 dizygotic twin pairs; 48% male and 52% female) recruited from the Colorado Center for Antisocial Drug Dependence. Genetic and nonshared environmental influences shared in common with neuroticism influenced the covariation among distinct internalizing disorders, the covariation among distinct externalizing disorders, and the covariation between internalizing and externalizing disorders. Genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking influenced the covariation among externalizing disorders and the covariation between major depressive disorder and externalizing disorders, but not the covariation among internalizing disorders or between anxiety disorders and externalizing disorders. Also, after accounting for genetic and environmental influences shared in common with neuroticism and novelty seeking, there were no significant common genetic or environmental influences among the disorders examined, suggesting that the covariance among the disorders is sufficiently explained by neuroticism and novelty seeking. We conclude that neuroticism is a heritable common feature of both internalizing disorders and externalizing disorders, and that novelty seeking is a heritable broadband specific factor that distinguishes anxiety disorders from externalizing disorders. Keywords: internalizing, externalizing, neuroticism, novelty-seeking, genetics, environment

The dimensions of internalization and externalization help to define clusters of psychiatric disorders that commonly co-occur (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999; Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003; Krueger, McGue, & Iacono, 2001; Lilienfeld, 2003). However, given the current literature, it is difficult to discern how these two dimensions of disorders are related. On one hand, there is evidence suggesting that internalizing disorders may be a risk factor for externalizing disorders (e.g., Angold et al., 1999; Keiley et al., 2003; Kerr, Tremblay, Pagani-Kurtz, & Vitaro, 1997; Lilienfeld, 2003; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1994; Serbin, Moskowitz, Schwartzman, & Ledingham, 1991), but on the other hand, there is a line of evidence suggesting that internalizing disorders may be a protective factor against externalizing disorders (e.g., Keiley et al., 2003; Quay & Love, 1977; Walker et al., 1991).

One possible way to resolve the contradictions from previous studies examining the relationship between internalizing and externalizing disorders may be to identify both the common risk factors shared by both internalizing and externalizing disorders, and risk factors that are specific to internalizing or externalizing disorders. Weiss, Susser, and Catron (1998) and Lilienfeld (2003) contrasted the difference between common features, which are features that distinguish both externalizing and internalizing disorders from normality, from broad-band specific features, which are features that distinguish externalizing disorders and internalizing disorders.

Lahey and Waldman (2003) proposed examining temperament and personality constructs as potential common and broad-band specific features that may help us distinguish the risk factors that are shared in common between internalizing and externalizing disorders and the risk factors that are specific to externalizing disorders. That is, one possible way to resolve the contradictions from previous studies examining the relationship between internalizing and externalizing disorders may be to examine temperament and personality constructs as precursors of internalizing and externalizing disorders. Several prominent personality researchers have outlined similar theories suggesting that personality or temperament dimensions may be associated with higher or lower prevalence rates for externalizing and internalizing disorders (e.g., Murray & Kochanska, 2002; Pickering & Gray, 1999; Rothbart & Ahadi, 2004). Lahey and Waldman’s (2003) model proposes that negative emotionality (Tellegen, 1982) is a common feature that underlies all forms of psychopathology. Negative emotionality is defined as the proclivity to experience negative emotional states including anger, depression, and anxiety (Miller & Pilkonis, 2006), or the opposite of emotional stability. This construct is often referred to as neuroticism in the literature (Eysenck, Eysenck & Barrett, 1985). In accordance with Lahey and Waldman’s (2003) model, several researchers have found significant associations between neuroticism and both internalizing and externalizing disorders (e.g., Keiley et al., 2003; Khan, Jacobson, Gardner, Prescott, & Kendler, 2005; Lahey, 2009; Prior, Sanson, Smart & Oberklaid, 1999).

As a way to differentiate liability for internalizing disorders and externalizing disorders, Lahey and Waldman (2003) propose examining daring, a construct similar to novelty seeking (e.g., Cloninger, Przybeck & Svrakic, 1991), as a broadband-specific feature (Lilienfeld, 2003; Weiss et al., 1998), suggesting it is a specific risk factor for externalizing disorders that does not influence or may be negatively associated with internalizing disorders. Novelty seeking is characterized by an enthusiastic propensity towards temerarious behaviors, or high adventurousness in the pursuit of enjoyment. It is also inversely related to behavioral inhibition (e.g., Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1988), harm avoidance (Cloninger, 1987), and shyness (e.g., Rowe & Plomin, 1977). Lahey and Waldman’s (2003) hypothesis regarding novelty seeking has been substantiated by several researchers (e.g., Khan et al., 2005; Rettew, Copeland, Stanger, & Hudziak, 2004; Rhee et al., 2007; Sanson, Pedlow, Cann, Prior, & Oberklaid, 1996; Young, Stallings, Corley, Krauter & Hewitt, 2000).

Lahey and Waldman (2005; Lahey et al., 2008) expanded upon their theory, suggesting that different forms of internalizing behavior would be differentially related to novelty seeking. Specifically, they suggest that anxiety symptoms would be negatively correlated with novelty seeking because novelty seeking is inversely related to shyness or behavioral inhibition, whereas depressive symptoms would be uncorrelated with novelty seeking because they are not associated with higher (or lower) levels of novelty seeking. Therefore, the authors predicted that depression is more likely to co-occur with externalizing disorders than anxiety disorders.

Several studies have examined the etiology of the covariation between personality dimensions and psychiatric disorders. A significant genetic correlation between neuroticism and major depressive disorder (MDD) (Carey & DiLalla, 1994; Fanous, Gardner, Prescott, Cancro, & Kendler, 2002; Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott, & Kendler, 2006; Jardine, Martin & Henderson, 1984; Kendler, Gardner, Gatz & Pedersen, 2007; Mackinnon, Henderson & Andrews, 1990) and neuroticism and anxiety symptoms (Carey & DiLalla, 1994; Hettema, Prescott, & Kendler, 2004; Jardine et al., 1984) have been reported. Likewise, Singh and Waldman (2010) reported common genetic and nonshared environmental influences for negative emotionality and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), inattention, and hyperactivity/impulsivity in a pediatric sample. In addition, Waldman et al. (2011) found that 86% of the covariation between CD and negative emotionality in childhood and adolescents could be explained by additive genetic factors, and 100% of the covariation between novelty seeking and CD could be explained by additive genetic factors. Young et al., (2000) found that the covariation among CD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use, and novelty seeking in adolescents could be explained by a single latent underlying phenotype (Behavioral Disinhibition), which was highly heritable (h2 = .84). Moreover, Tackett, Waldman, Van Hulle, and Lahey (2011) found that 10–19% of the variance in MDD and CD could be explained by genetic factors shared in common with negative emotionality.

The Present Study

Previous behavioral genetic research has provided evidence of common genetic influences between internalizing and externalizing disorders, between neuroticism and internalizing disorders, and between novelty seeking and externalizing disorders. In the present study, we tested Lahey and Waldman’s (2003) model in a genetically informative sample, and conducted multivariate genetic analyses to examine whether there are common genetic and environmental influences among personality (neuroticism and novelty seeking), three internalizing disorders (MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and separation anxiety disorder (SAD)), and three externalizing disorders (ADHD, ODD, and CD).

First, we predicted that neuroticism is a common risk factor that covaries with both internalizing and externalizing disorders and shares considerable common genetic and environmental influences with them. Second, we predicted that novelty seeking is a risk factor specific to externalizing disorders, and that the genetic and or environmental influences on novelty seeking will either not influence internalizing disorders, or be negatively associated with internalizing disorders.

If these hypotheses are supported in our data, the results will provide evidence that neuroticism is a common feature between internalizing and externalizing disorders and that novelty seeking is a broad-band specific feature influencing only externalizing disorders. Additionally, the results will help explain the aforementioned contradictory results regarding the covariation between internalizing and externalizing disorders. Finally, they will provide information regarding the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on the covariation between personality dimensions and psychiatric disorders.

Method

Participants

Participants were twin pairs who were assessed by the Center for Antisocial Drug Dependence (CADD), a multifaceted study that has been approved by the Internal Review Board of the University of Colorado. They were recruited from the Colorado Twin Registry through their participation in the Colorado Twin Study or the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Study, which are both community-based samples. Specific information regarding recruitment for both samples can be found in Rhea, Gross, Haberstick, and Corley (2006). Participants were twin pairs aged 12–18 (M = 14.82, SD = 2.15), including 635 MZ twin pairs (290 male pairs and 345 female pairs) and 691 DZ twin pairs (219 male pairs, 211 female pairs, and 261 opposite sex pairs). The ethnic distribution of the sample as reported by participants on a questionnaire was 84% White, 2% African-American, 8% Hispanic, 3% Asian, 2% Native American, and 1% unknown.

Procedure

Written descriptions regarding the study were given to all participants, who gave informed assent or consent depending on the age of the participant. Zygosity of the same-sex twin pairs was determined from two sources. First, interviewers used nine items to assess the twins’ physical characteristics. Second, concordance of the twin pairs’ genotype at 11 highly informative short tandem repeat polymorphisms was examined. Twin pairs who were physically similar and whose genotypes were matched at the 11 short tandem repeat polymorphisms were classified as MZ. Twin pairs who differed in physical characteristics and genotype composition were classified as DZ. Discrepancies between the two sources of zygosity occurred in nine twin pairs; these pairs were re-examined, and the discrepancies were resolved.

Participants were administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), a structured psychiatric interview which assesses lifetime and past year DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) symptoms and diagnoses for Axis I disorders. The DISC was used to assess the six psychiatric disorders (MDD, GAD, SAD, ADHD, CD, and ODD) examined in the present study.

Participants were also administered a short form of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ; Floderus-Myrhed, Pedersen, & Rasmuson, 1980), which assesses neuroticism and extraversion. For participants 16 years of age or older, The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ; Cloninger, 1987; Cloninger, Przybeck & Svrakic, 1991), which assesses novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and reward dependence, was administered. For participants under 16 years of age, the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI; Cloninger, 1994) was administered. This measure assesses the same personality constructs that are assessed in the TPQ, but abstract items are omitted, and the content and readability are adjusted for children aged 7 to 14 (Cloninger, 1994).

We examined the neuroticism scale from the EPQ (α = .67 in current sample) and the novelty seeking scale from the TPQ/TCI (α = .68 and .67 in current sample). These personality dimensions were chosen specifically to test the hypotheses suggested by Lahey and Waldman’s model (2003; viz., neuroticism is a common feature underlying both internalizing and externalizing disorders and novelty seeking is a broadband-specific feature for externalizing disorders), as supported by the literature reviewed in the introduction. Although both psychiatric disorders and personality constructs were measured concurrently, the assumption is that personality and temperament differences predate the onset of psychiatric disorders.

The 18-item EPQ includes nine questions related to neuroticism and requires participants to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to questions that reflect neurotic tendencies, such as: “Are you touchy about some things?”, and “Do you suffer from ‘nerves’?” Two different measures were used to assess novelty seeking depending upon the age of the participant. Examples of the novelty seeking items on the TPQ include: “I think in detail before deciding” (reverse scored), and “I do things spontaneously” (Cloninger, 1987). Some examples of the novelty seeking items on the TCI include: “It is easier for me to do new and fun things when my parents are with me” (reverse scored), and “I like it when kids can do whatever they want without any rules.” Prior to analyses, the data from both the TCI and the TPQ were converted into standardized scores. Examining the standardized scores allowed us to create a cohesive data set.

Analyses

In the present study, the twin design was utilized in order to estimate the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on neuroticism, novelty seeking, and the covariance between personality characteristics and psychopathology. Genetic influences (A) are indicated by the extent to which MZ correlations exceed DZ correlations. When the MZ correlation is greater than the DZ correlation, it can be inferred that the difference is due to genetic influences. This is because MZs share 100% of their segregating genes from their parents, whereas DZs or siblings share by descent only 50% of their segregating genes on average. Shared environmental influences (C) are estimated as the degree to which MZs or DZs are similar after accounting for genetic influences. In other words, shared environmental influences constitute non-genetic familial similarities. The differences between individual twins not due to genetic differences constitute nonshared environmental influences (E); these are the environmental influences that are not shared among family members. E also includes the influence of measurement error.

Non-additive genetic influences were not tested in the present study because results from a previous study that examined a subset of the sample examined here, found limited evidence for shared environmental influences but no evidence for non-additive genetic influences (Ehringer, Rhee, Young, Corley & Hewitt, 2006). Examination of both shared environmental influences and non-additive influences is prohibited in the same model because both estimates rely on the same information (i.e., the difference between MZ and DZ correlations). There were significant effects of age and sex on the variables examined in the present study. Ehringer et al. (2006) reported females expressed higher symptom counts for the internalizing disorders GAD, MDD, and SAD and males expressed higher symptom counts for CD. The likelihood of having a symptom or a diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder also increased with age (Ehringer et al., 2006). There was a statistically significant, positive correlation between the age of the participant and scores on novelty seeking, r = .05, p<.01, and neuroticism, r=.06, p<.01. Females had a higher score on neuroticism than males, t (3392) = −6.46, p <.01, and males had a higher score on novelty seeking than females, t (3437) = 4.33, p < .01. Therefore, the effects of age and sex were statistically controlled in all analyses. For the ordinal variables (i.e., psychiatric disorders), age was included as a covariate in the model, and sex-specific thresholds, which take into account the difference in prevalence of symptoms and diagnoses in males and females, were implemented. For the continuous variables (i.e., neuroticism and novelty seeking), age and sex were regressed out prior to further analyses.

DSM-IV symptom counts for psychiatric disorders are highly skewed. In order to maximize the statistical benefits of a normal distribution of liability, symptom counts for psychopathology were transformed into ordinal data with the assumption of an underlying normal continuous liability distribution. As Derks, Dolan and Boomsma (2004) showed in their simulation study, this is the optimum approach, as the underlying correlations and parameter estimates produced are unbiased. Data were categorized into the following ordinal categories: no symptoms (0), one or more symptoms but no diagnosis (1), and diagnosis for psychopathology (2). Appendix A shows the percentage of individuals per zygosity group in each of the ordinal categories.

All analyses were conducted in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004) using raw data and the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. Three sets of correlations were estimated. First, phenotypic correlations among the personality and psychiatric variables were estimated using all individuals. Second, within-trait cross-twin correlations (i.e., correlations between the same variable in twin 1 and twin 2) were estimated in MZ and DZ twin pairs. Third, cross-trait cross-twin correlations (i.e., correlations between different variables in twin 1 and twin 2) for the psychiatric and personality variables were estimated.

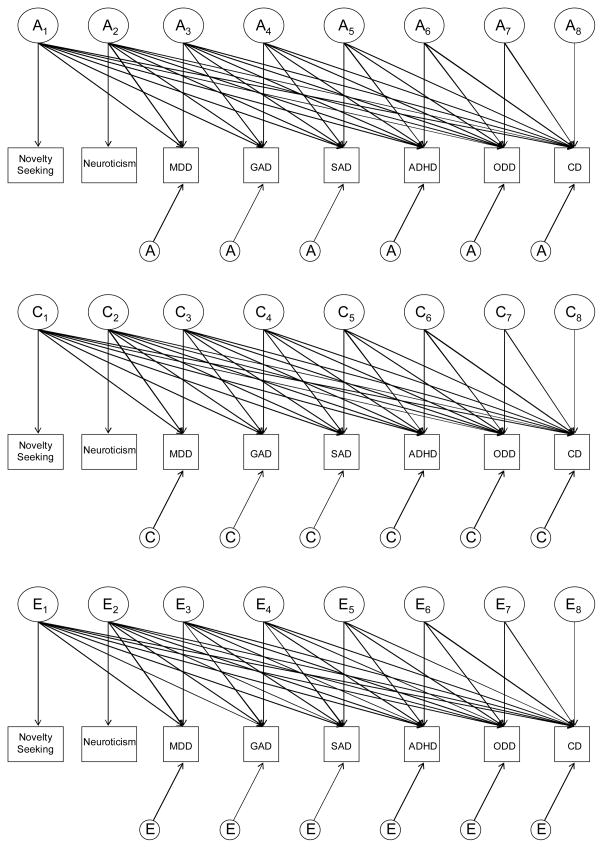

Next, a multivariate Cholesky decomposition was applied to the data as the baseline saturated model (see Appendix B). Here, variances and covariances among disorders are due to: additive genetic factors (A), shared environmental factors, (C), and nonshared environmental factors (E). Neuroticism and novelty seeking are the primary phenotypes in the model based on our hypothesis that neuroticism is a common factor and novelty seeking is a broad-band specific risk factor for psychopathology. The personality variables were followed by the internalizing disorders (MDD, GAD, and then SAD), then the externalizing disorders (ADHD, ODD, and then CD). The first factor influenced novelty seeking, neuroticism and all psychiatric disorders. The second factor influenced neuroticism and the psychiatric disorders. The third factor only influenced the psychiatric disorders, the fourth factor influenced GAD, SAD and the externalizing disorders, the fifth factor influenced SAD and the externalizing disorders, the sixth factor influenced the externalizing disorders, the seventh factor influenced ODD and CD, and the last factor only influenced CD.

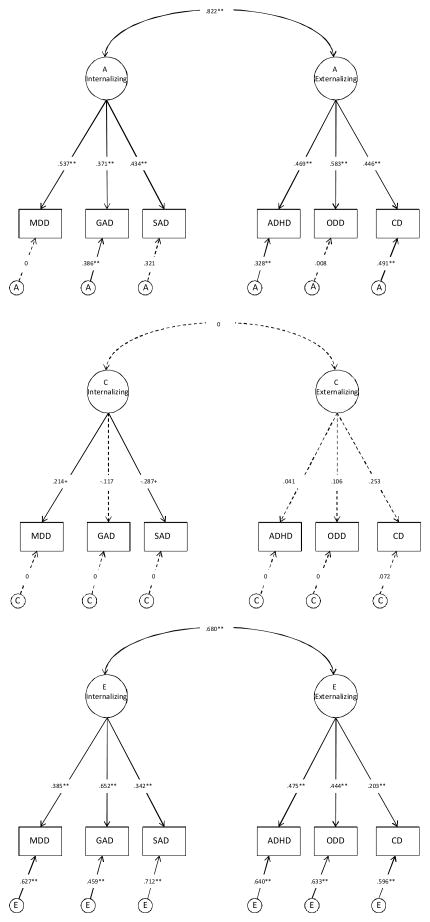

We then tested a more parsimonious correlated independent pathway model based on Lahey and Waldman’s hypothesis. We first tested a correlated independent pathway model examining only the internalizing and externalizing disorders, excluding the personality variables (see Appendix C), to estimate the correlation between genetic and environmental influences influencing internalizing and externalizing disorders. In this model, there are A, C, and E factors influencing the internalizing disorders, A, C, and E factors influencing the externalizing disorders, and disorder-specific A, C, and E factors.

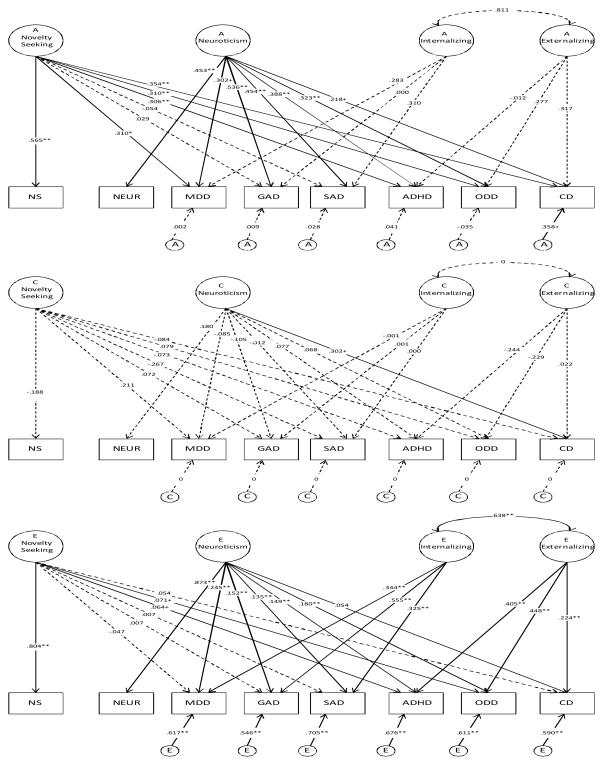

We then tested the correlated independent pathway model examining both the personality factors and the internalizing and externalizing disorders. This model included A, C, and E factors for novelty seeking, neuroticism, the internalizing disorders, the externalizing disorders, and disorder-specific A, C, and E factors. In this model, novelty seeking appears first and neuroticism appears second (see Appendix D). We were interested in examining the association between novelty seeking and the psychiatric disorders and between neuroticism and the psychiatric disorders, rather than the association between novelty seeking and neuroticism. Therefore, the variance of neuroticism is not decomposed into that shared in common with novelty seeking and that specific to neuroticism as it is in the Cholesky decomposition. However, the model included a correlation between novelty seeking and neuroticism. The internalizing factor appears third and the externalizing factor appear fourth in this model, which allowed us to examine whether the covariation between internalizing and externalizing disorders can be sufficiently explained by novelty seeking and neuroticism, or whether additional contributions to the covariance are indicated.

In examining the fit of each model to the data, the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Bentler, 1990) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1987) were examined, given the χ2’s sensitivity to sample size. A TLI greater than .95 and RMSEA less than .06 indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1998). In order to constrain the cross-twin, cross-trait correlation between the latent internalizing and externalizing factors in the DZ twins to be half of that for MZ twins, a constraint group was utilized. Because of this constraint group, we were unable to conduct a chi-squared difference test between nested models due to limitations of the statistical package Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2004) Therefore, the fit of alternative models was evaluated examining the χ2, the TLI, and the RMSEA. Several parameters that were estimated at zero were fixed to zero, as a parameter approaching its boundary can cause the model to fail.

Results

Models estimating the correlations among twin 1 and twin 2’s personality (neuroticism and novelty seeking) and psychiatric disorders (MDD, GAD, SAD, ADHD, ODD, and CD) were tested. Phenotypic correlations (i.e., correlations among different variables within the same individual) were constrained to be equal between twin 1 and twin 2 and between MZ and DZ twins. Cross-trait, cross-twin correlations were estimated constraining those for twin 1 and twin 2 to be the same. For example, the correlation between MDD for twin 1 and ADHD for twin 2 was constrained to be equal to the correlation between ADHD for twin 1 and MDD for twin 2.

A model allowing sex differences in the correlations (i.e., phenotypic correlations allowed to differ between males and females, and within-trait, cross-twin and cross-trait, cross-twin correlations allowed to differ for MZ male, MZ female, DZ male, DZ female, and DZ opposite-sex pairs) (χ2 (596) = 711, p < .01, TLI = .960, RMSEA = .027) and a model constraining the parameters to be equal across sexes (χ2 (732) = 850, p < .01, TLI = .967, RMSEA = .025) were tested. Both models fit the data well, and the difference between the two models was not significant (Δχ2 (136) = 151, p = .18).

Correlations

Phenotypic correlations among neuroticism, novelty seeking, and the six psychiatric disorders were examined (see Appendix E) There were larger correlations among internalizing disorders (.38 on average) and among externalizing disorders (.39 on average) than between internalizing and externalizing disorders (.31 on average). Neuroticism was moderately correlated with both the internalizing and externalizing disorders with a range from .20 (for CD) to .36 (for GAD). Novelty seeking was moderately correlated with the externalizing disorders (.22–.25) and uncorrelated with the internalizing disorders, with the exception of MDD (.10).

Within-trait, cross-twin correlations and the cross-trait, cross-twin correlations for neuroticism, novelty seeking, and the six internalizing and externalizing disorders in MZ and DZ twin pairs were examined (see Appendix F). The within-trait, cross-twin MZ correlations were larger than the DZ correlations for both the personality variables and the psychopathology variables, suggesting genetic influences on all variables examined. The cross-trait, cross-twin correlations are presented for all of the psychopathology and personality variables. Here, the correlations between a trait in twin 1 and a different trait in twin 2 are shown. With the exception of the correlation between neuroticism and novelty seeking, the MZ cross-trait, cross-twin correlations were higher than the DZ cross-trait, cross-twin correlations, indicating evidence of common genetic influences among the observed variables.

Biometrical Models

The Cholesky decomposition was tested as a baseline saturated model (see Appendix B). This model fit the data well (χ2 (740) = 864, p = .001, TLI = .966, RMSEA = .025). We then tested the more parsimonious correlated independent pathway model examining the internalizing and externalizing disorders only. This model is presented in Figure A2 (Appendix C), where non-significant paths are represented by dashed lines. This model fit the data well also (χ2 (474) = 590, p = .0002, TLI = .963, RMSEA = .030). The latent internalizing genetic factor and the latent internalizing nonshared environmental factor had significant influences on MDD, GAD, and SAD and the latent externalizing genetic factor and the latent externalizing nonshared environmental factor had significant influences on ADHD, ODD, and CD. There was also a significant correlation between the latent internalizing and externalizing genetic factors and between the latent internalizing and externalizing nonshared environmental factors. Most of the influences of the latent internalizing and externalizing shared environmental factors were not significant.

The second correlated independent pathway model included novelty seeking and neuroticism as well as the internalizing and externalizing disorders. This model is presented in Appendix D, where non-significant paths are represented by dashed lines. This model fit the data well (χ2 (757) = 879, p < .01, TLI = .967, RMSEA = .025), with model fit indices that were very similar to those of the Cholesky model, indicating that the independent pathway model does not fit the data worse than the Cholesky model. In this model, which controls for the genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking and neuroticism, the magnitude of the effect of the latent genetic internalizing factor on GAD and that of the latent genetic externalizing factor on ADHD was near zero. A model dropping these paths to zero had nearly identical fit statistics as those in the Cholesky model (χ2 (759) = 880, p < .01, TLI = .967, RMSEA = .025). Also, none of the latent genetic or shared environmental internalizing and externalizing factors had significant effects on any disorders. A model dropping these paths to zero had nearly identical fit statistics as those in the Cholesky model also (χ2 (770) = 890, p < .01, TLI = .968, RMSEA = .024).

Finally, we fit a reduced model where most of the non-significant paths in the full correlated independent pathway model (represented by dashed lines in Appendix D) were dropped without a significant decrement in the fit of the model (χ2 (794) = 916, p < .01, TLI = .968, RMSEA = .024). Exceptions were the disorder-specific genetic influences on MDD, SAD, ADHD, and CD, which became significant when the latent internalizing and externalizing genetic factors (which did not significantly influence any of the disorders after controlling for genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking and neuroticism) were dropped from the model. The fit statistics indicate that the reduced model does not fit the data worse than the full model. Also, the parameters from the full and the final reduced models were very similar.

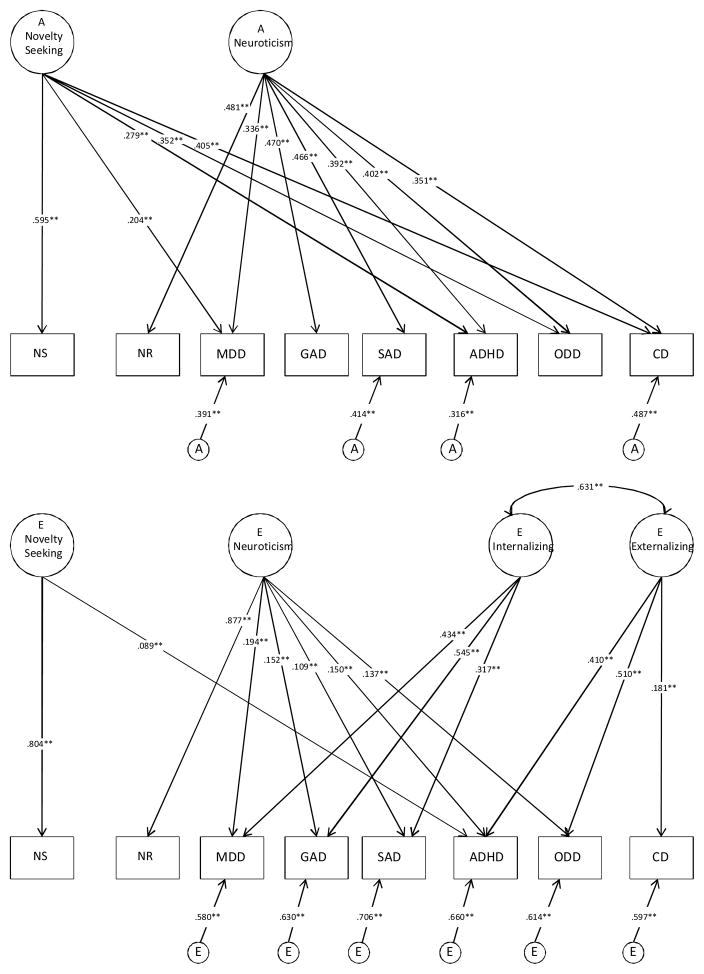

Figure 1 presents the results from the final reduced correlated independent pathway model. Shared environmental influences could be dropped entirely from the model. The genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking significantly influenced MDD and the externalizing disorders, but not the anxiety disorders (GAD and SAD). The nonshared environmental influences shared in common with novelty seeking did not influence internalizing disorders or externalizing disorders. The genetic and nonshared environmental influences shared in common with neuroticism significantly influenced both internalizing and externalizing disorders; one exception was that the nonshared environmental influences shared in common with neuroticism did not significantly influence CD. The genetic influence of the latent internalizing and externalizing factors and the genetic correlation between the latent internalizing and externalizing factors could be dropped from the model. In contrast, the latent internalizing nonshared environmental factor had a significant influence on the internalizing disorders, the latent externalizing nonshared environmental factor had a significant influence on the externalizing disorders, and the correlation between the latent internalizing and externalizing nonshared environmental factors was significant. There were disorder-specific genetic influences for MDD, ADHD, and CD, and disorder-specific nonshared environmental influences for all disorders.

Figure 1.

Final reduced independent pathway model. A = additive genetic influences; E = nonshared environmental influences; NS = novelty seeking; NR = neuroticism; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder; * p < .05, **p < .01.

Appendix G shows the percentage of variance of each disorder explained by the genetic, shared environmental, and nonshared environmental also influencing novelty seeking, neuroticism, the latent internalizing factor, and the latent externalizing factor, and by the disorder-specific factors and age (derived by squaring the parameters from the full correlated independent pathway model shown in Appendix D). Table 1 shows the same results for the final reduced model (derived from parameters in Figure 1). The two sets of results are presented to show that the results are similar, but only the results from Table 1 will be discussed in detail. Genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking explained 8 – 16% of the variance of the externalizing disorders and 4% of the variance of MDD. Genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking did not explain variance in the anxiety disorders. None of the variance of internalizing or externalizing disorders was explained by nonshared environmental influences shared in common with novelty seeking. Genetic influences shared in common with neuroticism explained between 11% (for MDD) and 22% (for GAD) of the variance of internalizing and externalizing disorders. Nonshared environmental influences shared in common with neuroticism explained between 1% (for SAD) and 4% (for MDD) of variance of internalizing and externalizing disorders, but did not contribute significantly to the variance of CD. After controlling for the genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking and neuroticism, neither genetic nor shared environmental influences on the latent internalizing and externalizing factors influenced any of the disorders.

Table 1.

Percent Variance Explained by Each Latent Variable and Age in the Final Reduced Model

| NS | NR | INT | EXT | Disorder Specific | Total | Age | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | ||

| NS | 35 | 0 | 65 | 35 | 0 | 65 | |||||||||||||

| NR | 23 | 0 | 77 | 23 | 0 | 77 | |||||||||||||

| MDD | 4 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 15 | 0 | 34 | 31 | 0 | 56 | 13 | |||

| GAD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 22 | 0 | 72 | 6 | |||

| SAD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 17 | 0 | 50 | 39 | 0 | 61 | 0 | |||

| ADHD | 8 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 10 | 0 | 44 | 33 | 0 | 63 | 3 | |||

| ODD | 12 | 0 | 0 | 16. | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 28 | 0 | 66 | 6 | |||

| CD | 16 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 24 | 0 | 36 | 52 | 0 | 39 | 9 | |||

Note: NS = novelty seeking; NR = neuroticism; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder; A = Additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = non-shared environmental influence.

Appendix H shows the covariance between psychiatric disorders and percent covariance explained by novelty seeking, neuroticism and the internalizing/externalizing factors that were derived from the parameter estimates from the full model, and Table 2 shows the same results from the reduced model. In the reduced model, the covariation among the externalizing disorders (19–32%) and between MDD and the externalizing disorders (14–23%) was partially explained by genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking; however, the covariation among the internalizing disorders and between the anxiety disorders and the externalizing disorders could not be accounted for by any influences (genetic, shared environmental, or nonshared environmental) shared in common with novelty seeking. The covariation among internalizing disorders (31–53%), among externalizing disorders (30–36%), and between internalizing and externalizing disorders (29–78%) was partially explained by genetic influences shared in common with neuroticism. Nonshared environmental influences in common with neuroticism partially explained the covariation among internalizing disorders (4–6%), between ADHD and ODD (4%), between the internalizing disorders and ADHD (6–7%) and between the internalizing disorders and ODD (5–6%), but did not explain the covariation between CD and any of the other disorders. Shared environmental influences in common with neuroticism did not explain any of the covariation between or among the internalizing and externalizing disorders. There were no genetic and shared environmental influences on the residual covariance between any of the disorders. Nonshared environmental influences explained 14 to 46% of the residual covariance between the disorders.

Table 2.

Covariance (% Covariance) Explained by Each Latent Variable and Age in the Final Reduced Model

| Covariance Explained by Novelty Seeking | Covariance Explained by Neuroticism | Residual Covariance | Age | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | |||

| Covariance between internalizing dimensions | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| MDD-GAD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .158(30.76) | 0(0) | .029(5.74) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .236(46.07) | .090(17.44) | .513(100) |

| MDD-SAD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .157(47.69) | 0(0) | .021(6.44) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .137(41.91) | .013(3.96) | .328(100) |

| GAD-SAD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .219(52.49) | 0(0) | .017(3.97) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .173(41.40) | .009(2.14) | .417(100) |

| Covariance between externalizing dimensions | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| ADHD-ODD | .098(18.52) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .158(29.72) | 0(0) | .021(3.88) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .209(39.44) | .045(8.43) | .530(100) |

| ADHD-CD | .113(29.81) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .138(36.30) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .074(19.58) | .054(14.32) | .379(100) |

| ODD-CD | .143(31.85) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .141(31.52) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .092(20.62) | .072(16.01) | .448(100) |

| Covariance between internalizing and externalizing dimensions | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| MDD-ADHD | .057(14.36) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .132(33.22) | 0(0) | .029(7.34) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .112(28.32) | .067(16.76) | .396(100) |

| MDD-ODD | .072(15.58) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .135(29.31) | 0(0) | .027(5.77) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .140(30.31) | .088(19.04) | .461(100) |

| MDD-CD | .083(23.17) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .118(33.07) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .049(13.90) | .106(29.86) | .357(100) |

| GAD-ADHD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .184(46.80) | 0(0) | .023(5.79) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .141(35.82) | .046(11.59) | .394(100) |

| GAD-ODD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .189(42.42) | 0(0) | .021(4.68) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .175(39.38) | .060(13.53) | .445(100) |

| GAD-CD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .165(54.92) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .062(20.72) | .073(24.36) | .300(100) |

| SAD-ADHD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .183(63.50) | 0(0) | .016(5.68) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .082(28.51) | .007(2.30) | .288(100) |

| SAD-ODD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .187(59.85) | 0(0) | .015(4.77) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .102(32.59) | .009(2.79) | .313(100) |

| SAD-CD | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .164(77.74) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | .036(17.21) | .011(5.05) | .210(100) |

Note: MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder; A = Additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = non-shared environmental influence.

Discussion

Based on previous research, it is unclear whether internalizing disorders are a risk factor for externalizing disorders, or whether internalizing disorders act as a protective factor against externalizing disorders (i.e., Keiley et al., 2003; Sanson et al., 1996; Serbin et al., 1991; ; Quay & Love, 1977). Lahey and Waldman (2003) proposed examining temperament and personality constructs as potential common and broad-band specific features that may help us distinguish the risk factors that are shared in common between internalizing and externalizing disorders and the risk factors that are specific to externalizing disorders. We tested Lahey and Waldman’s (2003) model in a genetically informative study to examine whether there are common genetic and environmental influences between the personality constructs neuroticism and novelty seeking, three internalizing disorders (MDD, GAD, and SAD) and three externalizing disorders (ADHD, ODD, and CD). We predicted that neuroticism would be a common risk factor that covaries with both internalizing and externalizing disorders, and that novelty seeking would be a risk factor specific to externalizing disorders. Lahey and Waldman (2005; Lahey et al., 2008) hypothesized that anxiety symptoms would be negatively correlated with novelty seeking because novelty seeking is inversely related to shyness or behavioral inhibition, and depressive symptoms would be uncorrelated with novelty seeking because they are not associated with higher (or lower) levels of novelty seeking. Neuroticism was moderately correlated with both internalizing and externalizing disorders (.20–.36). In contrast, novelty seeking was moderately correlated with all externalizing disorders (.22–.25), modestly correlated with MDD (.10), and uncorrelated with GAD (.01) and SAD (.03).

Consistent with Lahey and Waldman’s (2003) hypothesis, genetic and nonshared environmental influences shared in common with neuroticism helped to explain a proportion of the variance in internalizing and externalizing disorders (with the exception of nonshared environmental influences on CD). Similarly, the covariance among internalizing and externalizing disorders and between internalizing and externalizing disorders was partially explained by genetic influences, and in some instances, nonshared environmental influences, shared in common with neuroticism. These results suggest that neuroticism is a common factor underlying both internalizing and externalizing disorders, and help to explain the comorbidity we observe between internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking helped to explain the variance in externalizing disorders and MDD, but not in the anxiety disorders. Genetic influences shared in common with novelty seeking were also found to influence the covariation among the externalizing disorders and between MDD and externalizing disorders, but not among the internalizing disorders or between the anxiety disorders and externalizing disorders. As Lahey and Waldman (2003) predicted, these results suggest that novelty seeking is a broadband-specific factor that is specific to externalizing disorders and MDD.

After controlling for the influences shared in common with neuroticism and novelty seeking, there were no significant genetic or shared environmental influences explaining the covariance among the disorders examined. This finding suggests that novelty seeking and neuroticism may be sufficient markers explaining the comorbidity between internalizing disorders and externalizing disorders.

Lahey and Waldman (2005; Lahey et al., 2008) hypothesized that anxiety symptoms would be negatively correlated with novelty seeking and depressive symptoms would be uncorrelated with novelty seeking, and as a result, depression should be more related to externalizing disorders than anxiety disorders. The latter prediction is consistent with several findings in the literature. For example, Hewitt et al. (1997) reported higher factor correlations between MDD and externalizing disorders (.25 to .37) than between anxiety disorders and externalizing disorders (.07–.22), and a meta-analysis by Angold (1999) reported higher comorbidity between depression and externalizing disorders (odds ratios of 5.5 to 6.6) than between anxiety disorders and externalizing disorders (odds ratios of 3.0 to 3.1). The present study also found that MDD is more associated with externalizing disorders than anxiety disorders.

Contrary to predictions, however, novelty seeking explained a significant proportion of the genetic variance in MDD, and the covariance between MDD and the externalizing disorders, suggesting that novelty seeking may be a common factor shared in common between MDD and externalizing disorders as well as that shared in common among externalizing disorders. At least one other study has reported a significant association between novelty seeking and MDD. Khan et al. (2005) reported that higher novelty seeking scores significantly increased the risk of developing MDD, and that novelty seeking accounted for 3–5.8% of the overall covariance between MDD and drug dependence, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Potential corroborating results were also reported in a recent animal study. Li, Zheng, Liang, and Peng (2010) modeled depression by inducing anhedonia (an inability to experience pleasure from activities formally found enjoyable) in rats by subjecting them to chronic mild stresses such as food and water deprivation, and being housed in a small cage with several other rats. Approximately 50% of the animals subjected to stress showed a decreased preference for sucrose water and were labeled as anhedonic, whereas the other 50% did not show a decreased preference for sucrose water and were labeled as stress-resistant. The anhedonic rats showed significantly more novelty seeking behavior, as measured by an open-field and elevated plus maze test, than the stress-resistant or control rats.

One potential explanation for this unexpected correlation comes from findings suggesting a strong link between novelty seeking and bipolar disorder (Nowakowska, Strong, Santosa, Wang & Ketter, 2005; Olvera et al., 2009; Sasayama et al., 2011). Because it is often difficult to differentiate between MDD and bipolar depression, especially during childhood and adolescence (Cuellar, Johnson & Winters, 2005), it is possible that a percentage of the individuals diagnosed with MDD in the present study may have been experiencing bipolar depression, or may be at risk for developing bipolar disorder.

The genetic association between neuroticism and ADHD presented in this study is consistent with results from a recent study reporting that neuroticism partially mediated the relationship between genetic risk and ADHD symptoms (Martel, Nicolas, Jernigan, Friderici & Nigg, 2010). Future research examining neuroticism and/or novelty seeking as potential mediators between genetic risk and psychiatric disorders is needed.

Lahey and Waldman (2005; Lahey et al., 2008) predicted a negative association between novelty seeking and anxiety disorders. Contrary to this prediction, there was a lack of an association between novelty seeking and anxiety disorders in the present study. One possible explanation for this unpredicted finding is that novelty seeking is inversely related to the “fear” anxiety disorders, such as specific phobia, agoraphobia, and panic disorder, but not to the “distress” anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder. Several studies have found results supporting a distinction between “fear” and “distress” anxiety disorders, and evidence suggesting that the “distress” anxiety disorders are more associated with major depressive disorder than the “fear” anxiety disorders (e.g., Krueger, 1999; Watson, O’Hara, Stuart, 2008). Unfortunately, the present study did not assess “fear” anxiety disorders, making this hypothesis difficult to test.

Other limitations of the present study should be considered when interpreting its results. First, DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for both CD and ADHD did not include age of onset of symptoms or symptom clustering. Second, our sample is from the general population, and the prevalence of psychiatric disorders is low, particularly for internalizing disorders in males. Third, the data analyzed were based only on self-report data, which can lead to underestimates of heritability (Eaves et al., 1997). Fourth, because both personality and psychiatric disorders were examined via self report, the associations among psychiatric disorders or between personality and psychiatric disorders may be inflated due to method covariance. Fifth, the present study did not include a regulatory dimension of temperament, such as effortful control, which has been shown to be related to comorbidity among internalizing and externalizing disorders (e.g., Oldenhinkel, Hartman, Winter, Veenstra, & Ormel, 2004). Finally, it is possible that parameters that were low in magnitude were not statistically significant due to low power, which may have limited our ability to estimate shared environmental influences.

Previous phenotypic studies have examined the association between personality and internalizing and externalizing disorders and showed that personality can help to explain the covariation between these two clusters of disorders (e.g., Khan et al., 2005). Also, previous genetic studies have demonstrated common genetic influences between neuroticism and psychiatric disorders (Carey & DiLalla, 1994; Fanous et al., 2002; Hettema et al., 2004; Hettema et al., 2006; Jardine et al., 1984; Kendler et al., 2007; Mackinnonet al., 1990; Singh & Waldman, 2010) and between novelty seeking and psychiatric disorders (e.g., Young et al., 2000). To our knowledge, the present study is the first to examine neuroticism as a common feature shared by both internalizing and externalizing disorders and novelty seeking as a broad-band specific feature shared only among externalizing disorders in a genetically informative study.

The present study’s results suggest that neuroticism is a common feature of both internalizing disorders and externalizing disorders, and that novelty seeking is a broad-band specific factor that distinguishes anxiety disorders from externalizing disorders. These results help to explain the contradictory findings regarding the covariation between internalizing and externalizing disorders in the literature by helping to explaining the etiology of the covariation. Further examination of the relationship between novelty seeking and MDD is warranted, as the association is unexpected given the current nosology of MDD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH043899, MH016880, HD010333, DA011015, DA013956, and HD050346. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the meeting of the Behavior Genetics Association on June 4th, 2010 in Seoul, Korea. We thank the participants who contributed their time to this project and the research assistants at the Institute for Behavioral Genetics for careful work in data collection, coding, and management.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Percent of Individuals with no symptoms, one or more symptoms, and diagnosis by zygosity and sex

| MZF | MZM | DZF | DZM | DZO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 345 pairs | 290 pairs | 211 pairs | 219 pairs | 261 pairs | ||

| MDD | No symptoms | 571 (.83) | 554(.96) | 366(.87) | 405(.92) | 456(.87) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 58(.08) | 15(.03) | 36(.09) | 23(.05) | 34(.07) | |

| Diagnosis | 35(.09) | 11(.02) | 20(.05) | 10(.02) | 32(.06) | |

| GAD | No symptoms | 576(.83) | 538(.93) | 363(.86) | 403(.92) | 441(.84) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 87(.13) | 37(.06) | 48(.11) | 33(.08) | 64(.12) | |

| Diagnosis | 27(.04) | 5(.01) | 11(.03) | 2(.00) | 17(.03) | |

| SAD | No symptoms | 427(.62) | 478(.82) | 288(.68) | 355(.81) | 354(.68) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 239(.35) | 95(.16) | 118(.28) | 75(.17) | 155(.30) | |

| Diagnosis | 24(.03) | 7(.01) | 16(.04) | 8(.02) | 13(.02) | |

| ADD | No symptoms | 410(.59) | 340(.59) | 268(.64) | 236(.53) | 297(.57) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 265(.38) | 221(.38) | 142(.34) | 181(.41) | 201(.39) | |

| Diagnosis | 15(.02) | 19(.03) | 12(.03) | 21(.05) | 24(.05) | |

| ODD | No symptoms | 564(.82) | 496(.86) | 359(.85) | 368(.84) | 431(.83) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 108(.16) | 72(.12) | 50(.12) | 57(.13) | 67(.13) | |

| Diagnosis | 18(.03) | 12(.02) | 13(.03) | 13(.03) | 24(.05) | |

| CD | No symptoms | 412(.60) | 284(.49) | 285(.68) | 207(.47) | 252(.48) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 248(.36) | 221(.38) | 119(.28) | 185(.42) | 221(.42) | |

| Diagnosis | 30(.04) | 75(.13) | 18(.04) | 46(.11) | 49(.09) | |

Note. MZF= female monozygotic twin pairs; MZM= malemonozygotic twin pairs; DZF= female dizygotic twin pairs; DZM= male dizygotic twin pairs; DZO= opposite sex dizygotic twin pairs; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder.

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Cholesky Model = Additive genetic influences; C = shared environmental influences; E = nonshared environmental influences; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder CD = conduct disorder.

Appendix C

Figure A2.

Correlated independent pathway model without personality variables. A = additive genetic influences; C = shared environmental influences; E = nonshared environmental influences; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder; solid lines= significant; dashed lines= non significant; + p values were .060 for Cinternalizing’s effect on MDD and .073 for Cinternalizing’s effect on SAD; * p < .05; **p < .01.

Appendix D

Figure A3.

Full correlated independent pathway model. A = additive genetic influences; C = shared environmental influences; E = nonshared environmental influences; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder; solid lines= significant; dashed lines= non significant; + p values were .053 for ANeuroticism’s effect on MDD, .109 for ANeuroticism’s effect on CD, .094 for ACD’s effect on CD, .052 for CNeuroticism’s effect on CD, .084 for ENovelty Seeking’s effect on ADHD, and .085 for ENovelty Seeking’s effect on ODD, and all of these parameters were statistically significant in the final reduced

Appendix E

Table A2.

Phenotypic correlations among disorders and personality constructs

| NEUR | NS | MDD | GAD | SAD | ADHD | ODD | CD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEUR | 1.00 | |||||||

| NS | .09*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| .11*** | ||||||||

| .06* | ||||||||

| MDD | .34*** | .10** | 1.00 | |||||

| .36*** | .11** | |||||||

| .33*** | .08 | |||||||

| GAD | .36*** | .01 | .41*** | 1.00 | ||||

| .39*** | .00 | .45*** | ||||||

| .34*** | .02 | .49*** | ||||||

| SAD | .32*** | .03 | .29*** | .44*** | 1.00 | |||

| .32*** | .02 | .30*** | .39*** | |||||

| .33*** | .04 | .31*** | .53*** | |||||

| ADHD | .32*** | .23*** | .30*** | .38*** | .27*** | 1.00 | ||

| .33*** | .23*** | .35*** | .31*** | .24*** | ||||

| .32*** | .25*** | .30*** | .48*** | .33*** | ||||

| ODD | .32*** | .22*** | .44*** | .35*** | .27*** | .50*** | 1.00 | |

| .34*** | .19*** | .51*** | .41*** | .23*** | .44*** | |||

| .30*** | .25*** | .42*** | .31*** | .32*** | .57*** | |||

| CD | .20*** | .25*** | .26*** | .18*** | .25*** | .30*** | .38*** | 1.00 |

| .26*** | .29*** | .31*** | .18*** | .27*** | .30*** | .36*** | ||

| .15*** | .25*** | .31*** | .24*** | .26*** | .34*** | .47*** |

Note. Bold type = parameters fixed to be equal between males and females; italic type = female sample; standard type = male sample; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; CD = conduct disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; NS = novelty seeking; NEUR = neuroticism;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p< .001.

Appendix F

Table A3.

Within trait, cross-twin and cross trait, cross-twin correlations

| MZT | DZT | MZF | MZM | DZF | DZM | DZO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEUR | .25*** | .12** | .25*** | .24*** | .15* | .09 | .12* |

| NS | .38*** | .13** | .38*** | .40 | .15* | .15* | .09 |

| MDD | .34*** | .09 | .30*** | .60*** | .22 | .24 | −.10 |

| GAD | .32*** | .11 | .34** | .37* | .13 | .05 | .12 |

| SAD | .40*** | .16* | .47*** | .19 | .27** | .04 | .09 |

| ADHD | .33*** | .16** | .37*** | .32*** | .20 | .18* | .14 |

| ODD | .38*** | .14 | .35*** | .44*** | .23 | −.01 | .18 |

| CD | .49*** | .27*** | .55*** | .58*** | .40*** | .36*** | .23 |

| NEUR-NS | .09*** | .10 | .14** | .04*** | .16** | .07 | .08 |

| NEUR-MDD | .16** | .04 | .17** | .11 | .09 | .08 | −.05 |

| NEUR-GAD | .25*** | .09 | .28** | .18* | .18* | .08 | .01 |

| NEUR-SAD | .19*** | .10 | .23*** | .15** | .16* | .08 | .07 |

| NEUR-ADHD | .19*** | .12 | .22*** | .14** | .19** | .08 | .08 |

| NEUR-ODD | .17*** | .08 | .17** | .17** | .14 | .09 | .03 |

| NEUR-CD | .16*** | .12 | .23*** | .10* | .27*** | .07 | .03 |

| NS-GAD | .03 | −.04 | .04 | .01 | .00 | −.16 | −.01 |

| NS-SAD | .00 | .07 | .02 | −.03 | .14* | .06 | .03 |

| NS-ADHD | .18*** | .10 | .17*** | .21*** | .17* | .08 | .07 |

| NS-ODD | .14*** | .09 | .11* | .20*** | .11 | .18** | −.03 |

| NS-CD | .21*** | .11 | .26*** | .20*** | .14* | .12* | .08 |

| MDD-GAD | .23*** | .04 | .22** | .38** | .13 | .07 | −.01 |

| MDD-SAD | .20*** | .00 | .20** | .25* | .09 | −.11 | −.04 |

| MDD-ADHD | .20*** | .10 | .22** | .21 | .20* | .02 | .11 |

| MDD-ODD | .17** | .15 | .18* | .21 | .19* | .24 | .09 |

| MDD-CD | .19*** | .04 | .16* | .36*** | .18* | .13 | −.06 |

| GAD-SAD | .23*** | .06 | .22** | .27** | .12 | −.00 | .06 |

| GAD-ADHD | .21*** | .06 | .27*** | .14 | .19* | −.10 | .07 |

| GAD-ODD | .20** | .12 | .22** | .20 | .08 | .06 | .20* |

| GAD-CD | .07 | −.00 | .06 | .13 | .22** | −.02 | −.13 |

| SAD-ADHD | .16*** | .14 | .14* | .19** | .15* | .13 | .13 |

| SAD-ODD | .22*** | .10 | .25*** | .18* | .12 | .05 | .11 |

| SAD-CD | .14** | .08 | .22*** | .03 | .16 | .01 | .07 |

| ADHD-ODD | .26*** | .18 | .29*** | .23** | .25** | .16*** | .16* |

| ADHD-CD | .23*** | .12 | .19** | .31*** | .16* | .22*** | .02 |

| ODD-CD | .28*** | .15 | .22** | .40*** | .26* | .29*** | −.01*** |

Note. MZT = total monozygotic twin pairs; DZT = total dizygotic twin pairs; MZF= female monozygotic twin pairs; MZM= male monozygotic twin pairs; DZF= female dizygotic twin pairs; DZM= male dizygotic twin pairs; DZO= opposite sex dizygotic twin pairs; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; CD = conduct disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; NS = novelty seeking; NEUR = neuroticism;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p< .001

Appendix G

Table A4.

Percent Variance Explained by Each Latent Variable and Age in the Full Correlated Independent Pathway Model

| NS | NR | INT | EXT | Disorder Specific | Total | Age | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | ||

| NS | 32 | 4 | 65 | 32 | 4 | 65 | |||||||||||||

| NR | 21 | 3 | 76 | 21 | 3 | 76 | |||||||||||||

| MDD | 10 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 27 | 5 | 56 | 12 | |||

| GAD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 29 | 2 | 63 | 7 | |||

| SAD | 0 | 7 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 31 | 7 | 62 | 0 | |||

| ADHD | 9 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 25 | 7 | 65 | 4 | |||

| ODD | 10 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 28 | 6 | 57 | 5 | |||

| CD | 13 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 35 | 40 | 10 | 40 | 10 | |||

Note: NS = novelty seeking; NR = neuroticism; INT = internalizing; EXT = externalizing; MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; CD = conduct disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; A = Additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = non-shared environmental influence.

Appendix H

Table A5.

Covariance (% Covariance) Explained by Each Latent Variable and Age in the Full Independent Correlated Pathway Model

| Covariance Explained by Novelty Seeking | Covariance Explained by Neuroticism | Residual Covariance | Age | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| A | C | E | A | C | E | A | C | E | |||

| Covariance between internalizing dimensions | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| MDD-GAD | .009(1.76) | 0.015(2.97) | 0(−0.06) | 0.162(31.61) | 0.009(1.74) | 0.037(7.27) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.191(37.28) | 0.089(17.43) | 0.512(100) |

| MDD-SAD | −.017(−5.42) | −0.056(−18.24) | 0(−0.11) | 0.137(44.41) | 0.001(0.33) | 0.033(10.71 | 0.088(28.42) | 0(0) | 0.112(36.21) | 0.011(3.70) | 0.309(100) |

| GAD-SAD | −0.002(−0.36) | −0.019(−4.44) | 0(0.01) | 0.243(56.16) | 0.001(0.29) | 0.021(4.74) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.18(41.63) | 0.009(1.97) | 0.433(100) |

| Covariance between externalizing dimensions | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| ADHD-ODD | 0.095(18.03) | −0.006(−1.10) | 0.005(0.86) | 0.125(23.83) | 0.005(1.09) | 0.027(5.10) | −0(−0.63) | 0.056(10.62) | 0.181(34.49) | 0.041(7.79) | 0.526(100) |

| ADHD-CD | 0.108(29.01) | 0.006(1.64) | 0.003(0.93) | 0.085(22.65) | 0.023(6.23) | 0.008(2.15) | −0(−1.02) | −0.005(−1.44) | 0.091(24.29) | 0.058(15.56) | 0.373(100) |

| ODD-CD | 0.11(23.96) | −0.007(−1.45) | 0.004(0.84) | 0.07(15.37) | 0.021(4.48) | 0.01(2.12) | 0.088(19.17) | −0.005(−1.10) | 0.1(21.91) | 0.067(14.70) | 0.458(100) |

| Covariance between internalizing and externalizing dimensions | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| MDD-ADHD | 0.095(25.66) | −0.015(−4.17) | −0.003(−0.81) | 0.117(31.70) | −0.007(−1.77) | 0.037(9.88) | −0(−0.75) | 0(0) | 0.084(22.65) | 0.065(17.60) | 0.370(100) |

| MDD-ODD | 0.096(20.15) | 0.017(3.50) | −0.003(−0.70) | 0.098(20.45) | −0.006(−1.21) | 0.044(9.25) | 0.064(13.33) | 0(0) | 0.093(19.42) | 0.075(15.82) | 0.477(100) |

| MDD-CD | 0.11(29.75) | −0.018(−4.81) | −0.003(−0.68) | 0.066(17.85) | −0.026(−6.96) | 0.013(3.59) | 0.073(19.72) | 0(0) | 0.046(12.56) | 0.107(28.99) | 0.369(100) |

| GAD-ADHD | 0.009(2.16) | −0.005(−1.28) | 0(0.11) | 0.208(56.16) | −0.008(−1.97) | 0.023(5.52) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.135(32.93) | 0.049(11.82) | 0.410(100) |

| GAD-ODD | 0.009(2.17) | 0.006(1.37) | 0(0.12) | 0.173(50.70) | −0.007(−1.72) | 0.027(6.61) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.149(36.08) | 0.056(13.58) | 0.414(100) |

| GAD-CD | 0.01(4.07) | −0.006(−2.40) | 0(0.15) | 0.117(46.30) | −0.032(−12.56) | 0.008(3.25) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.075(29.60) | 0.08(31.59) | 0.252(100) |

| SAD-ADHD | −0.017(−5.88) | 0.019(6.94) | 0(0.16) | 0.176(62.68) | 0(−0.33) | 0.02(7.16) | 0(−1.07) | 0(0) | 0.079(28.15) | 0.006(2.21) | 0.281(100) |

| SAD-ODD | −0.017(−5.63) | −0.021(−7.10) | 0(0.17) | 0.147(49.35) | 0(−0.27) | 0.024(8.18) | 0.07(23.44) | 0(0) | 0.088(29.45) | 0.007(2.42) | 0.297(100) |

| SAD-CD | −0.019(−7.97) | 0.022(9.35) | 0(0.16) | 0.099(41.24) | −0.004(−1.51) | 0.007(3.04) | 0.08(33.21) | 0(0) | 0.044(18.23) | 0.01(4.25) | 0.240(100) |

Note: MDD = major depressive disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CD = conduct disorder; A = Additive genetic influence; C = shared environmental influence; E = non-shared environmental influence.

Contributor Information

Laura K. Hink, University of Colorado at Boulder

Soo H. Rhee, University of Colorado at Boulder

Robin P. Corley, University of Colorado at Boulder

Victoria E. Cosgrove, University of Colorado at Boulder

John K. Hewitt, University of Colorado at Boulder

Robert J. Schulz-Heik, University of Colorado at Boulder

Benjamin B. Lahey, University of Chicago

Irwin D. Waldman, Emory University

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello JE, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1987. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carey G, DiLalla DL. Personality and psychopathology: Genetic perspectives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:32–43. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger RC. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants: A proposal. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger RC, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM. The tridimentional personality questionnaire: U.S. normative data. Psychological Reports. 1991;69:1047–1057. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. The Temperament and character inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. Washington University; St. Louis, MO: Center for Psychobiology of Personality; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar A, Johnson SL, Winters R. Distinctions between bipolar and unipolar Depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:307–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI. Effects of censoring on parameter estimates and power in genetic modeling. Twin Research. 2004;7:659–669. doi: 10.1375/1369052042663832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Silberg JL, Meyer JM, Maes HH, Simonoff E, Pickles, Hewitt JK. Genetics and developmental psychopathology: The main effects of genes and environment on behavioral problems in the Virginia twin study of adolescent behavioral development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:965–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, Rhee SH, Young S, Corley R, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental contributions to common psychopathologies of childhood and adolescence: A study of twins and their siblings. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9000-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG, Barrett P. A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fanous A, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Cancro R, Kendler KS. Neuroticism, major depression and gender: a population-based twin study. Psychological. Medicine. 2002;32:719–728. doi: 10.1017/s003329170200541x. doi: 10.1017\S003329170200541X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floderus-Myrhed B, Pedersen N, Rasmuson I. Assessment of heritability for personality based on a short-form of the Eysenck personality inventory: A study of 12,898 twin pairs. Behavior Genetics. 1980;10:153–162. doi: 10.1007/BF01066265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:857–864. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental sources of covariation between generalized anxiety disorder and neuroticism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1581–1587. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt JK, Silberg JL, Rutter M, Simonoff E, Meyer JM, Maes HH, Eaves LJ. Genetics and developmental psychopathology: Phenotypic assessment in the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:943–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine R, Martin NG, Henderson AS. Genetic covariation between neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Genetic Epidemiology. 1984;2:89–107. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370010202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Childhood derivatives of inhibition and lack of inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development. 1988;59:1580–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Lofthouse N, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. Differential risks of covarying and pure components in mother and teacher reports of externalizing and internalizing behavior across ages 5 to 14. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;31:267–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1023277413027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Gatz M, Pedersen NL. The sources of co-morbidity between major depression and generalized anxiety disorders in the Swedish national twin sample. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:453–462. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Tremblay RE, Pagani-Kurtz L, Vitaro F. Boy’s behavioral inhibition and the risk of later delinquency. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210049005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Jacobson KC, Gardner CO, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Prsonality and comorbidity of common psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;186:190–196. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG. The higher-order structure of common DSM mental disorders: Internalization, externalization, and their connections to personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:1245–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist. 2009;64:241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Chronis AM, Jones HA, Williams SH, Loney J, Waldman ID. Psychometric characteristics of a measure of emotional dispositions developed to test a developmental propensity model of conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Child &Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:794–807. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey ABB, Moffit TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 76–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental model of the propensity to offend during childhood and adolescence. In: Farrington DP, editor. Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 13. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2005. pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zheng X, Liang J, Peng Y. Coexistence of anhedonia and anxiety-independent increased novelty-seeking behavior in the chronic mild stress model of depression. Behavioral Process. 2010;83:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Comorbidity between and within childhood externalizing and internalizing disorders: Reflections and directions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:285–291. doi: 10.1023/A:1023229529866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Nikolas M, Jernigan K, Friderici K, Nigg JT. Personality mediation of genetic effects on attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Childhood Psychology. 2010;38:633–643. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon AJ, Henderson AS, Andrews G. Genetic and environmental determinants of the lability of trait neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Psychological Medicine. 1990;20:581–590. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Pilkonis PA. Neuroticism and affective instability: The same or Different? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:839–845. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KT, Kochanska G. Effortful control: Factor structure and relation to externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:503–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1019821031523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska C, Strong CM, Santosa CM, Wang PW, Ketter TA. Temperament commonalities and differences in euthymic mood disorder patients, creative controls, and healthy controls. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;85:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenhinkel AJ, Hartman CA, DE WINTER AF, Veentra R, Ormel J. Temperament profiles associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:421–440. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera RL, Fonseca M, Caetano SC, Hatch JP, Hunter K, Nicoletti M, Soares JC. Assessment of personality dimensions in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder using the Junior Temperament and Character Inventory. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2009;19:13–21. doi: 10.1089/cap.2008.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AD, Gray JA. The neuroscience of personality. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Sanson A, Smart D, Oberklaid F. Psychological disorders and Their correlates in an Australian community sample of preadolescent children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:563–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quay HC, Love CT. The effect of a juvenile diversion program of rearrests. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1977;4:337–396. [Google Scholar]

- Rettew DC, Copeland W, Stanger C, Hudziak JJ. Associations between temperament and DMS-IV externalizing disorders in children and adolescents. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25:383–391. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200412000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea SA, Gross AA, Haberstick BC, Corley RP. Colorado twin registry. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:941–949. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Cosgrove VE, Schmitz S, Haberstick BC, Corley RC, Hewitt JK. Early childhood temperament and the covariation between internalizing and externalizing behavior in school-aged children. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:33–44. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA. Temperament and the development of personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:55–66. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Plomin R. Temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1977;41:150–156. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4102_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms in childhood: Addressing the issues of specificity and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:355–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02168079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Pedlow R, Cann W, Prior M, Oberklaid Shyness ratings: Stability and correlates in early childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1996;19:705–724. [Google Scholar]

- Sasayama D, Hori H, Teraishi T, Hattori K, Ota M, Matsuo J, Hiroshi K. Difference in Temperament and Character Inventory scores between depressed patients with bopolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;132:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Moskowitz DS, Schwartzman AE, Ledingham JE. Aggressive, withdrawn, and aggressive/ withdrawn children in adolescence: Into the next generation. In: Pepler DJ, Rubin KH, editors. The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hilsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone M. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AL, Waldman ID. The etiology of associations between negative emotionality and childhood externalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:376–388. doi: 10.1037/a0019342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Waldman I, Van Hulle CA, Lahey BB. Shared genetic influences on negative emotionality and major depression/conduct disorder comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:818–827. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Brief manual for the multidimentional Personality Questionnaire. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman ID, Tackett JL, Van Hulle CA, Applegate B, Pardini D, Frick PJ, Lahey BB. Child and Adolescent Conduct disorder substantially shares genetic influences with three socioemotional dispositions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:57–70. doi: 10.1037/a0021351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Lahey BB, Russo MF, Frick PJ, Christ MAG, McBurnett K, Green SM. Anxiety, inhibition, and conduct disorder in children: I. Relations to social impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:187–191. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, O’Hara MW, Stuart S. Hierarchical structures of affect and psychopathology and their implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:282–288. doi: 10.1002/da.20496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Susser K, Catron T. Common and specific features of childhood psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:118–127. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]